Abstract

Cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (IR) leads to myocardial dysfunction by increasing production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mitochondrial H+ leak decreases ROS formation; it has been postulated that increasing H+ leak may be a mechanism of decreasing ROS production after IR. Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) decreases ROS formation after IR, but the mechanism is unknown. We hypothesize that pharmacologically increasing mitochondrial H+ leak would decrease ROS production after IR. We further hypothesize that IPC would be associated with an increase in the rate of H+ leak. Isolated male Sprague-Dawley rat hearts were subjected to either control or IPC. Mitochondria were isolated at end equilibration, end ischemia, and end reperfusion. Mitochondrial membrane potential (mΔΨ) was measured using a tetraphenylphosphonium electrode. Mitochondrial uncoupling was achieved by adding increasing concentrations of FCCP. Mitochondrial ROS production was measured by fluorometry using Amplex-Red. Pyridine dinucleotide levels were measured using HPLC. Before IR, increasing H+ leak decreased mitochondrial ROS production. After IR, ROS production was not affected by increasing H+ leak. H+ leak increased at end ischemia in control mitochondria. IPC mitochondria showed no change in the rate of H+ leak throughout IR. NADPH levels decreased after IR in both IPC and control mitochondria while NADH increased. Pharmacologically, increasing H+ leak is not a method of decreasing ROS production after IR. Replenishing the NADPH pool may be a means of scavenging the excess ROS thereby attenuating oxidative damage after IR.

Keywords: mitochondria, proton leak, ischemia-reperfusion, reactive oxygen species, uncoupling

cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (IR) leads to the formation of increased amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide radical (O2·−), hydroxyl radical (OH·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (16, 22, 24, 25). The formation of these products leads to deleterious effects such as lipid peroxidation, leading to cell membrane breakdown and cell swelling, myocardial stunning, increased incidence of postischemic arrhythmias, and myocyte death by apoptosis (9, 16, 24). Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) is the phenomenon whereby brief episodes of IR before a prolonged episode of IR lead to preservation of myocardial contractile function and other protective effects on myocardium (for review, see Ref. 16). One of the effects of IPC is a reduction in the production of ROS, leading to the hypothesis that part of the protective mechanism of IPC is to attenuate ROS formation (16). A significant body of work has focused on the reduction of ROS formation as a mechanism of improving outcomes after myocardial IR (6, 9, 15, 16).

Mitochondria have been identified as a major source of ROS production during ischemia-reperfusion (16, 22, 24, 25). Complex I and III of the electron transport chain (ETC) are the primary mitochondrial sources of ROS, with complex III being the predominant producer (16).

Mitochondrial proton (H+) leak is the reentry of protons into the mitochondrial matrix independent of the ATP synthase (17, 20); this leads to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (mΔΨ). It is a form of mitochondrial uncoupling that has previously been shown to decrease the production of mitochondrial ROS (12, 21). Studies have also shown that increased reactive oxygen species production leads to the activation of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins, which further increase H+ leak and act as a negative feedback mechanism to decrease the production of ROS (5). These findings have led to the prevailing theory that mitochondrial uncoupling may be a mechanism of limiting ROS production in the setting of myocardial IR injury. Not all ROS production is mΔΨ dependent since maximal reduction of mΔΨ is associated with low rates of continued ROS formation (21).

Innate mechanisms for combating increased oxidative stress include the NADP/NADPH pool. NADPH has many functions, including acting as a reducing agent for oxidized glutathione and thioredoxin to replenish the reduced glutathione (GSH) and reduced thioredoxin (Trx-SH) pools. Both glutathione and Trx-SH are involved in H2O2 scavenging and previous studies have shown that inhibition of these pathways leads to the accumulation of ROS in isolated mitochondria (1).

We therefore designed these experiments to measure 1) the rate of mitochondrial H+ leak before and after an episode of myocardial IR; 2) the changes in mitochondrial ROS production associated with pharmacologically manipulating H+ leak; and 3) the changes in the concentrations of the nucleotides NAD+, NADH, NADP, and NADPH during IR. We demonstrated that H+ leak decreases mitochondrial ROS production, but only before the induction of IR. After IR, mitochondrial ROS production is unresponsive to increases in H+ leak. There is also a significant decrease in the concentration of NADPH after IR. The changes observed in the concentration of the reducing agent NADPH would indicate a significant shift in the redox potential of cardiac mitochondria during IR. These findings have implications for therapeutic interventions. Limiting ROS production by mitochondrial uncoupling may not produce beneficial results; however, replenishing the NADPH pool may provide mitochondria with a means of scavenging the excess ROS thereby attenuating oxidative damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolated heart preparation.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (275–300 g) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg ip) and heparinized (heparin sodium, 500 U ip). Hearts were excised quickly and arrested in cold Krebs-Henseleit solution. Hearts were then perfused in a nonrecirculating Langendorff apparatus at 37°C with Krebs-Henseleit buffer consisting of (in mM) 118 NaCl, 4.6 KCl, 1.17 KH2PO4, 1.17 MgSO4, 1.16 CaCl2, 23 NaHCO3, and 5.3 glucose, pH 7.4, and equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 gas. Left ventricular rate pressure product (RPP; peak systolic pressure minus end-diastolic pressure multiplied by heart rate) was recorded using an intraventricular latex balloon connected to a pressure transducer (4). Coronary flow was measured using a TS410 transmit time tubing flowmeter (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Data were continuously recorded using a PowerLab Chart v4.2 (AD Instruments, Milford, MA).

Rats were acclimated in a quiet environment and fed a standard diet for 14 days before the experiments. They were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources of the National Research Council (17a). Experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Ohio State University.

