Abstract

Immunogenicity and safety of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine were evaluated in healthy Chinese females aged 9–45 years in 2 phase IIIB, randomized, controlled trials. Girls aged 9–17 years (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00996125) received vaccine (n = 374) or control (n = 376) and women aged 26–45 years (NCT01277042) received vaccine (n = 606) or control (n = 606) at months 0, 1, and 6. The primary objective was to show non-inferiority of anti-HPV-16 and -18 immune responses in initially seronegative subjects at month 7, compared with Chinese women aged 18–25 years enrolled in a separate phase II/III trial (NCT00779766). Secondary objectives were to describe the anti-HPV-16 and -18 immune response, reactogenicity and safety. At month 7, immune responses were non-inferior for girls (9–17 years) vs. young women (18–25 years): the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio (women/girls) was below the limit of 2 for both anti-HPV-16 (0.37 [95% CI: 0.32, 0.43]) and anti-HPV-18 (0.42 [0.36, 0.49]). Immune responses at month 7 were also non-inferior for 26–45 year-old women vs. 18–25 year-old women: the upper limit of the 95% CI for the difference in seroconversion (18–25 minus 26–45) was below the limit of 5% for both anti-HPV-16 (0.00% [–1.53, 1.10]) and anti-HPV-18 (0.21% [–1.36, 1.68]). GMTs were 2- to 3-fold higher in girls (9–17 years) as compared with young women (18–25 years). The HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine had an acceptable safety profile when administered to healthy Chinese females aged 9–45 years.

Keywords: China, HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine, cervical cancer, female, human papillomavirus, immunogenicity, safety

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a major public health concern in China. The most recent findings from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, via GLOBOCAN 2012, estimated 61 691 new cases and 29 526 women dying from the disease annually in China.1 The actual burden of disease may be even higher, as the GLOBOCAN estimate is based on relatively few registry sites, in areas with higher than average socioeconomic status.2 Using available epidemiological evidence from both urban and rural areas in mainland China it was estimated that the annual number of new cervical cancer cases nationally, in the absence of any intervention, ranged from 27 000–130 000 in 2010 and could increase by approximately 40–50% by 2050.2

Persistent infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) is associated with the subsequent development of cervical cancer.3,4 Prophylactic vaccination offers the potential to substantially reduce the burden of disease, and may be particularly beneficial in China, where the implementation of effective universal screening programmes is hindered by the lack of infrastructure. Two prophylactic vaccines have been developed based on the L1 proteins of oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18, the genotypes most commonly associated with cervical cancer in China and worldwide.5-7 The HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine (Cervarix®, GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) is currently registered in more than 130 markets globally and is undergoing regulatory evaluation in China. In an ongoing randomized, controlled, phase II/III trial, this vaccine was shown to be efficacious, immunogenic and to have a clinically acceptable safety profile in more than 6000 Chinese women aged 18–25 y.8

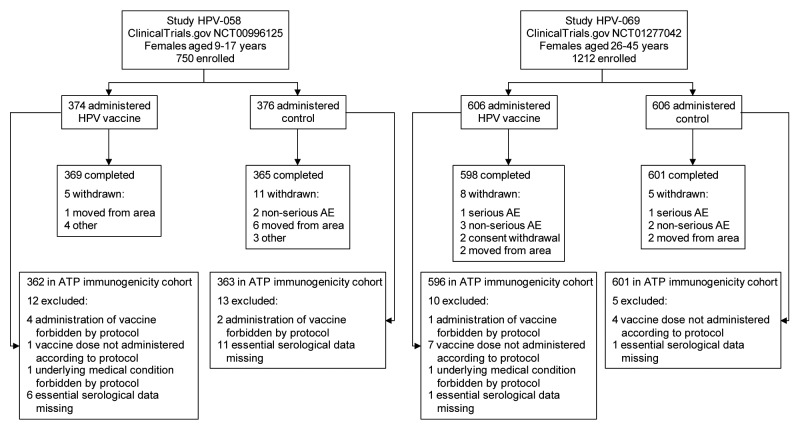

Efficacy cannot feasibly be evaluated in Chinese females below 18 y of age due to the expected small number of clinical cases in this age group, and because ethical and cultural standards do not allow the necessary invasive examinations to ascertain clinical and virological endpoints. The largest impact of vaccination is, however, expected to result from high coverage of young adolescent girls prior to onset of sexual activity and exposure to oncogenic HPV types. Vaccination of adult women (i.e., over the age of 25 y) would also be beneficial, as they are still at risk of acquiring a new oncogenic HPV infection or reinfection, which may progress to cervical cancer.9 Therefore, 2 studies (Fig. 1) were conducted in Chinese females to evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: one study was conducted in pre-teen and adolescent females aged 9–17 y (Study HPV-058; ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT00996125) and one study was conducted in women aged 26–45 y (Study HPV-069; NCT01277042), to complement data currently being generated in the phase II/III efficacy trial in Chinese women aged 18–25 y (Study HPV-039; NCT00779766).8

Figure 1. Overview of study design for each study. In each study, subjects were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive vaccine or control. In Study HPV-058, conducted in females aged 9–17 y, the control was Al(OH)3. In Study HPV-069, conducted in females aged 26–45 y, the control was hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine. N, number of subjects planned.

The primary objective of the 2 studies was to show the non-inferiority of immune responses to HPV-16 and HPV-18 vaccine components, in terms of geometric mean antibody titer (GMT) ratios for females aged 9–17 y and seroconversion rates for females aged 26–45 y, as compared with the immune responses in women aged 18–25 y enrolled in Study HPV-039. Secondary objectives were to describe the HPV-16/18 immune response in terms of GMTs and seropositivity rates, to evaluate reactogenicity after each vaccine dose, and to evaluate safety throughout the study period.

Results

Study population

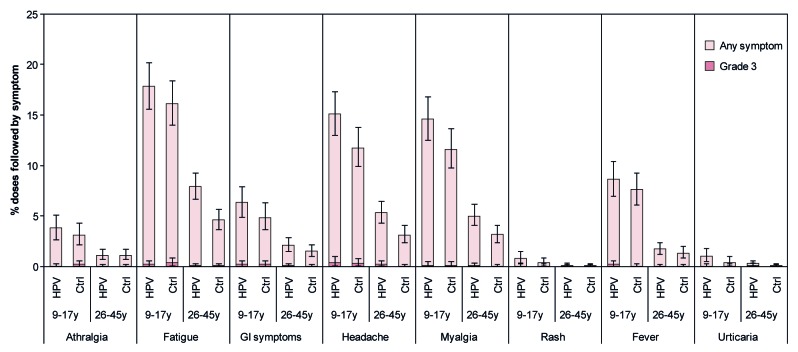

A total of 1962 girls and women were enrolled across the 2 studies (750 females aged 9–17 y and 1212 females aged 26–45 y) and randomized 1:1 to receive HPV vaccine (980 females in total) or control (982 females in total) (Fig. 2). At least 97% of participants in each group received the scheduled 3 doses of vaccine or control (Table 1), at least 97% completed the study to Month 12, and at least 96% were included in the according-to-protocol (ATP) cohorts for analysis of immunogenicity. Reasons for withdrawal from the study, and exclusion from the ATP cohorts for immunogenicity, are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Flow of participants through each study. AE, adverse event; ATP, according-to-protocol.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics.

