Abstract

Type VI secretion systems (T6SSs) are involved in the pathogenicity of several Gram-negative bacteria. The VgrG protein, a core component and effector of T6SS, has been demonstrated to perform diverse functions. The N-terminal domain of VgrG protein is a homologue of tail fiber protein gp27 of phage T4, which performs a receptor binding function and determines the host specificity. Based on sequence analysis, we found that two putative T6SS loci exist in the genome of the avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) strain TW-XM. To assess the contribution of these two T6SSs to TW-XM pathogenesis, the crucial clpV clusters of these two T6SS loci and their vgrG genes were deleted to generate a series of mutants. Consequently, T6SS1-associated mutants presented diminished adherence to and invasion of several host cell lines cultured in vitro, decreased pathogenicity in duck and mouse infection models in vivo, and decreased biofilm formation and bacterial competitive advantage. In contrast, T6SS2-associated mutants presented a significant decrease only in the adherence to and invasion of mouse brain microvascular endothelial cell (BMEC) line bEnd.3 and brain tissue of the duck infection model. These results suggested that T6SS1 was involved in the proliferation of APEC in systemic infection, whereas VgrG-T6SS2 was responsible only for cerebral infection. Further study demonstrated that VgrG-T6SS2 was able to bind to the surface of bEnd.3 cells, whereas it did not bind to DF-1 (chicken embryo fibroblast) cells, which further proved the interaction of VgrG-T6SS2 with the surface of BMECs.

INTRODUCTION

Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) is a group of strains that have been implicated in manifold infections in humans and animals, including urinary tract infections, newborn meningitis, abdominal sepsis, and septicemia (1). Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC), an important ExPEC subgroup, causes respiratory or systemic infections and large financial losses in the poultry industry worldwide (2). APEC shares important virulence traits with uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), neonatal meningitis Escherichia coli (NMEC), and septicemia-associated E. coli (SEPEC), representing a potential zoonotic risk (3–5). Recently, it has been confirmed that some closely related clones of APEC and NMEC were able to cause extraintestinal infections in both chicken and rat models of human neonatal meningitis, suggesting that there is no host specificity for these clonal types of isolates (6, 7).

Today, one important but overlooked bacterial virulence trait is the delivery of proteins and toxins to host cells through specialized secretion systems (8–10). The type VI secretion system (T6SS) has been described for several bacterial species (8, 11, 12), including APEC (13, 14), and represents a new paradigm of protein secretion (11). de Pace et al. (14) found that the mutants of T6SS core genes (clpV and hcp) of APEC strain SEPT362 displayed decreased adherence and actin rearrangement on epithelial cells. A similar result was revealed by research on the Hcp mutant of the neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC) strain RS218 (15). However, the means by which T6SSs contribute to virulence remain unknown, and the mechanisms warrant further investigation.

The minimal machinery necessary for the functionality of T6SSs has been revealed, and it is assembled by at least 13 core proteins called “core components” (10, 16). Two T6SS-associated effectors, hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp) and valine-glycine repeat G (VgrG), function as exported chaperones of effectors (12, 17) and have similar structures of the (gp27)3-(gp5)3 spike complex (18, 19). The tail fiber protein can bind to the receptor of sensitive bacteria specifically, which confers on bacteriophage a high degree of host specificity, and this mechanism may also be applied to the host cell recognition of the gp27 domain of VgrG (20, 21). Some VgrG proteins have different C-terminal extensions, including certain domains with different activities. For example, VgrG from Pseudomonas aeruginosa carries a zinc-metalloprotease domain, while VgrG1 from Vibrio cholerae contains repeats in structural toxin A (RtxA) (22).

In this study, the results indicated that the two functional T6SSs are encoded in the genome of meningitis-causing APEC K1 strain TW-XM. T6SS1 is required for interaction with eukaryotic as well as prokaryotic host cells and not only is involved in the pathogenesis of APEC systemic infection but also contributes to biofilm formation and bacterial competition. However, T6SS2 is responsible only for cerebral infection. The comprehensive analysis revealed that T6SS1 and T6SS2 of APEC may function in different pathogenic pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The APEC isolate TW-XM (O2:K1), belonging to the phylogenetic E. coli reference (ECOR) group B2, was isolated from the brain of a duck which had septicemia and neurological symptoms. The strain was also found to cause serious meningitis in the neonatal rat model of human disease. All strains (Table 1) were grown aerobically in LB medium or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) at 37°C. When necessary, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 50 μg/ml kanamycin (Km).

TABLE 1.

Summary of bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic or functiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| TW-XM | Virulent strain of APEC isolated from brain of a duck that died from septicemia; Strr | Collected in our lab |

| ΔVgrG-T6SS1 | Deletion mutant of vgrG-T6SS1 with TW-XM background | This study |

| KΔVgrG-T6SS1 | ΔVgrG-T6SS1 containing kanamycin resistance | This study |

| ΔVgrG-T6SS2 | Deletion mutant of vgrG-T6SS2 with TW-XM background | This study |

| ΔVgrG-T6SS1–2 | Deletion mutant of vgrG-T6SS1 and vgrG-T6SS2 with TW-XM background | This study |

| CΔVgrG-T6SS1 | APEC_XM ΔVgrG-T6SS1 with the vector pUC19-vgrG-T6SS1C, Ampr | This study |

| CΔVgrG-T6SS2 | APEC_XM ΔVgrG-T6SS2 with the vector pUC19-vgrG-T6SS1C, Ampr | This study |

| PΔVgrG-T6SS1 | APEC_XM ΔVgrG-T6SS1 with the vector pUC19, Ampr | This study |

| PΔVgrG-T6SS2 | APEC_XM ΔVgrG-T6SS2 with the vector pUC19, Ampr | This study |

| ΔT6SS1 | Deletion mutant of clpV-T6SS1 with TW-XM background | This study |

| KΔT6SS1 | ΔT6SS1 containing kanamycin resistance | This study |

| ΔT6SS2 | Deletion mutant of clpV-T6SS2 with TW-XM background | This study |

| ΔTle4 | Deletion mutant of tle4 with TW-XM background | This study |

| ΔTle4Tli4 | Deletion mutant of tle4 tli4 with TW-XM background | This study |

| KΔTle4 | ΔTle4 containing kanamycin resistance | This study |

| PΔTle4 | APEC_XM ΔTle4 with the vector pUC19, Ampr | This study |

| CΔTle4 | APEC_XM ΔTle4 with the vector pUC19-tle4–T6SS1C, Ampr | This study |

| MG1655 | Strain induced by nalidixic acid resistance | This study |

| DH5α | Cloning host for maintaining the recombinant plasmids | Invitrogen |

| BL21 | Host for expressing the recombinant proteins | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET28a(+) | Expression vector, Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pET28a-hcp-T6SS1 | pET28a inserted in frame with the hcp-T6SS1 gene for expressing Hcp-T6SS1 | This study |

| pET28a-hcp-T6SS2 | pET28a inserted in frame with the hcp-T6SS2 gene for expressing Hcp-T6SS2 | This study |

| pET28a-vgrG-T6SS1 | pET28a inserted in frame with the vgrG-T6SS1 gene for expressing VgrG-T6SS1 | This study |

| pET28a-vgrG-T6SS2 | pET28a inserted in frame with the vgrG-T6SS2 gene for expressing VgrG-T6SS2 | This study |

| pMD 19-T vector | TA cloning vector | TaKaRa |

| pUC19 | E. coli shuttle vector; Ampr | TaKaRa |

| pUC19-vgrG-T6SS1C | pUC19 containing the promoter followed by the full-length vgrG-T6SS1 ORF | This study |

| pUC19-vgrG-T6SS2C | pUC19 containing the promoter followed by the full-length vgrG-T6SS2 ORF | This study |

| pUC19-tle4-T6SS1C | pUC19 containing the promoter followed by the full-length tle4 ORF | This study |

| pKD46 | λ red recombinase expression plasmid | 24 |

| pKD4 | pANTSγ derivative containing FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance | 24 |

| pCP20 | TS replication and thermal induction of FLP synthesis | 24 |

ORF, open reading frame; FRT, FLP recombination target; TS, temperature sensitive.

