Abstract

Objective

To assess 3D morphological variations and local and systemic biomarker profiles in subjects with a diagnosis of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis (TMJ OA).

Design

Twenty-eight patients with long-term TMJ OA (39.9 ± 16 years), 12 patients at initial diagnosis of OA (47.4 ± 16.1 years), and 12 healthy controls (41.8 ± 12.2 years) were recruited. All patients were female and had cone beam CT scans taken. TMJ arthrocentesis and venipuncture were performed on 12 OA and 12 age-matched healthy controls. Serum and synovial fluid levels of 50 biomarkers of arthritic inflammation were quantified by protein microarrays. Shape Analysis MANCOVA tested statistical correlations between biomarker levels and variations in condylar morphology.

Results

Compared with healthy controls, the OA average condyle was significantly smaller in all dimensions except its anterior surface, with areas indicative of bone resorption along the articular surface, particularly in the lateral pole. Synovial fluid levels of ANG, GDF15, TIMP-1, CXCL16, MMP-3 and MMP-7 were significantly correlated with bone apposition of the condylar anterior surface. Serum levels of ENA-78, MMP-3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, GM-CSF, TGFβb1, IFNγg, TNFαa, IL-1αa, and IL-6 were significantly correlated with flattening of the lateral pole. Expression levels of ANG were significantly correlated with the articular morphology in healthy controls.

Conclusions

Bone resorption at the articular surface, particularly at the lateral pole was statistically significant at initial diagnosis of TMJ OA. Synovial fluid levels of ANG, GDF15, TIMP-1, CXCL16, MMP-3 and MMP-7 were correlated with bone apposition. Serum levels of ENA-78, MMP-3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, GM-CSF, TGFβ1, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-1α, and IL-6 were correlated with bone resorption.

Keywords: Imaging biomarkers, protein biomarkers, image analysis

Introduction

The great challenge in Osteoarthritis (OA) treatment is that often the disease cannot be diagnosed until it becomes symptomatic, at which point structural alterations already are advanced. The ascertainment of variations between health and disease is essential information for detecting inflammatory and degenerative conditions of the tissues affected.1,2 An important emerging theme in OA is a broadening of focus from a disease of cartilage to a disease of the entire joint and the multiple biological systems that interact with one another in this disease. A variety of etiologic risk factors such as age, sex, trauma, overuse, genetics, hormones, and obesity contribute to the disease progressive nature in different compartments of the joint. The cross-talk that occurs between the components of the joint, which takes place over years, results in degradation of the articular cartilage and disc, bony changes, synovial proliferation, muscle and tendon weakness, and fatigue.3

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) condyle is the site of numerous dynamic morphologic transformations in the initiation/progression of OA, which are not merely manifestations secondary to cartilage degradation. The TMJ differs from other joints because a layer of fibrocartilage, and not hyaline cartilage, covers it. The bone of the mandibular condyles is located just beneath the fibrocartilage, making it particularly vulnerable to inflammatory damage and a valuable model for studying arthritic bony changes. While extensive assessments of arthritis in other joints have focused on loss or damage of hyaline cartilage, the capacity of cartilage to repair/modify the surrounding extracellular matrix is limited in comparison to bone4 (Figure 1). Thus, a strong rationale exists for therapeutic approaches that target bone resorption and formation and take into account the complex cross-talk between all of the joint tissues.

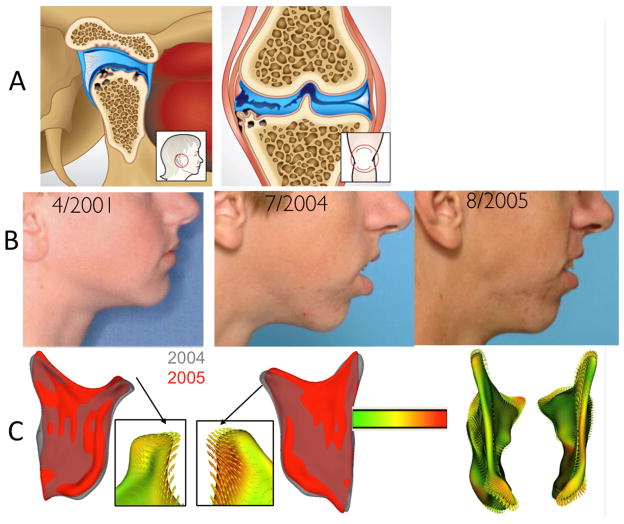

Figure 1.

A- The TMJ is a unique joint where the bone of the mandibular condyles is located just beneath the fibrocartilage, and not hyaline cartilage, making it particularly vulnerable to inflammatory damage and a valuable model for studying arthritic bony changes. The TMJ condyle is the site of numerous dynamic morphological transformations. B- Undiagnosed patient who presented Idiopathic Condylar Resorption who was treated orthodontically between 2001 and 2004. C- Note the progressive condylar resorption quantified by shape analysis.