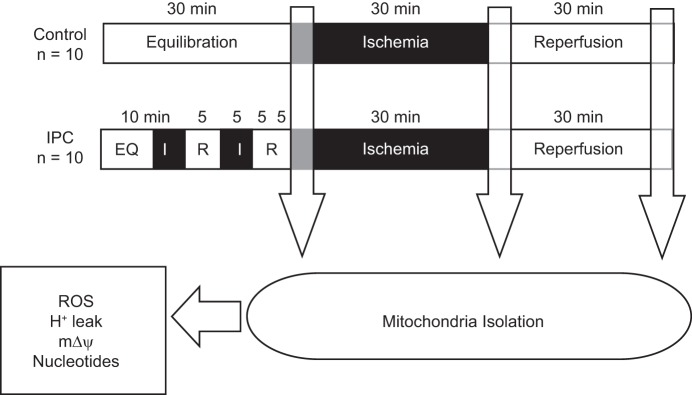

IPC protocol.

Hearts were assigned to Control and IPC. The Control group (n = 10) was subjected to 30 min of equilibration (EQ), 30 min of global normothermic ischemia, and 30 min of reperfusion (RP). The IPC group (n = 10) was subjected to 10 min of EQ, then ischemic preconditioning was induced by two 5-min episodes of ischemia, each followed by 5 min of reperfusion, then 30 min of global normothermic ischemia, and 30 min of reperfusion (Fig. 1). Ischemia was achieved by a stopcock located directly above the aorta. Hearts were immersed at all times in a water jacketed nongassed perfusate bath to maintain normothermia (37°C).

Fig. 1.

Protocol for ischemia-reperfusion (IR). The Control group was subjected to 30 min of equilibration (EQ), 30 min of global normothermic ischemia, and 30 min of reperfusion (RP). The ischemic preconditioning (IPC) group was subjected to 10 min of EQ, then IPC was induced by 2 5-min episodes of ischemia (I5), each followed by 5 min of reperfusion (R5), then 30 min of global normothermic ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion. Mitochondria were then isolated, and measurements of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, mΔΨ, H+ leak, and nucleotide levels were carried out as described. N = 10/group at each collection point (End EQ, End I, and End RP).

Isolation of subsarcolemmal mitochondria.

Subsarcolemmal (SS) mitochondria were isolated at end equilibration (end EQ), end Ischemia (End I), and end reperfusion (End RP) by differential centrifugation according to Palmer et al. (18). Briefly, hearts were minced in the isolation buffer (MSH) containing (in mmol/l) 230 mannitol, 70 sucrose, and 3 HEPES, pH 7.4 at 4°C, with the addition of 0.2% BSA and 1 mM EGTA and homogenized with a polytron tissue processor (Brinkman Instruments, Westbury, NY) for 3 s at a rheostat setting of 6.5. Further homogenization was performed with a glass homogenizer (Kontes Glass, Vineland, NJ). The polytron homogenate was centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 5,000 g for 10 min for isolation of SS mitochondria. Subsequent pellets were washed twice at 5,000 g for 10 min each with MSH buffer and, finally, suspended in 0.5 ml of MSH buffer with 0.2% BSA and 1 mM EGTA. Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method (19).

Mitochondrial membrane potential.

mΔΨ was measured using a tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP+) electrode as described by Kamo et al. (8). The electrode was calibrated before the start of each experiment using a total of 2.8 μM tetraphenylphosphonium chloride (TPPCl). mΔΨ was calculated from the Nernst equation using the TPP binding correction factor (2, 8, 13, 22). The Nernst constant was at 37°C = 61.540, and TPP external is estimated from a standard curve of [TPP+] using 0.33 μM TPPCl additions to a total concentration of 4 μM. The TPP+ binding correction factor used was 0.16. The incubation media contained (in mmol/l) 100 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, and 50 HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Succinate (5 mM) was used as substrate for complex II. Rotenone (4.15 μM) was used to inhibit backflow of electrons to complex I. Mitochondrial uncoupling was achieved by adding increasing concentrations of carbonyl cyanide p-(tri-fluromethoxy)phenyl-hydrazone (FCCP, 0–80 nM).

Respiration and H ± leak.

Mitochondrial respiration was measured by the polarographic method of Chance and Williams using a Clark oxygen electrode (3). The incubation media contained (in mmol/l) 100 KCl and 50 HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Succinate (5 mM) was used as substrate for complex II. Rotenone (4.15 μM) was used to inhibit backflow to complex I. ATP synthase was inhibited with oligomycin-A (1.67 μM) to measure proton leak. Mitochondria (∼0.5 mg of protein) were added last to initiate state 2 respiration. H+ leak was measured as the state 2 respiration rate required to maintain mΔΨ at −150 mV.

Complex III ROS production.

Complex III H2O2 production was measured using Amplex-red. In a polystyrene cuvette containing 3 ml of buffer solution of (in mM) 100 KCl and 50 HEPES, 0.01 horseradish peroxidase, and 5 succinate and 4.15 μM rotenone, 3 μM KPi, 50 μM Amplex-Red, and 1.67 μM oligomycin-A were added followed finally by mitochondria (∼0.05 mg of protein). Fluorescence was recorded for 5 min at excitation 560 nm and emission 583 nm at 37°C. The slope of the fluorescence curve of each sample was used to measure the rate of H2O2 formation by inputting the measured slope into the formula for a standard curve. The standard curve was obtained by adding known concentrations of H2O2 to buffer solution containing horseradish peroxidase and Amplex-Red.

Pyridine nucleotide levels by HPLC.

