Abstract

Several pieces of experimental evidence suggest that administration of anti-β amyloid (Aβ) vaccines, passive anti-Aβ antibodies or anti-inflammatory drugs can reduce Aβ deposition as well as associated cognitive/behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer disease (AD) transgenic (Tg) mouse model and, as such, may have some efficacy in human AD patients as well. In the investigation reported here an Aβ 1–42 peptide vaccine was administered to 16-month old APP+PS1 transgenic (Tg) mice in which Aβ deposition, cognitive memory deficits as well as levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines were measured in response to the vaccination regimen. After vaccination, the anti-Aβ 1–42 antibody-producing mice demonstrated a significant reduction in the sera levels of 4 pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 α, and IL-12). Importantly, reductions in the cytokine levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were correlated with cognitive/behavioral improvement in the Tg mice. However, no differences in cerebral Aβ deposition in these mice were noted among the different control and experimental groups, i.e., Aβ 1–42 peptide vaccinated, control peptide vaccinated, or non-vaccinated mice. However, decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as improved cognitive performance were noted in mice vaccinated with the control peptide as well as those immunized with the Aβ 1-42 peptide. These findings suggest that reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in these mice may be utilized as an early biomarker for vaccination/treatment induced amelioration of cognitive deficits and are independent of Aβ deposition and, interestingly, antigen specific Aβ 1–42 vaccination. Since cytokine changes are typically related to T cell activation, the results imply that T cell regulation may have an important role in vaccination or other immunotherapeutic strategies in an AD mouse model and potentially in AD patients. Overall, these cytokine changes may serve as a predictive marker for AD development and progression as well as having potential therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, amyloid-beta (Aβ), biomarker, cytokine, immunomodulation, inflammation

Introduction

The initial observation of a potential role for inflammation in Alzheimer Disease (AD) was noted by Alois Alzheimer and was suggested by the presence of “activated” glia in specific areas of the brain.1 However, as with other aspects of AD pathology, the molecular evidence for inflammation in AD came in the 1980s when associated amyloid deposits noted in this disease were found to contain, in addition to amyloid β (Aβ) peptides, other proteins, including complement, HLA antigens, anti-chymotrypsin, and IL-1, all of which are normally secreted during inflammation and the associated acute phase response.2-10 The strongest evidence that inflammation causally contributes to AD resulted from studies in transgenic (Tg) mice carrying a mutant human amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene as well as presenilin-1 (PS-1), in which accumulation of Aβ and cognitive decline were demonstrated to be correlated with the presence of inflammation and associated cytokines and other proteins.11

In addition to its contribution to pathologic Aβ formation, inflammation may also affect brain function and cognition in other ways. For example, active vaccination, through administration of aggregated or soluble Aβ peptides, has been demonstrated to reduce toxic brain Aβ levels and to alleviate cognitive decline in several Tg mouse models of AD, but more recently has also been demonstrated to induce vascular inflammation.12,13 Indeed, a phase II clinical trial (AN1792) using wild type Aβ 1–4214 was not successfully completed due to the development of aseptic meningoencephalitis in a small subset of patients.15-17 Initial reports measuring pro-inflammatory cytokine production in AD mouse models (i.e., APP/PS-1) after active Aβ vaccination with and without adjuvant use suggest that, for the most part, the brain tissue inflammation was caused by the adjuvants utilized in the vaccine preparation.15 As well, several reports have been published indicating Aβ mediated increases in several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including those measured in this study.18-20 An adverse T-cell reaction was also considered to be a major contributor to the adverse effects noted in the AD clinical vaccine trial.8,10,11,17,21,22

In the present study, we analyzed the generation of some pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as Aβ antibodies after active Aβ 1–42 peptide immunization of double Tg APP/PS-1 mice in order to determine whether there is a relationship between general immune system activation and cognitive performance. Our data suggest that cytokine modulation might be, at least, in part, a marker of treatment/vaccine mediated cognitive benefits. Further, the cytokine modulation may also have a more direct role in mediating the cognitive benefits in the mouse model and may have applicability to human AD. Interestingly, the findings of a correlation between the decrease in several pro-inflammatory cytokines and cognitive benefits in the mouse model appeared to be independent of either amyloid deposition or specific Aβ 1–42 peptide immunization. As such, it is reasoned that these observations are provocative and warrant further investigation.

Results

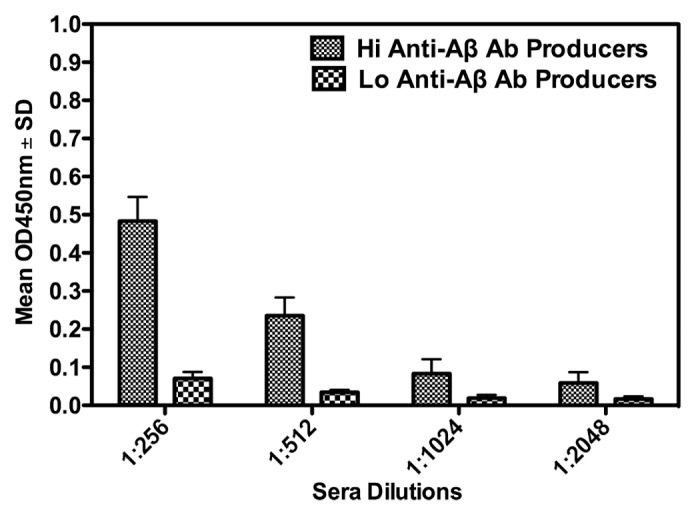

A number of mice in this study produced anti-Aβ antibodies following the first vaccination, with a significant increase in levels of antibody following the second vaccination. After 2 vaccinations with the Aβ 1–42 peptide, 75% of the mice demonstrated a significant (i.e., OD450nm absorbance values 3 times higher than that of the negative control) antibody response. Antibody titers varied but attained a level higher than 2048 in some of the mice. Figure 1 graphically summarizes the antibody binding values and titer estimates, as determined by ELISA. These values are presented in the graph as hi (i.e., a OD450nm value greater than 0.2 at a 1:256 serum dilution) or lo (i.e., a OD450nm value lower than 0.2 at a 1:256 serum dilution) binders. The relevance of the distinction between the hi and lo anti-Aβ antibody is described later in this report.

