Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea causes chronic intermittent hypoxia (IH) and is associated with impaired glucose metabolism, but mechanisms are unknown. Carotid bodies orchestrate physiological responses to hypoxemia by activating the sympathetic nervous system. Therefore, we hypothesized that carotid body denervation would abolish glucose intolerance and insulin resistance induced by chronic IH. Male C57BL/6J mice underwent carotid sinus nerve dissection (CSND) or sham surgery and then were exposed to IH or intermittent air (IA) for 4 or 6 wk. Hypoxia was administered by decreasing a fraction of inspired oxygen from 20.9% to 6.5% once per minute, during the 12-h light phase (9 a.m.–9 p.m.). As expected, denervated mice exhibited blunted hypoxic ventilatory responses. In sham-operated mice, IH increased fasting blood glucose, baseline hepatic glucose output (HGO), and expression of a rate-liming hepatic enzyme of gluconeogenesis phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), whereas the whole body glucose flux during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp was not changed. IH did not affect glucose tolerance after adjustment for fasting hyperglycemia in the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test. CSND prevented IH-induced fasting hyperglycemia and increases in baseline HGO and liver PEPCK expression. CSND trended to augment the insulin-stimulated glucose flux and enhanced liver Akt phosphorylation at both hypoxic and normoxic conditions. IH increased serum epinephrine levels and liver sympathetic innervation, and both increases were abolished by CSND. We conclude that chronic IH induces fasting hyperglycemia increasing baseline HGO via the CSN sympathetic output from carotid body chemoreceptors, but does not significantly impair whole body insulin sensitivity.

Keywords: sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes, hypoxic chemoreflex, hepatic glucose output, gluconeogenesis

obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is recurrent upper airway obstruction during sleep leading to sleep fragmentation and chronic intermittent hypoxia (IH) during sleep (20). OSA leads to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (46, 47, 67, 85, 86), which have been attributed to the metabolic syndrome associated with this disorder (14). A strong independent association between OSA, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes has been demonstrated in multiple reports (1, 9, 17, 48, 55, 66, 68, 84). Clinical studies indicated that the development of insulin resistance is linked to IH of OSA (66, 68).

Acute exposure to sustained hypoxia leads to insulin resistance (54). Studies in healthy human volunteers have shown that acute IH also leads to insulin resistance in the intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) (44). We have previously developed a mouse model of IH, which mimics the oxyhemoglobin desaturation profile of human OSA (69, 70), and have shown that, similar to humans, both acute and chronic murine IH lead to insulin resistance (10, 26). However, mechanisms of insulin resistance in IH remain poorly understood.

Human OSA and IH in rodents activate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (16, 34, 51, 65, 78). Activation of the SNS leads to hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance, increasing hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis (3, 87). In addition, catecholamines induce adipose tissue lipolysis (4). Exuberant lipolysis results in release of free fatty acids (FFA), leading to fatty liver and insulin resistance (6, 52, 81). Activation of the SNS during IH occurs through the augmented hypoxic chemoreflex mediated by the carotid body and blunted baroreflex in the carotid sinus (22, 65). We anticipated that carotid sinus nerve (CSN) dissection (CSND) would attenuate both the hypoxic chemoreflex, which would decrease SNS activity, and the baroreflex, which would increase SNS activity. CSND abolished IH-induced hypertension (38), suggesting that the hypoxic chemoreflex has a dominant effect. We hypothesized that IH leads to insulin resistance via the hypoxic chemoreflex in the carotid body and ensuing activation of efferent sympathetic innervation of the insulin sensitive organs and, therefore, CSND would prevent IH-induced insulin resistance.

METHODS

Animals and overall design.

One hundred thirty four adult male C57BL/6J mice, 6–8 wk of age (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, MA) underwent CSND (n = 60) or sham surgery (n = 64). After a 2-wk recovery animals were exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia (IH) or intermittent air (IA) while fed a regular chow diet. (1) Forty six mice were exposed to IH or IA for 6 wk. In these mice, the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPTGG) was performed after 4 wk of exposure; pulse oximetry was measured after 5 wk of exposure (Table 1). Upon completion of the exposure, mice were bled by retro-orbital puncture and euthanized under 1–2% isoflurane anesthesia after a 5-h fast. All blood draws were performed between 12 p.m. and 1 p.m. (2) Thirty mice were exposed to IH or IA for 6 wk. The left femoral arterial and venous lines were implanted and the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp was performed on week 6 followed by euthanasia. Specifically, we used the following numbers of mice per group in the clamp experiment: Sham-IH, n = 7; CSND-IH, n = 6; sham-IA, n = 9; CSND-IA, n = 8. (3) Forty mice (n = 10 per group) were exposed to IH or IA for 4 wk and then used for baseline or insulin stimulated Akt phosphorylation. (4) Eighteen mice (CSND, n = 9; sham, n = 9) had blood pressure telemeters implanted followed by IH exposure and the baroreflex testing. All mice had free access to food and water and were housed in the standard laboratory environment with the 12:12-h light-dark cycle (9 a.m. to 9 p.m. lights on/9 p.m. to 9 a.m. lights off). The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Use and Care Committee and complied with the American Physiological Society Guidelines for Animal Studies.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of C57BL/6J mice exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) or intermittent air (IA) after carotid sinus nerve dissection (CSND) or sham surgery

| Sham |

CSND |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA | CIH | IA | CIH | |

| n | 14 | 10 | 9 | 13 |

| Age, wk | ||||

| IH or IA | 6–8 | 6–8 | 6–8 | 6–8 |

| Surgery | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Body weight, g | ||||

| Day 0 of IH or IA | 28.8 ± 1.4 | 28.9 ± 2.3 | 28.4 ± 1.7 | 28.9 ± 2.1 |

| Day 42 of IH or IA | 26.3 ± 1.5# | 25.7 ± 1.6* | 27.0 ± 1.8 | 26.2 ± 1.8* |

| Food intake, g/day | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.6 |

| Epididymal fat, g | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.02§ | 0.50 ± 0.0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.04 |

| Plasma epinephrine, ng/ml | 1.14 ± 0.15 | 1.98 ± 0.23§ | 1.08 ± 0.12 | 1.20 ± 0.27 |

| Plasma norepinephrine, ng/ml | 6.98 ± 1.28 | 6.80 ± 0.71 | 8.47 ± 0.46‡ | 7.46 ± 1.86‡ |

| Plasma corticosterone, ng/ml | 72.0 ± 9.4 | 78.0 ± 19.1 | 65.5 ± 7.4 | 73.9 ± 8.7 |

| Plasma leptin, ng/ml | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| Plasma adiponectin, ng/ml | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 1.4 |

| Fasting plasma triglycerides, mg/dl | 26.9 ± 2.4 | 30.1 ± 1.8 | 31.1 ± 1.1 | 29.9 ± 3.5 |

| Fasting plasma cholesterol, mg/dl | 76.5 ± 4.6 | 97.3 ± 4.7§ | 86.9 ± 2.7 | 89.41 ± 3.7 |

| Fasting plasma free fatty acids, mmol/l | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.33 ± 0.02 |

| Fasting plasma glycerol, mmol/l | 0.034 ± 0.006 | 0.041 ± 0.005 | 0.033 ± 0.010 | 0.040 ± 0.007 |

| Liver triglyceride, mg/g of tissue | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 10.5 ± 1.5† | 7.1 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 0.5 |

Values are means ± SE.

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 for the difference between day 0 and day 42, respectively.

: P < 0.01 and P < 0.05 for the effects of CIH and CSND, respectively.

P = 0.056 for the effect of CSND.

P < 0.05 for the effect of CIH.

CSND.

CSND was performed under 1–2% isoflurane anesthesia and body temperature was maintained at 37°C. The CSNs were bilaterally dissected at the points of branching from the glossopharyngeal nerve to the cranial pole of the carotid body. During the early postoperative period (3 days), penicillin G at 1,000 U sc. twice per day was administered to prevent infection and buprenorphine at 0.05 mg·kg−1·day−1 sc was administered to prevent discomfort. Sham surgery was performed in a similar manner except that the CSNs were not severed.

Minute ventilation and the hypoxic ventilatory response.

Minute ventilation (V̇e) and the hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) were measured prior to IH, after 2 or 4 wk of IH as previously described by our laboratory (59). The animals were placed in a whole body barometric plethysmography chamber to measure ventilation. The ports through which the gases enter and exit the chamber were closed to produce a constant chamber volume. Once the chamber is at constant volume, VT (tidal volume) and F (frequency) were measured from changes in pressure (Statham Gould PM15E differential pressure transducer, Hato Ray, Puerto Rico). Calibration injections of 10, 20, and 30 μl of room air were made with the animal inside the constant volume chamber. V̇e was reported as VT × f. VE was measured during quiet wakefulness at baseline, 21% O2 (15 min × 2), and in response to 10% O2.