Pyridine nucleotide levels were measured by HPLC using a modified protocol described by Klaidman et al. (10). Briefly, mitochondria were isolated as described above and resuspended in 400 ml of MSH buffer with 0.2% BSA and 1 mM EGTA. Reaction buffer (500 ml) contained 0.2 M KCN, 0.06 M KOH, and 0.01 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. Samples were then sonicated for 0.5 s three times using a Microson XL sonicator (Colonial Scientific, Richmond, VA). Chloroform (1 ml) was then added to each sample and centrifuged for 5 min in an Eppendorf 5415 D centrifuge (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) at 1,400 rpm at 4°C. The aqueous layer was then extracted and resuspended in 1 ml chloroform and centrifuged at 1,400 rpm; this was repeated a third time. At the end of the third spin, the aqueous layer was extracted and placed in a 0.5 ml Microcon centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C. The filtrate was then extracted and kept frozen in liquid nitrogen until time of analysis. Before injection, 20 μl of the liquid sample was mixed in a 1:5 ratio with the mobile phase solution (96% 0.2 M ammonium acetate and 4% methanol). This sample (20 μl) was then injected into an ESA CoulArray 5600A HPLC system (Dionex, Chelmsford, MA) and ESA CWAcquire software. Fluorescence was detected by a Hitachi L-2485 fluorescence detector (ex. 330, em. 460) (Hitachi High-Technologies America, Pleasanton CA) and UV absorbance by an ESA model 520 UV/VIS absorbance detector (Dionex, Chelmsford, MA). The mobile phase consisted of 0.2 M ammonium acetate at a pH of 6.0 and HPLC grade methanol. An HPLC gradient time program was used; pumps were set at flow rate of 1 ml/min. The pumps were initially set at 96% ammonium acetate and 4% MeOH, at 26 min MeOH increased to 9%, then 20% at 30 min and back to 4% at 43 min. Total run time was 45 min. The column used was a TSKgel ODS-80Tm 4.6 × 250 mm C-18 column (TOSOH Bioscience, King of Prussia, PA).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test were used to compare differences between pairs; two-way ANOVA and the Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis was used to compare multiple groups. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Materials.

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Rats were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN).

RESULTS

Complex III ROS production.

At End EQ, complex III ROS production was slightly higher in IPC mitochondria compared with Control (Fig. 2). At End I there is a significant increase in ROS production with a larger increase in Control compared with IPC mitochondria. A similar result is seen at End RP.

Fig. 2.

Reactive oxygen species production during IR in Control and IPC mitochondria. At End EQ, there was slightly higher ROS production seen in IPC mitochondria, which may be attributed the two brief episodes of IR used to induce preconditioning; this did not reach statistical significance. At End I there is a significant increase in ROS production in Control mitochondria, which persists through End RP. IPC mitochondria have attenuated ROS production compared with Control. The incubation media contained (in mmol/l) 100 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 50 HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Succinate (5 mM) was used as substrate for complex II. Rotenone (4.15 μM) was used to inhibit backflow of electrons to complex I; ADP was not added to the medium. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at End EQ; §P < 0.05 vs. Control at same end point; n = 8/group.

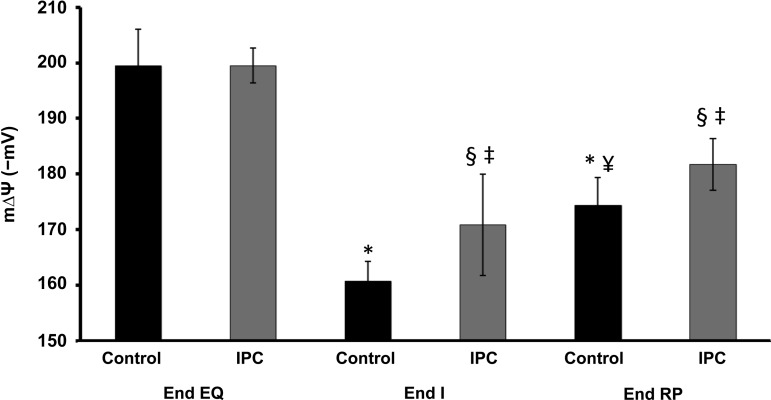

Mitochondrial membrane potential.

mΔΨ was similar in the two groups at End EQ (Fig. 3). At End I, there was significant decline in mΔΨ with Control having the greater decrease. At End RP there is partial recovery of mΔΨ, with IPC having a greater recovery than Control.

Fig. 3.

Changes in membrane potential (mΔΨ) during IR. Both Control and IPC mitochondria have similar starting mΔΨ at End EQ. IR leads to the loss of mΔΨ (depolarization) in both groups but is more pronounced in Control mitochondria. IPC leads to preservation of mΔΨ at End I and End RP compared with Control. The incubation media contained (in mmol/l) 100 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, and 50 HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Succinate (5 mM) was used as substrate for complex II. Rotenone (4.15 μM) was used to inhibit backflow of electrons to complex I. Mitochondrial uncoupling was achieved by adding increasing concentrations of carbonyl cyanide p-(tri-fluromethoxy)phenyl-hydrazone (FCCP; 0–80 nM). *P < 0.05 vs. Control at End EQ; ¥P < 0.05 vs. Control at End I; §P < 0.05 vs. IPC at End EQ; ‡P < 0.05 vs. Control at same endpoint; n = 10/group.

