Abstract

There is no standard method for the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection (PJI). The contribution of 16S rRNA gene PCR sequencing on a routine basis remains to be defined. We performed a prospective multicenter study to assess the contributions of 16S rRNA gene assays in PJI diagnosis. Over a 2-year period, all patients suspected to have PJIs and a few uninfected patients undergoing primary arthroplasty (control group) were included. Five perioperative samples per patient were collected for culture and 16S rRNA gene PCR sequencing and one for histological examination. Three multicenter quality control assays were performed with both DNA extracts and crushed samples. The diagnosis of PJI was based on clinical, bacteriological, and histological criteria, according to Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines. A molecular diagnosis was modeled on the bacteriological criterion (≥1 positive sample for strict pathogens and ≥2 for commensal skin flora). Molecular data were analyzed according to the diagnosis of PJI. Between December 2010 and March 2012, 264 suspected cases of PJI and 35 control cases were included. PJI was confirmed in 215/264 suspected cases, 192 (89%) with a bacteriological criterion. The PJIs were monomicrobial (163 cases [85%]; staphylococci, n = 108; streptococci, n = 22; Gram-negative bacilli, n = 16; anaerobes, n = 13; others, n = 4) or polymicrobial (29 cases [15%]). The molecular diagnosis was positive in 151/215 confirmed cases of PJI (143 cases with bacteriological PJI documentation and 8 treated cases without bacteriological documentation) and in 2/49 cases without confirmed PJI (sensitivity, 73.3%; specificity, 95.5%). The 16S rRNA gene PCR assay showed a lack of sensitivity in the diagnosis of PJI on a multicenter routine basis.

INTRODUCTION

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is one of the most serious complications of orthopedic surgery, increasing the risk of morbidity and death for this very frequent operation. The infection rates are estimated to be about 1% for hip or shoulder replacement and about 2% for knee prosthesis (1). Despite the lack of a standard definition of PJI, bacterial documentation remains the cornerstone of diagnosis.

Bacterial adherence to biomaterials and tissues adjacent to prostheses is essential for the development of PJI (1). Bacteriological diagnosis requires the extraction of bacteria from a periprosthetic tissue biofilm. Culture of prosthetic sonicate fluid was more sensitive than traditional tissue culture when antibiotic treatment was stopped within 14 days before surgery (75% versus 45%; P < 0.001) (2). Nevertheless, the conventional bacteriological method used, in comparison with sonication, was simple homogenization of tissue specimens before culture (2). Recently, bacterial extraction using bead mill processing of specimens improved bacteriological diagnosis of PJI (3).

Histological examination of periprosthetic tissue is recommended if there is any suspicion of PJI (4, 5). The standard method is based on counts of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) per high-power field (HPF). The cutoff point (number of neutrophils per field) to affirm infection differed among authors, but the criterion of ≥5 PMN/HPF described by Mirra et al. and adapted by Feldman et al. remains the most commonly used (6–8).

Broad-range 16S rRNA gene PCR analysis has already been evaluated for the diagnosis of PJI; 16S rRNA gene PCR assays of periprosthetic tissue or periprosthetic sonicate fluid samples showed a wide range of sensitivity and specificity values, from 50 to 92% and from 65 to 94%, respectively (9–15). Compared with conventional culture, the sensitivity of 16S rRNA gene PCR analysis was higher, lower, or equivalent, sometimes to the detriment of specificity (9–15). More-recent studies on 16S rRNA gene PCR assays of periprosthetic sonicate fluids have also shown contradictory results. In one study, 16S rRNA gene PCR analysis and culture of sonicate fluid were shown to have equivalent performance results for PJI diagnosis (16). In another study, 16S rRNA gene PCR assays of periprosthetic tissue or sonicate fluid samples did not diagnose more PJI cases than did culture of adequate periprosthetic tissue samples (17). Finally, a recent study found greater sensitivity with a multiplex PCR panel, including anaerobic bacteria, applied to implant-derived sonicate fluid samples (18). These contradictory results may be due to different pretreatment procedures applied to samples before DNA extraction, different numbers of samples per patient, and use of the largest panel of bacteria, especially anaerobes (such as Propionibacterium acnes, which is often missed by 16S rRNA gene PCR assays). The wide range of PCR assay performance in different single-center studies underlines the interest in multicenter protocols for evaluation of 16S rRNA gene PCR analysis.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) provided recent guidelines assessing definitive evidence of PJI when perioperative surgical features of infection were observed, with multiple tissue specimens found to be positive in culture (4). At the end of the IDSA guidelines, gaps in information were identified, such as the role of PCR assays and bead mill processing in the diagnosis of PJI on a routine basis (4).

