Abstract

Objective

This study presents reliability and validity findings for the Assessment for Disaster Engagement with Partners Tool (ADEPT), an instrument that can be used to monitor the frequency and nature of collaborative activities between local health departments (LHDs) and community-based organizations (CBOs) and faith-based organizations (FBOs) for disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

Methods

We used formative research to develop the instrument by ranking LHDs according to their disaster outreach and engagement activities. We validated the scale through a 2011 national survey of disaster preparedness coordinators (n=273) working in LHDs. We reduced the original measure of 25 items to a final measure comprising 15 items with four dimensions: (1) communication outreach and coordination, (2) resource mobilization, (3) organizational capacity building, and (4) partnership development and maintenance. We used internal consistency reliability m correlation and factor analysis to validate the measure.

Results

Using internal consistency reliability, we found reasonable inter-item reliability for the four hypothesized dimensions (Cronbach's alpha: 0.71–0.88). These four dimensions were confirmed through correlation and factor analysis (Varimax rotation).

Conclusion

Higher scores on all four dimensions of ADEPT for organizational respondents suggest that more activities were conducted for inter-organizational preparedness in those organizations than in organizations whose respondents had lower scores. This finding implies that organizations with higher ADEPT scores have more active relationships with CBOs/FBOs in the realm of preparedness, a key element for creating community resilience for emergencies and disaster preparedness.

It has been well documented that before, during, and after disasters, vulnerable populations frequently turn first to trusted community-based organizations (CBOs) and faith-based organizations (FBOs) for disaster information, resources, shelter, or other assistance rather than to government, media, or official sources.1–9 For example, CBOs and FBOs provided essential services to victims and residents following the 2001 World Trade Center attack.10–13 Recent events, such as the earthquake in Haiti, Hurricanes Irene and Sandy on the East Coast of the United States, and serious tornadoes and wildfires, suggest the importance of CBOs/FBOs for reaching vulnerable populations before, during, and after disasters, with some criticizing ineffective governmental response following Hurricane Katrina compared with CBOs/FBOs6,7,9,14 that often serve vulnerable populations.8,15 As local health departments (LHDs) have become more engaged in disaster response, priorities include establishing inter-organizational networks16–20 with CBOs and FBOs, as they are integral partners for building resilient communities.9,20,21 Yet, LHDs may not always value these linkages or even be able to sustain them due to limited resources or mandates.20–22

Despite calls for cultivating inter-organizational relationships with CBOs and FBOs on the part of LHDs for disaster preparedness and community resilience,22–26 only a few empirical studies describe the pragmatics of fostering such linkages.21,22,27–34 In a study of California LHDs, Lurie et al. found that partnerships with CBOs were often not the norm in disaster and bioterrorism response.21 Mays et al. noted that while more than 75% of LHDs reported having communication networks with CBOs, the media, and the public, only 46% of LHDs dedicated time to maintaining these networks, and only 24% felt their efforts were useful.22 Several studies also have examined the link between the structure and strength of inter-organizational social network ties and effective disaster response.29,30

Moreover, many of the same obstacles to and facilitators for organizational linkages in other areas of public health may apply here. Lerner and colleagues examined a convenience sample of seven “model communities,” defined as communities that have good working relationships among public health and emergency services agencies, such as fire department, law enforcement, and emergency medical services. Important elements for building linkages included holding regularly scheduled meetings; developing response plans together that meet unique local circumstances; working together daily on disaster- and non-disaster-related activities; and having a strong leader driving the collaboration, shared resources, and leveraged funding to accomplish goals.31 Another relevant study of linkages between health centers and community emergency preparedness and response planning initiatives identified several health center-level demographic and experiential factors associated with linkages, including rural location, prior disaster experiences, and high perceived risk for disasters. Barriers to linkages in this study included staff limitations and time restraints, low funding, the potential role of the health center not being understood by emergency planners, and a lack of strong leadership.32 These findings have been confirmed by a more recent study conducted in Los Angeles33 as well as several national studies.34,35

We addressed the issue of what LHDs do with their organizational partners to have functional ties for disaster preparedness and support, with an emphasis on frequency of activities rather than strength of relationships. We named the project the Assessment for Disaster Engagement with Partners Tool (ADEPT) and developed scales based on extensive formative research as well as organizational theory, suggesting that inter-organizational coordination meets needs that individual organizations cannot meet alone.36–38 Coordination involves integrating, linking, or otherwise bringing together various aspects of an organization (e.g., people and departments) or a group of organizations for information exchange and/or resources to accomplish common goals associated with beneficial outcomes,36 either through formal coordination programming39,40 or less formal feedback coordination.39,41

