Abstract

BACKGROUND

Dasatinib, a highly potent BCR-ABL inhibitor, is an effective treatment for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML CP) after resistance, suboptimal response, or intolerance to prior imatinib. In a phase 3 dose optimization trial in patients with CML CP (CA180-034), the occurrence of pleural effusion was significantly minimized with dasatinib 100 mg once daily (QD) compared with other treatment arms (70 mg twice daily [twice daily], 140 mg QD, or 50 mg twice daily).

METHODS

To investigate the occurrence and management of pleural effusion during dasatinib treatment, and efficacy in patients with or without pleural effusion, data from CA180-034 were analyzed.

RESULTS

With 24-month minimum follow-up, 14% of patients treated with dasatinib 100 mg QD incurred pleural effusion (grade 3: 2%; grade 4: 0%) compared with 23% to 26% in other study arms. The pleural effusion rate showed only a minimal increment from 12 to 24 months. In the 100 mg QD study arm, median time to pleural effusion (any grade) was 315 days, and after pleural effusion, 52% of patients had a transient dose interruption, 35% had a dose reduction, 57% received a diuretic, and 26% received a corticosteroid. Three patients in the 100 mg QD study arm discontinued treatment after pleural effusion. Across all study arms, patients with or without pleural effusion demonstrated similar progression-free and overall survival, and cytogenetic response rates were higher in patients with a pleural effusion.

CONCLUSIONS

Pleural effusion is minimized with dasatinib 100 mg QD dosing and its occurrence does not affect short- or long-term efficacy.

Keywords: Dasatinib, chronic myeloid leukemia, pleural effusion, treatment outcome, progression-free survival, lymphocytosis

Dasatinib (Sprycel, Bristol-Myers Squibb, NY) is a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor that has 325-fold higher in vitro potency than imatinib against unmutated BCR-ABL.1 Dasatinib also inhibits platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β, SRC, and c-KIT. In patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph + ALL), who have developed resistance, suboptimal response, or intolerance to prior imatinib, dasatinib induces high rates of hematologic, cytogenetic, and molecular responses, and minimal cross intolerance to imatinib has been observed.2–6 In CA180-034, a phase 3 dasatinib dose-optimization trial in patients with chronic phase (CP) CML, dasatinib 100 mg once daily (QD) significantly minimized the occurrence of key adverse events, including pleural effusion, while maintaining efficacy.6

The aim of the current report was to analyze 24-month data from the CA180-034 trial with specific reference to the dynamics of pleural effusion, how investigators managed pleural effusion, and the efficacy of dasatinib in patients with or without pleural effusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The design and methodology of the dasatinib CA180-034 trial has been reported previously.6 Briefly, CA180-034 is a phase 3 dose optimization study in patients with CML CP after resistance, suboptimal response, or intolerance to imatinib. Patients were randomized using a 2 × 2 factorial design to dasatinib administered at 1 of 4 dose schedules: 100 mg QD, 70 mg twice daily, 140 mg QD, or 50 mg twice daily, with dose interruption/reduction or escalation allowed for the management of toxicity or inadequate response. Patients were treated until disease progression or excessive toxicity, as determined by the treating physician, and all patients were followed for survival status irrespective of drug discontinuation or disease progression. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee at each participating center. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Definition of Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion was graded according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (AEs) Version 3.0 as follows: grade 1, asymptomatic; grade 2, symptomatic, with any intervention such as diuretics or up to 2 therapeutic thoracenteses indicated; grade 3, symptomatic and supplemental oxygen, more than 2 therapeutic thoracenteses, tube drainage, or pleurodesis indicated; and grade 4, life-threatening (eg, causing hemodynamic instability or ventilatory support indicated). In all patients, chest x-ray was performed at the discretion of the investigator and at protocol-stipulated intervals (baseline, after 12 weeks and after 6 months) to detect asymptomatic pleural effusion.

In this analysis, any patient who incurred pleural effusion at any time was included in the pleural effusion group, irrespective of whether the event was classified by the investigator as drug related. Because of statistical considerations, data were analyzed based on the first reported instance of pleural effusion in each patient. Because protocol-specified assessments and case report forms did not collect data on pleural effusion duration, resolution, or recurrence, these could not be analyzed.

Pleural Effusion Management

In the study protocol, recommendations for managing nonhematologic grade ≥ 2 AEs, including pleural effusion, were as follows: after grade 2 AE, dasatinib was interrupted until the AE resolved (to grade ≤ 1, as determined by individual investigators), and then restarted at the original dose; after recurrence of same grade 2 AE, dasatinib was interrupted and restarted at a reduced dose (80 mg QD in the 100 mg QD study arm); after second recurrence of the same grade 2 AE, dasatinib discontinuation could have been considered by the investigator according to the best interests of the patient (140 mg QD and 70 mg twice daily study arms were permitted a second dose reduction); after grade 3 AE, dasatinib was interrupted until the AE resolved, and then restarted at a reduced dose; after recurrence of same grade 3 AE, dasatinib discontinuation could have been considered (or a second dose reduction could have been performed, if permitted); after grade 4 AE, patients did not generally receive additional dasatinib therapy, unless considered by the investigator to be in the best interests of the patient.

