Abstract

Serial blood passage of virulent Babesia bovis in splenectomized cattle results in attenuated derivatives that do not cause neurologic disease. Tick transmissibility can be lost with attenuation, but when retained, attenuated B. bovis can revert to virulence following tick passage. This study provides data showing that tick passage of the partially attenuated B. bovis T2Bo derivative strain further decreased virulence compared with intravenous inoculation of the same strain in infected animals. Ticks that acquired virulent or attenuated parasites by feeding on infected cattle were transmission fed on naive, splenectomized animals. While there was no significant difference between groups in the number of parasites in the midgut, hemolymph, or eggs of replete female ticks after acquisition feeding, animals infected with the attenuated parasites after tick transmission showed no clinical signs of babesiosis, unlike those receiving intravenous challenge with the same attenuated strain prior to tick passage. Additionally, there were significantly fewer parasites in blood and tissues of animals infected with tick-passaged attenuated parasites. Sequencing analysis of select B. bovis genes before and after tick passage showed significant differences in parasite genotypes in both peripheral blood and cerebral samples. These results provide evidence that not only is tick transmissibility retained by the attenuated T2Bo strain, but also it results in enhanced attenuation and is accompanied by expansion of parasite subpopulations during tick passage that may be associated with the change in disease phenotype.

INTRODUCTION

Babesia bovis, an apicomplexan parasite that infects cattle in tropical and subtropical regions, is transmitted by the tick vector Rhipicephalus microplus. Neurological signs may accompany fever and anemia during acute infection by virulent strains (1). This neurovirulence is associated with the cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes to endothelial cells, which subsequently leads to sequestration within cerebral capillaries, causing neurological disease (2, 3). Animals that recover from acute babesiosis without treatment become persistently infected and are potential reservoirs for tick transmission within the herd (4).

To decrease the mortality of cattle exposed to B. bovis in regions where the pathogen is endemic, live attenuated vaccines are routinely used. Attenuated strains of B. bovis are derived in vivo through rapid serial blood passage of parental virulent strains in splenectomized cattle (5). As these attenuated strains are not associated with neurologic disease, it has been hypothesized that attenuation is directly associated with the loss of endothelial cell cytoadherence and sequestration. However, recent in vivo studies using brain biopsies of cattle infected with the parental and attenuated T2Bo strains of B. bovis demonstrated that while there is an absence of neurovirulence of the attenuated strain after intravenous inoculation, sequestration was not completely eliminated (6). Tick passage has been reported to restore neurovirulence of attenuated B. bovis strains (7, 8), suggesting the possibility that parasites with the cytoadherent, sequestration phenotype maintained in the strain population can be positively selected during tick passage, consistent with these recent data. Alternatively, recombination between two or more strains within the tick midgut during the sexual stages of parasite development could generate new strains with enhanced virulence (9–11). When R. microplus ticks feed on acutely or persistently infected animals, they ingest B. bovis-infected erythrocytes. Within the tick, the parasite undergoes a developmental cycle that progresses from a haploid to a diploid stage and back to a haploid stage, resulting in larval progeny containing B. bovis sporozoites that are infective to cattle. Thus, tick passage allows both genetic recombination and selection and provides multiple opportunities for development of a parasite population in larval progeny that is different from the population acquired by adult ticks.

If tick passage can revert an attenuated strain to virulence, it is also possible that an attenuated strain can be further selected for enhanced attenuation (such as decreased infectivity, altered growth rate, and increased host immunoreactivity). Since neurovirulence and attenuation are phenotypes relevant only in the mammalian host, it is probable that these trait selections are incidental in the tick host unless they are genetically linked to other traits favorable for the survival of the parasites as a species in the tick. Nonetheless, the concept of the tick vector as a medium for phenotype selection is important to understand as the debate regarding the practicality of live vaccine continues.

In this study, we utilized the previously characterized virulent B. bovis strain T2Bo and its attenuated derivative strain that does not cause neurological disease in naive animals (12). The attenuated T2Bo strain does, however, retain the ability to cause anemia and fever after blood passage and can cause clinical disease in splenectomized cattle. We tested whether tick transmissibility is retained in the partially attenuated T2Bo strain and found not only that tick transmission occurs but also that tick passage results in a loss of virulence that is accompanied by the expansion of variant parasite subpopulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites, ticks, and animals.

The virulent strain T2Bo of B. bovis (T2Bo_vir) and an attenuated derivative strain (T2Bo_att) obtained after 29 rapid passages in splenectomized calves via intravenous inoculation were used in this study. The virulent parental and partially attenuated derivative strains were previously validated to reflect their designated phenotypes of neurovirulence and nonneurovirulence, respectively (12).

B. bovis-free Rhipicephalus microplus (La Minita), originally collected from cattle on pasture in Starr County, TX, and currently maintained by USDA-ARS Animal Disease Research Unit, Moscow, ID, is a competent vector for B. bovis and was used for tick acquisition and transmission feeding experiments as previously described (13).

Male Holstein calves were obtained at 3 to 6 months of age from a Washington State dairy, quarantined at the Washington State University Animal Resource Unit, and given health checks at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital (College of Veterinary Medicine, Washington State University). All calves used in the study were uninfected with B. bovis, as determined by sourcing from the United States, which is declared free of bovine babesiosis by the World Organization for Animal Health, and by confirmation of the absence of serum antibody and parasites by competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (cELISA) (VMRD, Pullman, WA) and quantitative PCR, respectively, as previously described (4). All calves were splenectomized at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital a minimum of 2 weeks prior to application of larval ticks for acquisition or transmission feedings. Four animals were used for acquisition feedings (2 per group), and 10 animals were used for transmission feedings (1 and 4 per group). Animal procedures were approved by the Washington State University Animal Care and Use Committee (ASAF 03322-002) and the University of Idaho (IACUC, 2013-66; biosafety, B-010-13) in accordance with institutional guidelines based on the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (14).

Tick feeding.

