Abstract

We model blood in a microvessel as an inhomogeneous non-Newtonian fluid, whose viscosity varies with hematocrit and shear rate in accordance with the Quemada rheological relation. The flow is assumed to consist of two distinct, immiscible and homogeneous fluid layers: an inner region densely packed with red blood cells, and an outer cell-free layer whose thickness depends on discharge hematocrit. We demonstrate that the proposed model provides a realistic description of velocity profiles, tube hematocrit, core hematocrit and apparent viscosities over a wide range of vessel radii and discharge hematocrits. Our analysis reveals the importance of incorporating this complex blood rheology into estimates of wall shear stress in micro-vessels. The latter is accomplished by specifying a correction factor, which accounts for the deviation of blood flow from the Poiseuille law.

Keywords: blood rheology, hematocrit, shear thinning, plasma layer, apparent viscosity, shear stress

1. Introduction

Velocity profiles of blood flowing in glass tubes [18,10,1] and in vivo [3,15,36] are observed to be blunted, rather than the parabolic velocity profiles characteristic of Newtonian fluids. Both the CFL [14,18] and non-Newtonian behavior of blood [19,22,26,34] in the microcirculation have been used to explain the experimentally observed bluntness of blood velocity profiles in narrow glass tubes [18,10,1] and in-vivo microvessels [18,3,15,36].

Blunting of the velocity profiles observed in microvessels affects the overall rate of energy dissipation by the flow and the distribution of shear rates across the vessel cross-section. Of particular physiological significance is the shear stress developed at the microvessel vessel wall that modulates the production of shear stress dependent materials by the endothelium, a significant effect due to the large endothelial surface of the microcirculation [23,16,2]. The bluntness of blood velocity profiles has significant implications on indirect measurements of wall shear stress (WSS), which are typically inferred from direct measurements of centerline velocity and vessel radius by invoking the Poiseuille law [28,5,13]. The mismatch between the experimentally observed blunt velocity profiles and their parabolic counterparts predicted by the Poiseuille law introduces interpretive errors in WSS measurement [13,28].

A typical CFL thickness is on the order of 1 mm [14,24,27,35]. It is relatively insensitive to vessel radius, but decreases significantly with hematocrit [9,29,35]. While plasma in the CFL can be treated as a Newtonian fluid, the RBC-rich core displays non-Newtonian shear-thinning properties. In this study, we assume a general functional dependence of CFL thickness on hematocrit and then calculate velocity profiles of blood flow through a tube, comprising two discrete fluid layers: the non-Newtonian RBC core and the CFL (which is assumed Newtonian).

Experimental work on blood rheology has demonstrated the dependence of blood viscosity on shear rate and hematocrit, showing that the relationship between shear stress and shear rate for blood is non-linear (and non-Newtonian), with the shear thinning properties [7,19,22] that are enhanced by increasing hematocrit. This shear-thinning rheology of blood in the RBC core was mathematically represented in our flow model via the Quemada rheological model. The Quemada model is a three-parameter constitutive rheological model that accurately describes shear thinning blood rheology over a wide range of shear rates and hematocrit [19,22,26]. Due to this robustness, the Quemada model is superior to other blood rheological models of comparable complexity [19] and was hence utilized in our flow model.

Previous mathematical models of blood flow in microvessels have typically treated both fluid layers (the CFL and RBC core) as Newtonian fluids, with the viscosity of the RBC core being larger than the viscosity of the CFL [21,31,33]. Our model builds upon these previous studies; we compare results for our non-Newtonian model with the 2-layer Newtonian model and demonstrate that significant differences between the two models exist. We demonstrate that our model is a significant improvement over previous Newtonian models, more accurately predicting CFL thickness, velocity profiles and apparent viscosities.

We then leverage our flow model to develop a general method for correcting experimental estimation of WSS. Typically, WSS in a blood vessel is estimated in experimental studies by measuring the centerline velocity and the vessel radius; with these values the WSS is then calculated using the Poiseuille law [5,13,28]. The problem with this approach is that blood flow in microvessels does not follow the Poiseuille law (due to the inhomogeneous and non-Newtonian behaviors discussed above). This introduces errors in the measurement of WSS [13,28].

These errors may be avoided by direct measurement of velocity profiles, using methods such as in [18]. This allows precise estimation of shear rate at the vessel wall; for a known plasma viscosity, WSS can then be calculated once wall shear rate is known. The difficulty with this alternative is that direct measurement of velocity profiles is a difficult and complicated task; repeatedly measuring velocity profiles every time WSS estimates are needed is relatively impractical (and expensive) with current technology and experimental techniques [13].

In this study, we compute the magnitude of these WSS estimation errors arising from the use of the Poiseuille law and demonstrate that these errors are significant. We propose two methods to eliminate these errors: an iterative numerical algorithm which leverages our flow model, and the use of a simple correction factor that can be incorporated into the Poiseuille law. Given a rheological model of the RBC-rich core, both approaches allow one to infer WSS from measurements of vessel radius, centerline velocity and discharge hematocrit.

Mathematical model of blood flow in arterioles

Symbols used:

R, r Vessel radius and radial coordinate

μp Plasma viscosity

γc, k0 and k∞ Parameters in the Quemada rheological model

μ, μeff, μrel Medium, Effective medium and Relative medium viscosity

τ, τw Shear stress and Wall shear stress (WSS)

δ CFL thickness

Q Flow rate of blood in blood vessel

γ Shear rate

H, Hc, Hd, Ht Localized, core, discharge and tube hematocrit

J Pressure gradient

vz Axial velocity

vmax Centerline (maximum) velocity

φ WSS correction factor

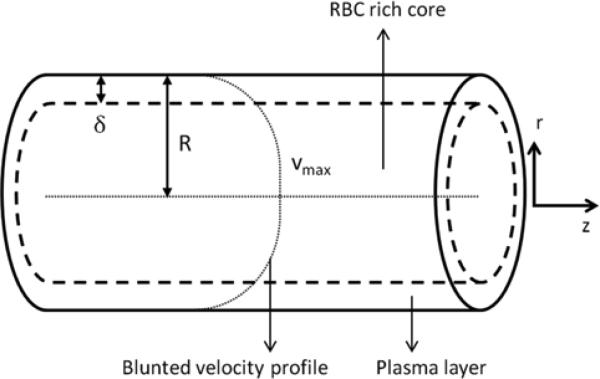

We consider steady-state blood flow in an arteriole of fixed radius R. The flow is driven by an externally imposed pressure gradient J, with no-slip boundary conditions prescribed at the (non-deformable) vessel walls. Blood is treated as a two-layer inhomogeneous fluid: an RBC-rich core region near the vessel centerline [31,33] occupies the cylinder of radius (R - δ) and a CFL of thickness δ occupies the rest of the vessel (Figure 1). Plasma in the CFL is modeled as a Newtonian fluid with a constant viscosity μp, independent of both hematocrit and shear rate γ. Hematocrit distribution in the RBC-rich core is assumed to be uniform. The Quemada rheological model [19,22,26] is used to describe the non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior of the RBC-rich core.

