Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to assess satisfaction with specific aspects of care for acute neck pain and explore the relationship between satisfaction with care, neck pain and global satisfaction.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of patient satisfaction from a randomized trial of spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) delivered by doctors of chiropractic, home exercise and advice (HEA) delivered by exercise therapists, and medication (MED) prescribed by a medical physician for acute/subacute neck pain. Differences in satisfaction with specific aspects of care were analyzed using a linear mixed model. The relationship between specific aspects of care and 1) change in neck pain (primary outcome of the randomized trial) and 2) global satisfaction were assessed using Pearson’s correlation and multiple linear regression.

Results

Individuals receiving SMT or HEA were more satisfied with the information and general care received than MED group participants. SMT and HEA groups reported similar satisfaction with information provided during treatment; however, the SMT group was more satisfied with general care. Satisfaction with general care (r=−0.75 to −0.77, R2= 0.55 to 0.56) had a stronger relationship with global satisfaction compared to satisfaction with information provided (r=−0.65 to 0.67, R2=0.39 to 0.46). The relationship between satisfaction with care and neck pain was weak (r=0.17 to 0.38, R2=0.08 to 0.21).

Conclusions

Individuals with acute/subacute neck pain were more satisfied with specific aspects of care from SMT delivered by doctors of chiropractic or HEA interventions compared to MED prescribed by a medical physician.

Keywords: Neck Pain, Patient Satisfaction, Musculoskeletal Manipulations, Exercise Therapy, Pharmaceutical Preparations, Clinical Trial, Chiropractic

Introduction

Neck pain is one of the most commonly reported health complaints in primary care settings.1,2 As concern for costs and side effects related to treating spinal pain conditions continues to grow, the search for effective, patient-centered treatments has become paramount. Patient satisfaction has become a widely advocated means for measuring patients’ preferences and views related to treatment quality in clinical practice.3 Further, it is recommended as a core outcome domain for chronic pain clinical trials by the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) group.4

A large percentage of healthcare visits are made to physicians, chiropractors and physical therapists, who use a range of interventions to manage neck complaints.5 Although commonly used for the management of acute or subacute neck pain, systematic reviews have found only limited to low quality evidence for spinal manipulation, exercise, and medications.6–8 Recently, in one of the first large randomized trials investigating spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) for acute and subacute neck pain, our group found patients receiving SMT experienced significantly greater reductions in pain than those receiving medication in the short and long term.9 No significant group differences were found between SMT and home exercise for most outcomes, including pain. An exception was global satisfaction, with the SMT group significantly more satisfied compared to the home exercise and medication groups, and the home exercise group more satisfied than those who received medication. The satisfaction related findings, while secondary, are potentially important, especially given the lack of research that is currently available examining patient satisfaction in the existing acute neck pain literature.6 Further, it is not known if there were specific aspects of care that informed patients’ global satisfaction and if these differed by treatment. Such insights may provide important information that can affect the implementation of research findings into clinical practice and the design of future patient-centered research.

While satisfaction outcomes are growing in popularity, recent studies and commentaries have questioned the interpretation of patient satisfaction and its utility in both healthcare and clinical research settings.10,11 Fenton et al. examined the relationship between patient satisfaction, health care expenditures, and health using the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS).10 Surprisingly, they found increased satisfaction is associated with higher medical expenditures and mortality. Similar but less extreme findings are emerging in the spinal pain literature, which find improved patient satisfaction with increased diagnostic tests and treatment, regardless of clinical outcomes.12,13

In light of the emerging questions about utility of satisfaction as an outcome measure and findings from our recent study,9 we sought to further explore the patient satisfaction domain. The purpose of this paper was to assess: 1. Treatment group differences in satisfaction with specific aspects of care in acute neck pain patients receiving SMT, home exercise, and medication as measured by a multi-dimensional satisfaction questionnaire; and 2. The relationship between specific aspects of satisfaction with care and both change in neck pain (primary outcome measure in parent randomized clinical trial) and global satisfaction (secondary outcome).

Methods

This study used patient satisfaction outcomes collected during a randomized clinical trial conducted from 2001 to 2007 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. A more thorough description of the study population, methodology, and primary results has previously been published.9 A brief description of the clinical trial is provided here. The institutional review boards at Northwestern Health Sciences University and Hennepin County Medical Center approved the study and all subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (R01 AT000707) and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00029770).

Population

Participants were 18 to 65 years of age with mechanical, nonspecific neck pain (Grade I or II according to the Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on Neck Pain’s classification14) of 2 to 12 weeks duration. Participants with health conditions not amenable to study treatments or severe disabling health problems were excluded.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned to treatment using permuted blocks of different sizes. The allocation sequence was prepared off-site by the study statistician prior to enrollment and was concealed from investigators, treatment providers, and other study staff by using consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

Interventions

Spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) was provided by licensed chiropractors with a minimum of 5 years clinical experience at a university associated research clinic. Treatment visits lasted 15–20 minutes and primarily consisted of high velocity, low amplitude joint manipulation (Diversified technique). Low velocity joint mobilization was also allowed if indicated. Other therapies including light soft tissue massage and assisted stretching; heat or cold packs were used as necessary to facilitate the SMT. The specific areas of treatment and number of visits were determined by the treating chiropractor over a 12-week treatment phase. Advice to stay active or modify activity was provided as needed.