Intermittent hypoxia.

IH was performed as previously described (28). Briefly, a gas control delivery system was designed employing programmable solenoids and flow regulators, which controlled the flow of air, nitrogen, and oxygen into cages. During each cycle of IH, the percentage of O2 decreased from ∼21% to ∼6–7% over a 30-s period, followed by a rapid return to ∼21% over the subsequent 30-s period. This regimen of IH induces oxyhemoglobin desaturations from 99% to ∼65%, 60 times/h (28). A control group was exposed to an identical regimen of intermittent air (IA) delivered at the same flow rate as IH. The IA group was weight matched to the IH group by varying food intake as previously described (28). IH and IA were administered during the light phase (9 a.m. to 9 p.m.) for 2 wk (for blood pressure telemetry and baroreflex measurements), 4 wk (for insulin signaling measurements), or 6 wk (for all other measurements).

Blood pressure and baroreflex.

In 12 mice (sham surgery, n = 9; CSND, n = 9), blood pressure telemeters (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) were implanted in the left femoral artery at the time of the CSND or sham surgery. Mice were recovered for 72 h and then exposed to IH. Blood pressure was recorded at baseline after a 2-wk recovery and then after 1 day, 8 days, and 14 days of IH. Each recording was performed for 24 h, and the average mean blood pressure was determined. We were unable to obtain reliable blood pressure telemetry recordings after 4 and 6 wk of IH due to technical limitations.

For baroreflex determination, the left femoral venous catheters we implanted simultaneously with the telemeters in a subgroup of mice (sham surgery, n = 5; CSND, n = 5). Mice were recovered for 72 h, and the acute baroreflex was assessed by heart rate reductions during an intravenous bolus of phenylephrine (10 μg in 100 μl) to acutely raise blood pressure (26) on days 0, 7, and 14 of the IH. Baseline blood pressure and heart rate were determined based on average values for 5 min immediately preceding the phenylephrine bolus. The baroreflex was determined based on acute reduction in heart rate immediately after phenylephrine administration.

Pulse oximetry.

Pulse oximetry (SpO2) was measured during week 5 of the experiment in 23 conscious mice during IH and IA exposures for 1 h (IA-sham, n = 5; IH-sham, n = 5; IA-CSND, n = 5; IH-CSND, n = 8) by applying a Mouse CollarClip (Starr Life Sciences, Oakmont, PA). Prior to measurements animals were conditioned to the neck collar for 4–6 h. In IA mice, SpO2 was averaged throughout the observation period. In IH mice, SpO2 was also averaged throughout the observation period of IH; nadirs and peaks of SpO2 were also identified and averaged.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed during week 4 of IH or IA exposures in unanesthetized animals. IPGTT was performed after a 5-h fast by injecting 1 g/kg glucose intraperitoneally. Glucose levels were measured by tail-snip technique using a hand-held glucometer (Accu-Check Aviva, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) at baseline and at 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after glucose injection. The homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index was calculated as fasting serum insulin (μU/ml) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/l)/22.5.

Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp.

The hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp was performed in conscious mice during week 6 of exposure to IH or IA as previously described (26, 31, 32, 76). Briefly, under 1–2% isoflurane anesthesia, catheters (MRE025 Braintree Scientific) were chronically implanted in the left femoral artery and vein for measurement of blood glucose and infusion of solutions. The catheters were perfused throughout the recovery period by an infusion pump with a sterile saline solution containing heparin (20 U/ml). Animals were allowed 72 h to recover from surgery. IH or IA exposures were continued during recovery and the clamp. The baseline hepatic glucose output was first determined by infusing [3-3H]glucose (10 μCi bolus + 0.1 μCi/min; NEN Life Science Products) for 80 min and then acquiring a 100-μl plasma sample to measure [3-3H]glucose level. Blood was then centrifuged at 10,000 g and supernatant collected. Red blood cells were resuspended in heparinized saline and reinfused into the mouse. Subsequently a 120-min hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp was conducted with continuous infusion of human insulin (20 mU·kg−1·min−1; Novalin R, Novo Nordisk, Princeton, NJ). Blood samples were collected from the femoral artery catheter at 10-min intervals with an Accu-Chek Aviva glucometer for the immediate measurement of glucose concentration, and 50% glucose was infused at variable rates through the femoral venous catheter to maintain blood glucose at ∼100–125 mg/dl. Insulin-stimulated whole body glucose flux was estimated using continuous infusion of [3-3H]glucose (0.1 μCi/min) throughout the clamp. The hepatic glucose output during the clamp was calculated by subtracting the cold glucose infusion rate from the insulin-stimulated whole body glucose flux (31, 32).

Insulin signaling.

The animals underwent CSND or sham surgery and after recovery for 2 wk were exposed to IH or IA for 4 wk. At the end of the exposure, the animals were injected with insulin at 5 U/kg or normal saline intraperitoneally and euthanized under 1–2% isoflurane 15 min after injection. Liver tissue, skeletal muscle (quadriceps), and epididymal fat were collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Insulin signaling was assessed by measuring phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) to total Akt ratios after insulin injection. The tissues were homogenized in the whole lysate buffer. SDS-PAGE and Western blot were performed using Bio-Rad precast gel system. Protein (30 μg) was applied per lane. For total Akt and pAkt (Ser473) measurements, we used rabbit polyclonal antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers MA), cat no. 9272 and no. 9271, respectively, diluted 1:2,000. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) detected with G9295 antibody from Sigma was used as a loading control. The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase conjugate from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Optical density of Akt and pAkt (60 kDa) was measured with ImageJ Software.

Biochemical assays.

Plasma insulin, adiponectin, and leptin were measured with ELISA kits from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine were measured with ELISA kits from Rocky Mountain Diagnostics (Colorado Springs, CO). Fasting plasma total cholesterol, free fatty acids (FFA), and triglycerides were measured with kits from Wako Diagnostics (Richmond, VA). Glycerol was measured with a colorimetric assay from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Corticosterone and glucagon were determined with ELISA kits from R&D Systems, (Minneapolis, MN).

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) staining of liver tissue.

After 1 day of IH or IA, animals were euthanized as described above, and the right lobe of the liver was collected, fixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight, and then immersed in 2% Triton-X 100 solution for 2 days at 15°C for permeabilization as we have previously described (18). The tissue was labeled with a polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse TH (Millipore, AB152, Billerica, MA) and an Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) to reveal sympathetic fibers and propidium iodide (Invitrogen) to label the nuclei. High-resolution, 3D-confocal imaging of the optical-cleared specimens was performed with a Zeiss LSM 710NLO confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). After 6 wk of IH or IA, animals were euthanized as described above, and the right lobe of the liver was collected, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned at 3- to 5-μm thickness and stained with primary antibodies against TH and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and with smooth muscle actin antibody (Sigma) and Alexa Fluor 647 anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), examined with a Leica TCS SP5 microscope and analyzed with the accompanying Leica Application Suite software (Leica Microsystems CMS, Mannheim, Germany).

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from liver using Trizol (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD), and cDNA was synthesized using Advantage RT for PCR kit from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with primers from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and Taqman probes from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The sequences of primers and probes for mouse 18S were previously described (41). Mouse phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose 6-phosphatase (G-6-Pase) mRNA have been measured with the Applied Biosystems pre-made primers and probes. The mRNA expression levels were referenced to 18S rRNA and the values were derived according to the 2−ΔΔCt method (73).

Statistical analysis.

All values are reported as means ± SE. Statistical significance for all comparisons was determined by two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. For IPGTT and ITT, we performed a repeated-measures ANOVA test, and significance was determined using Tukey's post hoc test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

At the onset of the IH exposure, mice subjected to CSND and sham surgery had identical body weight (Table 1). By the end of the experiment, chronic IH resulted in weight loss. Similar weight loss by design occurred in the control IA groups, which were weight matched to the hypoxic animals by varying food intake. In sham-operated mice, chronic IH decreased the size of epididymal fat pads and increased liver fat, which was consistent with our previously published data (12). CSND prevented loss of epididymal fat and hepatic fat accumulation. IH increased levels of plasma epinephrine in sham-operated mice, and this increase was abolished by carotid body denervation. CSND increased plasma norepinephrine levels, whereas IH had no effect (Table 1).

