Abstract

Electrochemical studies of the oxidation of dodecasubstituted and highly nonplanar nickel porphyrins in a noncoordinating solvent have previously revealed the first nickel(III) porphyrin dication. Herein, we investigate if these nonplanar porphyrins can also be used to detect the so far unobserved copper(III) porphyrin dication. Electrochemical studies of the oxidation of (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu show three processes, the first two of which are macrocycle-centered to give the porphyrin dication followed by a CuII/CuIII process at more positive potential. Support for the assignment of the CuII/CuIII process comes from the linear relationships observed between E1/2 and the third ionization potential of the central metal ions for iron, cobalt, nickel, and copper complexes of (DPP)M and (OETPP)M. In addition, the oxidation behavior of additional nonplanar nickel porphyrins is investigated in a noncoordinating solvent, with nickel meso-tetraalkylporphyrins also being found to form nickel(III) porphyrin dications. Finally, examination of the nickel meso-tetraalkylporphyrins in a coordinating solvent (pyridine) reveals that the first oxidation becomes metal-centered under these conditions, as was previously noted for a range of nominally planar porphyrins.

Short abstract

A series of nickel(II) meso-tetraalkylporphyrins was electrochemically investigated along with nickel(II) and copper(II) derivatives of dodecaphenylporphyrin and octaethyltetraphenylporphyrin. Each investigated porphyrin exhibits three oxidations, the first two of which are macrocycle-centered to give the porphyrin dication followed by an MII/MIII process at more positive potentials.

1. Introduction

Numerous transition-metal porphyrins containing iron, cobalt, nickel, or copper central metal ions have been investigated over the last 50 years as to their electrochemical properties under a variety of solution conditions.1,2 Studies of “simple” metalloporphyrins containing substituted 5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP) or 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octaethylporphyrin (OEP) macrocycles led to a fairly good understanding of the expected redox potentials, separations between redox processes and sites of electron transfer as a function of the porphyrin structure, metal oxidation state, number and type of bound axial ligands, and specific solvent/supporting electrolyte system.3

Simple electrochemical criteria were formulated and utilized many times to suggest the site of electron transfer during studies in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.3 For example, in the case of OEP complexes, the absolute potential difference between the first porphyrin ring-centered oxidation yielding a π-cation radical and the first porphyrin ring-centered reduction yielding a π-anion radical [the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) gap] was said to be 2.25 ± 0.15 V independent of the central metal ion oxidation state,4,5 with the only exception being derivatives of molybdenum and manganese.4,5 A similar HOMO–LUMO gap was seen for TPP complexes.6 The expected potential difference between the first and second ring oxidations of octaethylporphyrins or tetraphenylporphyrins was generally 0.29 ± 0.05 V, while that between the first and second ring reductions was often 0.42 ± 0.05 V.6 These three potential differences were then used as key diagnostic criteria for assigning the site of electron transfer in early studies of OEP- and TPP-type derivatives,3 and the same criteria continue to be used today in many publications reporting the electrochemistry of metalloporphyrins in nonaqueous media.

However, in the 1990s, a large number of nonplanar porphyrins containing copper, iron, cobalt, or nickel central metal ions were synthesized by Smith and co-workers,7−17 and the electrochemical properties of these compounds were then investigated in nonaqueous media.12−15,18,19 These electrochemical studies showed that previously utilized electrochemical diagnostic criteria for assigning the sites of electron transfer might no longer be applicable. For example, the potential separation between the two ring-centered oxidations of many nonplanar nickel(II) porphyrins was often equal to zero in dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) containing 0.1 M tetra-n-butylammonium perchlorate as the supporting electrolyte; i.e., the two one-electron oxidations were overlapped to give an overall two-electron-transfer process in a single step.3,12

The number of redox processes a transition-metal porphyrin will undergo, as well as the site of oxidation and reduction in these compounds, will often vary with the solution conditions used to carry out the electrochemical measurements. For example, in solvents such as CH2Cl2, benzonitrile (PhCN), or tetrahydrofuran, most cobalt(II) porphyrins can be oxidized in three successive one-electron-transfer steps, the first of which unambiguously involves a CoII/CoIII redox process.3,20 However, (TPP)Co and related cobalt(II) porphyrins can also undergo a ring-centered redox process in the first electron abstraction. In coordinating solvents or solvents containing trace water, the first electron is abstracted from the CoII center,3,20 but an initial oxidation at the porphyrin π-ring system was shown to occur for (TPP)Co in a very dry dichloromethane solvent,21 and this was followed by a CoII/CoIII process, either in the second or third of the three observed oxidation processes.

