Abstract

Luminal flow stimulates Na reabsorption along the nephron and activates protein kinase C (PKC) which enhances endogenous superoxide (O2−) production by thick ascending limbs (TALs). Exogenously-added O2− augments TAL Na reabsorption, a process also dependent on PKC. Luminal Na/H exchange (NHE) mediates NaHCO3 reabsorption. However, whether flow-stimulated, endogenously-produced O2− enhances luminal NHE activity and the signaling pathway involved are unclear. We hypothesized that flow-induced production of endogenous O2− stimulates luminal NHE activity via PKC in TALs. Intracellular pH recovery was measured as an indicator of NHE activity in isolated, perfused rat TALs. Increasing luminal flow from 5 to 20 nl/min enhanced total NHE activity from 0.104 ± 0.031 to 0.167 ± 0.036 pH U/min, 81%. The O2− scavenger tempol decreased total NHE activity by 0.066 ± 0.011 pH U/min at 20 nl/min but had no significant effect at 5 nl/min. With the NHE inhibitor EIPA in the bath to block basolateral NHE, tempol reduced flow-enhanced luminal NHE activity by 0.029 ± 0.010 pH U/min, 30%. When experiments were repeated with staurosporine, a nonselective PKC inhibitor, tempol had no effect. Because PKC could mediate both induction of O2− by flow and the effect of O2− on luminal NHE activity, we used hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase to elevate O2−. Hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase increased luminal NHE activity by 0.099 ± 0.020 pH U/min, 137%. Staurosporine and the PKCα/β1-specific inhibitor Gö6976 blunted this effect. We conclude that flow-induced O2− stimulates luminal NHE activity in TALs via PKCα/β1. This accounts for part of flow-stimulated bicarbonate reabsorption by TALs.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, luminal flow, protein kinases, sodium/hydrogen exchange

luminal flow in the nephron is highly variable. Acutely it changes due to glomerular filtration rate (29), tubuloglomerular feedback (17, 28), peristalsis of the renal pelvis (8, 44), and fluid reabsorption (29, 50). Hypertension (4, 6), volume status (3, 42), and diabetes (40) can change luminal flow chronically. Increases in luminal flow enhance Na reabsorption in the proximal tubule (7, 46), thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (39), and cortical collecting duct (10, 43). However, the mechanisms involved are not fully understood.

The thick ascending limb is important in salt, water, and acid/base homeostasis (15, 16, 35). Na is reabsorbed by thick ascending limbs as NaCl and Na bicarbonate via Na-K-2Cl cotransport (35) and Na/H exchange (NHE) (15, 16), respectively. Luminal flow in this segment may be as high as 20 nl/min during conditions of diuresis (4, 30, 42) and may stop due to peristalsis of the renal pelvis (8, 42, 44). The effects of luminal flow on thick ascending limb NHE have not been thoroughly studied.

Superoxide (O2−) is a physiological regulator of renal function (47, 51). Elevated O2− levels can cause salt retention (32, 51), kidney damage (34), and hypertension (33, 34). O2− enhances Na reabsorption in thick ascending limbs. We showed that exogenously-added O2− stimulates net NaCl reabsorption in this segment via a protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent pathway (45) and this is at least partly due to activation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport (25). Exogenously-added O2− also stimulates luminal NHE activity (26), but the signaling cascade involved is unknown.

We (18) and others (1) showed that increases in luminal flow stimulate O2− production in thick ascending limbs and this process is due to activation of PKC (20). However, the effects of luminal flow-enhanced O2− production on thick ascending limb transport have not been thoroughly studied. We showed that the O2− scavenger tempol reduces net NaCl reabsorption by isolated, perfused thick ascending limbs (38). It is likely that stimulation of endogenous O2− production by luminal flow accounts for this effect, but this has not been directly measured. Additionally, the effects of endogenously-produced, flow-stimulated O2− on thick ascending limb NHE activity and the signaling cascades involved have not been studied.

We hypothesized that luminal flow-stimulated O2− production enhances luminal NHE activity via PKC. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of tempol on the recovery rate of intracellular pH (pHi) after an acid load in rat thick ascending limbs perfused at either 5 or 20 nl/min. We then repeated the experiments at 20 nl/min in the absence and presence of PKC inhibitors. Finally, we used an exogenous source of O2− in conjunction with PKC inhibitors to further assess the role of PKC. Our findings indicate that PKCα and/or PKCβ1 mediate(s) stimulation of luminal NHE by endogenous flow-induced O2− production in thick ascending limbs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and solutions.

