Abstract

The pathogenesis of diseases elicited by the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is partially determined by the effectiveness of adaptation to the variably acidic environment of the host stomach. Adaptation includes appropriate adherence to the gastric epithelium via outer membrane protein adhesins such as SabA. The expression of sabA is subject to regulation via phase variation in the promoter and coding regions as well as repression by the two-component system ArsRS. In this study, we investigated the role of a homopolymeric thymine [poly(T)] tract −50 to −33 relative to the sabA transcriptional start site in H. pylori strain J99. We quantified sabA expression in H. pylori J99 by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), demonstrating significant changes in sabA expression associated with experimental manipulations of poly(T) tract length. Mimicking the length increase of this tract by adding adenines instead of thymines had similar effects, while the addition of other nucleotides failed to affect sabA expression in the same manner. We hypothesize that modification of the poly(T) tract changes DNA topology, affecting regulatory protein interaction(s) or RNA polymerase binding efficiency. Additionally, we characterized the interaction between the sabA promoter region and ArsR, a response regulator affecting sabA expression. Using recombinant ArsR in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA), we localized binding to a sequence with partial dyad symmetry −20 and +38 relative to the sabA +1 site. The control of sabA expression by both ArsRS and phase variation at two distinct repeat regions suggests the control of sabA expression is both complex and vital to H. pylori infection.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the human gastric epithelium and infects more than half the world's population. Individuals are most frequently colonized during childhood, and without treatment, infection persists for the lifetime of the infected host. Though the majority of colonized individuals remain asymptomatic, H. pylori is the causative agent of chronic active gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (1–3).

Successful colonization of the stomach and the onset of disease are determined largely by interactions between the host and H. pylori (1, 4–6). The abilities of H. pylori to adapt to various acidic environments and to adhere to the gastric epithelium play substantial roles in colonization and long-term persistence in the human stomach (7). Adherence prevents clearance of H. pylori during gastric mucous shedding and ensures that nutrients from damaged epithelial cells are consistently available to the bacterium (8).

Several putative adhesins have been identified in H. pylori, most of which are members of the large outer membrane protein (OMP) family. BabA is a major adhesin and binds the Lewis b (Leb) antigen expressed in the gastric mucosa (7). Another outer membrane protein adhesin, SabA (jhp0663 [HP0725]), facilitates adhesion by binding to glycosphingolipids displaying a sialyl-dimeric Lewis X antigen, the expression of which is increased in gastric epithelial cells during inflammation. Additionally, dynamic adaptation in sialyl-binding properties of SabA during persistent infection has been observed and may allow H. pylori to specialize for individual host variation in mucosal glycoprotein sialylation. Variations in sialyl-binding properties of SabA also may allow for tropisms in local areas of inflamed tissue, as inflammation often results in changes in mucosal sialyated glycoconjugates (9). Thus, the ability of H. pylori to adhere to sialylated glycoconjugates may contribute to virulence by facilitating persistent infection in the face of the host's inflammatory response (10).

Several studies have revealed the regulation of sabA expression in H. pylori to be very complex (11–13). Transcription of sabA is regulated via phase variation mediated by changes in dinucleotide repeats near the 5′ end of the coding sequence (11). Additional layers of expression control are mediated by environmental signals acting through the two-component signal transduction system ArsRS (11). A recent study by Talarico et al. (12) showed that recombination between the sabA locus and its paralogous locus, sabB, affects sabA expression significantly. Finally, recent evidence has shown that sabA and babA are coregulated with the host expression of mucins, to which H. pylori adheres in the gastric mucosal epithelium (14). Thus, the regulation of sabA is complex and multidimensional.

Phase variation is mediated by slipped-strand mispairing leading to insertions or deletions (indels) within repetitive DNA tracts during replication. When an indel-modified tract arises in the coding region of the gene, these indels result in an altered reading frame (15). sabA contains a dinucleotide cytosine-thymine repeat in the 5′ coding region, and changes in the CT tract length were shown in a previous study from our laboratory to result alternatively in a truncated or full-length SabA protein, as indicated by altered binding to AGS cells in vitro (11).

There is a second repetitive sequence associated with sabA: a homopolymeric thymine [poly(T)] tract in the promoter region. The H. pylori strain J99 contains a poly(T) tract of 18 nucleotides in length situated −50 to −33 relative to the sabA transcriptional start site mapped by Sharma et al. (16). A recent study by Kao et al. (13) compared the sabA expression of several distinct clinical isolates of H. pylori to that of variant poly(T) tracts in the sabA promoter region, suggesting that differing poly(T) tract lengths change sabA gene expression levels. However, the observed differences in sabA expression also could be affected by other differences between the genomes of these diverse H. pylori isolates. In addition, Kao et al. constructed an Escherichia coli lux reporter system to measure the effect of experimentally manipulated sabA poly(T) tract lengths, again showing changes in sabA expression as a function of the poly(T) tract length (13). This result is interesting, as sabA expression in E. coli was altered in the absence of any H. pylori transcription factors or H. pylori RNA polymerase. This suggests the effect of poly(T) tract length lies in DNA topology or flexibility rather than any specific H. pylori regulatory systems. However, the experimental alterations in the sabA poly(T) tract within H. pylori itself were not performed, and our current study aimed to elucidate whether changes in this homopolymeric thymine tract impact sabA transcription in its native setting.

While phase variation of sabA allows population-level control of gene expression, H. pylori also regulates gene expression at the individual cell level using a small number of two-component signal transduction (TCST) systems. This allows adaption to environmental changes at the transcriptional level (17–23). When the histidine kinase protein of a TCST encounters the appropriate stimulus, it undergoes autophosphorylation; subsequently, the phosphoryl group is transferred to a response regulator. The resulting conformational change results in altered binding of the response regulator to cognate sites on the genome and modified expression of genes in the TCST regulon (24). Previous studies of the HP0165-HP0166 TCST in H. pylori strain 26695 determined that changes in environmental pH acted as a stimulus for this TCST; thus, it was redesignated arsRS (acid-responsive signaling) (18). A previous study in our laboratory comparing the genome-wide transcriptional profiles between wild-type strain 26695 H. pylori and an isogenic arsS histidine kinase mutant found sabA was derepressed in the mutant, suggesting that ArsR is a repressor of sabA (11, 19). Our laboratory had previously demonstrated a significant role for ArsRS in the expression of sabA (11, 19), and our current study used electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) to localize the binding of recombinant ArsR.

