Abstract

Background

The clinical and etiological relation between autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia is unclear. The degree to which these disorders share a basis in etiology has important implications for clinicians, researchers, and those affected. Our objective was to determine if a family history of schizophrenia and/or bipolar disorder was a risk factor for ASD. We conducted a case-control evaluation of histories of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives of probands in three samples, population registers in Sweden, Stockholm County, and Israel. Probands met criteria for ASD, and affection status of parents and siblings for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were established.

Findings

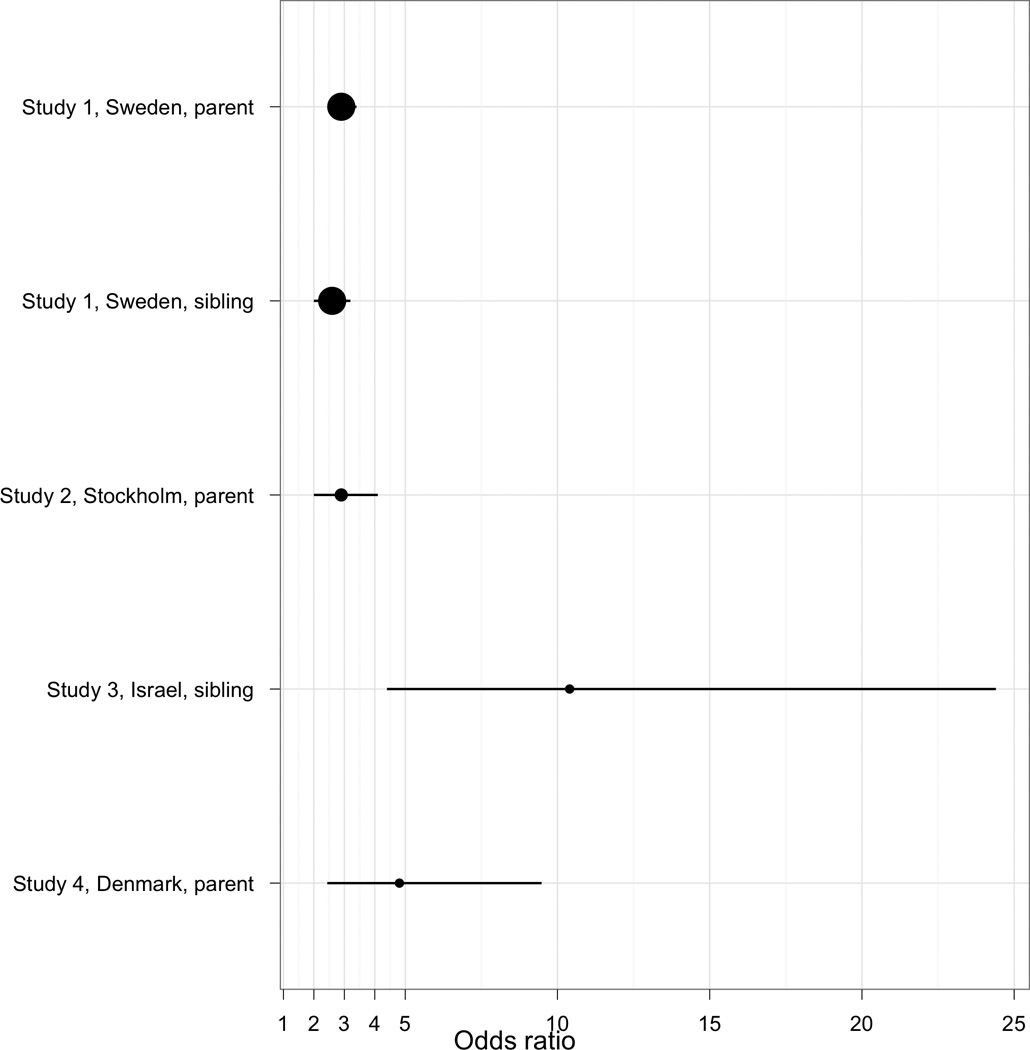

The presence of schizophrenia in parents was associated with an increased risk for ASD in a Swedish national cohort (odds ratio 2.9, 95% CI 2.5–3.4) and in a Stockholm County cohort (odds ratio 2.9, 95% CI 2.0–4.1). Similarly, schizophrenia in a sibling was associated with an increased risk for ASD in a Swedish national cohort (odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI 2.0–3.2) and in an Israeli conscription cohort (odds ratio 12.1, 95% CI 4.5–32). Bipolar disorder showed a similar pattern of associations but of lesser magnitude.

