Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The global HIV/AIDS response has advanced in addressing the health and well-being of HIV-positive children. Although attention has been paid to children orphaned by parental AIDS, children who live with HIV-positive caregivers have received less attention. This study compares mental health problems and risk and protective factors in HIV-positive, HIV-affected (due to caregiver HIV), and HIV-unaffected children in Rwanda.

METHODS:

A case-control design assessed mental health, risk, and protective factors among 683 children aged 10 to 17 years at different levels of HIV exposure. A stratified random sampling strategy based on electronic medical records identified all known HIV-positive children in this age range in 2 districts in Rwanda. Lists of all same-age children in villages with an HIV-positive child were then collected and split by HIV status (HIV-positive, HIV-affected, and HIV-unaffected). One child was randomly sampled from the latter 2 groups to compare with each HIV-positive child per village.

RESULTS:

HIV-affected and HIV-positive children demonstrated higher levels of depression, anxiety, conduct problems, and functional impairment compared with HIV-unaffected children. HIV-affected children had significantly higher odds of depression (1.68: 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15–2.44), anxiety (1.77: 95% CI 1.14–2.75), and conduct problems (1.59: 95% CI 1.04–2.45) compared with HIV-unaffected children, and rates of these mental health conditions were similar to HIV-positive children. These results remained significant after controlling for contextual variables.

CONCLUSIONS:

The mental health of HIV-affected children requires policy and programmatic responses comparable to HIV-positive children.

Keywords: mental health, child, HIV/AIDS, HIV-affected, HIV-infected, Rwanda

What’s Known on This Subject:

Research has shown that HIV-affected children face considerable threats to health and mental health. Few studies have investigated the effects of HIV on the health and well-being of HIV-negative children living with HIV-positive caregivers.

What this Study Adds:

By comparing the prevalence of mental health problems and protective and risk factors among HIV-positive, HIV-affected, and HIV-unaffected children in Rwanda, this study demonstrates that the mental health of HIV-affected children requires policy and programmatic responses comparable to HIV-positive children.

HIV poses a direct threat to child and adolescent health, family functioning, and well-being. Given the burden of stigma, poverty, and stressors related to consequences of HIV in the family, the mental health of children affected by HIV is particularly at risk. Research has shown that illness and loss due to HIV/AIDS are associated with parental depression, hopelessness, and risk behaviors, such as drug and alcohol problems.1 HIV-positive children and children affected by HIV (ie, those who have caregivers living with HIV or family members who have died of AIDS) may face greater family stress and conflict,2 difficulties with peer relationships due to HIV-related stigma,3–6 and increased risk of depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal.7–12 For HIV-affected children, parental illness or death may shift family responsibilities to them at a young age, contributing to school dropout, emotional and behavioral problems, and risky survival strategies, such as exchanging sex for money,13–15 further perpetuating a cycle of HIV risk and infection.16,17

Although the elevated risks facing HIV/AIDS-affected orphans and vulnerable children are well documented, the risk in HIV-negative children who live with HIV-positive caregivers compared with HIV-positive children and children unaffected by HIV is less clear.18 Child health status, cognitive function, parental health and mental health, stressful life events, and neighborhood disorder have been associated with poor mental health, whereas parent-child involvement and communication, and peer, parent, and teacher social support have been associated with better mental health outcomes.19,20 The objective of this study was to assess the distribution of mental health problems and protective and risk factors in a sample of HIV-positive, HIV-affected, and HIV-unaffected children in Rwanda. The inclusion of all 3 groups allows for a direct comparison of mental health by HIV status. Such research can identify services gaps and needs.

Methods

Population and Study Design

This study was conducted as a partnership between the Harvard School of Public Health, the Rwandan Ministry of Health (MOH), and Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima, a nongovernmental organization providing health care in 3 districts in rural Rwanda. The study was implemented within the catchment area of district hospitals in Rwinkwavu (southern Kayonza District) and Kirehe (Kirehe District). These hospitals serve as administrative and referral hubs for 21 district health centers that provide routine antiretroviral therapy (ART), counseling, and testing for individuals living with HIV (ie, individuals with verified HIV infection who are receiving treatment).21,22 At Rwinkwavu and Kirehe Hospitals, an electronic medical record (EMR) system is maintained for all registered patients with HIV infection.