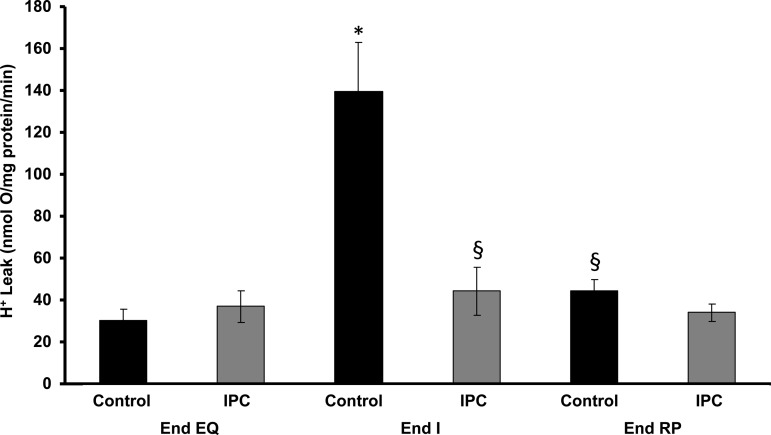

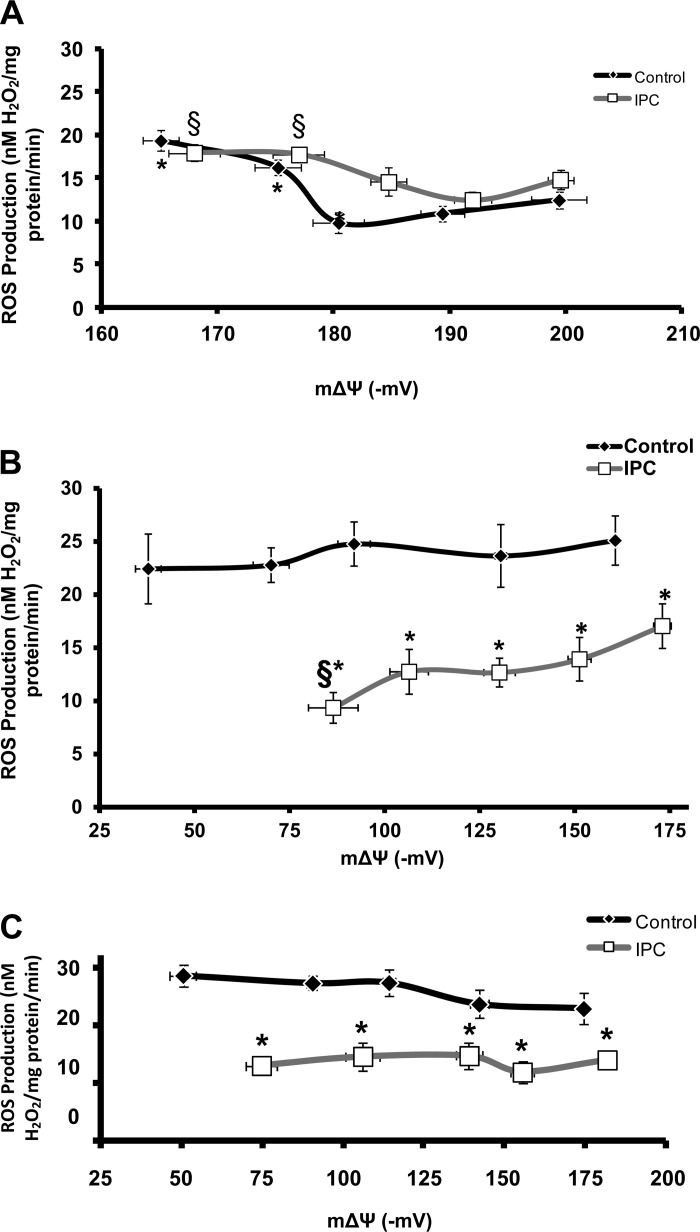

H ± leak and ROS production.

Baseline H+ leak was equal in both groups at End EQ. At End I, H+ leak increased in Control mitochondria but was unchanged in IPC. At End RP, H+ leak returned to near baseline in both groups (Fig. 4). Pharmacologically increasing H+ leak by the addition of increasing concentrations of FCCP led to decreasing mΔΨ (Fig. 5, A and B). At End EQ, this decrease in mΔΨ was accompanied by an initial decrease in ROS production in both Control and IPC mitochondria (Fig. 5A). The nadir of ROS production came at a higher mΔΨ and lower FCCP concentration in IPC mitochondria compared with Control. Continued increases in H+ leak led to an increase in ROS production above baseline levels in both groups (Fig. 5A). At End RP, there is a continued decreased in mΔΨ, but there is no significant response in ROS production to increasing H+ leak in both Control and IPC mitochondria (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial proton (H+) leak during IR. H+ leak is measured as the state 2 respiration rate required to maintain mΔΨ at −150 mV. There is a significant increase in H+ leak for Control mitochondria at End I, which returns to near baseline at End RP. IPC mitochondria show no significant change in H+ leak throughout IR. The incubation media contained (in mmol/l) 100 KCl and 50 HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Succinate (5 mM) was used as substrate for complex II. Rotenone (4.15 μM) was used to inhibit backflow to complex I. ATP synthase was inhibited with oligomycin-A (1.67 μM) to measure proton leak. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at End EQ; §P < 0.05 vs. Control at End I; n = 6/group.

Fig. 5.

ROS production as a function of increasing H+ leak at end equilibration (A), end ischemia (B), and end reperfusion (C). Increasing H+ leak is reflected as decreasing mΔΨ. The incubation media contained (in mmol/l) 100 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, and 50 HEPES, pH 7.4, at 37°C. Succinate (5 mM) was used as substrate for complex II. Rotenone (4.15 μM) was used to inhibit backflow of electrons to complex I. Mitochondrial uncoupling was achieved by adding increasing concentrations of FCCP (0–80 nM). A: at End EQ, increasing H+ leak leads to decreasing mΔΨ and an initial decrease in ROS production in Control mitochondria. Higher rates of H+ leak increase ROS production above baseline levels. A similar effect is seen in IPC mitochondria; however, the nadir of ROS production occurs at a lower rate of H+ leak and higher mΔΨ. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at mΔΨ of −199 mV; §P < 0.05 vs. IPC at mΔΨ of −192 mV; n = 10/group. B: at End I, both IPC and Control mitochondria have a lower starting mΔΨ compared with End EQ. Increasing H+ leak does lead to a slight decrease in ROS production in IPC mitochondria, which is not seen in Control; however, this occurs at a mΔΨ, which is below the physiologic range of function. IPC has a lower rate of ROS production at all levels of mΔΨ compared with Control. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; §P < 0.05 vs. IPC at −175 mV. C: at End RP, both IPC and Control mitochondria have a lower starting mΔΨ; also increasing H+ leak has no effect on ROS production. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at same concentration of FCCP, which was used to induce H+ leak.