For the acquisition feedings, uninfected larvae hatched from one gram of eggs were placed under a cloth patch on two naive, splenectomized calves 2 weeks prior to intravenous (IV) inoculation with blood stabilate containing 2 × 107 infected red blood cells (iRBC) from either T2Bo_vir or T2Bo_att B. bovis. During the adult phase of the feeding, ticks were exposed to peak parasitemia just prior to becoming replete. After detachment from the infected animals, replete adult female ticks were collected, washed, and incubated in 24-well plates (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 26°C with 96% relative humidity to allow B. bovis development in the ticks and production of infected egg masses for use in the transmission experiment. Hemolymph from a subset of individual engorged females was sampled on day 8 post-drop-off. Briefly, hemolymph was collected from replete females by inoculating 10 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the abdomen using a 12.7- by 0.21-mm needle, followed by extraction of the hemolymph containing fluid with pressurized capillary tubing. After hemolymph collection, midgut and ovaries were dissected from each female. Egg masses from individual replete females were pooled by group (T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att), aliquoted into one-gram vials, and incubated at 26°C with 96% relative humidity for approximately 2 weeks until embryonation and hatching. After hatching, groups of larvae were stored at 16°C for ∼2 weeks until the commencement of the transmission feeding experiments.

Two splenectomized calves, one per group, were used in the first study, while four splenectomized calves per group (T2Bo_vir or T2Bo_att) were used for tick transmission feeding experiments. In a manner similar to that of the acquisition feeding, each calf was infested with larvae from one gram of eggs derived from females fed on cattle infected with either T2Bo_vir or T2Bo_att. Larvae were allowed to transmission feed for 4 days, at which time a subset of approximately 200 larvae were collected from each calf for PCR analyses. All calves subjected to transmission feeding were monitored daily for clinical signs of bovine babesiosis, including elevation of temperature, decrease in hematocrit, and parasitemia, up to 26 days after tick transmission.

All calves were euthanized after tick acquisition and transmission feeding. Tissue samples from brain, heart, lung, liver, kidney, and skin were collected in duplicate and frozen in liquid nitrogen for DNA extraction and quantitative PCR (qPCR) or fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin for histological analysis.

Evaluation of capillary sequestration.

Formalin-fixed tissues were paraffin embedded, cut into 5-μm sections, placed on glass slides, and stained with Giemsa (Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, Pullman, WA). Sequestration of B. bovis iRBC in tissue capillaries was evaluated histologically by counting a minimum of 100 iRBC and noninfected red blood cells (RBC) in longitudinal sections of capillaries. Manual counts were performed in duplicate by the same individual at a magnification of ×63, and the average percentage of infected erythrocytes in capillaries was determined for each tissue using the formula iRBC/total RBC × 100.

Parasite load in animal and tick tissues.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from frozen cerebrum, lung, heart, liver, kidney, and skin tissues stored at −80°C, by using MP Biomedicals lysing matrix A as per the manufacturer's recommendation (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Equivalent starting amounts of tissues (100 mg) were processed in triplicate for each animal from each of the two groups. Genomic DNA was also extracted from 100 μl of whole blood using a DNeasy blood and tissue DNA kit as per the manufacturer's recommendation (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantitative PCR targeting the merozoite surface antigen 1 gene (msa-1) was performed as previously described (4, 15). A positive control containing 10 ng of T2Bo gDNA and a negative control consisting of naive tissue or blood DNA were included.

Genomic DNA was extracted from pools of 4-day transmission-fed larvae (10 larvae/pool), individual egg masses, ovaries, and midgut samples using MP Biomedicals lysing matrix D as per the manufacturer's recommendation (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Parasites were quantified from these samples using the msa-1 qPCR assay as described above. A positive control containing 10 ng of T2Bo_vir gDNA and gDNA negative controls from naïve-larva, calf, and tick tissues were included (4, 15). Genomic DNA was also extracted from 100 μl of individual tick hemolymph using the DNeasy blood and tissue DNA kit as per the manufacturer's recommendation (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Genetic markers in virulent and attenuated strains.

Five out of 245 putative protein-coding genes scattered across chromosomes 3 and 4 were selected to monitor potential changes in the B. bovis population composition before and after passage through the tick vector. The major criterion used in the selection of these potential genetic markers was based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified through genome sequence comparison between virulent T2Bo and its attenuated derivative sequences (A. O. T. Lau, unpublished data) (16). These genes were also chosen based on their relatively short coding sequences, allowing more streamlined sequence comparisons and lower incidences of technical PCR errors. The genes selected as genetic markers were BBOV_III010230 (hypothetical protein), BBOV_III010750 (hypothetical protein), BBOV_III011010 (tRNA synthetase class II core domain), BBOV_III011220 (hypothetical protein), and BBOV_IV001430 (putative membrane protein). Sequence comparison between the virulent and attenuated BBOV_III010230 showed that there were two SNPs and a 142-nucleotide (nt) deletion in the attenuated sequence. The deletion is likely due to the absence of a contig covering that region of the gene. Both SNPs result in shorter translated products in the attenuated strain. Comparison of sequences from virulent and attenuated BBOV_III010750 revealed that while two contigs containing this gene were recovered in the attenuated strain, one contig has a sequence identical to that of the virulent strain, while the second one contained a few SNPs throughout the coding region, resulting in a shorter translated product. A similar scenario applied to BBOV_III011010. Comparison of sequences from virulent and attenuated BBOV_III011220 showed that in addition to SNPs detected, an additional codon was present in the attenuated sequence, resulting in a translated product that was one amino acid longer than the virulent strain. BBOV_IV001430 sequence comparison indicated that both virulent and attenuated sequences were almost identical, with a single missing nucleotide in the attenuated sequence resulting in a premature stop codon and thus a shorter translated protein in the attenuated strain. Primers were manually designed for the open reading frame of each gene, and the corresponding product size and total number of nucleotide polymorphisms between virulent and attenuated reference strains are shown in Table 1. These five genes were amplified and sequenced from cerebral and peripheral blood gDNA samples from each animal used in the acquisition and transmission feedings (n = 10). Positive and negative controls included the amplification of msa-1 gene from infected-culture-derived gDNA and no template, respectively, as well as the amplification of msa-1 in all animal samples. When reactions yielded a single product of the predicted size, the amplified product was cloned as per manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Thirty colonies from each transformation were selected for sequence analysis (MacVector v.12.0.2). The raw sequences were trimmed, translated, and aligned, and phylogenies were built using nearest-neighbor joining and bootstrap analysis (MacVector v.12.0.2).