1.

Cell-free layer (CFL) and red-blood-cell (RBC) rich core in an arteriole. The CFL is occupied by plasma, a Newtonian fluid whose viscosity is lower than that of the non-Newtonian fluid comprising the RBC-rich core.

The Quemada constitutive law postulates a nonlinear relationship between shear stress τ and shear rate γ in the RBC-rich core,

| (1) |

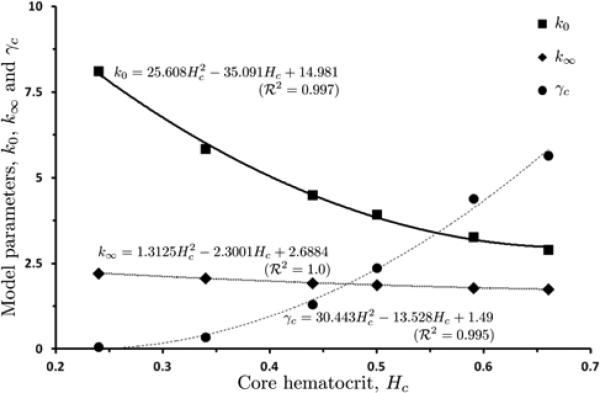

The model parameters γc, k0 and k∞ vary with core hematocrit Hc (the value of hematocrit H in the RBC-rich core) [7,22]. We fit the parameter data reported in [22] with second degree polynomials in Hc. Figure 2 exhibits both the data and the fitted curves (with the goodness-of-the-fit R 2 exceeding 0.99 for all three curves). The Quemada model (1) reduces to a linear (Newtonian) relationship between τ and γ when either Hc is small or γ is large.

2.

The data reported in [22] show the dependence of the Quemada model parameters γc, k0 and k∞ on hematocrit in the RBC core, Hc. These data are fitted with second-degree polynomials in Hc.

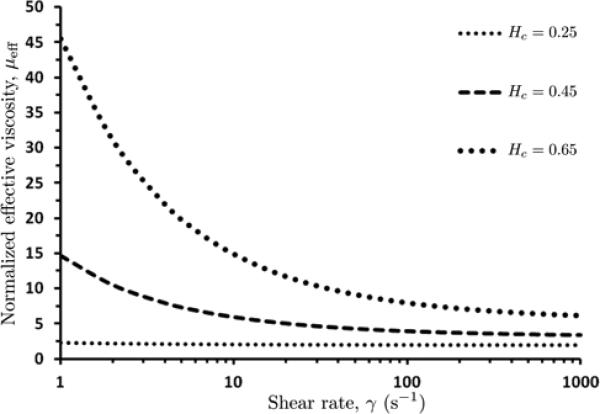

The normalized (dimensionless) effective viscosity μeff of blood is defined from Eq (1) as:

| (2) |

According to this expression, the normalized effective viscosity μeff of blood in the core region decreases with increases in shear rate γ and increases with increases with core hematocrit Hc (Figure 3). At large values of γ (above 200 s-1), the viscosity is approximately constant and the fluid is essentially Newtonian. Regardless of the fluid properties, the Cauchy equations of motion for steady (or pseudo-steady for low Womersley numbers), axisymmetric laminar flow have the form:

| (3) |

Integrating this equation across the RBC-rich core (from 0 to R - δ ) and across the CFL (from R - δ to R) yields respectively:

| (4) |

and

| (5) |

where C1 and C2 are constants of integration. Since the shear stress τ(r) must remain finite throughout the blood vessel, including its centerline r = 0, we set C1 = 0. The continuity of the shear stress at the interface between the two fluids (at r = R - δ) requires C2 = 0. Therefore, the shear stress τ(r) is given by:

| (6) |

throughout the blood vessel (0 ≤ r ≤ R).

3.

Variation of normalized (dimensionless) effective viscosity μeff of blood in the core region, with shear rate γ and core hematocrit Hc.

Combining Eqs (6) and (1) yields an implicit expression for the radial distribution of shear rate γ(r) within the RBC-rich core,

| (7) |

Since the CFL is occupied by plasma (a Newtonian fluid with viscosity μp), τ = μpγ for R - δ ≤ r ≤ R and Eq (6) yields

| (8) |

Equations (7) and (8) are coupled by the continuity of flow velocity at the interface r = R - δ separating the RBC-rich core and the CFL,

| (9) |

where vz is the flow velocity, and the superscripts + and - indicate the core and plasma velocities on either side of the interface, respectively. The flow velocity is related to the corresponding shear rate by γ = dvz /dr. At the vessel wall (r = R) we impose a no-slip boundary condition, vz (R) = 0.

Given a value of the CFL thickness δ, both the shear rate γ(r) and the flow velocity vz(r) are calculated by solving Eqs (7)–(9). The data reported in [9,29] suggest that δ is relatively insensitive to the blood vessels radius R, but decreases appreciably with the discharge hematocrit Hd. The latter is related to the core hematocrit Hc by mass conservation [33],

| (10) |

While one can choose any functional relation between δ and Hd, for the sake of concreteness we adopt a polynomial relationship:

| (11) |

3. Numerical algorithm for calculating velocity profiles

For given values of the discharge hematocrit Hd and the pressure gradient J, we use the following algorithm to compute the shear rate γ(r) and the flow velocity vz(r):

1. Make an initial guess for Hc. (In the simulation reported below, the linear relationship Hc = 0.9797Hd +0.0404 [33] is used as an initial guess.)

2. Calculate the value of δ by using Eq (11).

3. Compute the shear rate γ(r) in the RBC rich core and the CFL by using Eqs (7) and (8), respectively.

4. Compute the flow velocity .

5. Refine the previous guess for Hc by using Eq (24).

6. Repeat steps 3–5 until the absolute difference between the values of Hc obtained from two sequential iterations is smaller than prescribed tolerance Δ (in the simulations reported below we set Δ = 10-6).