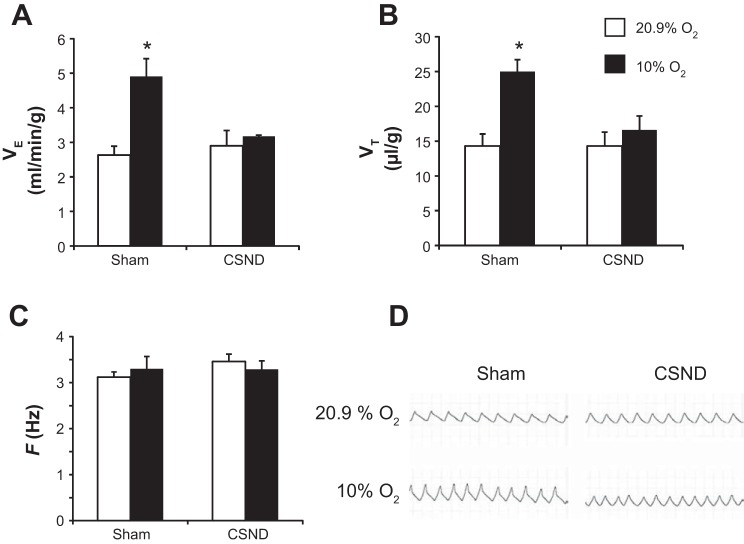

In sham-operated mice, acute exposure to 10% O2 induced a 1.8-fold increase in V̇e (Fig. 1A) due to increases in VT, whereas the respiratory rate was unchanged (Fig. 1, B–D). There was no significant change in V̇e from the pre-IH level after 2 and 4 wk of IH. After IH for 4 wk, sham-operated mice continued to demonstrate the robust HVR raising V̇e from 3.0 ± 0.2 ml·min−1·g body weight−1 in room air to 4.2 ± 0.3 ml·min−1·g body wt−1 in 10% O2 (P < 0.05). CSND abolished the HVR (Fig. 1). After IH for 4 wk, CSND mice had identical V̇e to the sham-operated mice (3.0 ± 0.3 ml·min−1·g body weight−1), but there was no significant hyperventilation in 10% O2 (3.5 ± 0.3 ml·min−1·g body weight−1).

Fig. 1.

Minute ventilation per body weight (V̇e; A), tidal volume per body weight (VT; B), and respiratory rate per s (F; C) were measured in C57BL/6J mice subjected to carotid sinus nerve dissection (CSND) or sham surgery during acute exposure to hypoxia (10% O2 for 15 min) or room air (20.9% O2) in a whole body barometric plethysmography chamber. *P < 0.01 for the difference with 20.9% O2 and with CSND. Representative tracings are shown in D.

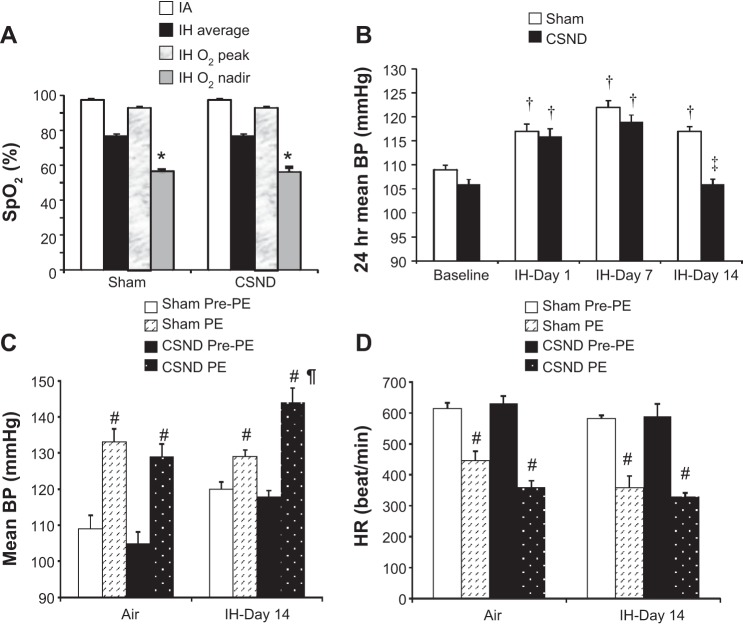

Both CSND and sham-operated mice exhibited similarly severe oxyhemoglobin desaturations during IH (Fig. 2A). At baseline normoxic conditions carotid body denervation did not affect blood pressure. IH caused hypertension in both CSND and sham-operated mice on day 1 and day 7 of exposure (Fig. 2B). In CSND mice, blood pressure returned to the normoxic baseline by day 14, whereas sham-operated mice remained hypertensive. Phenylephrine induced similar increases in blood pressure and reflex bradycardia in both CSND and sham-operated mice at baseline normoxic conditions (Fig. 2, C and D). In sham-operated mice, IH for 14 days did not significantly modify the effect of phenylephrine on blood pressure and heart rate (Fig. 2D). In contrast, in CSND mice IH augmented the phenylephrine effect on blood pressure, whereas reflex bradycardia did not change (Fig. 2, C and D), suggesting that CSND blunted the baroreflex during IH.

Fig. 2.

Oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2, A) during the intermittent hypoxia (IH) cycle in C57BL/6J mice subjected to CSND or sham surgery. IA, intermittent air. B: 24-h average mean blood pressure in CSND and sham-operated mice before and during exposure to IH. Mean blood pressure (BP; C) and heart rate (D) prior to and immediately after phenylephrine (PE) administration. *P < 0.001 between SpO2 during the nadir and peak of the hypoxic cycle; †P < 0.001 for the effect of IH; ‡P < 0.001 and ¶P < 0.05, respectively, for the effect of CSND; #P < 0.001 for the effect of PE.

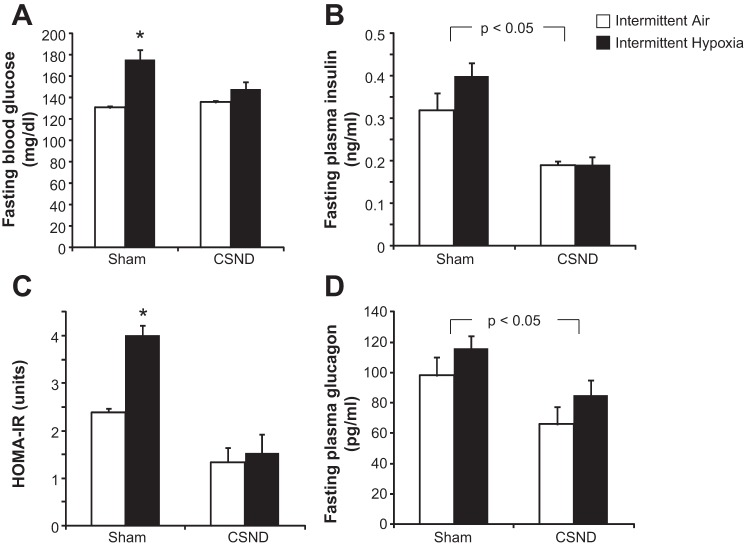

IH increased liver triglyceride content and plasma total cholesterol levels, and these effects were abolished by CSND (Table 1). Fasting plasma levels of free fatty acids, triglycerides, glycerol, corticosterone, leptin, and adiponectin were not changed by our interventions. In sham-operated mice, IH increased fasting blood glucose level without change in plasma insulin, resulting in a 1.7-fold increase in the HOMA-IR (Fig. 3, A–C). CSND prevented an IH-induced increase in fasting blood glucose. CSND led to a 1.7-fold decrease in fasting plasma insulin in normoxic sham-operated mice and a 2-fold decrease in hypoxic sham-operated mice, which resulted in 2.6-fold and 3.4-fold decreases in the HOMA-IR, respectively. IH did not affect plasma glucagon level, but CSND markedly decreased it (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Effects of CSND on fasting blood glucose (A), fasting serum insulin (B), the homeostatic model assessment index of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR; C), and fasting serum glucagon (D) in C57BL/6J mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia (IH) or intermittent air (IA). *P < 0.001 for the difference with IA-sham, P < 0.01 for the difference with IH-CSND and IA-CSND.

