Abstract

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia IOMTU250 has a novel 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferase-encoding gene, aac(6′)-Iak. The encoded protein, AAC(6′)-Iak, consists of 153 amino acids and has 86.3% identity to AAC(6′)-Iz. Escherichia coli transformed with a plasmid containing aac(6′)-Iak exhibited decreased susceptibility to arbekacin, dibekacin, neomycin, netilmicin, sisomicin, and tobramycin. Thin-layer chromatography showed that AAC(6′)-Iak acetylated amikacin, arbekacin, dibekacin, isepamicin, kanamycin, neomycin, netilmicin, sisomicin, and tobramycin but not apramycin, gentamicin, or lividomycin.

TEXT

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is a globally emerging multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogen that is most commonly associated with respiratory infections in humans (1) and causes an increasing number of nosocomial respiratory tract and bloodstream infections in immunocompromised patients. S. maltophilia exhibits resistance to a broad spectrum of antibiotics, namely, β-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, chloramphenicol, tetracyclines, and polymyxins (1). Several intrinsic antibiotic resistance traits in S. maltophilia are known; an increase in membrane permeability and the presence of chromosomally encoded multidrug resistance efflux pumps have also been observed (2).

Aminoglycoside-resistant mechanisms involve primarily aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (3) and 16S rRNA methylases (4). The 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferases [AAC(6′)s] are of particular interest because they can modify a number of clinically important aminoglycosides. There are two main AAC(6′) subclasses, which differ in their activities against amikacin and gentamicin. The AAC(6′)-I-type enzymes effectively acetylate amikacin but not gentamicin, whereas the AAC(6′)-II-type enzymes effectively acetylate gentamicin but not amikacin (5). To date, 45 genes encoding AAC(6′)-I types, designated aac(6′)-Ia to -Iaj, have been cloned, and their bacteriological or biochemical properties have been characterized (5–8).

S. maltophilia IOMTU250 was isolated from the endotracheal tube of a patient in a medical ward of a hospital in Nepal in 2012. Escherichia coli DH5α (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan) and Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIP (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) were used as hosts for recombinant plasmids and protein expression, respectively. MICs were determined using the microdilution method (9). The MICs of tested aminoglycosides for S. maltophilia IOMTU250 are shown in Table 1. The MICs of other antibiotics were as follows: ampicillin, >1,024 μg/ml; ampicillin-sulbactam, 128 μg/ml; aztreonam, 128 μg/ml; ceftazidime, 8 μg/ml; cephradine, 1,024 μg/ml; cefepime, 64 μg/ml; cefotaxime, 64 μg/ml; cefoxitin, 512 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 8 μg/ml; colistin, 32 μg/ml; fosfomycin, 128 μg/ml; imipenem, 256 μg/ml; levofloxacin, 1 μg/ml; meropenem, 64 μg/ml; minocycline, ≤0.25 μg/ml; penicillin, 512 μg/ml; ticarcillin-clavulanate, 8 μg/ml; tigecycline, ≤0.25 μg/ml; and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 4 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

MICs of various aminoglycosides for S. maltophilia IOMTU250 and E. coli strains transformed with aac(6′)-Iak and aac(6′)-Iz

| Straina | MICb (μg/ml) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABK | AMK | APR | DIB | GEN | ISP | KAN | LIV | NEO | NET | SIS | TOB | |

| S. maltophilia IOMTU250 | 512 | 64 | >512 | 512 | 32 | 64 | 128 | >512 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 64 |

| E. coli DH5α/pSTV28 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| E. coli DH5α/pSTV28-aac(6′)-Iak | 2 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| E. coli DH5α/pSTV28-aac(6′)-Iz | 4 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 16 |

The MICs for S. maltophilia and E. coli strains were determined with Mueller-Hinton broth preparations and individual aminoglycosides.

ABK, arbekacin; AMK, amikacin; APR, apramycin; DIB, dibekacin; GEN, gentamicin; ISP, isepamicin; KAN, kanamycin; LIV, lividomycin; NEO, neomycin; NET, netilmicin; SIS, sisomicin; TOB, tobramycin.

Genomic DNA was extracted from S. maltophilia IOMTU250 using DNeasy blood and tissue kits (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) and sequenced with a MiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, CA). More than 20-fold coverage was achieved. A new 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferase variant was designated aac(6′)-Iak.

