Abstract

Background Literature on health and access to care of undocumented migrants in the European Union (EU) is limited and heterogeneous in focus and quality. Authors conducted a scoping review to identify the extent, nature and distribution of existing primary research (1990–2012), thus clarifying what is known, key gaps, and potential next steps.

Methods Authors used Arksey and O’Malley’s six-stage scoping framework, with Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s revisions, to review identified sources. Findings were summarized thematically: (i) physical, mental and social health issues, (ii) access and barriers to care, (iii) vulnerable groups and (iv) policy and rights.

Results Fifty-four sources were included of 598 identified, with 93% (50/54) published during 2005–2012. EU member states from Eastern Europe were under-represented, particularly in single-country studies. Most study designs (52%) were qualitative. Sampling descriptions were generally poor, and sampling purposeful, with only four studies using any randomization. Demographic descriptions were far from uniform and only two studies focused on undocumented children and youth. Most (80%) included findings on health-care access, with obstacles reported at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Major access barriers included fear, lack of awareness of rights, socioeconomics. Mental disorders appeared widespread, while obstetric needs and injuries were key reasons for seeking care. Pregnant women, children and detainees appeared most vulnerable. While EU policy supports health-care access for undocumented migrants, practices remain haphazard, with studies reporting differing interpretation and implementation of rights at regional, institutional and individual levels.

Conclusions This scoping review is an initial attempt to describe available primary evidence on health and access to care for undocumented migrants in the European Union. It underlines the need for more and better-quality research, increased co-operation between gatekeepers, providers, researchers and policy makers, and reduced ambiguities in health-care rights and obligations for undocumented migrants.

Keywords: Undocumented migrants, health, access to care, European Union, review

Background

Case reports from support organizations suggest high infection rates, poor disease prevention, and delays in health-care access among undocumented migrants living in the 27 member states of the European Union (EU27), reflecting both increased health risks of undocumented migrants and barriers to health-care access (Chauvin et al. 2009; Karl-Trummer et al. 2009; MDM 2009). Mladovsky and others associate these increased risks with a lack of knowledge about host health systems, language and cultural barriers, legal constraints, financial concerns and anxiety (Mladovsky 2007; PICUM 2010a). Undocumented migrants remain under-researched within the EU (Mladovsky 2007). Undocumented migrants are not included in national statistics due to their insecure status, while legal and social vulnerabilities make them hard to reach for research. Thus, data are often based on estimates and conclusions drawn from findings for the overall migrant population. The quality of data collection and statistics can be particularly difficult to assess (Mladovsky 2007; Kovacheva and Vogel 2009).

Although increasing, existing literature on the health and access to care of undocumented migrants in the EU is heterogeneous in focus and quality. While some overviews exist (PICUM 2010a; FRA 2011b; Chauvin et al. 2012), none have been found in peer-reviewed journals to date. Authors chose to conduct a scoping review to identify the extent, nature and distribution of existing research evidence, thus clarifying what is known and gaps preventing progress in this under-researched area. Because they do not try to appraise the quality of evidence formally, scoping reviews allow inclusion of a broad range of study designs from both peer-reviewed and grey literature (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Grant and Booth 2009; Levac et al. 2010).

Aim and objectives

The aim of this review is to identify the key research priorities on health and access to health care among undocumented migrants residing in the EU. Objectives were to summarize the extent, nature, distribution and main findings of the available literature. Main gaps in the literature are also discussed.

Methods

Authors used Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping framework with Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s 2010 revisions (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010). This six-stage framework includes: (i) identifying the research question; (ii) identifying relevant studies; (iii) selecting studies; (iv) charting data; (v) collating, summarizing, and reporting results and (vi) stakeholder consultation (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010).

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The York framework suggests a broad, clearly articulated research question, defining concepts, target population, health outcomes, and scope whilst accounting for the aim and rationale of the review (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010). Authors selected the research question: ‘What are the scope (i.e. extent, nature, and distribution), main findings and gaps in the existing literature on health status and access to health care for undocumented migrants residing in one of 27 member states of the European Union?’

Definitions used can be found in Box 1. Authors used the WHO definition of health. Thus, the review included all primary studies referring to physical, mental or social aspects of health within the target population. While the vagueness of this definition can challenge operationalization, it was deemed appropriate due to its broad recognition and frequency of usage. The literature lacks consensus on the definition of ‘access to care’. Authors used Gulliford and colleagues’ (Gulliford et al. 2001) definition as it is more specific than most. Authors defined undocumented migrants according to the European Glossary on undocumented migration, due to its frequency of use.

KEY MESSAGES.

Only 54 primary sources were identified in this scoping review on health and access to care for undocumented migrants in EU27, most of which lacked methodological rigour and consistency—particularly in sampling. This indicates a significant need for more and higher-quality research on this subject.

Methodological challenges in accessing this largely invisible population need addressing, requiring co-operation between the various actors (e.g. NGO and health staff gatekeepers, academic communities and policy makers) at regional, national, and institutional levels.

Improved awareness of health-care rights and obligations for undocumented migrants could reduce ambiguities and anxieties limiting access to this group for health staff and researchers.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

The York framework recommends searching multiple literature sources to increase comprehensiveness (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). Authors searched electronic databases, key journals and websites.

First, electronic databases PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Global Health, CINAHL Plus and PsychINFO databases were searched systematically, using the terms ‘undocumented AND migrant AND health AND EU countries’ adapted to the MeSH headings for each database. As ‘undocumented’ is used interchangeably with ‘illegal’, ’unauthorised’, ‘irregular’, ‘compliant/non-compliant/semi-compliant (im)migrants’ (UWT 2008), all search terms were used.

For example, in PubMed the search strategy was: (“undocumented”[All Fields] OR “illegal”[All Fields] OR “unauthori?ed”[All Fields] OR “compliant"[All Fields] OR “irregular”[All Fields] OR “Illegal Migrants”[MeSH Term]) AND (“migrant*”[All Fields] OR “migration”[All Fields] OR “immigrant*”) AND (“Delivery of Health Care”[MeSH Heading]) AND (“EU”[All Fields] OR “European Union”[MeSH Heading] OR “Europe*”[All Fields] OR “Europe”[MeSH Heading]).

