Abstract

Previously, we identified a spontaneous, essentially avirulent mutant, FSC043, of the highly virulent strain SCHU S4 of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis. We have now characterized the phenotype of the mutant and the mechanisms of its attenuation in more detail. Genetic and proteomic analyses revealed that the pdpE gene and most of the pdpC gene were very markedly downregulated and, as previously demonstrated, that the strain expressed partially deleted and fused fupA and fupB genes. FSC043 showed minimal intracellular replication and induced no cell cytotoxicity. The mutant showed delayed phagosomal escape; at 18 h, colocalization with LAMP-1 was 80%, indicating phagosomal localization, whereas the corresponding percentages for SCHU S4 and the ΔfupA mutant were <10%. However, a small subset of the FSC043-infected cells contained up to 100 bacteria with LAMP-1 colocalization of around 30%. The unusual intracellular phenotype was similar to that of the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants. Complementation of FSC043 with the intact fupA and fupB genes did not affect the phenotype, whereas complementation with the pdpC and pdpE genes restored intracellular replication and led to marked virulence. Even higher virulence was observed after complementation with both double-gene constructs. After immunization with the FSC043 strain, moderate protection against respiratory challenge with the SCHU S4 strain was observed. In summary, FSC043 showed a highly unusual intracellular phenotype, and based on our findings, we hypothesize that the mutation in the pdpC gene makes an essential contribution to the phenotype.

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis is the etiological agent of tularemia, a disease widespread in mammals. Apart from infecting rodents, hares, and rabbits, F. tularensis is capable of causing disease in humans. The spread to humans occurs mainly via ticks or mosquitoes and may lead to seasonal outbreaks, although many cases are solitary (1). F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and tularensis are the clinically important subspecies. Strains of the latter subspecies are highly virulent and may cause lethal disease, whereas strains of the former subspecies show lower virulence and are lethal for humans only in exceptional cases. Regardless of the subspecies, F. tularensis strains are highly infectious, and as few as 10 bacteria can elicit infection in humans (1). There has been a renewed interest in Francisella during the past decade, since its high infectivity and the subsequent serious disease has resulted in its categorization as a CDC tier 1 agent, i.e., a member of a group including the most likely bioterrorist agents.

The renewed interest in research on Francisella has led to an intense effort to understand the virulence of this potent pathogen. Some of the work has been combined with studies of attenuated F. tularensis strains. The best known of these is the live vaccine strain LVS (2). The precursor of LVS was derived from a Russian isolate of F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and was attenuated by repeated passages in vitro. The LVS strain was subsequently derived in the United States from the precursor, and it has been used for vaccination of at-risk individuals in several countries and also widely used in the mouse experimental model of tularemia. Comparative genomic analyses identified a genomic region containing two genes that were partially deleted in LVS (3). Subsequent work found that one of these genes, fupA, encodes a protein that is an important virulence factor and is essential for regulation of iron uptake (4). Notably, this deletion appears to be the primary reason for the attenuation of the LVS strain, since complementation of FupA renders LVS as virulent as clinical isolates of F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (5). Moreover, the encoding fupA gene appears to be a hot spot for genomic arrangement, since several spontaneous mutants lack the same region (3). Despite its common use, protection afforded by LVS against laboratory-acquired tularemia is incomplete (6–8), and vaccination gives suboptimal protection against respiratory challenge in both humans and animals (7, 9), and this has been an incentive for the development of improved F. tularensis vaccines.

Our previous work has involved characterization of a spontaneous mutant of the highly virulent F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain SCHU S4. We demonstrated that it is essentially avirulent in mice and markedly impaired in replication in murine monocytes (10). Moreover, infection with the mutant resulted in long-lasting immunity and conferred effective protection against challenge with an F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain (10). Thus, understanding mechanisms behind its attenuation may reveal important clues for the development of a rationally attenuated F. tularensis vaccine. It was the first example showing that a safe and effective live vaccine could be derived from F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains. Several such vaccine candidates have been characterized more recently (11–18).

The genetic defects of FSC043 have been identified because the strain was included in a study aimed at understanding the genetic basis behind different mechanisms of attenuation of SCHU S4 (19). The genomes of the two F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains FSC043 and FSC198 were sequenced and compared, since the former most likely was derived by repeated passages of SCHU S4 on media, similar to LVS, whereas the latter is a naturally occurring mutant. Compared to SCHU S4, only four mutations were identified in FSC043, one of which was the aforementioned partial deletion of fupA and fupB, whereas the other three had not been described in other F. tularensis strains at that time. One of the mutations leads to premature translational termination of the gene encoding a putative metal ion transporter protein, FTT0615, while the other two mutations were homologous and localized in each of the two copies encoding the pdpC gene, also leading to premature translational termination (19).

The gene encoding PdpC is located in the gene cluster designated the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI), encoding an unusual variant of a type VI secretion system (T6SS) (20). The FPI region consists of almost 20 genes, many of which have been found to play critical roles in the unique intracellular life style of the bacterium (20, 21). After phagocytosis by monocytic cells, F. tularensis escapes from the phagosome before lysosome fusion and multiplies in the cytosol, eventually causing host cell death (22–26). Although no effector functions have been assigned to the proteins of the FPI, many of those studied so far have been found to be essential for phagosomal escape and intracytosolic replication of the pathogen, as well as modulation of the host response (14, 27–35). Several recent publications have addressed the role of PdpC by investigating the phenotypes of specific pdpC mutants or a spontaneous mutant (14, 35–37). Mutants derived from strain LVS or SCHU S4 have both demonstrated unique phenotypes, since they showed incomplete phagosomal escape, growth in only a small subset of macrophages, intermediate cytopathogenic effects, and marked attenuation in vivo but modulation of the macrophage inflammatory response similar to that of the parental strains (14, 35, 36). Very recently, a spontaneously attenuated SCHU S4 mutant was described (37). The reason for the attenuation was a nonsense mutation in pdpC; thus, the gene appears to be prone to spontaneous mutations. In contrast to the findings on these two subspecies, the pdpC mutant of Francisella novicida showed intact intracellular replication (38).

The aim of the present study was to better understand the mechanisms behind the attenuation of FSC043 and to characterize its phenotype in detail. To this end, we compared the phenotypes of several targeted deletion mutants of SCHU S4 and also performed complementation of FSC043.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

F. tularensis strains were grown either on modified Thayer-Martin agar at 37°C in 5% CO2 or in Chamberlain's medium at 37°C. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria agar (LA) plates at 37°C or in Luria broth (LB) at 37°C. The ΔfupA and ΔiglC mutants of SCHU S4 and strain FSC043 have been described previously (10). For construction of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing bacteria, all strains were transformed with pKK289Km-gfp (27). When required, antibiotics were added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml of kanamycin for F. tularensis or 50 μg/ml for E. coli. In-frame SCHU S4 ΔpdpC, ΔpdpE, ΔpdpC ΔpdpE, and ΔFTL0439 (a mutant carrying partially deleted and fused versions of the fupA and fupB genes identical to the deletions present in strains LVS and FCS043) deletion mutants were created by allelic replacement, as described previously (39); more than 90% of the respective open reading frames (ORFs) were deleted. Complementation of FSC043 with the fupA and fupB genes was performed following the same principles as for allelic replacement, resulting in an FSC043 strain expressing the fupA and fupB genes in cis under the control of their native promoter. The pdpC and pdpE genes were expressed by the pFNLTP6 vector under the GroE promoter. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was used to verify gene expression levels. The plasmids and strains used in the study are listed in Table 1. Primers are available upon request.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| F. tularensis | ||

| SCHU S4 | F. tularensis subsp. tularensis | FSCa |

| ΔpdpC | SCHU S4 with in-frame deletion of pdpC codons 6–1325 | This study |

| ΔiglC | SCHU S4 with in-frame deletion of iglC codons 28–205 | 10 |

| ΔFTL0439 | SCHU S4 with partial deletion of ORFs fupA and fupB, identical to ORF FTL0439 in LVS | This study |

| ΔpdpC ΔpdpE | SCHU S4 with in-frame deletion of ORFS FTT1354-FTT1355 and FTT1709-FTT1710 | This study |

| ΔpdpE | SCHU S4 with in-frame deletion of ORFS FTT1355 and FTT1710 | This study |

| FSC043 | Spontaneous mutant of SCHU S4 | 10 |

| pdpC pdpE | FSC043 complemented with pdpC and pdpE genes in trans | This study |

| fupA fupB | FSC043 complemented with fupA and fupB genes in cis | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| S17-1λpir | recA thi pro hsdR hsdM+, Smr <RP4:2-Tc:Mu:Ku:Tn7> Tpr | 54 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDMK3 | pDM4 derivative; Kmr | 55 |

| pFNLTP6groGFP | pFNL10 derivative; Kmr Cbr | 56 |

| pKK289Km | pKK214 derivative carrying gfp; Kmr | 27 |

FSC, Francisella Strain Collection, Swedish Defense Research Agency, Umeå, Sweden.

Microarray analysis.

Bacteria were grown on plates overnight before total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Superscript II (Invitrogen) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis of total RNA, and subsequent coupling of either Cy-3 or Cy-5 (Amersham) fluorophores was done to separate the two strains. Cy-3 and Cy-5 were switched in half of the reactions to compensate for technical differences between the two fluorophores. The cDNAs from the two strains were mixed. Prehybridization and hybridization using a Pronto! Universal Hybridization Kit were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Washing was done at 50°C in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.1% SDS, followed by 0.1× SSC. The F. tularensis arrays were obtained from BEI Resources (http://www.beiresources.org/). Four technical replicates were used for analysis. The arrays were scanned using the Scanarray 4000 XL microarray scanner (PerkinElmer) at three laser/photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltage settings. Images were analyzed using ScanarrayExpress software (PerkinElmer). The median signal intensities of the three scans were merged using restricted linear scaling (40) and normalized using print-tip MA-loess (41). The replicated genes were merged by their median intensity. Genes with top-ranked B statistics (42) and at least 3-fold regulated were classified as differentially expressed (40, 42). After identification, a normalization including local background correction was performed to estimate the regulations reported.

RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR).

The method of RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and PCR has been described previously (33). Statistical analysis was performed on ΔCT values using Student's two-tailed t test. FPI genes and genes identified by Twine et al. (10) were analyzed >4 times, while all other transcripts were tested twice. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Western blot analysis.

Bacterial lysates were prepared in Laemmli sample buffer and boiled prior to separation on 10 to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using a semidry blotter (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). Filters were incubated with antibodies specific to the IglA, IglB, IglC, or IglD protein as described previously (27, 33) or with polyclonal anti-IglH (α-IglH) and α-VgrG (Storkbio, Talinn, Estonia). For PdpC detection, a polyclonal antibody targeting the N-terminal part of PdpC, a kind gift from Katy Bosio and Jean Celli, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, MT, was used. Following incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies, proteins were visualized by addition of the ECL reagent (Amersham, GE Healthcare).