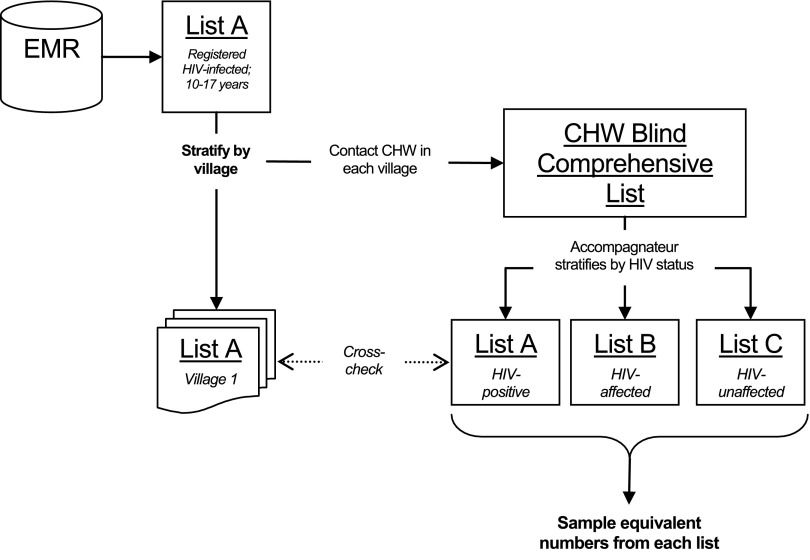

Using a case-control study design, we enrolled a sample of 683 children between March 2012 and December 2012. Sampling followed a multiple-step process. First, hospital staff used the EMR to identify known HIV-positive children aged 10 to 17 from Kayonza and Kirehe Districts. This initial list (List A) was then stratified by village, and for each village, a community health worker (CHW) compiled a comprehensive list of all children aged 10 to 17. In Rwanda, CHWs are assigned to track the health of members of a village with approximately 50 households for each CHW. Next, accompagnateurs (specialized CHWs who monitor ART adherence)23,24 were then asked to review the lists and stratify them by HIV status. On review of the lists, the accompagnateurs identified 37 additional HIV-positive children who had not yet been entered into the EMR; these additional children were added to List A. In each village, children with an HIV-positive caregiver or who had a parent known to have died due to complications of AIDS were added to List B, which captured HIV-affected children. The remaining children in the same age range in each village who were known not to have HIV themselves or in their family were defined as “unaffected” and were added to List C. A random number generator was then used to select HIV-affected and unaffected children from Lists B and C in each village where a child living with HIV infection resided who consented to participate, allowing for a case-control design comparing HIV-positive, HIV-affected, and HIV-unaffected children, matching on village to account for geographic differences. Matching on age and gender was not necessary or logistically feasible given the relatively large sample size, which led to approximately equal distribution of these characteristics across groups. If the index HIV-positive child in a village declined participation, no matched participants from Lists B or C were sampled.

We anticipated that the study sample size of 250 subjects in each of the 3 groups (n = 750) would provide 82% power to detect expected group mean differences (0.25 SD, α level = 0.05).25 Because the number of HIV-positive children in the EMR fell just short of this target (n = 239), the target study population was reduced to 717. Of this number, 683 participated in the study, resulting in a response rate of >95%.

This study received approval from the Harvard School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration and the Rwanda National Ethics Committee. Parental/guardian informed consent and child assent were obtained for all study participants. Children were eligible for the study if they were aged 10 to 17 years and had resided in Kayonza or Kirehe Districts for at least 1 month. For each child, a coresident adult caregiver also was enrolled and asked to report on their own mental health, that of the child, and related factors. Participants were excluded if they were experiencing active psychosis or had a severe cognitive impairment (as identified by study psychologists), compromising their ability to understand the study consent procedures and materials (n = 5). Further detail on sampling is provided in Fig 1.

FIGURE 1.

Sampling strategy.

Procedures

Mental health problems, protective factors, and risk factors were assessed in all children and caregivers enrolled. A team of 7 Rwandan research assistants carried out all assessments in Kinyarwanda, the local language, with oversight from the study field coordinators and investigators. All research assistants were trained in research ethics and survey research methods. Interviews were performed in participants’ homes, with child and caregiver interviews conducted concurrently and out of earshot of one another. Data were collected electronically by using Samsung Galaxy GT 15503 smartphones (Samsung Town, Seoul, South Korea) running on an Android platform. Study data were de-identified and uploaded to DataDyne’s episurveyor.org Web site where they were downloaded for analysis.