In the present study, we hypothesized that indels in this poly(T) tract affect sabA expression levels by affecting the efficiency of transcription of sabA, thereby acting as a second method of phase variation regulation in addition to the poly(CT) tract. Thus, SabA expression may be regulated both transcriptionally and translationally by two distinct phase variation events. We hypothesized that phase variation in the poly(T) tract results in physical changes in the length of the promoter control region that result in a change in DNA topology and affect the trans-acting regulatory protein interaction(s) governing sabA expression (25, 26).

Our findings regarding phase variation and signal transduction provide new insights into the complex genetic mechanisms used by H. pylori and lead to a better understanding of how H. pylori adapts to sustain a persistent infection despite a robust inflammatory and immune response from the host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

H. pylori strain J99 was grown on Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (TSA II; BD) at 37°C in an ambient air-5% CO2 atmosphere. Broth cultures were grown in sulfite-free brucella broth (SFBB) with 5% newborn calf serum (Gibco/BRL).

Cloning.

A 603-bp amplicon, including the 3′ end of jhp0663 (HP0726), the poly(T) tract, −35/−10 putative promoter sites, transcriptional start site, and 5′ coding region of sabA (jhp0662 [HP0725]) was amplified using oligonucleotide primers HP726 Fwd and sabAPolyT.R from H. pylori strain J99 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This corresponds to positions 743281 to 743845 of the H. pylori J99 genome. The amplicon was initially cloned into pCR 4-TOPO (Invitrogen) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the pBlueScript SK+ vector (Stratagene). The resulting plasmid was designated pVKC2 (see Table S2).

To generate the control plasmid, the construct upon which all subsequent mutations were made, a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene from Campylobacter coli (27) was cloned as a SmaI/EcoRV fragment from pBSC103 (28) into a blunt-ended MluI site at the end of jhp0633, the gene immediately upstream of sabA (Fig. 1; also see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The resulting control plasmid, selected for resistance to 25 μg chloramphenicol/ml in E. coli DH5α, was designated pVKC4.T18 (see Table S2). The orientation of the chloramphenicol resistance gene in this construct was confirmed by sequencing.

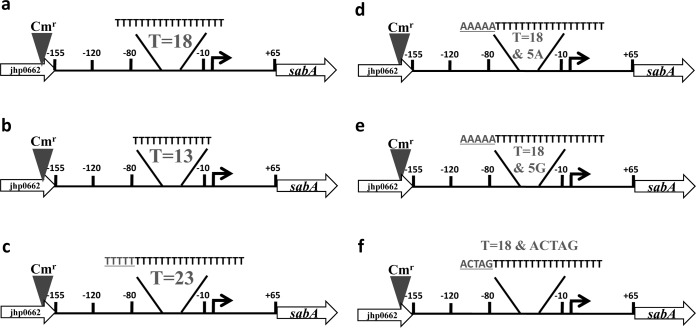

FIG 1.

Mutational strategy to examine the role of a polythymine [poly(T)] tract in the in vivo expression of sabA in H. pylori strain J99. (a) Plasmid constructs containing the jhp0662-sabA region were marked for allelic replacement in H. pylori J99 by the addition of the chloramphenicol resistance gene into the MluI site in jhp0662 and moved into H. pylori J99 to create the control mutant possessing a wild-type poly(T) tract length (T = 18). (b to f) All subsequent mutations were created using the control mutant plasmid. Numbers are nucleotide positions relative to the transcriptional start point (16), shown as a bent arrow. The number of tandem thymines is indicated in each mutant, and added nucleotides are indicated by gray and underlining.

The poly(T) tract region of sabA within the control plasmid pVKC4.T18 was mutated to various T tract lengths using mutagenic primers PolyT.Fwd.5T, PolyT.Rev.5T, PolyT.Fwd.less5T, and PolyT.Rev.less5T (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Mutagenic oligonucleotides were used with the GeneArt site-directed mutagenesis system and Accu Prime Pfx polymerase (Life Technologies). Mutagenic primers were designed to match the sequence of the poly(T) tract site and surrounding sequence; however, modifications in the number of T's were introduced, adding or subtracting five T's. The primers were designed according to the manufacturer's specifications. For the second series of mutagenesis experiments introducing alternative sequence extensions, the forward and reverse primers introducing AAAAA, GGGGG, or the random sequence ACTAG upstream and immediately adjacent to the poly(T)18 tract were designated PolyT.Fwd.5A, PolyT.Rev.5A, PolyT.Fwd.5G, PolyT.Rev.5G, PolyT.Fwd.Ran, and PolyT.Rev.Ran, respectively (see Table S1). Mutagenesis was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol using 40 ng of pVKC4.T18 per 50-μl reaction mix. The mutagenesis product was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and underwent a recombination reaction and transformation into DH5α-T1R E. coli as suggested by the manufacturer's protocol.

Plasmids were generated with variant poly(T) tract lengths of 13 and 23 residues (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In the process of creating plasmids with the expected new length of thymines, alternative-length polymorphisms were isolated as well, possibly due to oligonucleotide poly(T) tract length polymorphisms generated during oligonucleotide synthesis. Thus, three additional plasmids were isolated and confirmed via sequencing reactions and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) to have lengths of 17, 16, and 22 residues (see Table S2). They too were recombined subsequently onto H. pylori strain J99 genome via allelic exchange to further characterize the role of the poly(T) tract in sabA expression.

For additional mutagenesis experiments, plasmids were created to represent three different extended poly(T) tracts: the poly(T)18 tract extended by the nucleotides AAAAA (pVKC4.A5), the random nucleotides ACTAG (pVKC4.Ran), or the nucleotides GGGGG (pVKC4.G5) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The mutated poly(T) tract regions of all plasmids were confirmed via sequencing reactions performed using the BigDye sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) with the primer CAT Fwd (see Table S1).

Natural transformation of and allelic exchange in H. pylori.

