Abstract

Multidrug-resistant pathogens have become a major public health concern. There is a great need for the development of novel antibiotics with alternative mechanisms of action for the treatment of life-threatening bacterial infections. Antimicrobial peptides, a major class of antibacterial agents, share amphiphilicity and cationic structural properties with cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs). Herein, several amphiphilic cyclic CPPs and their analogues were synthesized and exhibited potent antibacterial activities against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Among all the peptides, cyclic peptide [R4W4] (1) showed the most potent antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA, exhibiting a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2.67 μg/mL]. Cyclic [R4W4] and the linear counterpart R4W4 exhibited MIC values of 42.8 and 21.7 μg/mL, respectively, against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In eukaryotic cells, peptide 1 exhibited the expected cell penetrating properties and showed >84% cell viability at a concentration of 15 μM (20.5 μg/mL) in three different human cell lines. Twenty-four hour time-kill studies evaluating [R4W4] with 2 times the MIC in combination with tetracycline demonstrated bactericidal activity at 4 and 8 times the MIC of tetracycline against MRSA (MIC = 0.5 μg/mL) and 2–8 times the MIC against Escherichia coli (MIC = 2 μg/mL). This study suggests that when amphiphilic cyclic CPPs are used in combination with an antibiotic such as tetracycline, they provide significant benefit against multidrug-resistant pathogens when compared with the antibiotic alone.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptide, cell-penetrating peptide, combination, drug delivery, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

The emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) threatens public health worldwide. Despite a half century of efforts to find effective treatments, healthcare practitioners are still challenged to cure infections caused by MRSA.1 MRSA is widespread in hospitals, and community-associated MRSA has continued to emerge since the mid-1990s.2 In 2009, 463017 infections were attributed to MRSA, which corresponds to 11.74 infections per 1000 hospitalizations in the United States.3 Approximately 19000 human deaths were attributed to invasive MRSA in 2005.4 Moreover, MRSA rapidly evolves resistance against new commercial antibiotics.

Currently, vancomycin is the first-line therapy for the treatment of MRSA. However, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus has been reported in 2002.5 Daptomycin is a cyclic lipopeptide having a broad spectrum against Gram-positive bacteria, and it shows rapid antibacterial responses. Its novel mechanism of action involves membrane depolarization resulting in efflux of potassium ions, followed by bacterial cell death.6 Despite the novelty of its mechanism, daptomycin resistance in MRSA was reported in 2005, only two years after FDA approval. The resistance mechanism against daptomycin remains to be determined.7

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli are Gram-negative bacteria. P. aeruginosa has the ability to develop multidrug resistance, and it has shown rapid development of resistance against several classes of antibiotics.8E. coli has also shown antimicrobial resistance against drugs that have been used for a long time.9,10 Thus, new classes of antibiotics with different modes of action are urgently needed for these Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have emerged as alternative therapeutics against antibiotic-resistant pathogens because they can act as effectors and regulators of the immune system as well as inhibitors of bacterial cell growth.11 Cationic AMPs target negatively charged bacterial membrane lipids, which may reduce the frequency of bacterial resistance.12 AMPs have been found to be host defense peptides in various organisms, including insects, amphibians, and mammals.13,14 AMPs such as pexiganan and omiganan are in clinical trials or in development.15

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are short hydrophilic and/or amphiphilic peptides. Because of their ability to translocate across the eukaryotic cell membrane, they have been studied as molecular vehicles for delivering other drugs intracellularly.16,17 Some AMPs and CPPs share similar physical properties, such as amphiphilicity and cationic properties. Thus, CPPs have potential application as AMPs with dual actions as both antibiotics and possible molecular transporter properties.

We have synthesized and evaluated several cyclic CPPs as molecular transporters of other cargo drugs. For example, we recently reported that synthetic cyclic peptides [WR]4 and [WR]5 enhanced the cellular uptake of phosphopeptides, doxorubicin, and anti-HIV drugs.18 These peptides are expected to be more stable than linear peptides toward human serum because the cyclization decreases the rate of proteolytic degradation as shown for other cyclic peptides.19 It has been previously reported that the rigidity in the peptides can enhance the cell penetrating property.20 According to our recent study, the acylation and cyclization of short polyarginine peptides enhance the intracellular delivery of cell-impermeable phosphopeptides.21

In general, AMPs contain hydrophobic and hydrophilic portions that interact with the lipid part and hydrophilic negatively charged heads in bacterial membranes, respectively. Many linear AMPs adopt amphipathic α-helical conformations with the hydrophobic side chains arranged along one side of the helical structure and the hydrophilic side chains organized on the opposite side. This arrangement results in the ideal amphipathic helical structures.22 Some AMPs form an amphipathic β-sheet conformation to interact with cell membranes.22 We hypothesized that amphiphilic cyclic peptides with cell penetrating properties can have potential antibacterial and synergistic activity with other antibiotics. Herein, we report two classes of amphiphilic cyclic CPPs: (a) cyclic peptides containing tryptophan and arginine amino acids and (b) fatty acylated cyclic polyarginine peptides (ACPPs). The antimicrobial activities of synthesized peptides were evaluated against multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens alone or in combination with tetracycline in time-kill studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of using an antimicrobial cyclic CPP in combination with an antibiotic for generating bactericidal activities.