Such changes in the site of electron transfer for oxidation of (TPP)NiII and other nickel(II) porphyrins may also be accomplished by changes in the solvent. For example, the first oxidation is metal-centered in pyridine22,23 and macrocycle-centered in nonbonding or weakly coordinating solvents such as CH2Cl2 or PhCN.3 The potentials for the first two oxidations of (TPP)NiII are very close to each other in some solvent/supporting electrolyte systems,6 and the site of the first electron transfer can be easily shifted from the conjugated π-ring system to the metal or from the metal to the π system by changes in the temperature,24 phenyl ring substituents,25 and/or planarity of the macrocycle.12,22

A third oxidation to give the NiIII dication was expected to occur after formation of the NiII dication radical in noncoordinating solvents, but no more than two oxidation processes were ever reported for any nickel(II) porphyrin until 1993, when it was shown that three successive one-electron oxidations were exhibited by nickel(II) derivatives containing a nonplanar macrocycle such as 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octamethyl-5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrin (OMTPP) or 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octaethyl-5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrin (OETPP),18 the third of which involves the NiII/NiIII process at relatively positive potentials. In a detailed electrochemical study of different nickel(II) porphyrins,12 the potential separation between the first two, ring-centered, oxidations was shown to vary between 0.0 and 400 mV depending on a variety of factors, including the nonplanarity of the macrocycle, the type of π-cation radical, a1u versus a2u, and the ability of anions from the supporting electrolyte to complex with the oxidized species.

The principal goal of the present work is to probe the limits of nonplanar porphyrins in facilitating the detection of MII/MIII processes and to investigate the possibility of observing a copper(II)/copper(III) porphyrin dication redox process, which is expected to occur at more positive potentials than even the NiII/NiIII couple. The CuII/CuIII process has never been experimentally observed but should occur in porphyrins, as it does in the structurely related corroles, which exist in a stable CuIII oxidation state.26−34 Using the nonplanar copper(II) porphyrins, (DPP)Cu9 where DPP = 2,3,5,7,8,10,12,13,15,17,18,20-dodecaphenylporphyrin and (OETPP)Cu,7 we show that nonplanar porphyrin macrocycles can be oxidized in three one-electron-transfer steps, the last of which does indeed involve formation of a copper(III) porphyrin dication at extremely positive potentials.

The paper is divided into three sections. Sections I and II describe studies of the electrochemistry in noncoordinating or coordinating solvents, respectively, of a series of nickel tetraalkyporphyrins (see Chart 1) with varying degrees of nonplanarity. The studies reported in Section I were required because formation of the nickel(III) porphyrin dication has only been reported for a handful of very nonplanar porphyrins, and it was important to confirm that this process can be observed for other easily oxidizable and nonplanar nickel(II) porphyrins. In Section II, the effect of a coordinating solvent on the oxidation processes of nonplanar nickel porphyrins is examined for the first time. It is demonstrated that nonplanar nickel porphyrins in coordinating solvents show a switch to oxidation at the metal center for the first oxidation, as noted previously for nominally planar porphyrins. With the presence of the NiIII dication confirmed for a range of other nickel porphyrins and the effect of coordinating solvents on the NiII/NiIII oxidation clarified, Section III describes investigations of the CuII/CuIII redox processes in (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu.

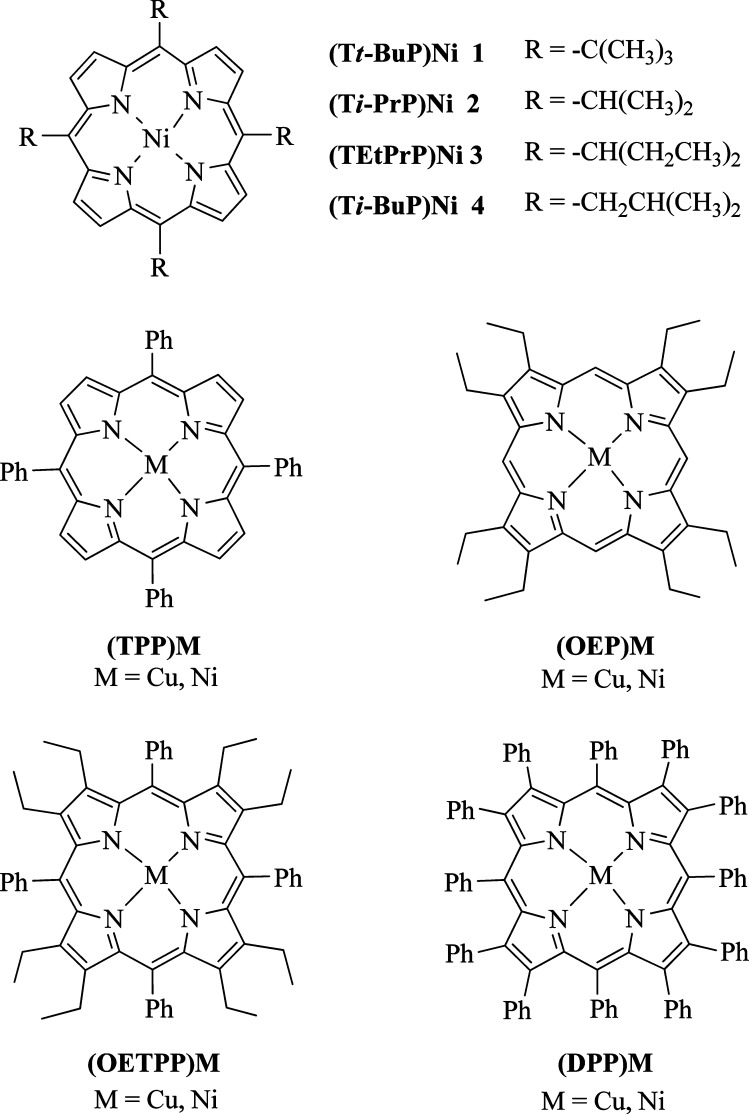

Chart 1. Structures of the Investigated Porphyrins.