| Study HPV-058 Females aged 9–17 y | Study HPV-069 Females aged 26–45 y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV vaccine | Control | Total | HPV vaccine | Control | Total | |

| Total vaccinated cohort | ||||||

| N | 374 | 376 | 750 | 606 | 606 | 1212 |

| Mean (SD) age | 13.1 (2.44) | 13.1 (2.42) | 13.1 (2.43) | 35.8 (4.92) | 35.6 (5.06) | 35.7 (4.99) |

| Age strata, n (%) | ||||||

| 9–11 y | 112 (29.9) | 113 (30.1) | 225 (30.0) | - | - | - |

| 12–14 y | 125 (33.4) | 125 (33.2) | 250 (33.3) | - | - | - |

| 15–17 y | 137 (36.6) | 138 (36.7) | 275 (36.7) | - | - | - |

| 26–35 y | - | - | - | 304 (50.2) | 304 (50.2) | 608 (50.2) |

| 36–45 y | - | - | - | 302 (49.8) | 302 (49.8) | 604 (49.8) |

| Number of doses received, n (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) |

| 2 | 4 (1.1) | 9 (2.4) | 13 (1.7) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 6 (0.5) |

| 3 | 369 (98.7) | 366 (97.3) | 735 (98.0) | 599 (98.8) | 602 (99.3) | 1201 (99.1) |

| ATP cohort for immunogenicity | ||||||

| N | 362 | 363 | 725 | 596 | 601 | 1197 |

| HPV-16 seropositive, n (%) | 36 (9.9) | 40 (11.0) | 76 (10.5) | 251 (42.1) | 257 (42.8) | 508 (42.4) |

| HPV-18 seropositive, n (%) | 24 (6.6) | 19 (5.2) | 43 (5.9) | 231 (38.8) | 200 (33.3) | 431 (36.0) |

ATP, according-to-protocol; SD, standard deviation. Data are number of subjects (percentage) unless specified otherwise. HPV-16 seropositivity defined as an ELISA concentration ≥ 8 ELISA units per milliliter (EU/mL). HPV-18 seropositivity defined as an ELISA concentration ≥ 7 EU/mL. The control was Al(OH)3 for females aged 9–17 y and hepatitis B vaccine for females aged 26–45 y.

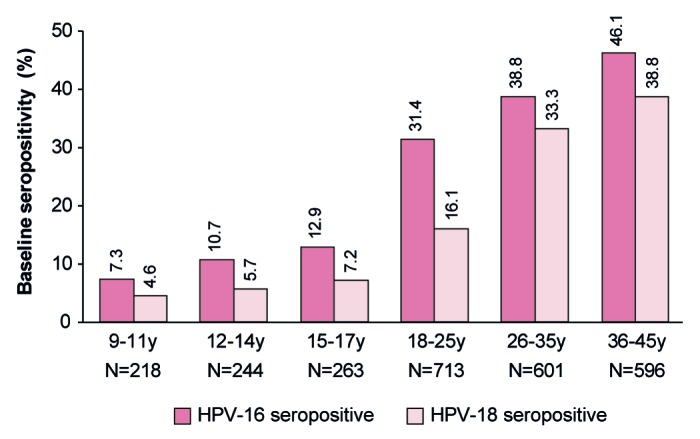

Within each study, the vaccine and control groups were well matched with regard to demographic and baseline characteristics (Table 1). HPV-16 and HPV-18 seropositivity rates at baseline for subjects in the ATP cohort for immunogenicity were 10.5% and 5.9%, respectively, for girls aged 9–17 y and 42.4% and 36.0%, respectively for women aged 26–45 y (Table 1). When analyzed by smaller age strata, HPV-16 and HPV-18 seropositivity rates increased steadily with age from 7.3% and 4.6%, respectively, for girls aged 9–11 y to 46.1% and 38.8%, respectively, for women aged 36–45 y (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Baseline seropositivity rate by age strata. Data are shown for the ATP cohort for immunogenicity for all subjects in HPV vaccine and control groups combined. Data for females aged 9–11, 12–14, and 15–17 y are from Study HPV-058. Data for females aged 18–25 y are from Study HPV-039. Data for females aged 26–35 and 36–45 y are from Study HPV-069. HPV-16 seropositivity defined as an ELISA concentration ≥ 8 EU/mL. HPV-18 seropositivity defined as an ELISA concentration ≥7 EU/mL. Numbers above each bar are the percentage of seropositive subjects per cohort.

Immunogenicity

In Chinese females aged 9–17 y, HPV-16 and HPV-18 immune responses (by GMT) one month after the third vaccine dose were non-inferior to immune responses in Chinese females aged 18–25 y enrolled in Study HPV-039, since the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the GMT ratio (GMT in initially seronegative females aged 18–25 y divided by GMT in initially seronegative females aged 9–17 y) was below the pre-defined clinical limit for non-inferiority of 2 for both antigens (Table 2).

Table 2. Non-inferiority assessment of immune response one month after the third vaccine dose in initially seronegative females aged 9–17 y or 26–45 y vs. those aged 18–25 y.

| Study HPV-058 (test) Females aged 9–17 y | Study HPV-039 (reference) Females aged 18–25 y | Comparison (reference/test) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody | N | GMT (95% CI), EU/mL | N | GMT (95% CI), EU/mL | GMT ratio (95% CI)* |

| Anti-HPV-16 | 326 | 18682.4 (17162.7, 20336.6) | 244 | 6996.2 (6211.7, 7879.7) | 0.37 (0.32, 0.43) |

| Anti-HPV-18 | 338 | 7882.4 (7079.0, 8777.1) | 289 | 3309.4 (2941.9, 3722.8) | 0.42 (0.36, 0.49) |

| Study HPV-069 (test) Females aged 26–45 y | Study HPV-039 (reference) Females aged 18–25 y | Comparison (reference – test) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Seroconversion rate, n (%) | N | Seroconversion rate, n (%) | Seroconversion difference (95% CI)† | |

| Anti-HPV-16 | 345 | 345 (100) | 247 | 247 (100) | 0.00 (–1.53, 1.10) |

| Anti-HPV-18 | 365 | 363 (99.5) | 299 | 298 (99.7) | 0.21 (–1.36, 1.68) |

CI, confidence interval; EU/mL, ELISA units per milliliter; GMT, geometric mean antibody titer; N, number of subjects with pre- and post-vaccination results available; n (%), number (percentage) of subjects. Data are shown for initially seronegative subjects in the ATP cohort for immunogenicity.*HPV-16 and HPV-18 immune responses were considered to be non-inferior if, for each HPV antigen, the upper limit of the two-sided 95% CI for the GMT ratio (GMT for females aged 18–25 y divided by GMT for females aged 9–17 y) was below 2.†HPV-16 and HPV-18 immune responses were considered to be non-inferior if, for each HPV antigen, the upper limit of the two-sided 95% CI for the difference in seroconversion rates (for females aged 18–25 y minus females aged 26–45 y) was below 5%.

