Abstract

Objective

To synthesise the evidence on implementing family involvement in the treatment of patients with psychosis with a focus on barriers, problems and facilitating factors.

Design

Systematic review of studies evaluating the involvement of families in tripartite communication between health professionals, ‘families’ (or other unpaid carers) and adult patients, in a single-family context. A theoretical thematic analysis approach and thematic synthesis were used.

Data sources

A systematic electronic search was carried out in seven databases, using database-specific search strategies and controlled vocabulary. A secondary manual search of grey literature was performed as well as using forwards and backwards snowballing techniques.

Results

A total of 43 studies were included. The majority featured qualitative data (n=42), focused solely on staff perspectives (n=32) and were carried out in the UK (n=23). Facilitating the training and ongoing supervision needs of staff are necessary but not sufficient conditions for a consistent involvement of families. Organisational cultures and paradigms can work to limit family involvement, and effective implementation appears to operate via a whole team coordinated effort at every level of the organisation, supported by strong leadership. Reservations about family involvement regarding power relations, fear of negative outcomes and the need for an exclusive patient–professional relationship may be explored and addressed through mutually trusting relationships.

Conclusions

Implementing family involvement carries additional challenges beyond those generally associated with translating research to practice. Implementation may require a cultural and organisational shift towards working with families. Family work can only be implemented if this is considered a shared goal of all members of a clinical team and/or mental health service, including the leaders of the organisation. This may imply a change in the ethos and practices of clinical teams, as well as the establishment of working routines that facilitate family involvement approaches.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Can inform policies and guidelines on family involvement so that they impact on routine practice.

Is novel in covering a wide range of family involvement practices, highlighting common barriers, problems and facilitating factors.

Synthesises rich qualitative data from professionals, patients and families.

Could not include subgroup and quality analyses, due to the high correspondence between type of family involvement practice and methodology.

May be conceptually limited as extant research has focused on perspectives of staff involved in family work and few studies are available on families’ views.

Background

The process of deinstitutionalisation of mental healthcare in the western world has led to families and others in the community shouldering the psychosocial burden of care and informally adopting the role previously provided by professionals in healthcare services.1–3 The adoption of protected terms such as ‘carer’ in the UK and ‘caregiver’ in the USA is a response to the substantial, yet ‘non-professional’ role that individuals in a close relationship have in supporting a person receiving mental health treatment. The term may include parents, partners, siblings, children, friends or other people significant to the individual: essentially, anyone who provides substantial support without being paid. The term carer can be problematic, being considered by some to have connotations of dependency and of minimising the significance of the relationship.4 Also, many ‘carers’ do not self-identify as such, and consider their caring role as being within the traditional responsibilities expected of them. To avoid confusion when referring to family-directed initiatives, the single term ‘families’ will be adopted throughout this review and broadly applies to a person's social network, not excluding their non-blood relatives.

‘Family involvement’ in mental health services can take different forms, depending on the level of need and availability of services. Generally, it can be conceived on a spectrum from more basic functions to specialised interventions, the minimal level including the provision of general information on the mental health service and assessments. On a more complex and specialised level, services can offer families psychoeducation, consultation, family interventions (FIs) and therapies.5 There are both strong economic and moral imperatives to establish meaningful involvement and true collaborative working between families and health professionals. These are recognised by international government policies and psychiatric guidelines stipulating that families should be supported and actively involved in psychiatric treatment.6–11 Families can encourage engagement with treatment plans, recognise and respond to early warning signs of relapse12 and assist in accessing services during period of crisis.13–15 Family involvement can lead to better outcomes from psychological therapies16 and pharmacological treatments,17 fewer inpatient admissions, shorter inpatient stays and better quality of life reports by patients.18–21

However, despite the vast evidence base for FI22–28 and family psychoeducation,29 research suggests that family involvement is often not implemented in routine mental healthcare. There is an abundance of both quantitative and qualitative studies into experiences of inpatient care reporting that families feel marginalised and distanced from the care planning process. Common themes across international studies indicate that families feel isolated, uninformed, lack a recognised role and are not listened to or taken seriously.1 30–43 Families also commonly report feeling that confidentiality is used by professionals as a way to not share information.39 44 Family Intervention as a treatment approach is startlingly under-implemented, with extremely low numbers of families actually receiving it in clinical services.11 45–47 It is the case that for many, contact between professionals and families remains limited to telephone calls during crisis periods.48

Why is family involvement in treatment so under-applied? There has been much debate about the reasons (eg,22 49–51) and some suggest they are linked to general problems of implementing new evidence-based practices in clinical services.29 Other proposed barriers are more specific to family interventions, such as the danger of increasing burden related to caregiving, role strain, lack of experience and/or interest52 and the complexities of navigating confidentiality.53 Such discussions are largely speculative and reviews of evidence tend to focus on the provision of specific interventions, such as family psychoeducation29 or FI.54 This systematic review aims to assess how the involvement of families is implemented in the treatment of patients with psychosis, taking a broad view of involvement as described above in order to capture the barriers, problems and facilitating factors that operate in practice. In doing so, this may help to better define and implement families’ involvement in psychiatric treatment in the future.

Methods

The full protocol for this systematic review is reported in the online supplementary file 1.

Identifying relevant studies

Computerised databases were searched for eligible studies: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED (via Ovid), BNI and CINAHL (via HILO), Social Sciences Citations Index (via Web of Knowledge) and CDSR, DARE and CENTRAL (via the Cochrane Library). Word groups representing patient diagnosis, intervention and involvement terms and outcome descriptors were combined in several ways. Strategies were adapted for each database, using controlled vocabulary (MeSH, Emtree, Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms) and free text (see online supplementary file 2). The search was last repeated on 1 June 2014.

Publication bias was minimised by including conference papers and book chapters, searching grey literature for dissertations and reports (ETHOS, SIGL) and corresponding with authors to identify further works. Both backward snowballing (from the reference lists of included studies and identified reviews) and forward snowballing (finding citations to the papers) was conducted.