Second, key journals, websites and references were searched purposefully. Four key journals on migration were hand-searched (i.e. International Migration; Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies; Journal of Refugees Studies and European Journal of Migration and Law). For websites and references, a four-stage search strategy was implemented: (i) publications posted on websites of well-known non-profit organizations and EU-related migration institutions were searched; (ii) relevant citations were snowballed to references and websites of other pertinent organizations, including those of undocumented migrant projects; (iii) a Google search of ‘undocumented migrants’ was conducted to include additional relevant documents and (iv) stakeholder recommendations were assessed according to inclusion criteria. Table 1 provides a list of organization and project websites searched.

Table 1.

List of organizations and projects included in targeted website searches, in alphabetical order

| Organizations | Projects |

|---|---|

| European Commission–United Nations Joint Migration and Development Initiative (JMDI) | Clandestino |

| European Migration Network (EMN) | European Best Practices in Access, Quality and Appropriateness of Health Services for Immigrants in Europe (EUGATE) |

| European Union (EU) | European Programme for Integration and Migration (EPIM) |

| European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FDA) | ITSAL project |

| International Organization for Migration (IOM) - Europe | Health and Social Care for Migrants and Ethnic Minorities in Europe (HOME) |

| Médicines du Monde (Doctors of the World) | Health care in Nowhereland |

| Médicines Sans Frontiers (Doctors Without Borders) | Health for Undocumented Migrants and Asylumseekers (HUMA) Network |

| Migrants Rights Network (MRN) | MIGHEALTHNET |

| Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM) | PROMO |

| Quality in and Equality of Access to Healthcare Services (HealthQUEST) | |

| Undocumented Workers Transitions (UWT) |

Stage 3: study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established via an iterative process. Authors agreed initial selection criteria based on the research question, focusing on primary research on health status and/or health-care access of undocumented migrants in the EU27. All study designs, intervention types and participants (e.g. undocumented migrants, health professionals) were considered. Study outcomes were restricted to health status and access to health care for undocumented migrants. This study did not specifically address refugees, asylum seekers or victims of trafficking, although they may have been included as undocumented migrants. All authors agreed the final selection criteria (available in Box 2).

Box 2 Final inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Primary research studies:

|

| Exclusion criteria | Studies were excluded if:

|

Box 1 Key definitions.

| Health | ‘A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO) |

| Access to care | ‘Facilitating access is concerned with helping people to command appropriate health care resources in order to preserve or improve their health’, depending on availability, accessibility, acceptability, barriers to utilization (Gulliford et al. 2001) |

| Undocumented migrants | ‘Foreign citizens present on the territory of a state, in violation of the regulations on entry and residence, having crossed the border illicitly or at an unauthorized point: those whose immigration/migration status is not regular, and can also include those who have overstayed their visa or work permit, those who are working in violation of some or all of the conditions attached to their immigration status: and failed asylum seekers or immigrants who have no further right to appeal and have not left the country’ (European Glossary on undocumented migration) |

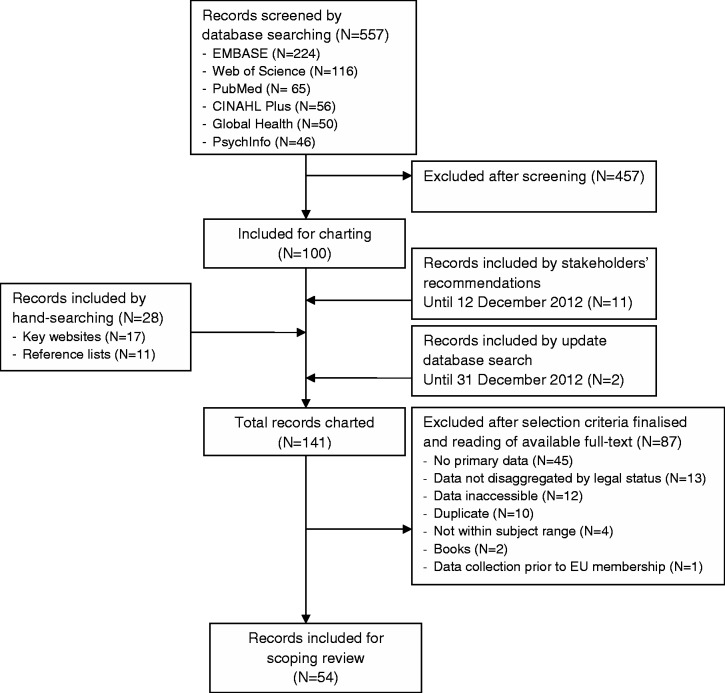

The first author was responsible for screening titles and abstracts found in electronic databases, documents from citations, and key websites according to agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 2). Co-authors were consulted during the study selection process as needed. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram of the process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection of records included in scoping review

Stage 4: data charting

Relevant sources were charted in Excel using the following column headings: lead author, publication year, title of source, type of source (e.g. original article, report), type of search (i.e. electronic database, hand-search, reference searching, stakeholder recommendation), name of database, name of journal or organization, country of data collection, year(s) of data collection, study design, methods, target population, sampling method, key demographics (i.e. number, sex and age of participants), whether undocumented migrants were defined (i.e. yes/no/unclear), definition used if undocumented migrant was defined, study objective(s), main study findings and recommendations. These headings resulted from an iterative process, with several added during the charting process as authors agreed the final list. The first author was primarily responsible for data extraction with support from the second author on sources in Spanish, Italian and Portuguese.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting results

First, results on the nature, extent and distribution of studies were summarized. Second, summarization of findings was guided by the research question (i.e. access and barriers to health care) and WHO definition of health (i.e. physical, mental and social). Third, important themes that emerged from analysis were added.