Figure 1. Anti-Aβ antibody responses in APP-PS1 Tg mice following 2 vaccinations with an Aβ 1–42 peptide. The graph shows OD450nm values ± SD, indicative of levels of specific anti-Aβ peptide antibodies after vaccination, measured by an ELISA as described in the Materials and Methods section. Vaccinated mice are divided into high (Hi Anti-Aβ Ab Producer) or low (Lo Anti-Aβ Ab Producer) specific antibody producing groups.

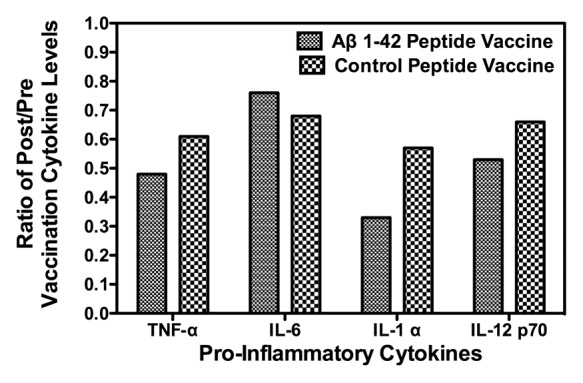

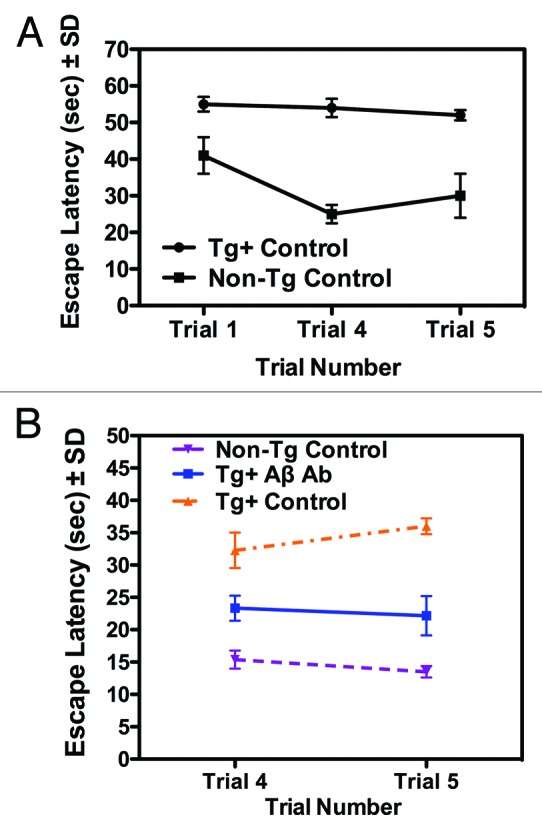

Immunomodulatory cytokines are frequently measured to evaluate immune responses to vaccines since activated T cells release these immune mediators. As well, inflammation mediated, in part, by pro-inflammatory cytokines is hypothesized to have a role in AD pathogenesis. Therefore, we measured the levels (i.e., µg/mL) of several pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 α, and IL-12) in the sera of Tg mice before and after vaccination with the Aβ 1–42 or control peptide. As alluded to in the Introduction, levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 α were measured in this vaccine study based on previously published reports on stimulation of these molecules by Aβ. Levels of IL-12 were measured as well, based in part, on a recent study indicating that inhibition of IL-12 signaling decreases AD-like pathology and ameliorates memory decline.20 The relationship between the concentrations of cytokines measured to antibody levels, amyloid deposition, and cognitive deficits in APP-PS1 Tg mice was evaluated. Results of these analyses are summarized in Figure 2 and are presented as ratios of post to pre vaccination concentrations of the 4 pro-inflammatory cytokines listed above. A ratio of 1.0 indicates no change in pre to post vaccination concentrations of the cytokines, while a value of less than or greater than 1.0 indicates a decrease or increase respectively in the concentration of the cytokines after vaccination. The results indicate a significant decrease, after vaccination with the Aβ 1–42 peptide, in the levels of all 4 of pro-inflammatory cytokines measured, as evidenced by the post/pre vaccination cytokine level ratios , which ranged from 0.3 to 0.76. Interestingly, vaccination with the control peptide resulted in a decrease in sera levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines as suggested by the post to pre vaccination level ratios having a range from approximately 0.6 to 0.7. These results suggest that non-specific active vaccination or immunotherapeutics might modify cytokine profiles that may mediate or correlate to a beneficial biological effect. The data presented in Figure 3A and B documents the ability of vaccination with the Aβ 1–42 to mediate amelioration of learning deficits characteristic of the APP-PS1 Tg mice. In Figure 3A escape latency values, recorded as seconds (s), as measured by RAWM testing, are presented. Trial 1 measured the initial naïve escape latency values. The escape latency measurements for this trial were 40 and 55 s for the non-Tg control and Tg non-vaccinated control mice respectively. Results from Trials 4 and 5 indicated that the non-Tg control mice “learned and remembered” from their Trial 1 evaluation and performed better on the RAWM testing, as evidenced by the lower escape latency values. As well, the non-vaccinated Tg control mice failed to demonstrate improvement in the escape latency values from the RAWM testing, re-confirming the learning deficits in these APP-PS1 Tg mice. Figure 3B summarizes the RAWM test results in the anti-Aβ antibody producing vaccinated mice, compared to Tg and non-Tg control mice. In this analysis naïve Trial 1 escape latency values (not shown) were between 40 and 50 s for the different mouse experimental and control groups. In Trial 4 and 5 testing, escape latency values were intermediate (i.e., approximately 22 s) in the Tg anti-Aβ antibody producers compared to the Tg controls (approximately 30–35 s) and non-Tg controls (i.e., approximately 15 s). This result suggests an ameliorative effect of vaccination on cognitive deficits in these AD Tg mice.