Measures

Constructs reflecting common child and adolescent mental health problems and functional impairments were identified in 2 previous qualitative studies conducted in 2007 and 2009.26,27 These studies used qualitative data to derive local terms for mental health problems and protective resources. Standard mental health measures were then identified via a literature review of measures used to assess similar constructs in children and examined for their fit to local indicators. When a good fit was indicated (by a concordance of at least 50% of items), standard measures were adapted to include local terminology. For culturally unique constructs (such as the Rwandan construct of uburara or “conduct problems”), new scales were constructed by using indicators from qualitative data. All measures were subjected to a thorough forward and backward translation process and a validity exercise among 378 child-caregiver dyads.28,29 Following a process described previously,29 all scales were selected, adapted, and validated by comparing scores to diagnoses by Rwandan psychologists by using a structured diagnostic instrument (the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children).30

Functional impairment was assessed using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for Children (WHODAS-Child), a measure of functional limitations based on WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, Child and Youth Version. The WHODAS-Child is a 36-item self-report assessment of difficulties in 6 domains: understanding and communicating, mobility, self-care, getting along with people, life activities, and participation in society. As shown in a previous article, the WHODAS-Child displayed good psychometric properties in this sample.28

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC),31 which has been previously used in Rwanda,32 was used to capture depressionlike problems (agahinda kenshi and kwiheba), including a range of symptoms, such as hopelessness, having emotional pain (arababaye ku mutima), and suicidal ideation. The CES-DC is a commonly used 20-item self-report scale with a 4-point Likert response scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot.” In our validation study, the CES-DC demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.86) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.85).29 Per our validation exercises using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children, a threshold of 30 was used (sensitivity 82%; specificity 72%).

To assess symptoms of constant worry/stress (guhangayika), we used the Youth Self-Report (YSR) Internalizing Subscale.33 The YSR Internalizing Subscale has 13 anxious/depressed items and 8 withdrawn/depressed items, with a 3-point Likert scale response format of “not true,” “very true,” or “often true.” Because the YSR internalizing scale did not capture all of the local items in the construct of guhangayika, we added 10 additional items based on local symptoms from qualitative data. This adapted YSR anxiety/internalizing scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.93) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.85) in our validation study. A threshold of 24 was used, with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 63%, which was significantly associated with functional impairments.28

Because no standard scale matched 50% or more of the qualitative data on indicators of conduct problems (uburara) in this setting, the data were used to construct an 11-item self-report scale. This allowed for conduct problems to be identified in a manner that reflected cultural and context-specific rule-breaking behaviors. Response options were on a 4-point Likert scale from “never” to “often.” This locally derived scale displayed good internal consistency (α = 0.90) and adequate test-retest reliability (r = 0.58) in our validation study. A threshold of 0.55 was used, with a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 68%, and was significantly associated with functional impairments.

Other variables included were: parenting, measured by a locally derived scale comprising 16 items to capture the concept uburere bwiza (good parenting), that also included 16 additional items from the Parental Acceptance and Rejection Questionnaire,34 which displayed good internal consistency (α = 0.80); harsh punishment, measured by a 12-item scale adapted from the United Nations Children’s Fund’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey35 (α = 0.78); daily hardships, measured by an adapted version of the Post-War Adversities Index (18 items), which had been used previously in sub-Saharan Africa36 and included items such as food insecurity and illness in the family (internal consistency in this sample α = 0.80); social service access, including medical and social support services, reported by caregivers and measured by 17 items adapted from the SAFE child protection checklist15 (α = 0.70); and HIV-related stigma, measured by 13 items adapted from the Young Carers Project.37 Frequency of experiencing interpersonal interactions indicative of HIV-related stigma was reported on a 4-point Likert scale of “never,” “sometimes,” or “often/a lot.” When a stigma item was endorsed, children were then asked to report why they thought it happened. Caregiver assessments also included the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25,38 a measure of depression and anxiety symptoms that had been previously validated for use among adults in Rwanda39 and displayed good internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.94).

Data Analysis

Multiple regression analysis was used to examine relationships between HIV status and key outcomes of interest. Mental health problems were regressed on child HIV status per child and parent-reported outcomes (see Tables 1 and 2). Model 1 is the unadjusted model. Model 2 adjusts for child age (measured continuously), gender, school attendance, whether the child’s mother was the primary caregiver, and socioeconomic status (SES), measured by a family wealth index created using items from the 2010 Rwandan Demographic and Health Survey.40 Model 3 includes additional contextual variables that could account for differences in child mental health: caregiver mental health, daily hardships, death of a caregiver, social service access, harsh punishment, and stigma. For ease of comparison, the marginal means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed based on the regression coefficients and SEs. Because of the extremely low proportion of missing data (<1% for all measures), participants with missing data were omitted from the analysis using list-wise deletion. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios of mental health problems in HIV-positive and HIV-affected children, compared with HIV-unaffected children. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

TABLE 1.

