Abstract

Naïve T cell populations are maintained in the periphery at relatively constant levels via mechanisms that control expansion and contraction, and are associated with competition for homeostatic cytokines. It has been shown that in a lymphopenic environment naïve T cells undergo expansion due, at least in part, to additional availability of IL-7. We have previously found that T cell-intrinsic deletion of TRAF6 (TRAF6ΔT) in mice results in diminished peripheral CD8 T cell numbers. We now report that while naïve TRAF6ΔT CD8 T cells exhibit normal survival when transferred into a normal T cell pool, proliferation of naïve TRAF6ΔT CD8 T cells under lymphopenic conditions is defective. We identified IL-18 as a TRAF6-activating factor capable of enhancing lymphopenia-induced proliferation (LIP) in vivo, and that IL-18 synergizes with high dose IL-7 in a TRAF6-dependent manner to induce slow, LIP/homeostatic-like proliferation of naïve CD8 T cells in vitro. IL-7 and IL-18 act synergistically to upregulate expression of IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) genes, thereby enhancing IL-18 activity. In this context, IL-18R signaling increases PI3 kinase activation and was found to sensitize naïve CD8 T cells to a model non-cognate self-peptide ligand in a way that conventional costimulation via CD28 could not. We propose synergistic sensitization by IL-7 and IL-18 to self-peptide ligand may represent a novel costimulatory pathway for LIP.

Introduction

CD8 T cells are primary facilitators of adaptive immune killing in response to intracellular infections and tumors, and undergo vigorous expansion and differentiation in response to cognate antigen (1, 2). For proper immune function, it is critical not only for subsets of responding antigen-specific CD8 T cells to acquire memory cell function, but also to maintain peripheral steady-state homeostasis of the broader CD8 T cell compartment (2-4). With age, thymic involution and chronic viral infections both contribute to diminution of the naïve CD8 T cell pool (5, 6). In clinical contexts, the effects of lymphopenia on CD8 T cell homeostasis are significant for anti-retroviral treatment of HIV infection, T cell-ablative therapy associated with bone marrow transplant, and lymphopenia-induced autoimmunity following transplant (7-9). Elsewhere, there is evidence that mimicking lymphopenic conditions may provide therapeutic benefits for enhancing CD8 T cell anti-tumor responses (10, 11). Therefore, understanding both the extracellular stimuli and the cell-intrinsic mechanisms that enable naïve CD8 T cells to adapt to lymphopenic conditions are of considerable interest.

Lymphopenia-induced proliferation (LIP) (sometimes also “homeostatic” or “cognate antigen-independent” proliferation) occurs more slowly than cognate antigen-induced proliferation, and may be triggered by increased availability of the homeostatic cytokine IL-7 (or possibly IL-15) that occurs in the absence of competing cells (3, 8, 12). LIP also requires below-threshold “tonic” T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation provided by low affinity self-peptides, and cells undergoing LIP do not blast or produce significant levels of effector cytokines (3, 13, 14). Interestingly, while enhanced IL-7 receptor signaling is known to be essential for LIP in vivo, it is difficult to recapitulate or model this type of proliferation in vitro, suggesting additional signals may also be required. Emerging use of IL-7 in clinical contexts of lymphopenia involving cancer or after allogeneic stem cell transplant highlights the importance of identifying complementary factors and characterizing their relevant signaling mechanisms (15, 16).

By focusing on cell-intrinsic homeostatic mechanisms in the context of CD8 T cell biology, we previously identified TRAF6-dependent signaling as critical to maintenance of the CD8 T cell pool using T cell-specific TRAF6-deficient mice (TRAF6ΔT) (17, 18). The TRAF6 E3 ubiquitin ligase is activated by TGFβR, TLR/IL-1R, and TNFR superfamilies and further activates downstream pathways NFκB, MAPK, and NFAT (19, 20). While we have previously determined that TRAF6ΔT CD8 T cells stimulated with cognate antigen are hyper-responsive (17, 18), we now show that naïve cells exhibit defective LIP.

By focusing on known TRAF6-dependent pathways that may operate in naïve CD8 T cells, we identified the IL-1 family member, IL-18 (21, 22), as a factor that enhances LIP in vivo, and that synergizes with IL-7 in vitro to sensitize naïve CD8 T cells to self-peptide. This mechanism appears distinct from conventional CD28 costimulation, and may represent a novel form of costimulation that could enable better understanding of the signals that control LIP, and possibly improve clinical intervention strategies for boosting (or controlling) peripheral T cell pools.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Antibodies

Western blotting antibodies specific for pAkt (S473), Akt, Bcl-xL, Cdk6, Cyclin D3 were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). For cell culture, αCD3 (2C11) and αCD28 (37.51) were prepared in-house or purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ), αMHC-I neutralizing antibody (Y-3) was provided by Philippa Marrak (Denver, CO), and mouse IgG2b isotype control antibody was purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). For flow cytometry, αCD90.1-Pacific Blue, αCD8-APC-Alexa750, αCD4-Pacific Blue, αCD45.1-APC-Alexa750, αCD44-FITC, αCD69-FITC, Rat IgG2b-APC, and Armenian Hamster IgG FITC were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and αCD8-FITC, αCD45.2-PerCP-Cy5.5, and αCD90.2-APC were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). For ELISA, αIFNγ capture and detection antibodies, as well as detection reagents were purchase from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Recombinant murine IL-12, and IL-7 were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Recombinant murine IL-18 and IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). For CFSE proliferation staining, CFDA-SE was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). For survival assays, 7AAD vital dye was purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Purified peptides based on the chicken ovalbumin protein sequence, OVA (257-264) and OVA (E1 mutant), were purchased from Anaspec (Fremont, CA).

Mice

Mice conditionally deficient for TRAF6 in the T cell compartment (TRAF6ΔT) were generated by crossing TRAF6flox/flox mice with CD4-Cre transgenic mice obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). CD45.1 congenic mice (5-8 weeks of age) were purchased from the NCI Mouse Repository (Frederick, MD) to be used as recipients for adoptive transfer experiments. STAT5b-CA transgenic mice were obtained from Michael Farrar (University of Minnesota). OT-I TCR transgenic mice, and CD90.1 congenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were crossed to the C57BL/6 at least 10 times. Unless otherwise indicated, tissues were harvested from mice between 4 and 8 weeks of age. Mouse care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with protocols from Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Pennsylvania.

In Vivo Lymphopenia-induced Proliferation

For all experiments involving polyclonal donor mice, and some experiments involving OT-I TCR transgenic donor mice, spleen and lymph node cells were harvested, and sorted by FACS for CD8+CD62LhiCD44lo T cells. Alternatively, in some experiments involving young OT-I TCR transgenic donor mice, CD8 T cells were purified from lymph nodes using MACS, and the CD62LhiCD44lo phenotype assayed by flow cytometry to confirm >95% naïve phenotype before proceeding. In all cases, donor cells were washed twice with PBS, before being labeled with 5μM CFSE or left unlabeled, and injected intravenously into either RAG1 knockout or irradiated (700 rads) CD45.1 congenic recipient mice (1.5-2×106 per mouse). Cells were harvested and analyzed 7 days post-transfer unless otherwise indicated. For quantitative analysis of CD8+ T cell expansion/survival in a lymphopenic environment, CD45.2+CD90.2+ naïve CD8+ test cells were mixed 1:1 with naïve CD8+CD45.2+CD90.1+ reference cells prior to either CFSE labeling or transfer into at least 3 irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice per genotype per timepoint. Tissues were harvested, processed and analyzed as before, with donor cells distinguished from recipient cells by CD45.2/CD45.1, and test (control/TRAF6ΔT) cells distinguished from reference cells by CD90.2/CD90.1. At each timepoint, ratios of test cells to reference cells were calculated for each mouse, and means and standard deviations calculated for ratios across groups of mice receiving the same test genotype. For experiments involving gene expression during LIP cells were sorted based on CD45.2 by FACS directly into Trizol reagent. For experiments involving in vivo treatment with IL-18, mice were treated with PBS or 400ng recombinant IL-18 daily, intravenously, for the length of the experiment.

