Abstract

Musculoskeletal injuries during military and sport-related training are common, costly and potentially debilitating. Thus, there is a great need to develop and implement evidence-based injury prevention strategies to reduce the burden of musculoskeletal injury. The lack of attention to implementation issues is a major factor limiting the ability to successfully reduce musculoskeletal injury rates using evidence-based injury prevention programs. We propose 7 steps that can be used to facilitate successful design and implementation of evidence-based injury prevention programs within the logical constraints of a real-world setting by identifying implementation barriers and associated solutions. Incorporating these 7 steps along with other models for behavioral health interventions may improve the overall efficacy of military and sport-related injury prevention programs.

Keywords: implementation, injury prevention, research framework, program design, sports, military

Musculoskeletal injuries place the greatest burden on military service members and the types of injuries sustained by military service members are similar to those commonly seen and treated in most sports medicine clinics.1 This is true whether they are participating in military training activities or deployed in support of military operations such as Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom.2,3 Despite our growing understanding of the risk factors associated with the incidence of lower-extremity musculoskeletal injuries in military populations, implementing effective injury prevention programs within the context of the military has been challenging.4 A major challenge to effective injury prevention practice is translating research outcomes into actions and programs that can be effectively implemented in real-world training settings.5 Training programs designed to reduce the risk of these injuries in military training populations have shown promise6; however the wide-spread implementation of these programs has not been realized. The purpose of this paper is to review critical steps in successfully developing and implementing injury prevention programs in military and civilian populations.7

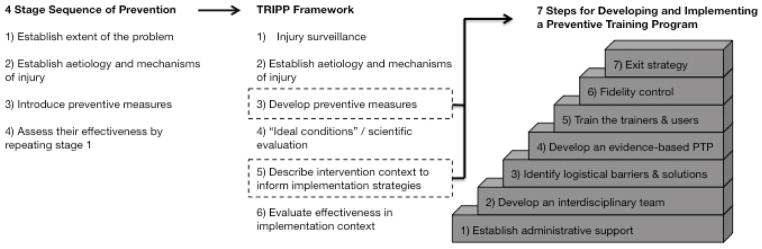

Sports injury prevention research has often used a “sequence of prevention” model that outlines four steps needed to develop an evidence base about sports injuries and their causative factors.8 Unfortunately, this model does not take into consideration the need to translate research findings into practical, effective injury prevention interventions that can be consistently implemented in real-world settings.5 Specifically, this model does not consider the importance of implementation issues--such as ways to achieve wide-spread reach, adoption, compliance and long-term maintenance--for prevention programs that have been proven to be effective. Descriptions and recommendations for implementing efficacious sports injury prevention programs in real-world settings are limited although recent research suggests that investing in implementation planning can enhance intervention uptake in community sport.9 The lack of attention to implementation issues in sports injury prevention research is a major factor limiting our ability to harness the potential of effective injury prevention. Specifically, deficiencies in our ability to translate research findings from controlled laboratory settings to the broader community and military greatly limits the public health impact of current prevention programs.5,10–12

Finch identified the real-world implementation limitations of the ‘sequence of prevention’ model, and proposed a six-stage framework that expands on the original four-step approach; the Translating Research into Injury Prevention Practice (TRIPP) framework.5 The TRIPP framework includes a focus on describing and assessing the intervention implementation context and the effectiveness of injury prevention programs in real-world settings.5 However, the TRIPP framework does not provide specific guidance on the steps needed to develop and implement an evidence-based prevention program within the logistical constraints of a real-world setting. We propose 7 steps that can be used to operationalize Stages 3 and 5 of the TRIPP framework and other models for behavioral health interventions (Figure 1). These 7 steps aim to guide the design and plan the implementation of an evidence-based preventive training program (PTP) within a real-world setting by identifying implementation barriers and associated solutions as a critical component of the process. This is critical for injury prevention efforts in real-world settings as a “one size fits all” approach is not always feasible across organizations and different high risk populations (e.g. military vs. youth soccer).

Figure 1.

Seven steps for effective preventive training program design and implementation – an evolution of sports injury prevention models.

The 7 steps for designing and planning the implementation of the PTP were informed by our experiences with the Joint Undertaking to Monitor and Prevent ACL Injury Study (JUMP ACL study). The JUMP ACL study began as a multi-site prospective cohort study investigating biomechanical and neuromuscular risk factors for non-contact / indirect contact ACL injury at The United States Military, Naval, and Air Force Academies.13 The second phase of JUMP ACL has focused on developing and implementing a PTP as part of a cluster randomized controlled trial at the United States Military Academy at West Point from 2010 to 2014. The PTP was delivered as a set of exercises performed as a dynamic warm up prior to physical training. Our experiences during the this phase of the JUMP ACL study have led us to appreciate the importance of including additional steps within the TRIPP framework to optimize the translation of effective PTPs. By following these 7 steps during the PTP’s design (TRIPP Stage 3) and implementation planning (TRIPP Stage 5) processes, we have been able to achieve high levels of compliance and implementation fidelity when implementing a PTP in a military setting.14 We believe that the lessons learned through this process also have utility in developing and implementing PTP’s in youth sports and civilian populations at high risk for sports related lower extremity injuries.

