The extracellular matrix (ECM) is an intricate network composed of an array of multidomain macromolecules organized in a cell/tissue-specific manner. Components of the ECM link together to form a structurally stable composite, contributing to the mechanical properties of tissues. The ECM is also a reservoir of growth factors and bioactive molecules. It is a highly dynamic entity that is of vital importance, determining and controlling the most fundamental behaviors and characteristics of cells such as proliferation, adhesion, migration, polarity, differentiation, and apoptosis.1,2

Major ECM elements

The “core matrisome”3 comprises approximately 300 proteins. Major components include collagens, proteoglycans, elastin, and cell-binding glycoproteins, each with distinct physical and biochemical properties.

Collagen is composed of 3 polypeptide α chains that form a triple helical structure. In vertebrates, 46 distinct collagen chains assemble to form 28 collagen types2,4 that are categorized into fibril-forming collagens (e.g., types I, II, III), network-forming collagens (e.g., the basement membrane collagen type IV), fibril-associated collagens with interruptions in their triple helices, or FACITs (e.g., types IX, XII), and others (e.g., type VI). The fibril-forming collagens contain continuous triple-helix-forming domains flanked by amino- and carboxyl-terminal noncollagenous domains. These noncollagenous domains are proteolytically removed and triple helices formed are associated laterally into fibrils. Nonfibril supramolecular structures, such as the networks of collagen IV in basement membranes and beaded filaments, are formed by nonfibrillar collagens. The FACITs do not assemble into fibrils by themselves, but are associated with collagen fibrils.

Specific proline residues in collagens are hydroxylated by prolyl 4-hydroxylase and prolyl 3-hydroxylase. Selected lysine residues are also hydroxylated by lysyl hydroxylase. The fibrillar procollagens, following processing, are secreted into the extracellular space where their propeptides are removed. The resulting collagens then assemble into fibrils via covalent cross-links formed between lysine residues of two collagen chains by a process catalyzed by extracellular enzyme lysyl oxidases (LOX). The collagenous backbone dictates the tissue architecture, shape, and organization.

Proteoglycans consist of a core protein to which glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains are attached. GAGs are linear, anionic polysaccharides made up of repeating disaccharide units. There are four groups of GAGs: hyaluronic acid, keratan sulfate; chondroitin/dermatan sulfate; and heparan sulfate, including heparin. All except hyaluronic acid are sulfated. The highly negatively charged GAG chains allow the proteoglycans to sequester water and divalent cations, conferring space-filling and lubrication functions. Secreted proteoglycans include large proteoglycans, such as aggrecan and versican, small leucine-rich proteoglycans, such as decorin and lumican, and basement membrane proteoglycans, such as perlecan. Syndecans are cell-surface-associated whereas serglycin is an intracellular proteoglycan. The molecular diversity of proteoglycans provides structural basis for a multitude of biological functions. For instance, aggrecan in cartilage generates elasticity and high biomechanical resistance to pressure. Decorin and lumican have a regulatory role in collagen fibril assembly. Proteoglycans also interact with growth factors and growth factor receptors, and are implicated in cell signaling5 and biological processes, including angiogenesis.

The laminin family comprises about 20 glycoproteins that are assembled into a cross-linked web, interwoven with the type IV collagen network in basement membranes. They are heterotrimers (400–800 kDa) consisting of one α, one β, and one γ chain. In vertebrates, five α, three β, and three γ chains have been identified. Many laminins self-assemble to form networks that remain in close association with cells through interactions with cell surface receptors. Laminins are essential for early embryonic development and organogenesis.6

Fibronectin is critical for the attachment and migration of cells, functioning as “biological glue”. The fibronectin monomer (~250 kDa) is made of subunits which comprise three types of repeats: I, II, and III. Fibronectin is secreted as dimers linked by disulfide bonds and has binding sites to other fibronectin dimers, collagen, heparin, and cell surface receptors. In the FNIII10 repeat, there is an important Arg-Gly-Asp cell-binding site. The fibronectin dimers can form multimers. With continued deposition, the fibrils are lengthened and thickened and the fibronectin fibrils can be further processed into a deoxycholate-insoluble matrix.7

