Abstract

Caffeic acid (3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid) is a well-known phenolic phytochemical present in coffee and reportedly has anticancer activities. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms and targeted proteins involved in the suppression of carcinogenesis by caffeic acid are not fully understood. In this study, we report that caffeic acid significantly inhibits colony formation of human skin cancer cells and EGF-induced neoplastic transformation of HaCaT cells dose-dependently. Caffeic acid topically applied to dorsal mouse skin significantly suppressed tumor incidence and volume in a solar UV-induced skin carcinogenesis mouse model. A substantial reduction of phosphorylation in mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling was observed in mice treated with caffeic acid either before or after solar UV exposure. Caffeic acid directly interacted with ERK1/2 and inhibited ERK1/2 activities in vitro. Importantly, we resolved the co-crystal structure of ERK2 complexed with caffeic acid. Caffeic acid interacted directly with ERK2 at amino acid residues Q105, D106 and M108. Moreover, A431 cells expressing knockdown of ERK2 lost sensitivity to caffeic acid in a skin cancer xenograft mouse model. Taken together, our results suggest that caffeic acid exerts chemopreventive activity against solar UV-induced skin carcinogenesis by targeting ERK1 and 2.

Keywords: caffeic acid, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades, solar UV, two-stage skin cancer model, skin cancers, melanoma

Introduction

Coffee is among the most widely consumed beverages in the world. More than 50% of Americans drink coffee daily. The consumption of around 4 cups of coffee a day is associated with a 38% lower risk of breast cancer in pre-menopausal women (1). Consumption of at least 5 cups of coffee a day is associated with a 40% lower risk of brain tumors in humans compared with non-coffee drinkers (2). Recent results also show that daily consumption of 6 or more cups of coffee is associated with a 30% reduced prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (3). Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the U.S. with over 1 million new cases reported each year, comprising approximately 40% of all diagnosed cancers (4). Epidemiological evidence suggests that solar ultraviolet (SUV, i.e., sunlight) irradiation is the most important risk factor for skin carcinogenesis (5, 6)

Caffeic acid (3, 4-dihydroxy cinnamic acid) is the major phenolic compound naturally found in coffee. A 200 mL cup of coffee provides about 35–175 mg of caffeic acid. Caffeic acid reportedly exerts a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory and neuroprotective activities (7–9). Recent studies suggest that caffeic acid has anticancer effects against human renal carcinoma (10) and colon cancer metastasis (11). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms and targeted proteins involved in the suppression of carcinogenesis by caffeic acid are not fully understood.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway encompasses different signaling cascades of which the Ras-Raf-MEK-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) pathway is one of the most commonly deregulated in human cancer. This pathway mediates multiple cellular functions, including proliferation, growth and senescence (12). Abnormalities in ERKs signaling were reported in approximately 1/3 of all human cancers, including lung, liver and melanoma (13). SUV irradiation activates ERKs in human skin (14) and compared to actinic keratosis (AK), squamous cell carcinomas show higher ERKs phosphorylation (15). Hyperactivation of ERKs results in deregulated cell proliferation in several human cancers, including skin cancer (16, 17), suggesting that inhibition of ERKs signaling represents a potential approach for SUV-induced skin cancer prevention.

Here, we report the co-crystal structure of caffeic acid with ERK2 and show that caffeic acid directly inhibited SUV-induced activation of ERK1/2 and suppressed ERKs signaling. Treatment of dorsal mouse skin with caffeic acid either before or after SUV exposure strongly reduced skin tumor number and size in mice.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Caffeic acid was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Active ERK1 and 2 human recombinant proteins for kinase assays were from Millipore (Temecula, CA). Antibodies to detect total ERK1 and 2, phosphorylated Elk1 (Ser383), total Elk1, and phosphorylated p90RSK (Thr359/Ser363) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against phosphorylated ERK1 and 2 (Thr202/Tyr204), total p90RSK, phosphorylated c-Myc (Thr58/Ser62), total c-Myc and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The antibody to detect Ki-67 was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). CNBr-Sepharose 4B beads were from GE Healthcare (Pittsburgh, PA).

Solar UV (SUV) irradiation system

The SUV resource was comprised of UVA-340 lamps (Q-Lab Corporation; Cleveland, OH), which provide the best possible simulation of sunlight in the critical short wavelength region from 365 nm down to the solar cutoff of 295 nm with a peak emission of 340 nm. The percentage of UVA and UVB of the UVA-340 lamps was measured by a UV meter as 94.5% and 5.5%, respectively.

Cell culture and transfection

A431 skin cancer cells and HaCaT keratinocytes were cultured with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. SK-MEL-5 and SK-MEL-28 melanoma cells were cultured with minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Cells were cytogenetically tested and authenticated before being frozen. Each vial of frozen cells was thawed and maintained in culture for a maximum of 8 wk. Cells were kept at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For transfection experiments, the jetPEI (Qbiogen, Inc.) transfection reagent was used following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Primary mouse keratinocyte harvest and culture

SKH1 hairless mice were euthanized and the dorsal skin was removed. All subcutaneous tissue was scraped from the skin until the skin was semi-translucent. The skin (hairy side up) was spread out on a dish and cut into 0.5 × 1 cm strips. Trypsin without EDTA (20 ml, 0.25%) was added to the dish, and the dish was placed in a 37°C incubator for 1.5 h. DMEM/10% FBS (20 ml) is added and the epidermis scraped off into the medium. The medium was collected and stirred at 100 rpm on a magnetic stirrer for 20 min. The medium is filtered through a sterile 70 μm Teflon mesh and the filtrate centrifuged. The keratinocyte growth medium was added to re-suspend the cells and cells subsequently maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