1) Establish Administrative Support

Assets and resources are typically focused on the mission of any organization and these behaviors reflect leadership priorities. Initiatives that do not have leadership support generally receive inadequate resources to support their initial and ongoing success. As a result, it is imperative to obtain leadership buy in and support for injury prevention efforts and to ensure that an organization’s leadership is committed to implement any new intervention15,16 and “permission to implement” should be negotiated before developing an intervention. If the PTP is not a leadership priority it will likely have little chance of initial success and long-term sustainability within the target population, regardless of whether being implemented in a youth sports league or a military training environment.

To achieve “permission to implement” the PTP in the JUMP ACL study, we met with key administrative leaders and stakeholders to brief them on the current science supporting PTP’s and the potential benefits (i.e. injury prevention and performance improvement) of implementing a PTP. We emphasized how these benefits were aligned with achieving the overall organizational mission and objectives. Specifically, reducing the burden of lower-extremity musculoskeletal injuries, such as ACL tears and stress fractures, increasing force readiness and limiting lost duty days due to injury. A similar argument could be made to a youth soccer league board of directors that focuses on their concerns and goals (e.g., player safety, improved performance, parent marketing) as an organization. As with the introduction of any innovation in an organization,15 it is critical to demonstrate that the benefits of implementing a PTP are directly aligned with the overall mission and goals of the organization.

Administrative leaders and stakeholders are more likely to implement new programs that are compatible with how they are evaluated for professional success.17 Thus, when briefing administrative leaders and stakeholders we believed it was important to highlight how implementing a PTP could positively impact how they were evaluated for both individual and organizational success. For example, in a military training environment key metrics might include improvements in physical fitness as measured by the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) or low attrition rates due to injury. Aligning PTP outcomes with these organizational metrics can enhance buy in and commitment from key stakeholders.

We highlighted the following points during our briefings to establish administrative support and buy-in for the PTP. First, we drew their attention to the negative outcomes associated with training-related injuries. We emphasized that such injuries are common, costly, result in significant time loss during training, reduce overall performance and military readiness and ultimately decrease capacity to achieve organizational goals and mission essential tasks. Second, we proactively addressed the common belief that implementing a PTP will mean less time will be available for other training, thus detracting from organizational goals and success. To do this we highlighted previous research demonstrating that PTP’s can be completed in short time periods,18 and are effective in decreasing musculoskeletal injury rates,18–20 and improving athletic performance.18,21,22 We believed it was important to emphasize how implementing a PTP would not detract from the organization’s goals, but rather would reduce overall costs while simultaneously improving performance. These benefits may help improve organizational efficiency and amplify the positive effects of other training measures to achieve organizational success.

Another common barrier for achieving “permission to implement” can be an organization’s belief that the program they have in place is already achieving the desired outcome. To overcome this barrier in the JUMP ACL study we provided information to the administrative leadership and key stakeholders. We emphasized that the existing warm-up program did not incorporate evidence-based exercises shown to improve biomechanics associated with injury risk and mechanisms, reduce injury rates, and improve athletic performance measures. Thus, we highlighted the relative advantage of what was being proposed over the current practice16 and the benefits of refining and optimizing what was already in place and working together to design and implement an evidence-based PTP. This allowed us to collaborate with the administrative leaders and stakeholders in developing a PTP that was aligned with their organizational goals that would fit within the context of existing schedules and programs. This type of collaborative program design may help establish trust with the organization and ultimately achieve “permission to implement.” This approach is also likely to foster support for long-term sustainability following the initial implementation cycle, which is important when developing an exit strategy as outlined in step 7 below.

2) Develop an Interdisciplinary Implementation Team

Having obtained administrative support for program implementation, we developed an interdisciplinary implementation team to assist with developing the PTP and its associated implementation strategy. This is in line with key steps in a range of implementation planning frameworks and process described in the literature.15,23 We involved key stakeholders to ensure that the PTP we developed was both evidence-based and context-specific. Key stakeholders may include program implementers (those involved in program development and operations), partners (those who actively support the program), participants (those served or affected by the program), and decision makers (those in a position to do or decide something about the program). In the context of implementing a PTP, key stakeholders may include program designers, trainers, end users (e.g., non-commissioned officers, coaches), healthcare providers, and administrators. It may also be important to engage potential critics or adversaries of the program to avoid potential barriers during implementation. In working with community based programs it is also probably important to include athletes, parents, coaches, and other stakeholders that may have a vested interest in the PTP within the target population.

