Abstract

BACKGROUND

Nausea and vomiting in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) can be from various causes, including the use of high-dose cytarabine.

METHODS

The authors compared 2 schedules of palonosetron versus ondansetron in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients with AML receiving high-dose cytarabine. Patients were randomized to: 1) ondansetron, 8 mg intravenously (IV), followed by 24 mg continuous infusion 30 minutes before high-dose cytarabine and until 12 hours after the high-dose cytarabine infusion ended; 2) palonosetron, 0.25 mg IV 30 minutes before chemotherapy, daily from Day 1 of high-dose cytarabine up to Day 5; or 3) palonosetron, 0.25 mg IV 30 minutes before high-dose cytarabine on Days 1, 3, and 5.

RESULTS

Forty-seven patients on ondansetron and 48 patients on each of the palonosetron arms were evaluable for efficacy. Patients in the palonosetron arms achieved higher complete response rates (no emetic episodes plus no rescue medication), but the difference was not statistically significant (ondansetron, 21%; palonosetron on Days 1–5, 31%; palonosetron on Days 1, 3, and 5, 35%; P = .32). Greater than 77% of patients in each arm were free of nausea on Day 1; however, on Days 2 through 5, the proportion of patients without nausea declined similarly in all 3 groups. On Days 6 and 7, significantly more patients receiving palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 were free of nausea (P = .001 and P = .0247, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS

The daily assessments of emesis did not show significant differences between the study arms. Patients receiving palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 had significantly less severe nausea and experienced significantly less impact of CINV on daily activities on Days 6 and 7.

Keywords: nausea and vomiting, palonosetron, cytosine arabinoside, ondansetron

Cytarabine-containing regimens have been the cornerstone of the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) for the last 30 years. Nausea and vomiting in patients with hematologic malignancies can be from several causes. The use of high-dose cytarabine in combination with other agents is probably the most important causative factor. Few studies have addressed the issue of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients with hematologic malignancies.1–3 One study indicated that >70% of such patients are emesis-free during the first 24 hours of chemotherapy, but <50% of them remain emesis-free after the first 24 hours.3 Hence, there is a need to explore options to reduce late CINV (>24 hours) in patients with hematologic malignancies.

The pathophysiology of CINV is still incompletely understood. One proposed mechanism is the local or systemic release of neurotransmitters secondary to cellular injury induced by chemotherapy. The major excitatory neurotransmitters involved in emesis are 5-hydroxytriptamine (5-HT; serotonin) and dopamine.4

Palonosetron hydrochloride is a novel, potent, and selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Studies done in patients with different types of solid tumors receiving moderately or highly emetogenic multiday chemotherapy have demonstrated that palonosetron is effective in preventing CINV during the first 24 hours after chemotherapy and also provides excellent protection against delayed CINV.4–6 Extensive in vitro and in vivo pharmacological studies of palonosetron showed it has a high binding affinity and specificity for 5-HT3 receptors7 and an extended elimination half-life of approximately 40 hours. Palonosetron has been associated with low incidences of adverse events. Although the efficacy of palonosetron has been demonstrated in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy,4,8–13 its use in patients with hematologic malignancies has not yet been investigated.

Given that palonosetron has high receptor binding affinity and a prolonged half-life, we compared 2 schedules of palonosetron versus ondansetron given by continuous intravenous (IV) infusion (our standard of care) in the treatment of CINV in patients with acute leukemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Adults (>18 years old) with AML or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing induction chemotherapy or first salvage regimen with high-dose (>1.5 g/m2 up to 5 days) cytarabine-containing regimens (including but not limited to cytarabine plus idarubicin [12 g/m2 for 3 days] and cytarabine plus fludarabine [30 g/m2 for 5 days]) were eligible for this study. Exclusion criteria included emesis or nausea ≤24 hours before chemotherapy, ongoing emesis because of any organic etiology, and known hypersensitivity to ondansetron or palonosetron or to other selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists.

The protocol was approved by the institutional review board. All patients gave written informed consent before being registered in the study.