Stage 6: consultation with stakeholders

A stakeholder group was organized as part of this study to provide feedback on preliminary results. Sixteen experts in the field were approached via email in August 2012, of whom thirteen agreed to participate. The consultation process took place in two stages. First, stakeholders were sent a draft of results on the extent, nature and distribution of literature and asked to provide initial feedback addressing questions such as ‘Did you expect these results?’ and ‘What can be done to make the results more useful?’ and suggesting themes for displaying summary findings. Feedback was used to develop the coding manual for analysis. Second, stakeholders were sent a draft of the results section and asked for feedback, including any policy and research recommendations that could inform the discussion section.

Results

Extent of the literature

Figure 1 is a flow diagram for the 54 sources included of 598 identified. Initial database searching provided 27 sources (50%). Hand-searching key websites (N = 10) and reference lists (N = 7) provided 31%. Stakeholder recommendations (N = 8) provided 15%. An updated database search provided 4% (N = 2).

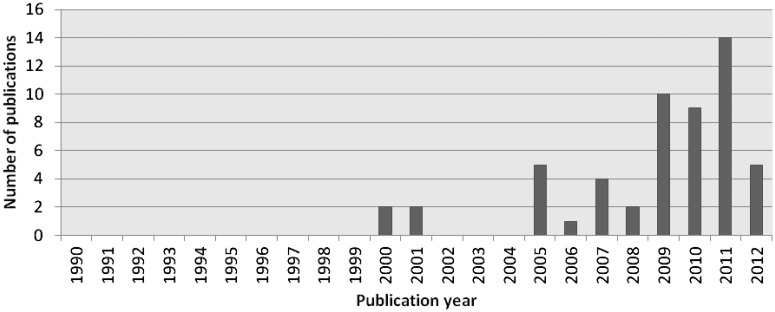

Figure 2 shows numbers of sources by publication year. During 1990–99, none were found. Two studies each were published in 2000 and 2001. An increase began in 2005, with most (26%; 14/54) published in 2011. Forty-four sources included the health of undocumented migrants in study objectives, while 10 (19%) included it in a general focus on migrant health.

Figure 2.

Number of publications on health and access to health care for undocumented migrants in the EU27 by publication year

Nature of the literature

Publications were from public health, epidemiology, sociology, medical anthropology and policy disciplines. Thirty (56%) were original peer-reviewed journal articles, 17 (31%) were reports, 4 (7%) were theses and 3 (6%) were meeting abstracts. Study designs and methods were not always clearly described, but 28 (52%) were qualitative, 13 (24%) quantitative, 9 (17%) mixed-methods and 4 (7%) interventions. Qualitative studies often used multiple methods, such as a combination of semi-structured interviews, focus groups and/or participant observations. Quantitative studies usually used one data-collection method, often cross-sectional surveys. Only one study was described as longitudinal (Castañeda 2008), although several used follow-up methods (Lebouché et al. 2006; Castañeda 2009; Mensinga et al. 2010; Castañeda 2011).

A few studies clearly described their sampling methodology, while most provided minimal or no explanation. The majority used purposeful sampling including snowball, consecutive, criterion and quota strategies. Only four quantitative studies used some form of random selection. An intervention study used random sampling to assign participants to three treatment regimes (Matteelli et al. 2000), one cross-sectional study used two-stage stratified cluster sampling (Torres and Sanz 2000), another cross-sectional study used randomization of matched cohorts (Veenema et al. 2009), and a survey protocol required random selection of eligible participants (Chauvin et al. 2009).

About half the sources included a definition of ‘undocumented’ migrants. Some of these were clearly defined, while most used a few descriptive words (e.g. ‘those without permission to stay’). Most (36; 67%) used the term ‘undocumented’, 10 (19%) used ‘illegal’, 5 (9%) ‘irregular’ and 2 (4%) ‘unauthorised’. One Swedish study used the term ‘Gömda’, meaning ‘hidden’, to refer to those living without legal status (MSF 2005). Forty sources (74%) included undocumented migrants as study participants, 13 (24%) only included health professionals or other experts, and 1 (2%) tested a health information intervention (Cacciani et al. 2005).

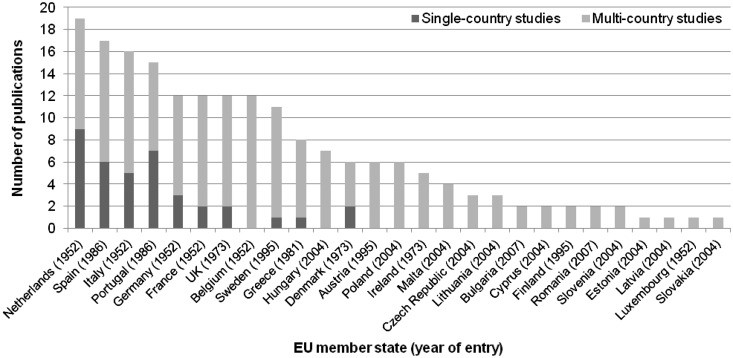

Distribution of the literature

Figure 3 shows the 38 (70%) single-country and 16 (30%) multi-country studies included, by EU member state. Multi-country studies included primary data collection in more than one EU member state, ranging from 2 to all 27. Estonia, Latvia, Luxembourg and Slovakia were least represented, only included in one multi-country study. Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Romania and Slovenia (N = 2), the Czech Republic and Lithuania (N = 3), Malta (N = 4), Ireland (N = 5), Poland (N = 6), Austria (N = 6), Hungary (N = 7) and Belgium (N = 12) were also solely represented in multi-country studies. Remaining member states were included in both single and multi-country studies, with the Netherlands most represented in 24% (9/38) single-country and 63% (10/16) multi-country studies.

Figure 3.