No proven disease-modifying therapy exists for arthritis and current treatment options for chronic arthritic pain are insufficient.5 The NIH-funded Osteoarthritis (OA) Biomarkers Network established a system for categorizing biomarkers known as the BIPED system, where BIPED stands for burden of disease, investigative, prognostic, efficacy of intervention, and diagnostic.6 Over 100 protein mediators associated with arthritis initiation and progression, such as nociception, inflammation, angiogenesis and bone resorption, have been identified.7–13 The recent work of Slade et al suggests that not only local proteins in the synovial fluid may play a role in the cross-talk among the different joint tissues, but also circulating levels of pro-inflammatory proteins and systemic processes may contribute to the pathophysiology of disorders of the TMJ.14

With many affected tissues in TMJ OA, it is unlikely a single biomarker would drive and provide a comprehensive description of this intricate disease.7,10,13,15 Individual proteins are produced by and act on many cell types, and in many cases proteins have similar actions. It was the goal of this study to work towards a paradigm shift from looking for one specific biomarker to identify a disease process to the concept of looking for sets of biological and bone imaging markers to categorize a complex disease.16 Specifically, this study proposed to: 1) identify 3D morphological variations in asymptomatic controls, subjects at initial diagnosis TMJ OA and subjects with long term history of TMJ OA; and 2) assess systemic (serum) and local (synovial fluid) biomarker profiles in early onset of TMJ OA subjects, as compared to age matched controls. We hypothesized that bone morphology is characteristically different in OA compared to controls even at early diagnosis, and that variations in protein levels would correlate to the patterns of bone destruction and repair in the articular surfaces of the condyles in TMJ OA. To test these hypotheses, we determined associations of (1) circulating proteins with condylar morphology and case status of OA and healthy controls; and (2) synovial fluid proteins with condylar morphology and case status of OA and healthy controls.

Methods

Twenty-eight patients with long-term TMJ OA (39.9 ± 16 years), 12 patients at initial consult diagnosis of OA (47.4 ± 16.1 years) and 12 healthy controls (41.8 ± 12.2years), recruited from the university clinic and through advertisement, underwent a clinical exam by an orofacial pain specialist using the RDC guidelines. All patients were female. Following clinical diagnosis of TMJ osteoarthritis or health, a 20-second Cone beam CT (CBCT) scan was taken on all participants, using a large field of view to include both TMJs. The datasets obtained consisted of approximately 300 axial cross-sectional slices with voxels reformatted to an isotropic 0.5×0.5×0.5mm. Twelve OA and 12 age-matched controls also had TMJ arthrocentesis and venipuncture. This study is in concordance with STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies The data acquisition and analysis in this study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Image Analysis Methods

The process of construction of surface models from the CBCTs to perform the regional superimposition is called segmentation (performed with open-source ITK-SNAP 2.4 software, www.itksnap.org).17 3D surface mesh models of the right and left mandibular condyles were constructed by outlining the cortical boundaries of the condylar region using semi-automatic discrimination procedures, that allowed manual editing, checking slice by slice in all three planes of space. After generating all 3D surface models, left condyles were mirrored in the sagittal plane to form right condyles to facilitate comparisons. All condylar models were then cropped to a more defined region of interest consisting of only the condyle and a portion of the ramus. Twenty-five surface points were selected on each condyle by one observer at corresponding (homologous) areas to closely approximate the various anatomic regions of all individuals who present marked morphological variability: 4 points evenly spaced along the superior surface of the sigmoid notch, 4 on the medial and lateral portions of the ramus adjacent to the sigmoid notch, 3 along the posterior neck of the condyle, 3 on the medial and 3 on the lateral portion of the condylar neck, and on the medial, lateral, anterior, and posterior extremes of the condylar head (Figure 2A).18

Figure 2.

A and B- Landmark-based registration used to approximate condyles from all subjects in the group comparisons. A. 25 points in the ramus and condyle surfaces used for the landmark-based registration, B. Reference condylar model (red) with the overlay of multiple condyles approximated in the same coordinate system, C- Parameterization of 4,002 homologous or correspondent surface mesh points for statistical comparisons and detailed phenotypic characterization, D- Examples 3D surface models constructed from CBCT images for a subset of 15 patients in this study.

