Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) sense microbes via multiple innate receptors. Signals from different innate receptors are coordinated and integrated by DCs to generate specific innate and adaptive immune responses against pathogens. Previously, we have shown that two pathogen recognition receptors, TLR2 and dectin-1 that recognize the same microbial stimulus (zymosan) on DCs, induce mutually antagonistic regulatory or inflammatory responses, respectively. How diametric signals from these two receptors are coordinated in DCs to regulate or incite immunity is not known. Here we show that TLR2-signaling via AKT activates the β-catenin/TCF4 pathway in DCs and programs them to drive T regulatory cell differentiation. Activation of β-catenin/TCF4 was critical to induce regulatory molecules interleukin-10 (Il-10) and vitamin A metabolizing enzyme retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (Aldh1a2) and to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines. Deletion of β-catenin in DCs programmed them to drive TH17/TH1 cell differentiation in response to zymosan. Consistent with these findings, activation of the β-catenin pathway in DCs suppressed chronic inflammation and protected mice from TH17/TH1-mediated autoimmune neuroinflammation. Thus activation of β-catenin in DCs via the TLR2 receptor is a novel mechanism in DCs that regulates autoimmune inflammation.

Introduction

Innate immune cells sense microbes with a combination of several pattern recognition receptors. DCs play a vital role in initiating robust immune responses against pathogens (1-5). Emerging studies now show that DCs are also critical in promoting regulatory responses (6, 7). Therefore, DCs are critical for regulating the delicate balance between tolerance versus immunity that underlies disease progression in many autoimmune disorders, cancer and chronic infection. DCs express several Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the C-type lectins, which are critical in initiating immune response against pathogens (8-10). Engagement of such pattern recognition receptor (PRRs) promotes DC maturation and cytokine production (2, 8, 9). Consequently, types of cytokines produced by DCs dictate the outcome of adaptive immune responses (2). For example, activation of most TLRs on DCs induces strong production of IL-12(p70) that promotes IFN-γ producing TH1 cells. Other microbial stimuli that activate TLR2 on DCs induce IL-10 production and promote TH2 or Treg responses, whereas dectin-1 mediated signals in DCs that induce strong production of TGF-β, IL-6 and IL-23, which promote TH17 differentiation. However, the receptors and signaling networks that are critical in programming DCs in inducing inflammatory versus regulatory responses are still being elucidated.

Zymosan, a yeast cell wall derivative, is recognized by many innate immune receptors, including TLR2 and dectin-1, a C-type lectin receptor for β-gulcans (11-15). Combinatorial activation TLR2 and dectin-1 results in the induction of robust IL-10 production in DCs (16-19), as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages and DCs (14, 20). Consistent with this, our previous work has shown that TLR2 signaling induced splenic DCs to express the retinoic acid (RA) metabolizing enzyme Aldh1a2 and IL-10, and promoted T regulatory response (21). Furthermore, zymosan is also known to induce macrophages to secrete TGF-β (18, 19), a cytokine critical for the generation of regulatory T cells, as well as TH-17 cells (13, 22-24). Thus, microbial activation of TLR2 signaling pathway in general promotes T regulatory/TH2 responses and suppresses inflammatory responses (7, 25). In contrast, dectin-1 mediated signaling in DCs induces pro-inflammatory cytokines and promote TH1 and TH17 cell differentiation. (21, 26, 27). How signaling networks in DCs via TLR2 and dectin-1 are integrated and influence divergent innate and adaptive immune responses is poorly understood.

β-catenin, an essential component of canonical wnt pathway, is widely expressed in immune cells including DCs and macrophages (28). β-catenin signaling has been implicated in the differentiation of myeloid DCs and plasmactyoid DC differentiation from HSCs (29, 30). Our previous work has shown that unlike in splenic DCs, β-catenin signaling is active constitutively in intestinal DCs and macrophages, and is critical for regulating intestinal homeostasis (31). However, its role in peripheral tolerance in not known. Here we show that TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin/TCF4 pathway resulting in programming DCs to induce regulatory responses to zymosan. We also show that activation of β-catenin/TCF4 is dependent on PI3K/AKT-mediated signals and programs DCs to a regulatory state, which produce retinoic acid and IL10. Consistent with this, the β-catenin/TCF4 pathway was critical for zymosan-mediated induction of regulatory Foxp3 T (Treg) cells, and suppression of TH1 and TH17 responses mediated autoimmunity in vivo. Accordingly, in the absence of β-catenin, zymosan induced potent TH1 and TH17 responses and exacerbated autoimmunity.

Materials & Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, TCF/LEF-reporter mice (32), Axin2 (LacZ) reporter mice (33), CD11c-Cre, Akt1−/− (34), TLR2−/− were originally obtained from Jackson Laboratories and were bred on-site. OT-II (Rag 2−/−) mice were obtained from Taconic. β-cateninflox/flox or TCF4flox/flox mice (35) were bred with transgenic mice (DC-cre) expressing cre enzyme under the control of CD11c-promoter (36), to generate mice lacking β-catenin or TCF4 in DCs. Successful cre-mediated deletion was confirmed as described in our previous study (31). All mice were maintained in specific pathogen–free conditions in the Georgia Regents University vivarium. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institute Animal Care and Use Committee of GRU.

Reagents and Antibodies

CD4 (RM4-5), IL-17 (TC11-18H10), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), anti-CD3 (145.2C11), anti-CD28 (37.51) and brefeldin A were purchased from BD Biosciences. Foxp3-PE (FJK-16s), CD11c (N418) and CD11b (M1/70) were purchased from ebioscience. Zymosan, curdlan, retinol and all-trans retinoic acid (RA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Purified Escherichia coli LPS, Pam-2-cys and Pam-3-cys, CpG and depleted zymosan were purchased from Invivogen. Antibodies for phospho-AKT, Phospho-β-catenin, active β-catenin, β-catenin, ERK, and phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) were from Cell Signaling. Rabbit monoclonal β-galactosidase antibody was purchased from Abcam. Peptides MOG35–55 (MEVGWYRSPFSRVVHLYRNGK) and OVA323–339 (ISQVHAAHAEINEAGR) were purchased from Anaspec.

Purification of splenic DCs

CD11c+ DCs were purified from spleen as previously described (21). In brief, spleens from mice were dissected, cut into small fragments, and then digested with collagenase type 4 (1 mg/ml) in complete DMEM plus 2% FBS for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed twice and the CD11c+ DCs were enriched using the CD11c microbeads from Miltenyi Biotec. The resulting purity of CD11c+ DCs was approximately 95%.

TLR stimulation of APCs

CD11c+ splenic DCs (106 cells/ml) were cultured with Pam-2-cys (100 ng/ml), zymosan (25 μg/ml,) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) for 24 hours. The supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis by ELISA, whereas cells were collected for gene expression analysis by RT-PCR.

In vitro culture of murine DCs and T cells

In vitro stimulation was performed as previously described (21). In brief, purified splenic CD11c+ DCs (106 cells/ml) were stimulated with zymsoan (25 μg/ml) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) for 8 hrs and washed with media three times. In some experiments DCs were cultured with disulphiram (100 nM) or PI3K inhibitor (5 μM), ERK inhibitor (1 μM), or AKT inhibitor (5 μM) for the duration of stimulation. Activated DCs (2 × 104 ) were cultured together with naive CD4+CD62L+ OT-II CD4+ T cells (105) and OVA (2 μg/ml) in 200 μl RPMI complete medium in 96-well round-bottomed plates. Supernatants were analyzed after 90 h for cytokine production by ELISA and cells were collected and analyzed directly for Foxp3 or were restimulated for intracellular cytokine staining. In some experiments, 500 nM retinol (sigma) and/or 1ng/ml TGF-β (R&D) were added to cultures. In some experiments intracellular Foxp3 analysis was performed before stimulation. For secondary restimulation, cells were collected after 90 h of primary culture followed by incubation for 6 h with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) in the presence of Brefeldin-A for intracellular cytokine detection. In some experiments cells were restimulated with OVA (2 μg/ml) for 48 h for analysis of cytokine production in cell supernatants.