Elastin imparts elasticity to tissue subjected to repeated stretch, such as vascular vessels and the lung. It is encoded by a single gene in mammals and is secreted as a 60–70 kDa tropoelastin monomer. Tropoelastin, with the assistance of fibulins, associates with microfibrils to form elastic fibers. All tropoelastins share a characteristic domain arrangement of hydrophobic sequences alternating with lysine-containing cross-linking motifs. Microfibrillar proteins fibrillins and microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1 interact directly with elastin and are important for its nucleation and assembly.2 A crucial feature of the elastic fiber, critical to its proper function, is the extensive cross-linking of tropoelastin mediated by LOX, which oxidizes selective lysine residues in peptide linkage to allysine. There are two major bifunctional cross-links in elastin: dehydrolysinonorleucine, formed through the condensation of one residue of allysine and one of lysine, and allysine aldol, formed through the association of two allysine residues. These two cross-links can further condense with each other, or with other intermediates, to form desmosine or isodesmosine. Electron microscopy and imaging studies show that tropoelastin is assembled into small globular aggregates on the cell surface (microassembly). The cross-linking begins which results in a loss of positive charges on the molecule, enabling the release of tropoelastin from the cell and assisting globular fusion in the presence of microfibrils (macroassembly). Fibulin-4 has a role in early stages of elastin assembly and fibulin-5 acts to bridge elastin between the matrix and cells.8

Cellular receptors for ECM molecules

ECM molecules connect to the cells through integrins, syndecans, and other receptors. Integrins are heterodimeric receptors composed of α and β subunits.9 In vertebrates, the family encompasses 18 α and 8 β subunits that can assemble into 24 different integrins. Both α and β subunits are transmembrane proteins with large modular extracellular domains, single transmembrane helices, and short cytoplasmic regions that mediate cytoskeletal interactions. The integrins can be grouped into subgroups based on ligand-binding properties or based on their subunit composition. Major matrix-binding integrins are the β1 integrins with affinity to fibronectin, collagens, and laminins.

Integrins function as links between the ECM and the cytoskeleton. Activation of integrins by matrix ligands leads to conformational changes in the integrins, exposing their cytoplasmic domains to binding of focal complex proteins such as the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and integrin–linked kinase (ILK). Clustering of integrins in the membrane follows, and intracellular proteins including vinculin and talin along with actin stress fibers are assembled into focal adhesion complexes. The integrins subsequently trigger phosphorylation cascades and initiate signaling events including Rho and MAP kinase pathways to affect cell proliferation, differentiation, polarity, contractility, and gene expression in the so-called “outside-in” signaling process. Conversely, intracellular signals from proteins such as FAK, ILK and talin can induce changes in integrin conformation and activation that alter its ligand binding activity in the “inside-out” signaling fashion. Integrins thus act as a bi-directional conduit, transmitting signals and providing connections between intra- and extra-cellular compartments.10,11

ECM remodeling and modulation

The ECM is constantly undergoing remodeling whereby its components are deposited, degraded, or modified. Intermolecular cross-linking by LOX is a key posttranslational modification for collagens and elastin. Expanded cross-linking due to excess LOX activity increases tissue tensile strength and matrix stiffness, affecting thereby cellular behaviors.

Collagens and other ECM elements are substrates for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a disintegrin and metalloproteases (ADAMs), ADAM with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS), as well as proteases such as cathepsin G and elastase.1 MMPs are produced in precursor forms and remain inactive until activated. Most of the 23 members of the MMP family are secreted, but there are also membrane type MMPs. Their activities are counteracted by tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs) and other inhibitors, and an imbalance may lead to tissue fibrosis and diseases.1 Besides ECM molecules, MMPs and others can also cleave precursor proteins, release ECM-bound growth factors, and release from ECM proteins bioactive fragments with new bioactivities, such as endostatin.4

In addition to the turnover process, the ECM is also modulated by exogenous stimuli such as cytokines, glucocorticoids, oxidative stress, pressure and mechanical stretch. The most studied cytokine is transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which is known to enhance ECM production and upregulate ECM-related genes.

ECM as reservoir for bioactive molecules

The ECM has the capacity to store and sequester growth factors and cytokines, establishing concentration gradients and regulating spatially and temporally their bioavailability. In particular, the fibroblast growth factor family strongly binds to heparan sulfate chains of proteoglycans such as perlecan. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are also involved in binding, transporting, and activating developmental control factors including Wnt factors and hedgehog. The ECM is furthermore a reservoir of bioactive fragments released upon limited proteolysis. These fragments, with biological properties and activities of their own, regulate physiological and pathological processes including angiogenesis. The ECM can additionally participate in ligand maturation. TGF-β, secreted in latent form, is stored in the ECM and remains inactive until activated by MMP-dependent proteolysis.1