4. Model calibration

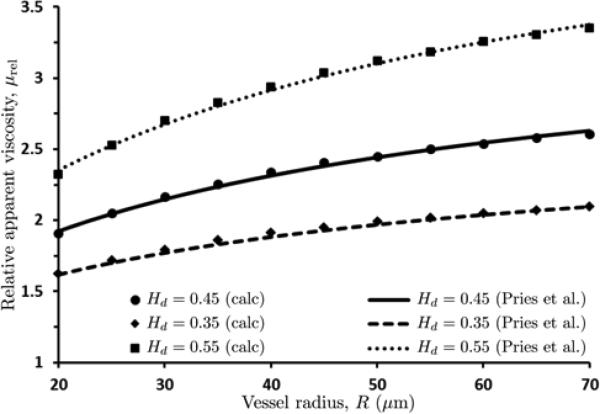

Pries et al. [25] compiled a number of measurements of human blood viscosity conducted in tubes of various radii R for several values of discharge hematocrit Hd. We use these data to calibrate our model, i.e., to determine the values of parameters a0, a1 and a2 in Eq (11). That is accomplished in three steps as follows.

The first step is to evaluate the relative (dimensionless) apparent viscosity μrel that is defined as [25]:

| (12) |

This quantity is routinely inferred from experiments by measuring Q and invoking the Poiseuille law. Instead, for a given value of the CFL thickness δ, we compute Q from the flow velocity vz determined in Section 7.1 as

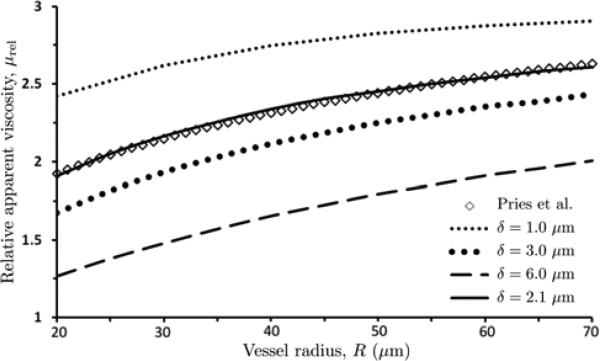

| (13) |

This calculation of Q is then used in Eq (12) to obtain the value of μrel associated with an assumed value of δ. Figure 4 exhibits the resulting dimensionless apparent viscosity μrel as a function of vessel radius R for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.45 and several values of the CFL thickness δ.

4.

Dependence of relative apparent viscosity μrel on vessel radius R, for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.45 and several values of the CFL thickness δ. Also shown is the dimensionless apparent viscosity obtained with the data-fitted curve (14) of Pries et al. [25].

The second step is to compare the relative apparent viscosity curves μrel = μrel(R) in Figure 4 with their counterparts predicted by the data-fitted curve of Pries et al. [25], μPr = μPr(R). The latter is given by

| (14a) |

where μPr,0.45 is the dimensionless apparent viscosity at reference discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.45 fitted with a curve

| (14b) |

And

| (14c) |

In the relations above, R is reported in μm and α is dimensionless. The value of the CFL thickness δ that provides the best agreement between the two approaches is selected. For discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.45 used in Figure 4 this value is δ = 2.1 μm. The fact that agreement between our model (Steps 1 and 2) and the Pries et al. [25] curves persists over a wide range of vessel radii R serves to validate our assumption that the CFL thickness δ is a function of discharge hematocrit Hd alone.

The final step consists of repeating the above procedure for multiple values of discharge hematocrit Hd, tabulating the δ vs. Hd values, and fitting the second-degree polynomial (11) to the resulting dataset. This step results in

| (15) |

where values of δ are in μm. The use of the parameterized constitutive law (15) in our model yields predictions of apparent viscosity μrel(R) that are in close agreement with their counterparts based on the Pries et al. [25] calculations over a physiologically relevant range of discharge hematocrit Hd and micro-vessel radii R (Figure 5).

5.

Relative apparent viscosity μrel calculated with our model and the data-fitted curve of Pries et al. [25] over physiologically relevant ranges of micro-vessel radii R and discharge hematocrit Hd .

5. Model validation

To validate our model, we compare its predictions of the CFL width, blood velocity profiles and tube hematocrit (defined below) with their experimentally observed counterparts. These comparisons are carried out on previously published experimental data that were not used to parameterize our model.

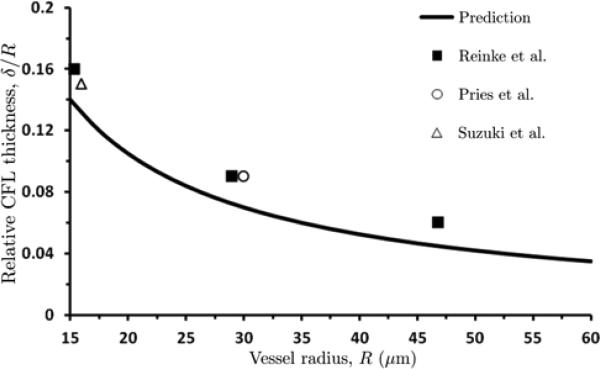

5.1. CFL thickness

The values of CFL thickness δ predicted with the constitutive law (15) fall within a generally accepted range of around 2 to 3 μm [14,24,27,35]. Figure 6 provides a further confirmation of the ability of our model to predict the CFL thickness for a wide range of micro-vessel radii. It compares the dependence of the relative CFL thickness δ = R on vessel radius R predicted with our model and observed in the experiments [24,27,35], for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.45. Our model qualitatively captures the observed decrease of the CFL thickness δ with vessel radius R, underestimating the observed CFL thickness by 13% for R = 15 μm, 20% for R = 30 μm and 25% for R = 47 μm. This level of agreement is significantly better than that achieved with the earlier models [9,31,33].

6.

Predicted and experimentally observed values of relative CFL thickness δ / R as a function of vessel radius R for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.45. Experimental data are from [24, 27, 35].

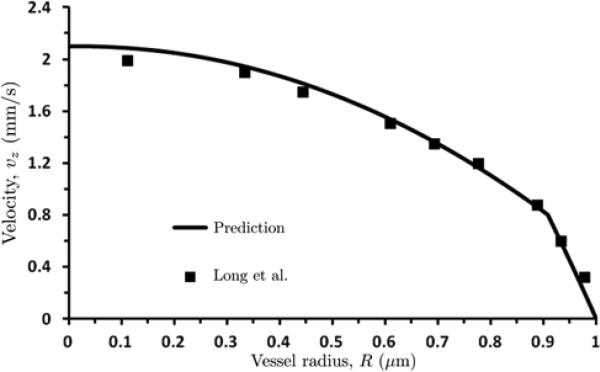

5.2. Flow velocity profiles

We compare the velocity profile vz(r) predicted with our model with its counterpart constructed from experimental micro-PIV (Particle Image Velocimetry) measurements of velocity profiles of human blood flow in glass tubes [18]. Figure 7 shows the predicted and observed velocity profiles for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.335, pressure gradient J = 3732 dyn/cm3 and tube radius R = 27.1 μm used in the experiment [18]. The mean square-root error between the data and predictions is 0.068.