TABLE 1.

Primer names, functions, sequences, expected product sizes, and numbers of SNPs in virulent and attenuated reference sequences of the five B. bovis genetic markers

| Gene ID | Putative function | Sequence (5′–3′) |

Product size (base pairs) | No. (%) of SNPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||||

| BBOV_IV001430 | Putative membrane protein | ATGCTAATGGTCTACGTCC | TCAGATAGGGAATATAGGACTGA | 533 | 1 (0.2) |

| BBOV_III011010 | tRNA synthetase class II core domain | ATGGGATTCAGGGTATATAAAGC | TTACCTGGCTACAGCAAG | 1,320 | 20 (4.7) |

| BBOV_III011220 | Hypothetical protein | ATGAAAGGATTCTATTCGGAGC | TCACCCCCATTCACC | 423 | 22 (1.7) |

| BBOV_III010230 | Hypothetical protein | ATGGCTCCGGTACTG | TCACCATTCGGTCACTAG | 1,242 | 2 (0.2)a |

| BBOV_III010750 | Hypothetical protein | ATGCCGCTACAGTTGAAA | TTACCACAGAATGGGTTCC | 1,122 | 18 (1.6) |

The virulent reference strain also contains a 143-bp insertion at nt 1023.

Statistical analysis.

Fisher's exact test was used to determine a group size of four (P < 0.05) for this study, assuming that neurologic clinical signs would be apparent only in the virulent group and would not be apparent in the attenuated group. Parasite infection levels in calf and tick tissues were compared using an unpaired t test. A two-tailed t test was used for hematocrit, parasitemia, and tick tissue comparisons (P < 0.05) (GraphPad Prism v. 5.0a). Phylograms were used to determine the number of different sequence variants for each translated sequence, and each variant was assigned a number (i.e., III011010-1a, III011010-2a etc.). The frequency of each variant under different conditions (i.e., virulent acquisition [vAQ] or attenuated acquisition [aAQ] in blood or cerebrum and virulent transmission [vTR] or attenuated transmission [aTR] in blood or cerebrum) was determined, and the frequencies between the numbered variants before and after tick passage were compared for each condition using a two-by-three Fisher's exact test to generate a 2-tailed P value (http://vassarstats.net/fisher2x3.html).

RESULTS

Loss of clinical signs and tissue sequestration following tick passage of T2Bo_att strain.

Two splenectomized animals, each inoculated with either T2Bo_vir or T2Bo_att blood stabilates, were used as a source for R. microplus parasite acquisition (AQ). Maximum rectal temperature (106.4°F versus 105.9°F) and maximum percent decrease in hematocrit (44.8% versus 44%) were similar between groups. The percent peripheral parasitemia (PPE) was determined for both infected AQ animal groups (Table 2), confirming the development of acute babesiosis. Tick transmission (TR) of both parasite strains was carried out using two additional splenectomized animals. Clinical signs were observed in the TR-T2Bo_vir animal (107.0°F temperature, 31.7% decrease in hematocrit), similar to those described above for the AQ animals. However, no fever or decrease in hematocrit consistent with acute babesiosis was observed in the TR-T2Bo_att animal (102.2°F temperature, 10.8% decrease in hematocrit) (Table 2). Additionally, PPE was determined for the TR-T2Bo_vir animal but was below detection in the TR-T2Bo_att animal (Table 2). The lack of clinical signs in TR-T2Bo_att animal was unexpected and prompted an expanded study where tick and mammalian tissue samples were quantitatively analyzed.

TABLE 2.

Clinical parameters of animals in first study during tick acquisition and transmission feedinga

| B. bovis strain | Maximum temp (°F) | Maximum decrease in hematocrit (%) | Maximum peripheral parasitemia (%)c | Maximum peripheral parasitemia (copies/μl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2Bo_vir AQ | 106.4 | 44.8 | 0.4 | NS |

| T2Bo_vir TR | 107.0 | 31.7 | 0.5 | 432 |

| T2Bo_att AQ | 105.9 | 44.0 | 5.2 | NS |

| T2Bo_att TR | 102.2 | 10.8b | NPD | NPD |

AQ, acquisition feeding; TR, transmission feeding; NPD, no parasites detected; NS, no sample; vir, virulent; att, attenuated.

No fever and no major hematocrit decrease were detected at any time during the study in the T2Bo_att TR animal.

Peripheral parasitemia was determined manually.

As in the first study, two splenectomized animals were intravenously inoculated with either T2Bo_vir or T2Bo_att blood stabilates for R. microplus acquisition feeding (AQ). A rectal temperature greater than 103°F, a decrease in hematocrit, and detectable parasitemia began at 7 days postinfection for both animal groups (Table 3). Peak blood levels of parasites as determined by qPCR were 4,920 copies/μl and 354 copies/μl for T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att, respectively (Table 3). Detached, replete female ticks from both groups were collected over 2 days during acute babesiosis. Egg masses from infected females were pooled into two groups, and the ability of T2Bo_vir- or T2Bo_att-infected larvae to transmit B. bovis was evaluated by transmission feeding larvae on splenectomized cattle and monitoring clinical signs. Animals infected with the T2Bo_vir strain after tick transmission had a rectal temperature greater than 103°F 8 days postattachment (Table 3), mimicking the clinical signs observed during the acquisition feeding. In contrast, animals infected with the T2Bo_att strain after tick transmission never developed consistently elevated rectal temperatures (Table 3). A significant difference was observed between the groups in the mean percent decrease in hematocrit (T2Bo_vir, mean of 45.8; T2Bo_att, mean of 22.1; P = 0.0286), and peripheral blood parasitemia (T2Bo_vir, mean of 54,060; T2Bo_att, mean of 45; P = 0.0286) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Clinical parameters of animals in second study during tick acquisition and transmission feeding

| B. bovis straina | Mean maximum temp (°F) | Mean maximum decrease in hematocrit (%) | Mean maximum peripheral parasitemia (copies/μl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2Bo_vir AQ | 106.9b | 61.1b | 4,920 |

| T2Bo_vir TR | 106.5 | 45.8d | 54,060d |

| T2Bo_att AQ | 105.8b | 51.5b | 354 |

| T2Bo_att TR | 102.7c | 22.1c,d | 45d |

AQ, acquisition feed; TR, transmission feed; vir, virulent; att, attenuated.