The primary role of the interdisciplinary implementation team was to identify and suggest possible solutions for all potential logistical issues that could negatively influence the fidelity, compliance, and long-term adoption of the PTP. It was also important to attempt to limit the impact of any injury prevention efforts on activities that organizational leaders deemed critical to their primary mission (training military officers). This was accomplished by the interdisciplinary team through working closely with leaders and key stake holders to identify the proper timing and sequence for PTP delivery around mission essential activities. We achieved a comprehensive, multi-perspective view of potential logistical barriers to implementation through our discussions. Recommendations for exercise inclusion were solicited from these key stakeholders to ensure that the PTP was not only focused on injury prevention but also on improving physical performance in areas that were important to the organization. For example, push-up performance is important for the military and the push-up is also a good exercise to work on core stability when performed correctly, so this exercise was included in our PTP to satisfy the shared goals of the organization and program planners.

3) Identify Logistical Barriers and Solutions

We grouped the identified “implementation barriers” into four main categories: time, personnel, environment, and organization. The following “implementation barriers” were identified by our interdisciplinary implementation team:

Time

Time of day the PTP would be performed

Duration of each PTP session

Frequency with which the PTP would be performed each week

Opportunity costs for using training time for PTP

Personnel

Experience and expertise of those leading the PTP

Baseline movement quality of those performing the PTP

Previous experience in performing injury prevention exercises of those performing the PTP

Environment

Location/setting in which the PTP will be performed

Equipment available when performing the PTP

Organization

Organizational goals and metrics of success

Current warm-up endorsed by the organization

Once identified, in partnership with the interdisciplinary implementation team we mapped a set of potential solutions to address each of the implementation barriers. In line with the concept of developing health behavior change interventions with the application in mind when,24 the solutions were then incorporated into the design of the evidence-based PTP and integrated into the overall implementation strategy. An example of the “solutions map” for the implementation barriers is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Map of logistical implementation barriers and associated solutions

| PTP Design | Identified Implementation Barrier | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Total Program Duration | 5 weeks to implement the PTP | Identify key PTP goals that could be attained in 6 weeks and design PTP accordingly |

|

|

||

| Session Duration | 12 minutes to complete PTP each training session | Determine exercises that can achieve identified PTP goals (see above) and be performed and mastered within the allocated time |

| Additional time may be available to complete the PTP on certain days due to overall training schedule | If individuals have not mastered exercises, then repeat those exercises If time permits, repeat more demanding exercises |

|

|

|

||

| Location | PTP will be performed in different locations on a regular basis | Visit each location that PTP will be performed and ensure that exercises can be performed in that location |

| PTP will be performed in small areas with individuals tightly grouped together | Select PTP exercises that can be performed in a relatively stationary location | |

|

|

||

| Organization’s Goals | Pass physical fitness test at end of training period | Demonstrate that the PTP will not detract to passing physical fitness test, and may ultimately enhance performance and ability to pass physical fitness test |

| Develop fundamental skills | Demonstrate that the time to complete the PTP will not infringe upon other training goals and will accomplish their goal to “warm up” prior to other physical training. Demonstrate how mastering the PTP exercises develops fundamental motor skills that may improve ability to master other fundamental skills |

|

| Develop leadership skills | Demonstrate that PTP can provide opportunities for leadership development with those leading the exercises and by providing feedback to others on PTP quality | |

|

|

||

| Success Metrics | 40 push ups in 2 minutes 100 sit ups in 2 minutes 1.5 mile run in 10 minutes |

Ensure that administrators, implementers, and users see how the selected PTP exercises contribute to meeting these success metrics. Demonstrate the program has face validity. |

|

|

||

| Equipment | No available equipment to use with PTP implementation | Select PTP exercises that do not require use of additional equipment |

4) Develop an Evidence-Based and Context-Appropriate PTP

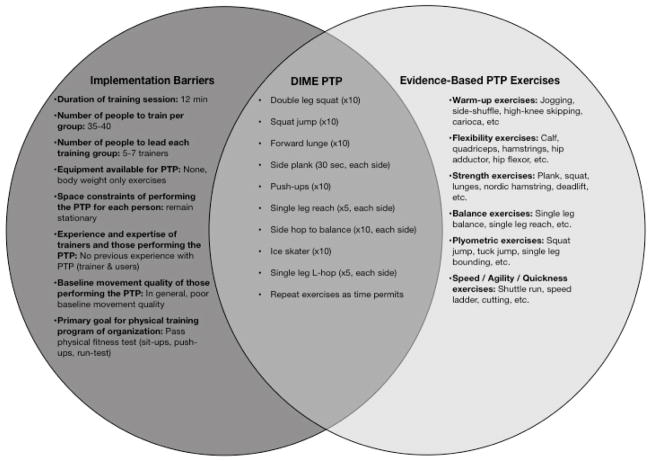

The specific PTP exercises were selected after a systematic review of the existing literature to identify those exercises previously used in successful PTP’s while considering the previously identified context-specific implementation barriers. Those exercises that were evidence-based, would best meet the needs of the organization and would address the implementation barriers were selected for inclusion in the PTP. As noted above, we also worked with the interdisciplinary team and key stakeholders to select exercises that would also support and enhance military physical performance. The outcome of this process was the “Dynamic Integrated Movement Efficiency” (DIME) PTP (Figure 2). The DIME PTP represents an evidence-based PTP that provided solutions for the problem of lower extremity injuries within the organization. Furthermore, the DIME PTP was designed to be performed within the previously identified logistical constraints and align with organizational goals for success.

