Abstract

Blood progenitors within the lymph gland, a larval organ that supports hematopoiesis in Drosophila melanogaster, are maintained by integrating signals emanating from niche-like cells and those from differentiating blood cells. We term the signal from differentiating cells the ‘equilibrium signal’ in order to distinguish it from the ‘niche signal’. Earlier we showed that equilibrium signaling utilizes Pvr (the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor), STAT92E, and adenosine deaminase-related growth factor A (ADGF-A) (Mondal et al., 2011). Little is known about how this signal initiates during hematopoietic development. To identify new genes involved in lymph gland blood progenitor maintenance, particularly those involved in equilibrium signaling, we performed a genetic screen that identified bip1 (bric à brac interacting protein 1) and Nucleoporin 98 (Nup98) as additional regulators of the equilibrium signal. We show that the products of these genes along with the Bip1-interacting protein RpS8 (Ribosomal protein S8) are required for the proper expression of Pvr.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.03626.001

Research organism: D. melanogaster

eLife digest

Progenitor cells are cells that can either multiply to make new copies of themselves or mature into different specialized cell types—such as blood cells. In the fruit fly Drosophila, new blood cells are formed in several different locations, including in an organ called the lymph gland.

In 2011, researchers found that the fate of blood progenitor cells within the lymph gland is controlled by signals from two nearby sources—one from specialized, supportive (‘niche’) cells and the other from maturing blood cells. The signal from the maturing blood cells ensures that the relative amounts of progenitor and maturing blood cells are kept in the right balance. As a result, this signaling process has been called ‘equilibrium signaling’.

Questions remain as to how equilibrium signaling is regulated, and how it interacts with signals from the niche. To investigate this, Mondal et al.—including some of the researchers involved in the 2011 work—used various genetic techniques to create Drosophila larvae in which the tissues that become blood cells are made visible with fluorescent proteins. This meant that these tissues could be examined in live, whole animals by using a microscope. Mondal et al. then searched for the Drosophila genes involved in generating new blood cells in the lymph gland—particularly those involved in equilibrium signaling. This was done by switching on and off hundreds of genes, one by one, in the lymph gland, and any genes that caused changes to the generation of new blood cells were then investigated further.

Following these investigations, Mondal et al. focused on three genes—and when each of these genes was switched off in maturing blood cells, the result was that fewer progenitor cells remained in the lymph gland. This effect was not seen when the genes were switched off in the progenitor or the niche cells, which suggested that the genes are likely to be components of the equilibrium signaling pathway. Switching off these genes in maturing blood cells also dramatically reduced the levels of a protein called Pvr, a key equilibrium signaling protein known from the 2011 study and an important player in blood cell development in several species.

How the newly identified genes actually control Pvr protein levels to maintain proper equilibrium signaling in the lymph gland remains to be explored. However, this work provides a basis for investigating the role of related genes in blood cell development in vertebrate systems, namely humans.

Introduction

Similar to vertebrates, blood cell differentiation in Drosophila is regulated in multiple hematopoietic environments, which include the head mesoderm of the embryo (Tepass et al., 1994; Lebestky et al., 2000; Milchanowski et al., 2004), the specialized, tissue-associated microenvironments of the larval periphery (e.g, body wall hematopoietic pockets) (Markus et al., 2009; Makhijani et al., 2011), and the larval lymph gland, an organ dedicated to the development of blood cells that normally contribute to the pupal and adult stages (Rizki, 1978; Shrestha and Gateff, 1982; Lanot et al., 2001; Jung et al., 2005). Understanding how blood cell development is regulated in the lymph gland is the primary goal underlying the work presented here. Differentiating blood cells (hemocytes) of the lymph gland are derived from multipotent progenitors (Jung et al., 2005; Mandal et al., 2007; Martinez-Agosto et al., 2007). These blood progenitors readily proliferate during the early growth phases of lymph gland development, which is followed by a period in which many of these cells slow their rate of division and are maintained without differentiation in a region termed the medullary zone (MZ, Figure 1) (Jung et al., 2005; Mandal et al., 2007). During the same period, other progenitor cells begin to differentiate along the peripheral edge of the lymph gland to give rise to a separate cortical zone (CZ) (Jung et al., 2005). How progenitor cell maintenance and differentiation are regulated during the course of lymph gland development has become a major area of exploration in recent years, and several different signaling pathways have been identified that maintain progenitor cells through the larval stages (Lebestky et al., 2003; Mandal et al., 2007; Owusu-Ansah and Banerjee, 2009; Sinenko et al., 2009; Mondal et al., 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2011; Tokusumi et al., 2011; Dragojlovic-Munther and Martinez-Agosto, 2012; Pennetier et al., 2012; Shim et al., 2012; Sinenko et al., 2012). Wingless (Wg; Wnt in vertebrates) is expressed by blood progenitor cells in the lymph gland and has an important role in promoting their maintenance (Sinenko et al., 2009), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) function in these cells to potentiate blood progenitor differentiation both in the context of normal development and during oxidative stress (Owusu-Ansah and Banerjee, 2009). Progenitor cell maintenance at late developmental stages is also dependent upon Hedgehog (Hh) signaling from a small population of cells called the posterior signaling center that functions as a hematopoietic niche (PSC) (Lebestky et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2005).

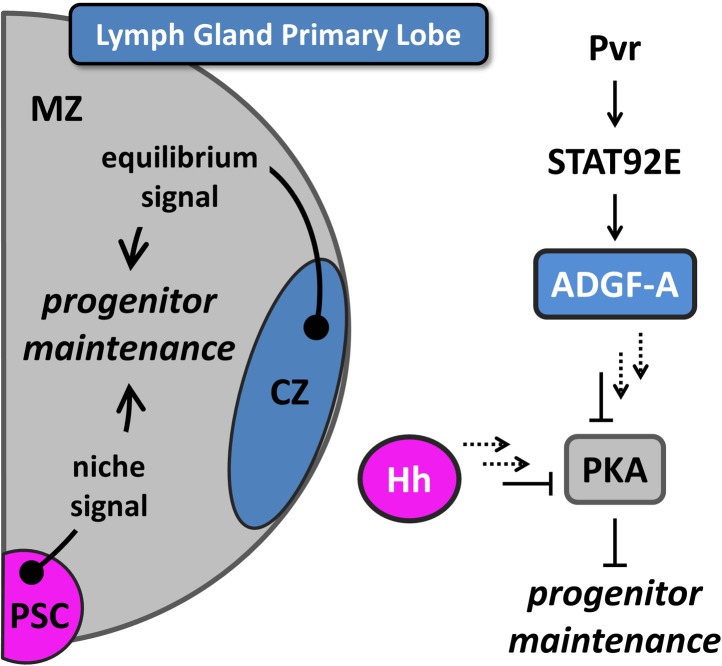

Figure 1. Equilibrium signaling maintains hematopoietic progenitors in the developing lymph gland.

The lymph gland primary lobe consists of three distinct cellular populations or zones. The medullary zone (MZ) contains blood progenitor cells while the nearby cortical zone (CZ) contains differentiating and mature blood cells. The posterior signaling center (PSC) functions as a supportive population (a niche) that expresses Hedgehog (Hh) and maintains the progenitor cells utilizing this ‘niche signal’. The receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) Pvr and the STAT (STAT92E) transcriptional activator are required in CZ cells for the proper expression and secretion of the extracellular enzyme ADGF-A, which keeps the extracellular adenosine levels relatively low by converting it to inosine. The Pvr ligand Pvf1 is made in PSC cells and is transported through the lymph gland to activate Pvr in CZ cells. Collectively, we refer to the system that generates ADGF-A from the differentiating cells as ‘equilibrium signaling’, which is required independently of the niche-derived Hh signaling for the maintenance of progenitor blood cells in the MZ. Signaling events downstream of both ADGF-A and Hh (dashed arrows) cause the inhibition of Protein Kinase A (PKA) within progenitor blood cells, thereby promoting their maintenance. The individual components are color coded to match the schematic of the lymph gland. The equilibrium signal ADGF-A is blue, originating from the CZ; the niche signal Hh is magenta, originating in the PSC; PKA is gray, functioning in the MZ progenitor cells. Full details of this molecular pathway can be found in Mondal et al., (2011).

More recently, it has been discovered that the maintenance of lymph gland blood progenitors also requires a backward signal arising from the differentiating cells (Mondal et al., 2011). This signal is controlled by a novel pathway that combines the function of the receptor tyrosine kinase Pvr and JAK-independent STAT (STAT92E) activation in differentiating cells, followed by the expression of ADGF-A (Figure 1), a secreted enzyme that converts adenosine to inosine (Mondal et al., 2011). Extracellular adenosine is a well-established signal in mammalian systems in various contexts, particularly stress conditions (Fredholm, 2007; Sheth et al., 2014), and an elevated adenosine level in Drosophila causes extensive blood cell proliferation (Dolezal et al., 2005; Mondal et al., 2011). It has been demonstrated that differentiating and mature cells express (and are the primary source of) ADGF-A, and that its enzymatic activity (which converts adenosine to inosine) is required for progenitor cell maintenance (Mondal et al., 2011). As differentiation proceeds, ADGF-A expression (activity) increasingly promotes the maintenance of extant blood progenitors through the reduction of stimulatory adenosine. In this way, the differentiating cell population helps balance the progenitor/differentiating cell ratio and is the basis for our referring to ADGF-A as an ‘equilibrium signal’.

Loss of ADGF-A (or STAT or Pvr) from differentiating cells increases extracellular adenosine level and thereby increases Adenosine Receptor (AdoR) signaling and downstream Protein Kinase A (PKA) activity in progenitors, which causes these cells to proliferate (Dolezal et al., 2005; Mondal et al., 2011). PKA is a central regulator of progenitor maintenance because it integrates input from both the equilibrium signal (ADGF-A) and the niche signal (Hh). PKA mediates the conversion of the transcriptional regulator Cubitus interruptus (Ci, a homolog of vertebrate Gli) from its full length form (Ci155), required for progenitor maintenance (Mandal et al., 2007), to a cleaved form (Ci75) that promotes proliferation. Signaling by Hh inhibits PKA and promotes Ci155 stabilization whereas adenosine/AdoR signaling activates PKA and promotes Ci75 conversion. Thus, both Hh (the niche signal) and ADGF-A (the equilibrium signal which removes adenosine) limit PKA activity and promote progenitor cell maintenance.