The pH-sensitive fluorescent dye 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) was obtained from Life Technologies (Eugene, OR). 4-Hydroxy-TEMPO (tempol), hypoxanthine (HX), and xanthine oxidase (XO) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The NHE inhibitor EIPA was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Staurosporine was from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN) and Gö 6976 was from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). The physiological saline used to perfuse and bathe thick ascending limbs contained (in mM) 130 NaCl, 2.5 NaH2PO4, 4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 6 l-alanine, 1 Na3citrate, 5.5 glucose, 2 Ca(lactate)2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 at 37°C. The composition of the basolateral bath used to acid-load cells (acetate solution) was the same, except that 20 mM sodium acetate was added and NaCl was decreased from 130 to 110 mM. The pH calibration solutions contained (in mM) 95 KCl, 5 NaCl, 30 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 2.5 NaH2PO4, 1.5 MgSO4, 5 glucose, 2 CaCl2, and 25 HEPES, and they were titrated to selected pH values between 6.5 and 7.5. Nigericin (Molecular Probes) was prepared as a 10-mM stock in methanol and diluted in calibration solution to a final concentration of 10 μM just before use. All solutions used to perfuse and bathe thick ascending limbs were adjusted to 290 ± 3 mosmol/kgH2O as measured by vapor pressure osmometry.

Animals.

All protocols involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were maintained on a diet containing 0.22% sodium and 1.1% potassium (Purina, Richmond, IN) for at least 5 days.

Isolation and perfusion of thick ascending limbs.

On the day of the experiment, rats weighing 120–150 g were anesthetized intraperitoneally with ketamine and xylazine (100 and 20 mg/kg body wt, respectively). The abdominal cavity was opened and the left kidney was bathed in ice-cold saline and removed. Coronal slices were placed in physiological saline, and medullary thick ascending limbs were dissected from the outer medulla under a stereomicroscope at 4–10°C. Tubules ranging from 0.5 to1.0 mm were transferred to a temperature-regulated chamber (37 ± 1°C) and perfused using concentric glass pipettes as described previously (11). Unless otherwise noted, luminal flow rate was 20 nl/min.

Measurement of pHi.

Isolated thick ascending limbs were loaded with 0.5 μM BCECF-AM in physiological saline for 5 min and then washed in dye-free solution for 20 min. Dye was excited alternately at 488 and 440 nm using a Xenon arc lamp and a Lambda 10–2 filter wheel (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). Emitted fluorescence was collected with a ×40 immersion oil objective mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE300) equipped with a 505-nm dichroic mirror and a 520- to 560-nm barrier filter and digitally imaged with a CoolSnap HQ digital camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Ratiometric data (488 nm/440 nm fluorescence) were recorded with MetaFluor version 6.2r6 imaging software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA) and were converted to pHi values using a three-point nigericin technique for in situ calibration (13).

Measurement of NHE activity.

After the dye-free washing period, measurements were taken once every 6 s for 30 s to establish baseline pHi. Then the basolateral bath was switched to acetate solution to initiate intracellular acidification of thick ascending limb cells while continuing to measure every 6 s. The initial rate of pHi recovery that follows this intracellular acidification was taken as a measurement of NHE activity. After 10 data points beyond the nadir of pHi were recorded, measurements were stopped and the basolateral bath was switched back to physiological saline for a washout period of 5 min. Thick ascending limbs were treated with either tempol (100 μM) or HX (0.5 mM) and XO (1 mU/ml) via the basolateral bath and the acid-loading/measurement procedure was repeated. Recovery rates were calculated from the regression line fit to the first four to six measurements following the minimum pHi as previously described (13) and compared for the two periods. Figure 1 is a representative experiment showing the regression lines used to calculate recovery rates. For experiments in Figs. 3–6, the NHE inhibitor EIPA was added to the basolateral bath so that pHi recovery rate only reflected luminal NHE activity. For experiments in which EIPA (100 μM), staurosporine (10 nM), or Gö 6976 (100 nM) was used, the inhibitors were present in the basolateral bath throughout the experiment.