ADEPT was also informed by emerging ideas about public health systems as proposed by the Institute of Medicine,18 which considers LHDs to be part of a larger public health system. These ideas also resonate with emerging directives from the federal government that are now reframing disaster preparedness and response as community disaster resilience.9,16–20,42 A central facet of this approach is mobilizing or engaging communities and their organizations and leaders in partnerships with nongovernmental agencies prior to disasters to assure coordinated and broad-reaching approaches in the face of disasters. Finally, ADEPT items also correspond to disaster preparedness capabilities for health departments as articulated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, specifically capability 1 (i.e., community preparedness) and functions 2, 3, and 4, all of which entail community engagement.19

METHODS

Formative research

After an extensive literature review, we conducted a modified environmental scan of websites of organizations (i.e., CBOs and FBOs) that are active in disasters. We used lists of LHDs that are members of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (-NACCHO) to generate samples for our formative research. The purposive sample of key informants from our NACCHO and CBO/FBO lists included representatives from a variety of organizational types, sizes, missions, levels and types of activity, and jurisdictional characteristics. We then conducted qualitative, semi-structured interviews to finalize the conceptual development of survey items that comprise the multidimensional ADEPT scales for inter-organizational community engagement. We conducted one set of qualitative interviews with local and regional health department disaster coordinators (n=13) and a second set of interviews with staff of local and regional CBOs and FBOs (n=20) for whom disaster and emergency work was part of their mission.35 We conducted key informant interviews by telephone using a recruitment and data collection process approved by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Institutional Review Board.

Findings from key informant interviews provided insight into the type of organizational, training, and staff and resource constraints and facilitators LHDs and CBOs/FBOs face when attempting to create and sustain ongoing partnerships for disasters. Additionally, based on both real and hypothetical scenarios regarding disasters described during these interviews, we elicited information about the types of activities these organizations were conducting that enabled them to have successful inter-organizational partnerships in support of disaster preparedness and response.35

Based on an analysis of key informant interviews, supporting literature, an environmental scan, and the extensive organizational experience and input of both the investigative team and our Advisory Board, we came up with scale items and dimensions in an iterative process. The Advisory Board members included 12 health professionals and leaders from academic institutions and public health organizations who have worked in communities in the area of disaster preparedness and response and, more broadly, community development. The four domains or dimensions of activities encompassed communication outreach, resource mobilization, organizational capacity building for disasters, and partnership development and maintenance. Following is a brief description of each domain.

Communication outreach and disaster coordination.

This domain encompasses a very common set of activities carried out with CBOs and FBOs by LHDs for disaster preparedness and response, comprising the creation, distribution, and promotion of disaster information materials and resources. Whether through in-person sessions, community events, print materials, online methods, organized campaigns, or warning systems, working with CBOs and FBOs is one way to distribute or amplify many forms of disaster communication.43,44

Resource mobilization for disasters.

Often, health departments or other governmental agencies do not have the space, personnel, or goods/services to distribute to people, especially those in hard-to-reach communities, before, during, and after disasters. A number of studies, as well as our own findings, suggest that CBOs and FBOs often serve as organizational extenders of services, space, volunteers, and resources for communities in disasters.2,13,15,27,28,45

Organizational capacity building for disasters.

This set of activities resonates with what some call business continuity planning for disasters. It suggests that as participants in creating resilient communities, CBOs and FBOs must themselves become disaster prepared—creating plans, gaining competencies, stocking supplies, and training personnel and members—so that in the event of a disaster, those assets can be used to help members, clients, or other constituents.20,27,28,45,46

Partnership development and maintenance for disasters.

A final set of inter-organizational activities integral to the process of engaging with local organizations in disasters is linked to general activities that promote and sustain meaningful inter-organizational linkages or partnerships with a disaster focus. These linkages are key in community-based planning to develop and enact community-wide preparedness and response plans, participate in community drills, and ensure ongoing coordination and communication during an event.20,29–32,45,46

Domain item development

Using the four domains that emerged from our formative research, we developed a questionnaire to assess the frequency with which LHDs undertake activities in each domain in collaboration with CBOs/FBOs, referred to as the ADEPT scale. Item domains are seen to cut across characteristics of LHDs regardless of jurisdiction type and size. Some of the items were created de novo based on our formative research, and some were adapted from literature review findings of existing partnership and collaboration development materials. Generally, we attempted to create items that reflected the most common types of activities that might be enacted within these “generic” domains of inter-organizational engagement, defined as the types of things that all agencies do for partnership development. Survey items were also subject to external review by Advisory Board members and subject-matter experts.