ECM provides chemical and physical cues

The biochemical properties of the ECM allow cells to sense and interact with their extracellular environment using various signal transduction pathways. The chemical cues are provided by ECM components, especially the adhesive proteins such as fibronectin, integrin and non-integrin receptors, as well as growth factors and associated signaling molecules. Interactions with different matrices via specific sets of receptors can trigger distinct cellular responses.10,11

The ECM functions as a physical barrier, an anchorage site, or a movement track for cell migration.1 The physical properties of the ECM, including its rigidity, density, porosity, insolubility and topography (spatial arrangement and orientation), provide physical cues to the cells. The mechanical properties are essentially sensed by integrins that connect extracellular ECM to the actin cytoskeleton inside the cells. Stiff matrices induce integrin clustering, robust focal adhesions, Rho and MAP kinase activation, leading to increased proliferation and contractility.1 Matrix rigidity also regulates differentiation. For example, on soft matrices, mesenchymal stem cells favor a neurogenic path, and on stiff ones they favor an osteogenic path.

Concluding remarks

The ECM provides a structural scaffold via a network of protein–protein and protein–proteoglycan interactions. These interactions are involved in the formation of supramolecular assemblies such as collagen fibrils and elastic fibers, in tissue architecture, and in cell-matrix interactions that regulate cell growth and behavior.

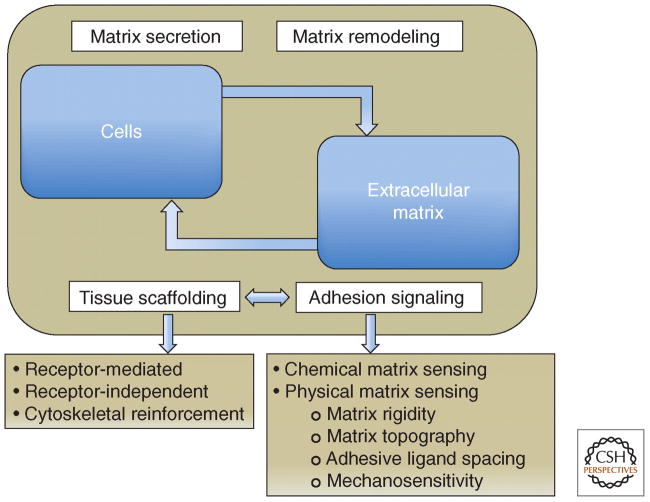

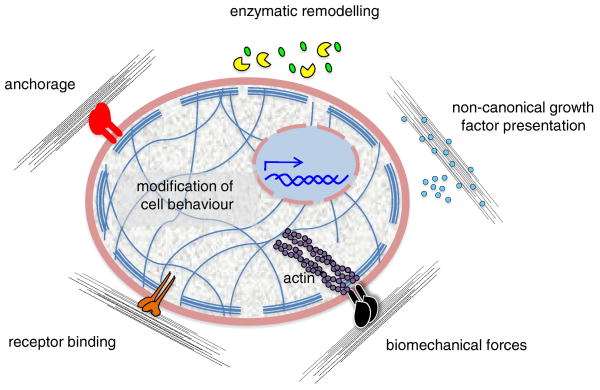

The cells and the ECM have a two-way reciprocal relationship (Fig. 1).10,12 Cells produce, secrete, deposit, and remodel ECM to mediate ECM composition and topography. The ECM in turn transmits signals through ECM receptors to influence cell characteristics and activities (Fig. 2).13 Such a feedback mechanism is essential for rapid response of cells to surrounding environmental changes.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration highlighting the dynamic cross-talk between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM). Cells secrete and remodel the ECM, and the ECM contributes to the assembly of individual cells into tissues, affecting this process at both receptor and cytoskeletal levels. Adhesion-mediated signaling, based on the cells’ capacity to sense the chemical and physical properties of the matrix, affects both global cell physiology and local molecular scaffolding of the adhesion sites. The molecular interactions within the adhesion site stimulate, in turn, the signaling process, by clustering together the structural and signaling components of the adhesome. (From Geiger B, Yamada KM. Molecular architecture and function of matrix adhesions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011;3:a005033. Copyright 2014 Cold Spring Harbor.)

Figure 2.

Regulation of cell behavior by ECM. The effects exerted on cells by ECM can be differently mediated. The ECM can directly bind different types of cell surface receptors or co-receptors (red, orange, black), thus mediating cell anchorage and regulating several pathways involved in intracellular signaling and mechanotransduction. Moreover, the ECM can act by noncanonical growth factor (cyan) presentation and be remodeled by the action of enzymes (yellow pie), which can release functional fragments (green). (From Gattazzo F, Urciulo A, Bonaldo P. Extracellular matrix: A dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1840:2506–2519. Copyright 2014 Elsevier.)