Figure 2.

Development of the DIME PTP using a solutions oriented process to address implementation barriers using evidence-based exercises for injury prevention.

It is important to note that the specific exercises included in the DIME PTP were only finalized after achieving administrative support, establishing an interdisciplinary team, and identifying appropriate solutions to all implementation barriers. Traditionally, implementation of injury prevention programs begins with trying to convince an organization that they should adopt a pre-established set of exercises. This approach often results in sub-optimal levels of compliance and long-term maintenance.9,25,26 This traditional approach is not based on a collaborative process between administrative leaders, key stakeholders, and those seeking to develop and implement the PTP. Often this is a lost opportunity to develop a level of trust between all parties and ensure that the mutual goals of all key stakeholders are addressed during the development and implementation of the PTP. In addition, the pre-established set of exercises may not fit the implementation context or take the “implementation barriers” of the organization and setting into account. While it is important to have a general idea for the specific evidence-based exercises to be included in the PTP, we believe the content of the PTP should not be finalized until going through the initial three steps, thus ensuring that the program is collaboratively designed, meets the organization’s needs, and can be implemented within the identified logistical constraints. These steps are critical to facilitate buy in and support for the program among key stakeholders and end users and will likely enhance long-term sustainability following the initial implementation cycle.

5) Train the Trainers and Users

After working with key stakeholders to develop the DIME PTP, we then developed educational strategies and support materials to train those who would be leading the program (trainers) and delivering it to the end-users. To address one of the acknowledged key drivers of implementation success,10 the goal was to develop high levels of competency and self-efficacy among the trainers who would be leading the DIME PTP. In addition, we sought to achieve buy-in from the trainers by highlighting that the organization supported the implementation of the DIME PTP and that it was aligned with organizational goals for success. We focused our “train the trainer” process around five areas: effectiveness, alignment, knowledge, self-efficacy, and feedback.

A 2-hour educational workshop was held a month before implementing the DIME PTP. The workshop was divided into lecture and hands-on application components. During the lecture we addressed the areas of effectiveness, alignment, and knowledge to instill a positive attitude for performing the DIME exercises in the trainers. Effectiveness was addressed by highlighting the positive outcomes associated with implementing the PTP, such as reduced injury rates,18–20 reduced organizational costs,27 and improved organizational performance.28 We also emphasized how the DIME PTP was designed by an interdisciplinary team, including their organizational leaders and stakeholders, ensuring that the program was in alignment with the overall goals of the organization. In addition, we demonstrated that the DIME PTP could be implemented within the identified logistical constraints (e.g. time, equipment, location, etc.) and would enhance, rather than detract from other training. This process highlighted that there were no “implementation barriers” to prohibit compliance with the program. We then focused on instilling the requisite knowledge in how to perform and lead the DIME PTP. This was accomplished by ensuring that the trainers understood the overall purpose of the exercise program and the rationale for including each exercise in the program. The trainers were informed about how each exercise achieved specific injury prevention and performance enhancement goals. Movement quality or technique is one of the most critical aspects influencing the success of an injury prevention program.29 As such, significant emphasis was placed on the importance of excellent movement quality or technique when performing each of the DIME PTP exercises rather than on the quantity of repetitions completed. Common movement quality / technique errors and corresponding corrective instructions were also described for each of the DIME exercises. A final component of developing a positive attitude was focused on providing examples of other high-level athletes who commonly perform PTP exercises, similar to the DIME.

After the lecture component of the educational workshop, we conducted hands-on training where the trainers performed each of the exercises, learned to lead and teach the exercises, and practiced providing feedback to correct movement quality / technique errors. During the hands-on training process we focused on ensuring the trainers were able to:

Explain the rationale (injury prevention and performance enhancement) for each exercise

Perform each exercise with proper technique

Identify technique errors and poor movement quality during each exercise

Provide general and targeted instructional cues to improve technique and movement quality

Modify the difficulty level of each exercise to ensure proper technique and movement quality was achieved

After conducting several hands-on “train the trainer” sessions, strategies to better engage with the trainers and achieve higher levels of buy-in and self-efficacy were developed. First, we identified that it was important to always provide positive reinforcement when educating trainers about the rationale and how to perform the exercises. Most trainers had no experience with performing or leading injury prevention exercises and had minimal expertise in assessing movement quality. Thus, we used positive reinforcement when coaching the trainers on their leading of the PTP to keep the trainers committed to the DIME PTP. Second, we avoided using negative feedback when correcting the trainers on how they were performing the exercises or providing instructions to others. Rather we identified “ways to improve” the performance and leading of the exercises by the trainer. This was done to avoid negative associations with performing and leading the DIME PTP. Finally, we limited our feedback on “ways to improve” to only a few (2–3) specific items. We found that focusing on multiple items was often confusing to the trainers. Thus, we prioritized the most important technique and movement quality errors for each exercises and limited feedback to these few items.