Inclusion procedure

A study was eligible for inclusion if: (1) it was an original collection of data; (2) situated in primary or secondary mental health services; (3) the patient population included people being treated for psychotic disordersi; (4) the intervention involved tripartite communication between health professionals (any), families (unpaid carers) and adult patients, excluding those focused exclusively on professional–family communication, family–family communication or multiple-family groups; and (5) results described barriers, problems and/or facilitating factors in involving families in treatment. No study type was excluded, however only Latin-script languages were able to be translated.

‘Barriers’ were defined as factors that prevented an approach from taking place or limited the scope of it, ‘problems’ referred to issues that emerged when delivering an approach and ‘facilitating factors’ were considered to be any factors that aided implementation or delivery. ‘Family involvement’ was defined inclusively as any process allowing health professionals, families and patients to actively collaborate in treatment, such as in making joint treatment decisions. Studies not reporting clear information on how families were involved in treatment were excluded. Studies into general experiences, opinions, satisfaction or needs were also excluded, unless they related to a clearly described specific involvement in treatment.

Two reviewers (EE and DG) screened all of the titles and collected relevant abstracts. These were screened and then excluded if they did not fit the selection criteria. Studies that seemed to include relevant data or information were retrieved and their full text versions analysed and examined for study eligibility. All final full text choices were confirmed and agreed by both reviewers.

Method of analysis

Data extraction and synthesis was guided by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)'s Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews.55

The included studies used both qualitative and quantitative methods, yet clearly had conceptual overlaps despite reporting results in different formats. Any available quantitative data were usually descriptive, reported in addition to qualitative findings and were largely used to explore existing themes or concepts. It was therefore considered appropriate to transform quantitative findings into qualitative form to systematically identify the main concepts across the studies using thematic analysis.55 56 The use of this method is increasingly being advocated with studies involving data that are quantitative or from mixed methods56–58 to address questions relating to intervention need, appropriateness and acceptability in systematic reviews.59

Data extraction and synthesis

Theoretical Thematic Analysis60 using inductive themes to identify the barriers, problems and facilitating factors of family involvement was used as a framework to explore further themes.

Two non-clinician researchers (EE and AD) independently extracted author interpretations and participant data from the included studies using a piloted data extraction sheet. They then separately allocated the findings to relevant sections of the framework (eg, ‘Barriers according to staff perspectives’) and coded the data within each section. Identified categories (eg, ‘Unsupportive attitudes of managers’) were aggregated into subthemes (eg, ‘Attitudes towards family work’) and finally became grouped under overarching themes (eg, ‘Context: addressing the organisational culture’). These emerging themes were discussed throughout analysis along with a clinician-researcher (DG), and discrepancies were resolved through iterative discussions. Robustness of the synthesis was investigated and themes were checked for completeness. Two clinician-researchers (DG and SP) acted as third party assessors of the final data synthesis.

Results

Included studies

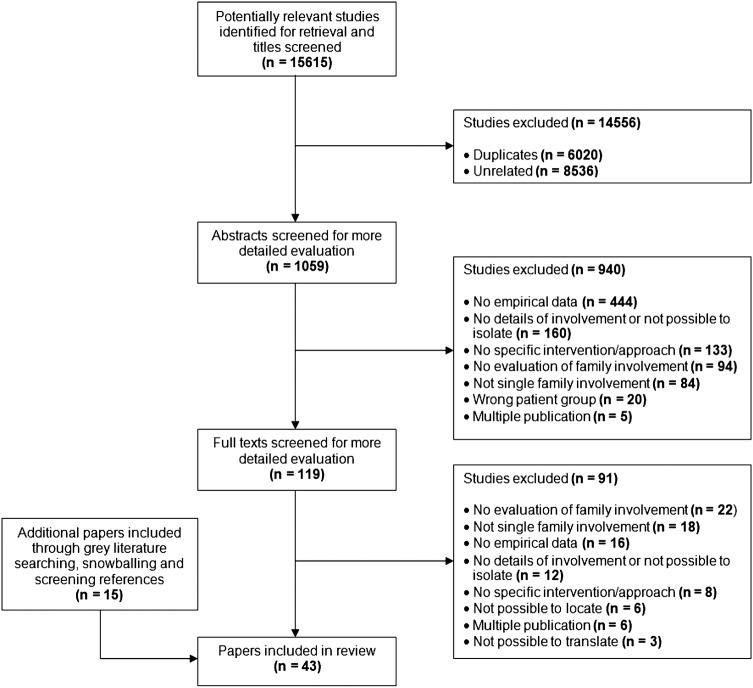

Database searching produced 15 615 titles to screen. After removing duplicates and irrelevant papers, a full text assessment of 119 documents was conducted. Twenty eight publications met our inclusion criteria and second stage searching including grey literature searching, personal correspondence and snowballing techniques led to the further identification and inclusion of 15 articles. This brought the final number of studies to 43. The PRISMA flow chart in figure 1 depicts the identification and exclusion of articles.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for paper selection.

Overview of papers

Forty-two papers were published between 1991 and 2013 and one in 1978. Just over half of the studies were based on UK findings, with the rest from Finland, the USA, Italy, Australia, Canada, Germany, India, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, Greece and Portugal. Mainly, papers reported on experiences of implementing FI approaches (n=33). Typically these followed a similar structure and were broadly modelled on the Behavioural Family Therapy approach61 (see online supplementary file 3 for full study characteristics). This included variations such as ‘Psychosocial Intervention’ and ‘Family Psychoeducation’ that fit the model of an FI. The remainder explored Open Dialogue approaches (n=6), Systemic Psychotherapy (n=3) and one purely Behavioural Therapy programme. The vast majority were cross-sectional studies and 13 were naturalistic evaluations, descriptions or case studies of a service. In all, 37 papers explored staff perspectives, eight papers featured patient perspectives and six featured ‘family’ perspectives. In total, the review included data of 588 professionals, 321 patients and 276 ‘family members’ or ‘families’.