Psychometric and statistical analysis

To describe the validity and reliability of ADEPT scale domains, we conducted a national survey of disaster preparedness coordinators at LHDs (n=273) from August through December 2011. Using the NACCHO database of 2,864 LHDs, we applied a probability-proportional-to-size sampling design to generate a stratified random sample of 750 LHDs that reflects the national distribution of large (>250,000), medium (25,000–250,000), and small (<25,000) populations.47

Survey data were collected from disaster preparedness coordinators at LHDs using an online data collection system. All respondents filled out UCLA Institutional Review Board informed consent forms. The survey included the ADEPT items as well as items concerning organizational, jurisdictional, and personal characteristics. Survey completion took an average of 30 minutes. Initially, there were 25 Likert scale items for the four conceptualized domains. To create a more efficient instrument, we pared items to 15 without sacrificing internal consistency, item discriminability, or variance accounted for in the factor analysis.

We analyzed all of our items using Exploratory Principal Components Factor Analysis with Varimax rotation. We performed the analysis multiple times, varying the number of factors fitted to investigate the optimal number of factors to fit. We considered the following when determining the optimal number of factors: total proportion of the variance accounted for, factor eigenvalues, scree plot (for graphing the eigenvalue against the factor number, giving an idea of which factors account for the variance explained), factor loading patterns, item clustering patterns, and face validity. We used classical test theory approaches to evaluate the psychometric properties of the multidimensional measure.48,49

We also assessed measures for internal consistency reliability or the pattern of inter-item correlations within each factor using Cronbach's alpha.50 We measured an item's internal consistency by the average inter-item correlation (i.e., the average pairwise correlation of an item with all other items). We measured an item's discriminability by the item total correlation (i.e., the item's correlation with the sum of all other items). We evaluated item reliability by measuring the difference between the factor's reliability and the factor's reliability with the item removed. Items presenting substantial consistency or discriminability differences, an increase in reliability when removed, or diminished factor loading values across all factors were identified as poorly performing items and were removed. We performed all statistical analyses using SAS® version 9.2.51

RESULTS

In the study sample of disaster preparedness coordinators interviewed (n=273), the jurisdictional size of health departments reflected national distributions, with approximately 18.5% of respondents from small LHDs (<25,000 people served) and 13.3% of respondents from larger LHDs (>250,000 people served) (data not shown). Despite a low response rate (42%), due in part to lack of information about disaster coordinators in LHDs—particularly of medium-sized populations—our final study sample did reflect the distribution jurisdiction size, with most of the sample from medium or large jurisdictions, as described elsewhere.47 Approximately 54% of those surveyed worked more than half-time in emergency and disaster preparedness, and 58% of respondents had worked in emergency and disaster preparedness for >6 years. Women comprised 67% of the sample, and 55% of respondents were 45–65 years of age (data not shown).

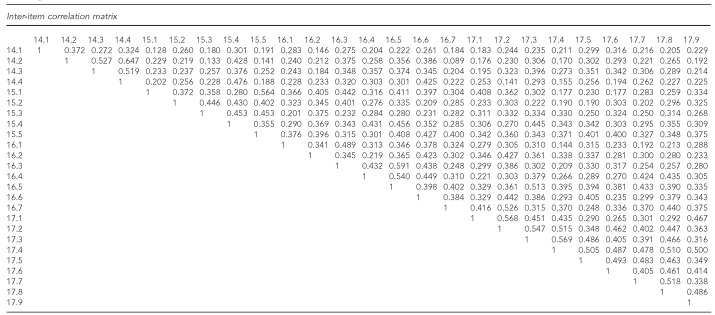

Prior to factor analysis, we also created Pearson's correlations on all 25 items and found that correlations had moderate to good strength and also suggested dimensional structure we had posited (Figure).

Figure.

Inter-item correlation matrix for ADEPT questionnaire items among a national sample of LHD disaster preparedness coordinators (n=273): Los Angeles, California, 2011a

aNumbers represent original survey item numbers.