Regression Coefficients (SE) for Mental Health Problems Regressed on Child HIV Status, Child Reports, n = 683

| CES-DC | YSR-Anxiety/Internalizing | Conduct Problems | WHODAS-Child | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Intercept | 26.84** (1.20) | 15.53* (6.33) | 8.89 (5.68) | 0.54** (0.03) | −0.08 (0.15) | −0.23 (0.14) | 0.31** (0.04) | 0.51* (0.19) | 0.24 (0.18) | 13.36** (0.74) | −1.48 (3.98) | −5.97 (3.67) |

| HIV-positive | 2.65 (1.72) | 1.59 (1.72) | .-0.88 (1.67) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | 1.58 (1.07) | 1.12 (1.08) | −0.84 (1.08) |

| HIV-affected | 5.66* (1.70) | 5.24* (1.66) | 2.06 (1.49) | 0.10* (0.04) | 0.09* (0.05) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.11* (0.05) | 0.11* (0.05) | 0.03 (0.05) | 3.23* (1.06) | 3.17* (1.05) | 1.19 (0.96) |

| Age | — | 0.99* (0.33) | 0.52 (0.30) | — | 0.01** (0.01) | 0.03*** (0.01) | — | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.0 (0.01) | — | 0.93 (0.21) | 0.67** (0.19) |

| Female | — | 1.92 (1.38) | 1.22 (1.21) | — | 0.09* (0.03) | 0.07* (0.03) | — | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.08* (0.04) | — | 1.19 (0.87) | 0.71 (0.78) |

| SES | — | −2.59** (0.70) | −1.07 (0.63) | — | −0.03 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | — | −0.03 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | — | −0.43 (0.44) | 0.29 (0.41) |

| Education | — | −3.33 (2.52) | −2.56 (2.20) | — | −0.11 (0.06) | −0.08 (0.05) | — | −0.16* (0.07) | −0.14* (0.07) | — | 0.89 (1.59) | 0.99 (1.41) |

| Primary caregiver is mother | — | −3.03* (1.45) | −2.07 (1.29) | — | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.21 (0.03) | — | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.04) | — | −0.58 (0.91) | 0.22 (0.83) |

| Parental death | — | — | 0.68 (1.41) | — | — | 0.03 (0.03) | — | — | −0.02 (0.04) | — | — | 1.94* (0.91) |

| Daily hardships | — | — | 1.09** (0.23) | — | — | 0.43** (0.07) | — | — | 0.01 (0.01) | — | — | 0.58** (0.15) |

| Social service access | — | — | −0.253 (1.09) | — | — | −0.04 (0.03) | — | — | 0.00 (0.03) | — | — | 0.63 (0.70) |

| Caregiver HSCL | — | — | 3.59** (0.99) | — | — | 0.05* (0.02) | — | — | 0.06 (0.03) | — | — | 1.65* (0.64) |

| Harsh punishment | — | — | 16.34** (2.94) | — | — | 0.43** (0.07) | — | — | 0.68*** (0.09) | — | — | 11.88** (1.90) |

| Stigma | — | — | 7.97** (1.32) | — | — | 0.22** (0.03) | — | — | 0.21*** (0.04) | — | — | 3.92** (0.85) |

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.26 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| n | 681 | 679 | 666 | 681 | 679 | 666 | 681 | 679 | 666 | 681 | 678 | 666 |

***P < .001, **P < .01, *P < .05. HSCL, Hopkins Symptoms Checklist.

TABLE 2.

Regression Coefficients (SE) for Mental Health Problems Regressed on Child HIV Status, Parent Reports n = 683

| CES-DC | YSR-Anxiety/Internalizing | Conduct Problems | WHODAS-Child | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Intercept | 27.66** (1.22) | 15.16* (6.48) | 5.26 (5.86) | 0.52** (0.03) | 0.11 (0.15) | −0.22* (0.13) | 0.37** (0.04) | 0.81** (0.21) | 0.30 (0.19) | 13.36** (0.74) | −1.48* (3.98) | −3.44 (4.12) |

| HIV-positive | 2.41 (1.76) | 2.94 (1.76) | −0.73 (1.74) | 0.13* (0.04) | 0.14* (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.18* (0.06) | 0.16* (0.06) | 0.02 (0.06) | 1.58 (1.07) | 1.12 (1.08) | −0.34 (1.22) |

| HIV-affected | 4.08* (1.74) | 3.85* (1.70) | −0.09 (1.52) | 0.14* (0.04) | 0.14* (0.04) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.15* (0.06) | 0.14* (0.06) | 0.00 (0.05) | 3.23* (1.06) | 3.17* (1.05) | 2.16* (1.06) |