Medication (MED) was provided by a licensed medical physician at a pain management clinic and consisted of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or both as a first line of therapy. Narcotic medications and muscle relaxants were prescribed to participants who failed to respond to initial treatment. The number of visits and choice of medication was at the physician’s discretion over the 12-week treatment period. Advice to stay active or modify activity was provided as needed.

Home exercise and advice (HEA) was provided by exercise therapists at a university affiliated research clinic. Participants attended two, one-hour visits focusing on self-mobilization exercises for the neck and shoulders over a two week period. Participants were instructed to perform 5 to 10 repetitions of the exercises at home 6 to 8 times per day. The home exercises were supplemented with information and advice on neck pain prognosis and ergonomic advice.15

Instruments

Participants completed self-report questionnaires at multiple time points. The time points relevant to this manuscript were collected at the end of the intervention phase (week 12) and long term follow up (week 52). Participants completed all self-reported outcomes independently without the influence of investigators, study staff, or treatment providers. Baseline and week 12 questionnaires were administered at the university associated research clinic. Week 52 questionnaires were completed by mail.

Satisfaction with seven specific aspects of care was captured using a multi-dimensional instrument previously described by Cherkin et al.16 (Appendix 1) Four items on the instrument query satisfaction with information received (cause, prognosis, activities to hasten recovery, and prevention) and the other three items cover satisfaction with general care (provider concern, quality of treatment recommendations, and overall care). Each item is scored on a 1–5 scale (poor, fair, good, very good, excellent). The instrument consists of two subscales (information and general care) which are scored by summing the relevant items and transforming the results to 0–100 scales (0 = worst, 100 = best). Neck pain (primary outcome for the randomized clinical trial) was measured with an 11-box numerical rating scale (0 = no pain; 10 = worst possible pain). Global satisfaction (a secondary measure also reported previously) was assessed by asking participants to rate their overall satisfaction with care on a 1–7 scale (1= completely satisfied, couldn’t be better; 4 = neither satisfied or dissatisfied; 7 = completely dissatisfied, couldn’t be worse).

Appendix 1.

Multi-dimensional satisfaction instrument developed by Cherkin et al.

| Poor | Fair | Good | Very Good |

Excellent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. The information you received regarding the cause of your neck pain. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| b. The information you received regarding the prognosis of your neck pain. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| c. The information you received regarding activities that would hasten your recovery. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| d. The information you received concerning prevention of future neck problems. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| e. The concern shown by your doctor, chiropractor or therapist. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| f. The quality of the treatment recommendations. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| g. The overall care you received for your neck pain. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Please rate the following aspects of the care you have received in this study: (Circle one number for each letter a. through g.)

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive results for satisfaction with care using the two subscales of the multi-dimensional satisfaction questionnaire (information and general care) are presented using means and standard deviations. Two approaches were used to assess treatment group differences. First, we used a linear mixed model to determine group differences in the short (following the 12 week intervention phase) and long term (52 weeks) using the information and general care subscales of the multi-dimensional satisfaction questionnaire. Second, we calculated the percentage of participants responding to each of the 7 items of the instrument at the end of the intervention phase. To facilitate interpretation, the original responses were categorized as satisfied (i.e., responses of ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’), neutral (i.e., responses of ‘good’), or unsatisfied (i.e., responses of ‘poor’ or ‘fair’). A Chi-square test was then used to test for group differences. Two approaches were used to assess the relationship between satisfaction with specific aspects of care and 1) change in neck pain (primary outcome of the randomized clinical trial) and 2) global satisfaction (secondary outcome). First, Pearson’s correlations for 1) change in neck pain and 2) global satisfaction were calculated for each of the 7 instrument items and subscales at weeks 12 and 52. Strengths of association were characterized as negligible (0.00 to 0.30), low (0.30 to 0.50), moderate (0.50 to 0.70), high (0.70 to 0.90), and very high (0.90 to 1.00).17 Additionally, multiple linear regression models were specified using 1) change in neck pain and 2) global satisfaction as the dependent variables at weeks 12 and 52 to determine the amount of variance explained by individual items comprising the two subscales and overall instrument. Individual items from the satisfaction questionnaire were included as independent variables. The question describing satisfaction with overall care within the multidimensional satisfaction questionnaire was excluded from the regression model for global satisfaction. The amount of variance explained (adjusted R2) by each model was calculated.