MTS assay

To estimate cytotoxicity, cells were seeded (8×103 cells/well) in 96-well plates and cultured overnight. Cells were then fed with fresh medium and treated with different doses of caffeic acid. After culturing for various times, the cells were harvested and cytotoxicity of caffeic acid was measured using an MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3- carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazdium) assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Soft agar assay

Cells (8×103 /ml) were suspended in 1 ml of 0.3% Basal Medium Eagle (BME) top agar containing 10% FBS with various concentrations of caffeic acid and placed over a lower layer of solidified BME, 10% FBS, and 0.5% agar (3 ml) with the same concentrations of caffeic acid. The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1–2 weeks and then colonies were counted under a microscope using the Image-Pro Plus software (v.6) program (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

In silico target identification

The PHASE module of the Schrödinger’s molecular modeling software package (18) is a shape similarity method (19) and was used to search for biological targets of caffeic acid on the basis of its distinctive structure. The parameter of atom-type for volume was set to MacroModel, which means overlapping volumes are computed only between atoms that have the same MacroModel atom type. The target database was obtained from the Protein Data Bank and our in-house chemical library. To provide more structure orientations for possible alignment, we set the maximum number of conformers per molecule in the library to be generated at 100 while retaining up to 10 conformers per rotatable bond. We filtered out conformers with a similarity score below 0.70. Finally we obtained a final list of compounds with reported protein targets with a shape similarity score higher than 0.70.

ERK2 purification and crystallization

Purification of the full length (residues 1–360) human ERK2 was performed as described previously (20). Briefly, a His-tagged ERK2 protein was purified on HisPur Ni-NTA resin (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA); the His-tag removed by incubation with thrombin; and the protein was re-purified by FPLC on a Superdex ™ 200 column. Untagged ERK2 was crystallized in a sitting drops plate by mixing protein with precipitant solution comprised of 1.1 – 1.4 M ammonium sulfate, 2% PEG 500 MME, and 0.1 M HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5). The ERK2 crystals were soaked in precipitant solution containing 2.5 mM caffeic acid in 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 1–2 days. The crystals were cryo-protected in precipitant solution (1.8 M ammonium sulfate) with the addition of 20% xylitol, and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The ERK2 mutant, Q105A, was purified, crystallized and soaked with caffeic acid in a manner similar to wildtype ERK2. ERK2 was also co-crystallized with 2 mM AMP-PNP and 5 mM MgCl2 under similar crystallization conditions. Despite all attempts, electron density was clearly visible only for the adenosine moiety of AMP-PNP but not for any phosphate groups.

ERK2/caffeic acid co-crystal structure determination

The high-resolution diffraction data to a resolution of 1.8 Å were collected at the Advanced Photon Source NE-CAT beamline 24ID-E using a 30 × 50 micron beam and the Quantum 315 CCD detector. X-ray diffraction data were integrated and scaled using the HKL2000 package (21). The structure was resolved by molecular replacement using a starting model of the refined ERK2/norathyriol structure (PDB code 3SA0) (20). All calculations were performed using PHENIX (22). The coupling cycles of slow-cooling annealing, positional, restrained isotropic temperature factor and TLS refinements were followed by visual inspection of the electron density maps, including omit maps, coupled with a manual model re-built using the graphics program COOT (23). The refined electron density clearly matched the amino acid sequence of ERK2 with the exception of the N- and C-terminus (residues 1–5 and 358–360) and a weak electron density was observed for residues 23–34 and 336–340. The values of the free R-factor were monitored during the course of the crystallographic refinement and the final value of free R-factors did not exceed the overall R-factor by more than 4%. The structures of the ERK2 mutant Q105A and ERK2 in a complex with adenosine (AMP-PNP was used for co-crystallization) were refined using a similar protocol (data not shown). The coordinates and structure factors for ERK2 complexed with caffeic acid have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 4N0S.

In vitro ERK1 and 2 kinase assays

The recombinant nonphosphorylated His-tagged RSK2 (1 μg) was used as a substrate in an in vitro kinase assay with 200 ng of active ERK1 or 2 (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Reactions were conducted at 30°C for 60 min in kinase buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2) containing 100 μM unlabeled ATP with or without 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP. Reactions were stopped by adding 5x protein loading buffer and proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

In vitro pull-down assay

Caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B or Sepharose 4B beads were prepared as reported (24). For the in vitro or ex vivo pull-down assay, active ERK1 or 2 (200 ng) or lysates from HaCaT cells (1 μg) were mixed with 100 μL of caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B or Sepharose 4B beads in 400 μL of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% NP-40, and 2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin). After incubation with gentle rocking at 4°C overnight, the beads were washed 5X with washing buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.01% NP-40), and proteins bound to the beads were analyzed by Western blotting.

ATP and caffeic acid competition assay

For the ATP competition assay, active ERK2 (200 ng) was incubated with different concentrations of ATP (0, 10, or 100 μM) in reaction buffer at 4°C for 2 h. Caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B or Sepharose 4B beads (control) were added followed by incubation at 4°C for 2 h. After washing 5X with washing buffer, the proteins bound to the beads were analyzed by Western blotting.