Animals.

Seven-day-old ducks, 5-week-old male ICR mice, and New Zealand White rabbits were purchased from the Comparative Medicine Center of Yangzhou University and housed in filter-top cages with free access to food and water under a 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycle in accordance with the guidelines of Beijing Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics. All animal experiments were approved by the Department of Science and Technology of Jiangsu Province. The license number was SYXK (SU) 2010-0005.

Purification of recombinant protein and preparation of polyclonal antibody.

A total of four genes were cloned in frame into the pET28a vector; the protein expression and purification were carried out as described previously (23). The supernatant of lysate was purified by a HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The New Zealand White rabbits were used for producing polyclonal antibody (anti-Hcp-T6SS1, anti-Hcp [XmtA]-T6SS2, anti-VgrG-T6SS1, and anti-VgrG-T6SS2). The purified fusion proteins emulsified with adjuvant ISA 206 (Seppic, France) were injected into the back of the rabbits once every 2 weeks.

Construction of isogenic mutants and complementation of mutants.

Disruptions of the vgrG genes, clpV genes, tle4 gene, and tli4 gene in the chromosome of strain TW-XM were achieved by using λ red mutagenesis (24). For complementation of ΔVgrG-T6SS1, ΔVgrG-T6SS2, and ΔTle4, the coding sequences of genes plus their putative promoter regions were amplified from the TW-XM genome and independently cloned into pUC19 (25) using BamHI and HindIII restriction sites. All primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Isolation of bacterial secretory proteins and eukaryotic cytoplasmic proteins of host cells.

Bacteria (106 CFU) were added to wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate containing a monolayer (105 cells) of bEnd.3 or DF-1 cells (from Shanghai Fuxiang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) in 0.5 ml of serum-free medium. Plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere to allow full interaction between bacteria and cells. The monolayers were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the culture medium and washing PBS collected by the above steps were passed through 0.22-μm filters to remove bacterial cell contamination. Then, the secretory proteins were concentrated by using 10,000-molecular-weight-cutoff spin columns (Millipore). The quality of secretory proteins was verified by the absence of the cytosolic marker cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (Crp) (15). The monolayers were washed three times with PBS again, digested with trypsin, and disrupted by sterile deionized water to release cytoplasmic protein. The above fluids were also passed through 0.22-μm filters to remove the remnant of bacteria and cellular debris, and the resultant concentration of cytoplasmic proteins was similar to that from the above extraction. The quality of cytoplasmic proteins was verified by the presence of the eukaryotic cytosolic marker β-actin protein (26). The concentrations of the wild-type strain and mutant proteins were assessed using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein quantification kit (Pierce Protein Biology of Thermo Scientific). Fifty micrograms of protein was loaded into each lane for SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis. The Western affinity blotting assay was carried out as described previously (27), and all assays were repeated at least twice.

Biofilm formation assay and SEM.

The biofilm assay (1% crystal violet method) was performed as previously described (28, 29) in 96-well plates, and the A595 was recorded. Wells with sterile broth medium served as controls. All biofilm assays were run in triplicate. Scanning optical microscopy of biofilm stained by crystal violet was performed as previously described (30). The microtiter plate was air dried at 37°C for 30 min, and the bacterial biofilms were observed under ×40 magnification. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed as previously described (29). The biofilms on coverslips were washed three times with PBS and fixed by using 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Observations were performed at 5 kV with a scanning electron microscope (model S800; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Bacterial competition experiments.

For bacterial competition experiments, both strains were mixed at a 1:1 ratio (donor to recipient) in triplicate after the cultures were normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 (31). This mixture was then spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane on a 1.5% (wt/vol) agar LB plate. Competition mixtures were incubated for 5 h at 37°C. Bacterial spots were harvested, and the CFU per milliliter of the surviving donor and recipient were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions on selective medium plates. Wild-type TW-XM and ΔTle4Tli4 were selected on LB plates with streptomycin (50 μg/ml); MG1655 was selected by nalidixic acid (100 μg/ml); ΔT6SS1 (Kanr), ΔVgrG-T6SS1 (Kanr), and ΔTle4 (Kanr) were selected on kanamycin (50-μg/ml) plates; CΔVgrG-T6SS1, CΔTle4, PΔVgrG-T6SS1, and PΔTle4 were selected on ampicillin (100-μg/ml) plates.

Assessment of pathogenicity by LD50 and survival curve.

The virulence of each strain was evaluated in duck and mouse models by 50% lethal dose (LD50) as described previously (25). Eight infection groups were intramuscularly injected in the pelma with 10-fold serially diluted suspensions containing 103 to 107 CFU of bacteria in sterile PBS. The blank control group was injected with sterile PBS. The ducks were observed for 7 days until survival rates were steady. The LD50 of each strain was also tested with a mouse model. LD50 results were calculated by using the Reed-Muench method. Furthermore, 107 CFU/ml of each strain was injected into the pelma muscles of ducks (16 ducks per strain) to obtain the survival curve. The groups were observed throughout a 7-day period, and survival condition was recorded every 12 h.

Proliferation capacity of APEC in animal infection model.

Each group consisted of 15 ducks, and the dose of intramuscular injection in the pelma was 5 × 106 CFU/duck (∼10× LD50). At 24 h postinfection, the diseased ducks were selected for euthanization and dissection. Bacteria were isolated from the blood, spleens, lungs, and brain homogenates by plating 10-fold serial dilutions on MacConkey agar. The number of bacteria colonizing the organs of the ducks during systemic infection was obtained.

Adherence and invasion assays in bEnd.3 and DF-1 cells.

According to the results of analyzing bacterial proliferation capacity in vivo, we used chicken embryo fibroblast cells (DF-1) as the model of system infection, while mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) (bEnd.3) were used as the model of meningitis. E. coli invasion assays were performed as described previously (32, 33). Bacteria were added to monolayers at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 bacteria/cells. The invasion frequency was calculated by dividing the number of invaded bacteria by the CFU of the original inoculum. Results were presented as the relative invasion frequency compared with the invasion frequency of wild-type TW-XM, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. The assay was performed in sextuplicate. Adherence assays were performed similarly to the invasion assay, except that the gentamicin treatment step was omitted.

qRT-PCR.

The bacteria were grown to the logarithmic phase, and RNA was isolated by using the E.Z.N.A. bacterial RNA isolation kit (Omega, Beijing, China). Contaminating DNA was removed from the samples with RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and cDNA synthesis was performed by using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to determine the transcription levels of the virulence factors using SYBR premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and gene-specific primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and the data were normalized to the housekeeping gene dnaE transcript (25). The relative fold change was calculated by using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method (34).

Assessment of VgrG protein binding to target cells.

To analyze the cell binding competence of VgrG proteins, both indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot analysis were carried out using antibody against His-VgrG proteins. DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells (4 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well microplate [BD Biosciences]) were incubated with 12 μg/ml endotoxin-free His-VgrG proteins for 12 h at 37°C. The monolayers were then washed three times with PBS and blocked with 10% skim milk at 37°C for 1 h or used to extract protein samples for Western blot analysis. VgrG-ELISA was performed as reported previously (35), and blots were probed with a mouse anti-His antibody (1:2,000; Beyotime). A Western affinity blotting assay was carried out as described previously (27). Samples were transferred electrophoretically onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and the detection of bound immunoglobulin was achieved using mouse anti-His antibody and horseradish peroxidase–goat anti-mouse serum.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The difference between mean values among groups was first evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and then by pairwise comparison of the mean values between the two groups, followed by Tukey's Student rank test. The comparisons between two groups of abnormal distribution were evaluated by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test, and the duck survival data were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier estimator method. Differences with a P value of <0.05 were considered significant, and a P value of <0.01 was considered greatly significant.