Results

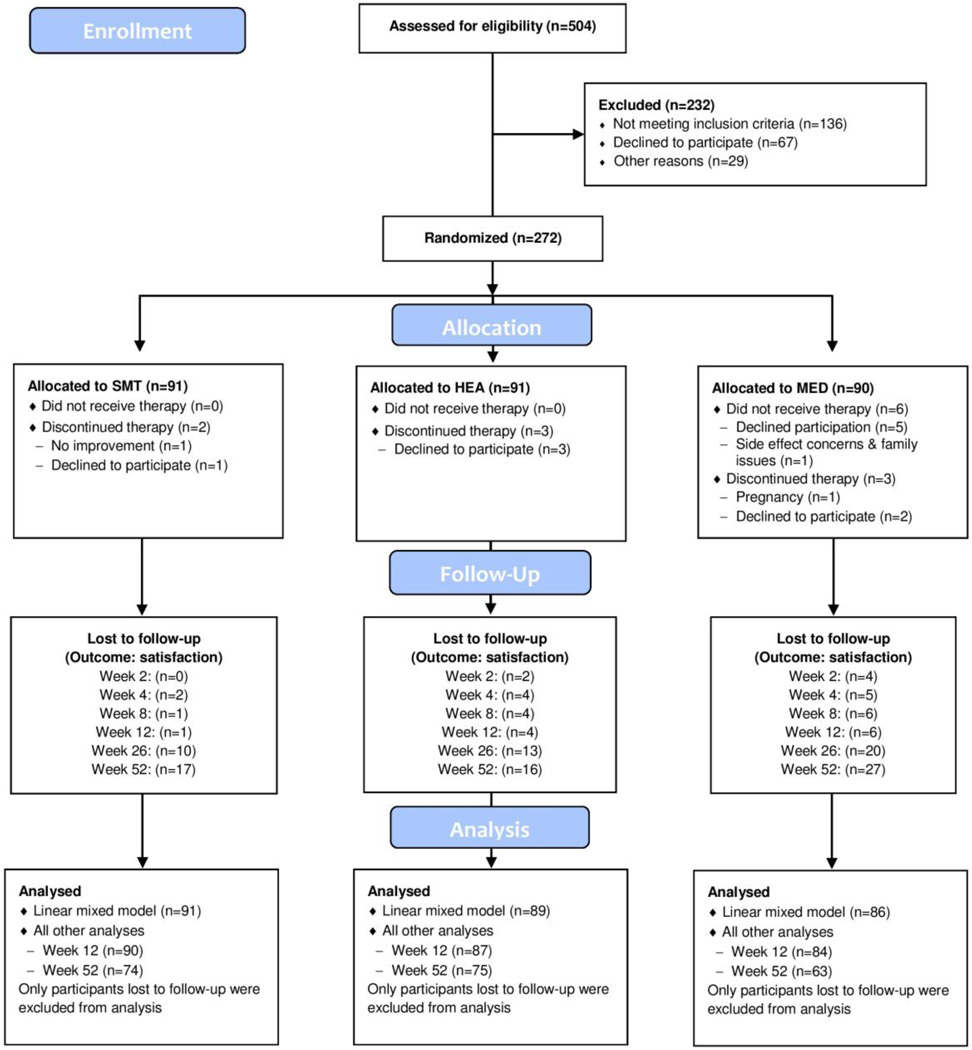

Of the 272 of the original participants who were randomized, 261 completed the multidimensional satisfaction instrument in addition to the primary and other secondary outcomes at the end of the study intervention phase (12 weeks). Figure 1 details the number of participants who were recruited, randomly assigned, compliant with treatment and analyzed. At week 52 (end of follow up), 15 fewer participants completed the multi-dimensional satisfaction instrument and other secondary outcomes (n=212) relative to the primary outcome, pain (n=227). Key baseline characteristics of randomized participants are detailed in Table 1. Further details regarding baseline demographics, treatment compliance, and reasons for study withdrawal are provided in the primary publication.9

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram for satisfaction outcomes

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| SMT | HEA | MED | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 91 | 91 | 90 |

| Mean age (SD) | 48.3 (15.2) | 48.6 (12.5) | 46.8 (12.2) |

| Women, % | 58.2 | 65.9 | 72.2 |

| Mean neck pain duration (SD), wk | 7.0 (3.2) | 6.8 (3.2) | 7.4 (3.0) |

| Radiating pain to upper extremity, % | 24.2 | 23.3 | 20.0 |

| Mean expectation of change in pain (SD)* | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) |

| Mean neck pain (SD)‡ | 5.27 (1.57) | 5.05 (1.64) | 4.93 (1.49) |

On a scale of 1 (much better) to 5 (much worse)

On a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain)

Means and standard deviations for the two satisfaction subscales (information and general care) are provided in Table 2. Participants in all three treatment groups reported higher levels of satisfaction on the general care subscale compared to the information subscale.

Table 2.