Western blot analysis

For Western blotting, cells (2×106) were cultured in 10-cm dishes for 24 h. The cells were cultured in DMEM without FBS for 24 h to eliminate the influence of FBS on the activation of MAPKs. Cells were treated with caffeic acid (0–80 μM) for 1 h before being exposed to SUV (60 kJ UVA/m2, 3.6 kJ UVB/m2) and harvested 15 min later. Cells were disrupted on ice for 30 min in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, and 1 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfony fluoride)). After centrifugation at 20,817 x g for 15 min, the supernatant fraction was harvested as the total cellular protein extract. The protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent (Richmond, CA). Total cellular protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), containing 150 mM glycine and 20% (v/v) methanol. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and incubated with primary antibodies against phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-p90RSK, p90RSK, p-Elk1, Elk1, p-c-Myc, c-Myc, or β-actin at 4°C overnight. Blots were washed 3X in TBS-T buffer, followed by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG. Specific proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagent.

Xenograft mouse model

Female BALB/c (nu/nu) mice (6 wk old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and maintained under “specific pathogen-free” conditions. All studies were performed following guidelines approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Minneapolis, MN). Mice were divided into 6 groups (n = 8): (1) mice injected with A431 sh-mock cells and treated with vehicle; (2) mice injected with A431 sh-mock cells and treated with 10 mg/kg caffeic acid; (3) mice injected with A431 sh-mock cells and treated with 100 mg/kg caffeic acid; (4) mice injected with A431 sh-ERK2 cells and treated with vehicle; (5) mice injected with A431 sh-ERK2 cells and treated with 10 mg/kg caffeic acid; and (6) mice injected with A431 sh-ERK2 cells and treated with 100 mg/kg caffeic acid. Mice were administered vehicle (10% DMSO and 20% polyethylene glycol 400 in PBS) or caffeic acid in vehicle i.p. every day for 3 consecutive weeks beginning 3 days before injection of cells. A431 cells (3×106 in 50 μl PBS with 50 μl Matrigel) were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of each mouse. Tumor volume (length × width × depth × 0.52) was measured 3x/wk. Body weights were recorded once/week.

Mouse skin tumorigenesis study

Female SKH-1 hairless mice were purchased from Charles Rivers and maintained according to guidelines established by Research Animal Resources and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Minnesota. SKH-1 mice (5–6 wk old; 25 g mean body weight) were divided into 6 age-matched groups: 1) vehicle-treated (n = 12); 2) 20 μmol caffeic acid (n = 12); 3) vehicle + SUV (n = 15); 4) 10 μmol caffeic acid administered before SUV (n = 15); 5) 20 μmol caffeic acid administered before SUV (n = 15); 6) 20 μmol caffeic acid administered after SUV (n = 15). The dose of SUV was progressively increased (10% each week) because of the ensuing hyperplasia that can occur with SUV irradiation of the skin. The vehicle was acetone and SUV irradiation was administered 3X week for 15 wk with the dose at week 1 at 30 kJ/m2 UVA and 1.8 kJ/m2 UVB. At week 6, the dose of solar UV reached 48 kJ/m2 (UVA) and 2.9 kJ/m2 (UVB) and this dose was maintained until 15 wk. Mice were weighed and tumors measured by caliper once a week until week 29 or tumors reached a total volume of 1 cm3. At that point mice were euthanized and ½ of the dorsal skin was immediately fixed in 10% neural-buffered formalin and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry. The other half was frozen for Western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as means ± S.D. or S.E. as indicated. The Student t test or a one-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. A probability of p < 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

Caffeic acid inhibits human skin cancer cell colony formation and EGF-induced neoplastic transformation of HaCaT cells

In the present study, we examined the effect of caffeic acid (Fig. 1A) on human skin cancer cell colony formation and EGF-induced transformation of HaCaT cells. Treatment of A431 skin cancer cells or SK-MEL-5 and SK-MEL28 melanoma cells with caffeic acid significantly inhibited colony formation in soft agar in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). HaCaT cells were also treated with caffeic acid and was not cytotoxic (Supplementary Fig. 1A). However, caffeic acid dramatically inhibited EGF-promoted transformation dose-dependently (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Colony formation in soft agar is an ex vivo indicator and a key characteristic of the transformed cell phenotype (25) and these results indicate that caffeic acid can inhibit colony formation of human skin cancer cells and neoplastic transformation of HaCaT cells induced by EGF.

Fig. 1.

Caffeic acid reduces human skin cancer cell colony formation. A, chemical structure of caffeic acid. B, caffeic acid inhibits A431, SK-MEL-5, or SK-MEL-28 colony formation dose-dependently. Representative photographs are shown and data are represented as means ± S.D. of values from 3 independent experiments; the asterisk (*) indicates a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in colony formation in cells treated with caffeic acid compared with the DMSO-treated group.

ERKs are identified by in silico screening as plausible targets of caffeic acid

To identify potential targets of caffeic acid, we conducted in silico screening by using a small molecule shape similarity approach. Caffeic acid was screened against all the crystallized ligands available from the Protein Data Bank and our in-house natural compound library. Screening results showed that caffeic acid has a shape and pharmacophore similarity of 0.76 with ERK00071, which is a known ERK2 inhibitor. Thus, ERK2 was suggested as potential protein target of caffeic acid.