After registration, the cropping areas across 3D models were normalized and binary volumes were created from the surface models. SPHARM-PDM software 1.12 (open-source, http://www.nitrc.org/projects/spharm-pdm)19–22 was used to generate a mesh approximation from the volumes, whose points were mapped to a “spherical map”. In that spherical map, parameterization determined coordinate poles on each condylar model that allow the models to be related to one another in a consistent manner and identified 4,002 correspondent surface mesh points for statistical comparisons and detailed phenotypic characterization (Figure 2B). An average 3D condylar shape was generated for the TMJ OA groups and control group. Additionally, another set of average OA and control models were generated using only the condyle sampled by arthrocentesis for each participant, which were utilized in the second part of the study. The CBCT datasets were also independently interpreted by two Oral and maxillofacial radiologists. These interpretations were not used to classify participants as subjects or controls, but were later compared to the clinical findings.

Collection of Biological Samples

TMJ arthrocentesis was performed by an experienced OMF surgeon using a validated protocol.23–29 Synovial fluid was collected for only one TMJ for each patient. The joint chosen for arthrocentesis was selected based on the opinion of the pain specialist as to which joint was most affected. If both joints were equally affected, or if neither joint appeared to be affected (as with the control patients), the right joint was chosen. Arthrocentesis was performed using a push/pull technique in which 4ml of a saline solution was injected into the joint and then 4ml of solution withdrawn under local anesthesia. The saline solution consisted of 78% saline and 22% hydroxocobalamin, which is included in order to determine the volume of synovial fluid recovered in the aspirate by comparing the spectrophotometric absorbance of the aspirate with that of the washing solution. Venipuncture was performed on the median cubital vein of each patients’ left arm and 5ml of blood was obtained. Intravenous sedation for the aforementioned procedures was offered to each participant.

Measurements of Biological Samples

Custom quantibody protein microarrays RayBiotech (Norcross, GA) were used to evaluate the synovial fluid and serum samples for 50 biomarkers. This assay is array-based multiplex sandwich ELISA system for simultaneous, quantitative measurement the concentration of multiple proteins. Like an ELISA, it uses a pair of antigen-specific antibodies to capture the protein of interest. The use of biotinylated antibodies and a streptavidin-conjugated fluor allow detection levels for the specific proteins to be visualized using a fluorescence laser scanner.30 For protein quantification, the reagent kit included protein standards, whose concentration had been predetermined, provided to generate a six-point standard curve of each protein. Standards and samples were assayed simultaneously. By comparing signals from unknown samples to the standard curve, the unknown protein concentrations in the samples were determined. Positive controls for each biomarker were included in each array and the array data obtained from densitometry were inputted into the appropriate cells of the corresponding analysis tool, which plotted the standard curve for each analyte in addition to performing background subtraction/normalization. The biomarkers chosen were known to be associated with bone repair and degradation, inflammation or nociception, common processes seen in OA. Preprocessing steps for these samples were completed at the School of Dentistry and then shipped to RayBiotech for analysis. All samples were evaluated in duplicate using 2 separate slides with 19 and 31 proteins respectively, to control for proteins with cross-reactivity (the array with 19 proteins included αFGF, MMP-3, ANG, MMP-7, BDNF, MMP-9. BMP-2, NT-3, CXCL14/BRAK, PAI-1, GDNF, RANK, ICAM-1, TIMP-1, ICAM-3, VE-Cadherin, MIP-1β, MMP-10 and MMP-2; the array with 31 proteins included 6ckine, IFNγ, NT-4, βFGF, IGF-1, OPG, BLC, IL-1α, TGFβ1, CXCL16, IL-1β, TGFβ2, EGF, IL-6, TGFβ3, ENA-78, LIF, TIMP-2, FGF-7, MCP-1, TNFα, G-CSF, MIP-1α, TNFβ, GDF-15, MMP-1, VEGF, GM-CSF, MMP-13, HB-EGF and NGF R).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical framework for testing morphological variations of the condyles of 104 condyles included a Hotelling T-squared test in a multivariate analysis of covariance (Shape analysis MANCOVA)31–32 corrected for false discovery rate at 0.05; and for testing high dimensional hypothesis, Direction- Projection-Permutation (DiProPerm),33 aimed at rigorously testing whether lower dimensional graphically visual differences are statistically significant. DiProperm was assessed by three steps of determining Direction (project samples onto an appropriate direction), Projection (calculate univariate two sample statistic) and Permutation (assess significance using permutation test). Distance Weighted Discrimination (DWD) calculated a direction vector to classify high dimensional datasets. Because the control and OA samples have different sample size, an appropriately weighted versions of DWD, wDWD, 33 was used to find a direction vector in the feature space separating the morphology groups. The group membership was permuted 1000 times in this study.

Shape analysis MANCOVA was also used to test point-wise associations between each protein levels and individual differences in each one of the correspondent 4002 surface points in the morphology of each of the control and OA condyles with a significance level of 0.05. Because the condylar surface mesh data is recorded in three dimensions (x, y, and z) at 4002 locations and the sample size is only 12 condyles in each group, which represent high dimensional low sample size data, these findings were corrected for multiple comparisons by using a false discovery rate of 0.2.