RESULTS

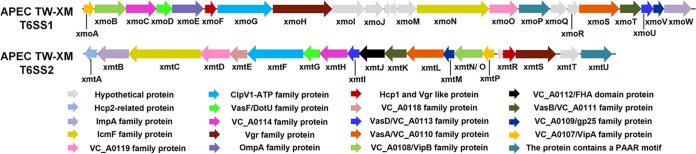

Two T6SS gene clusters exist in the genome of meningitis-causing APEC K1 strain TW-XM.

The orthologous T6SS clusters widely exist in the genomes of various E. coli pathotypes and are divided into three types based on the homology and structural analysis of core gene clusters (see Table S3 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (36). Here, genome sequence analysis showed that two gene clusters (GenBank accession numbers KF678349 and KF678350) encoding putative T6SSs exist in the genome of APEC K1 strain TW-XM, named the T6SS1 and T6SS2 clusters (Fig. 1). The phylogenetic analyses of VgrG proteins suggested that the T6SS2 clusters encoded in E. coli genomes could be divided into the intestinal pathogenic group and the extraintestinal pathogenic group (see Fig. S1A). Therefore, we speculated that these two T6SS2 groups may perform different functions in intestinal pathogenic and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), respectively. Furthermore, the Hcp (XmtA), VgrG, and PAAR proteins of T6SS2 in ExPEC are significantly different from those of intestinal pathogenic E. coli (see Fig. S1B), which also suggests that T6SS2 may perform specific functions in ExPEC. The information above provides us an opportunity to research the functional mechanisms of T6SS1 and T6SS2.

FIG 1.

Schematic diagram of the genetic organization of TW-XM T6SS gene clusters. Genes encoding conserved domain proteins are represented by the same colors. Silver arrows refer to other genes included in the T6SS loci that were not identified as part of the conserved core described by Boyer et al. (57). The direction of the arrows indicates the direction of transcription. The color keys for the functional classes of genes in the T6SS loci are shown at the bottom. The database of Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins was obtained from the NCBI.

Identification of functional T6SS1 and T6SS2.

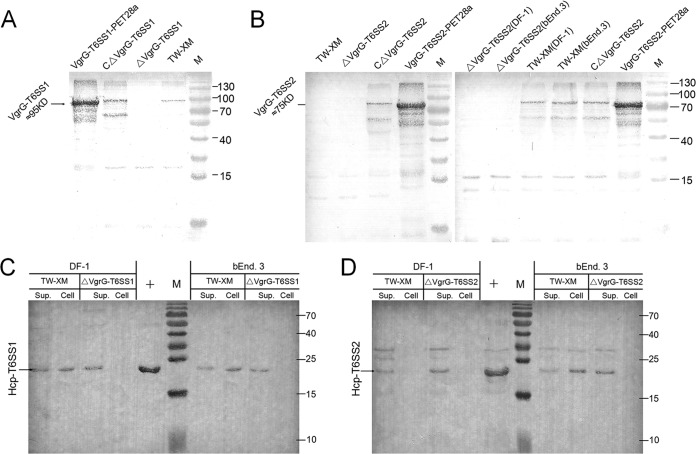

The quality inspection of protein samples was performed by Western blotting with Crp or β-actin antibodies (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The purified proteins of VgrG and Hcp were used as positive controls (see Fig. S3). As shown in Fig. 2A, incubation with anti-VgrG-T6SS1 led to the detection of protein bands of the expected size for VgrG-T6SS1 in the total lysate of the wild-type and complementation strains but not in that of mutant strain ΔVgrG-T6SS1. Surprisingly, VgrG-T6SS2 proteins were detected only in the lysates of complementation strains, not in ΔVgrG-T6SS2 and TW-XM (Fig. 2B). This phenomenon might be due to the activation of some T6SS requiring bacterial endocytosis by host cells (22, 37).

FIG 2.

Expression levels of VgrGs and Hcps in different strains were studied by immunoblotting. The quality inspection of protein samples was demonstrated in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. (A) VgrG-T6SS1 was not detected in the lysate from mutant strain ΔVgrG-T6SS1. The expression of vgrG-T6SS1 was demonstrated by Western blotting with VgrG-T6SS1 antibody using the lysates of wild-type, ΔVgrG-T6SS1, and CΔVgrG-T6SS1 strains cultured in DMEM. The recombinant VgrG-T6SS1 was used as a positive control. (B) The expression of vgrG-T6SS2 must be activated by host cells. Data are from Western blotting with VgrG-T6SS2 antibody using the lysates of wild-type, ΔVgrG-T6SS2, and CΔVgrG-T6SS2 strains cultured in DMEM and coincubated with DF-1 or bEnd.3 cells. The recombinant VgrG-T6SS2 was used as a positive control. (C and D) Lanes Sup., supernatants from wild-type, ΔVgrG-T6SS1, and ΔVgrG-T6SS2 strains coincubated with DF-1 or bEnd.3 cells; lanes Cell, cytosol of DF-1 or bEnd.3 cells coincubated with wild-type, ΔVgrG-T6SS1, and ΔVgrG-T6SS2 strains. (C) Hcp-T6SS1 is undetected in cytosol of DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells coincubated with mutant strain ΔVgrG-T6SS1. The result was demonstrated by Western blotting with Hcp-T6SS1 antibody. (D) Hcp-T6SS2 is undetected in cytosol of DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells coincubated with mutant strain ΔVgrG-T6SS2. The result was demonstrated by Western blotting with Hcp-T6SS2 antibody. Lanes M, protein molecular mass markers (numbers at right in kDa).

Hcp family proteins can be secreted via a T6SS-dependent pathway (38–40) and were found not only in culture supernatants but also in the cytosol and membrane of human epithelial cells (26). The Hcps could also be detected in the culture supernatants (incubation with host cells) by immunoblotting using anti-Hcp serum (Fig. 2C and D) in this study, which suggested that T6SS machinery had been assembled successfully. As shown in Fig. 2C, Hcp-T6SS1 was detected in all samples of TW-XM and culture supernatants of ΔVgrG-T6SS1 but was not found in the cytoplasm of DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells infected by ΔVgrG-T6SS1. A similar result was obtained in studies of the Hcp-T6SS2 protein (Fig. 2D). These results indicated that the inactivation of VgrG proteins did not destroy the secretion tube of T6SS but led to a defect in export of effectors into host cells. These results above indicated that the T6SS1 and T6SS2 loci in the TW-XM strain encode two functional T6SSs.

T6SS1 contributes to biofilm formation.