Although niche and equilibrium signaling are both clearly important, details of their regulation and interaction are less clear. Thus, we performed a loss-of-function genetic screen to identify new genes involved in lymph gland blood progenitor maintenance, particularly those involved in equilibrium signaling. In this study, we report the results of this screen and the identification of three genes, bip1, RpS8, and Nup98, as new components of the equilibrium signaling pathway.

Results and discussion

HHLT-gal4 and its use for whole-animal genetic screening during hematopoietic development

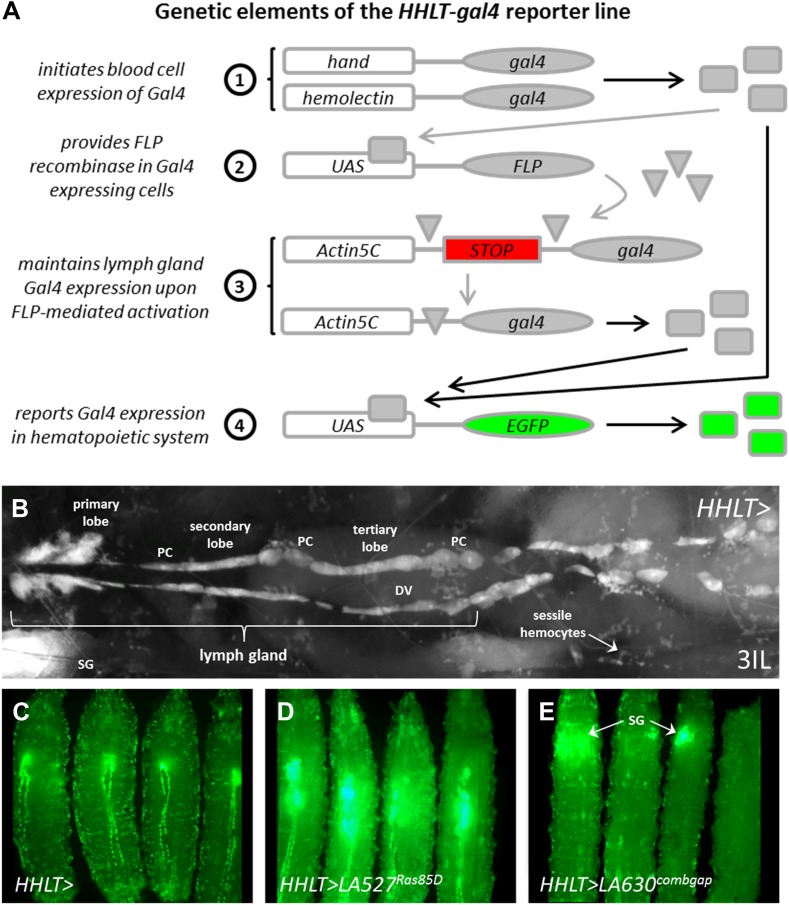

Unlike the adult eye or wing, analysis of internal larval tissues such as the lymph gland requires laborious dissection and processing. To circumvent this barrier to genetic screening, we generated a line of flies termed the Hand-Hemolectin Lineage Traced-gal4 line (HHLT-gal4 UAS-2XEGFP, Figure 2A; see ‘Materials and methods’ for precise genotype) in which the hematopoietic system is labeled by Gal4-dependent expression of EGFP, such that it can be visualized in live, whole animals (Figure 2B–C). This line makes use of two gal4 drivers to target early lymph gland blood cells (hemocytes; Hand-gal4) and circulating and sessile blood cells (Hemolectin-gal4 or Hml-gal4) and incorporates a Gal4/FLP recombinase-dependent cell lineage tracing cassette to maintain Gal4 expression in the lymph gland after the Hand-gal4 driver itself is down-regulated during the first instar. The Hand-gal4 driver is expressed in the embryonic cardiogenic mesoderm from which the lymph gland is derived. Therefore, the dorsal vessel (heart) cardioblasts and the pericardial nephrocytes are also marked by the cell lineage tracing cassette (Figure 2B). EGFP is not expressed in other larval tissues, except in the late third-instar salivary glands that are readily discernible from the hematopoietic system (Figure 2B,E).

Figure 2. The Hand-Hemolectin Lineage Tracing-gal4 line (HHLT-gal4 UAS-2XEGFP) and its use as an in vivo screening tool.

(A) Schematic describing the key elements of the HHLT-gal4 driver line. (B) Image showing the hematopoietic system within a wandering stage third-instar HHLT > GFP larva (dorsal view). Primary, secondary, and tertiary lobes of the lymph gland are readily discernible through overlying musculature, epidermal cells, and cuticle. Lymph gland lobes develop bilaterally, flanking the larval heart (dorsal vessel, DV). Non-blood pericardial cells (PC) also express GFP due to early expression of Hand-gal4. Circulating/sessile blood cells also express GFP due to Hml-gal4 and sessile groups are easily observable. GFP is also seen in ventrally located salivary glands (SG, out of focus) of larvae beyond the third-instar transition (due to Hand-gal4). (C) HHLT > GFP control larvae; (D) HHLT > GFP larvae overexpressing Ras85D (LA 527) exhibit hyperproliferative lymph glands; (E) HHLT > GFP larvae overexpressing combgap (LA 630) show little or no GFP expression in the lymph gland region. Arrows indicate GFP fluorescence from salivary glands (SG).

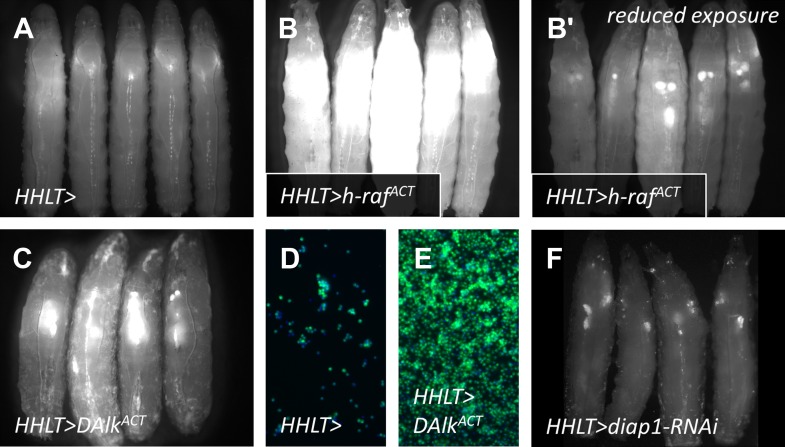

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. As a ‘proof-of-principle’ approach and to assess the effectiveness of HHLT-gal4 as a screening tool, HHLT-gal4 was crossed to lines harboring gain-of-function UAS transgenes known to cause excessive cellular proliferation, with the expectation that such transgenes would cause significant expansion of the hematopoietic tissues.

Screening for progenitor maintenance genes in the developing lymph gland

A screen was conducted in which HHLT-gal4 was used to independently misexpress 503 unique UAS-controlled Drosophila genes, with their effects on the hematopoietic system assessed in whole animals based upon EGFP expression. The particular collection of UAS-based gene misexpression lines used (termed LA lines) are mapped insertions (against Flybase release 5.7) of the P{Mae-UAS.6.11} element into endogenous gene loci that have been previously shown to cause developmental phenotypes upon misexpression (Crisp and Merriam, 1997; Bellen et al., 2004). When crossed to HHLT-gal4, 281 of these lines cause a scorable phenotype in either lymph glands or circulating blood cells of late third-instar larvae (Supplementary file 1). As an example, LA line 527, which is predicted to misexpress Ras85D, causes a robust expansion of the lymph gland (Figure 2D), consistent with the previously identified role of Ras85D in controlling hemocyte proliferation (Asha et al., 2003; Sinenko and Mathey-Prevot, 2004). By contrast, LA line 630 misexpresses the gene combgap (encoding a zinc finger transcription factor) and causes a strong reduction in lymph gland size (Figure 2E).

We used these results from the misexpression screen as a means to select potentially relevant genes for the subsequent loss-of-function analyses by RNA interference (using UAS-RNAi lines). We were able to obtain RNAi lines targeting 251 of the candidate genes identified by misexpression and found that 73 RNAi lines targeting 69 genes alter lymph gland size or morphology when crossed to HHLT-gal4 (Supplementary file 2).

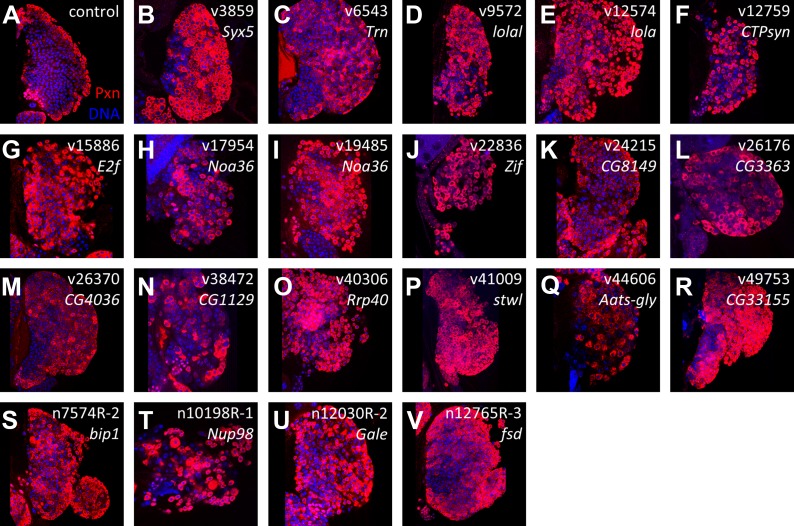

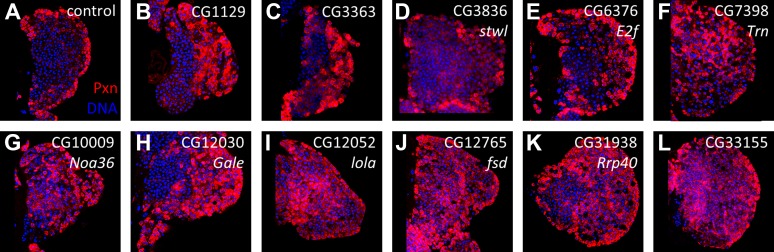

To characterize the RNAi phenotypes in more detail, the level of blood cell differentiation within the lymph gland was evaluated by immunostaining with anti-Peroxidasin (Pxn) antibodies (Nelson et al., 1994). In wild-type lymph glands, expression of mature cell markers such as Pxn is restricted to the periphery of the primary lobe (the cortical zone) (Jung et al., 2005). By contrast, when niche signaling or equilibrium signaling are compromised, progenitor cells are lost and differentiation markers, including Pxn, are expressed throughout the lymph gland primary lobes (Mandal et al., 2007; Mondal et al., 2011). Rescreening the 73 identified RNAi lines using HHLT-gal4 identified 20 genes (21 RNAi lines) that, when knocked down, cause the expression of Pxn in cells throughout the lymph gland primary lobe (Figure 3; Table 1 and Supplementary file 2). Compared to controls, the progenitor population (Pxn negative) is either strongly reduced or absent in each RNAi background. This ‘expanded’ Pxn phenotype is interpreted as a loss-of-progenitor cell phenotype.

