Abstract

Background

P2Y12 antagonist therapy improves outcomes in acute myocardial infarction (MI) patients. Novel agents in this class are now available in the US. We studied the introduction of prasugrel into contemporary MI practice to understand the appropriateness of its use and assess for changes in antiplatelet management practices.

Methods and Results

Using ACTION Registry‐GWTG (Get‐with‐the‐Guidelines), we evaluated patterns of P2Y12 antagonist use within 24 hours of admission in 100 228 ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and 158 492 Non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients at 548 hospitals between October 2009 and September 2012. Rates of early P2Y12 antagonist use were approximately 90% among STEMI and 57% among NSTEMI patients. From 2009 to 2012, prasugrel use increased significantly from 3% to 18% (5% to 30% in STEMI; 2% to 10% in NSTEMI; P for trend <0.001 for all). During the same period, we observed a decrease in use of early but not discharge P2Y12 antagonist among NSTEMI patients. Although contraindicated, 3.0% of patients with prior stroke received prasugrel. Prasugrel was used in 1.9% of patients ≥75 years and 4.5% of patients with weight <60 kg. In both STEMI and NSTEMI, prasugrel was most frequently used in patients at the lowest predicted risk for bleeding and mortality. Despite lack of supporting evidence, prasugrel was initiated before cardiac catheterization in 18% of NSTEMI patients.

Conclusions

With prasugrel as an antiplatelet treatment option, contemporary practice shows low uptake of prasugrel and delays in P2Y12 antagonist initiation among NSTEMI patients. We also note concerning evidence of inappropriate use of prasugrel, and inadequate targeting of this more potent therapy to maximize the benefit/risk ratio.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, P2Y12 antagonist, prasugrel

Introduction

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend initiation of dual antiplatelet therapy as soon as possible after admission among all eligible MI patients regardless of revascularization strategy.1–3 This recommendation is based on evidence from multiple randomized trials showing that a P2Y12 antagonist, in conjunction with aspirin, improves cardiovascular outcomes in both ST‐elevation (STEMI) and non‐ST‐elevation MI (NSTEMI) patients.4–8 Yet, most of these data are based on clopidogrel. Second‐generation P2Y12 antagonists, such as prasugrel, have a more rapid, potent, and consistent antiplatelet effect than clopidogrel.9 In a randomized controlled trial of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), prasugrel significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular event rates compared with clopidogrel, but had higher rates of major bleeding.8 Secondary analyses have suggested that prasugrel may have greater benefit‐risk ratios in certain high‐risk patient populations, such as those who present with STEMI10 or those with diabetes.11 Due to its higher risk of bleeding, specifically intracranial hemorrhage, the Food and Drug Administration recommends contraindication to prasugrel use in patients with prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), and cautionary use in patients with age ≥75 years or weight <60 kg. In July 2009, prasugrel was approved for clinical use in ACS patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).12 More recently, the Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Optimal Strategy to Medically. Manage Acute Coronary Syndromes (TRILOGY ACS) study failed to show a benefit of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in medically managed ACS patients13 and the Pretreatment with Prasugrel at the Time of Diagnosis in Patients with Non‐ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (ACCOAST) study found no significant benefit to prasugrel pretreatment in patients managed with an early invasive strategy.14

The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry‐Get With the Guidelines (ACTION Registry‐GWTG) provides a unique opportunity to observe patterns of new drug uptake and its potential impact on guideline adherence in routine clinical practice. We aimed to describe the characteristics of patients receiving early clopidogrel versus prasugrel and to ascertain the appropriateness and timing of P2Y12 antagonist use in acute MI patients.

Methods

Data Source

Details of the ACTION Registry‐GWTG have been previously described.15 Briefly, as a joint quality improvement initiative of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, this national registry collects detailed patient clinical information on consecutive STEMI and NSTEMI patients using standardized data definitions and extensive data quality assurance programs. Hospital participation is voluntary with participation at each hospital either approved by the local institutional review board (IRB) or deemed to be essential to quality improvement and thus not subject to IRB approval. Because patient data are collected anonymously via retrospective chart review, individual patient‐informed consent is not required.

Study Population

Using ACTION Registry‐GWTG, all patients admitted with STEMI or NSTEMI from October 1, 2009 to September 31, 2012 were evaluated. This time period was selected to permit study of antiplatelet therapy use after the introduction of prasugrel into clinical practice in July 2009. Of note, although approved by the FDA in July 2011, ticagrelor was not added to the data collection form until 2013, thus data on ticagrelor use was unavailable but felt to be very low (<5% per informal query of manufacturer) during this study period. Treatment choice was at the complete discretion of the treating physician in this registry, and clinician‐documented contraindications to therapy as rationale for nonprescription were captured by the registry data collection form. Patients who were not prescribed P2Y12 antagonist therapy due to a clinician‐documented contraindication (n=13 998), those who transferred out or died within 24 hours of admission (n=5334), or those with missing data on P2Y12 antagonist use (n=527) were excluded. This yielded a final study population of 100 228 STEMI and 158 492 NSTEMI patients treated at 548 hospitals in the United States.

Statistical Analysis

In the overall study population, we first examined trends in early P2Y12 antagonist use and contrasted this with trends in discharge P2Y12 antagonist use. We assessed trends in clopidogrel versus prasugrel use over time between 2009 and 2012. In ACTION Registry‐GWTG, early use was defined as documented use within 24 hours of admission, similar to previous investigation in the CRUSADE registry, GRACE registry, and recent work in NCDR.16–19

Among patients treated with early P2Y12 antagonist therapy, we compared baseline characteristics between clopidogrel‐ and prasugrel‐treated groups using Kruskal‐Wallis tests for continuous variables, and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We then examined frequency of prasugrel use among patients for whom a contraindication or cautionary use is indicated. We further compared in‐hospital treatment (use of concomitant medications, use and timing of invasive procedures) stratified by P2Y12 antagonist and MI type.

