Abstract

This study investigates the coordination of boundary tones as a function of stress and pitch accent. Boundary tone coordination has not been experimentally investigated previously, and the effect of prominence on this coordination, and whether it is lexical (stress-driven) or phrasal (pitch accent-driven) in nature is unclear. We assess these issues using a variety of syntactic constructions to elicit different boundary tones in an Electromagnetic Articulography (EMA) study of Greek. The results indicate that the onset of boundary tones co-occurs with the articulatory target of the final vowel. This timing is further modified by stress, but not by pitch accent: boundary tones are initiated earlier in words with non-final stress than in words with final stress regardless of accentual status. Visual data inspection reveals that phrase-final words are followed by acoustic pauses during which specific articulatory postures occur. Additional analyses show that these postures reach their achievement point at a stable temporal distance from boundary tone onsets regardless of stress position. Based on these results and parallel findings on boundary lengthening reported elsewhere, a novel approach to prosody is proposed within the context of Articulatory Phonology: rather than seeing prosodic (lexical and phrasal) events as independent entities, a set of coordination relations between them is suggested. The implications of this account for prosodic architecture are discussed.

Keywords: Prosodic boundaries, boundary tones, tonal alignment, gestural coordination, pauses, Greek, Articulatory Phonology

1.0 Introduction

The current study aims to comprehensively examine the tonal events that mark major phrase boundaries, traditionally called boundary tones, by investigating their timing relationships to other prosodic and constriction events occurring at boundaries. These are the actions of the vocal tract that comprise the consonants and the vowels of the phrase-final syllable, and the last prominence-related prosodic events of the phrase, namely the lexical stress of the phrase-final word, and if that word is accented, its pitch accent as well.

Pitch accent and boundary tone are terms traditionally used in the literature of intonation corresponding to the modifications in pitch, namely falling and/or rising pitch movements (cf. Silverman, Beckman, Pitrelli, Ostendorf et al., 1992), that are associated with words under phrasal prominence and words adjacent to major phrase boundaries respectively. According to the predominant approach, namely the Auto-segmental Metrical model of Phonology (e.g., Beckman & Pierrehumbert, 1986; Pierrehumbert, 1980; Pierrehumbert & Beckman, 1988), prosody is organized as a hierarchical structure. Pitch patterns marking prominence and boundaries are represented in this structure as phonological targets, specifically either single low (L) or high (H) tones or combinations of these tones that the phonetic implementation module interprets, resulting in a relatively smooth F0 contour (the intonation of an utterance) (e.g., Beckman & Pierrehumbert, 1986; Hayes, 1989; Nespor & Vogel, 1986; Selkirk, 1984; for an overview see Shattuck-Hufnagel & Turk, 1996). These tones are integral to the definition of prosodic structure, which includes at least one minor (intermediate phrase) and one major (intonational phrase) phrasal level above the level of word, based on which three types of phrasal tones are proposed: (a) pitch accents, associated with the stressed syllable of prominent words, (b) phrase accents, associated with intermediate phrases, and (c) boundary tones, associated with intonational phrases. Phrase accents correspond to the pitch movements spanning from the nuclear accent, namely the last pitch accent of the phrase, to the boundary tone. Phrase accents and boundary tones are often referred to as edge tones, an umbrella term for tones associated with phrase boundaries, while pitch accents preceding the nuclear one are called pre-nuclear.

Although this work is presented within a different phonological framework, namely Articulatory Phonology (e.g., Browman & Goldstein 1986, 1992), presented in Section 1.2, the notion of hierarchical structure and the terms for prosodic levels (i.e., word, intermediate phrase, intonational phrase) and for phrasal tones (i.e., pre-nuclear pitch accent, nuclear pitch accent, phrase accent, boundary tone) introduced by Auto-segmental Metrical Phonology are adopted here for consistency. When new terms are introduced, an appropriate definition is provided.

The current study focuses on boundary tones, and addresses the following two questions:

How are boundary tones coordinated with constriction gestures, meaning the articulatory movements that compose the consonants and the vowels?

Does prominence influence this coordination, and if yes, is the effect driven by the lexical (stress) and/or phrasal (pitch accent) aspect of prominence?

This study also reports some observations on the articulatory aspects of grammatical pauses. This issue was not targeted by design. However, during the analysis of our data we noticed a high number of acoustic pauses between the utterance bearing the boundary tone in question and the following one, which, interestingly, involved similar vocal tract configurations among speakers. Post-hoc analyses of several aspects of the articulation during these pauses revealed consistent patterns that further corroborate the model developed in this study, and are thus presented here.

The significance of this work for boundary tone coordination is multi-layered. In addition to providing the first articulatory data investigating the coordination of constriction gestures with either boundary tones or phrase accents, and to being the first articulatory study of Greek prosody, the current study is also the first systematic investigation of prosodic relations at boundaries, disentangling the unclear role of lexical prominence from the role of phrasal prominence in the coordination of boundary tones. Previous research has primarily focused on pitch accents and phrase accents, and has not experimentally investigated boundary tones. There has been little work on the alignment of falling pitch movements, since most research has been conducted on rising pitch accents. Moreover research has mainly been conducted within the acoustic and not the articulatory domain.

In the remainder of the Introduction, Section 1.1 defines tone coordination, and highlights the role of pitch movement onsets and lexical stress in tone coordination; Section 1.2 briefly presents Articulatory Phonology, which is the theoretical framework adopted here; Section 1.3 summarizes the main prosodic properties of Greek, the language in question; and Section 1.4 specifies the hypotheses to be tested together with their expected outcomes.

1.1 The role of pitch movement onsets and lexical stress in tone coordination

By tone coordination we mean the timing of tonal events with landmarks in the articulation of consonants and vowels. This notion is similar to tonal alignment, a term that is more commonly used in the literature and usually refers to the timing of tones with acoustic landmarks of the segmental string. The overriding assumption is that F0 turning points (F0 maxima and minima) are lawfully timed with consonants and vowels, a hypothesis originally introduced with respect to acoustic landmarks by Ladd and colleagues (1999) within the framework of the Auto-segmental Metrical model of Phonology (Beckman & Pierrehumbert, 1986; Pierrehumbert, 1980; Pierrehumbert & Beckman, 1988). Lawful timing has a dual meaning, covering both the notion of stability and the notion of co-occurrence. In other words, two events are considered lawfully timed to each other if the temporal interval between the two is consistent, showing little variability, and/or they coincide in time.

Research on different tonal events in a variety of languages confirms the existence of systematic timing relationships between tones and segments. One of the first reported examples is the case of the rising pre-nuclear accents in Greek, the F0 minimum of which (i.e., the onset of the rising pitch movement) consistently occurs 5 milliseconds on average before the onset of the accented syllable, and its F0 peak (i.e., the offset of the rising pitch movement) within the post-accentual vowel, regardless of the structure of the accented syllable and its following syllable or the number of syllables within the accented word (Arvaniti, Ladd and Mennen, 1998, 2000). Further research confirms consistent timing of pitch accents with the accented or the immediately following syllable, and points to some factors, such as speech rate, syllable structure, and prosodic context, that potentially cause systematic changes to this timing (see Wichmann, House and Rietveld, 2000 for an overview). To mention some representative examples, pitch accents in American English (Silverman & Pierrehumbert, 1990; Steele, 1986), Peninsular Spanish (Prieto & Torreira, 2007), and German (Mücke et al., 2006) occur later with respect to their associated syllable/vowel as speech rate becomes faster; pitch accents in Neapolitan Italian (D’Imperio, Nguyen & Munhall, 2003), Egyptian Arabic (Hellmuth, 2006) and Catalan (Prieto, 2009) occur earlier in open syllables than in closed ones; and pitch accents in Mexican Spanish occur earlier as the accented syllable is closer to the right word boundary (Prieto, 2006). Importantly, these changes in timing concern the offset of the pitch movement that corresponds to the pitch accent, but not its onset, which, instead, tends to remain stably timed with the accented syllable regardless of the factor in question, and it usually roughly coincides with that syllable’s acoustic onset. Deviations from this norm are of course observed in cases in which systematic differences in tone coordination have contrastive function (see Prieto, D’Imperio and Gili Fivela, 2005 for an overview). However, in these cases, within each meaning, the timing of the pitch accent’s onset is stable. Another case that can marginally be considered an exception is the Greek rising pre-nuclear accents mentioned above. As stated earlier in this section, the onset of these pitch movements does not accurately occur with the acoustic onset of the accented syllable, but on average 5 milliseconds earlier. This is a marginal exception, since it is not clear whether the 5 milliseconds interval between the onset of the pitch accent and the onset of the accented syllable might not qualify instead as roughly synchronous. In addition, this is an acoustics-based finding, which might be interpreted differently if articulatory data were also taken into consideration.

While the onset of pitch movements corresponding to pitch accents presents stable timing patterns with the segmental string (certainly more stable timing than their offsets), the same stability does not seem to hold for edge tones unless the factor of prominence is taken under consideration. With respect to phrase accents – the pitch movements extending form the nuclear pitch accent to the boundary tone (cf. Beckman & Pierrehumbert, 1986) – the onset of their pitch movement is attracted towards the first metrically strong syllable after the nuclear pitch accent (Barnes, Shattuck-Hufnagel, Brugos & Veilleux, 2006; Lickley, Schepman & Ladd, 2005). As for boundary tones, there is no direct experimental data on the timing of the onset of their pitch movement. However, indirect conclusions may be drawn on the basis of findings on the timing of the offset of pitch movements corresponding to phrase accents, which by definition coincides with the onset of boundary tones. According to these findings, this offset may occur within different syllables depending on the language. For instance, it may occur within the last stressed syllable (e.g., Transylvanian Romanian) or within the ultimate (e.g., Cypriot Greek) or the penultimate (e.g., Transylvanian Hungarian) syllable of a phrase (Grice, Ladd & Arvaniti, 2000). Importantly, in Greek, which is a language in which phrase accents do not always end within the last stressed syllable of the phrase2, finer effects of lexical stress have been detected. Specifically, in Greek wh-questions (Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009) and yes-no questions with their nuclear accent falling in the phrase-final word (Arvaniti et al., 2006a), the offset of the pitch movement corresponding to the phrase accent occurs earlier within the phrase-final syllable in words with non-final stress than in words with final stress. The stress-driven adjustments on the timing of phrase-accents in Greek are accounted for differently. A perception-based account has been proposed for wh-questions (Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009) and a tonal crowding-based account for yes-no questions (Arvaniti et al., 2006a). There is little research in this matter, and similar fine effects of lexical stress on the offset of phrase accents may be found in other languages as well. On the basis of the effects of lexical stress on the timing of phrase accents, Grice and colleagues (2000) define phrase accents as edge tones with stress-seeking properties. These properties, and the findings on the offset of phrase accents mentioned above, can be assumed to extend to boundary tones, since the onset of pitch movement corresponding to the boundary tone coincides with the offset of the pitch movement corresponding to the phrase accent.