Interpretation

Findings from these three registers along with consistent findings from a similar study in Denmark suggest that ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder share common etiological factors.

Funding

Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, the Swedish Research Council, and the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, family history, genetics, risk factor, exposure, genetic epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia are currently considered as distinctive and infrequently overlapping 1, 2. Historically, ASD was often regarded as childhood schizophrenia as the impaired social interactions and bizarre behavior found in ASD were reminiscent of symptoms of schizophrenia 3. Indeed, the psychiatrist who coined the term schizophrenia counted “autism” (an active turning away from the external world) as an important distinguishing feature of schizophrenia 4, 5. Around 1980, the nosological status of ASD and schizophrenia was revised so that these disorders were separated 6. The separation was strongly influenced by developmental trajectory, and delineated infantile autism present from very early in life 7 from schizophrenia where psychotic symptoms developed after an extended period of normal or near-normal development.

Several lines of evidence suggest that this distinction is not absolute, and that there are important overlaps between ASD and schizophrenia. Some family history studies 8, 9 (although not all) 10 found that the relatives of probands with ASD were more likely to have a history of schizophrenia. However, these studies tended to be small and relatively underpowered. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is a rare subtype, and a sizable fraction have premorbid ASD 11. More directly, genome-wide copy number variation studies have identified rare mutations that are strong risk factors for both ASD and schizophrenia (e.g., 15q13.3, 16p11.2, 22q11.21, and in neurexin 1) 12–15. These points of overlap are quite uncommon, and apply to only a fraction of clinical samples.

The degree to which ASD and schizophrenia share etiological factors has important implications for clinicians, researchers, and those affected by these diseases. Therefore, we investigated if a family history of schizophrenia and/or bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives was a risk factor for ASD. Bipolar disorder was included given its etiological and clinical overlap with schizophrenia 16, 17. We conducted parallel analyses in three samples to evaluate the consistency and generalizability of the findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The overall goal of this study was to evaluate the impact of the “exposure” of family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (psychotic disorders) on the outcome of ASD. This relation was evaluated in three complementary samples. Study 1 has Swedish national coverage of inpatient and outpatient admissions. Study 2 is based on an inclusive set of primarily outpatient ASD treatment facilities but limited to the largest population center in Sweden (Stockholm County). Study 3 employs standardized psychiatric assessment of conscripts in Israel. ASD outcomes were assessed using register data, and exposures measured using register data on parents (Studies 1 and 2) or siblings (Studies 1 and 3). These studies were approved by research ethics committees at Karolinska Institutet and Sheba Medical Center.

Study 1 (Sweden National Patient Register, NPR) was conducted using Swedish national registers. An analysis of 27% of these cases was published previously 8. The primary key for register linkage was the unique personal identification number assigned to each Swedish citizen at birth or upon arrival in Sweden for immigrants 18. The NPR 19, 20 contains discharge diagnoses for all inpatient (since 1973) and outpatient (since 2001) psychiatric treatment in Sweden including admissions for assessment or treatment to any psychiatric or general medical hospital (including forensic psychiatric hospitals and the few private providers of inpatient healthcare). Biological relationships were established using the Multi-Generation Register 21 which identifies the relatives of an index person through linkage of a child to his or her parents, and includes all individuals born in Sweden since 1932, those registered as living in Sweden after 1960, and immigrants who became Swedish citizens before age 18. Vital status was defined using the national Cause of Death Register. Cases were defined by the presence of a discharge diagnosis of an ASD (ICD-9 299 or ICD-10 F84). To avoid bias due to diagnostic uncertainty, 2,147 ASD cases who had ever received a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-8 295.0–295.4, 295.6 or 295.8–295.9; ICD-9 295A-295E, 295G or 295W-295X; or ICD-10 F20) or bipolar disorder (ICD-8 296.1, 296.3, 296.8; ICD-9 296A, 296C-296E or 296W; or ICD-10: F30–F31) were excluded. Ten control-relative pairs were randomly selected and matched to each case-relative pair. Controls met the following criteria: same sex and year of birth as the index case; alive, living in Sweden, and no ASD diagnosis up to the time of the proband’s initial diagnosis (to avoid bias due to left truncation and to ensure equivalent follow-up times for relatives of probands and controls) 22, 23; and controls who had ever received a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were excluded to avoid bias due to diagnostic uncertainty. Controls were also required to have a relative individually matched to the relative of a case by biological relationship, sex, and year of birth. We estimated the relation between the exposure (family history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) and the outcome (ASD) using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from conditional logistic regression models in PROC PHREG in SAS (v9.2) 24. We adjusted the CIs for non-independence within family clusters using a robust sandwich estimator function (PHREG “covsandwich” option).