Administration of additional treatments for pleural effusion was at the discretion of individual investigators. To investigate diuretics or corticosteroids potentially used to manage pleural effusion, lists of concomitantly administered medications were searched using terms comprising 26 different diuretics and 15 different corticosteroids. All diuretic or corticosteroid agents administered at the time of pleural effusion were assumed to have been used in pleural effusion management.

The use of thoracentesis at the time of pleural effusion was also assessed. Thoracentesis was performed at the discretion of investigators. Reporting of thoracentesis procedures occurred separately from AE grading and did not routinely indicate whether thoracentesis was performed for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes or both. Results of diagnostic thoracenteses were not collected as part of the study protocol.

Response Assessment

Efficacy was evaluated using standard hematologic and bone marrow cytogenetic assessments to determine rates of complete hematologic response (CHR), major cytogenetic response, and complete cytogenetic response, as previously described.7

Lymphocytosis

For the purposes of this analysis, lymphocytosis during dasatinib treatment was defined as an absolute blood lymphocyte count greater than 3.6 × 109/L on at least 2 occasions after more than 4 weeks of dasatinib therapy. Complete blood counts were performed at baseline and at regular intervals (every 2 weeks for the first 12 weeks and every 3 months thereafter). For this analysis, elevated lymphocyte counts within the first 4 weeks of dasatinib therapy were not included in the determination of lymphocytosis. Mean lymphocyte counts in groups of patients were calculated from mean values for all absolute lymphocyte counts determined after the first 4 weeks of dasatinib therapy in each patient.

Statistical Analysis

Duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival, and treatment without pleural effusion were estimated using Kaplan-Meier product-limit methodology, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. Progression was defined as increasing white blood cell count, loss of CHR or major cytogenetic response, ≥ 30% increase in Ph + metaphases, confirmed accelerated or blast phase, or death. For duration of response and PFS analysis, patients who neither progressed/lost response nor died were censored at last cytogenetic or hematologic assessment before loss of follow-up, and patients were not followed after study drug discontinuation for protocol-stipulated reasons, including withdrawal of informed consent, any adverse event, laboratory abnormality, or intercurrent illness (which, in the investigator’s opinion, indicated that continued treatment was not in the patient’s best interest), pregnancy, and stem-cell transplantation (SCT). For overall survival analysis, patients who did not die or were lost to follow-up were censored on last known alive date regardless of whether or not they discontinued study drug. For analysis of treatment without pleural effusion, patients who did not incur pleural effusion were censored if dasatinib treatment ended for any reason.

Fisher exact test was used to compare the rates of pleural effusion across treatment arms. Pearson chi-square test was used to examine a possible association between the occurrence of pleural effusion and lymphocytosis or cytogenetic response; because these analyses were not pre-specified or controlled, interpretation of significance is not possible and the P value is provided for descriptive purposes only.

Risk Factor Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics and lymphocytosis during dasatinib therapy were investigated as potential risk factors for pleural effusion. Odds ratios and their 95% CIs were calculated using logistic regression. The probability of pleural effusion was regressed as a single covariate. Continuous variables were split into categories (age) or quartiles (time from initial diagnosis). Data on comorbidities (eg, prior cardiac history, pulmonary disease, or fluid retention toxicity on imatinib) were not routinely or uniformly collected as part of the study protocol and could not, therefore, be included in the risk factor analysis. In addition, multivariate logistic regression, modeling the probability of achieving a cytogenetic response (major cytogenetic response and complete cytogenetic response) with baseline patient characteristics and the occurrence of lymphocytosis and pleural effusion on study, was performed. Patients who were not evaluated for any of the specified covariates were excluded from the regression. Because of the large number of P values generated, and because no correction for multiple testing was performed, P values are provided for descriptive purposes only.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

Patient demographics and disease characteristics in the CA180-034 trial have been presented previously.6 In total, 662 patients were treated with dasatinib (100 mg QD, n = 165; 70 mg twice daily, n = 167; 140 mg QD, n = 163; 50 mg twice daily, n = 167). Median patient age was 55 years (range 18–84) and patients had received prior imatinib therapy for a median duration of approximately 3 years. In all study arms, median duration of dasatinib treatment was 22 months. The minimum follow-up for this analysis was 24 months (last patient first visit to database lock).