Figure 3. Identification of RNAi lines that cause an expanded Peroxidasin phenotype when expressed throughout the lymph gland.

Peroxidasin (Pxn, red) is normally restricted to cortical zone cells (near the periphery) (A, control) but is seen throughout the lymph gland in RNAi backgrounds (B–V) expressed by HHLT-gal4. Line identifiers and gene targets are shown; additional details listed in Table 1. Images represent a single middle confocal section taken from a Z-plane series through the entire primary lobe.

Table 1.

RNAi lines and target genes causing an ‘expanded’ Peroxidasin expression phenotype with HHLT-gal4

| Line # | UAS-RNAi ID | RNAi target | Gene | Off targets | LG size/quality | Protein function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3859 | CG4214 | Syx5 | 0 | Small/missing | Golgi SNARE |

| 2 | 6543 | CG7398 | Trn | 1 | Large/baggy | hnRNP nuclear import |

| 3 | 9572 | CG5738 | lolal | 0 | Small | Transcription factor |

| 4 | 12574 | CG12052 | lola | 0 | Large/baggy | Transcription factor |

| 5 | 12759 | CG6854 | CTPsyn | 0 | Small/baggy | CTP synthase |

| 6 | 15886 | CG6376 | E2f | 1 | Small/normal | Transcription factor |

| 7 | 17954 | CG10009 | Noa36 | 0 | Small/missing | Zinc finger nucleolar protein |

| 8 | 19485 | CG10009 | Noa36 | 0 | Small/missing | Zinc finger nucleolar protein |

| 9 | 22836 | CG10267 | Zif | 0 | Small/missing | Transcription factor |

| 10 | 24215 | CG8149 | CG8149 | 0 | Baggy | DNA binding protein |

| 11 | 26176 | CG3363 | CG3363 | 0 | Small | Unknown |

| 12 | 26370 | CG4036 | CG4036 | 1 | Large | Oxidoreductase |

| 13 | 38472 | CG1129 | CG1129 | 0 | Small/missing | Peptide transferase |

| 14 | 40306 | CG31938 | Rrp40 | 0 | Small/normal | RNA exosome |

| 15 | 41009 | CG3836 | stwl | 0 | Small/normal | Transcription factor |

| 16 | 44606 | CG6778 | Aats-gly | 0 | Small/missing | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase |

| 17 | 49753* | CG33155 | CG33155 | 4 | Small/normal | Unknown |

| 18 | 7574R-2 | CG7574 | bip1 | 0 | Small/baggy | Transcription factor |

| 19 | 10198R-1 | CG10198 | Nup98-96 | 0 | Small/missing | Nucleoporin |

| 20 | 12030R-2 | CG12030 | Gale | 0 | Small | UDP-galactose 4'-epimerase |

| 21 | 12765R-3 | CG12765 | fsd | 0 | Small/normal | F-box protein |

This RNAi line targeting sequence overlaps with the putative mRpL53 gene in the same locus. Lines 1–17 from VDRC, lines 18–21 from NIG Japan.

Zone-specific screening identifies putative equilibrium signaling genes

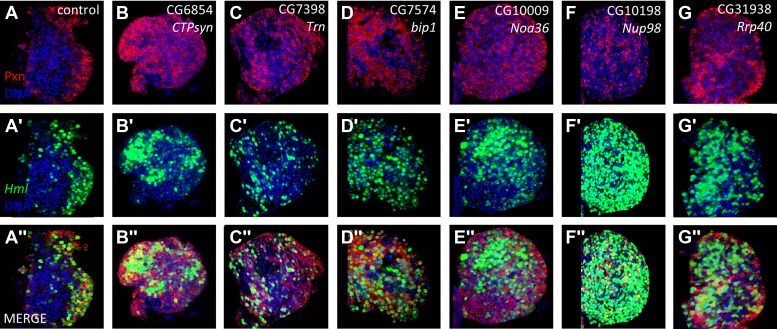

Using the pan-lymph gland HHLT-gal4 driver, we identified 21 RNAi lines that cause a loss of progenitor cells in the primary lobes at late stages of lymph gland development. In order to discern whether any of the associated candidate genes have a specific progenitor-maintenance function that is restricted to cells belonging to a single zone, we rescreened the 21 RNAi lines using cell-type-specific Gal4-expressing lines. Targeting RNAi to differentiating and mature cells using Hml-gal4 (Sinenko and Mathey-Prevot, 2004) identified six genes (CG6854 [CTPsyn], CG7398 [Transportin], CG7574 [bip1], CG10009 [Noa36], CG10198 [Nup98, also known as Nup98-96], and CG31938 [Rrp40]) that cause an expansion of Pxn (Figure 4A–G) and Hml-gal4, UAS EGFP (Figure 4H–M) expression. Since the function of these genes is needed in the CZ for the maintenance of the MZ progenitors, these six genes encode likely candidates for new components of the equilibrium signaling pathway.

Figure 4. Identification of candidate genes that cause an expanded Peroxidasin expression phenotype within the lymph gland when knocked down by RNAi in differentiating and mature cells.

RNAi from identified lines (Figure 3/Table 1) was expressed in lymph glands using Hml-gal4 UAS-GFP (Hml > GFP). In the control, Pxn (A) and GFP (A′) are restricted to the cortical zone (periphery). By contrast, knock down of six candidate genes causes extensive expression of Pxn (B–G) and Hml (Hml > GFP) (B′–G′) throughout the lymph gland, indicating a loss of progenitors in these genetic backgrounds. The combined Pxn and Hml expression patterns for each genetic background are shown (MERGE, A″–G″). DNA (blue) is stained to mark nuclei.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. RNAi lines causing an expanded Peroxidasin expression phenotype when expressed in progenitor cells using dome-gal4.

Screening with dome-gal4 (Jung et al., 2005) to target RNAi to the progenitor cells identified eleven genes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A–L), three of which (Transportin, Noa36, and Rrp40) are in common with those identified using Hml-gal4. By contrast, use of Antennapedia-gal4 (Antp-gal4) (Mandal et al., 2007) to target RNAi specifically to niche cells failed to identify any of the 21 lines as additional niche signaling components (not shown). Lastly, seven of the 21 RNAi lines did not cause a phenotype when expressed with any of the zone-specific Gal4 driver lines used. Taken together, our screen identified three genes, CTPsyn, bip1, and Nup98, which cause a loss of lymph gland progenitor cells upon RNAi knock down in differentiating cells, but not in progenitor cells or in niche cells. As described below, it was ultimately possible to connect two of these genes, bip1 and Nup98, to the equilibrium signaling pathway through the control of Pvr expression.

The bip1 gene functions in differentiating cells to regulate progenitor maintenance

The bip1 gene was originally identified through a yeast two-hybrid screen that showed that its encoded protein binds the BTB/POZ domain of the transcription factor Bric à brac 1 (Bab1) (Pointud et al., 2001), a protein that has several developmental roles including the formation of ovarian terminal filament cells that are required for germline stem cell maintenance (Lin and Spradling, 1993; Sahut-Barnola et al., 1995; Couderc et al., 2002). Analysis of the predicted Bip1 amino acid sequence (InterPro) (Hunter et al., 2012) identifies a THAP domain containing a C2CH-type zinc finger motif that is known to bind DNA (Sabogal et al., 2010).

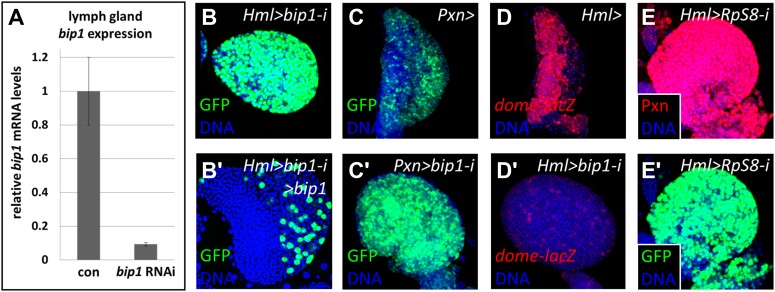

As no known bip1 mutants exist, several different approaches were used to validate the bip1 RNAi results and elucidate the function of the bip1 gene in differentiating the blood cells. First, qRT-PCR confirmed that bip1 is expressed in the lymph gland and demonstrated that the bip1 RNAi line (NIG 7574R-2) actually targets bip1 transcripts. Indeed, RNAi knock down of bip1 using Hml-gal4 (Sinenko and Mathey-Prevot, 2004; Jung et al., 2005) reduces bip1 mRNA levels in the lymph gland to approximately ten percent of that observed in controls (Figure 5A). The bip1 RNAi blood phenotype is also suppressible by the simultaneous overexpression of bip1 (UAS-bip1LA645; Figure 5B–B'), demonstrating the specific requirement for bip1 in maintaining progenitors. Driving bip1 RNAi with Pxn-gal4, an alternative differentiating- and mature-cell driver to Hml-gal4, also causes the loss of progenitor cells (Figure 5C–C′), thereby confirming that bip1 knock-down in differentiating cells is key to its associated phenotype. Additionally, the progenitor cell marker dome-MESO-lacZ (Hombria et al., 2005; Krzemien et al., 2007) is strongly reduced relative to control lymph glands (Figure 5D–D′) in the bip1 RNAi (Hml-gal4) background. This result confirms that progenitor cells fail to be maintained in bip1 RNAi lymph glands, rather than ectopically upregulating Pxn and Hml-gal4 expression.