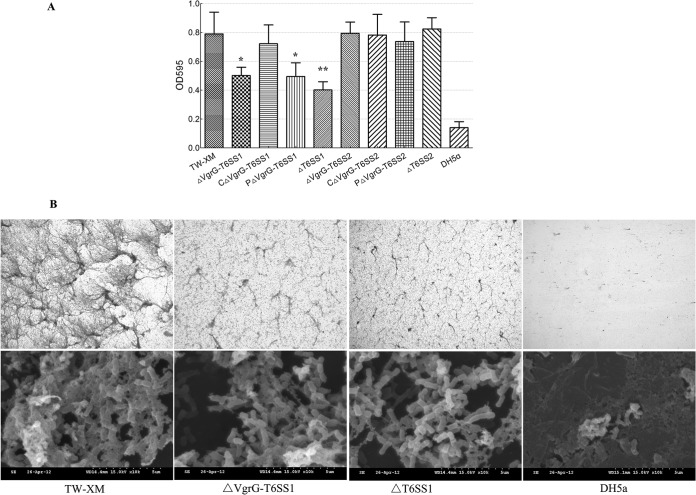

To examine whether the T6SS was involved in biofilm formation or not, wild-type and mutant strains were tested for their ability to form biofilms on polystyrene surfaces as previously described (41, 42). The growth rates of T6SS-associated mutants were similar to those of the wild-type strain (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The biofilm formation ability of T6SS1-associated mutants in LB medium supplemented with fibrinogen was significantly decreased (>45%) compared with that of the wild-type strain TW-XM (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S5). Although the biofilm formation ability did not reach the level of that of the wild-type strain, it was restored in the CΔVgrG-T6SS1 strain (Fig. 3A). Since most virulence factors contributing to biofilm formation could induce intercellular autoaggregation (42), it could be inferred that the inactivation of T6SS1 reduced autoaggregation of APEC strain TW-XM. However, T6SS2 did not affect the biofilm formation.

FIG 3.

Biofilm assays of bacteria grown in LB supplemented with fibrinogen using 24-well microtiter plates. Biofilms were cultivated and quantified as described in the text. (A) Results shown are mean values of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. The error bars stand for standard deviations. The expression of vgrG-T6SS1 and the complete T6SS1 cluster led to significantly increased biofilm formation (P < 0.01). Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (B) Images of the biofilms of wild-type, ΔVgrG-T6SS1, and ΔT6SS1 strains. All strains were cultured in LB medium supplemented with 1% fibrinogen. Biofilm stained with crystal violet was observed by standard optical microscopy at a magnification of ×100. SEM was performed on biofilms formed on glass coverslips in the wells of 6-well microtiter plates, at a magnification of ×10,000.

T6SS1 is involved in bacterial competitions.

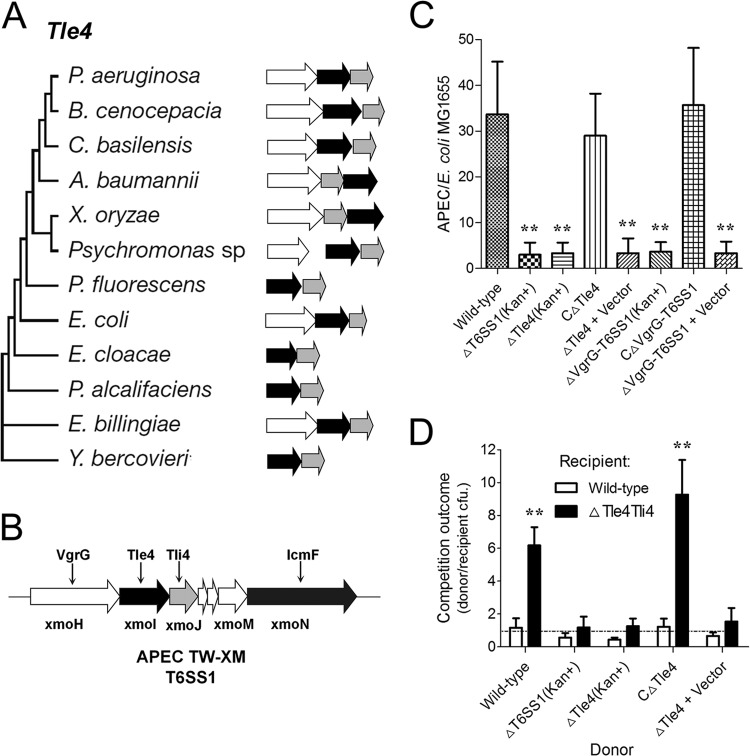

The analysis by Russell et al. (43) suggested that the type VI lipase effector 4 (Tle4) family proteins might have antibacterial activity, like any other phospholipases encoded in T6SS loci. The Tle4 proteins are united by a broad sporadic distribution pattern within Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 4A). The T6SS1 cluster of APEC also encodes a Tle4 family protein and its immunity protein Tli4 (Fig. 4B); the amino acid identity between XmoI and Tle4 (YP_542179, E. coli UTI89) was >90%. To explore the role of Tle4 and T6SS1 in interbacterial interactions more thoroughly, we measured their influence on competition outcomes between APEC and a model T6SS1 target, E. coli MG1655. Our results showed that both Tle4 and T6SS1 significantly contributed to the fitness of APEC in interpathotype competition under T6SS-conducive conditions (Fig. 4C). These findings show that Tle4 is a potent antibacterial effector delivered by T6SS1. Using cocultured antibiotic derivatives of this strain, we found that recipient strains lacking Tle4 and its putative immunity determinant exhibited significantly decreased fitness in competition with donor strains possessing Tle4 and functional T6SS1 and that expression of Tli4 in the recipient strain was necessary (Fig. 4D).

FIG 4.

Tle4 is an antibacterial effector delivered by T6SS1. (A) Evolutionary trees, genetic organization, and phylogenetic distribution of select Tle4 family members (43). Genes are colored by their predicted protein product (black, Tle4 proteins with a GXSXG catalytic motif; white, VgrG proteins; gray, putative periplasmic immunity protein Tli4). Branch lengths are not proportional to evolutionary distance. (B) tle4 and tli4 in T6SS1 cluster of APEC strain TW-XM. (C) Outcome of growth competitions between the indicated APEC strains and E. coli MG1655. Asterisks denote competitive outcomes significantly different from those obtained with the wild type (P < 0.01). (D) Growth competition assays between the indicated APEC donor and recipient strains. Experiments were initiated with equal CFU of donor and recipient bacteria as denoted by the dashed line. Asterisks indicate significant differences in competition outcome between recipient strains against the same donor strain. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Error bars indicate ±standard deviations.

T6SS1 and T6SS2 play an important role in pathogenicity of APEC in vivo.

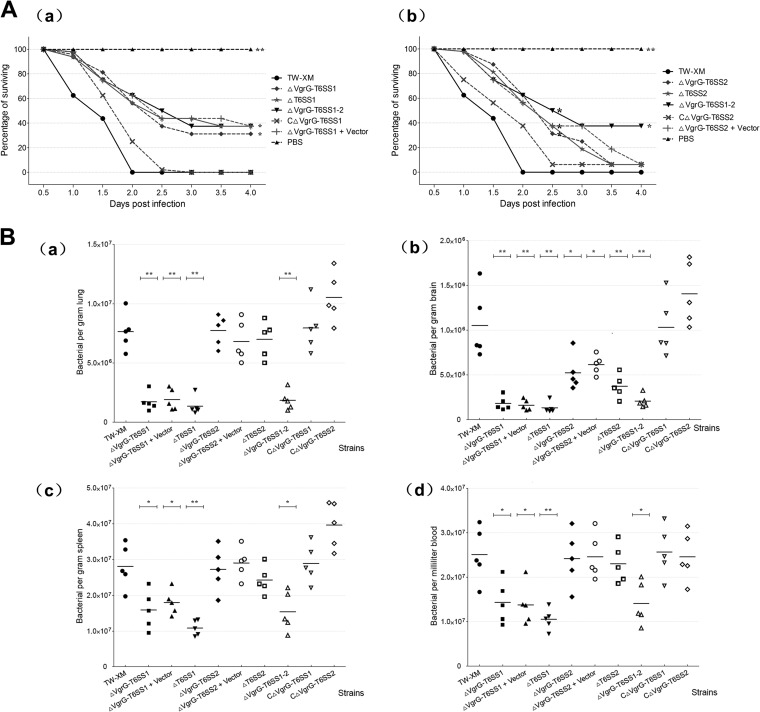

The virulence of the wild-type, mutant, and complementation strains was evaluated in the duck and mouse models. The virulence of T6SS1-associated mutants was significantly lower than that of the wild-type strain, and the complementation strain restored the virulence to the level of the wild-type strain. The LD50 values of the mutant strains ΔVgrG-T6SS1 and ΔT6SS1, wild-type strain, and complementation strain were 1.56 × 106, 2.38 × 106, 2.05 × 105, and 3.19 × 105 CFU/duck (see Table S4 in the supplemental material), respectively. A similar trend was observed for T6SS2-associated mutants, although the difference did not reach significance, whereas the survival time was significantly longer (Fig. 5A). Within 48 h, no duck infected with the wild-type strain survived, and only 37.5% of ducks remained alive in the CΔVgrG-T6SS2 group, whereas 62.5% and 60.0% of ducks infected with ΔVgrG-T6SS2 and ΔT6SS2, respectively, survived (Fig. 5A). The mouse model displayed a similar result (see Table S5).