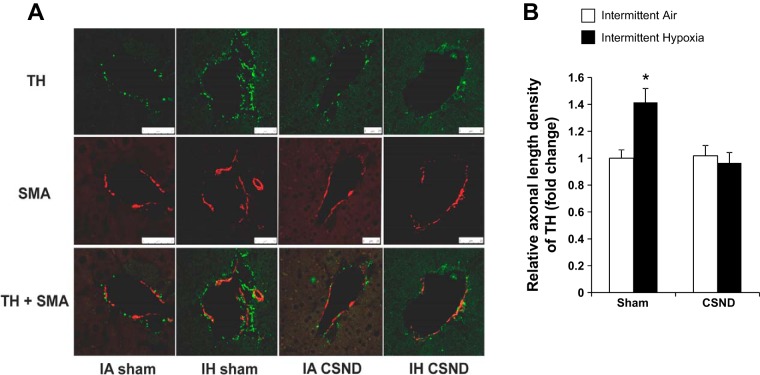

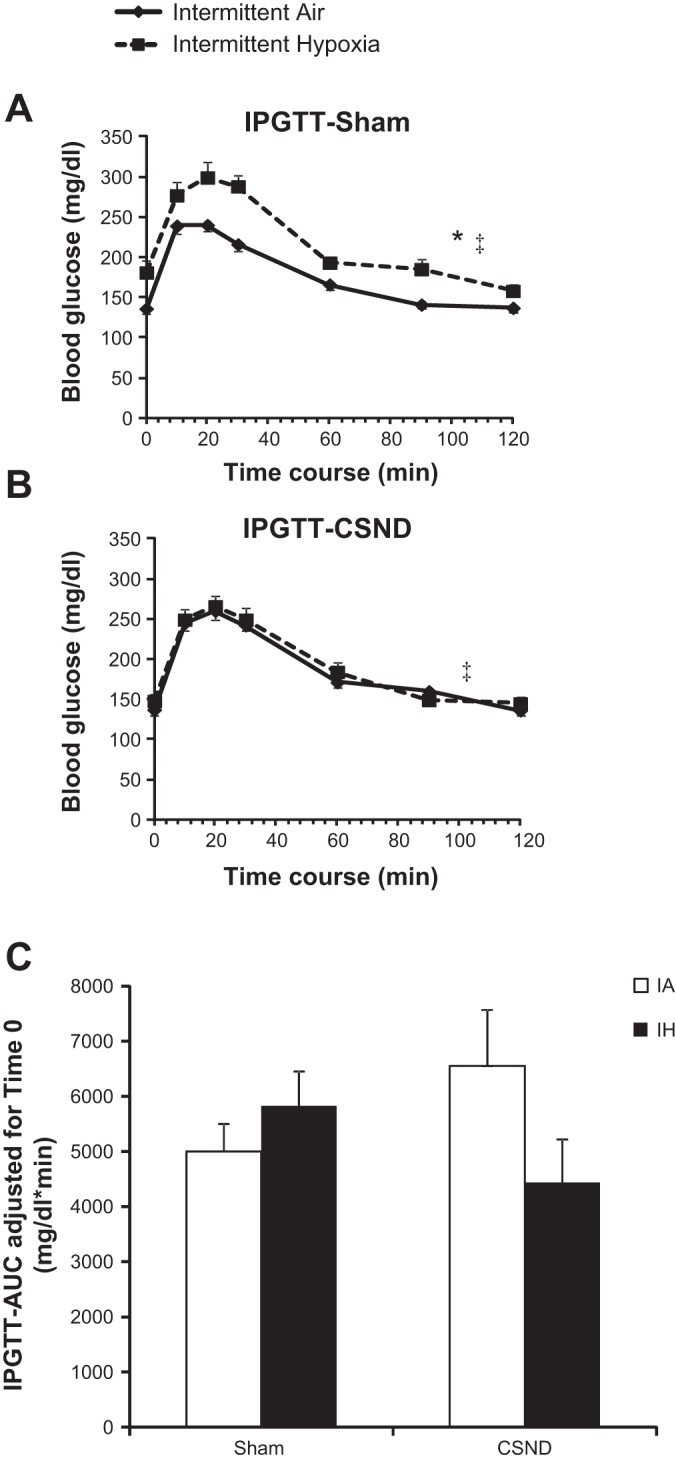

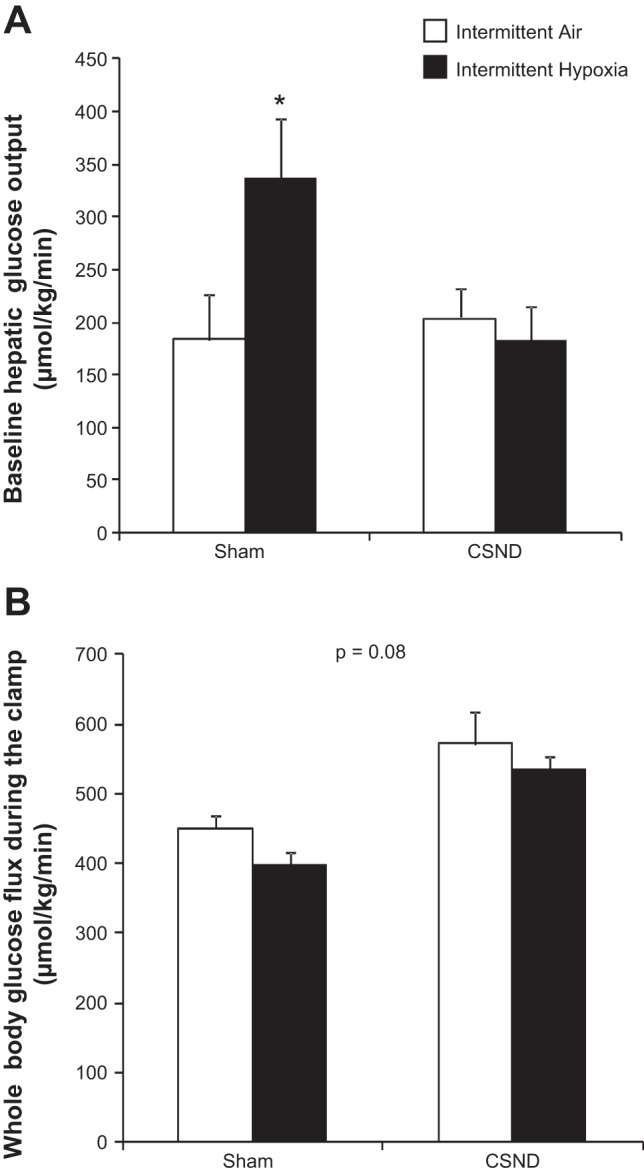

Chronic IH caused elevation in blood glucose levels throughout the IPGTT, which was prevented by carotid body denervation (Fig. 4, A and B). However, there were no differences in the area under curve between the groups after adjustment for fasting glucose levels at time 0 (Fig. 4C). In sham-operated fasting mice, IH induced an 84% increase in baseline hepatic glucose output, which was abolished by CSND (Fig. 5A). During the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, plasma insulin level was raised to 146 ± 12.7 μU/ml, which is equivalent to 5.1 ± 0.4 ng/ml, without significant differences between the groups. IH did not affect the insulin-stimulated whole body glucose flux (Fig. 5B). CSND induced a trend to an increase in insulin-stimulated glucose flux, regardless of the exposure. Hepatic glucose output during the clamp was completely suppressed in all groups of mice.

Fig. 4.

Effect of CSND on glucose tolerance in the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) in C57BL/6J mice exposed to IH or IA. A: IPGTT in sham-operated mice. B: IPGTT in CSND-operated mice. C: IPGTT area under the curve (AUC) after adjustment for blood glucose level at time 0. *P < 0.001 for the effect of IH in sham-operated mice; ‡P < 0.01 for the effect of CSND in IH exposure.

Fig. 5.

Effect of CSND on the baseline hepatic glucose output (A) and insulin-stimulated whole body glucose flux (B) in C57BL/6J mice exposed to IH or IA. *P < 0.05 for the difference between CSND-IH and all other groups.

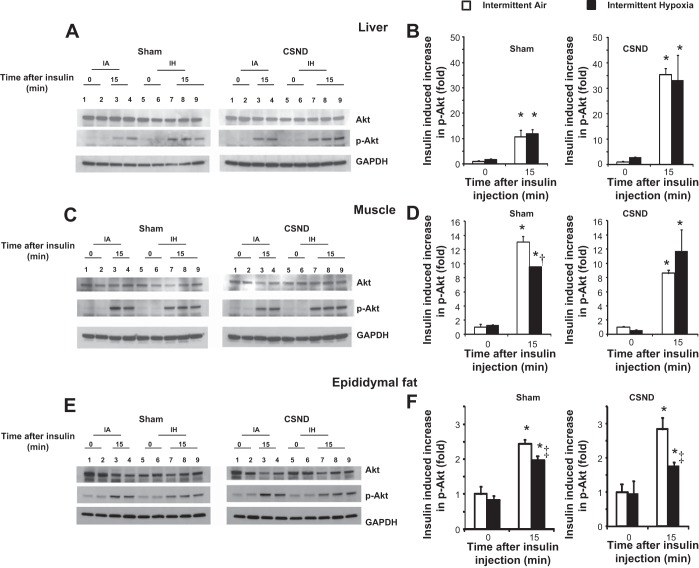

In the liver, CSND increased insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation, regardless of the presence of hypoxia (P = 0.001, Fig. 6, A and B). In skeletal muscle, chronic IH decreased Akt phosphorylation, and this effect was abolished by CSND (Fig. 6, C and D). In epididymal fat, IH decreased Akt phosphorylation, but CSND had no effect (Fig. 6, E and F).

Fig. 6.