Figure 5. Validation of the bip1 RNAi phenotype.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrates that bip1 is expressed in the lymph gland and that the RNAi line NIG 7574R-1 targeting bip1 indeed reduces bip1 transcript level when expressed using Hml-gal4. Hml-gal4 expresses GFP throughout the primary lobes in bip1 RNAi lymph glands (Hml > bip1-i, B), and this phenotype is suppressed by overexpression of bip1 (B′), restoring both the cortical and the medullary zones. (C–C′) Expression of bip1 RNAi using Pxn-gal4 phenocopies obtained with Hml-gal4, further supporting a cell-type-specific function of bip1. Expression of the progenitor cell marker dome-MESO-lacZ (D) is strongly reduced in bip1 RNAi lymph glands (D′), demonstrating that the gain in differentiation markers is due to the loss of progenitor cells that normally express dome-MESO-lacZ. RNAi knock down of RpS8, encoding a putative Bip1-interacting protein, causes the expansion of Pxn and Hml-gal4 expression throughout the lymph gland (E–E′), similar to that observed upon the loss of bip1.

Several ribosomal components, including Ribosomal protein S8 (RpS8), have been shown to associate with chromatin at active transcription sites and to associate with nascent transcripts to form ribonucleoprotein complexes (Brogna et al., 2002). Interestingly, RpS8 has also been identified in genomic-scale yeast two-hybrid analyses as a Bip1-interacting protein (Giot et al., 2003; Formstecher et al., 2005; Stark et al., 2006), which suggests that Bip1 and RpS8 may function together in vivo to regulate gene expression. Consistent with this idea, RNAi knockdown of RpS8 also causes the expanded expression of both Pxn and Hml-gal4 UAS-GFP expression throughout the lymph gland primary lobes (Figure 5E–E′). This result reflects a specific function of RpS8 in these cells because knockdown directly in niche or progenitor cells (using Antp-gal4 and dome-gal4, respectively) does not cause their loss to differentiation (not shown). Thus, RpS8 RNAi effectively phenocopies bip1 RNAi, as both cause a loss of progenitor cells when knocked down in differentiating cells. Collectively, these data support a model in which Bip1 functions along with RpS8 in a protein complex within differentiating cells to maintain multipotent lymph gland progenitors at later stages of development, consistent with a potential function in the equilibrium signaling pathway.

bip1 functions genetically upstream of the equilibrium signaling pathway

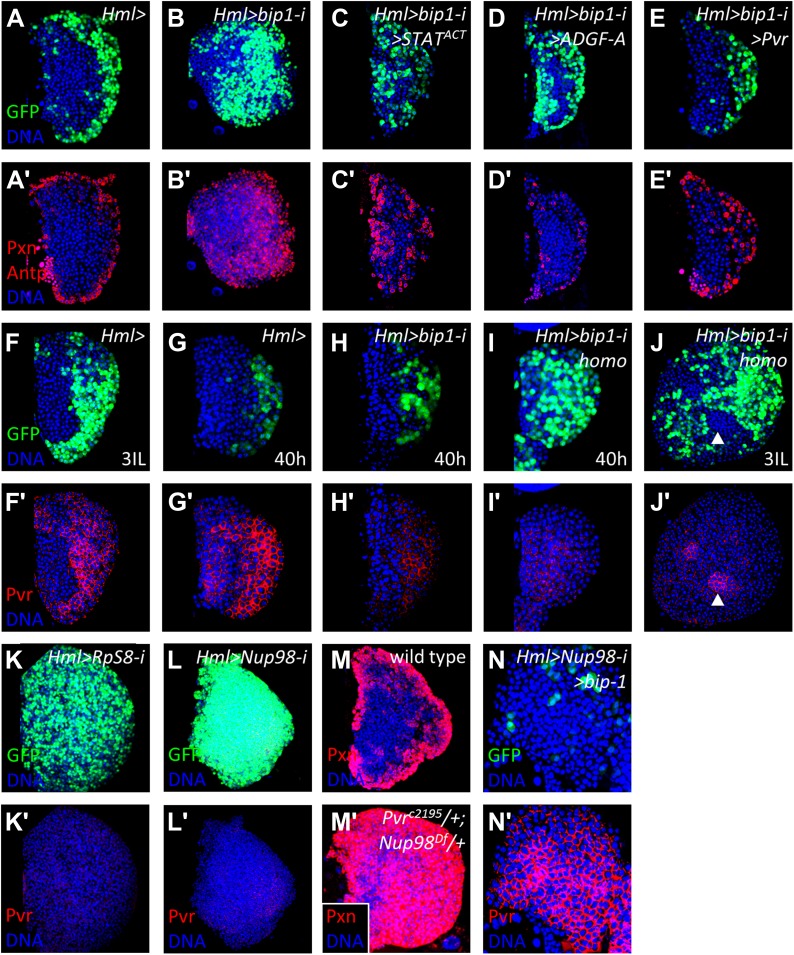

The progenitor maintenance function of Pvr signaling in differentiated cells requires the downstream function of the STAT transcriptional activator and the secreted enzyme ADGF-A (Mondal et al., 2011), and, consistent with this relationship, overexpression of either activated STAT (STATACT) (Ekas et al., 2010) or ADGF-A in differentiating cells can suppress the Pvr loss-of-function phenotype (Mondal et al., 2011). Likewise, we find that overexpression of STATACT or ADGF-A can suppress the bip1 RNAi phenotype (Figure 6A–D′). Furthermore, overexpression of Pvr also strongly suppresses the bip1 RNAi phenotype, returning lymph gland morphology and organization to essentially wild type (Figure 6E–E′). By contrast, overexpression of bip1 does not suppress the Pvr RNAi phenotype (Hml-gal4 UAS-Pvr RNAi UAS-bip1LA645; not shown). Collectively, these results place bip1 function genetically upstream of Pvr and other equilibrium signaling components in lymph gland progenitor maintenance by differentiating cells.

Figure 6. bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 control Pvr expression in the lymph gland.

Expression of bip1 RNAi in differentiating cells (Hml-gal4 or Hml>, B–B′) causes expansion of both Pxn and Hml-gal4 UAS-GFP throughout the lymph gland, as compared to controls (A–A′). Misexpression of either activated STAT (STATACT, C–C′), ADGF-A (D–D′), or Pvr (E–E′) partially (in the case of STAT activation or ADGF-A overexpression) or fully (in case of Pvr overexpression) suppresses this bip1 phenotype, suggesting that bip1 functions upstream of these genes. Expression of Pvr in control third-instar lymph glands (F–F′) and mid-second instar (40 hr post-hatching, G–G′). Reduced expression of Pvr is already apparent in bip1 RNAi lymph glands by 40 hr (H–H′), and this loss is even stronger in homozygous animals expressing higher levels of RNAi (I–I′); increased differentiation, based upon Hml-gal4 UAS-GFP expression, is also apparent (I). Strong suppression of Pvr is also observed in homozygous bip1 RNAi lymph glands (J–J′). RNAi knockdown of RpS8 also causes differentiation and the loss of Pvr expression (K–K′). Likewise, RNAi knockdown of Nup98 also causes differentiation and the loss of Pvr expression (L–L′). (M) Control background (Hml-gal4/+) showing normal expression of the differentiation marker Pxn in the cortical zone of the lymph gland. Progenitor cells in the MZ region are easily discerned by their lack of Pxn expression. By contrast, few progenitor cells (Pxn-negative cells) are observed in lymph glands when single-copy loss-of-function mutations of Pvr and Nup98 (PvrC2195/+; Nup98Df(3R)mbc-R1/+) are combined (M′), further indicating the close interaction between these genes. The middle-third (confocal z-stack) of the primary lobe is shown. Misexpression of bip1 in this background is sufficient to suppress these phenotypes and restore Pvr expression to the lymph gland (N–N′).

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. bip1 and RpS8 are required for normal Pvr transcript levels.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. Pvr expression is regulated autonomously by bip1, Nup98, and RpS8 within the lymph gland.

Figure 6—figure supplement 3. Loss of the nucleoporin Sec13 by RNAi neither causes a differentiation phenotype within the lymph gland nor the loss of Pvr expression.

Figure 6—figure supplement 4. Loss of Pvr expression is not a common feature of highly differentiated lymph glands.

Figure 6—figure supplement 5. Overexpression of bip1, Nup98, and RpS8, and RNAi knockdown of other nucleoporins does not affect Pvr levels in the lymph gland.

Bip1 and RpS8 control the equilibrium signaling pathway by regulating Pvr expression

The suppression of the bip1 RNAi phenotype by overexpression of Pvr suggested that bip1 may positively control Pvr expression during normal development. Indeed, a reduction in Pvr protein expression within the lymph gland is observed in the bip1 RNAi background by mid-second instar, soon after differentiation begins (∼40 hr post-hatching; Figure 6F–J′). This reduction in Pvr expression is even stronger (along with significantly increased differentiation, based upon Hml-gal4 expression) at the same developmental time point in larvae having two copies of Hml-gal4 UAS-bip1 RNAi (compare Figure 6I′ with Figure 6H′), further supporting the model that bip1 RNAi causes the loss of Pvr expression. By the late third instar (when the bip1 RNAi differentiation phenotype is most apparent), Pvr protein levels in the lymph gland remain strongly reduced (Figure 6J–J′).

