Abstract

Glycopeptide antibiotics containing a hydrophobic substituent display the best activity against vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and they have been assumed to be poor inducers of the resistance system. Using a panel of 26 glycopeptide derivatives and the model resistance system in Streptomyces coelicolor, we confirmed this hypothesis at the level of transcription. Identification of the structural glycopeptide features associated with inducing the expression of resistance genes has important implications in the search for more effective antibiotic structures.

TEXT

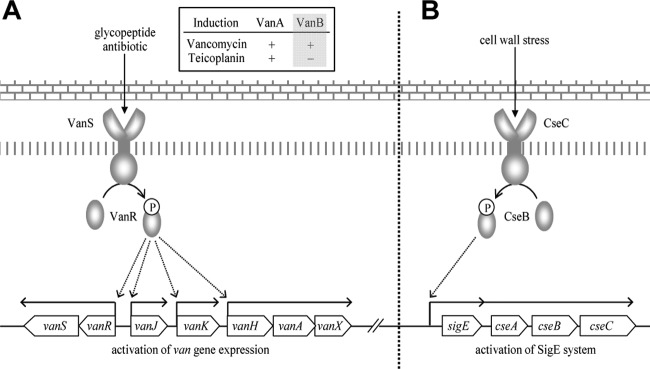

Glycopeptides are an important class of antibiotics active against Gram-positive pathogens, but vancomycin and teicoplanin are the only two glycopeptide antibiotics currently used in the clinic. They exhibit important differences in activity which are believed to be related to their structural differences; however, to date, only the mode of action and mechanism of resistance to vancomycin have been characterized in detail. The rapid spread of resistance to these two drugs through pathogenic bacterial populations is an acute public health concern, and the discovery of additional natural or semisynthetic glycopeptides with more effective antibiotic activities has been targeted (1). A broad spectrum of vancomycin and teicoplanin derivatives has been generated through chemoenzymatic synthesis, and their activity toward pathogenic enterococcal strains was determined (2–9). Interestingly, derivatives containing a hydrophobic substituent were generally found to be significantly more active against both glycopeptide-sensitive and glycopeptide-resistant strains. Dong et al. (8) demonstrated that the key functional difference between vancomycin and teicoplanin is in the absence or presence of lipidation, and evidence that this is related to differing abilities for inducing the resistance system was obtained in experiments correlating MICs with the activity of the VanX enzyme or the activity of the reporter protein in a transcriptional fusion assay (10–13), but a direct effect on transcription of the resistance genes has not been investigated. The important implication of this question, i.e., that it is possible to produce glycopeptide structures which are invisible to existing inducible resistance systems but retain significant antibiotic activity, has led us to seek a definitive answer. Using the vancomycin resistance system in the harmless bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor as a model, we assayed a panel of different natural and semisynthetic glycopeptide antibiotic structures for their ability to induce transcription of the van gene cluster (14) and the general cell wall stress response sigma factor sigE (15) and related this to the antibiotic activity they exhibited. S. coelicolor does not synthesize any glycopeptide antibiotic but does possess a cluster of seven genes (vanRSJKHAX) conferring inducible resistance to vancomycin but not to teicoplanin (similar to the phenotype shown in VanB-type vancomycin-resistant enterococci [VRE]), and it offers a safe and convenient model system for the study of VanB-type glycopeptide resistance (Fig. 1A) (16–21). sigE encodes an extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor (σE), which is part of a signal transduction system that senses and responds to general cell wall stress in S. coelicolor. sigE is constitutively expressed at a low basal level in S. coelicolor but is also generically induced by a wide variety of agents that stress the cell wall (Fig. 1B) (15).

FIG 1.

Organization and regulation of the vancomycin resistance system (A) and the SigE system (B) in S. coelicolor.