OT-II CD4+ T cell adoptive transfer

β-catfl/fl and β-catΔDC recipient mice were reconstituted with 2.5 × 106 OT-II TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells one day prior to receiving 25 μg MHC class II–restricted OVA peptide in PBS alone or PBS containing either 50 μg zymosan or 50 μg of curdlan by iv injection. Four days later, spleens were removed and after RBC lysis, total splenocytes were counted, stained with antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data were acquired on a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences) or LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software. In vitro recall responses were assayed by restimulating total splenocytes (2×106/ml) for 6 h with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg /ml) in the presence of brefeldin A for intracellular cytokine detection or were restimulated with OVA (2 μg/ml) for 48 h for analysis of proliferation and cytokine production in cell supernatants.

Flow cytometry

Isolated splenocytes were resuspended in PBS containing 5% FBS. After incubation for 15 min at 4°C with the blocking antibody 2.4G2 (anti-FcγRIII/I), the cells were stained at 4°C for 30 min with the appropriate labeled antibodies. Samples were then washed two times in PBS containing 5% FBS. The samples were immediately analyzed at this point, or fixed in PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C. Intracellular staining for β-catenin, active β-catenin, phospho β-catenin, ERK, AKT, GSK3β and β-galactosidase were performed using rabbit monoclonal antibody or with appropriate isotype control in TBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit-anti-goat immunoglobulin or goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity was determined using ALDEFLUOR staining kit (Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACS Caliber or LSR II flow cytometer at GRU.

EAE induction

EAE induction experiments were performed as described in our previous study (21). EAE was induced by s.c. immunization in the hind flanks on days 0 using 100 μg of MOG35–55 emulsified in CFA containing 2.5 mg/ml heat-inactivated Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difco). Some experiments were performed using 100 μg of MOG35-55 plus 100 μg of zymosan in IFA. Mice also received 250 ng of pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories) i.p. on day 0 and 2 post immunization. In some instances mice received PBS or zymosan (100 μg) by i.v. at the time of immunization. Disease severity was assessed according to the following scale: 0, no disease; 1, flaccid tail; 2, hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis; 4, forelimb weakness; and 5, moribund.

CNS T cell isolation

Mice were euthanized with CO2 and perfused through the left ventricle with PBS. The brain and spinal cord were removed from each animal and homogenized on a 0.2-μm filter. T cells were isolated over Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) and then were stained for Foxp3 or restimulated for 6 h with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) in the presence of Brefeldin A for intracellular cytokine detection.

Measurement of cytokine production

Cytokines in culture supernatants was measured by two-site sandwich ELISA. IL-17, IL-6, IL-12(p40), IL-12(p70), IL-10, IFN-γ and IL-23 levels were measured by ELISA kits obtained from eBioscience.

Quantitative Real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from purified splenic DCs using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using the superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR and random hexamer primers (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was used as a template for quantitative real-time PCR using SYBER Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad) and gene specific primers as described in our previous study (21) and Gene expression was calculated relative to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (Software for Science). Mean clinical scores were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney non-parametric t test. The statistical significance of differences in the means ± s.d. of cytokines released by cells of various groups was calculated with the Student’s t-test (one-tailed).

Results

TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin/TCF pathway

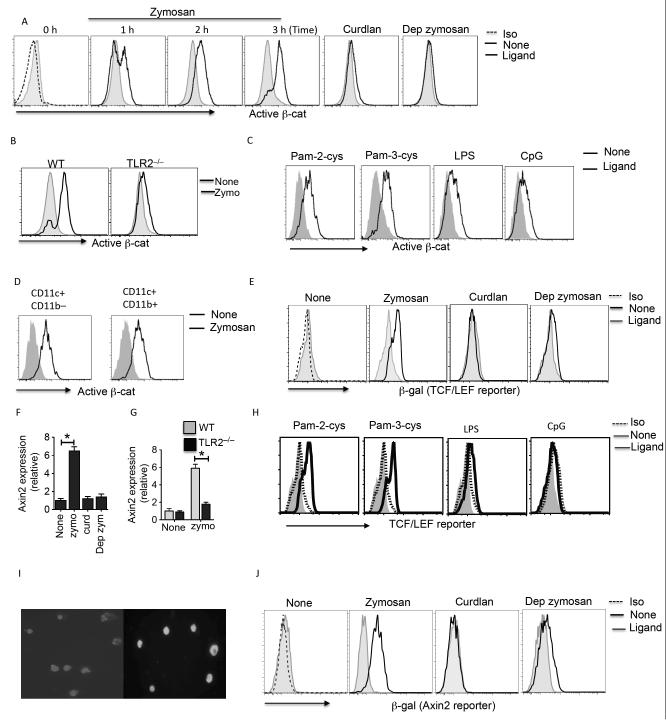

We first assessed whether TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin using antibody that recognizes the active form of β-catenin. Splenic DCs without any treatment showed low/undetectable levels of active β-catenin (Fig 1A). In contrast, DCs stimulated with zymosan showed increased levels of active β-catenin compared to untreated DCs (Fig 1A). β-catenin activation was detected in DCs as early as 1 hr after zymosan stimulation (Fig. 1A). Since, zymosan signals through TLR2 and dectin-1 (18), we next determined whether activation of β-catenin is dependent on TLR2 or dectin-1. DCs treated with dectin-1 ligands, curdlan or depleted zymosan (Dep zymo) failed to activate β-catenin compared to zymosan treated DCs (Fig 1A). Consistent with this observation, TLR2- deficient DCs treated with zymosan also showed low levels of active β-catenin compared to wild-type DCs (Fig. 1B). We next examined whether other TLR ligands can activate β-catenin in DCs. Treatment with TLR2/6 ligand Pam-2-cys or TLR2/1 ligand Pam-3-cys resulted in increased active β-catenin, albeit at lower levels compared to zymosan (Fig 1C). These data suggest the zymosan-induced β-catenin activation is mediated through TLR-2 in combination with other receptors. Furthermore, treatment with TLR9 ligand (CpG) and TLR4 ligand (LPS) resulted in mild β-catenin activation as compared to TLR2 ligands (Fig 1C). With further analysis of DC subsets, we observed β-catenin activation in splenic CD11c+ CD11b– and CD11c+ CD11b+ DCs (Fig 1D). These data suggest that TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin in DCs.

Figure: 1. Zymosan activates β-catenin/TCF pathway via a mechanism involving TLR2.

(A, B) Expression of active β-catenin by CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT or TLR2−/− stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) or depleted zymosan (dep zymo; 25 μg/ml) at indicated time points as assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (C) Expression of active β-catenin by CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT stimulated with Pam-2-cys (2 μg/ml) or Pam-3-cys (2μg/ml) or LPS (5 μg/ml) or CpG (5 μg/ml) for 3 h and assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (D) Active β-catenin expression in CD11c+ CD11b– and CD11c+ CD11b– splenic DC subsets was assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (E) β-galactosidase expression in CD11c+ splenic DCs isolated from TCF-reporter mice stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml ) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) or depleted zymosan (dep zymo; 25 μg/ml) for 18 h, and assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (F, G) Axin2 mRNA expression by splenic DCs from WT or TLR2−/− stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml ) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) or depleted zymosan (dep zymo; 25 μg/ml). (H) β-galactosidase expression in CD11c+ splenic DCs isolated from TCF-reporter mice stimulated with stimulated with Pam-2-cys (2 μg/ml) or Pam-3-cys (2μg/ml) or LPS (5 μg/ml) or CpG for 18 h, and assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (I) Intracellular expression of bcatenin (green) and nuclei (blue) in splenic DCs isolated from WT mice cultured in medium alone or with zymosan for 3 hr. Purified CD11c+ splenic DCs were stimulated with or without zymosan (25 mg/ml) for 3 hours and permeabilized with BD Fix and Perm buffer. Cells were incubated with FITC-labeled b-catenin (1:100 dilution; Cell Signaling) for 1 hr and nuclie were stained with DAPI. Three images were acquired for each field using a Zeiss Axiovert LSM-410 confocal microscope (showing FITC and DAPI simultaneously on the cells). (J) β-galactosidase expression in CD11c+ splenic DCs isolated from Axin2-reporter mice stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) or depleted zymosan, and assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Data are from one experiment representative of three independent experiments. *P<0.01