Study 2 (Stockholm inpatient and outpatient) was also conducted using Swedish registries25. The base for Study 2 was all youth aged 0–17 years registered in Stockholm County from 1984–2007 (N=589,114). Cases were drawn from health services registers from Stockholm County and had: DSM-IV diagnosis of pervasive development disorder in the Stockholm County Council Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service Register 26; treatment at the Autism Centre for Young Children, Asperger Centre, or Autism Centre within Stockholm County Council Handicap and Habilitation services; or NPR diagnosis of ASD (ICD-9 299 or ICD-10 F84). Given that mental retardation is a source of heterogeneity in ASD 27, cases were also stratified by the presence or absence of clinically significant mental retardation (i.e., treatment at clinical centers specifically for ASD comorbid with mental retardation, a diagnosis of mental retardation in any register, or ASD subtype other than Asperger's syndrome). We randomly selected 10 control-relative pairs for each case. Controls also resided in Stockholm County, had no evidence of ASD (i.e., no treatment or NPR diagnosis), and were matched to cases by year of birth and sex as well as by the year of birth of the father and mother. The main exposures were schizophrenia (ICD-8 295.0–295.9, ICD-9 295A-295X, ICD-10 F20) or bipolar disorder (ICD-8 296.0–296.9, ICD-9 296A-296W, ICD-10 F31) in the parents of cases and controls. These exposures were assessed using the NPR supplemented by psychiatric out-patient treatment registers available in Stockholm county. The statistical analysis paralleled that used in Study 1.

Study 3 (Israeli conscripts). All Jewish persons born in Israel are required to participate in an assessment at age 17 prior to compulsory military service. Participation rates are 98% for males and 75% for females (women adhering to Orthodox Judaism are exempted) 28. The pre-induction assessment determines intellectual, medical, and psychiatric eligibility for compulsory military service. The draft board registry data were used to obtain the diagnostic outcomes for ASD probands and their siblings at age 17 years. Psychiatric diagnostic procedures are described elsewhere, and ICD-10 psychiatric diagnoses for ASD and schizophrenia were assigned by a board-certified psychiatrist experienced in treating adolescents 28, 29. Mood disorder diagnoses for bipolar and major depressive disorder could not confidently be assigned. Draft board psychiatrists had access to additional information for subjects under specialty care for developmental disorders. Eligible subjects were born during ten consecutive years beginning in the 1980's. Sibships within the cohort were identified using the parental national identification numbers, which are assigned to all citizens at birth or upon immigration. There were 436,697 sibships with at least two siblings per sibship, 386 ASD sibships where one sibling had a diagnosis of ASD, and 436,311 control sibships where no sibling had a diagnosis of ASD. For analysis, one non-ASD-sibling was randomly selected from ASD sibships, and one sibling was randomly selected from control sibships. As in Studies 1 and 2, the association between the exposure of sibling diagnosis of schizophrenia with proband ASD was tested using logistic regression.

Quality of register diagnoses. Swedish register diagnoses have been subjected to extensive scrutiny. The NPR is of high quality 19. For schizophrenia, the definition of affection has passed peer review on multiple occasions, direct review of case notes yields very high agreement 20, 30, the prevalence and recurrence risks to relatives 22 are nearly identical to that accepted by the field 31–34, and, most importantly, genomic findings in Swedish samples are highly consistent with those from conventionally phenotyped cases 16, 35, 36. For ASD, NPR diagnoses have good validity 37, and we have shown high agreement via review of case notes (96%). Similarly, for the Israeli register, validity has been established 28, 29.