In conclusion, the onset of pitch accents is in a stable timing relationship with the segmental string, while the onset of edge tones seems to vary with the position of lexical stress. These observations in combination with the fact that pitch accents are hosted by lexically stressed syllables (cf. Beckman & Edwards, 1992) suggest: 1) that it is the onset of phrasal tones that defines their coordination with the segmental string, a point that corresponds well with the view in Articulatory Phonology (e.g., Browman & Goldstein 1986, 1992) that speech events are coordinated through their onsets (see Section 1.2 for more details); and 2) that lexical stress systematically affects this coordination by attracting phrasal tones. In the case of pitch accents, this effect is absolute, with the pitch accent co-occurring with lexical stress. The same holds for the boundary tones of those languages in which these tones are initiated within the last stressed syllable of the phrase (e.g., Transylvanian Romanian, see Grice et al., 2000)3. However, as exemplified above with the cases of Greek wh- and yes-no questions, a unified account for role of lexical stress on phrasal tone coordination that could also capture the finer effects of lexical stress on boundary tones observed in languages like Greek is lacking (see Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009; Arvaniti et al., 2006a). In addition, the contribution of the different aspects of prominence (i.e., lexical stress and pitch accent) to these effects is yet to be clarified. Based on these considerations, we use an Electromagnetic Articulography (EMA) study to address the coordination of boundary tones with constriction gestures in Greek. The investigation is thorough, focusing on the timing of the onset of both rising and falling boundary tones, elicited by a variety of syntactic constructions that permit direct comparison between accented and de-accented phrase-final words, allowing thus separation of the effects of phrasal prominence (pitch accent) from those of lexical prominence (lexical stress) on boundary tone coordination. We present the details of the specific hypotheses and predictions tested in Section 1.4, after we first briefly introduce Articulatory Phonology in Section 1.2 and Greek prosody in Section 1.3.

1.2 Articulatory Phonology

Within Articulatory Phonology (e.g., Browman & Goldstein 1986, 1992), phonology and phonetics are isomorphic, and their units, called gestures, are phonologically relevant events of the vocal tract. There are three types of gestures, namely constriction, tone and clock-slowing gestures. The remaining of this section defines the three types and outlines their similarities and differences.

1.2.1 Constriction gestures

Constriction gestures form or release constrictions in the vocal tract, and their presence, location and degree serve to contrast utterances. These gestures are specified for abstract linguistic tasks (e.g., lip closure for /p/) and are realized by coordinated actions of specific articulators (e.g., lips and jaw for the labial closure in /p/). They extend in space and time, and are triggered by internal oscillators that may be coupled to each other either in-phase (synchronously) or anti-phase (sequentially). The spatio-temporal and timing properties of the gestures composing a given utterance are specified at the gestural score of the utterance. As for in-phase and anti-phase coordination, the theoretical assumption is that these two types of coupling can account for syllabic structure (e.g., Browman & Goldstein, 1990a, 2000, Goldstein, Byrd & Saltzman, 2006):

The oscillator triggering the onset consonantal gesture (C gesture) is in-phase coordinated to the oscillator triggering the nucleus vocalic gesture (V gesture), and as a result the motion of the constrictor forming the onset consonant is initiated synchronously with motion of the constrictor forming the nucleus vowel.

The oscillator triggering the coda C gesture, on the other hand, is anti-phase coordinated with the oscillator triggering the V gesture, and consequently, the motion of the constrictor forming the coda consonant is initiated as the motion of the constrictor forming the vowel reaches its target.

Complex syllables involve competition between various coupling relations, known as the competitive coupling hypothesis (Browman & Goldstein, 2000). These assumptions are supported by experimental data (e.g., Marin & Pouplier, 2010), although both cross-linguistic differences and exceptions are observed (e.g., Nam, 2007; Nam, Goldstein & Saltzman, 2010). In onset consonant clusters, each of the C gesture oscillators is coupled in-phase with the V gesture oscillator, but anti-phase with its neighboring C gesture oscillators of the cluster. As a result, the C gestures of the onset cluster shift relative to the V gesture, so that the onset of the V gestures coincides with the middle point of all the C gestures combined. This phenomenon is known as the c-center effect (e.g., Browman & Goldstein, 1988, 2000; Byrd 1995). In the case of complex codas, competition between coupling relations is language-dependent; languages in which consonants are moraic do not present competition, whereas languages in which consonants are not moraic do (e.g., Nam, 2007; Nam et al., 2010). When no competition between coupling relations is involved, each of the coda C gesture oscillators is anti-phase coupled with each other, with the first of them being anti-phase coupled with the V gesture oscillator. Thus, in the non-competitive case, the V gesture and all the C gestures of the coda are sequentially coupled to each other.

1.2.2 Tone gestures

Tone gestures are similar to constriction gestures in that (1) they are specified for a linguistic task or goal, which is achieved via coordinated actions of specific articulators, (2) they evolve in time, and (3) they are coordinated with other gestures. However, tone gestures have different goals and involve a different set of articulators than the constriction gestures. The goal of tone gestures is to achieve linguistically relevant variations in the frequency of vibration of the vocal folds (cf. McGowan & Saltzman, 1995; see also Fougeron & Jun, 1998). There are two types of F0 goals, high (H) and low (L), which involve the coordination of the following articulators: the lungs, the trachea, the larynx, and a number of muscles, such as the thyroarytenoid, cricoarytenoid and cricothyroid muscles (see Hirose, 1999). Gao (2008), on the basis of experimental evidence from Mandarin Chinese, was the first to propose that tone gestures are coordinated with the constriction gestures of a syllable like any other consonantal gesture, i.e., in-phase with the V gesture and anti-phase with an onset C gestures, giving rise to a c-center effect. For instance, the mid point between the onset of the C and T gestures of Tones 1, 2 and 3 was found to co-occur with the onset of the V gesture, indicating that syllables with Tones 1, 2 and 3 and one onset consonant behave similarly to syllables with no lexical tone and two onset consonants. In parallel, there are experiment- and modeling-based examples in the literature suggesting that lexical tone gestures can also participate in syllabic coordinations like coda consonants (Hsieh 2011). In-phase and anti-phase coupling modes have also recently started to be used to account for pitch accents. To date, the only articulatory study concerns rising pitch accents in German and Catalan (cf. Mücke, Nam, Hermes & Goldstein, 2012; see also Prieto & Torreira, 2007). According to the proposed account, the H tone gesture is coupled in-phase with the accented V gesture and anti-phase with its preceding L tone gesture in both Catalan and German, the only difference being that in German, the L tone gesture is in-phase coupled with the accented V gesture as well. Hence, a tentative difference between lexical and phrasal tones arises. Contrary to lexical tones, pitch accents are not coupled to consonantal gestures, and are hence less tightly integrated into the coupling graph (i.e., the network of pair-wise phase relationships between oscillators) of a syllable, which is consistent with their status as post-lexical (cf. Mücke et al., 2012). Thus while lexical tone gestures, the constriction gestures forming a syllable and their timings are fixed in the lexicon, phrasal tones are not lexically specified. However, the model needs still to extend to phrasal tones other than pitch accents. Here, a model for boundary tones is discussed.

1.2.3 Clock-slowing gestures

Prosodic spatio-temporal effects (e.g., lengthening and strengthening) have been captured within Articulatory Phonology by means of clock-slowing gestures. These are different from constriction and tone gestures in that they are not related to specific articulators. Their main effect is to modulate the spatial and temporal properties of articulatory gestures that are active concurrently with them (e.g., Byrd & Saltzman, 2003). In particular, prosodic boundaries are instantiated by π-gestures, which locally slow down the clock that controls the speaker’s global speech pace. As a consequence of this slowing down, the constriction gestures that are co-active with the π-gestures become slower, and thus longer, larger and farther apart (Byrd & Saltzman, 2003). The π-gesture model has been extended to capture prosodic events other than boundaries, such as stress, by the means of a generalized class of clock-slowing, modulation, gestures, called μ-gestures (Saltzman, Nam, Krivokapić and Goldstein, 2008).

1.3 Greek prosody

This section summarizes the main prosodic properties of Greek (see Arvaniti, 2007 for an overview), the language examined here.

Lexical stress

All Greek words are lexically stressed. There are three possible positions for lexical stress: the antepenult, the penult and the ultima. The position of lexical stress is highly unpredictable and contrastive; it does not depend on phonological criteria, but is connected to morphological ones. This use of stress results in several minimal sets, as for example (adapted from Arvaniti, 2007):

[ti’lεfɔnɐ] “phones, n.” – [tilε’fɔnɐ] “call, 2nd person imp.” – [tilεfɔ’nɐ] “3rd person ind.”

Duration and amplitude have been described as the main phonetic correlates of Greek stress (for an overview of the stress correlates in Greek, the reader is referred to Arvaniti (2007) and references therein). In general, stressed vowels have been found to be 30–40% longer and to have higher amplitude than unstressed ones. The durational effect is observed in the overall duration of the syllable as well. Moreover, stressed vowels present higher F1, presumably due to hyperarticulation, and unstressed vowels are centralized, possibly because of their short duration.

Prosodic Phrasing

According to Arvaniti and Baltazani (2000, 2005), there are two prosodic levels above the phonological word level in Greek: intermediate phrases (ip) and intonational phrases (IP). The right edge of these two types of phrases is marked with phrase accents and boundary tones respectively, with the former being scaled lower than the latter. Finally, there is evidence of cumulative phrase-final lengthening in Greek (Kainada, 2007). In other words, phrase-final segments are longer when final at intonational phrases than at intermediate phrases, which are in turn longer than at prosodic word-final positions.

Tonal alignment

Turning first to Greek pitch accents, pre-nuclear pitch accents consist of a low and a high tonal target (L*+H), both of which, as mentioned in Section 1.1, present consistent alignment; the L is aligned with the accented syllable and the H with the syllable following the accented one (e.g., Arvaniti et al., 1998; Arvaniti et al., 2000; Baltazani 2006). Nuclear accents are either singleton tones (L* or H*) or bitonal tones (L+H* or H*+L). The F0 peaks of the H* and L+H* co-occur with the stressed vowel, while the F0 peak of the H*+L occurs just before the stressed syllable (Arvaniti & Baltazani, 2000, 2005; Arvaniti et al., 2006b). As for L*, its F0 minimum occurs in the stressed syllable of the focused word. If the focused word is not located phrase-finally, then L stretches to the last stressed syllable of the phrase (e.g., Arvaniti et al., 2006b). Phrase accents in Greek are either low (L-) or high (H-) tones (Arvaniti & Baltazani, 2005), and present stress-seeking properties discussed in more detail in Section 1.1 (see also Arvaniti et al., 2006a; Arvaniti et al., 2009; Grice et al., 2000). Finally, boundary tones are low (L%) or high (H%) tones (Arvaniti & Baltazani, 2005), the alignment of which has not been experimentally addressed.

