Abstract

We describe the case of a 53-year-old man who presented with abdominal pain, diarrhoea and hypomagnesaemia. The hypomagnesaemia proved to be due to gastrointestinal loss as urinary fractional excretion was very low, suggesting non-renal loss. Common causes were discarded and the hypomagnesaemia was attributed to chronic use of the proton pump inhibitor, omeprazole. As such, omeprazole was discontinued and an H2 blocker was given. Several days later the patient presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. CT scan demonstrated marked enlargement of the duodenum and proximal jejunum, and abnormal thickening and enhancement of the bowel wall. Urgent oesophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed coffee-ground and bloody contents in the distal oesophagus and stomach, and numerous ulcers along the duodenum and jejunum. A positron emission tomography-CT scan using GA 68-DOTANOC demonstrated increased uptake in the gastroduodenum junction, suggesting a neuroendocrine tumour. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed and tumour cells stained positive for gastrin, confirming the tentative diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Background

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are used to treat numerous symptoms and ailments associated with gastric acid secretion. Their high potency, coupled with a minor side effects profile, has made them very popular. However, long-term treatment with PPIs is linked to several adverse effects. One such effect, though not common, is hypomagnesaemia.

As this case brings to light two uncommon but potentially fatal complications of long-term treatment with PPIs, we believe it to be highly educational to the practising physician.

Case presentation

A 53 year-old man, who presented to our hospital 5 years prior to the current admission with abdominal pain and diarrhoea. An abdominal CT scan suggested an upper gastrointestinal inflammatory condition. He was treated conservatively with intravenous fluids, antibiotics and oral omeprazole with resolution of his symptoms. The patient was discharged with a recommendation to continue treatment with omeprazole and to have an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) performed.

Six months later, an EGD was performed while the patient was being treated with omeprazole. The EGD revealed an ulcer in the third part of the duodenum. A higher dose of omeprazole was prescribed and due to the unusual location of the ulcer fasting gastrin level was measured, which was found to be slightly elevated (207 pg/mL; normal 25–108 pg/mL). No further work up was performed at that time.

Five months prior to the current admission, the patient was admitted to our department with acute-onset abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea. His laboratory tests were notable for severe hypomagnesaemia and hypokalaemia, both of which normalised after intravenous supplementation (table 1). The patient was given a diagnosis of infectious gastroenteritis and was discharged after resolution of his symptoms with a recommendation to continue treatment with oral magnesium and potassium supplements.

Table 1.

Laboratory data

| Variable | Normal | 5 years earlier | 5 months earlier |

Current admission |

Last admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | Discharge | Admission | 4th day | ||||

| Blood | |||||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13–17 | 13.6 | 15.5 | 14.7 | 13.2 | 11.3 | |

| White cell count (10³/μL) | 4–10.8 | 13 | 17.2 | 8.67 | 19.5 | 15.12 | |

| Platelets (10³/μL) | 130–350 | 599 | 367 | 295 | 357 | 338 | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 133–145 | 137 | 134 | 141 | 137 | 145 | 138 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.5–5.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 5 | 3 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.5–10.8 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 8.2 | |

| Inorganic phosphate (mg/dL) | 2.5–4.5 | 3.01 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.6 | ||

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 1.3–2.4 | 1.5 | 0.51 | 1.25 | 1.64 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4–1.3 | 0.71 | 3.3 | 1.99 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 0–20 | 14.2 | 33 | 17 | 27 | 13 | 27 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.4–5 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 2.8 | |||

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6–8.2 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 5.6 | |||

| Blood gases | |||||||

| pH | 7.35–7.45 | 7.47 | 7.43 | 7.41 | 7.39 | ||

| Partial pressure of carbon dioxide (mm Hg) | 33–45 | 46 | 41 | 27.6 | 46 | ||

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 22–26 | 33.5 | 27.7 | 17.6 | 28.4 | ||

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 7.4 | 2.1 | 7.2 | 2.6 | |||

| Ionised magnesium (mmol/L) | 0.45–0.6 | 0.27 | 0.56 | 0.2 | 0.62 | ||

| Ionised calcium (mmol/L) | 1.15–1.35 | 1.15 | 1.18 | 1.1 | 1.33 | ||

| Urine | |||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 90 | ||||||

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 0.47 | ||||||

| 24 h volume (mL) | 1200 | ||||||

In the current admission, the patient was hospitalised due to recurrence of the aforementioned gastrointestinal symptoms. His medical history was notable for obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. He denied smoking or alcohol consumption. Current medications included aspirin, bisoprolol, ramipril, amlodipine, doxazocin, atorvastatin, bizafibrate, insulin glargine, januet (sitagliptin+metformin) and omeprazole along with oral potassium and magnesium supplements.

