Abstract

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is an autoimmune disease resulting from the destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells. Cell-based therapies, involving the transplantation of functional β-cells into diabetic patients, have been explored as a potential long-term treatment for this condition; however, success is limited. A tissue engineering approach of culturing insulin-producing cells with extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules in three-dimensional (3D) constructs has the potential to enhance the efficacy of cell-based therapies for diabetes. When cultured in 3D environments, insulin-producing cells are often more viable and secrete more insulin than those in two dimensions. The addition of ECM molecules to the culture environments, depending on the specific type of molecule, can further enhance the viability and insulin secretion. This review addresses the different cell sources that can be utilized as β-cell replacements, the essential ECM molecules for the survival of these cells, and the 3D culture techniques that have been used to benefit cell function.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a condition characterized by deregulation of glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) by pancreatic β-cells. This deregulation can arise from autoimmune destruction of β-cells early in life (Type 1) or from a lack of insulin secretion or insulin resistance later in life (Type 2). The global incidence rate of diabetes mellitus was estimated to be ∼280 million in 2010 and is predicted to increase to 440 million by 2030,1 with type 1 diabetes accounting for ∼5–10% of all diabetes mellitus cases.2 The current gold standard for treatment of diabetes mellitus is administration of exogenous insulin in response to elevated blood glucose levels. Although this treatment requires constant glucose monitoring, the same level of control as endogenous insulin secreted from β-cells cannot be achieved. As a result, the patient is vulnerable to complications arising from hyperglycemia, such as severe dehydration, nausea, vomiting, increased urination, or even ketoacidosis in the short term.3,4 Over time nerve and blood vessels can be damaged, leading to neuropathy and blood vessel degeneration that manifests in symptoms ranging from numbness in extremities to complete loss of function and blindness. Although administration of exogenous insulin along with diet and exercise is sufficient to manage diabetes mellitus, this treatment does not cure the disease and requires continual patient compliance and vigilance. There is, therefore, a great need to develop alternative and long-term solutions to treating diabetes mellitus.

Cell-based therapies have been proposed as an alternative to exogenous insulin therapy, whereby islets, the endocrine cell clusters within the pancreas that contain β-cells, are implanted into the patient as a means to restore normal pancreatic function. Type 1 diabetes is defined by a loss of β-cell mass, and as such would benefit most from cell replacement therapy. The most notable breakthrough in cell-based therapies came with the advent of the Edmonton protocol in 2000, which involves transplanting islets obtained from cadaveric donors in conjunction with an immunosuppressive regimen. This protocol reversed hyperglycemia for 1 year in all seven patients who underwent islet transplantation.5 However, 5 years following transplantation, only 10% of patients remained insulin independent, with an average length of insulin independence of 15 months.6 With recent advancements in clinical approaches, patient response has been remarkably improved with 50% of patients remaining insulin independent for 5 years and more than 70% of implants retaining C-peptide secretion for 8 years.7 Despite this promising result, islet transplantation remains hampered by a lack of available donor tissue, the number of islets needed per patient, the need for immunosuppressants, and eventual loss of β-cell function over time.

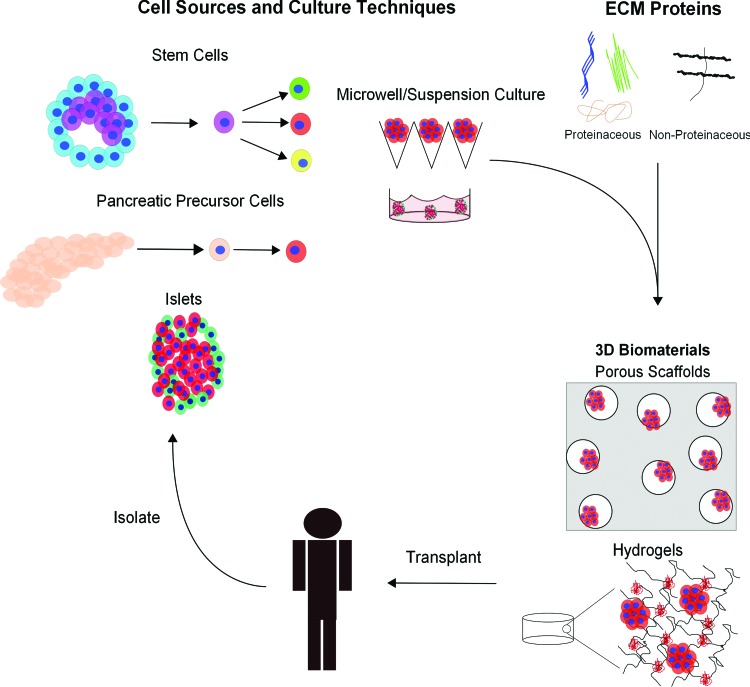

Tissue engineering has the potential to overcome many of the shortcomings of the Edmonton protocol leading to increased longevity of islet transplantations. The idea of tissue engineering for cell-based type 1 diabetes therapy is to combine cells, such as islets or more specifically β-cells, with biomaterials that provide mechanical support and a suitable extracellular environment to maintain cell survival and function in vitro and in vivo. Recent findings, which will be described in this review, point toward three-dimensional (3D) culture systems as a promising platform to improve the clinical outcome of islet transplantations and for directing differentiation of stem cells into β-cells. Therefore, a tissue engineering approach may be critical to identifying a long-term therapeutic solution for type 1 diabetes. Based on recent studies in the literature, three main components appear to be key for islet-based tissue engineering: (1) viable cells that can form into cell aggregates and release insulin in response to glucose; (2) extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules incorporated into a biomaterial to support cell survival, enhance differentiation, and improve the function of insulin-producing cells; and (3) a mechanically supportive biomaterial used as a scaffold or encapsulation system to deliver cells in vivo. This approach is illustrated in Figure 1. Within the context of pancreatic tissue engineering, this review highlights recent key findings within each of the aforementioned categories.

FIG. 1.

Schematic depicting different approaches being investigated for pancreatic tissue engineering, whereby insulin-producing cells are isolated or differentiated, placed in a culture platform, and transplanted in order to reduce glycemic levels. ECM, extracellular matrix. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Cell Sources and Culture Techniques

Many different cell types have the ability to serve as a transplantable cell source for the treatment of type 1 diabetes as long as they meet the clinical requirement, which is the release of insulin in response to elevated blood glucose without any adverse effects. In the pancreas, β-cells are the insulin-producing cells found in the Islets of Langerhans. Given the short supply of islets from donors, an active area of research is the production of insulin-producing cells derived from stem or progenitor cells.

Islets

The Islets of Langerhans are clusters of endocrine cells within the pancreas, typically ranging in size from 50 to 300 μm in humans.8 Islets are comprised of α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ cells, which contribute to digestion and glucose metabolism in different ways. The β-cell is the insulin-producing cell within islets and its loss of function leads to type 1 diabetes. Within human Islets of Langerhans, β-cells are the predominant cell type (range 32–77%; average 59%) and are located predominantly at the periphery of intra-islet blood vessels, though interspecies variation exists in the percentage and location of β-cells within islets.9 β-Cells function by releasing insulin in response to elevated blood glucose, whereby insulin interacts with many other tissue-specific cells (e.g., fat, muscle, and liver) to initiate their metabolism of blood glucose for energy. Islets isolated from cadaveric donors are the primary cell source approved for clinical use, but are limited due to donor availability. Islets from nonhumans have been investigated as an alternative. Porcine islets are the most common source, as human and porcine insulin vary by one amino acid.10 The number of preclinical trials with porcine islets in human patients is extremely limited though porcine islets have survived and functioned for up to 6 months in nonhuman primates with immunosuppression.11 Several preclinical trials using macro- or microencapsulation of porcine islets demonstrated efficacy for several years without the need for immunosuppressants.12 Nonetheless, islet transplantation remains an imperfect treatment due to limited long-term viability in vivo and the current need for a regiment of immunosuppressive drugs.13

Stem cells

Stem cells are defined by their ability to self-renew and differentiate into multiple cell types falling into one of two categories: pluripotent (having the ability to become all cell types in the body) or multipotent (having a restricted differentiation capacity). Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are the most commonly investigated for pancreatic differentiation, owing to their pluripotency, though investigators are searching for pancreatic stem cells and other β-cell progenitor cell types.