1.4 Hypotheses and predictions

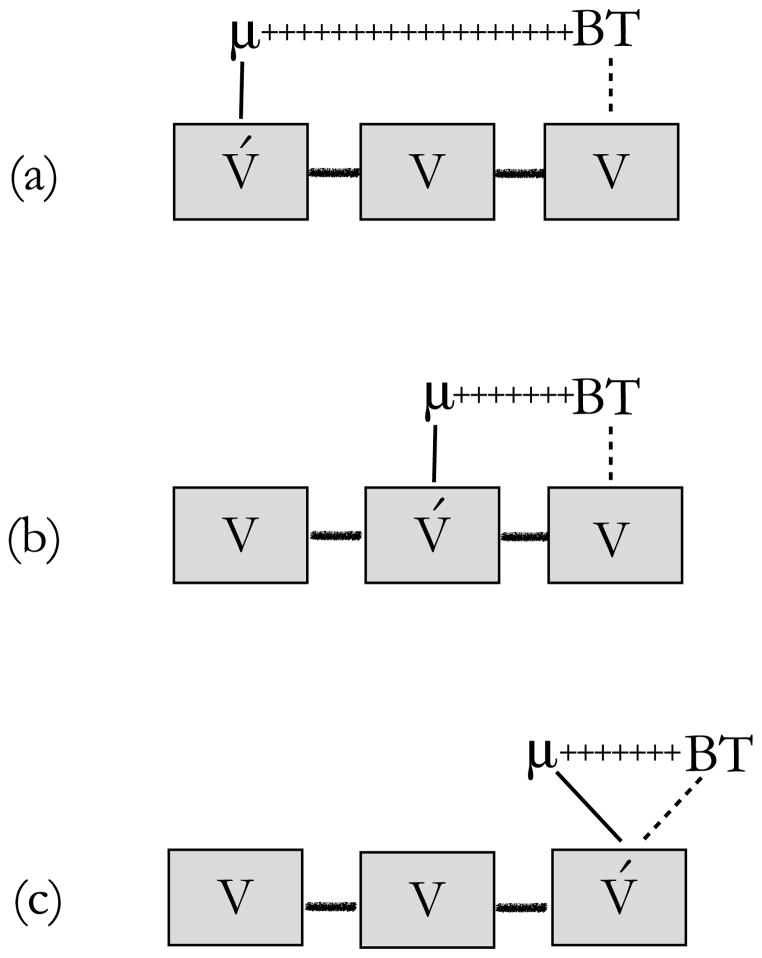

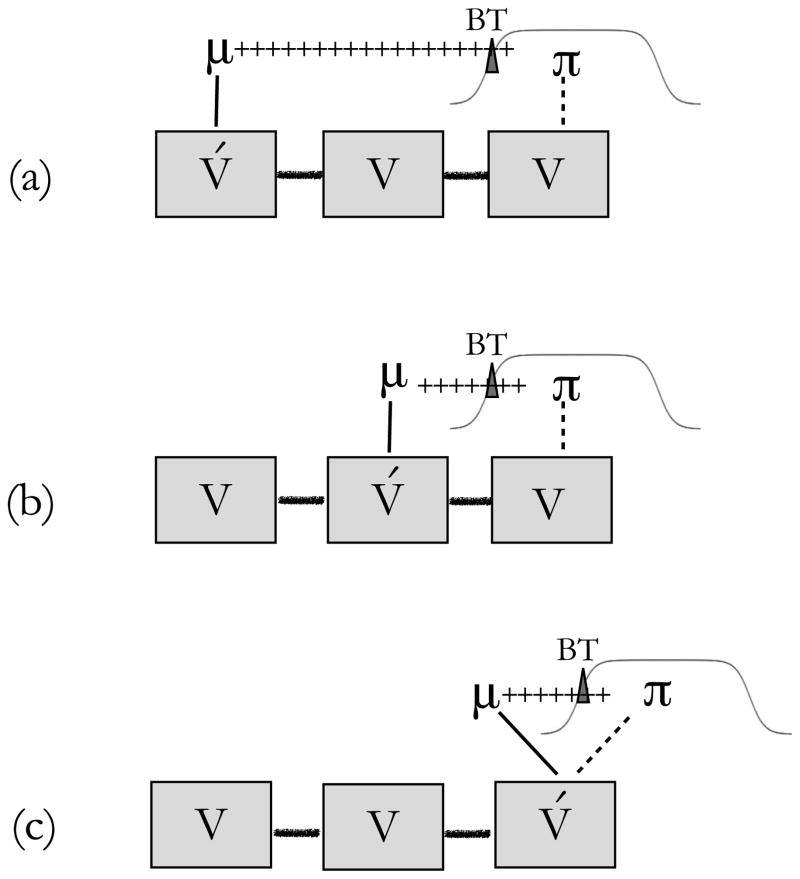

The goal of this study is to investigate the coordination of boundary tone (BT) gestures with constriction gestures in Greek, and how this coordination is influenced by the position of lexical stress and pitch accent.

It is predicted that BT gestures occur within the boundaries of phrase-final syllables. This prediction is grounded in the fact that Greek phrase accents are terminated within the phrase-final syllable (cf. Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009; Arvaniti et al., 2006a). Given that the offset of the phrase accent coincides with the onset of the boundary tone, the latter should be initiated within the phrase-final syllable as well.

Specifically, boundary tones are expected to be coordinated with the V gesture of the phrase-final syllable without affecting the coordination of the syllable’s constriction gestures to each other. This expectation is an extension of findings on the coordination of pitch accents (Mücke et al., 2012), the only other type of phrasal tone coordination with constriction gestures that has been addressed in the literature, according to which pitch accents, contrary to lexical tones (Gao, 2008), are coordinated with the V gesture of the accented syllable without presenting a c-center effect. This finding has been taken to mean that phrasal tones are not integrated in the coupling graph of the syllable. Since boundary tones are, like pitch accents, phrasal tones, they should not be integrated into the coupling graph of the syllable either, which in turn means that they should not affect inter-syllabic coordination relationships.

However, it is an empirical question whether the coordination of the BT gestures with the V gesture of the phrase-final syllable is in-phase or anti-phase. If the coordination between the BT gesture and the V gesture is in-phase, the two gestures should be initiated synchronously (cf. Mücke et al., 2012, where in-phase coordination between pitch accent gesture and V gesture is assumed); in case of anti-phase coordination, the BT gesture should be initiated as the V gesture reaches its target (cf. Hsieh (2011), where anti-phase coordination between lexical tone gesture and V gesture is proposed). In addition to these two types of coordination, we also consider possible alignment of the onset of the BT gesture with the peak velocity of the V gesture, based on findings indicating that peak velocity determines the occurrence of high (H) nuclear accents in Neapolitan Italian (D’Imperio, Espesser, Lœvenbruck et al., 2007). However, such a possibility is not predicted within Articulatory Phonology, since there coordination is defined only between gestural onsets.

Regardless of the type of the BT coordination, it is further expected that the coordination of BT gestures will be influenced by the position of lexical stress, such that the BT gesture is initiated earlier in words with non-final stress than in words with final stress, but still within the phrase-final syllable. This prediction emerges again from the fact that the onset of the boundary tones coincides with the offset of the phrase accent. The offset of phrase accent in Greek has been found to occur earlier within the phrase-final syllable in words with non-final stress than in words with final stress (cf. Arvaniti & Ladd, 2006a, 2006b, 2009), and thus the same pattern should be observed on the onset of boundary tones. Moreover, this effect of stress should hold regardless of the accentual status of the phrase-final word, in that the findings on phrase accents hold for both accented final words in yes-no questions (Arvaniti & Ladd, 2006b) and de-accented final words in wh-questions (Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009). However, the effect might be intensified in the case of the accented phrase-final words due to tonal crowding (e.g., Arvaniti et al., 2006a, 2006b). This may be expressed as follows: the closer the pitch accent is to the boundary tone, the more delayed the onset of the BT gesture should be.

The predictions tested here are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Predictions tested

| BT Coordination | Effect of lexical stress | Effect of pitch accent |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

BT gesture is coordinated with phrase-final V gesture in one of the following ways:

|

BT onset should occur earlier in words with non-final stress than in words with final stress. | BT onset should occur later the closer the pitch accent is to the boundary tone. |

2.0 Methods

The current study investigates the coordination of boundary tones through an Electromagnetic Articulography (EMA) study of Greek. This section describes the details of the experiment and analyses.

2.1 Participants

Eight native speakers (5 female, 3 male) of standard Greek participated in this study, aged between 19 and 31. They were naive to the purpose of the study and had no self-reported speech, hearing or vision problems. Participants gave informed consent and received financial compensation for their participation. The Yale University Human Investigation Committee approved the protocols reported here.

2.2 Experimental design and stimuli

Stimulus sentences were constructed to investigate the coordination of boundary tones as a function of lexical stress and pitch accent. The effect of lexical stress (Stress) was examined in trisyllabic phrase-final test words stressed on one of the following syllables:

The 1st syllable, i.e., the antepenult, resulting in stress-initial words (S1).

The 2nd syllable, i.e., the penult, resulting in stress-medial words (S2).

The 3rd syllable, i.e., the ultima, resulting in stress-final words (S3).

To separate the role of lexical stress (Stress) from that of pitch accent (Accent), the test words were placed in phrase final positions that were either de-accented (D), or accented (A).

Based on the fact that lexical stress in Greek is contrastive, the following neologisms forming a minimal stress triplet were used: MAmima, maMIma and mamiMA (capital letters stand for stress). Each of them means a type of a narcotic plant. This meaning was chosen in order to suit the context of all the types of stimuli sentences used. These neologisms were constructed so as to minimize constriction gesture variability, ensure F0 continuity, and optimize articulator traceability.

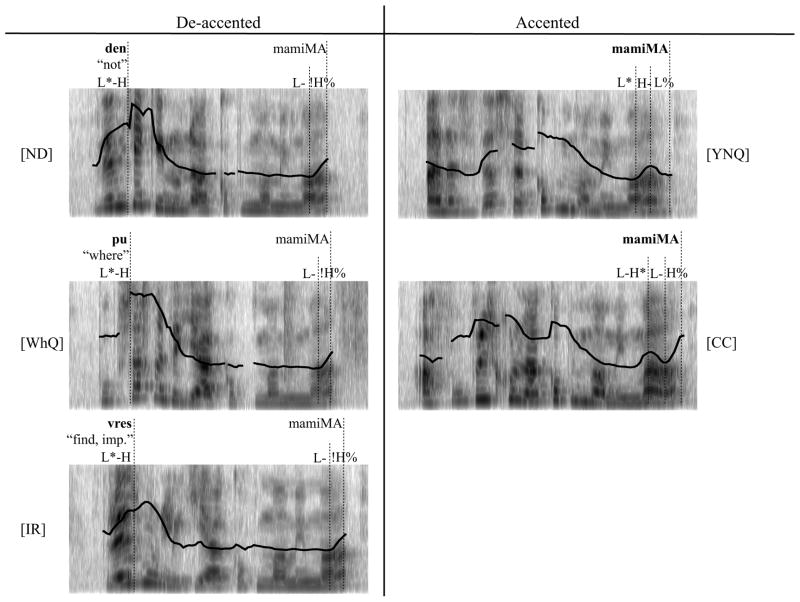

The coordination of boundary tones was investigated by the means of five types of syntactic constructions, selected because their contours involve alternating tones, rendering their onsets and targets detectable at the F0 inflection points. Three of these constructions elicited utterances with de-accented phrase-final words: Wh-questions (WhQ), imperative requests (IR) and negative declaratives showing reservation (ND). These involve the same intonational contour: L*+H L-!H%. Specifically, the negative, wh- or imperative word, which typically is the first word in the respective type of sentence, carries the nuclear pitch accent (L*+H) and the remainder of the phrase bears no accent. The L-phrase accent stretches thus from the nuclear accent to the end of the phrase, which bears the !H% boundary tone % (cf. Greek ToBI: Arvaniti & Baltazani, 2005). Thus, negative declaratives, wh-questions and imperative requests are identical in terms of intonational contour, and they are different from each other mainly on morpho-syntactic grounds. The other two constructions elicited utterances with accented phrase-final words: yes-no questions (YNQ) and causative clauses (CC). The respective contours were L* H-L% and L-H* L-H% (cf. Arvaniti & Baltazani, 2005). Figure 1 presents representative examples of the intonational contours elicited from each of the experimental constructions, using utterances ending in stress-final words (mamiMA) produced by the same speaker. The figure illustrates how negative declaratives, wh-questions and imperative requests involve identical intonational contours.