The main objective of our study was to assess the contributions of 16S rRNA gene PCR assays to PJI diagnosis. Our network organization for the multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment of bone and joint infections in seven referral centers was used to achieve the first prospective multicenter study related to the molecular diagnosis of PJI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This study was designed as a multicenter, prospective, observational, cross-sectional study of adult patients suspected to have PJIs. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at every site. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before inclusion.

Study population.

Consecutive patients with clinical signs suggesting acute or chronic PJI in 7 French university hospitals between December 2010 and March 2012 were included. Five patients per center who were undergoing primary total arthroplasty, with no history of joint surgery, during the same study period were also included, and their tissue samples were processed as negative controls for the PCR and culture procedures. Six tissue samples were collected during surgery, i.e., five samples for culture and PCR and one periprosthetic membrane sample for histological analysis. Case report forms were created for collection of the following data for each patient: patient characteristics, arthroplasty localization, presentation of infection, and antibiotic treatment in the 15 days before surgery.

Definition of PJI.

Acute PJI was suspected for patients with pain, disunion, necrosis, or inflammation of the scar in the months following prosthesis implantation. Chronic infection was suspected in the presence of chronic pain without systemic symptoms, as well as a loosened prosthesis (4, 5). According to the IDSA guidelines, PJI was diagnosed when at least one of the following criteria was positive: (i) clinical evidence with the presence of a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis and/or purulence around the prosthesis, (ii) histological results positive for infection (as specified above), and/or (iii) bacteriological evidence of infection (as specified below).

Microbiological methods.

Cultures of periprosthetic tissue samples were performed in each center following a standardized protocol. For each patient, 5 perioperative specimens were collected in sterile vials with different surgical instruments. After the addition of 10 ml sterile water and 10 sterile stainless steel beads (4-mm diameter), the vials were shaken on a Retsch MM401 bead mill for 2.5 min, at 30 Hz. Two aliquots of each of the 5 bead-milled suspensions were collected for molecular assays. Aliquots (2 ml) were inoculated into a blood culture bottle and Schaedler anaerobic liquid broth, and both were incubated at 37°C. Three additional 50-μl aliquots were spread on a blood agar plate and a Polyvitex chocolate agar plate, both of which were incubated for 7 days at 37°C in 5% CO2, and a blood agar plate, which was incubated for 5 days at 37°C in an anaerobic atmosphere. The Schaedler anaerobic liquid broth was subcultured for 72 h on blood agar plates in an anaerobic atmosphere if cloudy (or systematically at the 14th day). Isolated bacteria were identified according to standard laboratory procedures. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed as recommended (http://eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints). The bacteriological results were considered positive if at least one culture yielded a strict pathogen (Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacteriaceae, or anaerobes) or two cultures yielded a pathogen that was a skin commensal (such as coagulase-negative staphylococci [CoNS] or Propionibacterium acnes) (4).

Histological analysis.

The periprosthetic membrane samples were fixed in buffered formalin, and paraffin block sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Using the criteria described by Feldman et al. (adapted from the criteria described by Mirra et al.), the histological results were considered positive for infection when at least 5 neutrophils per high-power field (magnification, ×400) were found with examination of at least five separate microscopic fields (6, 7). The specimens were examined by pathologists who were blinded to the presence of infection and the results of the cultures.

Molecular methods.

PCR assays of periprosthetic tissue specimens were performed in a highly standardized manner with the 5 patient samples. All PCRs were performed in parallel with cultures from the same bead-milled suspension. A 200-μl aliquot of each bead-milled suspension was treated with proteinase K (2 g/liter) for 3 h at 65°C. Then, DNA extraction was performed using Qiagen manual extraction (4 laboratories) or automated extraction (3 laboratories, using MagNA Pure [Roche], EasyMag [bioMérieux], and iPrep [Invitrogen] systems). Real-time PCR was performed with Sybr green to target the 5′ part of the 16S rRNA gene (forward primer 27F, 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3′; reverse primer 685R3, 5′-TCT RCG CAT TYC ACC GCT AC-3′; 658-bp amplification product; GenBank accession number NR_024570). The corresponding amplicons were sequenced in both strands and assembled, and the consensus sequences were compared with those in the Bioinformatics Bacteria Identification (BIBI) and BLAST databases. The rates of concordance between 16S rRNA gene PCR and bacteriological results were based on results at the genus (≥96% similarity) and species (≥98% similarity) levels. A negative control and a positive control with Roseomonas DNA were assayed in parallel with each series of 5 samples per patient. A fragment of the human beta-globin gene was amplified for each negative sample, to control for DNA extraction and to confirm the absence of PCR inhibitors. All specimens for which inhibition was observed were diluted 1:10 and retested. Patients with inhibitors in at least two specimens were excluded from analysis. The criterion for molecular diagnosis was modeled on the bacteriological criterion (≥1 positive sample for strict pathogens and ≥2 positive samples for commensal skin flora). Molecular data were analyzed according to the diagnosis of PJI.