Embryonic stem cells

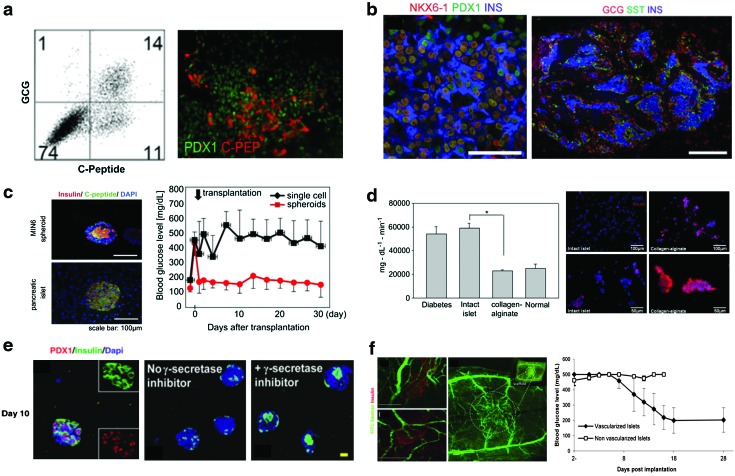

ESCs are derived from the inner cell blastocyst and characterized by their ability to differentiate into cells from all three embryonic germ layers. The basic concept currently employed for producing insulin-positive cells from ESCs is to mimic the environment surrounding islets during development by delivering growth factors at defined intervals. The reader is referred to several excellent reviews that describe the signaling pathways involved in pancreatic development.14–17 The first documented attempt to produce insulin+ cells from human ESCs was introduced by Lumelsky et al.18 This article followed a protocol established for neuronal differentiation to produce insulin-positive clusters, as the developmental pathways for the central nervous system and pancreas are similar. Further approaches have attempted to create cells that more closely resemble pancreatic β-cells rather than insulin-positive neural-like cells. The most successful approaches have employed a multitude of growth factors and pharmacological agents aimed at recapitulating the signaling cascades relevant to pancreatic differentiation in vitro.19 Overall, there has been success in obtaining insulin+ cells in vitro from ESCs, comprising up to 25% of the final population, but glucose responsiveness in vitro remains a challenge (Fig. 2a).20–27 However, ESCs differentiated into β-cell precursors—characterized by transcription factors that are critical to β-cell development and maturation, PDX1 and NKX6.1—have shown promise in vivo. When implanted into immunodeficient mice, these precursor cells were shown to mature into functional β-cells and reverse hyperglycemia (Fig. 2b).28,29 This finding indicates that the in vivo milieu provides critical cues for β-cell maturation and function, which has not yet been replicated in vitro, be it vasculature, ECM contacts, or other factors. However, the clinical use of partially differentiated ESCs remains limited due to their ability to form cysts and teratomas after transplantation. Despite the potential of ESCs to produce a limitless supply of pancreatic β-cells, current differentiation protocols will likely need to achieve in vitro glucose responsiveness and terminal differentiation before they can be applied in a clinical setting.

FIG. 2.

Representative culture techniques for insulin-producing cells and stem cell differentiation into β-cells. (a) Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into β-like cells, with up to 25% expressing C-peptide, a maker for insulin, reproduced with permission from The Company of Biologists.27 (b) Pancreatic precursors derived from hESCs differentiate into functional glucose responsive islet-like structures that revert hyperglycemia when implanted in vivo and allowed to mature, reproduced with permission from Nature Publishing group.29 (c) Suspension culture of MIN6 cells creates islet-like structures that reverse hyperglycemia in vivo, while single cells do not, reproduced with permission from Elsevier.60 (d) Islets cultured in collagen alginate microbeads express more insulin than those in suspension culture (*, P<0.05), reproduced with permission from Elsevier.102 (e) Aggregated pancreatic precursor cells cultured in poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels with collagen I and gamma secretase inhibitor become insulin-positive β-like cells, reproduced with permission from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers.116 (f) Islets cocultured with human umbilical vein endothelial cells on a poly(lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) scaffold become vascularized upon implantation and reverse hyperglycemia.99 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Induced pluripotent stem cells

iPSCs are derived from terminally differentiated somatic cells that, through the induction of genes found in pluripotent cells and downregulation of genes of the differentiated state, regain traits of ESCs.30,31 This process offers an autologous cell source thus mitigating the need for immunosuppressants and overcomes the ethical concerns associated with ESCs. A few studies have subjected iPSCs to directed differentiation protocols similar to those used with ESCs and successfully produced insulin+ cells at similar percentages to that obtained for ESCs.25,32–34 Additionally, pancreatic precursor cells derived from murine or rhesus monkey iPSCs were found to reverse diabetes in immunodeficient mice after a month-long maturation period in vivo.35,36 The safety of iPSCs, which typically are produced through adenoviral delivery systems that can activate known oncogenes, needs further investigation before clinical implementation can be pursued.37

Mesenchymal stromal cells

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are fibroblast-like cells derived in the bone marrow, which have the ability to differentiate down several cell lineages, notably osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages.38 Recent studies have explored the possibility of differentiating MSCs into pancreatic endocrine cells including β-cells, but with limited success.39–41 A few studies have injected MSCs into diabetic mice or pigs and demonstrated a reduction in blood glucose, though this appears to be due more to a regeneration of host β-cell mass rather than differentiation of MSCs into β-cells.42,43 β-Cell regeneration is believed to be due to the immunomodulatory and angiogenic effects of MSCs, though the exact mechanism is not known.44 The most widely adopted use of MSCs is in coculture with implanted islets, which has been shown to improve the clinical outcome by revascularizing the transplant and protecting the islets from immune attack. The use of MSCs appears to be primarily immunomodulatory though the ability of these cells to differentiate into insulin-producing cells and is still being researched. A recent review summarizes the potential use of MSCs in islet transplantation.45

Other pancreatic cell types

Attempts have been made to produce insulin+ cells from cells that have a developmentally similar background to β-cells. Pancreatic acinar and ductal cells have been proposed as a population of cells that can differentiate into β-cells.46–48 Other studies have investigated the feasibility of transdifferentiating hepatocytes or other endocrine cell types into β-cells, which share a common progenitor with pancreatic β-cells.49–51 The basic concept involves dedifferentiating the cell population back to its progenitor state and then redifferentiating the progenitors into β-cells. To date, these cell populations and approaches have been unsuccessful at producing functional β-cells that reverse hyperglycemia in vivo.52 However, this is an active area of research and, if successful, would offer a viable cell source for tissue engineering. Pancreatic precursor cells, which can be readily isolated from prenatal mice, express a number of genes indicative of their commitment toward a pancreatic phenotype, but not insulin. As such, they may be a useful cell source to identify conditions to coax precursor cells into functional β-cells in vitro.

Cell lines for use in research

Although cell lines are not clinically relevant, owing to their origin from cancer cells, they can nonetheless serve as an important tool for studying β-like cells and developing strategies for pancreatic tissue engineering. Several cell lines retain some resemblance of normal β-cell function (weak glucose responsiveness and insulin secretion) and have been utilized in diabetes research.53 From a tissue engineering perspective, some of the most commonly used pancreatic cell lines are RINm5F (rat), INS-1 (mouse), β-TC (mouse), and MIN6 (rat), with only MIN6 cells exhibiting glucose-stimulated insulin release.54–56

Suspension

Suspension culture has been investigated as a means to culture and preserve islet structure in vitro prior to implantation or encapsulation in biomaterials. Long-term suspension culture has been largely unsuccessful due to the lack of cell–matrix contacts, which are lost during the isolation process leading to apoptosis.57 On the other hand, suspension culture has been proposed as a method to aid in the differentiation of stem cells toward islet-like fates by creating and/or maintaining structures similar to aggregated endocrine cells.58 For example, when preaggregated hESCs in the form of embryoid bodies were grown in suspension culture with differentiation factors, 5–20% of the total population was PDX1 positive.23 There was large variability among aggregates, with some releasing C-peptide, a marker of insulin secretion, in response to glucose, while others were unresponsive to glucose stimulation, but none were able to lower blood glucose levels when implanted into a mouse diabetic model.23 However in a different study, hESCs were aggregated into 100–200-μm-diameter spherical clusters and subjected to a directed differentiation protocol in suspension culture.29 The resulting cell population had 40–65% cells that showed immature endocrine or poly-hormonal markers, 16–47% cells that expressed pancreatic endoderm markers, and 7–32% that expressed PDX1+ cells. When implanted into diabetic mice, the aggregates were able to reverse diabetes after 9–11 weeks.29 Overall, these promising studies demonstrate that it is possible to differentiate stem cells in suspension into pancreatic precursor cells, though direct comparisons to two-dimensional (2D) differentiations were not included.