7.

Predicted and observed velocity profiles, plotted against normalized radial distance from centerline r = R, for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.335, pressure gradient J = 3732 dyn/cm3 and tube radius R = 27.1 μm used in [18].

A location of the kink in the experimentally measured velocity profile (r/R ≈ 0.92 in Figure 7) indicates a position of the core/CFL interface r = R - δ). Applied to the experimental data in [18] (see Figure 7), this yields δ ≈ 2.2 μm. This estimate of the CFL thickness δ is much closer to that predicted by our model (δ = 2.48 µm) than values for δ reported in earlier models [9, 31].

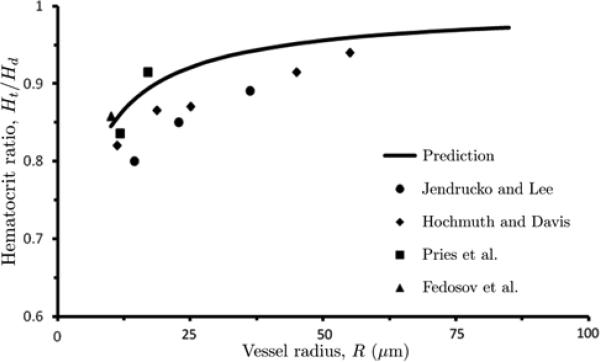

5.3. Tube hematocrit

As a final validation test, we investigate the ability of our model to reproduce measurements of tube hematocrit Ht, which is defined as the average (over a vessel's cross-section) hematocrit [31],

| (16) |

In the two-layer fluid model under consideration, H(r) = Hc inside the RBC-rich core (0 ≤ r ≤ R - δ) and H(r) = 0 inside the CFL (R - δ < r ≤ R). Therefore, this equation predicts a linear relationship between tube hematocrit Ht and core hematocrit Hc [31],

| (17) |

Measurements of tube hematocrit Ht are typically reported relative to discharge hematocrit Hd, i.e., as the ratio Ht / Hd. This ratio is observed to be smaller than unity, a phenomenon that is referred to as the Fahraeus effect [8]. The disparity between values of tube hematocrit Ht and discharge hematocrit Hd is due to the presence of the CFL; the difference between the three types of hematocrit diminishes, Ht ≈ Hc ≈ Hd, as δ/R → 0.

Figure 8 shows the observed [9,11,12,24] and computed dependence of Ht / Hd on vessel radius R for Hd = 0.405. While the mean root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the data and predictions is relatively large (RMSE = 0.052), our model captures the key features of this dependence. The ratio Ht / Hd increases as with vessel radius R, approaching its limiting value of 1 at large R (δ/R→ 0). Moreover, the absolute difference between our calculations and the experimental data does not exceed 11 % and is significantly smaller (less than 4 %) for many data points over a wide range of vessel diameters.

8.

Calculated and measured values of Ht/Hd as a function of vessel radius R, for Hd = 0.405. Data are from [9,11,12,24].

6. Simulation results

The results presented in this section are for pressure gradient J = 40,000 dyn/cm3. The latter corresponds to wall shear stress of 40 dyn/cm2 at R = 20 μm, a value consistent with in-vivo WSS measurements [17] typically observed in the microcirculation.

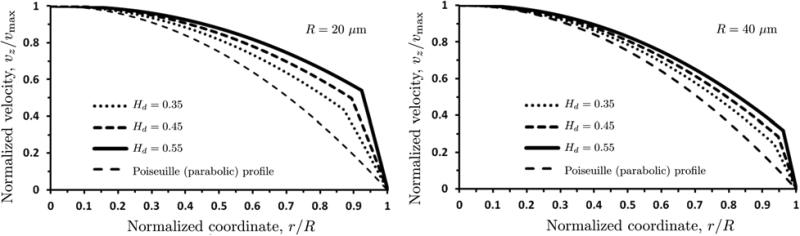

6.1. Flow velocity profiles

The velocity profiles vz(r) computed with our model are blunted, rather than parabolic (Figure 9). Each profile is normalized with the corresponding maximum (centerline) velocity vmax. In a blood vessel of radius R = 20 μm, vmax = 14.9, 11.0 and 7.4 mm/s for discharge hematocrit Hd = 0.35, 0.45 and 0.55, respectively. In a blood vessel of radius R = 40 μm, these increase to vmax = 25.1, 39.0 and 55.0 mm/s for the respective values of discharge hematocrit Hd. Figure 9 also shows the parabolic velocity profiles that arise from the Poiseuille solution for pipe flow.

9.

Velocity profiles vz(r / R), normalized with corresponding maximum (centerline) velocities vmax, for vessel radii R = 20 μm (left) and 40 μm (right) and several values of discharge hematocrit Hd . Also shown is the (normalized) parabolic velocity profile predicted by the Poiseuille law.

The bluntness of the velocity profiles increases with the discharge hematocrit Hd due to two reasons. First, the non-Newtonian behavior of blood becomes more pronounced as hematocrit increases. Second, higher levels of hematocrit lead to higher viscosities of the RBC-rich core, increasing the contrast between the viscosities of the core and the CFL.

Figure 9 also reveals that the non-Newtonian behavior of blood is less pronounced, i.e., the deviation from the Poiseuille's parabolic velocity profile is less significant, in larger vessels. This observation is in line with the standard modeling practice of modeling blood in large vessels as a Newtonian fluid.

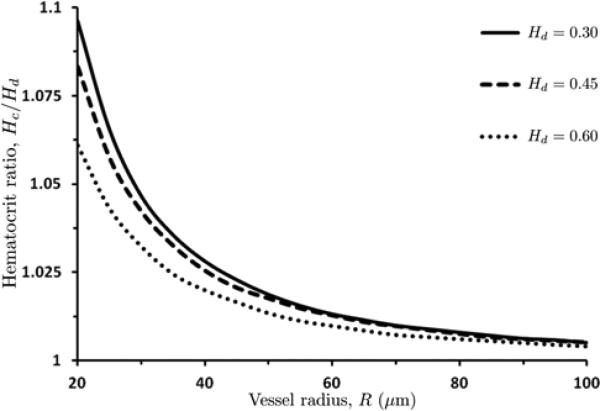

6.2. Relationship between core and discharge hematocrits

Mass conservation of RBCs, as expressed by Eq (24), establishes a linear relationship between the core (Hc) and discharge (Hd) hematocrits (see, also, [33]). Additionally, it defines the (nonlinear) dependence of the hematocrit ratio Hc/Hd on the blood vessel radius R. This dependence, computed with the algorithm of Section 7.1, is displayed in Figure 10 for several values of the discharge hematocrit Hd. As vessel radii become larger, the difference between the core and discharge hematocrits becomes less significant, i.e., the ratio Hc/Hd →1.