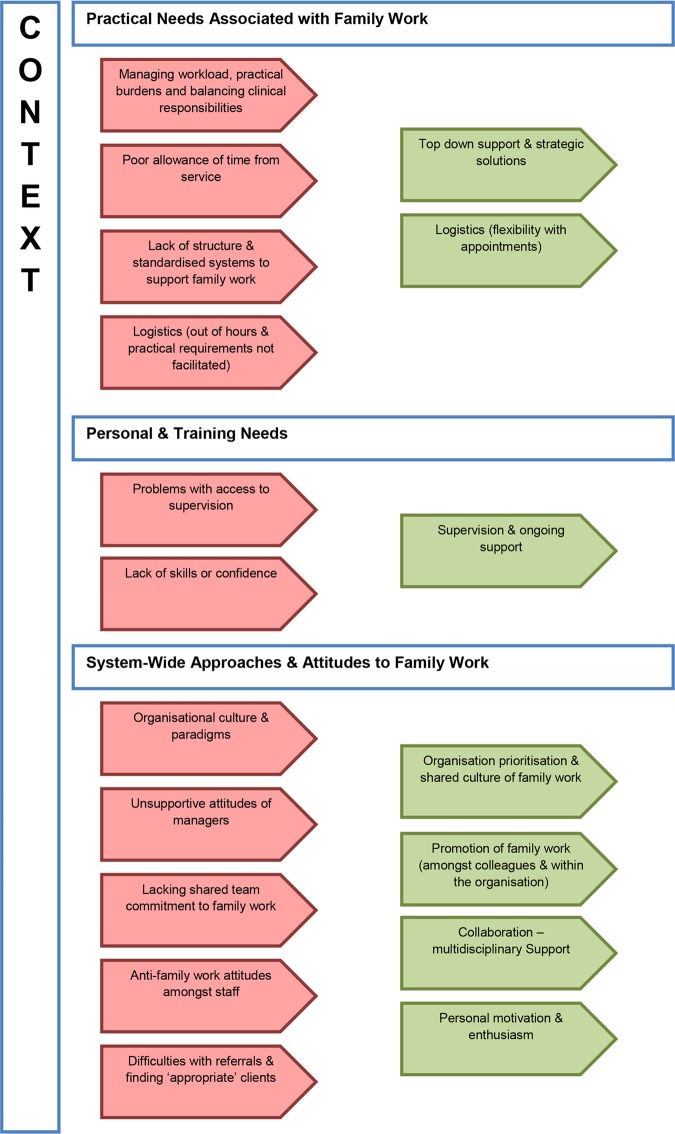

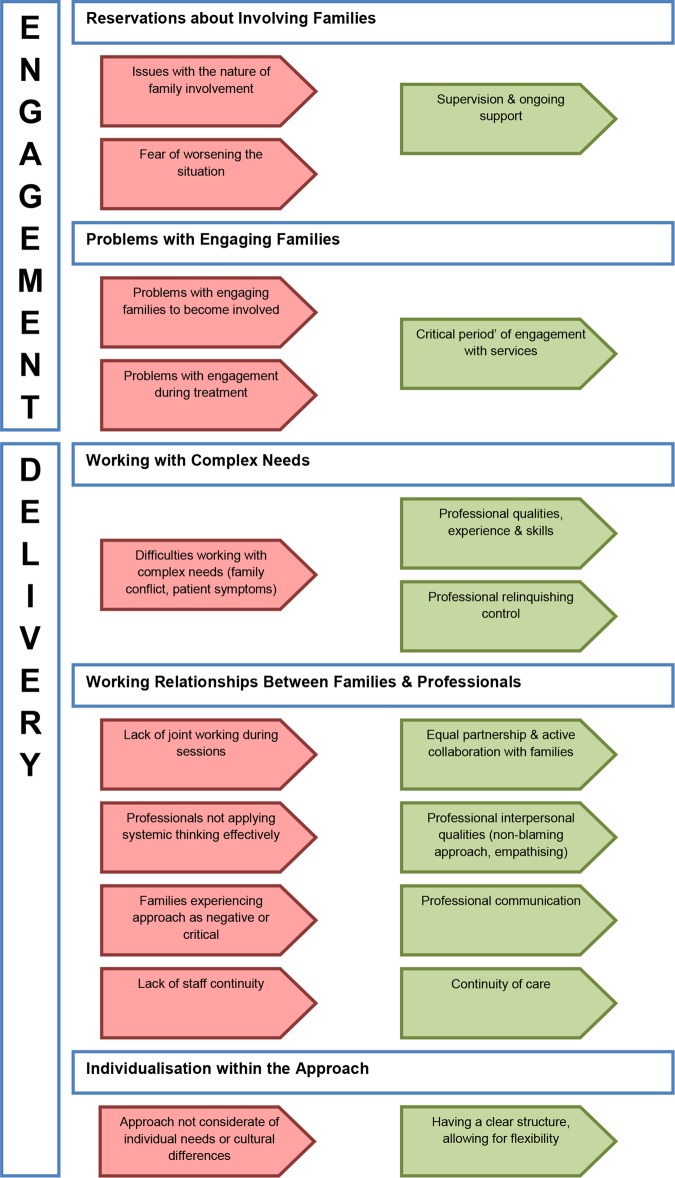

In depth review: synthesis across studies

Figure 2 summarises the final cross-study synthesis: the identified barriers/problems (in red) and facilitating factors (in green) and the themes in which they seemed to be operating. The themes closely relate to temporal sequencing in the process of delivering an intervention: the context, engagement and then delivery. The figure provides a visual representation of the matches and gaps between barriers and facilitating factors related to involving families. This is for the most part conceptual, as barriers and their direct facilitating factors may not have been discussed in the same study. The themes and subthemes are explored in greater detail in the synthesis below, which includes details of problems associated with delivering approaches that involve families as well as barriers and facilitating factors of this work.

