Abstract

Authoritative guidelines state that the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) can be established using either endotracheal aspirate (ETA) or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) analysis, thereby suggesting that their results are considered to be in accordance. Therefore, the results of ETA Gram staining and semiquantitative cultures were compared to the results from a paired ETA-BALF analysis. Different thresholds for the positivity of ETAs were assessed. This was a prospective study of all patients who underwent bronchoalveolar lavage for suspected VAP in a 27-bed university intensive care unit during an 8-year period. VAP was diagnosed when ≥2% of the BALF cells contained intracellular organisms and/or when BALF quantitative culture revealed ≥104 CFU/ml of potentially pathogenic microorganisms. ETA Gram staining and semiquantitative cultures were compared to the results from paired BALF analysis by Cohen's kappa coefficients. VAP was suspected in 311 patients and diagnosed in 122 (39%) patients. In 288 (93%) patients, the results from the ETA analysis were available for comparison. Depending on the threshold used and the diagnostic modality, VAP incidences varied from 15% to 68%. For the diagnosis of VAP, the most accurate threshold for positivity of ETA semiquantitative cultures was moderate or heavy growth, whereas the optimal threshold for BALF Gram staining was ≥1 microorganisms per high power field. The Cohen's kappa coefficients were 0.22, 0.31, and 0.60 for ETA and paired BALF Gram stains, cultures, and BALF Gram stains, respectively. Since the ETA and BALF Gram stains and cultures agreed only fairly, they are probably not interchangeable for diagnosing VAP.

INTRODUCTION

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and costs (1, 2). Reliably diagnosing VAP is essential, as early and adequate antibiotic treatment lowers its mortality rate (3). Conversely, unnecessary antibiotic use may lead to redundant side effects and costs, and it promotes antibiotic resistance (4). Yet, a consensus on both the clinical definition and final diagnosis of VAP are still lacking (5, 6). Cultures of lower respiratory tract samples, such as protected specimen brush, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, or open-lung biopsy, have demonstrated high predictive value for the identification of VAP causative microorganisms and are frequently considered superior to endotracheal aspirates (ETAs) (7–12). In contrast, an ETA sample is more readily obtainable from mechanically ventilated patients and is frequently a component of microbiological surveillance (13). Since colonization precedes infection (14), bacteria identified by (surveillance) cultures of ETAs may indeed be the causative microorganisms once VAP develops (13). ETA nonquantitative cultures nevertheless lack a validated threshold for positivity and, consequently, they may not distinguish colonization from infection and may be nonindicative for VAP. Furthermore, their value in VAP management has been explored only in small and experimental studies, and their usefulness remains under debate (7, 13, 15). Whereas only a few guidelines discourage the use of ETAs for VAP diagnosis (16), the majority of VAP guidelines recommend the use of either ETA or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) analysis to diagnose VAP (17–19). These guidelines thereby suggest that the results of ETA and BALF analysis are in accordance.

This study compared ETA Gram staining and semiquantitative culture to paired BALF analysis results in patients with suspected VAP. Furthermore, the best thresholds for the positivity of ETA Gram staining, ETA semiquantitative cultures, and BALF Gram staining for VAP diagnosis were explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting.

The study was conducted in the Maastricht University Medical Center+, a 715-bed hospital with approximately 30,000 annual admissions and 27 intensive care unit (ICU) beds, including 9 for cardiothoracic surgery patients. Other elective postoperative patients are infrequently admitted because of a 24-h postanesthesia care unit at the hospital. When technically possible and safe, a BAL is performed in all mechanically ventilated patients who meet the clinical criteria of suspected VAP. These criteria include a rectal temperature of >38.0°C or <35.5°C, a white blood cell count of >10,000/μl or <3,000/μl, purulent sputum, and a new, persistent, or progressive infiltrate on chest X ray. In patients with localized pulmonary abnormalities, the affected region is sampled, whereas in cases of diffuse pulmonary abnormalities, the middle lobe or lingula is lavaged. Surveillance cultures of ETA are obtained twice weekly from all mechanically ventilated patients. Selective oropharyngeal decontamination (SOD) has been used since December 2011, whereas selective digestive tract decontamination, including SOD, has been used since December 2012.

The ethics committee of the institution approved the study, and informed consent was not necessary since standard care was provided.

Data collection.

The BALF results of all patients consecutively admitted to the ICUs from January 2005 up to December 2012 were prospectively included. The data concerning the length of mechanical ventilation were obtained from nurse logbooks, hospital electronic patient organizers, and/or chest X rays checked for the presence of an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube. In case a patient had multiple episodes of suspected VAP, only the first episode was included. The results of ETA analysis were collected from the laboratory information system. Preferably, the ETA sample obtained on the same day the BAL was performed was used for analysis. If the ETA sample was not obtained that day, an ETA sample was used according to the following ranking: the day before BAL, the day after BAL, or 2 days before BAL. Otherwise, an ETA was considered to be unavailable. The 3-day interval was chosen because significant changes in ETA results are unlikely to occur within this time frame, and this interval proved to be superior for antibiotic guidance than was a 7-day interval (20, 21). Paired ETA-BALF samples were subsequently compared.