The frequency of prasugrel use by predicted risks of in‐hospital mortality and bleeding was then evaluated. Predicted risk was calculated using the ACTION mortality20 and bleeding risk scores21 previously derived and validated with ACTION Registry‐GWTG data. Patients were divided into risk quintiles by ACTION mortality risk and ACTION bleeding risk scores, and frequency of prasugrel use in each population was reported. To identify patients that might benefit most from potent antiplatelet therapies, patients were divided into high‐ and low‐risk groups using the median risk scores for mortality and bleeding. The frequency of prasugrel use in each of the four groups for STEMI and NSTEMI patients was reported.

Multivariable analyses were performed to determine independent factors associated with initial prasugrel (versus clopidogrel) selection by using logistic generalized estimating equations method with exchangeable working correlation matrix. Variables were selected from previously established clinical characteristics, and those shown to be significantly associated with prasugrel use in univariable analyses. Covariates included age, STEMI presentation, prior stroke, weight, heart failure symptoms on admission, shock on admission, insurance status, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, race, creatinine, prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, gender, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking status, prior MI, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, PCI, presentation troponin and hemoglobin values, and hospital features including teaching hospital, region, and surgical capability as well as hospital site as a random effect. Continuous variables were tested for linearity and plotted against rates of prasugrel use to create dichotomous cutoff points where applicable. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2‐sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Temporal Trends of Early P2Y12 Antagonist Use

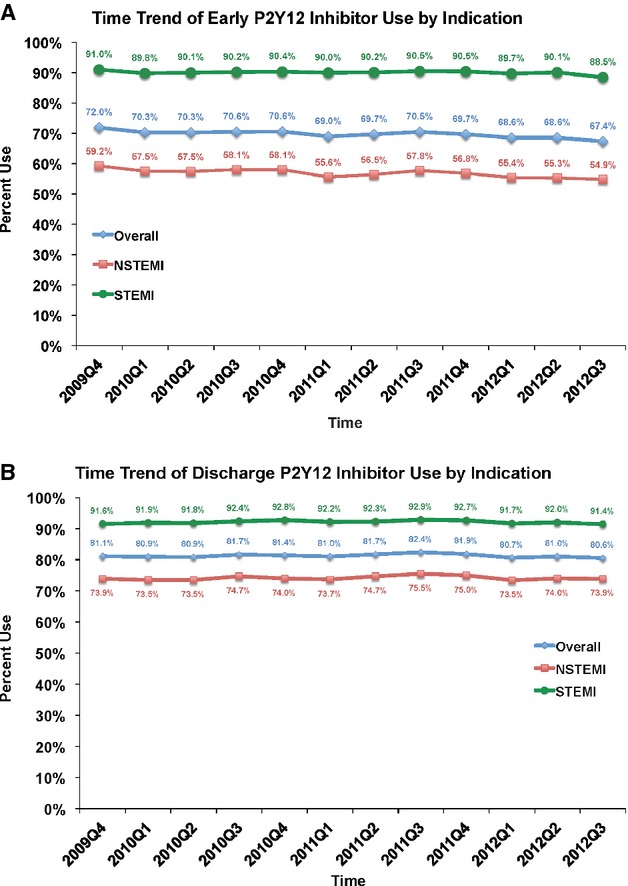

In this contemporary MI population, early P2Y12 antagonist therapy was prescribed in nearly 70% of all patients (90% in STEMI patients and 57% in NSTEMI patients). This rate slightly decreased (72% to 67%) from 2009 to 2012 overall (P<0.0001 for trend) and among NSTEMI patients (P<0.0001 for trend), as shown in Figure 1A. In contrast, discharge P2Y12 antagonist use rates were stable without significant change over this period (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Time trend of overall P2Y12 antagonist use. A, The figure shows the use of early P2Y12 antagonists over time in this study overall, then stratified by MI type. Overall P2Y12 antagonist use decreased slightly over time (P for trend <0.001). Similar trends were seen for NSTEMI (P for trend <0.001) and STEMI patients (P for trend=0.0001). B, The figure shows the discharge use of P2Y12 antagonists over time in this study overall, then stratified by MI type. There was no change in rates of use over time (P for trend 0.43 overall, 0.43 for NSTEMI, and 0.72 for STEMI). MI indicates myocardial infarction. STEMI indicates ST elevation myocardial infarction.