Figure 2.

Barriers, problems and facilitating factors related to family work. Summary of themes.

Figure 2.

Continued

Context: addressing the organisational culture

This theme reflects the majority of the findings, mostly from staff perspectives. Their experience of implementing family work could be characterised as working in relative isolation in a system where colleagues and managers did not value and prioritise family involvement or were openly hostile to it. With multidisciplinary cooperation and working systems not in place, practical burdens associated with family work were sometimes insurmountable. Mirroring this, factors that enabled family involvement to take place were related to top-down management support, prioritisation and changing the culture of family work.

Organisational attitudes and paradigms

This subtheme covered general attitudes, such as family involvement not being valued at organisational and team level but also highlighted possible entrenched reasons for this. For example, individualistic, biological paradigms made family work seem secondary or optional62–64 and staff found it difficult to adopt a collaborative stance, relinquishing the role of didactic problem solver.63 In some cases, it appeared that historical negative attitudes towards families had not shifted.62 64 Attitudes against family work described among colleagues ranged from resistance towards the approaches63 65–68 to well-intentioned but complicating beliefs regarding clinicians’ duty towards the patient.64 69 70 Facilitating factors related not only to specific strategies but to an overall shared culture and prioritisation of family work,64 71 72 shifting attitudes towards viewing the family as equal partners71 73 and thinking more systemically about problems.71 74

Practical needs associated with family work

Overwhelmingly, staff reported on the practical burdens of family work: that it requires time, resources and funding and is difficult to integrate with other clinical casework,62 64–70 73 75–87 particularly in areas with high demands and clinical crises.73 82 83 Specific needs reported for family work included flexible hours64 65 67 70 80 82–84 87–90 and the accommodation of family requirements such as childcare facilities80 or home visits.82 89 91 A lack of systems and structure for carrying out and recording family work was also reported as a barrier to implementation and problem during delivery.63 87 92 This included a lack of coordination between inpatient and outpatient care.62 These issues were compounded by reports of services and managers not making time allowances for family work, for example, not providing time in lieu for out of hours work,64 65 77 83 84 or obstructing time use, for example, by refusing the release of staff for training.63

Management culture

Commonly, staff reported on the unsupportive attitudes of managers and colleagues as limiting the implementation of family involvement.63 64 66 77–79 87 92 93 This ranged from a ‘management culture of benign neglect rather than of active opposition’93 to overt challenges such as not respecting ring-fenced time for family work.87 The strongest facilitator seemed to be that of strong leadership through senior management support and developing strategic solutions. This ‘sanctioned’ family work, giving it core priority status within the service,64 and could facilitate specific powerful initiatives such as writing family work into business plans, policies and job descriptions of all staff.63 79 Further endorsement came from providing flexible hours, creating new staff roles and financial provision.63 73 79 94 The value emerged of having regular multidisciplinary meetings to address team-specific needs72 78 79 88 and developing strategies that prioritised family work and made it a part of regular clinical practice.63 72 73 79 88 94 This included having routine assessment of all families, asking clinicians about families when reviewing caseloads and providing regular feedback of family data to teams and managers.63 94

Training needs

Staff also reported on lacking access to adequate supervision and training62 63 65 66 83 86 87 92 as barriers to implementation. This may link with reports of staff lacking skills or confidence to do the work.62 64 85 86 92 Some problems during delivery (such as managing family dynamics64 65 70 74 78 88 95) could also be related to staff skills and experience.71 78 81 As expected, having a structured regime of supervision, encouraging attendance and ongoing support was described as helping staff to deliver work with families.63 72 78 79 88 Staff also reported on the value of belief in the approach and having an identity in their role.71 72 79 81 86

Team attitudes, commitment and multidisciplinary cooperation

Difficulties arose when only a minority of team members had been trained in an intervention.82 Staff reported that collaboration was often lacking63 65 69 73 77 80 and that involving families requires whole team commitment.76 82 ‘Ownership’ was sometimes an issue, with various staff groups perceiving family work as within the domain of other roles, not theirs.69 80 Role and team-specific issues also emerged, such as psychiatrists, inpatient staff and home treatment teams being less involved.63 66 73 81 Collaboration in the form of multidisciplinary coworking, peer-supervision and whole team approaches were all reported as aids to implementing family work.63 66 71–74 78 79 82 88

Problems with finding ‘appropriate’ referrals were reported widely.65 67 68 77 78 80 82 83 93 While some patients do not have families, the pervasiveness of this response also called into question staff members’ pre-existing ideas about what constitutes an ‘appropriate’ family for intervention. Staff reported the resistance of other professionals to make referrals,67 88 family work services being ‘forgotten’ and referrals being made as a ‘last resort’, by which time the families themselves may have grown resistant.93 Acting as a facilitator was the promotion of family work, both as a cascading effect through colleagues and across services.64 79 87

Engagement: addressing concerns through openness, encouragement and building alliances

The next theme related to the process of engagement, informed more broadly by both staff and family responses. A picture emerged of families sometimes being reluctant to engage, and of valid concerns. Yet the successful establishment of trusting relationships indicates these concerns may be surmountable in many cases.