Figure 1.

F0 tracks superimposed on the spectrograms of a representative negative declarative (ND), wh-question (WhQ), imperative request (IR), yes-no question (YNQ) and causative clause (CC) respectively produced by Speaker F04. The words bearing the nuclear accent and the phrase-final words are annotated. The former are given in bold letters. In accented constructions (YNQ and CC), the two types of words coincide (the phrase-final words are the ones bearing the nuclear accent as well). Dotted vertical lines represent the right boundary of these words and of the phrasal tones of the utterance.

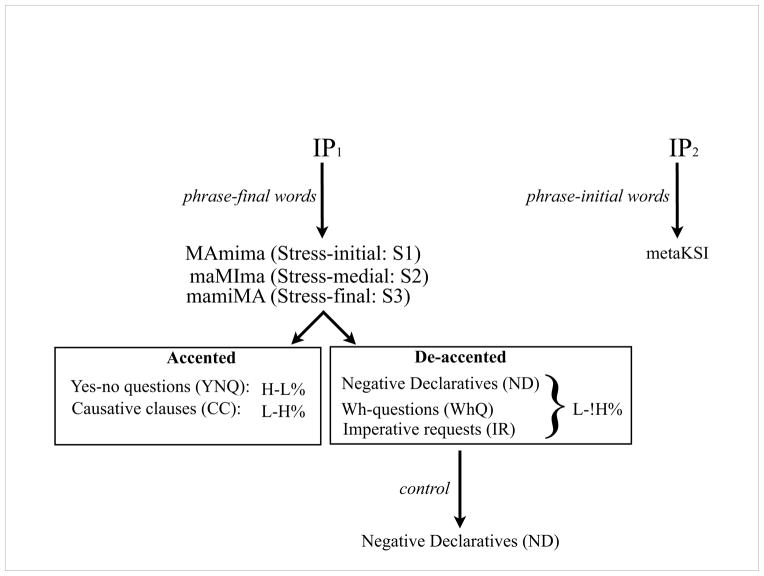

Hence, three types of boundary tones were investigated: L%, H% and !H%. To examine whether boundary tones affect the inter-syllabic coordination between C and V gestures, negative declaratives (ND) with the test words in a phrase-medial de-accented position (where the test words do not bear either a pitch accent or a boundary tone) were used as controls. Each of the target sentences was followed by another sentence, beginning with the word metaKSI that means “among” (capital letters represent the lexically stressed syllable). In all target sentences, there were seven syllables before and thirteen syllables after the pre-boundary test word, with two unstressed syllables immediately preceding and following that word. Figure 2 summarizes the experimental design. This figure shows that each experimental trial consists of two phrases, IP1 and IP2, with IP1 being either accented (i.e., either yes-no question or causative clause) or de-accented (namely one of the following: negative declarative, wh-question or imperative request). The final word of IP1 is MAmima, maMIma or mamiMA, while the initial word of IP2 is metaKSI. The figure also reminds the reader of the combination of phrase accent and boundary tone that corresponds to each construction, and of the additional set of negative declaratives (in which the test words MAmima, maMIma and mamiMA are phrase-medial) that are used as controls for the de-accented constructions in order to examine the effect of boundary tone on C-V coordination.

Figure 2.

Experimental Design

In total, three test words were used in six types of syntactic constructions, yielding eighteen target sentences. Each target sentence, except causal clauses and yes-no questions, was preceded by a contextualizing sentence, which served to elicit the right pitch contour in the test material. Such a facilitating elicitation means was not considered necessary for the cases of causal clauses and yes-no questions. During the recording process, the target sentence was read aloud, whereas the context sentence was read silently. Nine blocks of the test sentences were constructed, each containing one repetition of the eighteen test sentences in a randomized order. This sums to 162 target sentences per participant (6 syntactic constructions x 3 test words x 9 repetitions). The materials of each block were interspersed with the 12 additional sentences used in combination with the 18 target sentences described here for the part of the experiment focused on the scope of boundary lengthening. Table 2 contains the target sentences for the stress-initial test words (S1). For each syntactic construction, a rough translation into English of the context sentence (if present) is given first, and a transliterated version of the target sentence along with a rough translation into English follows. The words bearing the nuclear pitch accent, which in these cases stands for broad focus, are marked with bold letters. Lexically stressed syllables are marked with capital letters. Punctuation marks stand for phrase boundaries. For stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) test words, the same sentence frames were used.

Table 2.

The stimuli for stress-initial words (MAmima)

| Negative declarative showing reservation (ND): What they are doing is horrible! dhen dhjakiNUN Akopi MAmima. metaKSI mathiTON karameLItses puLUN. It is not that they merchandize raw MAmima. It is just ‘candies’ they sell to students. |

| Wh-question (WhQ): We are looking for raw MAmima. pu PSAhnete JAkopi MAmima? metaKSI mathiTON evREos dhjakiNIte. Where are you looking for raw MAmima? Usually one can find some among students. |

| Imperative request (IR): You seem as if you want to ask me for a favor. VRESmu LIji Akopi MAmima. metaKSI mathiTON evREos dhjakiNIte. Find some raw MAmima for me. Usually one can find some among students. |

| Yes-no question (YNQ): anaziTAS Akopi MAmima? metaKSI mathiTON evREos dhjakiNIte. Are you looking for raw MAmima? Usually one can find some among students. |

| Causative clause (CC): aFU VRIskun Akopi MAmima, metaKSI mathiTON liKIu tin dhjakiNUN. Since it happens to have in their possession raw MAmima, they merchandize it to students. |

| Control negative declarative showing reservation (Control ND): What they are doing is unacceptable! dhen dhjakiNUN Akopi MAmima metaKSI mathiTON kjaNIlikon efivon. It is not that they merchandize raw MAmima to students and underage teenagers. |

2.3 Apparatus and recording procedure

The experimental procedure consisted of a training session and an experimental session. The training session took place 1–3 days before the experimental one, was 20–30 minutes long, and its role was to familiarize the participants with the speech material and its presentation. In the experimental session, simultaneous kinematic and acoustic data were acquired using the AG500 three-dimensional electromagnetic articulometer (Carstens Medizinelektronik) at the physiology lab at Haskins Laboratories. Eleven receiver coils were attached to the tongue dorsum, tongue body, tongue tip, upper lip, lower lip, left and front sides of the jaw, upper incisor, left ear, right ear and nose. The latter four functioned as references used to correct for head movement. A standard calibration procedure preceded each experimental session (cf. Hoole, Zierdt & Geng 2003). Acoustic data were acquired using a Sennheiser shotgun microphone at a sampling rate of 16 kHz. The microphone was positioned about 30 cm away from the participant’s mouth.

The instructions and the speech material for the experimental session were presented visually on a computer screen, integrated with control of data acquisition using custom software (Marta, developed by Mark Tiede, Haskins Laboratories). The instructions reminded the participants to pay attention to the position of lexical stress on the test words, the punctuation signs and the words in bold, which indicated words bearing the main information of the sentence. Context sentences appeared in green letters some seconds earlier than their respective target sentence, which appeared in blue letters. The participants were given 8–10 seconds to read each target sentence at their normal speech rate. Participants were asked to repeat sentences produced with speech errors or interrupted by unintended pauses or disfluencies. Real-time display of upper incisor position to the participants relative to a desired target was used to reduce excessive head movement.

2.4 Analysis

The data acquired from each participant were subject to the TAPADM (Three-dimensional Articulographic Position and Align Determination with MATLAB™, developed by Andreas Zierdt) pre-processing procedure in order to smooth, correct and translate the data to the occlusal plane (for more details see Hoole et al., 2003). This procedure also functions as a checking method for the reliability of the data. Based on the results of this analysis, the data acquired from three participants were considered ineligible for further analysis. The five participants used for the analysis are referred to as Speakers F01, F02, F03, F04 and M05 (four female and one male). Some of the tokens of these Speakers were eliminated from the analysis due to abnormalities in their displacement or velocity signal (less than 3%). Data were manually pitch-corrected using a Praat script written by Yi Xu (UCL) and checked for their intonation using GrToBI (Arvaniti & Baltazani, 2005). Tokens not conforming to the expected intonational contours or presenting difficulties in detecting the relevant F0 landmarks (e.g., during creaky vowels) were discarded. Specifically, the causative clauses with stress-final words (9 tokens) and the negative declaratives (27 tokens) of Speaker F01, and the causative clauses (27 tokens) of Speaker F03 were eliminated from the analysis because they were produced with alternative contours. In addition to these 63 tokens, 53 tokens were discarded. With respect to the rest of the data, 5–13 tokens per Stress condition in each syntactic construction per Speaker were included in the analysis, giving 717 tokens in total. Recall that the experimental design required nine repetitions for each sentence. However, in some cases additional repetitions were acquired for a variety of reasons (e.g., resumption of the recording after interruption due to software error).

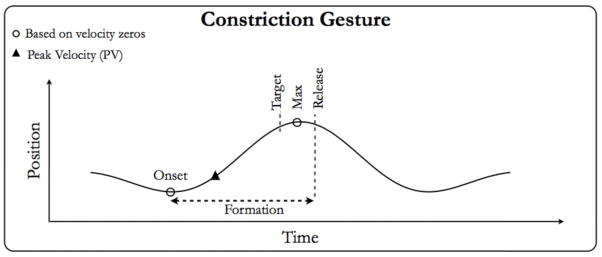

The resulting dataset was semi-automatically labeled using custom software (Mview, Mark Tiede, Haskins Laboratories). Kinematic labeling was conducted on the lip aperture trajectory (the Euclidean distance between the upper and lower lip trajectories) for the labial consonants and on the tongue dorsum vertical displacement trajectory for the vowels of the pre-boundary test words; pitch labeling was conducted on the F0 tract variable. Kinematically, the following landmarks of the phrase-final C and V constriction gestures were detected: the onset, peak-velocity time (pv), target, time of constriction maximum (max), and release of their formation (shown in Figure 3). These temporal landmarks were identified on the basis of velocity criteria, i.e., velocity thresholds (10% for the onsets of C gestures and 20% for the rest). The velocity of lip aperture was used for the labial consonants, and the tangential velocity of tongue dorsum for the vowels.

Figure 3.

Kinematic landmarks for constriction gestures

For F0 labeling, the onsets of boundary tone gestures (BT onsets) were detected at the F0 inflection points that precede the F0 targets corresponding to boundary tones. In other words, the onset of H% and !H% boundary tones is defined as the preceding F0 minimum, and the onset of L% boundary tones as the preceding F0 maximum. An illustration of these inflection points is shown in Figure 1 above, where BT onsets coincide with the vertical lines representing the right boundary of phrase accents (L- for ND, WhQ, IR and CC, and H- for YNQ). These inflection points were detected differently for falling (L%) and rising (H% and !H%) pitch movements. The onset of the former was identified at the F0 maximum that immediately preceded their low targets. However, a similar criterion could not be used successfully in the case of rising boundary tones, since their preceding F0 minimum did not systematically correspond to the F0 elbow (see also D’ Imperio, 2000). The latter was identified on the basis of velocity criteria, and specifically as the last elbow before the increase in the frequency of vibration of the vocal folds for the production of the high tone. Figure 3 illustrates F0 labeling.

The analyses applied using these kinematic and F0 temporal landmarks for assessing the coordination of boundary tones are described in the Results section. All the statistical analyses described there were carried out in the R statistical environment (R Development Core Team, 2011).