ADEPT = Assessment for Disaster Engagement with Partners Tool

LHD = local health department

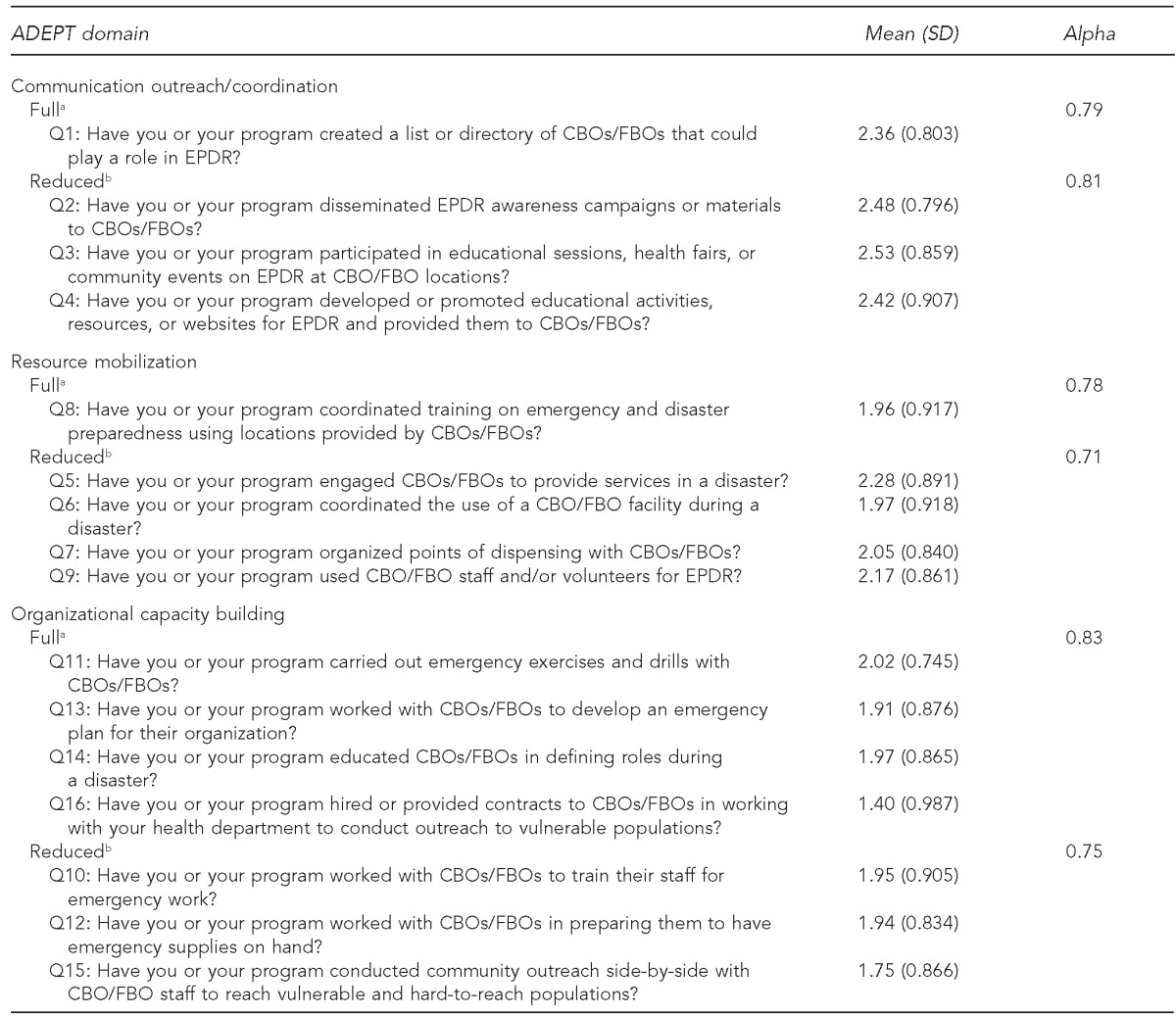

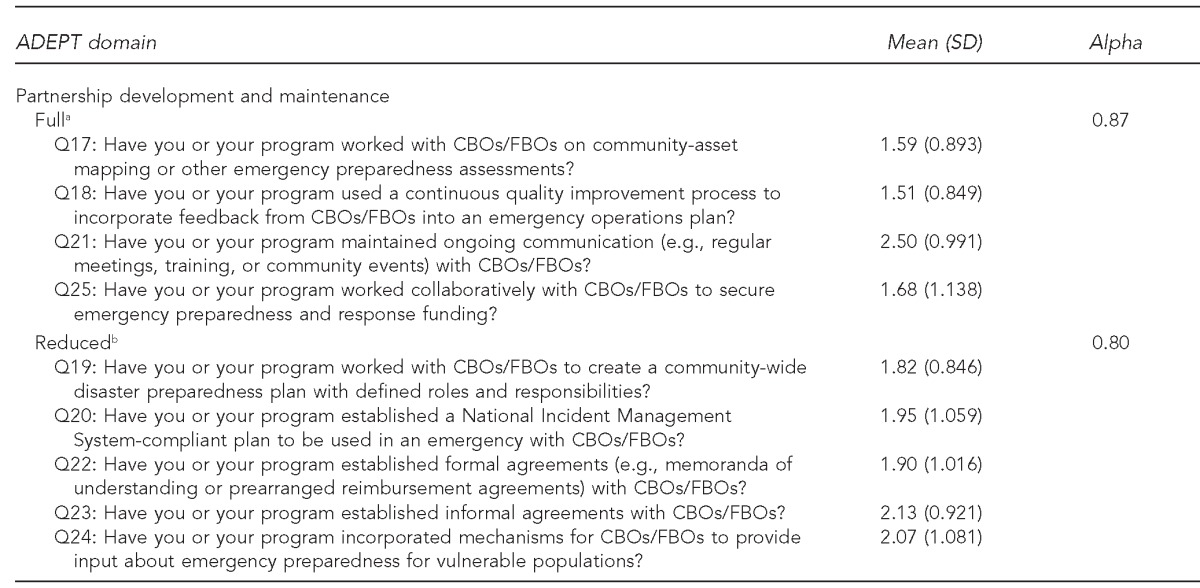

Psychometric measurements for the 15-item scale showed a robust Cronbach's alpha (0.89) across all items (Table 1). For the four domains conceptualized in the reduced 15-item scale, the alphas ranged from 0.71 to 0.81. Domains with the strongest alphas were communication outreach and coordination (alpha = 0.81) and partnership development and maintenance (alpha = 0.80). Resource mobilization, the domain with the lowest alpha (0.71), was possibly the result of more variation in the types of resources considered when responding to items for this type of activity. Both item consistency and discriminability measures suggest that the items within each domain or factor are measuring the same underlying construct. All items exhibited a moderate degree of consistency (average inter-item correlations ranging from 0.41 to 0.61) and discriminability (item total correlations ranging from 0.50 to 0.69) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Internal consistency reliability of ADEPT domains measured among a national sample of LHD disaster preparedness coordinators (Cronbach's alpha = 0.89): Los Angeles, California, 2011