Reservations about involving families

Similar issues around the nature of involving families emerged as a barrier to families becoming involved and as problems during treatment. Some concerns seemed linked to fears around power and control: bi-directional privacy concerns (keeping the extent of the illness from the family and keeping family issues from services)70 and patients’ fears of placing relatives in a position of power70 95 or of exposing their vulnerability.75 Responses in all three participant groups addressed the need for an exclusive patient–professional relationship.69 70 76 95 Existing individual and family problems (such as patients’ symptoms being directed at family members62) also precluded family involvement. Both families and staff expressed fears of making the current situation worse, such as by burdening the family and worsening the patient's symptoms.70 80 84 86 91 Professionals described building trust and rapport, through open discussions with the family, acknowledging concerns and providing reassurance.71 74 88 91

Problems engaging families

These were often unspecified as scepticism, lack of motivation or refusal from the families, occurring prior to engagement or during treatment.65 76 78 83 84 88 93 96 As professional responses, these may reflect their attitudes towards families as unmotivated, but could also describe the failure of the team to mobilise the family in favour of treatment.96 A factor described as a facilitator was having a critical period of engagement: intensive efforts at contact and involvement early on after contact with services93 96–99 and presenting the approach enthusiastically71 89 functioned to establish collaborative relationships between families and professionals as the modus operandi.

Delivery: active collaboration, professional skills and respect for families as individuals

The final theme related to factors that affected how staff members delivered FIs and how families experienced them. As a whole, both family and staff responses highlight the importance of respectful, equal partnership, enhanced by professional skills and experience.

Working relationships between families and professionals

Collaboration between families and professionals on an equal footing appeared valued by both families and professionals. Lack of collaboration was cited as a problem during delivery, resulting in families feeling patronised or not understood.76 Open Dialogue papers particularly emphasised the lack of success when actions were unilaterally decided, rather than emerging from a joint process.74 99 Factors helping to overcome this included being able to relinquish control, that is, tolerate uncertainty in order to allow a joint solution to emerge,78 96 98–100 approaching the family on an equal basis71 and actively collaborating with families during meetings.66 71 89 92 96

How families experienced an approach closely linked with their experience of the professional. Some families reported experiencing an approach as negative or critical, both through the model itself for example, its characterisation of illness,101 or experiences of the professional, perhaps as criticising parenting.101 102 Yet, the interpersonal qualities of the professional and the establishment of a therapeutic alliance strongly emerged as facilitating factors: professionals being informed, genuine, warm, non-blaming71 89 101 and demonstrating an awareness and understanding of the problems of the whole family.71 79 89 90 99

A lack of continuity was cited as a problem,99 while a facilitator was having the same team involved from the beginning and staying with the family throughout the treatment process.96 98 99

Individualisation within the approach

Approaches were sometimes described as culturally insensitive:76 88 rigid, manualised approaches did not meet the general needs of particular groups while individual needs, such as illiteracy, were sometimes not catered to.64 76 97 103 Professionals and families valued having a clear structure while allowing for flexibility.71 76 88 99 Professionals’ skills were also important, by way of communicating information in an easy-to-understand format, avoiding jargon71 88 89 99 and developing an individualised and contextualised approach.71 76 88 93 99

Working with complex needs

Professionals highlighted the complexities of working both with families and with patients with psychosis. The difficulties of managing patient symptoms and working in a meaningful way with their beliefs73 104 may be compounded by family dynamics64 65 70 74 78 88 95 104 and potentially relatives’ own emotional and affective problems.104 Staff members’ qualities, skills and experience in the area were naturally described as facilitating factors.71 76 78 79 81 83 89 90 100 Perhaps unsurprisingly, useful skills were described as working creatively to overcome barriers, hypothesising, reflecting and persevering.71 79 100

Discussion

Main findings

Our results suggest that having ‘top-down’ support and training some staff members to carry out family work is necessary but not sufficient. In order to effectively implement family involvement in care, all members of a clinical team should be trained and regularly supervised and a ‘whole team approach’ should be used. Developing a clear structure for the intervention may be beneficial for the delivery of family involvement, provided that flexibility to accommodate individual needs is ensured. Concerns emerged regarding privacy, power relations, fear of negative outcomes and the need for an exclusive patient–professional relationship. Exploring and acknowledging such concerns through open, yet non-judgemental communication could facilitate the establishment of a therapeutic alliance between staff, families and patients.

These findings may help to explain why family interventions—despite their overwhelming evidence base and their inclusion in practically all policies and guidelines—are so poorly implemented in routine practice. The requirements identified may be challenging given that family-oriented practice may need to be embraced by a whole organisation and included in work routines in order to be implemented.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that specifically focused on barriers, problems and facilitating factors for the implementation of family involvement in the treatment of patients with psychosis. This is of high importance given the current climate of government policies and psychiatric guidelines stipulating that families should be supported and actively involved in psychiatric treatment,6–11 and the disappointments in achieving this in practice so far. The search strategy allowed for the capture of a large number of studies, different researchers independently extracted and reviewed the data and when necessary authors were contacted to clarify ambiguous information. The use of thematic analysis, described as having the ‘most potential for hypothesis generation’,108 allowed for understanding the larger picture, which is more than the sum of its findings. While interpretative, this process has been carried out in accordance with RATS guidelines61 and presented transparently. Though some themes were not highly recurrent—for example, criticisms of manualisation emerged only in structured approaches such as Behavioural Family Therapy—in all, findings were complimentary, not contradictory. The fact that common themes emerged in spite of variations in approach, across 16 countries, speaks for the robustness of the findings as representing shared issues with family involvement.

However, a number of limitations must be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Methodologically, conducting subgroup analysis, that is, for different intervention models, was not considered viable due to the strong association between type of approach and methodology used for example, Open Dialogue with case studies and Behavioural Family Therapy with the Family Intervention Schedule (FIS) questionnaire. Carrying out a subgroup analysis may have therefore had the risk of mischaracterising certain approaches due to variation in the richness of data. While there are well-established methods for assessing the quality of intervention studies, this is not the case for studies of implementation processes, qualitative or mixed methods research56 and the use of appraisal tools in qualitative research remains contentious.109 110 The decision not to use quality-based analysis was therefore also based on recognition of the important contribution and explanatory value that descriptive accounts offer. Despite efforts to find grey literature, the search strategy may still have been limited in its bias towards published research, yet the nature of this review topic means that service level audits and evaluations are likely to be of relevance. Conceptually, the dominance of staff and academic perspectives may have led to barriers within the organisation being explored most thoroughly, however does not lead to the conclusion that there are no inherent problems with involving families in clinical settings.