In Chinese females aged 26–45 y, HPV-16 and HPV-18 immune responses (by seroconversion) one month after the third vaccine dose were also non-inferior to immune responses in Chinese females aged 18–25 y enrolled in Study HPV-039, since the upper limit of the 95% CI for the difference in the seroconversion rate (percentage of initially seronegative females aged 18–25 y who seroconverted minus percentage of initially seronegative females aged 26–45 y who seroconverted) was below the pre-defined clinical limit for non-inferiority of 5% for both antigens (Table 2).

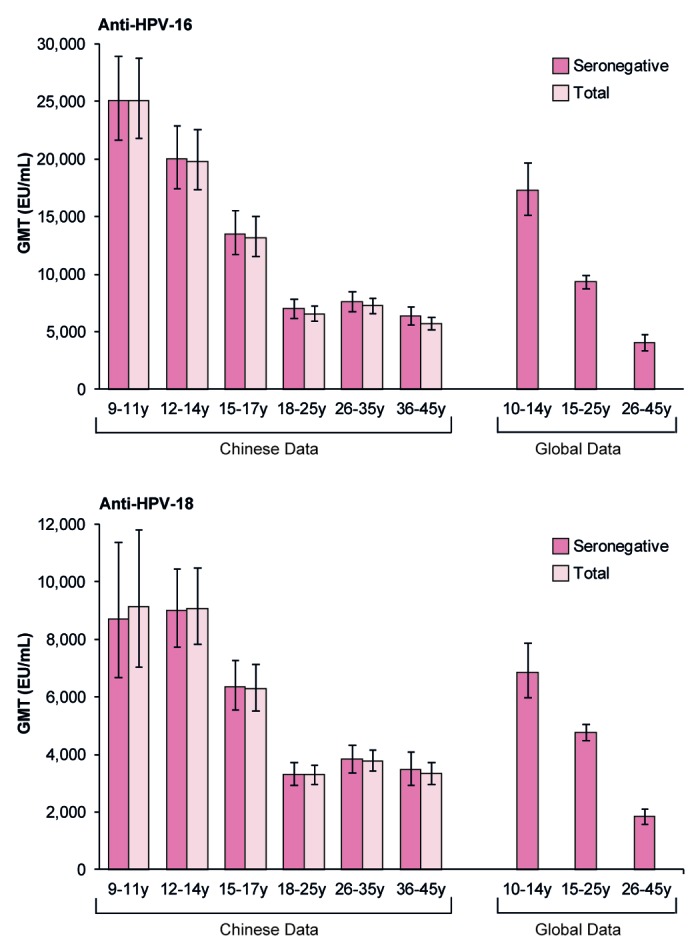

In each study, all initially seronegative subjects in the ATP cohort for immunogenicity had seroconverted for anti-HPV-16 antibodies 1 mo after the third vaccine dose, and at least 99.4% of initially seronegative subjects had seroconverted for anti-HPV-18 antibodies (Table 3). One month after the third vaccine dose, anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 GMTs measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were 2- to 3-fold higher in initially seronegative females aged 9–17 y compared with females aged 18–25 y, whereas GMTs were similar for initially seronegative females aged 26–45 y compared with females aged 18–25 y (Table 3). When considered by smaller age strata, there was a trend for higher GMTs for both anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 antibodies in the youngest age groups (9–11 and 12–14 y) than in older age groups, for initially seronegative subjects and for all subjects regardless of initial serostatus (Fig. 4; Tables S1 and S2).

Table 3. Seropositivity rates and GMTs for anti-HPV-16 and -18 antibodies by age strata: vaccine group.

| Antibody | Age (years) | Pre-vaccination status | Time | N | Seropositive | GMT (EU/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Value | LL | UL | |||||

| Anti-HPV-16 | 9–17 | Seronegative | Pre | 326 | 0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Month 7 | 326 | 326 | 100 | 18682.4 | 17162.7 | 20336.6 | |||

| Seropositive | Pre | 36 | 36 | 100 | 19.9 | 16.6 | 23.8 | ||

| Month 7 | 36 | 36 | 100 | 15571.9 | 11700.0 | 20725.3 | |||

| Total | Pre | 362 | 36 | 9.9 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.9 | ||

| Month 7 | 362 | 362 | 100 | 18347.1 | 16915.2 | 19900.2 | |||

| 18–25 | Seronegative | Pre | 244 | 0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | |

| Month 7 | 244 | 244 | 100 | 6996.2 | 6211.7 | 7879.7 | |||

| Seropositive | Pre | 107 | 107 | 100 | 27.6 | 22.8 | 33.4 | ||

| Month 7 | 107 | 107 | 100 | 5698.0 | 4702.6 | 6904.1 | |||

| Total | Pre | 351 | 107 | 30.5 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 8.0 | ||

| Month 7 | 351 | 351 | 100 | 6571.8 | 5939.0 | 7272.2 | |||

| 26–45 | Seronegative | Pre | 345 | 0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | |

| Month 7 | 345 | 345 | 100 | 7000.4 | 6426.0 | 7626.2 | |||

| Seropositive | Pre | 251 | 251 | 100 | 32.5 | 29.2 | 36.3 | ||

| Month 7 | 251 | 251 | 100 | 5741.7 | 5218.9 | 6316.9 | |||

| Total | Pre | 596 | 251 | 42.1 | 9.7 | 8.8 | 10.6 | ||

| Month 7 | 596 | 596 | 100 | 6439.8 | 6039.8 | 6866.3 | |||

| Anti-HPV-18 | 9–17 | Seronegative | Pre | 338 | 0 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Month 7 | 338 | 336 | 99.4 | 7882.4 | 7079.0 | 8777.1 | |||

| Seropositive | Pre | 24 | 24 | 100 | 21.9 | 16.8 | 28.5 | ||

| Month 7 | 24 | 24 | 100 | 9140.0 | 6318.3 | 13221.8 | |||

| Total | Pre | 362 | 24 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.2 | ||

| Month 7 | 362 | 360 | 99.4 | 7960.2 | 7181.3 | 8823.6 | |||

| 18–25 | Seronegative | Pre | 289 | 0 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Month 7 | 289 | 288 | 99.7 | 3309.4 | 2941.9 | 3722.8 | |||

| Seropositive | Pre | 62 | 62 | 100 | 20.7 | 16.9 | 25.4 | ||

| Month 7 | 62 | 62 | 100 | 3242.2 | 2735.8 | 3842.4 | |||

| Total | Pre | 351 | 62 | 17.7 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.2 | ||

| Month 7 | 351 | 350 | 99.7 | 3297.4 | 2980.2 | 3648.5 | |||

| 26–45 | Seronegative | Pre | 365 | 0 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| Month 7 | 365 | 363 | 99.5 | 3656.3 | 3301.9 | 4048.7 | |||

| Seropositive | Pre | 231 | 231 | 100 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 18.1 | ||

| Month 7 | 231 | 231 | 100 | 3421.3 | 3089.8 | 3788.2 | |||

| Total | Pre | 596 | 231 | 38.8 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.9 | ||

| Month 7 | 596 | 594 | 99.7 | 3563.3 | 3310.0 | 3836.0 | |||

Data are shown for the according-to-protocol cohort for immunogenicity for subjects in the HPV vaccine group. GMT, geometric mean antibody titer; LL, lower limit of 95% confidence interval; N, number of subjects with results available; n/%, number/percentage of subjects in the specified category; UL, upper limit of 95% confidence interval. Data for females aged 9–17 y are from Study HPV-058. Data for females aged 18–25 y are from Study HPV-039. Data for females aged 26–45 y are from Study HPV-069. HPV-16 seropositivity defined as an ELISA concentration ≥ 8 EU/mL. HPV-18 seropositivity defined as an ELISA concentration ≥ 7 EU/mL.

