Abstract

The clostridial neurotoxin (CNT) family includes botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), serotypes A, B, E, and F of which can cause human botulism, and tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT), which is the causative agent of tetanus. This suggests that the greatest need is for a multivalent or multiagent vaccine that provides protection against all 5 agents. In this study, we investigated the feasibility of generating several pentavalent replicon vaccines that protected mice against BoNTs and TeNT. First, we evaluated the potency of individual replicon DNA or particle vaccine against TeNT, which induced strong antibody and protective responses in BALB/c mice following 2 or 3 immunizations. Then, the individual replicon TeNT vaccines were combined with tetravalent BoNTs vaccines to prepare 4 types of pentavalent replicon vaccines. These replicon DNA or particle pentavalent vaccines could simultaneously and effectively induce antibody responses and protect effects against the 5 agents. Finally, a solid-phase assay showed that the sera of pentavalent replicon formulations-immunized mice inhibited the binding of THc to the ganglioside GT1b as the sera of individual replicon DNA or particle-immunized mice. These results indicated these pentavalent replicon vaccines could protect against the 4 BoNT serotypes and effectively neutralize and protect the TeNT. Therefore, our studies demonstrate the utility of combining replicon DNA or particle vaccines into multi-agent formulations as potent pentavalent vaccines for eliciting protective responses against BoNTs and TeNT.

Keywords: botulinum neurotoxin, tetanus neurotoxin, multivalent vaccine, replicon vector, immunogenicity

Introduction

The botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the most toxic proteins and can be classed into 7 serotypes (A–G) produced by bacteria of the genus Clostridium. Botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A, B, E, and F can cause disease in human, as opposite to serotypes C and D that can cause disease in cattle and horses.1-4 Tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) also is very toxic and the estimated human lethal dose is less than 2.5 ng per kg.1,2 Together with TeNT produced by Clostridium tetani, the BoNTs make up the clostridial neurotoxin (CNT) family. CNTs are synthesized as single-chain polypeptides of ~150 kDa composed of 3 domains, each of approximately 50 kDa, e.g., the N-terminal catalytic domain (light chain), the internal heavy chain translocation domain (Hn domain), and the C-terminal heavy chain receptor-binding domain (Hc domain).

Botulism or tetanus can be effectively prevented by the presence of neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccination. The formalin-inactivated toxoid vaccines commonly used in human are protective against BoNTs or TeNT. However, they have met with some drawbacks, including feasibility, dangers associated with handling neurotoxins, and secondary complications due to residual formaldehyde contamination.5-8 Additionally, these toxoid vaccine preparations are only partially pure and occasionally give rise to adverse reactions on hyper-immunization. Therefore, the improved vaccines designed to overcome above disadvantages are needed. A novel vaccine strategy for the prevention of botulism or tetanus based on the production of nontoxic recombinant Hc proteins has been developed.6-8 The Hc domains of BoNTs or TeNT produced in Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris were shown to elicit protective immune responses in mice and other animals.9-15 DNA or viral replicon vaccines encoding the same Hc antigens were described as the next generation of candidate vaccines.16-21 Recently, we developed individual and multivalent candidate replicon vaccines against BoNTs using DNA-based Semliki Forest virus (SFV) replicon vectors.22-24 In this current study, we further developed several pentavalent replicon vaccines for BoNTs (serotypes A, B, E, and F) and TeNT using the DNA-based SFV replicon vectors, and evaluated their immunogenicity and protective capability against challenge with the BoNTs and TeNT mixture in mice.

Results

Individual replicon vaccine for TeNT

The immunogenicity and protective ability of replicon DNA or VRP vaccine against TeNT were investigated and compared with the pVAX1STHc encoding the THc antigen. As shown in Table 1, these vaccines induced strong ELISA and neutralizing antibody responses in BALB/c mice following 3 immunizations. Mice immunized 3 times with pSCARSTHc, VRP-THc, or pVAX1STHc were completely protected against 1000 or 10 000 mouse LD50 of biologically active TeNT, and 2 injections with low antibody responses provided partial protection against 1000 LD50 of TeNT, while the negative control mice succumbed to intoxication and died within 12 h as the native mice.