Results

In the Radiologists’ interpretation of the CBCTs, for the asymptomatic control group, 41.7% of condyles were classified as having OA, 45.8% as indeterminate and 12.5% as normal. In the OA groups, all patients presented at least one of the condyles, right or left side with radiographic diagnosis of OA. In some patients one of the condyles was less affected, indeterminate or non-affected. In the initial diagnosis of OA group, 70.8% of condyles were given a radiographic diagnosis of OA while 25% were indeterminate based on the RDC criteria. In the long-term history of OA group, 80.4% of the condyles were given a radiographic diagnosis of OA (Table 1). These results are in comparison to the clinical diagnosis, which by design consisted of 50% OA and 50% normal. Qualitative assessment of the semi-transparent overlays revealed that even at their initial diagnostic appointment OA patient already present marked bone changes that are more marked in the group with long history of OA (Figure 3). The DiProPerm test found a statistically significant morphological difference (p-value = 0.0016) in the healthy control and the OA group with 1000 permutation statistics (Figure 3). Quantitative assessment of group comparisons were reported using vector distance maps and signed distance maps computed locally at each correspondent point (Figure 4). The mean OA models were of smaller size in all dimensions and areas of statistically significant difference were in the superior articular surface of the condyles particularly in the anterior and superior portion of the lateral pole (−2.3 mm indicative of bone resorption at the initial diagnosis group and −3.4mm in the long-term group. In the anterior surface of the condyle, a small area of 1.7mm of bone apposition was noted at initial diagnosis and 2.7mm at the long-term OA average models. When the initial diagnosis and long term OA average models were compared, statistically significant differences indicative of progression of bone resorption were noted along the whole condylar surface except at the superior surface of the lateral pole (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Description of the sample clinical and radiographic diagnoses.

| Clinical Diagnosis (n=51 patients, 102 condyles) | Radiographic Diagnosis (n=102 condyles) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | OA | Indeterminate | Healthy | |

| Healthy asymptomatic control (n=11 patients, 22 condyles) | 41.8 ± 12.2 | 45.5% (n=10) | 40.9% (n=9) | 13.6% (n=3) |

| Initial diagnosis of OA (n=12 patients, 224condyles) | 44.4 ± 14.4 | 70.8% (n=17) | 25% (n=6) | 4.2% (n=1) |

| Chronic OA (n=28 patients, 56 condyles) | 39.9 ± 16 | 80.4% (n=45) | 17.8% (n=10) | 13.6% (n=3) |

Figure 3.

Semi-transparent overlays of group average morphologies and DiProPerm statistics of OA versus control morphological differences. Note that even at their initial diagnostic appointment OA patients already present marked bone changes that are more severe in the group with long history of OA. In the DiProPerm graphic results, the left panel shows the distribution of the data projected onto the DWD direction, illustrating how well the two groups can be separated. The horizontal axis is the projected value, and the vertical axis reflects order in the data set, to avoid overplotting. The curves are smooth histograms, black for the full data set, with each color show the sub-histograms for that group. The right panel shows the results of the DiProPerm hypothesis test. 1000 permuted realizations of the t-statistic are shown as black dots. The thick black curve is a smooth histogram of the black dots, and the fit of a Gaussian distribution to the black dots is the thin curve. Comparing the tails of these distributions with respect to the green line (the actual t statistic) both show a strongly significant result.

Figure 4.

Quantitative assessment of condylar morphology. The top row shows comparisons using vector distance maps and signed distance maps computed locally at each correspondent surface point. Note that the vectors point inward in the areas indicative of bone resorption and outward in the areas of bone overgrowth. The bottom row shows the Statistical significance maps for comparison of group morphology. The average OA models were statistically significant different from the controls in the superior articular surface of the condyles at initial diagnosis of OA. Bone changes are significantly progressive in the condyle except on the superior surface of the lateral pole that resorbs early in the disease progression.

The results of the standard curves for both serum and synovial fluid showed that each essay detected a wide range of protein levels (both above and below the limits for certain biomarkers). Of the 50 biomarkers, the levels of 32 were consistently measured within the standard curve of detection in either blood and/or synovial fluid as presented in Table 2. Proteins levels below the limit of detection in either blood and/or synovial fluid are shown with red borders. Ten synovial fluid biomarkers and one serum biomarker highlighted in Table 2 demonstrated close to two-fold or greater variation between the OA and control groups. Because of the high variability in detection levels and small sample size of 12 matched pairs, median values rather than mean values for the biomarker detection levels are presented.

Table 2.

