Abstract

Background and objectives

Recent studies demonstrated an association between depressive affect and higher mortality risk in incident hemodialysis patients. This study sought to determine whether an association also exists with hospitalization risk.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

All 8776 adult incident hemodialysis patients with Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 survey results treated in Fresenius Medical Care North America facilities in 2006 were followed for 1 year from the date of survey, and all hospitalization events lasting >24 hours were tracked. A depressive affect score was derived from responses to two Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 questions (“down in the dumps” and “downhearted and blue”). A high depressive affect score corresponded with an average response of “some of the time” or more frequent occurrence. Cox and Poisson models were constructed to determine associations of depressive affect scores with risk for time to first hospitalization and risk for hospitalization events, as well as total days spent in the hospital, respectively.

Results

Incident patients with high depressive affect score made up 41% of the cohort and had a median (interquartile range) hospitalization event rate of one (0, 3) and 4 (0, 15) total hospital days; the values for patients with low depressive affect scores were one (0, 2) event and 2 (0, 11) days, respectively. For high-scoring patients, the adjusted hazard ratio for first hospitalization was 1.12 (1.04, 1.20). When multiple hospital events were considered, the adjusted risk ratio was 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) and the corresponding risk ratio for total hospital days was 1.20 (1.07, 1.35). High depressive affect score was generally associated with lower physical and mental component scores, but these covariates were adjusted for in the models.

Conclusions

Depressive affect in incident hemodialysis patients was associated with higher risk of hospitalization and more hospital days. Future studies are needed to investigate the effect of therapeutic interventions to address depressive affect in this high-risk population.

Keywords: depression, ESRD, quality of life, CKD, morbidity

Introduction

Depression is common in patients with ESRD, and affected patients are twice as likely as those without depression to die or require hospitalization within 1 year of this diagnosis (1). Furthermore, in addition to having greater mortality risk, depressed patients report poorer quality of life (2). Recent studies have also demonstrated an association between depressive affect, manifested by depressive symptoms, with higher mortality among patients with ESRD (3–7). Depressive symptoms and associated outcomes have been assessed by self-report using two questions within the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) (4,5). Compared with physician-diagnosed depression, responses indicating a frequency of occurrence of at least “a good bit of the time” for the question “Have you felt so down in the dumps nothing could cheer you up?” had 74.2% agreement; 73.6% agreement was reported with the question “Have you felt downhearted and blue?” (4)

Incident hemodialysis (HD) patients exhibit the highest rates of morbidity and mortality, and the potential role of depressive affect in exacerbating risk remains a concern (1,5). Although not necessarily diagnostic of clinical depression, elicited responses representative for depressive affect can indicate a depressive state among this patient population. In this study, we measured the prevalence of depressive affect among an incident HD population using two questions from the SF-36 within their first 120 days of dialysis. We derived the “depression score” by combining the responses to the two survey questions associated with frequency of feeling “down in the dumps” and “downhearted and blue” (5). The mean score of these questions were used to represent depressive affect and determine the association between depressive affect and the number of hospitalization events, as well as hospital days, during a 1-year follow-up period.

Materials and Methods

Study Sample

The source population included 41,585 adult (age≥18 years) patients undergoing in-center HD at Fresenius Medical Care North America (FMCNA) facilities between January 1, and December 31, 2006, with SF-36 survey results. The study sample consisted of 8776 patients (21% of 41,585 period prevalent patients) who were surveyed as incident patients (i.e., within the first 120 days of the first long-term dialysis session). Patient demographic characteristics and laboratory results were obtained from the FMCNA Knowledge Center data warehouse, which consolidates information from the facility-specific dialysis information systems (8). Baseline characteristics were tabulated as means±SDs for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Consistent with the long history of quality improvement initiatives at FMCNA, this retrospective, observational analysis of healthcare data posed no additional risk to patients. As such, neither IRB review nor informed consent were obtained, since FMCNA did not deem them necessary in that these activities are a normal part of FMCNA quality improvement activities and health care operations. Additionally, all results have been presented as aggregated information that cannot be linked back to individual patients.