2. Experimental Section

Chemicals

Benzonitrile (PhCN), obtained from Fluka Chemika or Aldrich Co., was distilled over phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5) under vacuum prior to use. Absolute dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and pyridine (Py) were received from Aldrich Co. and used as received. High-purity dinitrogen from Trigas was used to deoxygenate the solution before each electrochemical experiment. Tetra-n-butylammonium perchlorate (TBAP) was purchased from Fluka Chemika Co. and used without further purification.

(DPP)Ni,9 (DPP)Cu,9 (OETPP)Ni,7 (OETPP)Cu,7 and nickel(II) tetraalkylporphyrins35,36 were synthesized as described in the literature.

Instrumentation

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed at 298 K on an EG&G model 173 potentiostat coupled with an EG&G model 175 universal programmer in a deaerated PhCN solution containing 0.1 M TBAP as the supporting electrolyte. A three-electrode system composed of a glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum wire counter electrode, and a saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE) was utilized. The reference electrode was separated from the bulk of the solution by a fritted-glass bridge filled with a solvent/supporting electrolyte mixture.

3. Results and Discussion

I. Electrochemistry of Nonplanar Nickel Tetraalkylporphyrins in Noncoordinating Solvents

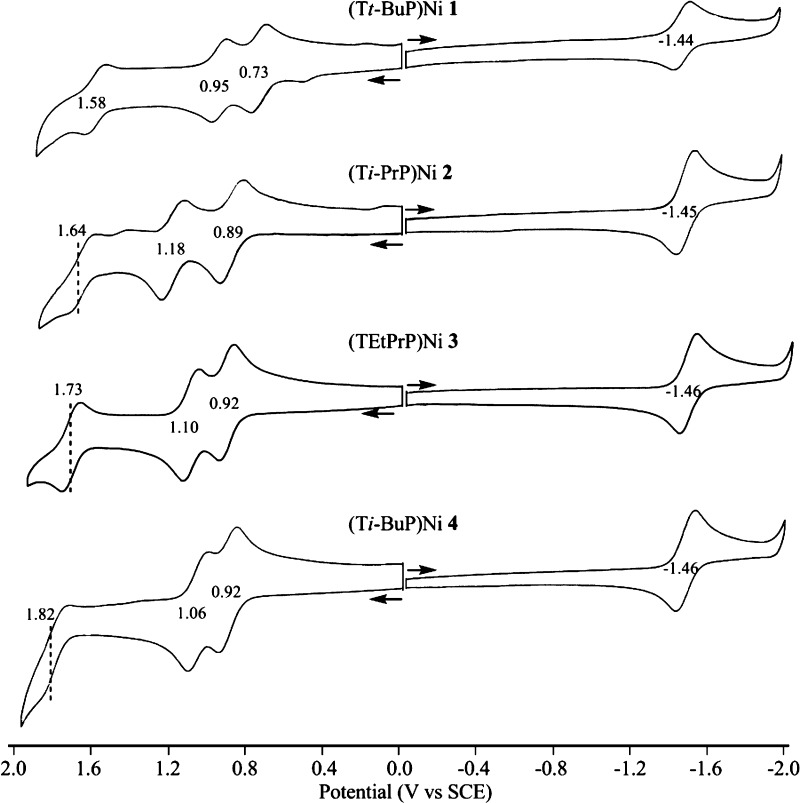

Cyclic voltammograms of the four investigated nickel(II) tetraalkylporphyrins—(Tt-BuP)Ni (1), (Ti-PrP)Ni (2), (TEtPrP)Ni (3), and (Ti-BuP)Ni (4)—are shown in Figure 1. In the solid state, these porphyrins adopt progressively more nonplanar structures because the meso substituents become bulkier on going from primary alkyl groups (4) to secondary alkyl groups (3 and 2) and finally to tertiary alkyl groups (1).35

Figure 1.

Cyclic voltammograms of nickel(II) tetraalkylporphyrins in PhCN containing 0.1 M TBAP. Scan rate = 0.1 V/s.