A multicenter external quality control (MEQC) assay was set up to validate the 16S rRNA gene PCR results obtained with the diverse molecular laboratory equipment. Three sets of samples, including 4 bacterial DNA extracts and 4 bead-milled osteoarticular tissue specimens, were sent to each laboratory, in November 2010, June 2011, and March 2012.

Statistical analysis.

Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges. Molecular data were analyzed using numbers and percentages according to the number of confirmed PJIs or unconfirmed PJIs. The sensitivity and specificity of the 16S rRNA gene PCR were estimated with 95% exact confidence intervals.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

Three hundred five patients were included and 6 were excluded, yielding 299 patients for analysis (Table 1). There were 264 suspected cases of PJI and 35 controls. Of the suspected cases of PJI, 127 (48%) occurred in male patients, and the median age at the time of diagnosis was 73 years. The suspected cases of PJI included 165 hip arthroplasty infections (63%) and 88 knee arthroplasty infections (33%). The patients presented with symptoms of acute infection in 19% of cases and chronic infection in 81% of cases. Seventy-six patients (29%; 19 with acute PJIs and 57 with chronic PJIs) received antibiotics for 2 weeks before surgery.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 299 patients analyzed

| Variable | Control (n = 35) | Suspected PJI (n = 264) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (yr [interquartile range]) | 70 (63–77) | 73 (63–79) |

| Male (no. [%]) | 23 (66) | 127 (48) |

| Location of arthroplasty (no. [%]) | ||

| Hip | 23 (66) | 165 (63) |

| Knee | 12 (34) | 88 (33) |

| Shoulder | 0 | 10 (4) |

| Elbow | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Presentation of infection (no. [%]) | ||

| Acute | 0 | 50 (19) |

| Chronic | 0 | 214 (81) |

| Antimicrobial therapy over 15 days before surgery (no. [%])a | 0 | 76 (29) |

| β-Lactams | 0 | 44 (58) |

| Fluoroquinolones | 0 | 16 (20) |

| Vancomycin | 0 | 12 (16) |

| Other antibioticsb | 0 | 25 (33) |

Some patients received two antibiotics.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, n = 11; rifampin, n = 9; others, n = 5.

Diagnosis of infection.