Figure 4. Geometric mean antibody titers and associated 95% confidence intervals one month after the third vaccine dose, by age. Data are shown for the ATP cohort for immunogenicity. EU/mL, ELISA units per milliliter; GMT, geometric mean antibody titer; Initially seronegative, subjects who were seronegative at baseline; Total, all subjects regardless of baseline serostatus; y, years. Chinese data are from the following studies: females aged 9–11, 12–14, and 15–17 y from Study HPV-058; females aged 18–25 y from Study HPV-039; females aged 26–35 and 36–45 y from Study HPV-069. Global data are from the following studies: females aged 10–14 y from Study HPV-012 conducted in Europe (NCT00337818);13 females aged 15–25 y from Study HPV-008 conducted in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, Mexico, Thailand, and the USA (NCT00122681);11 females aged 26–45 y from Study HPV-014 conducted in Europe (NCT00196937).12 Note that published global data are not available for smaller age strata.

Reactogenicity and safety

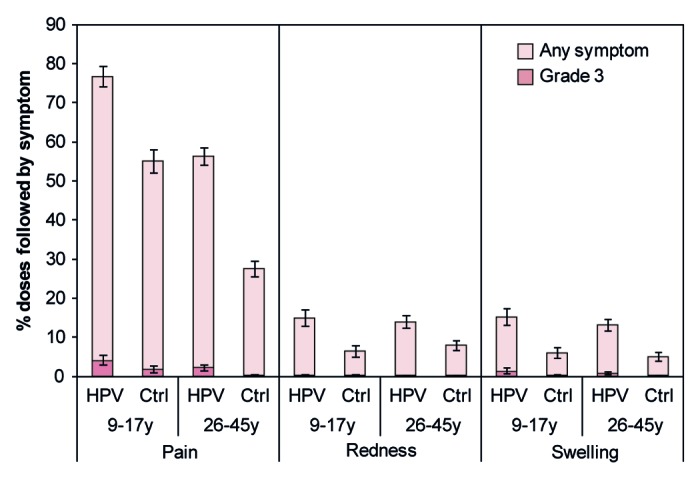

The HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine had an acceptable safety profile when administered to healthy Chinese females aged 9–17 y and 26–45 y. In both studies, the incidence of solicited local symptoms following any dose was generally higher in the vaccine group than the control group (Fig. 5). The incidence of grade 3 local symptoms following any dose was 5.2% for vaccine and 2.0% for control for 9–17 y-olds, and 3.0% for vaccine and 0.3% for control for 26–45 y-olds. Few local symptoms continued beyond the 7-d observation period. In both vaccine and control groups, a larger proportion of doses were followed by pain for younger females aged 9–17 y (76.8% for vaccine; 55.1% for control) than for older females aged 26–45 y (56.3% for vaccine; 27.5% for control) (Fig. 5; Table S3).

Figure 5. Solicited local symptoms reported during the 7-d period following any vaccine dose. Data are shown for the total vaccinated cohort. Bars represent the percentage of doses followed by the specified symptom at least once in the 7-d period after any vaccine dose with exact 95% confidence interval. Ctrl, control; HPV, HPV vaccine. The control was Al(OH)3 for females aged 9–17 y and hepatitis B vaccine for females aged 26–45 y. Grade 3 redness or swelling defined as surface area ≥50 mm in diameter. Grade 3 pain defined as preventing normal activity. Data for females aged 9–17 y are from Study HPV-058. Data for females aged 26–45 y are from HPV-069.

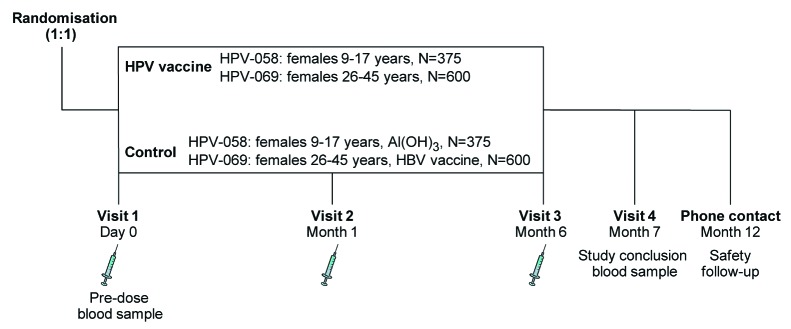

Solicited general symptoms reported during the 7-d period following any vaccine dose are shown in Figure 6. The incidence of grade 3 general symptoms was low and few general symptoms continued beyond the 7-d observation period. In both vaccine and control groups, a larger proportion of doses were followed by arthralgia, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, myalgia, and fever for younger females aged 9–17 y than for older females aged 26–45 y (Fig. 6; Table S3).

Figure 6. Solicited general symptoms reported during the 7-d period following any vaccine dose. Data are shown for the total vaccinated cohort. Bars represent the percentage of doses followed by the specified symptom at least once in the 7-d period after any vaccine dose with exact 95% confidence interval. Ctrl, control; HPV, HPV vaccine; GI, gastrointestinal. The control was Al(OH)3 for females aged 9–17 y and hepatitis B vaccine for females aged 26–45 y. Fever defined as oral/axillary temperature >37.0 °C; grade 3 fever defined as oral/axillary temperature >39.0 °C. For all other symptoms, grade 3 defined as symptom that prevents normal activity. Data for females aged 9–17 y are from Study HPV-058. Data for females aged 26–45 y are from Study HPV-069.

The incidence of unsolicited symptoms during the 30-d period after vaccination was higher for younger females aged 9–17 y in Study HPV-058 (37.2% for vaccine; 33.2% for control) than for older females aged 26–45 y in Study HPV-069 (5.3% for vaccine; 5.9% for control) (Table 4). Few grade 3 unsolicited symptoms were reported.