We classified all the glycopeptide derivatives analyzed in this study into 4 different groups according to the substituents located at positions 1 and 3 and the presence or absence of a hydrophobic group (Fig. 2). Group 1 includes vancomycin aglycones that carry either a nonhydrophobic carbohydrate or no sugar at all. Group 2 compounds possess aromatic amino acid residues that are cross-linked into their core peptide backbone as for teicoplanin but are otherwise similar to group 1. Group 3 comprises hydrophobic derivatives of vancomycin possessing either a teicoplanin-type monosaccharide containing a saturated lipid or a vancomycin-type disaccharide carrying a chlorobiphenyl residue. Group 4 includes teicoplanin, dalbavancin, and related derivatives containing a saturated lipid as a hydrophobic substituent. Table 1 reports the MICs of each compound against S. coelicolor in liquid culture. Consistent with the previous observations in VRE strains according to Dong et al. (8), the glycopeptide derivatives containing a hydrophobic substituent (groups 3 and 4) were significantly more active against both vancomycin-resistant (wild-type) and vancomycin-sensitive (ΔvanRS) S. coelicolor strains (14). Among the hydrophobic derivatives, teicoplanin derivatives (group 4) generally exhibited greater activity than vancomycin derivatives (group 3). Interestingly, hydrophobic group 3 vancomycin derivatives with a chlorobiphenyl (CBP) substituent were more active than those with a lipid substituent. To determine the correlation between the MIC of a derivative and its ability to induce the van resistance system, the abundance of vanH transcripts in RNA isolated from growing liquid cultures of wild-type S. coelicolor (M600) treated by the addition of 10 μg/ml of each glycopeptide derivative was monitored using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Samples taken 30, 60, and 90 min after treatment were compared to a preinduction control taken immediately before addition (T0), as described previously (21). sigE transcription was similarly quantified as a reporter for cell wall stress. Consistent with previous results, vanH transcription increased immediately in response to vancomycin and reached a maximum level after 30 to 60 min before beginning to decline (Fig. 3). With the exception of chloroeremomycin, group 1 compounds were typically the best inducers of vanH expression, and all, including chloroeremomycin, also induced a strong peak in sigE transcript abundance after 30 min. The derivatives in group 2 behaved similarly, although the maximum level of vanH induction was delayed to 60 min, and the level of expression was generally weaker. Strikingly, the group 3 and 4 derivatives containing hydrophobic substituents exhibited the lowest MICs and failed to induce vanH transcription, except compound 3a, which showed only a very weak induction of vanH expression, but produced a strong transcriptional response for sigE. The order of the vanH induction level starting with the best inducer group can therefore be summarized as group 1, group 2, group 3, and then group 4, and this result perfectly correlates with the observed MIC results. This implies that the strong activity of glycopeptide derivatives toward vancomycin-resistant bacteria is indeed due to their poor ability to induce the resistance system. The hydrophobic substituent presumably prevents productive interaction with the VanS sensor kinase, the key component for triggering the expression of van genes, but has no detrimental effect on antibiotic activity. Assessment of the cell wall stress response by monitoring the level of sigE transcription allowed the comparison of MIC values with vanH transcription to be set in a useful context. Interestingly, sigE was significantly induced following exposure to each compound in groups 1 to 4, but its transcription was quickly and continuously reduced only in cases where vanH expression had also been strongly upregulated (Fig. 3). In contrast, sigE transcription remained high or continued to increase if the compound acted as a poor inducer or noninducer for vanH transcription (i.e., groups 3 and 4). This result implies that the expression of the sigE system alone is insufficient to produce a recovery from the cell wall stress created by the glycopeptides. Those compounds which failed to induce transcription of vanH therefore caused continuous cell wall stress and damage which was in turn reflected in their improved activity against vancomycin-resistant strains. A group of damaged glycopeptide derivatives produced by Edman degradation or reductive hydrolysis and exhibiting a significantly reduced affinity toward the d-Ala-d-Ala dipeptide terminus of peptidoglycan precursors was also analyzed (2). Although the damaged derivatives share virtually identical stereochemical structures with their corresponding parent glycopeptides, their biological activities are vastly different due to modification of the binding pocket for the d-Ala-d-Ala dipeptide (22, 23). Similar results were obtained in this study, where both damaged vancomycin (D-1a) and damaged teicoplanin (D-4a) exhibited no activity in the MIC tests and failed to induce transcription of either vanH or sigE. Interestingly, however, the MIC test showed that both damaged versions of CBP-vancomycin (D-3f) and dalbavancin (D-4d) retained significant antibiotic activity despite the damage to their d-Ala-d-Ala binding pockets (Table 1 and Fig. 3). In contrast to D-1a and D-4a, both compounds also induced a low but sustained increase in sigE transcription over the 90-min period of the study (Fig. 3). This indicates that these two derivatives possess a second mode of antibiotic action against cell wall biosynthesis in addition to that mediated by binding to the d-Ala-d-Ala termini of peptidoglycan precursors.

FIG 2.

Chemical structure of glycopeptide derivatives used in this study.

TABLE 1.