Satisfaction outcomes

| Satisfaction | SMT | HEA | MED |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 | n=90 | n=87 | n=84 |

| Information | 68.96 (26.10) | 72.84 (21.12) | 57.66 (26.56) |

| General Care | 90.00 (13.41) | 83.91 (16.95) | 78.47 (22.67) |

| Week 52 | n=74 | n=75 | N=63 |

| Information | 68.07 (25.85) | 70.42 (23.05) | 54.17 (26.96) |

| General Care | 86.15 (16.97) | 80.89 (20.81) | 69.97 (25.73) |

Mean satisfaction (SD); 0–100 scale, larger values indicate higher satisfaction

Treatment Group Differences

Table 3 summarizes the results of the mixed model analyses exploring treatment group differences in the two satisfaction subscales. Both SMT and HEA groups were significantly more satisfied than the MED group in terms of satisfaction with information and general care, in both the short and long term. The SMT group was also more satisfied with the general care received than the HEA group (at 12 and 52 weeks). No significant differences were found between SMT and HEA in terms of the information subscale at both time points.

Table 3.

Treatment differences

| Satisfaction | SMT-MED | HEA-MED | SMT-HEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 | |||

| Information | 11.64 (5.52 to 17.76) | 15.28 (9.13 to 21.43) | −3.64 (−9.71 to 2.43) |

| General Care | 11.66 (6.51 to 16.81) | 5.45 (0.26 to 10.63) | 6.22 (1.10 to 11.33) |

| Week 52 | |||

| Information | 13.58 (6.99 to 20.17) | 15.46 (8.87 to 22.05) | −1.88 (−8.27 to 4.52) |

| General Care | 16.42 (10.86 to 21.98) | 11.02 (5.47 to 16.57) | 5.40 (0.01 to 10.79) |

Difference in satisfaction on 0–100 scale (95% confidence interval)