The H. pylori strain J99 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) was used as the recipient in natural transformation experiments to select for allelic exchange, resulting in resistance to 10 μg chloramphenicol/ml and the exchange of the wild-type allele for mutant alleles of the sabA promoter region. Freezer stocks of H. pylori J99 were grown for 24 to 36 h on TSA II plates containing 5% sheep blood (Becton-Dickinson) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were harvested into SFBB plus 5% newborn calf serum (NCS). The tubes were centrifuged for 2 min at 3,300 × g, and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl SFBB with NCS and 20 μg vancomycin per ml and spotted on sheep blood agar plates. Ten μg of pVKC4.T18 (control) or poly(T) tract mutant plasmids was spotted onto the H. pylori J99 cell pad, the plate was incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 4 h, and the cells spread over each plate and grown overnight. The cells were harvested from each blood agar plate and transferred to SFBB–5% NCS plates containing 10 μg chloramphenicol/ml. These plates were incubated for 3 to 5 days at 37°C and 5% CO2 until colonies appeared. Mutant strains of H. pylori J99 were designated by the number of thymines present in the poly(T) tract: sabA poly(T)13, sabA poly(T)16, sabA poly(T)17, sabA poly(T)18, sabA poly(T)22, and sabA poly(T)23 (see Table S2). For additional mutagenesis experiments, mutant strains of H. pylori J99 were designated by the five-nucleotide extension upstream and adjacent to the wild-type poly(T) tract length of 18 thymines: sabA A5, sabA G5, and sabA Ran (see Table S2).

To ensure that the allelic exchange of pVKC4.T18 or plasmids bearing mutated poly(T) tracts targeted sabA rather than its paralog, sabB, primers were designed such that an amplicon could be achieved from the sabA locus but not from the sabB locus. The primers for amplification of the region from putatively recombinant H. pylori J99 sabA mutants were CAT Fwd, which lies within the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene, and SabASpecific.R, which represents a sequence unique to sabA and absent from the paralog sabB (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplification and subsequent sequence analysis showed that all recombination had successfully targeted sabA.

AFLP analysis.

To quantify the degree of slipped-strand mispairing and the variation in poly(T) length found in the J99 wild type, J99 T18 control mutant, and J99 sabA poly(T) variant populations of H. pylori, AFLP was conducted by a modification of the protocol of Hallinger et al. (29). Briefly, an oligonucleotide primer pair bracketing the poly(T) tract was synthesized with a VIC tag on the 5′ end of the reverse primer (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies). Primers used in all AFLP analyses were sabA IG Fwd and sabA IG Rev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Amplicons generated were diluted by a factor of 50 and analyzed by an ABI 3100 automated fluorescent DNA sequencer (ABI) using a Liz 300 molecular weight standard set, and data were analyzed using GeneScan (Life Technologies).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

H. pylori wild-type strain J99, the J99 T18 control mutant, and J99 poly(T) variants were grown on TSA II (BD) at 37°C in an ambient air-5% CO2 atmosphere. Broth cultures were grown in SFBB with 5% newborn calf serum (Gibco/BRL) until the cells reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 to 1.6. For RNA extraction, 1 × 109 cells were harvested at 3,300 × g for 5 min, and the pellets were frozen at −80°C. Samples were suspended in 1 ml TRI Reagent (Ambion) prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from each cell pellet according to the manufacturer's protocol for the MagMAX-96 for microarrays (Life Technologies) total RNA isolation kit and the AM1839 spin program on a MagMAX express magnetic particle processor (Life Technologies). Purified RNA concentrations were analyzed on a P360 nanophotometer (Implen) and frozen at −80°C.

cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of purified RNA samples using iScript reverse transcriptase (Bio-Rad) by following the manufacturer's cDNA synthesis protocol. The resulting cDNA was used in qRT-PCR. The expression of H. pylori sabA was compared to that of the housekeeping gene ftsZ (jhp0913), encoding the cell division protein FtsZ, using a TaqMan gene expression assay (Life Technologies) performed on the Applied Biosystems StepOne system. The assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol using custom TaqMan gene expression assays, including the sabA and ftz probes and forward and reverse primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Assays for each strain and each gene were run in technical triplicate, and experiments were repeated three times. The Relative expression of sabA among the various mutants was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method as described by Livak and Schmittgen (30) and processed using DataAssist software (Applied Biosystems).

Recombinant ArsR production and purification.

The response regulator ArsR was produced recombinantly in E. coli M15/pREP4 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Briefly, arsR was amplified from H. pylori using primers arsRFwd.Bam and arsRRev.HindIII (see Table S1). This amplicon, encoding the entire arsR coding sequence, was cloned as a BamHI/HindIII fragment in pQE30 (Qiagen), a 6× His-tagging expression plasmid (see Table S2). Soluble ArsR was expressed in and extracted from E. coli M15/pQE30-26695arsR+pREP4 according to the native batch purification protocol of the manufacturer (Qiagen). Cells of E. coli M15 carrying pQE30 were cultured in 250 ml LB Amp Kan broth (LB containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin) in a baffled flask. This culture was grown at 37°C with shaking to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.7. Expression was induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the culture was returned to the incubator. Cell pellets were resuspended in 2 ml NPI-10 lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) per gram. Lysozyme was added to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml cell suspension, and samples were incubated for 30 min on ice. The resuspended cells then were sonicated at maximum power on ice in six 10-s bursts with a cooling period between each burst. Twelve units of Benzonase nuclease (Novagen) per ml of expression culture was added to each sonicated sample, and the mixtures were incubated for 15 min on ice. The lysates then were centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g and 4°C to pellet the cell debris. The supernatant, which is the soluble fraction, was removed and stored at 4°C. The time point that produced the largest amount of the desired protein in the soluble fraction was selected as the expression time for subsequent purifications.

ArsR was purified on 5-ml-bed-volume drip columns containing 3 ml 50% Ni-NTA-agarose slurry according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen). During purification, a 20-μl aliquot of each fraction was taken for SDS-PAGE, which was performed to check the quality of the purification and to determine which elution fractions to save for use in EMSA. Recombinant ArsR was concentrated to 1 mg/ml using a 10K Microsep column according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pall Life Sciences), glycerol was added to 10% by volume, and aliquots were frozen for subsequent use in DNA binding assays.