Another benefit of suspension culture is scalability, as many commercial biological processes are performed in large perfusion bioreactors. The ability to create a clinically relevant number of β-like cells for transplantation under good manufacturing practice and in a high-throughput manner will be essential for the clinical implementation of stem-cell-derived islet transplantation. In one study, a rat β-cell line (β-TC6) was grown in 3D rotational bioreactor containing collagen-coated microbeads acting as nucleation sites for cell aggregation and their subsequent release.59 This culture method produced cells with higher gene expression levels of PDX1, NeuroD, Insulin1, and Ngn3—all β-cell or precursor markers—and were more responsive to glucose challenge when compared with 2D cultures. Another approach utilized a clinostat, a simulated microgravity generator, to create large numbers of MIN6 cell aggregates that were consistently ∼200 μm and stained positive for C-peptide and insulin (Fig. 2c).60 Combining defined differentiation approaches with high-throughput suspension culture systems will likely aid in producing a large number of β-like cells in a reproducible fashion.

Micropatterning/microwell technology

Micropatterning and microwell technologies have been utilized as a means to control aggregate size and study its effect on cell growth and differentiation of ESCs and the function of primary cell types. In microcontact printing, proteins are patterned onto a surface to localize cell attachment and promote cell aggregation. A study utilizing microcontact printing to create size-controlled hESC-derived aggregates demonstrated that smaller aggregates (200 μm) expressed higher levels of endoderm markers while larger aggregates (800 μm) expressed higher levels of neural markers.61 Similar microcontact printing techniques have been utilized to effectively differentiate hESCs into size-controlled islet-like clusters expressing PDX1, though the effect of aggregate size on differentiation efficiency was not considered.24,62

Microwell technology is another technique to create size-controlled aggregates of defined dimensions created by micromolding or photocontact lithography. In one study, MIN6 cells were aggregated into clusters ranging from 100 to 300 μm in diameter using microwells of defined sizes.63 The aggregates released more insulin than an equivalent number of single cells, but no aggregate-size-dependent response was observed. Additionally, when these aggregates were encapsulated in a synthetic hydrogel, they remained more than 90% viable after 1 week in culture while the viability of encapsulated single cells was below 10%. In another study, human pancreatic ductal epithelial cells cultured in a microwell encapsulation system (consisting of wells from 150 to 500 μm in size with polycapralactone-gelatin nanofibers lining the bottom of the wells) produced insulin after 21 days of culture.64 Microwell and micropatterned techniques offer platforms to produce well-defined aggregates; however, the optimal aggregate size for β-cell function and differentiation of stem cells into functioning β cells remains to be elucidated.

ECM Cues

Pancreatic islets are highly vascularized endocrine cell clusters that are in intimate contact with the basement membrane of endothelial cells and other exocrine cells in the pancreas. From a tissue engineering standpoint, knowledge of the extracellular signals present in pancreatic islets can be utilized to design biomimetic scaffolds capable of maintaining islet function. The ECM has several functions, such as providing structural support, acting as a reservoir for growth factors, and signaling to cells through integrin-mediated interactions.65 Two recent reviews detail knowledge to date regarding essential ECM molecules and integrins that maintain islets in vivo.66,67 Laminin-111 has been implicated in the development of the pancreas, while laminins-332, 441, and 511 are found in the basement membrane of the adult pancreas.68,69 Collagens I, IV, and V are also components of the basement membrane, though other ECM molecules, such as vitronectin and fibronectin, are known to have roles in pancreatic development.70,71 A recent study of decellularized mouse pancreas identified several proteins present in the basement membrane, among them collagens I, III, V, and VI; laminins-111, 211, and 511; nidogens; and proteoglycans.72 However, the exact role of specific ECM molecules in maintaining islet function is still under investigation. Table 1 summarizes key findings for different ECM molecules and their effect on various insulin-producing cell types. While many of these studies utilized 2D cultures, they provide valuable information regarding the role of different ECM molecules in maintaining functional islets, which can be applied to the design of 3D biomaterials.

Table 1.

Summary of Experimental Findings Involving Insulin-Producing Cells Cultured on Extracellular Matrix

| ECM component | Isoform | Cell types | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laminin | 111 332 411 511 |

Purified β-cells Adult rat islets80,83,84 Fetal rat islets75–77,81,82 hESCs24 MIN669 |

Enhanced viability75–79 and insulin release81–84 compared to TC plastic; less vimentin+ mesenchymal cells80,83,84; enhance differentiation of hESCs toward pancreatic cells24; enhanced insulin gene expression69 |

| Collagen | I IV V |

Rat islets77,83 Human islets81,82,88 |

Facilitates attachment, spreading, and maintained viability of cultured islets77,81,83; Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition over time81; increased insulin over islets on TC plates82,88 |

| Fibronectin/vitronectin | Rat islets77,78,82,83,90 hESCs62 |

Maintain viability and insulin release initially, though over time viability decreases77,82,90; 3D morphology maintained in culture78,83; aids in the differentiation of hESCs to pancreatic precursor cells62 |

ECM, extracellular matrix; hESCs, human embryonic stem cells; 3D, three-dimensional.

Laminin

Laminin is a major component of basement membranes, is present in blood vessels and acinar cells within the pancreas, is distributed within and around islets at the exocrine-endocrine transition, and is present in intra-islet blood vessels.73,74 Because it is an integral part of the extracellular environment of islets in vivo, many studies have investigated islet function on 2D cultures with different laminin isoforms. For example, laminin-111 associated with the pancreatic ductal epithelium has been shown to enhance differentiation and expansion of fetal mouse islets,75 selectively enhance the number of insulin+ cells,76 and maintain viability of adult rat islets for several days.77 Human β-cells attached, spread, and survived on the basement membranes of lysed human 5637 cells, but not on lysed rat 804G cells, both of which are rich in laminins.78 Rat islets, however, spread and secreted insulin with reduced apoptosis when cultured on the basement membranes of lysed 804G cells.78 These studies suggest that cell–matrix interactions may be species specific.79 In a separate study, human islets cultured on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) exhibited an epithelial-mesenchymal transition as evidenced by the expression of the mesenchymal marker vimentin, while those cultured on laminin isoforms (lanimin-411 or 511) exhibited reduced proliferation but retained their β-cell phenotype and insulin gene expression levels.69,80 Fetal islets, dissociated and reaggregated into islet-like cell clusters and cultured on laminin-111, retained their aggregated structure, became less vimentin+ (<50% after 5 days), retained insulin gene expression, and had insulin release values 2.6 times higher than islets cultured on bovine serum albumin (BSA)–coated plates.81,82 Several studies have shown that islets cultured on laminin only weakly attached to the surface,83,84 suggesting that minimal spreading in addition to integrin-mediated events may be important to retaining insulin+ cells while minimizing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Additionally, laminin appears to enhance the differentiation of hESCs into insulin+ cells.24 When hESCs were cultured on 100-μm-diameter, microprinted laminin-coated coverslips under a directed differentiation protocol, the cell clusters exhibited gene expression profiles resembling definitive endoderm, the developmental precursor of pancreatic cells. When detached and further differentiated in suspension culture, a small fraction (<5%) of cells expressed pancreatic transcription factors PDX1 and NKX6.1.24 Overall, it appears as though laminin plays an important role in maintaining islet function and insulin release in vitro and in supporting differentiation of hESCs into β-cell precursors.