Effect of CSND on Akt Ser 473 phosphorylation (p-Akt) in the liver, skeletal muscle, and epididymal fat of C57BL/6J exposed to chronic IH or IA. Mice were euthanized at baseline (time 0) or 15 min after insulin injection (time 15). Representative samples and quantitative analysis of liver (A and B), skeletal muscle (C and D), and epididymal fat (E and F) from mice subjected to sham surgery or CSND and exposed to IA or IH are shown. p-Akt optical density (OD) was divided by total Akt and all values were normalized to p-Akt/Akt in IA mice at time 0. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. On A, C, and E, lanes 1 and 2 represent mice exposed to IA at time 0; lanes 3 and 4 represent mice exposed to IA at time 15; lanes 5 and 6 represent mice exposed to IH at time 0, and lanes 7–9 represent mice exposed to IH at time 15. *P < 0.001 for the effect of insulin (time 0 vs. time 15); † and ‡: P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively, for the effect of IH.

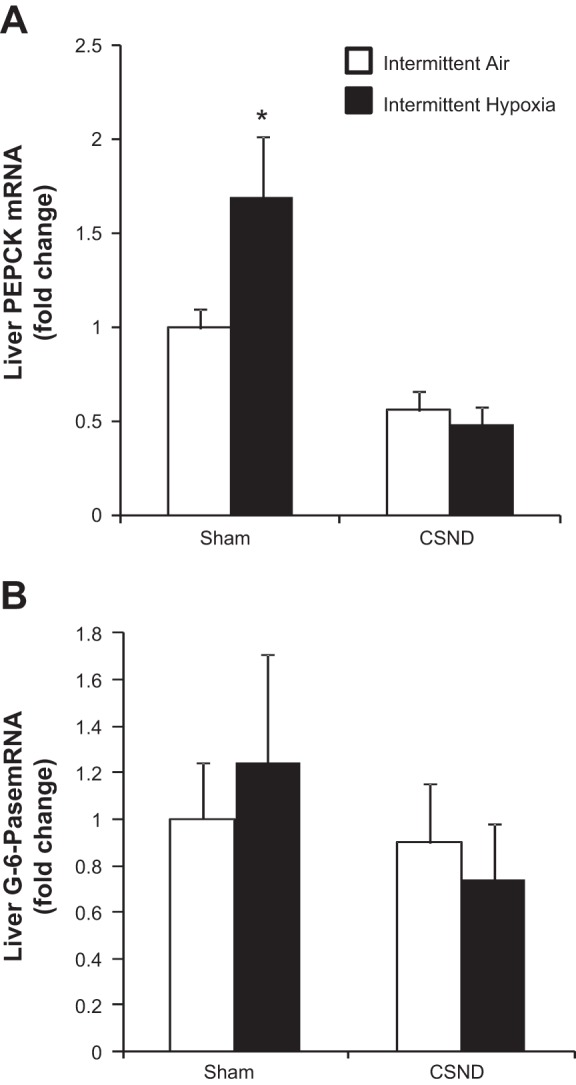

Expression of key enzymes of gluconeogenesis, PEPCK and G-6-Pase, was assessed in the liver (Fig. 7). IH had a strong trend to increase PEPCK mRNA levels (P = 0.057), which was abolished by CSND. Carotid body denervation decreased hepatic PEPCK gene expression during IH by 3-fold (P < 0.001), whereas normoxic mice were not affected (Fig. 7A). Neither chronic IH nor CSND affected liver G-6-Pase gene expression (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effects of CSND on liver enzymes of gluconeogenesis in C57BL/6J mice exposed to IH or IA. A: mRNA expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK). B: mRNA expression of glucose 6-phosphatase (G-6-Pase). *P < 0.001 for the difference with IH-CSND group and P = 0.057 for the difference with IA-sham.

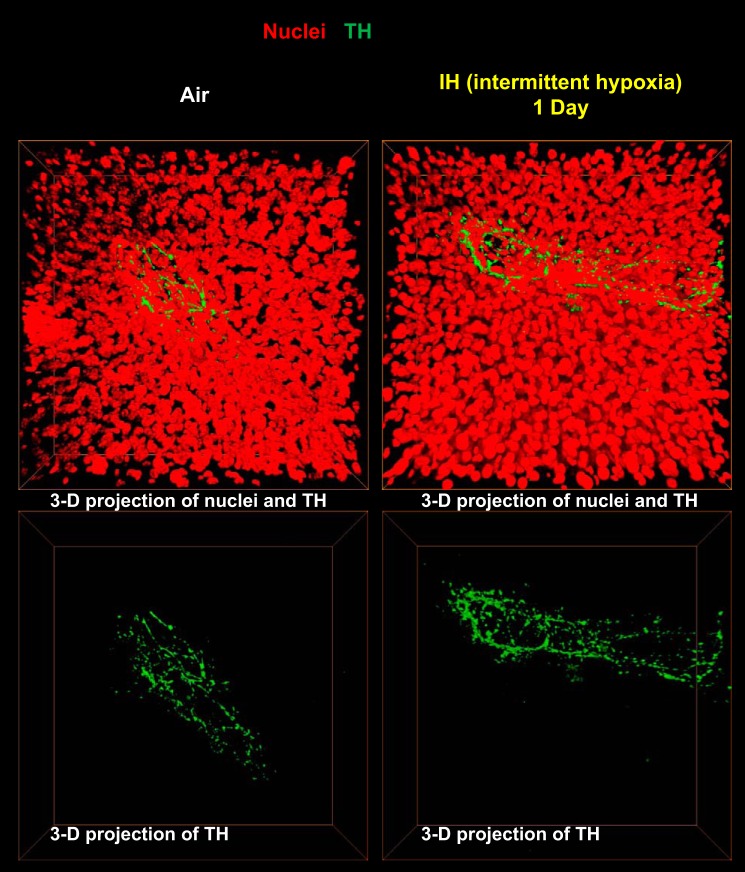

Given that IH had the most striking effect on fasting hepatic glucose output, we determined the effect of IH on sympathetic innervation in the liver. TH staining, which is a conventional method to measure sympathetic innervation in different organs (18, 50), showed sympathetic fibers surrounding blood vessels in the hepatic triads (Fig. 8). There was no TH staining within the hepatic lobules, which is consistent with a classical concept of perivascular liver sympathetic innervation in mice and rats confined to the hepatic triads (43, 49). There was no significant change in the liver sympathetic innervation after 1 day of IH. Next we examined the effect of chronic IH on sympathetic innervation in the liver and the role of the carotid bodies. As in the 3D images (Fig. 8), TH staining was confined to the hepatic triads, where sympathetic nerves were adjacent to smooth muscle of the blood vessel wall (Fig. 9). In contrast to 1 day exposure, IH for 6 wk resulted in a 1.4-fold increase in sympathetic innervation. The increase in sympathetic innervation was prevented by CSND (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Representative 3-D images of sympathetic fibers surrounding major vessels in the liver stained with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, green) antibody (×100) after 1 day of IH or control conditions. TH is in green; nuclei are in red.

Fig. 9.

Effect of CSND on liver TH in C57BL/6J mice exposed to IH or IA control conditions. A: representative slides of liver tissue stained for TH and smooth muscle actin (SMA). Immunofluorescence, ×100; white bars represent 25 μm. B: fold change in liver TH level compared with the IA-sham group. *P < 0.05 for the difference with IA-sham, IH-CSND, and IA-CSND.

DISCUSSION

OSA has been independently associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which were attributed to the hallmark manifestation of OSA, chronic IH during sleep. We aimed to examine a potential role of the carotid body signaling in dysregulation of glucose metabolism in our mouse model of chronic IH. The main finding of the study was that CSND prevented IH-induced perturbations of hepatic glucose metabolism. Specifically, we have shown that IH induced fasting hyperglycemia, increasing baseline hepatic output and expression of the rate-limiting enzyme of hepatic gluconeogenesis, PEPCK, which were attenuated by CSND. We report several other novel findings. First, IH augmented sympathetic innervation to the liver and increased plasma epinephrine, and both increases were abolished by CSND. Second, IH inhibited insulin signaling in skeletal muscle and epididymal adipose tissue, but did not affect glucose tolerance and insulin resistance measured by the whole body glucose flux during the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp. Third, CSND trended to improve whole body insulin sensitivity, decreased plasma insulin and glucagon levels, activated insulin signaling in the liver, and prevented an IH-mediated decrease in insulin signaling in skeletal muscle. In the discussion below we will elaborate on mechanisms of fasting hyperglycemia during IH and implications of our work.

Carotid body and SNS efferent output in IH.