Experimental Section

Peptide Design and Synthesis

The peptides were synthesized by Fmoc/tBu solid-phase peptide synthesis. Single-amino acid (tryptophan or arginine) preloaded trityl resins were employed for the synthesis of cyclic peptides. Fmoc-l-amino acid building blocks were coupled to the resin using the 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Fmoc protecting groups were removed by treatment with 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF after each coupling. The side chain-protected peptides were detached from the resin by a 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE)/acetic acid/dichloromethane (DCM) mixture [2:1:7 (v/v/v)] and cyclized using 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAT) and N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) in an anhydrous DMF/DCM mixture. Then all protecting groups were removed with a trifluoroacetic acid/thioanisole/1,2-ethanedithiol/anisole mixture [90:5:3:2 (v/v/v/v)], and crude peptides were collected by precipitation with cold diethyl ether. The crude cyclic peptides were purified by a reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) system using a preparative Phenomenex Gemini C18 column (10 μm, 250 mm × 21.2 mm) with a gradient from 0 to 100% acetonitrile (CH3CN) containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA and water containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA for 1 h with a flow rate of 15.0 mL/min at a wavelength of 214 nm.

As a representative example, the synthesis of peptide 1 ([R4W4]) is described here. After H-Trp(Boc)-2-chlorotrityl resin (449 mg, 0.35 mmol, 0.78 mmol/g) had been swollen in DMF for 40 min by N2, three consecutive couplings of Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH (553 mg, 1.05 mmol, 3 equiv) with the resin were conducted using HBTU (398 mg, 1.05 mmol, 3 equiv), HOBT (142 mg, 1.05 mmol, 3 equiv), and DIPEA (366 μL, 2.1 mmol, 6 equiv) in DMF (15 mL). In each coupling step, the mixture of resin and reaction solution was agitated using N2 for 1 h. Piperidine in DMF [20% (v/v)] was used to remove the Fmoc group after each coupling. The subsequent Fmoc-Arg(pbf)-OH (681 mg, 1.05 mmol, 3 equiv) coupling was conducted four times in a similar manner. The linear peptide with a protected side chain was cleaved from the resin in the presence of a TFE/acetic acid/DCM mixture [2:1:7 (v/v/v)] for 1 h. After evaporation and overnight drying of the filtrate in a vacuum, the cyclization was conducted under a dilute condition. The linear peptide was dissolved in an anhydrous DMF/DCM mixture [5:3 (v/v), 250 mL]. HOAT (190 mg, 1.4 mmol, 4 equiv) and DIC (240 μL, 1.54 mmol, 4.4 equiv) were added to the solution. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. Then, the solvent was evaporated. Reagent “R”, a trifluoroacetic acid/thioanisole/1,2-ethanedithiol/anisole mixture [90:5:3:2 (v/v/v/v)], was added, and the solution was mixed for 2 h to remove side chain protecting groups. The crude peptide 1 was precipitated and washed with cold diethyl ether and purified by a preparative RP-HPLC system as described above.

The peptide structures were confirmed by an AXIMA performance matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) spectrometer. The sequences of 14 synthesized peptides are listed in Table 1. Fluorescein-labeled peptide 1 (F′-[KR4W4]) was synthesized by conjugation of a cyclic peptide (β-Ala)-[KR4W4] and 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein N-hydroxysuccinimide ester in the solution phase. A cyclic peptide (β-Ala)-[KR4W4] was synthesized using the same protocol described above but with Dde-Lys(Fmoc)-OH added for attachment of Boc-β-Ala-OH on the side chain of lysine.

Table 1. Synthesized Peptides Used for Antimicrobial Activity.

| peptide | peptide sequence | abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | [RRRRWWWW] | [R4W4] |

| 2 | RRRRWWWW-COOH | R4W4 |

| 3 | [RRRRWWW] | [R4W3] |

| 4 | RRRRWWW-COOH | R4W3 |

| 5 | [EEEEWWWW] | [E4W4] |

| 6 | [EEEEWWW] | [E4W3] |

| 7 | [KRRRRR] | [KR5] |

| 8 | octanoyl-[KRRRRR] | C8-[R5] |

| 9 | dodecanoyl-[KRRRRR] | C12-[R5] |

| 10 | hexadecanoyl-[KRRRRR] | C16-[R5] |

| 11 | N-acetyl-l-tryptophanyl-12-aminododecanoyl-[KRRRRR] | W-C12-[R5] |

| 12 | N-acetyl-WWWW-[KRRRRR] | W4-[R5] |

| 13 | dodecanoyl-[KRRRRRR] | C12-[R6] |

| 14 | dodecanoyl-KRRRRR-COOH | C12-(R5) |

[RRRRWWWW] (1): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C68H88N24O8 calcd 1368.7217; found 1369.6412 [M + H]+. RRRRWWWW-COOH (2): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C68H90N24O9 calcd 1386.7323; found 1387.3780 [M + H]+. [RRRRWWW] (3): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C57H78N22O7 calcd 1182.6424; found 1183.5685 [M + H]+. RRRRWWW-COOH (4): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C57H80N22O8 calcd 1200.6529; found 1201.5652 [M + H]+. [EEEEWWWW] (5): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C64H68N12O16 calcd 1260.4876; found 1261.3981 [M + H]+, 1283.4336 [M + Na]+, 1299.4365 [M + K]+. [EEEEWWW] (6): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C53H58N10O15 calcd 1074.4083; found 1075.4027 [M + H]+, 1113.4099 [M + K]+. [KRRRRR] (7): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C36H72N22O6 calcd 908.6005; found 909.6772 [M + H]+. Dodecanoyl-[KRRRRR] (8): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C44H86N22O7 calcd 1034.7050; found 1035.7084 [M + H]+. Dodecanoyl-[KRRRRR] (9): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C48H94N22O7 calcd 1090.7676; found 1091.7576 [M + H]+. Hexadecanoyl-[KRRRRR] (10): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C52H102N22O7 calcd 1146.8302; found 1147.8404 [M + H]+. N-Acetyl-l-tryptophanyl-12-aminododecanoyl-[KRRRRR] (11): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C61H107N25O9 calcd 1333.8684; found 1334.8713 [M + H]+. N-Acetyl-WWWW-[KRRRRR] (12): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C82H114N30O11 calcd 1694.9283; found 1696.3111 [M + H]+. Dodecanoyl-[KRRRRRR] (13): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C54H106N26O8 calcd 1246.8687; found 1247.7397 [M + H]+. Dodecanoyl-KRRRRR-COOH (14): MALDI-TOF (m/z) C48H96N22O8 calcd 1108.7781; found 1109.7308 [M + H]+.

F′-[KR4W4]

Fluorescein-labeled peptide F′-[KR4W4] was synthesized using the same protocol, with the exception that a lysine residue was added to attach a fluorescein. First, (β-Ala)-[KR4W4] was synthesized on a 0.10 mmol scale. H-Trp(Boc)-2-chlorotrityl resin (128 mg, 0.10 mmol, 0.78 mmol/g), Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH (158 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv), Fmoc-Arg(pbf)-OH (195 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv), Dde-Lys(Fmoc)-OH (160 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv), and Boc-β-Ala-OH (57 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv) were used to couple each building block to the resin using HBTU (114 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv), HOBT (41 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv), and DIPEA (105 μL, 0.60 mmol, 6 equiv) in DMF. The Dde protecting group was removed with 2% hydrazine in DMF, and the side chain-protected linear peptides were cleaved from the resin using a TFE/acetic acid/DCM mixture [2:1:7 (v/v/v)]. The subsequent cyclization and purification steps were the same as those described above.

The (β-Ala)-[KR4W4] peptide (8.00 mg, 5.10 μmol) and 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FAM-NHS, 3.14 mg, 6.63 μmol, 1.3 equiv) were coupled using PyAOP (3.46 mg, 6.63 μmol, 1.3 equiv) and DIPEA (8.9 μL, 51.0 μmol, 10 equiv) in anhydrous DMF (200 μL) and a few drops of anhydrous DCM. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3.5 h under N2. After evaporation of the solvent, the residue was purified using a preparative RP-HPLC system using the same condition described above. After removal of the Dde protecting group with 2% hydrazine in DMF and washing with DMF and DCM, the side chain-protected fluorescein linear peptides were cleaved from the resin using a TFE/acetic acid/DCM mixture [2:1:7 (v/v/v)]. The subsequent cyclization and purification steps were described above. F′-[KW4R4]: MALDI-TOF (m/z) C98H115N27O16 calcd 1925.9015; found 1926.8654 [M + H]+.

Bacterial Strains

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA, ATCC 43300), P. aeruginosa (PAO1), and E. coli (ATCC 35218) were employed for antimicrobial activities of peptides alone and in combination with tetracycline.

Antibacterial Activities against MRSA and P. aeruginosa

MRSA and P. aeruginosa were inoculated into tryptic soy broth (TSB, BD) at 37 °C and shaken at 175 rpm overnight. The cultured suspension [1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL] was immediately diluted to 1 × 105 CFU/mL. All 14 peptides were dissolved in distilled water (except for peptides 5 and 6, which were dissolved in 50 mM NH4HCO3 to improve the solubility) to make 5 mM solutions. Tetracycline and tobramycin were used as positive controls and prepared as 0.10 and 0.094 mg/mL solutions, respectively. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using the broth microdilution method.23 Briefly, in a 96-well microtiter plate, all tested peptides and controls were mixed well with a bacterial suspension [1:39 (v/v)]. After a series of 2-fold dilutions, the microtiter plates were then incubated statically at 37 °C overnight. MICs were determined as the minimal concentration at which no visible bacterial growth was present. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Time-Kill Studies

Time-kill studies were performed using MRSA (ATCC 43300) and E. coli (ATCC 35218). Strains were incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h on tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco, Becton Dickinson Co., Sparks, MD), and a McFarland standard was diluted in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) (Becton Dickinson Co.) supplemented with 25 mg/L calcium and 12.5 mg/L magnesium, to a final concentration of ∼5.5 log10 CFU/mL.24 Peptide 1 ([R4W4]) and tetracycline were evaluated at 1, 2, 4, and 8 times their respective MICs. Peptide 1 at 2 times the MIC was also combined with tetracycline at 1, 2, 4, and 8 times the MIC to evaluate synergy, defined as >2 log10 CFU/mL reduction over the most active agent alone. Each bacterial–antimicrobial combination was run in triplicate. Runs in the absence of antimicrobials ensured adequate growth of the organisms in the model. Each culture was incubated in a shaking incubator (Excella E24, New Brunswick Scientific, Enfield, CT) at 37 °C for an additional 24 h. Samples were taken at 0, 4, and 24 h, serially diluted, and plated on TSA for colony count enumeration, where the limit of detection was 2.0 log10 CFU/mL.24 Bactericidal activity (99.9% kill) was defined as a ≥3 log10 CFU/mL reduction at 24 h in colony count from the initial inoculum. Bacteriostatic activity was defined as a <3 log10 CFU/mL reduction.

Cellular Cytotoxicity Assays

MTS proliferation assays were conducted against three cell lines (human ovarian adenocarcinoma SK-OV-3, human leukemia CCRF-CEM, and human embryonic kidney HEK 293T). Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells for SK-OV-3, 1 × 105 cells for CCRF-CEM, and 1 × 104 cells for HEK 293T) and incubated with 100 μL of complete medium overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Various concentrations (0–600 μM) of the peptide solution (20 μL) were added to cells to yield the final concentrations of peptide (0–100 μM). The cells were kept in an incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) for 24 h. Then a CellTiter 96 aqueous solution (20 μL) was added to each well and incubated for 1–4 h under the same condition. The absorbance was obtained at 490 nm using a microplate reader to detect the formazan product. Wells containing cells in the absence of any peptide were used as a control.

Cellular Uptake of Fluorescein-Labeled Peptide 1 (F′-[KW4R4])

SK-OV-3 cells were grown in six-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) with complete EMEM 24 h prior to the cellular uptake assay. A 1 mM fluorescein-labeled peptide stock solution was prepared in water and diluted in Gibco Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium to yield a final concentration of 5 μM. The culture media were removed from six-well plates, and the 5 μM fluorescein-labeled peptide solution was added. After incubation for 1 h, a trypsin-EDTA solution was added to detach cells from the plate’s surface and remove cell surface binding peptides. After the sample had been treated for 5 min with trypsin-EDTA, a portion of complete medium was added to stop the activity of trypsin. The cell lines were collected and centrifuged at 2500 rpm. Then cells were washed twice using PBS without calcium and magnesium and prepared in FACS buffer for cell analysis. The cells were analyzed with a BD FACSVerse flow cytometer using the FITC channel. Data collection was based on the mean fluorescence signal for 10000 cells. All assays were conducted in triplicate. 5(6)-Carboxyfluorescein (FAM) was used as a negative control.

Mechanistic Study of Cellular Uptake by Removing Energy Sources

To examine the cellular uptake mechanism of F′-[KR4W4] at low temperatures, we conducted the uptake assay at 4 °C to inhibit the energy-dependent cellular uptake. SK-OV-3 cells were preincubated at 4 °C for 15 min and then incubated with the fluorescein-labeled peptide for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were collected and assessed with the same protocol described for the cellular uptake of the fluorescein-labeled peptide. The data collected at 37 °C were used for control. For the ATP depletion assay, cells were incubated with 10 mM sodium azide and 50 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose for 1 h before the fluorescein-labeled peptide was added. During the 1 h incubation, 5 μM F′-[KR4W4] was prepared in the Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium in the presence of 10 mM sodium azide and 50 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose. Then the cells were incubated with this solution for 1 h. The subsequent sample preparation and flow cytometry analysis protocol was similar to the protocol described above.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

SK-OV-3 cells were seeded with complete EMEM on coverslips in a six-well plate (1 × 105 cells/well) and kept at 50% confluency. The media were removed, and cells were incubated with 10 μM F′-[KR4W4] in Gibco Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 1 h at 37 °C. Then cells were washed three times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline with calcium and magnesium (PBS+). The coverslips were mounted on microscope slides, and images were obtained using a Carl Zeiss LSM 700 system with 488 nm argon ion laser excitation and a BP 505–530 nm band-pass filter.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

All 14 peptides, 1–14 (Table 1), were synthesized by Fmoc/tBu solid-phase peptide synthesis as described above. Peptides 1–6 were synthesized for this study, and peptides 7–14 had been previously reported.21 Peptides 1–4 were designed to have a positive charge and hydrophobic moieties. On the other hand, peptides 5 and 6 were designed to have a negative charge and hydrophobic moieties for comparative studies. Peptides 7–13 have cyclic polyarginines and hydrophobic fatty acids or tryptophan. Peptide 14 was synthesized as a linear counterpart of peptide 13. The chemical structures of synthesized peptides are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of synthetic peptides examined for antimicrobial activity.

As a representative example, the synthesis of [R4W4] is described here (Scheme 1). Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH was coupled on H-Trp(Boc)-2-chlorotrityl resin three times using HBTU, HOBT, and DIPEA in DMF. Piperidine in DMF [20% (v/v)] was used to remove the Fmoc group after each coupling. The subsequent coupling of Fmoc-Arg(pbf)-OH was conducted four times in a similar manner. The linear peptide with a protected side chain was cleaved from the resin using a TFE/acetic acid/DCM mixture [2:1:7 (v/v/v)] and cyclized in the presence of HOAT and DIC. Reagent “R”, a trifluoroacetic acid/thioanisole/1,2-ethanedithiol/anisole mixture [90:5:3:2 (v/v/v/v)], was added to remove side chain protecting groups to yield crude peptide 1. The peptide was purified by preparative RP-HPLC as described in the Experimental Section.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Peptide 1 ([R4W4]).

Antibacterial Activities

MIC values were measured for the 14 peptides against MRSA and P. aeruginosa (Table 2). These two bacterial strains are representative of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. MRSA is the most common Gram-positive pathogen that causes life-threatening infection, while P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative pathogen that can use multidrug efflux pumps and gene mutations to create multidrug resistance.25 Overall, these peptides were more potent against MRSA than P. aeruginosa. Peptide 1 was the most potent peptide against MRSA with a MIC value of 2.67 μg/mL (1.95 μM). Cyclic peptides 1, 3, 9, 10, and 13 showed improved antibacterial activities in comparison to those of linear peptides 2, 4, and 14. Acylated cyclic peptides 9, 10, and 13 exhibited activity that was more potent than that of nonacylated cyclic peptide 7. These data are consistent with the cell penetrating property of amphiphilic peptides described in our previous report.21 The correlation between antimicrobial activity and cell penetrating property is presumably due to the interaction between positively charged amphiphilic peptides and bacterial membranes that have negatively charged components. This explanation is consistent with a lack of activity observed for negatively charged peptides 5 and 6. Peptide 1 showed promising results as an antimicrobial peptide against MRSA. Thus, it was selected for further time-kill studies.

Table 2. Antibacterial Activities of Synthetic Peptides against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Strains.

| MIC (μg/mL) (μM)a |

||

|---|---|---|

| peptide | methicillin-resistant S. aureus | P. aeruginosa |

| 1 | 2.67 (1.95) | 42.8 (31.3) |

| 2 | 43.4 (31.3) | 21.7 (15.6) |

| 3 | 18.5 (15.6) | 37.0 (31.3) |

| 4 | 150 (125) | 150 (125) |

| 5 | >158 (>125) | >158 (>125) |

| 6 | >134 (>125) | >134 (>125) |

| 7 | >114 (>125) | >114 (>125) |

| 8 | 129 (125) | >129 (>125) |

| 9 | 8.53 (7.81) | 136 (125) |

| 10 | 8.97 (7.81) | >143 (>125) |

| 11 | 83.4 (62.5) | 167 (125) |

| 12 | 53.0 (31.3) | >212 (>125) |

| 13 | 9.75 (7.81) | 156 (125) |

| 14 | 69.3 (62.5) | >139 (>125) |

| controlb | 0.156 (0.352) | 0.731 (1.56) |

Values in parentheses are MICs in units of micromolar.

Tetracycline and tobramycin were used as controls for MRSA and P. aeruginosa, respectively.

Time-Kill Studies against MRSA and E. coli

As described above, we used both methicillin-resistant S. aureus and P. aeruginosa for the determination of MICs as representatives of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, respectively. Overall, these peptides were more potent against MRSA than against P. aeruginosa. Peptide 1 showed MIC values of 2.67 μg/mL (1.95 μM) and 42.8 μg/mL (31.3 μM) against MRSA and P. aeruginosa, respectively. Because of the high MIC value against P. aeruginosa, this pathogen was not selected for the time-kill study. Instead, E. coli, a Gram-negative pathogen, was selected on the basis of the fact that peptide 1 showed higher antibacterial activity toward E. coli than toward P. aeruginosa in the initial screening.

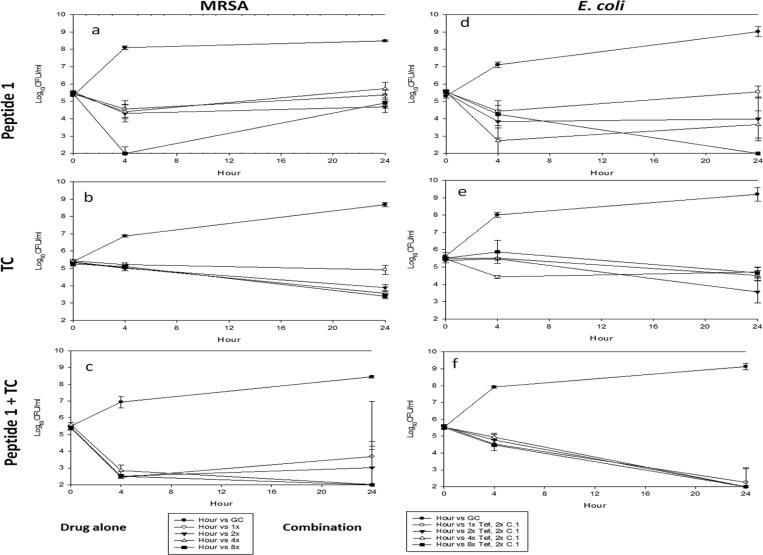

Time-kill studies were conducted to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of peptide 1 alone and in combination with tetracycline against MRSA and E. coli over 24 h (Figure 2). Peptide 1 and tetracycline alone did not demonstrate bactericidal (>3 log10 CFU/mL reduction) activity against MRSA (Figure 2a,b). When peptide 1 was used at 8 times the MIC against MRSA, it showed maximal antibacterial activity after 4 h. MRSA strains showed growth again after 24 h. These data showed that peptide 1 alone is not effective enough against MRSA even at 8 times the MIC. However, when the combination of peptide 1 and tetracycline was used, they showed bactericidal effects at 4 and 8 times the MIC with no growth even after 24 h. Combinations of 2 times the MIC of peptide 1 with 4 and 8 times the MIC of tetracycline demonstrated bactericidal activity against MRSA by 24 h (Figure 2c). Thus, combinations of peptide 1 and tetracycline did not meet the definition for synergy against MRSA. However, the combination of the two compounds turned the individual bacteriostatic activities of tetracycline and peptide 1 into bactericidal activity. In combination studies, the log10 CFU/mL was increased again after 24 h at the lowest tetracycline concentration. It means that MRSA strains can be killed under the condition of combination with a low concentration of peptide 1. Thus, at least 4 times the MIC of peptide 1 and 2 times the MIC of tetracycline are required to have effectiveness against MRSA strains. These data indicate that the combination of peptide 1 and tetracycline is critical for antibacterial activity against MRSA. Bactericidal antimicrobial agents are required to treat infections in immunocompromised patients.

Figure 2.

Time-kill curves of peptide 1, tetracycline (TC), and a combination for MRSA (ATCC 43300) and E. coli (ATCC 35218) at 37 °C for 24 h. Peptide 1 at two times the MIC was combined with tetracycline at 1, 2, 4, and 8 times the MIC (MICs of peptide 1, 4 μg/mL for MRSA and 16 μg/mL for E. coli; MIC for tetracycline (TC), 0.5 μg/mL for MRSA and 2 μg/mL for E. coli).

E. coli is one of predominant pathogens causing various common bacterial infections and has acquired multidrug resistance because of long-term use of antibiotics to treat this pathogen. Peptide 1 alone was able to produce bactericidal activity alone against E. coli only at the highest concentration tested (8 times the MIC) (Figure 2d). The combination of 8 times the MIC of tetracycline and 2 times the MIC of peptide 1 demonstrated synergy at 24 h (Figure 2f). More studies are required to determine the mechanism of synergism. One assumption is that amphiphilic peptide 1 acts as a CPP and can deliver tetracycline to achieve higher intracellular concentrations.

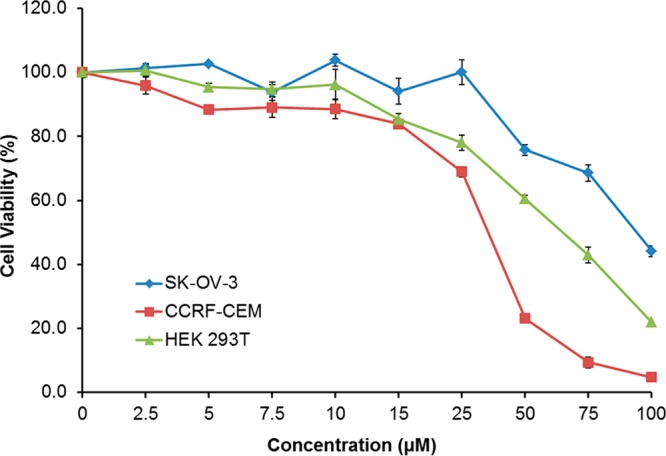

Cytotoxicity Assay of Peptide 1

The cytotoxicity of peptide 1 was evaluated by the MTS proliferation assay against human ovarian adenocarcinoma SK-OV-3, human leukemia CCRF-CEM, and human embryonic kidney HEK 293T cell lines. In both cancer and normal cell lines, the compound showed more than 84% cell viability at a concentration of 15 μM (20.5 μg/mL) (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3, CCRF-CEM cells were found to be more sensitive to the treatment than HEK 293T and SK-OV-3 cells. CCRF-CEM cells showed ∼25% cell viability when treated with peptide 1 (50 μM). However, HEK 293T and SK-OV-3 cells exhibited ∼60 and ∼78% viability, respectively, at a similar concentration. Thus, further cell-based investigations, such as flow cytometry and microscopy, were conducted at a nontoxic concentration of peptide 1 (15 μM) that showed ≤5% toxicity in SK-OV-3 cells. Moreover, peptide 1 alone showed a MIC against MRSA of 2.67 μg/mL, thus demonstrating selectivity for inhibiting the growth of S. aureus.

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity assay of peptide 1 against three cell lines (human ovarian adenocarcinoma SK-OV-3, human leukemia CCRF-CEM, and human embryonic kidney HEK 293T) by the MTS PMS assay (incubation for 24 h).

Cell Penetrating Property of Peptide 1 ([R4W4])

Peptide 1 was originally designed as a CPP to have a cell penetrating property. Thus, we synthesized fluorescein-labeled peptide 1 (F′-[KR4W4]) for cellular uptake assays, where F′ is fluorescein. The fluorescein-labeled peptide, F′-[KR4W4] (10 μM), was added to SK-OV-3 cells and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images showed that the fluorescein-labeled peptide was dispersed into the nucleus and cytosol (Figure 4A), but no significant fluorescence was observed in the cells treated with fluorescein alone under a similar condition (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Confocal laser scanning microscope image of (A) F′-[KR4W4] (10 μM) and (B) FAM in SK-OV-3 cells (incubation for 1 h).

The mechanism of cellular uptake was investigated by a temperature control assay at 4 °C and ATP depletion assay according to the previously reported procedures.26,27 The cellular uptake of peptide 1 was decreased ∼59% at 4 °C, indicating that the cellular uptake occurred by both endocytotic and nonendocytotic pathways (Figure 5). An ATP depletion assay also supports this mixed pathway uptake because there was 80% intracellular transportation even though all energy sources were blocked by sodium azide and 2-deoxy-d-glucose. These results were consistent with the previous studies that indicated that intracellular transportation can be controlled by several mixed pathways.28

Figure 5.

Energy-dependent mechanistic study of intracellular uptake of F′-[KW4R4]. Cellular uptake was investigated at 4 °C under ATP depletion conditions.