Median levels in pg/ml for serum and synovial fluid. Levels below the limit of detection are shown with red borders and variations of approximately 2x or greater between groups are highlighted

|

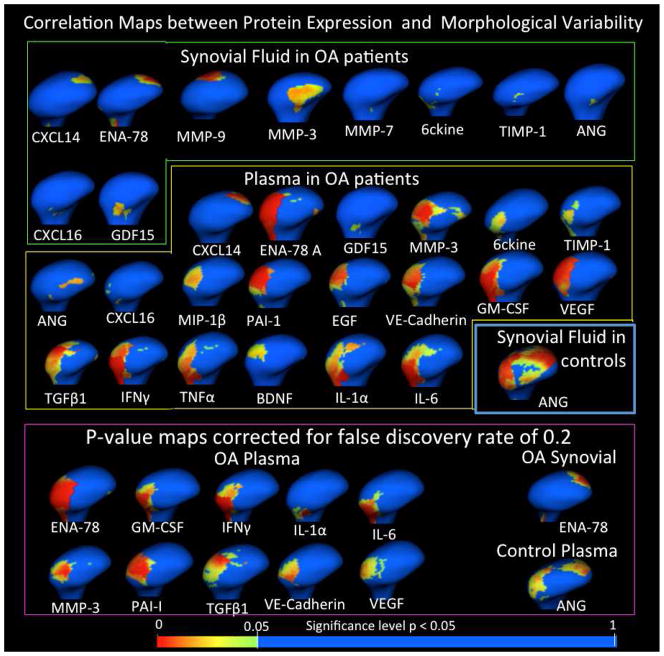

Of the 32 proteins detected above threshold, associations with the variability in condylar morphology at specific anatomic regions (p < 0.05) shown by Pearson Correlation color maps using the MANCOVA analysis were observed for 22 proteins: 10 in the synovial fluid, 8 of these same proteins in serum, and other 12 proteins in serum samples (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Results of Shape Analysis MANCOVA for Proteins in the synovial fluid and serum that presented statistically significant Pearson correlations between biomarker levels and morphology.

In the synovial fluid of patients with clinical diagnosis of OA, 6ckine and ENA-78 levels showed small areas of correlations with morphological differences in the lateral pole morphology. ANG, GDF15, TIMP-1, CXCL16, MMP-7 and MMP-3 showed small areas of correlations with morphological differences in the anterior surface of the condyle. MMP-3 levels were more than 2 fold lower in OA compared to controls in synovial fluid and presented significant correlations with condylar surfaces that present bone proliferation. ENA-78, CXCL14 and MMP-9 levels were correlated to morphological differences in the posterior surface of the condyle. Only ENA-78 continued to reveal significant correlations when the findings were corrected for false discovery rate of 0.2 (Figure 5).

In the serum of patients with clinical diagnosis of OA, ANG and GDF15 levels were significantly correlated with morphological differences in the anterior surface of the condyle. CXCL14 levels were correlated to morphological differences in the posterior surface of the condyle. 6ckine, ENA-78, TIMP-1, CXCL16, MMP-3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, MIP-1β, EGF, GM-CSF, TGFβ1, TNFα, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-6 and BDNF levels were significantly correlated to morphological variability in the latero-superior surface of the condyle. ENA-78, MMP-3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, GM-CSF, TGF1, IFNγ, IL-1α and IL-6 levels still presented significant correlations when the findings were corrected for false discovery rate of 0.2 (Figure 5).

In the control subjects for both synovial fluid and serum samples, the protein levels presented small interactions with condylar morphology that were not present with false discovery rate correction except for ANG in serum. ANG serum levels were significantly correlated with the superior surface of the condyle (p-value < 0.05) and even when corrected for false discovery of 0.2 (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 6.

Summary of biology/morphology interactions

Discussion

This study is the first to report an association between specific OA biomarkers and morphological variability at specific anatomic regions in 3D TMJ condyle surface. Advances in proteomics and 3D shape analysis have brought expectations for application of increased knowledge about mechanisms of osteoarthritis toward more effective and enduring therapies. This study highlights metrics and methods that may prove instrumental in charting the landscape of evaluating individual molecular and imaging markers so as to improve diagnosis, prognosis, and mechanism-based therapy.

Conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, ankylosis, spondylitis, and idiopathic condylar resorption require a comprehensive diagnostic model that integrates clinical, morphological and biomolecular assessments. Establishing connections between specific biomarker data and 3D imaging will possibly result in treatment modalities more specifically targeted towards the prevention or even reversal of joint destruction. Recently, the use of novel 3D imaging techniques using CBCT in conjunction with SPHARM-PDM shape analysis has been validated for use in identifying and measuring simulated discrete, bony defects in condyles as well as being used to identify various forms of osteoarthritic condylar changes such as flattening erosions and osteophyte formation and establishing a possible continuum of pathologic change in TMJ OA.34–35 Radiographic signs of bony changes associated with TMJ arthritides include irregular and possibly thickened cortical outlines (sclerosis), erosions, osteophyte formation, subchondral cysts, and flattening and narrowing of the joint space.36 CBCT images allow reliable detection and localization of bony changes, and increase the possibility for early detection of TMJ degenerative processes in asymptomatic patients.37 Early diagnosis and treatment of destructive inflammatory conditions is important to further control bone destruction successfully.38

This study demonstrated statistically significant smaller condyles in the OA group as compared to the control average and that significant bone loss in the superior and lateral articular surfaces has already occurred at initial diagnosis of OA. The overlays and signed distances between average OA and control condylar models, revealed that bone apposition/reparative proliferation in the antero-superior surface of the OA condyle were characteristic of OA morphology, leading to variability in condylar torque in OA patients.