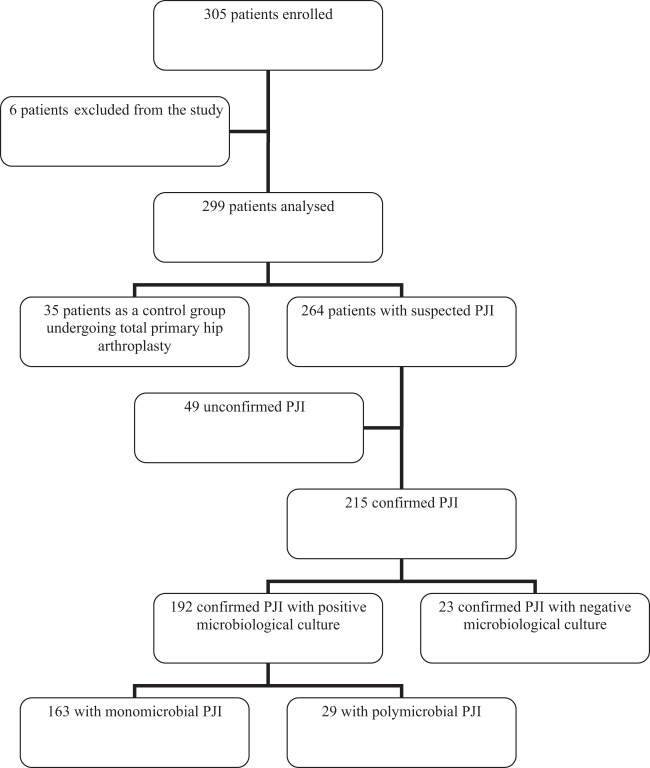

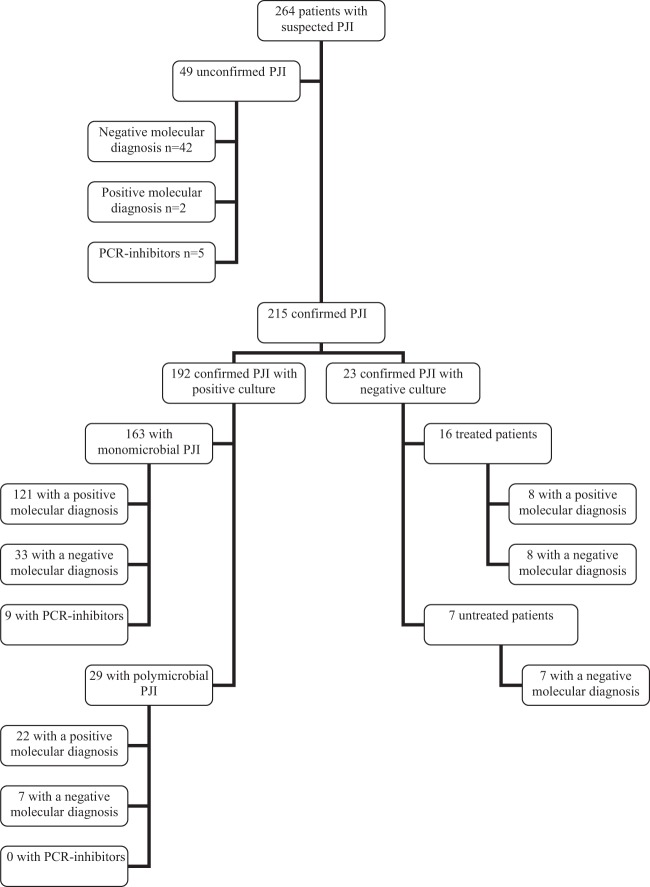

After analysis of clinical, bacteriological, and histological findings, a definitive diagnosis of infection was confirmed in 215 of 264 suspected cases of PJI (Fig. 1). Of the 215 patients with confirmed PJIs, 192 (89%) had positive bacteriological findings, monomicrobial in 163 cases (85%; 35 acute and 128 chronic infections) and polymicrobial in 29 cases (15%; 10 acute and 19 chronic infections) (Table 2). Of the monomicrobial infections, staphylococci were isolated in 108 cases (66%), streptococci and enterococci in 22 cases (13.5%), Gram-negative bacilli in 16 cases (10%), anaerobes in 13 cases (8%), and other bacteria in 4 cases (2.5%) (Table 2). The 29 polymicrobial infections were caused by 2 bacterial species in 22 cases and 3 or 4 species in the remaining 7 cases (Table 3). Cultures remained sterile for 23 confirmed cases of PJI, including 16 patients (70%) being treated with antibiotics at the time of surgery (Fig. 2). Forty-nine patients showed no clinical, bacteriological, or histological evidence of infection. The diagnosis of PJI could not be confirmed postoperatively in those cases, which were considered aseptic failures.

FIG 1.

Flow chart of enrolled patients. Six patients were excluded for the following reasons: inclusion criteria not met (n = 4), microbiological protocol not respected (n = 1), and patient included twice (n = 1). The 35 control patients had negative culture results. The 49 unconfirmed cases of PJI had no clinical, bacteriological, or histological evidence.

TABLE 2.

Results of 16S rRNA gene PCR assays and cultures for 192 microbiologically documented infections

| Organism | No. (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiologically documented PJI | Available PCR results | Positive PCR results | |

| S. aureus | 63 (33) | 62 (34) | 56 (39) |

| CoNSa | 45 (23) | 39 (21) | 25 (17.5) |

| Polymicrobial infection | 29 (15) | 29 (16) | 22 (15.5) |

| Streptococcib | 19 (10) | 19 (10) | 19 (13) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Gram-negative bacillic | 16 (8) | 16 (9) | 12 (8.5) |

| Anaerobesd | 13 (7) | 11 (6) | 4 (3) |

| Othere | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Total | 192 | 183f | 143 |

S. epidermidis, n = 31; S. lugdunensis, n = 6; Staphylococcus capitis, n = 4; Staphylococcus simulans, n = 2; Staphylococcus caprae, n = 1; Staphylococcus haemolyticus, n = 1.