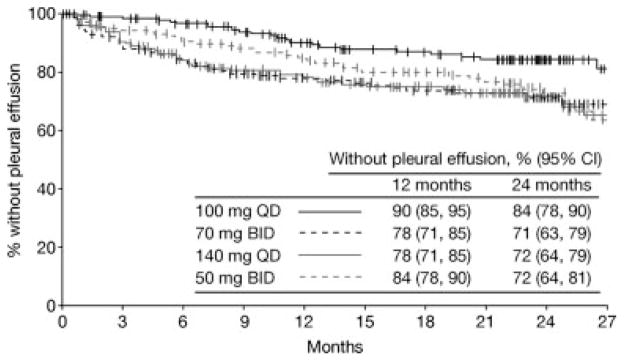

Dose Schedule and Pleural Effusion

Across all treatment arms combined, pleural effusion of any grade was reported in 22% of patients. In the 100 mg QD study arm, the overall rate of pleural effusion after at least 24 months of follow-up was 14% (grade 3: 2%; grade 4: 0%). After at least 12 months of follow-up, 10% had incurred pleural effusion (grade 3: 2%; grade 4: 0%), suggesting a minimal increment between 12 and 24 months. Overall 24-month rates of pleural effusion in the other study arms were 23%–26% (P = .021 for the comparison across all 4 study arms) (Table 1). Across all treatment arms combined, median time to pleural effusion (any grade) was 183 days. In the 100 mg QD study arm, median time to pleural effusion was 315 days, compared with 136, 148, and 289 days for 70 mg twice daily, 140 mg QD, and 50 mg twice daily study arms, respectively. Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis, at 12 and 24 months, 10% and 16% of patients in the 100 mg QD study arm had incurred pleural effusion of any grade, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Occurrence of Pleural Effusion

| 100 mg QD n = 165 | 70 mg BID n = 167 | 140 mg QD n = 163 | 50 mg BID n = 167 | All patients N = 662 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 56 (20–78) | 54 (18–83) | 54 (20–84) | 55 (21–84) | 55 (18–84) |

| Median duration of CML prior to randomization, months (range) | 55 (2–251) | 52 (1–246) | 56 (1–227) | 52 (4–212) | 54 (1–251) |

| Dasatinib treatment duration, median months (range) | 22 (1–30) | 22 (<1 to 31) | 22 (<1 to 30) | 22 (<1 to 30) | 22 (<1 to 31) |

| Patients with pleural effusion (worst grade incurred), n (%) | |||||

| Any grade | 23 (14) | 42 (25) | 43 (26) | 39 (23) | 147 (22) |

| Grade 1 | 2 (1) | 7 (4)a | 8 (5) | 6 (4) | 23 (3)a |

| Grade 2 | 17 (10) | 25 (15) | 27 (17) | 27 (16) | 96 (15) |

| Grade 3 | 4 (2) | 8 (5) | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 24 (4) |

| Grade 4 | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Time to first pleural effusion, median days (range) | |||||

| Any grade | 315 (19–805) | 135.5 (1–881) | 148 (4–785) | 289 (12–798) | 183 (1–881) |

| Grade 1 | 282 (88–322) | 171 (1–753) | 85 (12–603) | 299.5 (36–613) | 173 (1–753) |

| Grade 2 | 338 (19–805) | 87 (20–881) | 161 (4–785) | 289.0 (12–798) | 201 (4–881) |

| Grade 3 | 315 (266–503) | 339.5 (39–696) | 246.5 (69–738) | 172.5 (16–370) | 289 (16–738) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | 53 (13–93) | - | 53 (13–93) |

QD indicates once daily; BID, twice daily; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia.

The investigator reported that 1 patient with a grade 1 pleural effusion had a thoracentesis, probably with diagnostic intent.

Figure 1.

Depicted is the Kaplan-Meier analysis of duration of dasatinib treatment until pleural effusion (any grade). Patients were censored at the end of dasatinib treatment. BID indicates twice daily; QD, once daily.

Management of Pleural Effusion

Transient dose interruption after pleural effusion was performed in 12 patients in the 100 mg QD study arm (representing 7% of all 165 patients in this study arm and 52% of the 23 patients who incurred a pleural effusion), compared with 22–25 patients in other study arms (13%–15% of all patients in each study arm and 56%–60% of patients who incurred a pleural effusion) (Table 2). Dose reduction after pleural effusion occurred in 8 patients in the 100 mg QD study arm (5% of all patients, 35% of patients who incurred a pleural effusion), compared with 13–16 patients in other study arms (8%–10% of all patients, 30%–38% of those who incurred a pleural effusion).

Table 2.