Table 4. Summary of safety and pregnancy outcomes.

| Study HPV-058 Females aged 9–17 y | Study HPV-069 Females aged 26–45 y | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV vaccine n = 374 | Control n = 376 | HPV vaccine n = 606 | Control n = 606 | |||||

| n(%) | [95% CI] | n(%) | [95% CI] | n(%) | [95% CI] | n(%) | [95% CI] | |

| 30-d period after vaccination | ||||||||

| Unsolicited symptoms | 139 (37.2) | [32.3, 42.3] | 125 (33.2) | [28.5, 38.3] | 32 (5.3) | [3.6, 7.4] | 36 (5.9) | [4.2, 8.1] |

| Grade 3 symptoms | 0 (0.0) | [0.0, 1.0] | 3 (0.8) | [0.2, 2.3] | 2 (0.3) | [0.0, 1.2] | 2 (0.3) | [0.0, 1.2] |

| Entire study period to Month 12 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse events | 5 (1.3) | [0.4, 3.1] | 2 (0.5) | [0.1, 1.9] | 3 (0.5) | [0.1, 1.4] | 3 (0.5) | [0.1, 1.4] |

| Related serious adverse events | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Medically significant conditions* | 14 (3.7) | [2.1, 6.2] | 11 (2.9) | [1.5, 5.2] | 5 (0.8) | [0.3, 1.9] | 7 (1.2) | [0.5, 2.4] |

| Potential immune-mediated diseases† | NA | - | NA | - | 0 (0.0) | - | 0 (0.0) | - |

| New onset autoimmune diseases‡ | 0 (0.0) | [0.0, 1.0] | 2 (0.5) | [0.1, 1.9] | NA | - | NA | - |

| Pregnancy | 0 (0.0) | - | 0 (0.0) | - | 4 (0.7) | - | 1 (0.2) | - |

| Elective termination - no apparent congenital anomaly | - | - | - | - | 4 (0.7) | - | 1 (0.2) | - |

Data are shown for the total vaccinated cohort. N, number of subjects evaluated; n (%), number (percentage) of subjects reporting the symptom type at least once during the specified period; NA, not applicable (new onset autoimmune disease defined as endpoint in study in females aged 9–17 y and potential immune-mediated disease defined as endpoint in study in females aged 26–45 y). 95% CI, exact 95% confidence interval (note that 95% CI were not calculated for some endpoints). The control was Al(OH)3 for females aged 9–17 y and hepatitis B vaccine for females aged 26–45 y. *Medically significant conditions defined as adverse events prompting emergency room or physician visits that were not related to common diseases or serious adverse events that were not related to common diseases.†A potential immune-mediated disease was defined as a medically significant condition that included autoimmune diseases and other inflammatory and/or neurological disorders of interest which may or may not have had an autoimmune etiology.‡A new onset autoimmune disease was defined as an autoimmune disease that was considered to be of new onset based on blinded review of the reported symptoms and the subject’s pre-vaccination medical history by a physician from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

A small proportion of subjects in each study reported serious adverse events, other medically significant conditions, potential immune-mediated diseases (or new onset autoimmune diseases) during the entire study period to Month 12, and numbers were balanced across vaccine and control groups within each study (Table 4). None of the serious adverse events was considered to have a causal relationship to vaccination by the investigator, and no event had a fatal outcome.

No pregnancies were reported for subjects aged 9–17 y. Five pregnancies were reported for subjects aged 26–45 y (vaccine: 4; control: 1) and all 5 women decided to have an elective termination; no apparent congenital abnormalities were noted (Table 4).

Discussion

As of December 2013, the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine has been licensed in over 130 countries and approximately 41 million doses have been distributed globally. The vaccine is not currently licensed in mainland China, but is licensed in Hong Kong and Taiwan. As part of the regulatory evaluation of this vaccine to support licensure in China, we report data from 2 clinical trials conducted in teenage/adolescent girls and adult women. These studies show that immunogenicity and safety profiles following administration of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine to healthy Chinese girls and women are consistent with those reported previously in females from diverse geographic settings.10-14 Importantly, we also show that HPV-16 and HPV-18 specific immune responses one month after the third vaccine dose in Chinese females aged 9–17 y and 26–45 y are non-inferior to those elicited in Chinese females aged 18–25 y enrolled in a separate trial, which has demonstrated vaccine efficacy.8 This is the first evaluation, to our knowledge, of the immunogenicity and safety of an HPV vaccine in Chinese females across a wide range of ages from 9–45 y. This information will be useful to policy makers in China and other Asian countries to support decisions regarding HPV vaccination for the prevention of cervical cancer.

There is no identified immunological correlate of protection for HPV infection and subsequent disease, however, protection is thought to be mediated by neutralising antibodies that either transude across the cervical epithelium or are exuded at the site of trauma.15,16 Serum antibody titers measured by ELISA correlate well with neutralising antibody titers17 and antibody levels in cervicovaginal secretions.18,19 Thus, using the principle of immunobridging, similar efficacy may be inferred for younger (9–17 y) and older (26–45 y) cohorts of Chinese females due to non-inferiority of immune responses compared with Chinese females aged 18–25 y. Anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 antibody responses elicited in Chinese females were also similar to those previously reported with the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in corresponding age groups of females participating in global efficacy studies10,11,20-29 and in studies conducted in low-resource settings such as India and Africa.30,31

We found that anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 GMTs one month after the last vaccine dose were 2- to 3-fold higher for Chinese females aged 9–17 y compared with those aged 18–25 y, and that antibody titers were particularly high in the youngest cohorts of girls aged 9–11 and 12–14 y. This finding is in line with previous trials, which show that antibody titers elicited following vaccination with the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine are higher for preteen/adolescent girls compared with young women.13,32-34 It has previously been shown, in women aged 15–25 y, that HPV-16 and -18 antibodies persist for at least 8 y after vaccination,25 and statistical modeling of serological data from these women predicts that antibody levels will remain well above levels induced by natural infection for at least 20 y.35 Therefore, using the principle of immunobridging, the high antibody titers we observed in preteen/adolescent Chinese girls are likely to result in a long duration of antibody persistence, which is important as vaccinees will require protection throughout their sexually active life against HPV infection and associated disease.

The HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine has been shown to produce a robust immune response in adult women,12,29,36 although a decrease in GMTs with increasing age was observed.12,36 In the current trials conducted in China, anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 GMTs in women aged 26–35 y and 36–45 y were of a similar magnitude to those elicited in women aged 18–25 y, i.e., there was not a further reduction in serum antibody titers beyond 25 y of age in the Chinese population evaluated. In all age groups, anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 antibody titers one month after the last vaccine dose were many fold higher than those elicited after natural infection,11 and were also higher than the plateau levels observed in a long-term follow-up efficacy study of women aged 15–25 y, in which sustained efficacy has been demonstrated.23

Humoral immunity to natural HPV infection has not been fully characterized and HPV serostatus determined using assays based on HPV L1 virus-like particles is an imperfect marker of past or current HPV infection.37,38 Nevertheless, baseline HPV seroprevalence provides some indication of cumulative exposure to HPV infection, and may still be used to inform vaccine program implementation. We observed that a small proportion of girls aged 9–11 y were already HPV-16 and/or HPV-18 seropositive (i.e., had detectable antibody levels) at study entry. Baseline HPV-16 and HPV-18 seropositivity then increased with increasing age as previously reported in global seroprevalence studies39 and in surveillances conducted nationally and in several Chinese regions.40 Ideally, Chinese preteens/adolescents would be vaccinated before the onset of sexual activity and exposure to HPV infection. However, as high vaccine efficacy has previously been shown against virological and histopathological endpoints associated with vaccine HPV types in women who were DNA negative regardless of their baseline serological status,41 a significant proportion of adult Chinese women may still benefit from HPV vaccination.