EMSA.

Biotin-labeled sabA probes used in DNA binding experiments were amplified from H. pylori strain J99 genomic DNA using oligonucleotides sabA4Bio and sabAProbeRev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) to amplify a 156-bp sabA probe. The same 156-bp region was amplified for specific competition using a nonbiotinylated version of the forward oligonucleotide (sabA4-F) rather than the biotin-labeled version. A truncated, 96-bp version of the sabA probe was generated in both biotinylated and unlabeled versions using either sabA5Bio or sabA5-F oligonucleotides (see Table S1), respectively, paired with sabAProbeRev. All probes were gel purified before use in EMSA.

EMSAs were carried out according to a procedure adapted from the LightShift EMSA optimization kit protocol (Thermo) and the ArsR EMSA protocol of Loh et al. (20). Recombinant ArsR (0.2 to 0.4 nmol) was incubated in a binding reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2.5% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 2 mg poly(dI-dC), 500 ng unlabeled probe (for specific competition reactions), and 500 ng Epstein Barr virus nuclear extract (Sigma) (for nonspecific competition reactions). This mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. One microliter (1 to 2 ng) labeled sabA probe then was added to each binding reaction and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Reactions were electrophoresed immediately on native 6% PAGE gels, blotted onto Zeta probe membranes (Bio-Rad), and cross-linked via UV irradiation. The imaging procedure followed Thermo Scientific's chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module and was visualized using X-ray film.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Multiple alleles of sabA exist in H. pylori J99 and sabA poly(T) mutants due to phase variation in poly(T) tract.

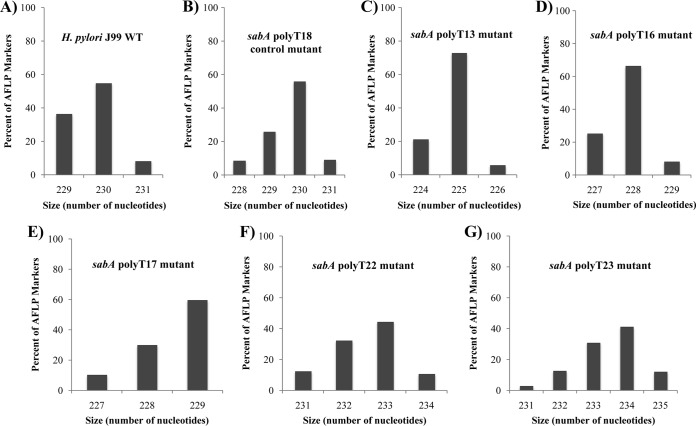

Plasmid constructs with modifications to the poly(T) tract length were designed and introduced into H. pylori J99 strains (Fig. 1A to C). In order to examine allelic variation in the thymine repeat tract at the sabA locus within in vitro populations of H. pylori strain J99 and isogenic poly(T) tract indel mutants, we employed AFLP analysis. Results indicated the presence of multiple-length polymorphisms within the sabA poly(T) repeat tract amplicons from the wild type and all indel mutants (Fig. 2). While each sabA poly(T) tract indel mutant population contained multiple subpopulations possessing slightly different poly(T) lengths based on AFLP analyses, each of these H. pylori J99 mutant strains had a clear dominant population with a particular modified poly(T) tract length. Wild-type H. pylori J99, containing 18 thymines, was measured as having a dominant subpopulation with an amplicon of 230 bp (31). DNA sequencing of this locus confirmed the creation of H. pylori J99 mutants with various poly(T) tract lengths (data not shown). In addition, the length variation of amplicons possessing the poly(T) tract of the sabA promoter within wild-type and mutant H. pylori populations, demonstrated by AFLP, supports the hypothesis of slipped-strand mispairing events during DNA replication. In fact, our data suggest that this activity increases with the increasing length of the repetitive tract. When we experimentally increased the length of the tract from 18 to 23, AFLP analyses showed a less dominant size variant in the population and more measurable-length polymorphisms (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

AFLP analysis of H. pylori sabA poly(T) tract mutants. AFLP analysis was used to quantify variations in the sabA poly(T) tract containing amplicons from H. pylori J99 and poly(T) tract mutants. The amplicon generated using primers sabA IG Fwd and sabA IG Rev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) is predicted to be 230 bp based on the annotated sequence of H. pylori strain J99, where the sabA poly(T) tract possesses 18 thymines (31). Shown are WT H. pylori J99 (A) and the sabA poly(T)18 control mutant (B), sabA poly(T)13 mutant (C), sabA poly(T)16 mutant (D), sabA poly(T)17 mutant (E), sabA poly(T)22 mutant (F), and sabA poly(T)23 mutant (G).

Polythymine tract length in sabA promoter region affects expression.