FIG 5.

In vivo infection study. (A) Death curve of ducks infected with 107 CFU/ml (10× LD50) bacteria (16 ducks per strain tested). Survival data were analyzed by using the Kaplan-Meier estimator method. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (based on comparisons with strain TW-XM [wild type]). (B) Systemic infection experiments to determine the effect of T6SSs in vivo. Bacterial reisolations of TW-XM, T6SS-assosiated mutants, and complemented strains from lung (a), brain (b), spleen (c), and blood (d) at 24 h postinoculation were calculated by plate counting as described in Materials and Methods. The bars in the middle of columns indicate the average number of bacteria recovered from the organ for each group of animals. Statistical significance was determined by comparisons with strain TW-XM (wild type) (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Different pathogenic pathways of T6SS1 and T6SS2 in vivo.

To determine the effect of T6SSs in vivo, systemic infection experiments were performed according to the method described previously (25). As shown in Fig. 5B, the amount of bacteria in all of the four studied organs was significantly reduced in duck incubated with the T6SS1-associated mutants, compared with wild-type strain (P < 0.05). As for the strain T6SS2-associated mutants, no significant differences (P > 0.05) were presented statistically; those two mutants did not affect the bacterial accumulation in blood, lungs, and spleens (Fig. 5B); the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Only in the brain were the bacteria significantly reduced with the T6SS1-associated mutants compared with TW-XM (P < 0.05). These results suggested that T6SS1 was involved in the process of systemic infection by APEC strain TW-XM, whereas T6SS2 was linked only with cerebral infection.

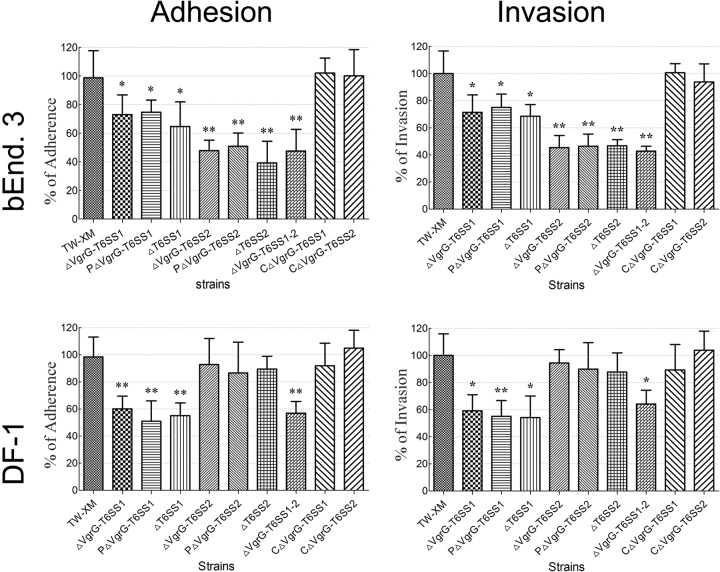

The T6SSs contribute to APEC's adherence to and invasion of DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells.

The capacities for adherence to and invasion of host cells were compared among the wild type, mutants, and complementation strains under the same conditions. The T6SS1-associated mutants were defective in binding to and invasion of DF-1 (P < 0.01) and bEnd.3 (P < 0.05) cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, the adherence and invasion abilities of T6SS2-associated mutants were not affected in DF-1 and showed a significant reduction only in bEnd.3 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6). These results indicated that T6SS1 is involved in APEC adherence to and invasion of a broad range of host cells. However, T6SS2 bound to and invaded only bEnd.3, which supported the hypothesis that T6SS2 plays an important role in the bacterial interaction with the blood-brain barrier.

FIG 6.

T6SSs are involved in TW-XM adhesion to and invasion of bEnd.3 and DF-1 cells. Effects of T6SSs on APEC adherence to and invasion of bEnd.3 and DF-l cells (MOI, 100). All assays were run in sextuplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on comparisons with strain TW-XM (wild type) (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05).

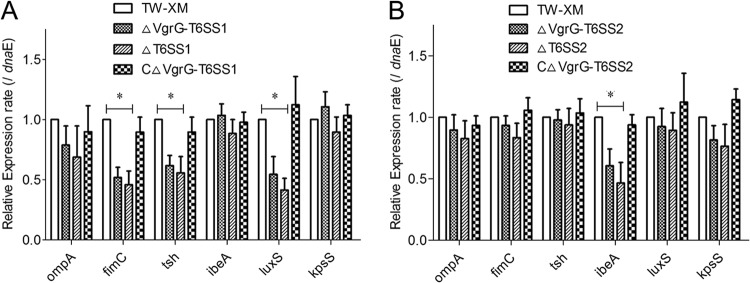

Inactivation of T6SSs downregulated the expression of virulence genes in APEC.

Several microbial determinants, such as OmpA, Ibe proteins, tsh, and type 1 fimbriae (fimC), contributed to the invasion phenotype (25, 44, 45). Thus, the expression profiling of virulence genes associated with invasion and adherence and of other known virulence genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR with the various strains in vitro. As shown in Fig. 7, the expression levels of the virulence factors fimC, tsh, and luxS were significantly decreased in T6SS1-associated mutants (P < 0.05). The expression levels of the virulence genes were restored in the complementation strain CΔVgrG-T6SS1. In contrast, only ibeA of T6SS2-associated mutants showed a significant decrease in gene expression levels compared with those in TW-XM (P < 0.05), and its level was restored in the complementation strain.

FIG 7.

Expression of virulence genes among different strains in vitro. Data were normalized to the housekeeping gene dnaE. Results are shown as relative expression ratios compared with expression in the parental strain TW-XM. Data from three independent assays are presented as the means ± standard deviations. (A) Expression levels of ompA, fimC, tsh, ibeA, luxS, and kpsS in strains TW-XM, ΔVgrG-T6SS1, ΔT6SS1, and CΔVgrG-T6SS1 were measured by qRT-PCR, and differences between TW-XM and mutants were statistically significant at a P value of <0.05. (B) Expression levels of ompA, fimC, tsh, ibeA, luxS, and kpsS in strains TW-XM, ΔVgrG-T6SS2, ΔT6SS2, and CΔVgrG-T6SS2 were measured by qRT-PCR, and the differences between TW-XM and mutants were statistically significant at a P value of <0.05.

