Abstract

The Versant HCV genotype 2.0 assay (line probe assay [LiPA] 2.0), based on reverse hybridization, and the Abbott Realtime HCV genotype II assay (Realtime II), based on genotype-specific real-time PCR, have been widely used to analyze hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes. However, their performances for detecting HCV genotype 6 infections have not been well studied. Here, we analyzed genotype 6 in 63 samples from the China HCV Genotyping Study that were originally identified as genotype 6 using the LiPA 2.0. The genotyping results were confirmed by nonstructural 5B (NS5B) or core sequence phylogenetic analysis. A total of 57 samples were confirmed to be genotype 6 (51 genotype 6a, 5 genotype 6n, and 1 genotype 6e). Four samples identified as a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 by the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed to be genotype 3b. The remaining two samples classified as genotype 6 by the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed to be genotype 1b, which were intergenotypic recombinants and excluded from further comparison. In 57 genotype 6 samples detected using the Realtime II version 2.00 assay, 47 genotype 6a samples were identified as genotype 6, one 6e sample was misclassified as genotype 1, and four 6a and five 6n samples yielded indeterminate results. Nine nucleotide profiles in the 5′ untranslated region affected the performances of both assays. Therefore, our analysis shows that both assays have limitations in identifying HCV genotype 6. The LiPA 2.0 cannot distinguish some 3b samples from genotype 6 samples. The Realtime II assay fails to identify some 6a and all non-6a subtypes, and it misclassifies genotype 6e as genotype 1.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infects 170 million people worldwide. The persistent infection is a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (1). Through phylogenetic analysis of the 9,400-nucleotide whole genome or the subgenomic regions, such as the core, E1, or nonstructural (NS) 5B regions, HCV has been classified into seven genotypes and 67 subtypes (2). The genotypes differ from one another by 30% at the nucleotide level, while the subtypes differ by 20% to 25%. HCV genotype is one of the strongest baseline predictors of the sustained virological response (SVR) to antiviral treatment with pegylated-interferon-α (PEG-IFN alpha) in combination with ribavirin (RBV) in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) (3). The genotype should be determined initially to tailor the dose of RBV and the duration of treatment, ensuring the best chances of achieving SVR while preventing overtreatment. With the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), antiviral efficacy has been proven to be subtype selective, and the resistance profile varies due to the heterogeneity of the target viral proteins, such as NS3/4A, in different genotypes (4). Furthermore, the distribution and prevalence of HCV genotypes can reflect patterns of viral transmission and human migration (5, 6). Therefore, HCV genotyping is both of clinical and epidemiological importance.

Genotypes 1, 2, and 3 are distributed worldwide. Genotype 6, however, is endemic in Southeast Asia and South China (7–9). Patients with genotype 6 account for 1.85% of all HCV infections in the United States, and all of these cases of genotype 6 occur in Asian-born patients (10). In our recent study, the China HCV Genotyping Study (CCgenos), we showed that there was a high prevalence of genotype 6 in South and Southwest China, accounting for 20.4% of all cases (11). Moreover, genotype 6 is also often seen in special populations, such as patients with thalassemia major and intravenous drug users (12, 13). Importantly, patients with genotype 6 respond better to PEG-IFN and RBV treatment than do patients with genotype 1, and it may be practical to shorten the treatment duration from 48 weeks to 24 weeks in order to help reduce the occurrence of adverse events and limit the disease burden (14). Recent studies have shown that patients with genotype 6 respond well to DAAs, such as simeprevir and sofosbuvir (15–17). Some DAAs, especially the polymerase inhibitors, seem to have pangenotypic antiviral activity. However, due to the limited number of patients with genotype 6 who have been enrolled in these clinical studies, further investigations are needed to clarify the safety, efficacy, and appropriate dosing of DAAs in this patient population. From another point of view, most patients with genotype 6 live in low-income countries and may not be able to afford the high cost of DAAs. Thus, the standard of care, i.e., PEG-IFN and RBV, remains the most common and cost-effective option (14). Therefore, the accurate identification of patients with genotype 6 is still important, even in the era of DAAs.

Many HCV genotyping assays have been developed and evaluated. Generally, the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) is the target for genotyping. Although this region is highly conserved, a well-characterized set of polymorphisms predicting the HCV genotype can be detected by restriction fragment length polymorphism (18), probe hybridization (19–22), genotype-specific real-time PCR (23, 24), or Sanger and next-generation sequencing (25–29). The determination of HCV genotype 6, however, seems more challenging due to the sequence diversity and similarity to that of genotype 1. For example, non-6a and non-6b subtypes were mistyped as 1b by an earlier version of the line probe assay (Inno-LiPA HCV 1.0), which is based on reverse hybridization with immobilized genotype-specific oligonucleotide probes (19, 20). Thereafter, a newer version, the Versant HCV genotype 2.0 (LiPA 2.0) assay, was developed, which incorporates core sequence information to improve the accuracy of distinguishing genotype 6 from other genotypes (20, 21). LiPA 2.0 classifies genotype 6 as “6a or 6b” or “6c to 6l (6c-l)” without providing the subtyping result. More recently, the Abbott Realtime HCV genotype II assay (Realtime II), based on genotype-specific real-time PCR, was launched. The Realtime II assay uses probes specific for the 5′ UTR and NS5B to indicate genotypes 1 to 6 and subtypes 1a and 1b, respectively. The assay is performed automatically on the Abbott m2000 platform, and the results are automatically determined by the application software. Thus, this method saves time and labor and is resistant to potential PCR aerosol contamination compared to other assays. In a recent study, the LiPA 2.0 and Realtime II assay were shown to yield consistent HCV genotyping results (23). Their abilities to identify genotype 6, however, have not been well studied due to the limited number of genotype 6 samples available.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the performances of both assays for identifying genotype 6, with clonal sequencing and phylogenetic analysis for NS5B or core sequences as the reference method. The nucleotide profiles influencing the performances of these systems were also analyzed to facilitate the technical improvement of HCV genotyping assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

In 2011, an epidemiology study was conducted of the HCV viral genotypes in treatment-naive Chinese CHC patients (the CCgenos study) (11). The study was performed with approval from the institutional review board of each participating center and the China National Human Genetic Resource Management Office. All patients provided informed consent. A total of 63 patients were identified as having genotype 6 or a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 using the LiPA 2.0. Among these patients, 57 harbored HCV genotype 6, according to the typical line patterns, while the samples from the other six patients exhibited patterns that were atypical for genotype 6 and were identified as genotype 6 in two patients and a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 in four patients. The serum samples were kept at −80°C until further analysis.