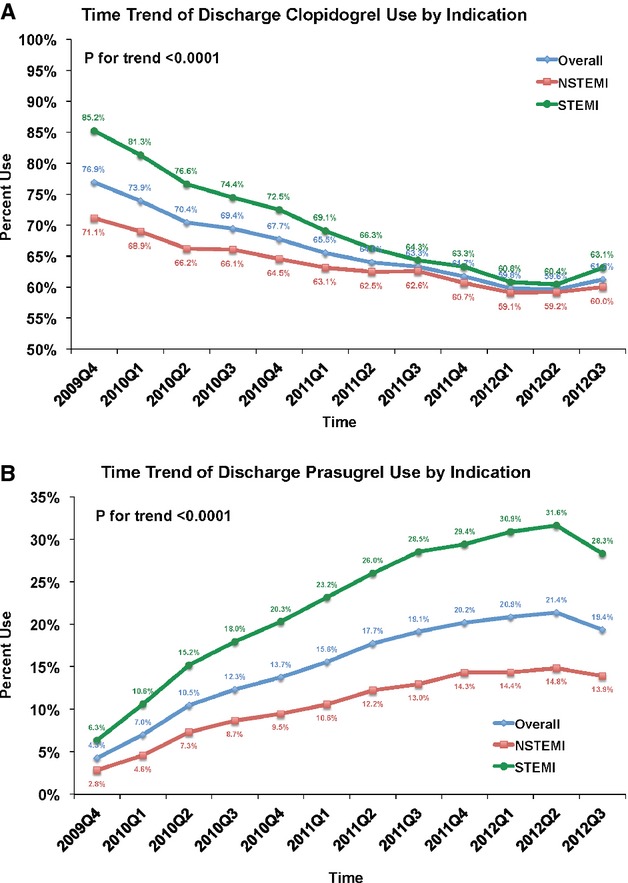

Among patients who received early P2Y12 antagonist therapy, 147 176 patients were treated with clopidogrel (82%) and 32 941 patients were treated with prasugrel (18%). Over this study period, clopidogrel use trended downward, more notably for STEMI than NSTEMI patients (Figure 2A). A corresponding increase in prasugrel use was observed over the study period: overall use increasing from 3% to 18%. When stratified by MI type, early prasugrel use increased from 5% to 30% among STEMI patients in this time period, but only from 2% to 10% among patients with NSTEMI (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Time trend of early P2Y12 antagonist use. A, The figure shows the early use of clopidogrel overall and stratified by type of myocardial infarction. Use of clopidogrel decreased with time in all groups (P for trend <0.0001 for all). B, The figure shows the early use of prasugrel overall and stratified by type of myocardial infarction. Use of prasugrel increased with time in all groups, but most significantly in patients presenting with STEMI (P for trend <0.0001 for all).

Factors Associated With Early Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel Use

Baseline characteristics stratified by choice of early P2Y12 antagonist are shown in Table 1. Prasugrel‐treated patients were substantially younger, more likely to be male, and less likely to have medical comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or a history of prior MI when compared with clopidogrel‐treated patients. Prasugrel‐treated patients were also heavier, less likely to have atrial fibrillation or be on warfarin, aspirin, or dual antiplatelet therapy prior to hospital admission, and more likely to smoke than patients who received clopidogrel. Prasugrel‐treated patients were more likely to present with STEMI than clopidogrel‐treated patients. Rates of major bleeding on the same day as admission were very low in both clopidogrel (0.5%) and prasugrel treated patients (0.4%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Stratified by Choice of Early P2Y12 Antagonist

| Characteristics | Clopidogrel (N=147 176) | Prasugrel (N=32 941) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y* | 64 (54, 75) | 57 (50, 64) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 66% | 77% | <0.0001 |

| Weight, kg* | 84 (72, 99) | 90 (78, 103) | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.4 (25.1, 32.6) | 29.4 (26.1, 33.4) | <0.0001 |

| Insurance status | <0.0001 | ||

| HMO/private | 56% | 63% | |

| Medicare | 24% | 14% | |

| Medicaid | 4% | 4% | |

| Self/none | 12% | 17% | |

| Other | 1% | 1% | |

| Past medical history | |||

| Hypertension | 73% | 62% | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 62% | 55% | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker | 37% | 48% | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31% | 25% | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6% | 2% | <0.0001 |

| Prior MI | 26% | 19% | <0.0001 |

| Prior PCI | 27% | 23% | <0.0001 |

| Prior CABG | 15% | 7% | <0.0001 |

| Prior stroke | 8% | 2% | <0.0001 |

| Currently on dialysis | 2% | 1% | <0.0001 |

| Home medications | |||

| Aspirin | 43% | 33% | <0.0001 |

| Warfarin | 4% | 1% | <0.0001 |

| Clopidogrel | 20% | 7% | <0.0001 |

| Prasugrel | 0.2% | 4% | <0.0001 |

| Dual antiplatelet use | 16% | 9% | <0.0001 |

| Presentation Features | |||

| STEMI | 45% | 65% | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg* | 145 (124, 166) | 145 (126, 165) | 0.80 |

| Baseline hemoglobin, g/dL* | 14 (2) | 15 (2) | <0.0001 |

| Heart failure or shock | 13% | 6% | <0.0001 |

| Baseline CrCl, mL/min*,* | 82 (56, 111) | 100 (78, 127) | <0.0001 |

BP indicates blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CrCl, creatinine clearance (among non‐dialysis patients); HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; VAMC, Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Continuous variables expressed as medians (25th, 75th percentiles).

Estimated by the Cockcroft‐Gault formula.

The independent factors associated with initial prasugrel (versus clopidogrel) selection after multivariable analysis are shown in Table 2. Date of MI admission was one of the strongest factors with more recent admission associated with greater odds of prasugrel use. Increasing age over age 75, prior stroke, and lower body weight under 80 kg were associated with lower odds of prasugrel use. While STEMI presentation was associated with greater use of prasugrel, notably diabetic status was not a significant independent factor associated with P2Y12 antagonist selection.

Table 2.