Caffeic acid inhibits ERK1/2 in vitro kinase activity and suppresses solar UV-induced activation of ERKs signaling

We performed an in vitro kinase assay using recombinant active ERK1 or 2 in the presence of various concentrations of caffeic acid. CAY10561, a well-known inhibitor of ERK2, was used as a positive control. The phosphorylation of RSK2, a well-known ERKs substrate, was inhibited by caffeic acid in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). We also performed an in vitro binding assay using caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads. No obvious band was observed when the recombinant active ERK 1 or 2 was incubated with control Sepharose 4B beads, whereas a strong band was seen when ERK1 or 2 was incubated with caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads (Fig. 2B). An ATP-competitive pull-down assay demonstrated that caffeic acid binds to ERK2 in an ATP competitive manner (Fig. 2C). Altogether, the results clearly indicate that caffeic acid binds to recombinant ERK 1 or 2 to inhibit their respective activity.

Fig. 2.

Caffeic acid inhibits ERKs kinase activities by directly binding with ERK1 or 2 in an ATP-competitive manner and attenuates MAP kinase signaling in primary mouse epidermal keratinocytes. A, a His-tagged-RSK2 fusion protein was used in an in vitro kinase assay with active ERK1 or 2 and results visualized by autoradiography. Coomassie blue staining serves as a loading control. B, caffeic acid directly binds with ERK1 or 2. Binding of caffeic acid with ERK1 or 2 was confirmed by Western blot. C, caffeic acid binds to ERK2 competitively with ATP. Active ERK2 (0.2 μg) was incubated with ATP at 0, 1, 10, 100 μM and 100 μL of caffeic acid-Sepharose 4B or Sepharose 4B (negative control) beads in reaction buffer in a final volume of 500 μL. Pulled down proteins were detected by Western blotting. D, after starvation in serum-free medium for 24 h, cells were treated with caffeic acid at the indicated concentration for 1 h, then exposed to solar UV (60 kJ UVA/m2, 3.6 UVB kJ/M2), incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 15 min and then harvested and protein levels determined by Western blotting.

To confirm the effect of caffeic acid on ERKs signaling, we used SUV to induce the activation of various ERKs substrates using primary mouse epidermal keratinocytes or HaCaT cells. The results show that caffeic acid inhibited SUV-induced phosphorylation of ERKs and also reduced phosphorylation of their downstream target proteins, including RSK2, c-Myc and Elk1 (26) (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Fig. 2).

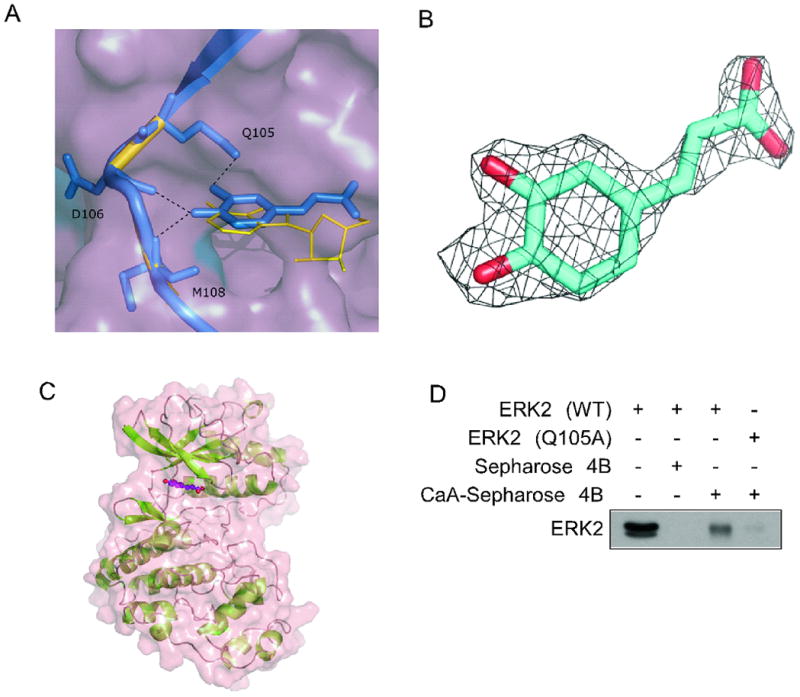

Co-crystal structure of caffeic acid and ERK2

To identify the binding mode of ERKs and caffeic acid, we resolved the crystal structure of ERK2 bound with caffeic acid at 1.8 Å resolution. The details of data collection and structure refinement for the ERK2/caffeic acid complex are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Caffeic acid is bound at the ATP-binding site (Fig. 3A–C). The catechol moiety of caffeic acid occupies a position at the adenine ring of AMP-PNP that is visible in electron density as adenosine. Two hydroxyl groups of caffeic acid form hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues of ERK2 located in the hinge region, including the carboxyl group of Q105 and the main chain of D106 and M108. To confirm the importance of the Q105 residue in binding with caffeic acid, we performed an in vitro pull-down binding assay using caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads. Compared with wildtype ERK2, a purified recombinant ERK2 mutant, Q105A, showed decreased binding with caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads (Fig. 3D). We attempted to obtain the Q105A mutant crystal structure bound with caffeic acid. However, no electron density of caffeic acid was observed in the refined structure of the Q105A mutant despite identical soaking experiments. This result suggests that the Q105A mutant was not able to strongly bind with caffeic acid in the crystallized form.