| Age | — | 1.02* (0.34) | 0.90* (0.30) | — | 0.03* (0.01) | 0.03** (0.01) | — | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | — | 0.93** (0.21) | 0.88** (0.21) |

| Female | — | 0.22 (1.42) | 0.20 (1.23) | — | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | — | −0.17** (0.05) | −0.15** (0.04) | — | 1.19 (0.87) | 1.01 (0.86) |

| SES | — | −2.86** (0.72) | −1.53* (0.64) | — | −0.07** (0.02) | −0.04* (0.01) | — | −0.06* (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | — | −0.43 (0.44) | 0.05 (0.45) |

| Education | — | −4.55 (2.58) | −6.12* (2.23) | — | −0.03** (0.06) | −0.06 (0.05) | — | −0.28* (0.08) | −0.30** (0.07) | — | 0.89 (1.59) | 0.58 (1.57) |

| Primary caregiver is mother | — | 3.72* (1.49) | 0.29 (1.32) | — | 0.09* (0.04) | 0.02 (0.03) | — | −0.08 (0.05) | 0.13* (0.04) | — | −0.58 (0.91) | −0.83 (0.92) |

| Parental death | — | — | −0.41 (1.44) | — | — | 0.02 (0.03) | — | — | 0.04 (0.05) | — | — | 2.51* (1.02) |

| Daily hardships | — | — | 0.58** (0.14) | — | — | 0.01** (0.00) | — | — | 0.01* (0.00) | — | — | 0.12 (0.10) |

| Social services access | — | — | −0.33 (1.11) | — | — | 0.01 (0.03) | — | — | −0.02 (0.04) | — | — | −0.59 (0.78) |

| Caregiver HSCL | — | — | 10.08** (1.16) | — | — | 0.23** (0.03) | — | — | 0.12* (0.04) | — | — | 1.38 (0.81) |

| Harsh punishment | — | — | −1.30 (3.46) | — | — | 0.07 (0.08) | — | — | 0.66** (0.11) | — | — | 2.36 (2.43) |

| Stigma | — | — | 5.66** (1.10) | — | — | 0.17** (0.02) | — | — | 0.25** (0.04) | — | — | 2.02* (0.77) |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| n | 683 | 679 | 666 | 683 | 679 | 666 | 683 | 679 | 666 | 683 | 679 | 666 |

HSCL, Hopkins Symptoms Checklist.

Results

Mental Health

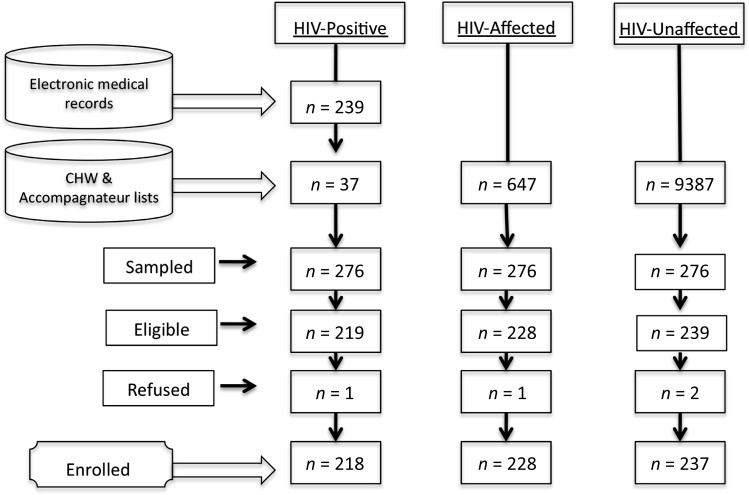

The final sample contained a total of 683 children, 218 of whom were HIV-infected, 228 HIV-affected, and 237 HIV-unaffected. A summary of participants screened and enrolled appears in Fig 2. Demographic characteristics of participants are shown in Table 3.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of participants.

TABLE 3.

Participant Demographics, n = 683

| HIV-Positive, n = 218 | HIV-Affected, n = 228 | HIV-Unaffected, n = 237 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | |||

| Mean age, y (SD) | 13.79 (2.27) | 13.46 (2.16) | 13.57 (2.14) |

| Mean SES index (SD) | 0.03 (1.02) | −0.07 (0.89) | 0.04 (1.09) |

| Boys, n (%) | 108 (50) | 111 (49) | 111 (47) |

| Mother is primary caregiver, n (%) | 97 (44) | 150 (66) | 161 (68) |

| Caregivers | |||

| Mean age, y (SD) | 46.37 (14.10) | 43.01 (8.68) | 44.70 (10.66) |

| Men, n (%) | 42 (19) | 44 (19) | 53 (22) |

Parents of HIV-positive children were significantly older than parents in the affected group. HIV-positive children were significantly less likely than those in the other 2 groups for the mother to be the main caregiver.