Figure 2. Effect of Aβ 1–42 and control peptide vaccination of APP-PS1 Tg mice on pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. Sera collected from APP-PS1 Tg mice before and after vaccination with either Aβ 1–42 or control peptide were analyzed for levels (μg/mL) of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 α, and IL-12. Data are represented graphically as ratios of post to pre vaccination concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokines. A value of 1.0 indicates no change in pre to post vaccination levels of the cytokines, while a value less than 1.0 indicates a decrease in cytokine levels after vaccination.

Figure 3. Behavioral analysis of pre and post Aβ 1–42 peptide vaccinated mice. Working memory performance (escape latency values ± SD), measured by RAWM testing of (A) Tg and non-Tg mice during the 3 d prior to the commencement of the vaccination regimen are shown in Trials 1 (naïve), 4, and 5. Likewise in (B) working memory values for non-Tg control, Tg+ Aβ Ab (Tg mice demonstrating anti-Aβ antibodies) and Tg control mice 3 d following the Aβ vaccination regimen are indicated in Trials 4 and 5. Escape latency values for naïve testing (Trial 1) of the mice ranged between 40–45 s (data not shown).

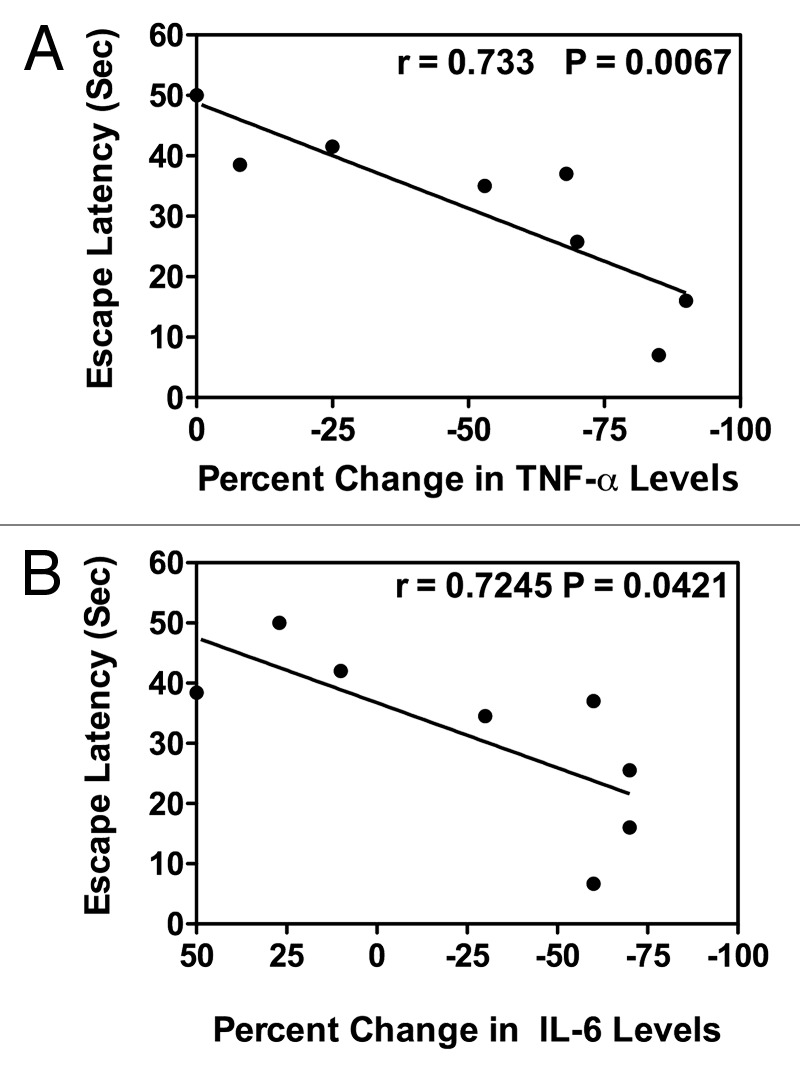

After confirming the biological effects of vaccination on cognitive parameters in the Tg mice, a further analysis of a possible correlation between cytokine levels, vaccination, and cognition/memory parameters in these mice was performed. Figure 4A and B summarizes this analysis in which escape latency values are graphed vs. pre to post vaccination changes in TNF- α and IL-6 levels respectively in the vaccinated mice. For this analysis, 4 antibody-producing mice from the Aβ 1–42 peptide vaccinated and 4 from the control peptide vaccinated groups were utilized. Post vaccination sera IL-6 and TNF- α levels were measured in each mouse. In addition, each mouse was subjected to RAWM testing for assessment of behavioral deficits. In the graphs presented each of the points represents the correlative values (escape latency vs. pre to post vaccination changes in levels of TNF-α and IL-6) for each of the mice. Interestingly, the first 4 points (from left to right) on the graph for (A) TNF-α and (B) IL-6 represents an equal mix of Aβ 1-42 and control peptide vaccinated mice, as does the remaining 4 points on the graphs. In fact, for some of the mice IL-6 levels remained the same or increased after vaccination, although the majority of the mice had decreased levels of IL-6 after vaccination. The conclusion from the results summarized in the 2 graphs is that there is a significant correlation (r value approximately 0.73) between escape latency tested in the RAWM analysis and levels of these 2 pro-inflammatory cytokines with latency values, measured in s, decreasing with a concomitant lowering of the cytokine levels.