At enrollment, patients were randomized to 1 of 3 arms. In Arm 1, patients received 8 mg of ondansetron as an IV bolus over 15 minutes, followed by 24 mg of ondansetron given by continuous IV infusion starting 30 minutes before the cytarabine infusion and lasting until 12 hours after the cytarabine infusion ended. In Arm 2, patients received 0.25 mg of palonosetron as an IV bolus over 30 seconds, 30 minutes before the start of chemotherapy daily from Day 1 of cytarabine treatment up to 5 days, depending of the duration of the cytarabine infusion. In Arm 3, patients received 0.25 mg of palonosetron as an IV bolus over 30 seconds, 30 minutes before the start of chemotherapy on Days 1, 3, and 5 of cytarabine treatment.

All patients were required to stop taking antinausea drugs before the first dose of study medication. All patients received methylprednisolone 40 mg as an IV bolus before each cytarabine infusion to prevent cytarabine side effects. Because the patients in this study were already deeply immunosuppressed, no other steroid use was permitted during the study. Concomitant medications and therapies deemed necessary for supportive care were allowed. All patients received antiviral (valacyclovir 500 mg by mouth daily), antibacterial (levofloxacin 500 mg by mouth daily), and antifungal prophylaxis (voriconazole 200 mg by mouth twice per day).

Patient diaries were used to record emetic episodes, severity of nausea (none, mild, moderate, or severe), use of rescue medications, and the impact of nausea and vomiting (not at all, a little, quite a bit, or very much) on daily activities (eating and sleeping), on ability to think and reason (reading and hobbies), and on physical activities (walking).

Patients were followed for a total of 7 days, starting with the first day of chemotherapy.

Complete response was defined as no emesis episodes and no use of rescue medication during the study period (7 days). Partial response was defined as ≤1 episode of emesis during the entire 7-day study period, no use of rescue medication during the study period, and no more than moderate nausea (grade 2, National Cancer Institute [NCI] Common Toxicity Criteria) during chemotherapy. Time to treatment failure was defined as the time to first need for rescue medication or first emesis episode, whichever occurred first.

Patients were removed from the study if they developed NCI grade 4 nonhematologic toxicity related to ondansetron or palonosetron or if they asked to be removed from the study. To be included in the efficacy evaluation, patients had to have received study drug during the time on cytarabine infusion and had to have filled out the diary.

Statistics Considerations

The primary endpoint of the study is the prevention of emesis episodes and no use of rescue medication during the administration of chemotherapy (assessed as complete response). A maximum of 150 patients was planned to be recruited for the study, 50 patients in each arm. We modeled the probability of complete response using a Bayesian monitoring rule for futility. Implementation of the monitoring rules was applied only after every 15th patient was enrolled and had been evaluated for complete response, and subsequently periodic assessments were conducted.

Categorical data were tabulated by frequency and percentage; continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, range). Chi-square test, Fisher exact test, and its generalizations were used to assess the associations between categorical variables such as association of treatment and response. Logistic regression models were fit for univariate and multivariate analyses to evaluate the effects of covariates on nausea or vomiting occurrence. For the multivariate analysis, initially a full logistic model was fit, including age, sex, performance score, treatment, infection at start, use of antibiotic at start, and type of antifungal (AF) as covariates. A backward elimination procedure was then used for model selection, with variables removed 1 at a time until all the variables retained in the model were significant at the .05 level, using SAS 9 (SAS Corporation, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

From October 2005 to April 2008, 150 patients were registered in the study. One hundred forty-three patients were evaluable for efficacy: 47 patients in the ondansetron arm and 48 patients in each palonosetron arm. Seven patients were excluded from the analysis; 2 patients were transferred to the medical intensive care unit, and thus no efficacy evaluation could be done; 2 patients did not receive chemotherapy, and thus no study drug was given; 1 patient received only 1 dose of study drug, because his chemotherapy was placed on hold; 1 patient received 2 antiemetic drugs; and 1 patient had severe headache after 2 doses of study drug and decided to withdraw from the study. This last patient was included in the safety analysis.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The treatment groups were similar with respect to baseline characteristics. All 3 treatment groups were similar with respect to the type of chemotherapy administered. All patients in all 3 arms had good performance status (Zubrod score ≤2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Ondansetron; Arm 1; n = 47; No. (%) | Palonosetron | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 2; Days 1–5; n = 48; No. (%) | Arm 3; Days 1, 3, 5; n = 48; No. (%) | |||