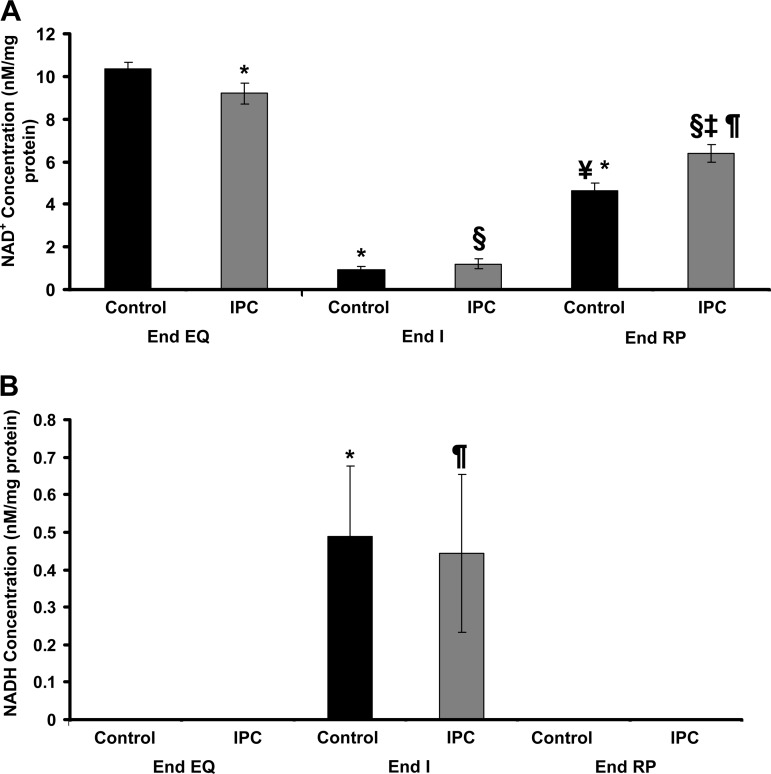

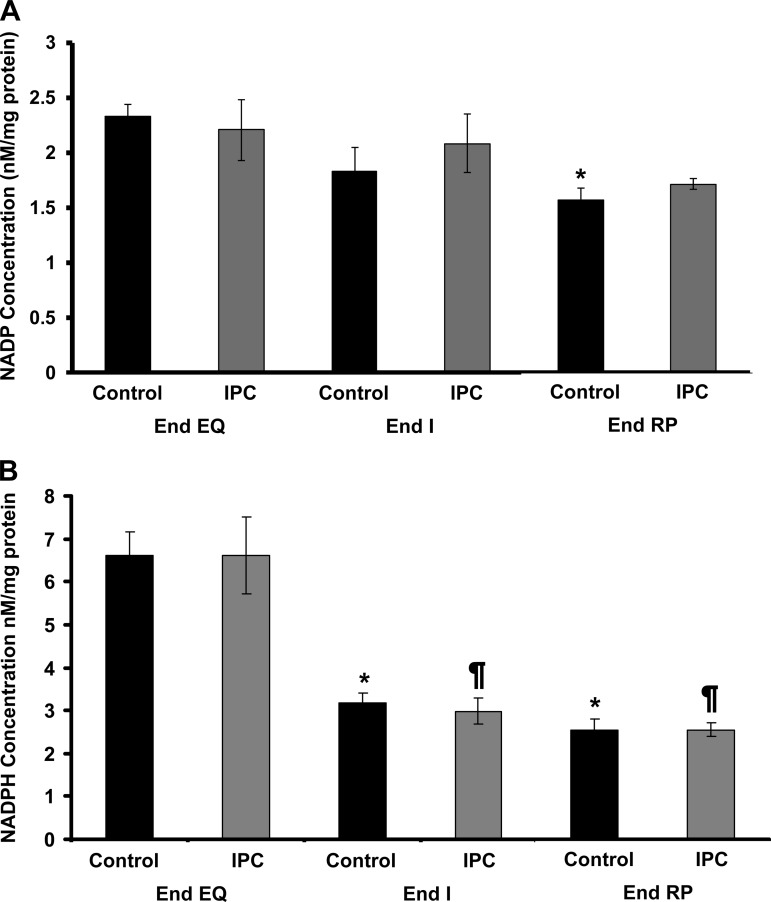

Pyridine nucleotide levels throughout IR.

The concentrations of NAD+, NADP, and NADPH were similar in Control and IPC mitochondria at End EQ (Figs. 6A and 7, A and B). It is notable that the concentration of NADH is undetectable in both groups at End EQ (Fig. 6B). The concentration of NAD+ is slightly lower in the IPC group at End EQ. This is most likely due to the brief episodes of ischemia that are used in the preconditioning protocol. At End I, there is a dramatic decline in NAD+, which is associated with an increase in NADH that becomes detectable. This is true for both IPC and Control mitochondria. There is also a significant decline in the concentration of NADPH in both Control and IPC mitochondria at End I, with no significant recovery at End RP (Fig. 7B). At End RP, there is partial recovery of NAD+ concentrations, with IPC having slightly higher levels than Control. NADH concentrations were once again undetectable, whereas NADPH levels remained low, similar to the observed concentrations at End I. NADP concentration showed no significant change for IPC mitochondria; NADP concentrations in Control mitochondria were slightly decreased at End RP, but this change was not significant.

Fig. 6.

Changes in NAD+ and NADH concentrations throughout IR using HPLC. A: NAD+ concentrations are slightly lower in IPC mitochondria at End EQ. At End I, both IPC and Control have significantly decreased levels of NAD+. At End RP, there is recovery in both IPC and Control mitochondria, although not to the same levels seen at End EQ; IPC also had greater recovery compared with Control. *P < 0.001 vs. Control at End EQ; ¥P < 0.001 vs. Control at End I; §P < 0.001 vs. IPC at End EQ; ‡P < 0.001 vs. IPC at End I; ¶P < 0.01 vs. Control at End RP. B: NADH is undetectable at End EQ in IPC and Control mitochondria. At End I, there is a significant increase in the concentration of NADH, which returns to baseline levels at End RP. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at End EQ and End RP; ¶P < 0.05 vs. IPC at End EQ and End RP.

Fig. 7.

Changes in NADP and NADPH concentrations throughout IR using HPLC. A: NADP concentrations in Control mitochondria are slightly decreased by End RP. IPC mitochondria also have decreasing concentrations of NADP; however, this does not reach significance. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at End EQ. B: NADPH concentrations are similar in IPC and Control mitochondria at End EQ but decrease significantly at End I and remain low through End RP. *P < 0.05 vs. Control at End EQ; ¶P < 0.05 vs. IPC at End EQ.

