Abstract

Background

Orally anticoagulated patients with insufficient knowledge about their treatment have a higher risk of complications. Standardized patient education could raise their level of knowledge and improve time spent within target INR range.

Methods

This cluster randomized trial included 319 anticoagulated patients drawn from 22 general medical practices. 185 patients received patient education, conducted by practice nurses, consisting of a video, a brochure, and a questionnaire; 134 control patients received only the brochure. The primary endpoint was knowledge about treatment six months after the patient education session. The secondary endpoints were time in the INR (international normalized ratio) target range and complications of anticoagulation.

Results

Patients in the intervention and control groups were of comparable mean age (73 vs. 72 years). They answered a comparable number of questions correctly before the intervention (6.8 ± 0.2 vs. 6.7 ± 0.2) but differed significantly on this measure at six months (9.9 ± 0.2 vs. 7.6 ± 0.2, mean difference 2.3 questions, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–3.1, p<0.001). In the six months prior to the intervention, the INR was in the target range 65 ± 2% vs. 66 ± 3% of the time; in the six months afterward, 71 ± 1% vs. 64 ± 3% of the time (mean difference 7 percentage points, 95% CI –2 to –16 percentage points, p = 0.11). The complication rates were comparable in the two groups (12% vs. 16%, p = 0.30). Patients in the intervention group approved of patient education sessions to a greater extent than control patients (87% vs. 56%).

Conclusion

Patient education was found to be practical, to improve knowledge relating to patient safety in a durable manner, and to meet with the approval of the patients who received it. There was a statistically non-significant trend toward an improvement of the time spent in the INR target range. In view of the major knowledge deficits of orally anticoagulated patients, standardized patient education ought to be made a part of their routine care.

In Germany, about one million persons (roughly 1% of the population) are now being permanently treated with vitamin K antagonists (VKA), most commonly phenprocoumon (1). The main indications for oral anticoagulation are the prevention and treatment of venous thrombosis and arterial embolism in persons with atrial fibrillation, prior deep vein thrombosis, or a mechanical heart valve (2– 5).

VKA use is prone to interactions. Each year, 0.3%–4% of all anticoagulated patients (depending on risk factors) sustain serious complications such as gastrointestinal or cerebral hemorrhage (6– 8). When VKA are given, patients and their physicians must be committed to strict adherence to routinely scheduled checks and safety measures. A lack of patient competence can cause complications, and patient education is considered an essential means of holding these to a minimum (9, 10). The patient education programs that have been developed to date (11– 14) have been found to be successful only when constructed on the basis of self-measurement of international normalized ratio (INR). Yet most anticoagulated patients are elderly, and the majority do not measure their own INR. There is no established mode of patient education for patients in this group.

We developed a standardized type of patient education for orally anticoagulated patients who do not measure their own INR that can be used practically and effectively in the outpatient, primary care setting. The goal of the present trial was to determine whether this type of patient education improved treatment-related knowledge six months later, in comparison to patient education with a brochure alone. The secondary endpoints were the time spent in the INR target range and complications of anticoagulation.