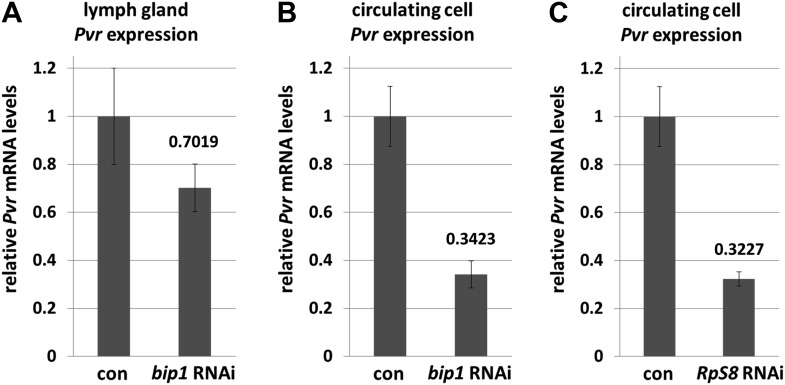

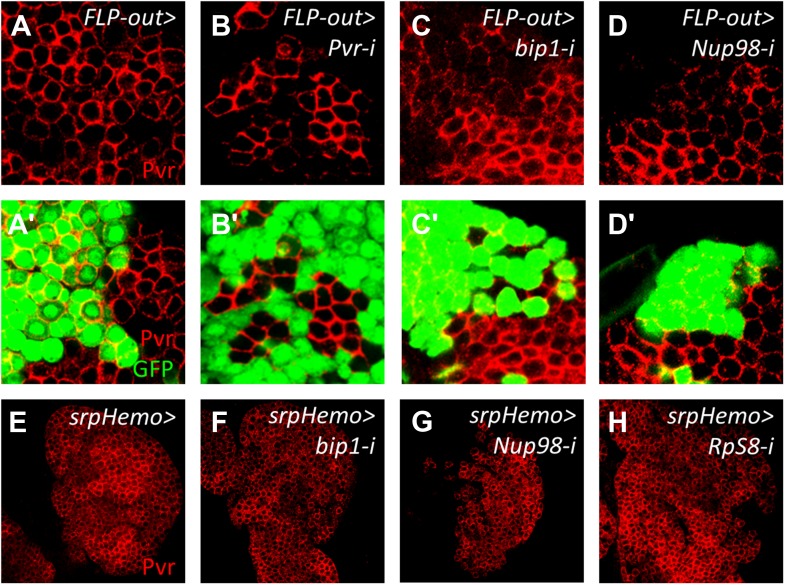

Knockdown of bip1 function in lymph glands by Hml-gal4-mediated RNAi reduces lymph gland Pvr transcript levels to approximately 70% of control levels (assessed by qRT-PCR; Figure 6—figure supplement 1A), consistent with the observed loss of Pvr protein (Figure 6H′–J′). However, because not all lymph gland cells express Hml (Hml-gal4), the actual reduction of Pvr transcript levels in cells expressing bip1 RNAi is likely to be greater than the observed total reduction. In support of this idea, bip1 RNAi in circulating blood cells (where greater than 90% express Hml-gal4) reduces Pvr transcript level to approximately 35% of the control level (Figure 6—figure supplement 1B). Expression of bip1 RNAi in FLP-out Gal4-expressing cell clones made exclusively in the lymph gland strongly reduces Pvr levels compared to nearby cells not expressing RNAi as well as to mock clones (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A–C), consistent with the autonomous regulation of Pvr by bip1 in the lymph gland. Furthermore, bip1 RNAi expression with srpHemo-gal4 (Bruckner et al., 2004), which expresses in a large fraction of circulating cells but in few or no cells within the lymph gland, does not reduce lymph gland Pvr levels (Figure 6—figure supplement 2E–H). Collectively, these data indicate that bip1 is required for proper Pvr protein expression, and therefore proper equilibrium signaling, within the developing lymph gland.

As described above, RpS8 is a putative Bip1-interacting protein in vivo and RpS8 RNAi in differentiating lymph gland cells, like bip1 RNAi, causes the loss of progenitor cells (Figure 5F–F′). This effect is likely due to the loss of equilibrium signaling during development since RpS8 RNAi also reduces Pvr protein expression in the lymph gland (Figure 6K–K′). Knockdown of RpS8 by RNAi, as with knockdown of bip1, also reduces Pvr transcript levels (Figure 6—figure supplement 1C). Interestingly, a Drosophila RNAi screen using the blood-related S2 cell line previously identified both Pvr and RpS8 as regulators of cell size and division (Sims et al., 2009). Although the relationship between Pvr and RpS8 was not explored, their results as well as ours are consistent with RpS8 having a regulatory role in Pvr expression in blood cells.

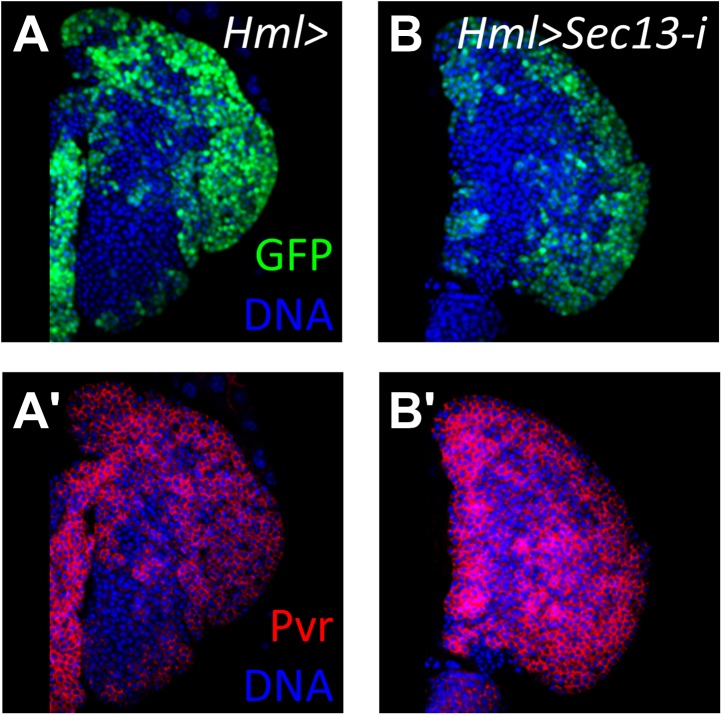

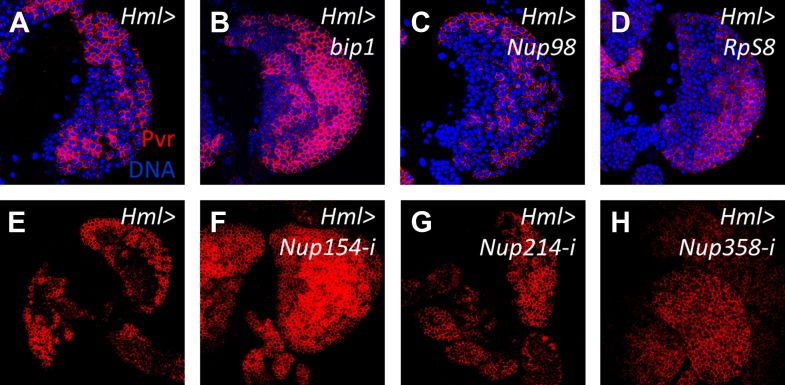

Nup98 also regulates Pvr expression

In addition to bip1, the screen described here identified Nup98 as a potential equilibrium signaling component because its knockdown in differentiating cells specifically causes a loss of progenitors cells (Figure 3T and Figure 4F–F′′). Although Nup98 is widely known as a general component of the nuclear pore complex, recent work has demonstrated that Nup98 and other nuclear pore components such as Sec13 and Nup88, can regulate gene expression through the binding of target promoters (Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2013). Moreover, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments identified bip1, RpS8, and the equilibrium signaling genes Pvr and STAT (STAT92E) as in vivo Nup98 regulatory targets (Capelson et al., 2010). Consistent with a function in regulation of equilibrium signaling genes, Nup98 knockdown specifically in differentiating cells of lymph glands causes a strong reduction in Pvr expression (Figure 6L–L′). By contrast, RNAi knockdown of the nucleoporin Sec13 in differentiating cells has no effect on the maintenance of progenitor cells or Pvr expression (Figure 6—figure supplement 3) underscoring the specific role of Nup98 in Pvr expression control. Furthermore, the close genetic relationship between Nup98 and Pvr is illustrated by the fact that single-copy loss of these genes in combination causes extensive loss of progenitor cells to differentiation (Figure 6M–M′). Interestingly, overexpression of bip1 in Nup98 RNAi lymph glands (Hml-gal4 UAS-Nup98 RNAi UAS-bip1LA645) is sufficient to restore Pvr protein expression and to suppress the loss of progenitors to differentiation (based upon lymph gland morphology and Hml-gal4 expression; Figure 6N–N′).

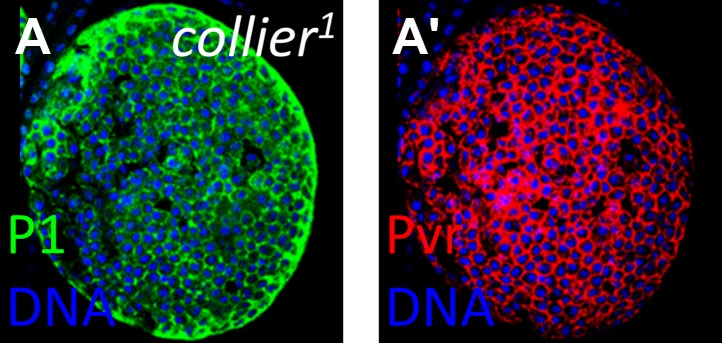

As has been shown, knockdown of bip1, Nup98, or RpS8 in differentiating cells each causes a strong reduction in Pvr expression in the lymph gland. Our interpretation of this common phenotype is that each gene works in the equilibrium signaling pathway to control Pvr expression, although an alternative hypothesis is that the loss of Pvr expression is a common feature of highly differentiated lymph glands and is not specifically related to the function of these genes. To test this, Pvr expression was examined in collier (col) mutant lymph glands, which lack niche signaling and are strongly differentiated by late larval stages (Crozatier et al., 2004; Mandal et al., 2007), and was found to be normal (Figure 6—figure supplement 4, compare with Pvr expression in wild-type cortical zone differentiating cells in Figure 6F′). Thus, Pvr requires bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 for proper developmental expression in the lymph gland.