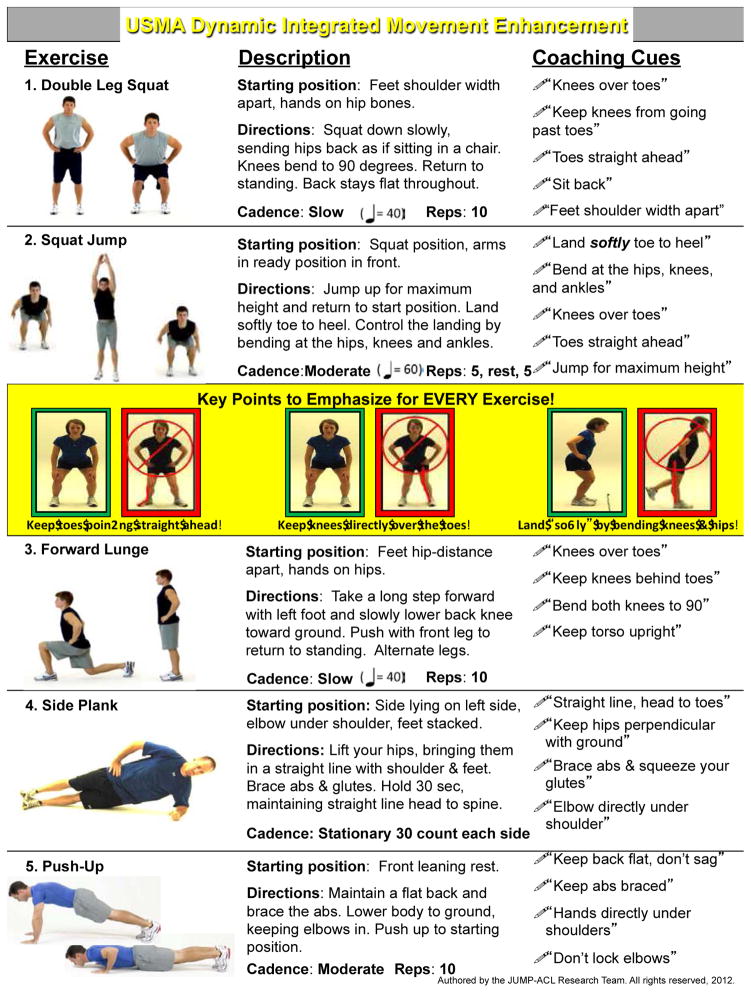

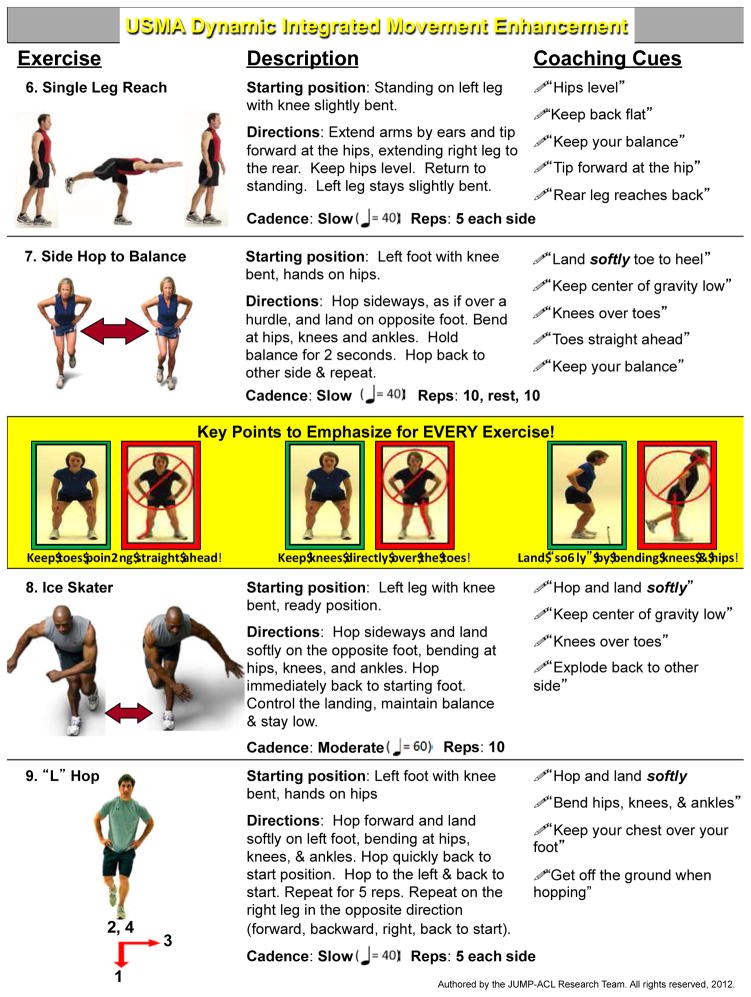

Supplemental materials were developed to reinforce the information presented during the educational workshop. This “Trainers’ Toolkit” included a detailed handbook describing each DIME PTP exercise, a laminated 8.5 × 11 inch “clipboard sheet” with an overview of each exercise (Figure 3). The clipboard sheet also included reminders of common errors and instructional cues to provide when leading the DIME PTP exercises. In addition, trainers were given a website (http://dimeinjuryprevention.weebly.com/) containing videos of:

Figure 3.

Clipboard sheets provided as supplemental educational materials to facilitate high-fidelity implementation of the DIME PTP by trainers.

Examples of correctly performing each of the DIME PTP exercises

Examples of common exercise technique errors and corresponding instructional cues

Quizzes to identify those performing exercises with good and poor technique

Discussions of real-world applications of DIME PTP exercises

Supporting research for implementing the DIME PTP

The purpose of the Trainers’ Toolkit was to further improve the trainers’ perceived control and self-efficacy for implementing the DIME PTP.

Providing adequate training and support materials to those who will be implementing the PTP is critical. We solicited input from the trainers along the way during the initial development and pilot testing of the DIME and modified or added support materials that they suggested would enhance their confidence and ability to model, teach, and provide feedback on the PTP exercises. The overall goal was to establish the background knowledge and confidence to implement the program, ensure that all trainers could perform all exercises, and that they could identify and correct critical movement errors. To ensure this was achieved we also implemented strategies to monitor fidelity control and provide feedback to trainers during implementation process.

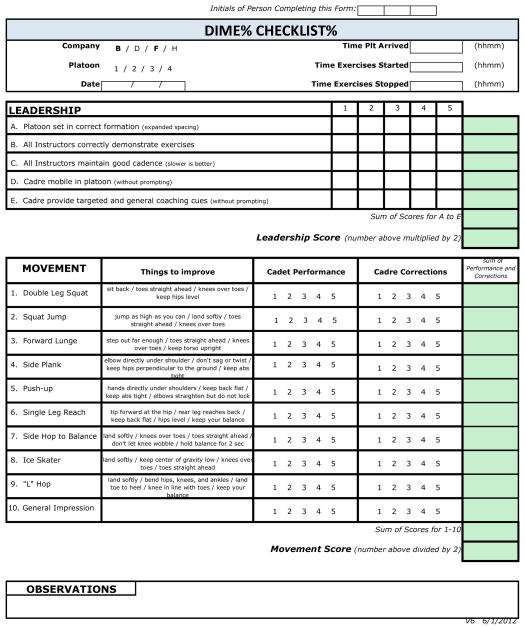

6) Fidelity Control

The DIME PTP was implemented 3–5-times per week over a 5-week training period (17 total training sessions). In order to provide on-the-job coaching and performance assessment30 we developed a scoring rubric to evaluate the fidelity of implementation of the DIME PTP (Figure 4). During each training session we evaluated the leadership abilities of the trainer as they led their group through the DIME PTP exercises. We also evaluated how well the group performed each exercise and the ability of each trainer to provide appropriate instructional cues. “Leadership”, “exercise execution”, and “overall” scores were then developed based on the evaluation rubric. At the end of each training session we reviewed scores with the trainer and provided feedback on a few key “ways to improve” for the next training session. This information was also translated to key members of the leadership team during the intervention cycle.