Independent Factors Associated With Prasugrel (vs Clopidogrel) Selection

| Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time since 2009 Q4 (per quarter) | 1.18 | 1.17 to 1.18 | 4727 |

| Age | 3157 | ||

| per 5 year ↑ age ≤75 | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.04 | |

| per 5 year ↑ age >75 | 0.32 | 0.30 to 0.34 | |

| STEMI presentation | 1.81 | 1.75 to 1.87 | 1272 |

| Prior stroke | 0.38 | 0.35 to 0.42 | 433 |

| Healthcare insurance | 281 | ||

| Medicare vs HMO/private | 0.78 | 0.75 to 0.82 | |

| Self/none vs HMO/private | 0.79 | 0.76 to 0.82 | |

| Weight | 234 | ||

| per 5 kg ↓ ≤80 kg | 0.92 | 0.90 to 0.93 | |

| per 5 kg ↑ >80 kg | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 | |

| Prior PCI | 1.26 | 1.21 to 1.32 | 99 |

| Initial creatinine, mg/dL | 0.88 | 0.85 to 0.90 | 89 |

| Prior CABG | 0.77 | 0.73 to 0.81 | 84 |

| Male | 1.15 | 1.12 to 1.18 | 75 |

| HF and/or shock on admission | 73 | ||

| HF only | 0.74 | 0.69 to 0.80 | |

| Shock | 0.87 | 0.80 to 0.94 | |

| Home warfarin | 0.64 | 0.58 to 0.72 | 63 |

| Heart rate (per 10 bpm ↑ > 60 bpm) | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.98 | 62 |

| Race (white vs other) | 1.14 | 1.09 to 1.19 | 37 |

| Initial Hgb, g/dL | 1.02 | 1.02 to 1.03 | 27 |

| Home lipid‐lowering agent | 1.10 | 1.06 to 1.14 | 27 |

| Prior PAD | 0.86 | 0.80 to 0.92 | 20 |

| Hypertension | 0.93 | 0.90 to 0.96 | 17 |

| Home aspirin | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.11 | 14 |

| Prior CHF | 0.87 | 0.81 to 0.94 | 14 |

Variables in the model include all those listed above and hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking status, prior MI, PCI, SBP, presentation Troponin and hospital features including teaching hospital, region, surgical capability. Hospital site was also in the model as a random effect. All variables in table are statistically significant (P<0.01 and χ2>10) and are listed in order of contribution to the model as measured by the chi‐square statistic. Non‐significant variables are listed above in this footnote. CHF indicates coronary heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Contraindicated, Cautionary, and Off‐Label Use of Prasugrel

In ACTION Registry‐GWTG, clinicians documented a contraindication to prasugrel therapy in 1782 patients during this study period; among these 8.5% had a prior history of stroke. Our study population already excluded the patients with clinician‐documented contraindications to prasugrel, yet still observed that 604/20 312 (3%) of patients with prior stroke were prescribed prasugrel. Cautionary use is advised in patients over age 75 and under 60 kg of body weight; these characteristics were noted in 66 772 (26% of our study population) and 23 595 (9%) patients, respectively. Prasugrel in these groups was low, but present: 2% of patients ≥75 years of age (n=1255) and 5% of patients weighing <60 kg (n=1061). Although lacking evidence to support use, prasugrel was used in 2% of patients who were medically managed and did not undergo percutaneous or surgical revascularization (n=1191). Finally, 12% of STEMI patients treated with fibrinolytic therapy also received early prasugrel (n=801).