Management of Pleural Effusion During the CA180-034 Trial

| 100 mg QD | 70 mg BID | 140 mg QD | 50 mg BID | All patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with pleural effusion, n | 23 | 42 | 43 | 39 | 147 |

| Dose interruption, no. (%) | 12/23 (52) | 25/42 (60) | 24/43 (56) | 22/39 (56) | 83/147 (56) |

| Dose reduction, no. (%) | 8/23 (35) | 16/42 (38) | 13/43 (30) | 14/39 (36) | 51/147 (35) |

| Received diuretic, no. (%) | |||||

| Any grade | 13/23 (57) | 19/42 (45) | 17/43 (40) | 20/39 (51) | 69/147 (47) |

| Grade 1 | 0/3 (0) | 2/13 (15) | 2/10 (20) | 1/6 (17) | 5/32 (16) |

| Grade 2 | 12/17 (71) | 16/25 (64) | 13/27 (48) | 17/27 (63) | 58/96 (60) |

| Grade 3 | 1/3 (33) | 1/4 (25) | 2/4 (50) | 2/6 (33) | 6/17 (35) |

| Grade 4 | – | – | 0/2 (0) | – | 0/2 (0) |

| Received corticosteroid, no. (%) | |||||

| Any grade | 6/23 (26) | 9/42 (21) | 8/43 (19) | 9/39 (23) | 32/147 (22) |

| Grade 1 | 1/3 (33) | 3/13 (23) | 4/10 (40) | 1/6 (17) | 9/32 (28) |

| Grade 2 | 4/17 (24) | 5/25 (20) | 3/27 (11) | 5/27 (19) | 17/96 (18) |

| Grade 3 | 1/3 (33) | 1/4 (25) | 1/4 (25) | 3/6 (50) | 6/17 (35) |

| Grade 4 | – | – | 0/2 (0) | – | 0/2 (0) |

QD indicates once daily; BID, twice daily.

Among patients in the 100 mg QD study arm, additional therapies at the time of pleural effusion included diuretics in 13 patients (representing 8% of all patients in this study arm and 57% of those who incurred a pleural effusion) and corticosteroids in 6 patients (4% of all patients, 26% of patients who incurred a pleural effusion). In the other treatment arms, 17–20 patients received a diuretic (10%–12% of all patients in each study arm, 40%–51% of those who incurred a pleural effusion) and 8–9 patients received a corticosteroid (5% of all patients in each study arm, 19%–23% of those who incurred a pleural effusion).

Across all treatment arms, 12 patients had a diagnostic or therapeutic thoracentesis at the time of pleural effusion. One patient was reported by the investigator as having received a thoracentesis after a grade 1 pleural effusion, probably with diagnostic intent. In addition, a thoracentesis was performed in 5 patients after grade 2 pleural effusion and 6 patients after grade 3. Three of the 12 patients had 2 thoracenteses (50 mg twice daily, n = 1; 70 mg twice daily, n = 2). Pleural effusion was stated as the reason for treatment discontinuation for 3 patients (2%) in the 100 mg QD study arm, compared with 7 to 9 patients (4%–5%) in other study arms.

Lymphocytosis

In the total study group, lymphocytosis was detected in 37% patients with a pleural effusion and 26% patients without a pleural effusion (Table 3). Among assessed patients who developed lymphocytosis, 29% incurred a pleural effusion, compared with 20% of those who did not develop lymphocytosis. A chi-square test suggested a possible association between the occurrence of lymphocytosis and pleural effusion (P = .0082). Mean average lymphocyte counts in assessed patients with or without a pleural effusion were 2.82 × 109/L and 2.05 × 109/L, respectively.

Table 3.

Occurrence of Lymphocytosis and Pleural Effusion in Patients Treated With Any Dose of Dasatinib During the CA180-034 trial (P = 0.0082 for 2 × 2 Comparison)

| No Pleural Effusion (n) | Pleural Effusion (n) | Total No. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytosis | 132 | 54 | 186 |

| 71% of lymphocytosis group | 29% of lymphocytosis group | ||

| 26% of no pleural effusion group | 37% of pleural effusion group | ||

| No lymphocytosis | 371 | 91 | 462 |

| 80% of no lymphocytosis group | 20% of no lymphocytosis group | ||

| 72% of no pleural effusion group | 62% of pleural effusion group | ||

| Not assessed | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Total no. | 515 | 147 | 662 |

Risk Factors for Pleural Effusion

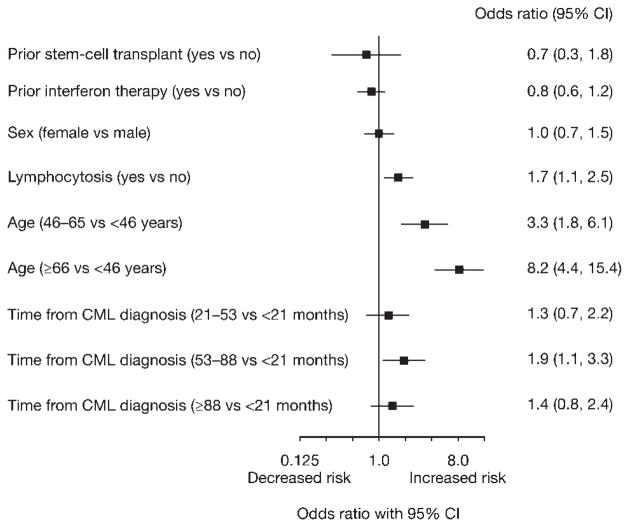

The following patient baseline characteristics were assessed as potential risk factors for pleural effusion: age, sex, duration of CML before dasatinib treatment, and prior SCT. Of baseline factors, older age was the only characteristic associated with an increased risk of pleural effusion (Fig. 2, Table 4). The development of lymphocytosis during dasatinib treatment was associated with a 1.7-fold increased risk of pleural effusion (95% CI, 1.1 to 2.5).