S. agalactiae, n = 7; Streptococcus dysgalactiae, n = 3; Streptococcus mitis group, n = 4; S. milleri group, n = 3; Streptococcus pneumoniae, n = 1; Streptococcus salivarius, n = 1.

Escherichia coli, n = 5; Klebsiella, n = 3; Enterobacter cloacae, n = 2; Proteus mirabilis, n = 2; P. aeruginosa, n = 4.

P. acnes, n = 10; Propionibacterium avidum, n = 1; Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus, n = 1; Parvimonas micra, n = 1.

Listeria monocytogenes, n = 2; Corynebacterium amycolatum, n = 1; Bacillus cereus, n = 1.

Nine patients demonstrated PCR inhibitors.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of 16S rRNA gene PCR assay and culture results for 29 polymicrobial infections

| Culture results | No. of infections | No. with available PCR results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive |

Negative | ||||

| 1 bacterium | 2 bacteriaa | Uninterpretableb | |||

| 2 bacteria | 22c | 14 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 3 bacteria | 3d | 2 | 1 | ||

| 4 bacteria | 4d | 3 | 1 | ||

| Total | 29 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

One patient had 1 sample positive by PCR for Staphylococcus aureus and another sample positive for Streptococcus oralis.

Results were uninterpretable because of unreadable sequences.

Twenty-two polymicrobial infections involved 2 different bacteria, i.e., 2 different staphylococcal species (n = 3), staphylococci with anaerobes (n = 5), staphylococci with Enterobacteriaceae (n = 5), staphylococci with P. aeruginosa (n = 1), staphylococci with streptococci or enterococci (n = 4), staphylococci with corynebacteria (n = 2), E. coli with P. aeruginosa (n = 1), or Finegoldia magna with Anaerococcus vaginalis (n = 1).

Seven polymicrobial infections were due to 3 or 4 bacteria, involving Gram-positive cocci in association with Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes.

FIG 2.

Molecular results. The 49 unconfirmed cases of PJI had no clinical, bacteriological, or histological evidence. Two patients with positive PCR results for Listeria monocytogenes or Staphylococcus aureus had been treated with antibiotics several months previously for PJIs caused by these bacteria. The diagnosis of 215 cases of PJI was confirmed according to guidelines.

Analysis of 16S rRNA gene PCR assay results.

Of the 192 confirmed PJIs with bacteriological documentation, the molecular diagnosis was positive for 143 PJIs (121 monomicrobial and 22 polymicrobial infections), negative for 40 PJIs, and uninterpretable for 9 PJIs, owing to the presence of PCR inhibition (Fig. 2). Of the 40 bacteriologically documented PJIs with negative molecular diagnoses, 33 were monomicrobial infections with Staphylococcus epidermidis (n = 10), Staphylococcus lugdunensis (n = 4), P. acnes (n = 7), S. aureus (n = 6), Enterobacter cloacae (n = 1), Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 1), Proteus mirabilis (n = 1), P. aeruginosa (n = 1), Enterococcus faecalis (n = 1), or Corynebacterium amycolatum (n = 1); among them, 8 patients had a single specimen positive for the same bacterium in the PCR assay as in culture (S. epidermidis, n = 4; S. lugdunensis, n = 2; P. acnes, n = 2); the remaining 7 bacteriologically documented PJIs with negative molecular diagnoses were polymicrobial infections. Regarding polymicrobial infections with positive molecular diagnoses, sequencing of 16S rRNA gene PCR products found one bacterium in 19 cases, 2 bacteria in 1 case, and uninterpretable results due to unreadable sequences in 2 cases (Table 3).

Of the 23 confirmed PJIs that remained negative in culture, the molecular diagnoses were positive for 8 of 16 patients treated with antibiotics at the time of surgery and negative for 7 patients who did not receive antibiotics (Fig. 2). Of the 49 patients without confirmed diagnoses of PJI, the molecular diagnoses were positive in 2 cases, negative for 42 PJIs, and uninterpretable for 5 PJIs owing to PCR inhibitors (Fig. 2). The patients with positive PCR results for Listeria monocytogenes and S. aureus had been treated with antibiotics several months earlier for previous PJIs due to these bacteria; they were not treated after the current operations. In 3 of 49 unconfirmed PJIs, 1 of 5 samples was PCR positive for Acinetobacter johnsonii, Corynebacterium lipophiloflavum, or P. acnes. The sensitivity and specificity of the 16S rRNA gene PCR assay according to the diagnosis of PJI were 73.3% (95% confidence interval, 66.7 to 79.2%) and 95.5% (95% confidence interval, 84.5 to 99.4%), respectively.