Compounds 1–3 undergo two one-electron reductions and three one-electron oxidations within the potential range of the solvent (+2.0 to −2.0 V vs SCE). Compound 4 undergoes three oxidations and one reduction, with the second reduction not being observed in PhCN. The first reduction of all four compounds occurs at similar E1/2 values of −1.44 to −1.46 V vs SCE, as seen in Figure 1. The first oxidations of the porphyrins with less bulky primary or secondary alkane substituents (2–4) are also similar to each other (E1/2 = 0.89–0.92 V). This is not the case for the second oxidations of these three derivatives, which follow the order of 4 (1.06 V) < 3 (1.10 V) < 2 (1.18 V). Compound 1 is the most distorted of the four investigated tetraalkylporphyrins, and the first two oxidations are shifted negatively compared to the reactions of compounds 2–4 (by 160–190 mV for the first oxidation and 110–230 mV for the second oxidation). The third (metal-centered) oxidations of compounds 1–4 also vary significantly as a function of the peripheral substituents, with E1/2 values ranging from 1.82 V for 4 to 1.58 V for 1 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Half-Wave Potential (V vs SCE) of Related Nickel and Copper Porphyrins in PhCN and 0.1 M TBAP.

| oxidation |

reduction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | MII/MIII | macrocycle | macrocycle | HOMO–LUMO gap | ||

| 1 | 1.58 | 0.95 | 0.73 | –1.44 | –1.93 | 2.17 |

| 2 | 1.64 | 1.18 | 0.89 | –1.45 | –1.95 | 2.34 |

| 3 | 1.73 | 1.10 | 0.92 | –1.46 | –1.95 | 2.38 |

| 4 | 1.82 | 1.06 | 0.92 | –1.46 | 2.38 | |

| (OMTPP)Nid | 1.63 | 0.90 | 0.74 | –1.48 | –1.80 | 2.22 |

| (TC6TPP)Nid | 1.56 | 0.90 | 0.73 | –1.50 | –1.83 | 2.23 |

| (OETPP)Ni | 1.70 | 0.78 | 0.78 | –1.51 | –1.83 | 2.29 |

| (DPP)Ni | 1.64 | 0.84 | 0.84 | –1.24 | –1.67 | 2.08 |

| (TPP)Ni | 1.83 | 1.13 | 1.13 | –1.26 | 2.39 | |

| (OEP)Ni5,18 | 1.88 | 1.21 | 0.78 | –1.37 | 2.15 | |

| (OETPP)Cu | 2.00a | 0.97 | 0.46 | –1.46 | –1.90 | 1.92 |

| (DPP)Cu | 1.88 | 0.94 | 0.54 | –1.22 | –1.61 | 1.76 |

| (TPP)Cu | (2.47)c | 1.33 | 1.03 | –1.26 | –1.72 | 2.29 |

| (OEP)Cub | 1.2537 | 0.7537 | –1.4638 | 2.21 | ||

The overall oxidative behavior of the strongly ruffled porphyrin 1 closely resembles that which was previously described for the strongly saddled porphyrins,18 (OMTPP)NiII and (TC6PP)NiII (where OMTPP = dianion of 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octamethyl-5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrin and TC6PP = 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-tetracyclohexenyl-5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrin) in the same solvent (PhCN). All three porphyrins are oxidized at experimentally identical potentials of 0.73–0.74 V, and all three porphyrins also have very similar E1/2 values for the second and third redox processes. This is true despite differences in both the alkyl and aryl meso substituents on the macrocycles of 1, (OMTPP)Ni and (TC6TPP)Ni, and in the type of nonplanar structure (ruffled for 1(35) versus saddled for the other two compounds7,39).

Previous studies of porphyrin substituent effects have shown that changes in E1/2 are influenced by the electronic effect of the substituents on the meso- and β-pyrrole positions of the macrocycle3 as well as by conformational distortion of the macrocycle induced by crowding at the porphyrin periphery through peri interactions.12 For instance, (OETPP)Ni is substantially easier to oxidize than (TPP)Ni (see Table 1) because of its saddle conformation and yields a complex postulated as a high-spin NiII π-cation radical.22 The more facile macrocycle oxidation of 1 compared to 2, 3, or 4 is consistent with the strongly ruffled macrocycle of 1 that results from steric clashes between the substituents (t-Bu) and the adjacent pyrrole rings.40,41

The potential difference (ΔE1/2) between the first two oxidations of the tetraaryl-substituted porphyrins ranges from 140 to 290 mV and follows the order: 4 (140 mV) < 3 (180 mV) < 1 (220 mV) < 2 (290 mV). There is no apparent correlation with nonplanarity of the porphyrin macrocycle. This suggests that other factors contribute to the ΔE1/2 differences between the first two oxidations, such as the type of dication formed (a1u vs a2u) or the anion binding affinity of the dication.12 Interestingly, however, the reversible metal-centered NiII/NiIII reactions of 1–4 can be seen to shift to more positive potentials with increased nonplanar deformation (1.82 V for 4 vs 1.58 V for 1). Given the similar electron-donating/withdrawing effects of the substituents (as shown by the identical reduction potentials for 1–4), this may suggest an effect of nonplanarity on the NiII/NiIII reactions.