Figure 4. Correlation between pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and cognitive behavioral improvement in Aβ 1–42 or control peptide vaccinated APP-PS1 Tg mice. Mice vaccinated with the Aβ or control peptide, as described in the Materials and Methods, were subjected to RAWM testing. Results of the RAWM testing, expressed as escape latency (sec), are graphed vs. percent change in levels of (A) TNF- α or (B) IL-6 in post-vaccination compared with pre-vaccination values; r, correlation of coefficient; P, P value with ≤0.5 being significant.

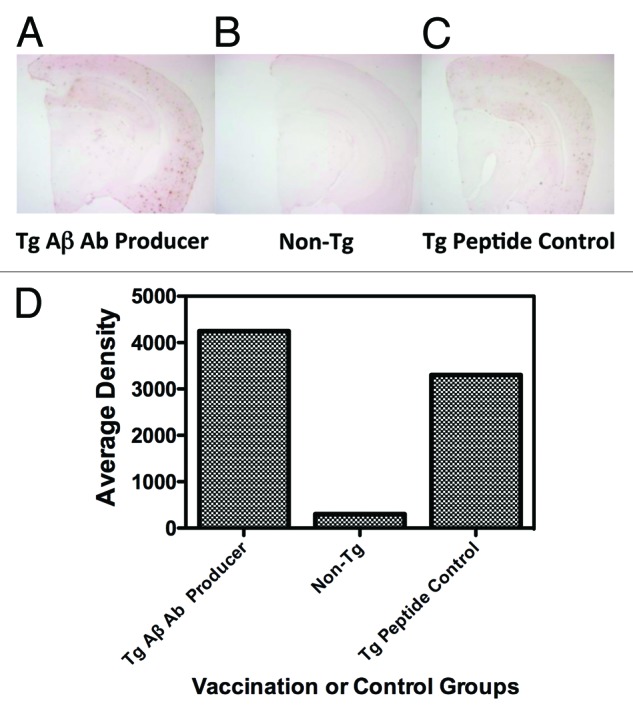

Figure 5 summarizes the measurement of brain Aβ levels in representative mice from Aβ 1-42 and control vaccinated Tg mice, as well as from a non-Tg control mouse. For these analyses, mice were sacrificed after vaccination followed by removal and sectioning of the brain with subsequent staining of the brain slices with the anti-Aβ specific monoclonal antibody 6E10. Panels a, b, and c indicate, respectively, 6E10 antibody stained brain sections from an antibody producing Aβ 1-42 vaccinated Tg mouse (Tg Aβ Ab Producer), a non-Tg control (Non-Tg), and a control peptide vaccinated Tg mouse (Tg Peptide Control). Panel d indicates graphically the densitometric values for Aβ staining in the 3 different representative mice. The conclusion from the analysis of this experiment is that both qualitatively and quantitatively there appeared to be no significant difference in Aβ staining between the Aβ peptide and control peptide vaccinated mice. As well, there was no difference between the 2 vaccinated Tg mice and non-vaccinated Tg controls (data not shown). Therefore, it could be argued that even though there was apparent behavioral improvement in the RAWM test, which was correlated with a decrease in the levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, this amelioration of cognitive deficits was independent of any measurable decrease in Aβ deposition in the brains of the vaccinated Tg mice.

Figure 5. Quantitation of Aβ in brain sections of Aβ 1–42 and control peptide vaccinated APP-PS1 Tg mice. Brain sections from representative mice stained with the anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody 6E10: (A) Tg Aβ Ab (antibody) producer, (B) Non-Tg control, and (C) Tg peptide control, as described in the Materials and Methods section are shown. Panel (D) indicates Aβ quantitation, expressed as Average Density, from the 6E10 antibody stained brain sections, indicated above.

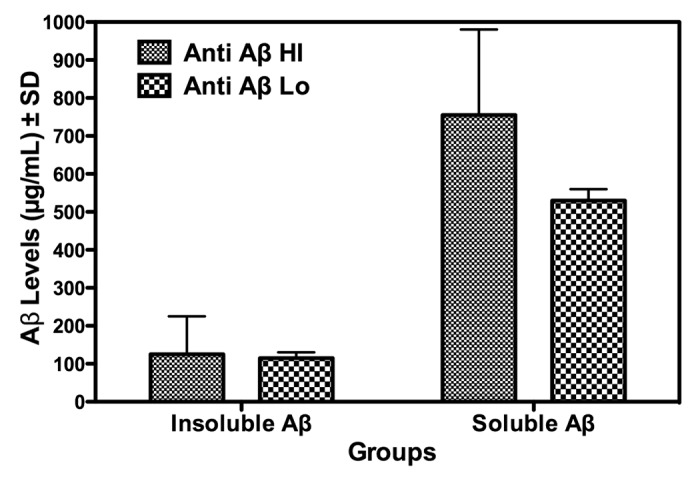

Likewise, Figure 6 summarizes results of an analysis of brain homogenates, prepared as described in the Materials and Methods, for levels of soluble and insoluble Aβ induced following vaccination. These data are presented as a function of whether the brain samples were from hi or lo anti-Aβ antibody producing mice. The graph of the data indicates no significant difference between the hi or lo antibody producers in levels of either insoluble or soluble Aβ. For the insoluble form of Aβ, which is thought to be associated with AD pathogenicity, the levels in the hi vs. lo anti-Aβ antibody producers are approximately equivalent, i.e., 100 µg/mL.