Number of single and multi-country studies on health and access to health care for undocumented migrants by EU member state (EU 2010)

Descriptions of migrant demographics were far from uniform. Most (85%) publications included a mix of male and female participants, with 6 (11%) only including women and 2 (4%) only including men. There were large variations in ages of study participants, although the average was just over 30 years old, with the exception of two studies focusing on children (Mensinga et al. 2010) and youth (Bloch and Zetter 2011). Of the 40 publications including participation of undocumented migrants, 7 (18%) provided no detail on countries of origin. Only one focused on migrants from a specific country, namely Afghanistan (Fidan 2010). Remaining sources (N = 32) included undocumented migrants from various origins, including 30 (94%) African, 22 Asian (68%), and 21 each American (66%) and other European (66%).

Thematic findings

Findings were summarized according to four themes: (i) physical, mental, and social health issues, (ii) access and barriers to care, (iii) vulnerable groups and (iv) policy and rights. Table 2 shows thematic coverage by study, with many including multiple themes. Most (N = 43; 80%) included findings on access to care. Perceived or measured physical and mental health of undocumented migrants were described by 15 (29%) and 9 (17%) sources, respectively. Approximately 29%, mostly reports, included findings on social health, particularly occupational health and living conditions. Vulnerable groups (e.g. children, pregnant women, detainees) were highlighted by 12 (23%) sources. Two sources described an intervention to improve data collection. Of 17 that analysed policy or gave an overview of undocumented migrants’ rights, most were reports (53%; 9/17) or theses (24%; 4/17).

Table 2.

Coverage of themes for each of the 54 sources (multiple themes possible), displayed in alphabetical order by type of source

‘✓’ indicates theme is covered, but does not reflect depth of coverage.

Physical, mental and social health

Several studies described poor self-reported health among undocumented migrants. For example, MSF found undocumented migrants’ health deteriorated since coming to Sweden (MSF 2005). Chauvin found digestive, musculoskeletal, respiratory and gynaecological complaints most common among undocumented migrants in an 11-country study (Chauvin et al. 2007). A Dutch providers survey found undocumented migrants had significantly more skin and digestive issues than documented migrants (Van Oort et al. 2001). Antenatal care was the primary reason undocumented migrants visited one Berlin clinic, followed by chronic, paediatric, dental, acute and injury care (Castañeda 2009). While several studies focused on access to HIV and TB screening, few analysed the burden of these infections among undocumented migrants. One study found 7.1% HIV prevalence among 834 undocumented migrants; however, the population was partially drawn from two HIV clinics (Chauvin et al. 2007). Two studies reported increased vulnerability to sexual violence among undocumented migrants (Van Den Muijsenbergh 2007; Keygnaert et al. 2012).

Among studies reporting on health status, psychological issues appeared most widespread. Two studies associated increased stress, depressive, anxiety, sleeping and somatic symptoms among undocumented migrants with their insecure living and working conditions (PICUM 2010; Biswas et al. 2011). High suicide rates were found among those in detention centres (MDM 2009). Van Oort found Dutch general practitioners significantly more frequently diagnosed mental disorders among undocumented than documented migrants (Van Oort et al. 2001), while Schoevers concluded that mental disorders might be under-reported as female participants seemed hesitant to discuss them (Schoevers 2011).

While several studies found undocumented migrants worked in poorer conditions than documented migrants, only one analysed potential health effects in detail (Sousa et al. 2010). As part of ‘ITSAL project’, Sousa and colleagues found undocumented workers three times as likely to report health problems as documented workers (Sousa et al. 2010). Another ITSAL publication on work conditions (e.g. high job instability, vulnerability, low remuneration, poor social benefits, long hours and fast-paced work) concluded undocumented workers’ health depended largely on the health and safety measures taken by employers (Porthé et al. 2009). McKay found vulnerability and disempowerment were particularly severe among female domestic workers (McKay et al. 2009).

None of the studies analysed the health effects of poor living conditions, though it is likely these contributed to worsened health. Chauvin found half of participants in a multi-country study resided in insecure and overcrowded conditions (Chauvin et al. 2009). Collantes found 47% of undocumented respondents living in ‘insanitary or dangerous accommodation’ (Collantes et al. 2011), seen also in photographic evidence of Afghan migrants’ living conditions in Greece (Fidan 2010).

Access and barriers to care

Four quantitative studies analysed associations between documentation status and care seeking and usage. One reported no significant association between usage and status, although confounders appeared unadjusted for (Torres-Cantero et al. 2007). A second reported an association for migrant men after adjusting for gender (Dias et al. 2008). Two found both usage and care-seeking were significantly associated, even after adjusting for confounders (Torres and Sanz 2000; Dias et al. 2011b). A study on migrants in detention showed that those of Asian origin were significantly less likely to seek care than those from other regions (Dorn et al. 2011). Several qualitative studies indicated health-care usage was difficult for migrants from Brazil (Dias et al. 2010) and women who migrated for personal reasons (Schoevers 2011).

Obstacles to health-care access were reported at primary, secondary and tertiary level, with access particularly limited for the latter two. Primary-care access was often delayed, with the continuum of care particularly lacking for pregnant undocumented migrants (Van Den Muijsenbergh 2007; Castañeda 2009; PICUM 2010b). Schoevers explored the use of patient-held records to improve continuity of care and empowerment among undocumented women, but results were unsatisfactory (Schoevers 2011). Cacciani and colleagues reported on a shared information system, to improve health data collection on undocumented migrants across outpatient clinics in Italy, which appeared promising enough to scale up (Cacciani et al. 2005).

Hospital referrals were limited (Veenema et al. 2009), with some cases refused at hospitals (Dorn et al. 2011). Several studies raised concerns about mental health services access (Castañeda 2008; Baghir-Zada 2009; Veenema et al. 2009; Dauvrin et al. 2012), with one providing in-depth analysis of barriers in 14 EU member states (Strassmayr et al. 2012). Access to dental (Castañeda 2008; Baghir-Zada 2009; Martens 2009), HIV (Lebouché et al. 2006; Chauvin et al. 2007; Heus 2010; Dias et al. 2011c) and TB services (Matteelli et al. 2000; Carvalho et al. 2005; Schoevers 2011) were also reported as limited.