No significant difference between groups during acquisition feeding was detected.

No fever and no major hematocrit decrease were detected at any time during the study in the T2Bo_att TR animal.

A significant difference (P < 0.05) in hematocrit and parasitemia was detected between T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att TR groups.

Results obtained from the second study corroborated those obtained from the first study and demonstrate that both AQ-infected animal groups consistently succumbed to acute babesiosis with characteristic clinical signs. However, the results obtained from the TR-infected animals are consistently divergent, in that no clinical signs were observed in animals infected with the T2Bo_att strain.

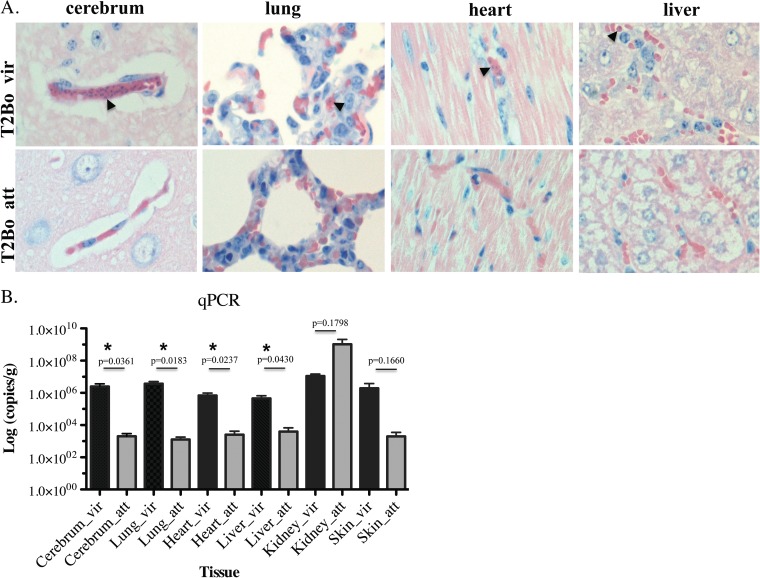

The absence of clinical babesiosis in cattle infected with tick-transmitted attenuated B. bovis, despite low levels of parasites detected in peripheral blood, is in contrast to observations made with intravenously inoculated attenuated-B. bovis-infected animals (6). To investigate if the lack of clinical babesiosis was associated with an absence of tissue sequestration, cerebrum, heart, liver, lung, skin, and kidney were evaluated from 10 animals used in the transmission feeding. As expected, histological evaluation revealed that all animals infected with T2Bo_vir via tick transmission had high numbers of sequestered iRBC within the cerebrum, kidney, and skin similar to those observed in the first study (mean = 88.9, 76.2, and 56.8%, respectively) and significantly lower numbers of sequestered iRBC in heart, liver, and lung (Fig. 1A; Table 4). Analysis of tissues from animals infected with T2Bo_att by tick transmission showed an absence of iRBC capillary sequestration in all tissues examined (Fig. 1A), corroborating the first study. However, parasite DNA was detected in the T2Bo_att tissues from the second study while it was below detection in the first study (Fig. 1B). Using qPCR, significantly more parasites per gram of tissue were detected in the T2Bo_vir than the T2Bo_att group in the cerebrum (2.5 × 106 versus 2.0 × 103), lung (3.7 × 106 versus 1.3 × 103), heart (6.9 × 105 versus 3.0 × 103), and liver (4.5 × 105 versus 4.0 × 103) but not in kidney or skin (Fig. 1B). The number of parasites per gram of tissue for the T2Bo_vir transmission animal in the first study ranged between 6.4 × 106 to 3.8 × 107 for all tissues (Table 4). With the exception of liver, histopathological examination of tissues in the T2Bo_vir-infected animals did not indicate severe congestion of vessels with erythrocytes, which could further elevate the level of parasites per gram of tissue detected in the T2Bo_vir group. Collectively, these data suggest a higher infection level in the T2Bo_vir-infected transmission feeding animal group.

FIG 1.

Sequestration and parasite levels in postmortem tissues of T2Bo_vir- and T2Bo_att-infected animals. (A) Sequestration determined by histologic analysis. Infected red blood cells are indicated by arrowheads. (B) Parasite level per gram of tissue, as determined by qPCR. vir, virulent; att, attenuated.

TABLE 4.

Sequestration of infected erythrocytes and parasite load in tissues from animals inoculated with T2Bo_vir-infected larvae in the first tick transmission studya

| Tissue | Sequestration (%) | Tissue parasite load (copies/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrum | 92.6 | 1.80E + 07 |

| Lung | 56.0 | 3.73E + 07 |

| Heart | 55.1 | 1.97E + 07 |

| Liver | 5.4 | 1.49E + 07 |

| Kidney | 79.3a | 3.81E + 07 |

| Skin | 67.5a | 6.38E + 06 |

No difference in sequestration levels between the two studies was detected.

Parasite levels in tick tissues are similar between T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att strains.