In Vitro T Cell Cultures

Naïve (CD62LhiCD44lo) T cells were obtained by FACS sorting (polyclonal and OT-I TCR transgenic) to yield >99% naïve phenotype or by CD8+ MACS (young OT-I or RAG1KO.OT-I only (though all OT-I experiments also included at least one replicate using FACS-sorted cells)) to yield >95% naïve phenotype. Cells were typically cultured at 40,000 per well in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, L-Glutamine, and 2-Mercaptoethanol (all purchased from Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) in 96 well round-bottom tissue culture-treated plates. Relative cell counts of culture wells were made by acquiring equal volumes for the same period of time on a FAC Calibur flow cytometer at high flow rate. For CFSE labeling, cells were resuspended in PBS without serum at 5-10×106/mL, then mixed 1:1 with PBS containing 10μM CFSE. Labeling suspensions were rocked at room temperature for 5 minutes, and then quenched with 20% FBS. Cells were washed twice with serum-containing medium before being prepared for culture or transfer. Cells treated with αMHC-I (Y-3; 10μg/mL) neutralizing antibody or LY294002 PI3K inhibitor were pre-treated with these reagents in culture for 30 minutes prior to addition of activating cytokines. For cell cultures of 6 days or longer, half the culture medium was replaced every 3 days.

Flow Cytometry

Purified cultured cells harvested for flow cytometric analysis were stained with 7AAD vital dye and assayed on a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ) for 30 seconds per tube at high flow rate to attain consistent cell counts. For adoptive transfer analysis, cell suspensions were stained on ice for 30 minutes in PBS plus 2% serum and 0.1% sodium azide (w/v) with antibodies against CD90.2 and CD8 to identify CD8+ T cells, CD45.1 and CD45.2 to distinguish recipient and donor cells, respectively, and, in some cases, CD90.2 and CD90.1 to distinguish test cells from reference cells. These cells were analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ).

ELISA

Cell culture supernatants were harvested after 60 hours of culture, and stored frozen. Once thawed, multiple dilutions were prepared, along with titrations of IFNγ standard. Supernatants were incubated on capture antibody-coated ELISA plates for 2 hours, followed by incubation with detection antibody and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour. Plates were washed repeatedly with PBS + 0.05% Tween-20. Substrate solution was added for 30 minutes, followed by 0.1M phosphoric acid, at which point plates were read at 450nm with a 570nm correction.

Western Blotting

1-2×106 purified naïve T cells per sample were harvested as indicated with ice-cold PBS plus phosphatase inhibitor (Active Motif; Carlsbad, CA), pelleted, and lysed with 100μL lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche; Basel, Switzerland), 2mM sodium ortho-vanadate, 2mM NaF, 100ng/mL Calyculin A (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA), with 1.0% (w/v) Triton-X100. Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 minutes, and clarified by centrifugation at 20,000xg for 10 minutes. 5μL of each lysate was used for determining protein concentration, and lysates were normalized accordingly. Extracts were aliquotted, added to 6X SDS loading buffer and boiled. Samples were run on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore; Billerica, MA). Blots were probed with primary antibodies in 5% milk dissolved in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, followed by secondary anti-rabbit-HRP or anti-mouse-HRP (Promega; Madison, WI). Western blots were incubated with ECL substrate (Pierce; Rockford, IL) and exposed to film.

Real-Time PCR

Cells (typically 1-2×106 per condition) were cultured as indicated, harvested, pelleted, and lysed in 1mL Trizol reagent (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). RNA was prepared via separation with chloroform, precipitation with isopropanol, and washing with 75% ethanol. RNA was quantified with UV spectrometry. cDNA generation was accomplished by aliquotting 1μg RNA into 20μL Superscript II (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) reverse transcriptase reactions for 50 minutes, and then diluted with ddH20 to 750μL. 10μL of each cDNA stock was used for 25μL Real-Time PCR reactions containing 2X Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Norwalk, CT) and FAM-dye assay-on-demand primers (Applied Biosystems; Norwalk, CT) specific for indicated targets. Assays were performed in triplicate and normalized to 18S RNA using an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real Time PCR machine running Sequence Detection System software version 1.4.

Microarray

Freshly isolated naïve OT-I TCR transgenic CD8 T cells were cultured for 24 hours with low (0.1ng/mL) or high (1.0ng/mL) dose IL-7 in the presence or absence of 10ng/mL IL-18, then harvested, pelleted, and lysed with Trizol reagent, and RNA prepared as for Real-Time PCR samples. Total RNA was converted to first-strand cDNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase primed by a poly(T) oligomer that incorporated the T7 promoter. Second-strand cDNA synthesis was followed by in vitro transcription for linear amplification of each transcript and incorporation of biotinylated CTP and UTP. The cRNA products were fragmented to 200 nucleotides or less, heated at 99°-C for 5 minutes and hybridized for 16 hours at 45 °-C to 5 microarrays per group. The microarrays were then washed at low (6X SSPE) and high (100mM MES, 0.1M NaCl) stringency and stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin. Fluorescence was amplified by adding biotinylated anti-streptavidin and an additional aliquot of streptavidin-phycoerythrin stain. A confocal scanner was used to collect fluorescence signal at 3μm resolution after excitation at 570nm. The average signal from two sequential scans was calculated for each microarray feature.

Statistics

Unless otherwise indicated all experiments were performed a minimum of three times, with representative data depicted. For comparative in vitro cell count or Real-Time PCR analysis, triplicate wells were used for all conditions within a given experimental replicate, and differences determined by p-values of less than 0.05, as calculated on Microsoft Excel using the two-tailed equal variance Student's t-test. For comparative in vivo cell count analysis, three recipient mice were used for all conditions within a given experimental replicate, and differences determined by p-values of less than 0.05, as calculated on Microsoft Excel using the two-tailed equal variance Student's t-test.

