Abstract

A population analysis of 103 multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Croatian hospitals was performed. Twelve sequence types (STs) were identified, with a predominance of international clones ST235 (serotype O11 [41%]), ST111 (serotype O12 [15%]), and ST132 (serotype O6 [11%]). Overexpression of the natural AmpC cephalosporinase was common (42%), but only a few ST235 or ST111 isolates produced VIM-1 or VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamases or PER-1 or GES-7 extended-spectrum β-lactamases.

TEXT

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major nosocomial pathogen causing infections associated with high mortality rates (1). In addition to intrinsic antimicrobial resistance, it readily acquires resistance to antipseudomonal drugs; of ultimate concern is the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains (1, 2). The MDR phenotype develops mainly through accumulation of mutations affecting efflux, cell permeability, antimicrobial target sites, and expression of the natural β-lactamase AmpC; of note also is the acquisition of resistance genes, including those encoding β-lactamases such as metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) and class A or class D extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (1, 2). Such genes may spread further horizontally, and their presence promotes clonal dissemination (3–7). The development of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (8) has intensified the epidemiological analysis of P. aeruginosa. Studies on selected strains and regional or national analyses have shown that several successful clones are responsible for the spread of MDR P. aeruginosa (3, 9–14), often associated with MBLs and/or ESBLs (12, 14, 15). Our main aim was to describe the clonal structure of MDR P. aeruginosa subpopulations circulating in Croatian health care institutions.

The study included 103 consecutive nonduplicate MDR P. aeruginosa clinical isolates identified through the network of the Croatian Committee for Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance (16). Between 1 October and 31 December 2008, the laboratories collected all isolates that were not susceptible to at least one agent in 3 or more drug categories, and they sent these isolates to the Reference Centre for Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance in Zagreb, Croatia. The isolates were from 16 laboratories in 9 cities (catchment population, 43.2% of total population), and the majority were from 8 sites in the Zagreb area (47 isolates [45.6%]). The isolates were mainly from elderly patients (median age, 65 years) in internal medicine wards or intensive care units (60.4% of isolates) and were cultured mostly from urine and respiratory tract samples (46.6% and 28.2%, respectively). Susceptibility of the isolates was evaluated by broth microdilution testing according to CLSI guidelines (17). For isolates resistant to all β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones, susceptibility to colistin was determined by Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Almost all isolates were nonsusceptible to at least one cephalosporin and one aminoglycoside (98.0% and 99.0%, respectively) (Table 1). Rates of nonsusceptibility to fluoroquinolones and carbapenems were also high (90.0% and 83.5%, respectively); 16 isolates (15.5%) were susceptible to colistin only.

TABLE 1.

STs, serotypes, PFGE types, susceptibility to selected antimicrobials, and sites of isolation of P. aeruginosa isolates

| ST | Serotype | PFGE XbaI type (no. of isolates)a | PFGE SpeI type (no. of isolates)a | MIC (μg/ml) ofb: |

Site(s)c (no. of isolates) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TZP | CAZ | FEP | IPM | MEM | GEN | AMK | CIP | |||||

| 235 (n = 42) | O11 | I1–12 (21) | T1–11 (11), I1–4 (4), F1–2 (3), S1–2 (2), AD (1) | 16 to >256 | 16 to >128 | 16 to >128 | 0.5–1, 8–32 | 2–32 | 8 to >256 | 16–256 | ≥32 | CK (2), KC (3), PU (1), RI (1), VZ (3), ZD (1), ZG1 (2), ZG2 (2), ZG3 (2), ZG4 (2), ZG7 (1), ZG8 (1) |

| B1–10 (19) | B1–7 (13), W1–2 (2), Y1–2 (2), V (1), X (1) | 16 to >256 | 16 to >128 | 16 to >128 | 0.5–1, 8–128 | 4 to >64 | 32 to >256 | 16–128 | 8 to >32 | RI (8), SB (4), VZ (2), ZD (1), ZG1 (1), ZG3 (2), ZG4 (1) | ||

| N (1) | N (1) | 32 | >128 | 32 | 0.5 | 4 | >256 | 128 | 32 | ZG7 | ||

| P (1) | AB (1) | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | >64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | VZ | ||

| 111 (n = 15) | O12 | H1–11 (15) | U1–4 (5), Z1–5 (5), H1–2 (3), Q (1), AC (1) | 64 to >256 | 4 to >128 | 32 to >128 | 2–32 | 0.5–32 | 32 to >256 | 0.5–32 | 0.125, 2–32 | CK (1), RI (2), VT (1), VZ (1), ZD (1), ZG1 (6), ZG2 (3) |