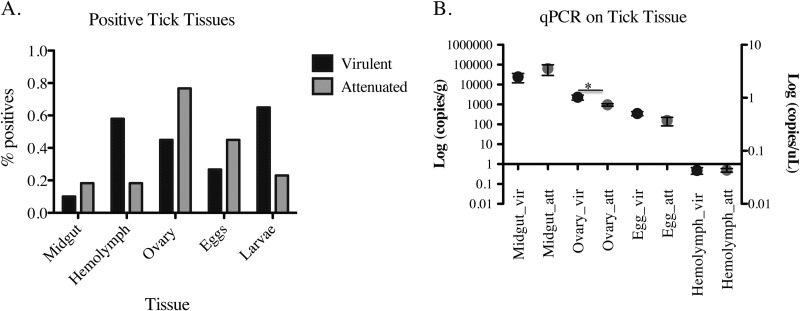

To determine if differences in capillary sequestration and tissue parasite levels between the T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att transmission animals were a result of infection level differences within the tick, hemolymph, ovaries, midguts, eggs, and pools of 4-day-fed larvae from both groups of infected tick material were analyzed by PCR. While there was a higher overall percentage of positive samples in the hemolymph (58.0% versus 18.3%) and larvae (65.0% versus 23.0%) of T2Bo_vir-infected ticks, the T2Bo_att-infected ticks had a higher percentage of samples positive for parasites in the midguts (18.3% versus 10%), ovaries (76.7% versus 45.0%) and eggs (45.0% versus 26.7%) (Fig. 2A). When parasite level was evaluated by qPCR using gDNA isolated from hemolymph, ovary, midgut, and eggs of both T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att groups, no statistically significant difference was detected for the hemolymph, midgut, and egg samples (Fig. 2B). A significantly higher parasite load was observed in the ovaries in the T2Bo_vir group (2,290 versus 959 copies/g) (Fig. 2B). The quantification of gDNA from larval pools was outside the lowest standard dilution in the standard curve, and thus no quantitative data are available for larvae. From these data, we conclude that although there was a higher percentage of larva pools infected with the T2Bo_vir strain, there was no statistical difference in the infection level of T2Bo_vir-infected and T2Bo_att-infected parasites in all the tick tissues.

FIG 2.

(A) Percentage of positive tick tissues after acquisition feeding on T2Bo_vir- or T2Bo_att-infected animals. (B) Level of parasites in tick tissues. The left y axis indicates parasite level per gram of tissue; the right y axis indicates parasite level per μl of hemolymph. An asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05). vir, virulent; att, attenuated.

Variation of genotypes after tick transmission.

While there was no significant quantitative difference in tick tissue infection levels for T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att strains, there was a subsequent significant difference in tissue parasite levels between the two groups subjected to transmission feeding. This led us to hypothesize that genetic or population strain differences may be responsible for the divergent outcomes after tick transmission. To test this hypothesis, samples of B. bovis T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att pre- and post-tick transmission parasites from cerebrum and peripheral blood of all animals were evaluated using five genetic marker genes. The selection of cerebral and peripheral tissue samples for the B. bovis population investigation was based on the consistent and statistically significant tissue sequestration, tissue parasite load, and parasitemia differences observed between the two transmission groups of animals (Table 3; Fig. 1). Using primer sets specific for both the virulent and attenuated sequences of the respective genes of interest, we compared the gene sequences in the cerebral and peripheral blood samples of T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att animal groups pre- and post-tick transmission.

Sequence variants of the five genes were detected in both cerebral and peripheral blood samples. A variant is defined as a translated genotype sequence of a particular gene with at least a single amino acid difference in comparison to the others. All amino acid sequences for each gene were compared using a phylogram with bootstrap analysis in which identical sequences were grouped as a single variant. The variants were then given a numerical sequence value (i.e., gene III0110101-1a, III011010-2a, etc.). This resulted in eight detectable variants from 352 BBOV_IV001430 sequences, 31 variants from 356 BBOV_III011010 sequences, 32 variants from 308 BBOV_III011220 sequences, 40 variants from 373 BBOV_III010230 sequences, and 28 variants from 273 BBOV_III010750 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Due to the low level of parasitemia in the animals infected with T2Bo_att from transmission-fed ticks (aTR), all five genes as well as msa-1 in the aTR blood samples could not be amplified and were not analyzed (Table 5). III011010 and IV001430 could not be amplified from the cerebrum of the aTR animals (Table 5), leaving only the variants from BBOV_III011220, III010230, and III010750 for aTR analysis in this tissue. Due to the lack of data for the peripheral blood samples, comparison of genetic marker sequences of the T2Bo_att B. bovis population between blood and cerebrum post-tick transmission was not possible for all five genes. Thus, our analyses of potential population composition changes as a result of selection following tick passage were performed primarily using data obtained from the T2Bo_vir-infected group.

TABLE 5.

PCR amplification of genetic markers for each conditiona

| Gene | No. of positive animals/total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrum |

Blood |

|||||||

| vAQ | aAQ | vTR | aTR | vAQ | aAQ | vTR | aTRb | |

| BBOV_IV001430 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

| BBOV_III011010 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

| BBOV_III011220 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

| BBOV_III010230 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 1/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 3/4 | 0/4 |

| BBOV_III010750 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 1/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 3/4 | 0/4 |

| BBOV_msa-1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

v, virulent; a, attenuated; TR, transmission; AQ, acquisition; msa-1, merozoite surface antigen 1.

aTR blood samples are the only condition for which all biomarkers were not detectable.

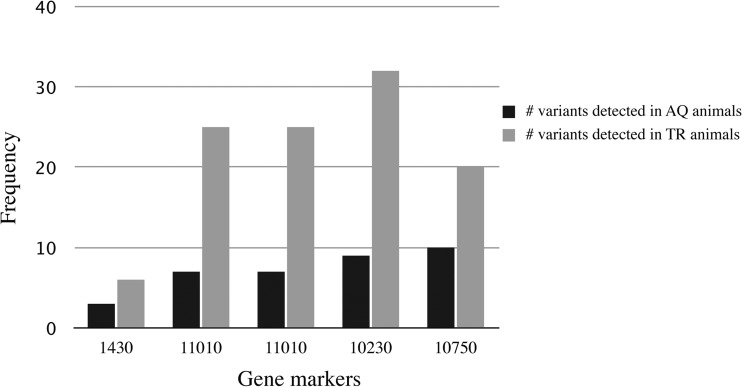

The results of sequence analysis and variant comparison before and after tick passage and between brain and blood are shown in Fig. 3 and Tables 6 and 7. In the T2Bo_vir peripheral blood samples for gene IV001430, one variant was found in both the pre- and post-tick passage groups, while the remaining five variants were detected only after tick passage in the vTR group (Table 6). For the cerebral samples, two variants were found in each of the vAQ and vTR samples, respectively, with a single variant found in both groups (Table 6). In the T2Bo_att-infected animals, one variant was found in both the pre-tick (aAQ) blood and cerebral samples, and this same variant was also found in the vAQ and vTR blood and cerebral samples (Table 7; also, see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material).

FIG 3.

Frequency of gene marker variants detected in acquisition-fed (AQ) and transmission feeding (TR) animals.

TABLE 6.