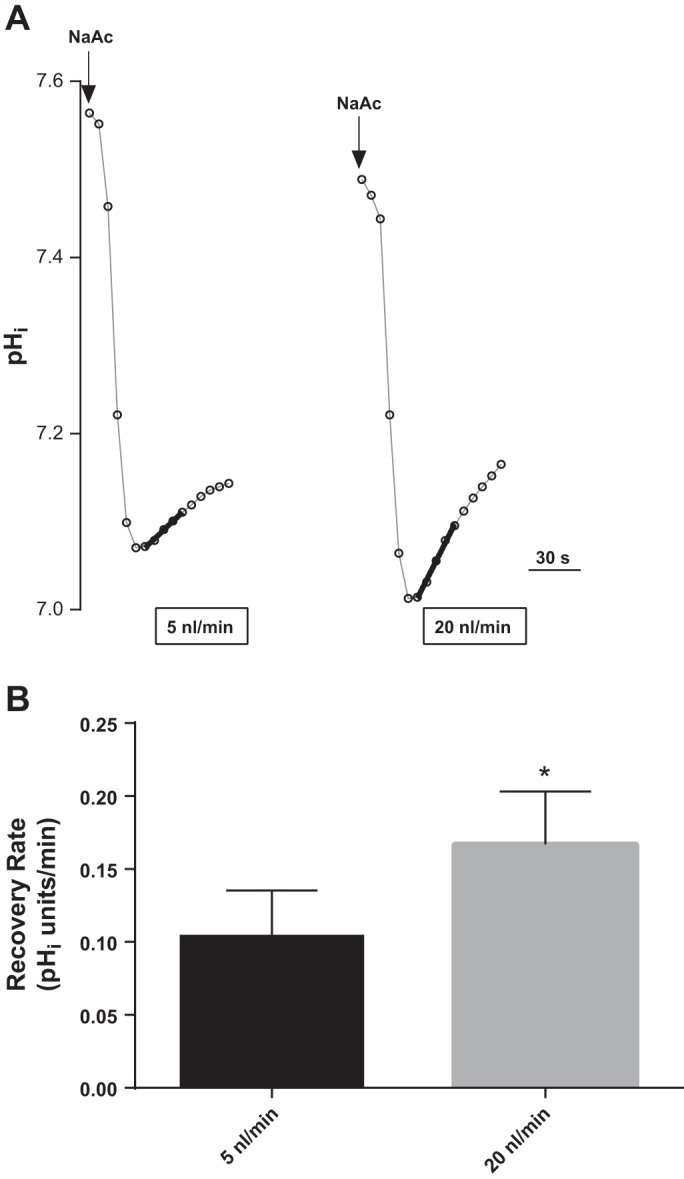

Fig. 1.

Effect of luminal flow rate on basal total Na/H exchange (NHE) activity in thick ascending limbs as measured by intracellular pH (pHi) recovery rate after an acid load with 20 mM sodium acetate (NaAc). A: representative experiment showing fitted regression lines used to calculate pHi recovery rates. B: mean data (*P < 0.02; n = 6).

Fig. 3.

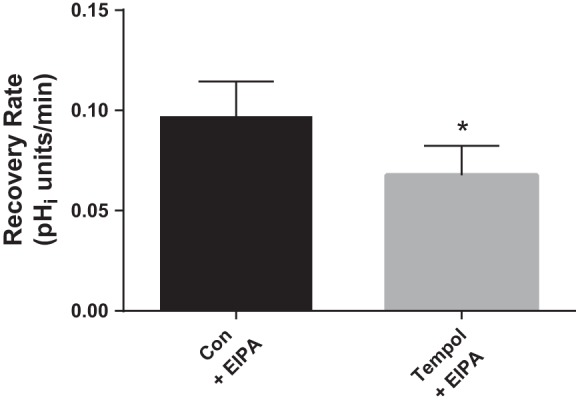

Effect of tempol (100 μM) on luminal Na/H exchange activity as measured by pHi recovery rate after an acid load in flow-stimulated thick ascending limbs. The NHE inhibitor EIPA (100 μM) was present in basolateral bath throughout the experiment. *P < 0.04; n = 6. Luminal flow rate = 20 nl/min.

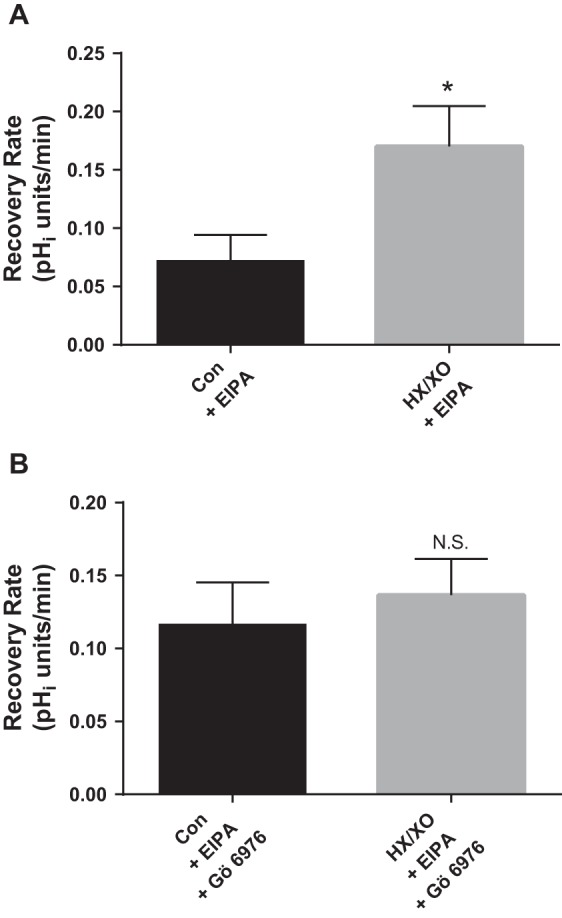

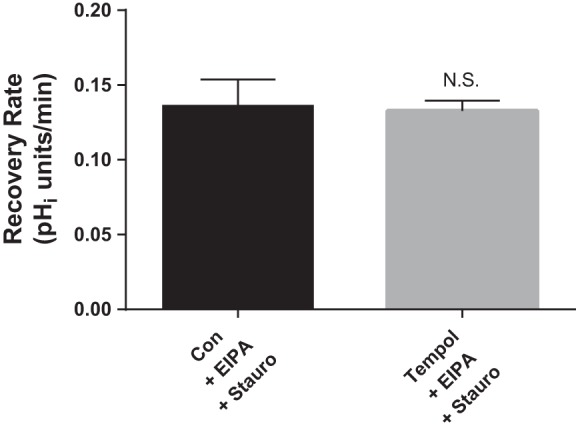

Fig. 6.