3.0 Results

3.1 Coordination of boundary tone gestures

To examine whether BT gestures are coordinated with the phrase-final vowel and what form this coordination takes (i.e., in-phase, anti-phase or coincidental with peak velocity), temporal intervals were calculated between the onset of BT gesture (BT onset) and the following articulatory landmarks of the phrase-final syllable:

Onset of C gesture (C-onset).

Onset of V gesture (V-onset).

Time of peak velocity of C gesture (C-pv).

Time of peak velocity of V gesture (V-pv).

Target of V gesture (V-target).

Constriction maximum of V gesture (V-max).

Release of V gesture (V-release).

The intervals in list (A) were submitted to two sets of analyses, described and reported in Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2 below, examining with which articulatory landmark BT onset is more closely aligned and more stably timed respectively. Close alignment would be indicated by the interval with the shortest duration, and stability by the interval with the smallest variance. If the BT onset occurs after C and V onsets, the hypothesis that BT gestures occur within the phrase-final syllable is confirmed. Furthermore, intervals (1) and (2) assess whether the onset of BT gesture is aligned with and/or stably timed with the onset of either the C (interval 1) or the V gesture (interval 2). Close alignment and stability between BT and V gestures would indicate in-phase coordination between the BT and the V gestures. If, on the other hand, the BT gesture is initiated while the V gesture reaches its target (i.e., if one of the intervals (5), (6) or (7) is the shortest and/or the most stable), the hypothesis of anti-phase coordination between the BT and the V gestures is supported. Finally, intervals (3) and (4) assess whether the onset of the BT gesture coincides with and/or is stably timed to the peak velocity time of either the C or the V gestures respectively. For these analyses, only the three constructions involving de-accented phrase-final words were analyzed, namely wh-questions (WhQ), imperative requests (IR) and negative declaratives (ND), in order to avoid pitch accent-driven confounding effects. On the basis of the same F0 contour (i.e., L+H* L-!H%) that these constructions involve, shown in Section 2.2, the data elicited from them were polled together. This decision was further justified by initial stages of data processing, in which the same analyses reported here for the pooled data were performed on each construction separately and showed that individual constructions behaved similarly to each other and to the pooled data.

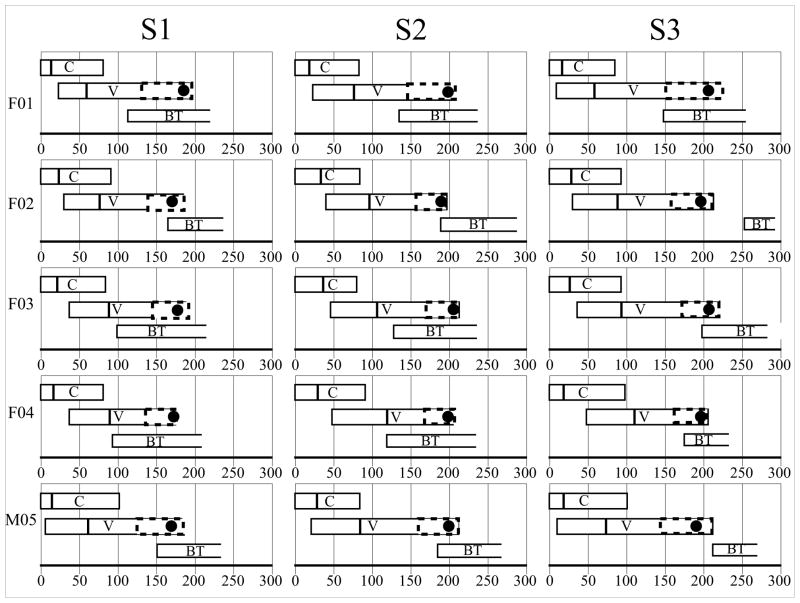

3.1.1 Close alignment of boundary tone gestures

Figure 4 contains the gestural scores (cf. Browman & Goldstein, 1990a, 2000) for the final syllable of the de-accented phrase-final stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words for each Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04 and M05). Within each gestural score there are three solid boxes representing the C, V and BT gestures of the respective phrase-final syllable. The lengths of the C and V boxes reflect the mean duration of the C and V formation gestures for the given Stress and Speaker. The BT boxes do not have a right border because information about the duration of BT gestures is lacking. However, BT boxes extend after the respective V boxes in order to capture the fact that BT gestures roughly last until the termination of phonation, which follows the V release. The position of C, V and BT boxes within the gestural score shows the relative timing between the C, V and BT gestures, since the left border of these boxes stand for C, V and BT onsets. The other articulatory C and V landmarks are also shown in the gestural scores. Vertical solid lines crossing C and V boxes stand for the peak velocity times for C and V formation movements respectively. The left border of the dashed boxes within the V boxes corresponds to the target of respective V gesture, and its right border to the release of the V gesture. Solid circles within the dashed boxes stand for maximal points. The position of these landmarks was calculated as the mean value of the intervals listed in (A) for each Stress per Speaker. As Figure 4 reveals BT gestures are initiated much later than C and V gestures. However, as explained above, in order to specify the articulatory landmark with which BT onset is more closely, the articulatory landmark with the shortest temporal interval from BT onset should be detected.

Figure 4.

Gestural scores (in ms) of the final syllable of de-accented stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) phrase-final words per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05). Closed solid boxes stand for C and V gestures and open-ended solid boxes for BT gestures. Vertical solid lines crossing the C and V boxes mark peak velocity times. The left and right borders of the dashed boxes included in the V boxes represent V targets and V releases respectively. Circles stand for constriction maxima of V gestures.

As a clarification note, the term alignment as used here is not to be confused with phasing. The question asked here is at which point of the articulatory development of the phrase-final syllable the BT onset occurs. The answer to this question will then serve as an indication of what the phasing/coordination is between the BT gesture and the constriction gestures of the phrase-final syllable. For example, if BT onset is closely aligned (i.e., if it coincides) with the onset of the phrase-final V gesture, in-phase coordination between the BT and the V gestures is suggested. On the other hand, close alignment between BT onset and the target of the phrase-final V gesture would suggest that the two gestures are in anti-phase coordination.

To evaluate which of the temporal intervals in list (A) is the shortest, the dataset of each Speaker was submitted to Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with interval duration (in ms) as the dependent variable and Interval Origin (levels: C-onset, V-onset, C-pv, V-pv, V-target, V-max, V-release) and Stress (levels: S1, S2 and S3) as factors. The term Interval Origin stands for the articulatory landmark from which the interval to BT onset was calculated. Both main and interaction effects were investigated, and post-hoc pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni adjustment were performed to assess significant effects. The alpha level for significance was set to 0.05. Only significant results are reported.

Main effects of Interval Type and Stress were detected for all Speakers [Interval Type: F01: F(6, 313) = 462.97, p < 0.0001; F02: F(6, 537) = 723.38, p < 0.0001; F03: F(6, 502) = 1107.98, p < 0.0001; F04: F(6, 497) = 783.42, p < 0.0001; M05: F(6, 626) = 1463.33, p < 0.0001. Stress: F01: F(2, 313) = 26.09, p < 0.0001; F02: F(2, 537) = 437.72, p < 0.0001; F03: F(2, 502) = 755.5, p < 0.0001; F04: F(2, 497) = 381.24, p < 0.0001; M05: F(2, 626) = 313.09, p < 0.0001]. An interaction effect was found for Speakers F03, F04 and M05 [F03: F(12, 502) = 3.31, p = 0.0002; F04: F(12, 497) = 2.01, p = 0.0213; M05: F(12, 626) = 3.00, p < 0.0001].

The post-hoc pairwise comparisons reveal that the BT gesture is initiated as the V gesture reaches its target for Speaker F01, with the interval between BT onset and V-target being shorter than all the other intervals (p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons). Specifically, for Speaker F01, BT onset occurs on average 9 ms earlier than the onset of V the target across Stress conditions. For Speaker F02, BT onset occurs between the constriction maximum and the offset of the V gesture, with the respective intervals being shorter than the other ones (p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons except between V-max and V-target for which p = 0.0005), but insignificantly different from each other. The interval between BT onset and V-max is on average 22 ms long and that one between BT onset and V-release 4 ms long across Stress conditions. For Speakers F03, F04 and M05 who present an interaction effect, the effect of Interval Type is examined in each Stress condition separately. For Speakers F03 and F04, the interval with the shortest mean value is the one between BT onset and V peak velocity in stress-initial (S1) and stress-medial (S2) words [S1: F03: 11 ms; F04: 4 ms; S2: F03: 22 ms; F04: 0 ms (p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons)]. In stress-final words (S3), BT onset occurs 4 ms before the V gesture’s constriction maximum for F03 [p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons except for the comparison with V-target (p = 0.0041) and V-release (non-significant)], and 13 ms after V target for F04 (p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons). For Speaker M05, BT onset occurs 12 and 8 ms on average before the constriction maximum of the V gesture in stress-initial words (S1) [p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons except for comparison with V-release (p = 0.0011)] and stress-medial words (S2) [p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons except for comparison with V-release (p = 0.0539)] respectively. However, in stress-final words (S3), BT onset occurs on average 1 ms after the release of the V gesture for M05 (p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons).

To conclude, as predicted on the basis of research on phrase accents in Greek (Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009; cf. also Arvaniti et al., 2006a, 2006b), BT gestures occur during the phrase-final syllable. The BT gesture is roughly initiated during the target of the V gesture of the phrase-final syllable for all five Speakers in stress-final words (S3) and for three Speakers (F01, F02 and M05) in stress-initial (S1) and stress-medial (S2) words. In these Stress conditions (S1 and S2), for the other two Speakers (F03 and F04), BT onset occurs as the V gesture achieves its peak velocity (see Figure 4 above for these differences per Stress condition and Section 3.2 for a detailed report on the effect of lexical stress). Our data thus indicate that BT gestures are sequential to phrase-final V gestures, supporting the hypothesis according to which BT and V gestures are coupled anti-phase to each other (cf. Hsieh, 2011; see also Prieto, 2009; Prieto & Torreira, 2007), presenting similar coordination patterns to coda consonants (e.g., Browman & Goldstein, 2000; Nam, 2007). This conclusion is reinforced by the assumption that stress-final words present the default coordination of BT gestures in Greek, since such a default case could account for all the types of Greek words – including monosyllabic ones – which are obligatorily lexically stressed.

3.1.2 Stability of boundary tone gesture coordination

To evaluate the stability of the coordination of BT gestures, the standard deviations of the seven temporal intervals were submitted to a set of repeated measures ANOVAs with Stress (levels: S1, S2 and S3) and Interval (levels: C-onset, V-onset, C-pv, V-pv, V-target, V-max, V-release) as fixed factors and Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04 and M05) as the repeated factor. Repeated measures ANOVAs across the five Speakers were applied in this case, as opposed to separate ANOVAs per Speaker, because of the limited number of values used per Speaker for this analysis (a single value per Stress condition) (cf. Shaw, Gafos, Hoole and Zeroual, 2011). Both main and interaction effects were assessed, and in case of a significant effect, post-hoc pair-wise comparisons using the Bonferroni adjustment were performed. For both the ANOVAs and the pairwise comparisons, the alpha level was set to 0.05.

Table 3 contains the standard deviations of the temporal intervals between the onset of the BT gesture and each of the seven articulatory landmarks across Speakers per Stress condition. The repeated measures ANOVAs did not detect any significant effect, indicating that the seven temporal intervals are equally variable.