RESULTS

We investigated the association of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives (parents or siblings) with ASD using three samples. Descriptive data for the three studies are given in Table 1. Study 1 used a Swedish national sampling frame with outcome and exposure diagnoses defined using a national patient register. Study 2 provided complementary data based on Stockholm County outpatient and inpatient health service registers. Study 3 capitalized on a standardized national pre-conscription assessment in Israel. Male sex predominated in all samples, consistent with a US survey (76–88%) 38.

Table 1.

Description of samples.

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling frame | Sweden | Stockholm county | Israel |

| Calendar years | 1973–2009 | 1984–2007 | Birth in 1980s |

| Case definition | Inpatient & outpatient registers | Treatment registers, NPR | Pre-induction assessment |

| Cases | 25,432 | 4,982 | 386 |

| Male sex | 69.1% | 72.9% | 86.3% |

| Mean age (SD) | 18.8 (14.1) | N/A | 17, by definition |

| Parent-offspring relative pairs | 47,614 | 9,964 | N/A |

| Sibling-sibling relative pairs | 30,067 | N/A | 539 |

| Mental retardation | N/A | 41.8% | N/A |

| Controls | 49,844† | 436,311 | |

| Parent-offspring relative pairs | 475,965† | ||

| Sibling-sibling relative pairs | 300,571† | ||

Controls matched to cases (10x) by sex, year of birth, and birth year and sex of relatives.

NPR=Swedish National Patient Register, SD=standard deviation. N/A=not available.

Table 2 shows associations between family history exposures and ASD outcome for all three studies. The exposure of schizophrenia in parents was a significant risk factor for ASD in probands with odds ratios (ORs) of 2.9 in both Studies 1 and 2. Studies 1 and 2 had modest overlap (~22% of the Swedish population live in the Stockholm County). Reanalysis of Study 2 after removal of inpatient ASD cases also in Study 1 yielded consistent ORs. Sibling data were available in Studies 1 and 3, and the exposure of schizophrenia in siblings was also a significant risk factor for ASD (ORs of 2.6 and 12.1 in Studies 1 and 3). The estimate from Study 3 was numerically larger, but the smaller sample size gave relatively large confidence intervals. Notably, the ORs for parents and siblings in Study 1 were numerically similar.

Table 2.

Relation between exposures (family history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) and ASD outcomes.

| Schizophrenia | Bipolar disorder | |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (Sweden national outpatient + inpatient) | ||

| Parent | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) |

| Sibling | 2.6 (2.0–3.2) | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) |

| Study 2 (Stockholm outpatient + inpatient) | ||

| Parent | 2.9 (2.0–4.1) | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) |

| Parents of ASD cases + MR | 2.6 (1.6–4.3) | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) |

| Parents of ASD cases - MR | 2.6 (1.6–4.2) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) |

| Study 2 (Stockholm outpatient only) | ||

| Parent | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) |

| Parents of ASD cases + MR | 2.7 (1.3–5.5) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| Parents of ASD cases - MR | 2.0 (1.1–3.4) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) |

| Study 3 (Israeli conscripts) | ||

| Sibling | 12.1 (4.5–32.5) | N/A |

Values shown are OR (95% confidence intervals, CIs). MR=mental retardation. Boldface indicates cells with 95% CIs that exclude 1.0.

Studies 1 and 2 had data on the exposure of bipolar disorder in parents as a risk factor for proband ASD. These associations were positive (ORs of 1.9 and 1.6 with overlapping confidence intervals). Study 1 showed similar effects for the exposure of sibling bipolar disorder.

Additional data available in Study 2 allowed stratification of ASD cases by the presence (41.8%) or absence of mental retardation (58.2%). The exposure of family history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with ASD was principally in cases without clinical indication of mental retardation. For ASD cases without mental retardation, ORs were 2.6 for schizophrenia and 1.5 for bipolar disorder compared to 1.6 and 1.1 for ASD cases with mental retardation.

Analyses evaluating the effect of sex did not reveal marked differences in associations between the exposures and ASD in Studies 1–3 as the adjusted ORs were relatively homogeneous with respect to the sex of the ASD case and the sex of the relative.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether a family history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives was associated with ASD. We analyzed three samples to understand whether an association was specific to one sample or generalized across samples.