II. Effect of the Solvent on the NiII/NiIII Processes in Nonplanar Nickel Tetraalkylporphyrins

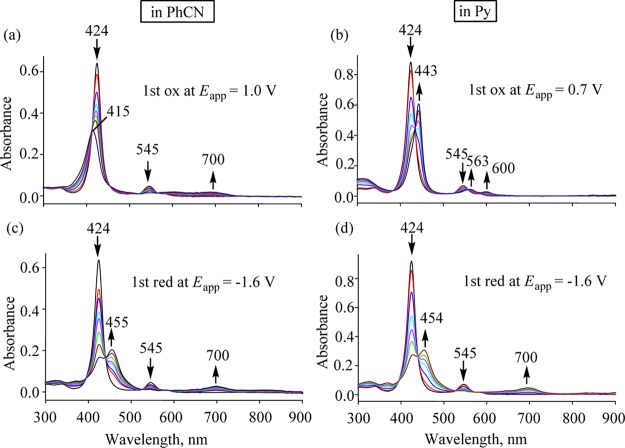

As discussed above, the NiII/NiIII process is observed only after the two one-electron ring-centered abstractions in PhCN. The first one-electron oxidation leads to a NiII π-cation radical whose UV–visible spectrum exhibits a decreased intensity Soret band and a broad band in the visible region of the spectrum. The same types of spectral changes are seen for all four tetraalkylporphyrins in PhCN, an example of which is shown in Figure 2a for 3 during controlled-potential oxidation at 1.0 V in a thin-layer cell.

Figure 2.

UV–visible spectral changes of 3 upon the (a) first oxidation in PhCN, (b) first oxidation on Py, (c) first reduction in PhCN, and (d) first reduction in Py containing 0.1 M TBAP.

As earlier demonstrated for other nickel(II) porphyrins,23 the site for the first oxidation of 3 is quite different when the reaction is carried out in Py because this solvent coordinates to the singly oxidized form of the compound. Under these conditions, the Soret band of neutral 3 at 424 nm decreases in intensity, while a new well-defined Soret band grows in at 443 nm for the singly oxidized species (see Figure 2b). At the same time, the Q band of NiII at 545 nm disappears, and two well-defined new Q bands grow in at 563 and 600 nm. There is no broad band between 600 and 700 nm, indicating the lack of a π-cation radical. This type of spectral change suggests that oxidation in Py has occurred at the central metal ion rather than at the porphyrin macrocycle. Singly oxidized 1, 2, and 4 exhibit spectral changes similar to those of 3 in Py. A summary of the UV–visible bands for the neutral and singly oxidized tetraalkylporphyrins in these two solvents is given in Table 2. The shift in the site of electron transfer upon a change of the solvent from PhCN to Py has been well documented in the literature23 and is due to coordination of Py to the singly oxidized form of the porphyrin.

Table 2. Absorption Maxima (λmax, nm) of Nickel Tetraalkylporphyrins and Their Singly Oxidized Products in PhCN and Py Containing 0.1 M TBAP.

| in PhCN |

in Py |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TRP)NiII |

[(TRP)NiII]+ |

(TRP)NiII |

[(TRP)NiIII (Py)2]+ |

|||||

| compound | Soret | visible | Soret | vsible | Soret | visible | Soret | visible |

| 1 | 455 | 584, 622 | 422 | 778 | 452 | 583, 625 | 469 | 596, 646 |

| 2 | 426 | 550, 583 | 413 | 689 | 424 | 548, 589 | 445 | 571, 608 |

| 3 | 424 | 545, 583 | 415 | 700 | 424 | 545, 584 | 443 | 563, 600 |

| 4 | 421 | 539, 582 | 411 | 688 | 421 | 542, 582 | 441 | 560, 601 |

Examples of the UV–visible spectral changes for the reduction of 3 in the two solvents are provided in Figure 2c,d. It should be noted that almost exactly the same UV–visible spectral changes are seen upon reduction of all four tetraalkylporphyrins whether the solvent is PhCN or Py.