10.

Hematocrit ratio Hc / Hd as a function of blood vessel radius R for several values of discharge hematocrit Hd .

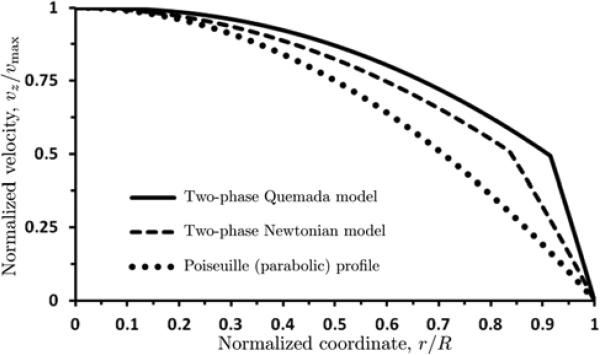

6.3. Comparison with the two-layer Newtonian model

Several previous studies, e.g., [21, 31, 33], treated blood as a two-phase fluid (as we do) but assumed that both the RBC-rich core and the CFL exhibit Newtonian behavior. Comparison of these models with ours sheds light on the impact of the non-Newtonian effects on predictions of both the flow velocity vz and the relative apparent viscosity μrel.

Figure 11 shows the velocity profiles vz(r) in a vessel of radius R = 20 μm, computed with the two-phase Newtonian model [21,31,33] (see Appendix A) and our two-layer Quemada model. Each of these velocity profiles is normalized with its maximum (centerline) velocity vmax (= 1.845 and 1.286 mm/s for the Newtonian and Quemada and models, respectively). Both profiles differ significantly from the parabolic profile predicted by the Poiseuille law. The Newtonian assumption significantly overestimates flow velocity (vmax by about 50%) and underestimates the degree of bluntness of the velocity profile. This is despite the fact that the CFL thickness δ predicted with our model is smaller than that suggested in [31]. It is worthwhile emphasizing that the values of δ predicted with our model fall within the experimentally observed range (1.5 - 3.0 μm), while the estimates of δ in [31] (3.5 - 4.0 μm) do not.

11.

Normalized velocity profiles computed with the two-phase Newtonian model [21,31,33], our two layer Quemada model, and the Poiseuille law. Each velocity vz(r / R) is normalized with its maximum (centerline) velocities vmax. The vessel radius is R = 20 μm and discharge hematocrit is Hd = 0.45.

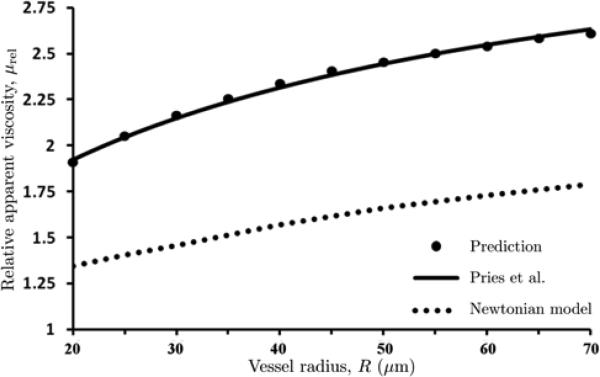

Figure 12 exhibits the dependence of relative apparent viscosity μrel on vessel radius R predicted with the two-phase Newtonian model [21,31,33], our two-phase Quemada model, and the data-fitted curve (14) of Pries et al. [25]. The Newtonian model [21,31,33] underestimates the apparent viscosity, as compared to both our Quemada model and the experimental data in [25]. This demonstrates the importance of accounting for non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior of the RBC-rich core.

12.

Dependence of relative apparent viscosity μrel on vessel radius R, computed with the two-phase Newtonian model [21, 31, 33], our two-layer Quemada model, and the data-fitted curve of Pries et al. [25]. Discharge hematocrit is Hd = 0.45.

7. Consequences for WSS measurements in blood vessels

Measurements of WSS in arterioles are typically done (e.g., [13, 28]) by employing the Poiseuille law, Q = πJR4/(8μ), to express WSS τw = τ(R) in terms of observable quantities such as flow rate Q, average flow velocity vave = Q / (πR2) = JR2/(8μ) or centerline velocity vmax = 2vave. This is accomplished by combining Eq (6) with τ = μγ, the Newtonian relationship between shear stress τ and shear rate γ = dvz/dr. Since for a Poiseuille flow the shear rate at the wall is given by γw = γ(R) = 2vmax/R, one obtains

| (18) |

While Eq (18) is routinely used to estimate the WSS τw from experiments [13, 28], it is important to recognize that it is based on the assumption that blood can be treated as a homogeneous Newtonian fluid. Many theoretical and experimental studies, including our analysis in Section 6, demonstrate the importance of accounting for the non-Newtonian behavior of blood flow in micro-vessels. Experimental techniques, such as microparticle image velocimetry [18], enable one to obviate the need for this assumption by inferring the WSS τw from measurements of the entire velocity profile vz(r). However they are expensive and operationally challenging, which hinders their in-vivo use [13, 28]. We propose an efficient alternative that utilizes standard experimental procedures to determine the discharge hematocrit Hd and a flow characteristic (Q, vave or vmax), relies on the modeling algorithm in Section 7.1 to compute the wall shear rate γw = γ (R), and makes use of the Quemada constitutive law (1) to relate the wall shear rate γw to the WSS τw.

7.1. Algorithm for inference of WSS from blood flow measurements

Given measurements of the vessel radius R, centerline velocity vmax and discharge hematocrit Hd, we employ the following algorithm to determine the WSS τw:

1. Set the counter to n = 0, the algorithm tolerance to ε = 10-4, and the iteration factor to k = 0.9 .

2. Compute an initial guess for the WSS τw (n) by using the Poiseuille relation (18).

3. Compute the corresponding values of the pressure gradient J(n) = 2 τ (n)w /R from Eq (6).

4. Calculate the velocity profile v(n)(r) by using the algorithm in Section 3 with given J(n).

5. Compare the resulting centerline velocity v(n)max with its measured value vmax. If

then go to Step 7. Otherwise, modify the value of the pressure gradient according to

6. Set n = n+1. Go to Step 4.

7. Compute the WSS τw = J(n)R/2 from Eq (6).

For k = 0.90 and ε = 0.0001, this algorithm converged in fewer than 20 iterations in all the cases we examined.