MICs for glycopeptide derivatives against S. coelicolor in liquid culturea

| Group and compound | MIC (μg/ml) of indicated compound against: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Glycopeptide-sensitive strain (ΔvanRS) | Glycopeptide-resistant strain (wild type) | |

| Group 1 | ||

| 1a vancomycin | 0.2 | >100 |

| 1b vancomycin pseudoaglycone | 0.4 | >100 |

| 1c vancomycin aglycone | <0.3 | >100 |

| 1d epi-vancomycin | 0.2 | >100 |

| 1e vancomycin plus putrescine | <0.1 | 15 |

| 1f chloroeremomycin | <0.1 | 20 |

| 1g balhimycin | 0.1 | 45 |

| Group 2 | ||

| 2a glucosylated teicoplanin aglycone | <0.1 | 20 |

| 2b teicoplanin aglycone | <0.3 | 20 |

| 2c teicoplanin pseudoaglycone | <0.1 | 20 |

| 2d epi-vanco-Glc teicoplanin | <0.1 | 10 |

| Group 3 | ||

| 3a 2-aminodecanoyl-Glc vancomycin | 0.3 | 10 |

| 3b 6-aminodecanoyl-Glc vancomycin | 0.4 | 5 |

| 3c 6-aminodecyl-Glc vancomycin | <0.1 | 1 |

| 3d C6-CBP vancomycin | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| 3e C6-amino CBP vancomycin | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| 3f CBP vancomycin | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| 3g CBP vancomycin plus putrescine | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| Group 4 | ||

| 4a teicoplanin | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| 4b 2-aminodecanoyl-Glc teicoplanin | <0.1 | 3 |

| 4c 6-aminodecanoyl-Glc teicoplanin | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| 4d dalbavancin | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Damaged glycopeptide derivatives | ||

| D-1a damaged vancomycin | >100 | >100 |

| D-4a damaged teicoplanin | >100 | >100 |

| D-3f damaged CBP-vancomycin | 2 | 10 |

| D-4d damaged dalbavancin | 2 | 18 |

For experimental details, see the supplemental material.

FIG 3.

Induction of vanH and sigE transcription in S. coelicolor M600 in response to glycopeptide derivatives. Total RNAs were extracted from each sample and analyzed using qRT-PCR. The x axis indicates time (min) after addition of the treatment, and the y axis shows the fold change in expression relative to the level at time zero. For raw qRT-PCR data, see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material. For the detailed experimental procedure, see the supplemental material.

This work clarifies the relationship between glycopeptide structure, antibiotic activity and the ability to induce the VanB-type van resistance system. By integrating data from MIC studies with reporters for transcription of the van resistance (vanH) and cell wall stress response (sigE) systems in an S. coelicolor model, we confirm for the first time that the activity of glycopeptide derivatives previously identified against resistant pathogenic enterococcal strains can be attributed to an inability to activate the transcription of the van resistance system. Derivatives with large hydrophobic substituents were shown to be the most successful at evading detection by the VanB-type resistance mechanism while retaining potent antibiotic activity. Significant activity was also identified in two damaged derivatives whose structures rendered them incapable of interacting normally with their d-Ala-d-Ala target groups. Such structure-activity data have the potential to inform the future design and production of novel, more effective glycopeptide antibiotic structures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Royal Society (grant 516002.K5877/ROG) and the Medical Research Council (grant G0700141).