About half the studies provided some analysis of reasons undocumented migrants experienced poor health services access. Lack of awareness of legal entitlements among both undocumented migrants and health-care providers was often cited. Ambiguities on what constituted an ‘emergency’ and lack of guidelines on treatment options contributed to uncertainty among health professionals (Biswas et al. 2011; Jensen et al. 2011) and denial of entitled care (MDM 2009). Fear of being reported to the authorities was cited as an important barrier to care seeking, even in the absence of any reporting obligations (PICUM 2010b). Financial obstacles limited access to secondary care, with access to primary care also affected. Costs prevented many migrants from accessing care or medicines, while reimbursement systems increased workloads among health-care providers. Cultural and language barriers were described as reducing undocumented migrants’ ability to negotiate treatment options, potentially compromising quality of care (FRA 2011a).

While health-care professionals in two studies reported not varying treatment by patient documentation status (Biswas et al. 2011; Jensen et al. 2011), two studies found numbers of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions differed by status. Dauvrin and colleagues found both restricted for undocumented patients (Dauvrin et al. 2012). Van Oort found treatments decreased while diagnoses increased for undocumented patients (Van Oort 2001). Sources indicated quality of care might be reduced for undocumented patients as they may be difficult to treat due to the complexity of their health problems, limited socio-cultural skills among providers, linguistic issues during consultations, and added administrative efforts (Veenema et al. 2009; Biswas et al. 2011; Dias et al. 2011a; Jensen et al. 2011). Thus, access for undocumented migrants was described as ‘variable and unpredictable’ (Schoevers 2011), depending on choices of individual health workers (Martens 2009).

Access appeared improved by the presence of voluntary health organizations. For example, Schoevers concluded better access to care among asylum seekers compared with undocumented migrants might be because they were more likely to be exposed to voluntary organizations at asylum centres (Schoevers 2011). Voluntary organizations were reported to play an important role in referring undocumented migrants to ‘accessible’ primary- and secondary-care providers and in actual health-care provision via outreach clinics (Baghir-Zada 2009; Yosofi 2009; PICUM 2010b; Castañeda 2011; Schoevers 2011). Some organizations also provided advocacy and legal support if needed (Baghir-Zada 2009; FRA 2011b). However, financial constraints limited their activities (Baghir-Zada 2009). Additionally, one source cautioned that they should not be become an ‘alternative structure of care’ for undocumented migrants (PICUM 2010b).

Several sources indicated that lack of health-care access encouraged alternative health-seeking behaviours. One in-depth analysis showed undocumented migrants self-medicated, sought advice from doctors in their country of origin, and borrowed health insurance cards (Biswas et al. 2011).

Vulnerable groups

Particularly vulnerable groups that emerged from analysis were pregnant women, children and detainees. Several studies described lack of or delays for antenatal care. Van den Muijsenbergh found pregnant undocumented migrants faced payment barriers at hospitals and lacked referrals to gynaecologists (Van Den Muijsenbergh 2007). Castañeda found undocumented women most frequently sought obstetric care (Castañeda 2009). Schoevers found low contraceptive usage, limited sexually transmitted infection screening, high abortion rates, and lack of sexual and gynaecological treatment among undocumented women (Schoevers 2011).

Delayed health care seeking among undocumented children and their parents was frequently reported. Mensinga found that lack of knowledge among parents and health-care providers on respective rights and obligations caused confusion when seeking care (Mensinga 2010). Chauvin concluded that unhygienic living conditions and frequent house moves adversely affected physical and mental health of both parents and children (Chauvin et al. 2009). Two studies discussed missed vaccinations amongst newborns (PICUM 2010b; Collantes et al. 2011), while Castañeda described the challenges of registering an undocumented baby (Castañeda 2009). Bloch explored the experiences of young undocumented migrants (18–31 years), finding their status affected their socioeconomic opportunities (e.g. limited aspirations, insecure employment) although coping with adversity resulted in a sense of accomplishment (Bloch and Zetter 2011).

Two studies reported on the health situation of undocumented migrants in detention centres (MDM 2009; Dorn et al. 2011). Dorn and colleagues analysed health care seeking among detainees in the Netherlands, finding nearly 50% had sought care—mostly for injuries and dental problems—25% of whom were denied care (Dorn et al. 2011). An MDM study reported high suicide rates among detainees in EU member states (MDM 2009).

Policy and rights

Studies analysing policies and rights concluded that legal entitlements to health care for undocumented migrants, including entitlements to emergency care, child immunizations, antenatal care and mental health services, varied considerably across EU member states. Legal entitlements did not correspond with access to care. Dauvrin found similar barriers for undocumented migrants among different health systems, including communication, cultural misunderstandings, referral difficulties and delayed or disrupted care (Dauvrin et al. 2012). Jensen found emergency room physicians described barriers as due to a lack of rights-based policies (Jensen et al. 2011). Several sources also reported within-country differences in implementation of rights, at regional, institutional and individual levels among health-care providers and employers.

Authors generally described policies on access to care for undocumented migrants as increasingly restrictive, largely to discourage entry of new migrants (MDM 2009; Grit et al. 2012). However, three studies reporting on the effects of a new regulation on access to care for undocumented migrants in the Netherlands found access and awareness of policy and rights had increased (Martens 2009; Veenema et al. 2009; Mensinga et al. 2010).

Discussion

This study provided an overview of the scope and main findings of empirical work, published in peer-reviewed and grey literature, on health and access to care of undocumented migrants residing within the EU27. Only 54 primary sources were identified, most of which lacked methodological rigour and consistency—particularly in sampling. This indicates a significant need for more and higher-quality research on this subject. Are conclusions possible from a review of such sources? While there is a risk that study flaws could be repeated in the review, some trends appear clear.