Figure 2.

Analysis of baseline patient characteristics and lymphocytosis during treatment as risk factors for pleural effusion is shown.

Table 4.

Occurrence of Pleural Effusion by Age Group

| Age, y | Total No. | Pleural Effusion (Any Grade), No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| <30 | 44 | 3 (7) |

| 30–39 | 79 | 2 (3) |

| 40–49 | 123 | 17 (14) |

| 50–59 | 160 | 32 (20) |

| 60–69 | 160 | 47 (29) |

| ≥ 70 | 96 | 46 (48) |

Hematologic and Cytogenetic Responses

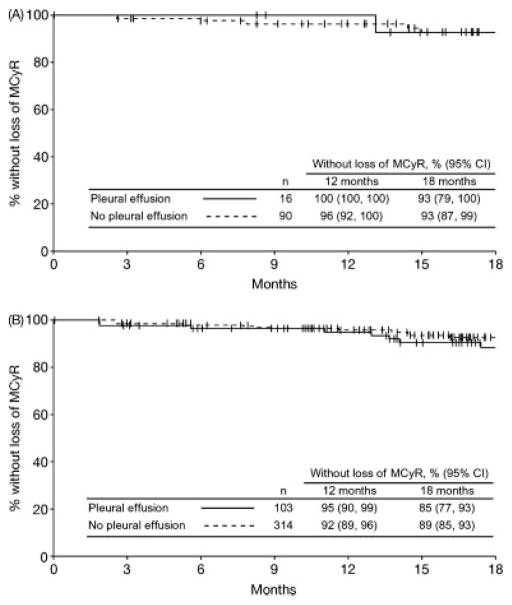

Pleural effusion did not interfere with achieving or maintaining a treatment response to dasatinib. The CHR rate was 91% in both patients with or without pleural effusion (Table 5). In the 100 mg QD study arm, CHR rates in patients with or without a pleural effusion were 96% and 92%, respectively. The overall major cytogenetic response rate for patients with a pleural effusion was 70% compared with 61% for those without (P = .044), and rates in the 100 mg QD study arm were 70% and 63% (P = .57), respectively. Among all patients across all 4 study arms who achieved a major cytogenetic response, this level of response was maintained at 18 months by an estimated 85% of patients with and 89% of patients without a pleural effusion (Fig. 3). In the 100 mg QD study arm, major cytogenetic responses were maintained at 18 months by 93% of patients with or without a pleural effusion. Overall complete cytogenetic response rates in patients with or without a pleural effusion were 61% and 49% (P = .013), with the same rates observed in the 100 mg QD study arm (P = .27). Among all patients across all 4 treatment arms who achieved a complete cytogenetic response, this level of response was maintained at 18 months by 88% with a pleural effusion and 92% of patients without a pleural effusion. With 100 mg QD treatment, 93% of patients with a pleural effusion and 95% of patients without a pleural effusion had maintained their complete cytogenetic response at 18 months. In patients who incurred pleural effusion, hematologic and cytogenetic responses were initially achieved not only before but also after the pleural effusion event (Table 6).

Table 5.

Hematologic and Cytogenetic Response Rates in Patients With or Without Pleural Effusion

| Patients, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 mg QD n = 165 | 70 mg BID n = 167 | 140 mg QD n = 163 | 50 mg BID n = 167 | All Patients N = 662 | |

| CHR | |||||

| All patients | 152 (92) | 148 (89) | 145 (89) | 156 (93) | 601 (91) |

| Pleural effusion | 22 (96) | 38 (90) | 36 (84) | 38 (97) | 134 (91) |

| No pleural effusion | 130 (92) | 110 (88) | 109 (91) | 118 (92) | 467 (91) |

| Major cytogenetic response | |||||

| All patients | 106 (64) | 103 (62) | 105 (64) | 103 (62) | 417 (63) |

| Pleural effusion | 16 (70) | 27 (64) | 32 (74) | 28 (72) | 103 (70) |

| No pleural effusion | 90 (63) | 76 (61) | 73 (61) | 75 (59) | 314 (61) |

| Complete cytogenetic response | |||||

| All patients | 83 (50) | 90 (54) | 84 (52) | 84 (50) | 341 (52) |

| Pleural effusion | 14 (61) | 24 (57) | 26 (60) | 25 (64) | 89 (61) |

| No pleural effusion | 69 (49) | 66 (53) | 58 (48) | 59 (46) | 252 (49) |

QD indicates once daily; BID, twice daily; CHR, complete hematologic response.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of duration of major cytogenetic response (major cytogenetic response) in patients with or without pleural effusion is illustrated. (A) Dasatinib 100 mg once-daily arm. (B) All treated patients.