| Sex | .53 | |||

| Women | 25 | 23 | 20 | |

| Men | 22 | 25 | 28 | |

| Race/ethnicity | .80 | |||

| Caucasian | 36 (77) | 36 (75) | 33 (69) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (15) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | |

| African American | 2 (4) | 4 (9) | 6 (13) | |

| Asian | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | |

| Median age, y [range] | 54 [23–69] | 52 [25–68] | 53 [18–72] | .87 |

| Diagnosis of AML | 46 (98) | 48 (100) | 46 (96) | .36 |

| Induction (vs salvage) chemotherapy | 47 (100) | 47 (98) | 45 (94) | .16 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | .77 | |||

| Fludarabine+cytarabine | 4 (9) | 6 (13) | 6 (13) | |

| Idarubicin+cytarabine | 43 (91) | 42 (87) | 42 (87) | |

| History of alcohol use | .50 | |||

| Never/less than weekly | 39 (83) | 34 (71) | 40 (83) | |

| Weekly | 8 (17) | 14 (29) | 8 (17) | |

| History of smoking | .35 | |||

| Never/former | 44 (94) | 44 (92) | 48 (100) | |

| Current | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 0 | |

| Presence of infection at start | 13 (28) | 11 (23) | 7 (14) | .29 |

| Systemic antibiotics at start | 32 (68) | 30 (63) | 34 (71) | .67 |

| Received prior chemotherapy | 7 (15) | 5 (10) | 7 (15) | .7716 |

AML indicates acute myelogenous leukemia.

Efficacy

Patient responses to the study drugs are shown in Table 2. Although more patients in the palonosetron arms than in the ondansetron arm achieved a complete response, this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, fewer patients in the palonosetron arms than in the ondansetron arm had treatment failure, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Responses to Antiemetic Therapy

| Response | Ondansetron; Arm 1; n = 47; No. (%) | Palonosetron | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 2; Days 1–5; n = 48; No. (%) | Arm 3; Days 1, 3, 5; n = 48; No. (%) | |||

| Response | 16 (34) | 22 (46) | 21 (44) | .46 |

| Complete response | 10 (21) | 15 (31) | 17 (35) | |

| Partial response | 6 (13) | 7 (15) | 4 (8) | |

| Failure | 31 (67) | 26 (54) | 27 (56) | .32 |

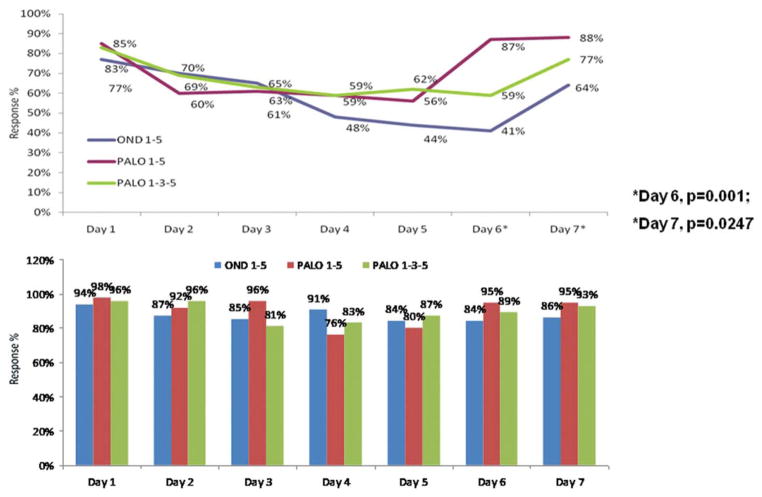

The proportions of patients without nausea on each study day are shown in Figure 1 (Top). On Day 1, >77% of the patients in each arm were free of nausea. On Days 2 through 5, the proportion of patients without nausea declined similarly in all 3 groups. On Days 6 and 7, significantly more patients receiving palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 than those receiving ondansetron were free of nausea (P = .001 and P = .0247, respectively). The daily assessments of emesis did not show significant differences between study arms in the number of patients without emesis (Fig. 1, Bottom). Similar to the nausea results, fewer patients in the palonosetron arms than in the ondansetron arm reported emesis. The falloff after Day 1 in the number of patients without emesis was less pronounced than the falloff after Day 1 in the number of patients without nausea.

Figure 1.

(Top) Proportions of patients without nausea by study day are shown. (Bottom) Proportions of patients without emesis by study day are shown. OND indicates ondansetron; PALO, palonosetron.