A synthetic aac(6′)-Iz gene (462 bp) was produced by Funakoshi Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The aac(6′)-Iak and aac(6′)-Iz genes were cloned into the corresponding sites of pSTV28 using primers SalI-aac(6′)-Iak-F (5′-ATGCGTCGACATGACCGGCAGCGCGGCCACGATCCGCCCG-3′) and PstI-aac(6′)-Iak-R (5′-ATCTGCAGTCACGCCGATGGCTCCAGTGGCATGCGGAAA-3′) and SalI-aac(6′)-Iz-F (5′-ATGGTCGACATGATCGCCAGCGCGCCCACGATCCGCC-3′) and PstI-aac(6′)-Iz-R (5′-ATCTGCAGTCACGCCGATGGCTCCAGCGGCATGCGGAA-3′), respectively. E. coli DH5α was transformed with pSTV28-aac(6′)-Iak or pSTV28-aac(6′)-Iz to assess aminoglycoside resistance.

The open reading frame of AAC(6′)-Iak was cloned into the pQE2 expression vector using the primers SalI-aac(6′)-Iak-F and PstI-aac(6′)-Iak-R for protein expression. Purification of the recombinant AAC(6′)-Iak protein and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis were performed as previously described (7). The kinetic activities of AAC(6′)-Iak were determined as previously described (8).

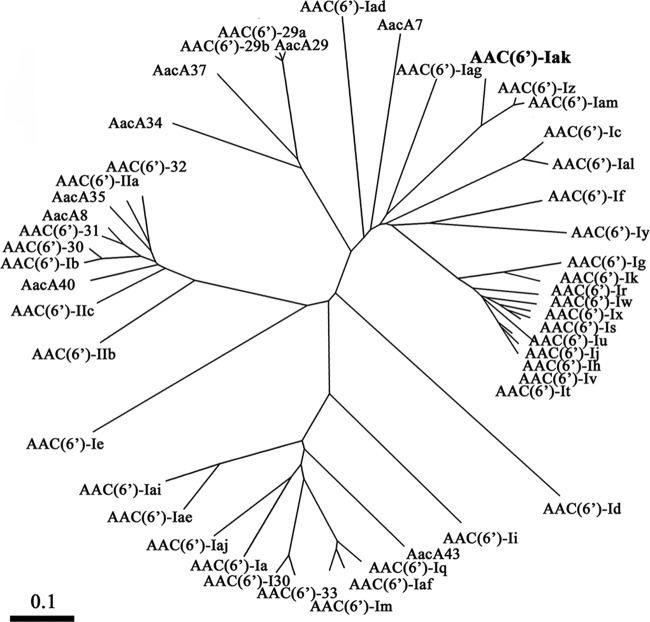

AAC(6′)-Iak consists of 153 amino acids. As shown by the dendrograms of AAC(6′) based on amino acid sequences in Fig. 1, AAC(6′)-Iak is close to AAC(6′)-Iz and AAC(6′)-Iam (accession no. AB971834) from S. maltophilia (10). Multiple sequence alignments among AAC(6′) enzymes revealed that AAC(6′)-Iak had 86.3% identity to AAC(6′)-Iz from S. maltophilia (11), 84.3% identity to AAC(6′)-Iam from S. maltophilia (10), 47.7% identity to AAC(6′)-Iag from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8), 43.1% identity to AAC(6′)-If from Enterobacter cloacae (12), and 42.8% identity to AAC(6′)-Iy from Salmonella enterica (13).

FIG 1.