Table 3.

Standard deviation of the temporal intervals (in ms) from BT onset to articulatory landmarks of the C and V gestures of the phrase-final syllable in de-accented stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words.

| C-onset | V-Onset | C-pv | V-pv | V-target | V-max | V-target | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 37.9 | 44.5 | 37.72 | 44.68 | 41.22 | 40.88 | 38.82 |

| S2 | 37.22 | 45.3 | 37.92 | 47.69 | 41.37 | 43.21 | 42.2 |

| S3 | 40.7 | 43.34 | 37.6 | 42.39 | 42.95 | 43.57 | 41.78 |

In conclusion, while the analysis of BT close alignment presented in Section 3.1.1 supports an anti-phase coordination between BT gestures and phrase-final V gestures, the analysis given here does not detect any articulatory landmarks with which the BT gesture is more stably coordinated.

3.1.3 Effects of BT gestures on C-V coordination

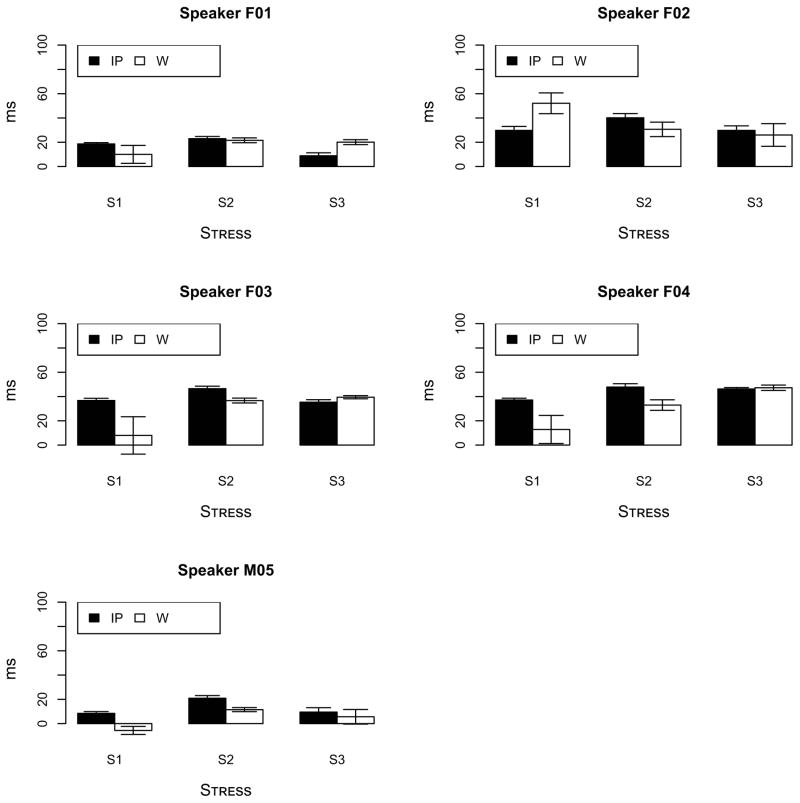

To address the question of whether boundary tone gestures affect the coordination of syllable’s onset C and nucleus V gestures to each other, we examined whether C-to-V coordination is different in syllables bearing a boundary tone than in syllables without a boundary tone. For this purpose, the temporal interval between C onset and V onset (C-V) in final syllables of de-accented phrase-final (IP) and phrase-medial (W) words was calculated, since a boundary tone is present in the former case (IP), but absent in the latter (W). ANOVAs with Boundary (levels: IP, W) and Stress (levels: S1, S2, S3) as factors were applied on the duration of this interval for each Speaker separately. In case of significant main or interaction effects, post-hoc pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni adjustment were conducted. The alpha level for the ANOVAs and the pairwise comparisons was 0.05.

The means and standard deviations of these C-V intervals are shown in Figure 5. The ANOVAs showed no main nor interaction effects of these factors, suggesting that the presence of BT gesture does not cause any adjustments, such as the c-center effect, to the coordination between C and V gestures.

Figure 5.

Mean and standard deviation of the temporal interval (in ms) from C onset to V onset phrase-finally (IP) vs. phrase-medially (W) in de-accented stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05).

On the basis of the analyses presented in Section 3.1, the following general conclusions are drawn. The hypothesis of BT gestures being in-phase coordinated with C or V gestures (cf. Gao, 2008; Mücke et al., 2012) and that one of BT onset being coincident with C or V peak velocity time (cf. D’ Imperio et al., 2007) are rejected. Instead, the rough co-occurrence of BT onset with V target validates to the hypothesis that BT gestures are anti-phase coordinated with phrase-final V gestures (cf. Hsieh, 2011; Prieto, 2009; Prieto & Torreira, 2007). However, the temporal intervals defined as extending from BT onset to each of the articulatory landmarks of V target do not present less variability, i.e., more stability, in comparison to the temporal intervals measured between BT onset and the other articulatory landmarks. Finally, BT gestures do not exert any timing effect, such as the c-center effect, on the C-V coordination of the phrase-final syllable (cf. Gao, 2008; Mücke et al., 2012).

3.2 Effects of prominence on the coordination of boundary tone gestures

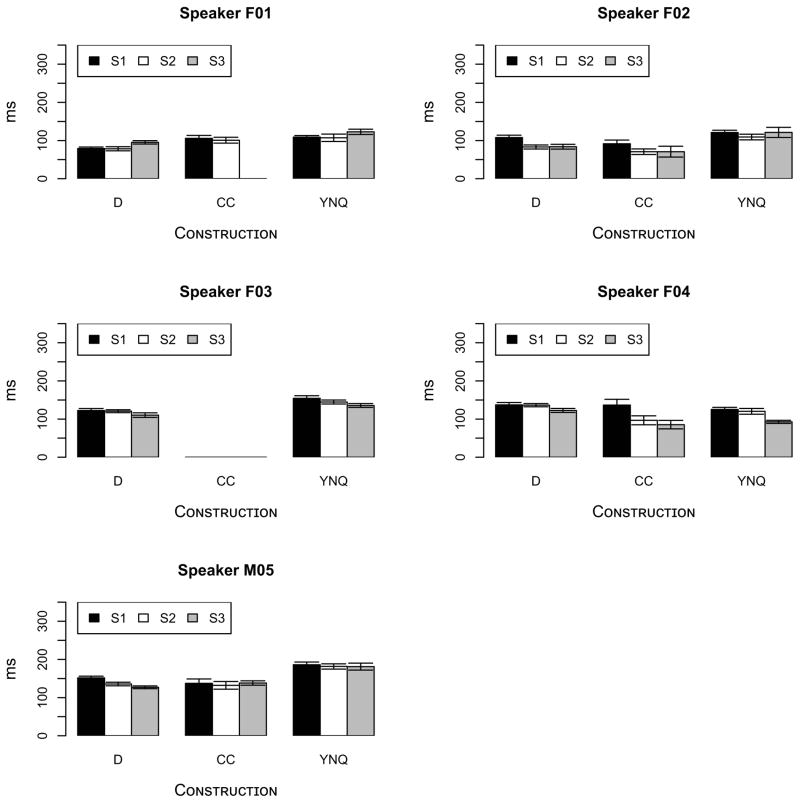

The results presented in Section 3.1 show that BT onsets co-occur with V targets supporting the assumption that the BT gesture is coordinated anti-phase to the V gesture of the phrase-final syllable. On the basis of this conclusion and given that coordination is observed between onsets, the effects of lexical stress and pitch accent on BT gesture coordination were examined using the temporal interval between the onsets of BT and V gestures (BT-V). For this analysis, both accented and de-accented constructions were used. The data from the three de-accented conditions (ND, WhQ and IR) were pooled together, following the same reasoning outlined in Section 3.1. The accented constructions were not pooled together because of their different intonational contours and strengths of boundaries. Yes-no questions (YNQ: L* H-L%) have stronger boundaries than causative clauses (CC: L-H* L-H%). The BT-V temporal intervals of all tokens per Speaker were submitted to a set of ANOVAs with Stress (levels: S1, S2, S3) and Construction (levels: D, YNQ, CC) as factors. Significant main and interaction effects were detected (α = 0.05), and further pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.05) were conducted.

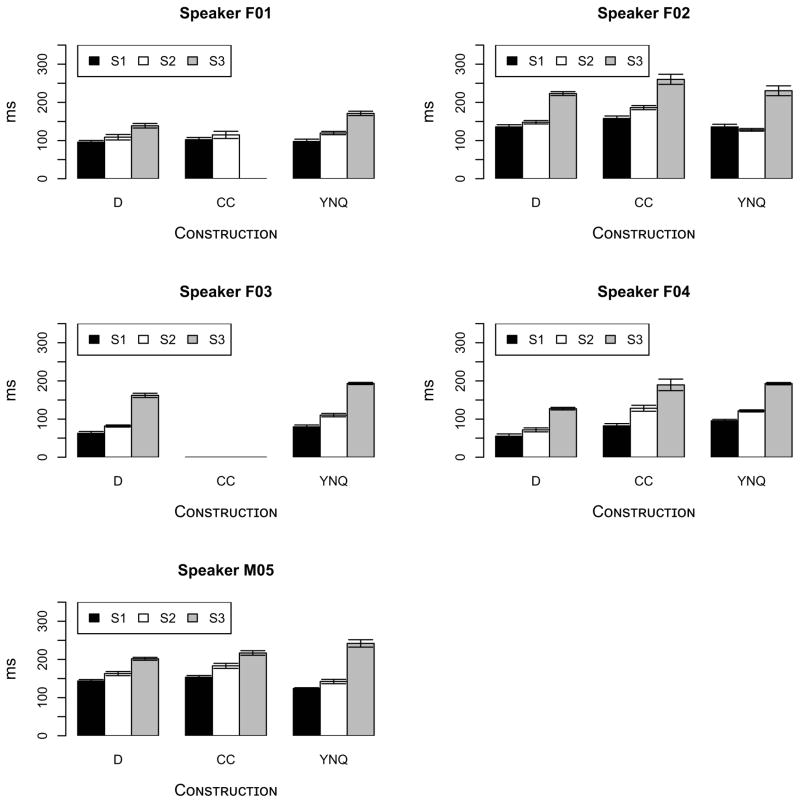

Figure 6 illustrates the mean durations of the BT-V intervals (along with their standard deviations) per Stress and Construction for each Speaker separately.

Figure 6.

Mean and standard deviation of the temporal interval (in ms) from V onset to BT onset in stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05) for each Construction (D, CC, YNQ).

The ANOVAs detected a main effect of both Stress and Construction for all Speakers [Stress: F01: F(2, 83) = 46.63, p < 0.0001; F02: F(2, 120) = 150.1, p < 0.0001; F03: F(2, 96) = 225.7, p < 0.0001; F04: F(2, 118) = 144.02, p < 0.0001; M05: F(2, 142) = 122.38, p < 0.0001. Construction: F01: F(2, 83) = 4.44, p = 0.015; F02: F(2, 120) = 19.00, p < 0.0001; F03: F(1, 96) = 31.07, p < 0.0001; F04: F(2, 118) = 74.81, p < 0.0001; M05: F(2, 142) = 5.8, p = 0.0038]. An interaction effect between the two factors was observed for Speakers F04 and M05 [F04: F(4, 118) = 2.47, p = 0.048; M05: F(4, 142) = 8.64, p < 0.0001].