Proteomic analyses. (i) Growth conditions.

F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains SCHU S4 and FSC043 were grown as confluent lawns on cysteine heart agar supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) hemoglobin (CHAH). Bacteria were harvested after 48 to 72 h of incubation into 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 1% (wt/vol) dithiothreitol (DTT), 4% (wt/vol) CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}, and 0.5% (wt/vol) amidosulfobetaine-14 (ASB-14). ASB-14. The cell pellets were resuspended by vortexing and then shaken for 30 min at room temperature and incubated for at 4 h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min, the protein concentrations of the extracts were determined using a modified Bradford assay (43). Three independent growths were processed on three separate occasions, representing three biological repetitions: BR1, BR2, and BR3.

(ii) Protein digests and fractionation.

Aliquots of F. tularensis lysates containing 100 μg total protein were reduced in the presence of 5 mM DTT for 45 min, followed by alkylation with 15 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min. The proteins were then precipitated with acetone at −20°C and incubated overnight at −20°C. The precipitated proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The air-dried pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 0.1% SDS and trypsin digested overnight at 37°C. The resulting peptides were diluted in loading buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate and 30% acetonitrile, pH 3) and loaded onto a strong cation-exchange column (SCX; Applied Biosystems). The peptides were either eluted in elution buffer or, where indicated, fractionated in a step gradient using a mixture of load and elution buffers.

(iii) Nano-LC-MS.

For each BR, 10 μl of each peptide fraction was analyzed three times by nano-liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (nano-LC-MS) by alternating injections on a QTOF Ultima coupled to a CapLC capillary LC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Samples were separated on a 0.075-mm by 150-mm reversed phase column (PepMap C18 capillary column; Dionex/LC-Packings, San Francisco, CA) with a flow rate of 250 nl/min using a 50-min gradient of 5 to 75% B (100% ACN-0.2% formic acid). Continuum MS spectra were acquired in the time of flight (TOF)-MS mode between m/z 400 and 2,000 with an acquisition duration of 2 s per spectrum.

(iv) Auto-nano-LC–MS-MS analysis.

For each BR, 10 μl of peptides was analyzed by auto-nano-LC-tandem MS (MS-MS) on an LTQ XL linear trap mass spectrometer (Thermo) coupled to an MDLC chromatography system (GE Healthcare) or on a QTOF Ultima coupled to a CaplLC. Identification was performed separately from quantification to allow adequate sampling for quantification. MS and MS-MS data were collected in enhanced profile and normal centroid mode, respectively. MS-MS was triggered by automatic switching on the top two peptides with a 40-s dynamic-exclusion window and exclusion mass widths of 0.1 (low) and 1.5 (high). The collision-induced dissociation (CID) settings were as follows: isolation width, 1.0; normalized collision energy, 35; activation Q, 0.25; activation time, 30 ms.

(v) Data analysis and statistics for protein analysis.

Relative quantification was performed using in-house software, MatchRx, as previously described (44). Initial data analyses were performed independently on BRs before combining them for final relative quantification and statistical analyses. Each peptide ion was associated with a specific m/z, charge, and elution time profile, and its abundance was quantified by calculating the area under the curve of its elution time profile. Each peptide ion was then aligned among multiple samples, and relative abundance values were compared (44). All abundance values were normalized so that the median peptide abundances were equal for all runs in the data set. For statistical analyses, only multiply charged ions detected in at least two out of the three nano-LC-MS runs were included. The LC-MS data set was visualized using MSight Viewer (45). This was used for verification of the accuracy of the peptide alignments and matching. We performed a pairwise, two-sided t test between the corresponding MS runs and selected only those peptides with a P value of <0.01. For these significantly different peptides, the relative ratios were derived by calculating the fraction of aggregated intensities in the corresponding replicate runs. Since often more than one peptide per protein was detected, we combined these peptide ratios using a P value-based weighted average, as described previously (46). Relative abundance differences of 2-fold or greater were considered significant.

(vi) Peptide identification.

Peak lists were generated by Extract_msn in BioworksBrowser 3.3.1 build 7 using the default parameters. MS-MS spectra were searched against the Francisella SCHU S4 translated genome sequence database using SEQUEST within BioworksBrowser.

Infection of macrophages.

J774A.1 macrophages or bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were used in the cell infection assays. J774A.1 macrophages were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco). BMMs were generated by flushing bone marrow cells from the femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice. These cells were cultured for 4 days in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 5 μg/ml of gentamicin, and 20% conditioned medium (CM) from L929 cells (ATCC no. CCL-1) overexpressing macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), after which they were grown in medium lacking gentamicin. The CM was replaced every 2 or 3 days.

For all infections, BMMs or J774A.1 cells were seeded in tissue culture plates the day before infection in DMEM (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and then incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Following incubation overnight, the wells were washed and reconstituted with fresh culture medium. Bacteria were grown overnight and resuspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a density of approximately 2.5 × 109 bacteria/ml. Bacteria were added to each well at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100, and bacterial uptake was allowed to occur for 120 min at 37°C. After infection, the monolayers were washed three times, followed by incubation for the indicated periods in prewarmed DMEM with FBS supplemented with 5 μg/ml of gentamicin. The time point after the 120-min uptake was defined as 0 h.

At 0, 24, and 48 h, supernatants were collected for further analysis, and the macrophage monolayers were lysed in 0.1% deoxycholate in PBS. One hundred microliters of serial dilutions in PBS of the lysates were inoculated on plates containing GC II Agar Base (BD Diagnostic Systems, MD, USA) with the addition of hemoglobin and Isovitalex (BD Diagnostic Systems) and incubated at 37°C until colonies could be enumerated. The total number of bacteria per well was calculated. The assay was performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

Assay of cell cytotoxicity.

J774A.1 cells or BMMs were infected for 2 h, washed, and incubated in the presence of 5 μg/ml of gentamicin. The supernatants were sampled at 0, 24, or 48 h and assayed for the presence of released lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) using the Cytotox 96 Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance at 490 nm was determined using a microplate reader (Tecan Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). The data are means and standard deviations of three wells from one representative experiment of three. Uninfected macrophages lysed in PBS with 0.1% deoxycholate served as a positive control, and the value for this control was arbitrarily considered 100% cell lysis. Sample absorbance was expressed as a percentage of the positive-control value. The assay was performed with triplicate samples and repeated at least twice.

Intracellular immunofluorescence assay.

J774 cells (2.5 × 105/well) in DMEM plus 10% FBS were seeded onto glass coverslips in 24-well plates. The following day, the cells were infected with a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing F. tularensis strain at an MOI of 30 and then washed three times and fixed at 0 h, 3 h or 18 h. Fixation was carried out in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min to ensure complete killing of the virulent strains. Thereafter, the coverslips were washed with PBS and then permeabilized with 0.15% saponin, blocked in 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-saponin, and further incubated in blocking buffer with primary antibodies against the LAMP-1 glycoprotein diluted 1:700 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). Then, an anti-rat IgG antibody conjugated to Alexa 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added at a dilution of 1:1,000. After three washes in PBS, coverslips were mounted using Prolong gold mounting medium (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Glass slides were analyzed by use of an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioskop2; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany) or a confocal microscope (Nikon C1 confocal microscope; Nikon Instruments Europe B.V., Amstelveen, The Netherlands) for determination of the degree of colocalization of GFP-labeled F. tularensis and LAMP-1 staining. In total, 100 bacteria on each coverslip were scored; each stain was analyzed in triplicate, and experiments were repeated three times.

Electron microscopy.

J774 cells (2 × 106) in 6 ml DMEM plus FBS were seeded in 6-well tissue culture plates. The following day, the monolayers were infected with the indicated F. tularensis strains at an MOI of 50 for 1 h and then washed three times and further incubated for 18 h. Before fixation, the monolayers were rinsed briefly with DMEM and then fixed for 2 h at room temperature in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). Thereafter, the cells were washed with sodium cacodylate buffer and postfixed for 1 h with 1% osmium tetroxide and then washed again and contrasted with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 h. Following dehydration in an ethanol series, the cells were scraped off the dishes, and after centrifugation (3 min at 3,500 rpm) were embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut and contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate before viewing with a JEOL 1200 EX-II electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). To examine membrane integrity, at least 100 bacteria from different sections of duplicate samples were analyzed and categorized as (i) bacteria with intact/slightly damaged phagosomal membranes or (ii) bacteria with mostly degraded/absent membranes.

Statistical analysis for macrophage experiments.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc testing (Bonferroni) or a two-tailed Student's t test, was used to identify differences between groups. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 18.0, or Microsoft Excel.

Mouse infections.

For testing of SCHU S4, FSC043, ΔfupA, ΔiglC, ΔpdpC, ΔpdpE, ΔpdpCΔ pdpE, and ΔFTL0439 strains or FSC043 complemented with the fupA-fupB and/or pdpC-pdpE construct, specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, Quebec, Canada). The mice were maintained and used in accordance with the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals in a federally licensed, select agent-approved, small animal containment level 3 facility, National Research Council, Ottawa, Canada. The experiments had been approved by the IRB of the National Research Council, Ottawa, Canada. F. tularensis strains were injected in a volume of 50 μl intradermally. Intranasal (i.n.) challenge was performed on anesthetized mice (10 μl of inoculum was administered to each nare, followed by an equal volume of saline). The actual concentrations of inocula were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions. The mice were examined daily for signs of infection and were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation as soon as they displayed signs of irreversible morbidity.

For vaccination purposes, mice were infected with the indicated doses of each mutant and challenged 5 weeks later either intradermally or via aerosol. The mice were followed for 28 days after challenge, and survival was recorded.

RESULTS

FSC043 demonstrated prominent gene downregulation.

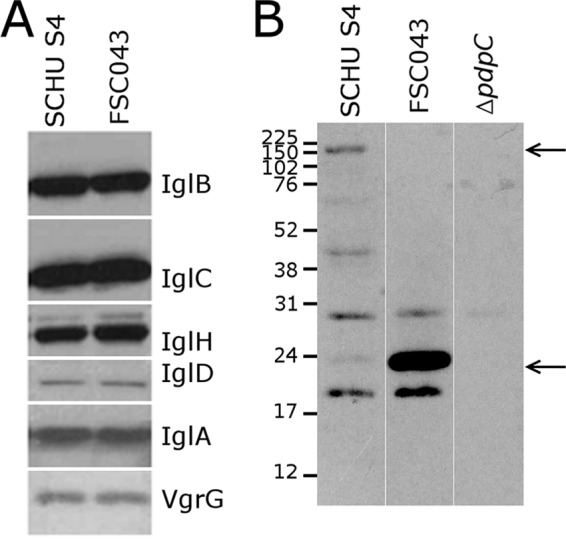

To characterize the gene expression of FSC043 and compare it to SCHU S4, a whole-genome microarray analysis was performed. Overall, 19 genes were found to be differentially expressed in comparison to SCHU S4 (Table 2). Among these genes, we identified downregulation of the fusion gene fupA-fupB (FTT0918-FTT0919), as well as pdpC. Besides these genes, many other genes were downregulated in FSC043, e.g., a number of 30S and 50S ribosomal genes, as well as ATP synthase genes. To complement the microarray analyses, a peptide-based proteomics screen was performed using nano-LC–MS-MS comparisons of FSC043 and SCHU S4 (Table 3). We identified a number of differences in expression between strains FSC043 and SCHU S4. In agreement with the microarray data, a multitude of ribosomal proteins were markedly downregulated in FSC043, but also, some upregulated ribosomal proteins were identified. The proteomic analysis identified a few FPI proteins, i.e., IglD, IglC, and IglA, as downregulated; however, this was not verified by RT-PCR (Tables 2 and 3). To resolve this ambiguity, a Western blot analysis of the FPI proteins IglA, -B, -C, -D, and -H and VgrG was performed and showed no obvious differences in protein levels between FSC043 and SCHU S4 (Fig. 1A). The levels of most FPI proteins were low, and the levels of the tryptic FPI peptides detected in the proteomic analysis were close to the detection limit, and therefore, the detected differences were somewhat uncertain, which could explain the discrepant results between the methods.