a25-item scale

b15-item scale

ADEPT = Assessment for Disaster Engagement with Partners Tool

LHD = local health department

SD = standard deviation

Q = question

CBO = community-based organization

FBO = faith-based organization

EPDR = emergency preparedness and disaster response

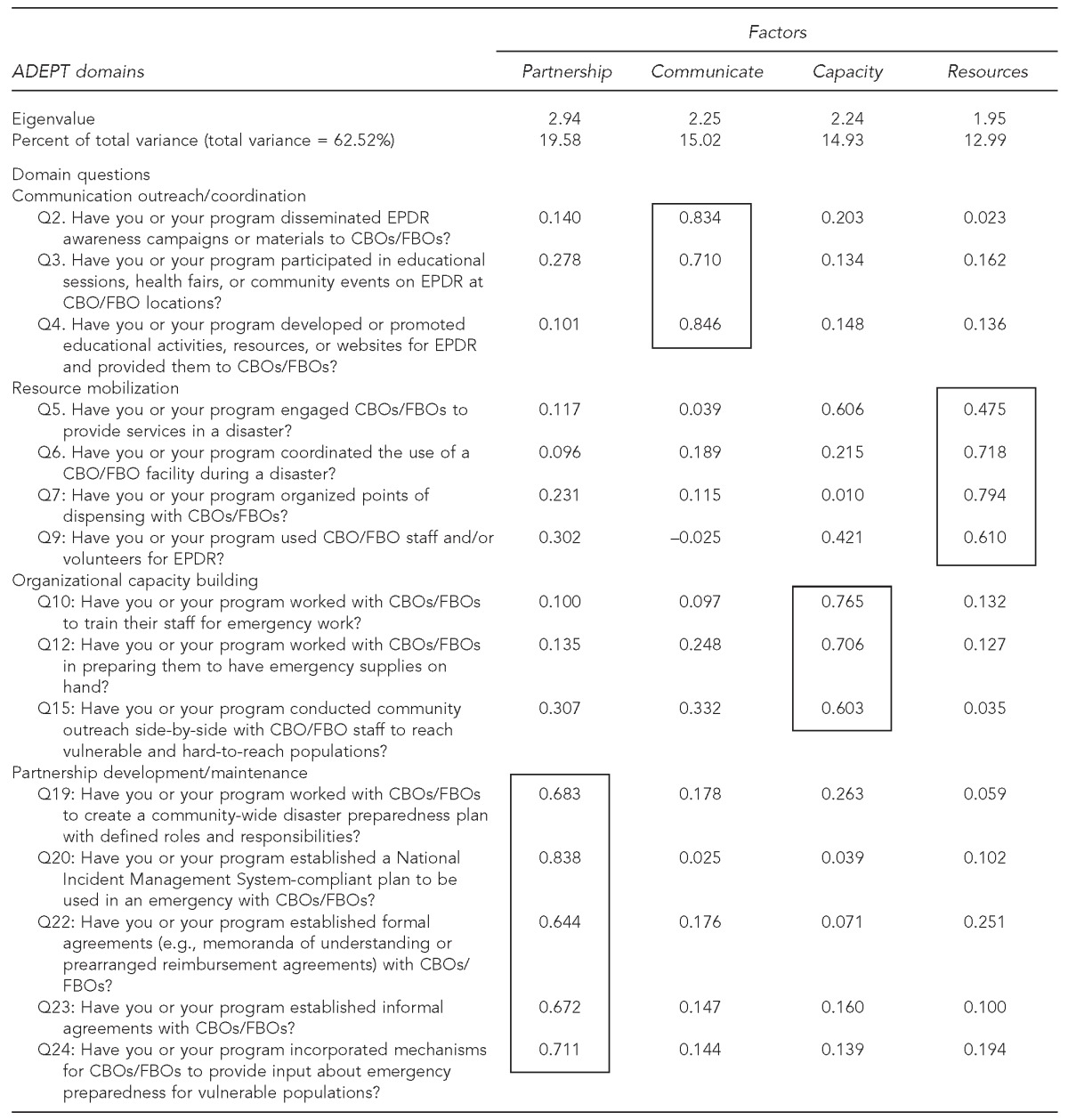

As shown in Table 2, factor analysis results suggest that the data are parsimoniously described by the four-factor model based on factor loading and item clustering patterns. For the four-factors solution, 62.5% of the variance was accounted for, and the rotated factor matrix (Varimax) showed all factor eigenvalues to be >1 with three factors >2. Here, as in the results for internal consistency reliability, the highest factor scores and the most variance accounted for were for partnership development/maintenance (19.6%) and communication outreach/coordination (15.0%). For organizational capacity building, 14.9% of the variance was accounted for, while only 13.0% of the variance was accounted for in the resource mobilization domain.

Table 2.

Exploratory principal components factor analysis results and factor scores for ADEPT among a national sample of LHD disaster preparedness coordinators (n=273): Los Angeles, California, 2011a

Boxes indicate items with similar factor scores.

ADEPT = Assessment for Disaster Engagement with Partners Tool

LHD = local health department

Q = question

EPDR = emergency preparedness and disaster response

CBO = community-based organization

FBO = faith-based organization

DISCUSSION

This study capitalized on calls to operationalize public health systems, with particular emphasis on the interface between LHDs and CBOs/FBOs.18 We based our ADEPT scale on the frequency of activities that LHD disaster preparedness personnel say they conduct to achieve functional linkages with CBOs and FBOs for emergency preparedness and disaster response. Items could also be conceptualized as performance indicators, as they are conducted as part of a disaster coordinator's professional role.

Numerous studies have made a strong case for the importance of inter-organizational linkages to increase community disaster resilience.28–34 However, studies reviewed often present the activities undertaken by organizations in support of disaster preparedness as disparate activities rather than interrelated sets of activities, as we have attempted to do in this study.

In the development of our ADEPT scale, we followed classical measurement theory, which promotes the ideas of conceptual themes or domains of action and cognition, which are then operationalized and measured. In that schema, operationalized items refer to a subset or sample of all the potential items that could be used to measure that construct.50 By organizing activities that support community disaster resilience in this manner, we devised a valid psychometric scale so that collection of this information can be replicated, standardized, and better documented across organizations and contexts.

It should also be noted that we collected survey data using a 25-item scale that had high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.92) and factor analysis results that also supported the same four-factor model. The impetus behind reducing the number of items from 25 to 15 was mainly due to the feasibility of its implementation rather than statistical outcomes, as a 25-item scale is unwieldy, especially in practice-based contexts. However, the 25-item scale can still be used in research.