Activation of β-catenin results in its translocation to the nucleus, where it interacts with T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor TCF/LEF family members and regulates transcription of several target genes (28, 37). So, we next tested whether zymosan induced β-catenin activation promoted TCF/LEF dependent gene transcription using the TCF/LEF reporter mice and β-catenin/TCF-responsive reporter strain, Axin2NLSlacZ. Splenic DCs from TCF/LEF-reporter mice cultured with zymosan showed strong β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression compared to untreated DCs (Fig 1E). Consistent with this observation, increased expression of the β-catenin/TCF target gene Axin2 was detected and profound induction of β-catenin/TCF-responsive reporter strain, Axin2NLSlacZ in DCs in response to zymosan (Fig 1F). Moreover, TLR2−/− mice showed no induction of Axin2 in response to zymosan further confirming the role of TLR2 mediated signals in activation of β-catenin signaling pathway (Fig 1G). Similarly, treatment with other TLR2 ligands such as Pam-2-cys or Pam-3-cys resulted in increased β-gal expression. However, TLR4 (LPS) or TLR9 (CpG) activation resulted in low levels of β-gal expression (Fig 1H). Moreover zymosan treatment of DCs led to a significant amount of β-catenin translocation in the nucleus, a hallmark of active signaling (Fig 1I). In contrast, Dectin-1 ligands such as curdlan or depleted zymosan failed to induce β-gal expression in DCs compared to zymosan treated DCs (Fig 1J). Collectively, these results suggest that TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin and promote downstream transcriptional activity.

β-catenin activation in DCs promotes T regulatory cell differentiation and limits TH1/TH17 cell differentiation

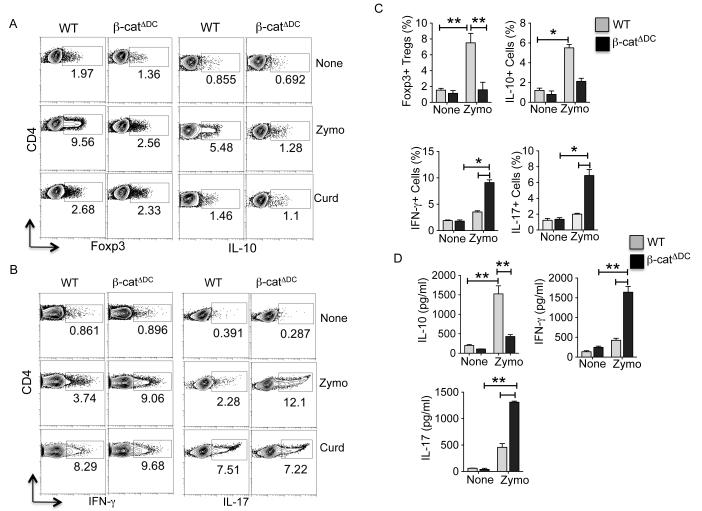

Zymosan conditions DCs to acquire regulatory properties that mostly induce T regulatory responses (18, 19, 21). In addition, activation of β-catenin in DCs induces T regulatory response (31, 38). Since our data showed that TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin in DCs, we reasoned that β-catenin pathway imparts regulatory phenotype on DCs in response to zymosan. Therefore, we tested the ability of zymosan or curdlan treated splenic DCs isolated from β-catfl/fl (WT) and β-catΔDC (β-catenin deleted specifically in DCs) (31) to promote differentiation of naive OT-II CD4+ T cells to induce Treg or TH1/TH17 cell differentiation. Consistent with previous studies (21, 27), zymosan-treated WT DCs induced both Foxp3+ Treg cells, and IL-10-producing Tr1 cells (Fig. 2A) in the presence or absence of TGF-β (Supplementary Figure 1A). Furthermore, zymosan stimulated WT DCs did not induce robust TH1 or TH17 cells (Fig. 2B), whereas curdlan stimulated WT-DCs induced both TH1 cells and TH17 cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, zymosan-treated DCs from β-catΔDC mice induced lower frequency of both Foxp3+ Treg and IL-10-producing Tr1 cells compared to wild type DCs (Fig. 2A) in the presence or absence of TGF-β (Supplementary Figure 1A). Interestingly, DCs from β-catΔDC induced robust TH1 and TH17 cells in response to zymosan (Fig 2B).

Figure 2. Zymosan-mediated activation of β-catenin in DCs promotes T regulatory cell differentiation and suppresses TH1/TH17 cell differentiation.

(A, B) CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT (β-catfl/fl) and β-catΔDC were stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) and after 10 h DCs (2 × 104) were washed and co-cultured with naïve CD4+CD62L+ OT-II T cells (1 × 105/ well) with OVA peptide (2 μg/ml) and TGF-β (1 ng/ml). After 4 d, OT-II cells were restimulated for 6 h with plated bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Foxp3 expression and, intracellular production of IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-10 by CD4 T cell were assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Data are from one experiment representative of three. (C) WT (β-catfl/fl) and β-catΔDC mice reconstituted with naïve CD4+CD62L+ OT-II T cells and were injected i.v. with class II– restricted OVA323–339 peptide (50 μg) plus PBS, or OVA323–339 (50 μg) plus zymosan (50 μg). Four days after challenge, unfractioned spleen cells were restimulated in vitro for 5 h with anti-CD3 and -CD28 antibodies in the presence of brefeldin A. Percent CD4+ OT-II+ cells positive for Foxp3, IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-10 as assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (D) unfractioned spleen cells from immunized mice as described in C were restimulated with OVA peptide (1 μg/ml) in culture for 48 h and cytokines in the supernatants were quantified by ELISA (n= 4, samples). *P<0.01; **P<0.001

We next determined whether β-catenin signaling was critical for induction of Treg cells in vivo in response to zymosan. Naïve OT-II cells were adoptively transferred into WT and β-catΔDC mice, followed by immunization with OVA alone, or OVA mixed with zymosan. Consistent with our previous studies (18, 21), WT mice immunized with OVA+ zymosan resulted in a robust induction of antigen specific Foxp3+ Treg cells and IL-10-producing Tr1 cells, compared to mice immunized with OVA alone (Fig. 2C & Supplementary Figure 1B). In contrast, the induction of Treg cells was significantly reduced in β-catΔDC mice when compared to wild type mice in response to zymosan (Fig. 2C & Supplementary Figure 1B). Furthermore, zymosan treatment led to an enhanced TH1 and TH17 responses, and reduced IL-10 producing cells in β-catΔDC mice (Fig. 2C, D & Supplementary Figure 1C). Collectively, these data indicate that β-catenin signaling in DCs is critical for the induction of T regulatory cells, and limiting TH1 and TH17 inflammatory responses in response to zymosan.