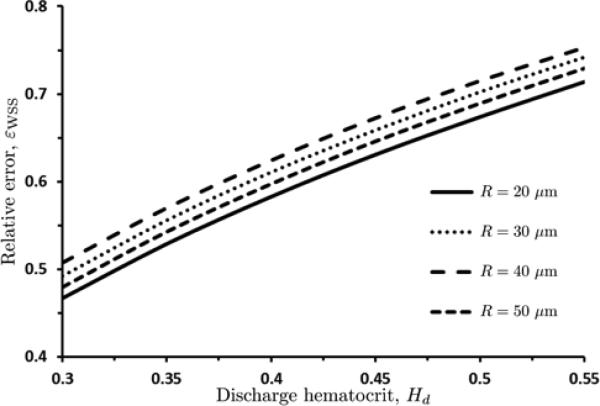

We use the relative error εWSS = (τw - τw,P ) / τw to quantify the errors introduced by relying on the Poiseuille relation (18) to infer the WSS (τw,P), i.e., by ignoring the inhomogeneity and non-Newtonian properties of blood flow in micro-vessels. Figure 13 reveals that the error εWSS is significant over wide ranges of the discharge hematocrit Hd and the blood vessel radius R. This demonstrates that the Poiseuille-law-based experimental inference of the WSS systematically underestimates the WSS in microcirculatory flows. The bias increases with the discharge hematocrit Hd and decreases with the vessel radius R. Both phenomena are to be expected, since they amplify the non-Newtonian behavior of the blood flow in microcirculation (see Section 6).

13.

Relative error εWSS = (τw – τw,P) / τw in estimation of the WSS τw introduced by relying on the Poiseuille relation (18) to infer the WSS (τw,P), for several values of vessel radius R.

7.2. Empirical WSS correction factor

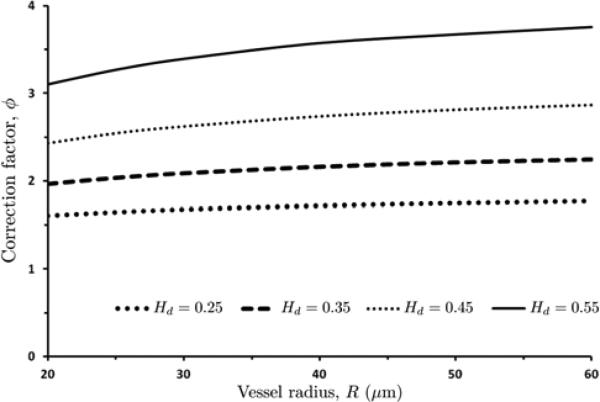

The numerical algorithm described in Section 7.1 provides a rigorous means for inferring the WSS from measurements of R, Hd and vmax. Here we use it to pre-compute a correction factor ϕ(R, Hd), which would allow us to determine the WSS without resorting to numerical simulations. This correction factor allows one to determine the actual WSS τw from its Poiseuille-law estimate τw,P given by Eq (18) by simple multiplication, τw = ϕ(R, Hd) τw,P, i.e.,

| (19) |

The correction factor ϕ(R, Hd) = τw / τw,P is calculated as follows. First, we employ the iterative algorithm of Section 7.1 to compute the WSS τw(R, Hd) for multiple values of R [15μm; 70μm] and discharge hematocrit Hd ∈ [0:25; 0:55]. Then, for each of these computed values of the WSS, we obtain the correction factor as ϕ(R, Hd) = τw / τw,P. Finally, we interpolate this ϕ = ϕ(R, Hd) data set with the curve (with the goodness-of-the-fit exceeding 0:99)

| (20) |

Figure 14 exhibits the dependence of the WSS correction factor ϕ on the vessel radius R and discharge hematocrit Hd. Equation (20) and its graphical representation in Figure 14 show that the correction factor ϕ (and, hence, the errors introduced by the reliance of the Poiseuille law) grows exponentially with the discharge hematocrit Hd. Its dependence on the vessel radius R becomes more pronounced as the discharge hematocrit Hd increases. Substituting eqn. 20 into eqn. 19 yields the corrected equation for WSS estimation as a function of centerline velocity (vmax), vessel radius (R), plasma viscosity (μp) and discharge hematocrit (Hd):

| (21) |

With m1 = 0.0515; m3 = 4.732; m3 = 0.6134; m4 = 1.0548.

14.

WSS correction factor ϕ as a function of vessel radius R, for several values of discharge hematocrit Hd .

We compared the WSS values computed with Eq (19), the iterative algorithm of Section 7.1 and the correction factor in Eq (20) for a physiologically relevant ranges of R and Hd. This comparison reveals that the iterative algorithm and the correction factor yield the nearly identical (within 3 %) estimates of WSS. Both sets of estimates are significantly higher than their counterparts predicted with the Poiseuille relation (18).

The results presented in this study are obtained for parameter values typical of human blood. Therefore, they are applicable both for in-vitro experiments in glass tubes [18] and tissue cultures [20], and for invivo observations such as retinal [30] or MRI [6] studies. For experiments that involve blood from other species, the approach used in this study may be replicated with suitable rheological data for the type of blood under consideration as an input. This would require the measurements of the dependence of the CFL thickness δ on Hd and R, and blood rheology data (which is readily available in the literature for a number of species).

8. Discussion

We presented a two-layer fluid mechanics model in this study, with a non-Newtonian RBC core layer and a Newtonian cell free layer near the vessel wall. The rheology of the RBC core was modeled using the Quemada model [19,22,26] which accurately describes the shear thinning properties of blood over a large range of shear rates and hematocrits. Each fluid layer was assumed homogeneous and immiscible, with the resulting flow assumed to be laminar and axisymmetric.

In order to calculate velocity profiles using this model, we assumed a general functional form of the CFL thickness, δ as a function of discharge hematocrit Hd. We then used Eqs (7) – (11) to calculate flow velocities, flow rates and relative apparent viscosity μrel. We calibrated our expression for δ, given by Eq (11), so that our predictions for apparent viscosity at different hematocrits and radii were in agreement with the work of Pries et al. [25]. Figure 5 shows that our model was successfully able to match the predictions of Pries et al., providing validation to the assumption that δ is an almost linear function of discharge hematocrit and is independent of tube radius.