The findings were clear. The presence of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives was a consistent and significant risk factor for ASD in all three samples. Moreover, a comparable register-based study from Denmark showed similar findings for the association of parental schizophrenia-like psychosis with ASD (OR=4.8, 95% CI 2.4–9.5) 9. We speculate that the higher sibling OR from Israel resulted from subjects with earlier onset schizophrenia which has a higher sibling recurrence risks 39. The findings from these four samples are depicted in Figure 1. These remarkably consistent findings have a number of immediate implications.

Figure 1. Effect sizes.

Forest plot of effects of exposure of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives on ASD outcome in probands. The three samples reported here are shown along with a similarly conducted study from Denmark 9.

These findings have implications for etiological research. The statistical model we used to calculate the risk associated with “exposure” to the presence of schizophrenia in parents or siblings on the outcome of ASD was one of convenience. This model is likely incomplete. We speculate that the true underlying etiological model contains an unmeasured confounder and, moreover, does not explicitly model etiological heterogeneity (which is plausible and generally assumed for these complex disorders). The confounder could be DNA sequence variation shared between the ASD probands and their parents or siblings, a common environmental risk factor to which all family members are exposed, or a gene-environment interaction. Genetic effects may be more likely given substantial heritability estimates for ASD 40, 41, schizophrenia 23, 42, and bipolar disorder 23, 43 along with evidence for relatively lesser but significant environmental effects (empirical data suggest a significant role of common environment in the etiology of both ASD and schizophrenia) 42, 44.

Our findings indicate that ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders share etiological risk factors. We suggest that future research could usefully attempt to discern risk factors common to these disorders. As one example, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium is now conducting an integrated and relatively well-powered meta-analysis of all available genome-wide association data to evaluate whether there are associations common to more than one of ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder 45.

Family history has historically served as an important validator for definitions of psychiatric disorders. If ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder share etiological risk factors, it does not necessarily follow that the disorders should be lumped into an aggregate classification. However, it is tenable that these disorders are more similar phenotypically than current appreciated, and it might prove interesting to re-evaluate the degrees of demarcation between these three disorders. Indeed, our findings are consistent with genomic data showing that the same rare copy number variants of strong effect are risk factors for both disorders. It may be that the clinical definitions of ASD and schizophrenia are derived from exemplars, individuals who have particularly distinctive and unequivocal symptoms. Definitions derived from exemplars may not be applicable to many cases seen clinically whose complex and mutable combinations of symptoms may not respect these boundaries. For individuals with ASD, assessment of psychotic symptoms is challenging particularly when language and intelligence are compromised, and some individuals with ASD cannot be evaluated. Even if assessment of psychosis is possible, the decision of whether a particular sensation, cognition, or behavior constitutes a hallucination, delusion, or thought disorder is a matter of interpretation and judgment 46. Some individuals with schizophrenia have developmental histories not inconsistent with ASD 47.