Limitations and strengths

This study was subject to several limitations. One limitation was a less-than-optimal survey response rate; however, the response rate had a minimal impact on the validity of study findings as regards instrument development. Another limitation was the frame of measure. We asked about the frequency of activities performed from the perspective of the LHD disaster preparedness coordinator, but the question could also have been asked from the perspective of a CBO/FBO staff person, health or emergency organization, school, or business, and there could be more emphasis on response rather than preparedness. Finally, we did not include many explicit questions about disaster drills and exercises. Each of the four types of activities we outlined could also be important components of community-based drills and exercises.

A strength of our multidimensional ADEPT measure was the compatibility between the content of the items and the context of their use. There is nothing as practical as a good theory, and the items in our measure push the field toward considering underlying theories that support notions of organizational behaviors and competencies or capabilities regarding disaster preparedness and response.19 While social networking tools are available to assess the strength of inter-organizational linkages for disasters,20,30 fewer studies have assessed what is done in support of those linkages or how those linkages and associated activities potentially change disaster outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Development of this type of assessment tool can allow LHDs and especially their disaster coordinators to systematically assess how important their participation in these sets of activities is for their organizational mission and identify deficits. Moreover, if scale items can also be understood as a measure of organizational performance, they may also be used in evaluation models that attempt to assess outcomes.52 Participation by an LHD in specific ADEPT activity sets may be used to improve efforts for disaster readiness and response. These dimensions can also be incorporated into drills and exercises. Finally, further research could test whether or not these indicators predict community disaster recovery or identify those factors that cause some communities to be more resilient in disasters.

Footnotes

The work described in this article was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Los Angeles. This work was supported by a Preparedness and Emergency Response Research grant #1P01TP00030301 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drabek TE, Boggs KS. Families in disaster: reaction and relatives. J Marriage Family. 1986;30:443–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards ML. Social location and self-protective behavior: implications for earthquake preparedness. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 1993;11:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fothergill A, Maestas EG, Darlington JD. Race, ethnicity and disasters in the United States: a review of the literature. Disasters. 1999;23:156–73. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tierney KJ, Lindell MK, Perry RW. Washington: Joseph Henry Press; 2001. Facing the unexpected: disaster preparedness and response in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass TA, Schoch-Spana M. Bioterrorism and the people: how to vaccinate a city against panic. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:217–23. doi: 10.1086/338711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waugh WL, Jr, Streib G. Collaboration and leadership for effective emergency management. Public Admin Rev. 2006;66(Suppl 1):131–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenman DP, Cordasco KM, Asch S, Golden JF, Glik D. Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(Suppl 1):S109–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wray RJ, Becker SM, Henderson N, Glik D, Jupka K, Middleton S, et al. Communicating with the public about emerging health threats: lessons from the CDC-ASPH Pre-Event Message Development Project. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:2214–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.107102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapucu N, Hawkins CV, Rivera FI, editors. New York: Routledge; 2013. Disaster resiliency: interdisciplinary perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutton J. Beyond September 11th: an account of post-disaster research. Boulder (CO): University of Colorado; 2003. A complex organizational adaptation to the World Trade Center disaster: an analysis of faith-based organizations. Natural Hazards Research Applications Information Center, Public Entity Risk Institute, and Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems; pp. 405–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeley K. Foner N. Wounded city: the social impact of 9/11. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2005. The psychological treatment of trauma and the trauma of psychological treatment: talking to therapists about 9-11; pp. 263–92. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapucu N. Public non-profit partnerships for collective action in dynamic contexts of emergencies. Public Admin. 2006;84:205–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapucu N. Collaborative emergency management: better community organising, better public preparedness and response. Disasters. 2008;32:239–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes MD, Hanson CL, Novilla LM, Meacham AT, McIntyre E, Erickson BC. Analysis of media agenda setting during and after Hurricane Katrina: implications for emergency preparedness, disaster response, and disaster policy. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:604–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pant AT, Kirsch TD, Subbaro IR, Hsieh YH, Vu A. Faith-based organizations and sustainable sheltering operations in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina: implications for informal network utilization. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:48–54. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federal Emergency Management Agency (US) Washington: Department of Homeland Security (US); 2011. National disaster recovery framework: strengthening disaster recovery for the nation. Also available from: URL: http://www.fema.gov/pdf/recoveryframe work/ndrf.pdf [cited 2014 Mar 28] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Washington: HHS; 2009. National health security strategy of the United States of America. Also available from: URL: http://www.phe.gov/preparedness/planning/authority/nhss/strategy/documents/nhss-final.pdf [cited 2014 Mar 28] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academies Press; 2008. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Public health preparedness capabilities: national standards for state and local planning. 2011. [cited 2014 Mar 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/capabilities.