Methods

Patients and setting

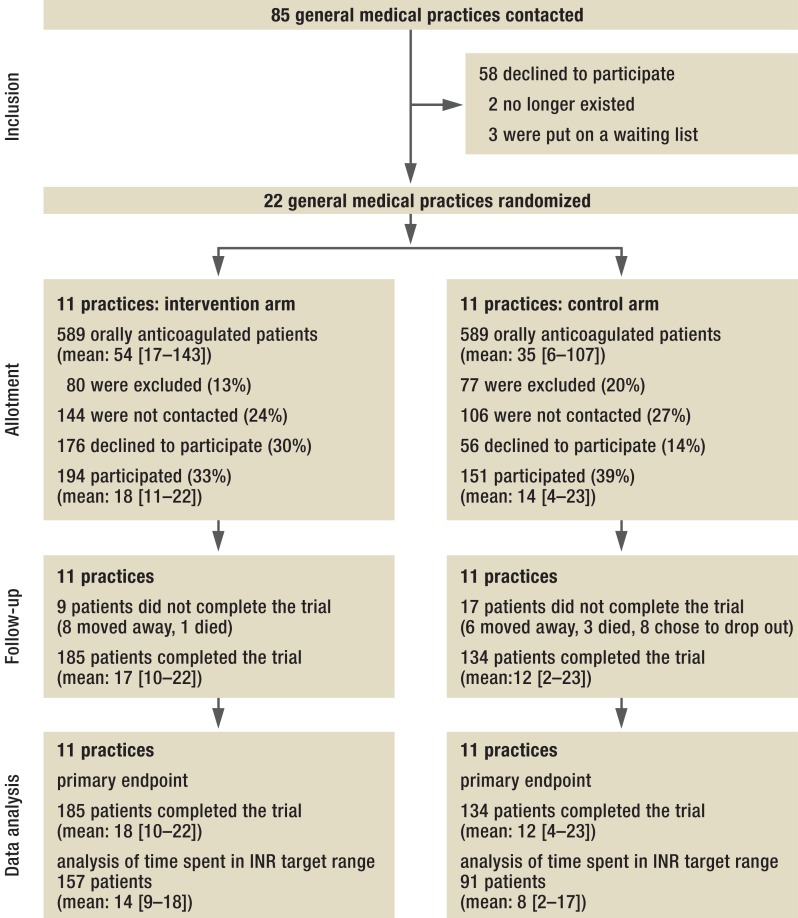

In 2010–11, we conducted an open, cluster randomized, controlled trial on orally anticoagulated patients drawn from a group of general medical practices. The study protocol has been published elsewhere (15). A cluster design was chosen for practical reasons. The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Göttingen, Germany. In early 2011, we wrote to 85 general medical practices in the Göttingen and Braunschweig region; the first 22 practices that agreed to participate were included in the study. With the aid of SAS 9.1, the Institute for Medical Statistics randomized these 22 practices into two equal-sized trial groups (intervention vs. control) by random permutation. It was possible to identify all orally anticoagulated patients in each practice, with the age and sex of each, from computerized records, as the records of all such patients bore the billing code 32015, signifying oral anticoagulation. The inclusion criteria were ability to consent to participation and adequate German language skills; the exclusion criteria were residence in a nursing home and patients in cross coverage. 986 candidates were identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT recruitment flowchart (31);INR, international normalized ratio

Intervention

We developed a standardized patient education session lasting approximately one hour, with information on 13 topics pertaining to oral anticoagulation with phenprocoumon according to the internationally recognized model and recommendations (13) (Table 1). The sessions were conducted by practice nurses and consisted of a 20-minute video presentation followed by a discussion, then an 8-page brochure and a corresponding questionnaire. These materials were first tried out and optimized in a medical practice that did not participate in the trial; they are freely available on the Internet (16, 17). The practice nurses were trained to conduct these patient education sessions. Patients in the control group were only given the brochure.

Table 1. Answers to selected questions on the questionnaire*.

| Block | No. | Question | Control arm | Intervention arm | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start of trial | 6 months later | Start of trial | 6 months later | ||||

| Patient‘s self-asssessment of knowledge | 0.62 | ||||||

| Very good | 11% | 9% | 8% | 6% | |||

| Good | 51% | 73% | 45% | 78% | |||

| Fair | 32% | 16% | 39% | 15% | |||

| Inadequate | 4% | 1% | 7% | 0% | |||

| Individual situation | 1 | Indication for oral anticoagulation known | 87% | 92% | 99% | 99% | 0.06 |

| 2 | Risk lowering | 79% | 85% | 81% | 94% | 0.03 | |

| 3 | Treatment duration known | 69% | 82% | 75% | 94% | 0.01 | |

| 4 | Frequency of checking known | 87% | 89% | 78% | 93% | 0.08 | |

| 5 | INR (or Quick test) target range known | 52% | 71% | 57% | 83% | 0.04 | |

| INR-relatedknowledge | 6 | Foods containing vitamin K | <0.001 | ||||

| Types of cabbage | 69% | 71% | 72% | 94% | |||

| Lettuce | 37% | 49% | 50% | 75% | |||

| Spinach | 48% | 48% | 48% | 72% | |||

| Onions | 8% | 13% | 12% | 48% | |||

| 7 | Dietary recommendation for regular vitamin K intake | 34% | 43% | 30% | 70% | <0.001 | |