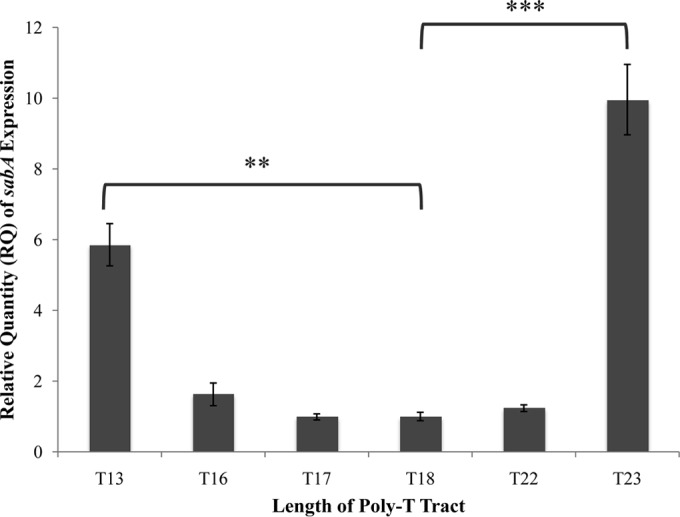

In order to understand the effects of poly(T) length variation on transcriptional activity of the sabA locus, we conducted qRT-PCR on H. pylori strain J99 and the mutant J99 strains with variant poly(T) tract lengths (Fig. 3). The J99 WT strain and poly(T)18 control mutant performed similarly with no significant statistical difference (P > 0.05), as determined by a Welch unpaired t test of unequal variance using the program R Studio, indicating that the addition of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene, used as a marker in the mutant strains, did not have a significant impact on sabA expression (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Notable, however, was the 5.9-fold increase (P = 0.0013) in sabA expression in the H. pylori J99 mutant containing 13 thymines compared to the poly(T)18 control mutant and the 10-fold increase (P = 0.00086) in sabA expression in the H. pylori J99 mutant containing 23 thymines compared to the poly(T)18 control mutant. In contrast, mutants with a poly(T) tract length of 16, 17, 18, and 22 showed less striking changes of no statistical significance (P > 0.05) in the associated sabA expression compared to that of the poly(T)18 control mutant. Similar results and statistical significances were reproduced in the two additional biological replicates. This suggested that when the length of the poly(T) tract is increased or decreased by five nucleotides, corresponding to a half turn of the DNA helix, there is a maximal differential effect on sabA expression.

FIG 3.

sabA expression in H. pylori J99 and J99 sabA poly(T) tract length variants. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to determine the relative expression of sabA in H. pylori J99 compared to that in mutants containing poly(T) tracts of various thymine lengths. The data are a representative trial of the results obtained from three independent experiments, each conducted in technical triplicate. Error bars show standard errors of the means. Statistics were calculated using a Welch's unpaired t test with sabA poly(T)18 as the control (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001).

In light of these results, we first hypothesized that altering the length of the tract by a half turn of the DNA would place the binding site for a trans-acting factor on the opposite face of the DNA, rendering it more or less likely to interact with the RNA polymerase. However, a 2012 study by Kao et al. (13) showed an effect of H. pylori sabA poly(T) variation on lux reporter expression in E. coli, where H. pylori regulatory proteins or RNA polymerases are absent. Thus, considering our data for H. pylori and the results of Kao et al. (13) for E. coli, we hypothesized that the length of the poly(T) tract has a significant impact on the topology or flexibility of the DNA in the sabA promoter region. Alternatively, there may be a shared transcriptional factor found in both E. coli and H. pylori that recognizes such poly(T) tracts mediating similar effects on the sabA promoter activity in both organisms.

Poly(T) tracts are rigid, and their presence affects the bendability of DNA (25). The rigidity and bendability of certain regions of DNA have been found to influence proteins' ability to loop DNA (26). The formation of DNA loops is essential in processes such as DNA replication and transcription regulation. Thus, changes in sequences that modify the rigidity and bendability of sections of DNA influence the energetics of loop formation associated with these essential processes (26). We hypothesize that indels within the poly(T) tract in the promoter region of sabA in H. pylori influence the ability of proteins to loop the DNA and ultimately affect RNA polymerases' ability to bind or for other protein-DNA interactions to take place. Homopolymeric tracts similar to the poly(T) tract in H. pylori were found in a variety of prokaryotic systems (32). The overwhelming presence of homopolymeric tracts across prokaryotic taxa suggests that these tracts have been beneficial to these organisms. A study done by Wernegreen et al. (33) proposed that these homopolymers are advantageous because they are mutational hotspots where slippage can help eliminate and resurrect gene function.

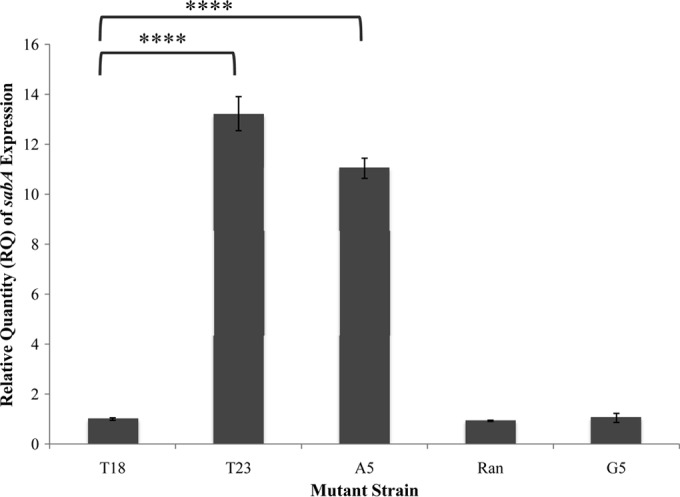

We sought to test our revised hypothesis through a subsequent qRT-PCR experiment. An algorithm created by Vlahovicek et al. (34) predicts a sequence of adenine or thymine nucleotides to be noncurved and of limited bendability, while sequences with higher percentages of guanine and cytosine allow for more curvature and flexibility in DNA topology. To begin to address the role of curvature of DNA in the expression of sabA, we designed and created a series of H. pylori J99 sabA mutants that contained the wild-type sabA poly(T) tract length of 18 nucleotides but now were extended, either by five adenines, five guanines, or a random series of five nucleotides (ACTAG) (Fig. 1d to f). In the mutant containing a poly(T) tract extended by five adenines, sabA expression increased 11-fold compared to sabA expression in the poly(T)18 control mutant (P = 1.6 × 10−5). This increased sabA expression was comparable to that of the T23 mutant strain which had been extended by five thymines (Fig. 4). Perhaps this result is not surprising, as the extended tract still consists of A-T base pairs. Strikingly, however, no significant increase (P > 0.05) in sabA expression occurred when the poly(T) tract was extended by five guanines or by the random series of five nucleotides, ACTAG (Fig. 4). Similar statistics and results were reproduced in the additional two biological replicates.

FIG 4.

sabA expression in H. pylori J99 and J99 sabA poly(T) mutants (nonthymine extensions). Quantitative real-time PCR was used to determine the relative expression of sabA in H. pylori J99 compared to that in mutants containing a poly(T) tract with various five-nucleotide insertions upstream and adjacent to the poly(T) tract. The data shown here are representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments, each conducted in technical triplicate. Error bars show standard errors of the means. Statistics were calculated using a Welch's unpaired t test of unequal variance with sabA poly(T)18 as the control (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001). Schematic representations of these mutants are shown in Fig. 1.