In the external quality control assay, 160/168 quality controls (one laboratory did not participate in the first quality control series) could be analyzed, including 80 DNA extracts and 80 crushed samples. The overall rate of correct answers was 93.8% (150/160 samples), with the same proportions for bacterial DNA extracts and crushed samples. Our results showed that manual and automated extraction methods had similar performance results for osteoarticular specimens, whatever equipment was used for the 16S rRNA gene PCR assays.

Control patient analysis.

All 35 control patients were found to be negative by culture. Among them, the molecular diagnoses were negative for 33 patients and uninterpretable for 2 patients owing to the presence of PCR inhibitors.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first prospective multicenter study to explore the performance of 16S rRNA gene PCR assays for a large number of PJIs. Clinical, bacteriological, and histological criteria were chosen according to the latest IDSA guidelines on prosthetic joint infections (4). Molecular biology results were validated through a multicenter external quality control study, which will soon be submitted for publication. The correct results obtained uniformly showed that 16S rRNA gene PCR assays may be used with different types of laboratory equipment for molecular diagnosis of bone and joint infections. DNA samples were extracted from the same bead-milled suspensions used for the cultures. The PCR assays and cultures were performed with the five periprosthetic tissue samples collected for each patient included in the study. The criterion for molecular diagnosis was adapted from the bacteriological one, depending on whether the bacteria belonged to skin flora or were strict pathogens (4, 19).

One of the main findings from our study is the excellent specificity of our 16S rRNA gene PCR results. PCR results that were positive for environmental or skin bacteria and negative when assays were performed with the second DNA extract allowed us to eliminate rare cases of contamination. Samples that tested positive for S. aureus and L. monocytogenes using PCR were from two patients who had been treated for PJIs caused by these bacteria several months earlier. The persistence of DNA from nonviable bacteria several months after clinical cure has already been reported for infective endocarditis and is shown here for the first time for PJIs (20). The excellent specificity of broad-range PCR assays, when standard recommendations are followed to prevent contamination, was already reported in many other studies (11, 13–15).

A lack of sensitivity of broad-range PCR assays was observed in our multicenter study of a large number of patients with PJIs. Indeed, 16S rRNA gene PCR results were not contributory in the diagnosis of 64 confirmed cases of PJI (30%), including 40 cases with positive culture results. A number of cases (n = 8) had positive 16S rRNA gene PCR results for S. epidermidis, S. lugdunensis, or P. acnes for a single sample, which can be explained by the low bacterial inocula in chronic infections and thus the small amount of bacterial DNA in the extracts. One question that remains unresolved is whether the bacterium identified by the 16S rRNA gene PCR assay in a single sample is responsible for the infection. The lack of sensitivity of broad-range PCR assays was already shown in two previous studies, including 13 and 18 PJIs (11, 17), despite the use of pretreatment with lytic enzymes (proteinase K, lysozyme, lysostaphin, and mutanolysin) to ensure optimal lysis of bacteria (17).

Conversely, the PCR results became positive after DNA dilution for five patients with positive culture results, which highlighted the risk of PCR inhibition caused by excessively high DNA concentrations and the need to test diluted and undiluted DNA when performing PCR assays. Finally, of 16 patients who were receiving antibiotics at the time of surgery and had negative culture results, 8 also had negative PCR results, highlighting the lack of sensitivity of the 16S rRNA gene PCR system. Concerning polymicrobial infections, one potential benefit of 16S rRNA gene PCR assays may be the identification of all bacteria involved, which is time-consuming using traditional cultures. However, cloning of PCR products is often needed to analyze mixed sequence results, which is impossible to perform on a routine basis. Unfortunately, in our study, almost one-quarter of the polymicrobial PJIs yielded negative PCR results, and 66% tested positive for only one species.

Our study is the first multicenter study that proposes a multicenter homogenization of culture techniques. We chose a uniform number of samples, with many being collected at the bone-prosthesis interface. Using a bead mill provides better bacterial extraction from the tissue matrix. The bead-milled suspensions can be used to seed solid and culture media, and portions of the samples can be frozen for molecular tests. This approach enabled us to document the infection in 89% of cases, compared with 61% or 70% in other reported studies, and for 96% of patients who were not receiving antibiotics at the time of surgery (2, 18).