Comparison with available literature and implications for practice

Our findings reflect important key features for implementation of evidence-based practices, already identified in previous research in implementation science, such as top-down input and leadership and the need for continuing consultation and training.105 The presence of management and leadership decisions and strategies operating as barriers and facilitating factors throughout the organisational context—both directly and indirectly—aligns with findings that leadership at all levels (eg, executive director, middle manager, clinical supervisor) is associated with innovation,106 implementation of evidence-based practice (EBP),107 and with improving the organisational context for EBP implementation.108 The need for support from senior managers (and commissioners) and for a whole team approach is also reflected in the suggestions on how to implement family work in mental health services provided by professionals and carers with experience of participating in a Family Behavioural Therapy Programme.109

The fundamental role of the organisational context is emphasised in the literature with both culture (the normative beliefs and shared expectations of the organisation) and organisational climate (the psychological impact of the work environment on the professional) strongly moderating the uptake of EBP.110 The practice to be implemented must match the mission, values, tasks and duties of the organisation and individuals within that organisation.111 The absence of a strong organisational culture favouring family work may be influenced by traditional paradigms based on the predominance of biological models of mental illness, which tend to minimise the focus on the individual's social context.50 Also, the characterisations of families as dysfunctional and sometimes even as ‘the cause of psychiatric illness,’ despite being widely rejected,112 may have contributed to a loss of trust in services and strained relationships between professionals and families.113 This may explain the importance and the effort required in building alliances, which emerged in our findings. Clinicians may uphold the patient–professional alliance by addressing concerns regarding privacy and by being mindful that patients do not perceive a loss of power due to having family involvement in their care.

Future directions for research

So far the findings largely reflect what can go wrong rather than provide evidence of successful implementation. For example, sustainability has not been addressed in the review as this stage has hardly been reached. More research will be needed to see which organisational steps can actually change the culture in a service so that family involvement happens, not only in a research study or with particular patients, but with all families, every day and over longer periods of time.

Future studies should attempt to better capture wider views, particularly in-depth understanding of patients’ and families’ views. This may also enable insight into the potentially varied experiences of minority groups. These views may be best obtained outside of group interviews, in which a power imbalance may be present. There would also be value in exploring the views of professionals who have not already demonstrated commitment to family work.

Despite a ‘whole team approach’ seeming to be the way forward for a widespread implementation of family work, there is a need to obtain insight into the organisational challenges that may be related to this and to develop clear practical guidelines for the reorganisation of clinical teams.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DG, EE and SP contributed to the conception and design of the study. EE designed and conducted the search, DG and EE selected the studies. AD and EE extracted data and carried out the thematic synthesis. EE wrote the manuscript, AD and DG reviewed and edited the manuscript and SP provided critical review of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final submitted version.

Funding: This paper presents independent research and was partially funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC) North Thames at Bart's Health NHS Trust.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Attempts were made where possible to focus on patients with psychosis, however many studies used opportunity sampling of mixed ‘severe mental illness’ groups, which were included in order to be as inclusive as possible.

References

- 1.Clarke C Relating with professionals. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2006;13:522–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker G, Clarke H. Making the ends meet: do carers and disabled people have a common agenda? Policy Politics 2002;30:347–59 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Growing recognition of the importance of service user involvement in mental health service planning and evaluation. Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc 2005;14:1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guberman N, Nicholas E, Nolan M, et al. Impacts on practitioners of using research-based carer assessment tools: experiences from the UK, Canada and Sweden, with insights from Australia. Health Soc Care Community 2003;11:345–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mottaghipour Y, Bickerton A. The pyramid of family care: a framework for family involvement with adult mental health services. Adv Ment Health 2005;4:210–17 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Government. Carer Recognition Act 2010. Australia: Australian Government, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Recognised, valued and supported: next steps for the carers strategy. London: HMSO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Family psychoeducation: how to use the evidence-based practices KITs. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Mental Health in England. NIMHE Guiding Statement on Recovery. Department of Health, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management NICE clinical guideline 178. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schizophrenia Commission (Rethink). The abandoned illness: a report from Schizophrenia Commission, 2012