Across all mental health variables, HIV-affected children demonstrated levels of problems that were significantly higher than HIV-unaffected children and not statistically different from HIV-positive children, both in the youth self-report and caregiver report (Tables 1 and 2). Estimates adjusted for age, gender, education, SES, and primary caregiver displayed the same pattern of significant effects as unadjusted estimates, demonstrating comparable levels of vulnerability in HIV-positive and HIV-affected children on both parent and child reports.

For instance, HIV-affected children also had significantly higher odds of having clinical levels of depression, controlling for gender, age, education, primary caregiver, and SES (1.68: 95% CI 1.15–2.44; P = .007), anxiety/internalizing problems (1.77: 95% CI 1.14–2.75; P = .012), and conduct disorder (1.59: 95% CI 1.04–2.45; P = .032) compared with HIV-unaffected children (Supplemental Table 4). Odds ratios for mental health problems in HIV-positive children and HIV-affected children were not different at the P < .05 level of significance (comparisons not shown).

Contextual Variables and Family Dynamics

Several contextual variables differed among the 3 groups of children at various levels of HIV experience. Both HIV-affected groups reported experiencing greater levels of stigma than children who were not affected by HIV. However, only HIV-affected children, not HIV-infected children, reported experiencing greater levels of daily hardships and harsh punishment than children unaffected by HIV. In addition, HIV-affected and HIV-positive children were more likely to have experienced the death of a caregiver (odds ratios of 1.78 and 6.26, respectively compared with unaffected children), and HIV-positive children were significantly less likely than those in the other 2 groups to have their mother as their primary caregiver. These results are provided in Supplemental Table 5.

When these contextual variables were added to the original regressions, as displayed in Model 3, there were no significant differences between the groups on any mental health outcome (Tables 1 and 2), indicating that these variables have an explanatory role in the differences observed between groups on the mental health outcomes in this analysis.

Discussion

Although the global AIDS response has increased access to ART for HIV-positive children, the needs of children more broadly affected by HIV still require far more attention.41,42 The current study illuminates important vulnerabilities of children both infected and affected by HIV. Furthermore, children affected by HIV because of living with an HIV-positive caregiver or who had a caregiver die of AIDS present a burden of psychological distress comparable to that facing HIV-positive children. Not surprisingly, HIV-affected and HIV-positive children are more likely to have experienced the death of a caregiver, which may contribute to psychological distress as well as result in additional family responsibilities. Even when a caregiver has not died, children of HIV-positive caregivers may have to assume additional responsibilities when parents are ill and unable to work. The finding that HIV-affected children report greater daily hardships perhaps reflects this reality.

Our analyses also demonstrate that HIV-affected and HIV-positive children experience comparable levels of stigma, presenting another potential mechanism underlying increased risk for mental health problems. Our finding that HIV-affected children experience a greater level of harsh punishment may reflect a reactive process related to family stress and violence that has been observed at elevated rates in other studies of HIV-affected households.43,44 The fact that daily hardships and parental mental health appear to influence child mental health in addition to child HIV status makes sense in the context of Rwanda, given the historical and economic context of the 1994 genocide.45,46 Parental mental health and economic security need to be considered when developing psychosocial programs for children affected by HIV/AIDS.

A number of study limitations must be noted. First of all, it was not ethically or logistically feasible to administer a test of HIV seropositivity at the time of assessment for all individuals enrolled in the study. In Rwanda, testing is not compulsory, but there are robust systems of routine HIV testing widely available. However, if an individual had chosen not to be tested or had tested HIV-positive in a health center outside the catchment area and not disclosed it to a CHW or accompagnateur in their village, then the CHWs would not know the HIV status of an individual and it would not be recorded in the EMR. This potential for error in our sampling strategy is most relevant to households designated as “unaffected by HIV,” as there would be more likelihood in those households that someone could be HIV-positive and unaware. On the other hand, in Rwanda, testing also is done widely among pregnant women and strongly emphasized for all households in which any member has been diagnosed with HIV. This gives us confidence in the HIV status of the index HIV-positive child and also the HIV-affected children, as all of those children had been tested in our study at least once. There could certainly have been cases where a child designated as unaffected or HIV-negative (but affected) became seropositive, but given the age of our sample and dynamics of HIV infection in Rwanda,47,48 these cases are estimated to be relatively few and not systematically ascribed to either the unaffected or affected groups.