Collagen

Collagen IV is also a major component of the basement membrane and collagen types I, IV, V, and VI are present at the exocrine-endocrine interface and in proximity to intra-islet endothelial cells.73,85 Collagens I, V, and VI are the most abundant isoforms within the islet-exocrine interface of the human pancreas, with only weak expression of collagen IV, though collagen IV is strongly expressed in the epithelial basement of the fetal pancreas.86,87 Collagen IV is present in the developing human pancreas and is implicated in the development of islet structure as evidenced by its proximity to budding clusters of insulin- and glucagon-positive cells.87 In 2D culture, rat islets cultured on collagens I and IV remained 60% and 89% viable, respectively, while over 90% of those cultured in suspension underwent apoptotic death after 48 h.77 Within 24 h of plating, islets on collagens I and IV had four and six times the insulin release, respectively, of those on BSA-coated or standard poly-D-lysine plates.82,88 However, after 5 days of culture, 81% of islets cultured on collagen IV were vimentin+, with a 70% reduction in insulin transcription compared with day 0,81 indicating their transition into mesenchymal-like cells.83 Interestingly, islets that form a monolayer on a collagen I surface followed by overlaying a second layer of collagen above the cells were able to form islet-like aggregates and maintain a basal level of insulin release over 8 weeks, implicating 3D matrix contacts as being important to preserving islet structure in vitro.89 Despite the ability of islets to attach and proliferate on collagen I- and IV-coated surfaces, the observed epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition limits the usefulness of these substrates for in vitro 2D culture. As collagen IV is predominantly observed in the developing pancreas and is believed to facilitate the formation of islets, it may be a more suitable substrate for the directed differentiation of stem cells.87 Other isoforms, like collagens V and VI, may be successful at enhancing islet function in vitro, though little work exists using these substrates.

Fibronectin/vitronectin

Fibronectin and vitronectin are present in the developing pancreas, but are not present in abundance in adult islets.67,87 Fibronectin is expressed in blood vessels and ductal cells of the developing pancreas while vitronectin is expressed in epithelial cells adjacent to ductal structures.87 Despite the uncertain role of fibronectin and vitronectin in mature islets, both have been studied in 2D culture of islets. For example, rat islets cultured on fibronectin exhibited initially high viability (85–90%) after 24 h, which decreased to 43% after 7 days.77,90 Generally, islets do not attach strongly to fibronectin nor do they spread during culture.78 Despite the weak binding to fibronectin or vitronectin, islets cultured on these substrates released 3.6 and 5.4 times more insulin, respectively, than those on BSA-coated plates after 24 h.82 Islets cultured on fibronectin were less spread than those on collagens I and IV and even laminin, and appeared most normal in terms of morphology and insulin release.83 However, viability was not retained in long-term studies.83 Given the role of these two proteins in development, hESCs were grown and differentiated on microprinted 150–200-μm spots of fibronectin and vitronectin. These proteins aided in hESC differentiation toward definitive endoderm, the precursor to gut, thyroid, pancreas, and liver, and interestingly to a greater degree when compared to other ECM proteins (collagens I, III, IV, and V and laminin).62 The hESCs plated on a combination of fibronectin and vitronectin and differentiated toward definitive endoderm had a higher number of definitive endoderm-positive cells than those plated on matrigel (81.4% vs. 59.1%). In cells differentiating toward definitive endoderm, the integrins ITGA5, ITGAV, and ITGB4 were found to be upregulated, all of which bind fibronectin and vitronectin. Selecting for cells that were ITGA5+/ITGAV+ led to subsequent enhancements in the differentiation efficacy toward primitive gut tube, indicating development toward stomach, liver, or pancreas. Fibronectin and vitronectin are important components of the fetal pancreas, and may be useful in the differentiation of stem cells to islets but their importance in maintaining mature islets appears to be less clear, as long-term viability on these substrates is a concern.

Nonproteinaceous matrix components

Transmembrane glycoproteins in islets are comprised of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), including heparin sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS), which modulate cellular interaction with ECM and growth factors. Perlecan, also known as heparin sulfate proteoglycan 2, and CS are also present in the basement membranes of islets, though the role of these molecules in islet function is unclear. The reader is referred to a recent and thorough review describing the structure and function of many proteoglycans and their proposed roles in islet function.66 Recent work has demonstrated that insulin-producing cells within mouse islets express high levels of transmembrane HS associated with syndecan-4.91 Syndecan-4 is involved in FGF-2 signaling, a pro-survival factor, and therefore may be important to β-cell survival.92 Other studies have shown that HS is essential for islet survival, with intracellular levels of HS in dissociated islets diminishing 67% after isolation, corresponding to a twofold increase in cell death.93 These studies illustrate that in addition to proteinaceous matrix of the basement membrane surrounding islets, transmembrane glycoproteins are critical to maintain during the isolation procedure for survival and function postisolation.94 Further work is needed to elucidate the nature of GAGs and glycoproteins in cell–ECM interactions so that this knowledge can be applied to designing functional materials to sustain islet function.

Three-Dimensional Biomaterials

Three-dimensional culture systems present several advantages over traditional 2D culture. By maintaining cells in more physiologically relevant structures and preserving cell–cell and cell–matrix contacts, the in vivo environment can be more closely imitated. This consideration is particularly relevant when islets are the cell population in culture, owing to the numerous cell–cell contacts among endocrine cells and cell–matrix contacts among endocrine cells and the surrounding basement membrane. With islet transplantation, the isolation process often destroys the extracellular environment leaving islets prone to a loss of function over time after transplantation. Restoring ECM contacts and mechanical support of isolated islets may increase the long-term success of islet transplantation. There are numerous examples demonstrating that 3D cell culture is more physiologically relevant than monolayer culture, ranging from cancer research and stem cell differentiation, to the ex vivo culture of many cell types.95 Therefore, 3D culture is likely to play an important role in the in vitro culture of pancreatic cells and their delivery in vivo. Table 2 summarizes key findings associated with culturing insulin-producing cells or stem cells in three dimensions.

Table 2.

Summary of Three-Dimensional Culture Techniques for Pancreatic Tissue Engineering

| Culture platform | Modifications | Cell types | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suspension | MIN660 | Directed differentiation into β-like cells that can reverse hyperglycemia29,58; suspension culture of MIN6 aggregates lowers blood glucose levels60 | |

| β-TC659 | |||

| hESCs23,29 | |||

| Mouse fetal pancreatic cells58 | |||

| Microwell/micropatterning | MIN663 | Consistent production of size-controlled (200–800 μm) aggregates24,62–64; increased insulin release compared with single cells but no size-dependent correlation63 | |

| Human ductal epithelial cells64 | |||

| hESCs24,62 | |||

| Porous scaffold (PLLA, PLGA) | Extracellular matrix; RGD | Islets96,97,99,105,106,125 | Cells cultured on a scaffold have increased viability and insulin release compared with those cultured in 2D96–99,105,106,125; the inclusion of ECM molecules within the scaffolds enhances insulin release97,98; islets implanted in vivo in a scaffold become vascularized and lower blood glucose levels99,125 |

| RIN98 | |||

| Coculture with HUVECs and fibroblasts99 | |||

| Hydrogel | Collagens I and IV; laminin; GLP-1; IL-1; peptide motifs for collagens I and IV and laminin | Rat islets104,108,107,121,126 | Cells cultured in a hydrogel have higher viability compared with 2D102,104,107,110,111,119–122,126; the inclusion of ECM molecules within the scaffolds enhances insulin release110,111,108; aggregation of cells prior to encapsulation facilitates survival and insulin release120,114–116; MSCs enhance insulin release122,123; differentiation of stem cells to β-like cells when cultured in hydrogels109,114–116; islets in hydrogels can reverse hyperglycemia102,107,121,126 |

| Human islets122,104 | |||

| MIN6102,104,110,111,117–120 | |||

| Rat pancreatic precursors114–116 | |||

| Coculture with MSCs122,123 | |||

| Mouse ESCs109 | |||

| RIN103 |

HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MSCs, mesenchymal stromal cells; 2D, two-dimensional.