Table 1. Sera antibody titers, neutralization titers, and survival of mice following vaccination with pSCARSTHC, pVAX1STHC, or RVP-THC.

| Vaccine | Vaccination route | Log10 GMT(SD)a | Neutralization titerb | Number alivec | Number alived | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2e | 3e | 2e | 3e | 2e | 3e | 3e | ||

| pSCARSTHc | i.m. | 3.80(0.16) | 4.59 (0.28)* | <0.125 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 |

| pVAX1STHc | i.m. | 3.80(0.16) | 4.25 (0.28) | <0.125 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| RVP-THc | s.c. | 3.65(0.23) | 4.33 (0.14) | <0.125 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

a Sera obtained a week before challenge from individual mice was assayed and used to calculate the log10 GMT for each group. Standard deviations (SD) of GMT are in parenthesis. Antibody titers to THc are shown in the table. *(P < 0.05) indicate significant anti-THc antibody titer difference between pSCARSTHC- and pVAX1STHC-vaccination groups with 3 injections; bPooled sera from each group of mice were diluted initially 1:32 (500 µL) and then 2-fold for serum neutralization titers. Due to the limited amount of serum available, serum from each group of mice was pooled, and so only the average neutralization titer (IU/mL) of the group against TeNT could be assayed; cBALB/c mice alive (8 mice/group) after s.c. challenge with a dose 1000 LD50 of TeNT 4 wk after the last injection; dBALB/c mice alive (8 mice/group) after s.c. challenge with a dose 10 000 LD50 of TeNT 4 wk after the last injection; eNumber of vaccinations.

To further define the protective potencies of these replicon vaccines, we rechallenged the mice of 3 vaccination 1 wk later with a higher TeNT doses (100 000 LD50) and observed no mice deaths in the pSCARSTHc or VRP-THc-immunized group. However, the pVAX1STHc vaccine provided no protection. Notably, the mean ELISA and neutralizing antibody titers in the 3 doses of pSCARSTHc or VRP-THc-immunized group were higher than that of pVAX1STHc-immunized group (P < 0.05). Protective effects correlated directly with the ELISA and neutralizing antibody titers to TeNT. Therefore, these results indicated that the replicon DNA or VRP encoding the THc antigen is an effective vaccine against TeNT.

Pentavalent plasmid replicon DNA vaccines for BoNTs and TeNT

Then, the individual replicon DNA TeNT vaccines were combined with tetravalent vaccines against BoNTs24 to prepare pentavalent replicon DNA vaccines against BoNTs and TeNT. We evaluated 2 types of pentavalent replicon DNA vaccine candidates: pentavalent DNA-I (pSCARSAHc + pSCARSBHc + pSCARSEHc + pSCARSFHc + pSCARSTHc) and pentavalent DNA-II (pSCARSA/BHc + pSCARSE/FHc + pSCARSTHc). As shown in Table 2, the 2 types of pentavalent replicon DNA vaccines induced high ELISA IgG antibody titers to each Hc and efficacious neutralizing antibody levels against TeNT in mice. And these vaccinations provided nearly complete protective effects against challenge with 100 or 1000 LD50 of BoNTs (serotypes A, B, E, and F) and TeNT mixtures (Table 2).

Table 2. Sera antibody titers, neutralization titers, and survival of mice following 3 vaccinations i.m. with pentavalent replicon DNA vaccines against BoNTs and TeNT.

| Vaccine | Log10 GMT(SD)a | Neutralization titerb | Number alivec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHc | BHc | EHc | FHc | THc | TeNT | 102 | 103 | |

| pSCARSAHc + pSCARSBHc + pSCARSEHc + pSCARSFHc + pSCARSTHc | 3.73 (0.14) |

3.64 (0.27) |

3.97 (0.24) |

3.88 (0.14) |

4.14 (0.25) |

0.5 | 8 | 8 |

| pSCARSA/BHc+ pSCARSE/FHc+ pSCARSTHc |

3.58 (0.27) |

3.61 (0.53) |

3.90 (0.16) |

3.95 (0.28) |

4.10 (0.23) |

0.5 | 8 | 7 |

a Sera antibody titers (the log10 GMT for each group) to AHc, BHc, EHc, FHc, or THc were shown in table, respectively. The respective standard deviations (SD) of the GMT are in parenthesis; bSera neutralization titers (IU/mL) against TeNT were shown in table, respectively; c Mice alive (8 mice/group) after s.c. challenge with the indicated dose of BoNTs(serotypes A, B, E, and F) and TeNT mixture (102 or 103 LD50, each) 4 wk after the last injection.