Generalizability

The Government of Rwanda’s Ministry of Health provides a robust level of health and social programs for HIV-positive children, including a national health insurance scheme, well-developed HIV care, and a growing system of mental health services. Even higher levels of mental health problems and risk factors may be observed in other resource-limited settings where health services are less robust. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that even in an increasingly supportive context in Rwanda, HIV-affected youth contend with serious threats to their mental health, comparable to HIV-positive youth. As services for HIV-positive children improve globally, additional awareness is needed for children who live with HIV-positive caregivers, along with ongoing attention to children orphaned by AIDS. As the availability of ART increases and the lives of HIV-positive caregivers are extended, priority attention is needed to ensure that mental health and social services programming and policy initiatives for HIV-affected children are on par with that for HIV-positive children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by the collaboration and dedication of the Rwandan Ministry of Health and Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima. We are forever grateful to the local research team who carried out these interviews and to the study participants and their families. In addition, we thank Christina Mushashi, Morris Munyanah, and Joia Mukherjee for their ongoing guidance and support throughout our work.

Glossary

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- CES-DC

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children

- CHW

community health worker

- CI

confidence interval

- EMR

electronic medical record

- SES

socioeconomic status

- WHODAS-Child

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for Children

- YSR

Youth Self-Report

Footnotes

Dr Betancourt conceptualized and designed the study, oversaw acquisition of the data, and contributed to statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content, obtaining funding, and supervision of the study; Dr Scorza contributed to acquisition of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and administrative, technical, and material support; Mr Kanyanganzi contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and study supervision; Dr Fawzi contributed to study concept and design, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, reviewing and revising the article for intellectual content, obtaining funding, and study supervision; Dr Sezibera contributed to study concept and design, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript; Dr. Cyamatare contributed to study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content; Dr Beardslee contributed to study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, and revising it critically for important intellectual content, obtaining funding, and study supervision; Dr Stulac contributed to study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, obtaining funding, and study supervision; Mr Bizimana contributed to administrative, technical, and material support, to drafting of the manuscript, and interpretation of the data; Ms Stevenson contributed to acquisition of the data, drafting of the manuscript, the administrative, technical, and material support, supervised data collection in the field for 1 of the 2 sites, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Kayiteshonga contributed to the study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in terms of accuracy and integrity and have approved the final version of the manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This study was supported by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research grant P30 AI060354, National Institute of Mental Health grant 1K01MH07724601 A2, the Peter C. Alderman Foundation, the Harvard Center for the Developing Child, the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, the Harvard School of Public Health Career Incubator Fund, and the Julie Henry Family Development Fund. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Rochat TJ, Richter LM, Doll HA, Buthelezi NP, Tomkins A, Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1376–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotheram-Borus M, Lee S-J, Amani B, Swendeman D. Adaptation of Interventions for Families Affected by HIV. In: Pequegnat W, Bell CC, eds. Family and HIV/AIDS: Springer New York; 2012:281–302 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowshen N, D’Angelo L. Health care transition for youth living with HIV/AIDS. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):762–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cluver L, Gardner F. The psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cluver LD, Gardner F, Operario D. Effects of stigma on the mental health of adolescents orphaned by AIDS. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(4):410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele RG, Nelson TD, Cole BP. Psychosocial functioning of children with AIDS and HIV infection: review of the literature from a socioecological framework. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(1):58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozyce ML, Lee SS, Wiznia A, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV-infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):763–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doku PN. Parental HIV/AIDS status and death, and children’s psychological wellbeing. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2009;3(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauman LJ, Germann S. Psychosocial impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on children and youth. In: Foster G, Levine C, Williamson J, eds. Generation at Risk: The Global Impact of HIV/AIDS on Orphans and Vulnerable Children. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007:93–133 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauman LJ, Silver EJ, Draimin BH, Hudis J. Children of mothers with HIV/AIDS: unmet needs for mental health services. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/5/e1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chernoff M, Nachman S, Williams P, et al. IMPAACT P1055 Study Team . Mental health treatment patterns in perinatally HIV-infected youth and controls. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):627–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertou G, Thomaidis L, Spoulou V, Theodoridou M. Cognitive and behavioral abilities of children with HIV infection in Greece. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S100