Summary of number of unique variants and total number of sequences evaluated for each condition of the T2Bo_vir straina

| Genes | No. of variants (no. of sequences analyzed) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vAQ, blood | vTR, blood | vAQ and vTR, blood | Total vir, blood | vAQ, cerebrum | vTR, cerebrum | vAQ and vTR, cerebrum | Total vir, cerebrum | |

| BBOV_IV001430 | 0b | 5 (45) | 1 (97) | 6 (142) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (144) | 5 (148) |

| BBOV_III011010 | 2 (31) | 14 (103) | 1 (11) | 17 (145) | 3 (30) | 13 (115) | 0d | 16 (145) |

| BBOV_III011220 | 2 (31) | 5 (104) | 0c | 7 (135) | 2 (23) | 9 (932) | 1 (2) | 12 (118) |

| BBOV_III010230 | 2 (32) | 17 (94) | 0c | 19 (126) | 2 (28) | 10 (126) | 0d | 12 (154) |

| BBOV_III010750 | 2 (18) | 13 (108) | 1 (8) | 16 (134) | 1 (9) | 5 (72) | 0d | 6 (81) |

v, virulent; TR, transmission; AQ, acquisition; vir, virulent organisms.

All vAQ sequences for IV001430 in blood were also found in vTR sequences.

No shared sequences between vAQ and vTR blood were found.

No shared sequences between vAQ and vTR cerebrum were found.

TABLE 7.

Summary of number of unique variants and total number of sequences evaluated for each condition of the T2Bo_att straina

| Gene | No. of variants (no. of sequences analyzed) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aAQ, blood | aTR, bloodb | aAQ and aTR, bloodb | Total att, blood | aAQ, cerebrum | aTR, cerebrum | aAQ and aTR, cerebrum | Total att, cerebrum | |

| BBOV_IV001430 | 1 (31) | NA | NA | 1 (31) | 1 (31) | NAc | NAc | 1 (31) |

| BBOV_III011010 | 1 (31) | NA | NA | 1 (31) | 1 (32) | NAc | NAc | 1 (32) |

| BBOV_III011220 | 3 (31) | NA | NA | 3 (31) | 2 (28) | 11 (92) | 0d | 13 (120) |

| BBOV_III010230 | 1 (32) | NA | NA | 1 (32) | 4 (30) | 5 (31) | 0d | 9 (61) |

| BBOV_III010750 | 4 (21) | NA | NA | 4 (21) | 2 (16) | 1 (21) | 0d | 3 (37) |

a, attenuated; AQ, acquisition; TR, transmission; att, attenuated organisms; NA, not applicable.

No transmission sequences from blood samples with the attenuated strain were amplified for any gene; thus, no comparison between acquisition and transmission could be determined.

No transmission sequences from cerebral samples with the attenuated strain were amplified; thus, no comparison between acquisition and transmission could be determined.

No shared sequences between aAQ and aTR in blood for III011220, III010230, and III010750 were detected.

In gene III011010, two and 14 variants were detected in the T2Bo_vir peripheral blood of the animals before (vAQ) and after (vTR) tick transmission, respectively, and a single variant was found in both groups. Similarly, three and 13 variants were detected in the acquisition (vAQ) and post-tick transmission (vTR) cerebrum samples, respectively (Table 6). No variants were shared between vAQ and vTR cerebral samples for this gene. Similar to IV001430, the single variant identified in the pre-tick T2Bo_att (aAQ) cerebral sample was shared with the pre-tick T2Bo_vir (vAQ) blood and post-tick T2Bo_vir (vTR) blood and cerebral samples (Table 7). However, the single variant from the aAQ blood sample was not shared with any other condition (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material).

In the T2Bo_vir peripheral blood for gene III011220, two and five variants were observed in the pre-tick (vAQ) and post-tick (vTR) passages, respectively, with none of these being carried through tick selection. Among the variants detected in the cerebrum, two and 11 were exclusively identified in the pre-tick (vAQ) and post-tick (vTR) passage groups, respectively, and one variant was identified in both pre- and post-tick passage (Table 6). Three and two variants were detected in the peripheral blood and the cerebrum of the T2Bo_att-infected animals prior to tick passage (aAQ). Following tick passage, 11 unique variants were identified in the cerebral samples (aTR) (Table 6). A single variant found in the aTR cerebral sample was also observed in the vTR blood sample (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material).

For gene III010230, two unique variants were each identified in the T2Bo_vir peripheral blood and cerebrum prior to tick passage (vAQ). Following tick passage, 17 and 10 variants were found in the blood and cerebrum (vTR), respectively, with no variants being carried through tick passage in the blood or cerebral samples (Table 6). One variant was observed in the peripheral blood, while four were found in the cerebrum prior to tick passage (aAQ) of the T2Bo_att strain (Table 7). Five unique variants were identified in the cerebrum post-tick passage (aTR), and one of these variants was also observed in the vTR blood sample (see Fig. S2D in the supplemental material).

For gene III010750, two variants were identified in the T2Bo_vir peripheral blood and one variant in the cerebrum prior to tick passage (vAQ). Following tick passage (vTR), 13 and five variants were found in the blood and cerebrum, respectively, with a single variant being carried through the tick in the blood samples (Table 6). Four variants were found in the peripheral blood and two in the cerebrum prior to tick passage (aAQ) of the T2Bo_att strain (Table 7). One variant was detected following tick passage (aTR) in the cerebral sample, and this same variant was also detected in the vTR blood sample (see Fig. S2E in the supplemental material).

When Fisher's exact analysis was used, the frequencies of variants from the vAQ and vTR samples were significantly different (Table 8), with the exception of gene IV001430 in cerebrum and peripheral blood samples and gene III010750 in cerebrum samples. The significant difference in the number of variants detected in three of the five genes before and after tick passage suggests that selection occurs within the tick vector. However, there is no evidence that variant selection in T2Bo_vir-infected ticks impacts the virulence phenotype in animals in the transmission-fed-tick group. When the aAQ and aTR cerebrum samples were compared, III011220 and III010230 variant frequencies were statistically significant; however, no comparison was performed for IV0014300 and III011010, since these two genes were not detectable in the cerebral aTR samples. When comparison of variant frequency between blood and cerebrum of the same animal was performed, a statistically significant difference between the numbers of variants was not identified with either the T2Bo_vir or T2Bo_att strain (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

Two-tailed P values generated from a two-by-three Fisher's exact probability test for different conditionsa

| Condition |

P |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBOV_IV001430 | BBOV_III011010 | BBOV_III011220 | BBOV_III010230 | BBOV_III010750 | |

| vAQ vs vTR blood | 0.286 | 0.005 | 0.048 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| vAQ vs vTR cerebrum | 0.600 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.167 |

| aAQ vs aTR cerebrum | NA | NA | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.333 |

| vAQ blood vs vAQ cerebrum | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.099 | 0.333 | 0.250 |

| aAQ blood vs aAQ cerebrum | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.099 | 0.199 | 0.067 |

v, virulent; a, attenuated; AQ, acquisition; TR, transmission; NA, not applicable, as no sequences were obtained from aTR cerebral samples.