Pentavalent replicon RVP vaccines for BoNTs and TeNT

Further, another 2 types of pentavalent replicon VRP vaccines were developed and the protective capability was evaluated against challenge with mixture of BoNTs and TeNT in mice. Immunization with the pentavalent RVP-I (VRP-AHc + VRP-BHc + VRP-EHc + VRP-FHc + VRP-THc) or pentavalent RVP-II (VRP-A/BHc + VRP-E/FHc+ VRP-THc) vaccine formulation also induced showed high ELISA IgG antibody titers to each Hc and sufficient neutralizing antibody levels against TeNT in mice (Table 3). Vaccination with the 2 types of pentavalent replicon VRP vaccines provided completely protection against a dose of 100 LD50 of BoNTs (serotypes A, B, E and F) and TeNT mixture challenge and mostly protective effects against challenge with a mixture of 1000 LD50 of each BoNTs and TeNT (Table 3).

Table 3. Sera antibody titers, neutralization titers, and survival of mice following 3 vaccinations s.c. with pentavalent replicon RVP vaccines against BoNTs and TeNT.

| Vaccine | Log10 GMT(SD)a | Neutralization titerb | Number alivec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHc | BHc | EHc | FHc | THc | TeNT | 102 | 103 | |

| RVP-AHc+RVP-BHc + RVP-EHc+RVP-FHc + RVP-THc |

3.65 (0.27) |

3.72 (0.28) |

3.88 (0.14) |

3.94 (0.48) |

4.29 (0.16) |

1.0 | 8 | 6 |

| RVP-A/BHc + RVP-E/FHc + RVP-THc |

3.62 (0.23) |

3.64 (0.27) |

3.78 (0.52) |

3.71 (0.61) |

4.10 (0.32) |

0.5 | 8 | 6 |

a Sera antibody titers (the log10 GMT for each group) to AHc, BHc, EHc, FHc, or THc were shown in table, respectively. The respective standard deviations (SD) of the GMT are in parenthesis; bSera neutralization titers (IU/mL) against TeNT were shown in table, respectively; cMice alive (8 mice/group) after s.c. challenge with the indicated dose of BoNTs(serotypes A, B, E, and F) and TeNT mixture (102 or 103 LD50, each) 4 wk after the last injection.

Also, mice were immunized with tetravalent BoNT vaccines24 or individual replicon TeNT vaccines as control groups. The immunized mice succumbed to intoxication and died within 24 h with the mixtures of BoNTs and TeNT challenge. Our results indicated that immunization with these different pentavalent replicon vaccines induced similar antibody responses that produced almost equal protective effects against the challenge with mixture of BoNTs and TeNT.