Extent, nature and distribution of sources

While some member states (e.g. Netherlands, UK, Spain, Italy) were included in many more studies than were others, these have some of the highest estimates of foreign irregular residents, potentially explaining this difference (Clandestino 2009). Most member states were represented within multi-country studies rather than those tailored to national contexts. While large-scale country comparisons are important, they may lack depth, consistency, or quality (e.g. methodology and data collection affected by local researchers with differing research skills). Future multi-country studies would benefit from increased methodological transparency and consistency.

Much of the available research was conducted by NGOs. Because of their knowledge of the social, mental and physical well-being of undocumented migrants and greater access to this hidden group, NGOs are important actors in this field. However, potential conflicts of interest between research and health advocacy missions must be considered when interpreting their outputs. However, external researchers may be less knowledgeable of the lived reality of undocumented migrants and often rely on the same NGOs for data collection or recruitment. Future collaborative research between NGO and academic researchers could strengthen the evidence base.

More and better quality research within individual member states, particularly longitudinal studies, is clearly needed. Methodological issues (e.g. recruitment, sampling, and follow-up of undocumented migrants) need to be addressed. Invisibility of undocumented migrants, especially those not seeking care, remains a culprit. Research is needed to support policies on healthy migration and develop interventions and documentation systems that provide undocumented migrants with greater stability. Close co-operation between governments and NGOs may be needed to achieve this.

Health status and access

A possible reason the knowledge base on undocumented migrant health status was poor is because this often relies on availability of routine data. The main reason for excluding studies in this review, after charting, was lack of primary data. Most of these studies relied on monitoring systems of formal health-care usage within the population that would likely under-represent undocumented migrants. It may be impossible to include this relatively ‘invisible’ population in routine health data collection, but important lessons can be learned from initial data-collection interventions, such as that of Cacciani and colleagues (Cacciani et al. 2005). Existing research on migrant health often overlooks likely differences in health status and experiences of documented vs undocumented migrants (e.g. 13 studies excluded for lacking disaggregated results). Future research could usefully be disaggregated by documentation status, as results for these migrant sub-populations are likely to be different.

Access to care seemed particularly important, as 80% of studies reported on it. Access is universally defined for those living in the EU27, under Article 35 of the European Union Charter of Universal Rights, as ‘Everyone has the right of access to preventative healthcare and the right to benefit from medical treatment under the conditions established by national laws and practices’ (EU 2000). However, a comparative study of national policies showed wide disparities in how this right to health care was exercised (Cuadra 2011). The same barriers to timely health-care access were found consistently. For example, while minimal research was conducted on physical, mental, and social health separately, that available suggested the stressful environments in which undocumented migrants often live and work are not conducive to health, particularly mental health.

Policy and rights

One reason for the disappointing number of primary studies is that research on this topic is relatively new, only increasing slowly since 2005. Unfortunately, this makes it difficult to detect any changes in health or health-care access for undocumented migrants in the past years. Research may have increased because 2005 was the time EU migration policy began shifting towards national security (Triandafyllidou 2009), resulting in more stringent internal (e.g. health-care access) and external migration control (e.g. borders) (Ingleby 2012). For example, the Treaty of Lisbon strengthened the EU’s legal position in returning undocumented migrants to countries of origin (Brady 2008). Increased discussions on international platforms, such as the 2010 3rd European Health Conference on Integrated Public Health in Amsterdam, the 2011 9th International Conference of the European Network for Mental Health Service Evaluation in Ulm, and the 2011 7th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health in Barcelona, likely contributed to increased research interest, although not the drop in publications in 2012.

Policy advocacy within the EU27 should address prevailing misconceptions surrounding rights and obligations to health care for undocumented migrants. This could be described not only as ‘the right thing to do’ (i.e. in accordance with Article 35 of the European Charter of Universal Human Rights), but also of public health benefit. Results suggest HIV and tuberculosis rates may be relatively high among undocumented migrants (Chauvin et al. 2007), while their access to screening and treatment is relatively low (Matteelli et al. 2000; Carvalho et al. 2005; Lebouché et al. 2006; Dias et al. 2011c). To control these and other health issues effectively, public health care would need to reach all, even those without documentation.

Health care for undocumented migrants could become more consistent. Several sources showed individual health-worker choices, rather than policies, determined access. This indicates some providers take on the majority of work, which seems an unfair and sustainable solution (PICUM 2010b; Ingleby 2012). Undocumented migrants seeking health care they are legally entitled to should be able to access services at their nearest facility. Policy makers thus have a responsibility not to shift the burden of interpreting legal rights to already overburdened health staff.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, a scoping review only includes studies within authors’ search capacity (e.g. accessible on databases searched or through stakeholders). That recommended studies were not found during database searches indicates the challenges of locating all primary research on this topic and likelihood that much of this research remains unpublished and inaccessible (e.g. due to the variety of potential search terms, political sensitivity). Second, some stakeholders were more active than others (e.g. one recommended three additional Dutch studies, potentially skewing distribution data). Third, relevant publications may exist outside of authors’ language capabilities, despite covering several major European languages. Finally, authors did not assess evidence quality, as the quantity and quality of studies were insufficient for a meaningful systematic review. Not excluding on quality gave authors the opportunity to include a broader range of evidence from both peer-reviewed and grey literature. However, this means summary findings should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions

This is a first attempt at a comprehensive overview of available primary evidence on health and access to care for undocumented migrants. This scoping review underlines the need for more and better quality research. Methodological challenges, in accessing this largely invisible population, need addressing. This requires co-operation between the various actors (e.g. NGO and health staff gatekeepers, academic communities, policy makers) at regional, national and institutional levels. Improved awareness of health-care rights and obligations for undocumented migrants could reduce ambiguities and anxieties limiting access to this group for health staff and researchers. As international and national migration policies become increasingly restrictive, urgent action is likely needed to avoid worsening the status quo.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful for stakeholder contributions. Emily Ahonen, Indiana University, provided input on results and discussion sections. Heide Castañeda, University of South Florida, gave feedback on structure and recommended an additional source. Pierre Chauvin, National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) Université Pierre et Marie Curie, suggested topics and literature for discussion. Sónia Dias, New University of Lisbon, provided general feedback and an additional source. David Ingleby, University of Utrecht, suggested topics and literature for discussion. Michele LeVoy, Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM), recommended two additional sources. Sonia McKay, London Metropolitan University, provided feedback on results and suggested discussion points. Maria van der Muijsenbergh, St Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen, suggested clarifications of results, discussion points, and three additional sources. Elena Riza, University of Athens Medical School, commented on methods and results. Marianne Schoevers, St Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen, provided feedback on methods and results. Ursula Trummer, Centre for Health and Migration in Vienna, provided input on results and discussion. Authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their encouraging and useful feedback.