We were further able to validate our model by comparing i) the predicted velocity profiles with experimental data [18], ii) the predicted hematocrit ratio Ht/Hd vs values reported in the literature (both experimental data and numerical models), and iii) δ / R values with those estimated in experimental studies [27,24,35].

Agreement between our calculated and measured velocity profiles [18] is shown in Figure 7. The calculated values of velocity, shape of velocity profile and CFL thickness are in reasonable agreement with the experiment (see Section 5). Furthermore, our predictions for Ht/Hd fall within the broad range of values suggested in the literature (Figure 8). The scatter in the range of values reported is unfortunately rather large, with very few experiments being carried out in recent years with modern experimental techniques. New experiments to measure tube vs discharge hematocrit would be very useful to help better calibrate flow models of blood flow in microvessels.

Our predictions of CFL thickness δ also seem to be in reasonable agreement with the experiments [14,24,27,35]. Our estimates of δ are closer to the experimentally observed values than those reported in other theoretical studies [31,9,33]. The range of δ predicted for physiological levels of hematocrit (in the vicinity of 0.45) falls between 1.5 μm and 3 µm in most experimental studies. Our predictions of δ in the range of 2.5-1.8 μm over a range of hematocrits from 0.35 to 0.55 are within this range of experimentally measured values. Figure 6 shows that our estimates of δ / R vs R for Hd = 0.45 are in general agreement with the experimental observations [24,27,35].

We also demonstrated the resulting dependence of core hematocrit Hc on discharge hematocrit Hd in small to intermediate sized arterioles, as shown in Figure 10. As the vessel size increases, the importance of the Fahraeus effect [8] reduces and core and systemic hematocrit become essentially indistinguishable, due to the fact that the width of the cell depleted layer becomes negligible compared to vessel radius. Hence, we expect core hematocrit to be almost the same as discharge hematocrit in large blood vessels (where the core is essentially the entirety of the vessel cross section), but in smaller blood vessels the core hematocrit should be significantly elevated over systemic (or discharge) hematocrit.

We examined whether our model makes predictions that are different from the Newtonian model of blood flow used previously in [31,33,21]. Figure 11 provides a comparison of our predictions of the velocity profiles with those computed with the two-layer Newtonian model, for the vessel radius R = 20 μm and the pressure gradient J = 40,000 dyn/cm3. Our two-layer non-Newtonian model predicts significantly smaller axial velocities and blunter velocity profiles than the two-layer Newtonian model does. Sharply blunted velocity profiles are commonly reported in the experimental literature [18,10,1,3,15,36].

We also analyzed the dependence of the relative apparent viscosity on the vessel radius (see Figure 12, for Hd = 0.45). The Newtonian model significantly underestimates the relative apparent viscosities both predicted with our model and observed experimentally (see the data in [25]). Since, with a single optimized set of parameters our model is able to simultaneously predict realistic values of apparent viscosity, CFL thickness, tube hematocrit and velocity profiles that are in broad agreement with the experimental literature, we submit that our model is a significant improvement over prior Newtonian flow models.

The blunting of velocity profiles discussed in this study has a number of consequences. Typical in vivo measurements of WSS in the microcirculation are based on the Poiseuille relation (18), which assumes the Newtonian behavior and results in parabolic velocity profiles [28, 13]. The errors introduced by this assumption lead to a significant underestimation of WSS. Specifically, as shown in figure 13, the relative error in using the Poiseuille relation (eqn. 18) increases with increasing values of discharge hematocrit Hd (since increasing Hd greatly amplifies the non-Newtonian nature of the flow); for Hd = 0.45, the use of the Poiseuille relation underestimates WSS by approximately 60 to 65 %, across a broad range of vessel radii. Even at a smaller, but physiologically relevant Hd = 0.30, WSS was found to be underestimated by over 45% when applying the Poiseuille relation.

We proposed two methods to eliminate these errors: an iterative numerical algorithm which leverages our flow model, and the use of a simple correction factor that can be incorporated into the Poiseuille law. Given a rheological model of the RBC-rich core, both approaches allow the inference of WSS from measurements of vessel radius, centerline velocity and discharge hematocrit. Since the WSS values calculated with these two methods differ by approximately 3 %, one can rely on the correction factor without sacrificing the measurement accuracy. This correction factor varies with the discharge hematocrit Hd and vessel radius R, as shown in Figure 14. The proposed approach is also useful in models where WSS is an input for calculations of quantities such as shear-induced NO production [33, 32].

This analysis and the proposed correction factors should aid in evaluating the changes in shears stress induced by the changes of the composition of blood due to the application of plasma expanders that affect the blood's shear thinning properties [32]. The effects of this type of transfusional intervention appear to be significantly dependent on the rheological changes induced in diluted blood and are becoming the focus of research and development in designing new transfusion strategies [4].

Perspective.

The mathematical model of blood flow in microvessels presented in this study allows for prediction of velocity profiles and CFL thicknesses that were validated against previously published experimental data. The blunted velocity profiles predicted occur due to both the non-Newtonian and non-homogeneous nature of blood flow in microvessels; both factors are accounted for in our model. Typically, the estimation of WSS in experimental studies is achieved through measurement of vessel centerline velocity and radius, followed by the application of the Hagen-Poiseuille law. Due to the non-Newtonian and non-homogeneous nature of blood, using the Hagen-Poiseuille law introduces significant errors in WSS estimation. Using the flow model presented in this study, a correction factor to the Hagen-Poiseuille law was derived to eliminate these errors; allowing for accurate estimation of WSS in experiments.

Acknowledgments

Grants: Study supported in part by USPHS NIH 5P01 HL110900, J.M. Friedman PI. and United States Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Contract W81XWH1120012, A.G. Tsai PI.

List of Abbreviations

- WSS

Wall Shear Stress

- CFL

Cell Free Layer

- RBC

Red Blood Cell

Appendix: Two-phase Newtonian model for flow velocity

According to the two-phase Newtonian model of blood flow [31, 33] the velocity distribution in a microvessel of radius R is given by

| (21) |

Where μc is the viscosity of the RBC-rich core, ξ = r/R and λ = 1 – δ/R. When expressed in μm, the CFL width δ is given by [33]

| (22) |

For human blood, μc is calculated as [31]

| (23) |

Finally, the core hematocrit Hc is related to the discharge hematocrit Hd by [33, 31]

| (24) |

The resulting set of equations is solved by following the procedure described in [33].