Results

Naïve TRAF6-deficient CD8 T cells exhibit defective LIP

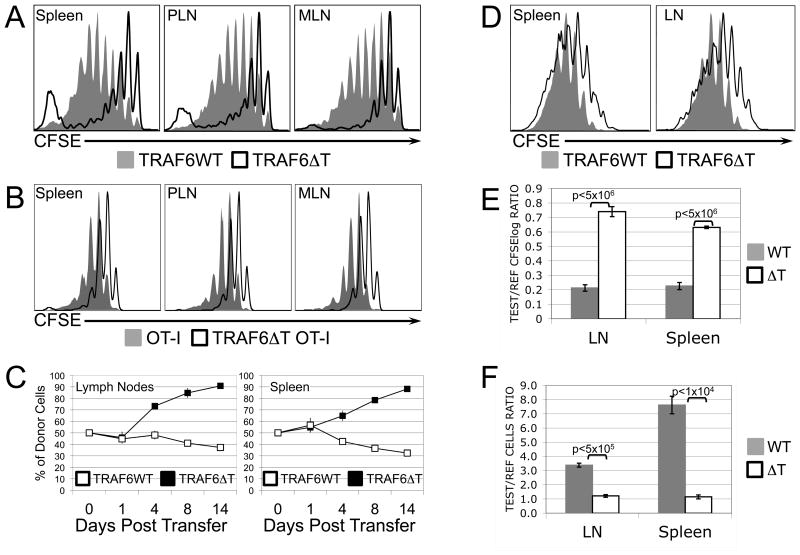

We have previously reported that TRAF6ΔT mice contain a diminished peripheral naïve CD8 T cell pool (17), but find that sorted naïve CD8 T cells from these mice transferred to a normal environment exhibit normal survival dynamics (Supplemental Fig. 1). In order to investigate the role that T cell-intrinsic TRAF6 might play in other homeostatic mechanisms, we examined the behavior of naïve TRAF6ΔT CD8 T cells under lymphopenic conditions. Sorted naïve CFSE-labeled control or TRAF6ΔT CD8 T cells were adoptively transferred into irradiated congenic recipient mice for 7 days. CFSE profiles of TRAF6ΔT donor cells harvested from recipient mice revealed a striking defect in the slow form of proliferation associated with lymphopenia (Fig. 1A). In addition to conventional cytokine-dependent LIP, polyclonal CD8 T cells undergo a spontaneous (or “chronic”) form of proliferation associated with commensal-derived antigens (23). To exclude the effects of spontaneous proliferation, we generated TRAF6ΔT.OT-I TCR transgenic mice, whose T cells are specific for the chicken ovalbumin peptide 257-264 in the context of H2-Kb. When naïve cells from these mice were transferred into lymphopenic recipients for 7 days, they exhibited a more uniform pattern of proliferation than the polyclonal cells, but again the TRAF6ΔT cells demonstrated a proliferative defect (Fig. 1B). To determine whether defects in proliferative profiles reflected population defects, control or TRAF6ΔT OT-I CD8 T cells were mixed in equal proportions with CD90.1 OT-I reference cells (co-transferred reference cells were used to minimize recipient variability effects in a given experiment), transferred to lymphopenic recipient mice, and then relative cell counts calculated from harvested recipient mouse tissues at various time points. Consistent with our observations of defective TRAF6ΔT LIP, we found that the population of TRAF6ΔT cells also progressively diminished relative to the total donor cell population over time (Fig. 1C). IL-7 signaling is critically important for normal progression of LIP. To address the possibility that defective IL-7 signaling results in reduced TRAF6ΔT LIP, we generated TRAF6ΔT.OT-I.STAT5bCAtg mice, which express a constitutively-active form of the IL-7R-activated transcription factor STAT5b (24), and performed additional LIP experiments using donor OT-I.STAT5bCAtg cells. Surprisingly, we found that while constitutively active STAT5b augmented LIP by both control and TRAF6ΔT cells, a relative proliferative defect in the TRAF6ΔT cells persisted (Fig. 1D). Further, when compared with control cells, TRAF6ΔT.OT-I.STAT5bCAtg cells exhibited defects in both proliferation (Fig. 1E) and cell counts (Fig. 1F) relative to co-transferred CD90.1 OT-I.STAT5bCAtg reference cells. Collectively, these findings suggested that an additional, previously unrecognized TRAF6-dependent pathway, non-redundant with STAT5-mediated signaling, might be involved in the induction of LIP.

Figure 1. Naïve TRAF6-deficient CD8 T cells exhibit defective LIP.

CFSE profiles of sorted naïve polyclonal (A) or OT-I (B) control (filled gray) or TRAF6-deficient (black line) CD8 T cells transferred for 7 days into lymphopenic RAG1 knockout mice, and then harvested from recipient spleens, peripheral lymph nodes (PLN), and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). (C) Sorted naïve control (filled) or TRAF6-deficient (open) OT-I CD8 T cells were mixed 1:1 with sorted naïve CD90.1 congenic OT-I CD8 T cells and transferred into lymphopenic recipient mice (3 per group per timepoint). As indicated, mice were sacrificed and cells from spleens and lymph nodes quantified according to the % of control (filled) or TRAF6-deficient (open) as a function of congenic reference cells. (D) CFSE profiles of sorted naïve STAT5bCAtg.OT-I control (filled gray) or TRAF6-deficient (black line) CD8 T cells transferred for 7 days into lymphopenic recipient mice. (E, F) Sorted naïve control (filled) or TRAF6-deficient (open) STAT5bCAtg.OT-I CD8 T cells were mixed 1:1 with sorted naïve CD90.1 congenic STAT5bCAtg.OT-I CD8 T cells, CFSE-labeled, and transferred into lymphopenic recipient mice (3 per group) for 7 days. Ratios of CFSE dilution (calculated as logarithmic ratios) of test cells (WT or ΔT) over CFSE dilution of congenic reference cells from the same mouse (E) and ratios of recovered relative cells numbers (F) for control or TRAF6-deficient (test) cells over congenic (reference) cells from the same mouse are depicted. Error bars represent standard deviation. P-values of <0.05, calculated by Student's t-test, indicate statistical differences between control (WT) and TRAF6-deficient (ΔT) experimental conditions.

IL-18 potentiates LIP in vivo and synergizes with high dose IL-7 to induce proliferation in vitro

