Abstract

Commercially available implantable needle-type glucose sensors for diabetes management are robust analytically but can be unreliable clinically primarily due to tissue-sensor interactions. Here, we present the physical, drug release, and bioactivity characterization of tubular, porous dexamethasone (Dex) releasing polyurethane coatings designed to attenuate local inflammation in the tissue-sensor interface. Porous polyurethane coatings were produced by the salt-leaching/gas-foaming method. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT) showed a controlled porosity and coating thickness. In vitro drug release from coatings monitored over two weeks presented an initial fast release followed by a slower release. Total release from coatings was highly dependent on initial drug loading amount. Functional in vitro testing of glucose sensors deployed with porous coatings against glucose standards demonstrated that highly porous coatings minimally affected signal strength and response rate. Bioactivity of the released drug was determined by monitoring Dex-mediated, dose-dependent apoptosis of human peripheral blood derived monocytes in culture. Acute animal studies were used to determine the appropriate Dex payload for the implanted porous coatings. Pilot short-term animal studies showed that Dex released from porous coatings implanted in rat subcutis attenuated the initial inflammatory response to sensor implantation. These results suggest that deploying sensors with the porous, Dex-releasing coatings is a promising strategy to improve glucose sensor performance.

Keywords: Biosensor, Controlled Drug Release, Porosity, Foreign Body Response, Inflammation, Anti-inflammatory, Dexamethasone, Implant

Introduction

The dominant management strategy for blood sugar control in type I diabetes mellitus is the combination of blood glucose monitoring by finger pricking and manual insulin delivery. These strategies are often inadequate in cases where tight glycemic control is prescribed (1-4). Consequently, there is a pressing need for a closed loop system where real-time changes in glucose levels monitored by a sensor are used to regulate automated insulin delivery (1, 2, 4, 5). Unfortunately, contemporary implantable needle-type glucose sensors that could be used to manage insulin supply can behave unpredictably in vivo.

Often, a sensor that performs robustly and accurately in vitro may upon implantation continue to work adequately, fail acutely, show a steady drift, or exhibit a combination thereof. Interestingly, upon post-removal testing, the sensor will regain proper functionality (6-8). This observation suggests that the unpredictable behavior of implanted sensors may be driven by the tissue-sensor interaction and not by failures in the sensor itself.

Implanted glucose sensors are subject to a dramatically varying tissue microenvironment over the 5-7 days that they are approved for patient use. Upon implantation, the sensor is presented with hemostasis followed by immune cell recruitment and inflammation, and finally the tissue gives way to a repair/remodeling stage comprised of provisional matrix formation, fibrosis, and loss of vasculature. Several excellent reviews are available on this topic (7, 9). Adequately surviving this sequela of events, often referred to as the break-in period, has become an important design criterion in the development of implantable glucose sensors.

Initial strategies to extend sensor functionality have focused on the preventing protein adsorption and cell attachment through the incorporation of hydrogel coatings (10, 11). The emerging sentiment is that resistance to biofouling is necessary but not sufficient to ensure proper sensor function. Numerical modeling and in vitro studies have recently shown that increased glucose consumption and enzymatic attack by immune cells during inflammation may be one of the dominant factors negatively affecting glucose sensor function (12-14).

Currently there exist essentially two schools of thought towards addressing acute inflammation: management and attenuation. Proponents of inflammation management view inflammation as a necessary step to achieve a stable and acceptable tissue bed for an implanted glucose sensor. Approaches that manage acute inflammation are inherently more complex and employ strategies to guide immune cell phenotype and cytokine production (15, 16). Attenuation of inflammation contends that the benefits of minimizing the deleterious effects of acute inflammation on sensor function outweigh the potential advantages of engineering the tissue response. One strategy for the attenuation of acute inflammation involves the local release of anti-inflammatory mediators such as nitric oxide, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and glucocorticoids (17-19).

Recent reports have shown that localized delivery of dexamethasone (Dex) reduces of anomalous sensor effects that arise from inflammatory cell invasion to the surface of an indwelling sensor (20). Dex is a potent glucocorticoid associated with diminished activation of immune cells and up-regulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines (11, 21-24). However, localized delivery of Dex is often accompanied by decreased vascularity at the sensor-tissue interface (25). In previous studies have also demonstrated that highly porous coatings of controlled structure (50-75 μm pore size) could be used to increase vascular perfusion of the tissue bed (26, 27); to our knowledge researchers have yet to explore the combination of these to proven effects as a strategy to improve indwelling glucose sensor function.

Our goal is to incorporate Dex-release as an inflammation attenuation component into a textured coating designed to increase long-term vascular density around implanted sensor leads. Therefore, the current study looked at the possibility of combining proangiogenic texturing with anti-inflammatory Dex release.

Here, we present the fabrication and characterization of Dex-releasing porous polyurethane coatings for needle type glucose sensors. Pore size, porosity, and coating thickness of the porous polyurethane coatings were evaluated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT). Signal strength and response time of sensors deployed with porous coatings was demonstrated using glucose standards. Drug release from porous coatings was monitored over two weeks as a function of initial loading and coating porosity. Bioactivity of the released drug was demonstrated by monitoring Dex-mediated, dose-dependent apoptosis of human peripheral blood derived monocytes in culture. Acute animal studies were used to determine the appropriate Dex payload for the implanted porous coatings. Pilot short-term animal studies showed that Dex released from porous coatings diminished the initial inflammatory response to glucose sensor implantation. These results suggest that deploying sensors with the porous, Dex-releasing coatings is a promising strategy to improve glucose sensor performance.

Methods

Fabrication of Dex-Releasing Porous Coatings

Porous coatings were fabricated by the gas-foaming/salt-leaching technique described previously (27). Briefly, a 6.5 wt % solution of polyurethane was prepared by dissolving Tecoflex® 93A pellets (Lubrizol, Technologies) in a solution of 25:75 ethanol to chloroform ratio. Dex (Sigma, D1756) was dissolved in the polymer solution and stirred until clear. Sieved (50-75μm) ammonium bicarbonate salt particles (MP Biomedicals, 150107) were added to the polymer solution and homogeneously mixed. Table 1 lists the amount of Dex and ammonium bicarbonate porogen added to polyurethane stock solutions to produce various specimen compositions. Dex-free porous and non-porous coatings were fabricated either by respectively not adding Dex or ammonium bicarbonate porogen to the polymer solution.

Table 1.

Porogen and Dex added to stock polymer solution to produce coatings different porosities and Dex loadings

| Intended % Porosity |

Porogen (g) | Intended wt % Dex |

Dex (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 180 |

| 60 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 90 |

| 30 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 45 |

Polymer films were dip-coated onto copper wire mandrels (Belden, 20 AWG) and allowed to dry for 1 h. Films were porated by placing the polymer coated mandrels into DI water for 5 min at 90 °C to allow gas-foaming/salt-leaching to occur. Porated films were then quickly quenched in 4 °C deionized water for 20 min. Films were allowed to dry in over-night in a desiccator, and cut to a length of 1.5 cm in order to fit over the sensing tips of Medtronic MiniMed SOF-SENSOR™ sensors Figure 1A.

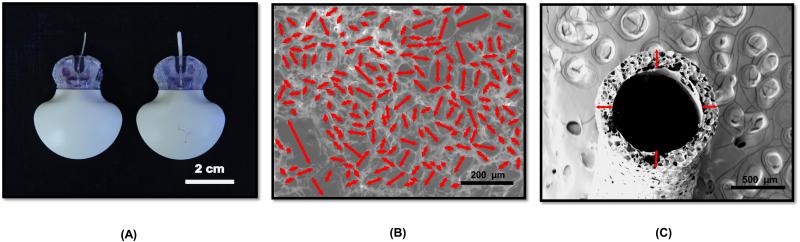

Figure 1.

Pictures and ESEM images of porous coatings created via salt leaching/gas-foaming technique. (A) Picture of Medtronic MiniMed Sof-SensorTM with and without highly porous Dex-releasing coatings. (B) ESEM of exterior surface and (C) cross-section of 90 % Porosity – 2.9 wt % Dex coatings. Arrows indicate pore diameters (B) and coating thickness (C). (n=6)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

A vacuum sputter coater (Denton Desk IV) was used to deposit a 10 nm gold on the surface of the porous coatings. SEM images of the porous coating surfaces and cross-sections were analyzed using ImageJ. A length measurement tool was generated based on the ratio of pixels per scale bar length of each image. Images were standardized to cover a 0.5 mm2 area of the coatings. Using the measurement tool, the major axis of each pore on the selected surface was measured (Fig 1B). Cross-sectional images were used to measure the thickness of the coatings at the positions highlighted (Fig 1C).

Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT)

Porous coatings were soaked in Lugol’s Iodine (EMS Cat.# 26055) for 3 days and were vacuum dried overnight. Samples were evaluated using the Nikon XTH 225 ST Micro-CT scanner. The X-ray source was set to 80 kV and 120 μA, spot size of < 3 μm, and a rotation step of 0.5 °. An exposure time of 708 ms was set for each X-ray image. Four X-ray images were then averaged to obtain one 2D projection. After acquisition, 2D projections were reconstructed using CT Agent software to provide axial picture cross-sections. After reconstruction, the data was converted into 2000 16-bit picture files with a resolution of < 3 μm/pixel. Complete volumes were rendered in Avizo Fire 8.0. Sub-volumes consisting of 500 z-stack images were selected for porosity evaluation. Sample porosity was calculated as the ratio of void to solid volume.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC (PerkinElmer, Diamond DSC N5360020) was employed to determine the physical state of Dex in the polyurethane coatings. Pre-weighed 10 mg samples of Dex-loaded porous coatings were placed into aluminum pans and loaded into the sample chamber. Untreated Dex powder (Sigma, D1756) samples were used as controls. Control samples weighted 0.5 mg to match the amount of Dex in contained in the 10 mg Dex-loaded porous coating samples. The sample chamber was purged with nitrogen to prevent air oxidation of the samples at high temperatures. Samples were kept at 50°C for 10 min during preheating, and then samples were heated a constant rate of 10°C/min until a temperature of 400°C was reached. Degree of Dex crystallinity was determined by measuring Dex’s characteristic endothermic peak at 269°C.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Dex solution concentrations were determined using HPLC (Waters 2690) and a dual absorbance UV detector (Waters 2487). The isocratic mobile phase consisted of 42% acetonitrile and 58% water with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Samples of 50 μl were injected directly and pumped through an Omnisphere 5 C18 Column. Dex was detected using a UV detector at 246 nm. The retention time of dexamethasone was 3.7 min. Dex solution concentration was determined from a standard curve of Dex in PBS from 1 to 100 μg/ml.

Dex Release Studies

Coatings were placed into micro-centrifuge tubes containing 1.5 ml of PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C. Coatings were moved into fresh 1.5 ml PBS solutions every 24 h for a period two weeks. Daily drug release samples were stored at 4°C in the dark until analysis. Samples were thawed at room temperature and injected into the HPLC and the Dex concentration was determined as described above.

To evaluate possible topographical changes due to the depletion of Dex, coatings before and after the two-week release study were imaged by ESEM (wet mode). Captured images were processed as described above to calculate average thickness and pore size.

Dex Loading Efficiency

Pre- and post- gas-foamed coatings, and coatings after drug release studies were completely dissolved in 1 ml chloroform. Solutions were then injected into the HPLC and the Dex concentration was determined as described above.

Sensor Response

Medtronic MiniMed SOF-SENSOR™ glucose sensors, MiniLink™ transmitters, and Transmitter Utility software package were graciously supplied by Medtronic MiniMed (Northridge, CA). Bare sensors were hydrated for 2 h in PBS (37°C, stirred) and then dipped sequentially in 100, 200, 400, and 0 mg/dl glucose in PBS (37°C, stirred) to obtain a calibrated baseline sensor response. Dex-loaded porous coatings were subsequently placed over the sensor tips and subjected to a glucose challenge with 100, 200, 400, and 0 mg/dl of glucose. Dex-free non-porous films served as controls.

Sensor response time, and signal attenuation to glucose challenge were used as metrics to evaluate sensor function. Sensor response times were calculated as the time for the sensor to achieve 90% of its steady state calibration current for a given test interval. Attenuation was calculated as one minus the ratio of the peak sensor current during a given glucose challenge interval divided by the sensor current over the same interval during calibration.

Peripheral Blood Derived Human Monocyte Isolation

Human monocytes were isolated from 100 ml of EDTA-treated blood drawn from healthy volunteers (n=12). Using a hypotonic density centrifugation method, buffy coats were collected from the interphase of Histopaque 1077® (Sigma, 10771). After separation, mononuclear cells were washed twice with complete RPMI 1640 medium. Subsequently, untouched monocytes were negatively selected using magnetic beads (Dynabeads®, Life Technologies). Enriched Monocytes were then incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated AB serum, 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes, 4.5 g/L glucose, and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution. All cultured reagents used had endotoxin levels of < 0.01 ng/ml LPS. The isolated monocyte suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 1×10^6 cells/ml. The viability of the monocytes was > 95% as determined by Calcein AM intracellular stain and purity was > 90% as assessed by CD14+ marker expression using flow cytometric analysis.

Dex-treated Media Preparations for Apoptosis Assays

Two apoptosis studies were conducted to (1) investigate if Dex released from porous coatings retained its bioactivity after gas-foaming/salt-leaching, and (2) to show the dose-dependent effect of Dex released from porous coatings on isolated monocytes.

For Dex bioactivity studies, 90% porous coatings loaded with 1.4 wt % Dex were placed in RPMI for 24 h at 37 °C allowing Dex to be release into the media, the coatings were then moved to a second set of fresh media for another 24 h, and then to a third set of fresh media for another 24 h. This yielded media samples with Dex released from coatings after 24, 48 and 72 h. Dex concentrations from these solutions were determined by HPLC. Equivalent “Dex-spiked media” solutions were made by spiking RPMI media with concentrations equal to that of the Dex released from 90% porous coatings loaded with 1.4 wt% Dex at 24, 48 and 72 h. Untreated media and media treated with Dex-free porous coatings served as controls.

For Dex dose-dependent studies, 90% porous coatings loaded with 0.7, 1.4 and 2.9 wt% Dex were incubated in RPMI media as described above for 24, 48, and 72 h. These solutions were then used to culture isolated monocytes. Untreated media and Dex-free porous coatings served as controls.

Annexin-V Apoptosis Assays

For both Dex apoptosis studies, monocytes were re-suspended to a density of 1×106 cells/ml in treated and untreated media immediately after isolation. Cells were plated in 6-well tissue culture plates. Cell samples from each well were collected every 24 h for a period of 3 days and cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2. During sample collection, cell medium was replaced by suspending monocytes to a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml concentration in new treated or untreated media respectively.

Up-regulation of phosphatidylserine (PS) receptor expression was detected via Annexin-V antibody staining in treated peripheral blood derived human monocytes. For staining, samples were kept in ice washed twice in staining medium (ice cold PBS supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Sodium Azide). Monocytes were directly labeled with APC-mouse mAb to CD14+ (Invitrogen, MHCD1405) and Annexin-V FITC to PS (Invitrogen, A13199). APC and FITC-conjugated murine IgG mAbs of unrelated specificities were used as negative stain controls. Annexin-V positive controls were created by treating U937 cells with camptothecin at a concentration of 4 μg/ml for 4 h. After staining, suspended cells were kept in ice and protected from light until Annexin-V and CD14+ expression was analyzed by flow cytometry analysis.

Animal Studies

Preparation of Implants

Medical Grade Tygon® tubing (formulation S-54-HL Saint-Gobain, Courbevoie, France) was selected for testing of the foreign body response. Tygon® implants were of similar dimensions (1.5 cm long and 0.8 cm outer diameter) and mechanical properties to the tips of Medtronic MiniMed SOF-SENSORTM. Dex-free and Dex-loaded 90% porous coatings were slid onto Tygon® implants. The coatings fitted snugly over the Tygon® tubing and did not need further affixing. Bare and coated implants were ethylene oxide sterilized and allowed to out-gas for at least 7 days prior to implantation. Bare Tygon® tubing was used as a positive control because Tygon® is a silicone known to undergo fibrous encapsulation when subcutaneously implanted (28).

Implantation Procedure

All National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publication no. 85-23 Rev. 1985) were observed. Approval for these studies was granted by the Institutional University Animal Care and Use Committee at Duke University prior to initiation of these studies. Sprague-Dawley rats (200-300 g; CD-type, Charles River Labs, Raleigh, NC) were shaved and prep prior to surgery. After anesthesia induction with 3% isoflurane in oxygen, the dorsal areas were shaved and the skin prepped with chlorhexidine and alcohol three times. The rats were placed in the prone position and a sterile field was created over the dorsum. All implants were inserted via a trocar introducer. A sterile 12-gauge needle was used to access the subcutaneous plane; implants were inserted into the needle and advanced into the rat subcutis using a plunger. The needle and plunger were simultaneously drawn back while the implant stayed in the desired site. The minimal cutaneous wound did not require primary closure.

Dex Systemic Effects

A pilot study was conducted in order to assess the systemic in vivo effects of coated implants loaded with Dex. Porous coatings that were Dex-free or contained 0.7, 1.4, and 2.9 wt% Dex were implanted in the dorsal subcutis of rats (n = 2 for each treatment). Uncoated Tygon® tubing was also implanted. All samples were explanted 14 days post-implantation. Systemic Dex effects were monitored by noting the rat’s weight and overall-health every 3-days for the duration of the study, and by evaluating the tissue response to uncoated Tygon®.

Pilot Evaluation of Dexamethasone-Releasing Coatings

Samples of 90% porous coatings with 0.7 wt% Dex, which did not exhibit system effects, were implanted in the dorsal subcutis of rats along with Dex-free 90% porous coatings and bare Tygon® controls. Samples were explanted 3 days post-implantation.

Evaluation of Histological Samples

Tissue samples were flash frozen using liquid nitrogen immediately upon explanation and kept at −80 °C. Serial cryosections of 10 μm thickness were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to monitor inflammation. Cell nuclei stained purple while the connective tissue surrounding the implant stained pink.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean (±SEM). Coating pore size, thickness, and porosity results were compared using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD tests for all samples (p < 0.05). Sensor functionality and drug release were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD post-hoc test (p < 0.05). Annexin-V Apoptosis assay results were analyzed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Lilliefors test on apoptosis data confirmed data normality while a Maulchy correction was performed since the data violated Maulchy’s sphericity test (unequal variances). Tukey's HSD was used for post-hoc tests and the threshold for significance was p < 0.05.

Results

Coating Pore Size, Thickness and Porosity

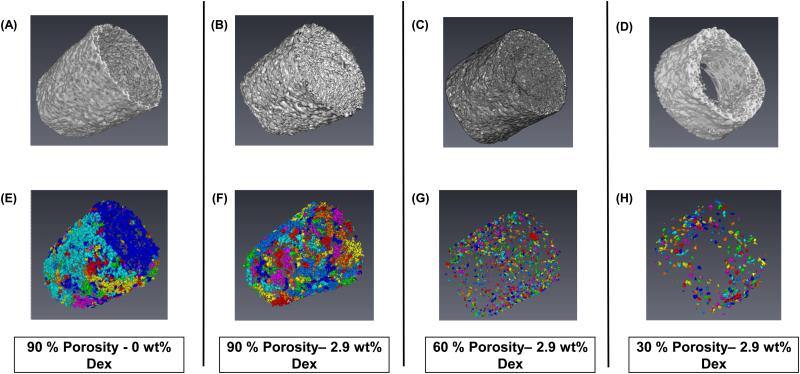

Figure 1A shows a bare glucose sensor (left) and a sensor with a 90% porous coating (right). Coatings fit snugly over the sensor tip and were porous throughout. . Figures 1B and 1C are SEM images showing the porous microstructure and coating cross-section. Figure 2 contains Micro-CT volume renderings of the solid (A-D) and corresponding void (E-H) spaces of a Dex-free 90% porous coating, and Dex-loaded 90%, 60%, and 30% porosity coatings. Total void volume and interconnected void regions represented by individual colors in Figures 2 E-H clearly diminished with decreasing porosity.

Figure 2.

Representative micro-CT images of porous coatings created via salt leaching/gas-foaming technique with decreasing porogen fraction. Coatings of different morphologies were created by varying the ammonium bicarbonate porogen concentrations of (A-B) 90%, (C) 60%, and (D) 30% are shown. Addition of Dex did not disrupt scaffold structure of (A) 0 wt % Dex and (B-D) 2.9 wt %. Corresponding 3D volume renderings of porous structures are also shown, individual colors represent interconnected void regions of coatings (E-H). (n=6)

Table 2 lists the average coating thickness and pore size measured by SEM and the coating percent porosity calculated by Micro-CT for specimens that were intended to generate porosities of 90%, 60% and 30%. A Dex-free 90% porosity specimen was included for comparison. Coating thickness increased significantly with decreasing porogen content, but no statistical difference in average pore diameter was found across these specimen types. The average percent porosity measured by Micro-CT closely mirrored the intended specimen porosities of 90%, 60% and 30%. The inclusion of Dex at the highest 2.9 wt% loading did not significantly affect pore structure, porosity, or coating thickness when compared to porous Dex-free coatings.

Table 2.

Physical Characteristics of Porous Dex-releasing Coatings (n=6)

| Intended Composition | Thickness (μm) | Pore Diameter (μm) |

Measured Porosity (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity % | Dex (%wt) | |||

| 90 | 0 | 85.3 ± 7.5 | 75.8 ± 10.1 | 86.2 ± 2.6 |

| 90 | 2.9 | 80.6 ± 8.3 | 70.4± 13.5 | 85.4 ± 4.1 |

| 60 | 2.9 | 130.5 ± 9.3* | 76.8 ± 12.3 | 55.7 ± 9.8* |

| 30 | 2.9 | 205.9 ± 17.9*# | 72.8 ± 14.9 | 38.4 ± 3.7* |

denotes p<0.05 or less compared to 90 % Porosity – 2.9 wt% Dex Coatings

denotes p<0.05 or less compared to 60 % Porosity – 2.9 wt% Dex Coatings

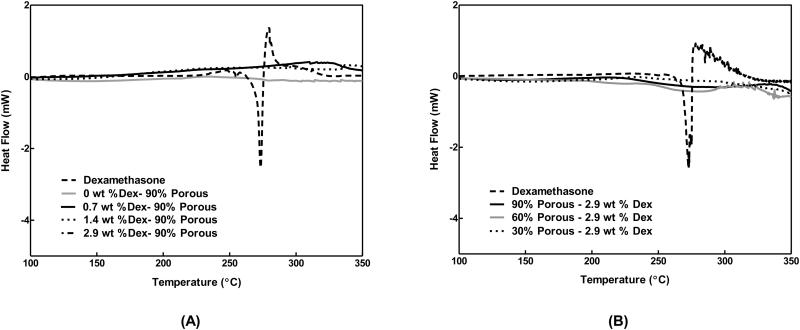

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

DSC was employed to determine whether Dex loaded into coatings was present in a molecularly dissolved state or was sequestered as crystals. The dashed lines in Figures 3A and 3B show the characteristic exothermic melting of bulk Dex crystals (dashed lines) at 269°C. This peak was absent in all Dex-loaded polymer coatings (solid and dotted lines). These results suggest that Dex was highly soluble in the polyurethane matrix and was not sequestered in a crystallized form.

Figure 3.

Differential Scanning Thermographs of dexamethasone loaded porous coatings. Dex is found in an amorphous state within the scaffolds. (A) Initial loading amounts of Dex were increased from 0.7-2.9 wt % Dex. Dex is found in a similar crystal states in scaffolds with high (2.9 wt %) and low (0.7 wt %) initial loading amounts. Actual loading amounts are listed in Table 3. (B) Changes in coating porosity did not affect crystal state of Dex within scaffolds. (n=6)

Dex Loading and Retention after Gas-Foaming

Table 3 lists the Dex loading before (intended) and after the salt-leaching/gas-foaming step (retained) for the coating formulations used in Dex release studies. The wt% Dex retained after gas-foaming correlated directly to the initial Dex loading, while the percent Dex retained after the gas-foaming/salt-leaching step for all groups averaged 79.7± 2.5% (Mean ± SEM).

Table 3.

Loading efficiency and release summary of Dex incorporated into porous polyurethane coatings by salt-leaching/gas-foaming method. (n=10)

| Intended Sample Composition |

Dex retained after foaming |

Average Release Rate (μg/day) | Dex retained after 14 day release (%wt) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity % |

Dex (%wt) | %wt | μg | First Week Release (1-7 days) |

Second Week Release (8-15 days) |

%wt | μg |

| 90 | 0.7 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 305.1 ± 35.3 | 27.4 ± 2.9 | 7.2 ± 1.4 | 0.09± 0.07 | 48.2 ± 37.5 |

| 90 | 1.4 | 1.07 ± 0.09* | 554.5 ± 46.2* | 55.7 ± 5.9* | 11.2 ± 2.3 | 0.17± 0.08* | 87.4 ± 41.1* |

| 90 | 2.9 | 2.10 ± 0.38*# | 914.3 ± 162.9*# | 93.9 ± 13.0*# | 15.4 ± 6.1 | 0.32± 0.08*# | 137.9 ± 34.3*# |

| 60 | 2.9 | 2.41 ± 0.30 | 1195.2 ± 149.4 | 107.8 ± 16.4 | 27.2 ± 2.9 | 0.38± 0.16 | 189.21 ± 79.6 |

| 30 | 2.9 | 2.51 ± 0.32 | 1790.5 ± 229.5 | 142.5 ± 30.5 | 32.5 ± 3.6 | 0.44 ± 0.20 | 315.6 ± 143.4 |

denotes p<0.05 or less compared to 0.7 wt% Dex – 90% Porosity Coatings

denotes p<0.05 or less compared to 1.4 wt% Dex – 90% Porosity Coatings

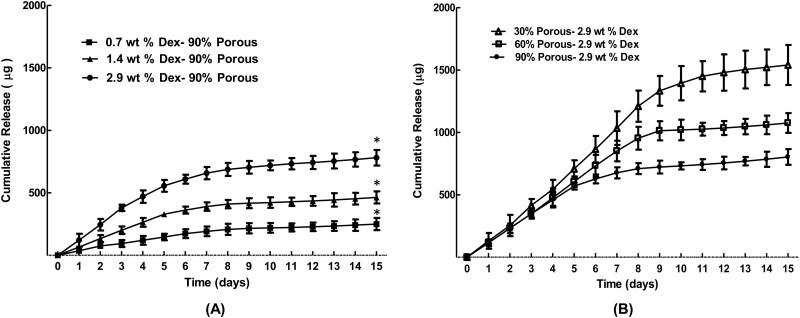

Dex Release

Figure 4 presents the two-week in vitro release profile of Dex from (A) 90% porous coatings prepared with 0.7, 1.4 and 2.9 wt% Dex loadings, and (B) 90%, 60% and 30% porous coatings prepared with 2.9 wt% Dex loadings. Overall, the cumulative Dex release increased significantly with the amount of Dex payload. In each case, a fast release rate was observed in Days 1-7, followed by a slow release rate in Days 8-15 (Table 3). Release rates from days 1-7 increased with increasing Dex payload, either by increasing the wt% Dex for a constant % porosity (Fig 4A), or by decreasing the % porosity for a constant wt% Dex (Fig 4B). Second-week release rates also followed the same trend but the effect was less pronounced and not significant. The last column in Table 3 lists the wt% Dex that remained in the coatings after 14 days of release. The percent retained after 14 days averaged 16.0± 0.9% (Mean ± SEM) over all specimens, again bearing no relationship to percent porosity. Moreover, SEM imaging of 90% porous coatings before and after 14 days of Dex release showed the coating thickness and porosity to be unaltered (data not shown), which one would expect for solubilized small molecule release from a non-degradable polymer.

Figure 4.

Cumulative release of dexamethasone from porous coatings. (A) Initial loading amounts of dexamethasone (0.7,1.4 and 2.9 wt %) and (B) original porogen content (90, 60 and 30% Porosity) were varied. Dexamethasone release from coatings shows high dependency on initial loading. . * denotes p<0.05 or less compared to highlighted treatments (n=10)

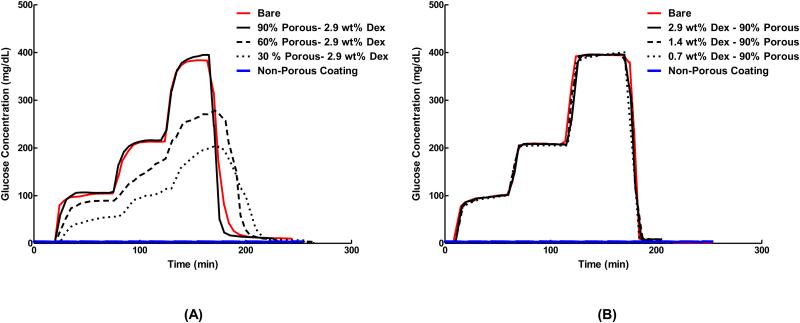

Sensor Response Time and Signal Attenuation

Figures 5A and 5B are the in vitro responses of bare sensors and sensors fitted with porous coatings to step increases glucose concentration. Table 4 lists the corresponding sensor response times and percent signal attenuations. All signals for sensors deployed with 90% coatings were superimposed directly over the bare sensor traces, and exhibited only slight increases in response times and signal attenuation regardless of wt% Dex loading. However, sensors fitted with non-porous coatings, 60% and 30% porosity films showed significantly increased response times and signal attenuation compared to base sensors. Clearly, the 90% porous coatings were best suited for sensor deployment.

Figure 5.

Response of sensors with scaffolds of (A) varying porosities and (B) varying Dex loading concentrations compared to the response of bare sensors (without coatings) and sensors with non-porous coatings. Sensors were subjected to a glucose challenge by exposing them to a series of glucose concentrations in the following order: 0 mg/dL, 100 mg/dL, 200 mg/dL, 400 mg/dL and 0 mg/dL in PBS at 45 min intervals at 37 °C in stirred conditions. Decreasing coatings porosity resulted in increased in sensor response time and attenuation, while changes in Dex-loading did not affect sensor signal when compared to bare sensors. Data presented are representative traces of 6 independent tests. (n=6)

Table 4.

In vitro response of sensors deployed with Dex-releasing polyurethane porous coatings. (n=6)

| Sample Composition | Time (min) to Reach 90% Steady State Current |

% Attenuation 400 → 0a Interval |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity % | Dex (wt%) | 0 → 100a | 100 → 200a | 200 → 400a | 400 → 0a | |

| Bare sensor | 5 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 10 ± 4 | 15 ± 6 | 6.5 ± 1.8 | |

| 90 | 2.9 | 8 ± 3 | 7 ± 3 | 17 ± 3 | 24 ± 7 | 8.6 ± 1.9 |

| 60 | 2.9 | 17 ± 10 | > 45 b*# | >45 b*# | >45 b*# | 24.8 ± 6.9 |

| 30 | 2.9 | >45 b*#& | >45 b*# | >45 b*# | >45 b*# | 49.7 ± 13.4*# |

| Non-Porous Coating | >45 b*#& | >45 b*# | >45 b*# | >45 b*# | 92.5 ± 3.5*# | |

Glucose challenge (mg/dL)

Time exceeded experimental interval

denotes p<0.05 or less compared to Bare Sensor

denotes p<0.05 or less compared to 60% Porosity −2.9 wt% Dex Coatings

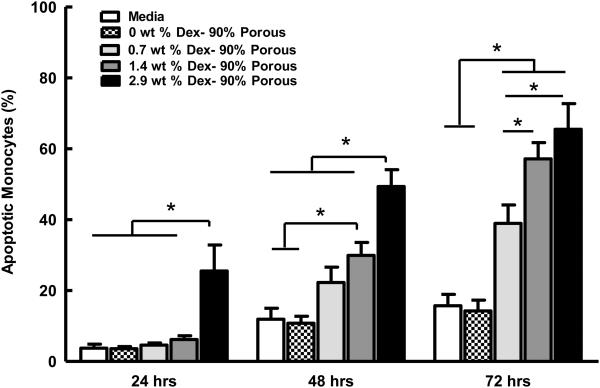

Bioactivity of Dex-Releasing Porous Coatings

Figure 6 displays the percent of Annexin-V positive (i.e. apoptotic) monocytes after being exposed to Dex-releasing 90% porous coatings for 24, 48 and 72 hours. The 2.9 wt% Dex coatings significantly showed the highest percent of Annexin-V positive monocytes at 24, 48 and 72 h, with 25.5%, 49.34% and 65.5% cells being apoptotic, respectively. A significant dose dependence of wt% Dex at 48 and 72 h was observed. Apoptosis of monocytes cultured in media treated with Dex-free porous coatings was similar to the baseline level of apoptosis in untreated media. Finally, identical assays performed with Dex-spiked media exhibited equivalent levels of apoptosis as those using media from Dex released for coatings, showing that gas foaming step had no effect on Dex bioactivity (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Pilot Animal Testing of Dex-Releasing Coatings

After 14 days, rats implanted with 2.9 wt% Dex porous coatings exhibited 16% to 11% weight decrease as well as atrophy and thinning of the dermal tissue; whereas rats implanted with 1.4 wt% Dex porous coatings did not exhibit external signs of adverse Dex effects. However, histological examination of bare positive control implants showed an impaired inflammatory response when compared to controls from rats implanted with Dex-free coatings (data not shown). Rats implanted with 0.7 wt % Dex porous were able to mount an appropriate immune response to positive control implants, and showed no external signs of systemic Dex effects. From this study it was determined that 0.7 wt% Dex porous coatings were the most fitting for further in vivo tests in rats.

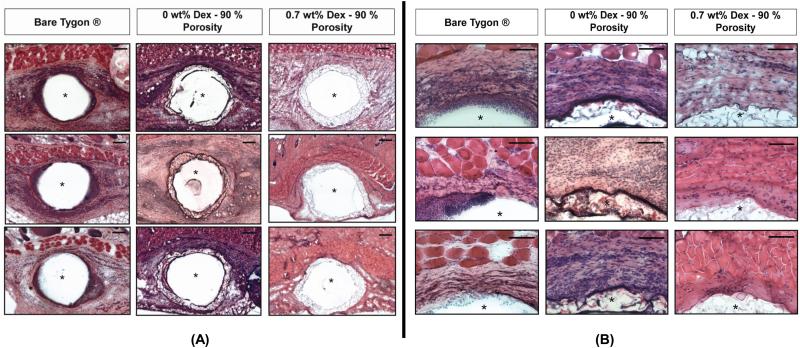

Figure 7 shows low and high magnification of Day 3 H&E stained sections of tissue that surrounded Tygon tubing that was either bare or deployed with 90% porous coatings with either 0.7 wt% Dex or 0 wt% Dex . The Dex loaded coatings showed decreased immune cell infiltration to the implant site when compared to Dex-free porous coatings and the bare controls. Moreover, the acute inflammatory response to Dex-free porous coatings was comparable in magnitude to that of the positive Tygon® controls.

Figure 7.

Anti-inflammatory action of Dex-loaded porous coatings on the wound healing response to glucose sensor implantation over a 3-day period. Implants were inserted in the dorsum of rats and explanted 3 days after. Dex-loaded implants show a decreased inflammatory response when compared to Dex-free implants. (A) Low-magnification H&E photomicrographs at day 3 (Scale bar = 200 μm) (B) Corresponding high-magnification H&E photomicrographs of the top region of the implant at day 3 (Scale bar = 100 μm). (n=3)

Discussion

Tissue-associated anomalies with implanted glucose sensors have been an area of concern for many years. These effects can begin immediately following implantation or can arise during the “break-in period” that occurs during the first few days following sensor insertion. During this time, the sensor is presented with an unstable microenvironment characterized by immune cell infiltration, inflammation, and formation of a granulation tissue. Strategies for improving in vivo sensor performance development of new biomaterials and localized drug delivery for resisting biofouling, attenuating inflammation, and increasing vascularization of the foreign body capsule (17, 25, 26, 29).

Previously, we reported porous polyester coatings deployed at the tips of needle-type glucose sensors that increased vascularization and perfusion of the tissue-sensor interface; however implanted sensors succumbed to inflammation and immune cell infiltration resulting in early and pronounced signal reduction (27). We now employ a segmented polyurethane in order to release the moderately hydrophobic anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid dexamethasone (Dex) from the porous coatings. The present study characterized the physical properties and drug releasing properties of the porous coatings, the bioactivity of the Dex released from porous coatings, and the effect of the deployed porous coatings on sensor performance.

Porous Dex-loaded Tecoflex® 93A coatings had a tunable microstructure. Pore size was controlled by sieving of ammonium bicarbonate particulates to a desired size range of 50-75 μm. Immersing particulate containing polymer coatings in a heated water bath generated pores with sizes in the upper-end of the sieved salt particle size range (Table 2). Micro-CT generated void volume renderings showed a mostly interconnected pore structure that was most pronounced in coatings with high porogen content (Fig 2). Moore et. al. similarly demonstrated that increasing the concentration of leachable sodium chloride particulates in polyester scaffolds for bone tissue engineering resulted increased scaffold void volume and pore interconnectivity (30, 31).

The poration step caused between 13% and 28% of the originally loaded Dex to be lost from the polymer coating (Table 4). The largest Dex loss occurred for the specimens with the highest polymer surface area and wt% Dex payload (90% porosity and 2.9 wt% Dex). Dex loss during poration can be attributed to increased specimen porosity, the steep concentration gradient imposed on the coatings during salt-leaching/gas-foaming fabrication steps, and heat-induced enhanced drug and polymer chain mobility. (32). Differential Scanning Calorimetry showed that there was no evidence of crystallized Dex present in porous coatings (Fig. 3), indicating that Dex was molecularly dissolved within the polyurethane matrix.

Dex-loaded porous coatings exhibited a fast initial release followed by a slower secondary release characteristic of monolithic drug delivery from a polymer matrix (Fig 4). Daily Dex release from coatings over the 15-day release period was within the therapeutic rage for the treatment of localized acute inflammation (Table 3). Interestingly, changes in coating porosity (surface area) did not significantly affect drug release rates. Therefore, the high drug payload of Dex over a short delivery window (2 weeks) cannot be attributed to just simple diffusion of a small molecule drug through a thin and highly porous surface (33, 34). Tecoflex® 93A is a segmented polyurethane comprised of soft micro-domains of poly(tetramethylene oxide) and hard crystalline micro-domains of bis(4-isocyanatocyclohexyl)methane (H12MDI) and 1,4-butanediol. As a non-polar drug, Dex preferential interacts with the amorphous soft micro-domains of the polyurethane; these regions serve as drug reservoirs while empty hard crystalline micro-domains act as channels for drug release (35, 36). Similar results were reported by Gupta et. al. (33), where the small molecule hydrophobic drug, dapivirine, was released from Tecoflex ® rings for vaginal drug delivery applications. This study also showed that Dex release from the rings was fast and did not follow first-order release kinetics.

In vitro sensor responses to glucose challenge studies (Table 4 and Fig 5) showed that sensor response was not hindered by 90% porous coatings. Signal lag and attenuation in low porosity coatings can be attributed to the increased thickness, decreased pore interconnectivity, and reduced total void volume. Functional sensor studies by Koshwanez et.al. (27) similarly showed that sensors deployed with highly porous thick coatings (>200 μm) had elevated response times and diminished signal when compared to bare sensors. This effect was accredited to the augmented migration distance required for glucose to reach the sensor surface. Dex release from coatings also did not interfere with sensor functionality (Fig 5b). Studies by other groups utilizing glucose oxidase based sensors did not show signal fluctuations while functioning within the presence of locally released Dex (11, 37, 38). Based on signal attenuation and lag times, only 90% porous coatings were used for in vitro Dex bioactivity and dose response.

Dex’s anti-inflammatory mechanism has been mostly associated with regulation of cytokine production and reduced metabolic activity of immune cells (24); however, it has recently been highlighted that Dex may also control inflammatory and repair tissue responses by preferentially inducing apoptosis of active inflammatory cells (monocytes, macrophages, T cells), while protecting against apoptotic signals in cells involved in tissue repair (epithelial cells and fibroblast) (21, 39). Consequently the apoptotic monocyte assay reported by Schmidt et. al. (21) was used to show that Dex released from 90% porous coatings had a dose-dependent therapeutic effect on immune cells in culture, and that this effect was retained after the heat processing during the gas-foaming/salt-leaching step.

In the Schmidt assay the Annexin-V protein preferentially binds to the phosphatidylserine (PS) receptor, which is externalized on the surface during early cell apoptosis. Annexin-V binding therefore can be used as a marker for apoptosis detection on individual cells. Dex released from coatings proved to be capable of inducing apoptosis in a time and dose dependent manner (Fig 6). Both increasing the Dex payload of coatings and increasing the exposure time to Dex increased the number of monocytes positive for Annexin-V. Media samples made from Dex-free porous coatings also did not show enhanced Annexin-V uptake highlighting the role of Dex as an apoptotic regulator of peripheral blood derived human monocytes.

Pilot animal studies were performed to determine whether porous coatings with payloads of 0.7, 1.4 and 2.9 wt% Dex would elicit an anti-inflammatory repose in rodents without any apparent system effects. Not surprisingly, highly porous coatings with 0.7 wt% Dex loading were best suited for in vivo deployment since they were able to suppress inflammation locally, while still allowing for adequate immune function at distant sites. This formulation initially delivers ~ 30ug/day of Dex (Table 3) which is within the range of the recommended effective Dex daily dosage (11).

Coatings were further tested in a 3-day pilot study to determine Dex’s effects on the wound healing. Tygon® tubing was chosen for implantation instead of non-functional glucose sensors because hydrogen peroxide builds up in the subcutaneous space adjacent to the glucose oxidase present on non-functional sensors. In fully functional sensors, the applied voltage quickly breaks down the hydrogen peroxide generated by glucose oxidase before it can accumulate. In our study, implant sites with Dex-free porous coatings and bare Tygon® controls showed a strong inflammatory responses with dense fields of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes and macrophages surrounding the implants. In contrast, Dex-loaded coatings showed a noticeably attenuated response with fewer immune cells surrounding the implant. These results demonstrate that Dex released from coatings is not only bioactive but also capable of mediating the immune response to sensor implantation.

Prior studies have shown that local Dex delivery is able to improve sensor performance past the “break-in period” by decreasing leukocyte migration and inflammation at the implant site (19, 22, 23, 25, 38). However, when Dex is delivered over the long-term (>1 month) the drug can act as an angiostatic agent leading to reduced microvessel density, vasodilation, and increased vascular permeability at the implant site.

The textured coatings presented delivered the majority of the Dex payload over the initial week in vitro. This release is suitable to take sensors though the break-in period, while the topographical cues presented by the textured surface are intended to activate endothelial cells to start the neovascularization process. Though we demonstrated the short-term in vivo anti-inflammatory effect of coatings, more exhaustive in vivo testing is necessary fully understand their potential as a platform to extend and improve indwelling sensor functionality.

Findings reported in this study show a system capable of modulating the early stages of FBR to an indwelling implant. Yet, the integration of Dex-releasing porous coatings into a commercially available glucose sensing platforms would face significant regulatory challenges. As a combination product, the system would require rigorous testing before it can reach the diabetic patient population (40). Industrial enterprises have in-turn resorted to the use of novel algorithms and recalibration schemes to extend the in-vivo functionality of continuous glucose sensors (41, 42).

Glucose sensing systems have on occasion reported measurements up-to several months in-vivo (43); however, glucose readings from these studies are still overly numerically and clinically inaccurate to pass regulatory approval and cannot be used as the sole means for programed insulin delivery (44, 45). Therefore, the implementation of biomaterial and drug delivery strategies to extend sensor function should continue to be explored. Approaches such as localized Dex-release and delivery of topographical cues from the sensor surface could drive the generation of a desirable tissue micro-environment that could result in extended in-vivo sensor functionality.

Conclusions

Highly porous Dex-loaded coatings were fabricated by the gas-foaming/salt-leaching technique. Coatings had a controlled pore size and interconnected microstructure. A therapeutic level Dex was loaded into coatings and proved to be in a molecularly dissolved state. Dex release from coatings showed a typical initial fast release followed by a steady release with a high dependency in drug loading over a 15-day period. Porosity did not affect overall Dex release kinetics, however decreasing coating porosity increased sensor signal lag-time and attenuation. Therefore, 90% porous Dex-releasing coatings were determined to be best for bioactivity testing. Dex released from coatings was able to induced apoptosis of human derived peripheral blood monocytes in a time and dose dependent manner. A pilot animal study over a three day period confirmed Dex released from coatings is capable of mediating the acute inflammatory response of the tissue surrounding implants. Future work will focus on further in vivo testing of these coatings, which will allow us to fully assess if the combinatorial strategy of anti-inflammatory drug release and delivery of topographical cues from coatings could encourage tissue in-growth and angiogenesis while reducing the immune response to implanted sensor leads.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grant DK 54932 (WMR). We gratefully acknowledge Medtronic Inc for kind donation of MiniMed SOF-SENSOR™ glucose sensors, MiniLink™ transmitters, Transmitter Utility software package, and for a Medtronic Graduate Fellowship (SVH). The authors would like to thank our Duke Colleagues: Charles S. Wallace for helpful technical discussions, Michelle Gignac, James Thostenson for assistance with SEM and Micro-CT instruments; Jinny Cho and Alina Bocio for assistance with histological stains, and members of the Needham Lab for assistance with DSC. We also thank Patrick Kaiser from the University of Utah, and Lubrizol, Inc. for donation of Tecoflex® polymers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jaremko J, Rorstad O. Advances toward the implantable artificial pancreas for treatment of diabetes. Diabetes care. 1998;21(3):444–50. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klonoff DC. Continuous glucose monitoring roadmap for 21st century diabetes therapy. Diabetes care. 2005;28(5):1231–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le NN, Rose MB, Levinson H, Klitzman B. Interstitial Fluid Physiology as It Relates to Glucose Monitoring Technologies: Implant Healing in Experimental Animal Models of Diabetes. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2011;5(3):605. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mastrototaro JJ. The MiniMed continuous glucose monitoring system. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2000;2(1):13–8. doi: 10.1089/15209150050214078. Supplement 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reach G, Wilson GS. Can continuous glucose monitoring be used for the treatment of diabetes? Analytical chemistry. 1992;64(6):381A–6A. doi: 10.1021/ac00030a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols SP, Koh A, Storm WL, Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH. Biocompatible materials for continuous glucose monitoring devices. Chemical reviews. 2013;113(4):2528–49. doi: 10.1021/cr300387j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisniewski N, Reichert M. Methods for reducing biosensor membrane biofouling. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2000;18(3):197–219. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koschwanez HE, Reichert WM. In vitro, in vivo and post explantation testing of glucose-detecting biosensors: current methods and recommendations. Biomaterials. 2007;28(25):3687–703. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT, editors. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials; Seminars in immunology; Elsevier; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn CA, Connor RE, Heller A. Biocompatible, glucose-permeable hydrogel for in situ coating of implantable biosensors. Biomaterials. 1997;18(24):1665–70. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickey T, Kreutzer D, Burgess D, Moussy F. In vivo evaluation of a dexamethasone/PLGA microsphere system designed to suppress the inflammatory tissue response to implantable medical devices. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2002;61(2):180–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novak MT, Yuan F, Reichert WM. Predicting Glucose Sensor Behavior in Blood Using Transport Modeling: Relative Impacts of Protein Biofouling and Cellular Metabolic Effects. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2013;7(6) doi: 10.1177/193229681300700615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klueh U, Frailey JT, Qiao Y, Antar O, Kreutzer DL. Cell based metabolic barriers to glucose diffusion: Macrophages and continuous glucose monitoring. Biomaterials. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klueh U, Qiao Y, Frailey JT, Kreutzer DL. Impact of macrophage deficiency and depletion on continuous glucose monitoring in vivo. Biomaterials. 2014;35(6):1789–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann T, Howard M, O'garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. The Journal of Immunology. 1991;147(11):3815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown BN, Ratner BD, Goodman SB, Amar S, Badylak SF. Macrophage polarization: an opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2012;33(15):3792–802. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichols SP, Koh A, Brown NL, Rose MB, Sun B, Slomberg DL, Riccio DA, Klitzman B, Schoenfisch MH. The effect of nitric oxide surface flux on the foreign body response to subcutaneous implants. Biomaterials. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corry D, Moran J. Assessment of acrylic bone cement as a local delivery vehicle for the application of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Biomaterials. 1998;19(14):1295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward WK, Hansen JC, Massoud RG, Engle JM, Takeno MM, Hauch KD. Controlled release of dexamethasone from subcutaneously-implanted biosensors in pigs: Localized anti-inflammatory benefit without systemic effects. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2010;94A(1):280–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32651. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klueh U, Kaur M, Montrose DC, Kreutzer DL. Inflammation and glucose sensors: use of dexamethasone to extend glucose sensor function and life span in vivo. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2007;1(4):496–504. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt M, Pauels H-G, Lügering N, Lügering A, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Glucocorticoids induce apoptosis in human monocytes: potential role of IL-1β. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(6):3484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton L, Tegnell E, Toporek S, Reichert W. In vitro characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor and dexamethasone releasing hydrogels for implantable probe coatings. Biomaterials. 2005;26(16):3285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klueh U, Kaur M, Montrose DC, Kreutzer DL. Inflammation and glucose sensors: use of dexamethasone to extend glucose sensor function and life span in vivo. Journal of diabetes science and technology (Online) 2007;1(4):496. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Velden V. Glucocorticoids: mechanisms of action and anti-inflammatory potential in asthma. Mediators of inflammation. 1998;7(4):229–37. doi: 10.1080/09629359890910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton L, Koschwanez H, Wisniewski N, Klitzman B, Reichert W. Vascular endothelial growth factor and dexamethasone release from nonfouling sensor coatings affect the foreign body response. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2007;81(4):858–69. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koschwanez H, Reichert W, Klitzman B. Intravital microscopy evaluation of angiogenesis and its effects on glucose sensor performance. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2010;93(4):1348–57. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koschwanez H, Yap F, Klitzman B, Reichert W. In vitro and in vivo characterization of porous poly - L - lactic acid coatings for subcutaneously implanted glucose sensors. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2008;87(3):792–807. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James SJ, Pogribna M, Miller BJ, Bolon B, Muskhelishvili L. Characterization of cellular response to silicone implants in rats: implications for foreign-body carcinogenesis. Biomaterials. 1997;18(9):667–75. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak MT, Yuan F, Reichert WM. Modeling the relative impact of capsular tissue effects on implanted glucose sensor time lag and signal attenuation. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2010;398(4):1695–705. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4097-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore MJ, Jabbari E, Ritman EL, Lu L, Currier BL, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. Quantitative analysis of interconnectivity of porous biodegradable scaffolds with micro-computed tomography. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2004;71(2):258–67. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otsuki B, Takemoto M, Fujibayashi S, Neo M, Kokubo T, Nakamura T. Pore throat size and connectivity determine bone and tissue ingrowth into porous implants: three-dimensional micro-CT based structural analyses of porous bioactive titanium implants. Biomaterials. 2006;27(35):5892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon JJ, Kim JH, Park TG. Dexamethasone-releasing biodegradable polymer scaffolds fabricated by a gas-foaming/salt-leaching method. Biomaterials. 2003;24(13):2323–9. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta KM, Pearce SM, Poursaid AE, Aliyar HA, Tresco PA, Mitchnik MA, Kiser PF. Polyurethane intravaginal ring for controlled delivery of dapivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor of HIV - 1. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2008;97(10):4228–39. doi: 10.1002/jps.21331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson TJ, Gupta KM, Fabian J, Albright TH, Kiser PF. Segmented polyurethane intravaginal rings for the sustained combined delivery of antiretroviral agents dapivirine and tenofovir. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2010;39(4):203–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yui N, Kataoka K, Sakurai Y, Katono H, Sanui K, Ogata N. Novel Design of Microreservoir-Dispersed Matrices for Drug Delivery Formulations: Drug Release from Polybutadiene- and Poly (ethylene oxide)-Based Segmented Polyurethanes in Relation to Their Microdomain Structures. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 1988;3(2):106–25. doi: 10.1177/088391158800300202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yui N, Kataoka K, Yamada A, Sakurai Y, Sanui K, Ogata N. Drug release from monolithic devices of segmented polyether-poly (urethane-urea) s having both hydrophobic and hydrophilic soft segments. Die Makromolekulare Chemie, Rapid Communications. 1986;7(11):747–50. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ju YM, Yu B, West L, Moussy Y, Moussy F. A novel porous collagen scaffold around an implantable biosensor for improving biocompatibility. II. Long-term in vitro/in vivo sensitivity characteristics of sensors with NDGA-or GA-crosslinked collagen scaffolds. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2010;92(2):650–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ju YM, Yu B, West L, Moussy Y, Moussy F. A dexamethasone-loaded PLGA microspheres/collagen scaffold composite for implantable glucose sensors. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2010;93(1):200–10. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amsterdam A, Tajima K, Sasson R. Cell-specific regulation of apoptosis by glucocorticoids: implication to their anti-inflammatory action. Biochemical pharmacology. 2002;64(5):843–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foote SB, Berlin RJ. Can Regulation Be as Innovative as Science and Technology-The FDA's Regulation of Combination Products. Minn JL Sci & Tech. 2004;6:619. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gough DA, Kumosa LS, Routh TL, Lin JT, Lucisano JY. Function of an implanted tissue glucose sensor for more than 1 year in animals. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2(42):42ra53–42ra53. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia A, Rack-Gomer AL, Bhavaraju NC, Hampapuram H, Kamath A, Peyser T, Facchinetti A, Zecchin C, Sparacino G, Cobelli C. Dexcom G4AP: An Advanced Continuous Glucose Monitor for the Artificial Pancreas. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2012;7(6):1436–45. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilligan BC, Shults M, Rhodes RK, Jacobs PG, Brauker JH, Pintar TJ, Updike SJ. Feasibility of continuous long-term glucose monitoring from a subcutaneous glucose sensor in humans. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2004;6(3):378–86. doi: 10.1089/152091504774198089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke WL, Kovatchev B. Sensors & Algorithms for Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Continuous Glucose Sensors: Continuing Questions about Clinical Accuracy. Journal of diabetes science and technology (Online) 2007;1(5):669. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke WL, Kovatchev B. Continuous glucose sensors: continuing questions about clinical accuracy. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2007;1(5):669–75. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]