TABLE 2.

Summary of genes tested by microarray analysis and RT-qPCR

| ORF | Expressiona |

Gene | Protein name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray | qPCR | |||

| FTT0049 | −1.08 | −20.60 | nusA | N utilization substance protein A |

| FTT0061 | −7.14b | −2.93 | atpH | ATP synthase delta chain |

| FTT0068 | 3.82c | sodB | Superoxide dismutase [Fe] | |

| FTT0087 | −2.30 | 8.30c | acnA | Aconitate hydratase |

| FTT0139 | −1.92 | −2.37 | nusG | Transcription antitermination protein NusG |

| FTT0143 | −2.93b | 0.09 | rplL | 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 |

| FTT0144 | −2.74 | 0.89 | rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase beta chain |

| FTT0192 | −34.81 | lysU | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| FTT0330 | −4.52b | −6.57 | rplV | 50S ribosomal protein L22 |

| FTT0348 | −4.65b | −15.78c | rpsK | 30S ribosomal protein S11 |

| FTT0380c | −4.65b | −3.28 | gdh | NAD(P)-specific glutamate dehydrogenase |

| FTT0409 | −4.12 | −3.97 | gcvP1 | Glycine dehydrogenase subunit 1 |

| FTT0709 | −2.07 | −2.91c | eno | Enolase (2-phosphoglycerate dehydratase) |

| FTT0918 | −5.98 | −13.03 | fupA | Ferric uptake protein A (specific for the part present in FSC043) |

| FTT0963c | −2.51 | 1.17 | aroG | Phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase |

| FTT1003c | 1.08 | −1.39 | pheS | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase |

| FTT1129 | −17.62 | Hypothetical protein FTT1129c | ||

| FTT1269c | −1.21 | 0.59 | dnaK | Chaperone protein DnaK (heat shock protein family 70 protein) |

| FTT1275 | −1.76 | mglA | Macrophage growth locus subunit A | |

| FTT1276 | −1.45 | mglB | Macrophage growth locus subunit B | |

| FTT1344 | 1.65 | 6.26 | pdpA | Pathogenicity determinant protein A |

| FTT1345 | 1.98 | 1.07 | pdpB | Pathogenicity determinant protein B |

| FTT1346 | 1.31 | 1.74 | iglE | Intracellular growth locus protein E |

| FTT1347 | 1.14 | 1.62 | vgrG | Valine-glycine repeat G |

| FTT1348 | 1.40 | 1.70 | iglF | Intracellular growth locus protein F |

| FTT1349 | 1.08 | 1.46 | iglG | Intracellular growth locus protein G |

| FTT1350 | 1.10 | 1.75 | iglH | Intracellular growth locus protein H |

| FTT1351 | 1.04 | dotU | Defect in organelle trafficking U | |

| FTT1352 | 1.04 | 2.01 | iglI | Intracellular growth locus protein I |

| FTT1353 | −1.01 | −0.31 | iglK | Intracellular growth locus protein K |

| FTT1354 | −15.03b | −122.61c | pdpC | Pathogenicity determinant protein C |

| FTT1355 | −1.08 | −33.18c | pdpE | Pathogenicity determinant protein E |

| FTT1356 | 1.05 | 1.01 | iglD | Intracellular growth locus protein D |

| FTT1357 | −1.27 | 0.82 | iglC | Intracellular growth locus protein C |

| FTT1358 | −1.20 | 2.23 | iglB | Intracellular growth locus protein B |

| FTT1359 | 1.03 | 2.03 | iglA | Intracellular growth locus protein A |

| FTT1360 | 1.29 | 4.34 | pdpD | Pathogenicity determinant protein D |

Fold regulation.

Value was significantly differentially expressed (see Materials and Methods).

Value was significantly differentially expressed (P < 0.02).

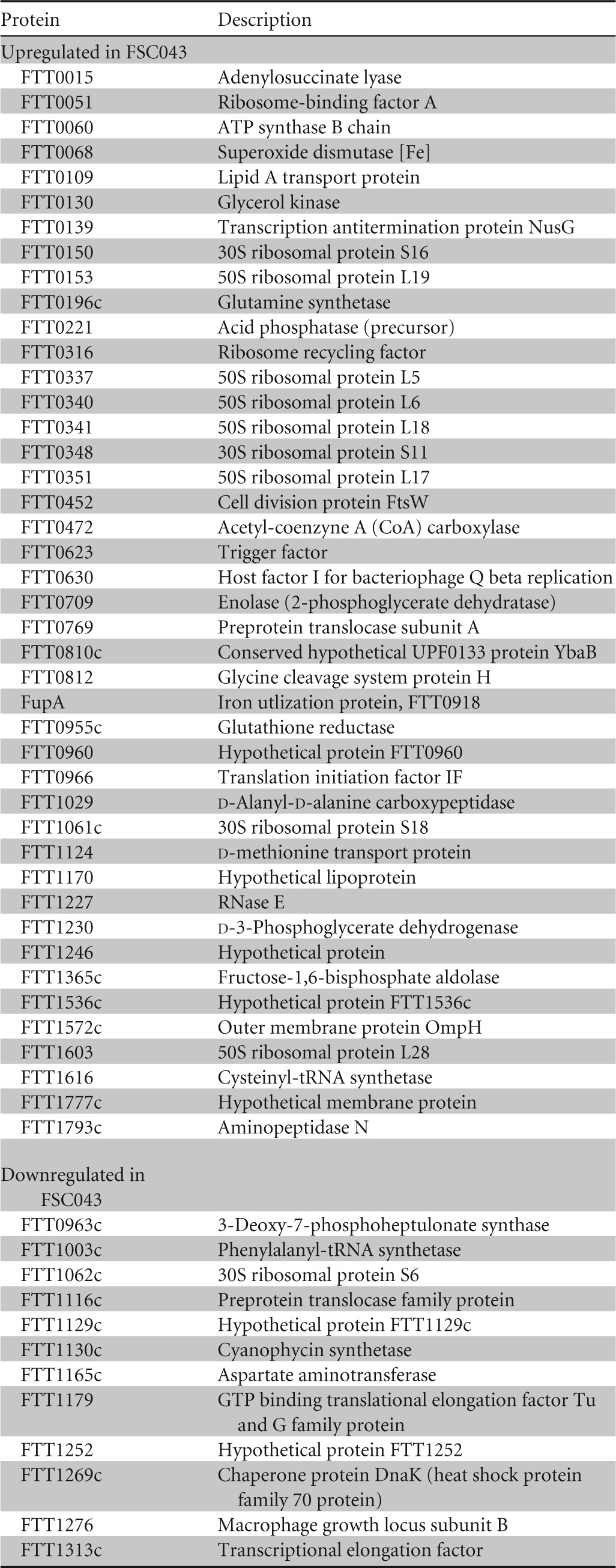

TABLE 3.

Proteins determined to be differentially expressed using mass spectrometry-based proteomicsa

The data listed are the means of biological repeats.

FIG 1.

Western blot analysis of the Francisella pathogenicity island proteins. Lysates from strains SCHU S4 and FSC043 were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and probed with an antibody to the indicated F. tularensis proteins. (A) Western blot analysis of selected FPI proteins revealed no differences between strains FSC043 and SCHUS4. (B) The truncated form of PdpC (26 kDa) is present in FSC043 in contrast to the full-length form (156 kDa) (arrows), which is visible only in the SCHU S4 lysate. There are also a number of nonspecific bands due to the reactivity of the polyclonal antibody used for detection.

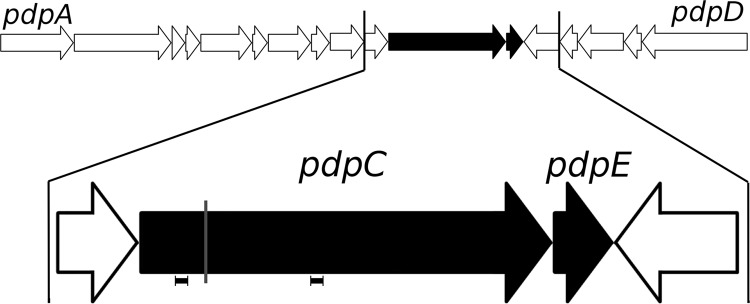

Since microarray analysis may not detect discrete regulation, expression of selected genes was also studied by use of quantitative RT-PCR (Table 2). One of the most interesting qPCR results was the finding that the gene downstream of pdpC (FTT1354), pdpE (FTT1355) (an overview of the genomic region is presented in Fig. 2), was also downregulated (Table 2), and it suggests that the genes are expressed in the same operon, as previously suggested (10). This downregulation was also validated by the proteomic analysis (Table 3). Although most parts of the pdpC gene were severely downregulated, 33-fold lower (P < 0.001) than in SCHU S4, the part upstream of the nonsense mutation did not differ significantly from the expression in SCHU S4, 1.1-fold lower than SCHU S4 (P < 0.001). The nonsense mutation identified in the pdpC gene (19) has been predicted to lead to a premature stop codon (localized 643 bp downstream of the transcriptional start site) (Fig. 2), resulting in a truncated protein of approximately 26 kDa, which was confirmed using Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B). The gene FTT0615 also contains a nonsense mutation in FSC043 (19) and was included in the RT-qPCR analysis, but since its expression is very low in SCHU S4, we could not determine if the expression was affected in FSC043.

FIG 2.

Map of the FPI region of F. tularensis. The pdpC and pdpE genes (black arrows) and the two adjacent genes are magnified. The location of the spontaneous mutation in the pdpC gene in FSC043 is indicated by a gray line. The locations of the primers used for RT-qPCR analysis are indicated by horizontal bars. The arrows indicate the direction of transcription.

In conclusion, FSC043 showed very distinct gene and protein expression patterns compared to SCHU S4, and in particular, numerous ribosomal proteins were differentially expressed. Most FPI genes appeared not to be affected, while pdpE and most of the pdpC gene were not expressed.