- 12.Herz MI, Lamberti JS, Mintz J, et al. A program for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:277–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridgen GJ, Aston J, Gschwandtner U, et al. Help-seeking and pathways to care in the early stages of psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:1033–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergner E, Leiner AS, Carter T, et al. The period of untreated psychosis before treatment initiation: a qualitative study of family members’ perspectives. Compr Psychiatry 2008;49:530–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan C, Fearon P, Hutchinson G, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and ethnicity in the AESOP first-onset psychosis study. Psychol Med 2006;36:239–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garety PA, Fowler DG, Freeman D, et al. Risk of harm after psychological intervention: authors’ reply. Br J Psychiatry 2008;193:345–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glick ID, Stekoll AH, Hays S. The role of the family and improvement in treatment maintenance, adherence, and outcome for schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31:82–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schofield N, Quinn J, Haddock G, et al. Schizophrenia and substance misuse problems: a comparison between patients with and without significant carer contact. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:523–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleury M-J, Grenier G, Caron J, et al. Patients’ report of help provided by relatives and services to meet their needs. Community Ment Health J 2008;44:271–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman RM, Malla AK, Manchanda R, et al. Social support and three-year symptom and admission outcomes for first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2005;80:227–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tempier R, Balbuena L, Lepnurm M, et al. Perceived emotional support in remission: results from an 18-month follow-up of patients with early episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:1897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray-Swank AB, Dixon L. Family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice. CNS Spectrums, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfammatter M, Junghan UM, Brenner HD. Efficacy of psychological therapy in schizophrenia: conclusions from meta-analyses. Schizophr Bull 2006;32:S64–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, et al. Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;12:CD000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bäuml J, et al. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. FOCUS 2004;2:78–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med 2002;32:763–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Schizophrenia: core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in primary and secondary care (update). British Psychological Society, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(6):CD004718-NaN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucksted A, McFarlane W, Downing D, et al. Recent developments in family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice. J Marital Fam Ther 2012;38:101–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleary M, Freeman A, Hunt GE, et al. What patients and carers want to know: an exploration of information and resource needs in adult mental health services. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005;39:507–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jubb M, Shanley E. Family involvement: the key to opening locked wards and closed minds. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2002;11:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien L, Cole R. Mental health nursing practice in acute psychiatric close-observation areas. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2004;13:89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rose LE, Mallinson RK, Walton-Moss B. Barriers to family care in psychiatric settings. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longo S, Scior K. In-patient psychiatric care for individuals with intellectual disabilities: the service users’ and carers’ perspectives. J Ment Health Nurs 2004;13:211–21 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodgson O, King R, Leggatt M. Carers of mentally ill people in Queensland: their perceived relationships with professional mental health service providers: report on a survey. Adv Ment Health 2002;1:220–34 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lammers J, Happell B. Mental health reforms and their impact on consumer and carer participation: a perspective from Victoria, Australia. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2004;25:261–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keeley B, Clarke M. Carers speak out project: report on findings and recommendations. London: Princess Royal Trust for Carers, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkinson C, McAndrew S. ‘I'm not an outsider, I'm his mother!’ A phenomenological enquiry into carer experiences of exclusion from acute psychiatric settings. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2008;17:392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Askey R, Holmshaw J, Gamble C, et al. What do carers of people with psychosis need from mental health services? Exploring the views of carers, service users and professionals. J Fam Ther 2009;31:310–31 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinfold V, Corry P. Who cares? The experiences of mental health carers accessing services and information. Kingston-upon-Thames: Rethink, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinfold V, Farmer P, Rapaport J, et al. Positive and inclusive. Effective Ways for Professionals to Involve Carers in Information Sharing. Report to the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO)2004

- 42.Repper J, Grant G, Nolan M, et al. Carers’ views on, and experiences of mental health services and carer assessments: the results of a consultation exercise. Partnerships in Carer Assessment Project School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Sheffield, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh J, Boyle J. Improving acute psychiatric hospital services according to inpatient experiences. A user-led piece of research as a means to empowerment. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2009;30:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rethink. Who Cares? The experience of mental health carers accessing services and information. London: Rethink Publications, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glynn SM Family interventions in schizophrenia: promise and pitfalls over 30 years. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2012;14:237–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:903–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berry K, Haddock G. The implementation of the NICE guidelines for schizophrenia: barriers to the implementation of psychological interventions and recommendations for the future. Psychol Psychother-Theory Res Pract 2008;81:419–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim H, Salyers MP. Attitudes and perceived barriers to working with families of persons with severe mental illness: mental health professionals’ perspectives. Community Ment Health J 2008;44:337–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen A, Glynn S, Murray-Swank A, et al. The family forum: directions for the implementation of family psychoeducation for severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:40–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Dixon LB, et al. The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for schizophrenia: opportunities and obstacles. Schizophr Bull 2006;32:451–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prytys M, Garety P, Jolley S, et al. Implementing the NICE guideline for schizophrenia recommendations for psychological therapies: a qualitative analysis of the attitudes of CMHT staff. Clin Psychol Psychother 2011;18:48–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simpson E, House A. User and carer involvement in mental health services: from rhetoric to science. Br J Psychiatry 2003;183:89–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slade M, Pinfold V, Rapaport J, et al. Best practice when service users do not consent to sharing information with carers National Multimethod Study. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:148–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mairs H, Bradshaw T. Implementing family intervention following training: what can the matter be? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2005;12:488–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Version 2006;1 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clark J How to peer review a qualitative manuscript. Peer Rev Health Sci 2003;2:219–35 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brent BK, Giuliano AJ. Psychotic-spectrum illness and family-based treatments: a case-based illustration of the underuse of family interventions. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2007;15:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fadden G Overcoming barriers to staff offering family interventions in the NHS. In: Lobban F, Barrowclough C, eds. A casebook of family interventions for psychosis. Chichester: Wiley and Sons, 2009:309 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fadden G, Birchwood M, Lefley H, et al. British models for expanding family psychoeducation in routine practice. Family Interventions in Mental Illness: International Perspectives Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002:25–41 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brennan G, Gamble C. Schizophrenia family work and clinical practice. Ment Health Nurs 1997;17:12–6 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brooker C, Butterworth C. Working with families caring for a relative with schizophrenia: the evolving role of the community psychiatric nurse. Int J Nurs Stud 1991;28:189–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Malangone C, et al. Implementing family psychoeducational intervention for bipolar I disorder in 17 Italian Mental Health Centres. Giornale Italiano di Psicopatologia/Italian J Psychopathol 2011;17:277–82 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butler MP, Begley M, Parahoo K, et al. Getting psychosocial interventions into mental health nursing practice: a survey of skill use and perceived benefits to service users. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:866–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goudreau J, Duhamel F, Ricard N. The impact of a family systems nursing educational program on the practice of psychiatric nurses—a pilot study. J Fam Nurs 2006;12:292–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peters S, Pontin E, Lobban F, et al. Involving relatives in relapse prevention for bipolar disorder: a multi-perspective qualitative study of value and barriers. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:172 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/341/CN-00851341/frame.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.James C, Cushway D, Fadden G. What works in engagement of families in behavioural family therapy? A positive model from the therapist perspective. J Ment Health 2006;15:355–69 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelly M, Galvin K. Does a cross-educational practice meeting assist Thorn graduates to implement psychosocial interventions into clinical practice? J Ment Health Training Educ Pract 2010;5:18–26 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haun MW, Kordy H, Ochs M, et al. Family systems psychiatry in an acute in-patient setting: the implementation and sustainability 5 years after its introduction. J Fam Ther 2013;35:159–75 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seikkula J When the boundary opens: family and hospital in co-evolution. J Fam Ther 1994;16:401–14 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Allen J, Burbach F, Reibstein J. ‘A different world’ individuals’ experience of an integrated family intervention for psychosis and its contribution to recovery. Psychol Psychother 2013;86:212–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Allen RES, Read J. Integrated mental health care: practitioners’ perspectives. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1997;31:496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baguley I, Butterworth A, Fahy K, et al. Bringing into clinical practice skills shown to be effective in research settings: a follow-up of ‘Thorn Training’ in psychosocial family interventions for psychosis. Psychosis: psychological approaches and their effectiveness. London, England: Gaskell/Royal College of Psychiatrists; England, 2000:96–119 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bailey R, Burbach FR, Lea SJ. The ability of staff trained in family interventions to implement the approach in routine clinical practice. J Ment Health 2003;12:131–42 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fadden G, Heelis R, Bisnauth R. Training mental health care professionals in behavioural family therapy: an audit of trainers’ experiences in the West Midlands. J Ment Health Training Educ Pract 2010;5:27–35 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen A, Glynn S, Young A, et al. Implementing family services at mental health clinics. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:S305–6 [Google Scholar]