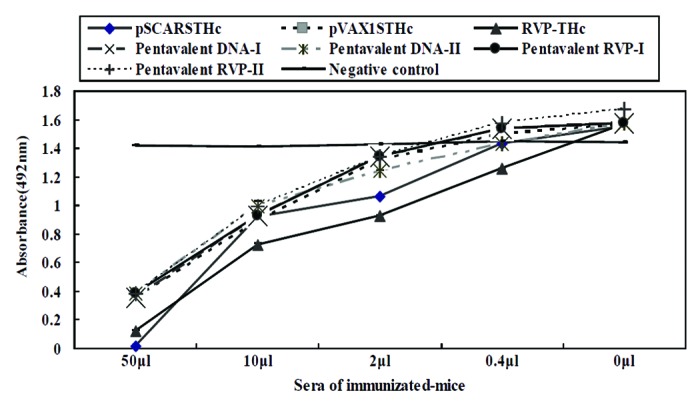

Immune sera antibodies blocked THc binding to ganglioside

Previously, ganglioside (GT1b) binding assays indicated recognition of ganglioside by the recombinant THc protein as good as the biological active TeNT, and the sera of THc-immunzied mice could effectively inhibit the binding THc or TeNT to ganglioside.15 To further explore the molecular basis for the neutralizing capacity of these THc-expressing replicon immunizations, a solid-phase assay was performed, which allowed the assessment of the ability of sera antibodies to inhibit the binding of THc to GT1b. The sera of the negative control group or pre-immune mice did not interfere with the binding of THc to GT1b, while the sera of pentavalent replicon DNA or RVP-immunized mice produced dose-dependent inhibition of the binding of THc to GT1b as the sera of individual replicon DNA or RVP-immunized mice (Fig. 1). This indicates that these immune sera antibodies neutralize or inhibit the binding of TeNT to ganglioside, which is the first step in TeNT intoxication of neurons.

Figure 1. Immune sera antibodies blocked THc binding to ganglioside. The sera from mice immunized with individual (pSCARSTHc and RVP-THc) or pentavalent replicon (Pentavalent DNA- I, Pentavalent DNA- II, Pentavalent RVP- I, and Pentavalent RVP- II) vaccines were used to block THc binding to GT1b. Sera from pVAX1STHc-immunized mice were used as parallel control. Values represent means from 2–4 separate experiments with bars representing standard mean of deviations.

Discussion

The clostridial neurotoxin family includes botulinum neurotoxins, serotypes A, B, E, and F of which can cause human botulism, and tetanus neurotoxin, which is the causative agent of tetanus. The mouse LD50 values of BoNTs and TeNT are between 0.1 and 1 ng neurotoxin per kg.1,2 This suggests that the greatest need is for a multivalent or multiagent vaccine that provides protection against all 5 agents. This also promoted the current study to produce pentavalent vaccines to neutralize the botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins and prevent intoxication.

First, the replicon DNA vaccine pSCARSTHc induced strong antibody and protective responses against TeNT in BALB/c mice following 2 or 3 immunizations as previously described by using the replicon DNA vaccines against BoNTs.22-24 And, our results demonstrated that the VRP vaccine VRP-THc as an alternative vaccine format was capable of eliciting efficient protective potency against TeNT, just as candidate VEE virus or SFV replicon vaccines against BoNTs.20,21 Then, the individual replicon TeNT vaccines were combined with tetravalent BoNT vaccines24 to prepare 4 types of pentavalent replicon vaccines against botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins. Mice immunized with the 4 types of pentavalent replicon vaccines all simultaneously produced strong antibody responses and were resistant to the challenge with mixtures of BoNTs (serotypes A, B, E, and F) and TeNT as multivalent subunit vaccines against BoNTs,12,13 bivalent vaccine based on VEE virus replicon against Lassa and Ebola viruses,25 or multiagent vaccine against Marburg virus, anthrax toxin, and BoNT/C.21 As shown in our results, protective potency against TeNT correlates well with anti-THc and TeNT neutralizing antibody levels, which is consistent with the concept that sera antibodies play a key role in protective potency against toxin. Moreover, the sera of different pentavalent replicon formulations-immunized mice strongly blocked THc binding to the ganglioside as the sera of individual replicon DNA or particle-immunized mice. Notably, no different efficacy against botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins was observed in DNA and VRP vaccination methodologies in this study, which further indicated that the viral replicon vectors as pentavalent vaccines were feasible and effective.

Currently, there also is a demand for the development of safe and effective multivalent vaccines, which can simultaneously provide efficient protection against several important pathogens.26 An effective multivalent or multiagent vaccine must simultaneously provide protection against all the agents. Our findings revealed that the 4 types of pentavalent replicon vaccines simultaneously produced high IgG titers to each antigen and protect against the all 5 agents. And vaccination with different pentavalent replicon vaccines produced similar antibody responses that conferred almost equal protective effects against the challenge with mixtures of BoNTs and TeNT. As far as we know, this is the first report of multivalent DNA or RVP vaccines eliciting protective immune responses to BoNTs and TeNT. We have made extensive efforts on preparation of individual or multivalent replicon vaccines against the BoNTs,22-24 anthrax,27,28 and TeNT. These data provided a basis for further developing multivalent or multiagent vaccines against multiple important pathogens such as BoNTs, TeNT or B. anthracis. Several multiagent replicon vaccines against neurotoxin, B. anthracis and/or virus are being assessed in our laboratory. Thus, we have described an efficient strategy to design and develop multivalent vaccines against multi-agent pathogens using DNA-based SFV replicon vectors.