Based on the results of ANOVAs, post-hoc pairwise comparisons examined the effect of each factor across all levels of the other factor for Speakers who did not present an interaction effect (F01, F02 and F03), and within each condition of the other factors for Speakers who presented an interaction effect (F04 and M05). As far as the effect of lexical stress is concerned, the post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that the BT-V interval is greater in stress-final (S3) than in either stress-medial (S2) or stress-initial (S1) words regardless of their accentual status (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons except between S2 and S3 in CC for Speakers F04 and M05, for which the p values are 0.0009 and 0.0011 respectively). Moreover, the majority of pairwise comparisons between stress-initial (S1) and stress-medial (S2) words were significant, with the BT-V interval being larger in S2 than in S1 (F01: p = 0.016; F02: p = 0.076; F03: p = 0.0005, F04: p = 0.062 in D, p < 0.0001 in YNQ, and p = 0.0122 in CC; M05: p = 0.0085 in D, not significant in YNQ, and p = 0.0036 in CC).

Turning to the factor of Construction, the effects are not systematic. Speaker F01 had marginally longer BT-V intervals in yes-no questions than in either de-accented constructions (p = 0.057) or causative clauses (p = 0.052); Speaker F02 presented longer BT-V intervals in causative clauses than in either de-accented constructions (p = 0.054) or yes-no questions (p = 0.026), with the former effect being marginal; no effect was detected for Speaker F03; Speaker F04 had longer BT-V intervals in de-accented constructions than in each of the accented ones (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons except between D and CC in S1 for which p = 0.0003 and between D and YNQ in S1 for which p = 0.0142); finally, Speaker M05 showed longer BT-V intervals in de-accented constructions than in yes-no questions in stress-initial words (p = 0.018), but the opposite pattern in stress-final words (p = 0.0001).

Forming a general conclusion, lexical stress has an effect on the timing of BT gestures, such that BT gestures are initiated later within the phrase-final V gesture as the stress occurs later within the phrase-final word (cf. Arvaniti & Ladd, 2009; see also Arvaniti, 2006a, 2006b). This effect holds independently of the accentual status of the phrase-final word. Pitch accent, on the other hand, does not influence BT coordination regularly, since the accented constructions (YNQ and/or CC) are not significantly different from the de-accented ones (D). This result goes against the prediction based on tonal crowding, according to which the closer the pitch accent is to the boundary tone, the later the boundary tone should to be initiated (e.g., Arvaniti et al., 2006a, 2006b).

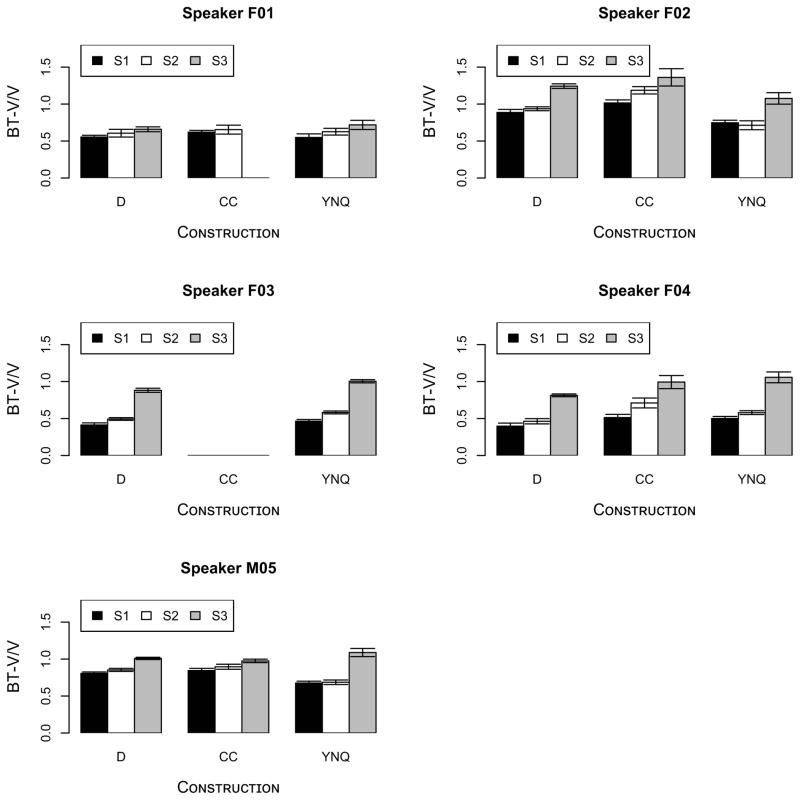

Given that in Greek stressed syllables are longer than unstressed ones (for an overview see Arvaniti, 2007 and references therein), an additional set of analyses was performed in order to confirm that the detected effect of stress on BT coordination is not a confound effect of stress-related lengthening. In this set of analyses the time of BT onset is controlled relative to the target of the V gesture. In particular, the BT-V intervals were normalized over the durations of the phrase-final V gestures, with the latter being calculated as the interval between the onset of the V gesture and its release. The BT-V interval of each token was calculated as a proportion of the duration of the respective final V gesture. Figure 7 presents the means and standard deviations of this measure per Stress, Construction and Speaker.

Figure 7.

Mean and standard deviation of the temporal interval from V onset to BT onset as a proportion of the duration of the corresponding phrase-final V gesture in stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05) for each Construction (D, CC, YNQ).

The ANOVAs revealed a main effect of Stress for all Speakers [F01: F(2.83) = 4.66, p = 0.012; F02: F(2, 120) = 45.85, p < 0.0001; F03: F(2, 96) = 168.83, p < 0.0001; F04: F(2, 118) = 89.27, p < 0.0001; M05: F(2, 142) = 69.08, p < 0.0001]. A main effect of Construction was detected for four Speakers [F02: F(2, 120) = 24.96, p < 0.0001; F03: F(1, 96) = 45.85, p = 0.001; F04: F(2, 118) = 16.55, p < 0.0001; M05: F(2, 142) = 5.96, p = 0.0033]. Finally, an interaction effect was found for Speaker M05 [F(4, 142) = 7.87, p < 0.0001].

According to the post-hoc pairwise comparisons, all Speakers presented longer normalized BT-V intervals in stress-final (S3) than stress-initial (S1) words, regardless of accentual status (F01: p = 0.0088; F02, F03 and F04: p < 0.0001; M05: p < 0.0001 in D and YNQ, p = 0.018 in CC). Furthermore, the normalized BT-V interval was longer in stress-final (S3) than stress-medial (S2) words for four Speakers (F02, F03 and F04: p < 0.0001; M05: p < 0.0001 in D and YNQ, but non significant in CC). Finally, only Speaker F03 had longer normalized BT-V intervals in stress-medial (S2) than stress-initial (S1) words (p = 0.0058).

As for the factor of Construction, the pairwise comparisons detected significant differences for three Speakers. Speaker F02 had shorter normalized BT-V intervals in yes-no questions, longer in de-accented constructions and even longer in causative clauses (CC > YNQ: p < 0.0001; CC > D: p = 0.0138; D > YNQ: p = 0.0012). Speaker F04 presented shorter normalized BT-V intervals in de-accented constructions than in either yes-no questions (p = 0.023) or causative clauses (p = 0.016). Finally, for Speaker M05, the normalized BT-V intervals are shorter in de-accented constructions than in yes-no questions in stress-initial (p = 0.002) and stress-medial words (p = 0.0012), and longer in yes-no questions than in causative clauses in stress-initial words (p = 0.0009), with the opposite pattern in stress-final words (p = 0.055).

In conclusion, some of the patterns observed in the raw data persist in the normalized ones. Specifically, BT gestures are initiated later in stress-final words (S3) than in either stress-initial (S1) or stress-medial (S2) ones. However, the differences between the two latter types of words (i.e., S1 and S2) disappear. These findings imply that delays of BT onset observed in words with final stress as opposed to words with non-final stress are not side-effects of the stress-related lengthening observed on stressed syllables, but more direct effects of lexical stress on the coordination of the BT gesture. Regarding pitch accents, no systematic effects are observed as in the case of the raw data, indicating the absence of a systematic tonal crowding effect.

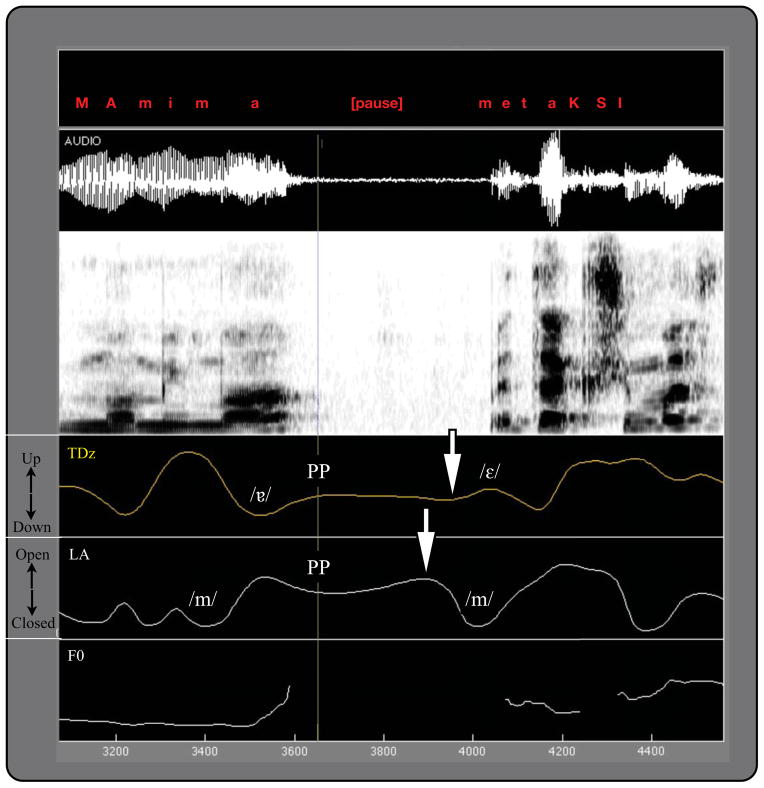

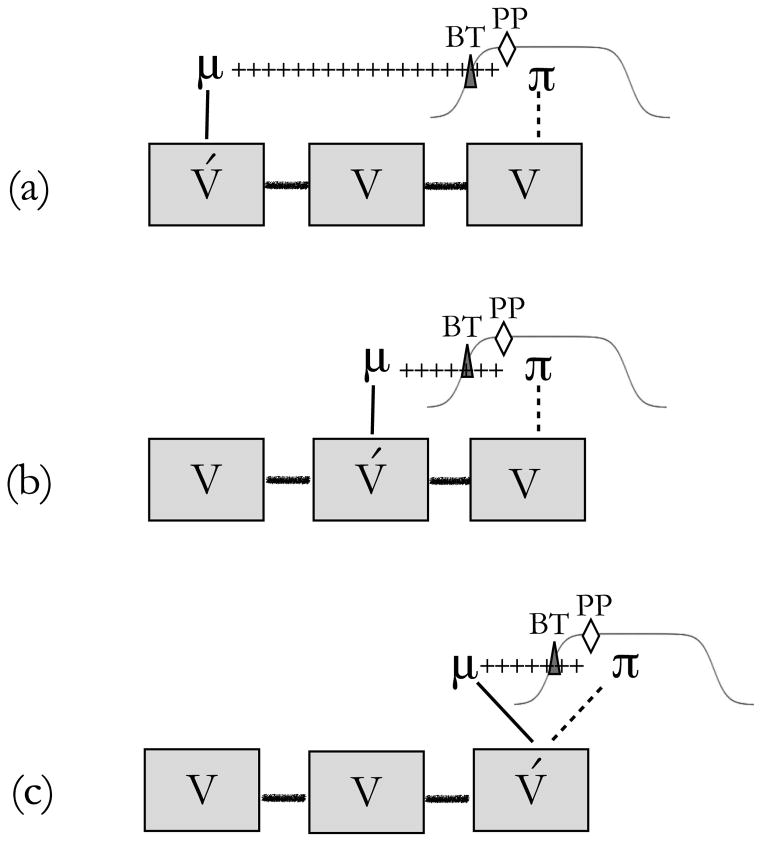

3.3 Coordination of pause postures

Before discussing these results, a brief parenthesis is opened here to present a set of interesting findings regarding the articulation during the acoustic pauses noticed in our data, which add significant support to the account of prosodic boundaries proposed in the Discussion (Section 4).

