Abstract

Secondary insults, such as hemorrhagic shock (HS), worsen outcome from traumatic brain injury (TBI). Both TBI and HS modulate levels of inflammatory mediators. We evaluated the addition of HS on the inflammatory response to TBI. Adult male C57BL6J mice were randomized into five groups (n=4 [naïve] or 8/group): naïve; sham; TBI (through mild-to-moderate controlled cortical impact [CCI] at 5 m/sec, 1-mm depth), HS; and CCI+HS. All non-naïve mice underwent identical monitoring and anesthesia. HS and CCI+HS underwent a 35-min period of pressure-controlled hemorrhage (target mean arterial pressure, 25–27 mm Hg) and a 90-min resuscitation with lactated Ringer's injection and autologous blood transfusion. Mice were sacrificed at 2 or 24 h after injury. Levels of 13 cytokines, six chemokines, and three growth factors were measured in serum and in five brain tissue regions. Serum levels of several proinflammatory mediators (eotaxin, interferon-inducible protein 10 [IP-10], keratinocyte chemoattractant [KC], monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1], macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha [MIP-1α], interleukin [IL]-5, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF]) were increased after CCI alone. Serum levels of fewer proinflammatory mediators (IL-5, IL-6, regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted, and G-CSF) were increased after CCI+HS. Serum level of anti-inflammatory IL-10 was significantly increased after CCI+HS versus CCI alone. Brain tissue levels of eotaxin, IP-10, KC, MCP-1, MIP-1α, IL-6, and G-CSF were increased after both CCI and CCI+HS. There were no significant differences between levels after CCI alone and CCI+HS in any mediator. Addition of HS to experimental TBI led to a shift toward an anti-inflammatory serum profile—specifically, a marked increase in IL-10 levels. The brain cytokine and chemokine profile after TBI was minimally affected by the addition of HS.

Key words: : blast injury, chemokine, head injury, hypotension, interleukin, polytrauma, resuscitation

Introduction

Death and unfavorable neurologic outcome after traumatic brain injury (TBI) are strongly associated with secondary insults, such as hypotension.1 This secondary insult has taken on great importance related to blast TBI of U.S. soldiers injured in attacks by improvised explosive devices in both Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.2 In blast injury, TBI is often accompanied by polytrauma. Hemorrhagic hypotension thus results from extremity injuries and/or shrapnel, and high mortality rates have been reported in this setting.3 Hypotension after TBI is also common in civilian cohorts, affecting 26% of TBI patients in one study.4

To better understand the mechanisms underlying the exacerbation of damage by hypotension after TBI, we have developed mouse models of combined TBI plus hemorrhagic shock (HS). In these models, TBI is produced by a mild-to-moderate controlled cortical impact (CCI), followed by either volume-5–7 or pressure-controlled8 HS. In our model of pressure-controlled HS, we recently showed that the addition of HS exacerbates contusion volume, hemispheric brain tissue loss, hippocampal neuronal death, and functional deficit.8 However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms contributing to this unfavorable outcome have only begun to be examined, and the effect of HS on the brain and systemic inflammatory response to TBI remain to be defined.

Experimental and clinical studies of TBI have demonstrated robust increases in inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, in serum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), brain interstitial fluid, and brain tissue.9–34 The overall effect of inflammation on the brain after TBI, however, is complex, and earlier studies indicate that inflammation after TBI is a “dual-edged sword.” For example, blockade of proinflammatory interleukin (IL)-1β is associated with improvements in functional outcome and brain tissue loss after CCI,35 whereas knockout (KO) of proinflammatory inducible nitric oxide synthase is associated with worsened functional outcome and hippocampal neuronal loss after CCI.36 Similarly, conflicting roles for the associations of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines with favorable and unfavorable outcomes have been reported in clinical studies.10,22,34,37 To our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined the effect of HS on inflammatory response to TBI in either the experimental or clinical setting.

In the current report, Multiplex technology was used to measure brain tissue and serum levels of a large number of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, in mice after sham injury, HS, CCI, and a combined CCI plus HS insult. We hypothesized that the addition of HS to CCI would modulate cerebral and systemic inflammatory responses observed after TBI alone toward a more proinflammatory state.

Methods

Experimental protocol and study groups

The institutional animal care and use committee of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (Pittsburgh, PA) approved all experiments. The details of our CCI+HS model have been previously described.8 In the current study, male C57BL6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), 12–15 weeks of age, were used. Anesthesia was induced with 4% isoflurane in oxygen and maintained with 1% isoflurane in 2:1 N2O/O2 by nose cone. Inguinal cut down and insertion of femoral venous and arterial catheters were accomplished under sterile conditions using modified polyethylene 50 tubing. After placement of the mouse in a stereotaxic frame, a 5-mm craniotomy was performed over the left parietotemporal cortex with a dental drill, and the bone flap was removed. Immediately after craniotomy, the inhalational anesthesia was changed to 1% isoflurane and room air for a 10-min equilibration period before beginning the injury protocols. Monitoring included a brain parenchyma temperature probe inserted through a separate burr hole. While brain temperature was maintained at 37±0.5°C, CCI was performed with a pneumatic impactor. A 3-mm flat-tip impounder was deployed at a velocity of 5 m/sec and a depth of 1 mm. This injury level for CCI was specifically chosen to produce a contusion without significant hippocampal neuronal death, unless HS is superimposed upon the insult.5,8,38,39

HS was induced by phlebotomy to a target mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) of 25–27 mm Hg (HS phase). Mice remained hypotensive for a total of 35 min. After completion of the HS phase, a 90-min prehospital phase was initiated and 20 mL/kg of lactated Ringer's (LR) was rapidly infused. Additional aliquots of 10 mL/kg were infused as needed to achieve a MAP of 70 mm Hg. To simulate arrival at definitive care (hospital phase), the inhaled gas mixture was switched from 1% isoflurane in room air to 1% isoflurane in oxygen, and all shed blood was reinfused. At completion of the hospital phase, catheters were removed, anesthesia discontinued, and mice recovered in supplemental oxygen for 30 min before being returned to their cages.

Mice were randomized to one of five study groups (n=4 [naïve] or 8 per group) and underwent procedures or equivalent anesthesia and monitoring as designated: 1) naïve (no anesthesia, craniotomy, monitoring, CCI, or HS); 2) sham (anesthesia, monitoring, and craniotomy, without CCI or HS); 3) CCI alone; 4) HS alone (including monitoring, without craniotomy); or (5) CCI+HS. Mice in the CCI-only group underwent CCI without HS, but were maintained under identical anesthesia and monitoring as the combined injury group for a 90-min interval. Heart rate (HR), MAP, arterial blood gas results (pH, PaCO2, PaO2, and base deficit), hematocrit, and lactate were recorded serially.

Multiplex assessment

Mice were euthanized at either 2 or 24 h after finishing the experimental protocol (n=4 per time point per study group). Mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane, and a blood sample was obtained by cardiac puncture. Animals were then transcardially perfused with heparinized saline. Brains were dissected into cerebellum, parietal cortex (ipsi- and contralateral), and hippocampus (ipsi- and contralateral) and snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen. Tissue was weighed and homogenized with an 8×volume of 1×phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sonicated, and spun for 30 min at 14,000g to obtain the supernatant. Protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Vernon Hills, IL). Supernatant aliquots were assayed for inflammatory mediators by Multiplex (n=3 for 24-h CCI group; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Individual protein levels were indexed to total measured level of protein in the sample (pg/mg of protein). Levels of 10 proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-12, IL-17, interferon-gamma [IFN-γ], and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]), three anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13), six chemokines (eotaxin [C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)11], IFN-inducible protein 10 [IP-10; C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)10], keratinocyte chemoattractant [KC; CXCL1; analog of human IL-8], monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1; CCL2], macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha [MIP-1α; CCL3], and regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted [RANTES; CCL5]), and three growth factors (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF], granulocyte macrophage/colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF], and vascular endothelial growth factor) were measured. Though chemokines are a type of cytokine (chemotactic cytokine), the term “cytokine” is used throughout the article to mean cytokines that are not chemokines (i.e., IL-4, IL-6, and so on).

Comparison of sensitivity of Multiplex and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

To determine how the sensitivity of Multiplex compared to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specifically in brain tissue samples, we carried out two additional experiments. First, we studied mice in the same three groups (naïve, CCI, and CCI+HS; n=3/group) and sacrificed them at 2 h after insult using an identical protocol to that used for Multiplex assessments. Brain samples from the same five regions were processed identically and again homogenized in PBS as described above and assayed for TNF-α by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Second, we again studied mice in the same threegroups (naïve, CCI, and CCI+HS; n=3/group) and sacrificed them at 2 h after insult using an identical protocol to that used for Multiplex and aforementioned ELISA, except that lysis buffer (radioimmunoprecipitation assay [RIPA] buffer; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used rather than PBS. Brain samples from the same five regions were again assayed for TNF-α by ELISA (R&D Systems). The assay detection limit was 0.36 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Brain levels of mediators are reported in pg/mg of protein (median [range]) and serum levels in pg/mL of serum (median [range]). Nonzero mediator levels outside of the lab's reference range were transformed into a standardized high or low value (2000 or 0.1 pg/mg of protein for brain tissue samples; 20,000 or 1.0 pg/mL for serum samples). Similar to earlier studies, mediators with levels frequently outside of the reference range (>65%) were excluded from analysis.40,41 Results of mediator levels were grouped by injury mechanism, tissue sample type, and time point. Given that the data were not normally distributed, Wilcoxon's rank-sum test with Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was used to make pair-wise group comparisons with sham as control for brain tissue levels and naïve as control for serum levels. Physiology parameters are reported as mean. Physiology parameters were compared with a one-way analysis of variance test and with Holm-Sidak's test. A value of p<0.05 was deemed significant. Only results with significant differences between groups are shown.

Results

Physiology data

Similar to earlier studies in this model,8 there were no significant differences in baseline physiologic parameters between groups (Table 1). After injury, HR was increased in all injury groups versus sham and was increased in the CCI+HS group versus CCI and HS-alone groups. The significant decrease in MAP in the HS and CCI+HS groups that was observed after the HS and prehospital phases was not present at the end of the hospital phase, after return of the shed blood. There were no significant changes in pH other than a mild acidosis (7.34±0.02) in CCI+HS versus both sham and CCI groups after the HS phase. However, compared to sham and CCI, the HS and CCI+HS groups had significant increases in base deficit and blood lactate after the HS phase, with significant respiratory compensation as reflected by hypocarbia. Blood lactate was also increased at the end of the prehospital phase in the CCI+HS group versus sham and CCI groups. Hematocrit was decreased in the HS and CCI+HS versus the sham and CCI groups after injury. PaO2 was increased in the HS and CCI+HS versus the sham and CCI groups at the end of the HS phase. One animal in the CCI+HS group died during the prehospital phase.

Table 1.

Physiology Parameters at Various Stages of Experiment

| Parameter | Sham | HS | CCI | CCI+HS | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | |||||

| Baseline | 522 (15.97) | 539 (8.73) | 541 (9.41) | 549 (12.27) | 0.451 |

| End of HSP | 492 (8.50) | 560* (22.09) | 529 (12.93) | 645*†† (12.25) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 487 (8.82) | 604* (11.47) | 581* (8.35) | 638*†† (7.07) | <0.001 |

| End of HP | 456 (10.43) | 508* (6.94) | 569*† (10.33) | 544*† (12.43) | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial blood pressure | |||||

| Baseline | 88 (1.25) | 90 (1.87) | 90 (1.00) | 89 (1.92) | 0.763 |

| End of HSP | 79 (1.64) | 26* (0.42) | 79† (1.12) | 25*† (0.47) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 79 (2.28) | 67* (1.96) | 79† (2.92) | 63*† (2.43) | <0.001 |

| End of HP | 79 (2.04) | 78 (1.66) | 79 (3.19) | 73 (1.40) | 0.181 |

| pH | |||||

| Baseline | 7.39 (0.02) | 7.39 (0.02) | 7.40 (0.02) | 7.39 (0.02) | 0.979 |

| End of HSP | 7.42 (0.01) | 7.38 (0.01) | 7.42 (0.01) | 7.34*† (0.02) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 7.40 (0.01) | 7.41 (0.01) | 7.40 (0.01) | 7.41 (0.01) | 0.803 |

| End of HP | 7.37 (0.01) | 7.34 (0.02) | 7.36 (0.01) | 7.32 (0.02) | 0.121 |

| PaCO2 | |||||

| Baseline | 27.9 (1.25) | 30.1 (0.81) | 29.1 (0.71) | 32.3 (1.91) | 0.103 |

| End of HSP | 30.1 (0.99) | 23.3* (1.09) | 29.0† (0.62) | 22.3*† (1.26) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 29.1 (1.08) | 28.8 (0.52) | 30.4 (1.20) | 28.8 (1.14) | 0.661 |

| End of HP | 33.4 (1.27) | 36.7 (2.06) | 33.0 (1.49) | 39.2 (1.93) | 0.048 |

| PaO2 | |||||

| Baseline | 163 (2.09) | 156 (5.62) | 159 (5.89) | 161 (6.80) | 0.828 |

| End of HSP | 88 (2.22) | 103* (2.13) | 89† (1.74) | 103*† (2.38) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 90 (1.84) | 87 (1.92) | 86 (2.38) | 83 (5.46) | 0.483 |

| End of HP | 431 (31.28) | 460 (6.32) | 444 (6.34) | 463 (3.23) | 0.534 |

| Base deficit | |||||

| Baseline | 5.4 (0.87) | 4.7 (0.86) | 4.8 (0.90) | 4.1 (0.35) | 0.695 |

| End of HSP | 3.5 (0.58) | 9.1* (0.36) | 3.9† (0.58) | 11.5*†† (0.81) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 4.9 (1.03) | 4.8 (0.37) | 3.9 (0.64) | 5.3 (0.32) | 0.476 |

| End of HP | 5.0 (0.62) | 4.9 (0.54) | 5.4 (0.46) | 5.3 (0.47) | 0.894 |

| Hematocrit | |||||

| Baseline | 41 (1.60) | 39 (0.76) | 41 (1.37) | 39 (0.72) | 0.439 |

| End of HSP | 38 (1.18) | 28* (0.56) | 37† (0.85) | 26*† (0.93) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 39 (1.03) | 21* (0.69) | 37† (1.10) | 19*† (0.82) | <0.001 |

| End of HP | 37 (1.28) | 31* (1.41) | 35 (1.20) | 28*† (0.58) | <0.001 |

| Lactate | |||||

| Baseline | 2.3 (0.22) | 2.3 (0.17) | 2.2 (0.13) | 2.3 (0.16) | 0.968 |

| End of HSP | 1.4 (0.08) | 5.7* (0.28) | 1.3† (0.12) | 7.7*†† (0.77) | <0.001 |

| End of PHP | 1.2 (0.12) | 2.0 (0.22) | 1.5 (0.08) | 2.5*† (0.47) | 0.006 |

| End of HP | 1.1 (0.10) | 1.2 (0.12) | 1.2 (0.08) | 1.5 (0.19) | 0.158 |

Values shown as mean (standard error of the mean). All groups compared with one-way analysis of variance (p value shown). Pair-wise comparisons done with Holm-Sidak's test, and significant differences are notated (*vs. sham; †vs. HS; ††vs. CCI; all p < 0.05).

HS, hemorrhagic shock; CCI, controlled cortical impact; HSP, hemorrhagic shock phase; PHP, prehospital phase; HP, hospital phase.

Brain tissue levels

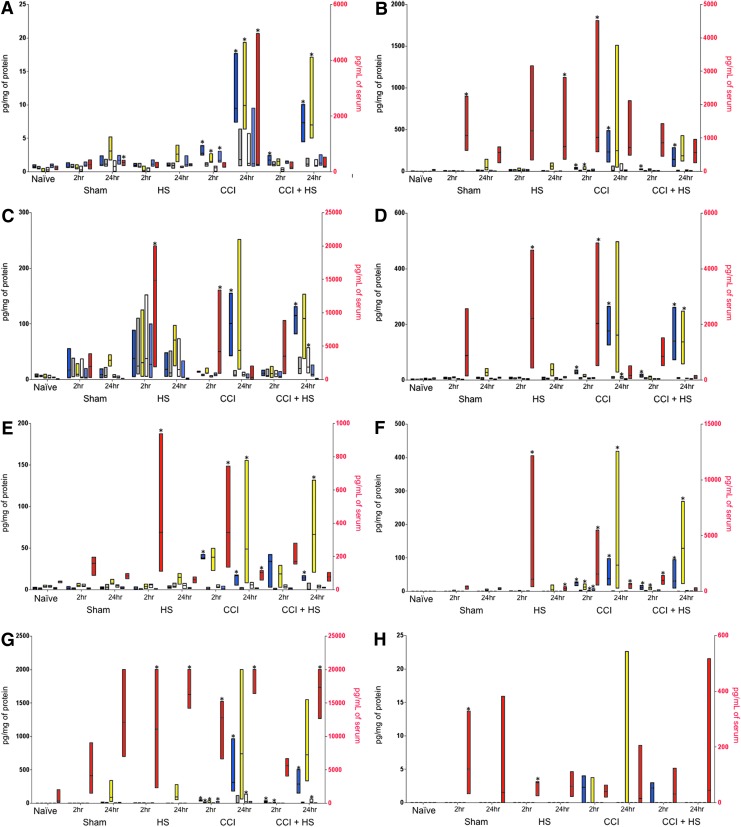

Of the 22 inflammatory mediators tested by Multiplex, seven were increased (p<0.05 vs. sham) in brain tissue both after CCI alone and after CCI+HS, including five chemokines (eotaxin, IP-10, KC, MCP-1, and MIP-1α), one cytokine (IL-6), and one growth factor (G-CSF; see Fig. 1A–G). The highest median levels of all seven mediators were observed at 24 h after both CCI alone and CCI+HS. Significant increases in eotaxin, IP-10, MCP-1, and MIP-1α observed at 24 h after CCI+HS in ipsilateral brain tissue were not observed at 2 h after CCI+HS in the same brain region. Similarly, unique increases in brain tissue IP-10 and MIP-1α were observed after CCI only at the later time point. There were no statistically significant differences between levels after CCI alone and after CCI+HS in any mediator, and no mediators were increased after only CCI or only CCI+HS. No mediators were increased after HS alone.

FIG. 1.

Measured values of inflammatory mediators. Bars represent minimum to maximum values, and the dividing line represents the median. Brain tissue regions are ipsilateral hippocampus (blue), contralateral hippocampus (gray), ipsilateral parietal cortex (yellow), contralateral parietal cortex (white), and cerebellum (light blue). Color coding is also shown in the insert. Brain tissue values are plotted on the left axis in pg/mg of protein. Serum values (red) are plotted on the right axis in pg/mL of serum. Stars represent a significant difference versus control (sham for brain tissue and naïve for serum; p<0.05 for both). Double bars represent a significant difference versus controlled cortical impact (CCI) alone. (A) Eotaxin; (B) keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC); (C) interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10); (D) monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1); (E) macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1α); (F) interleukin (IL)-6; (G) granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF); (H) IL-1α; (I) IL-5; (J) IL-10; (K) tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α); and (L) regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES). HS, hemorrhagic shock. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

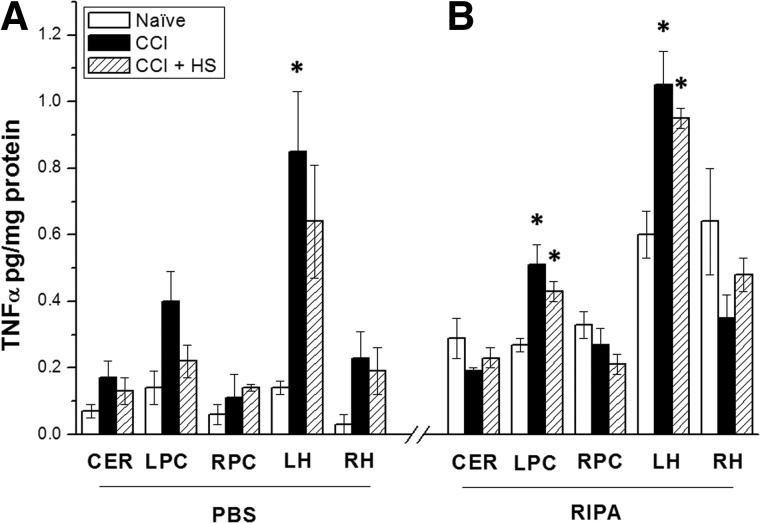

Figure 2A,B shows results of the two ELISA determinations of TNF-α carried out to compare the sensitivity of Multiplex to ELISA in brain tissue. In brain samples processed for ELISA with PBS, TNF-α levels were, in general, low (<0.5 pg/mg protein). Increases versus naïve were not observed in 13 of 15 brain regions that were assayed, consistent with Multiplex. However, TNF-α levels were significantly increased in the hippocampus ipsilateral to injury (p<0.05 vs. naïve; Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in cerebellum (CER), left and right parietal cortex (LPC and RPC, respectively), and left and right hippocampus (LH and RH, respectively) in naïve and non-naïve mice at 2 h after either controlled cortical impact (CCI) or CCI+HS (hemorrhagic shock). (A) Results from brain tissue samples homogenized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). (B) Results from samples homogenized with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. *p<0.05 versus respective naïve.

In samples processed with RIPA lysis buffer and assessed by ELISA, TNF-α levels were somewhat higher than in samples processed with PBS and assessed by either Multiplex or ELISA. Significant increases were observed versus naïve in both parietal cortex and hippocampus ipsilateral to injury in both CCI and CCI+HS, although the highest level observed was 1.05 pg/mg of protein.

Serum levels

Two hours after HS, serum levels of nine mediators were increased (p<0.05 vs. naïve), including three chemokines (IP-10, MCP-1, and MIP-1α), five cytokines (IL-1α, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α), and one growth factor (G-CSF; see Fig. 1C–K). At 24 h after HS, only four mediators were increased (KC, RANTES, IL-6, and G-CSF; p<0.05 vs. naïve; see Fig. 1L). Notably, the median level of IL-6 was higher at 2 h after HS than at 24 h. Similarly, median levels of KC and RANTES were higher at 2 than at 24 h, despite only being significantly increased at the later time point.

After CCI alone, four chemokines, four cytokines, and one growth factor were increased at 2 h (KC, MCP-1, MIP-1α, IP-10, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and G-CSF, respectively; p<0.05 vs. naïve) and two chemokines, one cytokine, and one growth factor were increased at 24 h (eotaxin, MIP-1α, IL-6, and G-CSF, respectively; p<0.05 vs. naïve). Notably, median levels of MIP-1α and IL-6 were highest at the earlier time point.

Few mediators were increased in serum after CCI+HS. IL-6, IL-5, and IL-10 (Fig. 1F,I,J) were increased at 2 h (p<0.05 vs. naïve), and IL-5, RANTES, and G-CSF were increased at 24 h (p<0.05 vs. naïve). Median levels of IL-6 were lower after CCI+HS than at the same time point after CCI. The level of anti-inflammatory IL-10 at 2 h after HS+CCI was statistically significantly increased versus CCI alone, the only instance of a mediator in any tissue type being significantly different in serum after the two injury mechanisms. Specifically, IL-10 levels were >200 pg/mL in CCI+HS, with contrasting levels of ∼2 pg/mL in CCI and ∼7 pg/mL in HS (Fig. 1J). Of note, to ensure that IL-10 production in the shed blood that was stored on the benchtop and reinfused after resuscitation was not contributing to the increase in serum levels after CCI+HS, we assessed IL-10 levels by ELISA (Cell Sciences, Inc., Canton, MA) in shed blood maintained at room temperature on the benchtop. In 5 mice, IL-10 levels in serum were assessed from blood samples obtained either immediately or after 90 min of storage. Levels were 7.83±0.85 and 10.25±0.61 pg/mL, respectively. Thus, reinfusion of shed blood cannot explain the marked increase in serum IL-10 level at 2 h after CCI+HS.

Discussion

There are three key findings from this study. First, the addition of HS to CCI led to a reduction in proinflammatory response and uniquely increased IL-10 in serum. Second, the inflammatory mediator response in the brain after CCI in our mouse model exhibited a robust chemokine response. Third, surprisingly, HS did not lead to an exacerbation of the inflammatory mediator response to CCI in the mouse brain.

Hemorrhagic shock shifts serum cytokine response to an anti-inflammatory profile after traumatic brain injury

The serum inflammatory profile after CCI+HS was more anti-inflammatory than after CCI. IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, was significantly increased 2 h after CCI+HS versus CCI alone. Six proinflammatory mediators (IP-10, TNF-α, KC, MCP-1, eotaxin, and MIP-1α) were all increased after CCI, but not CCI+HS, and IL-6 median levels were lower after combined injury.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the effect of HS on inflammatory response to experimental TBI, though earlier studies have analyzed the effect of systemic trauma. Similar to our results, in a model of TBI with and without tibia fracture,42 serum levels of IL-10 were highest in combined injury; however, higher levels of IL-6 were also observed in that combined injury. Data from two clinical studies also support our findings. Shiozaki and colleagues29 measured levels of proinflammatory (IL-1β and TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist, and soluble TNF receptor I) mediators in CSF and serum in adults with either TBI or TBI plus systemic trauma. Mirroring our findings, systemic trauma did not affect brain inflammatory response, but increased serum levels of anti-inflammatory mediators. Hensler and colleagues19 found increased serum levels of IL-10 and proinflammatory mediators in TBI patients with systemic injury. These similarities between murine and human inflammatory responses in serum to TBI+HS are very important in light of recent evidence that inflammatory responses to various stimuli differ between humans and mice.43 The findings in our report and these clinical studies are thus similar despite our model superimposing HS on TBI, not systemic trauma. Clinical work has shown that traumatic HS is associated with increased levels of IL-6 and IL-10 versus controls, whereas nontraumatic HS is only associated with increased levels of IL-10.44 Thus, systemic tissue injury may mediate proinflammatory mediator response, whereas HS mediates anti-inflammatory response. Further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanism by which IL-10 is increased in HS, though Kupffer cell damage45 and catecholamine release46 likely play a role.

The shift to a systemic anti-inflammatory cytokine profile after traumatic brain injury

Though our CCI+HS model has an unfavorable outcome versus CCI alone,8 the effect of the anti-inflammatory phenotype observed in combined injury requires further study. Anti-inflammatory mediators may worsen outcome through induction of an immunoparalyzed state, which has been suggested to contribute to the high prevalence of nosocomial infections in TBI patients.47 However, several studies in experimental TBI suggest that an anti-inflammatory shift could be neuroprotective. Systemic infusion of IL-10 reduced neutrophil influx into the brain after CCI in rats48 and improved functional outcome after fluid percussion injury.49 Attenuation of inflammation in the brain by IL-10, with resultant neuroprotection, has been suggested.50 Thus, the anti-inflammatory profile in CCI+HS could attenuate injury induced by HS. However, we have not studied the effect of IL-10 infusion on brain or serum cytokine levels or used the IL-10 KO in our combined injury paradigm.

Marked chemokine response in brain after controlled cortical impact

Previous studies of clinical TBI that measured multiple inflammatory mediators in CSF,12 brain tissue,15 and brain microdialysate18 all detected increased levels of several cytokines, but fewer chemokines, contrasting with our finding of a chemokine predominance. However, our findings are similar to the report of Bye and colleagues, who also used Multiplex to assess brain tissue cytokines and chemokines at 4 h after diffuse TBI produced with the Marmarou model in rats. 51 In that study, four cytokines were increased as were four chemokines, with a similar chemokine pattern as that observed in our report in CCI alone. Our results also mirror the work of Semple and colleagues, using a similar Multiplex approach in a closed TBI model in mice.52 In contrast, cytokine predominance was observed using Multiplex in a stab wound model of TBI in mice.31 These distinct patterns may be the result of differences between penetrating and blunt TBI, including injury severity and sampling location. Though these differences are intriguing, the vast majority of clinical TBI is secondary to closed-head injury.53 Also, other important factors could produce differences between clinical studies and our model, such as 1) assessment of RNA versus protein, 2) use of microdialysis or CSF versus brain tissue, 3) timing of the evaluation, and 4) brain regions studied.

Nevertheless, the importance of chemokine response in TBI has been gaining appreciation. Glabinski and colleagues16 reported acute increases in MCP-1 after TBI in mice. In a clinical study, Kossmann and colleagues54 reported that the chemokine, IL-8, was markedly increased in CSF after severe TBI (sTBI), which has been corroborated.33 A murine analog of IL-8, KC, was increased in the brain in our model. Studies in experimental TBI show selective chemokine messenger RNA expression55–57 as well as the presence of MIP-2,25,57 IP-10,21 KC,32 and MIP-1α25 in the brain. IP-10 is increased in human cerebral contusions after TBI.30 Buttram and colleagues12 found increased CSF levels of MIP-1α and IL-8 after sTBI in children. Roles have been described for IP-10 in microglial recruitment,58 MCP-1, and MIP-1α in Wallerian degeneration,59 MCP-1 in macrophage recruitment,60 IP-10 in T-cell recruitment,21 KC in neutrophil recruitment,61 and C-X3-C chemokine ligand 1 in leukocyte recruitment.62 Assessment of these possible effects, and of the effect of HS on the blood–brain barrier after TBI, is warranted in the setting of TBI+HS.

Several recent studies in experimental central nervous system injury suggest that chemokines may contribute to secondary injury after TBI. Semple and colleagues60 reported reduced tissue damage and hippocampal neuronal death in C-X-C chemokine receptor type 2–deficient mice. Similarly, Donnelly and colleagues63 reported that mice deficient in CX3C chemokine receptor 1 signaling were protected from functional impairment after spinal cord injury. However, chemokines can stimulate nerve growth factor production, which may be beneficial.54 Our data suggest the need for further investigation of chemokines in TBI in the setting of second insults, such as HS.

Hemorrhagic shock did not exacerbate the inflammatory mediator response to controlled cortical impact in the mouse model

Secondary insults exacerbate tissue damage and worsen outcome after experimental and clinical TBI.64 However, no study has examined the effect of HS on the inflammatory response to TBI and few have examined the effect of other secondary insults on the inflammatory responses to TBI. Goodman and colleagues reported in mice that hypobaric hypoxia (simulating air transport) early after TBI is associated with increased brain tissue levels of IL-6 and MIP-1α, but not with alterations in serum inflammatory response.65

HS increases serum levels of both pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators,44 which was replicated in our report in HS alone, but not in CCI+HS. Resuscitation may affect the inflammatory response. Fluids such as LR and normal saline can trigger neutrophil activation66 and increase cytokines.67 Blood transfusion is also associated with increased levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators.68 Resuscitation may also dilute levels of inflammatory mediators. Strongly arguing against a significant dilutional effect in our study, IL-10 was increased in serum in CCI+HS versus CCI alone. The addition of HS exacerbates histological damage and functional deficits in our model,8 so the lack of a change in the cytokine or chemokine response to TBI in the brain was surprising. Future studies of delayed time points are needed to assess mediators as the damage evolves.

Limitations

Although our findings are novel, our study has several limitations. We focused only on the acute inflammatory response to TBI. Our analysis was not designed to study the role of individual mediators, including noninflammatory properties.69 We used sham injury as the control for brain tissue effects and naïve for serum effects. Altered brain tissue levels of cytokines can be observed in sham controls,70 so sham-injured mice were the appropriate control for brain tissue levels. However, naïve mice are the best control for serum levels, given the need to compare HS alone to CCI+HS. Craniotomy did, for some mediators, alter serum cytokine response, and those cases can be readily appreciated in Figure 1. Differences in units for brain tissue (pg/mg of protein) and serum (pg/mL of serum) mediator levels limited our ability to compare the magnitudes of the intracerebral and systemic inflammatory responses. It should also be recognized that Multiplex may be somewhat less sensitive than ELISA for detection of certain cytokines and/or chemokines, particularly in brain tissue. We previously reported strong correlations between Multiplex and ELISA for both IL-6 and IL-8 in CSF.12 However, in the current study, for assessment of brain tissue, Multiplex appears to be less sensitive than ELISA for determining brain tissue TNF-α and this is, in part, related to the use of PBS as the homogenization buffer. ELISA using RIPA lysis buffer yielded the highest levels and significant increases in injured hippocampus and cortex at 2 h after injury, similar to the report of Khuman and colleagues, in closed-head injury in mice using an identical extraction and ELISA.71 Similar findings were observed by Yan and colleagues using a Multiplex that assessed six cytokines in a rat closed-head injury model.72 In contrast, as in our report, using a Multiplex that assessed 18 cytokines and chemokines, increases in TNF-α after TBI in rats were generally not observed and levels were more variable.51,52,73,74 Results can vary depending on the approach to tissue processing and the specific Multiplex. Lack of protease inhibitors could also contribute to lower levels when PBS is used as the homogenization buffer, because there could also be degradation of TNF or other proteins. However, given that RIPA buffer contains protease inhibitors, that mechanism should not be a problem when it is used as a lysis buffer. Finally, the possibility of false discovery is inherent to analysis of such a robust number of mediators; however, we used a rigorous correction for multiple comparisons.

We conclude that the addition of HS causes a shift toward an ant-inflammatory profile, characterized by an increase in IL-10 in serum after TBI in mice. Experimental TBI leads to a cytokine and chemokine response in brain tissue that is minimally affected by adding HS. Because HS detrimentally affects TBI outcome, it will be important to determine whether this increase in IL-10 levels has beneficial or detrimental effects on secondary brain injury and/or systemic immunity. Given that similar findings have been noted in clinical studies, further study is needed to determine whether there are therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgments

Support: DARPA N66001-10-C2124 (PMK), the United States Army W81XWH-09-2-0187 (PMK), and T32 HD040686 (SLS, JLE).

The authors thank DARPA (N66001-10-C2124; to P.M.K.) and the U.S. Army (W81XWH-09-2-0187; to P.M.K.), and the NICHD (T32 HD040686; to S.L.S.) for support. The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this article/presentation are those of the authors/presenters and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies, either expressed or implied, of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency or the Department of Defense. This article has been approved for public release (distribution unlimited).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Chesnut R.M., Marshall L.F., Klauber M.R., Blunt B.A., Baldwin N., Eisenberg H.M., Jane J.A., Marmarou A. and Foulkes M.A. (1993). The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J. Trauma 34, 216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fabrizio K.S., and Keltner N.L. (2010). Traumatic brain injury in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom: a primer. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 45, 569–580, vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson T.J., Wall D.B., Stedje-Larsen E.T., Clark R.T., Chambers L.W., and Bohman H.R. (2006). Predictors of mortality in close proximity blast injuries during Operation Iraqi Freedom. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 202, 418–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manley G., Knudson M.M., Morabito D., Damron S., Erickson V., and Pitts L. (2001). Hypotension, hypoxia, and head injury: frequency, duration, and consequences. Arch. Surg. 136, 1118–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis A.M., Haselkorn M.L., Vagni V.A., Garman R.H., Janesko-Feldman K., Bayır H., Clark R.S., Jenkins L.W., Dixon C.E., and Kochanek P.M. (2009). Hemorrhagic shock after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice: effect on neuronal death. J. Neurotrauma 26, 889–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Exo J.L., Shellington D.K., Bayır H., Vagni V.A., Janesko-Feldman K., Ma L., Hsia C.J., Clark R.S., Jenkins L.W., Dixon C.E., and Kochanek P.M. (2009). Resuscitation of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock with polynitroxylated albumin, hextend, hypertonic saline, and lactated Ringer's: Effects on acute hemodynamics, survival, and neuronal death in mice. J. Neurotrauma 26, 2403–2408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shellington D.K., Du L., Wu X., Exo J., Vagni V., Ma L., Janesko-Feldman K., Clark R.S., Bayır H., Dixon C.E., Jenkins L.W., Hsia C.J., and Kochanek P.M. (2011). Polynitroxylated pegylated hemoglobin: a novel neuroprotective hemoglobin for acute volume-limited fluid resuscitation after combined traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic hypotension in mice. Crit. Care Med. 39, 494–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemerka J.N., Wu X., Dixon C.E., Garman R.H., Exo J.L., Shellington D.K., Blasiole B., Vagni V.A., Janesko-Feldman K., Xu M., Wisniewski S.R., Bayır H., Jenkins L.W., Clark R.S., Tisherman S.A., and Kochanek P.M. (2012). Severe brief pressure-controlled hemorrhagic shock after traumatic brain injury exacerbates functional deficits and long-term neuropathological damage in mice. J. Neurotrauma 29, 2192–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beeton C.A., Chatfield D., Brooks R.A., and Rushton N. (2004). Circulating levels of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor in patients with head injury and fracture. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 86, 912–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell M.J., Kochanek P.M., Doughty L.A., Carcillo J.A., Adelson P.D., Clark R.S., Wisniewski S.R., Whalen M.J., and DeKosky S.T. (1997). Interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 in cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury in children. J. Neurotrauma 14, 451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger R.P., Ta'asan S., Rand A., Lokshin A. and Kochanek P. (2009). Multiplex assessment of serum biomarker concentrations in well-appearing children with inflicted traumatic brain injury. Pediatr. Res. 65, 97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buttram S.D., Wisniewski S.R., Jackson E.K., Adelson P.D., Feldman K., Bayır H., Berger R.P., Clark R.S., and Kochanek P.M. (2007). Multiplex assessment of cytokine and chemokine levels in cerebrospinal fluid following severe pediatric traumatic brain injury: effects of moderate hypothermia. J. Neurotrauma 24, 1707–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiaretti A., Genovese O., Aloe L., Antonelli A., Piastra M., Polidori G., and Di Rocco C. (2005). Interleukin 1beta and interleukin 6 relationship with paediatric head trauma severity and outcome. Childs Nerv. Syst. 21, 185–193; discussion, 194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Csuka E., Morganti-Kossmann M.C., Lenzlinger P.M., Joller H., Trentz O., and Kossmann T. (1999). IL-10 levels in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: relationship to IL-6, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1 and blood-brain barrier function. J. Neuroimmunol. 101, 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frugier T., Morganti-Kossmann M.C., O'Reilly D. and McLean C.A. (2010). In situ detection of inflammatory mediators in post mortem human brain tissue after traumatic injury. J. Neurotrauma 27, 497–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glabinski A.R., Balasingam V., Tani M., Kunkel S.L., Strieter R.M., Yong V.W., and Ransohoff R.M. (1996). Chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is expressed by astrocytes after mechanical injury to the brain. J. Immunol. 156, 4363–4368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayakata T., Shiozaki T., Tasaki O., Ikegawa H., Inoue Y., Toshiyuki F., Hosotubo H., Kieko F., Yamashita T., Tanaka H., Shimazu T., and Sugimoto H. (2004). Changes in CSF S100B and cytokine concentrations in early-phase severe traumatic brain injury. Shock 22, 102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helmy A., Carpenter K.L., Menon D.K., Pickard J.D., and Hutchinson P.J. (2011). The cytokine response to human traumatic brain injury: temporal profiles and evidence for cerebral parenchymal production. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 658–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hensler T., Sauerland S., Bouillon B., Raum M., Rixen D., Helling H.J., Andermahr J., and Neugebauer E.A. (2002). Association between injury pattern of patients with multiple injuries and circulating levels of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors, interleukin-6 and interleukin-10, and polymorphonuclear neutrophil elastase. J. Trauma 52, 962–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmin S., and Hojeberg B. (2004). In situ detection of intracerebral cytokine expression after human brain contusion. Neurosci. Lett. 369, 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israelsson C., Bengtsson H., Kylberg A., Kullander K., Lewen A., Hillered L., and Ebendal T. (2008). Distinct cellular patterns of upregulated chemokine expression supporting a prominent inflammatory role in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 25, 959–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoblach S.M., Fan L., and Faden A.I. (1999). Early neuronal expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha after experimental brain injury contributes to neurological impairment. J. Neuroimmunol. 95, 115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kossmann T., Hans V., Imhof H.G., Trentz O., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (1996). Interleukin-6 released in human cerebrospinal fluid following traumatic brain injury may trigger nerve growth factor production in astrocytes. Brain Res. 713, 143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kossmann T., Hans V.H., Imhof H.G., Stocker R., Grob P., Trentz O., and Morganti-Kossmann C. (1995). Intrathecal and serum interleukin-6 and the acute-phase response in patients with severe traumatic brain injuries. Shock 4, 311–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otto V.I., Stahel P.F., Rancan M., Kariya K., Shohami E., Yatsiv I., Eugster H.P., Kossmann T., Trentz O., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2001). Regulation of chemokines and chemokine receptors after experimental closed head injury. Neuroreport 12, 2059–2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partrick D.A., Moore F.A., Moore E.E., Biffl W.L., Sauaia A., and Barnett C.C., Jr. (1996). Jack A. Barney Resident Research Award winner. The inflammatory profile of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in postinjury multiple organ failure. Am. J. Surg. 172, 425–429; discussion, 429–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rancan M., Otto V.I., Hans V.H., Gerlach I., Jork R., Trentz O., Kossmann T., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2001). Upregulation of ICAM-1 and MCP-1 but not of MIP-2 and sensorimotor deficit in response to traumatic axonal injury in rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 63, 438–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherbel U., Raghupathi R., Nakamura M., Saatman K.E., Trojanowski J.Q., Neugebauer E., Marino M.W., and McIntosh T.K. (1999). Differential acute and chronic responses of tumor necrosis factor-deficient mice to experimental brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 8721–8726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiozaki T., Hayakata T., Tasaki O., Hosotubo H., Fuijita K., Mouri T., Tajima G., Kajino K., Nakae H., Tanaka H., Shimazu T., and Sugimoto H. (2005). Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of anti-inflammatory mediators in early-phase severe traumatic brain injury. Shock 23, 406–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefini R., Catenacci E., Piva S., Sozzani S., Valerio A., Bergomi R., Cenzato M., Mortini P., and Latronico N. (2008). Chemokine detection in the cerebral tissue of patients with posttraumatic brain contusions. J. Neurosurg. 108, 958–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takamiya M., Fujita S., Saigusa K., and Aoki Y. (2007). Simultaneous detections of 27 cytokines during cerebral wound healing by multiplexed bead-based immunoassay for wound age estimation. J. Neurotrauma 24, 1833–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valles A., Grijpink-Ongering L., de Bree F.M., Tuinstra T., and Ronken E. (2006). Differential regulation of the CXCR2 chemokine network in rat brain trauma: implications for neuroimmune interactions and neuronal survival. Neurobiol. Dis. 22, 312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whalen M.J., Carlos T.M., Kochanek P.M., Wisniewski S.R., Bell M.J., Clark R.S., DeKosky S.T., Marion D.W., and Adelson P.D. (2000). Interleukin-8 is increased in cerebrospinal fluid of children with severe head injury. Crit. Care Med. 28, 929–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter C.D., Pringle A.K., Clough G.F., and Church M.K. (2004). Raised parenchymal interleukin-6 levels correlate with improved outcome after traumatic brain injury. Brain 127, 315–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clausen F., Hanell A., Israelsson C., Hedin J., Ebendal T., Mir A.K., Gram H., and Marklund N. (2011). Neutralization of interleukin-1beta reduces cerebral edema and tissue loss and improves late cognitive outcome following traumatic brain injury in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 110–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinz E.H., Kochanek P.M., Dixon C.E., Clark R.S., Carcillo J.A., Schiding J.K., Chen M., Wisniewski S.R., Carlos T.M., Williams D., DeKosky S.T., Watkins S.C., Marion D.W., and Billiar T.R. (1999). Inducible nitric oxide synthase is an endogenous neuroprotectant after traumatic brain injury in rats and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 647–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchinson P.J., O'Connell M.T., Rothwell N.J., Hopkins S.J., Nortje J., Carpenter K.L., Timofeev I., Al-Rawi P.G., Menon D.K., and Pickard J.D. (2007). Inflammation in human brain injury: intracerebral concentrations of IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, and their endogenous inhibitor IL-1ra. J. Neurotrauma 24, 1545–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foley L.M., Hitchens T.K., Melick J.A., Bayır H., Ho C., and Kochanek P.M. (2008). Effect of inducible nitric oxide synthase on cerebral blood flow after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Neurotrauma 25, 299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kochanek P.M., Vagni V.A., Janesko K.L., Washington C.B., Crumrine P.K., Garman R.H., Jenkins L.W., Clark R.S., Homanics G.E., Dixon C.E., Schnermann J., and Jackson E.K. (2006). Adenosine A1 receptor knockout mice develop lethal status epilepticus after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26, 565–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denker S.P., Ji S., Dingman A., Lee S.Y., Derugin N., Wendland M.F., and Vexler Z.S. (2007). Macrophages are comprised of resident brain microglia not infiltrating peripheral monocytes acutely after neonatal stroke. J. Neurochem. 100, 893–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clendenen T.V., Arslan A.A., Lokshin A.E., Idahl A., Hallmans G., Koenig K.L., Marrangoni A.M., Nolen B.M., Ohlson N., Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A., and Lundin E. (2010). Temporal reliability of cytokines and growth factors in EDTA plasma. BMC Res. Notes 3, 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maegele M., Sauerland S., Bouillon B., Schafer U., Trubel H., Riess P., and Neugebauer E.A. (2007). Differential immunoresponses following experimental traumatic brain injury, bone fracture and “two-hit”-combined neurotrauma. Inflamm. Res. 56, 318–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seok J., Warren H.S., Cuenca A.G., Mindrinos M.N., Baker H.V., Xu W., Richards D.R., McDonald-Smith G.P., Gao H., Hennessy L., Finnerty C.C., Lopez C.M., Honari S., Moore E.E., Minei J.P., Cuschieri J., Bankey P.E., Johnson J.L., Sperry J., Nathens A.B., Billiar T.R., West M.A., Jeschke M.G., Klein M.B., Gamelli R.L., Gibran N.S., Brownstein B.H., Miller-Graziano C., Calvano S.E., Mason P.H., Cobb J.P., Rahme L.G., Lowry S.F., Maier R.V., Moldawer L.L., Herndon D.N., Davis R.W., Xiao W., and Tompkins R.G. (2013). Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 3507–3512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akkose S., Ozgurer A., Bulut M., Koksal O., Ozdemir F., and Ozguc H. (2007). Relationships between markers of inflammation, severity of injury, and clinical outcomes in hemorrhagic shock. Adv. Ther. 24, 955–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama Y., Kitchens W.C., Toth B., Schwacha M.G., Rue L.W., III, Bland K.I., and Chaudry I.H. (2004). Role of IL-10 in regulating proinflammatory cytokine release by Kupffer cells following trauma-hemorrhage. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G942–G946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woiciechowsky C., Asadullah K., Nestler D., Eberhardt B., Platzer C., Schoning B., Glockner F., Lanksch W.R., Volk H.D., and Docke W.D. (1998). Sympathetic activation triggers systemic interleukin-10 release in immunodepression induced by brain injury. Nat. Med. 4, 808–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dziedzic T., Slowik A., and Szczudlik A. (2004). Nosocomial infections and immunity: lesson from brain-injured patients. Crit. Care 8, 266–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kline A.E., Bolinger B.D., Kochanek P.M., Carlos T.M., Yan H.Q., Jenkins L.W., Marion D.W., and Dixon C.E. (2002). Acute systemic administration of interleukin-10 suppresses the beneficial effects of moderate hypothermia following traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 937, 22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knoblach S.M., and Faden A.I. (1998). Interleukin-10 improves outcome and alters proinflammatory cytokine expression after experimental traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 153, 143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park K.W., Lee H.G., Jin B.K., and Lee Y.B. (2007). Interleukin-10 endogenously expressed in microglia prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced neurodegeneration in the rat cerebral cortex in vivo. Exp. Mol. Med. 39, 812–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bye N., Habgood M.D., Callaway J.K., Malakooti N., Potter A., Kossmann T., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2007). Transient neuroprotection by minocycline following traumatic brain injury is associated with attenuated microglial activation but no changes in cell apoptosis or neutrophil infiltration. Exp. Neurol. 204, 220–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Semple B.D., Bye N., Rancan M., Ziebell J.M., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2010). Role of CCL2 (MCP-1) in traumatic brain injury (TBI): evidence from severe TBI patients and CCL2–/– mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 769–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black K.L., Hanks R.A., Wood D.L., Zafonte R.D., Cullen N., Cifu D.X., Englander J., and Francisco G.E. (2002). Blunt versus penetrating violent traumatic brain injury: frequency and factors associated with secondary conditions and complications. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 17, 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kossmann T., Stahel P.F., Lenzlinger P.M., Redl H., Dubs R.W., Trentz O., Schlag G., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (1997). Interleukin-8 released into the cerebrospinal fluid after brain injury is associated with blood-brain barrier dysfunction and nerve growth factor production. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 17, 280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hausmann E.H., Berman N.E., Wang Y.Y., Meara J.B., Wood G.W., and Klein R.M. (1998). Selective chemokine mRNA expression following brain injury. Brain Res. 788, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Israelsson C., Wang Y., Kylberg A., Pick C.G., Hoffer B.J., and Ebendal T. (2009). Closed head injury in a mouse model results in molecular changes indicating inflammatory responses. J. Neurotrauma 26, 1307–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rhodes J.K., Sharkey J., and Andrews P.J. (2009). The temporal expression, cellular localization, and inhibition of the chemokines MIP-2 and MCP-1 after traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 26, 507–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rappert A., Bechmann I., Pivneva T., Mahlo J., Biber K., Nolte C., Kovac A.D., Gerard C., Boddeke H.W., Nitsch R., and Kettenmann H. (2004). CXCR3-dependent microglial recruitment is essential for dendrite loss after brain lesion. J. Neurosci. 24, 8500–8509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perrin F.E., Lacroix S., Aviles-Trigueros M., and David S. (2005). Involvement of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha and interleukin-1beta in Wallerian degeneration. Brain 128, 854–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Semple B.D., Kossmann T., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2010). Role of chemokines in CNS health and pathology: a focus on the CCL2/CCR2 and CXCL8/CXCR2 networks. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 459–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szmydynger-Chodobska J., Strazielle N., Zink B.J., Ghersi-Egea J.F., and Chodobski A. (2009). The role of the choroid plexus in neutrophil invasion after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 29, 1503–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rancan M., Bye N., Otto V.I., Trentz O., Kossmann T., Frentzel S., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2004). The chemokine fractalkine in patients with severe traumatic brain injury and a mouse model of closed head injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 24, 1110–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donnelly D.J., Longbrake E.E., Shawler T.M., Kigerl K.A., Lai W., Tovar C.A., Ransohoff R.M., and Popovich P.G. (2011). Deficient CX3CR1 signaling promotes recovery after mouse spinal cord injury by limiting the recruitment and activation of Ly6Clo/iNOS+ macrophages. J. Neurosci. 31, 9910–9922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeWitt D.S., and Prough D.S. (2009). Blast-induced brain injury and posttraumatic hypotension and hypoxemia. J. Neurotrauma 26, 877–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodman M.D., Makley A.T., Huber N.L., Clarke C.N., Friend L.A., Schuster R.M., Bailey S.R., Barnes S.L., Dorlac W.C., Johannigman J.A., Lentsch A.B., and Pritts T.A. (2011). Hypobaric hypoxia exacerbates the neuroinflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. J. Surg. Res. 165, 30–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alam H.B., Stanton K., Koustova E., Burris D., Rich N., and Rhee P. (2004). Effect of different resuscitation strategies on neutrophil activation in a swine model of hemorrhagic shock. Resuscitation 60, 91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watters J.M., Brundage S.I., Todd S.R., Zautke N.A., Stefater J.A., Lam J.C., Muller P.J., Malinoski D., and Schreiber M.A. (2004). Resuscitation with lactated Ringer's does not increase inflammatory response in a Swine model of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. Shock 22, 283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hensler T., Heinemann B., Sauerland S., Lefering R., Bouillon B., Andermahr J., and Neugebauer E.A. (2003). Immunologic alterations associated with high blood transfusion volume after multiple injury: effects on plasmatic cytokine and cytokine receptor concentrations. Shock 20, 497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Widera D., Holtkamp W., Entschladen F., Niggemann B., Zanker K., Kaltschmidt B., and Kaltschmidt C. (2004). MCP-1 induces migration of adult neural stem cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 83, 381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cole J.T., Yarnell A., Kean W.S., Gold E., Lewis B., Ren M., McMullen D.C., Jacobowitz D.M., Pollard H.B., O'Neill J.T., Grunberg N.E., Dalgard C.L., Frank J.A., and Watson W.D. (2011). Craniotomy: true sham for traumatic brain injury, or a sham of a sham? J. Neurotrauma 28, 359–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khuman J., Meehan W.P., Zhu X., Qiu J., Hoffmann U., Zhang J., Giovannone E., Lo E.H., and Whalen M.J. (2011). Tumor necrosis factor alpha and Fas receptor contribute to cognitive deficits independent of cell death after concussive traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 778–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yan E.B., Hellewell S.C., Bellander B.M., Agapomaa D.A., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2011). Post-traumatic hypoxia exacerbates neurological deficit, neuroinflammation and cerebral metabolism in rats with diffuse traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 147–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ziebell J.M., Bye N., Semple B.D., Kossmann T., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2011). Attenuated neurological deficit, cell death and lesion volume in Fast-mutant mice is associated with altered neuroinflammation following traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 1414, 94–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kochanek P.M., Dixon C.E., Shellington D.K., Shin S.S., Bayır H., Jackson E.K., Kagan V.E., Yan H.Q., Swauger P.V., Parks S.A., Ritzel D.V., Bauman R., Clark R.S., Garman R.H., Bandak F., Ling G., and Jekins L.W. (2013). Screening of biochemical and molecular mechanisms of secondary injury and repair in the brain after experimental blast-induced traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 30, 920–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]