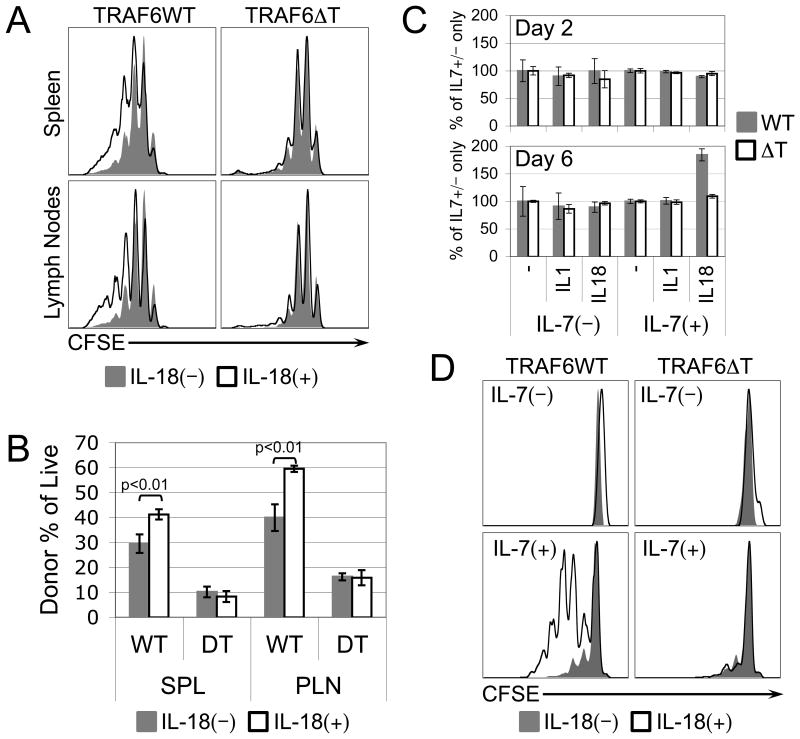

To further elucidate the mechanisms driving LIP and their relationship to TRAF6, we focused on examining, in the context of LIP, factors known to signal through TRAF6. Because the cytokine IL-18 signals through the TRAF6-dependent IL-18R complex (21), has an established capacity to act on naïve CD8 T cells by synergizing with IL-12 to induce production of IFNγ (25, 26), we chose to investigate its effect on LIP first. Therefore, mice harboring lymphopenically-proliferating CD8 T cells were treated daily with recombinant IL-18 to reveal that both the CFSE profiles (Fig. 2A), and the percentages of donor cells as a function of total live cells (Fig. 2B) were enhanced by IL-18, but only when the donor cells expressed TRAF6, raising the possibility that IL-18 acts directly on lymphopenically-proliferating CD8 T cells. IL-7, whose availability increases under lymphopenic conditions, has been identified as a cytokine critical to naïve CD8 T cell LIP, but interestingly, IL-7 alone does not efficiently induce this type of proliferation in vitro (27). However, experiments involving transgenic mice that overexpress IL-7 suggest that in the proper context, high dose IL-7 promotes LIP (28, 29). To determine whether IL-18 can complement IL-7-dependent proliferation, we designed an in vitro model of lymphopenia, whereby control or TRAF6ΔT naïve CD8 T cells were cultured for 2 or 6 days (to account for the possible occurrence, respectively, of faster conventional proliferation or slower LIP-like proliferation) with or without a high dose (1.0ng/mL, which is more than 10 times the minimum dose required to maintain cell viability) of recombinant IL-7, in the presence or absence of 10ng/mL recombinant IL-18. To determine whether any observed effects of IL-18 were specific, we simultaneously tested the related TRAF6-dependent cytokine IL-1β. After normalizing for the increased in vitro cell counts at both days 2 and 6 attributable to the addition of IL-7 alone, we found that neither IL-18 nor IL-1β alone at any time point, nor IL-18 or IL-1β in combination with IL-7 at day 2, had an effect on cell numbers. Surprisingly, however, in the 6-day culture we found that IL-18, but not IL-1β synergized with IL-7 to increase cell numbers in a TRAF6-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Using CFSE-labeled cells, we demonstrated that this increase correlated with the induction of proliferation by naïve control, but not TRAF6ΔT, CD8 T cells treated with IL-7 in the presence of IL-18 (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. TRAF6-dependent LIP of naïve CD8 T cells is enhanced in vivo, and induced in vitro, by IL-18.

(A) CFSE profiles of sorted naïve control or TRAF6-deficient OT-I CD8 T cells recovered after having been adoptively transferred for 7 days into lymphopenic recipient mice that were treated daily with vehicle (filled gray) or recombinant IL-18 (black line). (B) Percentage of live spleen (SPL) or peripheral lymph node (PLN) cells harvested from vehicle- (gray filled) or IL-18-treated (black lines) recipient mice derived from sorted naïve control (WT) or TRAF6-deficient (DT) OT-I CD8 T cells adoptively transferred 7 days earlier. (C) Live relative cell counts from in vitro cell cultures of sorted naïve control (gray filled) or TRAF6-deficient (black lines) OT-I CD8 T cells cultured for 2 days or 6 days +/− 2ng/mL IL-7 in the presence of no additional cytokine (-), or 10ng/mL of either IL-1β or IL-18. (D) CFSE profiles of sorted naïve control or TRAF6-deficient OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 6 days with or without IL-7 in the absence (filled gray) or presence (black line) of 10ng/mL IL-18. Error bars represent calculated standard deviation across three biological replicates. Live relative cell counts were made by collection for equal time at equal flow rate of equal culture volumes on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer.

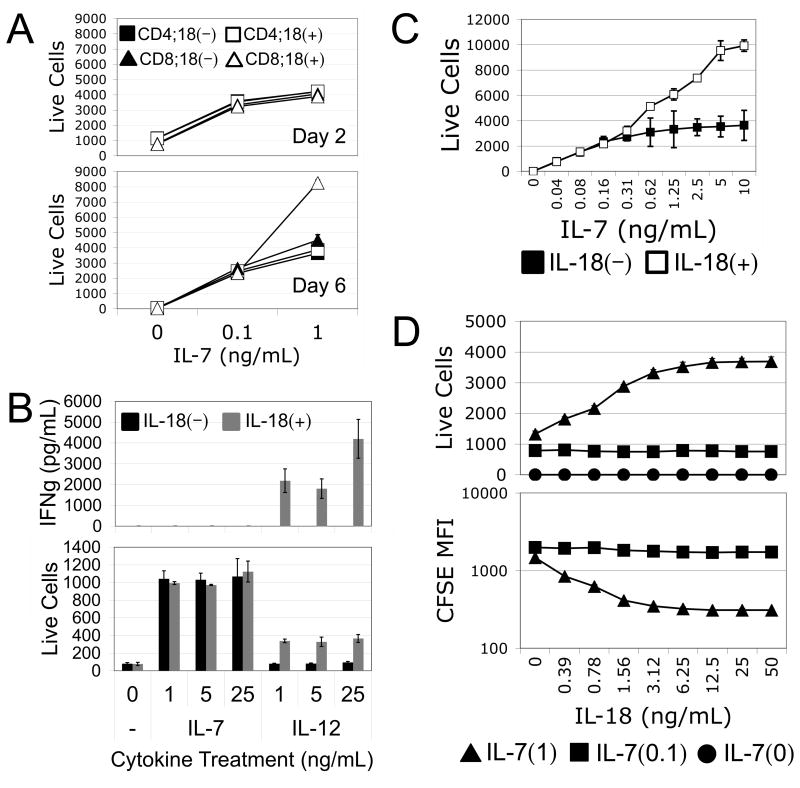

IL-7/IL-18 synergy is specific to CD8 T cells and functionally distinct from IL-12/IL18 synergy

To determine the specificity of IL-7/IL-18 synergy on naïve T cells, we subjected sorted naïve CD4 or CD8 T cells to treatment with different doses of IL-7 in the presence or absence of IL-18 for 2 or 6 days of culture. Interestingly, we found that while both CD4 and CD8 T cell counts increased dose-wise with IL-7, only CD8 T cells exhibited a synergistic increase in response to the addition of IL-18, and only after 6 days of culture in the presence of the higher dose of IL-7 (Fig. 3A). These increases in cell counts correlated with induction of proliferation specific to CD8 T cells treated with high dose IL-7 in combination with IL-18 (Supplemental Fig. 2). Because of the specificity of IL-7/IL-18 synergy for CD8 T cells, we conducted subsequent experiments using OT-I TCR transgenic mice as a source of monoclonal, antigen-inexperienced CD8 T cells. Using these cells, we first demonstrated that unlike the synergistic relationship between IL-18 and IL-12, IL-18 does not induce IFNγ production by naïve CD8 T cells when combined with IL-7 for 60 hours (Fig. 3B). At the same time, titration of IL-7 in the presence or absence of a constant dose of IL-18 further demonstrated that a minimum threshold of IL-7 signaling, higher than that required for maintaining cell viability, is required for IL-7/IL-18 synergy (Fig. 3C). This threshold concentration of IL-7 could not be overcome by increasing the accompanying dose of IL-18 (Fig. 3D), suggesting that IL-7 has a requisite role in sensitizing cells to IL-18 in this context.

Figure 3. IL-7/IL-18 synergy is specific to CD8 T cells and functionally distinct from IL-12/IL18 synergy.

(A) Live relative cell counts from in vitro cell cultures of sorted naïve CD4 (squares) or CD8 (triangles) T cells cultured for 2 or 6 days with either 0, 0.1, or 1.0ng/mL IL-7 in the presence (open) or absence (filled) of 10ng/mL IL-18. (B) ELISA for IFNγ secreted by (top), and live relative cell counts of (bottom), naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured for 60 hours with varying doses of IL-7 or IL-12 in the presence (gray) or absence (black) of 10ng/mL IL-18. (C) Live relative cell counts of naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 6 days with various doses of IL-7 in the absence (filled) or presence (open) of 10ng/mL IL-18. (D) Live relative cell counts (top), and CFSE mean fluorescence intensity (bottom), of naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 6 days with various doses of IL-18 combined with 0 (circles), 0.1ng/mL (squares), or 1.0ng/mL (triangles) of IL-7. Error bars represent calculated standard deviation across three biological replicates. Live relative cell counts were made by collection for equal time at equal flow rate of equal culture volumes on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer.