In the synovial fluid samples, two of the most striking results of the MANCOVA analysis show that the levels of MMP-3 in synovial fluid, that were ~2 fold lower in the OA group compared to the controls, were correlated to areas of bone apposition/reparative proliferation that occurs in the anterior surface of the condyles, and ENA-78 was strongly correlated (p<0.01) to changes in the lateral pole and the posterior surface of the medial pole in the TMJ OA group (Figure 11).

As a member of the chemokine family, CXCL14/BRAK induces chemotaxis of monocytes, however it has been suggested that it is involved more in the homeostasis of monocyte-derived macrophages, which are associated with pathologic changes in OA.39 It is interesting to note that in this study local and systemic levels of CXCL14/BRAK shows the same pattern of morphologic correlations (Figures 11 and 12).

The biomarkers for which no association with morphology was established serve various physiologic and pathophysiologic processes and have been implicated in other studies as playing a role in arthritis.13 For example, MMP-2, which demonstrated differences in detection level between the OA and control groups in the synovial fluid, is involved in the degradation of type IV collagen, the major structural component of basement membranes and plays a role in the inflammatory response.39 Neither of these processes necessarily correlate to bony changes in OA, but might be more involved in the pathology of associated tissues (ie. the lining of the synovial membrane).

Also, TIMP-2, which again was elevated in the synovial fluid samples for the OA group, is an inhibitor of MMPs, and is thought to be critical in maintaining tissue homeostasis through interactions with angiogenic factors and by inhibiting protein breakdown processes, an activity associated with tissues undergoing remodeling of the ECM.

Interestingly, protein level measurements were much higher in serum than in synovial fluid. It could be questioned that arthritis localized in such small joints such as the TMJs may not lead to changes in systemic levels of proteins and that possibly undiagnosed arthritis of other joints in the body maybe confounders in serum protein expression. In this study, the level of 17 proteins in serum were significantly correlated with the resorption in the antero-superior surfaces of condylar lateral pole as shown in Figures 5: 6ckine, ENA-78, TIMP-1, CXCL16, MMP-3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, MIP-1β, EGF, GM-CSF, TGFβ1, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-1α, IL-6 and BDNF. Because this study findings represent high dimensional low sample size data, after correction of findings using a false discovery rate of 0.2, ENA78, MMP3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, GM-CSF, TGFβ1, IFNγ, IL-1α and IL-6 levels still presented significant correlations which indicates that 20% of the significant locations of interactions are expected to be falsely significant, but the overall pattern represents the interactions between those protein levels/morphological variability (Figure 5).

In the control subjects both in synovial fluid and serum, protein levels presented small interactions with condylar morphology in condylar surface regions that differ from the OA group. However, those small interactions cannot be verified when use false discovery rate correction. ANG levels were significantly correlated with the superior surface of the condyle (p-value < 0.05) and even when corrected for false discovery of 0.2 (Figure 5).

The biological investigation limited inclusion in the OA group to those individuals with a recent diagnosis and onset. Several of the biomarkers investigated did not demonstrate significantly variable expression between the two groups, and those for which no morphological association could be established, have been previously investigated by other groups and found to be associated with clinical diagnosis of OA, either in the TMJ or another joint. It is possible that by limiting this investigation to recent onset OA, the disease had not progressed to a stage where these biomarkers play as paramount of a role.

A limitation of this study was the inability to test biomarkers in pairs or groups to evaluate whether or not there is cross-reactivity between them that is associated with condylar morphology. This should be an aim of future investigations in this area, as testing biomarkers in groups will likely be a more accurate representation of the in vivo state.40