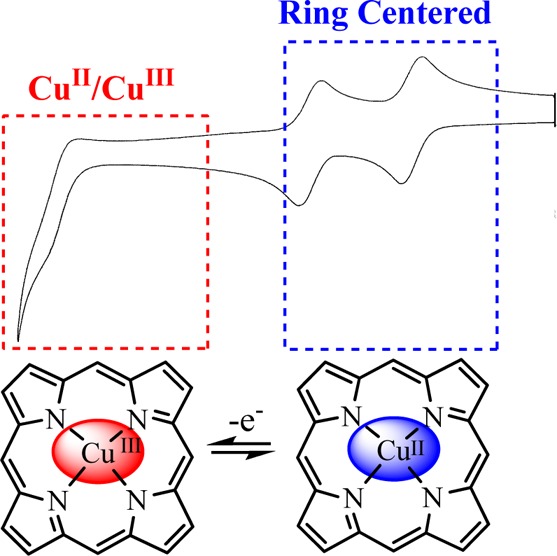

III. Generation of the CuIII Dication for Highly Nonplanar (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu

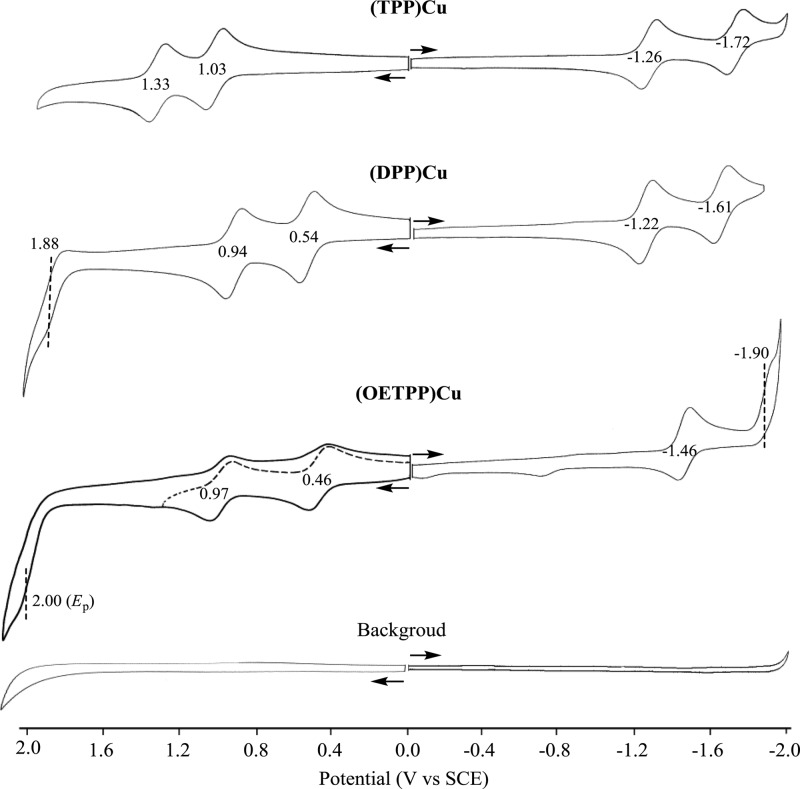

The electrochemistry of (TPP)Cu, (DPP)Cu, and (OETPP)Cu was also investigated, and cyclic voltammograms of these three compounds in PhCN containing 0.1 M TBAP are shown in Figure 3. Two reductions are observed for each porphyrin, as expected, and two oxidations are also seen for (TPP)Cu. Surprisingly, three oxidation processes are seen for (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu, the latter of which has never before been reported.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of (TPP)Cu, (DPP)Cu, (OETPP)Cu, and solvent background in PhCN containing 0.1 M TBAP. Scan rate = 0.1 V/s.

All four redox processes of (TPP)Cu are assigned as macrocycle-centered electron transfers to give a porphyrin π-anion radical and dianion upon reduction and a porphyrin π-cation radical and dication upon oxidation.3 The first two reductions and first two oxidations of (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu are also centered at the conjugated π-ring system of the porphyrin, with half-wave potentials for oxidation being shifted negatively by about 500 mV compared to (TPP)Cu due to the nonplanarity of these two macrocycles (see the exact E1/2 values in Table 1).

The third oxidation of (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu might at first be rationalized in terms of a solvent impurity or perhaps by formation of an isoporphyrin. However, the utilized solvent background is “clean” until beyond 2.00 V vs SCE (see Figure 3), and there is no evidence for coupled chemical reactions and formation of an isoporphyrin, as indicated by variable scan rate measurements, low-temperature measurements, and multiple measurements on the same compounds taken with different batches of solvent. Thus, a more likely interpretation would be a metal-centered oxidation, as observed for the nickel porphyrins described in detail above.

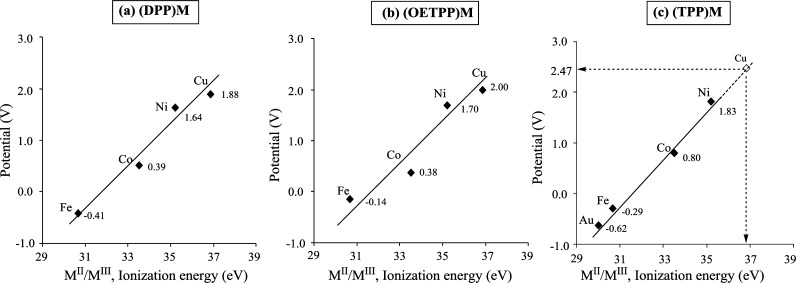

The conversion of CuII to CuIII in the third oxidation of (DPP)Cu and (OETPP)Cu is also strongly suggested by a comparison of the measured E1/2 values for this process with redox potentials for the MII/III reaction of other transition-metal porphyrins that have the same macrocycles, namely, (DPP)MII and (OETPP)MII, where M = Fe, Co, and Ni. One might expect to see a linear relationship between the third ionization potential of the central metal ion and E1/2 for the MII/MIII processes of the (DPP)M and (OETPP)M complexes, and this is exactly what is observed.