Funding

This study was conducted on a voluntary basis.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Ahonen EQ, Lopez-Jacob MJ, Vazquez ML, et al. Invisible work, unseen hazards: The health of women immigrant household service workers in Spain. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53:405–16. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen EQ, Porthé V, Vazquez ML, et al. A qualitative study about immigrant workers' perceptions of their working conditions in Spain. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2009;63:936–42. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baghir-Zada R. Illegal aliens and health(care) wants. The cases of Sweden and the Netherlands. Doctoral Thesis, Malmö University. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Kristiansen M, Krasnik A, Norredam M. Access to healthcare and alternative health-seeking strategies among undocumented migrants in Denmark. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:560. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch A, Zetter R. ‘No Right To Dream’. The Social and Economic Lives of Young Undocumented Migrants in Britain. London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brady H. EU Migration Policy: An A-Z. London: Centre for European Reform; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno S, Federico B, Geraci S, et al. Designing an organizational pathway for illegal immigrants to perform vaccino-prophylaxis interventions. Journal of Preventative Medicine and Hygiene. 2005;46:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett J, Whyte D. The Wages of Fear: Risk, Safety and Undocumented Work. Leeds: Positive Action For Refugees & Asylum Seekers (PAFRAS) Liverpool: The University of Liverpool; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciani L, Baglio G, Forcella E, et al. Testing a new health data information system for illegal immigrants in Italy. 13th Annual EUPHA Meeting. Graz. European Journal of Public Health. 2005;15:175–6. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho ACC, Saleri N, El-Hamad I, et al. Completion of screening for latent tuberculosis infection among immigrants. Epidemiology and Infection. 2005;133:179–85. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804003061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H. Paternity for sale. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2008;22:340–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2008.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H. Illegality as risk factor: a survey of unauthorized migrant patients in a Berlin clinic. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1552–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H. Medical humanitarianism and physicians’ organized efforts to provide aid to unauthorized migrants in Germany. Human Organization. 2011;70:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin P, Mestre MC, Simonnot N. Access to Health Care for Vulnerable Groups in the European Union in 2012. An Overview of the Condition of Persons Excluded from Healthcare Systems in the EU. Paris: Médecins du Monde; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin P, Parizot I, Drout N, Simonnot N, Tomasin A. European Survey on Undocumented Migrant’s Access to Health Care. Paris: Médecins du Monde European Observatory on Access to Healthcare; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin P, Parizot I, Simonnot N. Access to Healthcare for Undocumented Migrants in 11 European Countries. Paris: Médecins du Monde European Observatory on Access To Healthcare; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clandestino. Comparative Policy Brief—Size of Irregular Migration. Athens: Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collantes S, Soler A, Klorek N, Maslinski K. Access to Healthcare and Living Condition of Asylum Seekers and Undocumented Migrants in Cyprus, Malta, Poland and Romania. Paris: Médecins du Monde HUMA Network; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Collantes S. Access to Health Care for Undocumented Migrants in Europe. Brussels: PICUM; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho E, Pereira C, Silva A. Illegal stay and prenatal care in immigrant pregnant women living in Portugal. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2011;65(Suppl 1):A328. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadra CB. Right of access to health care for undocumented migrants in EU: a comparative study of national policies. European Journal of Public Health. 2011;22:267–71. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauvrin M, Lorant V, Sandhu S, et al. Health care for irregular migrants: pragmatism across Europe: a qualitative study. BMC Research Notes. 2012;5:99. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias S, Gama A, Cortes M, De Sousa B. Healthcare-seeking patterns among immigrants in Portugal. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2011a;19:514–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias S, Gama A, Rocha C. Immigrant women’s perceptions and experiences of health care services: Insights from a focus group study. Journal of Public Health. 2010;18:489–496. [Google Scholar]

- Dias S, Gama A, Severo M, Barros H. Factors associated with HIV testing among immigrants in Portugal. International Journal of Public Health. 2011b;56:559–66. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias S, Gama A, Silva AC, Cargaleiro H, Martins MO. Barreiras no acesso e utilização dos serviços de saúde pelos imigrantes. A perspectiva dos profissionais de saúde [Barriers in access and utilization of health services among immigrants. The perspective of health professionals] Acta Medica Portuguesa. 2011c;24:511–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias SF, Severo M, Barros H. Determinants of health care utilization by immigrants in Portugal. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8:207. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn T, Ceelen M, Tang MJ, et al. Health care seeking among detained undocumented migrants: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:190. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hamad I, Casalini C, Matteelli A, et al. Screening for tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infection among undocumented immigrants at an unspecialised health service unit. Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2001;5:712–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EU. 2000 Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf, accessed 4 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EU. 2010 How the EU works - countries. http://europa.eu/about-eu/countries/index_en.htm, accessed 5 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fidan GO. An Approach to Undocumented Migrants in Greece Focusing on Undocumented Afghans. Athens: Greek Council of Refugees; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FRA. Migrants in an Irregular Situation: Access to Healthcare in 10 European Union Member States. 2011a. Solidarity. Luxembourgh: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) [Google Scholar]