Safety and reactogenicity profiles of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine observed in Chinese girls and women enrolled in the current studies are generally in line with global safety data.14 As observed previously in non-Chinese trials, the incidence of solicited local symptoms was generally higher in the vaccine group than the control group,14 but this higher reactogenicity did not impact on the willingness of subjects to receive all 3 vaccine doses (compliance was high in each group). There was a decrease in the frequency of reporting of solicited and unsolicited symptoms in the older cohort of Chinese females, compared with the younger cohort, as reported previously with this vaccine.12 There are various factors which could explain the differential reporting rate, such as age-related differences in sensitivity, or tendency to report adverse events.

A strength of our analysis is that similar designs and testing methodologies were used for each of the Chinese trials, giving confidence in comparisons of immunogenicity data across studies. A clinical endpoint efficacy trial is the gold standard for demonstrating vaccine efficacy in a particular population, but immunobridging is widely recognized to infer comparability of vaccine efficacy from one population to another when it is not practical to conduct such an efficacy trial. Although these trials were conducted at a small number of centers within Jiangsu Province, based on previous global experience with the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine (including other Asian settings and Taiwanese and Filipino women enrolled in the Papilloma TRIal against Cancer In young Adults [PATRICIA] efficacy trial, NCT00122681), we would not expect regional variations in the immune responses elicited by the vaccine.11,26,27,30,31,42,43 However, baseline HPV seroprevalence rates may vary by geographic region.39,44 One limitation of these trials is that the immunogenicity evaluation was confined to acute measurement of anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 serum antibodies. Cell-mediated immunity, cross-reacting immune responses to other high risk HPV types, and longevity of immune responses were not evaluated.

In summary, cervical cancer is a major health problem in Chinese women especially among those living in rural areas. The implementation of effective cervical cancer screening across all regions of China is challenging,45 therefore, HPV prophylactic vaccination before the onset of sexual activity offers the potential to decrease the burden of this disease. The HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine was shown to have good immunogenicity and to have an acceptable safety profile in Chinese girls and women aged 9 to 45 y.

Participants AND Methods

Study design and participants

A schematic of the trial designs is shown in Figure 1. Study HPV-058 was a phase III, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial with 2 parallel groups conducted at one site (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Taizhou City, Jiangsu) in China between October 2009 and December 2010. Healthy Chinese females aged 9–17 y at the time of first vaccination were eligible for inclusion. Study HPV-069 was a phase III, observer-blind, randomized, controlled trial with 2 parallel groups conducted at one site (CDC, Jintan City, Jiangsu) in China between February 2011 and February 2012. Healthy Chinese females aged 26–45 y at the time of first vaccination were eligible for inclusion.

For both studies, subjects had to have a negative urine pregnancy test at screening. Subjects of childbearing potential were to be abstinent or to have used adequate contraceptive precautions for 30 d prior to first vaccination and agreed to continue such precautions for 2 months after completion of the vaccination series. Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding, had a confirmed or suspected immunosuppressive or immunodeficient condition, an allergic disease likely to be exacerbated by any component of the vaccine, or previously received HPV vaccination or 3-O-desacyl-4’-monophosphoryl lipid A were excluded.

The HPV-058 and HPV-069 trials were registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (registration numbers NCT00996125 and NCT01277042, respectively) and were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Study protocols and other materials were reviewed and approved by the ethics committees of the CDC, Jiangsu Province. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject or the subject’s parent/legally acceptable representative and informed assent was obtained from subjects below the legal age of consent.

Interventions

Subjects were randomized (1:1) to receive 3 doses of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine (Cervarix®, GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) or control according to a 0, 1, 6-mo schedule. The control was aluminum hydroxide [Al(OH)3] in Study HPV-058 and hepatitis B vaccine (Engerix-B™, GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) in Study HPV-069. The vaccine and relevant control were supplied as liquids in individual pre-filled syringes with 0.5 mL to be administered intramuscularly on each dosing occasion. Enrolment was age-stratified (Study HPV-058: 9–11, 12–14, 15–17 y; Study HPV-069: 26–35, 36–45 y) with approximately equal numbers of subjects enrolled in each age stratum within a study. The randomization schedules for each study were generated by GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines using validated software. Treatment allocation at site used a central randomization system on internet. Blinding was maintained for all subjects, investigators and study staff, and sponsor personnel involved in the conduct of the studies. The serological data were not available during the course of the study to any person involved in the conduct of the study.

Immunogenicity assessment

Blood samples for immunogenicity evaluation were taken at month 0 (pre-vaccination) and month 7. Anti-HPV-16 and -18 antibodies were determined by ELISA as described previously.17 The same methodology was also used in the comparator trial, Study HPV-039. A central laboratory was used (National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, China) and assay kits were standardised. Seropositivity was defined as an antibody concentration greater than or equal to 8 ELISA units per milliliter (EU/mL) for HPV-16 and 7 EU/mL for HPV-18.

In addition to the comparison between the measured anti-HPV-16 and -18 GMTs (ELISA) and the GMTs in Chinese subjects aged 18–25 y from Study HPV-039 (NCT00779766), comparison is made with global data from the following studies: subjects aged 10–14 y from Study HPV-012 conducted in Europe (NCT00337818);13 subjects aged 15–25 y from Study HPV-008 conducted in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, Mexico, Thailand, and the USA (NCT00122681);11 subjects aged 26–45 y from Study HPV-014 conducted in Europe (NCT00196937).12

Safety assessment

Solicited local and general symptoms occurring within 7 d after each vaccination were recorded by the subject on diary cards. Unsolicited symptoms were recorded for 30 d after each vaccination. Fever was defined as oral/axillary temperature >37.0 °C. Grade 3 symptoms were defined as redness or swelling >50 mm in diameter, oral/axillary temperature >39.0 °C, urticaria distributed on at least 4 body areas and, for other symptoms, as preventing normal activity. Pregnancies and outcomes, serious adverse events, medically significant conditions (defined as adverse events prompting emergency room or physician visits that were not related to common diseases or serious adverse events that were not related to common diseases), potential immune-mediated diseases (Study HPV-069) or new onset autoimmune diseases (Study HPV-058) were reported throughout the study. A potential immune-mediated disease was defined as a medically significant condition that included an autoimmune disease and other inflammatory and/or neurological disorder of interest which may or may not have had an autoimmune etiology. A new onset autoimmune disease was defined as a potential autoimmune disease that was considered to be of new onset based on blinded review of the reported symptoms and the subject’s pre-vaccination medical history by a physician from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

Statistical methods

The primary objective of Study HPV-058 was to demonstrate non-inferiority of HPV-16 and -18 immune responses with respect to GMTs one month after the third vaccine dose in subjects aged 9–17 y, compared with subjects aged 18–25 y enrolled in Study HPV-039, in the subset of subjects initially seronegative for the corresponding HPV type. Non-inferiority was demonstrated if, for each HPV antigen, the upper limit of the 95% CI for the GMT for subjects in Study HPV-039 (18–25 y) divided by the GMT for subjects in Study HPV-058 (9–17 y) was below 2. For sample size estimation it was assumed that 20% of subjects would be non-evaluable at month 7, to compensate for attrition due to early withdrawal, initially seropositive subjects, and to ensure a sufficient number for inclusion in the ATP cohort for analysis of immunogenicity. A target enrolment of 375 subjects in each group in Study HPV-058 was estimated to give approximately 300 evaluable subjects in the vaccine group at month 7. Approximately 400 subjects were to be enrolled in the immunogenicity subset of Study HPV-039 in the vaccine group and to determine the sample size for Study HPV-058 it was assumed that 320 of these subjects would be evaluable at month 7. This sample size would allow the detection of a 2-fold difference between the age groups in terms of GMTs for both anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 with at least 90% power.