Three-dimensional porous scaffolds

Seeding cells onto prefabricated porous scaffolds has been investigated as a means to enhance viability and function of isolated islets in vitro and to improve the outcomes of islet transplantations. For example, rat islets cultured in a porous poly(glycolic acid) (PGA) scaffold were nearly twofold more viable and had fourfold greater insulin secretion when compared to those cultured on untreated TCPS in 2D after 15 days.96 In a separate study, human islets were entrapped in a collagen gel containing fibronectin and collagen IV within the pores of a poly(lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) scaffold.97 Interestingly, the islets within the PLGA scaffold maintained a glucose stimulation index similar to that of fresh islets and better than those cultured in a 3D collagen I gel, but in the absence of the scaffold, or those cultured in suspension. Further, β-cell-specific gene expression levels were also elevated (e.g., three- to fivefold greater than 3D culture in ECM alone) in islets cultured within the PLGA/ECM scaffold, suggesting that a 3D structural support provided by the pores was critical to maintaining islet function.97 In a different study, cells from an insulin-producing cell line (RIN-m5F) were cultured on a scaffold comprised of woven PLGA with the pores filled with a collagen I microfiber mesh, which was subsequently coated with ECM molecules (laminin, fibronectin, vitronectin, or type IV collagen) or poly (L-lysine).98 Insulin secretion in the 3D scaffolds was approximately twice that of cells maintained in 2D culture. These results demonstrate the importance of both cell–matrix contacts and the structural support provided by a scaffold in sustaining islet function in vitro and in enhancing islet function upon transplantation.

Another benefit of using scaffolding materials is the ability to coculture multiple cell types and create environments resembling aspects of native tissue structures with ECM interactions and proximity to vasculature. This was demonstrated in a study whereby mouse islets, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, and human foreskin fibroblast mesenchymal cells were cocultured on porous PLLA/PLGA scaffolds (Fig. 2f).99 This triculture system improved islet viability (75% viable after 4 weeks in vitro) compared to 2D controls (no survival past 2 weeks). In addition, the inclusion of fibroblasts and endothelial cells in 2D or 3D led to increased expression of several pancreatic genes from encapsulated islets (INS, GCG, PDX1, NKX6.1, and Glut2), which were further upregulated in 3D. Islets in the triculture 3D system had ∼50% greater insulin release than those cultured in 2D. Islet function is mediated by interactions with surrounding tissue and vasculature in vivo, and these studies suggest that coculture with endothelial cells benefits in vitro function as well.

Hydrogels for cell encapsulation

Hydrogels are highly water-swollen crosslinked polymers that can be formed from biocompatible natural or synthetic polymers in aqueous medium and under benign conditions enabling encapsulation of cells.100 As such, they have been the most widely investigated materials for delivery of pancreatic cells for diabetes therapy. Alginate microcapsules have been one of the most commonly investigated hydrogel materials for pancreatic tissue engineering. Alginate is an unbranched anionic polysaccharide comprised of repeating units of 1,4-linked α-L-guluronate and β-D-mannuronate, which is derived from the cell walls of brown algae. Alginate binds divalent cations, such as Ca2+ or Ba2+, and assembles into an “egg box” like crosslinked networks under cytocompatible conditions.101 Alginate microcapsules have been explored as a means to encapsulate individual islets though creating long-lasting, uniform, and stable microcapsules remains an issue. Various attempts have been made to modify alginate microcapsules either with ECM molecules to facilitate cell adhesion or different stabilizing crosslinkers. For example, rat islets were encapsulated in alginate or an alginate/collagen mixture (Fig. 2d).102 The alginate/collagen-encapsulated spheroids maintained their viability after 1 week (75%) while alginate-encapsulated spheroids were only 35% viable, which was lower than 2D cultures (50%). In a separate study, RIN-m5f cells were encapsulated in barium-alginate or calcium-alginate with or without poly-L-lysine or poly-L-ornithine and ECM molecules.103 Barium was more stable than calcium in maintaining crosslinking owing to the fact that Ba2+ can bind mannuronate in addition to guluronate. The presence of poly-L-lysine or poly-L-ornithine in the barium alginate microbeads increased cell proliferation, while the inclusion of collagen or laminin enhanced insulin release. To create even more stable alginate microbeads, alginate was crosslinked with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and used to encapsulate MIN6 cells, rat islets, and human islets.104 In this hydrogel system, proliferation of MIN6 cells was significantly greater than alginate-only microbeads after 7 days of culture. While rat and human islets were glucose responsive, their GSIS (the ratio of insulin released under high-glucose stimulation to the insulin released under low-glucose stimulation) and cell viability was similar in the PEG alginate and alginate-only microbeads after 1 week. Alginate microcapsules are capable of encapsulating individual islets in a stable and mechanically supportive environment, an important consideration for successful long-term transplantations.

Several other naturally derived hydrogels have been studied for the encapsulation of islets or their precursors. For example, a peptide amphipile nanostructured gel-like structure was engineered to contain the cell adhesion binding domain RGD and MMP-2 cleavable sequences to impart degradation.105,106 When rat pancreatic islets were encapsulated in these hydrogels, they had higher GSIS and higher viability when compared to suspension culture or culture on a mesh nanoinsert. Additionally after 14 days, nanofiber-encapsulated islets remained insulin positive and released insulin in response to glucose stimulation, while those cultured in suspension were weakly insulin positive and only observed at the periphery of the islets. A composite saccharide-peptide hydrogel was also developed whereby encapsulated rat islets remained viable up to 4 weeks, while the unencapsulated islets were mostly nonviable after 2 weeks.107 Silk hydrogels have been studied for the encapsulation of mouse islets showing that the addition of collagen IV and laminin led to a twofold enhancement in insulin release compared with silk hydrogels alone.108 In another study, murine ESC aggregates encapsulated in a collagen I gel exhibited enhanced expression of β-cell-specific genes and GSIS over 2D culture.109 In this system, 46% of the clusters were positive for DTZ, a marker indicative of pancreatic β-cells, while only 7% were DTZ positive in 2D culture (however, expression levels were below that of freshly isolated islets). The GSIS levels were also higher by 3.3-fold in 3D compared with 2D cultures. Natural hydrogels, especially those modified with ECM molecules, have been shown to enhance the viability and insulin secretion of encapsulated islets.

However, because natural polymers can be immunogenic and are not easily tuned (e.g., mechanical properties), synthetic polymers such as poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) have been utilized to form hydrogels for pancreatic tissue engineering. Given the importance of cell–matrix interactions for islets and their precursors, synthetic hydrogels are often modified with ECM molecules like collagens I and IV or laminin, or small peptides. For example, insulin release from MIN6 cells encapsulated as single cells within PEG hydrogels was significantly enhanced with the addition of collagen IV, laminin, or combinations thereof.110,111 Interestingly, a 3:1 laminin:collagen ratio resulted in the highest insulin release and was sevenfold higher compared to cells in PEG-only gels, with no detectable insulin release from unencapsulated cells. Further analysis was performed to determine the key binding motifs in laminin (IKLLI, IKVAV, LRGDN, PDSGR, and YIGSR)112,113 and collagen (DGEA). Interestingly, only IKVAV showed enhancement in insulin secretion (three times more than unmodified) by encapsulated cells over 2 weeks. However, total insulin release from MIN6 cells in the gels with peptides mimicking laminin or collagen was two to five times lower than cells in gels with the entire proteins, suggesting that multiple domains of cell interaction and/or conformation of the domains are important. In a separate study, murine pancreatic precursor cells (isolated from day-15 dorsal pancreatic buds and dissociated into single cells) were encapsulated in PEG hydrogels for 1 week. These precursor cells were vimentin positive in 2D culture, but when encapsulated the β-cell-specific genes (e.g., MafA and Ins) were upregulated and the cells released insulin (but not in a glucose-responsive manner).114 The inclusion of collagen type I into the PEG hydrogels, however, led to glucose-responsive cells.115 Differentiation was further enhanced in 3D culture by inhibiting notch, which in vivo is responsible for maintaining undifferentiated cells, resulting in upregulation of pancreatic genes (Hes1, Ins, PDX1, glut2, MafA, and GCG) and higher GSIS values (Fig. 2e).116 Non-ECM-derived peptides have also been investigated as a means to enhance cell survival. For example, PEG hydrogels immobilized with antiapoptotic glucagon like peptide 1 and IKVAV improved the viability of encapsulated MIN6 single cells, but long-term survival remained low.117 Viability was also improved in MIN6 cells with the inclusion of a blocking peptide for interleukin-1 receptor and RGD when exposed to inflammatory cytokines.118 While PEG hydrogels have shown promise, a recent study has demonstrated that when formed by free radical polymerization, MIN6 cell viability is much lower in hydrogels formed from PEG diacrylates when compared to gels formed from a thiol-ene click chemistry,119 suggesting that the method to form hydrogels must be considered. Taken together, these studies reveal that synthetic hydrogels are promising platforms for pancreatic tissue engineering, but that the inclusion of ECM mimetics is critical to enhancing not only survival but also differentiation and function.