Conclusion

Amphiphilic cyclic CPPs (peptides 1, 9, 10, and 13) exhibited potent antibacterial activities against MRSA in the range of 2.67–9.75 μg/mL. Cyclic peptides showed antibacterial activities better than those of the corresponding linear counterparts. Fatty acylated cyclic peptides exhibited more potency versus their nonacylated cyclic counterparts. The antibacterial activity correlates well with the cell penetrating property of the same peptides. The rate of cellular uptake of fluorescence-labeled [KR4W4] was significantly higher than that of FAM alone. Amphiphilic cyclic peptide [R4W4] (1) provided improved antibacterial activities when it was co-administered with antibiotics such as tetracycline. These data suggest that improved uptake of tetracycline in combination with peptide 1 may account for the improved antibacterial activity. Interactions of the peptide with membranes of eukaryotic cells may be different from those in bacteria. Thus, further investigations are required to determine the exact nature of the interactions between peptide 1 and tetracycline and the resulting mechanism of higher antibacterial activity. In support of this hypothesis, time-kill studies demonstrated that only combinations of both peptide 1 and tetracycline exhibited bactericidal activities against MRSA and E. coli. This study suggests that amphiphilic cyclic CPPs may provide alternative therapeutic strategies in the effort to defeat life-threatening infectious diseases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of using an antimicrobial cyclic CPP in combination with an antibiotic for generating bactericidal activities.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, Grant 8 P20 GM103430-12 for sponsoring the core facility. This material is also based upon work conducted at a research facility at the University of Rhode Island supported in part by National Science Foundation EPSCoR Cooperative Agreement EPS-1004057. We thank Kayla Babcock for the technical assistance.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Moellering R. C. MRSA: The first half century. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David M. Z.; Daum R. S. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 616–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E. Y.; Sun L.; Smith D. L.; Laxminarayan R. The changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: A national observational study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens R. M.; Morrison M. A.; Nadle J.; Petit S.; Gershman K.; Ray S.; Harrison L. H.; Lynfield R.; Dumyati G.; Townes J. M.; et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 298, 1763–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S.; Sievert D. M.; Hageman J. C.; Boulton M. L.; Tenover F. C.; Downes F. P.; Shah S.; Rudrik J. T.; Pupp G. R.; Brown W. J.; et al. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen J. N.; Alder J.; Thorne G. M.; Tally F. P. Daptomycin: A lipopeptide antibiotic for the treatment of serious Gram-positive infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 55, 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M. K.; Rezai K.; Hayes R. A.; Lolans K.; Quinn J. P.; Weinstein R. A. Development of daptomycin resistance in vivo in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5285–5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister P. D.; Wolter D. J.; Hanson N. D. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 582–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse D. A.; Zhao S.; Tong E.; Ayers S.; Singh A.; Bartholomew M. J.; McDermott P. F. Antimicrobial drug resistance in Escherichia coli from humans and food animals, United States, 1950–2002. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K.; Scholes D.; Stamm W. E. Increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens causing acute uncomplicated cystitis in women. JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999, 281, 736–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell C. D.; Hiss J. A.; Hancock R. E. W.; Schneider G. Designing antimicrobial peptides: Form follows function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohner K. New strategies for novel antibiotics: Peptides targeting bacterial cell membranes. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2009, 28, 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer R. I.; Ganz T. Antimicrobial peptides in mammalian and insect host defence. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1999, 11, 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi A. C. Antimicrobial peptides from amphibian skin: An expanding scenario: Commentary. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002, 6, 799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. L. Antimicrobial peptides stage a comeback. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder E. L.; Dowdy S. F. Cell penetrating peptides in drug delivery. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivès E.; Schmidt J.; Pèlegrin A. Cell-penetrating and cell-targeting peptides in drug delivery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1786, 126–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal D.; Nasrolahi Shirazi A.; Parang K. Cell-penetrating homochiral cyclic peptides as nuclear-targeting molecular transporters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9633–9637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. T.; Chau J. K.; Perry N. A.; de Boer L.; Zaat S. A. J.; Vogel H. J. Serum stabilities of short tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptide analogs. PLoS One 2010, 5, e12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lättig-Tünnemann G.; Prinz M.; Hoffmann D.; Behlke J.; Palm-Apergi C.; Morano I.; Herce H. D.; Cardoso M. C. Backbone rigidity and static presentation of guanidinium groups increases cellular uptake of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh D.; Nasrolahi Shirazi A.; Northup K.; Sullivan B.; Tiwari R. K.; Bisoffi M.; Parang K. Enhanced cellular uptake of short polyarginine peptides through fatty acylation and cyclization. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2014, 11, 2845–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R. M.; Vogel H. J. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1462, 11–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved Standard M7-A7; National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards: Wayne, PA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante K. L.; Rybak M. J. Clinical glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococci tested against arbekacin, daptomycin, and tigecycline. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004, 50, 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aeschlimann J. R. The role of multidrug efflux pumps in the antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria. Insights from the society of infectious diseases pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrolahi Shirazi A.; Tiwari R. K.; Oh D.; Sullivan B.; McCaffrey K.; Mandal D.; Parang K. Surface decorated gold nanoparticles by linear and cyclic peptides as molecular transporters. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 3137–3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrolahi Shirazi A.; Mandal D.; Tiwari R.; Guo L.; Lu W.; Parang K. Cyclic peptide-capped gold nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 10, 500–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani F.; Lindberg S.; Langel U.; Futaki S.; Gräslund A. Mechanisms of cellular uptake of cell-penetrating peptides. J. Biophys. 2011, 2011, 414729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]