The primary objective of Study HPV-069 was to demonstrate non-inferiority of HPV-16 and -18 immune responses in terms of seroconversion rates one month after the third vaccine dose in subjects aged 26–45 y, compared with subjects aged 18–25 y enrolled in Study HPV-039, in the subset of subjects initially seronegative for the corresponding HPV type. Non-inferiority was demonstrated if, for each HPV antigen, the upper limit of the 95% CI for the difference between the percentage of subjects who seroconverted in Study HPV-039 (18–25 y) and the percentage of subjects who seroconverted in Study HPV-069 (26–45 y) was below 5%. For sample size estimation for Study HPV-069, a higher non-evaluability rate of 40% at month 7 was assumed as it was anticipated that baseline HPV seropositivity would be higher in these older women. A target enrolment of 600 subjects in each group in Study HPV-069 was estimated to give approximately 360 evaluable subjects in the vaccine group at month 7. Approximately 400 subjects were to be enrolled in the immunogenicity subset of Study HPV-039 in the vaccine group and to determine the sample size for Study HPV-069 it was estimated that 250 of these subjects would be evaluable at month 7. This sample size would allow the detection of a 5% difference between the age groups in terms of seroconversion rates for both anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 with at least 90% power.

Immunogenicity analyses were performed on the ATP cohort for immunogenicity, which included all evaluable subjects (meeting all eligibility criteria, complying with the procedures and intervals defined in the protocol, with no elimination criteria during the study) for whom immunogenicity data were available. For each study, seroconversion and seropositivity rates with exact 95% CI, and GMTs with 95% CIs, were calculated by pre-vaccination antibody status.

Safety data are summarized for the total vaccinated cohort, which included all subjects who received at least one vaccine dose for whom data were available. Safety data are summarized using descriptive statistics (number and percentage of subjects with events and corresponding exact 95% CI) and no inferential analyses were performed.

Role of the authors and the funding source

GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines designed the study in collaboration with investigators, and coordinated gathering, analysis, and interpretation of data, and writing of the study reports. Investigators from the HPV-058 and HPV-069 studies gathered data for the trials and cared for the subjects. All authors contributed to the design and/or data collection and/or data analysis and/or the results interpretation related to the HPV-058 study and/or the HPV-069 study. All authors had full access to the complete final study reports, reviewed the manuscript draft(s) and took the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The manuscript was developed and coordinated by the authors in collaboration with an independent medical writer and a publication manager, both working on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following potential conflicts of interest. F.Z. received grants, fees and travel support during the studies from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies. G.X., X.Y., J.Y., and X.Z. received grant through their institution for the conduct of the trials from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies. J.L., Y.H., J.W., H.Z. have no conflicts of interest to declare. H.T., P.S., S.K.D., D.D., D.B., and F.S. are employees of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies. Q.D. is a former employee of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies. D.D., D.B., and F.S. stock/stock options/restricted shares from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

Acknowledgments

The HPV-058 (NCT00996125) and HPV-069 (NCT01277042) clinical trials and the present publication were funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA (registered name of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

The authors would like to thank the study participants and the staff members of the different study sites for their contribution to the study. In addition, the authors would like to thank the following contributors to the study and/or publication.

Global HPV-058 study management: Garry Edwards (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

Global HPV-069 study management: Daphné Dumont (Harrison Clinical Research, on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

Writing of study protocols and/or reports: Chitra Nair, Christine Van Hoof (all from GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

Additional contributors to the Study HPV-058: Grégory Catteau, Marie-Pierre David, Marc Fourneau, Amulya Jayadev, Jenny Jiang, Sylviane Poncelet, Keerthi Thomas, Christine Van Hoof (all from GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines);

Additional contributors to the Study HPV-069: Catherine Bougelet, Brecht Geeraerts, Amulya Jayadev, Jenny Jiang, Edwin Kolp, Sheetal Verlekar (all from GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines), Dorothée Méric (formerly from GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

Publication writing: Julie Taylor (Peak Biomedical Ltd, UK, on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

Editorial assistance and publication coordination: Jean-Michel Heine (Keyrus Biopharma, Belgium, on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ATP

according-to-protocol

- CDC

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

confidence interval

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EU

ELISA units

- GMT

geometric mean antibody titre

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- PATRICIA

Papilloma TRIal against Cancer In young Adults

- UL

upper limit

- y

years

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed on 17 December 2013.