Predicted Clinical Risk and In‐Hospital Treatment

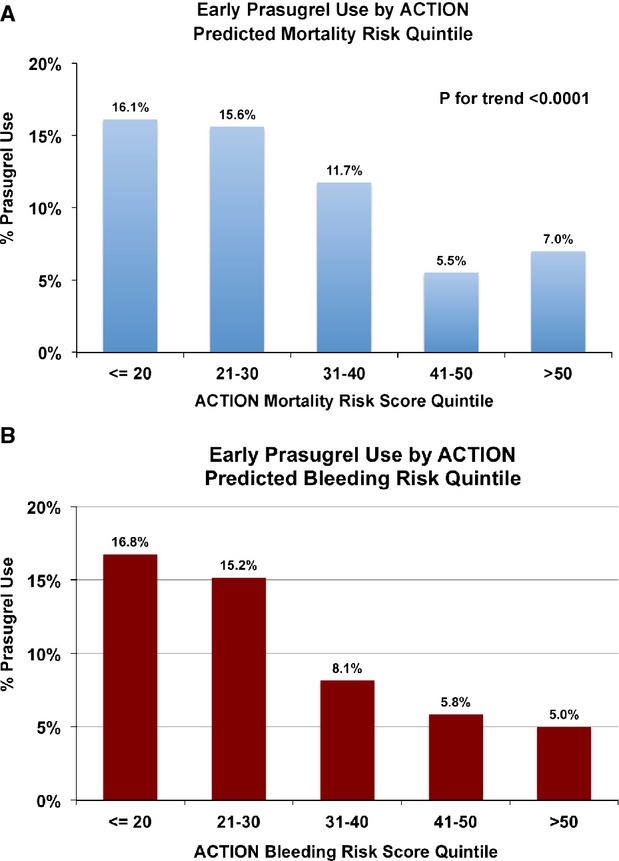

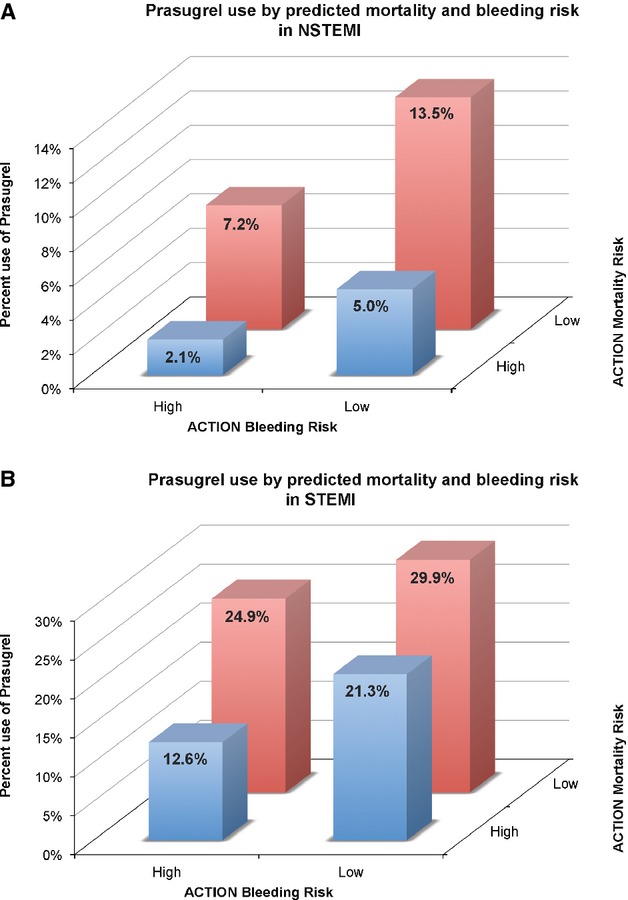

Prasugrel use decreased significantly, in a stepwise manner with increasing predicted risk of bleeding but also with increasing predicted risk of mortality (Figure 3). For both STEMI and NSTEMI patients, the highest rates of prasugrel utilization were observed in patients with both low predicted mortality risk and low predicted bleeding risk (Figure 4A and 4B). Prasugrel was more frequently used in patients deemed low predicted mortality and high predicted bleeding risk, than in those deemed high predicted mortality, but low predicted bleeding risk. Lowest rates of prasugrel use were in patients with both high predicted bleeding and predicted mortality risks.

Figure 3.

Early prasugrel use by ACTION predicted risk quintile. A, Early prasgurel use is plotted by quintile of predicted ACTION Mortality risk. Prasugrel use decreases significantly with increasing predicted mortality risk. B, Early prasgurel use is plotted by quintile of predicted ACTION Bleeding risk. Prasugrel use decreases significantly with increasing predicted bleeding risk. ACTION indicates acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes network.

Figure 4.

Prasugrel use by predicted mortality and bleeding risk. A, Early prasugrel use is plotted by both predicted ACTION mortality (X axis) and ACTION bleeding risk (Z axis) for NSTEMI. Prasugrel use is highest in low risk individuals. B, Early prasugrel use is plotted by both predicted ACTION mortality (X axis) and ACTION bleeding risk (Z axis) for STEMI. Prasugrel use is highest in low risk individuals. ACTION indicates acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes network.

Patients who received prasugrel were more likely to undergo early invasive treatment in the NSTEMI population, or primary PCI in the STEMI population compared with those that received clopidogrel (Table 3). In both STEMI and NSTEMI patients, prasugrel‐treated patients were less likely to be initiated on P2Y12 antagonist therapy prior to cardiac catheterization; 18% of NSTEMI patients were pre‐treated with prasugrel prior to cardiac catheterization. Prasugrel‐treated patients were also less likely to have received fibrinolytics, less likely to undergo CABG during admission, and less likely to be medically managed for MI compared with clopidogrel‐treated patients. Additionally, glycoprotein IIb‐IIIa (GP IIb‐IIIa) inhibitors and bivalirudin were more likely to be used in prasugrel‐treated patients compared with clopidogrel‐treated patients, in NSTEMI.

Table 3.

Patterns of Invasive Management and Concomitant Therapy Use Stratified by MI Type and Early P2Y12 Antagonist Use

| NSTEMI | STEMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel (N=78 559) | Prasugrel (N=11 308) | P Value | Clopidogrel (N=68 617) | Prasugrel (N=21 633) | P Value | |

| Early invasive therapy* | 52% | 89% | <0.0001 | — | — | — |

| Primary PCI | — | — | — | 92% | 96% | <0.0001 |

| Drug initiation prior to cath | 65% | 18% | — | 48% | 15% | — |

| Fibrinolytic therapy | — | — | — | 14% | 10% | <0.0001 |

| CABG | 6% | 2% | <0.0001 | 3% | 1% | <0.0001 |

| Medically managed | 35% | 8% | <0.0001 | 3% | 2% | <0.0001 |

| GP IIb‐IIIa* | 27% | 44% | <0.0001 | 58% | 59% | <0.0001 |

| Bivalirudin | 29% | 47% | <0.0001 | 35% | 48% | <0.0001 |

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; DM, diabetes mellitus; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Within 48 hours of admission.

Discussion

Antiplatelet therapeutic options have expanded with the introduction of novel P2Y12 antagonists to the clinical setting, but uptake of these new therapies into clinical practice has not been well studied. Our results show low initial use of prasugrel in clinical practice with gradual uptake, more among STEMI patients, over the study period. We also observed a decreasing trend in early but not discharge P2Y12 antagonist use over time among NSTEMI patients, suggesting that clinicians may be delaying the use and choice of P2Y12 antagonist until a revascularization strategy has been selected. Finally, we raise concerns of inappropriate use of new antiplatelet agents and suboptimal targeting of therapies to patients that maximize the benefit‐risk ratio.