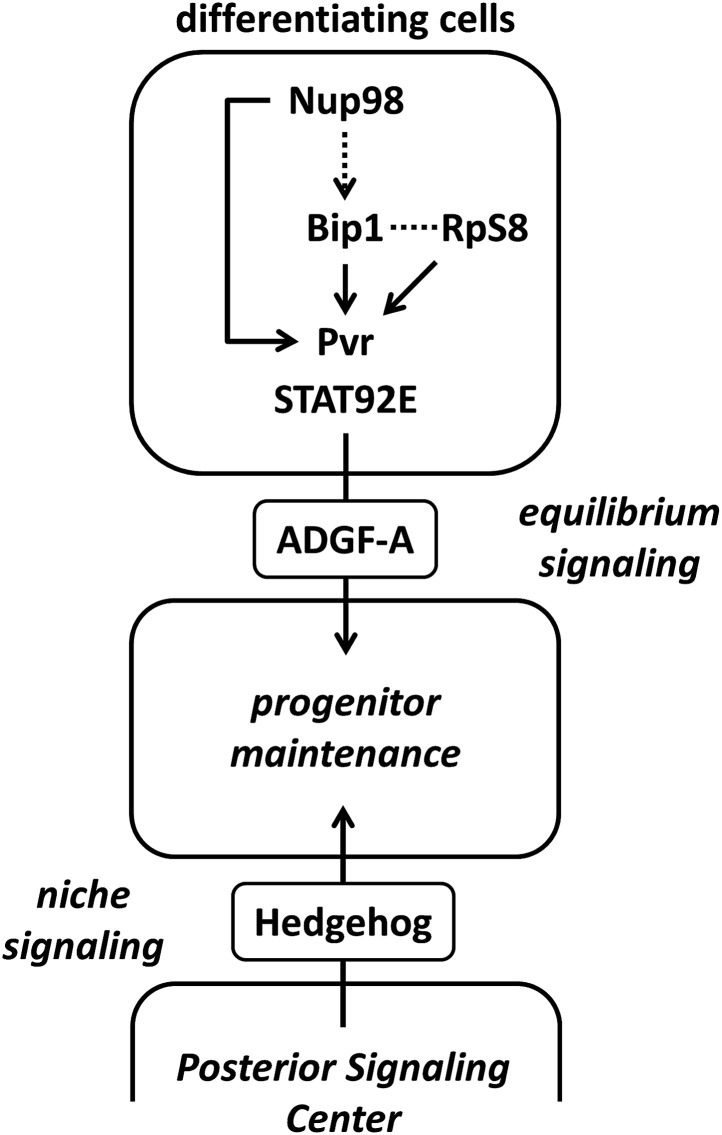

Several genetic screens, including overexpression and enhancer/suppressor screens of mutant or tumor phenotypes, have been conducted in the fly hematopoietic system (Milchanowski et al., 2004; Zettervall et al., 2004; Stofanko et al., 2008; Avet-Rochex et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2012; Tokusumi et al., 2012); however, the screen described here represents the first loss-of-function screen targeting normal developmental mechanisms throughout the lymph gland. This was accomplished with the development and use of the pan-lymph gland expression tool HHLT-gal4 to drive UAS-mediated RNAi, which identified 20 different candidate genes that cause a loss of progenitor cells when knocked down within the lymph gland. From subsequent analyses using lymph gland zone-restricted Gal4 driver lines, we arrive at a model (Figure 7) in which Bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 are required in differentiating blood cells upstream of Pvr to control its expression and function in the equilibrium signaling pathway that maintains blood progenitors within the lymph gland. Future analyses will be required to identify additional components of this important signaling pathway and to provide more information about how equilibrium signaling interacts with other pathways in the control of blood cell progenitor maintenance, cell fate specification, and proliferation.

Figure 7. Schematic of the equilibrium signaling pathway demonstrating the proposed roles of Bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 in controlling Pvr.

Bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 are independently required for the expression of Pvr (direct arrows). Rescue of endogenous Pvr expression by misexpression of bip1 in the Nup98 RNAi background indicates that bip1 functions genetically downstream of Nup98 (dashed arrow) in the control of Pvr expression. Bip1 and RpS8 may work together in a complex (dashed line) to control Pvr expression in vivo. These components collectively comprise the known equilibrium signaling pathway working within the lymph gland to promote progenitor cell maintenance, along with the previously known Hh niche signaling mechanism.

The Pvr receptor, with its numerous developmental roles, is arguably one of the most important members of the Drosophila RTK family, yet most of what is known about Pvr stems from analyses of how it works in the context of intracellular signaling. Little is known about how Pvr gene or protein expression is regulated. Importantly, the work described here sheds new light upon this issue by demonstrating a role for bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 in the regulation of Pvr expression. Our data and that of others suggest that this regulation of Pvr is likely taking place at the gene level, although other mechanisms are also possible. Ribosomes are required for protein translation, however specific ribosomal components or subunits may selectively stabilize transcripts and/or mediate preferential translation (Xue and Barna, 2012), while nucleoporins control both nuclear entry of regulatory proteins and the exit of mRNAs to the cytoplasm, and specific subcomponents are known to exhibit differential functions in this regard (Strambio-De-Castillia et al., 2010). Thus, RpS8 and Nup98 may selectively affect Pvr expression post-transcriptionally through transcript stabilization, transport, and translation. Although the specific mechanisms of molecular control of Pvr expression by bip1, RpS8, and Nup98 remain to be determined, their function is clearly critical in mediating proper equilibrium signaling and, therefore, proper blood progenitor maintenance within the lymph gland. The finding that bip1 regulates Pvr expression in the context of hematopoietic equilibrium signaling represents the first functional association for bip1 in Drosophila. The predicted Bip1 protein exhibits only one recognizable structural sequence, namely a THAP domain that contains a putative DNA-binding zinc finger motif. Our results suggest that Bip1 behaves as a positive regulator of Pvr transcription, but whether this occurs directly through Bip1 interaction with the Pvr locus will require further investigation.

Understanding how progenitor cell maintenance and homeostasis is controlled over developmental time is crucial for understanding normal cellular and tissue dynamics, especially in the context of ageing or disease. The identification of Bip1 and Nup98 as regulators of hematopoietic progenitors in Drosophila may be indicative of important conserved functions of related proteins within the vertebrate blood lineages similar to what has been shown previously for GATA, FOG, and RUNX factors (Waltzer et al., 2010). THAP-domain proteins are conserved across species and have been reported to have a variety of important functions in mammalian systems, including maintenance of murine embryonic stem cell pluripotency (Cayrol et al., 2007; Dejosez et al., 2008, 2010). What role, if any, THAP-domain proteins have in vertebrate blood progenitor maintenance (or hematopoiesis in general) remains to be established. Likewise, Nup98 has not been implicated in any normal hematopoietic role despite being a well-studied protein in other contexts.

With regard to the diseased state, mutations in the human THAP1 gene have been associated with dystonia (Fuchs et al., 2009; Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2009; Kaiser et al., 2010; Mazars et al., 2010), a neuromuscular disorder that causes repetitive, involuntary muscular contraction, and THAP1/Par4 protein complexes have been shown to promote apoptosis in leukemic blood cells in various experimental contexts in vitro (Lu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). Chromosomal translocations that generate Nup98 fusion proteins have been implicated in numerous human myelodysplastic syndromes and leukemias (Nishiyama et al., 1999; Ahuja et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2005; Nakamura, 2005; van Zutven et al., 2006; Slape et al., 2008; Kaltenbach et al., 2010; Murayama et al., 2013), further underscoring the need to explore Nup98 function in the hematopoietic system. Therefore, the study of bip1 and Nup98 in Drosophila, a powerful molecular genetic system, will likely be of benefit to understand the function of related vertebrate genes in normal and disease contexts.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

Misexpression P{Mae-UAS.6.11} inserts (LA lines) were obtained from John Merriam, UCLA (Los Angeles, California). UAS-RNAi lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC, Vienna, Austria), the National Institute of Genetics (NIG, Kyoto, Japan), and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (TRiP lines, BDSC, Bloomington, Indiana). The lines UAS-FLP.JD1, UAS-2XEGFP, P{GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S, UAS-human RafACT, Df(3R)mbc-R1, UAS-RpS8PD01446, and w1118 (BDSC 5905) were from the BDSC. Pvrc02195 was from Exelixis (available from BDSC, obtained from D Montell). HmlΔ-gal4 UAS-2XEGFP (S Sinenko), Antp-gal4/TM6B Tb (S Cohen), P{ubi-gal80 ts}10; Antp-gal4/TM6B Tb (this lab), domeless-gal4 UAS-2XEYFP/FM7i (this lab), UAS-DAlkACT (R Palmer), dome-MESO-lacZ (S Brown), Pxn-gal4 (M Galko), UAS-STATACT (E Bach), UAS-ADGF-A (T Dolezal), collier1; P(col5-cDNA)/CyO-TM6B, Tb (M Crozatier), srpHemo-gal4 (K Brückner), and Hand-gal4 (Z Han) have been previously described.

HHLT-gal4 construction and whole animal screening

Second chromosome inserts of Hand-gal4, HmlΔ-gal4, UAS-FLP.JD1, and UAS-2XEGFP were recombined onto a single chromosome and placed with P{GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S on Chromosome 3. Because Gal4 reporter lines with specific, pan-lymph gland expression are unknown, we took advantage of a FLP-out lineage tracing approach that we have used previously to perpetually mark lymph gland cells (Jung et al., 2005; Evans et al., 2009). The Hand-gal4 reporter reflects the expression of the Hand gene, which is expressed in the cardiogenic mesoderm, from which the lymph gland is derived. Within the lymph gland, Hand-gal4 is expressed from the late embryo through the first larval instar but then is downregulated (Han and Olson, 2005). Using Hand-gal4 in conjunction with UAS-FLP and a FLP-out Gal4-expressing line (P{GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S) (Pignoni and Zipursky, 1997), lymph gland cells are perpetually with EGFP throughout all subsequent developmental stages. To express EGFP in circulating cells, we used Hemolectin-gal4 (HmlΔ-gal4) (Sinenko and Mathey-Prevot, 2004), which is specific to mature blood cells both in circulation and in the lymph gland cortical zone (Jung et al., 2005). HHLT-gal4 expression is easily detectable in lymph glands and circulating cells of whole animals throughout larval development. Due to the embryonic activity of Hand-gal4, HHLT-gal4 also labels dorsal vessel cardioblasts and pericardial cells, although by late larval stages the expression of EGFP in the former is almost undetectable.

HHLT-gal4 virgins were crossed to males from individual LA lines, RNAi lines, or w1118 as a control. All crosses were reared at 29°C to maximize Gal4 activity. Wandering third-instar larvae from control and experimental crosses were collected, washed with water, and placed in glass spot wells (Fisher) on ice to minimize movement. Animals were scored visually using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 compound fluorescence microscope. Non-screen images of HHLT > GFP larvae were collected with a Zeiss SteREO Lumar fluorescence microscope. Images were collected using either an AxioCam HRc or HRm camera with AxioVision software.