Effect of O2− generated from HX (0.5 mM) and XO (1 mU/ml) in the absence and presence of 100 nM Gö 6976, a PKCα- and βI-selective inhibitor, on luminal Na/H exchange activity as measured by pHi recovery rate after an acid load in thick ascending limbs. Gö 6976 and the NHE inhibitor EIPA (100 μM) were present in the basolateral bath throughout the experiment. A: effect of HX/XO. *P < 0.008; n = 5. B: effect of HX/XO in the presence of Gö 6976. n = 5. Luminal flow rate = 20 nl/min.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Data were evaluated using two-tailed Student's t-test for paired experiments with a P < 0.05 criterion for significance.

RESULTS

We first tested whether increases in luminal flow rate had an effect on basal pHi recovery rate (Fig. 1). We measured basal pHi recovery rates of thick ascending limbs perfused at 5 and 20 nl/min. Figure 1A is a representative experiment that shows the fitted regression lines used to calculate pHi recovery rates. Figure 1B represents the means of these experiments. At 5 nl/min, the basal rate of pHi recovery was 0.104 ± 0.031 pHi U/min. When luminal flow was increased to 20 nl/min in the same tubule, the basal pHi recovery rate rose by 81 ± 24% to 0.167 ± 0.036 pHi U/min (P < 0.02; n = 6). These data suggest that increased luminal flow enhances basal NHE activity.

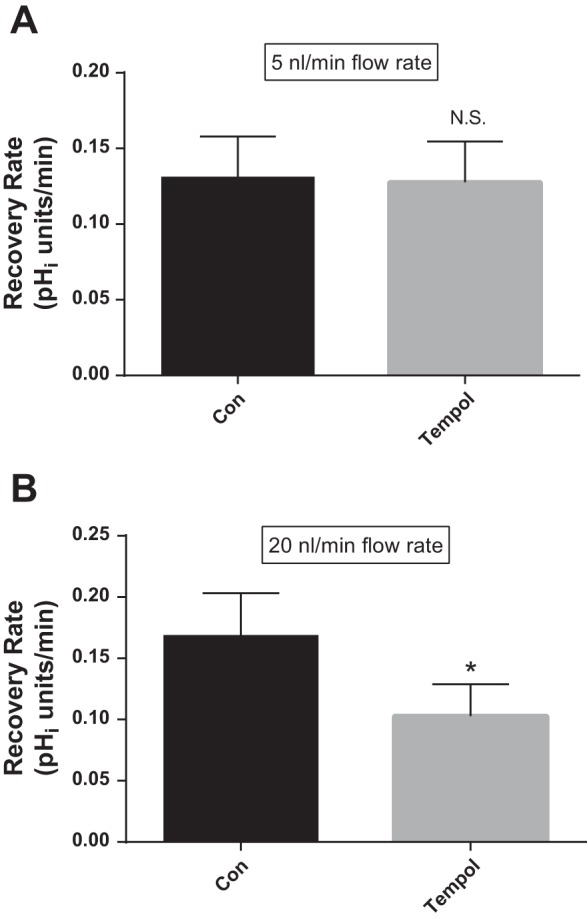

Next, we studied the effect of tempol on total NHE activity in the presence of different luminal flow rates in thick ascending limbs (Fig. 2). When thick ascending limbs were perfused at 5 nl/min, the basal recovery rate of pHi was 0.131 ± 0.027 pHi U/min, while in the presence of the O2− scavenger tempol (100 μM) it was 0.128 ± 0.027 pHi U/min, not significantly different (Δ = −0.003 ± 0.004; n = 5; Fig. 2A). In contrast, when tubules were perfused at 20 nl/min, the basal rate of pHi recovery was 0.168 ± 0.035 pHi U/min, ∼30% greater than at 5 nl/min. Treatment with tempol caused a 39% decrease in pHi recovery rate to 0.103 ± 0.026 pHi U/min (Δ = −0.066 ± 0.013 pHi U/min; P < 0.01; n = 4; Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data suggest that luminal flow stimulates endogenous O2− production which enhances NHE activity.

Fig. 2.

Effect of the superoxide (O2−) scavenger tempol (100 μM) at different flow rates on total Na/H exchange activity as measured by pHi recovery rate after an acid load in thick ascending limbs. Con, control. A: luminal flow rate = 5 nl/min (N.S., nonsignificant; n = 5). B: luminal flow rate = 20 nl/min (*P < 0.01; n = 4).