DISCUSSION

All animals infected with T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att B. bovis via needle inoculation for tick acquisition feeding exhibited severe, acute clinical babesiosis, despite an approximately 14-fold difference in parasitemia level in the second study. This suggests that a threshold parasitemia level is required to cause severe clinical disease, consistent with previous work by Goff et al. using the T2Bo_vir strain (17). Interestingly, in two separate experiments, animals infected with the same virulent or attenuated T2Bo strain after tick passage had divergent clinical presentations, with retention of the virulence phenotype in T2Bo_vir-infected animals and a surprising lack of virulence in T2Bo_att-infected animals. While splenic clearance can impact clinical presentation, it did not have a role in this study, as all animals were splenectomized. We ruled out the possibility that the animals receiving T2Bo_att from transmission-fed ticks were not infected, since postmortem tissue examination using qPCR in the second study confirmed infection in both animal groups. This confirmed that the T2Bo_att strain remained tick transmissible but lost virulence properties. Our recent study showed that the T2Bo_att B. bovis parasites have lost the property of neurovirulence but maintained the ability to cytoadhere to brain capillaries at a significantly reduced level (6). Two possible explanations of the combined data from this and the previous study can be suggested. First, tick passage of the T2Bo_att strain results in a change in which the parasitized red blood cells have a reduced ability to adhere to capillary endothelium, resulting in attenuation. Alternatively, the lack of neurologic signs could be due to an overall lower parasitemia in the animals infected with tick-transmitted T2Bo_att. Both scenarios could occur together.

Analysis of the parasite numbers in tissues from transmission-fed ticks that had acquired the same parasite load leads us to conclude that lower parasitemia in animals receiving T2Bo_att from transmission-fed ticks is not a result of a lower inoculum from the tick, as there was no significant difference in the infection levels of all tissues with the exception of tick ovary. Sampling of the larval salivary glands is not a technically feasible option, and the evaluation of the parasite load in the larval stage was not possible due to insufficient material. Therefore, we base our conclusion of equal inoculum in part on a study by Howell et al. (18) which demonstrated that parasite levels in host peripheral blood are directly associated with the level of kinetes in the hemolymph. In addition, as few as 10 parasites of the T2Bo_vir strain are required for infection and subsequent severe clinical signs to occur, with no differences in clinical disease associated with inocula containing more than 1,000 parasites (17). With approximately 10,000 larvae being used for transmission feeding in our experiments, it seems very likely that the inoculum contained many more than the minimum infective dose of parasites required for virulent disease.

If parasite inoculum level is unlikely to account for the change in virulence phenotype, it remains possible that there was selection of a parasite subpopulation with reduced infectivity through tick passage. If this was the case, then although the initial amount of parasites inoculated into transmission feeding animal groups was the same, T2Bo_vir- and T2Bo_att-infected animals could have a very different clinical outcome. The role of the environment within the vector in effecting change in the clinical phenotype has been documented in related apicomplexa. In a recent study, a virulent Plasmodium strain was demonstrated to lose virulence in the mammalian host following vector passage (19). We investigated whether a selection process in the tick resulted in a change in the parasite population by analyzing genetic markers pre- and post-tick transmission for both strains.

The five genetic markers chosen to follow potential population changes demonstrated that parasite diversity exists through permutation in gene sequences or SNPs and that the population structure fluctuates depending on the selection pressure exerted by specific hosts. Gene IV001430 encodes a putative membrane protein of unknown function and is a gene with the fewest variants detected throughout the study (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Among all the variants, 1430-1a (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) is the predominant variant circulating in peripheral blood and cerebrum during tick acquisition. Tick passage does not cause a shift in the predominant genotype, as 1430-1a remains the dominant variant within the cerebrum of animals infected with transmission-acquired T2Bo_vir (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Interestingly, additional IV001430 variants were detected in the peripheral blood of the same animals, supporting the idea that tick passage may allow for the expansion of subpopulations that were below the limit of PCR detection prior to tick selection (Fig. 3). It is premature to predict the involvement of gene IV001430 in virulence even though 1430-1a was maintained as the dominant gene variant in T2Bo_vir-infected animals pre-and post-tick passage where virulence was maintained. Nevertheless, it is interesting that IV001430 detection was not possible in cerebral tissues from animals infected with tick-transmitted T2Bo_att, while several other genetic markers as well as the positive control were detectable in the same tissues. Plausible explanations for the absence of amplification of this gene include (i) failure of gene-specific primers due to sequence divergence post-tick passage and (ii) loss of this gene in the T2Bo_att subpopulation that was selected through tick passage.

Genes III011010, III011220, III010230, and III010750 present a slightly different picture. First, more variants were detected for these four genes than IV001430 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Second, dominant variants of these genes in the peripheral blood (11010-3a, 11220-4a, 10230-3a, and 10750-5a) or cerebrum (11010-5a, 11220-8a, 10230-6a, and 10750-10a) of vAQ samples before tick passage were different from the dominant variants in the same tissues of vTR samples, and only one of these post-tick passage variants (11010-8a) was found in both tissues (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Other than this difference between these four genes and IV001430, a consensus observation emerges in which a dominant variant is represented in pre-tick passage peripheral blood and cerebrum of infected animals, followed by the transition to a more diverse collection of variants post-tick exposure (Fig. 3). These findings support the notion that the tick host environment may encourage variant diversity within the heterologous population. It remains to be proven, however, whether the tick host acts as a hospitable environment for the heterologous population to propagate and expand, while the mammalian host presents a more restrictive growth environment. It is also plausible that the tick environment may further select for individual slow-growth variants among the T2Bo_att population for the mammalian host. The T2Bo_att population may already have been selected to replicate more slowly in vivo than the parental T2Bo_vir strain through the initial attenuation process, and tick transmission may simply enhance this growth phenotype. Thus, despite the same parasite load obtained during tick transmission, infection of animals with T2Bo_vir resulted in a higher parasitemia than those infected with T2Bo_att.