| 8 | What to do about forgotten doses | 13% | 16% | 14% | 57% | <0.001 | |

| 9 | Interactions with oral anticoagulation | 0.007 | |||||

| Ginkgo biloba | 4% | 6% | 5% | 17% | |||

| Non-prescription drugs | 22% | 25% | 18% | 38% | |||

| Fasting, weight-loss diets | 16% | 17% | 13% | 28% | |||

| Gastroenteritis | 21% | 24% | 15% | 50% | |||

| Fever | 6% | 14% | 4% | 34% | |||

| Practical knowledge | 10 | Paracetamol is the safest analgesic available without a prescription | 22% | 27% | 19% | 64% | <0.001 |

| 11 | Knowing that insufficient anticoagulation cannot be felt | ||||||

| 12 | Recognition of emergencies and complications | <0.001 | |||||

| Painful bumps under the skin, whether discolored or not | 23% | 34% | 30% | 56% | |||

| Sudden speach impairment | 46% | 52% | 51% | 76% | |||

| Black (tarry) stool | 34% | 54% | 40% | 79% | |||

| Limb weakness | 22% | 35% | 25% | 51% | |||

| 13 | Knowing when it is important to state that one is taking an oral anticoagulant | 0.007 | |||||

| At the dentist‘s | 90% | 87% | 90% | 97% | |||

| At the pharmacy | 26% | 21% | 28% | 52% | |||

| Before getting an injection | 44% | 40% | 43% | 64% | |||

| When a new drug is prescribed | 54% | 52% | 54% | 64% | |||

| Before undergoing any invasive medical procedure | 90% | 88% | 86% | 90% | |||

*The p-values relate to the hypothesis of an effect of the intervention in question in the hierarchical model; the dependent variable for the patients‘ self-assessment of knowledge was a score on the 1-to-4 scale; for other questions, the probability of a correct answer was modeled.

INR, international normalized ratio.

Measuring instruments and trial endpoints

Sociodemographic data, patient‘s knowledge about oral anticoagulation, and their fear of complications were documented upon enrollment in the trial and six months later. The primary endpoint was the patients‘ knowledge as assessed by the questionnaire, which encompassed the 13 topics covered by the patient education session and also included five questions on the patient‘s individual situation (the indication for anticoagulation, the goal and duration of treatment, and the INR target range), four on factors affecting blood coagulation, and four on practical knowledge (warning signs and complication prevention) (Table 1). Each of the 13 topics was weighted equally in the summated score. For questions with multiple answers, a single point was awarded if the number of incorrect answers was less than twice the number of correct answers; otherwise, no points were awarded. For each group of questions, “I don‘t know” was an available response and was scored with 0 points.

The main secondary endpoint of the trial was time spent in the INR target range, as assessed by the method of Rosendaal (18). The 248 patients who were evaluated with respect to this secondary endpoint all had a target range of 2–3 and had undergone at least three INR measurements during a period of continuous phenprocoumon use for at least three months, both in the six months before inclusion in the study and in the six months afterward. Other secondary endpoints were complications that had occurred up to the end of the observation period, self-assessed knowledge, and the patient‘s opinion about the need for patient education.

Power calculation and statistical evaluation

It was calculated that 330 patients from 22 randomized practices would have to be enrolled in the trial and allotted to its intervention arm or control arm to yield an 80% chance of identifying a statistically significant effect of the intervention at a two-tailed significance level of 5%. This power analysis was based on the assumptions of a standardized intervention effect (Cohen‘s D) of 0.41 or more, and an intraclass correlation of 0.05.