Follow-up

Hospitalization events (>24 hours) and total hospital days were tracked for up to 1 year from the date of SF-36 survey. Before each HD treatment, trained clinical staff inquire whether the patient had received medical care since the last treatment in the facility in order to elicit information regarding potential emergency department visits, hospitalization, physician visits, and admissions for clinical procedures. In addition, nursing staff review the patient roster daily to ensure that all treatments provided were matched to all treatments scheduled. Absences were documented and the reason for any absence entered into the electronic dialysis information systems as follows: missed without treatment provided elsewhere, hospitalized, died, recovered kidney function, underwent transplantation, or transferred to another facility. Hospitalized patients have their admission and discharge dates documented. Patients who died or withdrew from dialysis therapy, recovered kidney function, received a kidney transplant, or left the FMCNA system during the 1-year follow-up contributed person-time at risk but were censored on their discharge date.

SF-36 Questions Associated with Depressive Symptoms

The SF-36 has five mental health (MH) domain items, designed to determine the frequency of (1) being nervous, (2) being down in the dumps, (3) feeling calm and peaceful, (4) feeling downhearted and blue, and (5) being happy. Consistent with the literature, we used two of these five (9) as indicators of depressive affect:

MH 2: Have you felt so down in the dumps nothing could cheer you up? (i.e., “Dumps”)

MH 4: Have you felt downhearted and blue? (i.e., “Blue”)

Both items used a 6-point choice of responses: 1=all of the time, 2=most of the time, 3=a good bit of the time, 4=some of the time, 5=a little of the time, or 6=none of the time.

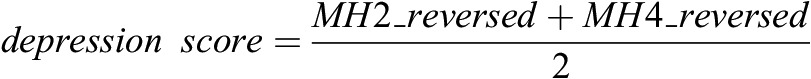

We used the same derivation of depressive affect score as in our prior report (5). Briefly, the initial step was to reverse the item scores so that the higher value represents having more frequent depressive symptoms:

|

Then the revised “depression score” was defined as:

|

In the equation, depressive affect score represents the mean of reversed MH 2 and MH 4 responses. Thus, depressive affect score is a continuous variable ranging from one to six (higher score is worse). In our analysis, we categorized patients into two levels of depressive affect: level 1, “unlikely to be depressed,” if the score was ≤2 and level 2, “more likely to be depressed,” if the score was >2. This cutoff divided the patient cohort into two large comparable groups.

Statistical Analyses

Poisson regression models (10) were used to study the association between depressive affect and the total number of hospitalization events. To account for different exposure time for each patient, the model was offset by exposure-time in months. To minimize the extent to which data were skewed, a log link was implemented for the Poisson regression. With the log link, the Poisson model will produce risk ratio (RR), the ratio of the mean hospitalization rate for depressive affect level 2 versus level 1, with level 1 used as the reference. Poisson regression models were also constructed to determine the association between depressive affect and the total number of hospital days. Three Poisson models were constructed to determine an association between depressive affect and each outcome (hospitalization event and hospital days). Model 1 was unadjusted; model 2 was adjusted for physical component score (PCS), mental component score (MCS) modified to exclude five MH items, and the three MH items other than the two depressive affect items; and model 3 was further adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, albumin, creatinine, hemoglobin, calcium, phosphorus, and transferrin saturation.

Following analytic convention, time to first hospitalization was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method (11) to produce estimated probabilities of first hospitalization stratified by two depressive affect levels. Furthermore, with use of Cox proportional hazards models (12) (with a sequence of models 1–3 as above), the hazard ratio (HR) for first hospitalization during the 1-year follow-up was derived for depressive affect level 2 versus level 1. Association of hospitalization with general PCS and MCS was also assessed for comparison. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Among 8776 patients studied, 5178 (59%) were unlikely to be depressed (level 1 depressive affect), while 3598 (41%) were more likely to be depressed (level 2 depressive affect). For the level 1 group, the depressive affect score averaged 1.4±0.4, consistent with the presence of depressive symptoms between “none of the time” and “a little of the time” (Table 1). For the level 2 group, the depressive affect score averaged 3.4±0.9, consistent with the presence of depressive symptoms between “some of the time” and “a good bit of the time.” Overall, 66.4% of patients had at least one hospital admission in level 2, compared with 61% for level 1 (P<0.001). Between level 1 and level 2 depressive affect, 13.2% and 16.9% of patients, respectively, were eventually censored for death/withdrawal, 3.1% and 3.4% for discharge due to recovery of kidney function, and 23.5% and 22.9% for receiving a kidney transplant during the 1-year follow-up period.