Dendrogram of 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferases [AAC(6′)s] for comparison with AAC(6′)-Iak. The dendrogram was calculated using the CLUSTAL W2 program. Branch lengths correspond to numbers of amino acid exchanges for the proteins. EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ accession numbers of the proteins are as follows: AAC(6′)-Ia, M18967-1; AAC(6′)-Ib, M23634; AAC(6′)-Ic, M94066; AAC(6′)-Id, X12618; AAC(6′)-Ie, M13771; AAC(6′)-If, X55353; AAC(6′)-Ig, L09246; AAC(6′)-Ih, L29044; AAC(6′)-Ii, L12710-1; AAC(6′)-Ij, L29045; AAC(6′)-Ik, L29510; AAC(6′)-Im, CAA91010; AAC(6′)-Iq, AF047556-1; AAC(6′)-Ir, AF031326; AAC(6′)-Is, AF031327; AAC(6′)-It, AF031328; AAC(6′)-Iu, AF031329; AAC(6′)-Iv, AF031330; AAC(6′)-Iw, AF031331; AAC(6′)-Ix, AF031332; AAC(6′)-Iy, AF144880; AAC(6′)-Iz, AF140221; AAC(6′)-Iad, AB119105; AAC(6′)-Iae, AB104852; AAC(6′)-Iaf, AB462903; AAC(6′)-Iag, AB472901; AAC(6′)-Iai, EU886977; AAC(6′)-Iaj, AB709942; AAC(6′)-Iak, AB894482; AAC(6′)-Ial, AB871481; AAC(6′)-Iam, AB971834; AAC(6′)-IIa, M29695; AAC(6′)-IIb, L06163; AAC(6′)-IIc, AF162771; AAC(6′)-29a, AF263519; AAC(6′)-29b, AF263519; AAC(6′)-30, AJ584652; AAC(6′)-31, AJ640197; AAC(6′)-32, EF614235; AAC(6′)-33, GQ337064; AAC(6′)-I30, AY289608; AacA7, U13880; AacA8, AY444814; AacA29, AY139599; AacA34, AY553333; AacA35, AJ628983; AacA37, DQ302723; AacA40, EU912537; and AacA43, HQ247816.

We compared the enzymatic properties of AAC(6′)-Iak with those of AAC(6′)-Iz because they had similar amino acid sequences and were detected in S. maltophilia. As shown in Table 1, E. coli expressing AAC(6′)-Iak or AAC(6′)-Iz showed decreased susceptibility to all aminoglycosides tested except for apramycin, gentamicin, and lividomycin. The MICs of netilmicin and tobramycin for E. coli expressing AAC(6′)-Iak were significantly lower than those for E. coli expressing AAC(6′)-Iz. The MICs of the other aminoglycosides tested were not significantly different between E. coli isolates expressing AAC(6′)-Iak and AAC(6′)-Iz (Table 1).

S. maltophilia IOMTU250 was highly resistant to all aminoglycosides tested, whereas E. coli expressing aac(6′)-Iak was susceptible to all aminoglycosides tested except for dibekacin (Table 1). The discrepancy of aminoglycoside susceptibilities between S. maltophilia and E. coli could be explained by the presence of efflux pump genes specific for S. maltophilia. Whole-genome sequencing with the MiSeq system in this study showed that IOMTU250 had the efflux pump genes specific for S. maltophilia, including smeABC, smeDEF, smeZ, smeJK, and the pcm-tolCsm operon. These genes are known to be associated with aminoglycoside resistance (14–16), although it is difficult to clarify whether or not these efflux pump genes contribute to aminoglycoside resistance together with aac(6′)-Iak in S. maltophilia IOMTU250.

As shown in Table 2, recombinanttk;1 AAC(6′)-Iak and AAC(6′)-Iz acetylated arbekacin, amikacin, dibekacin, isepamicin, kanamycin, neomycin, netilmicin, sisomicin, and tobramycin. The profile of enzymatic activities of AAC(6′)-Iak were similar to those of AAC(6′)-Iz, although AAC(6′)-Iak had higher kcat/Km ratios for neomycin and sisomicin (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of AAC(6′)-Iak and AAC(6′)-Iz enzymesa

| Aminoglycosideb | AAC(6′)-Iak |

AAC(6′)-Iz |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM)c | kcat (s−1)c | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) | Km (μM)c | kcat (s−1)c | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) | |

| ABK | 36 ± 13 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 0.016 | 17 ± 6 | 0.57 ± 0.06 | 0.036 |

| AMK | 32 ± 17 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.004 | 24 ± 5 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.011 |

| DIB | 24 ± 3 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.010 | 31 ± 5 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.015 |

| ISP | 44 ± 9 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.001 | 49 ± 8 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.002 |

| KAN | 30 ± 7 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.001 | 44 ± 9 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.001 |

| NEO | 10 ± 2 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.034 | 13 ± 2 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.023 |

| NET | 70 ± 6 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.004 | 25 ± 8 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.013 |

| SIS | 4 ± 1 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.038 | 7 ± 1 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.028 |

| TOB | 16 ± 4 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.006 | 12 ± 2 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.021 |

The proteins were initially modified by a His tag, which was removed after purification.