We analyzed whether the frequency of individual variants is significantly different in the blood versus the brain (Table 8) and concluded that there is no statistically significant difference in the number of variants detected for each treatment group. However, unique variants were detected in the blood and cerebrum samples of each group, suggesting that tissue tropism could be a feature of certain variants.

In conclusion, we determined that tick transmissibility of the partially attenuated T2Bo_att strain is maintained during the attenuation process of repeated blood passage and that the infection levels of the virulent and attenuated strains in the tick vector do not differ despite significant differences in peripheral parasitemia in the acquisition animals. The study also demonstrates that the partially attenuated T2Bo_att strain does not revert to virulence following a single tick passage. In contrast, tick passage results in a further reduction of virulence and enhanced attenuation, accompanied by an expanded repertoire of variants, compared to the starting heterologous population of B. bovis T2Bo_vir and T2Bo_att strains.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ignacio Ichaide and Stephen White for providing the B. bovis strains and statistical advice, respectively. We also thank Ralph Horn and James Allison for excellent animal care.

This work was funded by NIH 5K01-OD011154 and USDA-ARS grant 5348-32000-034-00D.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02126-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Callow LL, Dalgliesh RJ, de Vos AJ. 1997. Development of effective living vaccines against bovine babesiosis—the longest field trial? Int. J. Parasitol. 27:747–767. 10.1016/S0020-7519(97)00034-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Everitt JI, Shadduck JA, Steinkamp C, Clabaugh G. 1986. Experimental Babesia bovis infection in Holstein calves. Vet. Pathol. 23:556–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nevils MA, Figueroa JV, Turk JR, Canto GJ, Le V, Ellersieck MR, Carson CA. 2000. Cloned lines of Babesia bovis differ in their ability to induce cerebral babesiosis in cattle. Parasitol. Res. 86:437–443. 10.1007/s004360050691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howell JM, Ueti MW, Palmer GH, Scoles GA, Knowles DP. 2007. Persistently infected calves as reservoirs for acquisition and transovarial transmission of Babesia bovis by Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3155–3159. 10.1128/JCM.00766-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Callow LL, Mellors LT, McGregor W. 1979. Reduction in virulence of Babesia bovis due to rapid passage in splenectomized cattle. Int. J. Parasitol. 9:333–338. 10.1016/0020-7519(79)90083-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sondgeroth KS, McElwain TF, Allen AJ, Chen AV, Lau AO. 2013. Loss of neurovirulence is associated with reduction of cerebral capillary sequestration during acute Babesia bovis infection. Parasites Vectors 6:181. 10.1186/1756-3305-6-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carson CA, Timms P, Cowman AF, Stewart NP. 1990. Babesia bovis: evidence for selection of subpopulations during attenuation. Exp. Parasitol. 70:404–410. 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90124-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Timms P, Stewart NP, De Vos AJ. 1990. Study of virulence and vector transmission of Babesia bovis by use of cloned parasite lines. Infect. Immun. 58:2171–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lew AE, Bock RE, Croft JM, Minchin CM, Kingston TG, Dalgliesh RJ. 1997. Genotypic diversity in field isolates of Babesia bovis from cattle with babesiosis after vaccination. Aust. Vet. J. 75:575–578. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1997.tb14197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leroith T, Brayton KA, Molloy JB, Bock RE, Hines SA, Lew AE, McElwain TF. 2005. Sequence variation and immunologic cross-reactivity among Babesia bovis merozoite surface antigen 1 proteins from vaccine strains and vaccine breakthrough isolates. Infect. Immun. 73:5388–5394. 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5388-5394.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Artzy-Randrup Y, Rorick MM, Day K, Chen D, Dobson AP, Pascual M. 2012. Population structuring of multi-copy, antigen-encoding genes in Plasmodium falciparum. eLife 1:e00093. 10.7554/eLife.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lau AO, Kalyanaraman A, Echaide I, Palmer GH, Bock R, Pedroni MJ, Rameshkumar M, Ferreira MB, Fletcher TI, McElwain TF. 2011. Attenuation of virulence in an apicomplexan hemoparasite results in reduced genome diversity at the population level. BMC Genomics 12:410. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Sullivan PJ, Callow LL. 1966. Loss of infectivity of a vaccine strain of Babesia argentina for Boophilus microplus. Aust. Vet. J. 42:252–254. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1966.tb04715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bastos RG, Ueti MW, Guerrero FD, Knowles DP, Scoles GA. 2009. Silencing of a putative immunophilin gene in the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus increases the infection rate of Babesia bovis in larval progeny. Parasites Vectors 2:57. 10.1186/1756-3305-2-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brayton KA, Lau AO, Herndon DR, Hannick L, Kappmeyer LS, Berens SJ, Bidwell SL, Brown WC, Crabtree J, Fadrosh D, Feldblum T, Forberger HA, Haas BJ, Howell JM, Khouri H, Koo H, Mann DJ, Norimine J, Paulsen IT, Radune D, Ren Q, Smith RK, Jr, Suarez CE, White O, Wortman JR, Knowles DP, Jr, McElwain TF, Nene VM. 2007. Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Pathog. 3:1401–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goff WL, Johnson WC, Cluff CW. 1998. Babesia bovis immunity. In vitro and in vivo evidence for IL-10 regulation of IFN-gamma and iNOS. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 849:161–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howell JM, Ueti MW, Palmer GH, Scoles GA, Knowles DP. 2007. Transovarial transmission efficiency of Babesia bovis tick stages acquired by Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus during acute infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:426–431. 10.1128/JCM.01757-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spence PJ, Jarra W, Levy P, Reid AJ, Chappell L, Brugat T, Sanders M, Berriman M, Langhorne J. 2013. Vector transmission regulates immune control of Plasmodium virulence. Nature 498:228–231. 10.1038/nature12231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.