Patterns of Care After Introduction of Prasugrel

Previous investigation had shown increased utilization of guideline‐recommended antiplatelet agents in ACS patients and a trend towards increasing use with time.18,22–23 Despite addition of another treatment option with prasugrel approval in 2009, adherence to guideline‐recommended early dual antiplatelet therapy had a paradoxical decrease from 2009 to 2012 among NSTEMI patients. In contrast, the rate of P2Y12 antagonist use at discharge has remained stable over the same time period. These results signal a shift in P2Y12 antagonist initiation and selection to later during the MI hospitalization after prasugrel became a treatment option. Early clopidogrel treatment in patients with ACS has been shown to reduce adverse cardiovascular events,24–26 but is accompanied by an increased risk of bleeding. Prasugrel, while associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes compared with clopidogrel, also further increased bleeding risk and in the TRITON‐TIMI 38 study, was not initiated until PCI.8 Thus, the observed delay in P2Y12 antagonist initiation may reflect a reluctance to select an agent until angiographic data is available and a revascularization strategy can be selected. With a longer half‐life, prasugrel also requires longer duration of withdrawal prior to surgery. As such, the delay may also represent clinicians “hedging their bet” against the possible need for CABG. The modest decline in early use of P2Y12 inhibitors may also relate to an increasing number of high‐risk (older, more clinical comorbidities) patients that are being evaluated with MI who might be poor candidates for aggressive medical or invasive therapy.

While prasugrel use has increased since its approval in 2009, it still represents a small proportion of early P2Y12 antagonist use. Adoption of a new drug into clinical practice is influenced by many factors, including drug effectiveness, side effect profiles, strength of evidence for use, inclusion in national guidelines, cost, clinician demographics and training, and infrastructure supporting or promoting its use.27 Many of these are not well understood and the interaction of these factors can be complex for an individual clinician. Chauhan et al27 found that a new drug was more likely to be adopted if the drug's mechanism was novel and there were relatively few choices in the pharmacologic class. These factors would seem to favor adoption of novel antiplatelet therapies such as prasugrel or ticagrelor into clinical practice, but side effect profiles and generic alternatives may have a countering effect. Further study of how new agents are adopted into practice is needed as the number of effective antithrombotic treatment options continue to grow for patients with acute MI.

Prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with prior stroke, and cautionary use is advised for patients ≥75 years of age or those weighing <60 kg due to reduced benefit‐risk ratios. In addition, early prasugrel use has never been studied in patients who received thrombolytic therapy, and evidence supporting its use in the medically treated MI population is equivocal.13 In our study, rates of prasugrel use in these contraindicated, cautionary, and off‐label populations were low, but present. Early use of prasugrel in these populations might be due to lack of full medical history information in emergency situations. Off‐label use of newly introduced therapies is commonly observed in clinical practice and may be a consequence of a knowledge deficit, or motivated by perceived barriers to the expanded indication being approved.28–29 The use of prasugrel in patients with prior stroke likely represents medical error. The use of antithrombotic medications in contraindicated populations undergoing PCI has been previously reported in NCDR, but has not been evaluated in the era of multiple P2Y12 antagonists.30 Based on the study design of TRITON‐TIMI 38, guidelines did not include prasugrel as a P2Y12 antagonist option prior to PCI. Yet, almost 1 in 5 NSTEMI patients treated with prasugrel received it prior to catheterization. Now with the ACCOAST trial showing lack of benefit and increased bleeding with prasugrel pre‐treatment, efforts to educate clinicians on appropriate selection of P2Y12 antagonists should be intensified. These findings speak to the need for increased vigilance and implementation of safeguards to minimize these types of errors.31–32

Risk Stratification and Prasugrel Use

Subgroup analyses of the TRITON—TIMI 38 study showed the benefit/risk ratio balance to be more favorable in certain high‐risk subgroups including patients with STEMI or diabetes.10–11 Our data confirm greater use of prasugrel in STEMI patients, but we did not observe higher rates among diabetic patients in community practice. Current guidelines also advocate for intensive medical therapy for moderate and high‐risk acute MI patients, based on evidence that intensive treatment has the greatest benefit among such high‐risk patients.3 In contrast, our data show the highest rates of prasugrel use among patients with the lowest predicted risks of both mortality and bleeding. This pattern of use in low‐risk patients echoes the risk‐treatment paradox that has been observed in previous studies of acute MI patients.33–34

There may be several reasons for this pattern. First, clinicians may not adequately assess risk based on clinical evaluation. Yan et al34 showed that while intensive invasive and medication treatments were more often applied to patients who clinicians considered high risk, patients who were high risk by established risk prediction algorithms were less likely to receive aggressive therapy. Second, clinicians may place greater weight on the potential risk of bleeding than the benefit of reducing ischemic events by avoiding intensive antiplatelet therapy. Although not collected in ACTION Registry‐GWTG, variables such as prior bleeding or heavy alcohol intake contribute to bleeding and may influence antiplatelet therapy selection. Clinical risk scores to help clinicians identify patients who are most likely to benefit from intensive antiplatelet therapy are readily available.35–36 Integration of their use into bedside risk assessment may promote rational antiplatelet decision‐making. In the outpatient setting that integration of web‐based cardiovascular clinical risk tools with electronic medical records increases rates of risk assessment.37 Whether this leads to improved adherence to guideline‐based care remains to be seen.