Figure 6. Total brain levels of soluble or insoluble Aβ in Aβ 1−42 peptide vaccinated APP-PS1 Tg mice as a function of Hi or Lo anti-Aβ 1–42 antibody production. After 2 vaccinations, mice, divided into Hi and Lo anti-Aβ 1–42antibody producers, were sacrificed and brain levels (expressed as µg/mL ± SD brain homogenate) of soluble or insoluble Aβ were measured as described in the Materials and Methods section and presented as OD450nm values.

Discussion

The development of an effective vaccine against AD continues, irrespective of some setbacks, to be a goal for research aimed at the prevention and/or treatment of this serious neurodegenerative disease. Recent efforts on AD vaccine development include the use of Aβ peptides with T cell epitope deletions/mutations, DNA vaccines, short Aβ fragments chemically linked to other epitopes, as well as varying routes for vaccine delivery.23-28 All of these strategies have demonstrated to be effective, to varying degrees, in AD Tg mouse models, which express Aβ in the brain as well as demonstrate some of the manifestations of clinical human AD. In order to evaluate the potential utility of these approaches the establishment of an “early” endpoint will be beneficial since such a parameter could direct or modify continuing treatment strategies. In the current study, an Aβ1–42 peptide was used as a vaccine in an APP/PS1 Tg mouse model for AD. The post-vaccination antibody response was evaluated by ELISA, following the second Aβ peptide immunization. Anti-Aβ antibody levels had been suggested, based on experimental evidence, to be an effective indicator for measuring and predicting improvement of behavioral deficits in the AD mouse model.12,13 However, clinical evaluation of the Aβ peptide vaccine (human trial AN 1792)14 was discontinued due to the development of neuroinflammation (i.e., aseptic meningoencephalitis) in some of the human subjects.29 This implies that the measurement of early inflammation markers in Aβ-vaccinees (i.e., mice or humans), particularly those linked to T cell responses, could predict the development of potential therapeutic efficacy as well as possible adverse effects. Specifically, measurement of cytokines during the vaccination regimens may be good predictive markers to guide the development of safe and efficacious immunotherapies. Following detailed sequence analysis and appropriate vaccination studies, it has been determined that the Aβ 1–42 peptide possesses a strong T-cell as well as B cell epitope.30,31 As such, it was hypothesized and demonstrated that there would be significant changes in the levels of some cytokines during and after the Aβ peptide vaccination regimen. Others have demonstrated that production of anti-Aβ antibodies is correlated with the reduction of cerebral amyloid burden in AD transgenic mice, concurrent with cognitive improvement13,32-34 Therefore, one might have expected to note correlations between plasma anti-Aβ antibody and cytokine levels as well. However, no such correlations were evident. In fact, as well, there was no apparent correlation between plasma antibody levels and cognitive performance in Aβ transgenic mice.35 The current data demonstrate the significance of plasma cytokine reduction following immunotherapy. Although these data, in general, indicate that anti-Aβ antibody producing mice have a better behavioral performance profile compared to non-antibody producers there was no clear plaque reduction nor a decrease in either soluble or insoluble Aβ levels in the brains of antibody producers compared to non-antibody producers.

Interestingly, all anti-Aβ antibody-producing mice demonstrate greater reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, with this decrease correlated with cognitive improvement. However, plasma antibody levels did not correlate with the extent of cognitive improvement. These data imply that if inflammation interferes with and decreases cognitive performance the subsequent alleviation of inflammatory responses will protect against or perhaps reverse cognitive behavioral deficits. As indicated, potential inflammation can be assessed by measuring changes in levels of cytokines during early stages of pathology. Therefore, successful suppression of these inflammatory responses, such as those mediated by T cell activation, may benefit Alzheimer patients and provide a potential avenue for AD treatment.

Several treatment strategies against AD have been evaluated in Tg mouse models for this neurodegenerative disease, usually with the intention of reducing Aβ load in the brain. However, analyses of the effects of cognitive stimulation through administration of caffeine, EGCG (a primary component of green tea), or the phosphodiesterase E4 inhibitor rolipram to AD Tg mice or exposure to environmental enrichment indicate that, similar to what was observed in the study presented here, cognitive parameters can be improved without significantly affecting total Aβ load.36-39

The results, then, of the study summarized in this report indicate that changes in the levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, induced by active or passive vaccine based approaches against AD, may be an early correlative indicator of cognition and memory in Tg mice as well as potentially in human patients. As such, since cytokine production is typically mediated through T cell activation, the regulation of T cells and associated immunomodulatory molecules may influence and be indicative of beneficial effects of immune based strategies against AD. Therefore, redirection of immunity from pro-inflammatory activity, indicative of T cell activation, toward anti-inflammatory responses that are suggestive of antibody-based immunity may be a desirable endpoint for immunoprophylaxis or immunotherapeutic strategies against AD.

It is acknowledged that there are several limitations to the study presented in this report. Firstly, the number of mice used in control and experimental groups are relatively small. Logistical as well as breeding and health issues for the Tg mouse strain limited the number of mice available for use in this study. Future experiments, building on the initial important observations made here, will increase the number of Tg mice in the control and experimental groups. It is argued, however, that although the number of mice used here is small, the observations made are novel and provocative and merit further investigation. As well, in the discussion of the relevance of these findings it is noted that statements made concerning brain inflammation and T cell responses, relative to the observations and implications of cytokine changes associated with vaccination, are hypothetical and not proven based on the data presented. To that end, future studies will directly address and measure, in response to the vaccination regimens, parameters such as T cell activation and regulatory T cell responses.

In conclusion, further evaluation of cytokine production and the significance of such responses, in the context of specific and non-specific vaccination strategies against AD, is warranted.