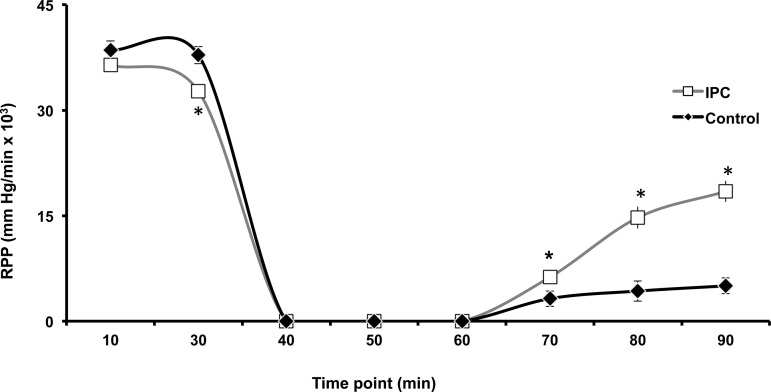

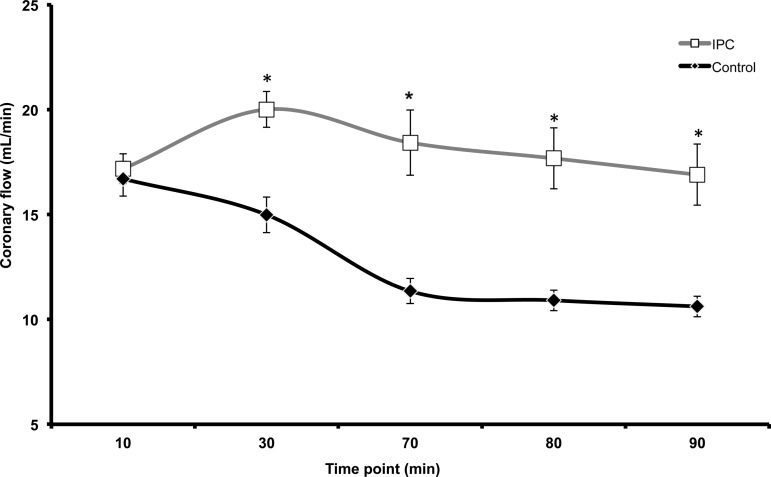

Mechanical function.

The RPP was recorded as a marker of mechanical function as described in the materials and methods section. At 10 min into equilibration, there is no significant difference in RPP for both IPC and Control mitochondria (Fig. 8). At End EQ there is a decline in RPP for the IPC group, likely due to the preconditioning protocol. Contractile function ceased in both groups at the onset of ischemia (30-min time point to 60-min time point). During reperfusion, IPC has a greater recovery of RPP compared with Control at all time points. Coronary flow was also measured throughout the experiment (Fig. 9). During equilibration (10-min time point), there is no difference in coronary flow between IPC and Control hearts. However, starting at the end of equilibration (30-min time point), there is a clear separation with IPC hearts showing a higher rate of coronary flow compared with Control. This persists through the entirety of reperfusion (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Rate pressure product (RPP) as measure of mechanical function. RPP (peak systolic pressure minus end-diastolic pressure multiplied by heart rate) was measured throughout IR using an intraventricular balloon connected to a pressure transducer. After 10 min of equilibration, there is no difference in RPP between IPC and Control hearts. At End EQ (30 min), RPP is lower in the IPC hearts, likely due to the preconditioning protocol. There is no measureable function during ischemia (30–60 min); however, throughout reperfusion, IPC hearts have a greater larger recovery of mechanical function compared with Control. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; n = 10/group.

Fig. 9.

Coronary flow was measured throughout IR. During equilibration (10-min mark) coronary flow is equal in both IPC and Control hearts. At End EQ (30 min), IPC hearts have a significantly higher rate of coronary flow compared with Control. During reperfusion (60–90 min), IPC continues to have a higher coronary flow compared with Control. *P < 0.05 vs. Control; n = 6/group.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of these experiment are 1) H+ leak increases during ischemia and returns to baseline at end reperfusion; 2) pharmacologically increasing H+ leak decreases mitochondrial ROS production before, but not after, an episode of IR; 3) IR causes depletion of the pyridine nucleotide NADPH, which is important in the antioxidant defense pathway of mitochondria; 4) IPC does not increase H+ leak during IR, therefore increasing H+ leak is not the mechanism responsible for decreased ROS production in IPC.

ROS production.

It is well established that IR leads to increased ROS production, particularly during reperfusion. This burst of ROS leads to increased arrhythmia formation, membrane damage, and decreased cardiac function. At End EQ, complex III ROS production was slightly higher in IPC mitochondria compared with Control (Fig. 2). This is consistent with our previously published findings (20) and is likely due to the effects of brief episodes of ischemia during the induction of IPC. At End I and End EQ there is an even greater increase in ROS production in Control mitochondria compared with IPC. It is well documented that the greatest increase in ROS production occurs during the initial few minutes after reperfusion and is partly responsible for the damaging effects of reperfusion injury (24 25). The current results confirm the sustained production of higher levels of ROS in nonpreconditioned mitochondria following the induction of reperfusion. Preconditioned mitochondria have lower ROS production compared with Control.

Effects of H ± leak on ROS production.

Previous studies have shown that increasing mitochondrial H+ leak leads to decreased ROS production and may have protective effects on cardiac function (12, 17, 21). Increased ROS production in isolated mitochondria may even activate mechanisms of H+ leak in an attempt to reduce the devastating effects of high levels of ROS (5). In the current experiments, it is shown that increased H+ leak does in fact decrease ROS production with a corresponding decrease in mΔΨ; however, after an episode of IR, increased H+ leak has no effect on mitochondrial ROS production. Figures 4 and 5A show that for mitochondria that have not undergone an episode of IR, minor increases in H+ leak (signified by decreasing mΔΨ) lead to decreased ROS production, whereas further increases in H+ leak have the opposite effect. In both Control and preconditioned mitochondria, IR leads to a change in the redox status of the mitochondria, causing them to have a lower starting mΔΨ (Fig. 3 and 5B). This lower mΔΨ is associated with a higher rate of ROS production, which is no longer responsive to further uncoupling (Fig. 5, A and B). There is also no further change in ROS production by increasing H+ leak, even to the point of mΔΨ collapse (Fig. 5B). Our findings are consistent with those of Starkov and Fiskum, who previously showed that not all ROS production is dependent on mΔΨ. In their experiments, maximal reduction of mΔΨ was still associated with continued formation of ROS (21).