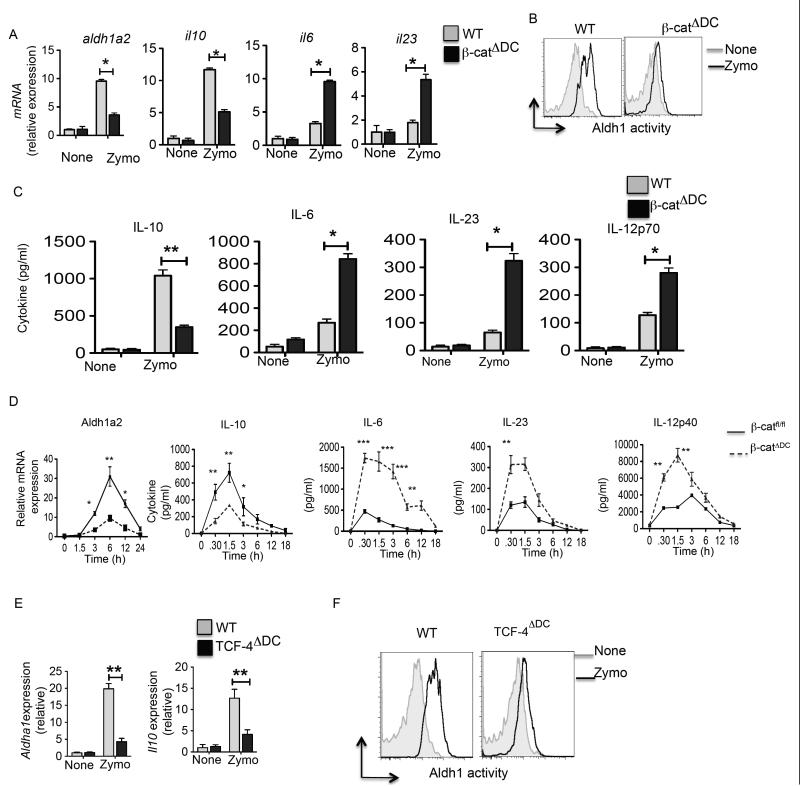

Activation of β-catenin-TCF4 pathway in DCs imparts anti-inflammatory phenotype on DCs

Zymosan has been shown induce immune regulatory genes IL-10, vitamin A metabolizing enzyme (Aldh1a2) and TGF-β in DCs (18, 19, 21, 39) that enable them to induce Treg cells and suppress the differentiation of TH1/TH17 cells. Furthermore, our previous study has shown that β-catenin is critical for the induction of vitamin A metabolizing enzymes and IL-10 in mucosal DCs. So, we hypothesized that zymosan-TLR2-mediated activation of β-catenin induces expression of IL-10 and Aldh1a2 in DCs. As observed in previous studies (18, 19, 21, 40), splenic DCs from WT mice treated with zymosan showed significant increase in Aldh1a2 and IL-10 mRNA levels compared to the untreated DCs (Fig. 3A). In contrast, DCs lacking β-catenin showed significantly lower levels of Il-10 and Aldh1a2 expression in response to zymosan (Fig. 3A). Consistent with these observations, WT DCs treated with zymosan showed higher levels of RALDH activity compared to DCs lacking β-catenin (Fig. 3B). Moreover, zymosan treatment of β-catΔDC DCs when compared to WT DCs produced significantly reduced levels of IL-10 and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-23 and IL-12, which induce differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into inflammatory TH17/TH1 cells (Fig 3C). In line with these in vitro results, DCs from β-catΔDC mice showed significantly reduced levels of Aldh1a2 and Il-10 expression upon zymosan injection (Fig 3D). In contrast, injection of zymosan into β-catΔDC mice induced robust pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to the WT mice (Fig 3D). Collectively, these results show that zymosan-TLR2-mediated β-catenin activation promotes expression of IL-10 and RA by DCs that is critical for inducing T regulatory responses and limiting TH1/TH17 cell differentiation.

Figure 3. β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway induces RA synthesizing enzyme (Aldh1a2) and IL-10, and suppresses inflammatory cytokines in splenic DCs.

(A) Purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT (β-catfl/fl) and β-catΔDC mice were cultured in media alone or with zymosan (25 μg/ml). (A) After 24 h, mRNA expression of Aldh1a2, IL-10, IL-6 and IL-23 relative to the expression GAPDH was analyzed by RT-PCR (n= 3 samples). (B) ALDH activity on purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT (β-catfl/fl) and β- catΔDC without (gray) or with (black) zymosan treatment. Data are from one experiment representative of two independent experiments. (C) Purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT (β-catfl/fl) and β-catΔDC mice were cultured in media alone or with zymosan as described in A. After 24h, cytokines in the cell culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Data are representative of three experiments. (D) β-catfl/fl and β-catΔDC mice were injected with PBS or zymosan (25 mg/ml) by i.v. route. Mice were sacrificed at indicated time points, and blood samples and spleens were collected. Induction of Aldh1a2 mRNA expression in purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from treated mice was analyzed by RT-PCR and serum cytokine levels were analyzed by ELISA. (E) Purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from TCF4fl/fl and TCF4ΔDC mice were cultured in media alone or with zymosan (25 μg/ml). After 24 h, expression of Aldh1a2 and IL-10 mRNAs relative to the expression of GAPDH was analyzed by RT-PCR (n= 3 samples). (F) ALDH activity on purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT (TCF4fl/fl) and TCF4ΔDC without (gray) or with (black) zymosan treatment. Data are from one experiment representative of two independent experiments. *P<0.01; **P<0.001; ***P<0.0001

The downstream mediator of β-catenin signaling in DCs that is critical for inducing IL-10 and Aldh1a2 is not known. β-catenin acts as a co-activator for several transcription factors (37) and TCF family of transcription factors are among downstream mediators of β-catenin signaling. Recently, it has been shown that DCs express TCF4 isoform (41). To directly assess whether TCF4 is involved in zymosan-TLR-2-mediated induction of IL-10 and Aldh1a2 in DCs, we crossed floxed TCF4 allele mice (TCF4fl/fl) (35, 42) with transgenic mice (CD11c-Cre) expressing Cre enzyme under the control of CD11c-promoter (36). As shown in Figure 3E, DCs lacking TCF4 showed significantly lower levels of IL-10 and Raldh2 mRNA expression in response to zymosan. In line with these observations, TCF4-deficient DCs treated with zymosan showed lower levels of RALDH activity compared to WT DCs (Fig. 3F). Collectively, these results show that zymosan-TLR2-mediated activation of β-catenin/TCF4 in DCs is critical for the induction of IL-10 and Aldh1a2.