Table 6.

Dasatinib Treatment Responses in Patients Who Incurred Pleural Effusion of Any Grade: Achievement of Initial Response Before or After Pleural Effusion

| 100 mg Once Daily (n = 23) | All Arms (N = 147) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Before | No. After | Total No. (%) | No. Before | No. After | Total No. (%) | |

| CHR | 22 | 0 | 22 (96) | 122 | 12 | 134 (91) |

| Major cytogenetic response | 14 | 2 | 16 (70) | 67 | 36 | 103 (70) |

| Complete cytogenetic response | 12 | 2 | 14 (61) | 55 | 34 | 89 (61) |

CHR indicates complete hematologic response.

A multivariate analysis was performed of selected patient characteristics at baseline (age, time from initial CML diagnosis, imatinib status [resistant/suboptimal response or intolerant], major cytogenetic response on prior imatinib, baseline level of Ph + cells or blast cells in bone marrow, baseline level of white blood cells or basophils) and the occurrence of pleural effusion and lymphocytosis, and their association with major cytogenetic response or complete cytogenetic response on dasatinib therapy (Table 7). Patients receiving any dasatinib dose were included in the analysis. In addition to other variables, pleural effusion was associated with an increased probability of achieving a major cytogenetic response (P = .0039) and complete cytogenetic response (P = .0027). After adjusting for other variables analyzed, the odds ratio for response in patients with a pleural effusion compared with those without was 2.1 (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.5) for both major cytogenetic response and complete cytogenetic response, indicating that pleural effusion may be associated with an increased likelihood of response to dasatinib.

Table 7.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Association of Baseline Patient Characteristics, or the Occurrence of Pleural Effusion or Lymphocytosis, With Achieving a Major or Complete Cytogenetic Response on Dasatinib Therapy (n = 621)

| P | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Major Cytogenetic Response | Complete Cytogenetic Response |

| Age | <.0001 | .0003 |

| White blood cells at baseline | .1511 | .1806 |

| Basophils at baseline | .6866 | .3427 |

| Blast cells in bone marrow at baseline | .3868 | .3857 |

| % Ph-positive cells in bone marrow at baseline | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Imatinib status (resistant or intolerant) | .0224 | .0003 |

| Major cytogenetic response on prior imatinib | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Time from initial diagnosis to first dasatinib dose | .0011 | .0001 |