Fig. 3.

Crystal structure of the ERK2/caffeic acid complex. A, superimposition of ERK2 bound with caffeic acid and ERK2 bound with adenosine. The binding interactions within the hinge region are shown as dotted lines. The caffeic acid molecule (blue sticks) interacts with ERK2 amino acid residues Q105, D106, and M108. The catechol moiety of caffeic acid is positioned in the same plane as the adenine moiety of adenosine (yellow lines). The 3 AMP-PNP phosphate groups were invisible on the electron density map. B, electron density map 2Fo-Fc for caffeic acid was contoured at 1.5 σ. C, surface and ribbon representation of the ERK2/caffeic acid structure. Caffeic acid bound at the ATP-pocket is shown as ball and sticks. D, caffeic acid binding with a wildtype (WT) recombinant ERK2 compared to its binding with an ERK2 Q105A mutant. Proteins were incubated with caffeic acid-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads and analyzed by Western blot.

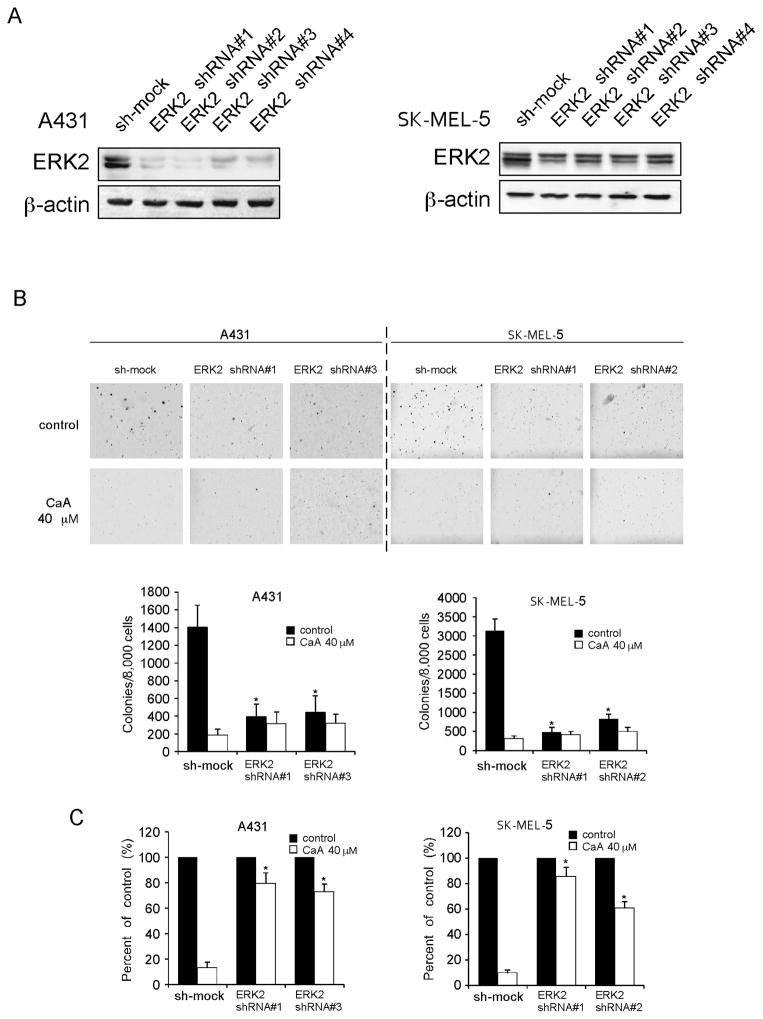

Knockdown of ERK2 decreases the anticancer effects of caffeic acid

We determined whether knocking down ERK2 expression could influence the sensitivity of human skin cancer cells or HaCaT cells to caffeic acid. We first determined the efficiency of shRNA knockdown, as well as the effect of shRNA transfection on anchorage-independent growth. The expression of ERK2 in each cell line was obviously decreased after shRNA transfection (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Colony number dramatically decreased after ERK2 shRNA transfection compared with sh-mock group (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Fig. 3B). Next, cells transfected with ERK2 shRNA or sh-mock were treated with caffeic acid or vehicle and subjected to a soft agar assay. The results showed that caffeic acid (40 μM) inhibited colony formation of each cell type transfected with sh-mock by more than 80%. In contrast, the same dose of caffeic acid inhibited colony formation of each cell type transfected with ERK2 shRNA by no more than 50% (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. 3C). These results suggested that ERK2 plays an important role in the sensitivity of human skin cancer cells or HaCaT cells to the antiproliferative effects of caffeic acid.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of ERK2 in human skin cancer cells decreases sensitivity to caffeic acid. A, efficiency of ERK2 shRNA in A431 and SK-MEL-5 cells. B, colony formation of A431 and SK-MEL-5 cells transfected with sh-mock, ERK2 shRNA#1, shRNA#2, shRNA#3 or shRNA#4. Colony number dramatically decreased after ERK2 shRNA transfection compared with the sh-mock group. Data are shown as means ± S.D. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant decrease in colony number compared with sh-mock group (p < 0.05). C, sensitivity of skin cancer cells transfected with sh-mock or ERK2 shRNA to treatment with caffeic acid (40 μM). Data are shown as means ± S.D. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant decrease in sensitivity to caffeic acid (p < 0.05).