Materials and Methods

General Protocol

Fifteen month old double Tg mice (B6C3/Tg(APP695)85Dbo/Tg(PSEN1)85Dbo) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. The mice were housed individually in standard vivarium cages at the University of South Florida (USF) animal facility. All animal work was performed as per federal guidelines and approved by the USF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Vaccination of the animals in this study was initiated at 16 mo of age.

The anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody (6E10) was purchased from Signet Laboratories, and the Aβ 1–42 peptide was obtained from Synpep. A control peptide vaccine (from the HIV transmembrane envelope glycoprotein gp41), of similar length to the Aβ 1-42 peptide, was also used in the experiments. This control peptide was synthesized at the USF peptide core facility. Peptides prepared for vaccination were reconstituted to 10 mg/mL in DMSO and further diluted to 2 mg/mL with phosphate buffered saline. Peptides were then mixed with a Monophophoryl Lipid A (MPL) adjuvant purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., which was then subsequently used as the vaccine preparation.

Behavioral testing for measurement of cognitive learning deficits

Before the initiation of the vaccination regimen, the working memory of all mice was measured over a 12-d period using the radial arm water maze (RAWM) test, in order to establish the baseline memory parameters/levels of each mouse before treatment. For post-treatment evaluation mice were tested over a period of 14 d beginning 2 wk after the final vaccination. The RAWM test was performed as previously described.40 Briefly, for RAWM testing, an aluminum insert was placed in a 100 cm diameter circular pool to create 6 radially distributed swim arms. Each mouse was evaluated in five 1-min trials per day, which include 4 consecutive acquisition trials (T4) and a 30 min delayed retention trial (T5), used as indices of working memory. On any given day of testing, a submerged clear platform was placed at the end of 1 of the 6 swim arms. The platform location was changed daily to a different arm in a random pattern. On each day, different start arms for each of the 5 daily trials were selected. For any given trial, the mouse was placed into that trial’s start arm and was permitted 60 s to find the platform. Each time the mouse entered a non-platform containing arm, it was gently pulled back into the start arm. If the mouse did not find the platform within a 60 s trial, it was guided to the platform and allowed a 30 s rest. For each daily trial, the escape latency (i.e., the time interval in seconds that it took the mouse to find the platform) was recorded. For statistical analysis of RAWM escape latencies, Trial 1 (T1; naïve trial for any given day), Trial 4, and Trial 5 (T4 and T5) were compared over the last 3 d of both pre- and post-vaccination testing using a one-way ANOVA analysis. Also, T5 data for all days of pre- and post-vaccination testing was averaged for each mouse in each of the treatment groups followed by subsequent comparison of the different groups.

Vaccination groups

A total of 15 mice, (10 Tg mice and 5 non-Tg littermates) were used in this study. The 10 gender-balanced Tg mice were divided into 2 groups designated the Aβ1–42 vaccine group (n = 5) and the control peptide vaccine group (n = 5). A separate group of non-Tg mice were treated with 1X PBS (also containing 10% DMSO). All Tg mice were immunized either with peptide mixed with MPL adjuvant ,which is a detoxified form of Salmonella lipopolysaccharide that induces Th1 T cells, or injected with 1X PBS containing only MPL adjuvant. The MPL adjuvant was selected due to the reported safety of this agent. Specifically, it is only mildly inflammatory, a characteristic that is believed to be important to enhance vaccination efficacy. In addition, it has recently been suggested that MPL may have the ability to lessen brain pathologic inflammation that is typically noted in the APP/PS1 Tg mouse strain. Specifically, Michaud et. al. reported that MPL lessens AD-like pathology through mediating a decrease in Aβ load by virtue of the phagocytic activity of innate immune cells.41,42 Following the pre-treatment behavioral testing, using the RAWM, an initial subcutaneous vaccine (100 μg peptide in 100 μL adjuvant) was administered, followed by 2 subsequent booster vaccinations at 2-wk intervals. Two weeks after the last vaccination (i.e., 1½ months after the initial vaccination), mice were further tested in the RAWM. In addition, before the first vaccination and 10 d after each subsequent vaccination, mice were bled by submandibular phlebotomy into EDTA tubes. Plasma was separated, centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 min and frozen at −80 °C. For the statistical analysis of their cognitive performance, Tg mice were grouped based on their relative Aβ antibody titers into “hi” or “lo” titer groups. Animals were euthanatized via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital at 17 mo of age followed by intracardiac perfusion with PBS. Brains were then excised and divided mid-sagitally into 2 sections. Half of the brain was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, followed by graded sucrose solutions. Subsequently, 25 μm coronal sections were collected using a cryostat. Sections were stored in PBS for later histologic staining and brain sections were processed for immunostaining with the 6E10 anti-Aβ 1–42 antibody. The other half of each brain was later utilized for cytokine and soluble/insoluble Aβ analyses.

Anti-Aβ Antibody titer determination

Ten days after each Aβ 1–42 peptide vaccination, sera anti-Aβ antibody levels were determined by ELISA analysis, as described previously.43 Briefly, 96 well plates were coated with 50 μL of the Aβ 1–42 peptide (at 10 μg/mL) suspended in carbonate-bicarbonate (CBC) buffer. A CBC buffer bound plate was also used in order to measure control background binding. Both the Aβ 1-42 peptide experimental and CBC bound control plates were incubated at 4 °C overnight. After 5 washes, plates were blocked with blocking buffer (1XPBS containing 1.5% BSA) followed by extensive washing. Sera samples, collected at each post-vaccination time point, were then diluted serially (beginning with a dilution of 1:50) in blocking buffer, and subsequently added to both the Aβ 1-42 peptide as well as CBC coated plates. Plates were then incubated for 1 h. at 37 °C and washed. An HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma Aldrich) was then loaded into each well at a 1:5000 dilution and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, and washed as indicated above. Finally, TMB peroxidase substrate was dissolved in buffer and 100 μL was added to each well, developed, and read in a spectrophotometer at 450 nm. Samples with OD450nm readings 3 times higher than controls were considered as positive, with the highest dilution being designated as the endpoint titer. Statistical evaluation of the results were initially performed using a one-way ANOVA involving all groups. This was then followed by a post hoc pair-by-pair analysis of group differences, using the Fisher LSD test.