| Lymphocytosis on dasatinib | .0006 | .0995 |

| Pleural effusion on dasatinib | .0039 | .0027 |

PFS and Overall Survival

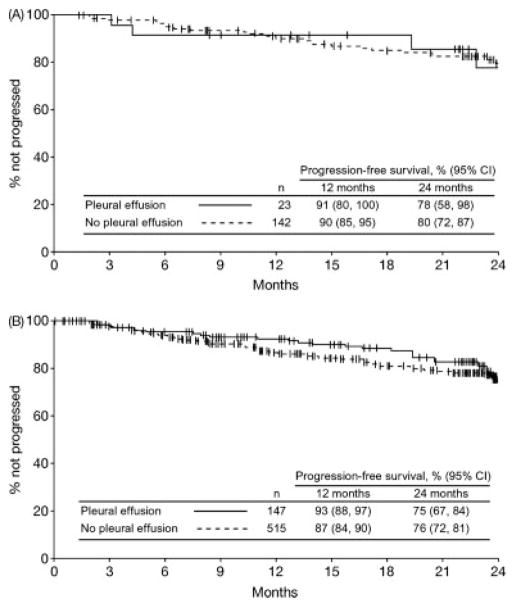

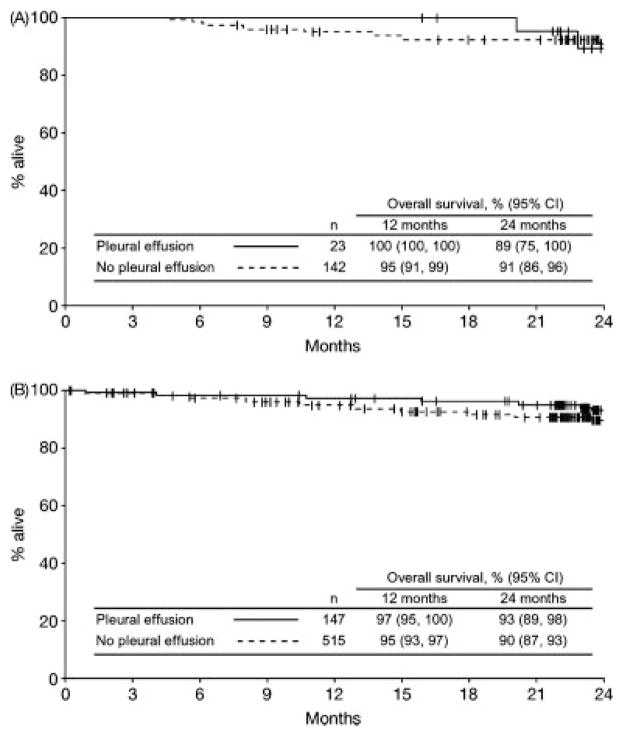

PFS and overall survival were similar in patients with or without a pleural effusion. The 24-month PFS rate for patients with a pleural effusion was 75% compared with 76% for those without (Fig. 4). In the dasatinib 100 mg QD study arm, corresponding PFS rates were 78% and 80%, respectively. Overall survival rates at 24 months for patients with or without a pleural effusion were 93% and 90%, respectively, in the total group and 89% and 91%, respectively, in the 100 mg QD study arm (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival in patients with or without pleural effusion is depicted. (A) Dasatinib 100 mg once-daily arm. (B) All treated patients.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in patients with or without pleural effusion is shown. (A) Dasatinib 100 mg once-daily arm. (B) All treated patients.

DISCUSSION

The results of this analysis demonstrate that the currently approved dasatinib dose in CML CP of 100 mg QD significantly minimizes the occurrence of pleural effusion. With minimum follow-up of 24 months, 14% of patients who received dasatinib 100 mg QD incurred pleural effusion compared with 23% to 26% in other study arms. In addition, only 2% of patients treated with dasatinib 100 mg QD experienced a grade 3 pleural effusion, with no grade 4 events reported, whereas grade 3 of 4 pleural effusion rates were 4% to 6% in other study arms. Rates at 24 months showed only a minimal increment compared with 12-month follow-up. Dasatinib 100 mg QD was also associated with the longest time to onset (median 315 days vs 136–289 days in other study arms). The lower occurrence and longer time to onset of pleural effusion observed with 100 mg QD treatment could be a result of either reduced occurrence or delayed onset (or both), and longer follow-up is required.

Importantly, rates of CHR, major cytogenetic response, and complete cytogenetic response, and durability of responses, PFS, and overall survival in patients with pleural effusion were similar or higher than in patients without pleural effusion. All 4 dasatinib treatment arms displayed comparable efficacy. Some patients achieved CHR, major cytogenetic response, or complete cytogenetic response on dasatinib after pleural effusion had occurred, demonstrating that the occurrence of pleural effusion, although sometimes associated with treatment interruption and dose reduction, did not prevent achievement of a treatment response.

In the 034 trial, management of pleural effusion was broadly similar across all treatment arms. Approximately half of patients with a pleural effusion underwent transient dose interruption and approximately one-third underwent dose reduction. In addition, more patients with a pleural effusion received diuretics than corticosteroids (approximately 50% vs 25%). Compared with the other dosing schedules, patients treated with dasatinib 100 mg QD appeared to require fewer dose interruptions and reductions as a result of pleural effusion, although the study design did not enable statistical comparison. Management methods used during the trial are similar to those reported previously.8,9 Because data on duration and resolution of pleural effusion were not collected during the 034 study, the relative effectiveness of different interventions for pleural effusion cannot be assessed, and this would be an potential area for future study.

The improved tolerability of 100 mg QD dosing may be driven in part by intermittent exposure to inhibitory drug concentrations, compared with the continuous exposure achieved with twice daily dosing.6 A pharmaco-kinetic analysis has recently demonstrated that the risk of pleural effusion with dasatinib decreased with decreasing plasma trough concentrations, with 100 mg QD dosing providing the lowest steady-state trough concentration compared with other treatment arms.10 Laboratory studies suggest that because of its high potency, transient exposure to dasatinib is sufficient to inhibit BCR-ABL kinase activity and induce apoptosis in CML cell lines.11 This may help to explain the equivalent efficacy observed across the 4 treatment arms of the 034 trial.

The exact mechanism of pleural effusion occurring during dasatinib therapy is unknown. Previous single-center studies have found that pleural effusions during dasatinib treatment were found to be exudative in the majority of cases.8,9 Based on reports of high lymphocyte frequency in pleural fluids and pleural tissue8 and an association with immune-mediated reactions, such as skin rash or a prior history of auto-immunity,12 immune-mediated mechanisms have been suggested. Supporting this hypothesis, a recent report by Mustjoki et al of patients with different phases of CML or Ph + ALL has demonstrated that patients who experienced lymphocytosis during dasatinib therapy experienced a higher occurrence of pleural effusion.13 In the present analysis, which includes patients with CML CP only, a possible association was also observed between patients who experienced lymphocytosis during dasatinib therapy and those who incurred pleural effusion, although the rate of pleural effusion in patients with lymphocytosis (29%) was lower than in the report by Mustjoki et al (~60%). However, a separate report did not find any association between lymphocytosis and pleural effusion.14 Because dasatinib inhibits targets other than BCR-ABL, alternative mechanisms have been suggested to explain fluid retention or pleural effusion during dasatinib treatment, including potent inhibition of PDGFR-β leading to a reduction in interstitial fluid pressure or inhibition of SRC-family kinases leading to changes in vascular permeability.9