Using a xenograft model, we found that administration of vehicle or caffeic acid (10 or 100 mg/kg) had no effect on body weight (Fig. 5A). More importantly, we observed that knocking down ERK2 expression decreased xenograft tumor volume (Fig 5B, C), but also decreased the sensitivity of xenograft skin cancer growth to caffeic acid (Fig 5B, D). These results indicated that when ERK2 levels were decreased, caffeic acid lost the ability to exert its preventive effects against skin cancer development.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of ERK2 decreases preventive effects of caffeic acid against skin cancer development in a xenograft mouse model. A, caffeic acid does not affect mouse body weight. Mice were treated with caffeic acid or its vehicle i.p. once/day for 3 weeks. Body weight of each mouse was measured once/week and data are represented as means ± S.D. B, representative photographs of mice from each group injected with sh-mock or ERK2 shRNA#1 A431 cells. At 19 days after injection of A431 cells, mice were euthanized with CO2. C, knockdown of ERK2 suppresses tumor growth in an A431 xenograft mouse model. D, knockdown of ERK2 decreases preventive effects of caffeic acid against skin cancer development. Mice either injected with A431 sh-mock or A431 ERK2 shRNA#1 cells were given caffeic acid or vehicle as described in Materials and Methods.

In all groups, tumor volume was measured 3 × week after injection with A431 cells. Data are represented as means ± S.D. and the asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) in tumor volume (mm3).

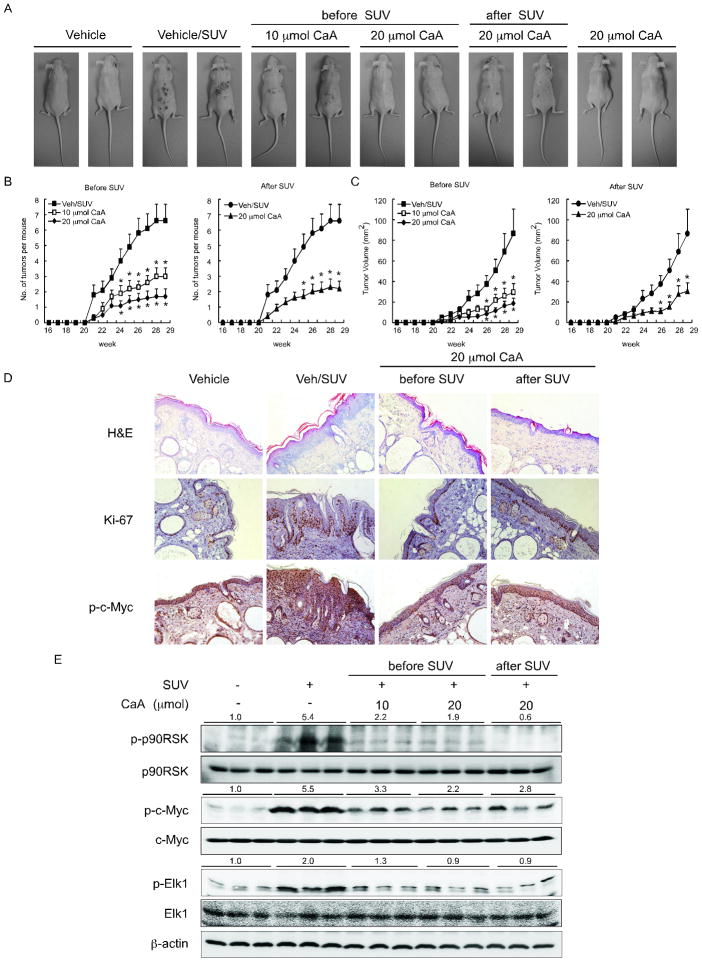

Caffeic acid suppresses SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice in vivo

To further study the anti-tumorigenic activity of caffeic acid in vivo, we evaluated the effect of caffeic acid in a SUV-induced mouse skin tumorigenesis model. We used SUV to mimic sunlight because although UVB is a major etiologic factor for the development of skin cancer, UVA is the most abundant component of SUV irradiation (5). The results demonstrated that topical application of caffeic acid to dorsal skin inhibited skin cancer development in mice that were exposed to SUV compared with mice treated with vehicle only and exposed to SUV (Fig. 6A). Caffeic acid (10 or 20 μmol) significantly inhibited the average number (p < 0.05, Fig. 6B) or volume (p < 0.05, Fig. 6C) of tumors per mouse. Notably, application of caffeic acid either before or after UV resulted in similar observations–a significant reduction in tumor formation. Skin and tumor samples were processed for H&E and immunohistochemistry staining. After treatment with SUV, epidermal thickness in the vehicle/SUV group was increased by edema and epithelial cell proliferation, whereas caffeic acid-treated groups showed a smaller increase in epidermal thickness and less inflammation (Fig. 6D). Immunohistochemistry data showed that Ki-67, which is a well-known cellular marker for proliferation, was dramatically increased in the vehicle + SUV group compared with the vehicle group. However, Ki-67 expression was decreased in the SUV-caffeic acid treated groups, compared with vehicle/SUV group (Fig. 6D). The immunohistochemistry staining for phosphorylation of c-Myc, which is downstream of ERKs, showed a significantly reduced level of phosphorylation in mice treated with caffeic acid (Fig. 6D). In addition, Western blotting analysis of mouse skin showed that the phosphorylation of p90RSK, c-Myc and Elk1 induced by SUV was dramatically suppressed in the caffeic acid-treated groups (Fig. 6E). Overall, these results indicate that caffeic acid might serve as an effective chemopreventive agent against SUV-mediated skin cancer acting by suppressing the activity of ERKs.