ABK, arbekacin; AMK, amikacin; DIB, dibekacin; ISP, isepamicin; KAN, kanamycin; NEO, neomycin; NET, netilmicin; SIS, sisomicin; TOB, tobramycin.

Km and kcat values represent the means of results from 3 independent experiments ± standard deviations.

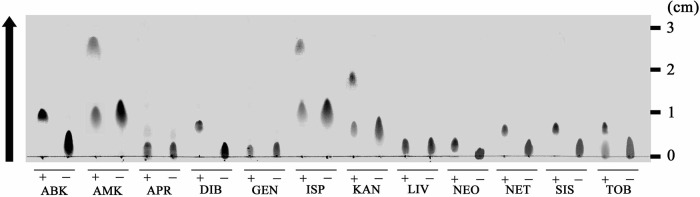

To examine the acetyltransferase activity of AAC(6′)-Iak against aminoglycosides, we performed TLC using the purified recombinant AAC(6′)-Iak. Lividomycin was used as a negative control because it has a hydroxyl group instead of an amino group at the 6′ position and therefore cannot be acetylated by AAC(6′). As shown in Fig. 2, all aminoglycosides tested except for apramycin, gentamicin, and lividomycin were acetylated by AAC(6′)-Iak, and amikacin, isepamicin, kanamycin, and tobramycin were partially acetylated by AAC(6′)-Iak under the experimental conditions used. The TLC data for apramycin, gentamicin, and lividomycin were consistent with the MICs of the aminoglycosides for E. coli with pSTV28-aac(6′)-Iak and E. coli with the control vector (Table 1).

FIG 2.

Analysis of acetylated aminoglycosides by thin-layer chromatography. AAC(6′)-Iak and various aminoglycosides were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of acetyl coenzyme A. ABK, arbekacin; AMK, amikacin; APR, apramycin; DIB, dibekacin; GEN, gentamicin; ISP, isopamicin; KAN, kanamycin; LIV, lividomycin; NEO, neomycin; NET, netilmicin; SIS, sisomicin; TOB, tobramycin.

The substrate specificity of AAC(6′)-Iak was similar to that of AAC(6′)-Iz, although some kinetic parameters of AAC(6′)-Iak were different from those of AAC(6′)-Iz; i.e., the Km for netilmicin and the kcat for tobramycin of AAC(6′)-Iak were different from those of AAC(6′)-Iz (Table 2). The chemical structure of netilmicin is similar to that of sisomicin except for a residue at position 1 in 2-deoxystreptamine ring II (position R2; ethylamino and amino groups, respectively). The ethylamino group at position R2 in netilmicin, therefore, must be critical for the substrate affinity of AAC(6′)-Iz but not that of AAC(6′)-Iak. The chemical structure of tobramycin is similar to that of dibekacin, but tobramycin has a hydroxyl group at position 4′ in ring I (position R1), whereas dibekacin does not, indicating that the hydroxyl group of tobramycin at position R1 negatively affects the turnover rate (kcat) of AAC(6′)-Iak but not that of AAC(6′)-Iz.

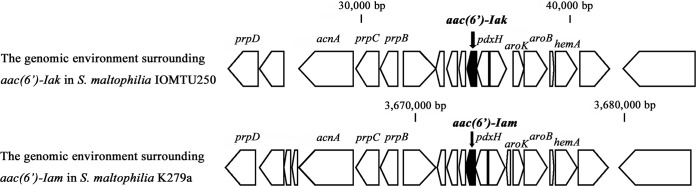

The structure of the genetic environment surrounding aac(6′)-Iak was similar to that of a region surrounding aac(6′)-Iam in S. maltophilia K279a, obtained from a patient in the United Kingdom (10) (Fig. 3). The genetic environment surrounding aac(6′)-Iak from nucleotides (nt) 23623 to 46040 had 92% identity to a genetic region in S. maltophilia K279a (accession no. AM743169) from nt 3660929 to 3683268 (10). The genetic environment surrounding aac(6′)-Iak in S. maltophilia IOMTU250 contained at least 5 housekeeping genes, including purA, acnA, aroK, aroB, and thrA, indicating that aac(6′)-Iak was located in the chromosomal genome.