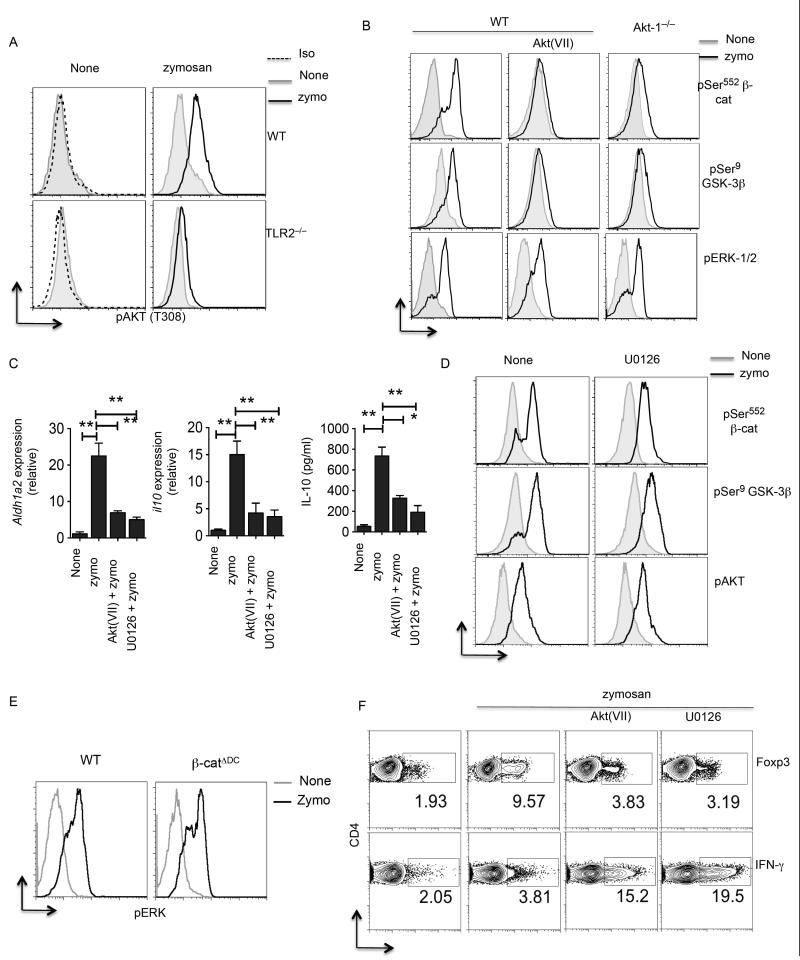

β-catenin activation in DCs is dependent on Akt but independent of Erk

TLR2-mediated signals activate PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Recent biochemical and genetic studies have shown that Akt phosphorylates β-catenin at Ser552 and promotes its transcriptional activity (43-45). Akt was also shown to phosphorylateand inactivate GSK-3β at Ser9, thereby preventing GSK-3β mediated β-catenin degradation (46). To elucidate the mechanisms by which zymosan-TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin in DCs, we first analyzed activation of Akt and MAPK ERK by flow cytometry using anti-phospho antibody. DCs cultured with zymosan showed enhanced Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 relative to untreated DCs (Fig. 4A). We next tested if Akt activation in DCs is dependent on TLR2. Accordingly, DCs from Tlr2−/− mice also showed lower levels of phospho-Akt compared to wild type DCs in response to zymosan (Fig 4A). Above results clearly show that zymosan via TLR2 activates both Akt and β-catenin. We hypothesized that Akt activates β-catenin and promotes downstream transcriptional activity. So, we tested whether Akt activates β-catenin by directly phosphorylating it at Ser552 in response to zymosan. DCs cultured with zymosan showed increase in phosphorylated β-catenin on Ser552 compared to the untreated controls (Fig. 4B). In contrast, DCs treated with Akt inhibitor completely abrogated β-catenin phosphorylation at Ser552 in response to zymosan (Fig. 4B). Consistent with this observation, DCs from Akt1−/− showed reduced levels of phospho β-catenin in response to zymosan (Fig. 4B). Moreover, Akt can also activate β-catenin indirectly through inactivation of GSK-3β through its direct phosphorylation at Ser9. Therefore, we quantified the phosphorylation status of GSK-3β in DCs in the presence or absence of zymosan. DCs cultured with zymosan showed marked increase in phosphorylated GSK-3β at Ser9 compared to the untreated DCs (Fig. 4B). In contrast, Akt inhibitor treatment markedly reduced the GSK-3β phosphorylation in response to zymosan (Fig. 4B). Further, DCs from Akt1−/− mice had reduced GSK-3β phosphorylation upon zymosan treatment (Fig. 4B). Consistent with a role for Akt in β-catenin activation, blocking Akt activity in DCs markedly decreased IL-10 and Aldh1a2 expression in response to zymosan (Fig. 4C). These results show that Akt activates β-catenin directly by phosphorylating it at Ser552 and indirectly preventing its degradation by inactivating GSK-3β in response to zymosan via TLR2.

Figure 4. PI3K/AKT mediated signals activate β-catenin in DCs.

(A) Representative histograms of pThr308 AKT in CD11c+ SPDCs from WT or TLR2−/− stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) after 3 h as assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (B) Representative histograms of pSer552 β-cat or pSer9 GSK-3β or pERK1/2 in CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT or AKT1−/− stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of AKT inhibitor VII (5 μM) for 3 h. (C) Purified CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT mice stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) in presence or absence of ERK inhibitor or AKT inhibitor. After 24 h expression of RALDH2 mRNA relative to the expression of mRNA encoding GAPDH was analyzed by RT-PCR (n= 3 samples). IL-10 cytokine levels in the culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. (D) Representative histograms of pSer552 β-cat or pSer9 or pAKT in CD11c+ splenic DCs from WT mice stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of Erk inhibitor (U0126; 1μM) for 3 h. (E) Representative histograms of pERK1/2 in CD11c+ SPDCs from WT or β-catΔDC stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) after 3 h as assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (F) CD11c+ SPDCs from WT were stimulated with zymosan (25 μg/ml) or curdlan (25 μg/ml) and after 10 h DCs (2 × 104) in the presence or absence of AKT inhibitor VII (5 μM) or Erk inhibitor (U0126; 1 μM). After 10 h DCs were washed and co-cultured with naïve CD4+CD62L+ OT-II T cells (1 × 105/ well ) with OVA peptide (2 μg/ml) and TGF-β (1 ng/ml). After 4 d, OT-II cells were restimulated for 6 h with plated bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Foxp3 expression and, intracellular production of IFN-γ by CD4 T cell were assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Data are from one experiment representative of three. *P<0.01; **P<0.001; ***P<0.0001

TLR2-mediated activation of ERK MAPK in DCs is critical for the induction of Aldh1a2 and IL-10 in response to zymosan. So, we next investigated whether Erk is critical for the activation of β-catenin. Treatment of DCs with Erk inhibitor had no effect on activation of β-catenin, Akt and GSK-3β in response to zymosan (Fig. 4D). Similarly, treatment of DCs with Akt inhibitor VII had no effect on the phosphorylation status and activation of Erk (Fig 4B). Furthermore, we observed similar levels of Erk phosphorylation in WT and β-catenin-deficient DCs in response to zymosan (Fig 4E). These two pieces of data demonstrate that Erk and Akt activation are independent of each other, and both are downstream of TLR2-signalling. Importantly, inhibition of Akt or Erk in DCs alone results in decreased expression of IL-10 and Aldh1a2 in response to zymosan (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, zymosan stimulated DCs treated with inhibitors of Akt or Erk were compromised in their ability to induce Tregs but promoted robust induction of TH1 cells (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these results demonstrate that zymosan-TLR-2 mediate Akt-dependent activation of β-catenin and Erk imparts anti-inflammatory phenotype on DCs.

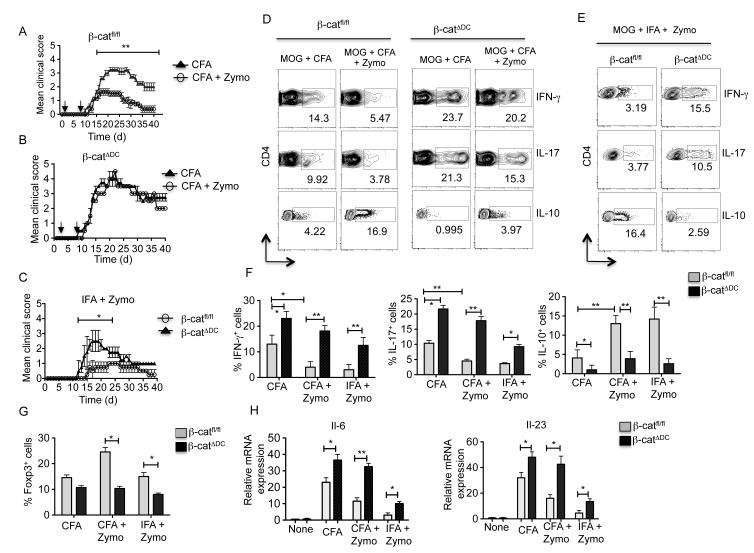

β-catenin/TCF pathway activation suppresses chronic inflammation and limits EAE

We and others have shown that zymosan and other TLR2-ligand treatment can suppress inflammation and limit autoimmunity in different experimental mouse models such as EAE (21, 39), diabetes (19, 47), airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) (48) and colitis (49). So, we next determined the importance of zymosan-TLR2-mediated activation of β-catenin pathway in DCs on EAE outcome. Mice were immunized with MOG35-55 (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) peptide emulsified in CFA and then treated with PBS or zymosan as previously described (21). Control mice treated with PBS showed onset of neurological impairment occurring around day 14 (Fig. 5A). We then determined whether zymosan was capable of actively suppressing the disease. Consistent with previous studies (21, 39), WT mice treated with zymosan developed significantly lower clinical scores compared to PBS-treated mice (Fig 5A). Since zymosan activates the β-catenin pathway, we next evaluated if the suppressive effect of zymosan was dependent on β-catenin. β-catΔDC mice treated with PBS showed early onset of neurological impairment and more severe disease compared to WT mice (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the regulatory role of β-catenin in DCs, treatment of zymosan failed to actively suppress disease onset or severity in mice lacking β-catenin in DCs (Fig. 5B). Accordingly, histopathological analysis showed less inflammation in the brain of zymosan treated mice compared to the brain of untreated WT mice (Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, we observed increased inflammation in the brain of β-catΔDC with or without zymosan treatment (Supplementary Figure 2). We then determined the phenotype of CNS infiltrated CD4+ T cells at day 18. We observed that zymosan treatment resulted in enhanced induction of Tr1 cells, relative to mice treated with PBS (Fig. 5D). In contrast, control treated mice showed a significant increase in the frequency of TH1 and TH17 cells compared to the zymosan treated mice (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, under homeostatic conditions β-catΔDC mice showed no difference in splenic Treg frequencies (Supplementary Figure 1D) and total Treg numbers (Data not shown). In zymosan treated β-catΔDC mice, we observed diminished frequency of Tr1 cells with greatly enhanced TH1 and TH17 responses in the CNS (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these results suggest that zymosan-TLR2-mediated activation of β-catenin signaling is essential for the induction of Foxp3+ Treg cells and Tr1 cells, and suppression of TH1 and TH17 responses. Our data also indicate that the absence of β-catenin signaling in DCs lead to an increase in number of T effector cells (TH1 and TH17) over Treg cells during the normal course of EAE. Furthermore, zymosan treatment in these mice had no effect on disease severity due to possible lack of β-catenin activation when compared to WT mice.