Fig. 6.

Caffeic acid inhibits solar UV-induced skin tumorigenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice. A, external appearance of tumors. B, average tumor number and C, tumor volume per mouse. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: tumor volume (mm3) = (length × width × height × 0.52). Data are represented as means ± S.E. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the solar UV groups treated or not treated with caffeic acid. At the end of the study, 1/2 of the skin and tumor samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and processed for D, H&E staining and immunohistochemistry with specific primary antibodies to detect Ki-67 and p-c-Myc. E, the other half of the skin and tumor samples was analyzed for protein expression by Western blotting.

Discussion

Many research groups have observed that coffee consumption is linked to a reduced risk of several cancers, including liver, colorectal, mouth and throat cancer and breast cancer in pre-menopausal women (1, 27–31),(11). Caffeic acid is one of the main metabolites produced by the hydrolyzation of chlorogenic acid, a major phenolic phytochemical found in various foods, especially coffee. Previous studies have shown that caffeic acid inhibits skin tumor promotion induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol–13-acetate in mouse skin (31). Also caffeic acid has been implicated as a protective agent against UVB-induced skin damage (32). Although accumulating evidence suggests that caffeic acid has the potential to inhibit skin cancer development, the actual effects and the molecular mechanisms remain unclear. In the present study, we showed a chemopreventive effect of caffeic acid against SUV-induced skin cancer development and identified ERK1 and 2 as its possible protein targets.

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight is the most prominent and ubiquitous physical carcinogen in our natural environment. Studies have shown that is an important for development of both nonmelanoma skin cancer and melanoma (33). Cells respond to signals produced from UV exposure by activating signaling cascades including the MAPK pathway. MAPKs regulate multiple critical cellular functions, including proliferation, growth and senescence (34). Studies in various skin cell lines demonstrated that epidermal growth factor receptors (35), MAPKs (36) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (37) are specific signaling molecules in UVB- induced skin carcinogenesis. Some studies showed that when HaCaT cells were irradiated by UVB (0.2 kJ/m2), ERK1 and 2 were phosphorylated after 15 min and remained activated for 6 h (38). In our previous study, phosphorylation of ERKs and RSK2 was increased by exposure to UVB (4 kJ/m2) in HaCaT cells (39), suggesting that ERKs might be a useful anticancer target.

In the present work, we showed that caffeic acid effectively inhibited colony formation of human skin cancer cells and EGF-induced neoplastic transformation of HaCaT cells (Fig 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Long-term topical treatment of mouse dorsal skin with caffeic acid either before or after solar UV significantly reduced skin tumor formation (Fig. 6). The Ki-67 protein is a known cellular marker for proliferation (40) and our IHC results showed that expression of Ki-67 was dramatically decreased after treatment with caffeic acid.

We provided systemic evidence indicating that caffeic acid directly targets ERKs. According to our ERK2/caffeic acid co-crystal structure (Fig. 3), caffeic acid strongly binds to the ATP-binding cleft through the formation of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl-groups and amino acids Q105, D106 and M108 located at the hinge loop. This is the best evidence available showing that caffeic acid can target ERKs at the molecular level. We further showed that caffeic acid suppressed SUV-induced ERKs phosphorylation and downstream signaling in primary mouse epidermal keratinocytes and HaCaT cells (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Fig. 2). Caffeic acid was highly effective in decreasing SUV-induced skin carcinogenesis, in vivo, whether applied before or after exposure to SUV (Fig. 6A, B). Western blot analysis of mouse skin tissue clearly confirmed that the SUV-induced phosphorylation of several of ERKs’ downstream targets, including RSK2, Elk1 and c-Myc, was suppressed by caffeic acid (Fig. 6D). In addition, knocking down ERK2 expression decreased the sensitivity of human skin cancer cells and HaCaT cells to caffeic acid treatment (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. 3). Finally, we used a skin cancer xenograft model to provide in vivo evidence showing that low levels of ERK2 attenuated the ability of caffeic acid to exert its preventive effects against skin cancer development (Fig 5).

Taken together, our results clearly showed that topical application of caffeic acid markedly suppressed the formation of skin cancer in SKH-1 hairless mice exposed to SUV. Caffeic acid functioned as a potent inhibitor of ERK1 and 2 and suppressed the activity of their downstream substrates, RSK2, Elk1 and c-Myc. Therefore, caffeic acid might be a good chemopreventive agent that is highly effective against SUV-induced skin cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The crystallography work is based upon research conducted at the Advanced Photon Source on the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which is supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41 GM103403) from the National Institutes of Health. The use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by the Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The remainder of the work presented was supported by The Hormel Foundation and National Institutes of Health Grants (Zigang Dong) R37 CA081064, CA166011, CA172457, and ES016548.

Footnotes

Notes: Ge Yang, Yang Fu, Margarita Malakhova contributed equally to this work.