Tissue dissection and antibody staining and analysis

Lymph glands were dissected and processed as previously described (Jung et al., 2005). Briefly, lymph glands were dissecting from third-instar larvae in 1× PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde/1× PBS for 30 min, washed three times in 1×PBS with 0.4% Triton-X (1× PBST) for 15 min each, blocked in 10% normal goat serum/1× PBST for 30 min, followed by incubation with primary antibodies in block. Primary antibodies were incubated with tissue overnight at 4°C and then washed three times in 1× PBST for 15 min each, reblocked for 15 min, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 3 hr at room temperature. Samples were washed three times in 1× PBST, with TO-PRO-3 iodide (diluted 1:1000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) added to the last wash to stain nuclei. Samples were washed briefly with 1× PBS to remove excess TO-PRO-3 and detergent prior to mounting on glass slides in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California). Mouse anti-Peroxidasin was a kind gift from John and Lisa Fessler (UCLA) and was used at 1:1500 dilution. Rat anti-Pvr was a kind gift from Benny Shilo and was used at 1:400 dilution. Secondary Cy3-labeled antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, Pennsylvania) and used at 1:500 dilution.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Lymph glands from 50 third-instar larvae were isolated by dissection. For fat body analysis, ten third-instar larvae were used. RNA was extracted from these tissues with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland). Relative quantitative RT-PCR (comparative CT) was performed using Power SYBR Green RNA-to-CT 1-step kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, California) and a StepOne Real-Time PCR detection thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) using primers specific for Pvr, bip1, and rp49. Primer sequences are: Pvr(forward), 5′-TTCGGATTTCGATGGTGAAT-3′; Pvr(reverse), 5′-CGGACACTAAGCTGGTCGAT-3′; bip1(forward), 5′-CGGAGTTTATGGACAGCACA-3′; bip1(reverse), 5′-CCTTAGCAGGAGGAGGAGGT-3′; rp49(forward), 5′-GCTAAGCTGTCGCACAAATG-3′; rp49(reverse), 5′-GTTCGATCCGTAACCGATGT-3′.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amir Yavari, Julia Manasson, Tanya Hioe, Sean Mofidi, Jesse Zaretsky, and Tina Muhkerjee for assistance generating the HHLT-gal4 line and with various aspects of the screen. We thank John Merriam (UCLA) for use of the LA lines and John and Lisa Fessler (UCLA) for the kind gift of anti-Pxn antibodies. Lastly, we thank Ira Clark, John Merriam, and members of the Banerjee Lab for discussion of the project and comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute FundRef identification ID: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/100000050 R01 HL067395 to Utpal Banerjee.

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine FundRef identification ID: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/100000900 TG2-01169 to Jiwon Shim.

Additional information

Competing interests

UB: Reviewing editor, eLife.

The other authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

BCM, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

JS, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

CJE, Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

UB, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

Additional files

Genes and phenotypes associated with P{Mae-UAS.6.11} LA insertion lines expressed with HHLT-gal4. Screen and line identifiers are shown along with the predicted misexpressed gene and the associated whole-animal lymph gland and circulating cell phenotype.

Genes and phenotypes associated with UAS-RNAi lines expressed with HHLT-gal4. Screen and line identifiers are shown along with the targeted gene for knockdown by RNAi, the associated whole-animal lymph gland phenotype based upon GFP expression, and the Peroxidasin (Pxn) expression phenotype of dissected lymph glands.

References

- Ahuja HG, Popplewell L, Tcheurekdjian L, Slovak ML. 2001. NUP98 gene rearrangements and the clonal evolution of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 30:410–415. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asha H, Nagy I, Kovacs G, Stetson D, Ando I, Dearolf CR. 2003. Analysis of Ras-induced overproliferation in Drosophila hemocytes. Genetics 163:203–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avet-Rochex A, Boyer K, Polesello C, Gobert V, Osman D, Roch F, Augé B, Zanet J, Haenlin M, Waltzer L. 2010. An in vivo RNA interference screen identifies gene networks controlling Drosophila melanogaster blood cell homeostasis. BMC Developmental Biology 10:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen HJ, Levis RW, Liao G, He Y, Carlson JW, Tsang G, Evans-Holm M, Hiesinger PR, Schulze KL, Rubin GM, Hoskins RA, Spradling AC. 2004. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics 167:761–781. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogna S, Sato TA, Rosbash M. 2002. Ribosome components are associated with sites of transcription. Molecular Cell 10:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00565-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner K, Kockel L, Duchek P, Luque CM, Rorth P, Perrimon N. 2004. The PDGF/VEGF receptor controls blood cell survival in Drosophila. Developmental Cell 7:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson M, Liang Y, Schulte R, Mair W, Wagner U, Hetzer MW. 2010. Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell 140:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol C, Lacroix C, Mathe C, Ecochard V, Ceribelli M, Loreau E, Lazar V, Dessen P, Mantovani R, Aguilar L, Girard JP. 2007. The THAP-zinc finger protein THAP1 regulates endothelial cell proliferation through modulation of pRB/E2F cell-cycle target genes. Blood 109:584–594. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-012013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couderc JL, Godt D, Zollman S, Chen J, Li M, Tiong S, Cramton SE, Sahut-Barnola I, Laski FA. 2002. The bric a brac locus consists of two paralogous genes encoding BTB/POZ domain proteins and acts as a homeotic and morphogenetic regulator of imaginal development in Drosophila. Development 129:2419–2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp J, Merriam J. 1997. Efficiency of an F1 selection screen in a pilot two-component mutagenesis involving Drosophila melanogaster misexpression phenotypes. Drosophila Information Service 80:90–92 [Google Scholar]