Figure 4.

Scoring rubric to evaluate fidelity of DIME PTP implementation.

We felt it was important to establish positive associations with leading and performing the exercises to achieve long-term adoption and compliance with the DIME PTP. Thus, many of the lessons learned during the initial pilot “train the trainer” sessions were applied when providing on-the-job coaching and feedback to the trainers after each training session (e.g. positive reinforcement, ways to improve), as we did not want to facilitate any negative associations. In the future, we believe it may be important to emphasize to the end-user that after performing the DIME exercises they are now “warmed up and ready for training” the remainder of their training program. This may help to establish a sense of achievement and reward when completing a PTP, thus helping to facilitate the desire to continue to perform the exercises in the future.

7) Exit Strategy

Given the existing logistical constraints of a military training environment, we provided support for the implementation of the DIME PTP over a 5-week training period. Time based completion of PTP’s may not be ideal for achieving success and an alternative approach based on achieving pre-defined goals may be more desirable if it fits within the implementation context. We suggest that objective criteria for achieving “high-fidelity implementation” should be established by the interdisciplinary implementation team during step 2. This can be evaluated using a fidelity score, such as previously described. Once pre-defined levels of high-fidelity implementation have been achieved it may be appropriate to scale back the level of support. For example, transitioning from daily on-the-job coaching and feedback to 2–3 times per week may be appropriate once high-fidelity implementation is achieved. Assuming that implementation fidelity remains high, further reducing the level of support to random observations can occur over time. However, if implementation fidelity decreases, then it may be appropriate to increase monitoring frequency and provide additional on-the-job coaching and feedback. The key is to have pre-defined objective criteria for the withdrawal of support that are based on program fidelity, not simply time if possible.