Concerning the distribution of bacteria in PJIs, our study confirms the predominance of staphylococci, which accounted for 56% of infections, and the same representations of Gram-negative bacilli (8%) and polymicrobial infections (15%) over the decades (1, 21–24). There was an almost-equal distribution between S. aureus and CoNS. Of the CoNS, S. lugdunensis was the second most frequently isolated species after S. epidermidis, confirming its strong virulence, as reported previously (25). Concerning streptococcal infections, our study confirms the importance of Streptococcus agalactiae and shows the existence of true PJIs caused by the Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus milleri groups (26). P. acnes infections represented 7% of monomicrobial anaerobic PJIs, which highlights its role in the pathogenicity of implant-associated infections (27). Considering the performance of the 16S rRNA gene PCR assay according to the different bacteria, sensitivity was excellent for S. aureus and streptococci, poorer for CoNS, and bad for P. acnes, as only 11% of P. acnes and 72% of CoNS infections were detected by PCR, compared with 92% and 100% of S. aureus and streptococci, respectively.

In conclusion, our prospective study demonstrated the reliability of routine 16S rRNA gene PCR assays through the use of multicenter quality control. However, its lack of sensitivity even in treated patients did not allow us to recommend the systematic use of the 16S rRNA gene PCR assay for optimal detection of microorganisms causing monomicrobial or polymicrobial PJIs. Finally, the use of other techniques in addition to cultures, such as multiplex PCR or pathogen-specific PCR assays, should be considered for infections that remain negative in culture (18, 28).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique Interrégionale grant API/N/041) and a grant from the Centre de Référence des Infections Ostéo-articulaires du Grand Ouest (CRIOGO).

We gratefully acknowledge Karine Fèvre and Line Happi for their help with the study and technical assistance. We are indebted to Jane Cottin (deceased) for her enthusiasm until the end. We are also very grateful to all members of the CRIOGO for their continuing support.

P.B., C.P., D.T., B.G., G.D.P., L. Bernard, and C.B. conceived and designed the study. P.B., C.P., D.T., A.S.V., A.J.-G., P.V., S.C., S.G., M.E.J., G.H.-A., C.L., M.K., L. Bret, R.Q., and C.B. were site investigators. J.L., B.G., and C.C. were study statisticians. P.B., C.P., D.T., A.S.V., A.J.-G., P.V., S.C., G.H.-A., C.L., M.K., L. Bernard, and C.B. wrote the paper. P.B. was the principal investigator.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