These results support the hypothesis that the nature of the adenine-thymine tract, compared to one possessing guanine-cytosine base pairs or a random series of base pairs, results in changes in DNA topology and has a major effect on sabA expression. The intrinsic curvature of poly(A) tracts in the ureR-ureD intergenic region in Proteus mirabilis is bound in an E. coli model system by both UreR and H-NS. Thus, binding of proteins to the intrinsic curvature of this poly(A) tract affects ureR transcription (35). We hypothesize that the proper bending and curvature of the DNA in and around the H. pylori sabA poly(T) tract allows RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter optimally or allow an upstream activator site and its bound transcription factor to approach RNA polymerase closely enough to affect mRNA synthesis initiation. It is not a simple case of changing the distance between the binding site for a trans-acting factor and the promoter that affects sabA expression; rather, it is the topology of the DNA that allows for modulation of sabA expression.

Another potential means of the altered sabA promoter activity associated specifically with such an A/T homopolymeric tract is via increased stability of RNA polymerase association with the promoter sequences mediated through the poly(T) tract. Consensus UP elements have been identified that are A/T rich and located just upstream of −35 promoter elements (36, 37). These sequences are capable of increasing RNA polymerase affinity for promoters by interacting with C-terminal domains of RNA polymerase α subunits. This may explain the similarity of the results of this study on sabA promoter activity in the native organism, H. pylori, to those of Kao et al. (13), who examined similar sabA poly(T) tract length changes in the heterologous host, E. coli. The use of poly(A/T) tracts in association with H. pylori omp genes is quite widespread (31, 38). This may be a common means of modulating promoter activities in a bacterium, such as H. pylori, that has a paucity of transcription factors.

Determining the ArsR binding site and its relationship with the poly(T) tract.

Previously studies from our laboratory demonstrated that the two-component system ArsRS affects the expression of sabA (11, 19). We now sought to characterize the location of the ArsR binding site in order to determine its proximity to the phase-variable sabA promoter region poly(T) tract. EMSA to locate ArsR binding sites relative to the polythymine tract determined that the binding site was, in fact, downstream of the poly(T) tract and the transcriptional start site. This suggests that ArsR functions as a sabA repressor by preventing passage of the RNA polymerase independent of the poly(T) tract (Fig. 5). Although it appears that ArsR is not involved in regulation of sabA expression via the poly(T) tract, the localization of recombinant ArsR (rArsR) determined in this study is consistent with the established role of ArsR as a repressor of sabA expression (11, 19). Both transcriptional control via phase variation at the poly(T) tract in the sabA promoter region as well as transcriptional control via ArsRS-mediated two-component signal transductions are layered on the translational phase variation mediated by the homopyrimidine dinucleotide repeat, CT, found near the 5′ end of the sabA protein-coding sequence (11). The location of the ArsR binding site itself (between −20 and +38 relative to the transcriptional start site) further supports its role as a repressor of sabA expression (19), as binding here likely prevents open complex formation by preventing RNA polymerase from binding the sabA promoter efficiently. Adding further to the complexity of H. pylori's control of sabA expression is the 2012 study by Talarico et al. (12) that demonstrated strong host selection to maintain sabA as opposed to frequent loss in vitro and that via recombination, sabA could be duplicated as a means to increase SabA levels and increase adherence to host tissue.

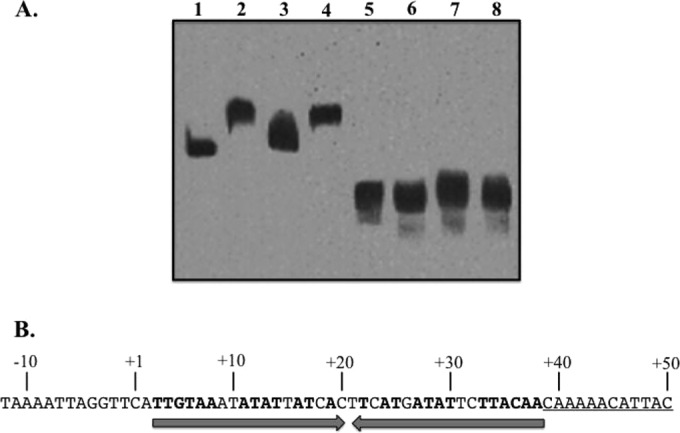

FIG 5.

ArsR binds a sequence downstream of the poly(T) tract associated with the sabA promoter. (A) Nested biotin-labeled probes of the sabA promoter region were used in EMSA to localize the ArsR binding site. A 156-bp sabA probe (−20 to +135) was electrophoresed alone (lane 1), with rArsR (lane 2), with rArsR and a 500-fold excess of unlabeled probe as a specific competitor (lane 3), and with rArsR and a 500-fold excess of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen DNA as a nonspecific DNA competitor (lane 4). rArsR-DNA binding reactions in lanes 5 to 8 were run identically except for the use of a 5′-truncated (to +39 to +135) sabA probe to demonstrate the loss of rArsR binding with the loss of the upstream 60 bp. (B) Proposed binding site of ArsR in the 5′ untranslated region of sabA. Converging arrows indicate a region of partial dyad symmetry within the region bound by rArsR. The underlined sequence is the 5′ end of the truncated probe used in lanes 5 to 8 in panel A.

rArsR bound the 156-bp sabA probe (−20 to +135), the longer of the probes utilized in EMSAs to localize the ArsR binding site (Fig. 5, lanes 1 to 4), and failed to bind the truncated sabA probe (+39 to +135) (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 to 8), indicating the binding site for ArsR lies between −20 and +38 relative to the sabA transcriptional start point. A region of partial dyad symmetry lies at +3 to +38, and this sequence may be responsible for the mobility shift seen in Fig. 5 (lanes 2 and 4).

In the complex interplay between H. pylori and its host, SabA is a key protein of interest. Although other adhesins, such as BabA, are important in the initial stages of infection, studies have shown that the regulation of SabA expression becomes key once host inflammation increases, as the expression of sabA is rapidly modulated in response to the changing conditions of the stomach (39).