Figure 5. Activation of β-catenin suppresses the development of clinical EAE and chronic inflammation.

(A, B, C) β-catfl/fl and β-catΔDC were immunized with 100 μg of MOG35-55 + CFA or MOG35-55 + CFA + zymosan or MOG +IFA + zymosan on days 0. Mice also received 250 ng of pertussis toxin on days 0 and 2. The progression of EAE disease severity in different group of mice was monitored on various days post immunization. (D, E) Mononuclear cells were isolated from CNS tissue on day 18 after immunization and restimulated in vitro for 5 h with anti-CD3 and -CD28 antibodies in the presence of brefeldin A. Induction of IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-10 was assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry by gating on CD4+ T cells. Numbers in FACS plots represent percentage of cells positive for the indicated protein. Data are from one experiment representative of two. (F, G) Percentage of Foxp3+ Tregs, Tr1+, IFN-γ+(TH1) and IL-17+(TH17) cells assessed in the CNS of β-catfl/fl and β-catΔDC immunized mice at day 18. Data represent mean (± s.d.) of 6 mice per group. (H) Total RNA was isolated from purified CD11c+ SPDCs of β-catfl/fl and β-catΔDC immunized mice at day 18 as described above, and expression of IL23p19 and IL-6 mRNA was analyzed RT-PCR (n= 3 samples). Data are representative of two independent experiments. *P<0.01; **P<0.001; ***P<0.0001.

Our previous studies revealed that injection of MOG35-55 peptide plus zymosan emulsified in IFA induces a relatively attenuated and transient disease course in mice (21). In the absence of TLR2-signaling, injection of MOG35-55 peptide plus zymosan emulsified in IFA results in severe and sustained disease (21). Next, we immunized WT and β-catΔDC mice with MOG35-55 peptide and zymosan emulsified in IFA. Consistent with previous studies, MOG35-55 peptide plus zymosan induced a greatly attenuated and transient disease (Fig. 5C). In contrast, in β-catΔDC mice developed more severe and sustained disease compared to WT immunized mice (Fig. 5C). Accordingly, β-catΔDC mice showed diminished frequency of Treg and Tr1 cells, and greatly enhanced frequencies of TH1 and TH17 cells in the CNS (Fig. 5 E-G). Thus, activation of the β-catenin pathway in DCs can suppressTH1 and TH17 responses and limit EAE in response to zymosan.

IL-6 and IL-23 play pivotal roles in the differentiation and expansion of TH-17 cells, and in the pathogenesis of EAE (50, 51). Thus, we evaluated the IL-6 and IL-23p19 mRNA expression in splenic DCs isolated ex vivo from wild type versus β-catΔDC mice at day 18 in response to zymosan (Fig. 5H). We also measured the serum cytokine levels of IL-23 in wild type and β-catΔDC mice (Fig. 5H) upon zymosan injection. Zymosan treatment markedly decreased expression of IL-6 and IL-23 in DCs relative to control wild type mice DCs (Fig. 5H). In contrast, zymosan treatment of β-catΔDC mice resulted in increased expression of IL-6 and IL-23 in DCs compared to zymosan treated WT mice (Fig. 5H). Consistent with these results, we also observed increased levels of serum IL-6 and IL-23 in β-catΔDC mice compared to wild type mice treated with zymosan (data not shown). Collectively, these results demonstrate that activation of β-catenin pathway in DCs signaling suppresses IL-6 and IL-23 production in DCs and limits chronic inflammation.

Discussion

The signaling networks and transcription factors that program DCs to induce regulatory versus inflammatory responses remain poorly defined. Here we show that, TLR2-mediated signals activate the β-catenin/TCF pathway in DCs, resulting in the acquisition of potent regulatory phenotypes that induces T regulatory responses, both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the present study also shows that activation of β-catenin/TCF4 pathway in DCs is critical for the induction of IL-10 and vitamin A metabolizing enzyme (Aldh1a2) in response to zymosan. In contrast, loss of β-catenin signaling in DCs programs them to an inflammatory state that promotes TH1 and TH17 responses. We further demonstrate that activation of the β-catenin/TCF pathway in DCs suppressed chronic inflammation and disease severity of EAE. Accordingly β-catΔDC mice showed marked increase in the frequency of TH1/TH17 cells, and a concomitant increase in disease severity. Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that the β-catenin/TCF4 pathway regulates the functions downstream of TLR2 signaling in DCs and is critical for programming them to regulatory state. Thus activating this pathway is an effective strategy to modulate autoimmune disease. Several aspects of these findings deserve further comment.

First, a role for the β-catenin pathway in intestinal DCs and in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis is well established (31, 52, 53), however its role in systemic immune responses is not known. Furthermore, it is not known whether the β-catenin pathway can be activated in peripheral DCs, and if so, the receptors and signaling pathways that activate β-catenin in DCs are not known. The current study demonstrates for the first time that β-catenin/TCF4 pathway can be activated in splenic DCs via TLR2 signaling in response to zymosan. Our study also defines an essential role for β-catenin/TCF4 pathway in programming DCs to a regulatory state. Recent studies by others and ours have shown the Wnt- and E-cadherin- mediated signaling can also activate β-catenin and program DCs to regulatory state (31, 38). However, zymosan-mediated early activation of β-catenin (1-3h) in DCs was dependent on TLR2 but independent of Wnt.

Second, DC-derived signals and cytokines dictate the T cell activation and differentiation. The capacity of zymosan treated DCs to suppress inflammatory responses and to convert naïve T cells to Tregs was dependent on IL-10 and RA (21). There is also increasing evidence that RA and IL-10 regulate the immune response by acting directly on DCs (54-57). However, downstream signaling pathways and transcription factors in DCs critical for the induction of these two genes are unknown. In the current study, we report that TLR2-dependent expression of IL-10 and Aldh1a2 is dependent on β-catenin and its downstream mediator TCF4. Deletion of β-catenin or TCF-4 in DCs resulted in significant decrease in IL-10 and Raldh expression, and concurrent increase in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, DCs from β-catΔDC or TCF-4ΔDC mice were less potent in inducing Tregs and more potent in inducing TH1/TH17 cells. Collectively, these results strongly support the hypothesis that β-catenin/TCF4 play a pivotal role in inducing IL-10 and Aldh1a2 gene transcription. In addition, TLR2-dependent activation β-catenin in DCs is critical for expression of IL-10 and Raldh2 thereby limiting pro-inflammatory genes expression and reducing potential negative consequences of inflammatory gene expression.