Table 1.

Incident patient characteristics (n=8776)

| Variable | Level 1: Unlikely to Be Depressed (n=5178; 59%) | Level 2: More Likely to Be Depressed (n=3598; 41%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HD vintagea (d) | 47.5±33.0 | 46.9±33.3 | 0.39 |

| Age at SF-36 survey (yr) | 62.9±15.1 | 61.4±14.8 | <0.001 |

| PCS | 32.8±10.7 | 30.9±9.1 | <0.001 |

| MCS | 52.7±8.8 | 37.9±9.1 | <0.001 |

| Depressive affect score (range, 1–6) | 1.38±0.43 | 3.44±0.94 | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 2284 (44.1) | 1716 (47.7) | 0.001 |

| Female | 2894 (55.9) | 1882 (52.3) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 3495 (67.5) | 2462 (68.4) | 0.09 |

| Black | 1520 (29.4) | 999 (27.8) | |

| Other race | 163 (3.2) | 137 (3.8) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 539 (10.4) | 570 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic | 4639 (89.6) | 3028 (84.2) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 2622 (56.8) | 1841 (57.5) | 0.51 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.56±0.47 | 3.52±0.48 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 6.40±2.69 | 6.18±2.56 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.24±1.33 | 11.21±1.36 | 0.40 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 8.69±0.71 | 8.67±0.70 | 0.11 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 4.93±1.30 | 4.94±1.34 | 0.88 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 21.47±8.55 | 21.40±8.91 | 0.70 |

| Equilibrated Kt/V (eKt/V) | 1.38±0.35 | 1.38±0.37 | 0.91 |

| Baseline PCS | 32.8±10.7 | 30.9±9.1 | <0.001 |

| Baseline MCS | 52.7±8.8 | 37.9±9.1 | <0.001 |

Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD. The depressive affect score ranges from 1 to 6, the higher score being more likely to be depressed. “Unlikely to be depressed” had a depressive affect score of 1–2; “more likely to be depressed” had a score of more than 2. HD, hemodialysis; SF-36, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36; PCS, physical composite score; MCS, mental composite score.

Vintage was defined as the number of days from the date of first session of long-term dialysis to the SF-36 survey date.

The mean dialysis vintage at the time of survey of this incident HD cohort was 47±33 days (median, 49 days; range, 0–120 days), likely prompted by an automated reminder on day 45 for patient care staff to obtain the survey. Vintage days between the two depressive affect groups on the date of survey were similar (Table 1). The average age as of the SF-36 survey date for level 2 was 61.4±14.8 years, 1.5 years younger than in the level 1 patients, whose average age was 62.9±15.1 (P<0.001). The level 2 group had a higher proportion of men (47.7% versus 44.1%; P=0.001) and Hispanics (15.8% versus 10.4%; P<0.0001) but similar racial distribution and prevalence of diabetes. The level 2 group also had a lower mean PCS (30.9±9.1 versus 32.8±10.7) and a lower mean MCS (37.9±9.1 versus 52.7±8.8).

The level 2 group had more hospitalization events (1.8±2.3 versus 1.5±2.0) as well as more hospital days (11.4±18.4 versus 9.1±16.3) during the 1-year follow-up than the level 1 group (all significant at P<0.001) (Table 2). A PCS and an MCS higher by 1 SD were significantly (P<0.001) associated with 23% (95% confidence limit [95% CL], 20% to 26%,) and 11% (95% CL, 7% to 14%) fewer mean hospitalization events, respectively. The mean percentage of hospital days was 29% (95% CL, 26% to 33%; P<0.001) lower for PCS and 11% (95% CL, 8% to 15%; P<0.001) lower for MCS.