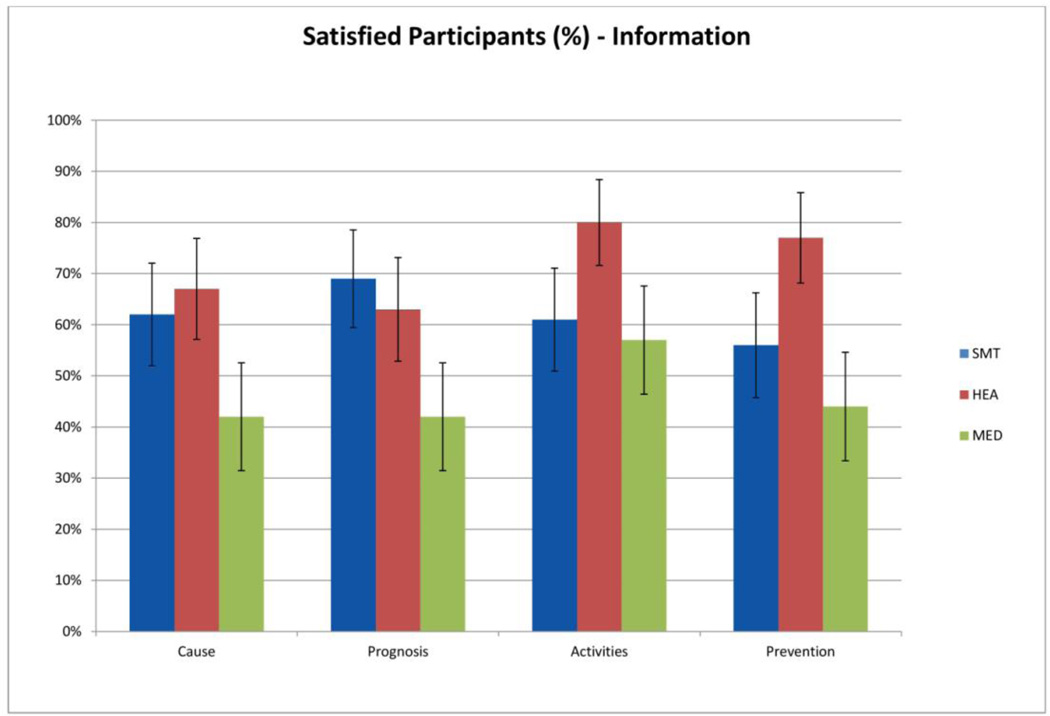

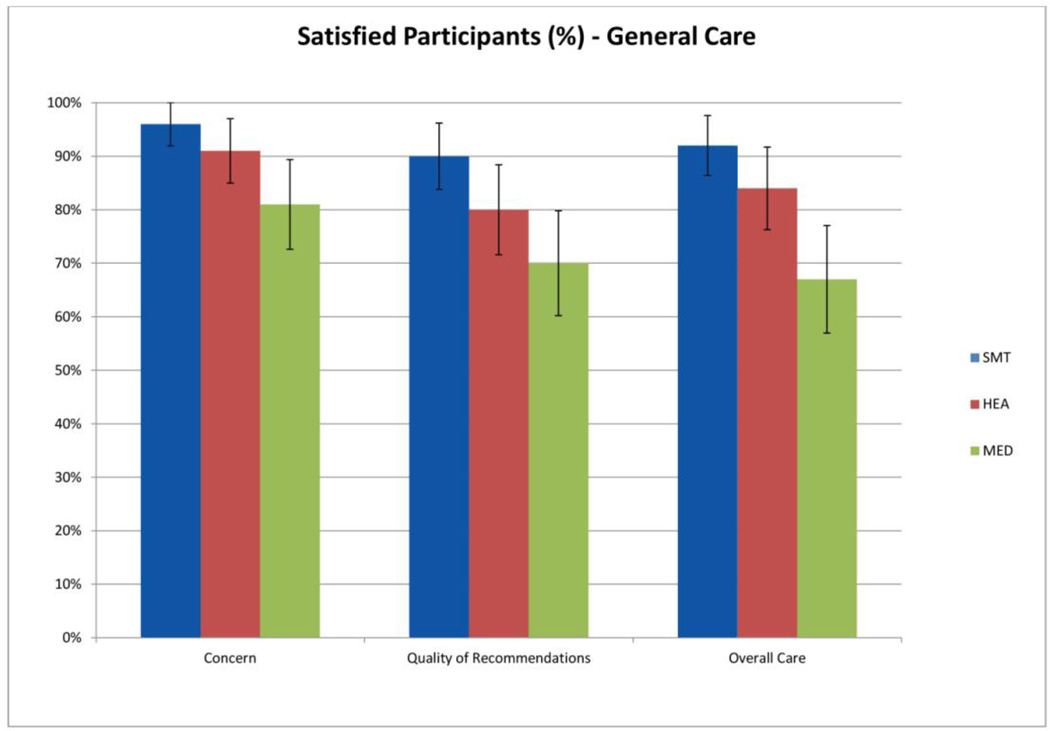

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the proportion of patients in each treatment group who were satisfied with specific items related to the information (Figure 2) and general care (Figure 3). Greater proportions of patients in all three treatment groups consistently reported being satisfied with general care items (67%–96%) compared to information items (42%–80%). For all items of the multidimensional questionnaire, the MED group consistently had fewer satisfied participants compared to the SMT and HEA groups.

Figure 2.

Percentage of satisfied participants with information received by treatment group (95% confidence intervals)

Figure 3.

Percentage of satisfied participants with general care received by treatment group (95% confidence intervals)

Results of the Chi-squared analyses examining the individual items for both satisfaction subscales are displayed in Table 4. Both the SMT and HEA groups had similarly more participants who were satisfied with information regarding cause (SMT=62%, HEA=67%, MED=42%, χ2=15.44, p=0.004) and prognosis (SMT=69%, HEA=63%, MED=42%, χ2=16.17, p=0.003). The HEA group had the greatest number of participants satisfied with information regarding activities that would hasten recovery (SMT=61%, HEA=80%, MED=57%, χ2=12.47, p=0.014) and the prevention of future neck problems (SMT=56%, HEA=77%, MED=44%, χ2=24.25, p=0.0001).

Table 4.

Percentages of responses to individual items on the instrument

| Week 12 | SMT (n=90) | HEA (n=87) | MED (n=84) |

χ2 | p- value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information subscale | ||||||

| Cause | Satisfied | 62% | 67% | 42% | 15.44 | 0.004 |

| Neutral | 23% | 20% | 26% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 14% | 14% | 32% | |||

| Prognosis | Satisfied | 69% | 63% | 42% | 16.17 | 0.003 |

| Neutral | 16% | 24% | 31% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 16% | 13% | 27% | |||

| Activities | Satisfied | 61% | 80% | 57% | 12.47 | 0.014 |

| Neutral | 26% | 14% | 26% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 13% | 6% | 17% | |||

| Prevention | Satisfied | 56% | 77% | 44% | 24.25 | 0.0001 |

| Neutral | 24% | 13% | 20% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 20% | 10% | 36% | |||

| General Care subscale | ||||||

| Concern | Satisfied | 96% | 91% | 81% | 11.88 | 0.018 |

| Neutral | 4% | 9% | 17% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 0% | 0% | 2% | |||

| Quality | Satisfied | 90% | 80% | 70% | 13.37 | 0.010 |

| Neutral | 9% | 17% | 21% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 1% | 2% | 8% | |||

| Overall Care | Satisfied | 92% | 84% | 67% | 21.80 | 0.0002 |

| Neutral | 8% | 13% | 23% | |||

| Unsatisfied | 0% | 3% | 11% | |||

The item with the greatest number of satisfied patients was the concern shown by the provider and was most frequently reported by those in the SMT and HEA groups (SMT=96%, HEA=91%, MED=81%, χ2=11.88, p=0.018). The SMT group had the greatest number of satisfied patients in regards to the quality of treatment recommendations (SMT=90%, HEA=80%, MED=70%, χ2=13.37, p=0.010) and overall care received (SMT=92%, HEA=84%, MED=67%, χ2=21.80, p=0.0002).