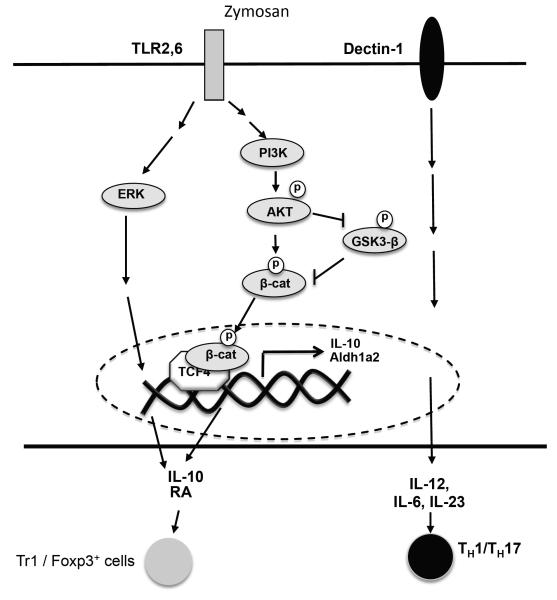

Third, the mechanisms by which TLR2-mediated signals activate β-catenin in DCs are not known. Recent studies have shown that PI3K/Akt pathway is an important regulator of innate immune responses in response to TLR-mediated signaling (58-60). (61). Our data indicated that TLR2-mediated signals in DCs activated Akt and Erk in response to zymosan. Our data also show that TLR2-mediated signaling via Akt pathway activated β-catenin by two different mechanisms. First, Akt directly phosphorylated β-catenin at Ser552 and promoted its activation in response to zymosan. Second, our data also demonstrated that Akt activated β-catenin by directly phosphorylating GSK-3β at Ser9 to inhibit GSK-3β-driven β-catenin degradation. Blocking Akt activation in DCs or deletion of Akt1 in DCs completely abrogated the GSK-3β phosphorylation at Ser9 and β-catenin phosphorylation at Ser552 in response to zymosan. Recent studies have highlighted the PI3K/Akt pathway as an important inducer of anti-inflammatory responses to TLR-mediated signaling (60-63). Further, the PI3K/Akt pathway was shown to negatively regulate TLR-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokines (58). Finally, our study shows that the TLR-mediated signaling activates both Erk and Akt/ β-catenin pathway and these pathways regulate the expression of IL-10 and RA in DCs. Our study here shows that blocking the Erk or Akt pathway in DCs resulted in marked decrease in IL-10 and Raldh2 gene expression and increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (data not shown). Consistent with this, we also observed marked decrease in IL-10 and Raldh2 expression in Akt1 DCs. These observations correlated with the marked defect in β-catenin activation and transcriptional activity in the absence of PI3K/Akt signals in response to zymosan. Thus, Akt-dependent β-catenin activation limits pro-inflammatory gene expression and reduces the potential negative consequences of inflammatory gene expression (Fig 6).

Figure 6. Mechanism of regulation of IL-10 and Aldh1a2 by β-catenin/TCF4 pathway in DCs.

Innate sensing of zymosan via TLR2 efficiently induces Akt and Erk activation. Akt then activates β-catenin by directly phosphorylating it at Ser552 and indirectly by inactivating GSK-3β activity. Activated β-Catenin interacts with TCF4 in the nucleus, and transcriptionally induces IL-10 and Aldh1a2 gene expression in DCs, which are critical for inducing T regulatory responses and limiting TH1/TH17 cell differentiation. Activation of Erk and Akt/β-catenin pathway work synergistically to induce IL-10 and Aldh1a2. Dectin-1 signaling does not play a major role in β-catenin activation but promotes induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines that are critical of TH1/TH17 cell differentiation.

Consistent with a regulatory role for the TLR2-signaling pathway, recent studies have shown TLR2-ligands or microbial activation of TLR2 can suppress inflammation and limit autoimmunity in mice in different disease settings (19, 21, 39, 47-49). Further, treatment of mice with zymosan at low doses limits EAE and type I diabetes, and these responses were dependent on TLR2. The present study also highlights the functional significance of β-catenin/TCF pathway in DCs in active suppression of EAE disease progression. Most importantly, activation of this pathway resulted in striking reductions in the frequencies of TH1/TH17 cells, and enhanced frequencies of Tregs and Tr1 cells. In addition, the present study also reveals that activation of the β-catenin/TCF4 pathway suppresses IL-23 and IL-6 production by DCs, thereby limiting TH17 cells-mediated chronic inflammation.

DCs are vital in regulating the balance between immunity versus tolerance. Recently, emerging studies have shown that multiple factors control DC responses against microbes. These include innate receptors on DCs that recognize microbial and non-microbial stimuli, intercellular signaling networks within DCs, intercellular interaction between DCs and multiple cell types, and inductive signals from the local microenvironment. Paradoxical to its well established role in promoting immunity against pathogens (2, 64), recent studies have shown that signaling via innate receptors can also result in tolerogenic responses (7, 25). In this study, we have demonstrated that the TLR2-AKT-β-catenin/TCF4 signaling network is critical in programing DCs into regulatory states and promoting T regulatory responses. What evolutionary benefit might accrue to the microbe or to the host, from activating the β-catenin/TCF pathway? Recent studies have shown that sensing of commensals via TLR2 induces regulatory responses and limits inflammatory responses in the gut (49, 65-67) and skin (68). In the face of a persistent immune response against a persistent microbe such as yeasts, virus and commensal bacteria, activating β-catenin pathway could represent a mechanism to dampen excessive inflammation and limit collateral damage to host.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeanene Pihkala and William King for technical help with FACS sorting and analysis.

This work was supported by grants to S.M. by National Institutes of Health Grant DK097271 and AI04875; GRU Startup fund and GRU Cancer Center Seed Grant.