He denied having any chronic abdominal pain but did mention having loose stools. Interestingly, his laboratory tests demonstrated recurrence of severe hypomagnesaemia and hypokalaemia (table 1) despite their earlier improvement and the continuous consumption of large amounts of oral supplements.

Since the hypokalaemia was assumed to be secondary to hypomagnesaemia, diagnostic evaluation focused on the latter. As described below, this evaluation identified chronic treatment with omeprazole as the most likely cause of hypomagnesaemia and hence the drug was discontinued.

In addition, due to the recurrent nature of the gastrointestinal symptoms, an EGD was performed and demonstrated giant nodular gastric folds. Biopsy samples showed gastric mucosa with foci of mild oedema, one segment with mild foveolar hyperplasia with no evidence of Helicobacter pylori. After consultation with the gastrointestinal services in our hospital, a decision was made to stop treatment with omeprazole and start treatment with a histamine-2 receptor antagonist and perform a follow-up EGD within 2 weeks. The patient was discharged after his gastrointestinal symptoms subsided and the electrolyte abnormalities normalised.

Five days after discharge, the patient returned to the hospital due to severe abdominal pain, continuous vomiting and diarrhoea, and reduced haemoglobin levels.

Investigations

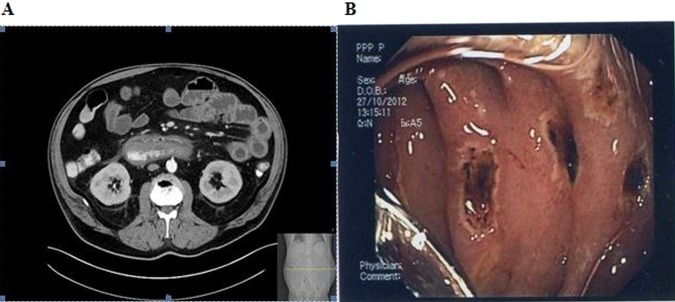

An abdominal CT scan demonstrated marked enlargement of the duodenum and proximal jejunum, abnormal thickening and enhancement of the bowel wall, and inflammatory changes in surrounding fat (figure 1A). An urgent EGD followed and revealed coffee-ground and bloody contents in the distal oesophagus and stomach, numerous ulcers along the duodenum and jejunum and large amounts of intraluminal secretions (figure 1B). Multiple biopsies were performed and therapy with continuous intravenous omeprazole was started.

Figure 1.

(A) CT image showing slight enlargement of the third part of the duodenum with enhanced thickened wall and stranding of the surrounding fat. (B) Diffuse, multiple severe haemorrhagic ulcers in the duodenum and proximal jejunum.

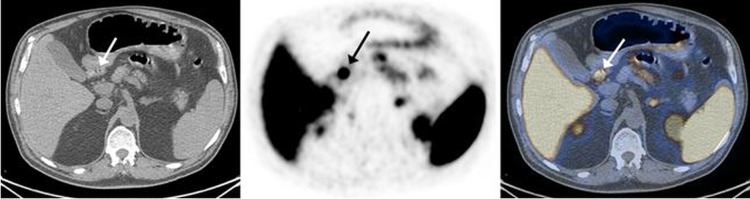

At this point, the presence of a gastrin-secreting tumour was highly suspected and further evaluation was made to verify its existence and identify its anatomical location. Serum gastrin level was measured and found to be only mildly elevated (227 pg/mL). A positron emission tomography-CT scan using GA 68-DOTANOC demonstrated increased uptake in the gastroduodenum junction, a finding suggestive of malignancy of neuroendocrine origin (figure 2).