Noteworthy is that approximately one third of the MED group were unsatisfied with three of the four items in the information subscale (cause, prognosis, and prevention). This was in contrast to the SMT and HEA groups who had fewer unsatisfied participants ranging from 14–20% for the SMT group and 10–14% for the HEA group for the same items.

Relationships: Specific Aspects of Satisfaction, Pain, and Global Satisfaction

Table 5 displays the results examining the relationship between specific aspects of satisfaction, pain, and global satisfaction. The correlations between specific aspects of satisfaction and change in neck pain at 12 weeks was negligible to low for both information (r=0.23 to 0.32) and general care subscale items (r=0.19 to 0.38). At 52 weeks, similar but diminished correlations were observed, with negligible correlations for information (r=0.18 to 0.25) and general care items (r=0.17 to 0.29). The strongest associations between specific satisfaction items and change in neck pain were for quality of care (r=0.38) in the short term, and overall care in the long term (r=0.29). Conversely, the weakest associations were for the concern shown by the provider in the short (r=0.19) and long term (r=0.17).

Table 5.

Correlation and R2

| Week 12 | Week 52 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ Neck Pain |

Global Satisfaction |

Δ Neck Pain | Global Satisfaction | |

|

Correlation (Pearson) Information subscale |

.304 | −.652 | .231 | −.672 |

| Cause | .227 | −.510 | .188 | −.591 |

| Prognosis | .266 | −.566 | .180 | −.650 |

| Activities | .262 | −.590 | .254 | −.587 |

| Prevention | .320 | −.555 | .214 | −.599 |

|

General Care subscale |

.346 | −.752 | .249 | −.767 |

| Concern | .190 | −.497 | .169 | −.623 |

| Quality | .384 | −.750 | .229 | −.736 |

| Overall Care | .340 | −.756 | .294 | −.781 |

| Adjusted R2 | ||||

| Information Subscale | .091 | .394 | .047 | .455 |

| General Care Subscale |

.151 | .560 | .043 | .547 |

| Total Instrument | .212 | .595 | .083 | .575 |

The correlations between specific aspects of satisfaction and global satisfaction were more pronounced. The reported correlation values are negative due to opposite weighting of the two scales. At 12 weeks, moderate correlations were observed for the information subscale items (r= −0.51 to −0.59) and moderate to high correlations were found for general care subscale items (r= −0.50 to −0.76). Long term associations (week 52) remained moderate for items in the information (r= −0.59 to −0.65) subscale and moderate to high for the general care subscale (r= −0.62 to −0.78). Individual items with the strongest association to global satisfaction were quality of care (r= −0.74 to −0.75) and overall care (r= −0.76 to −0.78) in the short and long term. Results of the multiple linear regression analysis found that information and general care subscales accounted for a small amount of total variability when examining change in neck pain in both the short and long term (R2 = 0.04 to 0.15). Including all items of the multi-dimensional satisfaction questionnaire only explained 21% of total variability at week 12 and 8% at week 52 for change in neck pain (Table 5).

Multiple regression analysis also found that general care accounted for a larger amount of variability (R2 = 0.56 to 0.55) than information (R2 = 0.39 to 0.46) when predicting global satisfaction at weeks 12 and 52. Including all items of the multi-dimensional satisfaction questionnaire (except overall care, a similar construct to global satisfaction) accounted for 58 to 60% of total variability in the short and long term (Table 5).

Discussion

While patient satisfaction is a commonly promoted outcome measure,4,18 its utility and interpretation has become somewhat controversial.10,11 The results of these secondary analyses provide a better understanding of the issues related to satisfaction with three common treatment approaches for acute neck pain, providing additional context for interpreting the primary study’s findings and gleaning a better understanding of how patients experienced the interventions.9 The primary results of our previously reported randomized clinical trial found that SMT patients experienced significantly greater pain reduction than MED patients; SMT patients also reported greater global satisfaction than HEA, and both groups were more globally satisfied than the MED group.9 Through secondary analyses exploring specific aspects of satisfaction, we confirmed a consistent advantage for SMT and HEA over MED in terms of satisfaction in sub-domains related to general care (which included provider concern, quality of treatment recommendations, and overall care) and information provided (including cause, prognosis, activities to hasten recovery, and prevention). Patients receiving SMT were also more satisfied with general care than the HEA group. The secondary analyses also revealed the HEA group to be as satisfied with information received as the SMT group. The HEA group was most satisfied with specific information related to activities to hasten recovery and prevent future neck pain. These finding, while not entirely surprising given the information-rich nature of the HEA intervention, are noteworthy. Systematic reviews and recent qualitative work have found that patients with spinal pain appreciate information regarding the cause of their symptoms and ways to manage their condition; further, they are frustrated by the lack of such information in clinical encounters.19,20 The results of our secondary analyses suggest HEA as an intervention might offer an advantage in meeting these types of informational needs for acute neck pain patients and should be considered more frequently in clinical practice and future research. We also found acute neck pain patients’ global satisfaction to be largely explained by general care and information related factors (e.g., 60% of the variance) but not entirely. While the findings suggest that these factors are important, they also suggest that patients consider additional satisfaction-related factors not included in the multidimensional satisfaction instrument used in this study. Indeed, other studies have found ‘process related factors’ (e.g., how care is delivered) including treatment format, the nature of the patient-provider interaction, as well as outcomes, are important domains considered by patients when assessing their satisfaction.21–25 Future qualitative and quantitative studies exploring the full range of satisfaction related factors that inform acute neck pain patients’ preferences and perspectives, including their relationship to other important outcomes like healthcare utilization and costs are needed.