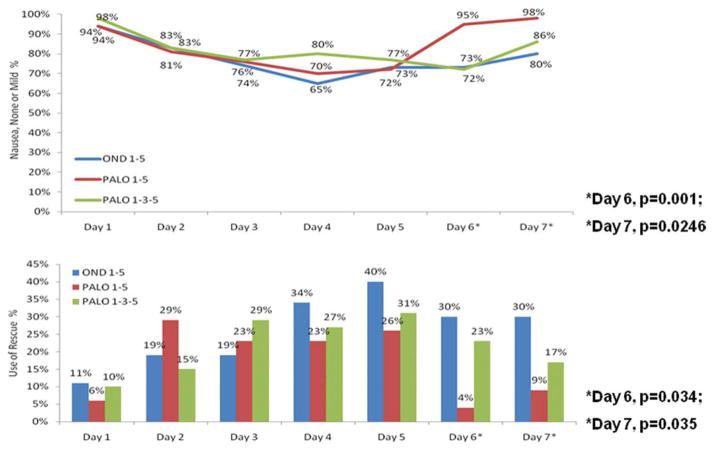

Significantly more patients in the palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 group than in the ondansetron group and in the palonosetron on Days 1, 3, and 5 group reported having no or mild nausea on Days 6 and 7 (Fig. 2, Bottom). No between-group differences in the severity of nausea were observed during Days 1 to 5.

Figure 2.

(Top) Proportions of patients with no or mild nausea by study day are shown. (Bottom) Proportions of patients who used rescue medication by study day are shown. OND indicates ondansetron; PALO, palonosetron.

Risk Factors for Nausea

Table 3 shows the variables that predicted the development of nausea. On univariate analysis, predictors of nausea included: female sex, younger age, good performance status, receiving high-dose cytarabine with idarubicin, receiving prophylactic antibiotics, and not having infection at the start of chemotherapy. In the multivariate analysis, the independent predictors were: younger age, receiving high-dose cytarabine with idarubicin, and receiving prophylactics antibiotics.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Nausea

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Younger age | 1.05 (1.001–1.09) | .02 |

| High-dose cytarabine+idarubicin | 3.27 (1.06–10.08) | .04 |

| Prophylactic antibiotic | 2.86 (1.30–6.25) | .009 |

CI indicates confidence interval.

Rescue Medication

Median time to use of rescue medication was 2 days (range, 1–7) for patients receiving ondansetron, 1 day (range, 1–7) for patients receiving palonosetron on Days 1 to 5, and 1 day (range, 1–6) for patients receiving palonosetron on Days 1, 3, and 5. Significantly fewer patients in the palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 group than in the ondansetron group and in the palonosetron on Days 1, 3, and 5 group required rescue medication on Days 6 and 7 (Fig. 2, Bottom).

Adverse Events

The most common treatment-related adverse events were constipation and headache. Twenty-two (15%) patients reported NCI grade 1 to 3 adverse events possibly or probably related to ondansetron or palonosetron. Three patients, 1 in each arm, developed NCI grade 3 adverse events. One patient in the ondansetron arm and 1 in the palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 arm reported grade 3 headache, and 1 patient in the palonosetron on Days 1, 3, and 5 arm had grade 3 diarrhea. No cardiac adverse events considered possibly or probably related to ondansetron or palonosetron were reported.