FIG 3.

Genetic environments surrounding aac(6′)-Iak in S. maltophilia IOMTU250 and aac(6′)-Iam in S. maltophilia K279a.

All the aac(6′)-Iz, aac(6′)-Iak, and aac(6′)-Iam genes were detected in clinical isolates of S. maltophilia (10, 11, 17). These genes contributed to decreased susceptibility to 2-deoxystreptamine aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as neomycin, netilmicin, sisomicin, and tobramycin but not gentamicin (Table 1) (17). The deletion of aac(6′)-Iz in a clinical isolate of S. maltophilia resulted in the increased susceptibility of the isolate (17).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Medicine at Tribhuvan University (approval 6-11-E) and the Biosafety Committee of the Research Institute of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (approval 25-M-038).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence for aac(6′)-Iak and its genetic environments (76,559 bp) was deposited in GenBank under accession number AB894482.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from International Health Cooperation Research (26-A-103 and 24-S-5) and a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (H24-Shinko-Ippan-010).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Brooke JS. 2012. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25:2–41. 10.1128/CMR.00019-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton M, Kerr KG. 1998. Microbiological and clinical aspects of infection associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:57–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw KJ, Rather PN, Hare RS, Miller GH. 1993. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 57:138–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachino J, Arakawa Y. 2012. Exogenously acquired 16S rRNA methyltransferases found in aminoglycoside-resistant pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria: an update. Drug Resist. Updat. 15:133–148. 10.1016/j.drup.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. 2010. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updat. 13:151–171. 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Partridge SR, Thomas LC, Ginn AN, Wiklendt AM, Kyme P, Iredell JR. 2011. A novel gene cassette, aacA43, in a plasmid-borne class 1 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2979–2982. 10.1128/AAC.01582-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tada T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Shimada K, Shimojima M, Kirikae T. 2013. Novel 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferase AAC(6′)-Iaj from a clinical isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:96–100. 10.1128/AAC.01105-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi K, Hayashi I, Kouda S, Kato F, Fujiwara T, Kayama S, Hirakawa H, Itaha H, Ohge H, Gotoh N, Usui T, Matsubara A, Sugai M. 2013. Identification and characterization of a novel aac(6′)-Iag associated with the blaIMP-1-integron in a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 8:e70557. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 23rd informational supplement, M07-A9. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crossman LC, Gould VC, Dow JM, Vernikos GS, Okazaki A, Sebaihia M, Saunders D, Arrowsmith C, Carver T, Peters N, Adlem E, Kerhornou A, Lord A, Murphy L, Seeger K, Squares R, Rutter S, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Harris D, Churcher C, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Thomson NR, Avison MB. 2008. The complete genome, comparative and functional analysis of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia reveals an organism heavily shielded by drug resistance determinants. Genome Biol. 9:R74-2008-9-4-r74. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-4-r74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert T, Ploy MC, Denis F, Courvalin P. 1999. Characterization of the chromosomal aac(6′)-Iz gene of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2366–2371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teran FJ, Suarez JE, Mendoza MC. 1991. Cloning, sequencing, and use as a molecular probe of a gene encoding an aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase of broad substrate profile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:714–719. 10.1128/AAC.35.4.714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnet S, Courvalin P, Lambert T. 1999. Activation of the cryptic aac(6′)-Iy aminoglycoside resistance gene of Salmonella by a chromosomal deletion generating a transcriptional fusion. J. Bacteriol. 181:6650–6655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang LL, Chen HF, Chang CY, Lee TM, Wu WJ. 2004. Contribution of integrons, and SmeABC and SmeDEF efflux pumps to multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:518–521. 10.1093/jac/dkh094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould VC, Okazaki A, Avison MB. 2013. Coordinate hyperproduction of SmeZ and SmeJK efflux pumps extends drug resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:655–657. 10.1128/AAC.01020-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang YW, Hu RM, Yang TC. 2013. Role of the pcm-tolCsm operon in the multidrug resistance of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:1987–1993. 10.1093/jac/dkt148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XZ, Zhang L, McKay GA, Poole K. 2003. Role of the acetyltransferase AAC(6′)-Iz modifying enzyme in aminoglycoside resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:803–811. 10.1093/jac/dkg148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]