In summary, our findings have shown that low doses of naked multivalent replicon vaccines without gene gun or electroporation can induce strong immune responses and protective effects against each agent, which indicates this type of multivalent replicon vaccine may be desirable for use in future clinical application. Future studies in nonhuman primates with gene gun or electroporation are underway to assess and better define their utility and help to translate these multivalent replicon vaccines to human clinical trials with an advanced DNA delivery system.

Materials and Methods

Construction of DNA replicon vaccines

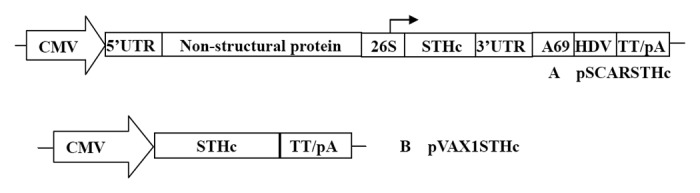

Four plasmid DNA replicon vaccines (pSCARSAHc, pSCARSBHc, pSCARSEHc, and pSCARSFHc) encoding the Hc domains of BoNT/A, B, E, and F, respectively, were constructed and developed in previous studies.22-24 Two dual-expression plasmid DNA replicon vaccine (pSCARSA/BHc and pSCARSE/FHc) were also constructed and developed in previous studies.23,24 In this study, we constructed an additional plasmid DNA replicon vaccine pSCARSTHc and conventional DNA vaccine pVAX1STHc. Briefly, the AHc of pSCARSAHc was replaced with THc (one synthetic gene encoding the C-terminal heavy chain receptor-binding domain of TeNT)15 by using the Nde I and SmaI cloning sites, resulting in pSCARSTHc (Fig. 2A) as described previously.24 To generate a corresponding conventional DNA vaccines encoding the THc, the DNA fragments were isolated by digesting pSCARSTHc with BamH I and Spe I, and then inserting them into the vector pVAX1 to create pVAX1STHc (Fig. 2B). All plasmids were prepared and purified using Endofree Mega-Q kits (QIAGEN GmbH) for transfection and immunization. BHK-21 cells were transfected with pSCARSTHc or pVAX1SFHc, and the expression of THc was analyzed by as described previously.22

Figure 2. Schematic diagrams of plasmids used for DNA vaccination in this study. The individual transcriptional control elements comprising the DNA-based replicon vaccine plasmids based on SFV replicon (pSCARSTHc) and the conventional DNA vaccine plasmid (pVAX1STHc) are indicated. CMV, cytomegalovirus immediate early (CMV IE) enhancer/promoter. TT/pA, BGH transcription termination and polyadenylation signal. HDV, HDV antigenomic ribozyme sequence. 26S, the subgenomic promoter of SFV. S, Ig κ leader sequence. THc, a completely synthetic genes encoding the Hc domains of TeNT.

Preparation of DNA-based recombinant SFV replicon particles

Recombinant SFV replicon particles (VRP) were prepared as described previously.23 Briefly, BHK-21 cells were co-transfected with DNA-based replicon expression vectors and helper vector (pSHCAR), and the VRP were harvested at 24 to 36 h after co-transfection. VRP were concentrated and purified by centrifugation, and the virus pellets were resuspended in PBS buffer. For titer detection, BHK-21 cells were infected with serial dilutions of activated virus and monitored for expression of antigen by X-gal staining (VRP-lacZ) or immunofluorescence assay (e.g., VRP-THc) as described previously.23