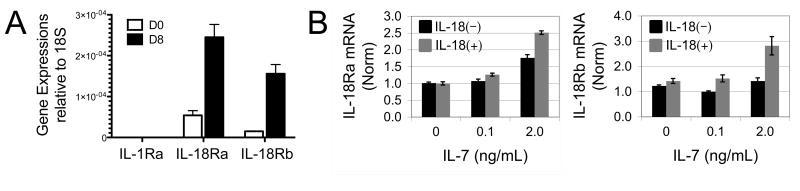

CD8 T cell LIP and IL-7/IL-18 in vitro synergy are associated with upregulation of IL-18R expression

IL-12 has been shown to synergize with IL-18 by upregulating IL-18R gene expression, thereby sensitizing them to IL-18 (26). To determine whether lymphopenic conditions induce IL-18R expression on naïve CD8 T cells, we adoptively transferred sorted naïve OT-I CD8 T cells into irradiated CD45.1 congenic recipient mice, and harvested donor cells by sorting 8 days later. cDNA was prepared and gene expression compared by real-time PCR to expression levels from untransferred naïve cells. It was found that both IL-18 receptor alpha (IL-18Ra) and beta (IL-18Rb) chain genes were induced by lymphopenic conditions, while the related gene, IL-1 receptor alpha, was not induced (Fig. 4A). To gain insight into any specific relationship between IL-7, IL-18, and IL-18R expression in vitro, we performed real-time PCR on cDNA prepared from OT-I CD8 T cells treated for 4 hours in the presence or absence of IL-18 with varying concentrations of IL-7. We found that high dose IL-7 synergized with IL-18 to enhance expression of the IL-18 receptor alpha and beta chains (Fig. 4B), possibly explaining the increased sensitivity of these cells to IL-18.

Figure 4. CD8 T cell LIP and IL-7/IL-18 in vitro synergy are associated with upregulation of IL-18R expression.

(A) Real-Time PCR for IL-1Rα, IL-18Rα, and IL-18Rβ message expressed by sorted naïve OT-I CD8 T cells (D0) or OT-I CD8 T cells recovered by sorting eight days after being transferred to congenic lymphopenic recipient mice (D8). Error represent standard deviations calculated from cell samples harvested from three independent recipient mice (n=3). (B) Real-Time PCR for IL-18Rα (left panel) and IL-18Rβ (right panel) message expressed by naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured for 4 hours with no, low dose (0.1ng/mL), or high dose (2.0ng/mL) IL-7 in the presence (gray) or absence (black) of 10ng/mL IL-18. Error bars represent calculated standard deviation across three biological replicates.

IL-18- and IL-7-dependent in vitro LIP requires PI3K activation

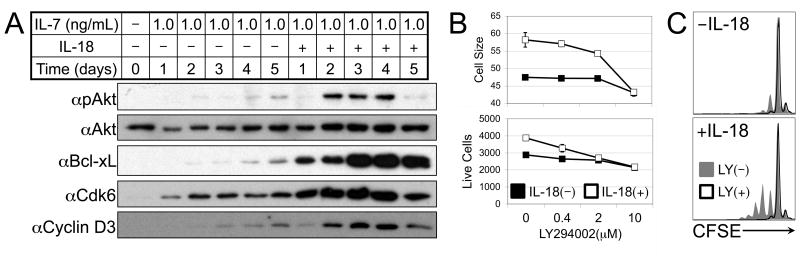

IL-7 induces gene expression primarily through activation of the JAK-STAT pathway and the transcription factor STAT5. While IL-7 has been shown to synergize with IL-6 or IL-21 to augment STAT5 activation (12, 30), we found that, unlike IL-6, IL-18 had no effect on IL-7-dependent phosphorylation of STAT5 (Supplemental Fig. 3). IL-7 has also been shown to activate the PI3 kinase-Akt pathway, though this activation pathway is delayed compared to STAT5 (31). It has also been demonstrated that recent thymic emigrants require PI3 kinase in order to proliferate in response to IL-7 (32). Interestingly, Akt activation has been shown to depend on functional TRAF6 downstream of various receptor-signaling complexes (19, 33). We demonstrated that treatment of naïve CD8 T cells with high dose IL-7 in combination with IL-18 during a 5-day culture results in strikingly enhanced activation of Akt, which correlated with increased expression of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-xL, and cell cycle-related factors Cdk6 and Cyclin D3 (Fig. 5A). Further, pre-treatment of IL-7/IL-18-stimulated cultures with the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 revealed that IL-18-dependent increases in cell size and cell numbers are particularly sensitive to PI3 kinase inhibition, while the IL-7-mediated cell survival effect is less sensitive (Fig. 5B), suggesting that enhanced PI3 kinase-Akt activation may be the key molecular mechanism of IL-7/IL-18 synergy. Pre-treatment of CFSE-labeled IL-7/IL-18-stimulated CD8 T cell cultures with LY294002 further demonstrated that PI3 kinase inhibition prevents IL-7/IL-18-dependent proliferation (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. PI3 Kinase signaling is required for IL-18-dependent in vitro LIP.

(A) Western blot analysis of naïve OT-I CD8 T cells with 1ng/mL IL-7 in the presence or absence of 10ng/mL IL-18 for the number of days indicated. (B) Relative cell size (top) and live relative cell counts (bottom) from in vitro cell cultures of naïve OT-I CD8 T cells treated for 6 days with 1.0ng/mL IL-7 in the presence (open) or absence (filled) of 10ng/mL IL-18, and the indicated concentration of LY294002. (C) CFSE profiles of sorted naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 6 days with or without 10ng/mL IL-18 in the absence (filled gray) or presence (black line) of 10μM LY294002. Error bars represent calculated standard deviation across three biological replicates. Live relative cell counts were made by collection for equal time at equal flow rate of equal culture volumes on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer.

Effect of IL-18 on in vitro LIP is linked to TCR-mediated signals

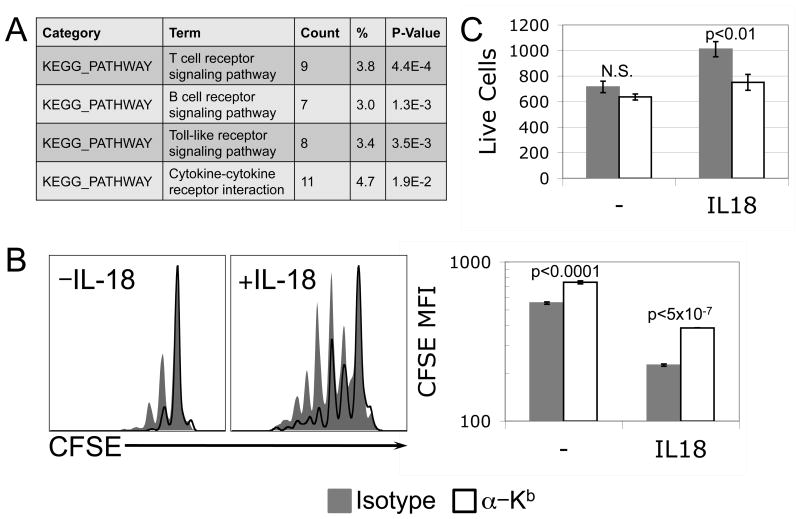

To further elucidate the mechanism of synergy between IL-7 and IL-18 in the context of lymphopenia-induced-like proliferation of naïve CD8 T cells in vitro, we performed microarray analysis of cells treated for 24 hours with low or high dose IL-7 in the presence or absence of IL-18. We found by KEGG pathway analysis that genes whose expression levels are affected by high dose IL-7 specifically in the presence of IL-18 are most closely linked to the TCR pathway (Fig. 6A). In addition to IL-7, tonic TCR signaling is required for both survival and proliferation of CD8 T cells under lymphopenic conditions (12, 34). We cultured naïve CD8 T cells in the presence of IL-7 and IL-18 in the presence of blocking αMHC-I (Y3) or isotype control antibodies, and found that interfering with tonic interaction between MHC-I and TCR complexes within a population of purified CD8 T cells resulted in decreased proliferation (Fig. 6B). While the effect of MHC-I blocking antibody on CFSE dye dilution was significant in the presence or absence of IL-18, its effect on total cell numbers was specific to cultures treated in the presence of IL-18 (Fig. 6C). These data further suggested a role for IL-18 in sensitizing naïve CD8 T cells to the tonic signals transmitted through TCR during LIP.