Competing Financial Statement: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Arab L. Epidemiologic evidence on coffee and cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62:271–83. doi: 10.1080/01635580903407122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick CN, Smith SG, Giovannucci E, Michaud DS. Coffee, tea, caffeine intake, and risk of adult glioma in three prospective cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:39–47. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abel EL, Hendrix SO, McNeeley SG, Johnson KC, Rosenberg CA, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, et al. Daily coffee consumption and prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in Caucasian women. European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation. 2007;16:446–52. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000243850.59362.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricotti C, Bouzari N, Agadi A, Cockerell CJ. Malignant skin neoplasms. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:1241–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berwick M, Lachiewicz A, Pestak C, Thomas N. Solar UV exposure and mortality from skin tumors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;624:117–24. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Gruijl FR. Skin cancer and solar UV radiation. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:2003–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung TW, Moon SK, Chang YC, Ko JH, Lee YC, Cho G, et al. Novel and therapeutic effect of caffeic acid and caffeic acid phenyl ester on hepatocarcinoma cells: complete regression of hepatoma growth and metastasis by dual mechanism. FASEB J. 2004;18:1670–81. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2126com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka T, Kojima T, Kawamori T, Wang A, Suzui M, Okamoto K, et al. Inhibition of 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide-induced rat tongue carcinogenesis by the naturally occurring plant phenolics caffeic, ellagic, chlorogenic and ferulic acids. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:1321–5. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.7.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sul D, Kim HS, Lee D, Joo SS, Hwang KW, Park SY. Protective effect of caffeic acid against beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity by the inhibition of calcium influx and tau phosphorylation. Life sciences. 2009;84:257–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung JE, Kim HS, Lee CS, Park DH, Kim YN, Lee MJ, et al. Caffeic acid and its synthetic derivative CADPE suppress tumor angiogenesis by blocking STAT3-mediated VEGF expression in human renal carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1780–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang NJ, Lee KW, Kim BH, Bode AM, Lee H-J, Heo Y-S, et al. Coffee phenolic phytochemicals suppress colon cancer metastasis by targeting MEK and TOPK. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:921–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Wong EW, Chang F, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1263–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HH, Cho S, Lee S, Kim KH, Cho KH, Eun HC, et al. Photoprotective and anti-skin-aging effects of eicosapentaenoic acid in human skin in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:921–30. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500420-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Einspahr JG, Calvert V, Alberts DS, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Warneke J, Krouse R, et al. Functional protein pathway activation mapping of the progression of normal skin to squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:403–13. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohori M, Kinoshita T, Okubo M, Sato K, Yamazaki A, Arakawa H, et al. Identification of a selective ERK inhibitor and structural determination of the inhibitor-ERK2 complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo AE, Torrisi E, Bevelacqua Y, Perrotta R, Libra M, McCubrey JA, et al. Melanoma: molecular pathogenesis and emerging target therapies (Review) Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1481–9. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrödinger. Schrödinger Suite 2012. Vol. 2012 Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Yao K, Nadas J, Bode AM, Malakhova M, Oi N, et al. Prediction of molecular targets of cancer preventing flavonoid compounds using computational methods. PloS one. 2012;7:e38261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Malakhova M, Mottamal M, Reddy K, Kurinov I, Carper A, et al. Norathyriol suppresses skin cancers induced by solar ultraviolet radiation by targeting ERK kinases. Cancer Res. 2012;72:260–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276 doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–54. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung SK, Lee KW, Byun S, Kang NJ, Lim SH, Heo YS, et al. Myricetin suppresses UVB-induced skin cancer by targeting Fyn. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6021–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedman VH, Shin SI. Cellular tumorigenicity in nude mice: correlation with cell growth in semi-solid medium. Cell. 1974;3:355–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raman M, Chen W, Cobb MH. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene. 2007;26:3100–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu X, Bao Z, Zou J, Dong J. Coffee consumption and risk of cancers: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nkondjock A. Coffee consumption and the risk of cancer: an overview. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turati F, Galeone C, La Vecchia C, Garavello W, Tavani A. Coffee and cancers of the upper digestive and respiratory tracts: meta-analyses of observational studies. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:536–44. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavani A, La Vecchia C. Coffee, decaffeinated coffee, tea and cancer of the colon and rectum: a review of epidemiological studies, 1990–2003. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:743–57. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000043415.28319.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang MT, Smart RC, Wong CQ, Conney AH. Inhibitory effect of curcumin, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid on tumor promotion in mouse skin by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5941–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staniforth V, Chiu LT, Yang NS. Caffeic acid suppresses UVB radiation-induced expression of interleukin-10 and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in mouse. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1803–11. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bode AM, Dong Z. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in UV-induced signal transduction. Science’s STKE : signal transduction knowledge environment. 2003;2003:RE2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.167.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohno M, Pouyssegur J. Targeting the ERK signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Ann Med. 2006;38:200–11. doi: 10.1080/07853890600551037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan YS, Wang ZQ, Shao Y, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Ultraviolet irradiation activates PI 3-kinase/AKT survival pathway via EGF receptors in human skin in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:461–6. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen W, Tang Q, Gonzales MS, Bowden GT. Role of p38 MAP kinases and ERK in mediating ultraviolet-B induced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2001;20:3921–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabuyama Y, Hamaya M, Homma Y. Wavelength specific activation of PI 3-kinase by UVB irradiation. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He YY, Huang JL, Chignell CF. Delayed and sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in human keratinocytes by UVA: implications in carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53867–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho YY, Lee MH, Lee CJ, Yao K, Lee HS, Bode AM, et al. RSK2 as a key regulator in human skin cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:2529–37. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.