FSC043, as well as the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, but not the ΔpdpE mutant, showed impaired intracellular growth and marked attenuation.

As part of a phenotypic characterization of the F. tularensis strains, their intracellular replication in J774 cells was followed. We generated specific SCHU S4 deletion mutants that targeted genes whose expression deviated between SCHU S4 and FSC043 and also included the previously described ΔfupA and ΔiglC mutants (10). To this end, the ΔFTL0439 mutant, harboring the same partial deletions and fusion of the fupA and fupB genes as FSC043, and ΔpdpC, ΔpdpE, and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants were generated and characterized.

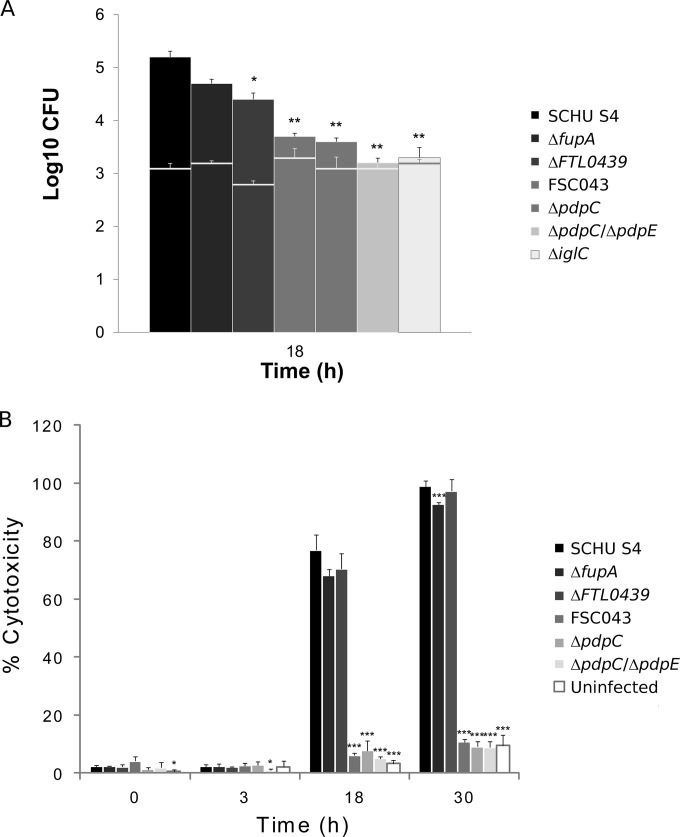

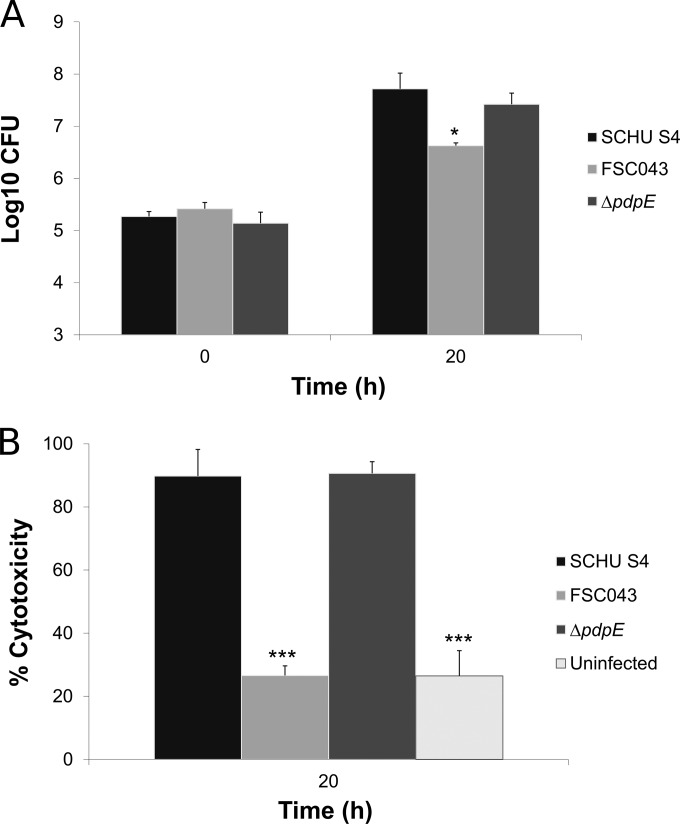

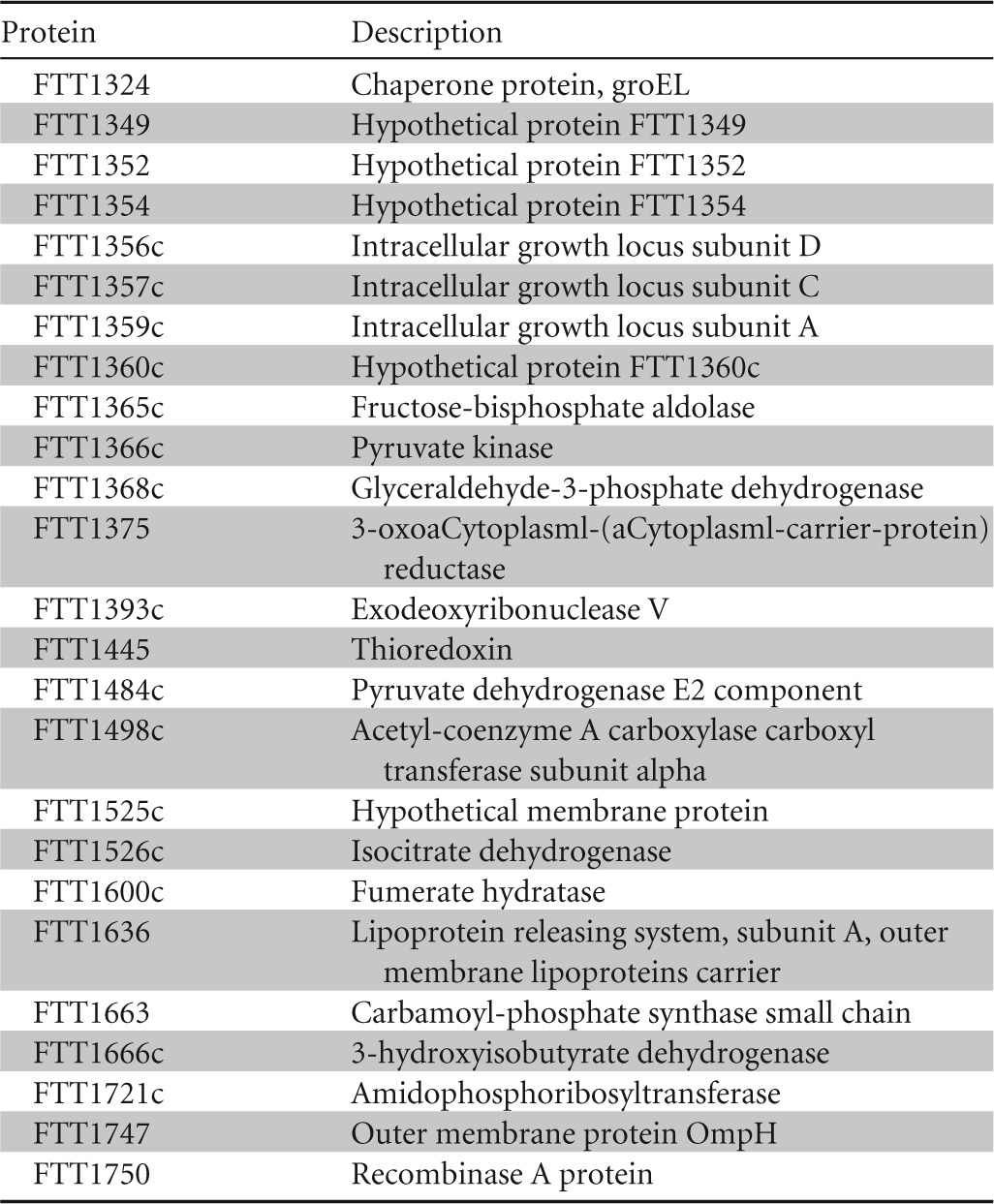

The SCHU S4 strain replicated at 2.1 log10 during 18 h of in vitro growth, and the infected J774 cells showed signs of severe cytotoxicity (Fig. 3A and B). Thereafter, a majority of the infected cells started to detach, and therefore, infection was not further followed. In contrast, the FSC043 strain was attenuated for growth (P < 0.01 versus SCHU S4), and although it replicated slightly, at 0.4 log10, during the first 18 h, it demonstrated no additional replication at 48 h (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Additionally, it failed to induce significant cytotoxicity at any time point (Fig. 3B and data not shown). The ΔfupA mutant, deficient in one of the genes only partially expressed in FSC043, and the ΔFTL0439 mutant were both slightly attenuated for growth in J774 cells (P < 0.05 versus SCHU S4) and replicated at approximately 1.5 log10, significantly more than FSC043 (P < 0.05 versus the ΔfupA mutant and P < 0.01 versus the ΔFTL0439 mutant), and both the ΔfupA and ΔFTL0439 mutants induced cytotoxicity like SCHU S4 (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, the ΔpdpC, ΔpdpC ΔpdpE, and ΔiglC mutants, like FSC043, showed essentially no replication (P < 0.01 versus SCHU S4) and did not induce any cytotoxicity (Fig. 3A and B). The ΔiglC mutant is a prototype for F. tularensis mutants incapable of phagosomal escape and intracellular replication. Separately, the behavior of the ΔpdpE mutant was investigated, and it was found to replicate as well as SCHU S4 in J774 cells (Fig. 4A) and BMMs (not shown) and showed the same degree of cytotoxicity as did SCHU S4 (Fig. 4B).

FIG 3.

F. tularensis infection of J774 cells. (A) Cells were infected for 1 h with the indicated F. tularensis strains at an MOI of 30 and then incubated for 18 h. Bacterial replication was determined and expressed as mean log10 CFU of triplicate wells. Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results. The horizontal lines indicate the bacterial numbers after uptake. The asterisks indicate that the bacterial numbers were significantly different from the replication of the SCHU S4 strain at the indicated time point (*, P ≤ 0.05;**, P ≤ 0.01). (B) Culture supernatants of the infected J774 cells were assayed for LDH activity at the indicated time points, and the activity was expressed as a percentage of the level of noninfected lysed cells. Means and standard deviations (SD) of triplicate wells from one representative experiment of at least two are shown. The asterisks indicate that the cytotoxicity levels were significantly different from those of SCHU S4-infected cells for a given time point, as determined by a t test (*, P ≤ 0.05;***, P ≤ 0.001).