Figure 6. Synergy between IL-7 and IL-18 in naïve CD8 T cells affects TCR-associated signaling.

(A) Naïve OT-I CD8 T cells were stimulated for 24 hours +/- 10ng/mL IL-18 in the presence of low (0.1ng/mL) or high (1.0ng/mL) dose IL-7, and RNA message subjected to microarray analysis. Differential gene expression across experimental groups (n=5) was determined by ANOVA, and the resulting gene lists were used for KEGG pathway analysis. The relevant pathways are ranked by p-value for functional assignment of genes that changed in the presence of IL-18 when IL-7 dose was increased from 0.1ng/mL to 1.0ng/mL. (B) Representative CFSE profiles (left panel) and mean CFSE fluorescence from triplicate wells (right panel) of naive OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 6 days with 1.0ng/mL IL-7 +/- 10ng/mL IL-18 in the presence of isotype control (gray, filled) or anti-MHC-I (Y3) neutralizing (black, unfilled) antibody. (C) Live relative cell counts from triplicate wells (right panel) of naive OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 6 days with 1.0ng/mL IL-7 +/- 10ng/mL IL-18 in the presence of isotype control (gray, filled) or anti-MHC-I (Y3) neutralizing (black, unfilled) antibody. Error bars represent standard deviation. P-values of <0.05, calculated by Student's t-test, indicate statistical differences between isotype control and anti-MHC neutralizing antibody conditions. N.S. (Not Significant). Live relative cell counts were made by collection for equal time at equal flow rate of equal culture volumes on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer.

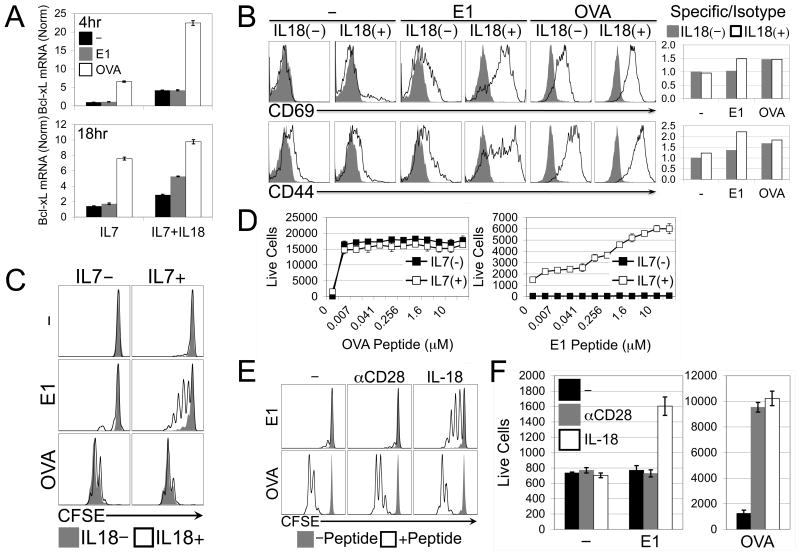

IL-18 synergizes with IL-7 to sensitize naïve CD8 T cells to antagonist peptide

To examine the role of IL-7/IL-18 synergy in sensitizing naïve CD8 T cells to tonic (i.e., self peptide) TCR signals, we utilized the OT-I TCR transgenic system, for which an array of peptides have been characterized with respect to affinity to TCR and capacity to mediate T cell selection (35). While the chicken ovalbumin peptide 257-264 acts as a cognate antigen for OT-I T cells, the E1 mutant version of this peptide is antagonistic, and has been shown to be capable of mediating both positive selection and LIP in vivo (13, 14). Because CD8 T cells express MHC-I, they are capable of being activated by the provision of free peptide (36). We assessed upregulation of Bcl-xL message by IL-7/IL-18-treated naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in the presence or absence of either OVA or E1 mutant peptide, and determined that while both peptides had a positive effect, OVA peptide acted more quickly and did not require the presence of IL-18, while E1 peptide acted more slowly, and only when IL-18 was present (Fig. 7A). Likewise, IL-18 significantly increased surface expression of early (preceding induction of proliferation) activation markers CD69 and CD44 on cells cultured with high dose IL-7 and E1 peptide by 36 hours (Fig. 7B). These findings suggested that IL-7, IL-18, and E1 peptide might synergistically recapitulate slow lymphopenia-induced-like proliferation in vitro. Indeed, we found that during a relatively short (60-hour) culture OVA peptide induced the same degree of CFSE dye dilution independently of IL-18 co-treatment, while cells treated with E1 peptide and IL-7 were induced to proliferate, but only in the presence of IL-18 (Fig. 7C). Live cell counts in cultures stimulated with various concentrations of OVA or E1 peptides revealed, not surprisingly, that OT-I CD8 T cells accumulated at a much lower concentration of OVA peptide than of E1 mutant peptide when co-treated with IL-7 and IL-18 (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, when treated with IL-18, OVA-stimulated cells responded equally well in the presence or absence of IL-7, while cells treated with IL-18 and E1 peptide (regardless of concentration) failed to accumulate, or even survive, in the absence of IL-7. This finding raised the possibility that IL-7 and IL-18 together provide a “costimulatory” signal distinct from conventional CD28 ligation, in a manner specifically suited to sensitizing naïve CD8 T cells to low affinity or antagonist peptide. To test this idea, we stimulated naïve OT-I CD8 T cells with IL-7 and either OVA or E1 peptide in the presence or absence of IL-18 or αCD28. Predictably, cells stimulated with OVA peptide proliferated and accumulated equally well whether costimulated with IL-18 or αCD28. However, OT-I cells stimulated with E1 peptide were induced to proliferate (Fig. 7E) and accumulate (Fig. 7F) (though at lower levels than when stimulated with OVA) when costimulated with IL-18, but not with αCD28, thereby demonstrating the unique role of IL-7/IL-18 synergy in sensitizing naïve CD8 T cells to low affinity or antagonistic TCR-peptide interactions.

Figure 7. IL-18 synergizes with IL-7 to positively sensitize naïve CD8 T cells to an antagonistic model peptide.

(A) Real-Time PCR for Bcl-xL message expressed by naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured for 4 hours with 1.0ng/mL IL-7 alone or 1.0ng/mL IL-7 + 10ng/mL IL-18 in the presence of either no peptide (black), 1μM OVA(E1) mutant peptide (gray), or 1μM OVA(257-264) peptide (open). (B) Flow cytometry histograms (left) depicting isotype (gray, filled) and specific staining (black, open) and accompanying ratiometric analysis (right) of CD69 (top) and CD44 (bottom) expression on naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured for 36 hours with 1.0ng/mL IL-7 alone or 1.0ng/mL IL-7 + 10ng/mL IL-18 in the presence of either no peptide, 1μM OVA(E1) mutant peptide, or 1μM OVA(257-264) peptide. (C) CFSE profiles of naive OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 60 hours +/- IL-7 in the presence (black, open) or absence (gray, filled) of IL-18 with either no peptide, 1μM OVA(257-264) peptide, or 1μM OVA(E1) mutant peptide. (D) Live relative cell counts of naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 60 hours with 10ng/mL IL-18 alone (filled) or 10ng/mL IL-18 + 1.0ng/mL IL-7 (open) in combination with various concentrations of either OVA(257-264) peptide (top) or OVA(E1) mutant peptide (bottom). (E) CFSE profiles and (F) Live relative cell counts of naïve OT-I CD8 T cells cultured in vitro for 60 hours with 1.0ng/mL IL-7 plus either no peptide, low dose (0.001nM) OVA(257-264) peptide, or high dose (1000nM) OVA(257-264) or OVA(E1) mutant peptide, in combination with either no costimulation, 1μg/mL αCD28, or 10ng/mL IL-18. Error bars represent calculated standard deviation across three biological replicates. Live relative cell counts were made by collection for equal time at equal flow rate of equal culture volumes on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer.