- Crozatier M, Ubeda JM, Vincent A, Meister M. 2004. Cellular immune response to parasitization in Drosophila requires the EBF orthologue collier. PLOS Biology 2:E196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejosez M, Krumenacker JS, Zitur LJ, Passeri M, Chu LF, Songyang Z, Thomson JA, Zwaka TP. 2008. Ronin is essential for embryogenesis and the pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell 133:1162–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejosez M, Levine SS, Frampton GM, Whyte WA, Stratton SA, Barton MC, Gunaratne PH, Young RA, Zwaka TP. 2010. Ronin/Hcf-1 binds to a hyperconserved enhancer element and regulates genes involved in the growth of embryonic stem cells. Genes & Development 24:1479–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1935210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal T, Dolezelova E, Zurovec M, Bryant PJ. 2005. A role for adenosine deaminase in Drosophila larval development. PLOS Biology 3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragojlovic-Munther M, Martinez-Agosto JA. 2012. Multifaceted roles of PTEN and TSC orchestrate growth and differentiation of Drosophila blood progenitors. Development 139:3752–3763. doi: 10.1242/dev.074203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas LA, Cardozo TJ, Flaherty MS, McMillan EA, Gonsalves FC, Bach EA. 2010. Characterization of a dominant-active STAT that promotes tumorigenesis in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 344:621–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ, Olson JM, Ngo KT, Kim E, Lee NE, Kuoy E, Patananan AN, Sitz D, Tran P, Do MT, Yackle K, Cespedes A, Hartenstein V, Call GB, Banerjee U. 2009. G-TRACE: rapid Gal4-based cell lineage analysis in Drosophila. Nature Methods 6:603–605. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formstecher E, Aresta S, Collura V, Hamburger A, Meil A, Trehin A, Reverdy C, Betin V, Maire S, Brun C, Jacq B, Arpin M, Bellaiche Y, Bellusci S, Benaroch P, Bornens M, Chanet R, Chavrier P, Delattre O, Doye V, Fehon R, Faye G, Galli T, Girault JA, Goud B, de Gunzburg J, Johannes L, Junier MP, Mirouse V, Mukherjee A, Papadopoulo D, Perez F, Plessis A, Rossé C, Saule S, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Vincent A, White M, Legrain P, Wojcik J, Camonis J, Daviet L. 2005. Protein interaction mapping: a Drosophila case study. Genome Research 15:376–384. doi: 10.1101/gr.2659105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. 2007. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death and Differentiation 14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs T, Gavarini S, Saunders-Pullman R, Raymond D, Ehrlich ME, Bressman SB, Ozelius LJ. 2009. Mutations in the THAP1 gene are responsible for DYT6 primary torsion dystonia. Nature Genetics 41:286–288. doi: 10.1038/ng.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot L, Bader JS, Brouwer C, Chaudhuri A, Kuang B, Li Y, Hao YL, Ooi CE, Godwin B, Vitols E, Vijayadamodar G, Pochart P, Machineni H, Welsh M, Kong Y, Zerhusen B, Malcolm R, Varrone Z, Collis A, Minto M, Burgess S, McDaniel L, Stimpson E, Spriggs F, Williams J, Neurath K, Ioime N, Agee M, Voss E, Furtak K, Renzulli R, Aanensen N, Carrolla S, Bickelhaupt E, Lazovatsky Y, DaSilva A, Zhong J, Stanyon CA, Finley RL, Jnr, White KP, Braverman M, Jarvie T, Gold S, Leach M, Knight J, Shimkets RA, McKenna MP, Chant J, Rothberg JM. 2003. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Olson EN. 2005. Hand is a direct target of Tinman and GATA factors during Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development 132:3525–3536. doi: 10.1242/dev.01899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombria JC, Brown S, Hader S, Zeidler MP. 2005. Characterisation of Upd2, a Drosophila JAK/STAT pathway ligand. Developmental Biology 288:420–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S, Jones P, Mitchell A, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bateman A, Bernard T, Binns D, Bork P, Burge S, de Castro E, Coggill P, Corbett M, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Fraser M, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Madera M, Maslen J, McAnulla C, McDowall J, McMenamin C, Mi H, Mutowo-Muellenet P, Mulder N, Natale D, Orengo C, Pesseat S, Punta M, Quinn AF, Rivoire C, Sangrador-Vegas A, Selengut JD, Sigrist CJ, Scheremetjew M, Tate J, Thimmajanarthanan M, Thomas PD, Wu CH, Yeats C, Yong SY. 2012. InterPro in 2011: new developments in the family and domain prediction database. Nucleic Acids Research 40:D306–D312. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SH, Evans CJ, Uemura C, Banerjee U. 2005. The Drosophila lymph gland as a developmental model of hematopoiesis. Development 132:2521–2533. doi: 10.1242/dev.01837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser FJ, Osmanoric A, Rakovic A, Erogullari A, Uflacker N, Braunholz D, Lohnau T, Orolicki S, Albrecht M, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Klein C, Lohmann K. 2010. The dystonia gene DYT1 is repressed by the transcription factor THAP1 (DYT6). Annals of Neurology 68:554–559. doi: 10.1002/ana.22157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach S, Soler G, Barin C, Gervais C, Bernard OA, Penard-Lacronique V, Romana SP. 2010. NUP98-MLL fusion in human acute myeloblastic leukemia. Blood 116:2332–2335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. 2010. Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell 140:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzemien J, Dubois L, Makki R, Meister M, Vincent A, Crozatier M. 2007. Control of blood cell homeostasis in Drosophila larvae by the posterior signalling centre. Nature 446:325–328. doi: 10.1038/nature05650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanot R, Zachary D, Holder F, Meister M. 2001. Postembryonic hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 230:243–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebestky T, Chang T, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. 2000. Specification of Drosophila hematopoietic lineage by conserved transcription factors. Science 288:146–149. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebestky T, Jung SH, Banerjee U. 2003. A Serrate-expressing signaling center controls Drosophila hematopoiesis. Genes & Development 17:348–353. doi: 10.1101/gad.1052803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Franks TM, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, Hetzer MW. 2013. Dynamic association of NUP98 with the human genome. PLOS Genetics 9:e1003308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Spradling AC. 1993. Germline stem cell division and egg chamber development in transplanted Drosophila germaria. Developmental Biology 159:140–152. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YW, Slape C, Zhang Z, Aplan PD. 2005. NUP98-HOXD13 transgenic mice develop a highly penetrant, severe myelodysplastic syndrome that progresses to acute leukemia. Blood 106:287–295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Li JY, Ge Z, Zhang L, Zhou GP. 2013. Par-4/THAP1 complex and Notch3 competitively regulated pre-mRNA splicing of CCAR1 and affected inversely the survival of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Oncogene 32:5602–5613. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhijani K, Alexander B, Tanaka T, Rulifson E, Bruckner K. 2011. The peripheral nervous system supports blood cell homing and survival in the Drosophila larva. Development 138:5379–5391. doi: 10.1242/dev.067322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal L, Martinez-Agosto JA, Evans CJ, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. 2007. A Hedgehog- and Antennapedia-dependent niche maintains Drosophila haematopoietic precursors. Nature 446:320–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus R, Laurinyecz B, Kurucz E, Honti V, Bajusz I, Sipos B, Somogyi K, Kronhamn J, Hultmark D, Andó I. 2009. Sessile hemocytes as a hematopoietic compartment in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 106:4805–4809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801766106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Agosto JA, Mikkola HK, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. 2007. The hematopoietic stem cell and its niche: a comparative view. Genes & Development 21:3044–3060. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazars R, Gonzalez-de-Peredo A, Cayrol C, Lavigne AC, Vogel JL, Ortega N, Lacroix C, Gautier V, Huet G, Ray A, Monsarrat B, Kristie TM, Girard JP. 2010. The THAP-zinc finger protein THAP1 associates with coactivator HCF-1 and O-GlcNAc transferase: a link between DYT6 and DYT3 dystonias. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285:13364–13371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milchanowski AB, Henkenius AL, Narayanan M, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. 2004. Identification and characterization of genes involved in embryonic crystal cell formation during Drosophila hematopoiesis. Genetics 168:325–339. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal BC, Mukherjee T, Mandal L, Evans CJ, Sinenko SA, Martinez-Agosto JA, Banerjee U. 2011. Interaction between differentiating cell- and niche-derived signals in hematopoietic progenitor maintenance. Cell 147:1589–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee T, Kim WS, Mandal L, Banerjee U. 2011. Interaction between Notch and Hif-alpha in development and survival of Drosophila blood cells. Science 332:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1199643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama H, Matsushita H, Ando K. 2013. Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia harboring NUP98-HOXA9. International Journal of Hematology 98:143–144. doi: 10.1007/s12185-013-1381-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T. 2005. NUP98 fusion in human leukemia: dysregulation of the nuclear pore and homeodomain proteins. International Journal of Hematology 82:21–27. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.04160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RE, Fessler LI, Takagi Y, Blumberg B, Keene DR, Olson PF, Parker CG, Fessler JH. 1994. Peroxidasin: a novel enzyme-matrix protein of Drosophila development. The EMBO Journal 13:3438–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Arai Y, Tsunematsu Y, Kobayashi H, Asami K, Yabe M, Kato S, Oda M, Eguchi H, Ohki M, Kaneko Y. 1999. 11p15 translocations involving the NUP98 gene in childhood therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 26:215–220. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199911)26:33.0.CO;2-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. 2009. Reactive oxygen species prime Drosophila haematopoietic progenitors for differentiation. Nature 461:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature08313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C, Ruiz-Martinez J, Ruibal M, Mok KY, Indakoetxea B, Gorostidi A, Martí Massó JF. 2009. Identification of a novel THAP1 mutation at R29 amino-acid residue in sporadic patients with early-onset dystonia. Movement Disorders 24:2428–2429. doi: 10.1002/mds.22849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott BB, Chiang Y, Hudson A, Sarkar A, Guichet A, Schulz C. 2011. Nucleoporin98-96 function is required for transit amplification divisions in the germ line of Drosophila melanogaster. PLOS ONE 6:e25087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennetier D, Oyallon J, Morin-Poulard I, Dejean S, Vincent A, Crozatier M. 2012. Size control of the Drosophila hematopoietic niche by bone morphogenetic protein signaling reveals parallels with mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 109:3389–3394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109407109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F, Zipursky SL. 1997. Induction of Drosophila eye development by decapentaplegic. Development 124:271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointud JC, Larsson J, Dastugue B, Couderc JL. 2001. The BTB/POZ domain of the regulatory proteins Bric a brac 1 (BAB1) and Bric a brac 2 (BAB2) interacts with the novel Drosophila TAF(II) factor BIP2/dTAF(II)155. Developmental Biology 237:368–380. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizki TM. 1978. The circulatory system and associated cells and tissues. In: The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. Ashburner M, Wright TRF, Editors. New York, London: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal A, Lyubimov AY, Corn JE, Berger JM, Rio DC. 2010. THAP proteins target specific DNA sites through bipartite recognition of adjacent major and minor grooves. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 17:117–123. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahut-Barnola I, Godt D, Laski FA, Couderc JL. 1995. Drosophila ovary morphogenesis: analysis of terminal filament formation and identification of a gene required for this process. Developmental Biology 170:127–135. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth S, Brito R, Mukherjea D, Rybak LP, Ramkumar V. 2014. Adenosine receptors: expression, function and regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15:2024–2052. doi: 10.3390/ijms15022024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J, Mukherjee T, Banerjee U. 2012. Direct sensing of systemic and nutritional signals by haematopoietic progenitors in Drosophila. Nature Cell Biology 14:394–400. doi: 10.1038/ncb2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha R, Gateff E. 1982. Ultrastructure and cytochemistry of the cell types of the larval hematopoietic organs and hemolymph of Drosophila melanogaster. Development, Growth & Differentiation 24:65–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1982.00065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims D, Duchek P, Baum B. 2009. PDGF/VEGF signaling controls cell size in Drosophila. Genome Biology 10:R20. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-r20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinenko SA, Mathey-Prevot B. 2004. Increased expression of Drosophila tetraspanin, Tsp68C, suppresses the abnormal proliferation of ytr-deficient and Ras/Raf-activated hemocytes. Oncogene 23:9120–9128. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinenko SA, Mandal L, Martinez-Agosto JA, Banerjee U. 2009. Dual role of wingless signaling in stem-like hematopoietic precursor maintenance in Drosophila. Developmental Cell 16:756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinenko SA, Shim J, Banerjee U. 2012. Oxidative stress in the haematopoietic niche regulates the cellular immune response in Drosophila. EMBO Reports 13:83–89. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slape C, Lin YW, Hartung H, Zhang Z, Wolff L, Aplan PD. 2008. NUP98-HOX translocations lead to myelodysplastic syndrome in mice and men. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs 64–68. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Reguly T, Boucher L, Breitkreutz A, Tyers M. 2006. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Research 34:D535–D539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt N, Molitor A, Somogyi K, Mata J, Curado S, Eulenberg K, Meise M, Siegmund T, Häder T, Hilfiker A, Brönner G, Ephrussi A, Rørth P, Cohen SM, Fellert S, Chung HR, Piepenburg O, Schäfer U, Jäckle H, Vorbrüggen G. 2005. Gain-of-function screen for genes that affect Drosophila muscle pattern formation. PLOS Genetics 1:e55. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stofanko M, Kwon SY, Badenhorst P. 2008. A misexpression screen to identify regulators of Drosophila larval hemocyte development. Genetics 180:253–267. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strambio-De-Castillia C, Niepel M, Rout MP. 2010. The nuclear pore complex: bridging nuclear transport and gene regulation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 11:490–501. doi: 10.1038/nrm2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KL, Goh SC, Minakhina S. 2012. Genetic screen for regulators of lymph gland homeostasis and hemocyte maturation in Drosophila. G3 2:393–405. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U, Fessler LI, Aziz A, Hartenstein V. 1994. Embryonic origin of hemocytes and their relationship to cell death in Drosophila. Development 120:1829–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokusumi T, Tokusumi Y, Hopkins DW, Shoue DA, Corona L, Schulz RA. 2011. Germ line differentiation factor Bag of Marbles is a regulator of hematopoietic progenitor maintenance during Drosophila hematopoiesis. Development 138:3879–3884. doi: 10.1242/dev.069336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokusumi Y, Tokusumi T, Shoue DA, Schulz RA. 2012. Gene regulatory networks controlling hematopoietic progenitor niche cell production and differentiation in the Drosophila lymph gland. PLOS ONE 7:e41604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zutven LJ, Onen E, Velthuizen SC, van Drunen E, von Bergh AR, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Veronese A, Mecucci C, Negrini M, de Greef GE, Beverloo HB. 2006. Identification of NUP98 abnormalities in acute leukemia: JARID1A (12p13) as a new partner gene. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 45:437–446. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltzer L, Gobert V, Osman D, Haenlin M. 2010. Transcription factor interplay during Drosophila haematopoiesis. The International Journal of Developmental Biology 54:1107–1115. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.093054lw [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S, Barna M. 2012. Specialized ribosomes: a new frontier in gene regulation and organismal biology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 13:355–369. doi: 10.1038/nrm3359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettervall CJ, Anderl I, Williams MJ, Palmer R, Kurucz E, Ando I, Hultmark D. 2004. A directed screen for genes involved in Drosophila blood cell activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 101:14192–14197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403789101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Xu HG, Lu C. 2014. A novel long non-coding RNA T-ALL-R-LncR1 knockdown and Par-4 cooperate to induce cellular apoptosis in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia & Lymphoma 55:1373–1382. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.829574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]