Aβ immunostaining of brain with 6E10 monoclonal antibody

Paraformaldehyde-fixed brains were sectioned into 25 μm thick slices and quantification of diffuse Aβ (measured by immunostaining with the 6E10 antibody) was determined as previously described.44 The 6E10 monoclonal antibody is reactive against amino acids 1–16 of β amyloid and typically binds to the abnormally processed isoforms as well as the precursor forms. Images were captured using a Nikon 2000U fluorescence microscope fitted with a Spot video capture system. Images of 5 coronal sections (through the thalamus) from each mouse were analyzed using the NIH ImageJ system with visible light. Stained sections were analyzed via Alpha Innotech Corporation’s AlphaEase™ FC software. Using spot densitometry algorithms, the average density of the collective spots of a standardized rectangular area for each brain section was calculated and recorded.

Cytokine expression detection

Cytokine expression profiles were determined for both pre- and post-second vaccination sera samples using Bio-Rad Bio-Plex kits (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Because of the naturally occurring variability of cytokine levels, optical density readings for each cytokine were normalized using a method of comparing ratios of post- to pre-treatment values for each animal. Briefly, the data for individual animals from post-vaccination expression profiles was divided by the parallel data from the pre-vaccination expression profiles. The results of this analysis are presented as either a decrease, increase, or no change in post to pre vaccination cytokine levels indicated by values of either less than 1.0 or equal to 1.0 respectively.

Measurement of soluble and insoluble forms of Aβ

Hippocampal brain tissue was collected after sacrifice of the mice, homogenized with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer followed by protein determination and storage at −80 °C. For the analysis of Aβ levels, samples were thawed with one-half of the sample further suspended in RIPA buffer, for soluble Aβ determination. Likewise, the other half of the sample was suspended in a 2-fold volume of formic acid, sonicated and centrifuged to obtain the supernatant to be used for insoluble Aβ determination.45 Both insoluble and soluble forms of Aβ 1–40 and Aβ 1–42 were measured by an ELISA.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Huntington Potter, Peter Neame, Gary Arendash, and Inge Wefes for constructive comments on the study and manuscript as well as Alexander Dickson, Daniel Shippy, Jennifer R Cracchiolo for their varied assistance. This work was supported by funds from the State of Florida.