Without FDR correction, 22 cytokines presented interactions with early signs of bone remodeling in the articular surfaces of the condyles that are already observed at the first clinical diagnosis. The levels of MMP-3 in synovial fluid, that were ~2 fold lower in the OA group compared to the controls, were correlated to the bone apposition that occurs in the anterior surface of the condyles and leads to characteristic changes in condylar torque and morphology. Other proteins in serum and synovial fluid that may play a role in the bone apposition of the anterior surface of the condyles include ANG, GDF15, TIMP-1, CXCL16 and MMP-7. Bone resorption with flattening and reshaping of the lateral pole of the condyle involves molecular pathways with interaction of 17 proteins measured in this study: 6ckine, ENA-78, TIMP-1, CXCL16, MMP-3, PAI-1, VE-Cadherin, VEGF, MIP-1β, EGF, GM-CSF, TGFβ1, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-1α, IL-6 and BDNF. Considering the use of FDR correction for more conservative conclusions in this pioneer study, levels of 10 proteins in serum samples and 1 protein in synovial fluid were correlated with resorptive bone remodeling in OA subjects Six other protein levels in synovial fluid were correlated with bone overgrowth in the anterior articular surface. Such interactions are a first step to elucidate contributions of various biomarkers to characteristic phenotypes of an early onset temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis, while advancing towards developing a comprehensive OA model.

These study findings revealed a comprehensive inflammatory, angiogenic, and tissue destruction biomarker profile that correlates with the bone resorption and repair at the articular surfaces of the condyle. The novel aspect of this study is that, even tough the ability of the biomarkers to predict progression was not addressable in the cross-sectional study design, these biomarkers can be reasonable surrogate biomarkers of tissue destruction and/or repair overtime, as well as classification schemes. The synovial and serum-derived biomarkers may be predictive of real-time changes or predictive of future resorption. Future studies may now allow combinatorial biomarker assessments such as receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves on disease versus health.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DE024450.

Role of the funding source

The source of funding had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

All authors had no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) their work.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Okeson JP. Orofacial Pain. Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management. Quintessence; Chicago, IL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellman M. Variation in occlusion. Dental Cosmos. 1921;63:608–619. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramson SB, Attur M. Developments in the scientific understanding of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:227. doi: 10.1186/ar2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayami T, Pickarski M, Wesolowski GA, McLane J, Bone A, Destefano J, Rodan GA, Duong le T. The role of subchondral bone remodeling in osteoarthritis: reduction of cartilage degeneration and prevention of osteophyte formation by alendronate in the rat anterior cruciate ligament transection model. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1193–206. doi: 10.1002/art.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karsdal MA, Martin TJ, Bollerslev J, Christiansen C, Henriksen K. Are nonresorbing osteoclasts sources of bone anabolic activity? J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:487–494. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter DJ, Eckstein F, EKraus VB, Losina E, Sandel L, Guermazi A. Imaging Biomarker Validation and Qualification Report: Sixth OARSI Workshop on Imaging in Osteoarthritis combined with Third OA. Biomarkers Workshop. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2013;21:939e942. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer DC, Hunter DJ, Abramson SB, Attur M, Corr M, Felson D, Heinegård D, Jordan JM, Kepler TB, Lane NE, Saxne T, Tyree B, Kraus VB. Classification of osteoarthritis biomarkers: A proposed approach. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2006;14:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadhwa S, Kapila S. TMJ disorders: Future innovations in diagnostics and therapeutics. Journal of Dental Education. 2008;72:930–947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDougall JJ, Andruski B, Schuelert N, Hallgrimsson B, Matyas JR. Unravelling the relationship between age, nociception and joint destruction in naturally occurring osteoarthritis of dunkin hartley guinea pigs. Pain. 2009;141:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dam EB, Loog M, Christiansen C, Byrjalsen I, Folkesson J, Nielsen M, et al. Identification of progressors in osteoarthritis by combining biochemical and MRI-based markers. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2009;11:R115. doi: 10.1186/ar2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addison S, Coleman RE, Feng S, McDaniel G, Kraus VB. Whole-body bone scintigraphy provides a measure of the total-body burden of osteoarthritis for the purpose of systemic biomarker validation. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60:3366–3373d. doi: 10.1002/art.24856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Spil WE, DeGroot J, Lems WF, Oostveen JC, Lafeber FP. Serum and urinary biochemical markers for knee and hip-osteoarthritis: A systematic review applying the consensus BIPED criteria. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage/OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2010;18(5):605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rousseau JC, Delmas PD. Biological markers in osteoarthritis. Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology. 2007;3(6):346–356. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slade GD, Conrad MS, Diatchenko L, Rashid NU, Zhong S, Smith S, Rhodes J, Medvedev A, Makarov S, Maixner W, Nackley AG. Cytokine biomarkers and chronic pain: association of genes, transcription, and circulating proteins with temporomandibular disorders and widespread palpation tenderness. Pain. 2011 Dec;152(12):2802–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuels J, Krasnokutsky S, Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis: A tale of three tissues. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 2008;66(3):244–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Spil, Jansen Bijlsma, Reijman DeGroot, Welsing Lafeber. Clusters within a wide spectrum of biochemical markers for OA: data from CHECK, a large cohort of individuals with very early symptomatic OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012 Jul;20(7):745–54. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itksnap.org. Philapelphia: Penn Image Computing and Science Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania; [homepage on the internet] [updated 2013 April 17; cited 2013 Oct15]. Available from: http://www.itksnap.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php?n=Main.Downloads. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schilling J, Gomes LC, Benavides E, Nguyen T, Paniagua B, Styner M, Boen V, Gonçalves JR, Cevidanes LH. Regional 3D superimposition to assess temporomandibular joint condylar morphology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;43(1):20130273. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20130273. Epub 2013 Oct 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cevidanes LH, Hajati AK, Paniagua B, Lim PF, Walker DG, Palconet G, Nackley AG, Styner M, Ludlow JB, Zhu H, Phillips C. Quantification of condylar resorption in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paniagua B, Cevidanes LHS, Walker D, Zhu H, Guo R, Styner M. Clinical application of SPHARM-PDM to quantify temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 2011;35:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Styner M, Oguz I, Xu S, Brechbühler C, Pantazis D, Levitt JJ, Shenton ME, Gerig G. Framework for the Statistical Shape Analysis of Brain Structures using SPHARM-PDM. Insight J. 2006;1071:242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuroimaging Informatics Tools and Resources Clearinghouse (NITRC.org) Projects Spharm-PDM [homepage on the Internet] Chapel Hill: Neuro Image Research and Analysis Laboratories, University of North Carolina; [updated 2013 Jul 21; cited 2013 Jul 22]. Available from: http://http://www.nitrc.org/projects/spharm-pdm. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordahl S, Alstergren P, Eliasson S, Kopp S. Interleukin-1beta in plasma and synovial fluid in relation to radiographic changes in arthritic temporomandibular joints. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 1998;106(1):559–563. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1998.eos106104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alstergren P. Pain and synovial fluid concentration of serotonin in arthritic tempormandibular joints. Pain (Amsterdam) 1997;72:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alstergren P. Cytokines in temporomandibular joint arthritis. Oral Diseases. 2000;6:331–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nordahl S, Alstergren P, Kopp S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in synovial fluid and plasma from patients with chronic connective tissue disease and its relation to temporomandibular joint pain. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: Official Journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2000;58(5):525–530. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alstergren P. Prostaglandin E2 in temporomandibular joint synovial fluid and its relation to pain and inflammatory disorders. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2000;58:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alstergren P, Kopp S, Theodorsson E. Synovial fluid sampling from the temporomandibular joint: Sample quality criteria and levels of interleukin-1 beta and serotonin. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 1999;57(1):16–22. doi: 10.1080/000163599429057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alstergren P. Interleukin-1B in synovial fluid from the arthritic temporomandibular joint and its relation to pain, mobility, and anterior open bite. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1998;56:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.RayBiotech. [Accessed October 15, 2013];Quantibody Arrays. 2012 http://www.raybiotech.com/quantibody-en-2.html.