Microbiological analysis.

ETA Gram stains were analyzed under high power field (magnification, ×1,000), and the results were expressed as the presence of specific bacteria, yeasts, and/or oropharyngeal flora. ETAs were cultured semiquantitatively, and growth was described as sporadic, few, moderate, or heavy. The results of the BALF Gram stain were expressed as the number of bacteria per high power field and quantified as none, 0 to 1, 1, or >1 microorganisms. BALF samples were excluded if one or more of the rejection criteria (as described elsewhere [22]) were fulfilled. The included BALF samples were subsequently analyzed according to a highly standardized protocol, as described elsewhere (23). This included the identification of intracellular organisms (ICOs) per 500 counted nucleated cells on May-Grünwald-Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations that were expressed as a percentage, and quantitative cultures were expressed as CFU/ml.

Definitions.

VAP was suspected in patients who met the clinical criteria when mechanically ventilated for >48 h in the 72 h before the BAL procedure. VAP was diagnosed in suspected cases when ≥2% of the BALF nucleated cells contained ICOs (10, 22, 24, 25) and/or the BALF quantitative cultures revealed ≥104 CFU/ml (26). However, commensal flora (Candida spp., coagulase-negative staphylococci, Corynebacterium spp., enterococci, Neisseria spp., oropharyngeal flora, viridans group Streptococcus, and yeasts) were considered nonpathogenic and subsequently classified as negative, which is consistent with previous studies and guidelines (7, 19, 27). Additionally, the rare growth of commensal flora in ETA cultures is presumed to be commonly present, leading to unfairly low specificity and positive predictive value in a comparison of any growth in ETA culture to significant growth in BALF culture. Three thresholds for positivity were assessed for the ETA cultures: any growth, moderate growth or greater, and heavy growth. For the BALF Gram stains, three thresholds were assessed: >none, ≥1, and >1 microorganisms per high power field.

Agreement analysis.

BALF-ETA paired samples were defined as identical in the Gram staining once the same potential pathogenic microorganism(s) were identified by both the ETA and paired BALF samples, regardless of quantification. When BALF Gram staining identified microorganisms (above the assessed threshold) that were subsequently identified by quantitative culture, the BALF Gram stain result was defined as true positive.

When the ETA growth reached the assessed threshold and the paired BALF quantitative culture identified identical microorganisms at ≥104 CFU/ml, the paired ETA-BALF sample was defined as true positive. In patients for whom the BALF analysis revealed ≥2% of the BALF cells containing ICOs without a subsequent identification of microorganisms at ≥104 CFU/ml, comparing these results with those of other tests is impossible; therefore, these cases were excluded for the agreement analysis. When the ETA and BALF results were partly similar, both the similarities and dissimilarities were appraised, but a paired ETA-BALF sample was always counted as one case. For example, when an ETA culture identified Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and the paired BALF culture identified only S. aureus, the ETA-BALF sample was considered half true positive and half false positive.

Statistics.

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values, including 95% confidence intervals, were calculated using the VAP diagnosis based on clinical criteria in combination with BALF analysis as the gold standard. Cohen's kappa coefficient was used to quantify the level of agreement between two diagnostic tests, where <0 indicates no agreement, 0 to 0.2 indicates slight agreement, 0.21 to 0.4 indicates fair agreement, 0.41 to 0.6 indicates moderate agreement, 0.61 to 0.8 indicates substantial agreement, and 0.81 to 1 indicates almost perfect agreement (28). The IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 for Windows (Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for analysis.

RESULTS

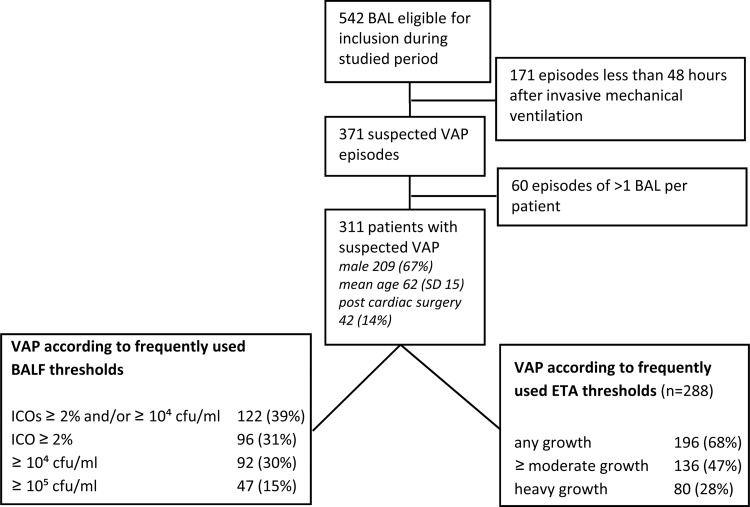

During the studied period, 542 BALs were performed (see Fig. 1 for a flow chart). One hundred seventy-one episodes were excluded, because these patients were mechanically ventilated for <48 h. After limiting the inclusion to the first BAL episode, 311 patients with suspected VAP remained. The median number of days the included patients were mechanically ventilated prior to the BAL procedure was nine. VAP was diagnosed in 122 (39%) patients. The VAP causative microorganisms are presented in Table 1. Eighteen VAP cases were caused by multiple microorganisms, mainly involving S. aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, or Streptococcus pneumoniae. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus was not identified. In 288 (93%) VAP suspected patients, the results of ETA analysis were available for the comparison analysis. The characteristics of the VAP suspected patients are presented in Fig. 1, which also contains VAP incidences according to frequently used thresholds for positivity of both ETA and BALF. The VAP rates were strongly dependent on the diagnostic modality used, as well as their applied threshold for positivity, and they varied from 15% (for BALF quantitative culture of ≥105 CFU/ml) to 68% (for any growth in ETA semiquantitative culture).

FIG 1.

Flow chart, including patient characteristics and incidences of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) using different diagnostic thresholds. BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; ETA, endotracheal aspirate; ICO, intracellular organisms; SD, standard deviation.

TABLE 1.

Identified microorganismsa

| Identified MO | Frequency of isolation (% of total) | No. with coinfection with 1 other MO | No. with coinfection with 2 other MO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 24 (20) | 4 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin sensitive) | 18 (15) | 6 | 2 |

| Escherichia coli | 15 (12) | 4 | |

| Klebsiella spp. | 12 (10) | 3 | 1 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 11 (9) | 5 | 1 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 7 (6) | 4 | 1 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 4 (3) | 1 | |

| Proteus mirabilis | 4 (3) | 1 | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 4 (3) | 1 | |

| Enterobacter spp. | 3 (2) | 2 | |

| Serratia spp. | 3 (2) | ||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 3 (2) | 1 | |

| Providencia rettgeri | 1 (1) | ||

| Citrobacter freundii | 1 (1) | 1 | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 (1) | ||

| Unidentifiedb | 29 (24) |

Ventilator-associated pneumonia causing microorganisms (MOs) identified by bronchoalveolar lavage in 122 patients, including the numbers of coinfection with other identified MOs.

Unidentified means that the BALF quantitative cultures did not reveal 104 CFU/ml or more of a potentially pathogenic microorganism, whereas the BALF cells contained ≥2% ICOs.

ETA Gram staining.

Gram stains were performed in 284 paired ETA-BALF samples. The results of the agreement analyses are presented in Table 2. The ETA Gram stain revealed a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of 65%, 72%, 52%, and 81%, respectively, for the diagnosis of VAP (according to BALF analysis). The Cohen's kappa coefficient was 0.34.

TABLE 2.

Gram stain agreement analysisa

| ETA Gram stain | No. of BALF samples with Gram stainb: |

Total | PPV/NPV (%)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | |||

| ETA Gram+ | 66 | 41 | 106 | PPV, 62 |

| ETA Gram− | 70 | 108 | 178 | NPV, 61 |

| Total | 135 | 149 | 284 | |

Gram stain of endotracheal aspirates (ETA) compared to that of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Sensitivity is 49% and specificity is 73%. The Cohen's kappa coefficient is 0.22.

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

ETA cultures.

The results of the cultures were available both from ETA and BALF samples in 268 VAP suspected patients. The results of the comparison of BALF and ETA arranged according to the different assessed thresholds are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2. The ETA sample was obtained on the same day as the BALF sample in 129 out of 288 patients (45%). Cohen's kappa for this subgroup revealed 0.21, 0.30, and 0.27 for any, moderate or heavy, or heavy growth, respectively, as thresholds for positivity.

TABLE 3.

Gram stain agreement analysis of cultures and BALFa

| Performance characteristic | Threshold for positive of (% [95% CI]): |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETA culture |

BALF Gram stain |

|||||

| Any | ≥Moderate | Heavy | >0 | ≥1 | > 1 | |

| SN | 82 (72–90) | 68 (57–78) | 40 (29–51) | 82 (72–89) | 64 (53–74) | 54 (43–65) |

| SP | 42 (35–49) | 66 (59–73) | 81 (74–86) | 66 (58–73) | 93 (88–96) | 96 (91–98) |

| PPV | 36 (29–44) | 48 (39–57) | 51 (38–63) | 51 (42–60) | 82 (71–90) | 86 (73–93) |

| NPV | 86 (77–92) | 82 (75–88) | 73 (66–79) | 89 (82–94) | 84 (79–89) | 80 (75–86) |

| Kappa | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

Sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and Cohen's kappa coefficient for level of agreement of semiquantitative cultures of endotracheal aspirates according to different thresholds, and BALF Gram stain according to different thresholds for positive results (in microorganisms per high power field) for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia (clinical signs and BALF of ≥104 CFU/ml and/or ≥2% BALF cells containing intracellular organisms).

FIG 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of endotracheal aspirate semiquantitative cultures according to different thresholds for positivity.

BALF Gram staining.

The BALF Gram stains of 266 VAP suspected patients were compared to the results of the BALF quantitative cultures. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and Cohen's kappa values for VAP for all three assessed BALF Gram thresholds are also provided in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study so far comparing ETA semiquantitative cultures to highly standardized BALF analysis in patients with suspected VAP. In the 311 explored VAP suspected cases, the VAP incidences were strongly depended on the diagnostic test used as well as on the thresholds for positivity, and they varied from 15% to 68%. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and H. influenzae were the most frequently identified VAP-causing microorganisms. Both ETA Gram staining and semiquantitative cultures revealed fair agreement with paired BALF Gram stain and quantitative cultures. The BALF Gram stain revealed moderate to substantial agreement with the subsequent quantitative cultures.

In the following paragraphs, the results are discussed through the perspective of the available literature.

Gram staining.

Gram staining of ETA and BALF revealed fair agreement. Compared to the BALF quantitative cultures, BALF Gram stain appeared to be more indicative for VAP than was the ETA Gram stain. The overall predictive capacity of the ETA Gram stain, despite its substantial NPV and promising suggestions from prior research (29), appeared too low to justify antibiotic modifications. Therefore, ETA Gram staining should be considered inferior and probably useless in the management of VAP. BALF Gram staining, with a threshold for positivity of ≥1 or perhaps >1 bacteria per high power field, revealed moderate to substantial agreement with the quantitative cultures. Goldberg et al. (30) compared the BALF Gram staining results of 229 suspected VAP cases with those of subsequent quantitative culture (threshold for positivity, >105 CFU/ml). With a threshold for positivity of >0 bacteria per high power field, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 90%, 67%, 45%, and 96%, respectively. When increasing the threshold for positivity to moderate or many microorganisms per high power field, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV became 58%, 89%, 62%, and 88%, respectively. These results are in accordance with the results from the present study. Although Goldberg et al. (30) were not in favor of BALF Gram stain use, with a threshold for positivity of ≥1 bacteria per high power field, its use will probably have an attributable value in VAP management, especially when an ICO count is not readily available. Below the threshold, VAP is unlikely (16%), and above the threshold, the initiation of antibiotic treatment is justified (PPV, 82%).

Cultures.

The agreement between the cultures of ETA and BALF was only fair as well (maximum Cohen's kappa, 0.31), indicating that ETA and BAL are not interchangeable diagnostic modalities. Indeed, in contrast to the current opinion, the VAP causative pathogen will not always be identified by ETA cultures. In 2000, 12 partially similar studies that explored the value of ETA qualitative and quantitative cultures with clinical diagnoses, protected specimen brush (PSB), BALF, or autopsy were compared (31). Overall, the sensitivity of the ETA qualitative cultures ranged from 38% to 100%, and specificity ranged from 14 to 100%. After this inconclusive review, few other studies compared ETA cultures to invasive quantitative cultures. Their results are summarized in Table 4. Because an internationally accepted threshold for the positivity of ETA quantitative cultures is so far lacking, values of ≥103 to ≥107 CFU/ml are used (17, 21, 31, 32). Using various thresholds for positivity in the studied population contributes to heterogeneity and thereby makes study results difficult to compare. This phenomenon can also be illustrated by looking at the present study, revealing VAP incidences from 15% to 68%, depending on the threshold used and the diagnostic modality.

TABLE 4.

Studies comparing ETA cultures to BALF quantitative cultures, including thresholds for positivity and predictive values

| Reference or source | Country | Patientsa | ETA (n) | Reference | Kappa | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%)b | NPV (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al., 2002 (44) | Taiwan | 48 suspected VAP | ≥105 CFU/ml | BALF, ≥104 CFU/ml, or PSB, ≥103 CFU/mld | BALF, 79%; PSB, 75% | BALF, 90% | |||

| Wood et al., 2003 (45) | USA | 90 suspected VAP | Moderate or heavy | BALF, ≥104 CFU/ml, or PSB, ≥103 CFU/ml | BALF, 0.54; PSB, 0.38 | ||||

| Mentec et al., 2004 (46) | France | 63 suspected VAP | ≥105 CFU/ml | BALF, ≥104 CFU/ml, or PSB, ≥103 CFU/ml | BALF, 0.36; PSB, 0.40 | ||||

| Mondi et al., 2005 (47) | USA | 61 intubated | ≥104 CFU/ml and ≥105 CFU/ml (39) | BALF, ≥105 CFU/ml | ≥104 CFU/ml, 70%; ≥105 CFU/ml, 75% | ≥104 CFU/ml, 92%; ≥105 CFU/ml, 87% | |||

| El Solh et al., 2007 (48) | USA | 75 suspected nursing home-acquired pneumonia requiring MV | Quantitative | BALF, ≥104 CFU/ml, or PSB, ≥103 CFU/ml | ≥103 CFU/ml, 98%; ≥104 CFU/ml, 90%; ≥105 CFU/ml, 78%; ≥106 CFU/ml, 51%; ≥107 CFU/ml, 18% | ≥103 CFU/ml, 35%; ≥104 CFU/ml, 77%; ≥105 CFU/ml, 84%; ≥106 CFU/ml, 92%; ≥107 CFU/ml, 100% | |||

| Fujitani et al., 2009 (49) | USA | 256 suspected VAP | Semiquantitative (256) | Nonbronchoscopic BAL, ≥104 CFU/ml | Any growth, 0.22; ≥light, 0.28; ≥moderate, 0.26; heavy, 0.22 | ||||

| Shin et al., 2011 (32) | South Korea | 17 suspected CAP, 28 suspected HAP | Quantitative | BALF, ≥104 CFU/ml | ≥105 CFU/ml, 0.64; ≥106 CFU/ml, 0.76; ≥107 CFU/ml, 0.22 | ||||

| This study | The Netherlands | 311 suspected VAP | Semiquantitative (289) | BALF, ≥104 CFU/ml | Any growth, 0.18; ≥moderate, 0.31; heavy, 0.22 |

VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; MV, mechanical ventilation; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia.

PPV, positive predictive value.

NPV, negative predictive value.

PSB, protected specimen brush.

A recent Cochrane systematic review (15) demonstrated no clinical advantage of invasive diagnostics with subsequent quantitative cultures over noninvasive diagnostics with subsequent nonquantitative cultures in patients with suspected VAP. This conclusion was based on three randomized controlled trials, of which the methods and results are summarized in Table 5. In one study, the administration of antibiotics directly depended on the results of invasive or noninvasive diagnostics (11). This study demonstrated better clinical outcomes in patients for whom invasive diagnostics were applied (11). The two other studies adopted a more defensive policy: all suspected VAP patients received broad-spectrum antibiotics, and antibiotic deescalation was hardly applied (27, 33). These antibiotic strategies were very exceptional in the present study, as they still are in most other Dutch hospitals (34). Furthermore, patients with P. aeruginosa and MRSA colonization or infection were excluded in one study (27), although these microorganisms are well-known causes of VAP. Indeed, only P. aeruginosa and MRSA necessitated antibiotic modification due to insusceptibility for empirical antibiotic treatment in one of the other included studies (33).

TABLE 5.

Results of invasive versus noninvasive diagnostic studiesa

| Reference | Country, yr | Setting and patients | Invasive | Noninvasive | Outcome | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solé Violán et al. (33) | Spain, 2000 | Single center; 88 suspected VAP patients | PSB and BAL or nonbronchoscopic BAL | ETA nonquantitative culture | More antibiotic spectrum narrowing (10 vs 3 [P < 0.05]) in invasive group | Invasive group more Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P < 0.05); broad-spectrum antibiotic always continued |

| Fagon et al. (11) | France, 2000 | Multicenter; 413 suspected VAP patients | BAL or PSB Gram stain and quantitative cultures | ETA Gram and qualitative cultures | Invasive group: more antibiotic-free days (5.0 vs 2.2 [P < 0.001]), more appropriate antibiotics (96% vs 87%), lower SOFA score at day 3 (6.1 vs 7.0 [P = 0.03]), lower mortality at day 14 (16% vs 26% [P = 0.02]) | Antibiotics when Gram stain identified bacteria or in case of severe sepsis |

| Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (27) | Canada, 2006 | 28 ICUs in USA and Canada; 739 suspected VAP patients | BAL quantitative cultures | ETA nonquantitative cultures | Equal mortality, antibiotic use, and clinical outcome | All patients received meropenem with/without ciprofloxacin; P. aeruginosa or MRSA were excluded; invasive group received antibiotics later (8.0 vs 6.6 h [P < 0.001]) |

Summary of the randomized trials used in the Cochrane systematic review (15) comparing the clinical use of invasive diagnostics with quantitative cultures and noninvasive diagnostics with nonquantitative cultures for diagnosing ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ETA, endotracheal aspirate; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment; PSB, protected specimen brush.

Intracellular organisms.

In 29 (24%) VAP cases, ≥2% of the BALF cells contained ICOs, whereas the quantitative cultures did not reveal significant bacterial growth. Compared to related studies, this percentage is rather high (24, 35, 36). This phenomenon might be explained by the visual artifacts on the May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining or, more likely, by antibiotic use. Antibiotics may kill the bacteria (resulting in the absence of growth) but do not readily diminish the number of cells containing ICOs, which may remain visible for two additional days (10, 22).

Extrapolation.

In addition to VAP diagnosis, BALF analysis is able to reveal several other causes of respiratory deterioration by means of cell count and specific staining. These may, for example, be nonbacterial, such as Aspergillus infection, cryptococcal infection, viral pneumonia, or noninfections, such as alveolar hemorrhage, bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, idiopathic lung fibrosis, and sarcoidosis (24, 37).

Overall, BAL and BALF analysis appeared to be preferred over ETA analysis for the diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment of VAP. Since the positive predictive value of ETA cultures is poor, antibiotic treatment based on their results ay probably initiates inappropriate antibiotic usage and thus increased antibiotic resistance. Prospective randomized trials are warranted to further establish the exact clinical relevance of the present findings. However, since VAP incidences are declining due to both VAP care bundles (38) and selective digestive tract decontamination (39), studies should include a substantial number of patients.

Limitations of the study.

Despite the size and prospective design, there are some limitations of the study. First, due to the lack of a globally accepted gold standard for diagnosing VAP (5, 6, 40), VAP in clinically suspected patients was defined as BALF analysis revealing ≥2% ICOs and/or significant growth (≥104 CFU/ml [41]) of potential pathogenic microorganisms. However, other authors (30, 42) suggest other BALF quantitative thresholds, such as >105 CFU/ml. A consequence of this definition is that cases in which BALF contained ≥2% ICOs, but no significant growth of a potential pathogenic microorganism needed to be excluded from the agreement analyses, as was previously indicated. Second, a limited number of clinical characteristics were prospectively collected and, consequently, a clinical pulmonary infection score and CDC classification could not be calculated and implemented. Information regarding which antibiotics were used in individual patients were not available. The clinical consequences in terms of antibiotic appropriateness or antibiotic overuse of an ETA-based strategy compared to a BAL-based strategy were consequently not assessed. Third, in case of multiple suspected VAP episodes in one patient, only the first episode of suspected VAP was included. Whether later episodes have a higher likelihood for VAP and should therefore have been included is unknown. Fourth and last, BALF cultures that exclusively identified significant growth of oropharyngeal flora were excluded as well, although oropharyngeal flora may be a relevant cause of VAP (43).

In conclusion, reported VAP incidences are strongly dependent on the diagnostic tests used and their predefined thresholds for positivity. ETA Gram staining and semiquantitative cultures, even when using different thresholds for positivity, revealed only fair agreement with BALF Gram staining and quantitative cultures. BALF Gram staining, with a threshold for positivity of one or more bacteria per high power field, had moderate to substantial agreement with quantitative cultures and might be useful for initial antibiotic guidance. In contrast to what is suggested in the authoritative guidelines, these results demonstrated that ETA and BALF Gram stains and cultures are not interchangeable for diagnosing VAP. In hospitals where BAL and BALF analysis are routine practice and thus are readily available, this diagnostic modality is probably more accurate and thus preferable over ETA analysis in patients with suspected VAP. Additionally, antibiotic treatment based on ETA results may lead to inappropriate antibiotic usage and thus increased antibiotic resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

W.N.K.A.V.M. initiated the study together with C.F.M.L. J.B.J.S. performed all statistical and initial interpretation of the results, wrote the first drafts of the manuscript, and coordinated the implementation of suggestions from the other authors. H.A.V.D. and C.F.M.L. prospectively collected and managed the database. W.N.K.A.V.M. and C.F.M.L. commented on the early versions of the manuscript. Thereafter, we all actively participated in discussions on the resulting drafts and provided multiple qualitative comments resulting in the final approved manuscript.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Safdar N, Dezfulian C, Collard HR, Saint S. 2005. Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit. Care Med. 33:2184–2193. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000181731.53912.D9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melsen WG, Rovers MM, Groenwold RH, Bergmans DC, Camus C, Bauer TT, Hanisch EW, Klarin B, Koeman M, Krueger WA, Lacherade JC, Lorente L, Memish ZA, Morrow LE, Nardi G, van Nieuwenhoven CA, O'Keefe GE, Nakos G, Scannapieco FA, Seguin P, Staudinger T, Topeli A, Ferrer M, Bonten MJ. 2013. Attributable mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised prevention studies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13:665–671. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70081-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luna CM, Aruj P, Niederman MS, Garzón J, Violi D, Prignoni A, Ríos F, Baquero S, Gando S, Grupo Argentino de Estudio de la Neumonía Asociada al Respirador Group 2006. Appropriateness and delay to initiate therapy in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 27:158–164. 10.1183/09031936.06.00049105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollef MH, Fraser VJ. 2001. Antibiotic resistance in the intensive care unit. Ann. Intern. Med. 134:298–314. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-4-200102200-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novosel TJ, Hodge LA, Weireter LJ, Britt RC, Collins JN, Reed SF, Britt LD. 2012. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: depends on your definition. Am. Surg. 78:851–854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter JD. 2012. Ventilator associated pneumonia. BMJ 344:e3325. 10.1136/bmj.e3325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medford AR, Husain SA, Turki HM, Millar AB. 2009. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J. Crit. Care 24:473 e471–e476. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Marshall J, Heule M, Guslits B, Lang J, Jaeschke R. 1999. The clinical utility of invasive diagnostic techniques in the setting of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Chest 115:1076–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giantsou E, Liratzopoulos N, Efraimidou E, Panopoulou M, Alepopoulou E, Kartali-Ktenidou S, Manolas K. 2007. De-escalation therapy rates are significantly higher by bronchoalveolar lavage than by tracheal aspirate. Intensive Care Med. 33:1533–1540. 10.1007/s00134-007-0619-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jaeger A, Litalien C, Lacroix J, Guertin MC, Infante-Rivard C. 1999. Protected specimen brush or bronchoalveolar lavage to diagnose bacterial nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated adults: a meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 27:2548–2560. 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagon JY, Chastre J, Wolff M, Gervais C, Parer-Aubas S, Stéphan F, Similowski T, Mercat A, Diehl JL, Sollet JP, Tenaillon A. 2000. Invasive and noninvasive strategies for management of suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 132:621–630. 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baselski V. 1993. Microbiologic diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 7:331–357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brusselaers N, Labeau S, Vogelaers D, Blot S. 2013. Value of lower respiratory tract surveillance cultures to predict bacterial pathogens in ventilator-associated pneumonia: systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 39:365–375. 10.1007/s00134-012-2759-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonten MJ, Weinstein RA. 1996. The role of colonization in the pathogenesis of nosocomial infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 17:193–200. 10.2307/30142385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berton DC, Kalil AC, Teixeira PJ. 2012. Quantitative versus qualitative cultures of respiratory secretions for clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1:CD006482. 10.1002/14651858.CD006482.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masterton RG, Galloway A, French G, Street M, Armstrong J, Brown E, Cleverley J, Dilworth P, Fry C, Gascoigne AD, Knox A, Nathwani D, Spencer R, Wilcox M. 2008. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the working party on hospital-acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:5–34. 10.1093/jac/dkn162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171:388–416. 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muscedere J, Dodek P, Keenan S, Fowler R, Cook D, Heyland D, VAP Guidelines Committee and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group 2008. Comprehensive evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for ventilator-associated pneumonia: prevention. J. Crit. Care 23:126–137. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raoof S, Baumann MH, Critical Care Societies Collaborative 2014. An official multi-society statement: ventilator-associated events: the new definition. Crit. Care Med. 42:228–229. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boots RJ, Phillips GE, George N, Faoagali JL. 2008. Surveillance culture utility and safety using low-volume blind bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respirology 13:87–96. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luna CM, Sarquis S, Niederman M, Sosa A, Otaola M, Bailleau N, Vay CA, Famiglietti A, Irrazabal C, Capdevila A. Is an endotracheal routine cultures-based strategy the best way to prescribe antibiotics in ventilator-associated pneumonia? Chest. 2013 doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linssen CF, Jacobs JA, Schouten JS, van Mook WN, Ramsay G, Drent M. 2008. Influence of antibiotic therapy on the cytological diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 34:865–872. 10.1007/s00134-008-1015-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Brauwer EI, Jacobs JA, Nieman F, Bruggeman CA, Wagenaar SS, Drent M. 2000. Cytocentrifugation conditions affecting the differential cell count in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 22:416–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timsit JF, Cheval C, Gachot B, Bruneel F, Wolff M, Carlet J, Regnier B. 2001. Usefulness of a strategy based on bronchoscopy with direct examination of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in the initial antibiotic therapy of suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 27:640–647. 10.1007/s001340000840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allaouchiche B, Jaumain H, Dumontet C, Motin J. 1996. Early diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Is it possible to define a cutoff value of infected cells in BAL fluid? Chest 110:1558–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres A, El-Ebiary M. 2000. Bronchoscopic BAL in the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 117:198S–202S. 10.1378/chest.117.4_suppl_2.198S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. 2006. A randomized trial of diagnostic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:2619–2630. 10.1056/NEJMoa052904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landis JR, Koch GG. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blot F, Raynard B, Chachaty E, Tancrède C, Antoun S, Nitenberg G. 2000. Value of Gram stain examination of lower respiratory tract secretions for early diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162:1731–1737. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9908088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg AE, Malhotra AK, Riaz OJ, Aboutanos MB, Duane TM, Borchers CT, Martin N, Ivatury RR. 2008. Predictive value of broncho-alveolar lavage fluid Gram's stain in the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a prospective study. J. Trauma 65:871–876, discussion 876–878. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818481e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook D, Mandell L. 2000. Endotracheal aspiration in the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 117:195S–197S. 10.1378/chest.117.4_suppl_2.195S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin YM, Oh YM, Kim MN, Shim TS, Lim CM, Lee SD, Koh Y, Kim WS, Kim DS, Hong SB. 2011. Usefulness of quantitative endotracheal aspirate cultures in intensive care unit patients with suspected pneumonia. J. Korean Med. Sci. 26:865–869. 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.7.865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solé Violán J, Fernández JA, Benítez AB, Cardeñosa Cendrero JA, Rodríguez de Castro F. 2000. Impact of quantitative invasive diagnostic techniques in the management and outcome of mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia. Crit. Care Med. 28:2737–2741. 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Duijn PJ, Dautzenberg MJ, Oostdijk EA. 2011. Recent trends in antibiotic resistance in European ICUs. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 17:658–665. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834c9d87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C, Du Z, Zhou Q, Hu B, Li Z, Yu L, Xu T, Fan X, Yang J, Li J. 2014. Microscopic examination of intracellular organisms in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a prospective multi-center study. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 127:1808–1813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirvent JM, Vidaur L, Gonzalez S, Castro P, de Batlle J, Castro A, Bonet A. 2003. Microscopic examination of intracellular organisms in protected bronchoalveolar mini-lavage fluid for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 123:518–523. 10.1378/chest.123.2.518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joos L, Chhajed PN, Wallner J, Battegay M, Steiger J, Gratwohl A, Tamm M. 2007. Pulmonary infections diagnosed by BAL: a 12-year experience in 1066 immunocompromised patients. Respir. Med. 101:93–97. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rello J, Afonso E, Lisboa T, Ricart M, Balsera B, Rovira A, Valles J, Diaz E, FADO Project Investigators 2012. A care bundle approach for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19:363–369. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Xie D, Li A, Yue J. 2013. Oral topical decontamination for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Hosp. Infect. 84:283–293. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grgurich PE, Hudcova J, Lei Y, Sarwar A, Craven DE. 2013. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: controversies and working toward a gold standard. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 26:140–150. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835ebbd0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pugin J, Auckenthaler R, Mili N, Janssens JP, Lew PD, Suter PM. 1991. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia by bacteriologic analysis of bronchoscopic and nonbronchoscopic “blind” bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 143:1121–1129. 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Croce MA, Fabian TC, Mueller EW, Maish GO, III, Cox JC, Bee TK, Boucher BA, Wood GC. 2004. The appropriate diagnostic threshold for ventilator-associated pneumonia using quantitative cultures. J. Trauma 56:931–934 discussion 934–936. 10.1097/01.TA.0000127769.29009.8C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambotte O, Timsit JF, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Misset B, Benali A, Carlet J. 2002. The significance of distal bronchial samples with commensals in ventilator-associated pneumonia: colonizer or pathogen? Chest 122:1389–1399. 10.1378/chest.122.4.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu CL, Yang DI, Wang NY, Kuo HT, Chen PZ. 2002. Quantitative culture of endotracheal aspirates in the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with treatment failure. Chest 122:662–668. 10.1378/chest.122.2.662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood AY, Davit AJ, II, Ciraulo DL, Arp NW, Richart CM, Maxwell RA, Barker DE. 2003. A prospective assessment of diagnostic efficacy of blind protective bronchial brushings compared to bronchoscope-assisted lavage, bronchoscope-directed brushings, and blind endotracheal aspirates in ventilator-associated pneumonia. J. Trauma 55:825–834. 10.1097/01.TA.0000090038.26655.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mentec H, May-Michelangeli L, Rabbat A, Varon E, Le Turdu F, Bleichner G. 2004. Blind and bronchoscopic sampling methods in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. A multicentre prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 30:1319–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mondi MM, Chang MC, Bowton DL, Kilgo PD, Meredith JW, Miller PR. 2005. Prospective comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage and quantitative deep tracheal aspirate in the diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia. J. Trauma 59:891–895; discussion 895–896. 10.1097/01.ta.0000188011.58790.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Pineda LA, Mankowski CR. 2007. Diagnostic yield of quantitative endotracheal aspirates in patients with severe nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Crit. Care 11:R57. 10.1186/cc5917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujitani S, Cohen-Melamed MH, Tuttle RP, Delgado E, Taira Y, Darby JM. 2009. Comparison of semi-quantitative endotracheal aspirates to quantitative non-bronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage in diagnosing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir. Care 54:1453–1461 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]