References

- 1.Alois A. Uber Eine Eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde. Zeitschrift Fuer Psychitrie (Germany) 1907; 64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eikelenboom P, Stam FC. Immunoglobulins and complement factors in senile plaques. An immunoperoxidase study. Acta Neuropathol. 1982;57:239–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00685397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers J, Luber-Narod J, Styren SD, Civin WH. Expression of immune system-associated antigens by cells of the human central nervous system: relationship to the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9:339–49. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(88)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham WM, Sielczak MW, Wanner A, Perruchoud AP, Blinder L, Stevenson JS, Ahmed A, Yerger LD. Cellular markers of inflammation in the airways of allergic sheep with and without allergen-induced late responses. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:1565–71. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.6.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin WS, Stanley LC, Ling C, White L, MacLeod V, Perrot LJ, White CL, 3rd, Araoz C. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7611–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheng JG, Mrak RE, Griffin WS. Microglial interleukin-1 alpha expression in brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with neuritic plaque distribution. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1995;21:290–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1995.tb01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das S, Potter H. Expression of the Alzheimer amyloid-promoting factor antichymotrypsin is induced in human astrocytes by IL-1. Neuron. 1995;14:447–56. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suo Z, Tan J, Placzek A, Crawford F, Fang C, Mullan M. Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptides induce inflammatory cascade in human vascular cells: the roles of cytokines and CD40. Brain Res. 1998;807:110–7. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00780-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson M, Husmark J, Björkman U, Ericson LE. Cytokines and thyroid epithelial integrity: interleukin-1alpha induces dissociation of the junctional complex and paracellular leakage in filter-cultured human thyrocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:945–52. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter H, Wefes IM, Nilsson LN. The inflammation-induced pathological chaperones ACT and apo-E are necessary catalysts of Alzheimer amyloid formation. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:923–30. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel NS, Paris D, Mathura V, Quadros AN, Crawford FC, Mullan MJ. Inflammatory cytokine levels correlate with amyloid load in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, Schmidt SD, Chishti MA, Horne P, Heslin D, French J, et al. A beta peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:979–82. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, Ugen KE, Dickey C, Hardy J, Duff K, Jantzen P, DiCarlo G, Wilcock D, et al. A beta peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:982–5. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thatte U. AN-1792 (Elan) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;2:663–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birmingham K, Frantz S. Set back to Alzheimer vaccine studies. Nat Med. 2002;8:199–200. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-199b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews PM, Nixon RA. Setback for an Alzheimer’s disease vaccine: lessons learned. Neurology. 2003;61:7–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.61.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, Laurent B, Puel M, Kirby LC, Jouanny P, Dubois B, Eisner L, Flitman S, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology. 2003;61:46–54. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000073623.84147.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong Y. Effect of a carboxy-terminal fragment of the Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein on expression of proinflammatory cytokines in rat glial cells. Life Sci. 1997;61:2323–33. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(97)00936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGeer EG, McGeer PL. The role of the immune system in neurodegenerative disorders. Mov Disord. 1997;12:855–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vom Berg J, Prokop S, Miller KR, Obst J, Kälin RE, Lopategui-Cabezas I, Wegner A, Mair F, Schipke CG, Peters O, et al. Inhibition of IL-12/IL-23 signaling reduces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive decline. Nat Med. 2012;18:1812–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sastre M, Klockgether T, Heneka MT. Contribution of inflammatory processes to Alzheimer’s disease: molecular mechanisms. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2006;24:167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrer I, Boada Rovira M, Sánchez Guerra ML, Rey MJ, Costa-Jussá F. Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HD, Cao Y, Kong FK, Van Kampen KR, Lewis TL, Ma Z, Tang DC, Fukuchi K. Induction of a Th2 immune response by co-administration of recombinant adenovirus vectors encoding amyloid beta-protein and GM-CSF. Vaccine. 2005;23:2977–86. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier M, Seabrook TJ, Lazo ND, Jiang L, Das P, Janus C, Lemere CA. Short amyloid-beta (Abeta) immunogens reduce cerebral Abeta load and learning deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model in the absence of an Abeta-specific cellular immune response. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4717–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0381-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okura Y, Miyakoshi A, Kohyama K, Park IK, Staufenbiel M, Matsumoto Y. Nonviral Abeta DNA vaccine therapy against Alzheimer’s disease: long-term effects and safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9619–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600966103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seabrook TJ, Thomas K, Jiang L, Bloom J, Spooner E, Maier M, et al. Dendrimeric Abeta1-15 is an effective immunogen in wildtype and APP-tg mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:813–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolic WV, Bai Y, Obregon D, Hou H, Mori T, Zeng J, Ehrhart J, Shytle RD, Giunta B, Morgan D, et al. Transcutaneous beta-amyloid immunization reduces cerebral beta-amyloid deposits without T cell infiltration and microhemorrhage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609377104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DaSilva KA, Brown ME, McLaurin J. Reduced oligomeric and vascular amyloid-beta following immunization of TgCRND8 mice with an Alzheimer’s DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:1365–76. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pride M, Seubert P, Grundman M, Hagen M, Eldridge J, Black RS. Progress in the active immunotherapeutic approach to Alzheimer’s disease: clinical investigations into AN1792-associated meningoencephalitis. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:194–6. doi: 10.1159/000113700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutzler MA, Cao C, Bai Y, Dong H, Choe PY, Saulino V, McLaughlin L, Whelan A, Choo AY, Weiner DB, et al. Mapping of immune responses following wild-type and mutant ABeta42 plasmid or peptide vaccination in different mouse haplotypes and HLA Class II transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2006;24:4630–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian S, D’Souza R, Divya Shree AN. Identification and mapping of linear antigenic determinants of human amyloid ß(1-42) peptide. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2012;33:26–34. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2011.591477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6:916–9. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcock DM, DiCarlo G, Henderson D, Jackson J, Clarke K, Ugen KE, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Intracranially administered anti-Abeta antibodies reduce beta-amyloid deposition by mechanisms both independent of and associated with microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3745–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03745.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Fan L, Xu D, Wen Z, Yu R, Ma Q. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2012;44:807–14. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gms065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Austin L, Arendash GW, Gordon MN, Diamond DM, DiCarlo G, Dickey C, Ugen K, Morgan D. Short-term beta-amyloid vaccinations do not improve cognitive performance in cognitively impaired APP + PS1 mice. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:478–84. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arendash GW, Schleif W, Rezai-Zadeh K, Jackson EK, Zacharia LC, Cracchiolo JR, Shippy D, Tan J. Caffeine protects Alzheimer’s mice against cognitive impairment and reduces brain beta-amyloid production. Neuroscience. 2006;142:941–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa DA, Cracchiolo JR, Bachstetter AD, Hughes TF, Bales KR, Paul SM, et al. Enrichment improves cognition in AD mice by amyloid-related and unrelated mechanisms. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:831–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rezai-Zadeh K, Shytle D, Sun N, Mori T, Hou H, Jeanniton D, Ehrhart J, Townsend K, Zeng J, Morgan D, et al. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloidosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8807–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1521-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutten K, Prickaerts J, Blokland A. Rolipram reverses scopolamine-induced and time-dependent memory deficits in object recognition by different mechanisms of action. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;85:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arendash WG, Sanchez-Ramos JTM, Takashi, Mamcarz M, Runfeldt M, Wang L, Zhang G. Electromagnetic Field Treatment Protects Against and Reverses Cognitive Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:191–210. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michaud JP, Hallé M, Lampron A, Thériault P, Préfontaine P, Filali M, Tribout-Jover P, Lanteigne AM, Jodoin R, Cluff C, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 stimulation with the detoxified ligand monophosphoryl lipid A improves Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1941–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215165110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, Gaudin C, Peyrot C, Vellas B, Cesari M, Nourhashemi F. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:877–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao C, Lin X, Wahi MM, Jackson EA, Potter H., Jr. Successful adjuvant-free vaccination of BALB/c mice with mutated amyloid beta peptides. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa DA, Nilsson LN, Bales KR, Paul SM, Potter H. Apolipoprotein is required for the formation of filamentous amyloid, but not for amorphous Abeta deposition, in an AbetaPP/PS double transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:509–14. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore BD, Chakrabarty P, Levites Y, Kukar TL, Baine AM, Moroni T, Ladd TB, Das P, Dickson DW, Golde TE. Overlapping profiles of Aβ peptides in the Alzheimer’s disease and pathological aging brains. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4:18. doi: 10.1186/alzrt121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]