Following the training period the interdisciplinary implementation team met to discuss ways to refine the DIME PTP design and implementation strategies in the future. All members of the interdisciplinary implementation team were asked to provide feedback on ways to address potential barriers for long-term adoption across all administrative levels. To ensure long-term adoption and PTP sustainability we developed strategies for addressing each of the issues raised and presented these solutions to the team at a later date and sought their feedback and consultation. This allowed us to continue the collaborative process of refining and implementing the DIME PTP. It also allowed us to provide materials and resources that the end-users deemed important to support ongoing sustainability for the program.

The exit strategy should also consider ways to embed the implementation strategies (e.g. educational workshop, hands-on training, on-the-job coaching and feedback) into the systems of the organization. Future high-fidelity implementation of the PTP will require continued delivery of these implementation strategies, thus these strategies will need to become part of the organizations normal operating procedures. Data that the organization routinely collects (e.g. fitness test scores, injury surveillance data, etc.) may be used to support the on-going implementation (maintenance) of the PTP. For example, highlighting positive associations between PTP implementation with fitness test scores and injury rate reductions may strengthen the organization’s long-term commitment to implementing the PTP (maintenance).

Summary

Our experience implementing the DIME PTP in a real-world military training environment led to the development of the 7-steps for PTP design and implementation planning that can be used to operationalize stages 3 and 5 of the TRIPP framework and other models for implementing behavioral health interventions. Perhaps the most important lesson learned was the significance of working with an interdisciplinary implementation team to consider the intervention implementation context and identify implementation barriers with associated solutions before designing the final version of the PTP. To date, the majority of research on sport injury prevention programs has focused solely on the content of the program (i.e. the specific exercise selection and program duration) without considering the context in which the program is to be implemented by other key stakeholders including the program trainers, coaches, and end-users.

Our experience suggests that to achieve optimal implementation compliance and long-term adoption (maintenance) and sustainability we must first develop administrative support within the organization for which the PTP is intended. After administrative support is established, it is imperative that an interdisciplinary implementation team be developed comprising key stakeholders from multiple levels within the target organization. Development of an interdisciplinary implementation team will ensure the most effective and efficient identification of barriers prior to implementation of the PTP that may otherwise be ignored if stakeholders from multiple sectors of the intervention context are not involved in the planning process. Potential program critics should also be consulted during the process to identify potential barriers. Identifying barriers to implementation before PTP implementation facilitates development of an evidence-based and context-appropriate PTP that has a greater probability of wide-spread adoption, high-level implementation compliance, maintenance, and sustainability within the target organization.

Once the PTP has been designed to circumvent implementation barriers, the program is ready for implementation within the target organization, and leaders can be trained to effectively implement the program. It is vital that the implementation team establishes a high-level of competence and self-efficacy within the trainers to ensure they are comfortable instructing individuals how to successfully perform the exercises as intended prior to initiating the PTP. Trainers should also feel they are competent in exercise error identification and correction. As trainers develop a high-level of competence and self-efficacy they can be transitioned into receiving on-the-job coaching and feedback over a decreasing schedule. However, the feedback schedule should only be decreased as the organization meets objective checkpoints for high-fidelity implementation and performance of the PTP. Once objective high-fidelity implementation of the PTP is achieved, the implementation team can begin to withdraw from the target organization with a planned exit strategy that facilitates long-term sustainability and maintenance of the PTP. We believe that integrating these seven steps as part of the PTP design and implementation strategy can enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of an injury prevention program in real-world settings.

Key Points.

The Translating Research into Injury Prevention Practice (TRIPP) framework describes 6 stages in injury prevention. This paper provided details on implementing injury prevention movement training programs, with an emphasis on “developing the injury prevention intervention” (Stage 3) and to “describing the implementation context to inform implementation strategies” (Stage 5). We address both the military and civilian setting.

Establish administrative support for the preventive training program and develop an interdisciplinary implementation team of key stakeholders to identify implementation barriers and develop solutions to overcome these barriers before designing a preventive training program.

Base preventive training programs on the best available evidence and engineer programs to address all identified implementation barriers.

Establish a high-level of competency and self-efficacy in the trainers who lead the exercises before “going live” with the preventive training program.

Provide regular on-the-job coaching and feedback to trainers using positive reinforcement, simple and targeted suggestions of “ways to improve”, and quantitative measures of program fidelity.