- 13.Betancourt TS, Williams TP, Kellner SE, Gebre-Medhin J, Hann K, Kayiteshonga Y. Interrelatedness of child health, protection and well-being: an application of the SAFE model in Rwanda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1504–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cluver L, Operario D. Inter-generational linkages of AIDS: vulnerability of orphaned children for HIV infection. IDS Bull. 2008;39(5):27–35 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betancourt TS, Fawzi MKS, Bruderlein C, Desmond C, Kim JY. Children affected by HIV/AIDS: SAFE, a model for promoting their security, health, and development. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(3):243–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stiffman AR, Doré P, Earls F, Cunningham R. The influence of mental health problems on AIDS-related risk behaviors in young adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(5):314–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham RM, Stiffman AR, Doré P, Earls F. The association of physical and sexual abuse with HIV risk behaviors in adolescence and young adulthood: implications for public health. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18(3):233–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mellins CA, Malee KM. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1):18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Valentin C, Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: the role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family factors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(10):1065–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forehand R, Steele R, Armistead L, Morse E, Simon P, Clark L. The Family Health Project: psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV infected. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(3):513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stulac SN, Harrington EK, Niyigena PC, et al. Implementing pediatric antiretroviral therapy as part of comprehensive HIV care in rural Rwanda. Paper presented at: XVI International AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stulac SN, Bucyibaruta B, Iyamungu G, et al. ART delivery and adherence in a program for comprehensive pediatric HIV care in rural Rwanda. Paper presented at: Second National Conference on the Treatment, Care, and Support of Children Infected and Affected by HIV/AIDS; November 20, 2006; Kigali, Rwanda [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merkel E, Gupta N, Nyirimana A, et al. Clinical outcomes among HIV-positive adolescents attending an integrated and comprehensive adolescent-focused HIV care program in rural Rwanda. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2013;12(3–4):437–450 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rich ML, Miller AC, Niyigena P, et al. Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):e35–e42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forsyth BW, Damour L, Nagler S, Adnopoz J. The psychological effects of parental human immunodeficiency virus infection on uninfected children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(10):1015–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki S, Stulac SN, Barrera AE, Mushashi C, Beardslee WR. Nothing can defeat combined hands (Abashize hamwe ntakibananira): protective processes and resilience in Rwandan children and families affected by HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(5):693–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betancourt TS, Rubin-Smith JE, Beardslee WR, Stulac SN, Fayida I, Safren S. Understanding locally, culturally, and contextually relevant mental health problems among Rwandan children and adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2011;23(4):401–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scorza P, Stevenson A, Canino G, et al. Validation of the “World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for children, WHODAS-Child” in Rwanda. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e57725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betancourt T, Scorza P, Meyers-Ohki S, et al. Validating the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for children in Rwanda. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1284–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33, quiz 34–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20(2):149–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boris NW, Brown LA, Thurman TR, et al. Depressive symptoms in youth heads of household in Rwanda: correlates and implications for intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(9):836–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21(8):265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rohner, RP, Saavedra JM, Granum, EO. Development and validation of the parental acceptance-rejection questionnaire: Test manual. JSAS MS. 1635. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association: 1978

- 35.UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys - Round 4. 2009. Available at: www.childinfo.org/mics4_background.html. Accessed August 5, 2011

- 36.Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(6):606–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyes ME, Mason SJ, Cluver LD. Validation of a brief stigma-by-association scale for use with HIV/AIDS-affected youth in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2013;25(2):215–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolton P. Cross-cultural validity and reliability testing of a standard psychiatric assessment instrument without a gold standard. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(4):238–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], and ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Calverton, MD: NISR, MOH, and ICF International; 2012

- 41.World Health Organization. HIV and Adolescents: Guidance for HIV Testing and Counselling and Care for Adolescents Living With HIV: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach and Considerations for Policy-makers and Managers. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. Guideline on HIV Disclosure Counseling for Children up to 12 Years of Age. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cluver L, Bowes L, Gardner F. Risk and protective factors for bullying victimization among AIDS-affected and vulnerable children in South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(10):793–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes ME, Sherr L, Makasi D, Nikelo J. Pathways from parental AIDS to child psychological, educational and sexual risk: developing an empirically-based interactive theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.UNAIDS. Country Progress Report: Rwanda. Available at: www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_RW_Narrative_Report[1].pdf. Submitted March 30, 2012. Accessed December 15, 2013

- 46.United Nations Development Program. Human Development Report 2013: Rwanda. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/Country-Profiles/RWA.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2013

- 47.United Nations Children's Fund. UNICEF welcomes Rwanda’s campaign to eliminate HIV transmission from mother to child. Available at: www.unicef.org/media/media_58535.html. Published May 13, 2011. Accessed December 16, 2013

- 48.Rwanda Biomedical Center. National Report on HIV & AIDS July 2010-June 2011. Available at: www.rbc.gov.rw/IMG/pdf/national_annual_report_on_hiv_aids_july_2010_june_2011.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed December 16, 2013

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.