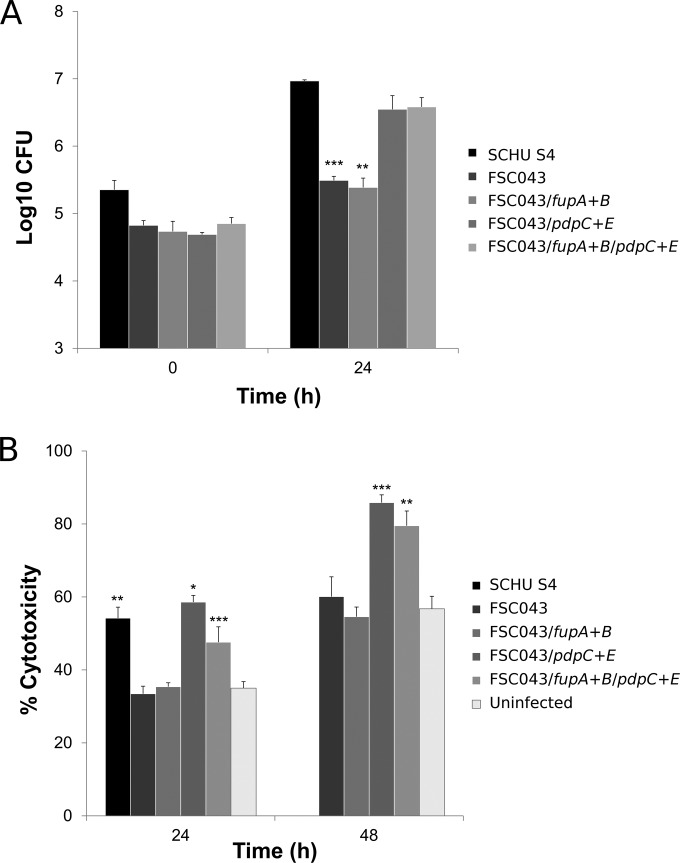

FIG 4.

Infection of J774 cells with the ΔpdpE mutant. (A) Cells were infected for 1 h with the indicated F. tularensis strains at an MOI of 30 and then incubated for 20 h. Bacterial replication was determined and expressed as mean log10 CFU of triplicate wells. Experiments were repeated twice with similar results. The asterisks indicate that the bacterial numbers were significantly different from the replication of the SCHU S4 strain at the 20-h time point. (*,P ≤ 0.05). (B) Culture supernatants of the infected J774 cells were assayed for LDH activity at the indicated time points, and the activity was expressed as a percentage of the level of noninfected lysed cells. Means and standard deviations of triplicate wells from one representative experiment of two are shown. The asterisks indicate that the cytotoxicity levels were significantly different from those of SCHU S4-infected cells for the 20-h time point, as determined by a t test (***, P ≤ 0.001).

The virulence of the deletion mutants was also characterized in the mouse model after intradermal challenge. The ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, like FSC043, showed very marked attenuation, and all mice survived an inoculum of 107 CFU, whereas the ΔfupA mutant showed a 50% lethal dose (LD50) of approximately 103 CFU, the ΔFTL0439 mutant showed an LD50 of 102 CFU, and the ΔpdpE mutant appeared to be fully virulent, with an LD50 of <40 CFU (time to death, 7.0 ± 0.2 days).

In summary, the data show that FSC043 displayed a phenotype similar to that of the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, characterized by minimal intracellular growth and lack of cytotoxicity, whereas the ΔfupA, ΔpdpE, and ΔFTL0439 mutants replicated almost as efficiently as did SCHU S4, and all four strains induced similar degrees of cytotoxicity. The degree of intracellular replication correlated with the virulence of the mutants, since the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, like FSC043, were essentially avirulent, whereas the ΔfupA and ΔFTL0439 mutants showed high virulence, although not as high as SCHU S4, and the ΔpdpE mutant was found to be fully virulent.

FSC043 showed impaired phagosomal escape.

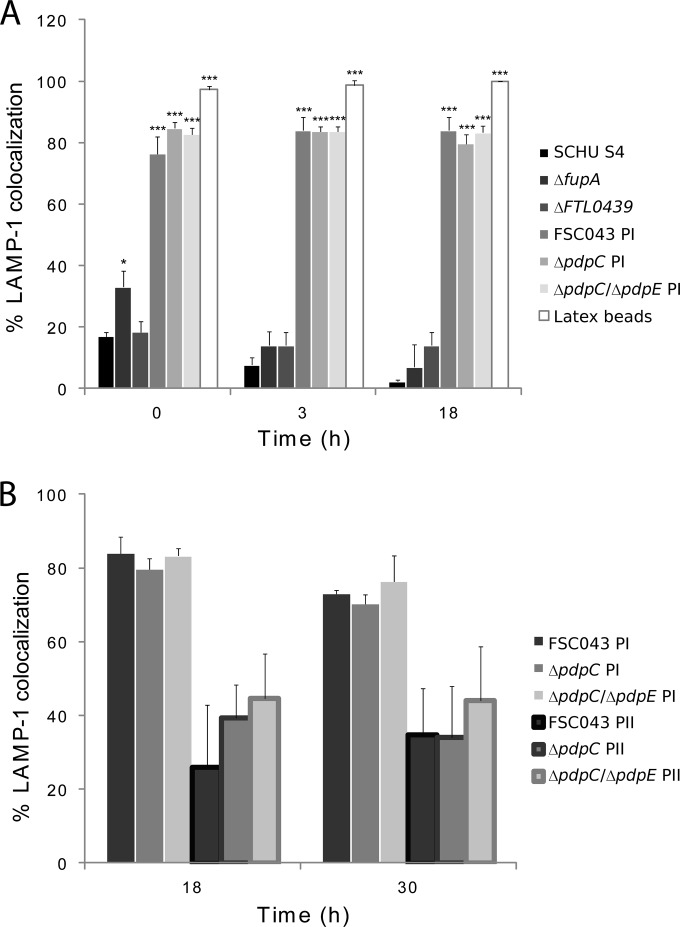

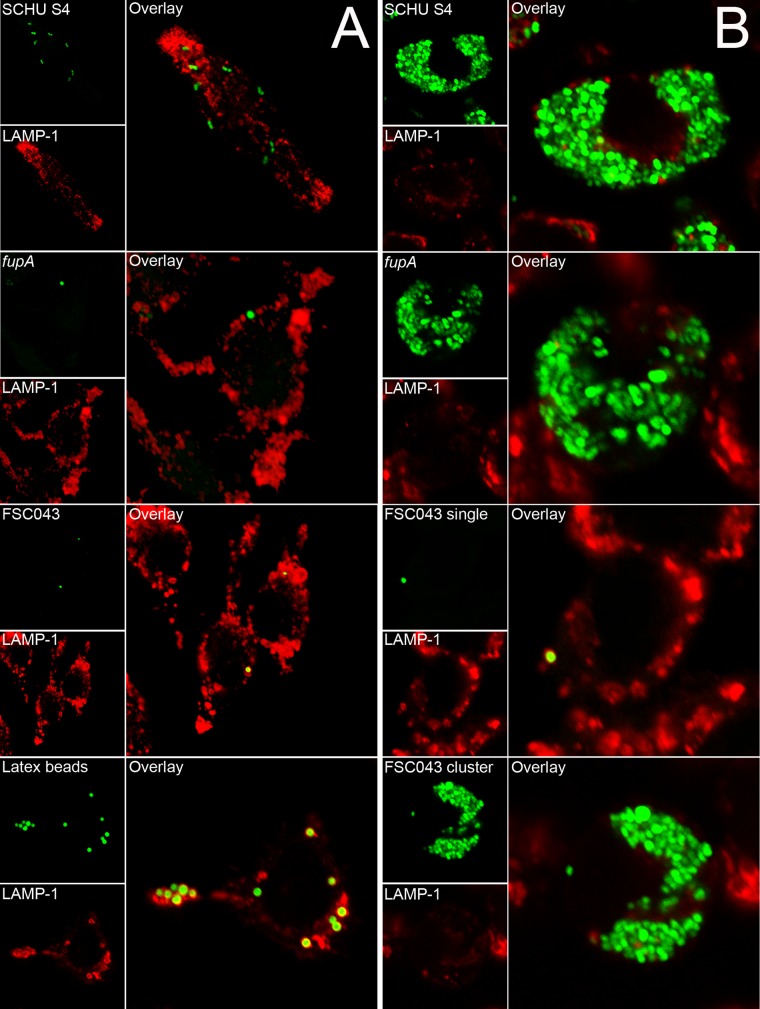

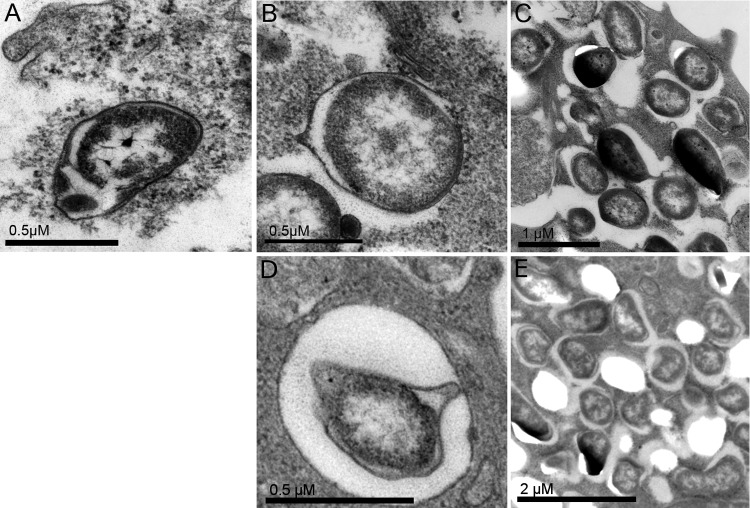

A prerequisite for the virulence of F. tularensis is its phagosomal escape, since it replicates in the cytosol of phagocytic cells. Many attenuated FPI mutants have been found to be defective for phagosomal escape, and to investigate if the FSC043 and pdpC mutants showed such defects, the infected cells were stained with LAMP-1, which is a late endosomal and lysosomal marker acquired within 30 min by the Francisella-containing phagosome (27, 28, 30, 31, 47, 48). Only a minority of the SCHU S4 bacteria colocalized with LAMP-1 at any of the time points investigated, 0, 3, and 18 h (Fig. 5A), and this was in agreement with previous studies (28, 48–50), while a majority of the ΔiglC mutant bacteria remained colocalized with LAMP-1 for up to 18 h, as reported for the corresponding LVS mutant (27). The ΔfupA and ΔFTL0439 mutants effectively escaped from the phagosome, whereas the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, similar to the ΔiglC mutant, were defective for phagosomal escape (Fig. 5A). The FSC043, ΔpdpC, and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants showed aberrant behavior, since approximately 95% of the infected cells contained only a few bacteria, 80% of which, designated population I, were localized within LAMP-1-positive vacuoles at 0, 3, and 18 h (P < 0.05 versus 3 h) (Fig. 5A and B and 6A). The remaining 5% of the cells contained large numbers of bacteria, designated population II, but only 26 to 35% of them colocalized with LAMP-1 (Fig. 5B). This percentage increased to 35 to 44% at 30 h. At 18 h, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed these findings and showed that 50% of the FSC043 bacteria localized adjacent to phagosomal membranes, whereas the remaining bacteria had cytoplasmic localization, in contrast to the ΔiglC mutant, which showed >90% phagosomal localization (Table 4 and Fig. 7).

FIG 5.

Quantification of LAMP-1 colocalization with F. tularensis strain SCHU S4. J774 cells were infected for 1 h with the indicated F. tularensis strains at an MOI of 30 or latex beads at an MOI of 10, and after washing, they were further incubated for up to 18 h. Fixed samples were labeled for the late endosomal/lysosomal marker LAMP-1. (A) Percentages representing the fractions of F. tularensis- or latex bead-containing phagosomes stained for the late endosomal/lysosomal marker LAMP-1. (B) A separate analysis was performed for strain FSC043 at 18 h. LAMP-1 colocalization was determined for two populations of bacteria observed in infected host cells: (i) a majority (95%) of J774 cells with individual bacteria (designated PI) and (ii) a minority (5%) of J774 cells with clusters of replicating bacteria (designated PII). The results are expressed as mean values and SD from one representative experiment in which 100 bacteria each on triplicate coverslips were counted. The asterisks indicate colocalization levels significantly different from those of SCHU S4 for each time point. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, according to a t test. Experiments were repeated 2 to 4 times for the 0- and 3-h time points and twice for the 18-h time point.

FIG 6.

Colocalization of GFP-expressing F. tularensis strains and the late endosomal marker LAMP-1. J774 cells were infected for 1 h with the indicated F. tularensis SCHU S4 strain at an MOI of 30 or latex beads at an MOI of 10 and further incubated for 3 h (A) or 18 h (B). In the representative confocal images, the green channel shows bacteria or latex particles and the red channel shows LAMP-1 staining for the indicated strain or latex beads. Confocal images were acquired with the Nikon C1 confocal microscope and assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

TABLE 4.

TEM assay of phagosomal-membrane integrity of J774 cells infected with F. tularensis strainsa

| Strain | Membrane integrityb (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Intact/partly degraded | Mostly degraded/absent | |

| SCHU S4 | 9.8 | 90.2 |

| FSC043 | 50.2 | 49.8 |

| ΔiglC | 90.3 | 9.7 |

J774 cells were infected for 1 h at an MOI of 50, washed, further incubated for 18 h, and then processed for TEM.

To examine membrane integrity, at least 100 bacteria from different sections of duplicate samples were analyzed for each time point and categorized as follows: I, bacteria with an intact or partly degraded phagosomal membrane; II, bacteria with mostly degraded or absent membranes.

FIG 7.

Electron micrographs of J774 cells infected for 1 h with F. tularensis FSC043 or SCHU S4, the ΔiglC mutant, or the ΔiglC mutant and then further incubated for 18 h. (A) The ΔiglC strain. (B and C) A host cell containing an individual FSC043 bacterium enclosed by a phagosomal membrane (B) and a host cell containing a cluster of FSC043 bacteria without discernible phagosomal membranes (C). (D and E) A host cell containing an individual ΔpdpC mutant bacterium enclosed by a phagosomal membrane (D) and a host cell containing a cluster of ΔpdpC mutant bacteria without discernible phagosomal membranes (E). The electron micrographs were acquired with a JEOL 1200 EX-II electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Altogether, these findings demonstrate that ΔfupA and ΔFTL0439 mutants, like SCHU S4, effectively escaped from the phagosome, whereas FSC043 and the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants showed predominantly phagosomal localization. However, a small subset of bacteria of each of the three strains appeared to replicate, and they showed low degrees of LAMP colocalization.

Complementation with the pdpC and pdpE genes, but not the fupA and fupB genes, restored intracellular replication and virulence of FSC043.

Since FSC043 shows minimal intracellular replication and lacks virulence in the mouse model (10), we asked if complementation with the SCHU S4 genes that are not expressed in the strain would restore a virulent phenotype. To investigate this, we expressed the three constructs containing the pdpE gene, the pdpC and pdpE genes, or the complete fupA and fupB genes, which are missing or not expressed in FSC043, under the control of the strong F. tularensis GroE promoter for pdpE or pdpC and pdpE or their native promoter for fupA and fupB. The constructs were expressed in FSC043 either individually or together and tested for intracellular growth in J774 cells (data not shown) and BMMs with similar results. The recombinant expression of pdpE (not shown) or the fupA and fupB genes did not change the phenotype, since the mutants, like FSC043, showed only minimal intracellular replication in BMMs (Fig. 8A). In contrast, expression of the pdpC and pdpE gene or pdpC and pdpE gene and fupA and fupB gene recombinant constructs dramatically affected the phenotype, since the intracellular replication of both these mutants was indistinguishable from that of SCHU S4 (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the LDH release was marked and as high as for SCHU S4 when FSC043 was complemented with pdpC and pdpE, but not when complemented with fupA and fupB (Fig. 8B) or pdpE (not shown).

FIG 8.

Intracellular replication and cytotoxicity in BMMs of F. tularensis strains. (A) BMMs were infected by the indicated strains of F. tularensis at an MOI of 200 for 2 h. Upon gentamicin treatment, the cells were allowed to recover for 30 min, after which they were lysed immediately (0 h) or after 24 h and plated to determine the number of viable bacteria (log10). All infections were repeated twice, with triplicate data sets, and a representative experiment is shown. Each bar represents the mean value, and the error bar indicates the standard deviation. The asterisks indicate that the log10 number of CFU was significantly different from that of the FSC043 strain as determined by a 2-sided t test with equal variance (**, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001). (B) The cytotoxicity of the infected BMMs was determined using the LDH assay (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001). No bar is shown for the 48-h time point for SCHU S4, since all cells had lysed before that.

The complemented mutant strains were also characterized by assessing their virulence in the mouse model after intradermal challenge. Previously, we observed that FSC043 shows dramatic attenuation, since not even a challenge of 108 CFU is lethal, whereas the LD50 of SCHU S4 is approximately 1 CFU and the strain usually kills mice within 6 days (10). Therefore, groups of mice were challenged with 100 CFU of the three complemented FSC043 strains. All of the mice infected with the mutant expressing the fupA and fupB genes survived until the end of the experiment, 28 days (Table 5). In contrast, one mouse infected with the mutant expressing the pdpC and pdpE genes died after 8 days, whereas all the others survived 28 days, and all five mice infected with the mutant expressing genes of both constructs died within 6.4 ± 0.3 days (Table 5). When higher doses of the mutants expressing genes of either of the constructs were given, three of five mice administered 103 CFU of the pdpC-pdpE construct died after 6.7 ± 0.4 days and all five mice given 105 CFU died after 6.0 ± 0.2 days (Table 5). However, no mice died after administration of 107 CFU of the mutant expressing genes of the fupA-fupB construct or 5 × 106 CFU of the mutant expressing pdpE (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Survival of mice following intradermal challenge with complemented strainsa

| Challenge strain | Time to death (days)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 102 CFU | 103 CFU | 107 CFU | |

| FSC043/fupA fupB | >28 | >28 | >28 |

| FSC043/pdpC fupE | 8, >28 (4) | 6, 7, 7, >28, >28 | 5, 6, 6, 6, 7 |

| FSC043/fupA fupB pdpC pdpE | 6, 6, 6, 7, 7 | NA | NA |

Groups of five mice were challenged with various doses of the indicated strains and monitored for 28 days for signs of illness.

The number in parentheses is the number of mice with the preceding time to death. NA, not applicable.

In summary, expression of the genes of the pdpC-pdpE construct was necessary for intracellular replication and virulence, since FSC043 and the strain expressing the genes of the fupA-fupB construct showed only minimal intracellular replication and an LD50 of >107 CFU. In contrast, expression of the genes of the pdpC-pdpE construct restored intracellular replication and markedly affected virulence, since the LD50 was approximately 103 CFU. For high virulence, similar to that of SCHU S4, the concomitant expression of both the pdpC and pdpE genes and the intact fupA and fupB genes was needed, leading to an LD50 of <102 CFU.

Vaccination with the mutants confers varying degrees of protection against SCHU S4 challenge.

In our previous study of the vaccine properties of FSC043, we observed that it conferred significant protection, similar to the LVS strain (10). In light of the new genomic information regarding FSC043, we wanted to compare how mutants in the affected genes conferred protection. All five of the mutant strains provided efficient protection (P < 0.005 versus naive mice) against an intradermal challenge with ∼1,000 lethal doses of SCHU S4 (Table 6). There were marked differences in their efficacies in protecting against an intranasal challenge with 25 lethal doses of SCHU S4, however, and regardless of the dose, the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants did not confer any significant protection, with a median survival of 8 days versus 6 days for naive mice, whereas FSC043 and ΔfupA conferred intermediate protection (P < 0.01 versus naive mice) and some of the mice survived until the experiment was terminated at day 28 (Table 6). In contrast, the ΔFTL0439 mutant conferred highly significant protection, and all of the mice survived until day 28 (P < 0.001 versus naive mice); this was superior to the protection conferred by the FSC043 or ΔfupA mutant (P < 0.05 for both).

TABLE 6.

Survival of mice following immunization with mutant strains of SCHU S4

| Vaccine strain | Vaccine dose | Time to death (days)c | Median time to death (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intradermal challengea | |||

| None | None | 4, 5, 5, 5, 5 | 5 |

| ΔFTL0439 | 10 | >28 (5) | >28 |

| ΔfupA | 103 | >28 (5) | >28 |

| ΔpdpC ΔpdpE | 107 | 5, 13, >28 (3) | >28 |

| FSC043 | 107 | 6, >28 (4) | >28 |

| ΔpdpC | 103 | 7, 9, 25, >28 (2) | 25 |

| ΔpdpC | 107 | 5, >28 (4) | >28 |

| Intranasal challengeb | |||

| None | None | 5, 6, 6, 6, 6 | 6 |

| ΔFTL0439 | 10 | >28 (5) | >28 |

| ΔfupA | 103 | 10, 11, 21, 22, >28 | 21 |

| ΔpdpC ΔpdpE | 107 | 7, 8, 8, 9, 10 | 8 |

| FSC043 | 107 | 9, 13, 13, >28 (2) | 13 |

| ΔpdpC | 103 | 7, 7, 8, 8, 8 | 8 |

| ΔpdpC | 107 | 7, 7, 7, 8, 9 | 7 |

Five-week-old immune mice were challenged with 2,400 CFU of strain SCHU S4. The mice were followed for 28 days after challenge.

Five-week-old immune mice were challenged with 25 CFU of strain SCHU S4. The mice were followed for 28 days after challenge.

The numbers in parentheses are the numbers of mice with the preceding time to death when more than 1.