- 20.Chandra A, Acosta J, Stern S, Uscher-Pines L, Williams MV, Yeung D, et al. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2011. Building community resilience to disasters: a way forward to enhance national health security. Also available from: URL: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2011/RAND_TR915.pdf [cited 2014 Mar 28] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lurie N, Burciaga Valdez R, Wasserman J, Stoto MA, Myers S, Molander RC, et al. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2004. Public health preparedness in California: lessons learned from seven health jurisdictions. Also available from: URL: http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR181.html [cited 2014 Mar 28] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mays GP, Halverson PK, Baker EL, Stevens R, Vann JJ. Availability and perceived effectiveness of public health activities in the nation's most populous communities. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1019–26. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell JA, Baker EL. The essential services of public health. Leadership Public Health. 1994;3:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Handler A, Issel M, Turnock B. A conceptual framework to measure performance of the public health system. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1235–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker EL, Jr, Koplan JP. Strengthening the nation's public health infrastructure: historic challenge, unprecedented opportunity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:15–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson C, Lurie N, Wasserman J, Zakowski S. Conceptualizing and defining public health emergency preparedness. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(Suppl 1):S9–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auerswald PE, Branscomb LM, La Porte TM, Michel-Kerjan EO, editors. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. Seeds of disaster, roots of response: how private action can reduce public vulnerability. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abou-bakr AJ. Washington: Georgetown University Press; 2013. Managing disasters through public-private partnerships. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapacu N. Inter-organizational coordination in dynamic context: networks in emergency management. Connections. 2005;26:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varda DM, Chandra A, Stern SA, Lurie N. Core dimensions of connectivity in public health collaboratives. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14:E1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333889.60517.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerner EB, Cronin M, Schwartz RB, Sanddal TL, Sasser SM, Czapranski T, et al. Linking public health and the emergency care community: 7 model communities. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1:142–5. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181577238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wineman NV, Braun BI, Barbera JA, Loeb JM. Assessing the integration of health center and community emergency preparedness and response planning. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2007;1:96–105. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318158d6ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandra A, Williams M, Plough A, Stayton A, Wells KB, Horta M, et al. Getting actionable about community resilience: the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience project. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1181–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoch-Spana M, Sell TK, Morhard R. Local health department capacity for community engagement and its implications for disaster resilience. Biosecur Bioterror. 2013;11:118–29. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2013.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stajura M, Glik D, Eisenman D, Prelip M, Martel A, Sammartinova J. Perspectives of community- and faith-based organizations about partnering with local health departments for disasters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:2293–311. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9072293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longest BB, Young GT. Coordination and communication. In: Shortell SM, Kaluzny AD, editors. Health care management: organization design and behavior. 4th ed. Albany (NY): Delmar; 2000. pp. 210–43. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banaszack-Hall J, Allen S, Mor V, Schott T. Organizational characteristics associated with agency position in community care networks. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39:368–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mays GP, Halverson PK, Kaluzny AD. Collaboration to improve community health: trends and alternative models. J Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:518–40. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.March JG, Simon HA. Organizations. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL, Koenig R., Jr Determinants of coordination modes within organizations. Am Soc Rev. 1976;41:322–38. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boland JM, Wilson JV. Three faces of integrative coordination: a model of inter-organizational relations in community-based health and human services. Health Serv Res. 1994;29:341–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waugh WL Jr, Tierney KJ, editors. Emergency management: principles and practice for local government. 2nd ed. Washington: ICMA Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahner SJ, Corrado SM. Local health department partnerships with faith-based organizations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:258–65. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glik DC. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:33–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egan MJ, Tischler GH. The national voluntary organizations active in disaster relief and disaster assistance missions: an approach to better collaboration with the public sector in post-disaster operations. Risk, Hazards & Crisis Public Policy. 2010;1:63–96. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Acosta JD, Chandra A, Ringel JS. Nongovernmental resources to support disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:348–53. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sammartinova J, Glik D, Prelip M, Martel A, Stajura M, Eisenman D. The long and winding road: finding disaster preparedness coordinators in a national sample of local public health departments. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:364–6. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. PARE. 2005;10:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker FB. The basics of item response theory. 2nd ed. Washington: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 51.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.3. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossi PH, Lipsey MW, Freeman HE. Evaluation: a systematic approach. 7th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Ltd.; 2004. [Google Scholar]