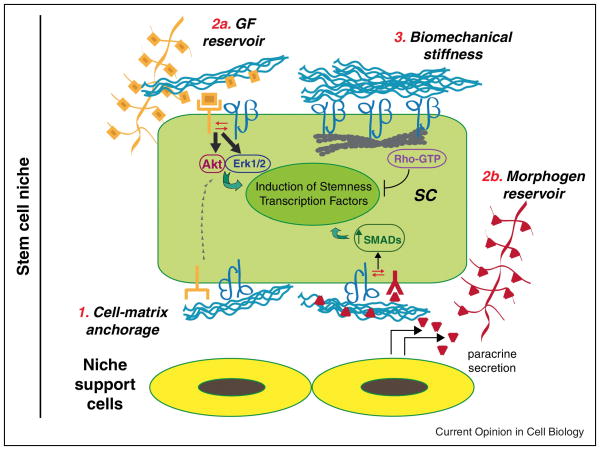

The multi-functional ECM is now recognized as a “niche” for stem cells (Fig. 3).13,14 ECM biology also has wide implications in areas ranging from embryonic development, wound healing, fibrosis, cancer invasion and metastasis, diabetes, eye diseases including exfoliation syndrome, to biomedical engineering.

Figure 3.

Hypothetical model of ECM, integrins and transmembrane receptors crosstalk in the stem cell niche. ECM/integrin interaction within the stem cell niche contributes to three main functions: (1) Cell-matrix anchorage, in which integrin-mediated cell adhesion physically anchors the stem cell to ECM proteins. Through these mechanisms, growth factor receptors can be activated by an integrin-dependent mechanism as well. (2) Reservoir for growth factors and morphogens: ECM binding of soluble growth factors and morphogens spatially and temporally controls their interactions with transmembrane receptors. Integrin crosstalk with other receptors regulates signaling (Erk1/2, Akt, SMADs) preserving stemness. (3) Biomechanical stiffness. ECM/integrin interaction senses mechanical forces, leading to cytoskeleton re-organization and stem cell homeostasis.

, growth factors and their receptors;

, growth factors and their receptors;

, morphogens and their receptors;

, morphogens and their receptors;

, extracellular matrix;

, extracellular matrix;

, α and β integrin subunits;

, α and β integrin subunits;

, cytoskeletal filaments; SC: stem cell. (From Brizzi F, Tarone G, Defilippi P. Extracellular matrix, integrins, and growth factors as tailors of the stem cell niche. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2012;24:645–651. Copyright 2014 Elsevier.)

, cytoskeletal filaments; SC: stem cell. (From Brizzi F, Tarone G, Defilippi P. Extracellular matrix, integrins, and growth factors as tailors of the stem cell niche. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2012;24:645–651. Copyright 2014 Elsevier.)

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges support from the National Eye Institute (grant EY018828 and core grant EY01792), Bethesda, MD; the Cless Family Foundation, Northbrook, IL; and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Lu P, Takai K, Weaver VM, Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspec Biol. 2011;3:a005058. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mecham RO. Overview of extracellular matrix. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2012;57:10.1.1–10.1.16. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1001s57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hynes RO, Naba A. Overview of the matrisome - An inventory of extracellular matrix constituents and functions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a004903. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricard-Blum S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004978. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esko JD, Kimata K, Lindahl U. Proteoglycans and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, et al., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. 2. Chapter 16. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durbeej M. Laminins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:259–268. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarzbauer JE, DeSimone DW. Fibronectins, their fibrillogenesis and in vivo functions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005041. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozel BA, Mecham RP, Rosenbloom J. Elastin. In: Mecham RP, editor. The extracellular matrix: An Overview. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiger B, Yamada KM. Molecular architecture and function of matrix adhesions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005033. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfenson H, Levelin I, Geiger B. Dynamic regulation of the structure and functions of integrin adhesions. Dev Cell. 2013;11:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daley WP, Yamada KM. ECM-mediated cellular dynamics as a driving force for tissue morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gattazzo F, Urciuolo A, Bonaldo P. Extracellular matrix: A dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2506–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brizzi MF, Tarone G, Defilippi P. Extracellular matrix, integrins, and growth factors as tailors of the stem cell niche. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;24:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]