Table 2.

Summary of outcomes (n=8776)

| Outcomes | Level 1 (n=5178; 59%) | Level 2 (n=3598; 41%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of hospitalization events | 1.5±2.0 | 1.8±2.3 | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stays (d) | 9.1±16.3 | 11.3±18.4 | <0.001 |

| No. of hospitalization events | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 3) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stays (d) | 2 (0, 11) | 4 (0, 15) | <0.001 |

Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD. Values expressed with ranges in parentheses are the median (interquartile range).

For hospitalization events, the unadjusted Poisson model yielded an RR of 1.25 (95% CL, 1.16 to 1.35; P<0.001) for level 2 versus level 1 depressive affect (Table 3). The corresponding RRs were 1.10 (95% CL, 1.01 to 1.21; P=0.03) from adjusted model 2 and 1.13 (95% CL, 1.02 to 1.25; P=0.02) for model 3. For hospital days, the unadjusted Poisson model (model 1) yielded an RR of 1.31 (95% CL, 1.20 to 1.43; P<0.001) for level 2 compared with level 1 depressive affect. The corresponding RRs from models 2 and 3 were 1.15 (95% CL, 1.03 to 1.27; P<0.01) and 1.20 (95% CL, 1.07 to 1.35; P=0.002), respectively.

Table 3.

Association of total hospitalization events, hospitalized days, and time to first hospitalization with depressive affect for incident hemodialysis patients in 2006

| Dependent Variable per Model | Rate/Hazard Ratio for Level 2 versus Level 1 (95% CL) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Poisson regression with logarithmic link function and offset with exposure time | ||

| Total hospitalization events | ||

| Model 1 | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.21) | 0.03 |

| Model 3 | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.25) | 0.02 |

| Total hospitalized days | ||

| Model 1 | 1.31 (1.2 to 1.43) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.27) | 0.01 |

| Model 3 | 1.20 (1.07 to 1.35) | 0.002 |

| Cox proportional hazards regression for time to first hospitalization | ||

| Time to first hospitalization | ||

| Model 1 | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.18) | 0.003 |

| Model 3 | 1.12 (1.04 to 1.20) | 0.003 |

Rate ratios are given for Poisson regression; hazard ratios are given for Cox regression. Category for depressive affect: level 1=less likely depressed, score 1–2; level 2=potentially depressed, score>2–6. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for physical composite score, mental composite score with mental health items removed, and three remaining mental health items. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for hemodialysis vintage≤90 days (incidence) versus >90 days (prevalence), age, sex, race, diebetes, albumin, creatinine, hemoglobin, calcium, phosphorus, and transferrin saturation. 95% CL, 95% confidence limit.