Altogether, the highly attenuated ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants conferred protection against intradermal challenge but not against intranasal challenge, whereas FSC043, despite being highly attenuated, and the less attenuated ΔfupA strain conferred full protection against intradermal challenge and intermediate protection against intranasal challenge; some of the latter mice survived for the whole study period. In contrast, the ΔFTL0439 mutant provided highly efficacious protection against both intradermal and intranasal challenge, and all mice survived during the study period.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to understand how the previously identified mutations present in strain FSC043, a spontaneous mutant of the highly virulent strain SCHU S4, contributed to its unique phenotype. To this end, we compared the phenotype of the strain with those of specific deletion mutants in the known mutated genes of FSC043: fupA, fupA and fupB (ΔFTL0439), pdpC, and pdpC and pdpE. In addition, we also performed complementation of the two chromosomal segments that are missing (fupA-fupB) or not expressed (pdpC-pdpE) in FSC043 in order to infer the contributions of each of the genes. Our characterization identified several interesting phenotypes that collectively help to explain the unique phenotype of FSC043. We observed that the ΔfupA and ΔFTL0439 mutants were slightly attenuated for growth in monocytic cells but still demonstrated as distinct toxicity as did SCHU S4. This phenotype markedly differs from that of FSC043 and implies that the mutation, although it may contribute to the attenuation of FSC043, does not explain its peculiar intracellular phenotype and lack of virulence. In this regard, our finding that the nonsense mutation in both copies of pdpC resulted in expression of only the 5′ end of the gene and also in the lack of expression of pdpE was of considerable interest. There have been several recent publications concerning PdpC, and collectively, they have identified it as an FPI protein with unique functions (14, 35). For example, we have observed that the ΔpdpC mutant of LVS shows no multiplication, aberrant phagosomal escape, and lack of virulence, and Long et al. demonstrated that a pdpC mutant of SCHU S4 shows a very similar phenotype (14, 35). Thus, the previous findings on the ΔpdpC mutants, regardless of genetic background, show great similarity to our findings on FSC043. In addition, it was recently reported that repeated in vitro passages of SCHU S4 led to a spontaneous single-nucleotide mutation of both copies of pdpC (37). Thus, the findings are highly similar to the findings on FSC043. Moreover, our findings on the SCHU S4 ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants likewise showed that they exhibit minimal intracellular replication, very marginal cytotoxicity, and lack of virulence in the mouse model. In addition, we observed that the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants replicated in a small subset of macrophages, as previously demonstrated by Long et al. for the SCHU S4 ΔpdpC mutant (14). Moreover, our data provide no evidence that the deletion of the pdpE gene, in the absence of pdpC, affects the phenotype of the SCHU S4 mutants, and furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that the ΔpdpE mutant of LVS is fully virulent and shows intact phagosomal escape and normal cytotoxicity during intracellular infection (20), as did the SCHU S4 ΔpdpE mutant characterized in the present study. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence that the lack of a functional PdpC is the most likely explanation for the peculiar phenotype of FSC043. Our findings also demonstrate that the absence of phagosomal escape renders F. tularensis mutants highly attenuated, and this completely obscures the role of major virulence factors, such as FupA, since their absence or presence does not affect virulence when bacteria are confined to the phagosome.

Unlike our SCHU S4 ΔpdpC deletion mutant, the previous study employed an intron insertion mutant of pdpC, and since the intron was located inside the gene, it is possible that this would affect the phenotype in a different way than a complete gene deletion (14). However, coincidentally, the intron insertion was located in the proximity of the premature stop codon of pdpC in FSC043, and the similar phenotypes of the two pdpC mutants and FSC043 indicate that the N-terminal end of PdpC does not affect the phenotype. Furthermore, our analysis of the expression of FPI components other than PdpC and PdpE revealed that IglA, IglB, IglC, IglD, IglH, and VgrG were expressed at normal levels, making it unlikely that other components of the T6SS contributed to the FSC043 phenotype. Therefore, the lack of full-length PdpC expression appears to be sufficient to explain the unique intracellular phenotype and lack of virulence exhibited by FSC043. One of the most remarkable findings related to FSC043 is the presence of identical nonsense mutations in the two copies of the pdpC gene. Presumably, this has occurred as a result of homologous recombination; however, it is difficult to envision how this clone was originally selected, since we have not observed any growth defect or macroscopic phenotype that distinguishes it from the parental strain (35). Also, we have consistently found that inactivation of only one copy of an FPI gene does not result in any phenotypic change compared to the parental strain. One possibility is that a SCHU S4 derivative that contained the nonsense mutation in one copy of pdpC was subjected to repeated animal passages, and thereby, the attenuated clone with duplicated mutations was selected by virtue of its marked attenuation, but this has not been documented in any publication.

The phenotype of FSC043 resembles previous descriptions of Brucella, since it has been reported that an absolute majority of brucellae are initially killed but the surviving bacteria start to replicate and eventually show net replication despite the initial killing (51). Likewise, we believe that our findings are compatible with the hypothesis that most of the FSC043 bacteria are killed or contained within the phagosome but a small majority are able to escape from the phagosome and then start to replicate, and this would explain the limited systemic spread that the strain demonstrates (10).

Our data on FSC043 improves our understanding regarding the prerequisites for the high virulence of SCHU S4. Although the partial deletions of the fupA and fupB genes appear to be the most important reason for the attenuation of LVS (5), the complementation of FSC043 with the intact fupA and fupB genes or pdpE still resulted in an essentially avirulent strain. In contrast, complementation with pdpC and pdpE resulted in a dramatic increase in virulence: the LD50 was >100,000-fold lower than for FSC043. The combined complementation with both gene constructs led, however, to even higher virulence than did the pdpC-pdpE construct alone. This implies that the phagosomal escape of F. tularensis is essential for any virulence, since FSC043 has an LD50 of >108 CFU, and this was not markedly changed by complementation with the fupA-fupB construct. In contrast, complementation with the pdpC-pdpE construct leads to a phenotype that is characterized by phagosomal escape and rapid intracellular replication, like SCHU S4, and concomitantly, high virulence. However, when phagosomal escape occurs, the role of fupA becomes critical for the extreme virulence exhibited by SCHU S4, as evidenced by the even higher virulence of the mutant complemented with both constructs than the one complemented with the pdpC-pdpE construct only. Since the fupA mutant showed normal escape, our findings also demonstrate that the role of FupA is unrelated to phagosomal escape. Presumably, the very important role of FupA for the attenuation of LVS and full complementation of FSC043 is solely related to its critical function for iron utilization (4).

It is believed that escape of F. tularensis strains from the phagosome followed by intracellular replication is a crucial prerequisite to confer protective immunity on mammals (2). As shown here, the FSC043 strain is capable of minimal intracellular replication, in agreement with previous findings (10). We hypothesize that the finding of a mixed intracellular localization of strain FSC043 may be important for its overall phenotype, which includes very limited systemic spread in mice but still induction of intermediate protection. This is in contrast to the ΔiglB, ΔiglC, and ΔiglD mutants of SCHU S4, all of which are equally attenuated but confer minimal or no protection (10, 52). Presumably, their lack of immunogenicity is a result of the complete phagosomal confinement and thereby absence of systemic spread (10). Here, we observed that all of the mutants tested, FSC043, ΔpdpC, ΔpdpC ΔpdpE, ΔfupA, and ΔFTL0439, conferred significant protection against intradermal challenge with SCHU S4, and almost all mice survived until the experiment was terminated at day 28; however, there were marked differences in their protective efficacies against respiratory challenge. Regardless of the immunization dose, the ΔpdpC and the ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants did not confer any significant protection, whereas FSC043 and the ΔfupA mutant conferred intermediate protection, and in fact, some of the mice survived until the experiment was terminated. In contrast, the ΔFTL0439 mutant conferred highly significant protection and all immunized mice survived until the end of the experiment. Thus, the highly significant attenuation resulting from the deletion or truncation of pdpC results in mutants with limited protective abilities, presumably related to their limited intracellular replication and lack of efficient systemic spread after immunization (14). In contrast, the ΔFTL0439 mutation, identical to the one that provides the most significant contribution to the attenuation of LVS (5), leads to intermediate attenuation and confers efficacious vaccine properties. The data also indicate that the partial deletions of the fupA and fupB genes present in the ΔFTL0439 mutant lead to more marked virulence than does deletion of the ΔfupA gene alone and that the former mutant shows somewhat superior vaccine efficacy. Thus, this implies that the N-terminal part of FupA that is expressed in FSC043 and LVS affects virulence and protective efficacy. FSC043 showed superior protective efficacy compared to the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, although all three strains showed the same aberrant phagosomal escape and very limited intracellular replication. A notable observation was the abnormal expression of many genes and even more proteins in FSC043, and this may explain its superior immunogenicity. The reason for this aberrant protein expression is unknown, and it will be important to determine if it is in any way indirectly related to the impaired expression of fupA fupB and/or pdpC and pdpE. However, since strain SCHU S4 was derived from the original SCHU isolate before 1951 (53), it is possible that the mutations present in FSC043 may have occurred more than 60 years ago; therefore, the identified aberrant protein expression may be the result of adaptation after many passages in vitro. Overall, the data regarding the protection conferred by the mutants demonstrate that there is no absolute correlation between their ability to disseminate and to confer protection and, in addition, that some bacterial determinants should be preserved in order for the corresponding mutants to provide efficacious protection.

Collectively, our data demonstrate that the spontaneous FSC043 mutant exhibits a unique phenotype, as evidenced by variable phagosomal escape, minimal intramacrophage growth and cytotoxic effects, and lack of virulence, despite being derived from the highly virulent SCHU S4. We infer from our data that the most important reason for these phenotypes is the expression of a truncated form of PdpC, and the findings emphasize the essential role of phagosomal escape for expression of any virulence by F. tularensis. Furthermore, our study improves the understanding of the mechanisms leading to the very high virulence of SCHU S4.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants 2006-2877, 2006-3426, 2009-5026, and 2013-4581 from the Swedish Research Council and a grant from the Medical Faculty, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. The work was performed in part at the Umeå Centre for Microbial Research (UCMR). The National Research Council of Canada funded the animal studies, and NIH grant AI064183 funded the proteomics work.