We previously showed that exogenously-added O2− stimulates luminal NHE activity in thick ascending limbs. Therefore, we next studied whether endogenously-produced O2− that is induced by luminal flow had a similar effect. Figure 3 shows that in the presence of the NHE inhibitor EIPA (100 μM) in the basolateral bath so that pHi recovery only reflects luminal NHE activity, tempol caused a 30% decrease in pHi recovery rate (from 0.097 ± 0.018 to 0.068 ± 0.015 pHi U/min; Δ = −0.029 ± 0.013 pHi U/min; P < 0.04; n = 6) in thick ascending limbs perfused at 20 nl/min. These data indicate that endogenous flow-induced O2− stimulates luminal NHE activity in thick ascending limbs. Control experiments performed with NHE inhibitors in both the bath and lumen blocked pHi recovery, thus confirming that the pHi recovery rate measured in experiments performed with EIPA in only the bath reflected luminal NHE activity.

PKC mediates the effect of O2− in many cell types including thick ascending limb cells. We previously showed that PKC activation is required for the stimulatory effect of O2− on NaCl absorption in thick ascending limbs (45). Therefore, we next studied the role of PKC in mediating the stimulatory effect of flow-induced O2− on luminal NHE activity by testing the effect of tempol with the general PKC inhibitor staurosporine in the basolateral bath (Fig. 4). In the presence of staurosporine (10 nM), the effect of tempol on pHi recovery rate was abolished (0.136 ± 0.018 vs. 0.133 ± 0.007 pHi U/min; Δ = −0.003 ± 0.013 pHi U/min; n = 4). These data may suggest that the stimulatory effect of flow-induced endogenous O2− on NHE activity is PKC-dependent; however, they may also simply indicate that PKC activation is required for flow to stimulate O2− production (20).

Fig. 4.

Effect of tempol (100 μM) in the presence of the general protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor staurosporine (Stauro; 10 nM) on luminal Na/H exchange activity as measured by pHi recovery rate after an acid load in flow-stimulated thick ascending limbs. The NHE inhibitor EIPA (100 μM) was present in the basolateral bath throughout the experiment. n = 4. Luminal flow rate = 20 nl/min.

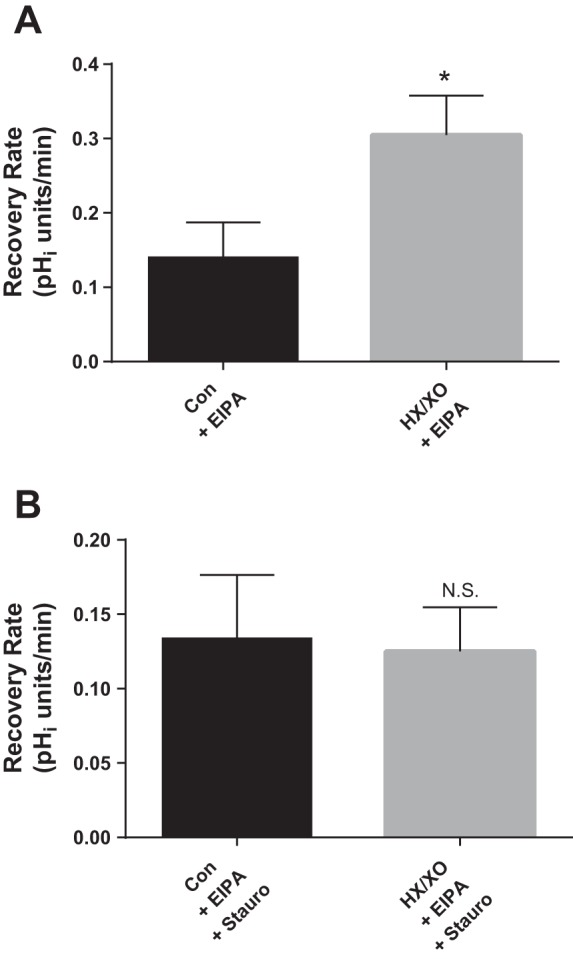

To address this issue, we used HX (0.5 mM) and XO (1 mU/ml) to exogenously generate O2− and examined the role of PKC in the stimulatory effect of O2− on luminal NHE activity (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 5A, HX/XO increased pHi recovery rate in perfused thick ascending limbs by 118% (from 0.140 ± 0.047 to 0.305 ± 0.053 pHi U/min; Δ = 0.165 ± 0.042 pHi U/min; P < 0.02; n = 5). In the presence of staurosporine (Fig. 5B), the effect of HX/XO was completely abolished (0.134 ± 0.043 vs. 0.125 ± 0.030 pHi U/min; Δ = −0.009 ± 0.014 pHi U/min; n = 3). Thus, stimulation of luminal NHE activity by O2− is PKC-dependent.

Fig. 5.