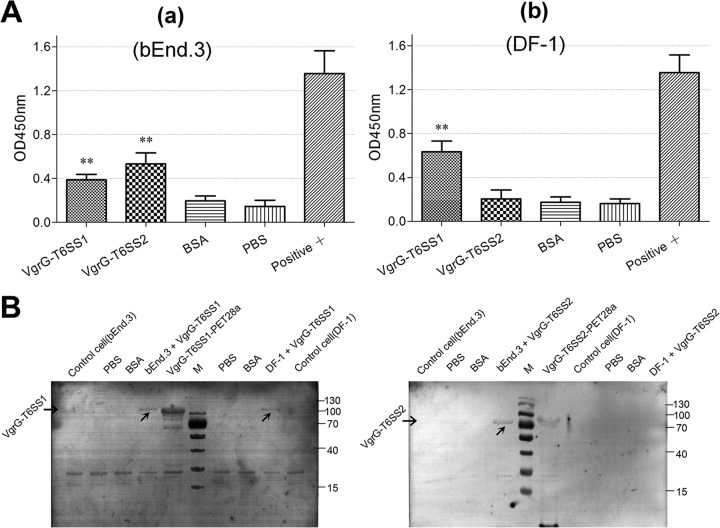

VgrG-T6SS2 protein specifically binds to BMECs (bEnd.3).

To analyze the binding competence of the VgrG-T6SS1 and VgrG-T6SS2 proteins for DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells, an indirect ELISA and a Western blotting assay were performed. These two VgrG proteins showed a positive reaction with bEnd.3 cells, whereas only VgrG-T6SS1 showed a strong binding with DF-1 cells (Fig. 8). The consistent results of ELISA (Fig. 8A) and Western blotting (Fig. 8B) indicated that the putative receptor of VgrG-T6SS2 may exist only on the BMEC surface, whereas the receptor of VgrG-T6SS1 may be widely distributed on the surfaces of various cell species.

FIG 8.

Assessment of VgrG protein binding to target cells. (A) ELISA of cell binding activity of the VgrG family proteins. A sample A450 value/negative controlling A450 value (S/N) of >2 was used as a positive standard. All assays were run in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on comparisons with negative control (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (a) bEnd.3 cell binding competence of VgrG-T6SS1 and VgrG-T6SS2 proteins. (b) DF-1 cell binding competence of VgrG-T6SS1 protein. (B) Binding of VgrG-T6SS1 and VgrG-T6SS2 on the surfaces of DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells observed by indirect Western blotting. BSA, bovine serum albumin. Lane M, molecular mass markers (numbers at right in kDa).

DISCUSSION

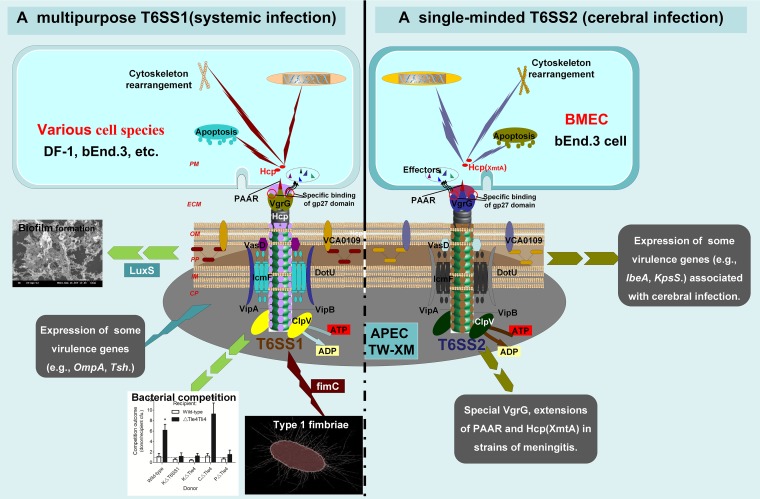

Type VI secretion systems are bacterial nanoinjection machines that transport macromolecules into neighboring prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells. The toxic effector molecules serve to outcompete other bacterial species (31, 46) or to alter host cells during pathogenesis (47–49). Many bacterial genomes encode more than one T6SS, and it is currently unclear whether they are functionally redundant or are both required for a specific niche (10, 50, 51). Here, we report the existence of two T6SS pathogenicity islands in APEC and demonstrate their functions. Especially, T6SS2 can be significantly divided into the intestinal pathogenic group and the extraintestinal pathogenic group. The special functions of T6SS2 in these two different groups still remain unknown.

The core genes and cluster structures of T6SS1 and T6SS2 in APEC have been described in our previous research (36). The functions of these T6SSs are shown by the secretion of the hallmark hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp) and valine-glycine repeat G (VgrG), whereas specific features of T6SS1 and T6SS2 are not the same. Different pathogenic pathways of T6SS1 and T6SS2 in APEC add a new element to the growing repertoire of T6SS regulation mechanisms and phenotypes.

Previous research showed that the (VgrG)3-PAAR complex punctures the host cell membrane and acts as a syringe for substrate injection (10, 18). The deletion of VgrGs led to the absence of Hcps in the cytosol and the membrane of DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells infected by bacteria. These results indicated that VgrG family proteins play a key role in puncturing the host cell membrane and exporting Hcps into the cytoplasm. However, no evidence indicated that Hcp-T6SS2 was transported into DF-1 cells. Our data had identified that VgrG-T6SS2 expression could be activated by DF-1 cells. However, the surface of DF-1 cells might not be bound by VgrG-T6SS2, a finding which seemed to suggest the key role of VgrGs in host cell recognition and explained why Hcp-T6SS2 was not transported into DF-1 cells.

There are some VgrG variants that harbor C-terminal effector domains, such as the RtxA actin cross-linking domain of V. cholerae VgrG1 and the actin-ADP-ribosylating domain of Aeromonas hydrophila VgrG1 (52). In comparison to the better-studied homologues, the C termini of VgrGs in APEC strain TW-XM are much smaller, and there is no bioinformatic indication that they could harbor active domains. Here, we found that these two VgrGs were not involved in apoptosis and cytoskeleton rearrangements of DF-1 and bEnd.3 (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), which indicated that they do not have functions similar to those of other known VgrG homologues. Currently, we are trying to understand the nature of this interaction and its biological functions.

In enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), the T6SS (sciZ) mutant causes a reduction in biofilm formation compared with the wild-type strain (38). In this study, T6SS1 also functioned in regulation of biofilm formation. The qRT-PCR analysis showed that inactivation of T6SS1 leads to decreased luxS expression. The luxS gene plays a vital role in biofilm formation, motility, and quorum sensing (53), which could be a major reason for the decreased biofilm formation in T6SS1-associated mutants. On another hand, this multipurpose T6SS1 is also involved in competition proliferation of bacteria. The Tle4 protein is a cytoplasmic effector that acts as a potent inhibitor of target cell proliferation (43), thus providing a pronounced fitness advantage for APEC donor cells. APEC utilizes a dedicated immunity protein, Tli4, to protect against endogenous and intercellularly transferred Tle4.

The T6SSs and their VgrGs were necessary for the full virulence of APEC strain TW-XM. The LD50s of T6SS1-associated mutants were increased compared with those of the wild-type strain in duck and mouse models. The survival time of the animal models infected with T6SS2-associated mutants was significantly longer than those for the wild-type or complementation strains. The inactivation of VgrG-T6SS1 and T6SS1 led to a decrease of fimC, tsh, and luxS expression, which might be responsible for the phenomenon of the mutant strains reducing invasion capacity (3). Previous research has shown that the inactivation of T6SS (Hcp) could result in reduced type 1 fimbria expression and decreased pathogenicity in APEC (14). In addition, the inactivation of VgrG-T6SS2 and T6SS2 leads only to decreased expression of ibeA, which plays a vital role in penetrating the blood-brain barrier. Reduced expression of adherence-associated gene ibeA mutants could be an important reason for the decreased proliferation capacity in the brain.