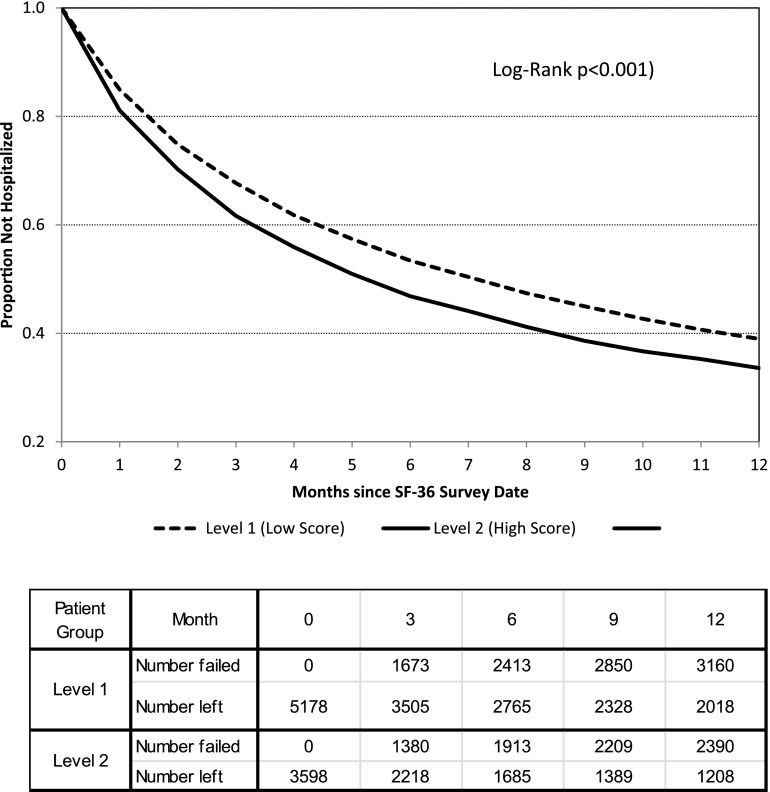

The mean time to first hospitalization differed significantly between groups: 201±2.4 days for level 2 versus 223±1.8 days for level 1 (6.6±0.08 versus 7.3±0.06 months, respectively; log-rank P<0.001) (Figure 1). By the end of the 1-year follow-up period, the survival probability (i.e., not hospitalized) was 0.34 versus 0.39 for level 2 versus level 1 depressive affect, respectively. The Cox proportional hazards models for time to first hospitalization (Table 3) yielded similar results; higher depressive affect score had an unadjusted HR of 1.18 (95% CL, 1.12 to 1.25; P<0.001), with HRs of 1.10 (95% CL, 1.03 to 1.18; P=0.003) from model 2 and 1.12 (95% CL, 1.04 to 1.20; P=0.003) from model 3.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimated survival probabilities for time to first hospitalization.

Discussion

These study results demonstrated that increased severity of depressive affect in patients new to HD was significantly associated with more hospitalization events, more hospital days, and shorter time to first hospitalization during the first year of dialysis. Within 1 year from the SF-36 survey, patients with greater depressive affect had a 13% greater likelihood of being hospitalized and 20% more hospital days after adjustment for age, sex, race, diabetes, SF-36 component scores, and laboratory measurements (model 3). These data are consistent with our earlier work describing depressive symptoms as a significant risk factor for mortality in the early dialysis treatment period (5). This study’s important contribution to the scientific literature is that it extends the association between depressive affect and hospitalization beyond established (i.e., prevalent) dialysis patients and into patients new to dialysis therapy.

While prior work has associated depression in HD patients to hospitalization risk (13), the mechanisms by which such linkage occurs are likely multifactorial and may vary depending on the type of hospitalization. For example, self-reported depressive symptoms, independent of and additive to CKD, are a risk factor for hospitalization in older patients newly diagnosed with heart failure (14). Heart failure and other fluid overload conditions are common in HD patients and tend to recur, with use of healthcare resources recently estimated to cost Medicare $6372 per hospitalization episode and $266 million annually (15). Depressive affect can directly influence poor adherence to diet and fluid regimens (16). Furthermore, chemical brain alterations in depressed patients may affect cognitive dysfunction (which may manifest as poor adherence) (17), and cognitive dysfunction has been associated with depressive affect in HD patients (18). Poor adherence may also extend to missed HD treatments, which has been associated with greater risk for hospitalization from not just cardiovascular causes but all-causes as well (19,20). Poor adherence may also extend to medication adherence and dietary considerations (including anorexia) leading to malnutrition, both of which have been associated with increased hospitalization and mortality risk in this population (21–24).

In addition to nonadherence and other behavioral components (alcohol, smoking, decreased physical activity) linked to depression, biologic mechanisms linking depression to coronary artery disease have been proposed (25). Abnormal platelet function and reactivity are more prevalent in depressed patients (26), which may be mediated through serotonin imbalance (27). Dysregulation of the hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal axis in depressed states may also play a role, particularly with regard to effect on stress responses, either biochemically with inflammatory cytokine imbalances or clinically through abnormalities of BP and heart rate (28–30). Furthermore, autonomic nervous system dysfunction may accompany depression, further exacerbating BP and heart rate dysregulation and potentially manifesting with reduced heart rate variability and cardiac baroreflexes that may further aggravate cardiovascular morbidity (31–33). While inflammation and autonomic dysfunction are not uncommon in patients undergoing HD (34,35), depression may represent an aggravating factor toward greater morbidity.