Reduce the frequency and quantity of on-the-job coaching and feedback to trainers as they meet objective criteria for high-fidelity implementation and performance of the program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Darin A. Padua, Email: dpadua@email.unc.edu, Department of Exercise and Sport Science, University of North Carolina, 204 Fetzer Hall, CB #8700, Chapel Hill, NC, USA 27599-8700, (o) 919.843.5117; (fax) 919.962.0489.

Barnett Frank, Email: bsfrank@email.unc.edu, Human Movement Science Curriculum, Department of Exercise and Sport Science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC USA.

Alex Donaldson, Email: a.donaldson@Federation.edu.au, Deputy Director, Australian Centre for Research into Injury in Sport and its Prevention (ACRISP), Federation University Australia, SMB Campus, Ballarat VIC AUS.

Sarah de la Motte, Email: sarah.delamotte@usuhs.mil, Consortium for Health and Military Performance, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD USA.

Kenneth L. Cameron, Email: kenneth.l.cameron.civ@mail.mil, John A. Feagin Jr. Sports Medicine Fellowship, Keller Army Hospital, West Point, NY USA.

Anthony I. Beutler, Email: anthony.beutler@usuhs.edu, Consortium for Health and Military Performance, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD USA.

Lindsay J. DiStefano, Email: lindsay.distefano@uconn.edu, Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT USA.

Stephen W. Marshall, Email: smarshal@unc.edu, Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC USA

References

- 1.Cameron KL, Owens BD. The burden and management of sports related musculoskeletal injuries and conditions within the United States Military. Clin Sports Med. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauret K, Taylor B, Clemmons N, et al. Frequency and causes of nonbattle injuries air evacuated from Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom, US Army, 2001–2006. Am J Prev Med. 2010;8:S94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones B, Knapik J. Physical training and exercise-related injuries. Surveillance, research and injury prevention in military populations. Sports Med. 1999;27:111–25. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finestone A, Milgrom C. How stress fracture incidence was lowered in the Israeli army: a 25-yr struggle. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:S623–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181892dc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finch C. A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullock S, Jones B, Gilchrist J, et al. Prevention of physical training-related injuries recommendations for the military and other active populations based on expedited systematic reviews. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S156–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gielen A, McDonald E, Gary T, Bone L. Using the PRECEDE-PROCEDE model to apply health behavior theories. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 407–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper H. Incidence, severity, aetiology, and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Med. 1992;14:82–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulos R, Donaldson A. Improving the diffusion of safety initiatives in community sport. J Sci Med Sport. 2014:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donaldson A, Finch C. Applying implementation science to sports injury prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:473–75. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugimoto D, Myer G, McKeon J, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: a critical review of relative risk reduction and numbers-needed-to-treat analyses. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:979–88. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson D, Allegrante J, Sleet AD, et al. Research alone is not sufficient to prevent sports injury. Br J Sports Med. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091434. Published Online First 21 July 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padua D. Executing a collaborative prospective risk-factor study: findings, successes, and challenges. J Athl Train. 2010;45:519–521. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beutler A, de la Motte S, Distefano L, et al. Can a 10-Minute Injury Prevention Program Decrease Injuries in Military Cadets? A JUMP-ACL Study. Clin J Sports Med; Abstracts from American Medical Society for Sports Medicine 22nd Annual Meeting; San Deigo. 2013; 2013. pp. 123–156. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers D, Durlak J, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50:462–80. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadoghi P, von Keudell A, Vavken P. Effectiveness of anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention training programs. Am J Bone Joint Surg. 2012;94:769–76. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaBella C, Huxford M, Grissom J, et al. Effect of neuromuscular warm-up on injuries in female soccer and basketball athletes in urban public high schools: cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:1033–40. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor J, Waxman J, Richter S, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention programme training components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092358. Published Online First 6 August 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Distefano L, Padua D, Blackburn J, et al. Integrated injury prevention program improves balance and vertical jump height in children. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:332–342. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181cc2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noyes F, Barber-Westin S, Tutalo Smith S, et al. A training program to improve neuromuscular and performance indices in female high school soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:340–51. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825423d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartholomew L, Parcel G, Kok G, Gottlieb N, Fernandez M. Planning Health Promotion Programs. 3. San Frankcisco: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klesges L, Estabrooks P, Dzewaltowski D, et al. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:S66–75. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soligard T, Nilstad A, Steffen K, et al. Compliance with a comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in youth football. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:787–793. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.070672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donaldson A, Finch C. Planning for implementation and translation: seek first to understand the end-users’ perspectives. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:306–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krist M, van Beijsterveldt A, Backx F, et al. Preventive exercises reduced injury-related costs among adult male amateur soccer players: a cluster-randomised trial. J Physiother. 2013;59:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hägglund M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, et al. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:738–42. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortington L, Donaldson A, Lathlean T, et al. When “just doing it” is not enough: assessing the fidelity of player performance of an injury prevention exercise program. J Sci Med Sport. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.05.001. Published Online First 16 May 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fixsen DL. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. Tampa: Florida Mental Health Institute; 2005. pp. 1–125. [Google Scholar]