We found that these two T6SSs participated in different pathogenic processes. T6SS2 was specifically involved in cerebral infection of APEC. The invasion by T6SS2-associated mutants was significantly decreased in bEnd.3 cells, whereas it was unaltered in DF-1 cells. A similar finding that the E. coli K1 invasion of endothelial cells was specific to BMECs has been reported, and no invasion characteristics were observed for nonbrain endothelial cells (54). Additionally, the inactivation of VgrG-T6SS2 and T6SS2 resulted only in a significant decrease in the number of viable bacteria in brains compared with that of TW-XM, whereas the proliferation capacity for the other three tissues has no significant difference. Thus, it could be concluded that T6SS2 is involved in APEC invasion of BMECs, whereas it does not contribute to systemic infection. These results are also consistent with those from qRT-PCR analysis.

However, VgrG-T6SS1 and T6SS1 displayed no specific selectivity to target cells and were involved in the invasion of a variety of organs. The invasion capacity of T6SS1-associated mutants was significantly decreased in both DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells. The deletion of vgrG-T6SS1 and the T6SS1 core cluster resulted in significantly reduced numbers of bacteria reisolated from all four tissues compared with those of the wild-type strain. Although the decrease of viable bacteria in blood circulation and systemic organs may lead to a lower risk of brain infection, the significantly weaker capacity for adherence to and invasion of bEnd.3 cells could also justify the effect of T6SS1 on cerebral proliferation.

However, the correlation of inactivation of T6SS1 with cerebral proliferation could not be confirmed by these results, because the decrease of viable bacteria in blood circulation and systemic organs may also lead to a lower risk of brain infection.

The functional difference of T6SS1 and T6SS2 in APEC adds something new to the growing repertoire of T6SS regulation mechanisms and phenotypes. In this study, we found that the binding competences of VgrG-T6SS1 and VgrG-T6SS2 for DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells are significantly different. VgrG-T6SS2 can specifically recognize and bind to the surface of BMECs, whereas it does not bind DF-1 cells. In contrast, the receptors of VgrG-T6SS1 were nonspecific or ubiquitous in most cell lines, including DF-1 and bEnd.3 cells, and even HeLa cells in a previous study (14, 55). The similarity between the gp27 domain of VgrG protein and the tail fiber protein of bacteriophage has been shown previously (10, 18). The tail fiber protein of a tailed phage has the receptor binding function and decides the host specificity of the phage (21, 56). The experimental results above suggested that T6SSs have significant host specificity and share a similar mechanism with bacteriophage. Similar results have been analyzed in our previous studies (36); the absence of four important β-sheets in the gp27 domain of VgrG-T6SS1 caused a more positive electrostatic potential, which would confer a lower degree of host specificity and allow VgrG to bind multiple different host cell species.

In summary, two distinguishable and functional T6SSs, multipurpose T6SS1 and conservative T6SS2 (Fig. 9), were reported in this study in APEC K1 isolates. Moreover, the pivotal role of VgrG proteins in recognition/binding-sensitive cells was specifically shown for the first time, which revealed that T6SS1 and T6SS2 of APEC function in different pathogenic pathways. The results indicated that T6SS1 was involved in the proliferation of APEC in systemic infection, whereas T6SS2 was responsible only for cerebral infection (Fig. 9).

FIG 9.

Model for roles of T6SS1 and T6SS2 in pathogenic process of APEC K1 isolate. We propose a potential model to illustrate the roles of these two T6SSs in vivo. T6SS1 has functional diversity (e.g., biofilm formation, type I fimbriae, and competition proliferation) and aims at a wide range of host cells. These directly or indirectly affect its pathogenicity. In contrast, T6SS2 plays a key role only in APEC K1 interaction with BMECs. CP, bacterial cytoplasm; IM, bacterial inner membrane; PP, bacterial periplasm; OM, bacterial outer membrane; ECM, extracellular milieu; PM, host cell plasma membrane.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (no. 31372455), and the project was funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