For statistical analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints, hierarchical models were developed with random effects for the practices (clusters) and fixed effects for the intervention and baseline characteristics. For binary endpoints, such as individual question groups of the questionnaire, generalized linear models with a logit link function were used. Hierarchical models with random effects were also used for the subgroup analyses. Moreover, a fixed effect of each moderator and his/her interaction with the intervention was incorporated in the model. For the intervention effects, Wald-type 95% confidence intervals [CI] and p-values were determined for the null hypothesis of no difference between groups. The intraclass correlations were expressed as 95% confidence intervals, which were determined by a nonparametric bootstrap procedure with 9999 repetitions. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. All statistical evaluations were performed with SAS Version 9.3.

Results

Of the 979 anticoagulated patients that were identified in the 22 practices, 319 completed the trial: 185 (86 women, 99 men) in the intervention arm and 134 (64 women, 70 men) in the control arm (Figure 1). The average age of the participants was 73 ± 10 years and 72 ± 10 years in the two arms, respectively (mean ± standard deviation). As reported by the patients themselves, the most common indication for phenprocoumon was atrial fibrillation (77% vs. 62%), followed by thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and mechanical heart valves. Previous complications were reported by 8% vs. 11% of patients; fear of thrombosis by 50% vs. 55%; and fear of bleeding by 47% vs. 58% (Table 2). After patient education, the fear of bleeding dropped to 25% in both arms of the trial and the fear of thrombosis to 26% vs. 34%. None of these differences between the two arms of the trial was statistically significant.

Table 2. Sociodemograpnic and clinical baseline characteristics in each arm of the trial.

| Control arm (151 patients) | Intervention arm (194 patients) | Declined to participate (232 patients) | Anticoagulated patientswho were not contacted (250 patients) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sex male female |

64 (42%) 70 (58%) |

86 (44%) 99 (56%) |

102 (44%) 130 (56%) |

118 (47%) 132 (53%) |

| Age (years) | 72±10*1 | 73±10*1 | 74±11*1 | 74±10*1 |

|

Schooling < 10 years = 10 years |

98 (65%) 53 (35%) |

155 (80%) 39 (20%) |

||

|

Indication for anticoagulation, according to the patient*2 atrial fibrillation thrombosis pulmonary embolism heart valve replacement unknown |