We are thankful to Konstantin Kadzhaev for help with constructing the ΔpdpC and ΔpdpC ΔpdpE mutants, Athar Alam for performing Western blot analysis, Jeanette Bröms for constructive comments, and Mattias Landfors for help with statistical analysis of the microarray data.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Sjöstedt A. 2007. Tularemia: history, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1105:1–29. 10.1196/annals.1409.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conlan JW. 2011. Tularemia vaccines: recent developments and remaining hurdles. Future Microbiol. 6:391–405. 10.2217/fmb.11.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broekhuijsen M, Larsson P, Johansson A, Bystrom M, Eriksson U, Larsson E, Prior RG, Sjöstedt A, Titball RW, Forsman M. 2003. Genome-wide DNA microarray analysis of Francisella tularensis strains demonstrates extensive genetic conservation within the species but identifies regions that are unique to the highly virulent F. tularensis subsp. tularensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2924–2931. 10.1128/JCM.41.7.2924-2931.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindgren H, Honn M, Golovlev I, Kadzhaev K, Conlan W, Sjöstedt A. 2009. The 58-kilodalton major virulence factor of Francisella tularensis is required for efficient utilization of iron. Infect. Immun. 77:4429–4436. 10.1128/IAI.00702-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salomonsson E, Kuoppa K, Forslund AL, Zingmark C, Golovliov I, Sjöstedt A, Noppa L, Forsberg A. 2009. Reintroduction of two deleted virulence loci restores full virulence to the live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis. Infect. Immun. 77:3424–3431. 10.1128/IAI.00196-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke DS. 1977. Immunization against tularemia: analysis of the effectiveness of live Francisella tularensis vaccine in prevention of laboratory-acquired tularemia. J. Infect. Dis. 135:55–60. 10.1093/infdis/135.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eigelsbach HT, Down CM. 1961. Prophylactic effectiveness of live and killed tularemia vaccines. I. Production of vaccine and evaluation in the white mouse and guinea pig. J. Immunol. 87:415–425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saslaw S, Eigelsbach HT, Prior JA, Wilson HE, Carhart S. 1961. Tularemia vaccine study. II. Respiratory challenge. Arch. Intern. Med. 107:702–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornick RB, Eigelsbach HT. 1966. Aerogenic immunization of man with live tularemia vaccine. Bacteriol. Rev. 30:532–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twine S, Bystrom M, Chen W, Forsman M, Golovliov I, Johansson A, Kelly J, Lindgren H, Svensson K, Zingmark C, Conlan W, Sjöstedt A. 2005. A mutant of Francisella tularensis strain SCHU S4 lacking the ability to express a 58-kilodalton protein is attenuated for virulence and is an effective live vaccine. Infect. Immun. 73:8345–8352. 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8345-8352.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twine S, Shen H, Harris G, Chen W, Sjöstedt A, Ryden P, Conlan W. 2012. BALB/c mice, but not C57BL/6 mice immunized with a DeltaclpB mutant of Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis are protected against respiratory challenge with wild-type bacteria: association of protection with post-vaccination and post-challenge immune responses. Vaccine 30:3634–3645. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straskova A, Cerveny L, Spidlova P, Dankova V, Belcic D, Santic M, Stulik J. 2012. Deletion of IglH in virulent Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica FSC200 strain results in attenuation and provides protection against the challenge with the parental strain. Microbes Infect. 14:177–187. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryden P, Twine S, Shen H, Harris G, Chen W, Sjöstedt A, Conlan W. 2013. Correlates of protection following vaccination of mice with gene deletion mutants of Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis strain, SCHU S4 that elicit varying degrees of immunity to systemic and respiratory challenge with wild-type bacteria. Mol. Immunol. 54:58–67. 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long ME, Lindemann SR, Rasmussen JA, Jones BD, Allen LA. 2013. Disruption of Francisella tularensis Schu S4 iglI, iglJ, and pdpC genes results in attenuation for growth in human macrophages and in vivo virulence in mice and reveals a unique phenotype for pdpC. Infect. Immun. 81:850–861. 10.1128/IAI.00822-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindemann SR, Peng K, Long ME, Hunt JR, Apicella MA, Monack DM, Allen LA, Jones BD. 2011. Francisella tularensis Schu S4 O-antigen and capsule biosynthesis gene mutants induce early cell death in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 79:581–594. 10.1128/IAI.00863-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai S, Mohapatra N, Schlesinger L, Gunn J. 2010. Regulation of Francisella tularensis virulence. Front. Microbiol. 1:144. 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horzempa J, O'Dee DM, Shanks RM, Nau GJ. 2010. Francisella tularensis DeltapyrF mutants show that replication in nonmacrophages is sufficient for pathogenesis in vivo. Infect. Immun. 78:2607–2619. 10.1128/IAI.00134-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahawar M, Kirimanjeswara GS, Metzger DW, Bakshi CS. 2009. Contribution of citrulline ureidase to Francisella tularensis strain Schu S4 pathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 191:4798–4806. 10.1128/JB.00212-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjödin A, Svensson K, Lindgren M, Forsman M, Larsson P. 2010. Whole-genome sequencing reveals distinct mutational patterns in closely related laboratory and naturally propagated Francisella tularensis strains. PLoS One 5:e11556. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bröms JE, Sjöstedt A, Lavander M. 2010. The role of the Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island in type VI secretion, intracellular survival, and modulation of host cell signaling. Front. Microbiol. 1:136. 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nano FE, Schmerk C. 2007. The Francisella pathogenicity island. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1105:122–137. 10.1196/annals.1409.000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai XH, Golovliov I, Sjöstedt A. 2001. Francisella tularensis induces cytopathogenicity and apoptosis in murine macrophages via a mechanism that requires intracellular bacterial multiplication. Infect. Immun. 69:4691–4694. 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4691-4694.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai X-H, Sjöstedt A. 2003. Delineation of the molecular mechanisms of Francisella tularensis-induced apoptosis in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 71:4642–4646. 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4642-4646.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Dixit VM, Monack DM. 2005. Innate immunity against Francisella tularensis is dependent on the ASC/caspase-1 axis. J. Exp. Med. 202:1043–1049. 10.1084/jem.20050977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickstrum JR, Bokhari SM, Fischer JL, Pinson DM, Yeh HW, Horvat RT, Parmely MJ. 2009. Francisella tularensis induces extensive caspase-3 activation and apoptotic cell death in the tissues of infected mice. Infect. Immun. 77:4827–4836. 10.1128/IAI.00246-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones JW, Broz P, Monack DM. 2011. Innate immune recognition of Francisella tularensis: activation of type-I interferons and the inflammasome. Front. Microbiol. 2:16. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bönquist L, Lindgren H, Golovliov I, Guina T, Sjöstedt A. 2008. MglA and Igl proteins contribute to the modulation of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 76:3502–3510. 10.1128/IAI.00226-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chong A, Wehrly TD, Nair V, Fischer ER, Barker JR, Klose KE, Celli J. 2008. The early phagosomal stage of Francisella tularensis determines optimal phagosomal escape and Francisella pathogenicity island protein expression. Infect. Immun. 76:5488–5499. 10.1128/IAI.00682-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bruin OM, Ludu JS, Nano FE. 2007. The Francisella pathogenicity island protein IglA localizes to the bacterial cytoplasm and is needed for intracellular growth. BMC Microbiol. 7:1. 10.1186/1471-2180-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golovliov I, Baranov V, Krocova Z, Kovarova H, Sjöstedt A. 2003. An attenuated strain of the facultative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis can escape the phagosome of monocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 71:5940–5950. 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5940-5950.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santic M, Molmeret M, Abu Kwaik Y. 2005. Modulation of biogenesis of the Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida-containing phagosome in quiescent human macrophages and its maturation into a phagolysosome upon activation by IFN-gamma. Cell Microbiol. 7:957–967. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bröms JE, Lavander M, Meyer L, Sjöstedt A. 2011. IglG and IglI of the Francisella pathogenicity island are important virulence determinants of Francisella tularensis LVS. Infect. Immun. 79:3683–3696. 10.1128/IAI.01344-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bröms JE, Lavander M, Sjöstedt A. 2009. A conserved alpha-helix essential for a type VI secretion-like system of Francisella tularensis. J. Bacteriol. 191:2431–2446. 10.1128/JB.01759-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bröms JE, Meyer L, Lavander M, Larsson P, Sjöstedt A. 2012. DotU and VgrG, core components of type VI secretion systems, are essential for Francisella tularensis LVS pathogenicity. PLoS One 7:e34639. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindgren M, Bröms JE, Meyer L, Golovliov I, Sjöstedt A. 2013. The Francisella tularensis LVS DeltapdpC mutant exhibits a unique phenotype during intracellular infection. BMC Microbiol. 13:20. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindgren M, Eneslatt K, Bröms JE, Sjöstedt A. 2013. Importance of PdpC, IglC, IglI, and IglG for modulation of a host cell death pathway induced by Francisella tularensis. Infect. Immun. 81:2076–2084. 10.1128/IAI.00275-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uda A, Sekizuka T, Tanabayashi K, Fujita O, Kuroda M, Hotta A, Sugiura N, Sharma N, Morikawa S, Yamada A. 2014. Role of pathogenicity determinant protein C (PdpC) in determining the virulence of the Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis SCHU. PLoS One 9:e89075. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Bruin OM, Duplantis BN, Ludu JS, Hare RF, Nix EB, Schmerk CL, Robb CS, Boraston AB, Hueffer K, Nano FE. 2011. The biochemical properties of the Francisella Pathogenicity Island (FPI)-encoded proteins, IglA, IglB, IglC, PdpB and DotU, suggest roles in type VI secretion. Microbiology 157:3483–3491. 10.1099/mic.0.052308-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golovliov I, Sjöstedt A, Mokrievich A, Pavlov V. 2003. A method for allelic replacement in Francisella tularensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 222:273–280. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00313-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryden P, Andersson H, Landfors M, Naslund L, Hartmanova B, Noppa L, Sjöstedt A. 2006. Evaluation of microarray data normalization procedures using spike-in experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 7:300. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin DM, Peng V, Ngai J, Speed TP. 2002. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e15. 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lönnstedt I, Speed T. 2002. Replicated microarray data. Statistica Sinica 12:31–46 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramagli LS. 1999. Quantifying protein in 2-D PAGE solubilization buffers. Methods Mol. Biol. 112:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haqqani AS, Kelly JF, Stanimirovic DB. 2008. Quantitative protein profiling by mass spectrometry using isotope-coded affinity tags. Methods Mol. Biol. 439:225–240. 10.1007/978-1-59745-188-8_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palagi PM, Walther D, Quadroni M, Catherinet S, Burgess J, Zimmermann-Ivol CG, Sanchez JC, Binz PA, Hochstrasser DF, Appel RD. 2005. MSight: an image analysis software for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Proteomics 5:2381–2384. 10.1002/pmic.200401244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guina T, Radulovic D, Bahrami AJ, Bolton DL, Rohmer L, Jones-Isaac KA, Chen J, Gallagher LA, Gallis B, Ryu S, Taylor GK, Brittnacher MJ, Manoil C, Goodlett DR. 2007. MglA regulates Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida (Francisella novicida) response to starvation and oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 189:6580–6586. 10.1128/JB.00809-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. 2004. Virulent and avirulent strains of Francisella tularensis prevent acidification and maturation of their phagosomes and escape into the cytoplasm in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 72:3204–3217. 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3204-3217.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Checroun C, Wehrly TD, Fischer ER, Hayes SF, Celli J. 2006. Autophagy-mediated reentry of Francisella tularensis into the endocytic compartment after cytoplasmic replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:14578–14583. 10.1073/pnas.0601838103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards JA, Rockx-Brouwer D, Nair V, Celli J. 2010. Restricted cytosolic growth of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis by IFN-gamma activation of macrophages. Microbiology 156:327–339. 10.1099/mic.0.031716-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]