Effect of O2− generated from hypoxanthine (HX; 0.5 mM) and xanthine oxidase (XO; 1 mU/ml) in the absence and presence of the general PKC inhibitor Stauro (10 nM) on luminal Na/H exchange activity as measured by pHi recovery rate after an acid load in thick ascending limbs. Stauro and the NHE inhibitor EIPA (100 μM) were present in the basolateral bath throughout the experiment. A: effect of HX/XO. *P < 0.02; n = 5. B: effect of HX/XO in the presence of Stauro. n = 3. Luminal flow rate = 20 nl/min.

PKC has several isoforms; therefore, we next examined which isoform might mediate the effect of O2− on luminal NHE. Gö 6976 is a selective PKC inhibitor that blocks PKCα and PKCβ1. We tested the ability of this isoform-specific inhibitor to block the effect of HX/XO-generated O2− on luminal NHE activity (Fig. 6). Figure 6A shows that HX/XO increased pHi recovery rate by 137% (from 0.072 ± 0.023 to 0.170 ± 0.035 pHi U/min; Δ = 0.099 ± 0.020 pHi U/min; P < 0.008; n = 5). In contrast, after Gö 6976 (100 nM) treatment, HX/XO enhanced pHi recovery rate by only 17% (0.116 ± 0.029 vs. 0.137 ± 0.025 pHi U/min; Δ = 0.020 ± 0.015 pHi U/min; n = 5; Fig. 6B). These data indicate that virtually all of the stimulatory effect of O2− on luminal NHE activity is mediated by PKCα and/or PKCβI.

Taken together, our data suggest that endogenous, flow-induced O2− stimulates PKCα/β1 to affect NHE activity. However, other factors can affect PKC activity, such as changes in intracellular calcium. Increases in luminal flow can trigger a rise in intracellular calcium in renal cells (23, 48). Therefore, it is possible that flow-related changes in intracellular calcium may be directly activating calcium-dependent PKCα and PKCβ1 and thus directly mediating the stimulatory effect on NHE activity. To address this issue, we tested the effect of increasing luminal flow on total NHE activity in the presence of tempol throughout the experiment to scavenge O2−. We found that basal pHi recovery rate did not change significantly (0.164 ± 0.043 vs. 0.189 ± 0.049 pHi U/min; Δ = 0.025 ± 0.015 pHi U/min; 19 ± 7%; n = 6) when luminal flow rate was increased from 5 to 20 nl/min. These data suggest that flow-induced increases in O2− mediate most, if not all, of the flow-induced stimulation of NHE activity.

DISCUSSION

The role of endogenously-produced O2− in the stimulation of luminal NHE activity by luminal flow and the signaling pathway involved are unclear. We showed that luminal flow enhances endogenously-produced O2− which stimulates luminal NHE activity in thick ascending limbs. This is the first study to show that flow-induced O2− stimulates luminal NHE activity. Our data also suggest that this process is mediated by PKCα and/or PKCβI. In addition, we saw that exogenously-added O2− also enhances luminal NHE activity via a PKCα/βI-dependent mechanism.

Our findings are consistent with reports that enhanced luminal flow stimulates Na reabsorption in the nephron. In mouse proximal tubules, increases in luminal flow stimulate bicarbonate reabsorption due to changes in both NHE and H-ATPase activity (7). In rabbit cortical collecting ducts, luminal flow enhances net Na absorption (10, 43) via regulation of apical epithelial Na channels (43). Increases in luminal flow also enhance Na and Cl transport in avian thick ascending limbs (39).

The sodium reabsorption brought about by luminal NHE activity causes reabsorption of bicarbonate (15, 16). Although not directly tested, our data along with our earlier findings (26) suggest that O2− also stimulates bicarbonate reabsorption via increased luminal NHE activity. This in conjunction with our data on O2−-induced stimulation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport may account for the Na-retaining effects of renal O2−.

Our current findings support our earlier studies on the effect of O2− on ion transporters in thick ascending limbs. We previously demonstrated that exogenously-added O2− stimulates luminal NHE (26). Thus, endogenous and exogenous O2− affect luminal NHE in a similar fashion. Additionally, our data are compatible with our earlier reports in which we demonstrated that endogenous and exogenous O2− increase sodium and chloride absorption primarily through enhanced Na-K-2Cl cotransport (25, 38).

Our current data are consistent with our previous findings that increases in luminal flow stimulate O2− production in thick ascending limbs (12, 18–20). We used flow rates that fall within the physiological range of 0 to 20 nl/min in the thick ascending limb (8, 30, 42, 44). We previously characterized the relationship between flow rate and O2− production using rates covering this range (19). We found that O2− production increases linearly with flow at rates 5 nl/min and above. However, O2− production at 5 nl/min was no different from basal “no flow” (0 nl/min) conditions. It was unclear whether 5 nl/ml represented an actual point at which there was no distinguishable increase in O2− production in response to flow or instead was due to limitations in the method used to measure O2− production. Taking into consideration the data in the present study (Fig. 2), it appears that the triggering point for O2− production may be slightly higher than the 5-nl/min threshold we previously estimated.