LiPA 2.0.

Viral RNA was purified using a QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and was subjected to reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with a Versant HCV amplification 2.0 kit (manufactured by Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium, for Siemens, Tarrytown, NY, USA). The 240-bp 5′ UTR and 270-bp core fragments were coamplified. Subsequently, amplicon denaturation, hybridization, washing, and color development of the genotyping strips were carried out on an Auto-LiPA system (Innogenetics) with a Versant HCV genotype 2.0 kit (Siemens). The results were interpreted according to the LiPA 2.0 interpretation chart, where the line patterns and the corresponding genotyping results are listed.

Realtime II assay.

All 63 samples were initially genotyped using the Realtime II version 1.00 assay. All genotyping procedures, including viral RNA extraction from 0.5 ml serum and RT-PCR, were completed automatically on the m2000 and m2000rt platforms with an Abbott Realtime HCV genotype II kit (Abbott, Des Plaines, IL, USA). The genotyping results were originally judged by the application software version 1.00. Shortly thereafter, Abbott updated the software to version 2.00. Therefore, the samples were regenotyped, and the results were compared to those from version 1.00.

Reference HCV genotyping.

All 63 samples were subjected to clonal sequencing of the NS5B sequence (222 bp, positions 8316 to 8537) as the reference method (25). If the NS5B sequence was not available, the core sequence (355 bp, positions 350 to 704) was alternatively analyzed (26). RT-PCR and nested-PCR were performed to amplify the target sequence. A 6-μl aliquot of RNA was added to the avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase reaction system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), with a final volume of 10 μl containing 1× AMV reaction buffer, 1 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 3 μM primer NS5-2 for NS5B and 410 for the core sequence,(Table 1), and 6 units of AMV reverse transcriptase. RT-PCR was initiated at 42°C for 60 min. The RT system was then supplemented with 40 μl of the first-round PCR solution to a final volume of 50 μl containing 2.5 units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM Mg2+, 200 μM each dNTP, and 0.6 μM outer sense and antisense primers (Table 1). For the second-round PCR, 3 μl of the first-round PCR product was added to the reaction system to a final volume of 50 μl, containing the same components as that of first-round PCR, except that 0.6 μM inner sense and antisense primers were added (Table 1). Both first- and second-round PCR assays were carried out with the following steps: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 48°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, elongation at 72°C for 10 min, and cooling at 4°C. The PCR amplicon was purified and ligated into the pMD18-T cloning vector (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). For each sample, ≥25 clones were successfully sequenced. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA 4.0.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR based on 5′ UTR and NS5B sequences

| Primer | Region | Positionsa | Polarity | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 939 | 5′ UTR | 45–64 | Sense | CTGTGAGGAACTACTGTCTT | Okamoto et al. (39) |

| 209 | 5′ UTR | 321–349 | Antisense | ATACTCGAGGTGCACGGTCTACGAGACCT | Garson et al. (40) |

| SF-2 | NS5B | 8240–8260 | Sense | CCCTATGGGCTTCTCATATGA | Du et al. (36) |

| NS5-1 | NS5B | 8256–8278 | Sense | TATGACACCCGCTGTTTTGACTC | Du et al. (36) |

| NS5-4 | NS5B | 8616–8636 | Antisense | CCTGGTCATAGCCTCCGTGAA | Du et al. (36) |

| NS5-2 | NS5B | 8677–8695 | Antisense | GATGTTATCAGCTCCAGGT | Du et al. (36) |

| 954 | Core | 288–311 | Sense | ACTGCCTGATAGGGTGCTTGCGAG | Mellor J et al. (41) |

| 406 | Core | 321–349 | Sense | AGGTCTCGTAGACCGTGCATCATGAGCAC | Chan et al. (42) |

| 951 | Core | 705–724 | Antisense | CAYGTRAGGGTATCGATGAC | Mellor J et al. (41) |

| 410 | Core | 732–751 | Antisense | ATGTACCCCATGAGGTCGGC | Chan et al. (42) |

5′ UTR sequence alignment.

An aliquot of 5 μl of extracted RNA was added to the one-step RT-PCR system (Qiagen), with a final volume of 25 μl, containing 1× OneStep RT-PCR buffer, 400 μM each dNTP, 0.6 μM primers 939 and 209 (Table 1), and 1 μl OneStep RT-PCR enzyme mix. RT-PCR was carried out according to the following protocol: 50°C for 30 min (RT), 95°C for 15 min (initial PCR activation), followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, 72°C for 10 min, and cooling to 4°C. The amplicon was purified and sequenced. The 5′ UTR sequences were aligned using BioEdit 7.0 (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Reference sequences.

The reference sequences for the 5′ UTR alignment and phylogenetic analysis were extracted from the GenBank database according to the latest updated HCV genotype list (2), with GenBank accession no. (genotype) AF009606 (1a), D90208 (1b), D00944 (2a), D17763 (3a), D49374 (3b), Y11604 (4a), Y13184 (5a), Y12083 (6a), D84262 (6b), EF424629 (6c), D84263 (6d), DQ314805 (6e), DQ835760 (6f), D63822 (6g), D84265 (6h), DQ835770 (6i), DQ835769 (6j), D84264 (6k), EF424628 (6l), DQ835767 (6m), DQ278894 (6n), EF424627 (6o), EF424626 (6p), EF424625 (6q), EU408328 (6r), EU408329 (6s), EF632071 (6t), EU246940 (6u), EU158186 (6v), DQ278892 (6w), EU408330 (6xa), and EF108306 (7a).

Amplification and quality control.

The quality control included two main measures: control of the PCR assay and control of the inconsistent genotyping results by different assays. Reagent preparation, RNA extraction, amplification, electrophoresis, DNA sequencing, and reverse hybridization were performed in a PCR laboratory approved by the China National Center for Clinical Laboratories to prevent potential carryover contamination. For each PCR run, a negative control and a blank control were included. The negative control, an anti-HCV-negative serum, or a commercial negative control was included throughout the RT-PCR assay and for the nested-PCR procedure from RNA extraction. A double-distilled water (ddH2O) blank control was included at the start of RT-PCR. If the negative or blank control was read as being positive, the run was cancelled. Analysis of the discordant genotyping samples was repeated, starting from the RNA extraction step, and the results were compared between the two experiments.

RESULTS

Confirmation of the CCgenos genotyping results by NS5B or core clonal sequencing.

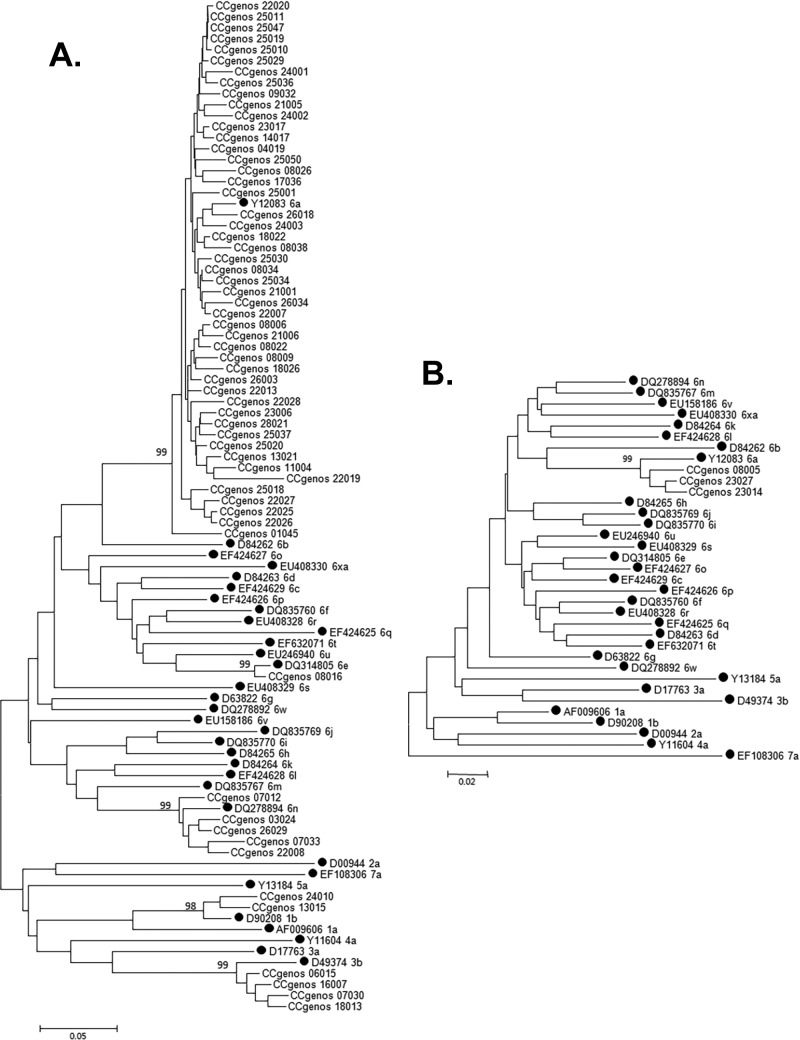

In the 63 samples originally determined to be single genotype 6 (genotype 6 only) or a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 by the LiPA 2.0, all were confirmed to be a single genotype infection, and no samples were found to have mixed genotype infections. The genotypes of 60 samples were confirmed using the NS5B sequence analysis, whereas the genotypes of the remaining three samples were confirmed using the core sequence (Fig. 1). In total, 57 samples were confirmed to be genotype 6. Four samples with a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 by the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed to have a single genotype infection (3b). Two samples originally classified as genotype 6 by the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed to be from genotype 1b. These samples were found to be recombinant viral strains with the 5′ UTR sequence of genotype 6 and the NS5B sequence of genotype 1b and were therefore excluded from further comparisons. Genotype 6 was distributed mainly in South China (50/57 [87.7%]). The subtype 6a samples were predominant in all genotype 6 cases (51/57 [89.5%]), followed by subtype 6n (5/57 [8.8%]) and 6e samples (1/57 [1.8%]).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic trees of the 222-bp NS5B sequences of 60 CCgenos HCV variants (A) and 355-bp core sequences of 3 variants (B). The bootstrap percentages are shown at the node of each main branch. The bar at the lower left indicates the genetic divergence. The reference sequences are labeled with black circles.

Overall comparison of genotyping results determined using both commercial assays and reference method.

All 57 samples identified as genotype 6 using the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed by the reference method. The remaining four samples identified as a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 by the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed to be genotype 3b. On the other hand, only 28 out of 57 samples were classified as genotype 6 using the Realtime II version 1.00 assay, 19 genotype 6a samples were misclassified as a mixture of genotype 6 and 1, four genotype 6a and five genotype 6n samples yielded indeterminate results, and one genotype 6e sample was misclassified as genotype 1. After the software update from version 1.00 to 2.00, all but 19 genotyping results were unchanged. These 19 samples originally mistyped as a mixture of genotypes 6 and 1 were correctly identified as genotype 6 using the application software version 2.00. The accuracy of the Realtime II version 2.00 assay for detecting genotype 6 was 82.5% (47/57) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Overall comparison of the genotyping results for the two commercial assays and the reference method (n = 63)

| Genotype by NS5B or core clonal sequencing (n) | Genotype by Versant HCV genotype 2.0 (n) |

Genotype by Abbott Realtime HCV genotype II (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6a or 6b (53) | 6c-l (6)a | 6c-l/4 mixture (4) | ||

| 6a (51) | 28 | 6 (28) | ||

| 19 | 6 (19)b | |||

| 4 | Indeterminate (4)c | |||

| 6e (1) | 1 | 1 (1) | ||

| 6n (5) | 5 | Indeterminate (5)c | ||

| 1b (2) | 2 | 6 (2) | ||

| 3b (4) | 3 | 3 (3) | ||

| 1 | Indeterminate (1)c | |||

6c-l, any one of the subtypes from 6c to 6l.

Classified as genotype 1/6 mixture by Realtime II version 1.00, while determined to be genotype 6 by Realtime II version 2.00.

Realtime II yielded indeterminate genotyping results when the genotype-specific probes failed to react with the HCV sequences and therefore, the definite genotype could not be predicted.

Alignment of the 5′ UTR sequences with atypical LiPA 2.0 assay line patterns.

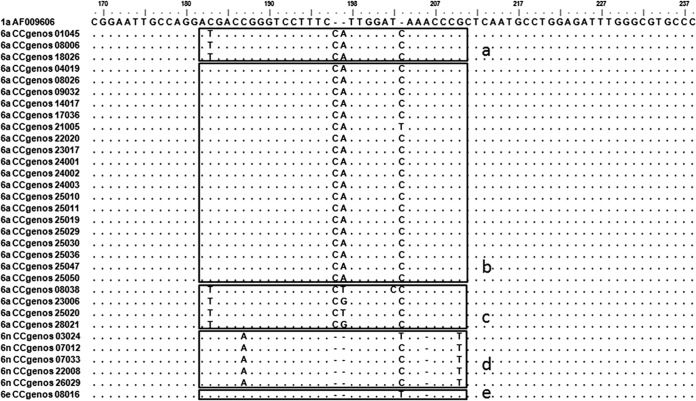

Four samples with the reactivity pattern of lines 1, 2, 7, 17, 18, 23, and 24 were originally classified as a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 by the LiPA 2.0 due to the coexistence of patterns specific to both genotypes 6 and 4 (lines 7, 23, and 24 for genotype 6, and lines 17 and 18 for genotype 4). However, these samples were from genotype 3b, whose 5′ UTR sequences shared some similar nucleotide profiles with those of genotypes 3b and 4 (Fig. 2, sequences in boxes 17 and 18) but displayed double-nucleotide polymorphisms (A243G and T248C, respectively), which caused their reactivity with line 7 (Fig. 2, sequences in box 7). Moreover, two samples displayed a line pattern of 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 23, and 24, with the absence of line 21. Both displayed a T203C mutation in the 5′ UTR, while one had a CT insertion after position 197 and the other had a T insertion after position 203 (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Alignment of the 5′ UTR sequences from samples with atypical LiPA 2.0 line patterns. The regions that reacted with the LiPA probes on lines 7, 17, 18, and 21 (30) are boxed and labeled at the bottom right outer corner of the box. Nucleotides that are identical to those of the consensus sequence are indicated by dots; gaps introduced in the sequences to preserve alignment are indicated by horizontal lines. At the left are the subtypes and CCgenos sample identifications (IDs) or accession numbers of the standard sequences.

Alignment of the 5′ UTR sequences of samples with inconsistent or indeterminate results by Realtime II assay.

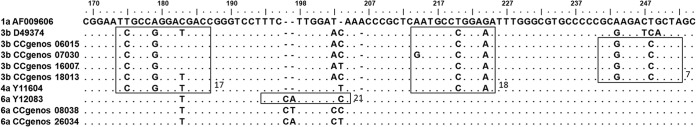

Nineteen genotype 6a samples were misclassified as a mixture of genotypes 1 and 6 by the Realtime II version 1.00 assay. Compared with the samples correctly determined as single genotype 6, these misclassified samples all lacked the C183T mutation (Fig. 3, box a). Nine samples were not identified by the Realtime II assay (four genotype 6a samples and five genotype 6n samples). Four genotype 6a sequences displayed an atypical insertion of CT or CG rather than CA after position 197 (Fig. 3, box c). Five genotype 6n samples also were not determined by the Realtime II assay; the sequences of these samples included a deletion of A at position 206 and two mutations, C187A and G210T(Fig. 3, box d). Another genotype 6e sample misclassified as genotype 1 had a similar sequence profile to that of genotype 1, except for an insertion of T after position 203 and a deletion of A at position 206 (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Alignment of the 5′ UTR sequences from the samples with inconsistent or indeterminate results using Realtime II version 1.00 and version 2.00 assays. The possible probe hybridization regions of the Realtime II assay are boxed. Box a, Three representative genotype 6a sequences correctly determined to be genotype 6 using the Realtime II; box b, 19 sequences misclassified as a mixture of genotypes 6 and 1 using the Realtime II version 1.00 assay but correctly determined using version 2.00 assay; box c, 4 genotype 6a sequences with indeterminate results using the Realtime II assay; box d, 5 genotype 6n sequences with indeterminate results using the Realtime II assay; box e, 1 genotype 6e sequence misclassified as genotype 1 using the Realtime II assay.

Nucleotide profiles of 5′ UTR that influenced the determination of genotype 6 by the LiPA 2.0 and Realtime II systems.

Both commercial assays heavily rely on the sequence of the 5′ UTR region. In total, there were nine 5′ UTR sequence profiles that can influence the detection of genotype 6 using these assays, all of which were located in the 5′ UTR sequence from positions 183 to 210 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

The 5′ UTR nucleotide profiles that influenced the determination of genotype 6 using Versant HCV Genotype 2.0 assay and Abbott Realtime HCV Genotype II assay

| No. | Sequence profiles from position 183 to position 210a |

Influence on genotype 6 identification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 183 | 187 | 197 | 203 | 205 | 210 | ||

| 1 | C183T | —b | C197a, T197b | T203C, C203a | — | — | Atypical line patterns by LiPA 2.0 and indeterminate by Realtime IIc |

| 2 | C183T | — | C197a, A197b | T203C, T203a | — | — | Atypical line patterns by LiPA 2.0 |

| 3 | — | — | C197a, A197b | C203a | — | — | Mistyped as genotype 1/6 by Realtime II version 1.00d |

| 4 | — | — | C197a, A197b | T203a | Mistyped as genotype 1/6 by Realtime II version 1.00d | ||

| 5 | C183T | — | C197a, G197b | C203a | — | — | Indeterminate by Realtime IIc |

| 6 | C183T | — | C197a, T197b | C203a | — | — | Indeterminate by Realtime IIc |

| 7 | — | C187A | — | T203a | 205–207 (del 206) | G210T | Indeterminate by Realtime IIc |

| 8 | — | C187A | — | C203a | 205–207 (del 206) | G210T | Indeterminate by Realtime IIc |

| 9 | — | — | — | T203a | 205–207 (del 206) | — | Mistyped as genotype 1 by Realtime II |

Numbering according to the HCV strain H77, with the GenBank accession no. AF009606; numbering and description for the mutations, insertions, or deletions relative to the H77 sequence are according to Kuiken et al. (43).

—, no polymorphism.

Realtime II yielded indeterminate genotyping results when the genotype-specific probes failed to react with the HCV sequences and therefore, the definite genotype could not be predicted.

Mistyping was corrected by updating the application software from version 1.00 to version 2.00.

DISCUSSION

Compared with the in-house assays, the major advantage of commercial HCV genotyping assays is the thorough assay standardization required for commercialization and the high success rate of genotyping. Both commercial assays, the LiPA 2.0 and the Realtime II, have been widely used and reported to yield consistent results (23). However, few samples identified as genotype 6 were included in these previous studies. Moreover, even among other Asian countries neighboring China, the distribution and subtypical composition of genotype 6 differ. For example, genotypes 6a (24%) and 6e (22%) are the two predominant subtypes among all the genotypes in Vietnam (9); in Myanmar, however, genotype 6n is the most predominant subtype, accounting for 39% of all genotypes, and 6m is also prevalent (9%) (8). In Thai patients with genotype 6, subtype 6f is the most common subtype (56%), followed by subtypes 6n (22%), 6i (11%), 6j (10%), and 6e (1%) (7). Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the performances of both methods for detecting genotype 6 samples from Chinese CHC patients with potentially distinctive sequence diversity.

All 57 samples identified as genotype 6 by the LiPA 2.0 were confirmed by the reference method. However, four samples were misclassified as a mixture of genotypes 6 and 4 using the LiPA 2.0; this genotype displayed a line pattern that is not listed on the interpretation chart and might alternatively be classified as indeterminate. The 5′ UTR sequences of these genotypes had similar nucleotide profiles to those of genotype 4, reacting with probes on lines 17 and 18 but displaying the same profile as those of some rare genotype 6 sequences, also reacting with the probe on lines 7, 23, and 24 (30). In actuality, these sequences represented the single 3b subtype, accounting for approximately 5% of the genotype 3 sequences in the Chinese population (11), and these have not yet been fully described. We suggest that this unique line pattern should be added to the chart to better distinguish genotype 3b from genotypes 4 and 6. Furthermore, we compared the LiPA 2.0 results with the reference method at the subtype level. Six genotype 6n samples were misclassified as genotypes 6c-l. Since January 2014, subtypes from 6m to 6xa have been assigned. Therefore, we suggest that genotype 6c-l be replaced by “non-6a or non-6b subtype” to avoid subtype misclassification. Additionally, two samples displayed an atypical line pattern of 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 23, and 24, lacking the line 21 due to polymorphisms (position 198 or 203); however, both of these samples were confirmed as genotype 6a. This atypical line pattern should also be noted in the interpretation chart in the LiPA 2.0 kit. In summary, our data suggest that the LiPA 2.0 is sufficient for the detection of genotype 6 samples in China. Recently, a research group from China also reported that 11 out of 21 genotype 6a samples were misclassified as genotype 1b by the LiPA 2.0 (29). These results are intriguing, because the line patterns of the LiPA 2.0 for genotype 6a or 6b are quite different from those for genotype 1b and, therefore, they are unlikely to be mistyped. Unfortunately, the sequences from the 11 samples with mistyped results were not available.

Compared with other commercial or in-house genotyping methods, the automated Realtime II assay requires less labor and time and is free from potential aerosol contamination. However, despite these advantages, the performance for detecting genotype 6 was not satisfactory. One-third of the single genotype 6 samples were originally misclassified as a mixture of genotypes 1 and 6 using the application software version 1.00; some samples with single genotype 3 or 4 infection were also reported in previous studies (23, 31) to be misclassified as mixtures of genotypes 1 and 3 or 1 and 4. Recently, Abbott declared that a cross-reaction occurred if there was a perfect match between the HCV genotype probe and a 5′ UTR sequence belonging to a different genotype, which might be overcome by improving the application software to a higher version (version 2.00) without altering the genotyping reagents and procedures. After the update of the readout software, 19 samples previously identified as a mixture of genotypes 1 and 6 were correctly genotyped as single genotype 6 samples. This difference is important, because patients with genotype 6 are expected to achieve high SVR even with a shorter course of treatment (24 weeks) with PEG-IFN and RBV, particularly for those who had undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 (14). If a patient is misdiagnosed as having a genotype 1 and 6 coinfection, physicians will have to treat the patient as though he or she has an infection with genotype 1. Therefore, the patient can benefit from shorter treatment duration only if an accurate diagnosis of single genotype 6 infection is made. Unfortunately, the Realtime II assay failed to detect genotype 6a samples with atypical 5′ UTR nucleotide profiles. Generally, both 6a and 6b subtypes can be distinguished from genotype 1 more easily than non-6a or non-6b samples due to the dual nucleotide insertion CA between positions 197 and 198 in the 5′ UTR region (18). However, four out of 48 genotype 6a samples in our study displayed an atypical insertion of CT or CG, rather than CA; similar results were also reported in Canadian patients by Murphy et al. (27). The subtype 6a samples with such atypical profiles account for approximately 7.0% (4/57) of the genotype 6 samples in China. Furthermore, the Realtime II assay did not yield accurate results for the identification of non-6a or non-6b subtypes. All five of the genotype 6n samples, which had a deletion of A at position 206 and two polymorphisms (A at position 187 and T at position 210), yielded indeterminate results. Another genotype 6e sample was misclassified as genotype 1. Through an analysis of the confirmed HCV subtype 6 sequences (2), it can be extrapolated that many non-6a or non-6b subtypes, such as 6d, 6g, 6i, 6j, 6l, 6o, 6p, 6q, 6s, 6t, 6u, 6v, and 6xa, are very likely to be genotyped as genotype 1 because of the high 5′ UTR sequence similarity (data not shown). As a result, the Realtime II assay is not applicable in Southeast Asian countries, where the non-6a or non-6b subtypes are dominant, unless appropriate modifications are made (7–9). Additionally, one out of four genotype 3b samples also yielded indeterminate results, indicating that the indeterminate results occurred not only for genotype 6 but also for other genotypes (32). Most of the commercial genotyping assays, including the Realtime II, are focused on the 5′ UTR fragment, which is highly conserved and can be amplified easily. Simple analysis of the 5′ UTR is sufficient to identify genotype 1 to 5 because a well-characterized set of polymorphisms in this region can predict genotypes well (27, 33, 34). Our results, however, proved that the genotype 6 samples could not be genotyped accurately using only the 5′ UTR sequence due to the nucleotide polymorphisms in the 6a or 6b sequences and the sequence similarity between the non-6a and non-6b subtypes and genotype 1. Therefore, from a technical point of view, even a careful redesign of the genotype-specific probes for the Realtime II assay would likely be insufficient for accurate identification of genotype 6. Alternatively, combination with another region, such as the core, may be warranted for the newer version. Notably, the Abbott Realtime II system is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States for the analysis of genotype 6, where the prevalence of genotype 6 is very low (10). Although the reliability of detecting genotype 6 is passably acceptable in Chinese patients, with an accuracy of >80%, the Realtime II assay is not advised to be used with residents of Southeast Asia or emigrants from these regions.

Advances in sequencing technology (including traditional Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing, and next-generation sequencing) have accelerated the genotyping of HCV. The NS5B sequence is far less conservative than the 5′ UTR and is therefore more reliable for distinguishing among the HCV subtypes and for tracing the source of HCV infection (25, 27, 33). The amplification of the NS5B sequence is more challenging than that of the 5′ UTR, particularly for genotype 6, with a failure rate of approximately 20% or even higher (27, 29, 34, 35). Interestingly, the amplification of NS5B was more efficient in our study, with a PCR-positive rate of 95%. Moreover, the amplification of NS5B is also effective in other genotypes (36). However, there was still 5% PCR failure in the genotype 6 samples. This is probably due to the diversity of the NS5B sequence rather than the low viral load, as relatively high viral loads have been observed in samples that fail NS5B amplification (3.61 to 6.63 log10 IU/ml HCV RNA). Therefore, in such cases, the 5′ UTR or core sequencing is an alternative. The shortcoming of direct sequencing is its low efficiency for detecting mixed-genotype infections. However, in reality, very few samples have a mixed-genotype infection (11). With the development of sequencing technology, direct Sanger sequencing assay becomes more affordable than commercial genotyping assays, but the RT-PCR, sequencing, and result readouts must be performed by experienced staff to ensure quality.

Special attention should be paid to two samples that were identified as genotype 6 by both commercial methods but as genotype 1b by the reference method. Similar results were reported in our previous study (44). Five samples from Thailand with the genotype 6 core sequence and genotype 1 or 3 NS5B sequence were discovered by Chinchai et al. (37). Additionally, a recombinant strain with a genotype 2 core sequence and a genotype 6 NS5B sequence were found in Vietnam (38). Therefore, recombination between genotype 6 and other genotypes is not rare. More recombination may occur if two or more genotyping assays focusing on different subgenomic regions are carried out. The importance of recombination between genotype 6 and other genotypes remains unknown. The genotypes of these recombinant strains should be assigned according to the most recently updated criteria (2).

In conclusion, both commercial methods have limitations for detecting HCV genotype 6. The LiPA 2.0 cannot distinguish some genotype 3b samples from genotype 6 samples, and genotyping results with special line patterns should be considered to improve the sensitivity and specificity of this method. The Realtime II assay fails to determine or misclassifies some genotype 6 subtypes. Therefore, modification of the genotype-specific probe(s) is advised. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the intergenotypic recombination between genotype 6 and other genotypes are potential challenges to laboratory diagnosis and antiviral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the China National Science and Technology Major Project for Infectious Diseases Control during the 12th Five-Year Plan Period (2012ZX10002003 and 2012ZX10002005), the Major Project of National Science and Technology “Creation of major new drugs” (2012ZX09303019), Peking University People's Hospital Research and Development Funds (RDC2012-06), and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

We thank Zhiliang Gao, Qing Mao, and Minghua Su, as well as the other investigators in the CCgenos study, for providing the HCV genotype 6 samples. The Abbott Realtime HCV genotype II assay kits were kindly provided by Abbott Molecular.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Wei L, Lok AS. 2014. Impact of new hepatitis C treatments in different regions of the world. Gastroenterology 146:1145–1150. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, Muerhoff AS, Rice CM, Stapleton JT, Simmonds P. 2014. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology 59:318–327. 10.1002/hep.26744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver. 2011. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 55:245–264. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soriano V, Vispo E, Poveda E, Labarga P, Martin-Carbonero L, Fernandez-Montero JV, Barreiro P. 2011. Directly acting antivirals against hepatitis C virus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1673–1686. 10.1093/jac/dkr215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pybus OG, Charleston MA, Gupta S, Rambaut A, Holmes EC, Harvey PH. 2001. The epidemic behavior of the hepatitis C virus. Science 292:2323–2325. 10.1126/science.1058321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu L, Wang M, Xia W, Tian L, Xu R, Li C, Wang J, Rong X, Xiong H, Huang K, Huang J, Nakano T, Bennett P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Fu Y. 2014. Migration patterns of hepatitis C virus in China characterized for five major subtypes based on samples from 411 volunteer blood donors from 17 provinces and municipalities. J. Virol. 88:7120–7129. 10.1128/JVI.00414-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akkarathamrongsin S, Praianantathavorn K, Hacharoen N, Theamboonlers A, Tangkijvanich P, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Poovorawan Y. 2010. Geographic distribution of hepatitis C virus genotype 6 subtypes in Thailand. J. Med. Virol. 82:257–262. 10.1002/jmv.21680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lwin AA, Shinji T, Khin M, Win N, Obika M, Okada S, Koide N. 2007. Hepatitis C virus genotype distribution in Myanmar: predominance of genotype 6 and existence of new genotype 6 subtype. Hepatol. Res. 37:337–345. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00053.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham VH, Nguyen HD, Ho PT, Banh DV, Pham HL, Pham PH, Lu L, Abe K. 2011. Very high prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotype 6 variants in southern Vietnam: large-scale survey based on sequence determination. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 64:537–539 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nainan OV, Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Gao FX, Xia G, McQuillan G, Margolis HS. 2006. Hepatitis C virus genotypes and viral concentrations in participants of a general population survey in the United States. Gastroenterology 131:478–484. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao H, Wei L, Lopez-Talavera JC, Shang J, Chen H, Li J, Xie Q, Gao Z, Wang L, Wei J, Jiang J, Sun Y, Yang R, Li H, Zhang H, Gong Z, Zhang L, Zhao L, Dou X, Niu J, You H, Chen Z, Ning Q, Gong G, Wu S, Ji W, Mao Q, Tang H, Li S, Wei S, Sun J, Jiang J, Lu L, Jia J, Zhuang H. 2014. Distribution and clinical correlates of viral and host genotypes in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 29:545–553. 10.1111/jgh.12398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong DA, Tong LK, Lim W. 1998. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotype 6 among certain risk groups in Hong Kong. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 14:421–426. 10.1023/A:1007400304726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou DX, Tang JW, Chu IM, Cheung JL, Tang NL, Tam JS, Chan PK. 2006. Hepatitis C virus genotype distribution among intravenous drug user and the general population in Hong Kong. J. Med. Virol. 78:574–581. 10.1002/jmv.20578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thu Thuy PT, Bunchorntavakul C, Tan Dat H, Rajender Reddy K. 2012. A randomized trial of 48 versus 24 weeks of combination pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy in genotype 6 chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 56:1012–1018. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno C, Berg T, Tanwandee T, Thongsawat S, Van Vlierberghe H, Zeuzem S, Lenz O, Peeters M, Sekar V, De Smedt G. 2012. Antiviral activity of TMC435 monotherapy in patients infected with HCV genotypes 2–6: TMC435-C202, a phase IIa, open-label study. J. Hepatol. 56:1247–1253. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, Schultz M, Davis MN, Kayali Z, Reddy KR, Jacobson IM, Kowdley KV, Nyberg L, Subramanian GM, Hyland RH, Arterburn S, Jiang D, McNally J, Brainard D, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Sheikh AM, Younossi Z, Gane EJ. 2013. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:1878–1887. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenz O, Vijgen L, Berke JM, Cummings MD, Fevery B, Peeters M, De Smedt G, Moreno C, Picchio G. 2013. Virologic response and characterization of HCV genotype 2–6 in patients receiving TMC435 monotherapy (study TMC435-C202). J. Hepatol. 58:445–451. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith DB, Mellor J, Jarvis LM, Davidson F, Kolberg J, Urdea M, Yap PL, Simmonds P. 1995. Variation of the hepatitis C virus 5′ non-coding region: implications for secondary structure, virus detection and typing. The International HCV Collaborative Study Group. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Pt 7):1749–1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinchai T, Labout J, Noppornpanth S, Theamboonlers A, Haagmans BL, Osterhaus AD, Poovorawan Y. 2003. Comparative study of different methods to genotype hepatitis C virus type 6 variants. J. Virol. Methods 109:195–201. 10.1016/S0166-0934(03)00071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noppornpanth S, Sablon E, De Nys K, Lien TX, Brouwer J, Van Brussel M, Smits SL, Poovorawan Y, Osterhaus ADME, Haagmans BL. 2006. Genotyping hepatitis C viruses from Southeast Asia by a novel line probe assay that simultaneously detects core and 5′ untranslated regions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3969–3974. 10.1128/JCM.01122-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verbeeck J, Stanley MJ, Shieh J, Celis L, Huyck E, Wollants E, Morimoto J, Farrior A, Sablon E, Jankowski-Hennig M, Schaper C, Johnson P, Van Ranst M, Van Brussel M. 2008. Evaluation of Versant hepatitis C virus genotype assay (LiPA) 2.0. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1901–1906. 10.1128/JCM.02390-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larrat S, Poveda JD, Coudret C, Fusillier K, Magnat N, Signori-Schmuck A, Thibault V, Morand P. 2013. Sequencing assays for failed genotyping with the Versant hepatitis C virus genotype assay (LiPA), version 2.0. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:2815–2821. 10.1128/JCM.00586-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciotti M, Marcuccilli F, Guenci T, Babakir-Mina M, Chiodo F, Favarato M, Perno CF. 2010. A multicenter evaluation of the Abbott RealTime HCV Genotype II assay. J. Virol. Methods 167:205–207. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn YH, Ko SY, Kim MH, Oh HB. 2010. Performance evaluation of the Abbott RealTime HCV Genotype II for hepatitis C virus genotyping. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 48:469–474. 10.1515/CCLM.2010.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmonds P, Holmes EC, Cha TA, Chan SW, McOmish F, Irvine B, Beall E, Yap PL, Kolberg J, Urdea MS. 1993. Classification of hepatitis C virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS-5 region. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Pt 11):2391–2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmonds P, Smith DB, McOmish F, Yap PL, Kolberg J, Urdea MS, Holmes EC. 1994. Identification of genotypes of hepatitis C virus by sequence comparisons in the core, E1 and NS-5 regions. J. Gen. Virol. 75(Pt 5):1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy DG, Willems B, Deschênes M, Hilzenrat N, Mousseau R, Sabbah S. 2007. Use of sequence analysis of the NS5B region for routine genotyping of hepatitis C virus with reference to C/E1 and 5′ untranslated region sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1102–1112. 10.1128/JCM.02366-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avó AP, Agua-Doce I, Andrade A, Pádua E. 2013. Hepatitis C virus subtyping based on sequencing of the C/E1 and NS5B genomic regions in comparison to a commercially available line probe assay. J. Med. Virol. 85:815–822. 10.1002/jmv.23545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai Q, Zhao Z, Liu Y, Shao X, Gao Z. 2013. Comparison of three different HCV genotyping methods: core, NS5B sequence analysis and line probe assay. Int. J. Mol. Med. 31:347–352. 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stuyver L, Wyseur A, van Arnhem W, Hernandez F, Maertens G. 1996. Second-generation line probe assay for hepatitis C virus genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2259–2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaghefi P, Marchadier E, Dussaix E, Roque-Afonso AM. 2010. Hepatitis C virus genotyping: comparison of the Abbott RealTime HCV Genotype II assay and NS5B sequencing. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 58:175–178 (In French.) 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González V, Gomes-Fernandes M, Bascuñana E, Casanovas S, Saludes V, Jordana-Lluch E, Matas L, Ausina V, Martró E. 2013. Accuracy of a commercially available assay for HCV genotyping and subtyping in the clinical practice. J. Clin. Virol. 58:249–253. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandres-Sauné K, Deny P, Pasquier C, Thibaut V, Duverlie G, Izopet J. 2003. Determining hepatitis C genotype by analyzing the sequence of the NS5b region. J. Virol. Methods 109:187–193. 10.1016/S0166-0934(03)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laperche S, Lunel F, Izopet J, Alain S, Dény P, Duverlie G, Gaudy C, Pawlotsky JM, Plantier JC, Pozzetto B, Thibault V, Tosetti F, Lefrère JJ. 2005. Comparison of hepatitis C virus NS5b and 5′ noncoding gene sequencing methods in a multicenter study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:733–739. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.733-739.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Germer JJ, Rys PN, Thorvilson JN, Persing DH. 1999. Determination of hepatitis C virus genotype by direct sequence analysis of products generated with the Amplicor HCV test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2625–2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du SC, Wei L, Tao QM, Feng BF, Zhu L, Liu JX. 1996. Nested PCR for the detection of HCV RNA nonstructural gene. Chin. J. Med. Lab. Sci. 19:354–357 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chinchai T, Noppornpanth S, Bedi K, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. 2006. 222 base pairs in NS5B region and the determination of hepatitis C virus genotype 6. Intervirology 9:224–229. 10.1159/000091469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noppornpanth S, Lien TX, Poovorawan Y, Smits SL, Osterhaus AD, Haagmans BL. 2006. Identification of a naturally occurring recombinant genotype 2/6 hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 80:7569–7577. 10.1128/JVI.00312-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okamoto H, Okada S, Sugiyama Y, Tanaka T, Sugai Y, Akahane Y, Machida A, Mishiro S, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y. 1990. Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA by a two-stage polymerase chain reaction with two pairs of primers deduced from the 5′-noncoding region. Jpn. J. Exp. Med. 60:215–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garson JA, Ring C, Tuke P, Tedder RS. 1990. Enhanced detection by PCR of hepatitis C virus RNA. Lancet 336:878–879. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92384-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellor J, Holmes EC, Jarvis LM, Yap PL, Simmonds P. 1995. Investigation of the pattern of hepatitis C virus sequence diversity in different geographical regions: implications for virus classification. The International HCV Collaborative Study Group. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Pt 10):2493–2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan SW, McOmish F, Holmes EC, Dow B, Peutherer JF, Follett E, Yap PL, Simmonds P. 1992. Analysis of a new hepatitis C virus type and its phylogenetic relationship to existing variants. J. Gen. Virol. 73:1131–1141. 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuiken C, Combet C, Bukh J, Shin IT, Deleage G, Mizokami M, Richardson R, Sablon E, Yusim K, Pawlotsky JM, Simmonds P, Los Alamos HIV Database Group 2006. A comprehensive system for consistent numbering of HCV sequences, proteins and epitopes. Hepatology 44:1355–1361. 10.1002/hep.21377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang R, Li JQ, Liu LJ, Du SC, Wei L. 2006. Analysis and state of HCV genotype 6a infection. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 38:614–617 (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]