In the discussion, we focused on family history of schizophrenia as a risk factor for ASD, as the associations were generally stronger for schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. However, given increasing evidence for etiological overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorders 16, 22, we note that the analyses also support a common etiology between bipolar disorder and ASD. One potential limitation of Study 1 is that the outpatient data in the Swedish NPR is relatively new (started in 2001), and not yet complete. These data can thus not be used for prevalence estimates, but should be unbiased with regard to the analyses presented here (we believe it unlikely that the variation in reporting from different health care providers would be correlated with family history of psychotic symptoms).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder share common etiological factors. This conclusion is supported by the results of the three studies reported here along with a fourth from the literature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this project was from the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, the Swedish Research Council, and the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation. PL and CM had full access to the Swedish data, and AR and MW had full access to the Israeli data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding sources had no role in: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutter M. Childhood schizophrenia reconsidered. J Autism Child Schizophr. 1972;2(4):315–337. doi: 10.1007/BF01537622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York: International Universities Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNally K. Eugene Bleuler's four As. Hist Psychol. 2009;12(2):43–59. doi: 10.1037/a0015934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels JL, Forssen U, Hultman CM, Cnattingius S, Savitz DA, Feychting M, et al. Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1357–e1362. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson HJ, Eaton WW, Madsen KM, Vestergaard M, Olesen AV, Agerbo E, et al. Risk factors for autism: perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(10):916–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi123. discussion 26-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolton PF, Pickles A, Murphy M, Rutter M. Autism, affective and other psychiatric disorders: patterns of familial aggregation. Psychol Med. 1998;28(2):385–395. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sporn AL, Addington AM, Gogtay N, Ordonez AE, Gornick M, Clasen L, et al. Pervasive developmental disorder and childhood-onset schizophrenia: comorbid disorder or a phenotypic variant of a very early onset illness? Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(10):989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss LA, Shen Y, Korn JM, Arking DE, Miller DT, Fossdal R, et al. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levinson DF, Duan J, Oh S, Wang K, Sanders AR, Shi J, et al. Copy number variants in schizophrenia: Confirmation of five previous findings and new evidence for 3q29 microdeletions and VIPR2 duplications. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:302–316. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy SE, Makarov V, Kirov G, Addington AM, McClellan J, Yoon S, et al. Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/ng.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders SJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Hus V, Luo R, Murtha MT, Moreno-De-Luca D, et al. Multiple Recurrent De Novo CNVs, Including Duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams Syndrome Region, Are Strongly Associated with Autism. Neuron. 2011;70(5):863–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Schizophrenia Consortium. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craddock N, Owen MJ. The Kraepelinian dichotomy - going, going… but still not gone. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):92–95. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.073429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–667. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristjansson E, Allebeck P, Wistedt B. Validity of the diagnosis of schizophrenia in a psychiatric inpatient register. Nordisk Psykiatrik Tidsskrift. 1987;41:229–234. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalman C, Broms J, Cullberg J, Allebeck P. Young cases of schizophrenia identified in a national inpatient register--are the diagnoses valid? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37(11):527–531. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistics Sweden. Multi-Generation Register 2002: A description of contents and quality. Örebro, Sweden: Statistics Sweden; 2003. Report No.: 2003:5.1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenstein P, Bjork C, Hultman CM, Scolnick EM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF. Recurrence risks for schizophrenia in a Swedish national cohort. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1417–1426. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lichtenstein P, Yip B, Bjork C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, et al. Common genetic influences for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A population-based study of 2 million nuclear families. Lancet. 2009;373:234–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/Genetics® User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnusson C, Rai D, Goodman A, Lundberg M, Idrizbegovic S, Svensson AC, et al. Migration and autism spectrum disorders: a population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095125. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernell E, Gillberg C. Autism spectrum disorder diagnoses in Stockholm preschoolers. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31(3):680–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szatmari P, White J, Merikangas KR. The use of genetic epidemiology to guide classification in child and adult psychopathology. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(5):483–496. doi: 10.1080/09540260701563619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichenberg A, Gross R, Weiser M, Bresnahan M, Silverman J, Harlap S, et al. Advancing paternal age and autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(9):1026–1032. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiser M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, Kaplan Z, Mark M, Bodner E, et al. Association between nonpsychotic psychiatric diagnoses in adolescent males and subsequent onset of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(10):959–964. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekholm B, Ekholm A, Adolfsson R, Vares M, Osby U, Sedvall GC, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic procedures in Swedish patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;59:457–464. doi: 10.1080/08039480500360906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2(5):e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Risch N. Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits: I. Multilocus models. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1990;46:222–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottesman II, Shields J. Schizophrenia: The Epigenetic Puzzle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottesman II. Schizophrenia Genesis: The Origins of Madness. New York: WH Freeman; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Schizophrenia Consortium. Greater burden of rare copy number variants in schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study Consortium. Genome-wide association study of schizophrenia identifies five novel loci. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hultman CM, Sandin S, Levine SZ, Lichtenstein P, Reichenberg A. Advancing paternal age and risk of autism: new evidence from a population-based study and a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Molecular psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(10):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svensson AC, Lichtenstein P, Sandin S, Oberg S, Sullivan PF, Hultman CM. Familial aggregation of schizophrenia: the moderating effects of age at onset, parental immigration, paternal age and season of birth. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1403494811420485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, et al. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995;25(1):63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lichtenstein P, Carlstrom E, Rastam M, Gillberg C, Anckarsater H. The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1357–1363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1187–1192. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):497–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, et al. Genetic Heritability and Shared Environmental Factors Among Twin Pairs With Autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cross Disorder Phenotype Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium. Dissecting the phenotype in genome-wide association studies of psychiatric illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:97–99. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.063156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volkmar FR, Cohen DJ. Comorbid association of autism and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(12):1705–1707. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rapoport J, Chavez A, Greenstein D, Addington A, Gogtay N. Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(1):10–18. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]