- 81.De La Higuera Romero J, Ramirez Ruiz RM. Implementation of family psycho-educational programs in clinical practice: analysis of an experience. Apuntes de Psicologia 2011;29:71–85 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fadden G Implementation of family interventions in routine clinical practice following staff training programs: a major cause for concern. J M Health 1997;6:599–613 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kavanagh DJ, Clark D, Manicavasagar V, et al. Application of cognitive-behavioral family intervention for schizophrenia in multidisciplinary teams—what can the matter be. Aust Psychol 1993;28:181–88 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Fadden G, et al. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention for families of patients with schizophrenia: preliminary results of a study funded by the European Commission. World Psychiatry 2005;4:45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Malangone C, et al. Implementing psychoeducational interventions in Italy for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:266–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Michie S, Pilling S, Garety P, et al. Difficulties implementing a mental health guideline: an exploratory investigation using psychological theory. Implementation Sci 2007;2:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Murphy N Development of family interventions: a 9-month pilot study. Br J Nurs 2007;16:948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Balaji M, Chatterjee S, Koschorke M, et al. The development of a lay health worker delivered collaborative community based intervention for people with schizophrenia in India. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Campbell A How was it for you? Families’ experiences of receiving behavioural family therapy. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004;11:261–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stanbridge RI, Burbach FR, Lucas AS, et al. A study of families’ satisfaction with a family interventions in psychosis service in Somerset. J Fam Ther 2003;25:181–204 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hudson BL Behavioural social work with schizophrenic patients in the community. Br J Soc Work 1978;8:159–70 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murphy N, Withnell N. Assessing the impact of delivering family interventions training modules: findings of a small-scale study. Ment Health Nurs 2013;33:10.– [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hughes I, Hailwood R, Abbati-Yeoman J, et al. Developing a family intervention service for serious mental illness: clinical observations and experiences. J Ment Health 1996;5:145–60 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harvey C, O'Hanlon B, Leggatt M, et al. Building Family Skills Together: An implementation strategy for evidence-based family interventions in public mental health services. In: Kellehear K, et al, (Eds). 2020 vision, looking toward excellence in mental health care in 2020, Contemporary The MHS in mental health services, Melbourne Conference Proceedings, 2007 (pp 86–90). Sydney, Australia: The MHS Conference Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Piippo J, Aaltonen J. Mental health and creating safety: the participation of relatives in psychiatric treatment and its significance. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2003–12 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Seikkula J, Alakare B, Aaltonen J. Open dialogue in psychosis II: a comparison of good and poor outcome cases. J Constructivist Psychol 2001;14:267–84 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Forrest S, Masters H, Milne V. Evaluating the impact of training in psychosocial interventions: a stakeholder approach to evaluation–part II. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004;11:202–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seikkula J, Aaltonen J, Alakare B, et al. Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies. Psychother Res 2006;16:214–28 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seikkula J, Alakare B, Aaltonen J. Open dialogue in psychosis I: an introduction and case illustration. J Constructivist Psychol 2001;14:247–65 [Google Scholar]

- 100.O'Neill M, Moore K, Ryan A. Exploring the role and perspectives of mental health nurse practitioners following psychosocial interventions training. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2008;15:582–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Budd RJ, Hughes IC. What do relatives of people with schizophrenia find helpful about family intervention? Schizophr Bull 1997;23:341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Viljoen D, Boyd J. Service user views: promoting a systemic therapy service in adult mental health. Clin Psychol Forum 2005(152):13–6 [Google Scholar]

- 103.Piippo J, Aaltonen J. Mental health: integrated network and family-oriented model for co-operation between mental health patients, adult mental health services and social services. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:876–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tompson MC, Rea MM, Goldstein MJ, et al. Difficulty in implementing a family intervention for bipolar disorder: the predictive role of patient and family attributes. Fam Process 2000;39:105–20 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/892/CN-00557892/frame.html [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, et al. Core implementation components. Res Soc Work Pract 2009;19:531–40 [Google Scholar]

- 106.Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm Sci Q 2001;46:685–716 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Edmondson AC Learning from failure in health care: frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii3–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Aarons G Transformational and transactional leadership: association with attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1162–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fadden G, Heelis R. The meriden family programme: lessons learned over 10 years. J Ment Health 2011;20:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. J Organ Behav 2002;23:767–94 [Google Scholar]

- 111.Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad Manag Rev 1996;21:1055–80 [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wynne LC The rationale for consultation with the families of schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994;90(s384): 125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Winefield HR Barriers to an alliance between family and professional caregivers in chronic schizophrenia. J Ment Health 1996;5:223–32 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.