References

- 1.Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2002;2:151–161. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulendran B. Modulating vaccine responses with dendritic cells and Toll- like receptors. Immunological reviews. 2004;199:227–250. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu L, Liu YJ. Development of dendritic-cell lineages. Immunity. 2007;26:741–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palucka AK, Ueno H, Fay JW, Banchereau J. Taming cancer by inducing immunity via dendritic cells. Immunological reviews. 2007;220:129–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annual review of immunology. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manicassamy S, Pulendran B. Dendritic cell control of tolerogenic responses. Immunological reviews. 2011;241:206–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and acquired immunity. Seminars in immunology. 2004;16:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annual review of immunology. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. DC-SIGN: escape mechanism for pathogens. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2003;3:697–709. doi: 10.1038/nri1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for beta-glucans. Nature. 2001;413:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown GD, Herre J, Williams DL, Willment JA, Marshall AS, Gordon S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown GD, Taylor PR, Reid DM, Willment JA, Williams DL, Martinez-Pomares L, Wong SY, Gordon S. Dectin-1 is a major beta- glucan receptor on macrophages. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;196:407–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Canavera SJ, Akira S, Underhill DM. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll- like receptor 2. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:1107–1117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A, Hajjar AM, Stevens A, Wilson CB, Bassetti M, Aderem A. The Toll-like receptor 2 is recruited to macrophage phagosomes and discriminates between pathogens. Nature. 1999;401:811–815. doi: 10.1038/44605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers NC, Slack EC, Edwards AD, Nolte MA, Schulz O, Schweighoffer E, Williams DL, Gordon S, Tybulewicz VL, Brown GD, Reis e Sousa C. Syk-dependent cytokine induction by Dectin-1 reveals a novel pattern recognition pathway for C type lectins. Immunity. 2005;22:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slack EC, Robinson MJ, Hernanz-Falcon P, Brown GD, Williams DL, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz VL, Reis e Sousa C. Syk-dependent ERK activation regulates IL-2 and IL-10 production by DC stimulated with zymosan. European journal of immunology. 2007;37:1600–1612. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillon S, Agrawal S, Banerjee K, Letterio J, Denning TL, Oswald-Richter K, Kasprowicz DJ, Kellar K, Pare J, van Dyke T, Ziegler S, Unutmaz D, Pulendran B. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:916–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Li R, Vasu C. Induction of innate immune response through TLR2 and dectin 1 prevents type 1 diabetes. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:8323–8334. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Underhill DM. Collaboration between the innate immune receptors dectin-1, TLRs, and Nods. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:75–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manicassamy S, Ravindran R, Deng J, Oluoch H, Denning TL, Kasturi SP, Rosenthal KM, Evavold BD, Pulendran B. Toll-like receptor 2- dependent induction of vitamin A-metabolizing enzymes in dendritic cells promotes T regulatory responses and inhibits autoimmunity. Nature medicine. 2009;15:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, II Ivanov, Min R, Victora GD, Shen Y, Du J, Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY, Ziegler SF, Littman DR. TGF- beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong C. TH17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nri2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pulendran B, Tang H, Manicassamy S. Programming dendritic cells to induce T(H)2 and tolerogenic responses. Nature immunology. 2010;11:647–655. doi: 10.1038/ni.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshitomi H, Sakaguchi N, Kobayashi K, Brown GD, Tagami T, Sakihama T, Hirota K, Tanaka S, Nomura T, Miki I, Gordon S, Akira S, Nakamura T, Sakaguchi S. A role for fungal {beta}-glucans and their receptor Dectin-1 in the induction of autoimmune arthritis in genetically susceptible mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:949–960. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeibundGut-Landmann S, Gross O, Robinson MJ, Osorio F, Slack EC, Tsoni SV, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Brown GD, Ruland J, Reis e Sousa C. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nature immunology. 2007;8:630–638. doi: 10.1038/ni1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staal FJ, Luis TC, Tiemessen MM. WNT signalling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou J, Cheng P, Youn JI, Cotter MJ, Gabrilovich DI. Notch and wingless signaling cooperate in regulation of dendritic cell differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:845–859. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehtonen A, Ahlfors H, Veckman V, Miettinen M, Lahesmaa R, Julkunen I. Gene expression profiling during differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages or dendritic cells. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2007;82:710–720. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manicassamy S, Reizis B, Ravindran R, Nakaya H, Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Wang YC, Pulendran B. Activation of beta-catenin in dendritic cells regulates immunity versus tolerance in the intestine. Science. 2010;329:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1188510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maretto S, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Braghetta P, Broccoli V, Hassan AB, Volpin D, Bressan GM, Piccolo S. Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lustig B, Jerchow B, Sachs M, Weiler S, Pietsch T, Karsten U, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Schlag PM, Birchmeier W, Behrens J. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:1184–1193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1184-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Feng F, Birnbaum MJ. Akt1/PKBalpha is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:38349–38352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angus-Hill ML, Elbert KM, Hidalgo J, Capecchi MR. T-cell factor 4 functions as a tumor suppressor whose disruption modulates colon cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:4914–4919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caton ML, Smith-Raska MR, Reizis B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8- dendritic cells in the spleen. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1653–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang A, Bloom O, Ono S, Cui W, Unternaehrer J, Jiang S, Whitney JA, Connolly J, Banchereau J, Mellman I. Disruption of E-cadherin- mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity. 2007;27:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Gonnella P, Safavi F, Vessal G, Nourbakhsh B, Zhou F, Zhang GX, Rostami A. Low dose zymosan ameliorates both chronic and relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2013;254:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SW, Park Y, Eun SY, Madireddi S, Cheroutre H, Croft M. Cutting edge: 4-1BB controls regulatory activity in dendritic cells through promoting optimal expression of retinal dehydrogenase. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:2697–2701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghosh HS, Cisse B, Bunin A, Lewis KL, Reizis B. Continuous expression of the transcription factor e2-2 maintains the cell fate of mature plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;33:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brault V, Moore R, Kutsch S, Ishibashi M, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP, Sommer L, Boussadia O, Kemler R. Inactivation of the beta-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development. 2001;128:1253–1264. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang D, Hawke D, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Meisenhelder J, Nika H, Mills GB, Kobayashi R, Hunter T, Lu Z. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by AKT promotes beta-catenin transcriptional activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:11221–11229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611871200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gantner BN, Jin H, Qian F, Hay N, He B, Ye RD. The Akt1 isoform is required for optimal IFN-beta transcription through direct phosphorylation of beta-catenin. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:3104–3111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang P, An H, Liu X, Wen M, Zheng Y, Rui Y, Cao X. The cytosolic nucleic acid sensor LRRFIP1 mediates the production of type I interferon via a beta-catenin-dependent pathway. Nature immunology. 2010;11:487–494. doi: 10.1038/ni.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hay N. Interplay between FOXO, TOR, and Akt. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1813:1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burton OT, Zaccone P, Phillips JM, De La Pena H, Fehervari Z, Azuma M, Gibbs S, Stockinger B, Cooke A. Roles for TGF-beta and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 in regulatory T cell expansion and diabetes suppression by zymosan in nonobese diabetic mice. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:2754–2762. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nawijn MC, Motta AC, Gras R, Shirinbak S, Maazi H, van Oosterhout AJ. TLR-2 activation induces regulatory T cells and long-term suppression of asthma manifestations in mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e55307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ey B, Eyking A, Klepak M, Salzman NH, Gothert JR, Runzi M, Schmid KW, Gerken G, Podolsky DK, Cario E. Loss of TLR2 worsens spontaneous colitis in MDR1A deficiency through commensally induced pyroptosis. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:5676–5688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Differentiation and function of Th17 T cells. Current opinion in immunology. 2007;19:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shan M, Gentile M, Yeiser JR, Walland AC, Bornstein VU, Chen K, He B, Cassis L, Bigas A, Cols M, Comerma L, Huang B, Blander JM, Xiong H, Mayer L, Berin C, Augenlicht LH, Velcich A, Cerutti A. Mucus enhances gut homeostasis and oral tolerance by delivering immunoregulatory signals. Science. 2013;342:447–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1237910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oderup C, LaJevic M, Butcher EC. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt proteins program dendritic cell responses for tolerance. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:6126–6134. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saurer L, McCullough KC, Summerfield A. In vitro induction of mucosa-type dendritic cells by all-trans retinoic acid. J Immunol. 2007;179:3504–3514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zapata-Gonzalez F, Rueda F, Petriz J, Domingo P, Villarroya F, de Madariaga A, Domingo JC. 9-cis-Retinoic acid (9cRA), a retinoid X receptor (RXR) ligand, exerts immunosuppressive effects on dendritic cells by RXR-dependent activation: inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma blocks some of the 9cRA activities, and precludes them to mature phenotype development. J Immunol. 2007;178:6130–6139. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geissmann F, Revy P, Brousse N, Lepelletier Y, Folli C, Durandy A, Chambon P, Dy M. Retinoids regulate survival and antigen presentation by immature dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:623–634. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tao Y, Yang Y, Wang W. Effect of all-trans-retinoic acid on the differentiation, maturation and functions of dendritic cells derived from cord blood monocytes. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology. 2006;47:444–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medina EA, Morris IR, Berton MT. Phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase activation attenuates the TLR2-mediated macrophage proinflammatory cytokine response to Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:7562–7572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arbibe L, Mira JP, Teusch N, Kline L, Guha M, Mackman N, Godowski PJ, Ulevitch RJ, Knaus UG. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated NF-kappa B activation requires a Rac1-dependent pathway. Nature immunology. 2000;1:533–540. doi: 10.1038/82797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fukao T, Koyasu S. PI3K and negative regulation of TLR signaling. Trends in immunology. 2003;24:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu Y, Nagai S, Wu H, Neish AS, Koyasu S, Gewirtz AT. TLR5- mediated phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation negatively regulates flagellin- induced proinflammatory gene expression. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:6194–6201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guha M, Mackman N. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway limits lipopolysaccharide activation of signaling pathways and expression of inflammatory mediators in human monocytic cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:32124–32132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin M, Schifferle RE, Cuesta N, Vogel SN, Katz J, Michalek SM. Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-Akt pathway in the regulation of IL-10 and IL-12 by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. Journal of immunology. 2003;171:717–725. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327:291–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, Tran G, Jabri B, Chatila TA, Mazmanian SK. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science. 2011;332:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shen Y, Giardino Torchia ML, Lawson GW, Karp CL, Ashwell JD, Mazmanian SK. Outer membrane vesicles of a human commensal mediate immune regulation and disease protection. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lai Y, Di Nardo A, Nakatsuji T, Leichtle A, Yang Y, Cogen AL, Wu ZR, Hooper LV, Schmidt RR, von Aulock S, Radek KA, Huang CM, Ryan AF, Gallo RL. Commensal bacteria regulate Toll-like receptor 3- dependent inflammation after skin injury. Nature medicine. 2009;15:1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nm.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.