Our data are also consistent with reports in other cell types that PKC mediates the effects of O2−. In mesangial cells, O2− activates PKC in response to high glucose (22). O2− causes vasoconstriction via activation of PKC in the vasculature (24). In endothelial cells, O2−-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB is PKC-dependent (37). In addition, many effects of O2− are mediated by PKC in the central nervous system (21, 27).

Additionally, our finding that PKC is involved in the effect of O2− on luminal NHE is consistent with reports that PKC affects many different transporters in thick ascending limbs, and in some cases that PKCα is the isoform involved. We showed that PKCα mediates the stimulatory effect of O2− on NaCl reabsorption (45). PKC is required for angiotensin II-stimulated Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity (2) and indirectly stimulates Na bicarbonate absorption (14). In addition, a PKC-dependent pathway mediates inhibition of apical K+ channel activity caused by high concentrations of prostaglandin E2 (31).

Our data provide strong evidence that flow-induced increases in endogenous O2− mediate the stimulatory effect on NHE activity and that it is PKCα/β1-dependent. Although increased flow can cause a rise in intracellular calcium in renal tubules (23, 48) and thereby directly activate calcium-dependent PKC and stimulate NHE in the absence of O2−, we found that this was not the case. Enhanced O2− resulting from increased flow was necessary for the PKC-dependent stimulatory effect on NHE activity.

Changes in luminal flow are the result of variations in glomerular filtration rate (29, 49), tubuloglomerular feedback (17), and fluid absorption along the nephron (29, 50). Mechanical constriction of the renal pelvis can halt and even reverse flow (8, 44). The significance of variations in luminal flow is evident in conditions in which luminal flow is acutely or chronically enhanced, such as high-salt diet (9, 36), volume expansion (3, 42), and the osmotic diuresis associated with hypertension (4–6, 41, 50) and diabetes (40).