Limitations

There are several limitations to consider in this study. First, ACTION Registry‐GWTG is a voluntary program, thus results may not be generalized to national practice as participating hospitals are intrinsically more attuned to quality improvement. These hospitals may be more likely to adhere to guidelines and less likely to use prasugrel among contraindicated patients. Second, while details of treatment and in‐hospital events are collected, we do not have information on individual patient or physician preference for treatment, nor does the data collection form report unique reasons for not implementing P2Y12 antagonist therapy such as recent bleeding. Third, although ticagrelor was approved for clinical use in July of 2011, the registry data collection form did not start capturing its use until 2013. However, uptake of ticagrelor was <5% during our study period (per informal query of manufacturer) and is unlikely to impact study results substantially. Finally, clopidogrel became available as a generic agent during the study period, yet our ability to perform economic analyses is limited by the data available in ACTION Registry‐GWTG.

Conclusions

Prasugrel use has gradually increased since approval. Despite expansion of treatment options, we observed a decreasing trend in early P2Y12 antagonist use but not discharge use, suggesting deferral of P2Y12 antagonist selection until a revascularization plan has been determined. Prasugrel use in contraindicated, cautionary, and off‐label groups is low but present. Prasugrel is most frequently utilized in the lowest‐risk patients, notwithstanding evidence supporting its greatest benefit among higher‐risk patients. Given these results, there is substantial opportunity for systems to improve risk stratification of MI patients, to guide appropriate targeting of potent antiplatelet therapy to the patients most likely to benefit, and to prevent inappropriate use in patients with contraindications or those at high risk of bleeding.

Sources of Funding

This project was supported in part by grant number U19HS021092 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Disclosures

Matthew W. Sherwood—Education Grant from AstraZeneca. Stephen D. Wiviott—Research funding: Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai; Speaking/Consulting: Angelmed, ICON, Aegerion, Eisai, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Web MD, Xoma. S. Andrew Peng—None. Matthew T. Roe—Research grants to the Duke Clinical Research Institute from Eli Lilly & Co, KAI Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi‐Aventis; Consulting/Honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck & Co, Janssen, Regeneron, Daiichi Sankyo. James DeLemos—Honoraria: Astra Zeneca; Consulting: Janssen. Eric D. Peterson—Research grants to the Duke Clinical Research Institute from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, Eli Lilly & Co, Janssen, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; Consulting/Honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Janssen, Merck & Co, Sanofi‐Aventis. Tracy Y. Wang—Research grants to the Duke Clinical Research Institute from The Medicines Co, Canyon Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo Alliance, and Gilead Science; consulting/honoraria from Medco Health Solutions, Inc, Astra Zeneca, and the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation's (ACCF) National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR). The views expressed in this manuscript represent those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCDR or its associated professional societies identified at www.ncdr.com. ACTION Registry‐GWTG is an initiative of the ACCF and the American Heart Association, with partnering support from the Society of Chest Pain Centers, the American College of Emergency Physicians, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.

References

- 1.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr, King SB, III, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE, Jr, Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL, Williams DO. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with st‐elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and acc/aha/scai guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:2205-2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz CB, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis‐Holland JE, Tommaso JE, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Force CAT. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of st‐elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127:529-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE, Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Philippides GJ, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Zidar JP, Anderson JL. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2012; 126:875-910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Montalescot G, Theroux P, Lewis BS, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Effect of clopidogrel pretreatment before percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytics: the PCI‐CLARITY study. JAMA. 2005; 294:1224-1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST‐segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:494-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Montalescot G, Theroux P, Claeys MJ, Cools F, Hill KA, Skene AM, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST‐segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1179-1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, Xie JX, Pan HC, Peto R, Collins R, Liu LS. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45 852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 366:1607-1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2001-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiviott SD, Trenk D, Frelinger AL, O'Donoghue M, Neumann FJ, Michelson AD, Angiolillo DJ, Hod H, Montalescot G, Miller DL, Jakubowski JA, Cairns R, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Antman EM, Braunwald EInvestigators P‐T. Prasugrel compared with high loading‐ and maintenance‐dose clopidogrel in patients with planned percutaneous coronary intervention: the prasugrel in comparison to clopidogrel for inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation‐thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 44 trial. Circulation. 2007; 116:2923-2932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, Antman EM. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON‐TIMI 38): double‐blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009; 373:723-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Angiolillo DJ, Meisel S, Dalby AJ, Verheugt FW, Goodman SG, Corbalan R, Purdy DA, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Antman EM. Greater clinical benefit of more intensive oral antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel in patients with diabetes mellitus in the trial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition with prasugrel‐thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 38. Circulation. 2008; 118:1626-1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Food and Drug Administration CfDEaR. FDA approves effient to reduce the risk of heart attack in angioplasty patients. 2009. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2009/ucm171497.htm Accessed July 10, 2009.