94 (62%) 25 (17%) 13 (9%) 18 (15%) 15 (10%) |

149 (77%) (22%) (11%) 17 (9%) 2 (1%) |

||

| History of complications of anticoagulation | 16 (11%) | 15 (8%) | ||

| Fear of thrombosis | 83 (55%) | 97 (50%) | ||

| Fear of bleeding | 88 (58%) | 91 (47%) |

*1 mean ± standard deviation

*2multiple indications possible

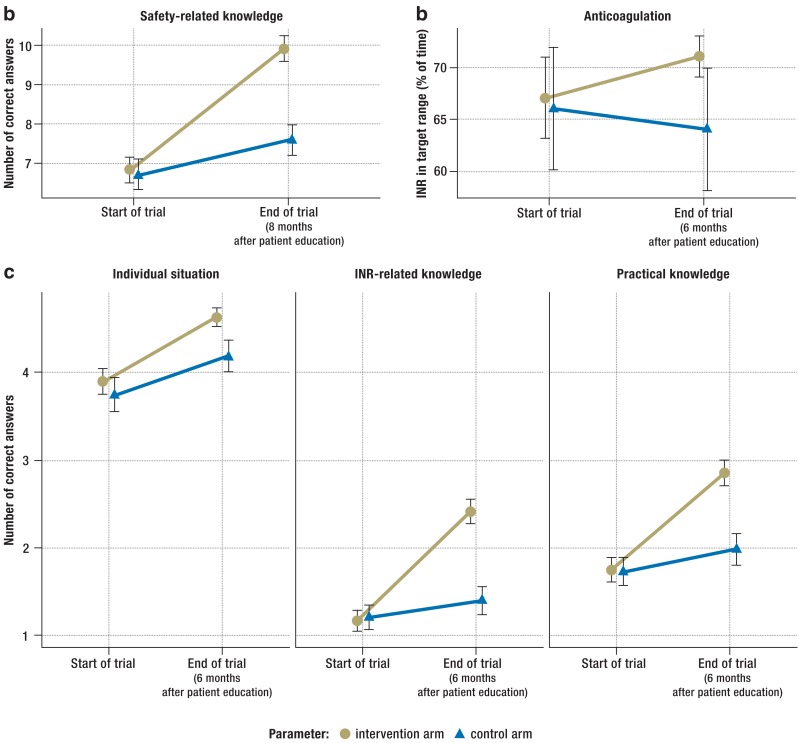

Before patient education, major safety-related knowledge deficits were evident in both groups of trial participants, particularly with respect to interactions, recognition of emergency situations, and dietary restrictions. Six months afterward, the patients in the intervention arm knew significantly more (Table 1, Figure 2a). Before patient education, the patients in the intervention arm and the control arm answered a comparable number of questions and question groups correctly (6.8 ± 0.2 vs. 6.7 ± 0.2 [mean ± standard error]); six months afterward, they differed significantly on this measure (9.9 ± 0.2 vs. 7.6 ± 0.2, mean difference 2.3 questions, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–3.1, p<0.001) (Figure 2c). The intraclass correlation (an index of the similarity of effect among patients in the same practice) was 0.18 (95% CI 0.08–0.28).

Figure 2.

The effect of patient education on knowledge, and, in turn, on anticoagulation

Means and standard errors of the following variables before and after patient education are shown: a) 13-point knowledge score; b) time spent in INR target range; c) partial scores on the patient‘s individual situation (up to 5 points), INR-related knowledge (up to 4 points), and practical knowledge (up to 4 points).

INR, international normalized ratio.

Patients in both groups were asked to assess their own knowledge just before the intervention and six months afterward on a four-point Likert scale (1 = inadequate, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good). Those in the intervention arm registered a larger improvement between the two timepoints (0.38 ± 0.06 vs. 0.20 ± 0.07 points, adjusted mean difference –0.03, 95% CI 0.15–0.09, p = 0.62). Within each arm of the trial, subjective improvement in knowledge was only poorly correlated with the improvement that was objectively measured with the questionnaire (intervention arm: r = 0.10 [p = 0.17], control arm: r = 0.07 [p = 0.44]). Patient education tended to increase the amount of time spent in the INR target range. In the six months prior to the intervention, the INR was in the target range 67 ± 2% vs. 66 ± 3% of the time; in the six months afterward, 72 ± 2% vs. 64 ± 3% of the time (mean ± standard error; mean difference 7.1 percentage points, 95% CI -2 to 16 percentage points, p = 0.11) (Figure 2b). The intraclass correlation was 0.07 (95% CI 0.02–0.17). The complication rates were comparable in the two groups (12% vs. 16%, p = 0.30). More specifically, the rates of hematoma formation, epistaxis, and thrombosis were 7.6%, 5%, and 1.1% in the intervention arm, vs. 10.5%, 4.5%, and 0.0% in the control arm; other complications affected only single patients.

The acceptance of patient education was high. Six months afterward, a higher percentage of patients in the intervention arm than in the control arm said they thought patient education was necessary (87% vs. 56%, p = 0.001). The patients in the intervention arm were particularly appreciative of personal counseling by the practice nurses (84%), and of the informational video (62.7%). Differences between the two arms were highest with respect to approval of video as a format for patient education (63% vs. 13%, p<0.001) and lower with respect to personal counseling (84% vs, 69%, p = 0.002) and the brochure (68% vs. 43%, p = 0.03). Most patients in both arms agreed that the general practitioner‘s office was a better place for patient education than the hospital (96% vs. 82%, p = 0.001).