Carotid bodies are richly vascularized organs, which reside bilaterally at the bifurcation of the carotid arteries (53, 60). They are major sensors for hypoxia and sensory discharges from the carotid bodies, which are transmitted by the CSN to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the medulla, resulting in the activation of medullary neurons regulating spinal preganglionic sympathetic activity (22, 65, 77). Human OSA and rodent chronic IH activate carotid bodies augmenting acute responses to hypoxia and increasing baseline sensory activity (63). IH also increases cervical, renal, splanchnic, thoracic, and lumbar sympathetic nerve activity (8, 23, 25, 45, 65), which may represent the efferent limb of the carotid chemoreflex. We employed the CSND model to examine the role of hypoxic chemoreflex in metabolic complications of IH. In our experiments, CSND abolished the HVR (Fig. 1), indicating that the procedure successfully reduced the carotid body output. IH did not augment the hypoxic chemoreflex. The heterogeneity of HVR changes in IH has been noted previously and has been attributed to differences in patterns and duration of the IH stimulus (61). Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species play a critical role in the HVR augmentation in the carotid body (62, 64). Our regimen of IH leads to relatively modest oxidative stress (29, 69), which may explain the lack of changes in the HVR. Nevertheless, the difference in the HVR between sham and CSND mice persisted throughout IH exposure, suggesting that the hypoxic chemoreflex is a probable mechanism of the increased SNS efferent output during IH.

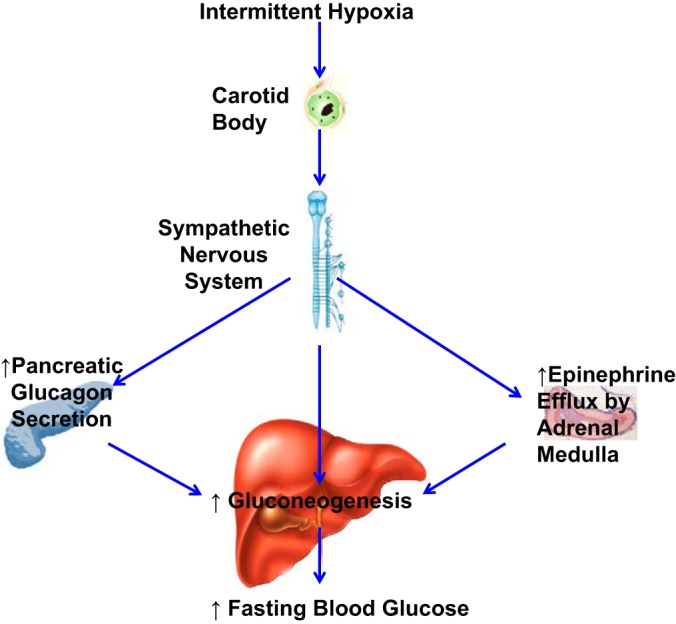

CSN provides sensory innervation to both carotid bodies and carotid sinus baroreceptors (35, 53, 60). An important question is whether we can associate CSND-mediated metabolic changes with the chemoreflex. Carotid body denervation and baroreceptor denervation have opposite effects on sympathetic activity: the former induces inhibition, and the latter leads to excitation, although each sensor may differentially influence the sympathetic outflow to different organs (60). In sham-operated mice, we did not observe blunting of the baroreflex previously reported in IH (24, 42). In contrast, CSND markedly augmented phenylephrine-induced hypertension during IH with the same degree of the negative chronotropic response indicating diminished baroreflex (Fig. 2, C and D). Despite the decreased baroreflex, 24-h blood pressure recording showed that CSND reversed IH-induced hypertension (Fig. 2B), which is also consistent with earlier findings in rats (38). This paradox indicates that carotid sinus baroreceptors do not play a major role in IH-induced hypertension. Taken together, our data suggest that CSN is implicated in IH-induced hypertension due to the hypoxic chemoreflex in the carotid bodies rather than via the blunted baroreflex in the carotid sinus. We further conclude that the augmented carotid body sensory output during IH increased sympathetic innervation of the liver (Fig. 9), resulting in increased hepatic glucose output (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Putative role of carotid bodies in fasting hyperglycemia in IH. IH stimulates the carotid body chemoreflex, which activates efferent sympathetic nervous system (SNS). SNS activation increases glucagon secretion in the pancreas and epinephrine efflux by the adrenal medulla. Increased SNS innervation in the liver, glucagon, and epinephrine enhance hepatic gluconeogenesis, which causes fasting hyperglycemia.

IH increased plasma epinephrine level in sham-operated mice (Table 1). The adult adrenal medulla is insensitive to acute hypoxia (80), but IH increases epinephrine efflux from the adrenal medulla (36, 38). Adrenalectomy prevented elevation of plasma catecholamines and IH-induced hypertension (2, 38). Systemic treatment of rats with antioxidants prevented acute hypoxia-induced catecholamine efflux in rats exposed to IH (36). However, it remains unclear whether IH exerts a direct effect on adrenals or whether this effect is mediated by the carotid bodies. Adrenal medulla has rich pre- and postganglionic sympathetic innervation (30, 56, 74, 75). Our data showed that the IH-induced increase in plasma epinephrine was prevented by CSND (5, 36, 38, 77). All of above suggest that, in the IH environment, the hypoxic chemoreflex may lead to adverse metabolic outcomes via the increase in the epinephrine efflux by adrenal medulla (Fig. 10).

SNS and dysregulation of glucose metabolism during IH.

We have consistently shown in the past that fasting hyperglycemia is one of the most reproducible metabolic effects of IH, which suggests that increased hepatic glucose output is a consequence of IH (11, 13, 40, 72) (58). Acute IH for 9 h trended to increase the baseline hepatic glucose output measured by radioactive glucose infusion (26). Our present data showed that IH-induced fasting hyperglycemia was associated with upregulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis, which was evident from an increase in expression of PEPCK, a transcriptionally controlled rate-limiting enzyme of gluconeogenesis (Fig. 7A). IH did not affect Akt phosphorylation in the liver (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the hepatic effect of IH was insulin-independent, probably due to the direct impact of catecholamines on gluconeogenesis.

CSND prevented fasting hyperglycemia, an increase in baseline hepatic glucose production, and upregulation of the key enzyme of gluconeogenesis, PEPCK, which suggests downregulation of gluconeogenesis. CSND-mediated decreases in hepatic sympathetic innervation could downregulate gluconeogenesis directly, via increased sympathetic innervation and increased epinephrine efflux by the adrenal medulla, and indirectly, via a decrease in glucagon levels (Fig. 3D) (27, 83) and enhanced insulin signaling in the liver (Fig. 6A). CSND abolished IH-induced triglyceride accumulation in the liver and decreased epididymal fat pads (Table 1), which suggests that CSND may improve insulin signaling by suppressing the influx of free fatty acids to the liver that resulted from catecholamine-mediated adipose tissue lipolysis (52, 81). The lack of change of circulating fatty acids and glycerol measured at a single time point in our study did not negate previous findings of accelerated lipolysis in chronic IH (28), which could occur earlier in the time course. In humans, sympathetic inhibition with the centrally acting α2 agonist clonidine prevented hypoxia-induced insulin resistance (57). Our data implicate the carotid body chemoreflex in the development of hyperglycemia during IH.

IH decreased Akt phosphorylation in epididymal adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, whereas insulin resistance was not affected. Acute IH (1 day) is known to induce systemic insulin resistance (26, 37), which was diminished but still persistent after 4 wk of exposure (37). It is conceivable that chronic IH activates protective mechanisms in different tissues compensating for downregulation of insulin signaling.

The effects of carotid denervation on systemic insulin resistance independent of hypoxia have been reported (71). Our data suggest that a beneficial impact of CSND on insulin resistance occurs in liver and skeletal muscles because CSND enhanced insulin signaling in these tissues while adipose tissue was not affected (Fig. 6).

Fasting hyperglycemia in IH did not result in a significant compensatory increase of plasma insulin, which suggests that IH may suppress insulin secretion by the pancreatic β cells. Indeed, inhibitory effects of IH on insulin secretion have been previously detected by intravenous glucose tolerance test in mice, rats, and humans (15, 37, 44). CSND simultaneously decreased fasting insulin and glucose levels (Fig. 3), suggesting that the CSN improved insulin resistance rather than directly affected the pancreatic endocrine function.

Limitations of the study.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not measure tissue catecholamine content and could not determine whether CSND prevents an increase in hepatic output via sympathetic liver nerves or circulating catecholamines. In future studies these measurements could assess SNS activity in different organs. Second, we were unable to perform telemetry and phenylephrine infusions during the entire 4- to 6-wk exposure to IH. However, our data suggest that IH induced hypertension within the first 24 h of exposure, and this hypertension persisted for 2 wk. Third, the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp has been performed using a high dose of insulin completely suppressing the hepatic glucose output. It is conceivable that at a lower concentration of insulin, we would be able to detect effects of IH and CSND on the hepatic glucose output during the clamp (33). Fourth, we did not perform the intravenous glucose tolerance test, which would determine the role of the carotid bodies in the β-cell function. However, concomitant decreases in fasting glucose and insulin after CSND suggest improvement in insulin resistance during IH rather than a direct effect on insulin secretion. Fifth, C56BL/6J mice used in our experiments are more susceptible to both metabolic abnormalities and ventilatory instabilities during hypoxia, compared with other mouse strains (7, 21, 79), and our findings may not be generalizable. However, we have reported fasting hyperglycemia and metabolic abnormalities during IH in other strains of mice (40). Several studies indicate that the carotid bodies are involved in regulation of glucose metabolism in rats (19, 71, 82). It is conceivable that the carotid bodies mediate variations in the metabolic phenotypes between different mouse strains.