Another factor that has been considered in the death of cells in hydrogels is anoikis due to a lack of cell–cell contact or cell–cell signaling. Studies have shown that for MIN6 cells encapsulated in PEG hydrogels a higher concentration of cells at the time of encapsulation (2×107 cells/mL) leads to the formation of viable cell clusters while lower cell concentrations at the time of encapsulation (5×106 cells/mL) tend to result in cells remaining as single cells that eventually die.120 A higher concentration of cells at encapsulation also led to higher GSIS levels (e.g., 1.7 for 2×107 cells/mL and 0.8 for 6.7×106 cells/mL). Further, preaggregating MIN6 cells prior to encapsulation improved viability, with the cells remaining >95% viable after 3 weeks in culture.121 Similar results were observed with encapsulated mouse islets.110 These studies indicate that cell–cell communication, whether it be cell–cell contacts, paracrine signaling, or a combination, is important for cell viability and cell insulin secretion, especially for cells encapsulated in hydrogels.

A few studies have investigated coculturing islets with other cell types in hydrogels as a means to enhance islet function. For example, when cadaveric human islets were cultured in a collagen gel populated with fibroblasts, their GSIS levels were maintained after 1 week, but fell when cultured in a collagen matrix alone.122 Both conditions were nonetheless responsive to glucose, whereas 2D cultures were not. Similarly, mouse islets exhibited higher insulin release when cocultured with MSCs in a hydrogel containing collagen and laminin compared with those in a hydrogel containing just the ECM components.108 Additionally, the insulin secretion from INS-1 cells cocultured with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) was greater than when just INS-1 cells were cultured.123 While the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated, it is thought that basement membrane proteins secreted by endothelial cells, which have been shown to enhance the function of β-cells,69 contribute to the increased insulin secretion observed in the coculture system in vitro. Additionally, MSCs are known secrete anti-inflammatory or antiapoptotic growth factors, which can enhance islet viability in vitro.

Preclinical Advancements

Several studies have investigated the ability of islets, which are precultured in various 3D environments in vitro and then transplanted, to reverse hyperglycemia in immune-compromised mice. For example, when murine islets cultured in PLGA scaffolds containing different ECM proteins were transplanted into mice with chemically induced diabetes, the condition was reversed as evidenced by lower blood glucose levels.124 Of the ECM proteins tested, collagen IV led to the fastest response (basal blood glucose lowered from 300 mg/dL to below 200 mg/dL in ∼4.4 days) compared with laminin and fibronectin, which required 27 days, and PLGA-alone scaffolds, which required 36 days, to lower blood glucose levels. In this same study, mice were subjected to a glucose challenge and islets on the collagen IV PLGA scaffolds reduced blood glucose levels within 60 min, while those on the fibronectin, laminin, and PLGA-alone scaffolds required ∼120 min. Further, the presence of ECM improved neovascularization of the scaffolds, a critical factor for the long-term survival of transplanted islets. Another study using islets cultured on PGA scaffolds confirmed the importance of the 3D environment over injection of islets alone, which were precultured in 2D, showing a twofold reduction in blood glucose levels (257 mg/dL vs. 536 mg/dL) in nude mice.125 Other studies have also shown that islets encapsulated in synthetic hydrogels are capable of reversing hyperglycemia in nude mice, while unencapsulated cells are not.121,126 For example, islets encapsulated in a saccharide-peptide hydrogel or in collagen-alginate microbeads and transplanted into nude mice reversed hyperglycemia (blood glucose <300 mg/dL) for up to 4 weeks, while those grown in suspension culture prior to implantation could not.102,107 The time of the in vitro culture period prior to implantation has also been shown to be important. For example, human islets precultured in hydrogels for 2 weeks were able to reverse hyperglycemia in diabetic mice, but not after a 4-week preculture period.127 In addition, transplanting PLLA/PLGA scaffolds with HUVECs and fibroblasts along with islets improved integration into the host vasculature and reduced blood glucose levels.99 Implanted pancreatic precursor cells derived from hESCs without a scaffold have been shown to reverse hyperglycemia in nude mice, but take several weeks to have an effect.28,29 Combining these cells with a scaffold may be able to shorten the maturation time needed to achieve functional implants. Overall, these findings demonstrate the positive effect of 3D preculture and transplantation of islets in a 3D scaffold on the function of these cells in vivo. The 3D scaffold technology merits further investigation and extension to pancreatic stem or precursor populations as well as testing for long-term efficacy.

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Generally, islet transplantation has been successful for short periods of time. With recent improvements to the initial Edmonton protocol and the immunosuppressive cocktail, insulin independence has increased to 5 years post-transplantation in 50% of patients.7,128 However, long-term transplanted islets still lose viability and efficacy. The techniques described within this review could further improve the clinical outcome of islet transplantation by lengthening viability of islets in vitro prior to transplantation or in vivo post-transplantation and enhancing insulin secretion. In particular, a number of studies, both in vitro and in vivo, have demonstrated that islets, β-cells, and their precursors cultured in a 3D environment and with ECM that recapitulates the native islet exhibit improved viability and enhanced GSIS. These findings strongly point toward the importance of 3D contextual presentation of cell–matrix contacts. However, preclinical testing will be required to determine whether the significant improvements in functionality observed in vitro can extend to in vivo settings and for how long. Given the lack of available donor tissues and donor islets, it is imperative to extend these approaches to the directed differentiation of stem cells toward creating insulin-producing cells. Few studies point toward the importance of replicating the dynamics of the extracellular environment during organogenesis. Further work, however, is needed to identify suitable in vitro cues that drive stem cells into insulin-producing cells and the best method for presenting these cues within functional encapsulation materials. Ultimately, β-cells derived from ESCs or iPSCs will need to supplement and even surpass cadaveric islets as cell sources capable of reversing hyperglycemia in order to treat the number of patients suffering from type 1 diabetes. Incorporating the advancements in 3D culture techniques into directed differentiation protocols and transplantation procedures has the potential to make long-term β-cell replacement a reality. While not a focus of this review, the protection of insulin-producing cells from immune attack, either by microencapsulation of individual islets or macroencapsulation of multiple islets, will also need to be addressed to limit the need for immunosuppressive drugs.129