As mentioned in the Introduction (Section 1), the examination of boundary-related pauses was not targeted by our experimental design. However, a prominent number of pauses were observed in our data (approximately 98% of phrase-final words were followed by pauses), which, upon visual inspection of the articulatory data, were found to involve similar vocal tract configurations among speakers. A representative example of a pause posture is shown in Figure 8. This figure contains a screenshot of the analysis window during the part of a trial that includes the phrase-final word - which in this specific instance is stressed on the antepenult (S1: MAmima) - the pause, and the first word of the following phrase (metaKSI). The figure is organized in six panels. The first panel corresponds to an acoustic annotation of the data shown, the second and third panels include the corresponding waveform and spectrogram respectively, the fourth and fifth panels show the vertical axis of the tongue dorsum (TDz) and lip aperture (LA) respectively, and the sixth panel represents the F0.

Figure 8.

Instance of a pause posture, i.e., configuration of tongue dorsum and lips after an instance of phrase-final stress-initial word (S1: MAmima). The articulatory targets of the pre-boundary and post-boundary syllables (mɐ and mε respectively) are approximately located; the C ones at the lip aperture (LA) trajectory and the V ones at the vertical displacement of tongue dorsum (TDz) trajectory. The vertical line crossing all panels correspond the pause posture’s point of achievement, abbreviated as PP. White arrows point to the articulatory maxima preceding the first post-boundary C and V targets.

As the figure shows, the tongue tip and the lips after reaching the articulatory targets of the C (/m/) and V (/ɐ/) of the final syllable of the phrase retain a posture within the middle range of the vertical axis for the tongue dorsum vertical displacement and the lip aperture respectively for some substantial amount of time, before they move to a more extreme position, from which they start their opposite advancement towards their next constriction target in the post-boundary phrase (/m/ and /ε/). For instance, the lips move from a maximum aperture for the phrase-final vowel (/ɐ/) to a smaller long-lasting aperture followed by a larger short-lasting aperture (identified by the white arrow at the LA trajectory), very similar in size as for the phrase-final vowel (/ɐ/), during the pause, before they close again for the following phrase-initial consonant (/m/). These properties, which hold for all participants, indicate that this articulatory configuration during acoustic pauses corresponds to a default articulatory setting, possibly specific to Greek, during the pauses (cf. Gick, Wilson, Koch & Cook, 2004), which is called here pause posture. The fact that articulators reach a more extreme point after their middle-range long-lasting posture which is also in the opposite direction than their upcoming constriction target suggests that this posture is not just preparatory for an upcoming event, but rather, is related to the pause itself. Given that boundary lengthening, boundary tones and pauses behave hierarchically, with boundary lengthening becoming stronger the higher the prosodic level, boundary tones occurring only at strong boundaries, and pauses at even stronger boundaries (cf. Beckman & Elam, 1997), the observation of a large number of pauses in our data which involve similar vocal tract configurations among speakers raised the interesting questions of how these pause postures are coordinated with BT gestures. Some additional analyses were thus conducted to touch upon these issues. For these analyses, the point of achievement of pause postures (PP max) was used. PP max was defined as the onset of the long-lasting plateau at the tongue dorsum vertical displacement trajectory during the pause, and it was detected using the same method as for V maximal constrictions (see Section 2.4).

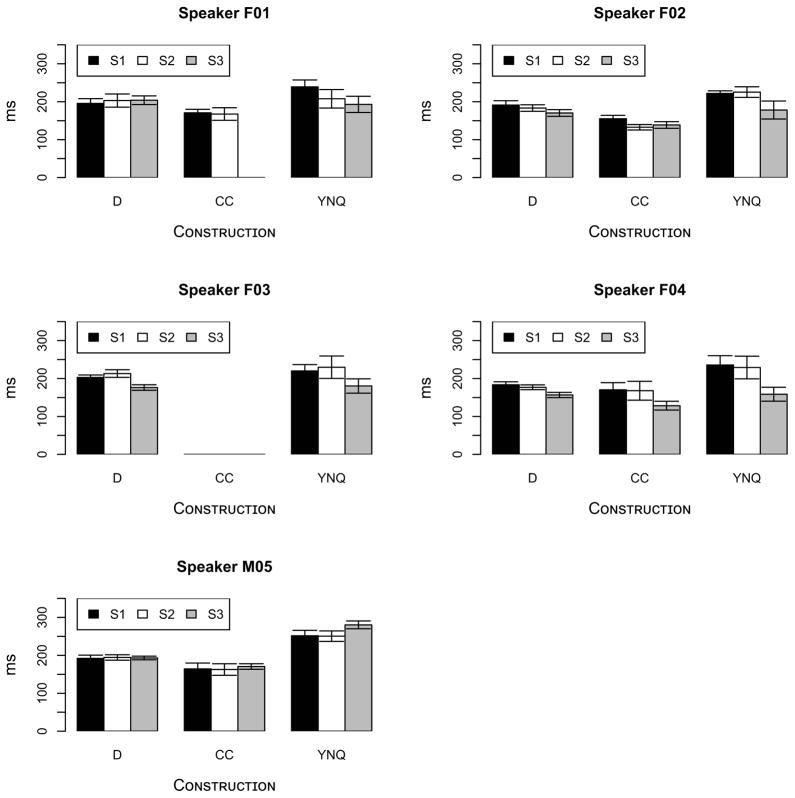

Here we focus on the coordination of pause postures (PP) with BT gestures. However, it is worth mentioning that these postures demonstrate stable spatial characteristics, but large temporal variability, and despite the considerable temporal variability, the duration of the PP formation movement is affected by lexical stress in such a way that these movements are longer in words with final stress than in words with non-final stress (Katsika, 2012). Regarding the coordination of pause postures with BT gestures, it was found that the position of lexical stress did not influence how long after the occurrence of the BT onset the pause postures reached their point of achievement (PP max). This was assessed by performing a set of planned comparisons (α = 0.05) to the interval measured from BT onset to PP max (BT-PP) with respect to the factor of Stress within each Construction per Speaker. The means and standard deviation of the BT-PP intervals are summarized in Figure 9. Only two planned comparisons were significant. Specifically, the BT-PP interval was shorter in stress-final (S3) than stress-initial (S1) words in the de-accented constructions for Speaker F04 (p = 0.03), and shorter in stress-final (S3) than stress-medial (S2) words in the de-accented constructions for Speaker F03 (p = 0.007).

Figure 9.

Mean and standard deviation of the temporal interval from BT onset to PP max (in ms) in stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05) for each Construction (D, CC, YNQ).

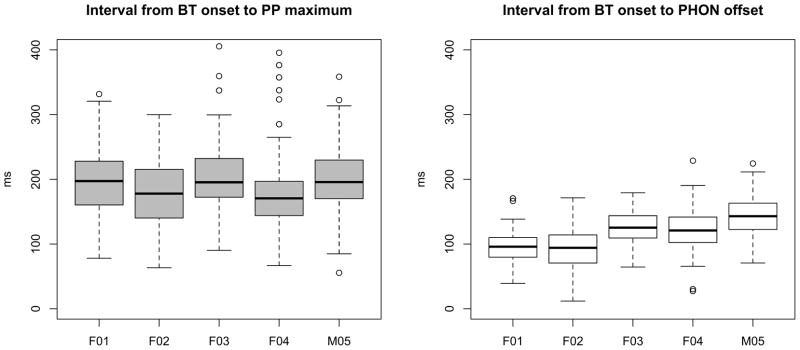

On the basis of these results, it can be concluded that lexical stress does not influence the timing between BT gestures and the following pause postures, suggesting a stable coordination between the two types of events. However, this result might also be confounded by the large variability that the BT-PP interval presents, shown in Figure 10. In order to exclude the latter possibility, the same analysis as for the BT-PP interval was also applied to the interval between the offset of phonation and BT onset. The offset of phonation occurs after the onset of the boundary tone and before the point of achievement of the pause posture, coinciding both with the acoustic offset of the final vowel and with the acoustic onset of the pause. The offset of phonation (PHON) was detected for each token using an automatic speech-to-text forced alignment algorithm (Katsamanis, Black, Georgiou, Goldstein & Narayanan 2011). As Figure 10 illustrates, the temporal interval between the onset of BT gestures and the offset of phonation (BT-PHON) is more stable and presents less variability than the interval between BT onset and PP achievement point for all Speakers, suggesting that any effect of Stress on the BT-PHON interval is unlikely to be a confound of variability.

Figure 10.

The variability of the temporal intervals (in ms) extending from BT onset to PP maximum (left panel) and PHON offset across Constructions per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05).

The mean Values (along with their standard deviations) of the temporal interval between the onset of BT gestures and the offset of phonation (BT-PHON) per Stress and Construction for each Speaker are given in Figure 11. The planned comparisons did not detect any systematic effect of Stress on the BT-PHON interval, with eight of the 45 comparisons being significant. In particular, in the de-accented constructions, Speakers F02 and M05 had longer BT-PHON intervals in stress-initial (S1) than either stress-medial (S2) or stress-final (S3) words [F02: S1 > S2 (p = 0.012) and S1 > S3 (p = 0.017); M05: S1 > S2 (p = 0.0322) and S1 > S3 (p = 0.0003)], while Speaker F01 had shorter BT-PHON intervals in stress-initial (S1) than stress-final (S3) words (p = 0.0031). In yes-no questions, the BT-PHON intervals of Speaker F04 were shorter in stress-final (S3) words than in either stress-initial (S1) (p = 0.0013) or stress-medial (S2) (p = 0.0064) words. Speaker F04 is also the only one showing a significant difference in causative clauses, with BT-PHON intervals being longer in stress-initial (S1) than stress-final (S3) words (p = 0.032).

Figure 11.

Mean and standard deviation of the temporal interval from BT onset to the offset of phonation (in ms) in stress-initial (S1), stress-medial (S2) and stress-final (S3) words per Speaker (F01, F02, F03, F04, M05) for each Construction (D, CC, YNQ).

To summarize, the position of lexical stress within the phrase-final word does not systematically influence the timing of the BT gesture with either the offset of phonation or the achievement of the pause posture, suggesting that the two latter events occur in a stable phase of the BT gesture.

4.0 Discussion

4.1. Summary of results and conclusions

The present study focuses on the coordination of boundary tones, and systematically investigates the effects of lexical stress separately from those of pitch accent on this coordination. The coordination of boundary tones with pause postures is also examined. To summarize the results of the applied analyses: