Abstract

Background:

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is uncommon; however, accurate diagnosis facilitates personalized management and informs prognosis in probands and relatives.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to highlight that the appropriate use of genetic and nongenetic investigations leads to the correct classification of diabetes etiology.

Case Discussion:

A 30-year-old European female was diagnosed with insulin-treated gestational diabetes. She discontinued insulin after delivery; however, her fasting hyperglycemia persisted. β-Cell antibodies were negative and C-peptide was 0.79 nmol/L. Glucokinase (GCK)-MODY was suspected and confirmed by the identification of a GCK mutation (p.T206M).

Methods:

Systematic clinical and biochemical characterization and GCK mutational analysis were implemented to determine the diabetes etiology in five relatives. Functional characterization of GCK mutations was performed.

Results:

Identification of the p.T206M mutation in the proband's sister confirmed a diagnosis of GCK-MODY. Her daughter was diagnosed at 16 weeks with permanent neonatal diabetes (PNDM). Mutation analysis identified two GCK mutations that were inherited in trans-p. [(R43P);(T206M)], confirming a diagnosis of GCK-PNDM. Both mutations were shown to be kinetically inactivating. The proband's mother, other sister, and daughter all had a clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, confirmed by undetectable C-peptide levels and β-cell antibody positivity. GCK mutations were not detected.

Conclusions:

Two previously misclassified family members were shown to have GCK-MODY, whereas another was shown to have GCK-PNDM. A diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was confirmed in three relatives. This family exemplifies the importance of careful phenotyping and systematic evaluation of relatives after discovering monogenic diabetes in an individual.

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) accounts for approximately 5% of all diabetes cases diagnosed before the age of 45 years (1). It is characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance, young age at onset, absence of β-cell autoimmunity and insulin resistance, and persistent endogenous insulin secretion (2). In the United Kingdom, approximately 80% of cases are misdiagnosed as type 1 (T1D) or type 2 diabetes (3), reflecting limitations in physicians' awareness about MODY and access to genetic testing. Diagnosing MODY has significant implications for patients allowing optimal therapeutic management and informing on prognosis. Relatives also benefit from cascade-screening, which prevents further misdiagnosis. Nevertheless, MODY does not preclude the presence of different diabetes types in other family members.

In this study, using the paradigm of a family with multiple diabetic members, we exemplify how the appropriate use of genetic and nongenetic methods facilitates accurate diabetes classification.

Case discussion

A-30 year-old European woman (II-2, Figure 1) was referred to the Antenatal Diabetes Clinic with diabetes diagnosed in the seventh week of gestation. She was asymptomatic but had mild fasting hyperglycemia with a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7.4% (57 mmol/mol) (Table 1). Pancreatic autoantibodies were negative. She commenced insulin treatment.

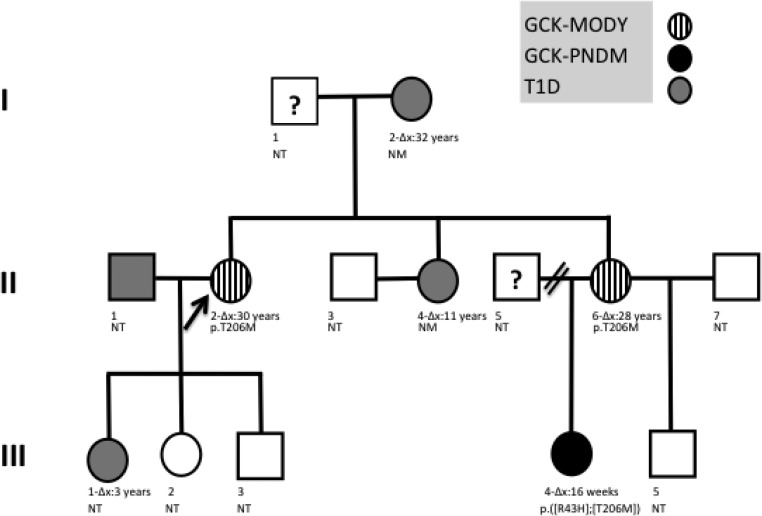

Figure 1.

Family tree illustrating the presence of three different diabetes etiologies across three generations. Δx corresponds to the age of diagnosis of diabetes, NM, no GCK mutations identified in genetic screening; NT, not tested for GCK mutations. p.T206M and p.R43P represent the identified mutations in heterozygotes, and p.([R43P];[T206M]) represents a compound heterozygote with two mutations inherited in trans.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Laboratory Findings of All Diabetic Family Members

| Case Identification (Relationship to II-2) | Age, y | Age at Diagnosis (y, Unless Otherwise Stated) | Symptoms at Diagnosis | Clinical Characteristics | Laboratory Findings | Genetic Testing | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II-2 | 31 | 30 | Asymptomatic- pregnant (7/40) | Slim (BMI: 24 kg/m2) Mild fasting hyperglycemia Insulin free after delivery, not on treatment currently Birth weight: 2.77 kg (42/40) |

HbA1c: 6.1% (43 mmol/mol) FCP: 0.79 nmol/L FBG: 118 mg/dL (110–125, 6.46), (6.6 mmol/L) (6.1–6.9, 0.36) Anti-GAD/ICA: negative |

c.617C>T;p.T206 m in GCK | GCK-MODY |

| I-2 (mother) | 57 | 33 | Osmotic symptoms Hyperglycemia (random BG of 414 mg/dL (23 mmol/L)) |

Slim On insulin soon after diagnosis, currently on basal bolus regimen (0.66 IU/kg · d) Previous episodes of DKA Autoimmune background (POEMS syndrome) CIDP, IHD, HTN |

HbA1c: 8.5% (69.4 mmol/mol) FCP <0.02 nmol/L Anti-GAD: positive |

No mutations in GCK | T1D |

| II-4 (sister) | 30 | 13 | Osmotic symptoms, weight loss, ketonuria | On insulin from diagnosis, currently on basal bolus regimen (1.08 IU/kg · d) Multiple episodes of DKA Diabetic nephropathy |

HbA1c: 9% (74.9 mmol/mol) FCP <0.02 nmol/L Anti-GAD/ICA: negative |

No mutations in GCK | T1D |

| II-6 (sister) | 25 | 20 | Asymptomatic-pregnant | Slim Mild fasting hyperglycemia, not on any medications currently Birth weight: 2.49 kg (40/40) |

c.617C>T;p.T206 m in GCK | GCK-MODY | |

| III-1 (daughter) | 6 | 3 | Enuresis, hyperglycemia, no ketonuria | Slim On basal bolus regimen currently (0.89 IU/kg · d) No DKA admissions Birth weight: 3.4 kg (39/40) |

Postprandial urinary C-peptide to creatinine ratio: 0.006 nmol/mmol Anti-GAD/ICA: positive |

Not tested | T1D |

| III-4 (niece) | 5 | 16 wk | Microsomic at birth, thrush, failure to thrive Ketoacidotic, HDU admission |

Slim On basal bolus regimen currently (0.88 IU/kg · d) DKA at diagnosis Birth weight: 2.1 kg (−4 SD of mean weight for age, 42/40) |

Negative for KCNJ11, ABCC8 and INS mutations p.([c.128C>G; R43P];[c.617C>T; T206M]) in GCK |

GCK-PNDM |

Abbreviations: BG, blood glucose; CIDP, chronic inflammatory polyneuropathy; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FCP, fasting C-peptide; HDU, high-dependency unit; HTN, hypertension; IHD, ischemic heart disease; POEMS, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, skin disease; x/40, week of gestation. FBG represents mean values (range, SD). All sequence information is based on Genbank reference sequence NM_000162.3.

Patient II-2 had a striking family history of diabetes; her mother (I-2) and one sister (II-4) were diagnosed with T1D at ages 32 and 11 years, respectively, and another sister (II-6) had a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). The proband's daughter (III-1) was diagnosed with T1D at age 3 years, and her niece (III-4) had permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus (PNDM) diagnosed at 16 weeks.

After an uncomplicated pregnancy, the proband delivered a healthy boy at 38 weeks and stopped insulin. Mild fasting hyperglycemia persisted after delivery.

The differential diagnosis included T1D, consistent with the young age at onset and family history. However, the absence of symptoms at diagnosis, negative pancreatic autoantibodies, low insulin requirements throughout pregnancy (maximum 0.5 IU/kg · d), and independence from insulin after delivery precluded T1D. The mild antenatal hyperglycemia and discontinuation of insulin after delivery was consistent with GDM, but normal body mass index, European ethnicity, diabetes presentation in early gestation, and persistent fasting hyperglycemia made GDM unlikely (4).

She was subsequently referred to a specialized Diabetes Genetics Clinic for investigation. The phenotype suggested glucokinase (GCK)-MODY; therefore, a sequence analysis of the promoter, exon 1A, exons 2–10, and flanking intronic regions of GCK was performed in a diagnostic genetics laboratory on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer (Life Technologies, Applied Biosciences) and analyzed using Mutation Surveyor version 3.24 (BioGene) (5). She was heterozygous for the previously reported pathogenic c.617C>T; p.T206M mutation in GCK, thus confirming GCK-MODY (6).

Subsequently, we implemented a systematic approach to investigate other diabetic family members and rule out misclassification. Furthermore, we performed functional analyses of the GCK mutations identified.

Materials and Methods

Investigation of other diabetic family members

We identified and reviewed all diabetic members of this family via a systematic approach using a detailed medical history, laboratory tests [fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin, anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) and islet cell antibodies (ICA), C-peptide] and GCK sequencing (http://press.endocrine.org/doi/suppl/10.1210/JC.2013-.3641/suppl_file/JC-13-3641.pdf Supplemental Figure 1). Biochemical tests were performed in a routine laboratory. GAD antibodies were measured by a RIA using the 35S-labeled full-length 65-kDa isoform of GAD, and the results were expressed in World Health Organization units per milliliter per an international standardized curve (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control code 97/550) (7). GCK sequence analysis was performed as above. All participating individuals or their parents gave written consent.

Functional analysis of identified GCK mutations

Glutathione S-transferase-tagged human wild-type and mutant GCK were generated, and GCK activity was measured spectrophotometrically using glucose 6-phosphate-dehydrogenase-coupled assays (8). Glucose affinity was measured in 0–100 mmol/L (WT-GCK) or 0–1000 mmol/L (R43P-GCK, T206M-GCK) of glucose. ATP affinity was determined in 0–5 mmol/L of ATP.

Relative activity indices were normalized and calculated to a blood glucose of 90 mg/dL (5 mmol/L) (9). Predicted glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) thresholds were calculated (10). Predicted pathogenicity for all variants was assessed using PolyPhen version 2.2.2 and Sorting tolerant from Intolerant (11, 12). Variants were mapped onto the crystal structure of human GCK bound to glucose (closed form; Protein DataBank entry 1V4S) using PyMOL version 0.99.

Results

Investigation of other diabetic family members

II-6 was diagnosed with GDM in her second pregnancy and had similar phenotype to the proband. Sequencing analysis identified the GCK p.T206M mutation, confirming GCK-MODY (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Patient II6's daughter (III-4) was microsomic at birth (−4 SD of the predicted mean weight for gestational age), failed to thrive, and was generally unwell until diagnosed with diabetes at 16 weeks after presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) complicated by cerebral edema. She was started on insulin. The diabetes severity was not consistent with GCK-MODY. GCK sequence analysis revealed that III-4 was heterozygous for the p.T206M mutation and also the c.128C>G;p.R43P mutation (13), confirming GCK-PNDM.

The proband's mother (I-2) was diagnosed with diabetes at age 33 years with osmotic symptoms and hyperglycemia. Insulin was initiated soon after diagnosis. An undetectable serum C-peptide (<0.02 nmol/L) and positive anti-GAD antibodies confirmed T1D. No GCK mutations were detected.

Subject II-4 (the proband's other sister) was diagnosed with diabetes at age 13 years with osmotic symptoms, weight loss, and ketonuria. Insulin was commenced at diagnosis. C-peptide was undetectable, confirming T1D. A GCK mutation was not found.

Subject III-1 (the proband's daughter) is the eldest of three children. Their unrelated father (II-1) has coincidental T1D. She was diagnosed with diabetes at age 3 years, after new-onset enuresis. At diagnosis, she was hyperglycemic without ketonuria and was started on insulin. Her postprandial urinary C-peptide to creatinine ratio was 0.006 nmol/mmol, consistent with T1D (14). Given that the presence of a GCK mutation would not alter her current management and her parents did not wish for the investigation, genetic testing was not performed.

Functional characterization of identified mutations

Previous results on the kinetic properties of purified recombinant R43P- and T206M-GCK protein indicated reduced overall function (15, 16); however, to allow direct comparison of the impact of these two mutations on enzyme function, both mutant proteins were reanalyzed simultaneously. Accurate calculation of glucose affinity (S0.5) of R43P-GCK required a glucose concentration range 10 times greater than that for WT-GCK, yielding a glucose S0.5 value 28 times greater than WT-GCK (15). The catalytic activity of R43P-GCK was 0.005% compared with WT-GCK, indicating a severely inactivating mutation (Supplemental Table 1). T206M-GCK was essentially unresponsive to glucose, even at concentrations up to 18 000 mg/dl (1000 mmol/L); it was impossible to calculate the enzymes's S0.5, also indicating a severely inactivating mutation.

Our empirical findings were supported by two in silico function-prediction programs, predicting p.R43P and p.T206M to be functionally deleterious. Moreover, 3-dimensional mapping of residues R43 and T206 on the human GCK crystal structure placed residue R43 within an α-helical structural motif and T206 deep within the glucose-binding pocket of GCK, confirming their importance in the enzyme's structure (Supplemental Figure 2).

To explore the impact of these mutations on fasting plasma glucose levels, we used an established mathematical model and the kinetic characteristics of the mutant enzymes to predict the threshold for GSIS (Supplemental Table 1). Because we were unable to quantify the kinetic defect for p.T206M-GCK, to obtain the minimal threshold for GSIS in a compound heterozygote, we assumed a glucose affinity (S0.5 value) for T206M-GCK at least as poor as R43P-GCK, provided that other enzyme characteristics remained unchanged. Under these assumptions, p.[R43P];[T206M] compound heterozygotes would not be predicted to reach the threshold for insulin release until glucose concentrations were in excess of 3330 mg/dL (185 mmol/L). This compares with a predicted GSIS threshold of 129.6 mg/dL (7.2 mmol/L) for a p.R43P heterozygote.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first family reported with three different diabetes subtypes across three generations (GCK-MODY, GCK-PNDM, T1D) (Figure 1). Using a systematic approach incorporating clinical characteristics, laboratory testing, and GCK sequencing, we reclassified two family members with GCK-MODY (the proband and II-6 previously diagnosed with atypical diabetes and GDM, respectively) and gave a definitive diagnosis to four others; III-4 received a genetic diagnosis of GCK-PNDM, and in I-2, II-4, and III-1, T1D was confirmed. Moreover, we replicated previous functional studies for the identified GCK mutations, demonstrating that both result in severe loss of function.

GCK is the key regulatory enzyme in glucose metabolism, controlling GSIS. Heterozygous inactivating mutations in GCK result in life-long mild, often subclinical, nonprogressive fasting hyperglycemia, by resetting the GSIS threshold to a higher level [99–144 mg/dL (5.5–8 mmol/L)] without affecting the total insulin secretion capacity. In GCK-MODY, patients are generally asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally or as part of diabetes screening (eg, during pregnancy). They do not develop microvascular diabetic complications (17); therefore, treatment is not recommended outside pregnancy. This was explained to subjects II-2 and II-6, and no further follow-up in secondary care was arranged.

Diabetes presenting in the first 6 months of life is not T1D, as evidenced by the absence of pancreatic autoantibodies and the presence of protective human leukocyte antigen haplotypes (18). Neonatal diabetes is a rare condition (1 in 90 000–260 000 births) (19), clinically and genetically heterogeneous, and can be transient or permanent (18). Homozygous or compound heterozygous inactivating mutations in GCK represent a rare cause of PNDM; to date approximately 12 cases have been reported (20), mostly in consanguineous families. These cases present with intrauterine growth retardation and insulin-dependent diabetes from birth (or very soon after).

Subjects II-2 and II-6 undoubtedly inherited the p.T206M mutation from their father, who is not known to have diabetes, but would have fasting hyperglycemia if tested. The p.R43P mutation in III-4 could either have arisen de novo or be of paternal origin. Her father is not known to have hyperglycemia and was unavailable for further evaluation. These unaffected family members should be counseled on the possibility of fasting hyperglycemia being identified upon incidental testing and of the availability of confirmatory genetic testing to avoid mislabeling as type 2 diabetes.

Finally, discussions between physicians, pediatricians, a clinical geneticist, and family members took place regarding the management of the three unaffected children (III-2, III-3, III-5). Their 50% risk of inheriting the p.T206M mutation and having GCK-MODY, and additionally for III-2's and III-3's high risk of developing T1D in the future, given the strong family history, were explained. A possible advantage of genetic testing would be to maximize the available information when assessing hyperglycemia in a hypothetical future scenario, particularly if negative for the GCK mutation. The parents decided to not proceed with either fasting glucose or GCK testing at present in the unaffected children.

In summary, this family highlights the importance of systematically investigating family members of individuals with monogenic diabetes. Monogenic diabetes does not preclude other diabetes subtypes in relatives and vice versa, and definitive genetic status should be established for all affected individuals. Challenges regarding the genetic screening for GCK-MODY in unaffected family members often arise, especially in children, and we suggest that the final decision should involve these individuals or their parents, use genetic counseling expertise if necessary, and should be taken in the context of all potential implications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients for agreeing to participate in this study. F.K.K. is a National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Lecturer. S.E. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator employed by the Exeter National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Facility. A.L.G. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Basic and Biomedical Science.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Research and the Wellcome Trust (Grant 095101/Z/10/Z; to A.L.G.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- DKA

- diabetic ketoacidosis

- GAD

- glutamic acid decarboxylase

- GCK

- glucokinase

- GDM

- gestational diabetes mellitus

- GSIS

- glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- HbA1c

- glycated hemoglobin

- ICA

- islet cell antibodies

- MODY

- maturity-onset diabetes of the young

- PNDM

- permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus

- T1D

- type 1 diabetes.

References

- 1. Thanabalasingham G, Pal A, Selwood MP, et al. Systematic assessment of etiology in adults with a clinical diagnosis of young-onset type 2 diabetes is a successful strategy for identifying maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1206–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kavvoura FK, Owen KR. Maturity onset diabetes of the young: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and management. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2012;10:234–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shields BM, Hicks S, Shepherd MH, Colclough K, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY): how many cases are we missing? Diabetologia. 2010;53:2504–2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berkowitz GS, Lapinski RH, Wein R, Lee D. Race/ethnicity and other risk factors for gestational diabetes. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:965–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellard S, Lango Allen H, De Franco E, et al. Improved genetic testing for monogenic diabetes using targeted next-generation sequencing. Diabetologia. 2013;56(9):1958–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johansen A, Ek J, Mortensen HB, Pedersen O, Hansen T. Half of clinically defined maturity-onset diabetes of the young patients in Denmark do not have mutations in HNF4A, GCK, and TCF1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4607–4614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bingley PJ, Bonifacio E, Williams AJ, Genovese S, Bottazzo GF, Gale EA. Prediction of IDDM in the general population: strategies based on combinations of autoantibody markers. Diabetes. 1997;46:1701–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beer NL, van de Bunt M, Colclough K, et al. Discovery of a novel site regulating glucokinase activity following characterization of a new mutation causing hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in humans. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19118–19126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christesen HB, Jacobsen BB, Odili S, et al. The second activating glucokinase mutation (A456V): implications for glucose homeostasis and diabetes therapy. Diabetes. 2002;51:1240–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gloyn AL, Odili S, Buettger C, et al. Glucokinase and the regulation of blood sugar. In: Matschinsky FM, Magnuson MA, eds. Glucokinase and Glycaemic Disease: From Basics to Novel Therapeutics. Basel: Karger; 2004:92–109 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Osbak KK, Colclough K, Saint-Martin C, et al. Update on mutations in glucokinase (GCK), which cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young, permanent neonatal diabetes, and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1512–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Besser RE, Ludvigsson J, Jones AG, et al. Urine C-peptide creatinine ratio is a noninvasive alternative to the mixed-meal tolerance test in children and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:607–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beer NL, Osbak KK, van de Bunt M, et al. Insights into the pathogenicity of rare missense GCK variants from the identification and functional characterization of compound heterozygous and double mutations inherited in cis. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1482–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galan M, Vincent O, Roncero I, et al. Effects of novel maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)-associated mutations on glucokinase activity and protein stability. Biochem J. 2006;393:389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steele AM, Shields BM, Wensley KJ, Colclough K, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Prevalence of vascular complications among patients with glucokinase mutations and prolonged, mild hyperglycemia. JAMA. 2014;311:279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iafusco D, Stazi MA, Cotichini R, et al. Early Onset Diabetes Study Group of the Italian Society of Paediatric Endocrinology, Diabetology. Permanent diabetes mellitus in the first year of life. Diabetologia. 2002;45:798–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iafusco D, Massa O, Pasquino B, et al. Early Diabetes Study Group of I. Minimal incidence of neonatal/infancy onset diabetes in Italy is 1:90 000 live births. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49:405–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bennett K, James C, Mutair A, Al-Shaikh H, Sinani A, Hussain K. Four novel cases of permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus caused by homozygous mutations in the glucokinase gene. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]