Aon et al. (1) previously described the mitochondria as existing in an intermediate redox state, where energy production is maximized while ROS production is kept at a minimum. Extreme oxidation or reduction of the mitochondria leads to a net overflow of ROS production (1). The current results are in line with the findings of Aon et al. (1). These results indicate that in isolated mitochondria, minor increases in H+ leak cause a corresponding decrease in ROS production. However, after an episode of IR, increasing H+ leak has no effect on ROS production. Mitochondria that have been exposed to IR have a lower starting mΔΨ (Figs. 3 and 5B). This lower mΔΨ is a shift from the optimal redox state, and further increases in H+ leak do not lead to decreased ROS production. The change in redox state is confirmed by the significant decline in NADPH levels at End I, which remain low throughout reperfusion (Fig. 7B). This loss of antioxidant activity due to decreased NADPH is associated with increased ROS production as discussed in the section to follow.

To determine whether changes in H+ leak are associated with the lower ROS production seen in IPC, H+ leak was measured at all three phases of IR in both Control and IPC mitochondria. Figure 4 shows that there is no significant change in the rate of H+ leak in IPC mitochondria throughout IR. Control mitochondria have a larger increase in H+ leak at End I, but this returned to near baseline at End RP. This would lead us to conclude that the reduced rate of mitochondrial ROS production in IPC compared with Control is not due to increased H+ leak in the postischemic rat heart.

The role of NADH/NADPH in mitochondria.

The antioxidant capacity of mitochondria is closely related to NADPH levels. O2·− is the major ROS produced by mitochondria; this is then converted to H2O2 by the enzyme SOD (13). The glutathione peroxidase/glutathione reductase system and the thioredoxin peroxidase/thioredoxin reductase system convert H2O2 to H2O and O2, thereby eliminating the highly reactive oxidative products (13). Oxidized thioredoxin and glutathione are converted to their reduced forms through the oxidation of NADPH, which is converted to NADP in the process. Maintaining the concentration of NADPH is therefore critical to preserve the redox status of the mitochondria (13). NADP is reduced by the activity of the NADH/NADP transhydrogenase, which is powered by the flow of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The interaction among these systems demonstrates how the mΔΨ is linked to the redox capacity of the mitochondria (22). Inhibition of the ETC, as occurs during ischemia, leads to a buildup of electrons along the ETC, which facilitates electron leak from the ETC to O2. The single-electron reduction of O2 leads to the formation of O2·−; therefore, IR leads to a more reduced state of the ECT and increased ROS production (1, 13, 22). This is also demonstrated in the results of our experiment in Figs. 2 and 3, where IR leads to a decrease in mΔΨ and increased ROS production. Furthermore, the loss of mΔΨ leads to decreased flow of H+ across the NADH/NADP transhydrogenase, which diminishes the capability of the mitochondria to replenish NADPH during periods of oxidation (5). ROS balance is dependent on both the rate of production, which is increased after IR due to reduced state of the ETC, and the antioxidant capacity, which is attenuated due to decreased formation of NADPH (1, 13).

The results of our current experiments show that at End EQ (aerobic respiration), there is a relatively high concentration of NADPH and undetectable levels of NADH and a lower rate of ROS formation. At End I, there is an increase in ROS production with a corresponding decrease in NADPH levels and increased NADH. NADH is the key electron donor during oxidative phosphorylation (1); therefore, inhibition of the ETC leads to accumulation of NADH (Figs. 6B and 8). The decrease in NADPH is likely multifactorial reflecting decreased production due to loss of mΔΨ, which leads to decreased NADH/NADP transhydrogenase activity, as well as increased oxidation of NADPH due to increased ROS production (13). The role of these agents in maintaining the redox balance of the mitochondria cannot be overstated.

Understanding the mechanism of the preservation of mΔΨ and how to limit ROS production during IR is of clinical importance in the development of future therapeutic options as demonstrated by Kloner et al. (11). This group used Bendavia, an analog of a class of peptides that crosses the cell membrane and is concentrated within the mitochondria, to show that reduction in ROS production after IR was accompanied by preservation of mΔΨ and reduction of oxidant related cell death during reperfusion in several animal models (11). The targeting of mitochondria, where a significant increase in ROS production occurs, may lead to the development of more specific and effective treatments.

One potential discrepancy in our results is the decreased NADPH concentrations at End I and End RP with no corresponding increases in NADP concentrations. As detailed by Klaidman et al. (10), the ultrasensitive HPLC method used for the extraction of the pyridine dinucleotides produces a stable product due to the addition of cyanide at the 4 position of the nicotinamide ring. This produces NAD-CN and NADP-CN, which are stable, strongly fluorescent products (10). There two peaks for the NADP product, NADP-CN1 and NADP-CN2, each separating at different times along on the HPLC column used. The NADP-CN2 product tends to overlap with either the NAD-CN1 peak or the NADH peak, depending on the column, and adjusting the pH will either decrease or increase the retention time of the NADP-CN2 product (for details, see Ref. 10). For this experiment, a pH of 6.0 resulted in the highest reproducibility and detection of standard products. Although NAD-CN1 and NADH have a stable retention time with adjustments in pH, decreasing the pH closer to 5.9 will decrease the retention of NADP-CN2 (10). This could lead to small peaks, which were difficult to distinguish from artifact, leading to falsely apparent lower concentration of NADP due to unmeasured NADP-CN2. It is less likely that the NADP-CN2 peak was buried in the NAD-CN1 given the significant decrease in NAD with corresponding rise in NADH observed (Fig. 6B).