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Beta Cell Biology Consortium and The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK089561. No competing financial interests exist.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Shaw J.E., Sicree R.A., and Zimmet P.Z.Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 87,4, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan M.J., Albanese-O'Neill A., and Haller M.J.Type 1 diabetes: current concepts in epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical care, and research. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 42,269, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler M.J.Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes 26,77, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association, A.D. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 35Suppl 1,S64, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro A., and Lakey J.Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med 343,230, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan E.A., et al. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes 54,2060, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCall M., and Shapiro A.M.Update on islet transplantation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2,a007823, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosco D., Armanet M., Morel P., and Niclauss N.Unique arrangement of α-and β-cells in human islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 59,2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera O., et al. The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103,2334, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufrane D., and Gianello P.Pig islet for xenotransplantation in human: structural and physiological compatibility for human clinical application. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 26,183, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marigliano M., Bertera S., Grupillo M., Trucco M., and Bottino R.Pig-to-nonhuman primates pancreatic islet xenotransplantation: an overview. Curr Diab Rep 11,402, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dufrane D., and Gianello P.Macro- or microencapsulation of pig islets to cure type 1 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol 18,6885, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Windt D.J., et al. Clinical islet xenotransplantation: how close are we?. Diabetes 61,3046, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernardo A.S., Hay C.W., and Docherty K.Pancreatic transcription factors and their role in the birth, life and survival of the pancreatic beta cell. Mol Cell Endocrinol 294,1, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kordowich S., Mansouri A., and Collombat P.Reprogramming into pancreatic endocrine cells based on developmental cues. Mol Cell Endocrinol 323,62, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson M.E., Scheel D., and German M.S.Gene expression cascades in pancreatic development. Mech Dev 120,65, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieck S., Bankaitis E.D., and Wright C.V.E. Lineage determinants in early endocrine development. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23,673, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumelsky N., et al. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to insulin-secreting structures similar to pancreatic islets. Science 292,1389, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Amour K.A., et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 24,1392, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basford C.L., et al. The functional and molecular characterisation of human embryonic stem cell-derived insulin-positive cells compared with adult pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 55,358, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eshpeter A., et al. In vivo characterization of transplanted human embryonic stem cell-derived pancreatic endocrine islet cells. Cell Prolif 41,843, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang J., et al. Generation of insulin-producing islet-like clusters from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 25,1940, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips B.W., et al. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into the pancreatic endocrine lineage. Stem Cells Dev 16,561, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Hoof D., Mendelsohn A.D., Seerke R., Desai T.A., and German M.S.Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into pancreatic endoderm in patterned size-controlled clusters. Stem Cell Res 6,276, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D.H., et al. Highly efficient differentiation of human ES cells and iPS cells into mature pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Cell Res 19,429, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang W., et al. In vitro derivation of functional insulin-producing cells from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Res 17,333, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nostro M.C., et al. Stage-specific signaling through TGF family members and WNT regulates patterning and pancreatic specification of human pluripotent stem cells. Development 138,1445, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroon E., et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 26,443, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz T.C., et al. A scalable system for production of functional pancreatic progenitors from human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 7,e37004, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamanaka S.Induced pluripotent stem cells: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell 10,678, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi K., et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131,861, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soejitno A., and Prayudi P.K.A.The prospect of induced pluripotent stem cells for diabetes mellitus treatment. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2,197, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunisada Y., Tsubooka-Yamazoe N., Shoji M., and Hosoya M.Small molecules induce efficient differentiation into insulin-producing cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res 8,274, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tateishi K., et al. Generation of insulin-secreting islet-like clusters from human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 283,31601, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeon K., Lim H., and Kim J.Differentiation and transplantation of functional pancreatic beta cells generated from induced pluripotent stem cells derived from a type 1 diabetes mouse model. Stem Cells Dev 21,2642, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu F.F., et al. Generation of pancreatic insulin-producing cells from rhesus monkey induced pluripotent stem cells. Diabetologia 54,2325, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye L., Swingen C., and Zhang J.Induced pluripotent stem cells and their potential for basic and clinical sciences. Curr Cardiol Rev 9,63, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uccelli A., Moretta L., and Pistoia V.Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 8,726, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milanesi A., et al. β-Cell regeneration mediated by human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One 7,e42177, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang D.-Q., et al. In vivo and in vitro characterization of insulin-producing cells obtained from murine bone marrow. Diabetes 53,1721, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L.-B., Jiang X.-B., and Yang L.Differentiation of rat marrow mesenchymal stem cells into pancreatic islet beta-cells. World J Gastroenterol 10,3016, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee R.H., et al. Multipotent stromal cells from human marrow home to and promote repair of pancreatic islets and renal glomeruli in diabetic NOD/scid mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103,17438, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang C., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells adopt beta-cell fate upon diabetic pancreatic microenvironment. Pancreas 38,275, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franquesa M., Hoogduijn M.J., Bestard O., and Grinyó J.M.Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells on B cells. Front Immunol 3,212.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hematti P., Kim J., Stein A.P., and Kaufman D.Potential role of mesenchymal stromal cells in pancreatic islet transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 27,21, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baeyens L., et al. In vitro generation of insulin-producing beta cells from adult exocrine pancreatic cells. Diabetologia 48,49, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song K.-H., et al. In vitro transdifferentiation of adult pancreatic acinar cells into insulin-expressing cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 316,1094, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minami K., and Seino S.Pancreatic acinar-to-beta cell transdifferentiation in vitro. Front Biosci 1,5824, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamada S., Yamamoto Y., and Nagasawa M.In vitro transdifferentiation of mature hepatocytes into insulin-producing cells. Endocr J 53,789, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aviv V., et al. Exendin-4 promotes liver cell proliferation and enhances the PDX-1-induced liver to pancreas transdifferentiation process. J Biol Chem 284,33509, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu Y., and Li Y.Transdifferentiation of hepatic oval cells into pancreatic islet beta-cells. Front Biosci 17,2391, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Juhl K., Bonner-Weir S., and Sharma A.Regenerating pancreatic beta-cells: plasticity of adult pancreatic cells and the feasibility of in-vivo neogenesis. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 15,79, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ulrich A.B., Schmied B.M., Standop J., Schneider M.B., and Pour P.M.Pancreatic cell lines: a review. Pancreas 24,111, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishihara H., et al. Pancreatic beta-cell line Min6 exhibits characteristics of glucose-metabolism and glucose-stimulated insulin-secretion similar to those of normal islets. Diabetologia 36,1139, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Praz G.A., et al. Regulation of immunoreactive-insulin release from a rat cell line (RINm5F). Biochem J 210,345, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asfari M., and Wollheim C.B.Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-depedent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines. Endocrinology 130,167, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duguid W.P., Maysinger D., Feldman L., Agapitos D., and Rosenberg L.Apoptosis occurs in freshly isolated human islets under standard. Transplant Proc 752,750, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saito H., Takeuchi M., Chida K., and Miyajima A.Generation of glucose-responsive functional islets with a three-dimensional structure from mouse fetal pancreatic cells and iPS cells in vitro. PLoS One 6,e28209.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samuelson L., and Gerber D.Improved function and growth of pancreatic cells in a three-dimensional bioreactor environment. Tissue Eng Part C 19,39, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka H., et al. The generation of pancreatic β-cell spheroids in a simulated microgravity culture system. Biomaterials 34,5785, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bauwens C.L., et al. Control of human embryonic stem cell colony and aggregate size heterogeneity influences differentiation trajectories. Stem Cells 26,2300, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brafman D.A., Phung C., Kumar N., and Willert K.Regulation of endodermal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells through through integrin-ECM interactions. Cell Death Differ 20,369, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernard A., Lin C., and Anseth K.A Microwell Cell Culture Platform for the Aggregation of Pancreatic β-Cells. Tissue Eng Part C 18,583, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gallego-Perez D., et al. Micro/nanoscale technologies for the development of hormone-expressing islet-like cell clusters. Biomed Microdevices 14,779, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hynes R.O.The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science 326,1216, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng J.Y.C., et al. Matrix components and scaffolds for sustained islet function. Tissue Eng Part B 17,2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stendahl J.C., Kaufman D.B., and Stupp S.I.Extracellular matrix in pancreatic islets: relevance to scaffold design and transplantation. Cell Transplant 18,1, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiang F.