In addition to prior history of an immune-mediated condition, other risk factors for the development of pleural effusion have been reported, including hypertension, history of cardiac disease, pulmonary comorbidity, dasatinib dosage of more than 100 mg per day, and treatment during advanced-phase CML.9,12,15 In this analysis, the study protocol and information collected precluded a similar evaluation of comorbidities, although older age was associated with an increased risk of pleural effusion. A previous univariate analysis also identified older age (more than 60 years) as a risk factors for pleural effusion, although there was no association during a subsequent multivariate analysis.9

In the present analysis, a possible association was observed between pleural effusion and lymphocytosis and the achievement of cytogenetic response on dasatinib treatment. In a previous study, pleural effusion during dasatinib therapy was associated with an increased rate of molecular responses, although the difference in rates of cytogenetic response was not significant.15 Other studies have reported that patients who developed lymphocytosis during dasatinib treatment achieved favorable treatment responses, and it was speculated that this might be due to potential antileukemic effects associated with immune activation.13,14 Additional prospective studies are required to confirm this possible association. The putative immune-mediated mechanism, including the occurrence of lymphocytosis, suggests that administration of corticosteroids may be appropriate for pleural effusion occurring with dasatinib.

In conclusion, this analysis demonstrates that in patients with CML CP with resistance, suboptimal response, or intolerance to prior imatinib, dasatinib 100 mg QD treatment minimizes the occurrence of pleural effusion. Importantly, the occurrence of a pleural effusion does not interfere with the achievement of hematologic or cytogenetic responses or duration of response, PFS, or overall survival.

Footnotes

David Dejardin (Bristol-Myers Squibb) provided assistance with statistical analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Funding for the clinical trial, statistical analysis, and medical writing assistance was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS). Kimmo Porkka has acted as a consultant, received honoraria, and received research funding from BMS and Novartis. H. Jean Khoury has received honoraria from BMS, Novartis, and Genzyme. Ronald L. Paquette has acted as a consultant for BMS, Alexion, and Telik, and has received honoraria and is a member of the Speakers Bureau for BMS and Novartis. Yousif Matloub and Ritwik Sinha own equity in and are employees of BMS. Yousif Matloub owns equity in GlaxoSmithKline. Jorge E. Cortes has received research funding from BMS, Wyeth, and Novartis.

References

- 1.O’Hare T, Walters DK, Stoffregen EP, et al. In vitro activity of Bcr-Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against clinically relevant imatinib-resistant Abl kinase domain mutants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4500–4505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortes J, Rousselot P, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib induces complete hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis. Blood. 2007;109:3207–3213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guilhot F, Apperley J, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib induces significant hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase. Blood. 2007;109:4143–4150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Deininger M, et al. Dasatinib induces durable cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Leukemia. 2008;22:1200–1206. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottmann O, Dombret H, Martinelli G, et al. Dasatinib induces rapid hematologic and cytogenetic responses in adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with resistance or intolerance to imatinib: interim results of a Phase II study. Blood. 2007;110:2309–2315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah NP, Kantarjian HM, Kim DW, et al. Intermittent target inhibition with dasatinib 100 mg once daily preserves efficacy and improves tolerability in imatinib-resistant and -intolerant chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3204–3212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochhaus A, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, et al. Dasatinib induces notable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of imatinib therapy. Blood. 2007;109:2303–2309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergeron A, Rea D, Levy V, et al. Lung abnormalities after dasatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia: a case series. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:814–818. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200705-715CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, et al. Pleural effusion in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with dasatinib after imatinib failure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3908–3914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Hochhaus A, Kantarjian HM, et al. Dasatinib pharmacokinetics and exposure-response (E-R): relationship to safety and efficacy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl 15):175s. Abstract 3590. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah NP, Kasap C, Weier C, et al. Transient potent BCR-ABL inhibition is sufficient to commit chronic myeloid leukemia cells irreversibly to apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lavallade H, Punnialingam S, Milojkovic D, et al. Pleural effusions in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia treated with dasatinib may have an immune-mediated pathogenesis. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:745–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustjoki S, Ekblom M, Arstila TP, et al. Clonal expansion of T/NK-cells during tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:1398–1405. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, Kamel-Reid S, Chang H, et al. Natural killer or natural killer/T cell lineage large granular lymphocytosis associated with dasatinib therapy for Philadelphia chromosome positive leukemia. Haematologica. 2009;94:135–139. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DH, Popradi G, Sriharsha L, Laneuville PJ, Messner HA, Lipton JH. Risk factors and management of patients with pulmonary abnormalities and Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia after treatment with Dasatinib: results from 2 institutions. Clin Leukemia. 2008;2:55–63. [Google Scholar]