We thank Philip R. Hardwidge, Department of Diagnostic Medicine, Kansas State University, for correcting the typographical and grammatical errors throughout the whole manuscript. We also gratefully acknowledge Ganwu Li, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine, Iowa State University, for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 June 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01769-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ron EZ. 2006. Host specificity of septicemic Escherichia coli: human and avian pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:28–32. 10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dho-Moulin M, Fairbrother JM. 1999. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Vet. Res. 30:299–316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao L, Gao S, Huan H, Xu X, Zhu X, Yang W, Gao Q, Liu X. 2009. Comparison of virulence factors and expression of specific genes between uropathogenic Escherichia coli and avian pathogenic E. coli in a murine urinary tract infection model and a chicken challenge model. Microbiology 155:1634–1644. 10.1099/mic.0.024869-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunther NT, Snyder JA, Lockatell V, Blomfield I, Johnson DE, Mobley HL. 2002. Assessment of virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial mutants in which the invertible element is phase-locked on or off. Infect. Immun. 70:3344–3354. 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3344-3354.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman JA, Wass C, Stins MF, Kim KS. 1999. The capsule supports survival but not traversal of Escherichia coli K1 across the blood-brain barrier. Infect. Immun. 67:3566–3570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SH, Stins MF, Kim KS. 2000. Bacterial penetration across the blood-brain barrier during the development of neonatal meningitis. Microbes Infect. 2:1237–1244. 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tivendale KA, Logue CM, Kariyawasam S, Jordan D, Hussein A, Li G, Wannemuehler Y, Nolan LK. 2010. Avian-pathogenic Escherichia coli strains are similar to neonatal meningitis E. coli strains and are able to cause meningitis in the rat model of human disease. Infect. Immun. 78:3412–3419. 10.1128/IAI.00347-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingle LE, Bailey CM, Pallen MJ. 2008. Type VI secretion: a beginner's guide. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:3–8. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pukatzki S, McAuley SB, Miyata ST. 2009. The type VI secretion system: translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:11–17. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cascales E. 2008. The type VI secretion toolkit. EMBO Rep. 9:735–741. 10.1038/embor.2008.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filloux A, Hachani A, Bleves S. 2008. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology 154:1570–1583. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burtnick MN, Brett PJ, Harding SV, Ngugi SA, Ribot WJ, Chantratita N, Scorpio A, Milne TS, Dean RE, Fritz DL, Peacock SJ, Prior JL, Atkins TP, Deshazer D. 2011. The cluster 1 type VI secretion system is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 79:1512–1525. 10.1128/IAI.01218-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shrivastava S, Mande SS. 2008. Identification and functional characterization of gene components of type VI secretion system in bacterial genomes. PLoS One 3:e2955. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Pace F, Nakazato G, Pacheco A, de Paiva JB, Sperandio V, Da SW. 2010. The type VI secretion system plays a role in type 1 fimbria expression and pathogenesis of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect. Immun. 78:4990–4998. 10.1128/IAI.00531-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Tao J, Yu H, Ni J, Zeng L, Teng Q, Kim KS, Zhao GP, Guo X, Yao Y. 2012. Hcp family proteins secreted via the type VI secretion system coordinately regulate Escherichia coli K1 interaction with human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 80:1243–1251. 10.1128/IAI.05994-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonemann G, Pietrosiuk A, Diemand A, Zentgraf H, Mogk A. 2009. Remodelling of VipA/VipB tubules by ClpV-mediated threading is crucial for type VI protein secretion. EMBO J. 28:315–325. 10.1038/emboj.2008.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman JM, Agnello DM, Zheng H, Andrews BT, Li M, Catalano CE, Gonen T, Mougous JD. 2013. Haemolysin coregulated protein is an exported receptor and chaperone of type VI secretion substrates. Mol. Cell 51:584–593. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leiman PG, Basler M, Ramagopal UA, Bonanno JB, Sauder JM, Pukatzki S, Burley SK, Almo SC, Mekalanos JJ. 2009. Type VI secretion apparatus and phage tail-associated protein complexes share a common evolutionary origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:4154–4159. 10.1073/pnas.0813360106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arisaka F, Kanamaru S, Leiman P, Rossmann MG. 2003. The tail lysozyme complex of bacteriophage T4. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35:16–21. 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00098-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Li W, Zhang Q, Wang H, Xu X, Diao B, Zhang L, Kan B. 2009. The core oligosaccharide and thioredoxin of Vibrio cholerae are necessary for binding and propagation of its typing phage VP3. J. Bacteriol. 191:2622–2629. 10.1128/JB.01370-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu J, Zhang J, Lu X, Liang W, Zhang L, Kan B. 2013. O antigen is the receptor of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 El Tor typing phage VP4. J. Bacteriol. 195:798–806. 10.1128/JB.01770-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. 2007. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:15508–15513. 10.1073/pnas.0706532104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parthasarathy G, Yao Y, Kim KS. 2007. Flagella promote Escherichia coli K1 association with and invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 75:2937–2945. 10.1128/IAI.01543-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Niu C, Shi Z, Xia Y, Yaqoob M, Dai J, Lu C. 2011. Effects of ibeA deletion on virulence and biofilm formation of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 79:279–287. 10.1128/IAI.00821-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez G, Sierra JC, Sha J, Wang S, Erova TE, Fadl AA, Foltz SM, Horneman AJ, Chopra AK. 2008. Molecular characterization of a functional type VI secretion system from a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb. Pathog. 44:344–361. 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allignet J, Galdbart JO, Morvan A, Dyke KG, Vaudaux P, Aubert S, Desplaces N, El Solh N. 1999. Tracking adhesion factors in Staphylococcus caprae strains responsible for human bone infections following implantation of orthopaedic material. Microbiology 145:2033–2042. 10.1099/13500872-145-8-2033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonifait L, Grignon L, Grenier D. 2008. Fibrinogen induces biofilm formation by Streptococcus suis and enhances its antibiotic resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4969–4972. 10.1128/AEM.00558-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grenier D, Grignon L, Gottschalk M. 2009. Characterisation of biofilm formation by a Streptococcus suis meningitis isolate. Vet. J. 179:292–295. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grasteau A, Tremblay YD, Labrie J, Jacques M. 2011. Novel genes associated with biofilm formation of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Vet. Microbiol. 153:134–143. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell AB, Hood RD, Bui NK, LeRoux M, Vollmer W, Mougous JD. 2011. Type VI secretion delivers bacteriolytic effectors to target cells. Nature 475:343–347. 10.1038/nature10244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng CH, Cai M, Shin S, Xie Y, Kim KJ, Khan NA, Di Cello F, Kim KS. 2005. Escherichia coli K1 RS218 interacts with human brain microvascular endothelial cells via type 1 fimbria bacteria in the fimbriated state. Infect. Immun. 73:2923–2931. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2923-2931.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao Y, Xie Y, Perace D, Zhong Y, Lu J, Tao J, Guo X, Kim KS. 2009. The type III secretion system is involved in the invasion and intracellular survival of Escherichia coli K1 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 300:18–24. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01763.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dreyfus A, Schaller A, Nivollet S, Segers RP, Kobisch M, Mieli L, Soerensen V, Hussy D, Miserez R, Zimmermann W, Inderbitzin F, Frey J. 2004. Use of recombinant ApxIV in serodiagnosis of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae infections, development and prevalidation of the ApxIV ELISA. Vet. Microbiol. 99:227–238. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma J, Sun M, Bao Y, Pan Z, Zhang W, Lu C, Yao H. 2013. Genetic diversity and features analysis of type VI secretion systems loci in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli by wide genomic scanning. Infect. Genet. Evol. 20:454–464. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma AT, McAuley S, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ. 2009. Translocation of a Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion effector requires bacterial endocytosis by host cells. Cell Host Microbe 5:234–243. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aschtgen MS, Gavioli M, Dessen A, Lloubes R, Cascales E. 2010. The SciZ protein anchors the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli type VI secretion system to the cell wall. Mol. Microbiol. 75:886–899. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, Gifford CA, Goodman AL, Joachimiak G, Ordonez CL, Lory S, Walz T, Joachimiak A, Mekalanos JJ. 2006. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science 312:1526–1530. 10.1126/science.1128393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF, Mekalanos JJ. 2006. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1528–1533. 10.1073/pnas.0510322103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schembri MA, Klemm P. 2001. Biofilm formation in a hydrodynamic environment by novel fimh variants and ramifications for virulence. Infect. Immun. 69:1322–1328. 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1322-1328.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skyberg JA, Siek KE, Doetkott C, Nolan LK. 2007. Biofilm formation by avian Escherichia coli in relation to media, source and phylogeny. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102:548–554. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russell AB, LeRoux M, Hathazi K, Agnello DM, Ishikawa T, Wiggins PA, Wai SN, Mougous JD. 2013. Diverse type VI secretion phospholipases are functionally plastic antibacterial effectors. Nature 496:508–512. 10.1038/nature12074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Kim KS. 2002. Role of OmpA and IbeB in Escherichia coli K1 invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Pediatr. Res. 51:559–563. 10.1203/00006450-200205000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Germon P, Chen YH, He L, Blanco JE, Bree A, Schouler C, Huang SH, Moulin-Schouleur M. 2005. ibeA, a virulence factor of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 151:1179–1186. 10.1099/mic.0.27809-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacIntyre DL, Miyata ST, Kitaoka M, Pukatzki S. 2010. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:19520–19524. 10.1073/pnas.1012931107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bladergroen MR, Badelt K, Spaink HP. 2003. Infection-blocking genes of a symbiotic Rhizobium leguminosarum strain that are involved in temperature-dependent protein secretion. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16:53–64. 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.1.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chow J, Mazmanian SK. 2010. A pathobiont of the microbiota balances host colonization and intestinal inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 7:265–276. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jani AJ, Cotter PA. 2010. Type VI secretion: not just for pathogenesis anymore. Cell Host Microbe 8:2–6. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarz S, Hood RD, Mougous JD. 2010. What is type VI secretion doing in all those bugs? Trends Microbiol. 18:531–537. 10.1016/j.tim.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pezoa D, Blondel CJ, Silva CA, Yang HJ, Andrews-Polymenis H, Santiviago CA, Contreras I. 2014. Only one of the two type VI secretion systems encoded in the Salmonella enterica serotype Dublin genome is involved in colonization of the avian and murine hosts. Vet. Res. 45:2. 10.1186/1297-9716-45-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holbourn KP, Shone CC, Acharya KR. 2006. A family of killer toxins. Exploring the mechanism of ADP-ribosylating toxins. FEBS J. 273:4579–4593. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vendeville A, Winzer K, Heurlier K, Tang CM, Hardie KR. 2005. Making ‘sense' of metabolism: autoinducer-2, LuxS and pathogenic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:383–396. 10.1038/nrmicro1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim KS. 2002. Strategy of Escherichia coli for crossing the blood-brain barrier. J. Infect. Dis. 186(Suppl 2):S220–S224. 10.1086/344284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Pace F, Boldrin DPJ, Nakazato G, Lancellotti M, Sircili MP, Guedes SE, Dias DSW, Sperandio V. 2011. Characterization of IcmF of the type VI secretion system in an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) strain. Microbiology 157:2954–2962. 10.1099/mic.0.050005-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomassen E, Gielen G, Schutz M, Schoehn G, Abrahams JP, Miller S, van Raaij MJ. 2003. The structure of the receptor-binding domain of the bacteriophage T4 short tail fibre reveals a knitted trimeric metal-binding fold. J. Mol. Biol. 331:361–373. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00755-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyer F, Fichant G, Berthod J, Vandenbrouck Y, Attree I. 2009. Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: what can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? BMC Genomics 10:104. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.