-X., Naselli G., and Harrison L.C.Distinct distribution of laminin and its integrin receptors in the pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem 50,1625, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nikolova G., et al. The vascular basement membrane: a niche for insulin gene expression and Beta cell proliferation. Dev Cell 10,397, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Virtanen I., et al. Blood vessels of human islets of Langerhans are surrounded by a double basement membrane. Diabetologia 51,1181, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parnaud G.Blockade of 1 integrin-laminin-5 interaction affects spreading and insulin secretion of rat-cells attached on extracellular matrix. Diabetes 55,1413, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goh S.-K., et al. Perfusion-decellularized pancreas as a natural 3D scaffold for pancreatic tissue and whole organ engineering. Biomaterials 34,6760, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deijnen J.H.M., Hulstaert C.E., Wolters G.H.J., and Schilfgaarde R.Significance of the peri-insular extracellular matrix for islet isolation from the pancreas of rat, dog, pig, and man. Cell Tissue Res 267,139, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang F.-X., and Harrison L.C.Extracellular signals and pancreatic beta-cell development: a brief review. Mol Med 8,763, 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang F.X., Georges-Labouesse E., and Harrison L.C.Regulation of laminin 1-induced pancreatic beta-cell differentiation by alpha6 integrin and alpha-dystroglycan. Mol Med 7,107, 2001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiang F.X., Cram D.S., DeAizpurua H.J., and Harrison L.C.Laminin-1 promotes differentiation of fetal mouse pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 48,722, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pinkse G.G.M., et al. Integrin signaling via RGD peptides and anti-1 antibodies confers resistance to apoptosis in islets of langerhans. Diabetes 55,1, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ris F., et al. Impact of integrin-matrix matching and inhibition of apoptosis on the survival of purified human beta-cells in vitro. Diabetologia 45,841, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hammar E., et al. Extracellular matrix protects pancreatic beta-cells against apoptosis. Diabetes 53,2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Banerjee M., Virtanen I., Palgi J., Korsgren O., and Otonkoski T.Proliferation and plasticity of human beta cells on physiologically occurring laminin isoforms. Mol Cell Endocrinol 355,78, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaido T.J., et al. Impact of integrin-matrix interaction and signaling on insulin gene expression and the mesenchymal transition of human beta-cells. J Cell Physiol 224,101, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kaido T., et al. Impact of defined matrix interactions on insulin production by cultured human beta-cells: effect on insulin content, secretion, and gene transcription. Diabetes 55,2723, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Daoud J., Petropavlovskaia M., Rosenberg L., and Tabrizian M.The effect of extracellular matrix components on the preservation of human islet function in vitro. Biomaterials 31,1676, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perfetti R., Henderson T.E., Wang Y., Montrose-Rafizadeh C., and Egan J.M.Insulin release and insulin mRNA levels in rat islets of Langerhans cultured on extracellular matrix. Pancreas 13,47, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van Deijnen J.H.M., Van Snylichem P.T.R., Wolters, G.H.J., and Van Schilfgaarde, R. Cell & tissue distribution of collagens type I, type III and type V in the pancreas of rat, dog, pig and man. Cell Tissue Res 277,115, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hughes S.J., et al. Characterisation of collagen VI within the islet-exocrine interface of the human pancreas: implications for clinical islet isolation? Transplantation 81,423, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cirulli V., et al. Expression and function of alpha(v)beta(3) and alpha(v)beta(5) integrins in the developing pancreas: roles in the adhesion and migration of putative endocrine progenitor cells. J Cell Biol 150,1445, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaido T., Yebra M., Cirulli V., and Montgomery A.M.Regulation of human beta-cell adhesion, motility, and insulin secretion by collagen IV and its receptor alpha1beta1. J Biol Chem 279,53762, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lucas-Clerc C., Massart C., Campion J.P., Launois B., and Nicol M.Long-term culture of human pancreatic islets in an extracellular matrix: morphological and metabolic effects. Mol Cell Endocrinol 94,9, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Navarro-Alvarez N.Reestablishment of microenvironment is necessary to maintain in vitro and in vivo human islet function. Cell Transplant 17,111, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cheng J.Y.C., Whitelock J., and Poole-Warren L.Syndecan-4 is associated with beta-cells in the pancreas and the MIN6 beta-cell line. Histochem Cell Biol 138,933, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tkachenko E., Lutgens E., Stan R.-V., and Simons M.Fibroblast growth factor 2 endocytosis in endothelial cells proceed via syndecan-4-dependent activation of Rac1 and a Cdc42-dependent macropinocytic pathway. J Cell Sci 117,3189, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ziolkowski A., and Popp S.Heparan sulfate and heparanase play key roles in mouse β cell survival and autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Investig 122,2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Irving-Rodgers H., and Choong F.Pancreatic islet basement membrane loss and remodeling after mouse islet isolation and transplantation: impact for allograft. Cell Transplant 23,59, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Page H., Flood P., and Reynaud E.G.Three-dimensional tissue cultures: current trends and beyond. Cell Tissue Res 352,123, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chun S., et al. Adhesive growth of pancreatic islet cells on a polyglycolic acid fibrous scaffold. Transplant Proc 40,1658, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Daoud J.T., et al. Long-term in vitro human pancreatic islet culture using three-dimensional microfabricated scaffolds. Biomaterials 32,1536, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kawazoe N., and Tateishi T.Three-dimensional cultures of rat pancreatic RIN-5F cells in porous PLGA-collagen hybrid scaffolds. J Bioact Compat Polym 24,25, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kaufman-Francis K., Koffler J., Weinberg N., Dor Y., and Levenberg S.Engineered vascular beds provide key signals to pancreatic hormone-producing cells. PLoS One 7,e40741, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nicodemus G.D., and Bryant S.J.Cell encapsulation in biodegradable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 14,149, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zimmermann H., Shirley S.G., and Zimmermann U.Alginate-based encapsulation of cells: past, present, and future. Curr Diab Rep 7,314, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee B.R., et al. In situ formation and collagen-alginate composite encapsulation of pancreatic islet spheroids. Biomaterials 33,837, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cui Y.X., Shakesheff K.M., and Adams G.Encapsulation of RIN-m5F cells within Ba2+ cross-linked alginate beads affects proliferation and insulin secretion. J Microencapsul 23,663, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hall K.K., Gattas-Asfura K.M., and Stabler C.L.Microencapsulation of islets within alginate/poly(ethylene glycol) gels cross-linked via Staudinger ligation. Acta Biomater 7,614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lim D., and Antipenko S.Enhanced rat islet function and survival in vitro using a biomimetic self-assembled nanomatrix gel. Tissue Eng Part A 17,399, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhao M., et al. The three-dimensional nanofiber scaffold culture condition improves viability and function of islets. J Biomed Mater Res A 94,667, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liao S.W., et al. Maintaining functional islets through encapsulation in an injectable saccharide-peptide hydrogel. Biomaterials 34,3984, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Davis N.E., et al. Enhanced function of pancreatic islets co-encapsulated with ECM proteins and mesenchymal stromal cells in a silk hydrogel. Biomaterials 33,6691, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang X., and Ye K.Three-dimensional differentiation of embryonic stem cells into islet-like insulin-producing clusters. Tissue Eng Part A 15,1941, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weber L.M., and Anseth K.S.Hydrogel encapsulation environments functionalized with extracellular matrix interactions increase islet insulin secretion. Matrix Biol 27,667, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Weber L.M., Hayda K.N., Haskins K., and Anseth K.S.The effects of cell-matrix interactions on encapsulated beta-cell function within hydrogels functionalized with matrix-derived adhesive peptides. Biomaterials 28,3004, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tashiro K., et al. An IKLLI-containing peptide derived from the laminin alpha1 chain mediating heparin-binding, cell adhesion, neurite outgrowth and proliferation, represents a binding site for integrin alpha3beta1 and heparan sulphate proteoglycan. Biochem J 126,119, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nomizu M., Weeks B.S., Weston C.A., and Hoo W.Structure-activity study of a laminin alpha 1 chain active peptide segment Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (IKVAV). FEBS Lett 365,227, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mason M.N., and Mahoney M.J.Selective beta-cell differentiation of dissociated embryonic pancreatic precursor cells cultured in synthetic polyethylene glycol hydrogels. Tissue Eng Part A 15,1343, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mason M.N., Arnold C.A., and Mahoney M.J.Entrapped collagen type 1 promotes differentiation of embryonic pancreatic precursor cells into glucose-responsive beta-cells when cultured in three-dimensional PEG hydrogels. Tissue Eng Part A 15,3799, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mason M.N., and Mahoney M.J.Inhibition of gamma-secretase activity promotes differentiation of embryonic pancreatic precursor cells into functional islet-like clusters in poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel culture. Tissue Eng Part A 16,2593, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lin C., and Anseth K.Glucagon-like peptide-1 functionalized PEG hydrogels promote survival and function of encapsulated pancreatic β-cells. Biomacromolecules 10,2460, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Su J., Hu B.-H., Lowe W.L., Kaufman D.B., and Messersmith P.B.Anti-inflammatory peptide-functionalized hydrogels for insulin-secreting cell encapsulation. Biomaterials 31,308, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lin C.-C., Raza A., and Shih H.PEG hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photo-click chemistry and their effect on the formation and recovery of insulin-secreting cell spheroids. Biomaterials 32,9685, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]