Additionally, a common feature of H. pylori-induced gastritis is an infiltration of neutrophils into the gastric mucosa. A 2005 study by Unemo et al. (40) demonstrated that mutant and wild-type H. pylori strains lacking SabA had no neutrophil-activating capacity, suggesting that SabA adhesion to sialylated neutrophil receptors plays an essential initial role in the adherence and phagocytosis of the bacteria. This further supports an argument for the critical role of SabA as a virulence factor in disease pathogenesis (40).

Investigating sabA regulation mediated via phase variation provides a platform for the study of other key H. pylori adhesins. H. pylori is equipped with a variety of outer membrane proteins, including the Hop (Helicobacter outer membrane porin) members, Hor (Hop-related protein) members, and the OMPs AlpA, AlpB, BabA, SabA, and HopZ. Much about their functions remains undiscovered (41). Repetitive nucleotide tracts are found in association with numerous outer membrane protein genes, both in the coding sequence and associated with promoter regions. HopZ (jhp0007 [HP0009]) is regulated by both a phase-variable CT repeat in the coding sequence (42) and a polyadenine tract associated with the promoter. Examining the sequenced genomes of H. pylori shows there are at least eight other outer membrane proteins with a poly(T) or poly(A) tract of at least 10 nucleotides or longer in the associated promoter regions; thus, it is possible that there are similarities in the genetic regulation of many OMPs.

There are few pieces of data suggesting the direct effect of adhesins on signaling pathways, but there is consensus on the role of adhesins to mediate a tight interaction between H. pylori and the host target cell, allowing additional bacterial factors to interact with their corresponding receptors (6). In a previous study with clinical isolates, AlpA and AlpB were produced at a constant rate, but all other OMPs were produced at highly variable rates, ranging from 35% to 73%. This result indicates that SabA is not the only outer membrane protein whose function is in close adaptation to the individual host or gastric niche (41).

Homopolymeric tracts and dinucleotide tracts are abundant in the coding sequence of H. pylori genes, as they are in several other mucosal pathogens (38, 43). In Helicobacter canadensis, an emerging human pathogen, 29 annotated coding regions were determined to be associated with variable-length homopolymeric tracts, and 21 of the repeat-associated coding regions were determined to be potentially transcriptionally or translationally phase variable (43). Another example illustrates that mutations in homopolymeric tracts within the promoter gene of a symbiont can affect host fitness: a single-base polymorphism of a gene coding for a heat shock protein in the obligate bacterial symbiont Buchnera has the potential to allow pea aphid populations to adapt quickly to prevailing conditions (44).