- FRA. Fundamental Rights of Migrants in an Irregular Situation in the European Union. 2011b. Solidarity. Luxembourgh: FRA. [Google Scholar]

- FRA. Migrants in an Irregular Situation Employed in Domestic Work: Fundamental Rights Challenges for the European Union and its Member States. Luxembourgh: FRA; 2011c. [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grit K, Den Otter JJ, Spreij A. Access to health care for undocumented migrants: a comparative policy analysis of England and the Netherlands. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2012;37:37–67. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1496011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford M, Hughes D, Figeroa-Munoz J, et al. Access to Health Care. Report of a Scoping Exercise for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO) London: The Public Health and Health Services Research Group, King’s College London; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AR. Access to Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants in California (USA) and Denmark—Rights and Practice. 2005. MSc Thesis, University of Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Heus L. ‘There is no love here anyway.’ Sexuality, identity and HIV prevention in an African sub-culture in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Sexual Health. 2010;7:129–34. doi: 10.1071/SH09075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingleby D. Social Exclusion, Disadvantage, Vulnerability and Health Inequalities. A Task Group Supporting the Marmot Region Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide in the EURO region. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen NK, Norredam M, Draebel T, et al. Providing medical care for undocumented migrants in Denmark: what are the challenges for health professionals? BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:154. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl-Trummer U, Metzler B, Novak-Zezula S. Health Care for Undocumented Migrants in the EU: Concepts and Cases. Brussels: International Organisation for Migration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keygnaert I, Vettenburg N, Temmerman M. Hidden violence is silent rape: sexual and gender-based violence in refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Belgium and the Netherlands. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2012;14:505–20. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.671961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacheva V, Vogel D. The Size of the Irregular Foreign Resident Population in the European Union in 2002, 2005 and 2008: Aggregated Estimates. Database on Irregular Migration. Working Paper No.4/2009. Hamburg: Hamburg Institute of International Economics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larchanché S. Intangible obstacles: health implications of stigmatization, structural violence, and fear among undocumented immigrants in France. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:858–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebouché B, Yazdanpanah Y, Gérard Y, et al. Incidence rate and risk factors for loss to follow-up in a French clinical cohort of HIV-infected patients from January 1985 to January 1998. HIV Medicine. 2006;7:140–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MJC. Masters Public Health Thesis. Maastricht University; 2009. Accessibility of health care for undocumented migrants in the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Matteelli A, Casalini C, Raviglione MC, et al. Supervised preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis infection in illegal immigrants in Italy. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;162:1653–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9912062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay S, Markova E, Paraskevopoulou A, Wright T. The Relationship Between Migration Status and Employment Outcomes. London: Undocumented Worker Transitions; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- MDM. Access to Health Care for Undocumented Migrants and Asylum Seekers in 10 EU Countries. Law and Practice. Paris: Médecins du Monde HUMA Network; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mensinga M, Van Bommel H, Goeman M, Kloosterboer K. Ongedocumenteerde kinderen en de toegang tot ziekenhuiszorg [Undocumented children and the access to healthcare at the hospital] Utrecht: Pharos; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mladovsky P. 2007 Migration and Health in the EU. http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/social_situation/docs/rn_migration_health.pdf, accessed on 5 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MSF. Experiences of Gömda in Sweden: Exclusion from Health Care for Immigrants Living without Legal Status. Stockholm: Médecins Sans Frontièrs; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- PICUM. PICUM’s Main Concerns about the Fundamental Rights of Undocumented Migrants in Europe. Brussels: PICUM; 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- PICUM. Workpackage No. 6: The Voice of Undocumented Migrants. Undocumented Migrants’ Health Needs and Strategies to Access Health Care in 17 EU countries. Brussels: 2010b. Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM) [Google Scholar]

- Porthé V, Benavides FG, Vazquez ML, et al. La precariedad laboral en inmigrantes en situación irregular en España [Precarious employment in undocumented immigrants in Spain and its relationship with health] Gaceta Sanitaria. 2009;23(Suppl 1):107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoevers MA. “Hiding and Seeking” health problems and problems in accessing health care of undocumented female immigrants in the Netherlands. Doctoral Thesis. 2011 Radboud University Medical Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa E, Agudelo-Suarez A, Benavides FG, et al. Immigration, work and health in Spain: the influence of legal status and employment contract on reported health indicators. International Journal of Public Health. 2010;55:443–51. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassmayr CC, Matanov AA, Priebe SS, et al. Mental health care for irregular migrants in Europe: Barriers and how they are overcome. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:367. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Sanz B. Health care provision for illegal immigrants: should public health be concerned? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2000;54:478–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.6.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Cantero AM, Miguel AG, Gallardo C, Ippolito S. Health care provision for illegal migrants: may health policy make a difference? European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17:483–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandafyllidou A. Undocumented Migration: Counting the Uncountable. Data and Trends Across Europe. Athens: Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UWT. Undocumented Migration Glossary. Work Package 5. London: UWT, Roskilde University & Working Lives Research Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Muijsenbergh M. Maternity care and undocumented female immigrants. 5th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health, Amsterdam. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2007;12:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oort M, Kulu Glasgow I, Weide M, De Bakker D. Gezondheidsklachten van illegalen. Een landelijk onderzoek onder huisartsen en Spoedeisende Hulpafdelingen [Health complaints of illegals. A national study amongst physicians and emergency departments] Utrecht: Nivel; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Veenema T, Wiegers T, Devillé W. Toegankelijkheid van gezondheidszorg voor ‘illegalen' in Nederland: een update [Accessibility of healthcare for ‘illegals' in the Netherlands: an update] Utrecht: Nivel; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yosofi T, Van den Muijsenbergh M. Mannen zonder documenten en de huisarts. Gezondheidsklachten van ongedocumenteerde asielzoekers en hun ervaringen met huisartsen [Men without documents and the physician. Health complaints by undocumented asulym seekers and their experiences with physicians] Cultuur Migratie Gezondheid. 2009;7:150–7. [Google Scholar]