- 31.Neuroimaging Informatics Tools and Resources Clearinghouse (NITRC.org) Projects Shape Analysis Mancova. Chapel Hill: Neuro Image Research and Analysis Laboratories, University of North Carolina; [homepage on the Internet] [updated 2013 June 27; cited 2013 Oct 15]. Available from: http://http://www.nitrc.org/projects/shape_mancova. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paniagua B, Styner M, Macenko M, Pantazis D, Niethammer M. Local shape analysis using MANCOVA. Insight Journal. 2009 Sep; [serial on the Internet] [cited 2013 Oct 15; about 21 p.]. Available from: http://www.insight-journal.org/browse/publication/694.

- 33.Qiao X, Zhang HH, Liu Y, Todd MJ, Marron JS. Weighted Distance Weighted Discrimination and its Asymptotic Properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;105(489):401–414. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2010.tm08487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cevidanes L. Quantification of condylar resorption in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontics. 2010;110:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cevidanes LHS, Walker D, Styner M, Lim PF. Condylar resorption in patients with TMD. In: McNamara JA Jr, Kapila SD, editors. Temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain - separating controversy from consensus. 2008. p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmad M. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD): Development of image analysis criteria and examiner reliability for image analysis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontics. 2009;107(6):844–860. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexiou K, Stamatakis H, Tsiklakis K. Evaluation of the severity of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritic changes related to age using cone beam computed tomography. Dento Maxillo Facial Radiology. 2009;38(3):141–147. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/59263880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allaart CF, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, et al. Aiming at low disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with initial combination therapy orinitial monotherapy strategies: the BeSt study. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2006;24(6 Suppl 43):S77–S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NCBI Gene Database [Internet] Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine; [cited 2013 Dec 19]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams FM. Biomarkers: In combination they may do better. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2009;11(5):130. doi: 10.1186/ar2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]