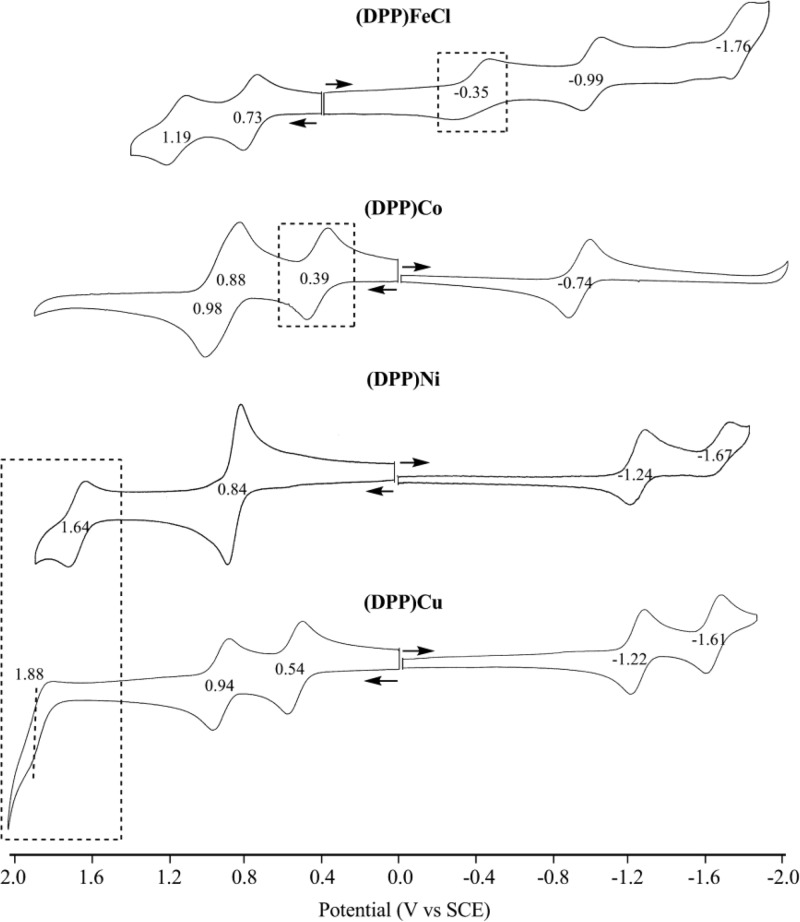

Examples of cyclic voltammograms are shown in Figure 4 for the (DPP)MII derivatives containing Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu, while plots of the measured E1/2 values for the MII/MIII reaction of the four porphyrins versus the third ionization potential of the central metal are shown in Figure 5a for (DPP)MII and in Figure 5b for (OETPP)MII. Linear relationships are observed for both series of compounds using the third ionization potential42 of the central metal ion (in eV) and newly measured E1/2 values of the earlier characterized Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu derivatives of (DPP)M and (OETPP)M in PhCN. A third oxidation is not observed for (TPP)Cu under the same solution conditions, but extrapolation of the linear relationship in Figure 5c for (TPP)MII, where M = Au, Fe, Co, and Ni, to the third ionization potential of CuII gives a predicted half-wave potential of 2.47 V for the CuII/CuIII process of (TPP)Cu in PhCN. This third oxidation cannot be observed experimentally because of the positive potential limit of the solvent.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of (DPP)M in PhCN containing 0.1 M TBAP where M = FeIII, CoII, NiII, and CuII. Scan rate = 0.1 V/s. The MII/MIII processes are “boxed” in the figure.

Figure 5.

Correlation between gas-phase ionization energies for MII/MIII and MII/MIII redox processes of (a) (DPP)M, (b) (OETPP)M, and (c) (TPP)M in PhCN containing 0.1 M TBAP (see Table 1 for potential). The ionization energies are taken from ref (42). The CuII/CuIII process of (TPP)Cu is predicted to occur at 2.47 V based on the correlation in part c.

The data in Figures 3 and 5 suggest that a CuII/CuIII process should be observed for other copper porphyrins under solution conditions where more positive potentials might be accessible. This possibility will be investigated in future studies with different solvent/supporting electrolyte combinations.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Robert A. Welch Foundation (Grant E-680 to K.M.K.), the Science Foundation of Ireland (P.I. 09/IN.1/B2650), and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Grant CA132861 to K.M.S.). C.J.M. acknowledges a 2013 Investigador Award from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Kadish K. M.; Smith K. M.; Guilard R.. The Porphyrin Handbook; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2000. –2003; Vols. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Smith K. M.; Guilard R.. Handbook of Porphyrin Science; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. –2014; Vols. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; Royal G. In The Porphyrin Handbook; Kadish K. M., Smith K. M., Guilard R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2000; Vol. 8, pp 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Davis D. G.; Fuhrhop J.-H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1972, 11, 1014–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrhop J.-H.; Kadish K. M.; Davis D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 5140–5147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Royal G.; Van Caemelbecke E.; Gueletti L. In The Porphyrin Handbook; Kadish K. M., Smith K. M., Guilard R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2000; Vol. 9, pp 1–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks L. D.; Medforth C. J.; Park M. S.; Chamberlain J. R.; Ondrias M. R.; Senge M. O.; Smith K. M.; Shelnutt J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura H.; Yatsunyk L.; Medforth C. J.; Smith K. M.; Barkigia K. M.; Renner M. W.; Melamed D.; Walker F. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6564–6578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medforth C. J.; Senge M. O.; Smith K. M.; Sparks L. D.; Shelnutt J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 9859–9869. [Google Scholar]