As noted earlier, high prevalence of depression is associated with initiating dialysis treatment and, subsequently, poor outcomes in the ESRD population (2); however, many clinicians (including nephrologists) have not been comfortable diagnosing and managing depression (36). Screening for depressive affect makes sense for identifying patients at greater risk for depression, and managing patient’s depressive symptoms sooner may potentially reduce patient morbidity and hospitalizations. Reducing the burden of illness within this patient population is the ultimate health care goal; addressing depressive affect could decrease complications and potentially lead to cost savings in the health care system. This is clearly not trivial, as demonstrated for fluid overload and heart failure, among all other potentially actionable causes of hospitalization in the HD population.

Various treatments designed to reduce mortality in the HD population have been promoted, but proposals to manage depression in the general population, although a public health priority, have not reached the same level of priority in dialysis patients. Some of these treatment strategies, such as antidepressant medications (37), changes in dialysis treatment schedules or alternative dialysis therapies (38), cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (39), exercise programs (40), and stress reduction therapies (to include music or art) (41), have been reported to improve symptoms or reduce depressive episodes in patients with ESRD (40). Duarte et al. showed that CBT was effective: HD patients receiving group therapy showed significant improvements in the treatment of depression compared with the control group, who did not receive CBT (39). Another nondrug study by Cukor et al. supports using CBT treatment in HD patients, with a successful reduction in major depression disorder (42). Brown et al. studied patients with both asthma and major depression and determined that effective improvements of depression can help improve or reduce asthma symptoms (43). We await results from a pilot study that will use symptom-targeted therapy (44). However, no broad-based systematic study has been reported in incident HD patients, and prospective studies are needed to determine whether treatment of patients diagnosed with depressive affect will benefit from early screening and treatment.

The present study has many strengths, including a large sample size (n=8776) from a national population of incident HD patients and use of multivariable-adjusted models. However, it also has several limitations. First, this study is a retrospective analysis of observational data; such findings of associations are subject to residual confounding from unmeasured factors, such as socioeconomic status, comorbidity (e.g., cardiovascular disease burden), and health status (e.g., BP) and do not necessarily prove causation (i.e., that depressed affect is the cause of poor survival). Second, we used two questions on the SF-36 questionnaire to assess depressive affect, not the full depression mental health assessment. Third, we could assess risk only for responders to the SF-36 survey, not the entire cohort of incident patients who started HD in 2006. Fourth, while we found that age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, albumin, and creatinine were associated with the depressive affect score, diabetes did not differ between groups, unlike in prior reports. It is possible that diabetes is primarily associated with severity of symptoms or tends to associate more strongly with a clinical diagnosis of depression. Fifth, we treated depressive affect as a baseline covariate, although dialysis initiation by itself could result in depressive symptoms related to loss of bodily function, self-worth, and need for adjustment to a different lifestyle. However, the mean vintage at the time of survey was 47 days (median, 49 days), as noted in the Results section, because an electronic reminder in the dialysis information systems prompts initiation of SF-36 surveys at vintage day 45 for all incident patients. This reminder bypasses the initial 30- to 45-day adjustment period to long-term dialysis treatment, as well as the potential presence of acute debilitating illnesses that accompany transition to long-term dialysis and may help mitigate the effect of the initial shock of requiring this therapy. Future studies should delineate how depressive affect evolves during the course of HD treatment.

In conclusion, this study establishes an association between depressive affect and hospitalization risk in incident HD patients. Its important contribution to the scientific literature is that it extends the association between depressive affect and hospitalization beyond established (i.e., prevalent) dialysis patients and into patients new to dialysis therapy. We posit that identifying and determining the level of depressive affect may allow for possible interventions to manage these patients’ depressive symptoms, thus potentially affecting the need for hospitalization and reducing the number of days spent in the hospital. More frequent hospitalization events and more hospital days affect our health care system, using valuable resources and personnel time, thus increasing overall costs to the system. Future studies are needed to investigate the effect of therapeutic interventions to address depressive affect, preferably in the form of prospective randomized trials.