Vaccination and challenge of mice

Female BALB/c mice (aged 6–7 wk) were obtained from the Beijing Laboratory Animal Center (Beijing, China) and were kept under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Dosage used in the immunized groups was optimized by a series of preliminary experiments. For DNA vaccination, groups of 8 mice were injected intramuscularly (i.m.) twice or three times with 3-wk intervals with either a single DNA or with a mixture of DNAs at a dose of 10 μg of each DNA in a total volume of 0.1 mL. For VRP vaccination, groups of 8 mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) twice or three times with 3-wk intervals with either a single VRP or with a mixture of VRPs at a dose of 106 IU of each VRP in a total volume of 0.2 mL. As a negative control, mice were vaccinated with pSCAR, pVAX1 or VRP-lacZ as above. Mice from all groups were challenged s.c. with different dosages of pure TeNT15 or BoNTs and TeNT mixture 4 wk after the last vaccination. The mice were observed for 1 wk and survival was determined for each vaccination group. The animal protocols in this study were approved by Institution Animal Care and Use Committee of our Institution.

Antibody titer measurements

Sera from mice in different treatment groups were screened for anti-THc, AHc, BHc, EHc, or FHc antibodies by ELISA as described previously.15,24 Briefly, the total IgG titers were determined using HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies. Antibody ELISA titers represent the highest dilution of samples showing a 2-fold OD492 value over controls. Sera obtained 1 wk before challenge from individual mouse were assayed and their geometric mean titers (GMT) were used to calculate the log10 GMT for each group. Standard deviations (SD) of the GMT are in parenthesis.

TeNT neutralization assay (TN assay)

The in vivo TN assay was performed as described previously.15 Briefly, mixtures of serial dilutions of mice pooled sera with a standard concentration of TeNT were incubated 1 h at room temperature and the mixtures were injected subcutaneously into BALB/c mice (18–22 g) using a volume of 500 μl /mouse (4 mice in each group). The mice were observed for one week, and death or not was recorded. The concentration of neutralizing antibody in the serum was calculated relative to a World Health Organization TeNT antitoxin and neutralizing antibody titers of serum were reported as international units per milliliter (IU/mL).

Ganglioside binding assays

To observe the ability of anti-THc antibody to block THc binding to ganglioside GT1b, ganglioside binding assays were performed following the procedure described previously by modified method.15 Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 100 µL of 10 µg/mL bovine ganglioside GT1b (Sigma) per well and blocked with PBS containing 3% nonfat dry milk at 37 °C for 2 h. Simultaneously, THc (2 µg/well, 20 µg/mL) had been pre-incubated for 1h at 37 °C with sera from mice immunized with the different vaccines range from 50 µL to 0.4 µL/well. After incubation, the wells were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) and then 100 µL of these mixtures were added to different wells for 2 h to continue performing ganglioside binding assays. 1:5000 dilutions of polyclonal mouse anti-THc antibodies were used as primary antibody for the experiment. Sera from mice in the negative control groups (or pre-immune mouse) were used as negative controls.