Discussion

In this study we have identified a novel signaling mechanism in naïve CD8 T cells that is mediated by a TRAF6-dependent pathway and required for LIP. We have further shown that this pathway may be directly activated in CD8 T cells by the inflammatory cytokine IL-18 when it acts in synergy with IL-7 at a “lymphopenia-like” concentration. IL-7/IL-18 synergy apparently functions to both enhance expression of the IL-18 receptor complex, and to sensitize naïve CD8 T cells to non-cognate peptides similar to self-peptides required both for positive selection and LIP.

Previous microarray analyses of CD8 T cells undergoing LIP reveal a gene expression program likened to an attenuated cognate antigen-mediated TCR stimulation (though lacking effector gene expression) (37). It has been well established that TCR-mediated activation via cognate peptide antigen requires amplifying costimulatory signals (38), and that this mechanism is important as a check on potentially harmful activation that could lead to autoimmunity (38, 39). However, it has been shown that conventional costimulatory pathways (e.g., CD28) are not required for LIP (40-42), and that blockade of conventional costimulation does not prevent pathology related to LIP following organ transplant (8, 43). Based on our current findings, we speculate that TRAF6-dependent activation of Akt in naïve CD8 T cells encountering lymphopenic (or similar) conditions may represent a novel and unique “costimulatory” signal. As demonstrated, IL-18 synergizes with IL-7 in a manner analogous to CD28 to provide a complementary signal necessary for activation of naïve CD8 T cells encountering non-cognate antigen or self-peptide. We have provided evidence that these factors together enhance activation of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway, and expression of pro-survival and cell cycle-related proteins associated with TCR-mediated activation (Fig. 5). Importantly, though, we assert that costimulation provided through IL-7 and IL-18 synergy is mechanistically unique from that provided by CD28, as we found that CD28 costimulation was able to enhance proliferation of naïve CD8 T cells stimulated with cognate antigen, but not with the non-cognate “self” peptide (Fig. 7). Our data suggest that unlike TCR and CD28, which can signal on naïve cells at the same time, IL-7 and IL-18 signaling occurs sequentially, as IL-7 appears necessary to sensitize cells to IL-18 via IL-18R upregulation (Fig. 4). This is likely one reason (along with suboptimal TCR signaling) that this form of proliferation occurs more slowly than proliferation by cognate antigen and conventional costimulation. It is possible, though, that like conventional costimulation, IL-7/IL-18 synergy may also serve to prevent unnecessary and potentially dangerous immune responses from developing. For instance, it has been shown that excessive IL-7R signaling can lead to systemic autoimmunity, and that lymphopenia-related signals more generally may be implicated in loss of T cell tolerance (12, 44-47). It is also important to point out that while in vivo provision of IL-18 results in moderately enhanced LIP profiles (Fig. 2A), and CD8 T cells upregulate IL-18 receptor genes under lymphopenic conditions (Fig. 4A), our preliminary work using IL-18-deficient recipient mice or IL-18R-deficient donor T cells suggests that the requirement for IL-18 per se during LIP is either minor, or highly context-dependent (data not shown.) However, our work demonstrates that the TRAF6-mediated pathway is required for both in vivo LIP and in vitro IL-7/IL-18-mediated synergy. The most obvious explanation for our observations of the modest requirement for IL-18 in vivo is that there may be numerous other receptors expressed by naïve CD8 T cells that may be capable of activating TRAF6 signaling. While, in this context, we have found that IL-18 possesses unique activity among the IL-1/IL-18/IL-33 family members (Fig. 2C and data not shown), TRAF6 may also be activated through other TLR or TNFR family members, as well as through the TGFβ receptor complex. Interestingly, two recent reports have shown enhanced CD8 T cell LIP, and in one case, induction of autoimmunity, in mouse models of defective T cell-specific TGFβ signaling (48, 49). These results are particularly intriguing because we have previously demonstrated negative modulation of TGFβ-mediated Smad activation by TRAF6 in T cells (50). Future work might therefore benefit from incorporating the role of TGFβR signaling into studies of TRAF6-regulated naïve CD8 T cell LIP (and even homeostasis more broadly.)

Finally, IL-18 is a factor currently being studied in clinical applications, and may be a promising immunostimulatory anti-cancer agent (51, 52). Therefore, while IL-18 may not itself represent the TRAF6-related factor required to drive LIP of naïve CD8 T cells in vivo, it is important to recognize that IL-18 may still have potential as a therapeutic tool in cases where enhanced low-level activation of naïve (or semi-activated) T cells is desirable. For instance, techniques have been demonstrated for enhancing anti-tumor responses by mimicking homeostatic proliferation conditions in vitro, and by eliminating sources of depletion of homeostatic cytokines in vivo (10, 53, 54). While evidence suggests that conventional CD28 costimulation is required to drive lymphopenia-added anti-tumor CTL differentiation and effector function in the presence of strong TCR stimulation (55), we present evidence here for IL-18-mediated enhancement of lymphopenia-triggered proliferation (but not necessarily effector differentiation) in response to “weak” TCR stimulation. We suggest that IL-18 and CD28 have distinct costimulatory functionalities, and that it may be possible to improve or enhance immunotherapeutic protocols (or others) with additional IL-18 treatment, and that, regardless, IL-18 may continue to serve as a useful tool for elucidating the physiologic underpinnings of proliferative mechanisms of naïve T cell homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Elizabeth Molnar and Okju Yi for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM), MEST, Korea (No. K13050 to Y.C.), and by the National Institutes of Health (AI064909 to Y.C.)