Disclosures

All authors are employees of Fresenius Medical Care, North America. Part of this work was presented as a poster in the National Kidney Foundation 2012 Spring Clinical Meeting.

Acknowledgments

We thank the dedicated social workers and clinical staff of Fresenius Medical Services for diligently collecting information that forms the basis of the epidemiological studies that we do.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Lower Physical Activity and Depression Are Associated with Hospitalization and Shorter Survival in CKD,” on pages 1669–1670.

References

- 1.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA: Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int 74: 930–936, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drayer RA, Piraino B, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Bernardini J, Shear MK, Rollman BL: Characteristics of depression in hemodialysis patients: Symptoms, quality of life and mortality risk. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 28: 306–312, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, Alleyne S, Cruz I, Veis JH: Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int 57: 2093–2098, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, Goodkin D, Mapes D, Combe C, Piera L, Held P, Gillespie B, Port FK, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) : Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int 62: 199–207, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacson E, Jr, Li NC, Guerra-Dean S, Lazarus M, Hakim R, Finkelstein FO: Depressive symptoms associate with high mortality risk and dialysis withdrawal in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2921–2928, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes AA, Albert JM, Young EW, Satayathum S, Pisoni RL, Andreucci VE, Mapes DL, Mason NA, Fukuhara S, Wikström B, Saito A, Port FK: Screening for depression in hemodialysis patients: Associations with diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in the DOPPS. Kidney Int 66: 2047–2053, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riezebos RK, Nauta K-J, Honig A, Dekker FW, Siegert CE: The association of depressive symptoms with survival in a Dutch cohort of patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 231–236, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan M, Wilfehrt HM, Lacson E, Jr: In data we trust: The role and utility of dialysis provider databases in the policy process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1891–1896, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide, Boston, MA, The Health Institute, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobson AJ: An Introduction to Generalized Linear Models, 2nd Ed., Boca Raton, FL, Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M: Survival Analysis: A Self-Learning Text, 3rd Ed., New York, Springer, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moeschberger ML, Klein JP. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data, New York, Springer, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedayati SS, Grambow SC, Szczech LA, Stechuchak KM, Allen AS, Bosworth HB: Physician-diagnosed depression as a correlate of hospitalizations in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 642–649, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhry SI, McAvay G, Chen S, Whitson H, Newman AB, Krumholz HM, Gill TM: Risk factors for hospital admission among older persons with newly diagnosed heart failure: Findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 61: 635–642, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arneson TJ, Liu J, Qiu Y, Gilbertson DT, Foley RN, Collins AJ: Hospital treatment for fluid overload in the Medicare hemodialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1054–1063, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sensky T, Leger C, Gilmour S: Psychosocial and cognitive factors associated with adherence to dietary and fluid restriction regimens by people on chronic haemodialysis. Psychother Psychosom 65: 36–42, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrera-Guzmán I, Herrera-Abarca JE, Gudayol-Ferré E, Herrera-Guzmán D, Gómez-Carbajal L, Peña-Olvira M, Villuendas-González E, Joan GO: Effects of selective serotonin reuptake and dual serotonergic-noradrenergic reuptake treatments on attention and executive functions in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res 177: 323–329, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agganis BT, Weiner DE, Giang LM, Scott T, Tighiouart H, Griffith JL, Sarnak MJ: Depression and cognitive function in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 704–712, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obialo CI, Hunt W: C., Bashir, K., Zager, P.G. Relationship of missed and shortened hemodialysis treatments to hospitalization and mortality: Observations from a US dialysis network. Clin Kidney J 5: 315–319, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan KE, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW: Adherence barriers to chronic dialysis in the United States [published online ahead of print April 24, 2014]. J Am Soc Nephrol 10.1681/ASN.2013111160 ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL: Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int 75: 1223–1229, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal Asher D, Ver Halen N, Cukor D: Depression and nonadherence predict mortality in hemodialysis treated end-stage renal disease patients. Hemodial Int 16: 