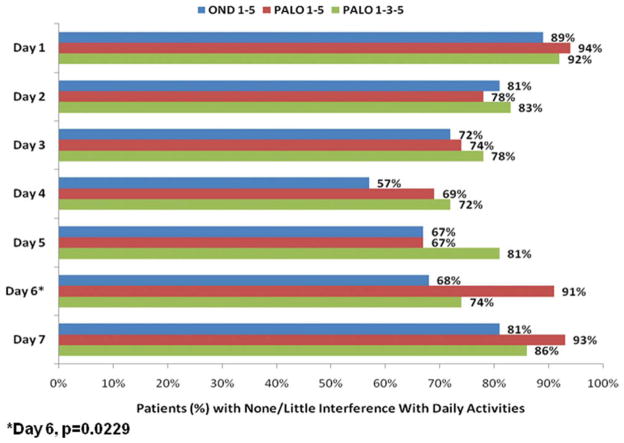

Impact of CINV on Daily Activities

Patients recorded the impact of CINV on daily activities in a diary during the study period. No differences were found among the 3 groups, except on Day 6, when significantly more patients who received palonosetron on Days 1 to 5 reported a minimal effect of CINV on their activities (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Proportions are shown of patients with little or no impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on daily activities, by study day. OND indicates ondansetron; PALO, palonosetron.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first prospective randomized trial of medications for the prevention of CINV in patients with AML or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Palonosetron given daily from Day 1 up to Day 5 of chemotherapy significantly reduced the incidence of nausea on Days 6 and 7. In addition, patients receiving that regimen had significantly less severe nausea on Days 6 and 7 and experienced significantly less impact of CINV on daily activities than patients receiving the other 2 regimens.

Although CINV is frequent in patients with hematologic malignancies, the extent of the problem and options to reduce CINV have received little attention. A search of the English literature in PubMed using the search terms “emesis treatment” and “acute leukemia” returned only 2 publications.1,2 Braken and colleagues1 published a small trial of 18 patients with AML who received 8 mg of ondansetron as an IV loading dose 30 minutes before the start of chemotherapy, followed by 2 tablets of 8 mg of ondansetron on Day 1. On Days 2 to 10, patients received 3 tablets of 8 mg of ondansetron each day. During the first cycle, the complete response rate (patients without vomiting) was 50%, and the partial response rate (patients with no more than 1–5 episodes of vomiting in 10 days) was 28%, for an overall response rate of 78%. The overall response rates in patients who received subsequent cycles of chemotherapy were 72% in the second cycle and 80% in the third cycle.

The second study was published by Musso and colleagues.2 In their prospective study, 46 patients with different malignancies (23 with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 8 with Hodgkin disease, 14 with AML, and 1 with solid tumor) received palonosetron 0.25 mg by IV infusion and dexamethasone 8 mg by IV infusion 15 minutes before starting chemotherapy. The rate of CINV in these patients was compared with the rate of CINV in a historical group of patients with similar characteristics who received ondansetron (8 mg by IV infusion) and dexamethasone (8 mg by IV infusion) before starting chemotherapy. The results of this trial demonstrated that 80% of the patients receiving palonosetron did not develop CINV, compared with 60% of patients in the historical control group who received ondansetron (P = .04).

In our study, the overall response rates with palonosetron (31% and 35%) were lower than the response rates in the studies by Braken et al and Musso et al1,2 and also lower than the response rates in studies of palonosetron in patients with other types of cancer.9,10,13,14 The differences in response rates may be because of differences in the type of underlying disease, or in the chemotherapy given and its risk for emesis. Patients with AML have unique characteristics specific to the treatment of leukemia that may affect the incidence of CINV and the efficacy of antiemetic therapy. These include the specific dietary restrictions common for leukemia patients; the use of prophylactic antibiotic, antifungal, and antiviral agents in all patients with leukemia; the frequent need for IV administration of antibiotics or antifungals, usually in multidrug combinations, during the course of treatment for leukemia; and psychological issues (eg, issues because of isolation in laminar airflow rooms). Also, cytarabine and many of the agents that are given together with cytarabine are standard agents for AML but are seldom used in chemotherapy combinations for solid tumors. Thus, comparisons of palonosetron for AML versus palonosetron for solid tumors will be subject to effects of different underlying diseases and of different chemotherapies.

In the study by Musso et al, only 14 of the 46 patients had AML, and only 7 patients received a high-dose cytarabine-containing regimen. Similarly, 14 of the 18 patients reported by Braken et al were given a standard dose of cytarabine (200 mg/m2). Cytarabine at a dose of ≤1000 mg/m2 carries a low risk of emesis (incidence of emesis without antiemetics, 10%–30%). All of our patients were treated with high-dose cytarabine (>1.5 mg/m2) and either fludarabine or idarubicin. Cytarabine and idarubicin carry a risk of emesis without antiemetics of 30% to 90%.

The impact of the unique features of patients with leukemia is demonstrated by the results of the univariate and multivariate analysis reported in our study. Younger patients, patients who received cytarabine in combination with idarubicin, and patients who received prophylactic antibiotics were at higher risk for nausea. Importantly, receipt of cytarabine plus idarubicin was the most important risk factor (odds ratio, 3.27; P = .04). This is the first time that an antileukemic regimen has been described as a significant factor associated with nausea.