Somewhat surprising is our finding that change in pain is poorly explained by satisfaction with general care and information in this acute neck pain population (21% of variance). This finding confirms the observations of others that satisfaction with treatment should not be directly equated with effectiveness (as defined by impact on pain, disability, and other important outcomes).10–12 Rather, satisfaction with care is perhaps better viewed as the patients’ reflection on the treatment experience, illustrating a range of perspectives regarding what they actually receive, how it is delivered, and how they experienced it.21

This study also highlights general issues regarding how to best measure patient satisfaction. One commonly used approach (used in the primary study from which this work is derived9) is to use a global scale of satisfaction. While appealing in its simplicity, the global nature of such scales can mask individual satisfaction related factors such as the ones identified in this secondary analysis. Further, it is possible for patients to be satisfied with some aspects of care and dissatisfied with others, which will not be clearly identified with a global measure. Incomplete understanding of what aspects of care patients find satisfying and dissatisfying can play an important role in patients’ ability and willingness to engage in specific treatments. Consequently, multidimensional evaluations of satisfaction should be considered for researchers and clinicians desiring to fully understand the patients’ perspectives of care and the potential effect they have on compliance, outcomes, and care-seeking behaviors.26

Satisfaction with care is not routinely measured in clinical research investigating neck pain conditions, despite widespread recommendations to do so.4,6 Previous studies similar to ours did not report patient satisfaction outcomes.27–30 Given the disparate nature of available treatments (e.g., passive versus active therapies, side effect profiles), this is a surprising and important gap.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is that the multidimensional instrument used to measure specific satisfaction related factors was limited to general care and information related domains. Currently there is no consensus as to which satisfaction related instruments should be used in both clinical practice and research as illustrated by the range of satisfaction measures used in neck pain research. Lack of consensus might be explained in part by the fact that patient satisfaction itself as a domain has been poorly researched and is still incompletely understood.23,26,31,32 Qualitative research examining the full range of issues patients consider when determining their satisfaction with care is very much needed to inform the development and choice of appropriate satisfaction measures.

Patient-provider time and attention would be expected to influence patient satisfaction but was not controlled for in this trial and should be considered a possible explanation for observed treatment group differences. However, while the average number of visits in the SMT group was 15.3 compared to 4.8 in the MED group, and 2.0 for the HEA group, the similarity in many of the satisfaction related domains between SMT and HEA suggests that time and attention had a limited affect.

The loss to follow up, particularly at 52 weeks was approximately 20% for the multi-dimensional pain instrument and highest for the MED group. While we can’t be sure of the influence this has on study results, it could cause under- or over-estimations on patient satisfaction. The consistency of results with other outcomes and the primary trial results limits this concern. The exclusion of other variables for the prediction of neck pain and global improvement could be viewed as a limitation. The purpose of this analysis was to determine the contribution of specific items included in the multidimensional satisfaction questionnaire for the prediction of pain and global satisfaction, which required the exclusion of other potentially predictive variables. Another potential limitation is that participants in the SMT and HEA groups completed the satisfaction questionnaire in the same facility where they received treatment, which may explain the higher level of reported satisfaction compared to the MED group. The observed differences in satisfaction at week 52 (all of which were collected by mail) make this unlikely and diminish this concern.

Conclusion

This study provides a greater understanding of satisfaction with care in acute neck pain patients receiving spinal manipulation, home exercise, and advice and medications. A consistent advantage for spinal manipulation and home exercise was identified in terms of satisfaction with general care (including provider concern, quality of treatment recommendations, and overall care) and information provided (including cause, prognosis, activities to hasten recovery, and prevention). Patients receiving spinal manipulation were also more satisfied with general care than the home exercise group. While this secondary analyses also revealed the HEA group to be as satisfied overall with information received as the SMT group, more HEA patients were satisfied with the information received related to activities to hasten recovery and prevention. These results highlight how global satisfaction measures may mask important nuances of how patients view and experience treatments and point to the use of multidimensional satisfaction instruments in future research.

Individuals receiving spinal manipulation therapy from doctors of chiropractic or home exercise were more satisfied with specific aspects of care for acute neck pain compared to medication.

Satisfaction with general care was more strongly related to global satisfaction than satisfaction with information provided during treatment.

Satisfaction with care was weakly associated with changes in neck pain.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

State funding sources (grants, funding sources, equipment, and supplies). Include name and number of grant if available. Clearly state if study received direct NIH or national funding. All sources of funding should be acknowledged in the manuscript.

“Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center For Complementary & Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AT000707 & F32AT007507. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.” The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (R01 AT000707). The primary author, Brent Leininger, is funded through a training award from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (F32AT007507).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

List all potential conflicts of interest for all authors. Include those listed in the ICMJE form. These include financial, institutional and/or other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest. If there is no conflict of interest state none declared.

No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

| Contributorship | For each author, list initials for how the author contributed to this manuscript. List author initials for each relevant category |

| Concept development (provided idea for the research) | BL, RE, GB |

| Design (planned the methods to generate the results) | BL, RE, GB |

| Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript) | BL, RE |

| Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data) | BL, RE |

| Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results) | BL, RE |

| Literature search (performed the literature search) | BL, RE |

| Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript) | BL, RE |

| Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking) | BL, RE, GB |

| Other (list other specific novel contributions) |

Contributor Information

Brent D Leininger, Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies, Northwestern Health Sciences University Bloomington, MN, USA.

Roni Evans, Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies, Northwestern Health Sciences University Bloomington, MN, USA.

Gert Bronfort, Wolfe-Harris Center for Clinical Studies, Northwestern Health Sciences University Bloomington, MN, USA.

Reference List

- 1.Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde GM, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S39–S51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al. Clinical practice implications of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: from concepts and findings to recommendations. Spine. 2008;33:S199–S213. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181644641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne K, Roseman D, Shaller D, Edgman-Levitan S. Analysis & commentary. Measuring patient experience as a strategy for improving primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:921–925. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chevan J, Riddle DL. Factors associated with care seeking from physicians, physical therapists, or chiropractors by persons with spinal pain: a population-based study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:467–476. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kay TM, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, et al. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004250.pub4. CD004250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peloso P, Gross A, Haines T, Trinh K, Goldsmith CH, Burnie S. Medicinal and injection therapies for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000319.pub4. CD000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross A, Miller J, D'Sylva J, et al. Manipulation or mobilisation for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004249.pub3. CD004249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronfort G, Evans R, Anderson AV, Svendsen KH, Bracha Y, Grimm RH. Spinal manipulation, medication, or home exercise with advice for acute and subacute neck pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405–411. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haldeman S. Commentary: is patient satisfaction a reasonable outcome measure? Spine J. 2012;12:1138–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Kerslake R, Miller P, Pringle M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:400–405. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godil SS, Parker SL, Zuckerman SL, et al. Determining the quality and effectiveness of surgical spine care: patient satisfaction is not a valid proxy. Spine J. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, et al. A new conceptual model of neck pain: linking onset, course, and care: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;3:S14–S23. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643efb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenzie R. Treat Your Own Neck. Third Edition ed. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Street JH, Hunt M, Barlow W. Pitfalls of patient education. Limited success of a program for back pain in primary care. Spine. 1996;21:345–355. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199602010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. 5th Edition ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin LA, Nelson EC, Lloyd RC, Nolan TW. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute For Healthcare Improvement; 2007. Whole System Measures. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbeek J, Sengers MJ, Riemens L, Haafkens J. Patient expectations of treatment for back pain: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Spine. 2004;29:2309–2318. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142007.38256.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdermid JC, Walton DM, Miller J. What is the Experience of Receiving Health Care for Neck Pain? Open Orthop J. 2013;7:428–439. doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans R. A Mixed Methods Approach for Evaluating Spinal Manipulation and Exercise for Chronic Neck Pain (Doctoral Dissertation) Odense, DK: University of Southern Denmark; 2013. The meaning of satisfaction: a mixed methods study of chronic neck pain patients receiving exercise-based treatments. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haanstra TM, Hanson L, Evans R, et al. How do low back pain patients conceptualize their expectations regarding treatment? Content analysis of interviews. Eur Spine J. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcinowicz L, Chlabicz S, Grebowski R. Patient satisfaction with healthcare provided by family doctors: primary dimensions and an attempt at typology. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hush JM, Cameron K, Mackey M. Patient satisfaction with musculoskeletal physical therapy care: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2011;91:25–36. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Infante FA, Proudfoot JG, Powell DG, et al. How people with chronic illnesses view their care in general practice: a qualitative study. Med J Aust. 2004;181:70–73. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudak PL, Wright JG. The characteristics of patient satisfaction measures. Spine. 2000;25:3167–3177. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoving JL, Koes BW, de Vet HC, et al. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by a general practitioner for patients with neck pain. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:713–722. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoving JL, de Vet HC, Koes BW, et al. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by the general practitioner for patients with neck pain: long-term results from a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:370–377. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000180185.79382.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pool JJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL, Vlaeyen JW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Is a behavioral graded activity program more effective than manual therapy in patients with subacute neck pain? Results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1017–1024. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c212ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland JA, Glynn P, Whitman JM, Eberhart SL, MacDonald C, Childs JD. Short-term effects of thrust versus nonthrust mobilization/manipulation directed at the thoracic spine in patients with neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87:431–440. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1829–1843. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]