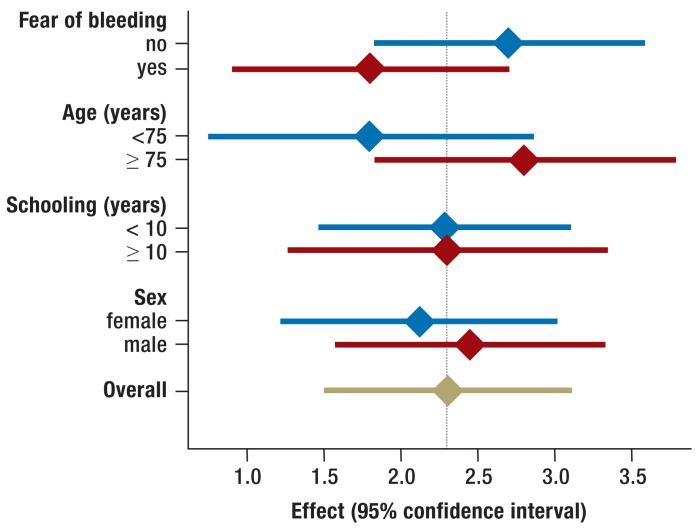

The effect of patient education did not differ significantly between men and women (p = 0.433) or among persons with different levels of schooling (p = 0.88). More information on related topics can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Differences in mean values between intervention armswith respect to the primary endpoint of the study*.

| Subgroup category | Subgroup | Adjusted difference of mean values (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | female | 2.1 (1.2–3) | 0.433 |

| no | 2.45 (1.5–3.4) | ||

| Schooling (years) | <10 | 2.31 (1.5–3.1) | 0.88 |

| ≥ 10 | 2.38 (1.3–3.4) | ||

| Age (years) | ≥ 75 | 2.80 (1.8–3.8) | 0.03 |

| <75 | 1.80 (0.8–2.8) | ||

| Fear of bleeding | yes | 2.75 (1.9–3.6) | 0.03 |

| no | 1.84 (1.2–2.5) |

*Covariate-adjusted difference of mean values and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) for each subgroup. The p-values are for the hypothesis of no interaction

Patients who were more than 75 years old benefited more from the intervention than younger patients did (adjusted difference of mean values for older patients, 2.8, 95% CI 1.8–3.8, vs. 1.8, 95% CI 0.8–2.8 for patients ≤75 years of age, p = 0.03).

An interaction was seen between the fear of bleeding and the effect of the intervention: patients who said they were afraid of bleeding manifested a greater effect of patient education (adjusted difference of mean values 2.75, 95% CI 1.9–3.6) than those who said they were not (1.83, 95% CI 1.2–2.5, p = 0.03). The effects of patient education broken down by subgroup are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Differences of mean values between intervention arms with respect to the primary endpoint, with covariate adjustment, and the related 95% confidence intervals for the various subgroups. The p-values corresponded to the hypothesis that no interaction was present

Discussion

Main findings

These findings document a marked, lasting improvement of safety-related knowledge among patients in general medical practices as a result of patient education that was provided by practice nurses on the basis of a video presentation, a brochure, and a questionnaire. Patient education also tended to prolong the time spent in the INR target range and did not raise the frequency of complications. The participating patients said afterward that they recommended patient education.

The meaning of these findings in the context of the literature

The participants in this trial, as in other trials, knew little about their treatment at the start of the trial (18– 20), even though most had been taking phenprocoumon for years. Patient education markedly improved knowledge in all areas, both in a before-and-after comparison and in a comparison of the two study arms (Table 1, Figure 2). The strongest learning effects were seen in the following areas: nutrition, what to do about forgotten doses, and the fact that in anticoagulated patients, paracetamol (acetaminophen) is the safest analgesic available without a prescription.

The control patients also knew more at the end of the trial than at the beginning, but the difference was markedly smaller. The effects of brochures are generally small and inconsistent; they have been evaluated to date only with respect to knowledge, not outcomes (20, 21). The use of multimedia presentations for patient education has not been adequately studied to date (22). Their main advantage is that they save time when the necessary patient education cannot be provided by practice staff on short notice—as is often the case for patients who are newly anticoagulated on discharge from the hospital. Most trials of patient education that have been carried out till now can be faulted for having no endpoint other than patient knowledge. Clinical endpoints are held to be important as well, along with behavior modification and changes in emotions such as anxiety. Many hospitals provide patient education, but experience shows that patients are less capable of absorbing new information while they are acutely hospitalized.