387–393, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalil AA, Lennie TA, Frazier SK: Understanding the negative effects of depressive symptoms in patients with ESRD receiving hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 37: 289–295, 308, quiz 296, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossola M, Ciciarelli C, Di Stasio E, Panocchia N, Conte GL, Rosa F, Tortorelli A, Luciani G, Tazza L: Relationship between appetite and symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients on chronic hemodialysis. J Ren Nutr 22: 27–33, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, Robins C, Newman MF: Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: Evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom Med 66: 305–315, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, Sane DC, Finkel MS, Krishnan RR, Atar D, Lekht V, O’Connor CM: Enhanced platelet/endothelial activation in depressed patients with acute coronary syndromes: Evidence from recent clinical trials. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 14: 563–567, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, Atar D, Sane DC, Oshrine BR, Ferguson JJ, O’Connor CM: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors yield additional antiplatelet protection in patients with congestive heart failure treated with antecedent aspirin. Eur J Heart Fail 5: 517–521, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gold PW, Goodwin FK, Chrousos GP: Clinical and biochemical manifestations of depression. Relation to the neurobiology of stress (2). N Engl J Med 319: 413–420, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosmond R, Björntorp P: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity as a predictor of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and stroke. J Intern Med 247: 188–197, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasckow JW, Baker D, Geracioti TD, Jr: Corticotropin-releasing hormone in depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Peptides 22: 845–851, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkins LL, Grossman P: Association of depressive symptoms with reduced baroreflex cardiac control in coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 137: 453–457, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Stein PK, Miller GE, Steinmeyer B, Rich MW, Duntley SP: Heart rate variability and markers of inflammation and coagulation in depressed patients with coronary heart disease. J Psychosom Res 62: 463–467, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes JW, York KM, Li Q, Freedland KE, Carney RM, Sheps DS: Depressive symptoms predict heart rate recovery after exercise treadmill testing in patients with coronary artery disease: Results from the Psychophysiological Investigation of Myocardial Ischemia study. Psychosom Med 70: 456–460, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergström J, Lindholm B, Lacson E, Jr, Owen W, Jr, Lowrie EG, Glassock RJ, Ikizler TA, Wessels FJ, Moldawer LL, Wanner C, Zimmermann J: What are the causes and consequences of the chronic inflammatory state in chronic dialysis patients? Semin Dial 13: 163–175, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlaich MP, Socratous F, Hennebry S, Eikelis N, Lambert EA, Straznicky N, Esler MD, Lambert GW: Sympathetic activation in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 933–939, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baik S-Y, Bowers BJ, Oakley LD, Susman JL: What comprises clinical experience in recognizing depression? The primary care clinician’s perspective. J Am Board Fam Med 21: 200–210, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedayati SS, Finkelstein FO: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 741–752, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaber BL, Lee Y, Collins AJ, Hull AR, Kraus MA, McCarthy J, Miller BW, Spry L, Finkelstein FO, FREEDOM Study Group : Effect of daily hemodialysis on depressive symptoms and postdialysis recovery time: Interim report from the FREEDOM (Following Rehabilitation, Economics and Everyday-Dialysis Outcome Measurements) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 531–539, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duarte PS, Miyazaki MC, Blay SL, Sesso R: Cognitive-behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 76: 414–421, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedayati SS, Yalamanchili V, Finkelstein FO: A practical approach to the treatment of depression in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 81: 247–255, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zalai D, Szeifert L, Novak M: Psychological distress and depression in patients with chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial 25: 428–438, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cukor D, Ver Halen N, Asher DR, Coplan JD, Weedon J, Wyka KE, Saggi SJ, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 196–206, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown ES, Vigil L, Khan DA, Liggin JDM, Carmody TJ, Rush AJ: A randomized trial of citalopram versus placebo in outpatients with asthma and major depressive disorder: A proof of concept study. Biol Psychiatry 58: 865–870, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCool M, Johnstone S, Sledge R, Witten B, Contillo M, Aebel-Groesch K, Hafner J: The promise of symptom-targeted intervention to manage depression in dialysis patients. Nephrol News Issues 25: 32–33, 35–37, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]