In summary, we found that flow-induced O2− stimulates luminal NHE via a PKC-dependent mechanism. This may account for part of flow-stimulated bicarbonate reabsorption in this segment. Regulation of thick ascending limb Na and bicarbonate absorption by O2− may play an important role in acid/base disturbances and the pathogenesis of several forms of hypertension and other diseases associated with Na retention.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL70985 to J. L. Garvin.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.J.H. performed experiments; N.J.H. analyzed data; N.J.H. and J.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; N.J.H. prepared figures; N.J.H. drafted manuscript; N.J.H. and J.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; J.L.G. conception and design of research; J.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe M, O'Connor P, Kaldunski M, Liang M, Roman RJ, Cowley AW., Jr Effect of sodium delivery on superoxide and nitric oxide in the medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F350–F357, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amlal H, LeGoff C, Vernimmen C, Soleimani M, Paillard M, Bichara M. ANG II controls Na+-K+(NH4+)-2Cl− cotransport via 20-HETE and PKC in medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C1047–C1056, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arendshorst WJ, Beierwaltes WH. Renal tubular reabsorption in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 237: F38–F47, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baer PG, Bianchi G, Liliana D. Renal micropuncture study of normotensive and Milan hypertensive rats before and after development of hypertension. Kidney Int 13: 452–466, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou CL, Marsh DJ. Role of proximal convoluted tubule in pressure diuresis in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 251: F283–F289, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiBona GF, Rios LL. Mechanism of exaggerated diuresis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol 235: 409–416, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Z, Yan Q, Duan Y, Weinbaum S, Weinstein AM, Wang T. Axial flow modulates proximal tubule NHE3 and H-ATPase activities by changing microvillus bending moments. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F289–F296, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dwyer TM, Schmidt-Nielsen B. The renal pelvis: machinery that concentrates urine in the papilla. News Physiol Sci 18: 1–6, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellison DH, Velazquez H, Wright FS. Adaptation of the distal convoluted tubule of the rat. Structural and functional effects of dietary salt intake and chronic diuretic infusion. J Clin Invest 83: 113–126, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores D, Liu Y, Liu W, Satlin LM, Rohatgi R. Flow-induced prostaglandin E2 release regulates Na and K transport in the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F632–F638, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvin JL, Burg MB, Knepper MA. Active NH4+ absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F57–F65, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garvin JL, Hong NJ. Cellular stretch increases superoxide production in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 51: 488–493, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garvin JL, Hong NJ. Nitric oxide inhibits sodium/hydrogen exchange activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F377–F382, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Good DW. PGE2 reverses AVP inhibition of HCO3− absorption in rat MTAL by activation of protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F978–F985, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Good DW. Sodium-dependent bicarbonate absorption by cortical thick ascending limb of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 248: F821–F829, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good DW, Knepper MA, Burg MB. Ammonia and bicarbonate transport by thick ascending limb of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 247: F35–F44, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holstein-Rathlou NH, Marsh DJ. A dynamic model of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 258: F1448–F1459, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Flow increases superoxide production by NADPH oxidase via activation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport and mechanical stress in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F993–F998, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong NJ, Garvin JL. NADPH oxidase 4 mediates flow-induced superoxide production in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1151–F1156, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong NJ, Silva GB, Garvin JL. PKC-α mediates flow-stimulated superoxide production in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F885–F891, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hongpaisan J, Winters CA, Andrews SB. Strong calcium entry activates mitochondrial superoxide generation, upregulating kinase signaling in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 24: 10878–10887, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua H, Munk S, Goldberg H, Fantus IG, Whiteside CI. High glucose-suppressed endothelin-1 Ca2+ signaling via NADPH oxidase and diacylglycerol-sensitive protein kinase C isozymes in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 278: 33951–33962, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen ME, Odgaard E, Christensen MH, Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. Flow-induced [Ca2+]i increase depends on nucleotide release and subsequent purinergic signaling in the intact nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2062–2070, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin N, Packer CS, Rhoades RA. Reactive oxygen-mediated contraction in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle: cellular mechanisms. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 69: 383–388, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juncos R, Garvin JL. Superoxide enhances Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F982–F987, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juncos R, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Differential effects of superoxide on luminal and basolateral Na+/H+ exchange in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R79–R83, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klann E, Roberson ED, Knapp LT, Sweatt JD. A role for superoxide in protein kinase C activation and induction of long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem 273: 4516–4522, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leyssac PP, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Effects of various transport inhibitors on oscillating TGF pressure responses in the rat. Pflügers Arch 407: 285–291, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leyssac PP, Karlsen FM, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Skott O. On determinants of glomerular filtration rate after inhibition of proximal tubular reabsorption. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R1544–R1550, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang M, Berndt TJ, Knox FG. Mechanism underlying diuretic effect of l-NAME at a subpressor dose. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F414–F419, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu HJ, Wei Y, Ferreri NR, Nasjletti A, Wang WH. Vasopressin and PGE2 regulate activity of apical 70 pS K+ channel in thick ascending limb of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C905–C913, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majid DS, Nishiyama A. Nitric oxide blockade enhances renal responses to superoxide dismutase inhibition in dogs. Hypertension 39: 293–297, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makino A, Skelton MM, Zou AP, Roman RJ, Cowley AW., Jr Increased renal medullary oxidative stress produces hypertension. Hypertension 39: 667–672, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manning RD, Jr, Tian N, Meng S. Oxidative stress and antioxidant treatment in hypertension and the associated renal damage. Am J Nephrol 25: 311–317, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molony DA, Reeves WB, Andreoli TE. Na+:K+:2Cl− cotransport and the thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 36: 418–426, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mozaffari MS, Jirakulsomchok S, Shao ZH, Wyss JM. High-NaCl diets increase natriuretic and diuretic responses in salt-resistant but not salt-sensitive SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F890–F897, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogata N, Yamamoto H, Kugiyama K, Yasue H, Miyamoto E. Involvement of protein kinase C in superoxide anion-induced activation of nuclear factor-kappa B in human endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 45: 513–521, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F957–F962, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osono E, Nishimura H. Control of sodium and chloride transport in the thick ascending limb in the avian nephron. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 267: R455–R462, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollock CA, Lawrence JR, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F946–F952, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roman RJ. Pressure-diuresis in volume-expanded rats. Tubular reabsorption in superficial and deep nephrons. Hypertension 12: 177–183, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakai T, Craig DA, Wexler AS, Marsh DJ. Fluid waves in renal tubules. Biophys J 50: 805–813, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satlin LM, Sheng S, Woda CB, Kleyman TR. Epithelial Na+ channels are regulated by flow. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F1010–F1018, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt-Nielsen B. The renal concentrating mechanism in insects and mammals: a new hypothesis involving hydrostatic pressures. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R1087–R1100, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silva GB, Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption in the thick ascending limb via activation of protein kinase C. Hypertension 48: 467–472, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang T. Flow-activated transport events along the nephron. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 530–536, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilcox CS. Reactive oxygen species: roles in blood pressure and kidney function. Curr Hypertens Rep 4: 160–166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woda CB, Leite M, Jr, Rohatgi R, Satlin LM. Effects of luminal flow and nucleotides on [Ca2+]i in rabbit cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F437–F446, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yip KP, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Marsh DJ. Mechanisms of temporal variation in single-nephron blood flow in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F427–F434, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Mircheff AK, Hensley CB, Magyar CE, Warnock DG, Chambrey R, Yip KP, Marsh DJ, Holstein-Rathlou NH, McDonough AA. Rapid redistribution and inhibition of renal sodium transporters during acute pressure natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F1004–F1014, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou AP, Li N, Cowley AW., Jr Production and actions of superoxide in the renal medulla. Hypertension 37: 547–553, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]