Although all 3 antiemetic regimens tested offered effective protection against nausea during the first 24 hours after initiation of chemotherapy, the proportion of patients free of nausea during Days 2 to 5 was markedly lower in all 3 study arms, and the severity of nausea was higher. Similar results have been reported in studies done in children with acute lymphocytic leukemia.3,15 A possible explanation for these results is that the emetogenic effect of the 2 chemotherapy agents overlaps during these days. During Days 2 to 5, a different type of antiemetic, other than a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist, may need to be added. In relation to this, the combination of aprepitant (a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist) and a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist has been shown to have an improved antiemetic effect in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy for different types of cancer.16,17 Although patients with hematologic malignancies were not included in these studies, the combination of aprepitant and a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist is an attractive option that should be considered in patients with leukemia.

The results of our study confirm previous reports on the superiority of palonosetron over the first generation 5HT-3 receptor antagonists in reducing the incidence of delayed nausea. This is, however, the first study that demonstrates this effect in patients with leukemia.

With respect to daily activities, our results show that patients randomized to either of the palonosetron regimens reported less interference with daily activities than did patients in the ondansetron arm on each study day. However, the difference was significant only on Day 6.

Palonosetron was well tolerated. The incidences of headache and constipation, the most frequent adverse events in both palonosetron arms, were similar to those in previous reports.6,9

In conclusion, palonosetron given daily for 4 or 5 days significantly reduced the incidence and severity of nausea on Days 6 and 7 in patients with AML receiving multiple-day chemotherapy with a high-dose cytarabine-containing regimen. Patients receiving that regimen experienced significantly less impact of CINV on daily activities on Day 6. Our findings indicate that although 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonists have high efficacy against CINV during the first 24 hours of chemotherapy, this protection is less effective on Days 2 to 5, because >40% of patients develop nausea during that period. It will be important to investigate whether combinations of different classes of antiemetics will result in better protection during these days.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Research Support: GI Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Braken JB, Raemaekers JM, Koopmans PP, de Pauw BE. Control of nausea and vomiting with ondansetron in patients treated with intensive non-cisplatin chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukaemia. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:515–518. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musso M, Scalone R, Bonanno V, et al. Palonosetron (Aloxi) and dexamethasone for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting in patients receiving multiple-day chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:205–209. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Jimenez J, Martin-Ballesteros E, Sureda A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in acute leukemia and stem cell transplant patients: results of a multicenter, observational study. Haematologica. 2006;91:84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg P, Figueroa-Vadillo J, Zamora R, et al. Improved prevention of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with palonosetron, a pharmacologically novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist: results of a phase III, single-dose trial versus dolasetron. Cancer. 2003;98:2473–2482. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aapro MS, Grunberg SM, Manikhas GM, et al. A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1441–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, et al. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1570–1577. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong EH, Clark R, Leung E, et al. The interaction of RS 25259–197, a potent and selective antagonist, with 5-HT3 receptors, in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aloxi [package insert] Woodcliff Lake, NJ: Eisai; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg P, MacKintosh FR, Ritch P, Cornett PA, Macciocchi A. Efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of palonosetron in patients receiving highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a dose-ranging clinical study. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:330–337. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gralla RJ, Osoba D, Kris MG, et al. Recommendations for the use of antiemetics: evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2971–2994. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navari RM. Pathogenesis-based treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting—2 new agents. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoltz R, Cyong JC, Shah A, Parisi S. Pharmacokinetic and safety evaluation of palonosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist, in U.S. and Japanese healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:520–531. doi: 10.1177/0091270004264641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, et al. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massa E, Astara G, Madeddu C, et al. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone effectively prevents acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy in pre-treated patients who have failed to respond to a previous antiemetic treatment: comparison between elderly and non-elderly patient response. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komada Y, Matsuyama T, Takao A, et al. A randomised dose-comparison trial of granisetron in preventing emesis in children with leukaemia receiving emetogenic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrstedt J, Muss HB, Warr DG, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis over multiple cycles of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;104:1548–1555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrington JD, Jaskiewicz AD, Song J. Randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study evaluating aprepitant single dose plus palonosetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer. 2008;112:2080–2087. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]