Conclusions and clinical implications.

We have shown that the carotid bodies play a major role in the development of fasting hyperglycemia during chronic IH (Fig. 10). Our findings suggest that sympathetic blockers can be tested as adjunct therapy of type 2 diabetes in OSA.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-080105 (V. Y. Polotsky), HL-084945 (A. R. Schwartz and V. Y. Polotsky), and HL-109475 (J. C. Jun), and American Heart Association Grants 10GRNT-3360001 (V. Y. Polotsky) and 12POST-118200001 (M.-K. Shin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.-K.S., Q.Y., S.B.-F., D.-Y.Y., W.H., O.M., R.A.R., Y.-Y.F., A.R.S., and M.S. performed experiments; M.-K.S., Q.Y., S.B.-F., R.A.R., Y.-Y.F., P.J.P., A.R.S., and V.Y.P. analyzed data; M.-K.S., J.C.J., Y.-Y.F., P.J.P., A.R.S., M.S., and V.Y.P. interpreted results of experiments; M.-K.S., J.C.J., M.S., and V.Y.P. approved final version of manuscript; J.C.J., P.J.P., M.S., and V.Y.P. conception and design of research; Y.-Y.F. and V.Y.P. prepared figures; M.S. and V.Y.P. edited and revised manuscript; V.Y.P. drafted manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronsohn RS, Whitmore H, Van CE, Tasali E. Impact of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on glucose control in type 2 diabetes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 507–513, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao G, Metreveli N, Li R, Taylor A, Fletcher EC. Blood pressure response to chronic episodic hypoxia: role of the sympathetic nervous system. J Appl Physiol 83: 95–101, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth E, Albuszies G, Baumgart K, Matejovic M, Wachter U, Vogt J, Radermacher P, Calzia E. Glucose metabolism and catecholamines. Crit Care Med 35: S508–S518, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartness TJ, Shrestha YB, Vaughan CH, Schwartz GJ, Song CK. Sensory and sympathetic nervous system control of white adipose tissue lipolysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 318: 34–43, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Critchley JA, Ellis P, Ungar A. The reflex release of adrenaline and noradrenaline from the adrenal glands of cats and dogs. J Physiol 298: 71–78, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delarue J, Magnan C. Free fatty acids and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 10: 142–148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeSantis DA, Lee P, Doerner SK, Ko CW, Kawasoe JH, Hill-Baskin AE, Ernest SR, Bhargava P, Hur KY, Cresci GA, Pritchard MT, Lee CH, Nagy LE, Nadeau JH, Croniger CM. Genetic resistance to liver fibrosis on A/J mouse chromosome 17. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37: 1668–1679, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick TE, Hsieh YH, Wang N, Prabhakar N. Acute intermittent hypoxia increases both phrenic and sympathetic nerve activities in the rat. Exp Physiol 92: 87–97, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drager LF, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. Metabolic consequences of intermittent hypoxia: relevance to obstructive sleep apnea. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 24: 843–851, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drager LF, Li J, Reinke C, Bevans-Fonti S, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. Intermittent hypoxia exacerbates metabolic effects of diet-induced obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19: 2167–2174, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drager LF, Li J, Reinke C, Bevans-Fonti S, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. Intermittent hypoxia exacerbates metabolic effects of diet-induced obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19: 2167–2174, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drager LF, Li J, Shin MK, Reinke C, Aggarwal NR, Jun JC, Bevans-Fonti S, Sztalryd C, O'Byrne SM, Kroupa O, Olivecrona G, Blaner WS, Polotsky VY. Intermittent hypoxia inhibits clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and inactivates adipose lipoprotein lipase in a mouse model of sleep apnoea. Eur Heart J 33: 783–790, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drager LF, Li J, Shin MK, Reinke C, Aggarwal NR, Jun JC, Bevans-Fonti S, Sztalryd C, O'Byrne SM, Kroupa O, Olivecrona G, Blaner WS, Polotsky VY. Intermittent hypoxia inhibits clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and inactivates adipose lipoprotein lipase in a mouse model of sleep apnoea. Eur Heart J 33: 783–790, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drager LF, Togeiro SM, Polotsky VY, Lorenzi-Filho G. Obstructive sleep apnea: a cardiometabolic risk in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: 569–576, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenik VB, Singletary T, Branconi JL, Davies RO, Kubin L. Glucoregulatory consequences and cardiorespiratory parameters in rats exposed to chronic-intermittent hypoxia: effects of the duration of exposure and losartan. Front Neurol 3: 51, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher EC, Lesske J, Behm R, Miller CC, Stauss H, Unger T. Carotid chemoreceptors, systemic blood pressure, and chronic episodic hypoxia mimicking sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol 72: 1978–1984, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster GD, Sanders MH, Millman R, Zammit G, Borradaile KE, Newman AB, Wadden TA, Kelley D, Wing RR, Sunyer FX, Darcey V, Kuna ST. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32: 1017–1019, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu YY, Peng SJ, Lin HY, Pasricha PJ, Tang SC. 3-D imaging and illustration of mouse intestinal neurovascular complex. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 304: G1–G11, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Fernandez M, Ortega-Saenz P, Castellano A, Lopez-Barneo J. Mechanisms of low-glucose sensitivity in carotid body glomus cells. Diabetes 56: 2893–2900, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gastaut H, Tassinari CA, Duron B. Polygraphic study of the episodic diurnal and nocturnal (hypnic and respiratory) manifestations of the Pickwick syndrome. Brain Res 1: 167–186, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillombardo CB, Yamauchi M, Adams MD, Dostal J, Chai S, Moore MW, Donovan LM, Han F, Strohl KP. Identification of novel mouse genes conferring posthypoxic pauses. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 167–174, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Martin MC, Vega-Agapito MV, Conde SV, Castaneda J, Bustamante R, Olea E, Perez-Vizcaino F, Gonzalez C, Obeso A. Carotid body function and ventilatory responses in intermittent hypoxia. Evidence for anomalous brainstem integration of arterial chemoreceptor input. J Cell Physiol 226: 1961–1969, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg HE, Sica A, Batson D, Scharf SM. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases sympathetic responsiveness to hypoxia and hypercapnia. J Appl Physiol 86: 298–305, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu H, Lin M, Liu J, Gozal D, Scrogin KE, Wurster R, Chapleau MW, Ma X, Cheng ZJ. Selective impairment of central mediation of baroreflex in anesthetized young adult Fischer 344 rats after chronic intermittent hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2809–H2818, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Lusina S, Xie T, Ji E, Xiang S, Liu Y, Weiss JW. Sympathetic response to chemostimulation in conscious rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 166: 102–106, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iiyori N, Alonso LC, Li J, Sanders MH, Garcia-Ocana A, O'doherty RM, Polotsky VY, O'Donnell CP. Intermittent hypoxia causes insulin resistance in lean mice independent of autonomic activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 851–857, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones BJ, Tan T, Bloom SR. Glucagon in stress and energy homeostasis. Endocrinology 153: 1049–1054, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jun J, Reinke C, Bedja D, Berkowitz D, Bevans-Fonti S, Li J, Barouch LA, Gabrielson K, Polotsky VY. Effect of intermittent hypoxia on atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 209: 381–386, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jun J, Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Bevans S, Li J, Smith PL, Polotsky VY. Intermittent hypoxia has organ-specific effects on oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1274–R1281, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kesse WK, Parker TL, Coupland RE. The innervation of the adrenal gland. I. The source of pre- and postganglionic nerve fibres to the rat adrenal gland. J Anat 157: 33–41, 1988 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JK, Gavrilova O, Chen Y, Reitman ML, Shulman GI. Mechanism of insulin resistance in A-ZIP/F-1 fatless mice. J Biol Chem 275: 8456–8460, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JK, Kim YJ, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Moore I, Lee J, Yuan M, Li ZW, Karin M, Perret P, Shoelson SE, Shulman GI. Prevention of fat-induced insulin resistance by salicylate. J Clin Invest 108: 437–446, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JK, Michael MD, Previs SF, Peroni OD, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Neschen S, Kahn BB, Kahn CR, Shulman GI. Redistribution of substrates to adipose tissue promotes obesity in mice with selective insulin resistance in muscle. J Clin Invest 105: 1791–1797, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight WD, Little JT, Carreno FR, Toney GM, Mifflin SW, Cunningham JT. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases blood pressure and expression of FosB/DeltaFosB in central autonomic regions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R131–R139, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kougias P, Weakley SM, Yao Q, Lin PH, Chen C. Arterial baroreceptors in the management of systemic hypertension. Med Sci Monit 16: RA1–RA8, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar GK, Rai V, Sharma SD, Ramakrishnan DP, Peng YJ, Souvannakitti D, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces hypoxia-evoked catecholamine efflux in adult rat adrenal medulla via oxidative stress. J Physiol 575: 229–239, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee EJ, Alonso LC, Stefanovski D, Strollo HC, Romano LC, Zou B, Singamsetty S, Yester KA, McGaffin KR, Garcia-Ocana A, O'Donnell CP. Time-dependent changes in glucose and insulin regulation during intermittent hypoxia and continuous hypoxia. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 467–478, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lesske J, Fletcher EC, Bao G, Unger T. Hypertension caused by chronic intermittent hypoxia—influence of chemoreceptors and sympathetic nervous system. J Hypertens 15: 1593–1603, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Bosch-Marce M, Nanayakkara A, Savransky V, Fried SK, Semenza GL, Polotsky VY. Altered metabolic responses to intermittent hypoxia in mice with partial deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Physiol Genomics 25: 450–457, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, Thorne LN, Punjabi NM, Sun CK, Schwartz AR, Smith PL, Marino RL, Rodriguez A, Hubbard WC, O'Donnell CP, Polotsky VY. Intermittent hypoxia induces hyperlipidemia in lean mice. Circ Res 97: 698–706, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin M, Liu R, Gozal D, Wead WB, Chapleau MW, Wurster R, Cheng ZJ. Chronic intermittent hypoxia impairs baroreflex control of heart rate but enhances heart rate responses to vagal efferent stimulation in anesthetized mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H997–H1006, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin YS, Nosaka S, Amakata Y, Maeda T. Comparative study of the mammalian liver innervation: an immunohistochemical study of protein gene product 9.5, dopamine beta-hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 110: 289–298, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louis M, Punjabi NM. Effects of acute intermittent hypoxia on glucose metabolism in awake healthy volunteers. J Appl Physiol 106: 1538–1544, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcus NJ, Li YL, Bird CE, Schultz HD, Morgan BJ. Chronic intermittent hypoxia augments chemoreflex control of sympathetic activity: role of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 171: 36–45, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 365: 1046–1053, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall NS, Wong KK, Liu PY, Cullen SR, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality: the Busselton Health Study. Sleep 31: 1079–1085, 2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshall NS, Wong KK, Phillips CL, Liu PY, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Is sleep apnea an independent risk factor for prevalent and incident diabetes in the Busselton Health Study? J Clin Sleep Med 5: 15–20, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Metz W, Forssmann WG. Innervation of the liver in guinea pig and rat. Anat Embryol (Berl) 160: 239–252, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulder J, Hokfelt T, Knuepfer MM, Kopp UC. Renal sensory and sympathetic nerves reinnervate the kidney in a similar time-dependent fashion after renal denervation in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R675–R682, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narkiewicz K, Kato M, Phillips BG, Pesek CA, Davison DE, Somers VK. Nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure decreases daytime sympathetic traffic in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 100: 2332–2335, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology 52: 774–788, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nurse CA, Piskuric NA. Signal processing at mammalian carotid body chemoreceptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol 24: 22–30, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oltmanns KM, Gehring H, Rudolf S, Schultes B, Rook S, Schweiger U, Born J, Fehm HL, Peters A. Hypoxia causes glucose intolerance in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169: 1231–1237, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pamidi S, Tasali E. Obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes: is there a link? Front Neurol 3: 126, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parker TL, Kesse WK, Mohamed AA, Afework M. The innervation of the mammalian adrenal gland. J Anat 183: 265–276, 1993 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peltonen GL, Scalzo RL, Schweder MM, Larson DG, Luckasen GJ, Irwin D, Hamilton KL, Schroeder T, Bell C. Sympathetic inhibition attenuates hypoxia induced insulin resistance in healthy adult humans. J Physiol 590: 2801–2809, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polak J, Shimoda LA, Drager LF, Undem C, McHugh H, Polotsky VY, Punjabi NM. Intermittent hypoxia impairs glucose homeostasis in C57BL6/J mice: partial improvement with cessation of the exposure. Sleep 36: 1483–1490, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polotsky VY, Wilson JA, Haines AS, Scharf MT, Soutiere SE, Tankersley CG, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, O'Donnell CP. The impact of insulin-dependent diabetes on ventilatory control in the mouse. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 624–632, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prabhakar NR. Sensing hypoxia: physiology, genetics and epigenetics. J Physiol 591: 2245–2257, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prabhakar NR, Kline DD. Ventilatory changes during intermittent hypoxia: importance of pattern and duration. High Alt Med Biol 3: 195–204, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prabhakar NR, Kumar GK. Oxidative stress in the systemic and cellular responses to intermittent hypoxia. Biol Chem 385: 217–221, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prabhakar NR, Kumar GK. Mechanisms of sympathetic activation and blood pressure elevation by intermittent hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 174: 156–161, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prabhakar NR, Kumar GK, Nanduri J, Semenza GL. ROS signaling in systemic and cellular responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 1397–1403, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prabhakar NR, Kumar GK, Peng YJ. Sympatho-adrenal activation by chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 113: 1304–1310, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Punjabi NM, Beamer BA. Alterations in glucose disposal in sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 235–240, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Punjabi NM, Caffo BS, Goodwin JL, Gottlieb DJ, Newman AB, O'Connor GT, Rapoport DM, Redline S, Resnick HE, Robbins JA, Shahar E, Unruh ML, Samet JM. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 6: e1000132, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, Gottlieb DJ, Givelber R, Resnick HE. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 160: 521–530, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reinke C, Bevans-Fonti S, Drager LF, Shin MK, Polotsky VY. Effects of different acute hypoxic regimens on tissue oxygen profiles and metabolic outcomes. J Appl Physiol 111: 881–890, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reinke C, Bevans-Fonti S, Grigoryev DN, Drager LF, Myers AC, Wise RA, Schwartz AR, Mitzner W, Polotsky VY. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces lung growth in adult mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L266–L273, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ribeiro MJ, Sacramento JF, Gonzalez C, Guarino MP, Monteiro EC, Conde SV. Carotid body denervation prevents the development of insulin resistance and hypertension induced by hypercaloric diets. Diabetes 62: 2905–2916, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Li J, Bevans S, Smith PL, Rodriguez A, Polotsky VY. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 1290–1297, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schramm LP, Adair JR, Stribling JM, Gray LP. Preganglionic innervation of the adrenal gland of the rat: a study using horseradish peroxidase. Exp Neurol 49: 540–553, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schramm LP, Chornoboy ES. Sympathetic activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats after spinal transection. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 243: R506–R511, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shin MK, Drager LF, Yao Q, Bevans-Fonti S, Yoo DY, Jun JC, Aja S, Bhanot S, Polotsky VY. Metabolic consequences of high-fat diet are attenuated by suppression of HIF-1alpha. PLos One 7: e46562, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silva AQ, Schreihofer AM. Altered sympathetic reflexes and vascular reactivity in rats after exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol 589: 1463–1476, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest 96: 1897–1904, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Svenson KL, Von SR, Magnani PA, Suetin HR, Paigen B, Naggert JK, Li R, Churchill GA, Peters LL. Multiple trait measurements in 43 inbred mouse strains capture the phenotypic diversity characteristic of human populations. J Appl Physiol (1985) 102: 2369–2378, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thompson RJ, Jackson A, Nurse CA. Developmental loss of hypoxic chemosensitivity in rat adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. J Physiol 498: 503–510, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Unger RH, Clark GO, Scherer PE, Orci L. Lipid homeostasis, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801: 209–214, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.varez-Buylla R, varez-Buylla E, Mendoza H, Montero SA, varez-Buylla A. Pituitary and adrenals are required for hyperglycemic reflex initiated by stimulation of CBR with cyanide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R392–R399, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vieira E, Liu YJ, Gylfe E. Involvement of alpha1 and beta-adrenoceptors in adrenaline stimulation of the glucagon-secreting mouse alpha-cell. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 369: 179–183, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weinstock TG, Wang X, Rueschman M, Ismail-Beigi F, Aylor J, Babineau DC, Mehra R, Redline S. A controlled trial of CPAP therapy on metabolic control in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and sleep apnea. Sleep 35: 617B–625B, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med 353: 2034–2041, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, Szklo-Coxe M, Austin D, Nieto FJ, Stubbs R, Hla KM. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep 31: 1071–1078, 2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ziegler MG, Elayan H, Milic M, Sun P, Gharaibeh M. Epinephrine and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 14: 1–7, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]