There may be more layers of complexity to the regulation of sabA. While this study and those of others have begun to characterize the relationship between SabA and the TCS ArsRS, there may yet be other regulatory proteins affected by the changing DNA topology resulting from increases and decreases in the sabA poly(T) tract length. The results of our study will aid in a more complete understanding of sabA regulation in H. pylori and the further study of other adhesins, as well as in the understanding of adaptive evolution in pathogens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant R15 AI053062 to M.H.F. This research also was supported in part by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant through the Undergraduate Biological Sciences Education Program to the College of William and Mary.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 July 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01956-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. 2006. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:449–490. 10.1128/CMR.00054-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. 2009. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J. Clin. Investig. 119:2475–2487. 10.1172/JCI38605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wroblewski LE, Peek RM, Wilson KT. 2010. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:713–739. 10.1128/CMR.00011-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menaker RJ, Sharaf AA, Jones NL. 2004. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: host, bug, environment, or all three? Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 6:429–435. 10.1007/s11894-004-0063-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backert S, Clyne M. 2011. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 16:19–25. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Posselt G, Backert S, Wessler S. 2013. The functional interplay of Helicobacter pylori factors with gastric epithelial cells induces a multi-step process in pathogenesis. Cell Commun. Signal. 11:77. 10.1186/1478-811X-11-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odenbreit S. 2005. Adherence properties of Helicobacter pylori: impact on pathogenesis and adaptation to the host. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295:317–324. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aspholm M, Kalia A, Ruhl S, Schedin S, Amqvist A, Lindén S, Sjöström R, Gerhard M, Semino-Mora C, Dubois A, Unemo M, Danielsson D, Teneberg S, Lee WK, Berg DE, Borén T. 2006. Helicobacter pylori adhesion to carbohydrates. Methods Enzymol. 417:293–339. 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)17020-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aspholm M, Olfat FO, Nordén J, Sondén B, Lundberg C, Sjöström Altraja S, Odenbreit S, Haas R, Wadström T, Engstrand L, Semino-Mora C, Liu H, Dubois A, Teneberg S, Arnqvist A, Borén T. 2006. SabA is the H. pylori hemagglutinin and is polymorphic in binding to sialylated glycans. PLoS Pathog. 2:e110. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahdavi J, Sondén B, Hurtig M, Olfat FO, Forsberg L, Roche N, Angstrom J, Larsson T, Teneberg S, Karlsson KA, Altraja S, Wadström T, Kersulyte D, Berg DE, Dubois A, Petersson C, Magnusson KE, Norberg T, Lindh F, Lundskog BB, Arnqvist A, Hammarström L, Borén T. 2002. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science 297:573–578. 10.1126/science.1069076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin AC, Weinberger DM, Ford CB, Nelson JC, Snider JD, Hall JD, Paules CI, Peek PM, Forsyth MF. 2008. Expression of the Helicobacter pylori adhesin SabA is controlled via phase variation and the ArsRS signal transduction system. Microbiology 154:2231–2240. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/016055-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talarico S, Whitefield SE, Fero J, Haas R, Salama NR. 2012. Regulation of Helicobacter pylori adherence by gene conversion. Mol. Microbiol. 84:1050–1061. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08073.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao C, Sheu S, Sheu B, Wu J. 2012. Length of thymidine homopolymeric repeats modulates promoter activity of sabA in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 17:203–209. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skoog EC, Sjöling Å, Navabi N, Holgersson J, Lundin SB, Lindén SK. 2012. Human gastric mucins differently regulate Helicobacter pylori proliferation, gene expression, and interactions with host cells. PLoS One 7:e36378. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries N, Duinsbergen D, Kuipers EJ, Pot RG, Wiesenekker P, Penn CW, van Vliet AH, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Kusters JG. 2002. Transcriptional phase variation of a type III restriction-modification system in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184:6615–6623. 10.1128/JB.184.23.6615-6624.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma CM, Hoffman S, Darfeuille F, Reignier J, Findeiss S, Sittka A, Chabas S, Reiche K, Hackermüller J, Reinhardt R, Stadler PF, Vogel J. 2010. The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 464:250–255. 10.1038/nature08756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen Y, Feng J, Scott DR, Marcus EA, Sachs G. 2006. Involvement of the HP0165-HP0166 two-component system in expression of some acidic-pH-upregulated genes of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 188:1750–1761. 10.1128/JB.188.5.1750-1761.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pflock M, Dietz P, Schär J, Beier D. 2004. Genetic evidence for histidine kinase HP165 being an acid sensor of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 234:51–61. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsyth MH, Cao P, Garcia PP, Hall JD, Cover TL. 2002. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling in a histidine kinase mutant of Helicobacter pylori identifies members of a regulon. J. Bacteriol. 184:4630–4635. 10.1128/JB.184.16.4630-4635.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loh JT, Gupta SS, Friedman DB, Krezel AM, Cover TL. 2010. Analysis of protein expression regulated by the Helicobacter pylori ArsRS two-component signal transduction system. J. Bacteriol. 192:2034–2043. 10.1128/JB.01703-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller S, Götz M, Beier D. 2009. Histidine residue 94 is involved in pH sensing by histidine kinase ArsS of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS One 4:e6930. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pflock M, Finsterer N, Joseph B, Mollenkopf H, Meyer TF, Beyer D. 2006. Characterization of the ArsRS regulon of Helicobacter pylori, involved in acid adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 188:3449–3462. 10.1128/JB.188.10.3449-3462.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joseph B, Beier D. 2007. Global analysis of two-component gene regulation in H. pylori by mutation analysis and transcriptional profiling. Methods Enzymol. 423:514–530. 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)23025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beier D, Frank R. 2000. Molecular characterization of two-component systems of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 182:2068–2076. 10.1128/JB.182.8.2068-2076.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suter B, Schnappauf G, Thoma F. 2000. Poly(dAŸdT) sequences exist as rigid DNA structures in nucleosome-free yeast promoters in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4083–4089. 10.1093/nar/28.21.4083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurens N, Rusling D, Pernstich Brouwer CI, Halford S, Wuite GJL. 2012. DNA looping by FokI: the impact of twisting and bending rigidity on protein-induced looping dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:4988–4997. 10.1093/nar/gks184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Taylor DE. 1990. Chloramphenicol resistance in Campylobacter coli: nucleotide sequence, expression, and cloning vector construction. Gene 94:23–28. 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ando T, Israel DA, Kusugami K, Blaser MJ. 1999. HP0333, a member of the dprA family, is involved in natural transformation in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 181:5572–5580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallinger DR, Romero-Gallo J, Peek RM, Forsyth MH. 2012. Polymorphisms of the acid sensing histidine kinase gene arsS in Helicobacter pylori populations from anatomically distinct gastric sites. Microb. Pathog. 53:227–233. 10.1016/j.micpath.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alm RA, Ling LS, Moir DT, King BL, Brown ED, Doig PC, Smith DR, Noonan B, Guild BC, de Jonge BL, Carmel G, Tummino PJ, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills DM, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills SD, Jiang Q, Taylor DE, Vovis GF, Trust TJ. 1999. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397:176-180. 10.1038/16495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orsi RH, Bowen BM, Wiedmann M. 2010. Homopolymeric tracts represent a general regulatory mechanism in prokaryotes. BMC Genomics 11:102. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wernegreen JJ, Kauppinen SN, Degnan PH. 2010. Slip into something more functional: selection maintains ancient frameshifts in homopolymeric sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27:833–839. 10.1093/molbev/msp290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlahovicek K, Kaján L, Pongor S. 2003. DNA analysis servers: plot.it, bend.it, model.it and IS. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3686–3687. 10.1093/nar/gkg559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poore CA, Mobley HL. 2003. Differential regulation of the Proteus mirabilis urease gene cluster by UreR and H-NS. Microbiology 149:3383–3394. 10.1099/mic.0.26624-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estrem ST, Gaal T, Ross W, Gourse RL. 1998. Identification of an UP element consensus sequence for bacterial promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:9761–9766. 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Estrem ST, Ross W, Gaal T, Chen ZW, Niu W, Ebright RH, Gourse RL. 1999. Bacterial promoter architecture: subsite structure of UP elements and interactions with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Genes Dev. 13:2134–2147. 10.1101/gad.13.16.2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness EF, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak HG, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald LM, Lee N, Adams MD, Hickey EK, Berg DE, Gocayne JD, Utterback TR, Peterson JD, Kelley JM, Cotton MD, Weidman JM, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes WS, Borodovsky M, Karp PD, Smith HO, Fraser CM, Venter JC. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388:539–547. 10.1038/41483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamaoka Y. 2008. Increasing evidence of the role of Helicobacter pylori SabA in the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal disease. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2:174–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unemo M, Aspholm-Hurtig M, Llver D, Bergström Borén T, Danielsson D, Teneberg S. 2005. Sialic acid binding SabA adhesin of Helicobacter pylori is essential for nonosponic activation of human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 280:15390–15397. 10.1074/jbc.M412725200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odenbreit S, Swoboda K, Barwig I, Ruhl S, Borén T, Koletzo S, Haas R. 2009. Outer membrane protein expression profile in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 77:3782–3790. 10.1128/IAI.00364-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennemann L, Brenneke B, Andres S, Engstrand L, Meyer TF, Aebischer T, Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. 2012. In vivo sequence variation in HopZ, a phase-variable outer membrane protein of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 80:4364–4373. 10.1128/IAI.00977-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snyder LA, Loman NJ, Linton JD, Langdon RR, Weinstock GM, Wren BW, Pallen MJ. 2010. Simple sequence repeats in Helicobacter canadensis and their role in phase variable expression and C-terminal sequence switching. BMC Genomics 11:67. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke GR, McLaughlin HJ, Simon J, Moran N. 2010. Dynamics of a recurrent Buchnera mutation that affects thermal tolerance of pea aphid hosts. Genetics 186:367–372. 10.1534/genetics.110.117440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.