Figure 2.

GA 68-DOTANOC positron emission tomography (PET)/CT transaxial slices (left, CT; middle, PET; right, fused image) demonstrate a focal tracer uptake in the proximal part of the duodenum (arrows) consistent with a neuroendocrine tumour.

Treatment

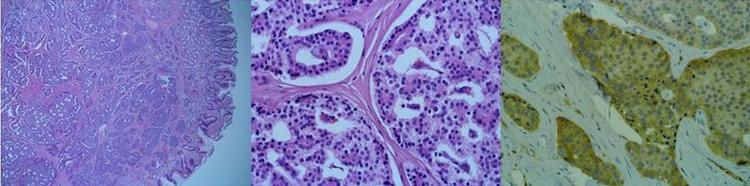

The patient was transferred to the general surgery service and underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure). Pathological examination of tissue specimens identified a small submucosal tumour located in the proximal duodenum. Tumour cells stained positive for gastrin, confirming the tentative diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (figure 3). One of 12 lymph nodes was found to harbour a metastasis.

Figure 3.

A 0.8 cm submucosal tumour was identified (A, ×40). Tumour cells are arranged in broad trabecula and glandular-like structures, and nuclear chromatin has a ‘salt and pepper’ texture (B, ×400). Immunohistochemistry with antigastrin antibody showed positive cytoplasmic staining (C, ×400).

Outcome and follow-up

Unfortunately, the postsurgical course was complicated by the development of an infected intra-abdominal fluid collection. A few days after the collection was aspirated, sudden cardiovascular collapse occurred and the patient died. As an autopsy was not performed, the exact cause of death remains unknown.

Discussion

PPIs are the most potent drugs to inhibit gastric acid secretion. Although relatively safe, a number of adverse effects have been attributed to their chronic consumption and one such recently described effect is hypomagnesaemia.1 This association was described in case reports2 3 as well as observational studies4 5 and was addressed in a safety alert issued by the American Food and Drug Administration.6 PPIs induce hypomagnesaemia by inhibiting the absorption of magnesium from the gastrointestinal tract, possibly by altering the action of TRPM 6/7 channels through which it is absorbed.7

The first step in the evaluation of hypomagnesaemia is to discriminate between gastrointestinal and renal loss as these two organ systems are those through which magnesium is absorbed and eliminated from the body, respectively. In the case described above, two findings pointed towards the gastrointestinal tract as the culprit organ. First, hypomagnesaemia persisted despite the consumption of large doses of oral supplements but yet rapidly corrected when magnesium was given via the intravenous route. Second, a low fractional excretion of magnesium in the urine (0.65%) and a low 24 h excretion of magnesium in the urine (6.4 mg/24 h; table 1) both support an extrarenal cause for this electrolyte abnormality.

Once we recognised that magnesium was lost from the gastrointestinal tract, a search was performed for potential causes. Dietary deficiency was readily discarded since the patient was taking oral supplements. There was no evidence of protracted vomiting or diarrhoea or the existence of a malabsorption state. No laxative drugs were consumed by the patient and the only relevant cause identified was chronic treatment with omeprazole, so it was discontinued.

In addition to their adverse effects, PPIs can also mask the presence of conditions associated with increased gastric acid secretion such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, which describes the constellation of clinical symptoms and signs resulting from the presence of a gastrin-secreting tumour.8 The most common clinical findings are upper abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Most often, the clinical presentation is subtle and diagnosis is markedly delayed after the first clinical symptoms appear.9 This is especially true for patients treated with drugs that interfere and inhibit gastric acid production, such as PPIs. In this group of patients, sudden discontinuation of treatment can result in severe and, at times, even life-threatening complications.10 However, the presence of this syndrome can be suggested by some findings, which include the occurrence of gastric and duodenal ulcers in the absence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug consumption or H. pylori infection, the presence of ulcers in unusual locations, the presence of prominent gastric folds and a family history of upper gastrointestinal ulcer disease. Interestingly, the first three findings were present in our patient and, indeed, the presence of a gastrin-secreting tumour was sought after the first EGD revealed the unusual location of the duodenal ulcer. However, as occurs in most patients diagnosed with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, gastrin levels were not profoundly elevated (<1000 pg/mL), overlapping with levels commonly seen in patients with hypergastrinaemia caused by other aetiologies, one of which is treatment with PPIs.10 Possibly, the mildly elevated gastrin level was attributed to concurrent treatment with omeprazole, resulting in no further work up being carried out at that time.