Statistical analysis

Differences in antibody titers were analyzed statistically using the Student t test between group differences. The Fisher exact test was used to determine statistical differences in survival between the treatment groups. For all tests only data resulting in P values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Turton K, Chaddock JA, Acharya KR. Botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins: structure, function and therapeutic utility. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:552–8. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiavo G, Matteoli M, Montecucco C. Neurotoxins affecting neuroexocytosis. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:717–66. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dembek ZF, Smith LA, Rusnak JM. Botulism: cause, effects, diagnosis, clinical and laboratory identification, and treatment modalities. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1:122–34. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318158c5fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, et al. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 2001;285:1059–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne MP, Smith LA. Development of vaccines for prevention of botulism. Biochimie. 2000;82:955–66. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Middlebrook JL. Production of vaccines against leading biowarfare toxins can utilize DNA scientific technology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1415–23. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith LA, Rusnak JM. Botulinum neurotoxin vaccines: past, present, and future. Crit Rev Immunol. 2007;27:303–18. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v27.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith LA. Botulism and vaccines for its prevention. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 4):D33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairweather NF, Lyness VA, Maskell DJ. Immunization of mice against tetanus with fragments of tetanus toxin synthesized in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2541–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2541-2545.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton MA, Clayton JM, Brown DR, Middlebrook JL. Protective vaccination with a recombinant fragment of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A expressed from a synthetic gene in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2738–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2738-2742.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith LA. Development of recombinant vaccines for botulinum neurotoxin. Toxicon. 1998;36:1539–48. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(98)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravichandran E, Al-Saleem FH, Ancharski DM, Elias MD, Singh AK, Shamim M, Gong Y, Simpson LL. Trivalent vaccine against botulinum toxin serotypes A, B, and E that can be administered by the mucosal route. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3043–54. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01893-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldwin MR, Tepp WH, Przedpelski A, Pier CL, Bradshaw M, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. Subunit vaccine against the seven serotypes of botulism. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1314–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01025-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu YZ, Li N, Zhu HQ, Wang RL, Du Y, Wang S, Yu WY, Sun ZW. The recombinant Hc subunit of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A is an effective botulism vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2009;27:2816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu YZ, Gong ZW, Ma Y, Zhang SM, Zhu HQ, Wang WB, Du Y, Wang S, Yu WY, Sun ZW. Co-expression of tetanus toxin fragment C in Escherichia coli with thioredoxin and its evaluation as an effective subunit vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2011;29:5978–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clayton J, Middlebrook JL. Vaccination of mice with DNA encoding a large fragment of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Vaccine. 2000;18:1855–62. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stratford R, Douce G, Zhang-Barber L, Fairweather N, Eskola J, Dougan G. Influence of codon usage on the immunogenicity of a DNA vaccine against tetanus. Vaccine. 2000;19:810–5. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stratford R, Douce G, Bowe F, Dougan G. A vaccination strategy incorporating DNA priming and mucosal boosting using tetanus toxin fragment C (TetC) Vaccine. 2001;20:516–25. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett AM, Perkins SD, Holley JL. DNA vaccination protects against botulinum neurotoxin type F. Vaccine. 2003;21:3110–7. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JS, Pushko P, Parker MD, Dertzbaugh MT, Smith LA, Smith JF. Candidate vaccine against botulinum neurotoxin serotype A derived from a Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vector system. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5709–15. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5709-5715.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JS, Groebner JL, Hadjipanayis AG, Negley DL, Schmaljohn AL, Welkos SL, Smith LA, Smith JF. Multiagent vaccines vectored by Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon elicits immune responses to Marburg virus and protection against anthrax and botulinum neurotoxin in mice. Vaccine. 2006;24:6886–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu YZ, Zhang SM, Sun ZW, Wang S, Yu WY. Enhanced immune responses using plasmid DNA replicon vaccine encoding the Hc domain of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Vaccine. 2007;25:8843–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Y, Yu J, Li N, Wang S, Yu W, Sun Z. Individual and bivalent vaccines against botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A and B using DNA-based Semliki Forest virus vectors. Vaccine. 2009;27:6148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu YZ, Guo JP, An HJ, Zhang SM, Wang S, Yu WY, Sun ZW. Potent tetravalent replicon vaccines against botulinum neurotoxins using DNA-based Semliki Forest virus replicon vectors. Vaccine. 2013;31:2427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pushko P, Geisbert J, Parker M, Jahrling P, Smith J. Individual and bivalent vaccines based on alphavirus replicons protect guinea pigs against infection with Lassa and Ebola viruses. J Virol. 2001;75:11677–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11677-11685.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merkel TJ, Perera PY, Kelly VK, Verma A, Llewellyn ZN, Waldmann TA, Mosca JD, Perera LP. Development of a highly efficacious vaccinia-based dual vaccine against smallpox and anthrax, two important bioterror entities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18091–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013083107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu YZ, Li N, Wang WB, Wang S, Ma Y, Yu WY, Sun ZW. Distinct immune responses of recombinant plasmid DNA replicon vaccines expressing two types of antigens with or without signal sequences. Vaccine. 2010;28:7529–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu YZ, Li N, Ma Y, Wang S, Yu WY, Sun ZW. Three types of human CpG motifs differentially modulate and augment immunogenicity of nonviral and viral replicon DNA vaccines as built-in adjuvants. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:228–39. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]