Patients in the intervention arm tended to spend more time in the INR target range than those in the control arm, but this difference was statistically non-significant. Patients in both arms had better-controlled INR values at the start of this trial than did patients in other trials (11, 23– 26). As a result, there was little room for improvement and, given the low event rate, the trial therefore lacked sufficient power to detect small improvements in this secondary endpoint with statistical significance. The observed 7% improvement in the time spent in the target range lies near the maximum improvement achievable with pharmacogenetic dose adjustment (23– 27). The fact that such a simple measure could bring about so much improvement starting from such a high baseline indicates that patient education ought to be promoted.

Many aspects of the type of patient education that we present here are equally relevant to the new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) that are used when stable anticoagulation cannot be achieved with phenprocoumon (28– 30), e.g., the recognition of warning symptoms or the knowledge of what to do about forgotten doses. An analogous type of patient education would seem appropriate for oral anticoagulation with NOACs as well.

The strengths and weaknesses of this trial

This is the largest trial that has been performed to date on the use of patient education to improve the safety of oral anticoagulation (12). A comparison of the sex and age distributions of the intervention and control groups (and of the patients who were not invited to participate) does not reveal any bias in patient selection. Most patients had already been anticoagulated for years, but the duration of anticoagulation was not recorded. Possible bias may have arisen from participation of more highly motivated and better educated individuals than average, who knew they were being tested. The video-based intervention does not depend on reading ability and thus could be used in routine patient care even for patients who might have declined to participate in the study because there would be a written test.

This trial is the first to measure the durability of improved knowledge six months after the intervention. It was not powered to reveal significant effects on the secondary endpoints, i.e., time spent in the INR target range and complications of anticoagulation. The relatively high intraclass correlation (0.18) for the effect on knowledge reveals a marked dependence of this effect on the particular practice in which patient education is provided. This is most likely attributable to an, as yet, insufficient standardization of the personal discussion with the practice nurse after the video presentation. More intensive training of the practice nurses may be needed to achieve improvement in this area.

Overview

This trial shows that standardized, personal patient education, provided by practice nurses on the basis of a video presentation, a brochure, and a questionnaire, is practically achievable and durably improves orally anticoagulated patients‘ knowledge of the safety-related aspects of their treatment. Even though the observed trend toward a longer time spent in the INR target range was statistically non-significant, the observed major deficit of safety-related knowledge at the start of the trial implies that standardized education for orally anticoagulated patients ought to be introduced in routine practice.

Key Messages.

Patients‘ knowledge is a key factor in the safety of oral anticoagulation.

Patients know little about the safety-related aspects of oral anticoagulation.

Brochures are a relatively ineffective means of patient education.

A video presentation followed by a discussion with a practice nurse led to a durable improvement in patients‘ knowledge.

The patients assessed this type of patient education favorably.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

The authors thank all participating general practitioners, practice nurses, and patients; Brigitta Queisser, who served as a simulated patient; Hannelore Schneider-Rudt, study assistant; as well as Imagofilm, the pharmacy in Hardegsen, PD Dr. med. dent. Dirk Ziebolz (the dentist in the video presentation), and the Tegut supermarket, an der Lutter, Göttingen, Germany.

Sponsoring

This project was funded by the German Ministry of Health (Project number 2509 ATS 005) within in the “National action plan for drug safety in Germany.”

Trial registration

German Clinical Trials Register: DRKS00000586, Universal Trial Number UTN U1111–1118–3464.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

PD Dr. Vormfelde has been an employee of the Novartis company since February 2014.