We thank Mark Buttner and Andy Hesketh for helpful discussion and comments on the manuscript. We also thank Daniel Kahne for his kind gift of glycopeptide derivatives.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03668-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bugg TDH, Wright GD, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh CT. 1991. Molecular basis for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147: biosynthesis of a depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursor by vancomycin resistance proteins VanH and VanA. Biochemistry 30:10408–10415. 10.1021/bi00107a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth PM, Stone DJM, Williams DH. 1987. The Edman degradation of vancomycin: preparation of vancomycin hexapeptide. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 22:1694–1695 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagarajan R, Schabel AA, Occolowitz JL, Counter FT, Ott JL, Felty-Duckworth AM. 1989. Synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of N-alkyl vancomycins. J. Antibiot. 42:63–72. 10.7164/antibiotics.42.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malabarba A, Trani A, Strazzolini P, Cietto G, Ferrari P, Tarzia G, Pallanza R, Berti M. 1989. Synthesis and biological properties of N63-carboxamides of teicoplanin antibiotics: structure-activity relationships. J. Med. Chem. 32:2450–2460. 10.1021/jm00131a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boger DL, Weng J-H, Miyazaki S, McAtee JJ, Castle SL, Kim SH, Mori Y, Rogel O, Strittmatter H, Jin Q. 2000. Thermal atropisomerism of teicoplanin aglycon derivatives: preparation of the P,P,P and M,P,P atropisomers of the teicoplanin aglycon via selective equilibration of the DE ring system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122:10047–10055. 10.1021/ja002376i [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Losey HC, Peczuh MW, Chen Z, Eggert US, Dong SD, Pelczer I, Kahne D, Walsh CT. 2001. Tandem action of glycosyltransferases in the maturation of vancomycin and teicoplanin aglycones: novel glycopeptides. Biochemistry 40:4745–4755. 10.1021/bi010050w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerns R, Dong SD, Fukuzawa S, Carbeck J, Kohler J, Silver L, Kahne D. 2000. The role of hydrophobic substituents in the biological activity of glycopeptide antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122:12608–12069. 10.1021/ja0027665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong SD, Oberthür M, Losey HC, Anderson JW, Eggert US, Peczuh MW, Walsh CT, Kahne D. 2002. The structural basis for induction of VanB resistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:9064–9065. 10.1021/ja026342h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberthür M, Leimkuhler C, Kruger RG, Lu W, Walsh CT, Kahne D. 2005. A systematic investigation of the synthetic utility of glycopeptide glycosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:10747–10752. 10.1021/ja052945s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baptista M, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Arthur M. 1996. Specificity of induction of glycopeptide resistance genes in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2291–2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evers S, Courvalin P. 1996. Regulation of VanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the VanSB-VanRB two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J. Bacteriol. 178:1302–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. 1996. Quantitative analysis of the metabolism of soluble cytoplasmic peptidoglycan precursors of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. Mol. Microbiol. 21:33–44. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill CM, Krause KM, Lewis SR, Blais J, Benton BM, Mammen M, Humphrey PP, Kinana A, Janc JW. 2010. Specificity of induction of the vanA and vanB operons in vancomycin-resistant enterococci by telavancin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2814–2818. 10.1128/AAC.01737-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong H-J, Hutchings MI, Neu JM, Wright GD, Paget MS, Buttner MJ. 2004. Characterisation of an inducible vancomycin resistance system in Streptomyces coelicolor reveals a novel gene (vanK) required for drug resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1107–1121. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong H-J, Paget MSB, Buttner MJ. 2002. A signal transduction system in Streptomyces coelicolor that activates the expression of a putative cell wall glycan operon in response to vancomycin and other cell wall-specific antibiotics. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1199–1211. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02960.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong H-J, Hutchings MI, Hill L, Buttner MJ. 2005. The role of the novel Fem protein VanK in vancomycin resistance in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Biol. Chem. 280:13055–13061. 10.1074/jbc.M413801200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchings MI, Hong H-J, Buttner MJ. 2006. The vancomycin resistance VanRS signal transduction system of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 59:923–935. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koteva K, Hong H-J, Wang XD, Nazi I, Hughes D, Naldrett MJ, Buttner MJ, Wright GD. 2010. A vancomycin photoprobe identifies the histidine kinase VanSsc as a vancomycin receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6:327–329. 10.1038/nchembio.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesketh A, Hill C, Mokhtar J, Novotna G, Tran N, Bibb M, Hong H-J 2011. Genome-wide dynamics of a bacterial response to antibiotics that target the cell envelope. BMC Genomics 12:226. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novotna G, Hill C, Vicent K, Liu C, Hong H-J. 2012. A novel membrane protein, VanJ, conferring resistance to teicoplanin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1784–1796. 10.1128/AAC.05869-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwun MJ, Novotna G, Hesketh AR, Hill L, Hong H-J. 2013. In vivo studies suggest that induction of VanS-dependent vancomycin resistance requires binding of the drug to d-Ala-d-Ala termini in the peptidoglycan cell wall. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:4470–4480. 10.1128/AAC.00523-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldman RC, Baizman ER, Longley CB, Branstrom AA. 2000. Chlorobiphenyl-desleucyl-vancomycin inhibits the transglycosylation process required for peptidoglycan synthesis in bacteria in the absence of dipeptide binding. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:209–214. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08959.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SJ, Matsuoka S, Patti GJ, Schaefer J. 2008. Vancomycin derivative with damaged d-Ala-d-Ala binding cleft binds to cross-linked peptidoglycan in the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry 47:3822–3831. 10.1021/bi702232a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.