One might argue that the patient’s magnesium deficiency was caused by the existence of then-unrecognised Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. However, several findings make this possibility highly unlikely. First, the patient's symptoms were episodic with each episode separated from the other by several months and no symptoms in between. Second, the only evident nutritional and mineral deficiency was hypomagnesaemia (and the resultant hypokalaemia), a finding very unlikely to result from excess gastric acid secretion that causes unselective damage to the gastrointestinal tract (table 1). Finally, quite remarkably, magnesium levels were normal when, on his last admission, the patient presented with unremitting vomiting and diarrhoea but without treatment with omeprazole (table 1).

Patients diagnosed with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome can be treated medically, surgically or by a combination of both. As there were no features suggesting the presence of multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 syndrome, the patient was considered as having a sporadic gastrin-secreting tumour and a decision was made to perform a surgical resection of the tumour. This decision is in line with current recommendations from international societies and based on studies demonstrating an increased cure rate and reduced risk of developing liver metastases, which constitute the most important prognostic factors for long-term survival in patients with this tumour.11 The decision to perform a radical resection via the Whipple procedure was made by the surgical team in our hospital believing that, based on their personal experience, it offers the best chances for cure. This approach, although practiced by other surgical teams,12 is not in line with the aforementioned recommendations, which state that a more conservative surgical approach for most patients with a sporadic tumour is favoured, except in special situations in which the Whipple procedure may be preferred.11

Learning points.

Hypomagnesaemia is an important side effect of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

PPI use may mask Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

PPI discontinuation may be dangerous as it unmasks life-threatening Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Dr Zohar Keidar, MD, the Institute of Nuclear Medicine, Rambam Health Care Campus and The Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion, Haifa, Israel. Dr Keidar prepared and edited figure number 2 and its legend. Dr Dov Hershkovitz, MD, the Institute of Pathology, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel. Dr Hershkovitz prepared and edited figure number 3 and its legend. Dr Osnat Gal-Silberschmidt, MD, the Institute of Medical Imaging, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel. Dr Gal-Silberschmidt prepared and edited figure number 1A and its legend. Dr Halim Awadie, MD, the Institute of Gastroenterology, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel. Dr Awadie prepared and edited figure number 1B and its legend.

Footnotes

Contributors: AE and MEN were involved in the conception, defining the aims, and writing and revising the final manuscript. AS was involved in reviewing the manuscript and adding some references. EB was involved in writing and revising the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Abraham NS Proton pump inhibitors: potential adverse effects. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2012;28:615–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein M, McGrath S, Law F. Proton-pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemic hypoparathyroidism. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1834–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoorn EJ, van der Hoek J, de Man RA, et al. . A case series of proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;56:112–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gau JT, Yang YX, Chen R, et al. . Uses of proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:553–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danziger J, William JH, Scott DJ, et al. . Proton-pump inhibitor use is associated with low serum magnesium concentrations. Kidney Int 2013;83:692–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245011.htm Posted 03/02/2011

- 7.Bai JP, Hausman E, Lionberger R, et al. . Modeling and simulation of the effect of proton pump inhibitors on magnesium homeostasis. 1. Oral absorption of magnesium. Mol Pharm 2012;9:3495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison EC, Johnson JA. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a comprehensive review of historical, scientific, and clinical considerations. Curr Probl Surg 2009;46:13–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, et al. . Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Clinical presentation in 261 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:379–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito T, Cadiot G, Jensen RT. Diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: increasingly difficult. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:5495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, et al. . ENETS consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology 2012;95:98–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovinazzo F, Butturini G, Monsellato D, et al. . Lymph node metastasis and recurrences justify an aggressive treatment of gastrinoma. Updat Surg 2013;65:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]