- 2.Shi JF, Canfell K, Lew JB, Qiao YL. The burden of cervical cancer in China: synthesis of the evidence. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:641–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.zur Hausen H. Human papillomaviruses in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancer. Virology. 1991;184:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90816-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao YP, Li N, Smith JS, Qiao YL. Human papillomavirus type-distribution in the cervix of Chinese women: a meta-analysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:106–11. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Zhang X, Molijn A, Jenkins D, Shi JF, Quint W, Schmidt JE, Wang P, Liu YL, Li LK, et al. Human papillomavirus type-distribution in cervical cancer in China: the importance of HPV 16 and 18. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1705–13. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9422-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li N, Franceschi S, Howell-Jones R, Snijders PJ, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: Variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:927–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu FC, Chen W, Hu YM, Hong Y, Li J, Zhang X, Zhang YJ, Pan QJ, Zhao FH, Yu JX, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in healthy Chinese women aged 18-25 years: Results from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28897. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellsagué X, Schneider A, Kaufmann AM, Bosch FX. HPV vaccination against cervical cancer in women above 25 years of age: key considerations and current perspectives. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115(Suppl):S15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Zahaf T, Innis B, Naud P, De Carvalho NS, et al. GlaxoSmithKline HPV Vaccine Study Group Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1757–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, Naud P, Salmerón J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter DL, Kitchener HC, Castellsagué X, et al. HPV PATRICIA study group Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz TF, Spaczynski M, Schneider A, Wysocki J, Galaj A, Perona P, Poncelet S, Zahaf T, Hardt K, Descamps D, et al. HPV Study Group for Adult Women Immunogenicity and tolerability of an HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted prophylactic cervical cancer vaccine in women aged 15-55 years. Vaccine. 2009;27:581–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen C, Petaja T, Strauss G, Rumke HC, Poder A, Richardus JH, Spiessens B, Descamps D, Hardt K, Lehtinen M, et al. HPV Vaccine Adolescent Study Investigators Network Immunization of early adolescent females with human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine containing AS04 adjuvant. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:564–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Descamps D, Hardt K, Spiessens B, Izurieta P, Verstraeten T, Breuer T, Dubin G. Safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine for cervical cancer prevention: a pooled analysis of 11 clinical trials. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:332–40. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.5.7211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanley M, Lowy DR, Frazer I. Chapter 12: Prophylactic HPV vaccines: underlying mechanisms. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S3–, 106-13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day PM, Kines RC, Thompson CD, Jagu S, Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. In vivo mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against HPV infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:260–70. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dessy FJ, Giannini SL, Bougelet CA, Kemp TJ, David MP, Poncelet SM, Pinto LA, Wettendorff MA. Correlation between direct ELISA, single epitope-based inhibition ELISA and pseudovirion-based neutralization assay for measuring anti-HPV-16 and anti-HPV-18 antibody response after vaccination with the AS04-adjuvanted HPV-16/18 cervical cancer vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 2008;4:425–34. doi: 10.4161/hv.4.6.6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz TF, Kocken M, Petäjä T, Einstein MH, Spaczynski M, Louwers JA, Pedersen C, Levin M, Zahaf T, Poncelet S, et al. Correlation between levels of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16 and 18 antibodies in serum and cervicovaginal secretions in girls and women vaccinated with the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:1054–61. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.12.13399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draper E, Bissett SL, Howell-Jones R, Waight P, Soldan K, Jit M, Andrews N, Miller E, Beddows S. A randomized, observer-blinded immunogenicity trial of Cervarix(®) and Gardasil(®) Human Papillomavirus vaccines in 12-15 year old girls. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmerón J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsague X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, et al. HPV PATRICIA Study Group Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009;374:301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Wheeler CM, Jaisamrarn U, Garland SM, Castellsagué X, Skinner SR, Apter D, Naud P, Salmerón J, et al. HPV PATRICIA Study Group Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:89–99. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, Moscicki AB, Romanowski B, Roteli-Martins CM, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Costa Clemens SA, Dubin G, HPV Vaccine Study group Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1247–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romanowski B, de Borba PC, Naud PS, Roteli-Martins CM, De Carvalho NS, Teixeira JC, Aoki F, Ramjattan B, Shier RM, Somani R, et al. GlaxoSmithKline Vaccine HPV-007 Study Group Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial up to 6.4 years. Lancet. 2009;374:1975–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Carvalho N, Teixeira J, Roteli-Martins CM, Naud P, De Borba P, Zahaf T, Sanchez N, Schuind A. Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine up to 7.3 years in young adult women. Vaccine. 2010;28:6247–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roteli-Martins CM, Naud P, De Borba P, Teixeira JC, De Carvalho NS, Zahaf T, Sanchez N, Geeraerts B, Descamps D. Sustained immunogenicity and efficacy of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: up to 8.4 years of follow-up. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:390–7. doi: 10.4161/hv.18865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konno R, Tamura S, Dobbelaere K, Yoshikawa H. Efficacy of human papillomavirus type 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in Japanese women aged 20 to 25 years: final analysis of a phase 2 double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:847–55. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181da2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konno R, Dobbelaere KO, Godeaux OO, Tamura S, Yoshikawa H. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of human papillomavirus 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in Japanese women: interim analysis of a phase II, double-blind, randomized controlled trial at month 7. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:905–11. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a23c0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konno R, Tamura S, Dobbelaere K, Yoshikawa H. Efficacy of human papillomavirus 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in Japanese women aged 20 to 25 years: interim analysis of a phase 2 double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:404–10. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d373a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.GlaxoSmithKline. Study to evaluate the efficacy of the human papillomavirus vaccine in healthy adult women of 26 years of age and older. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethseda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000- [cited 2013 Dec 14]. Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00294047. NLM Identifier: NCT00294047.

- 30.Bhatla N, Suri V, Basu P, Shastri S, Datta SK, Bi D, Descamps DJ, Bock HL, Indian HPV Vaccine Study Group Immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in healthy Indian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:123–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sow PS, Watson-Jones D, Kiviat N, Changalucha J, Mbaye KD, Brown J, Bousso K, Kavishe B, Andreasen A, Toure M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomized trial in 10-25-year-old HIV-Seronegative African girls and young women. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1753–63. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petäjä T, Pedersen C, Poder A, Strauss G, Catteau G, Thomas F, Lehtinen M, Descamps D. Long-term persistence of systemic and mucosal immune response to HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in preteen/adolescent girls and young women. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2147–57. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina DM, Valencia A, de Velasquez A, Huang LM, Prymula R, García-Sicilia J, Rombo L, David MP, Descamps D, Hardt K, et al. HPV-013 Study Group Safety and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomized, controlled trial in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz TF, Huang LM, Medina DM, Valencia A, Lin TY, Behre U, Catteau G, Thomas F, Descamps D. Four-year follow-up of the immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine when administered to adolescent girls aged 10-14 years. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.David MP, Van Herck K, Hardt K, Tibaldi F, Dubin G, Descamps D, Van Damme P. Long-term persistence of anti-HPV-16 and -18 antibodies induced by vaccination with the AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: modeling of sustained antibody responses. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115(Suppl):S1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz TF, Spaczynski M, Schneider A, Wysocki J, Galaj A, Schulze K, Poncelet SM, Catteau G, Thomas F, Descamps D. Persistence of immune response to HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in women aged 15-55 years. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7:958–65. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.9.15999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coseo S, Porras C, Hildesheim A, Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Gonzalez P, Wang SS, Sherman ME, et al. Costa Rica HPV Vaccine Trial (CVT) Group Seroprevalence and correlates of human papillomavirus 16/18 seropositivity among young women in Costa Rica. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:706–14. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e1a2c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Wipf GC, Christensen ND, Lee SK, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, Galloway DA. The natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 capsid antibodies among a cohort of university women. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:927–36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiggelaar SM, Lin MJ, Viscidi RP, Ji J, Smith JS. Age-specific human papillomavirus antibody and deoxyribonucleic acid prevalence: a global review. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:110–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Huang R, Schmidt JE, Qiao YL. Epidemiological features of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection among women living in Mainland China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4015–23. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.7.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szarewski A, Poppe WA, Skinner SR, Wheeler CM, Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, et al. HPV PATRICIA Study Group Efficacy of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in women aged 15-25 years with and without serological evidence of previous exposure to HPV-16/18. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:106–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YJ, Kim KT, Kim JH, Cha SD, Kim JW, Bae DS, Nam JH, Ahn WS, Choi HS, Ng T, et al. Vaccination with a human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in Korean girls aged 10-14 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1197–204. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.8.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ngan HY, Cheung AN, Tam KF, Chan KK, Tang HW, Bi D, Descamps D, Bock HL. Human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: immunogenicity and safety in healthy Chinese women from Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:171–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Clifford GM, Touzé A, Hsu CC, de Sanjosé S, Pham TH, Nguyen TH, Matos E, Shin HR, et al. IARC HPV Prevalence Surveys Study Group Seroprevalence of antibodies against human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 in four continents: the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV Prevalence Surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2379–88. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Kang LN, Qiao YL. Review of the cervical cancer disease burden in mainland China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.