References

- 1.Wong P, Pamer EG. CD8 T cell responses to infectious pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:29–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang N, Bevan MJ. CD8(+) T cells: foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity. 2011;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surh CD, Sprent J. Regulation of mature T cell homeostasis. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takada K, Jameson SC. Naive T cell homeostasis: from awareness of space to a sense of place. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:823–832. doi: 10.1038/nri2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchholz VR, Neuenhahn M, Busch DH. CD8+ T cell differentiation in the aging immune system: until the last clone standing. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:549–554. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauce D, Larsen M, Fastenackels S, Roux A, Gorochov G, Katlama C, Sidi D, Sibony-Prat J, Appay V. Lymphopenia-driven homeostatic regulation of naive T cells in elderly and thymectomized young adults. J Immunol. 2012;189:5541–5548. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monti P, Piemonti L. Homeostatic T cell proliferation after islet transplantation. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2013;2013:217934. doi: 10.1155/2013/217934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tchao NK, Turka LA. Lymphodepletion and homeostatic proliferation: implications for transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2012;12:1079–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voehringer D, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Homeostasis and effector function of lymphopenia-induced “memory-like” T cells in constitutively T cell-depleted mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:4742–4753. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser AD, Gadiot J, Guislain A, Blank CU. Mimicking homeostatic proliferation in vitro generates T cells with high anti-tumor function in non-lymphopenic hosts. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:503–515. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1350-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dummer W, Niethammer AG, Baccala R, Lawson BR, Wagner N, Reisfeld RA, Theofilopoulos AN. T cell homeostatic proliferation elicits effective antitumor autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:185–192. doi: 10.1172/JCI15175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanathan S, Gagnon J, Dubois S, Forand-Boulerice M, Richter MV, Ilangumaran S. Cytokine synergy in antigen-independent activation and priming of naive CD8+ T lymphocytes. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:219–239. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i3.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst B, Lee DS, Chang JM, Sprent J, Surh CD. The peptide ligands mediating positive selection in the thymus control T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery. Immunity. 1999;11:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Low-affinity ligands for the TCR drive proliferation of mature CD8+ T cells in lymphopenic hosts. Immunity. 1999;11:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morre M, Beq S. Interleukin-7 and immune reconstitution in cancer patients: a new paradigm for dramatically increasing overall survival. Targeted oncology. 2012;7:55–68. doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perales MA, Goldberg JD, Yuan J, Koehne G, Lechner L, Papadopoulos EB, Young JW, Jakubowski AA, Zaidi B, Gallardo H, Liu C, Rasalan T, Wolchok JD, Croughs T, Morre M, Devlin SM, van den Brink MR. Recombinant human interleukin-7 (CYT107) promotes T-cell recovery after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;120:4882–4891. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King CG, Kobayashi T, Cejas PJ, Kim T, Yoon K, Kim GK, Chiffoleau E, Hickman SP, Walsh PT, Turka LA, Choi Y. TRAF6 is a T cell-intrinsic negative regulator required for the maintenance of immune homeostasis. Nat Med. 2006;12:1088–1092. doi: 10.1038/nm1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM, Shen H, Wang LS, Jones RG, Choi Y. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi Y. Role of TRAF6 in the immune system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;560:77–82. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24180-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell. 2000;103:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kojima H, Takeuchi M, Ohta T, Nishida Y, Arai N, Ikeda M, Ikegami H, Kurimoto M. Interleukin-18 activates the IRAK-TRAF6 pathway in mouse EL-4 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:183–186. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tajima M, Wakita D, Noguchi D, Chamoto K, Yue Z, Fugo K, Ishigame H, Iwakura Y, Kitamura H, Nishimura T. IL-6-dependent spontaneous proliferation is required for the induction of colitogenic IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1019–1027. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burchill MA, Goetz CA, Prlic M, O'Neil JJ, Harmon IR, Bensinger SJ, Turka LA, Brennan P, Jameson SC, Farrar MA. Distinct effects of STAT5 activation on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell homeostasis: development of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells versus CD8+ memory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:5853–5864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:423–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, Ohkusu K, Kashiwamura S, Okamura H, Akira S, Nakanishi K. IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1998;161:3400–3407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan JT, Dudl E, LeRoy E, Murray R, Sprent J, Weinberg KI, Surh CD. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosco N, Agenes F, Ceredig R. Effects of increasing IL-7 availability on lymphocytes during and after lymphopenia-induced proliferation. J Immunol. 2005;175:162–170. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kieper WC, Tan JT, Bondi-Boyd B, Gapin L, Sprent J, Ceredig R, Surh CD. Overexpression of interleukin (IL)-7 leads to IL-15-independent generation of memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1533–1539. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagnon J, Ramanathan S, Leblanc C, Cloutier A, McDonald PP, Ilangumaran S. IL-6, in synergy with IL-7 or IL-15, stimulates TCR-independent proliferation and functional differentiation of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:7958–7968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wofford JA, Wieman HL, Jacobs SR, Zhao Y, Rathmell JC. IL-7 promotes Glut1 trafficking and glucose uptake via STAT5-mediated activation of Akt to support T-cell survival. Blood. 2008;111:2101–2111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swainson L, Kinet S, Mongellaz C, Sourisseau M, Henriques T, Taylor N. IL-7-induced proliferation of recent thymic emigrants requires activation of the PI3K pathway. Blood. 2007;109:1034–1042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong BR, Besser D, Kim N, Arron JR, Vologodskaia M, Hanafusa H, Choi Y. TRANCE, a TNF family member, activates Akt/PKB through a signaling complex involving TRAF6 and c-Src. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kieper WC, Burghardt JT, Surh CD. A role for TCR affinity in regulating naive T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2004;172:40–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schott E, Bertho N, Ge Q, Maurice MM, Ploegh HL. Class I negative CD8 T cells reveal the confounding role of peptide-transfer onto CD8 T cells stimulated with soluble H2-Kb molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13735–13740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212515399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldrath AW, Luckey CJ, Park R, Benoist C, Mathis D. The molecular program induced in T cells undergoing homeostatic proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16885–16890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharpe AH. Mechanisms of costimulation. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tivol EA, Schweitzer AN, Sharpe AH. Costimulation and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho BK, Rao VP, Ge Q, Eisen HN, Chen J. Homeostasis-stimulated proliferation drives naive T cells to differentiate directly into memory T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:549–556. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prlic M, Blazar BR, Khoruts A, Zell T, Jameson SC. Homeostatic expansion occurs independently of costimulatory signals. J Immunol. 2001;167:5664–5668. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suresh M, Whitmire JK, Harrington LE, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Altman JD, Ahmed R. Role of CD28-B7 interactions in generation and maintenance of CD8 T cell memory. J Immunol. 2001;167:5565–5573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Z, Bensinger SJ, Zhang J, Chen C, Yuan X, Huang X, Markmann JF, Kassaee A, Rosengard BR, Hancock WW, Sayegh MH, Turka LA. Homeostatic proliferation is a barrier to transplantation tolerance. Nat Med. 2004;10:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calzascia T, Pellegrini M, Lin A, Garza KM, Elford AR, Shahinian A, Ohashi PS, Mak TW. CD4 T cells, lymphopenia, and IL-7 in a multistep pathway to autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez-Quintial R, Lawson BR, Scatizzi JC, Craft J, Kono DH, Baccala R, Theofilopoulos AN. Systemic autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation are associated with excess IL-7 and inhibited by IL-7Ralpha blockade. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King C, Ilic A, Koelsch K, Sarvetnick N. Homeostatic expansion of T cells during immune insufficiency generates autoimmunity. Cell. 2004;117:265–277. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le Saout C, Mennechet S, Taylor N, Hernandez J. Memory-like CD8+ and CD4+ T cells cooperate to break peripheral tolerance under lymphopenic conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19414–19419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807743105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson LD, Jameson SC. TGF-beta sensitivity restrains CD8+ T cell homeostatic proliferation by enforcing sensitivity to IL-7 and IL-15. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang N, Bevan MJ. TGF-beta signaling to T cells inhibits autoimmunity during lymphopenia-driven proliferation. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:667–673. doi: 10.1038/ni.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cejas PJ, Walsh MC, Pearce EL, Han D, Harms GM, Artis D, Turka LA, Choi Y. TRAF6 inhibits Th17 differentiation and TGF-beta-mediated suppression of IL-2. Blood. 2010;115:4750–4757. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srivastava S, Salim N, Robertson MJ. Interleukin-18: biology and role in the immunotherapy of cancer. Current medicinal chemistry. 2010;17:3353–3357. doi: 10.2174/092986710793176348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsutsui H, Nakanishi K. Immunotherapeutic applications of IL-18. Immunotherapy. 2012;4:1883–1894. doi: 10.2217/imt.12.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, Antony PA, Palmer DC, Spiess PJ, Hwang LN, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Heimann DM, Surh CD, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klebanoff CA, Khong HT, Antony PA, Palmer DC, Restifo NP. Sinks, suppressors and antigen presenters: how lymphodepletion enhances T cell-mediated tumor immunotherapy. Trends in immunology. 2005;26:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki T, Ogawa S, Tanabe K, Tahara H, Abe R, Kishimoto H. Induction of antitumor immune response by homeostatic proliferation and CD28 signaling. J Immunol. 2008;180:4596–4605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.