References

- 1.Alonso C, Pries AR, Kiesslich O, Lerche D, Gaehtgens P. Transient rheological behavior of blood in low-shear tube flow: velocity profiles and effective viscosity. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:H25–32. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baskurt OK, Hardeman MR, Rampling MW, Meiselman HJ. Handbook of Hemorheology and Hemodynamics, 69 of Biomedical and Health Research. IOS Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop JJ, Nance PR, Popel AS, Intaglietta M, Johnson PC. Effect of erythrocyte aggregation on velocity profiles in venules. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280(1):H222–236. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabrales P, Intaglietta M. Blood substitutes: evolution from noncarrying to oxygen and gas carrying fluids. ASAIO J. 2013;59(4):337–354. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318291fbaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Alginate plasma expander maintains perfusion and plasma viscosity during extreme hemodilution. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288(4):H1708–1716. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00911.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng CP, Herfkens RJ, Taylor CA. Abdominal aortic hemodynamic conditions in healthy subjects aged 50-70 at rest and during lower limb exercise: in vivo quantification using MRI. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168(2):323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien S, Usami S, Taylor HM, Lundberg JL, Gregersen MI. Effects of hematocrit and plasma proteins on human blood rheology at low shear rates. J. Appl. Physiol. 1966;21:81–87. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahraeus R. The suspension stability of blood. Physiol. Rev. 1929;9:562–568. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedosov DA, Caswell B, Popel AS, Karniadakis GE. Blood flow and cell-free layer in microvessels. Microcirc. 2010;17(8):615–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaehtgens P, Meiselman HJ, Wayland H. Velocity profiles of human blood at normal and reduced hematocrit in glass tubes up to 130 mm diameter. Microvasc. Res. 1970;2(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(70)90049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochmuth RM, Davis DO. Changes in hematocrit for blood flow in narrow tubes. Bibl. Anat. 1969;10:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jendrucko RJ, Lee JS. The measurement of hematocrit of blood flowing in glass capillaries by microphotometry. Microvasc. Res. 1973;6(3):316–331. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(73)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katritsis D, Kaiktsis L, Chaniotis A, Pantos J, Efstathopoulos EP, Marmarelis V. Wall shear stress: theoretical considerations and methods of measurement. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2007;49(5):307–329. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Kong RL, Popel AS, Intaglietta M, Johnson PC. Temporal and spatial variations of cell-free layer width in arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H1526–1535. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01090.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koutsiaris AG. A velocity profile equation for blood flow in small arterioles and venules of small mammals in vivo and an evaluation based on literature data. Clin. Hemorheol. Micro. 43(321-334):2009. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ku DN. Blood flow in arteries. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1997;29:399–434. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipowsky HH, Kovalcheck S, Zweifach BW. The distribution of blood rheological parameters in the microvasculature of cat mesentery. Circ. Res. 1978;43:738–749. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long DS, Smith ML, Pries AR, Ley K, Damiano ER. Microviscometry reveals reduced blood viscosity and altered shear rate and shear stress profiles in microvessels after hemodilution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10060–10065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcinkowska-Gapinska A, Gapinski J, Elikowski W, Jaroszyk F, Kubisz L. Comparison of three rheological models of shear flow behavior studied on blood samples from post-infarction patients. Med. Bio. Eng. Comput. 2007;45:837–844. doi: 10.1007/s11517-007-0236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mashour GA, Boock RJ. Effects of shear stress on nitric oxide levels of human cerebral endothelial cells cultured in an artificial capillary system. Brain Res. 1999;842(1):233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01872-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nair PK, Hellums JD, Olson JS. Prediction of oxygen transport rates in blood flowing in large capillaries. Microvasc. Res. 1989;38:269–285. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliver JD. Master's thesis. MIT; 1986. The viscosity of human blood at high hematocrits. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popel AS, Johnson PC. Microcirculation and hemorheology. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2005;37:43–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.37.042604.133933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pries AR, Kanzow G, Gaehtgens P. Microphotometric determination of hematocrit in small vessels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1983;245(1):H167–177. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.1.H167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pries AR, Neuhaus D, Gaehtgens P. Blood viscosity in tube flow: dependence on diameter and hematocrit. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1992;263:H1770–1778. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quemada D. Rheology of concentrated dispersed systems: III. General features of the proposed non-Newtonian model: Comparison with experimental data. Rheol. Acta. 1978;17:643–653. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinke W, Gaehtgens P, Johnson PC. Blood viscosity in small tubes: effect of shear rate, aggregation, and sedimentation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1987;253:H540–547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.3.H540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reneman RS, Arts T, Hoeks AP. Wall shear stress–an important determinant of endothelial cell function and structure–in the arterial system in vivo. Discrepancies with theory. J. Vasc. Res. 2006;43:251–269. doi: 10.1159/000091648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter V, Savery MD, Gassmann M, Baum O, Damiano ER, Pries AR. Excessive erythrocytosis compromises the blood-endothelium interface in erythropoietin-overexpressing mice. J. Physiol. 2011;589:5181–5192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.209262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riva CE, Grunwald JE, Sinclair SH. Laser doppler velocimetry study of the effect of pure oxygen breathing on retinal blood flow. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1983;24(1):47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharan M, Popel AS. A two-phase model for flow of blood in narrow tubes with increased effective viscosity near the wall. Biorheology. 2001;38:415–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sriram K, Salazar Vázquez BY, Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Intaglietta M, Tartakovsky DM. Autoregulation and mechanotransduction control the arteriolar response to small changes in hematocrit. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;303(9):H1096–1106. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00438.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sriram K, Salazar Vázquez BY, Yalcin O, Johnson PC, Intaglietta M, Tartakovsky DM. The effect of small changes in hematocrit on nitric oxide transport in arterioles. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;14(2):175–185. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sriram K, Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Meng F, Acharya SA, Tartakovsky DM, Intaglietta M. PEG albumin supra plasma expansion is due to increased vessel wall shear stress induced by blood viscosity shear thinning. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;302(12):H2489–2497. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01090.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki Y, Tateishi N, Soutani M, Maeda N. Flow behavior of erythrocytes in microvessels and glass capillaries: effects of erythrocyte deformation and erythrocyte aggregation. Int. J. Microcirc. Clin. Exp. 1996;16(4):187–194. doi: 10.1159/000179172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tangelder GJ, Slaaf DW, Reneman RS. Velocity profiles of blood platelets and red blood cells flowing in arterioles of the rabbit mesentery. Circ. Res. 1986;59:505–514. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]