- Shelnutt J. A.; Medforth C. J.; Berber M. D.; Barkigia K. M.; Smith K. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4077–4087. [Google Scholar]

- Senge M. O. Chem. Commun. 2006, 243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Lin M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; De Stefano G.; Medforth C. J.; Nurco D. J.; Nelson N. Y.; Krattinger B.; Muzzi C. M.; Jaquinod L.; Xu Y.; Shyr D. C.; Smith K. M.; Shelnutt J. A. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 6673–6687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; D’Souza F.; Medforth C. J.; Smith K. M.; Tabard A.; Guilard R. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 2984–2989. [Google Scholar]

- Guilard R.; Perie K.; Barbe J.-M.; Nurco D. J.; Smith K. M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; Kadish K. M. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 973–981. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; D’Souza F.; Lin M.; Nurco D. J.; Medforth C. J.; Forsyth T. P.; Krattinger B.; Smith K. M.; Fukuzumi S.; Nakanishi I.; Shelnutt J. A. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 2188–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Haddad R. E.; Jia S.-L.; Hok S.; Olmstead M. M.; Nurco D. J.; Schore N. E.; Zhang J.; Ma J.-G.; Smith K. M.; Gazeau S.; Pecaut J.; Marchon J.-C.; Medforth C. J.; Shelnutt J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1179–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelnutt J. A.; Song X.-Z.; Ma J.-G.; Jia S.-L.; Jentzen W.; Medforth C. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; Boulas P.; D’Souza F.; Vogel E.; Kisters M.; Medforth C. J.; Smith K. M. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 4177–4178. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Van Caemelbecke E.; D’Souza F.; Medforth C. J.; Smith K. M.; Tabard A.; Guilard R. Organometallics 1993, 12, 2411–2413. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Li J.; Van Caemelbecke E.; Ou Z.; Guo N.; Autret M.; D’Souza F.; Tagliatesta P. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36, 6292–6298. [Google Scholar]

- Sandusky P. O.; Salehi A.; Chang C. K.; Babcock G. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6437–6439. [Google Scholar]

- Renner M. W.; Barkigia K. M.; Melamed D.; Gisselbrecht J.-P.; Nelson N. Y.; Smith K. M.; Fajer J. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2002, 28, 741–759. [Google Scholar]

- Seth J.; Palaniappan V.; Bocian D. F. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 2201–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. C.; Niem T.; Dolphin D. Can. J. Chem. 1978, 56, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Kadish K. M.; Morrison M. M. Inorg. Chem. 1976, 15, 980–982. [Google Scholar]

- Guilard R.; Gros C. P.; Barbe J.-M.; Espinosa E.; Jerome F.; Tabard A.; Latour J.-M.; Shao J.; Ou Z.; Kadish K. M. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 7441–7455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Z.; Shao J.; Zhao H.; Ohkubo K.; Wasbotten I. H.; Fukuzumi S.; Ghosh A.; Kadish K. M. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2004, 8, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. P.; Ramdhanie B.; Zareba A. A.; Czernuszewicz R. S.; Goldberg D. P. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 6600–6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luobeznova I.; Simkhovich L.; Goldberg I.; Gross Z. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 1724–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Tangen E.; Ghosh A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8117–8121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasbotten I. H.; Wondimagegn T.; Ghosh A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8104–8116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A.; Wondimagegn T.; Parusel A. B. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 5100–5104. [Google Scholar]

- Will S.; Lex J.; Vogel E.; Schmickler H.; Gisselbrecht J.-P.; Haubtmann C.; Bernard M.; Gross M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 357–361. [Google Scholar]

- Paolesse R. In The Porphyrin Handbook; Kadish K. M., Smith K. M., Guilard R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2000; Vol. 2, pp 201–232. [Google Scholar]

- Senge M. O.; Bischoff I.; Nelson N. Y.; Smith K. M. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 1999, 3, 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ema T.; Senge M. O.; Nelson N. Y.; Ogoshi H.; Smith K. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 106, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenberg A. M.; Schussel L. J. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 3205–3213. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. K.; Barkigia K. M.; Hanson L. K.; Fajer J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 1352–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Barkigia K. M.; Renner M. W.; Furenlid L. R.; Medforth C. J.; Smith K. M.; Fajer J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3627–3635. [Google Scholar]

- Senge M. O.; Ema T.; Smith K. M. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1995, 733–734. [Google Scholar]

- Jentzen W.; Simpson M. C.; Hobbs J. D.; Song X.; Ema T.; Nelson N. Y.; Medforth C. J.; Smith K. M.; Veyrat M.; Mazzanti M.; Ramasseul R.; Marchon J.-C.; Takeuchi T.; Goddard W. A. III; Shelnutt J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11085–11097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lide D. R.Chemical Rubber Company Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 79th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1998. [Google Scholar]