Conclusions

Increased ROS production after cardiac IR injury leads to loss of mΔΨ and decreased antioxidant capacity of mitochondria. IPC mitigates the effects of IR and leads to improved cardiac function after an episode of IR. Although the exact mechanism of IPC remains unknown, it has been shown that IPC is associated with a significantly decreased level of ROS production. Increased H+ leak has been shown to reduce the production of ROS, and it was proposed that this may be a mechanism for the decreased ROS formation seen in IPC mitochondria. Our experiments confirm that increased H+ leak does lead to decreased ROS production, but only in normal mitochondria, not in mitochondria that have undergone an episode of IR. The induction of IR leads to a change in the redox status of the mitochondria to a more reduced form with a lower starting mΔΨ due to inhibition of the ETC and higher ROS formation due to decreased antioxidant capacity. Further increases in H+ leak at this point have no effect on reducing the formation of ROS. We also demonstrate that the rate of H+ in preconditioned mitochondria does not change throughout an episode of IR; therefore, increased H+ leak is not the mechanism responsible for decreased ROS production in IPC mitochondria. The increased ROS production seen during reperfusion could potentially be alleviated by replenishing the antioxidant capacity of mitochondria, specifically NADPH.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-38324, HL-63744, and HL-65608 and by an American College of Surgeons Faculty Research Fellowship and a Thoracic Surgery Foundation for Research and Education Research Grant.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.Q., W.E., D.R.P., J.L.Z., and J.C. conception and design of research; R.Q. and D.S.L. performed experiments; R.Q., D.S.L., L.R., W.E., D.R.P., J.L.Z., and J.C. analyzed data; R.Q., D.S.L., L.R., W.E., D.R.P., J.L.Z., and J.C. interpreted results of experiments; R.Q. and D.S.L. prepared figures; R.Q. and D.S.L. drafted manuscript; R.Q. and J.C. edited and revised manuscript; R.Q. and J.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lawrence J. Durhan for technical guidance in completing the fluorometry and liquid chromatography portion of this experiment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O′Rourke B. Redox-optimized ROS balance: a unifying hypothesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 865–877, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barger JL, Brand MD, Barnes BM, Boyer BB. Tissue-specific depression of mitochondrial proton leak and substrate oxidation in hibernating arctic ground squirrels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R1306–R1313, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chance B, Williams GR. The respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. Adv Enzymol 17: 65, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crestanello JA, Doliba NM, Babsky AM, Doliba NM, Niibori K, Whitman JRG, Osbakken MD. Ischemic preconditioning improves mitochondrial tolerance to experimental calcium overload. J Surg Res 103: 243–251, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Echtay KS, Roussel D, Jekabsons MB, Cadenas S, Stuart JA, Harper JA, Roebuck SJ, Morrison A, Pickering S, Clapham J, Brand MD. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature 15: 96–99, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flaherty JT, Pitt B, Gruber JW, Heuser RR, Rothbaum DA, Burwell LR, George BS, Kereiakes DJ, Deitchman D, Gustafson N, Brinker JA, Becker LC, Mancini GBJ, Topol E, Werns SW. Recombinant human superoxide dismutase (h-SOD) fails to improve recovery of ventricular function in patients undergoing coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 89: 1982–1991, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamo N, Muratsugu M, Hongoh R, Kobatake Y. Membrane potential of mitochondria measured with an electrode sensitive to tetraphenyl phosphonium and relationship between proton electrochemical potential and phosphorylation potential in steady state. J Membr Biol 49: 105–121, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JS, Jin Y, Lemasters JJ. Reactive oxygen species, but not Ca2+ overloading, trigger pH- and mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent death of adult rat myocytes after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2024–H2034, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klaidman LK, Leung AC, Adams JD., Jr High performance liquid chromatography analysis of oxidized and reduced pyridine dinucleotides in specific brain regions. Anal Biochem 22: 312–317, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kloner RA, Hale SL, Dai W, Gorman RC, Shuto T, Koolmansingh KJ, Gorman JH, III, Sloan RC, Frasier CR, Watson CA, Bostian PA, Kypson AP, Brown DA. Reduction of ischemia/reperfusion injury with Bendavia, a mitochondria-targeting cytoprotective peptide. J Am Heart Assoc 1: e001644, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korshunov SS, Skulachev VP, Starkov AA. High protonic potential actuates a mechanism of production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. FEBS Lett 416: 15–18, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza-Pinto NC, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 47: 333–343, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcinkeviciute A, Mildaziene V, Crumm S, Demin O, Hoek JB, Kholodenko B. Kinetics and control of oxidative phosphorylation in rat liver mitochondria after chronic ethanol feeding. Biochem J 349: 519–526, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murohara Y, Yui Y, Hattori R, Kawai C. Effects of superoxide dismutase on reperfusion arrhythmias and left ventricular function in patients undergoing thrombolysis for anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 67: 765–767, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev 88: 581–609, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nadtochiy SM, Tompkins AJ, Brookes PS. Different mechanisms of mitochondrial proton leak in ischaemia/reperfusion injury and preconditioning: implications for pathology and cardioprotection. Biochem J 395: 611–618, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.National Research Council (US) Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC: Natl Acad Press, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer JW, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Biochemical properties of subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondria isolated from rat cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem 252: 8731–8739, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson GL. Determination of total protein. Methods Enzymol 91: 95, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quarrie R, Cramer BM, Lee DS, Steinbaugh GE, Erdahl W, Pfeiffer DR, Zweier JL, Crestanello JA. Ischemic preconditioning decreases mitochondrial proton leak and reactive oxygen species production in the postischemic heart. J Surg Res 165: 5–14, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starkov AA, Fiskum G. Regulation of brain mitochondrial H2O2 production by membrane potential and NAD(P)H redox state. J Neurochem 86: 1101–1107, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 552: 335–344, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whipps DE, Halestrap AP. Rat liver mitochondria prepared in mannitol media demonstrate increased mitochondrial volumes compared with mitochondria prepared in sucrose media. Relationship to the effect of glucagon on mitochondrial function. Biochem J 221: 147–152, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu X, Zuo L, Cardounel AJ, Zweier JL, He G. Characterization of in vivo tissue redox statuts, oxygenation, and formation of reactive oxygen species in postischemic myocardium. Antiox Redox Signal 9: 447–455, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zweier JL, Flaherty JT, Weisfeldt ML. Direct measurement of free radical generation following reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 1404–1407, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]