Dr. Abu Abed, Dr. Hua, Dr. Schneider, and Prof. Chenot state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Schwabe U, Paffrath D. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag; 2012. Arzneiverordnungsreport 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.You JJ, Singer DE, Howard PA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e531S–e575S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e419S–e494S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719–2747. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): the Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:S1–44. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart RG, Tonarelli SB, Pearce LA. Avoiding central nervous system bleeding during antithrombotic therapy: recent data and ideas. Stroke. 2005;36:1588–1593. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170642.39876.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torn M, Bollen WL, van der Meer FJ, van der Wall EE, Rosendaal FR. Risks of oral anticoagulant therapy with increasing age. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1527–1532. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoeb M, Fang MC. Assessing bleeding risk in patients taking anticoagulants. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;35:312–319. doi: 10.1007/s11239-013-0899-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagansky N, Knobler H, Rimon E, Ozer Z, Levy S. Safety of anticoagulation therapy in well-informed older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2044–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.York M, Agarwal A, Ezekowitz M. Physicians‘ attitudes and the use of oral anticoagulants: surveying the present and envisioning future. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2003;16:33–37. doi: 10.1023/B:THRO.0000014590.83591.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawicki PT. A structured teaching and self-management program for patients receiving oral anticoagulation: a randomized controlled trial. Working Group for the Study of Patient Self-Management of Oral Anticoagulation. JAMA. 1999;281:145–150. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong PY, Schulman S, Woodworth S, Holbrook A. Supplemental patient education for patients taking oral anticoagulants: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thrombosis Haemost. 2013;11:491–502. doi: 10.1111/jth.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wofford JL, Wells MD, Singh S. Best strategies for patient education about anticoagulation with warfarin: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siebenhofer A, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Habacher W, Schmidt L, Semlitsch T. Self-management of oral anticoagulation. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:83–91. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hua TD, Vormfelde SV, Abu Abed M, et al. Practice nursed-based, individual and video-assisted patient education in oral anticoagulation— protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chenot JF, Vormfelde SV. Gerinnungshemmer, Phenprocoumon - Was sollte ich darüber wissen? www.youtube.com/watch?v=F0uHbcOnReQ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua TD, Abu Abed M, Vormfelde S, Chenot JF. Schulungsmaterialien. www.allgemeinmedizin.med.uni-goettingen.de/de/content/forschung/105.html. (last accessed on 30. June 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 1993;69:236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jank S, Bertsche T, Herzog W, Haefeli WE. Patient knowledge on oral anticoagulants: results of a questionnaire survey in Germany and comparison with the literature. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46:280–288. doi: 10.5414/cpp46280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winans ARM, Rudd KM, Triller D. Assessing anticoagulation knowledge in patients new to warfarin therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1152–1157. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolson D, Knapp P, Raynor DK, Spoor P. Written information about individual medicines for consumers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002104.pub3. CD002104. doi: 10,1002/14651858.CD002104.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciciriello S, Johnston RV, Osborne RH, Wicks I, deKroo T, Clerehan R, O‘Neill C, Buchbinder R. Multimedia educational interventions for consumers about prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008416.pub2. CD008416. doi: 10,1002/14651858.CD008416.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verhoef TI, Ragia G, de Boer A, et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2304–2312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirmohamed M, Burnside G, Eriksson N, et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2294–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimmel SE, French B, Kasner SE, et al. A pharmacogenetic versus a clinical algorithm for warfarin dosing. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2283–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siebenhofer A, Rakovac I, Kleespies C, Piso B, Didjurgeit U. Self-management of oral anticoagulation in the elderly: rationale, design, baselines and oral anticoagulation control after one year of follow-up. A randomized controlled trial. Thromb Haemostas. 2007;97:408–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furie B. Do pharmacogenetics have a role in the dosing of vitamin K antagonists? N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2345–2346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1313682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft. Leitfaden: Orale Antikoagulation bei nicht valvulärem Vorhofflimmern. www.akdae.de/Arzneimitteltherapie/TE/LF/ (last accessed on 30. June 2014)

- 29.Pfeilschifter W, Luger S, Brunkhorst R, Lindhoff-Last E, Foerch C. The gap between trial data and clinical practice—an analysis of case reports on bleeding complications occurring under dabigatran and rivaroxaban anticoagulation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36:115–119. doi: 10.1159/000352062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallego P, Roldan V, Lip GY. Novel oral anticoagulants in cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:34–44. doi: 10.1177/1074248413501392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG Group C. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]