- 13.Roe MT, Armstrong PW, Fox KA, White HD, Prabhakaran D, Goodman SG, Cornel JH, Bhatt DL, Clemmensen P, Martinez F, Ardissino D, Nicolau JC, Boden WE, Gurbel PA, Ruzyllo W, Dalby AJ, McGuire DK, Leiva‐Pons JL, Parkhomenko A, Gottlieb S, Topacio GO, Hamm C, Pavlides G, Goudev AR, Oto A, Tseng CD, Merkely B, Gasparovic V, Corbalan R, Cinteza M, McLendon RC, Winters KJ, Brown EB, Lokhnygina Y, Aylward PE, Huber K, Hochman JS, Ohman EM, Investigators TA. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes without revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:1297-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, Goldstein P, Hamm C, Tanguay JF, ten Berg JM, Miller DL, Costigan TM, Goedicke J, Silvain J, Angioli P, Legutko J, Niethammer M, Motovska Z, Jakubowski JA, Cayla G, Visconti LO, Vicaut E, Widimsky P. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:999-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Chen AY, Fonarow GC, Lytle BL, Cannon CP, Rumsfeld JS. The NCDR action Registry‐GWTG: transforming contemporary acute myocardial infarction clinical care. Heart. 2010; 96:1798-1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diercks DB, Kontos MC, Hollander JE, Mumma BE, Holmes DN, Wiviott S, Saucedo JF, de Lemos JA. ED administration of thienopyridines in non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the NCDR. Am J Emerg Med. 2013; 31:1005-1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta RH, Roe MT, Mulgund J, Ohman EM, Cannon CP, Gibler WB, Pollack CV, Jr, Smith SC, Jr, Ferguson TB, Peterson ED. Acute clopidogrel use and outcomes in patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:281-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao RV, Goodman SG, Yan RT, Spencer FA, Fox KA, DeYoung JP, Rose B, Grondin FR, Gallo R, Gore JM, Yan AT. Temporal trends and patterns of early clopidogrel use across the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2009; 157:e641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander D, Ou FS, Roe MT, Pollack CV, Jr, Ohman EM, Cannon CP, Gibler WB, Fintel DJ, Peterson ED, Brown DL. Use of and inhospital outcomes after early clopidogrel therapy in patients not undergoing an early invasive strategy for treatment of non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines (CRUSADE). Am Heart J. 2008; 156:606-612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chin CT, Chen AY, Wang TY, Alexander KP, Mathews R, Rumsfeld JS, Cannon CP, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, Roe MT. Risk adjustment for in‐hospital mortality of contemporary patients with acute myocardial infarction: the acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes network (ACTION) registry‐get with the guidelines (GWTG) acute myocardial infarction mortality model and risk score. Am Heart J. 2011; 161:e112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathews R, Peterson ED, Chen AY, Wang TY, Chin CT, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Rumsfeld JS, Roe MT, Alexander KP. In‐hospital major bleeding during ST‐elevation and non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction care: derivation and validation of a model from the action registry(r)‐GWTG. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 107:1136-1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tricoci P, Roe MT, Mulgund J, Newby LK, Smith SC, Jr, Pollack CV, Jr, Fintel DJ, Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED, Harrington RA. Clopidogrel to treat patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes after hospital discharge. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:806-811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta RH, Roe MT, Chen AY, Lytle BL, Pollack CV, Jr, Brindis RG, Smith SC, Jr, Harrington RA, Fintel D, Fraulo ES, Califf RM, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED. Recent trends in the care of patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the crusade initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:2027-2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial I. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST‐segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:494-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szuk T, Gyongyosi M, Homorodi N, Kristof E, Kiraly C, Edes IF, Facsko A, Pavo N, Sodeck G, Strehblow C, Farhan S, Maurer G, Glogar D, Domanovits H, Huber K, Edes I. Effect of timing of clopidogrel administration on 30‐day clinical outcomes: 300‐mg loading dose immediately after coronary stenting versus pretreatment 6 to 24 hours before stenting in a large unselected patient cohort. Am Heart J. 2007; 153:289-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, Bertrand ME, Lewis BS, Natarajan MK, Malmberg K, Rupprecht H, Zhao F, Chrolavicius S, Copland I, Fox KA. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long‐term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI‐CURE study. Lancet. 2001; 358:527-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chauhan D, Mason A. Factors affecting the uptake of new medicines in secondary care—a literature review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008; 33:339-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL. Ten common questions (and their answers) about off‐label drug use. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2012; 87:982-990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao SV, Shaw RE, Brindis RG, Klein LW, Weintraub WS, Peterson EDAmerican College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data R. On‐ versus off‐label use of drug‐eluting coronary stents in clinical practice (report from the American College Of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry [NCDR]). Am J Cardiol. 2006; 97:1478-1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai TT, Maddox TM, Roe MT, Dai D, Alexander KP, Ho PM, Messenger JC, Nallamothu BK, Peterson ED, Rumsfeld JS. Contraindicated medication use in dialysis patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2009; 302:2458-2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bates DW. Using information technology to reduce rates of medication errors in hospitals. BMJ. 2000; 320:788-791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gawande AA, Bates DW. The use of information technology in improving medical performance. Part II. Physician‐support tools. MedGenMed. 2000; 2:E13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roe MT, Peterson ED, Newby LK, Chen AY, Pollack CV, Jr, Brindis RG, Harrington RA, Christenson RH, Smith SC, Jr, Califf RM, Braunwald E, Gibler WB, Ohman EM. The influence of risk status on guideline adherence for patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2006; 151:1205-1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M, Fung A, Cohen EA, Fitchett DH, Langer A, Goodman SG. Management patterns in relation to risk stratification among patients with non‐ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167:1009-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, Pieper KS, Goldberg RJ, Van de Werf F, Goodman SG, Granger CB, Steg PG, Gore JM, Budaj A, Avezum A, Flather MD, Fox KA. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: Estimating the risk of 6‐month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004; 291:2727-2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, Gage BF, Rao SV, Newby LK, Wang TY, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Pollack CV, Jr, Peterson ED, Alexander KP. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non‐ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress Adverse outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) Bleeding Score. Circulation. 2009; 119:1873-1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells S, Furness S, Rafter N, Horn E, Whittaker R, Stewart A, Moodabe K, Roseman P, Selak V, Bramley D, Jackson R. Integrated electronic decision support increases cardiovascular disease risk assessment four fold in routine primary care practice. Eur J Cardiovas Prev Rehabil. 2008; 15:173-178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]