The CRIOGO Study Team members included J. Cottin (deceased), M. C. Rousselet, P. Bizot, and P. Abgueguen (CHU Angers); I. Quentin-Roue, R. Gérard, E. Stindel, and S. Ansart (CHU Brest); R. Boisson, A. Guilloux, L. Crémet, A. Moreau, S. Touchais, F. Gouin, D. Boutoille, and N. Asseray (CHU Nantes); A. Guigon, J. Guinard, P. Michenet, F. Razanabola, and C. Mille (CHU Orléans); A. S. Cognée, S. Milin, L. E. Gayet, F. Roblot, and G. Le Moal (CHU Poitiers); J. Guinard, N. Stock, J. L. Polard, and C. Arvieux (CHU Rennes); and P. Rosset and G. Gras (CHU Tours).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. 2004. Prosthetic-joint infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:1645–1654. 10.1056/NEJMra040181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Krishnan KU, Osmon DR, Mandrekar JN, Cockerill FR, Steckelberg JM, Greenleaf JF, Patel R. 2007. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:654–663. 10.1056/NEJMoa061588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roux AL, Sivadon-Tardy V, Bauer T, Lortat-Jacob A, Herrmann JL, Gaillard JL, Rottman M. 2011. Diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection by beadmill processing of a periprosthetic specimen. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:447–450. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson WR. 2013. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56:1–25. 10.1093/cid/cis966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Société de Pathologie Infectieuse de Langue Française. 2010. Recommendations for bone and joint prosthetic device infections in clinical practice (prosthesis, implants, osteosynthesis). Med. Mal. Infect. 40:185–211. 10.1016/j.medmal.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman DS, Lonner JH, Desai P, Zuckerman JD. 1995. The role of intraoperative frozen sections in revision total joint arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 77:1807–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirra JM, Marder RA, Amstutz HC. 1982. The pathology of failed total joint arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 170:175–183 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bori G, Soriano A, Garcia S, Gallart X, Mallofre C, Mensa J. 2009. Neutrophils in frozen section and type of microorganism isolated at the time of resection arthroplasty for the treatment of infection. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 129:591–595. 10.1007/s00402-008-0679-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandercam B, Jeumont S, Cornu O, Yombi JC, Lecouvet F, Lefèvre P, Irenge LM, Gala JL. 2008. Amplification-based DNA analysis in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J. Mol. Diagn. 10:537–543. 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panousis K, Grigoris P, Butcher I, Rana B, Reilly JH, Hamblen DL. 2005. Poor predictive value of broad-range PCR for the detection of arthroplasty infection in 92 cases. Acta Orthop. 76:341–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fihman V, Hannouche D, Bousson V, Bardin T, Lioté F, Raskine L, Riahi J, Sanson-Le Pors MJ, Bercot B. 2007. Improved diagnosis specificity in bone and joint infections using molecular techniques. J. Infect. 55:510–517. 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Man, FHR. Graber P, Lüem M, Zimmerli W, Ochsner PE, Sendi P. 2009. Broad-range PCR in selected episodes of prosthetic joint infection. Infection 37:292–294. 10.1007/s15010-008-8246-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenollar F, Roux V, Stein A, Drancourt M, Raoult D. 2006. Analysis of 525 samples to determine the usefulness of PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene for diagnosis of bone and joint infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1018–1028. 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1018-1028.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lévy PY, Fenollar F. 2012. The role of molecular diagnostics in implant-associated bone and joint infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:1168–1175. 10.1111/1469-0691.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marin M, Garcia-Lechuz M, Alonso P, Villanueva M, Alcala L, Gimeno M, Cercenado E, Sanchez-Somolinos M, Radice C, Bouza E. 2012. Role of universal 16S rDNA gene PCR and sequencing in diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:583–589. 10.1128/JCM.00170-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez E, Cazanave C, Cunningham SA, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Steckelberg JM, Uhl JR, Hanssen AD, Karau MJ, Schmidt SM, Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Mandrekar J, Patel R. 2012. Prosthetic joint infection diagnosis using broad-range PCR of biofilms dislodged from knee and hip arthroplasty surfaces using sonication. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3501–3508. 10.1128/JCM.00834-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bjerkan G, Witsø E, Nor A, Nor A, Viset T, Loseth K, Lydersen S, Persen L, Bergh K. 2012. A comprehensive microbiological evaluation of fifty-four patients undergoing revision surgery due to prosthetic joint loosening. J. Med. Microbiol. 61:572–581. 10.1099/jmm.0.036087-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cazanave C, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Hanssen AD, Karau MJ, Schmidt SM, Gomez Urena EO, Mandrekar JN, Osmon DR, Lough LE, Pritt BS, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. 2013. Rapid molecular microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:2280–2287. 10.1128/JCM.00335-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petti CA. 2007. Detection and identification of microorganisms by gene amplification and sequencing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1108–1114. 10.1086/512818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branger S, Casalta JP, Habib G, Collard F, Raoult D. 2003. Streptococcus pneumoniae endocarditis: persistence of DNA on heart valve material 7 years after infectious episode. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4435–4437. 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4435-4437.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Duffy MC, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS, Osmon DR. 1998. Risk factors for prosthetic joint infection: case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:1247–1254. 10.1086/514991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito S, Leone S. 2008. Prosthetic joint infections: microbiology, diagnosis, management and prevention. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 32:287–293. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cataldo MA, Petrosillo N, Cipriani M, Cauda R, Tacconelli E. 2010. Prosthetic joint infection: recent developments in diagnosis and management. J. Infect. 61:443–448. 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aslam S, Darouiche RO. 2012. Prosthetic joint infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 14:551–557. 10.1007/s11908-012-0284-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah NB, Osmon DR, Fadel H, Patel R, Kohner PC, Steckelberg JM, Mabry T, Berbari EF. 2010. Laboratory and clinical characteristics of Staphylococcus lugdunensis prosthetic joint infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1600–1603. 10.1128/JCM.01769-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corvec S, Illiaquer M, Touchais S, Boutoille D, van der Mee-Marquet N, Quentin R, Reynaud A, Lepelletier D, Bémer P. 2011. Clinical features of group B Streptococcus prosthetic joint infections and molecular characterization of isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:380–382. 10.1128/JCM.00581-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjerke-Kroll BT, Christ AB, McLawhorn AS, Sculco PK, Jules-Elysée KM, Sculco TP. 2014. Periprosthetic joint infections treated with two-stage revision over 14 years: an evolving microbiology profile. J. Arthroplasty 29:877–882. 10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy PY, Fournier PE, Fenollar F, Raoult D. 2013. Systematic PCR detection in culture-negative osteoarticular infections. Am. J. Med. 126:1143.e25–1143.e33. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]