| 132 (n = 11) | O6 | L1–4 (7) | L1–5 (5), P1–2 (2) | ≥256 | 8–128 | 64–128 | 16–32 | 32–64 | 128 to >256 | 16 | 32 to >32 | ZG1 (1), ZG2 (2), ZG3 (1), ZG5 (2), ZG6 (1) |

| E1–3 (3) | E1–3 (3) | ≥256 | 64–128 | 64 | 4–32 | 8–32 | 128–256 | 8–32 | 32 | ZG1 (1), ZG5 (1), ZG6 (1) | ||

| O (1) | O (1) | 256 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 32 | >256 | 32 | >32 | VZ | ||

| 621 (n = 9) | O4 | C1–5 | C1–7 | 64 to >256 | 4 to >128 | 8 to >128 | 1–2, 16–32 | 0.5 to >64 | ≥256 | 8–64 | ≥32 | KC (2), PU (1), RI (3), ZG1 (1), ZG2 (1), ZG3 (1) |

| 244 (n = 8) | O5 | A | A1–5 | 16, 128–256 | 8, 64 | 8–32 | 16–32 | 16–32 | 32–128 | 1–8 | 0.125–1, 16–32 | RI (6), ZG3 (2) |

| 292 (n = 8) | O12 | D1–3 | D1–2 | 32–256 | 32–64 | 16–64 | 8–16 | 32–64 | 128–256 | 8–16 | ≥32 | VZ (3), ZG1 (2), ZG3 (1), ZG4 (1), ZG5 (1) |

| 319 (n = 3) | O11 | Q | R | 128–256 | 64–128 | 32–64 | 16 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 2–4 | ZD |

| 175 (n = 2) | O4 | M | M | 128 | 8–16 | 16, 64 | 16, 128 | 16, 64 | >256 | 2, 128 | 32 | RI |

| 207 (n = 1) | O1 | F | AA | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 2 | 4 | 4 | CK |

| 308 (n = 1) | NTd | J | J | 8 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 64 | 128 | 4 | ZG1 |

| 633 (n = 1) | O6 | G | G | 256 | 128 | 64 | 16 | 16 | >256 | 8 | 0.25 | ZG4 |

| 966 (n = 1) | O4 | K | K | 256 | 128 | 64 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 64 | 1 | CK |

| MIC50 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 16 | 32 | ||||

XbaI and SpeI PFGE types were designated by letter symbols independently of each other.

TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; GEN, gentamicin; AMK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin. The MICs of netilmicin and norfloxacin are not shown for conciseness. Ranges of MICs refer to the situations in which all MICs between the two values were demonstrated by the study isolates. Two sets of MIC values indicate situations where the isolates of the same ST did not have all values in a range, e.g., ST244 isolates had CIP MICs of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 16, and 32 (MICs of 2, 4, and 8 were not demonstrated).

CK, Cakovec; KC, Koprivnica; PU, Pula; RI, Rijeka; SB, Slavonski Brod; VT, Virovitica; VZ, Varazdin; ZD, Zadar; ZG, Zagreb (ZG1 to ZG8 indicate 8 different hospitals in Zagreb).

NT, nontypeable.

The isolates were typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (18), using XbaI and SpeI restriction enzymes separately (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). PFGE types and subtypes were discerned visually using the criteria described by Tenover et al. (19). In order to construct dendrograms, banding patterns were analyzed with BioNumerics (version 6.01; Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium), using the Dice coefficient and clustering by the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means (1% tolerance in band position differences). With XbaI, the isolates were classified into 17 pulsotypes (Table 1), with the majority of isolates (53.9%) being clustered into 3 types, i.e., I, B, and H (21, 19, and 15 isolates, respectively). The SpeI analysis discerned 30 types that correlated well with those determined with XbaI (Table 1). Thirty isolates of all SpeI types were subjected to MLST (8); the P. aeruginosa MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/paeruginosa) was used to assign sequence types (STs). Twelve STs were identified (Table 1; also see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The most prevalent ST was ST235, with 42 isolates of 4 XbaI types (including types I and B) from 8 cities. ST111 comprised 15 more-homogeneous isolates (type H) from 6 cities, while ST132 included 11 isolates from 2 cities. The remaining 34 isolates were assigned to 9 STs, with 4 STs having single isolates. One of these, ST966, was a new single-locus variant (SLV) of ST111, classified into clonal complex 111 (CC111). Serotyping was performed using monoclonal O antigen-specific sera (Institute of Immunology, Zagreb, Croatia). Six serotypes were discerned (Table 1), and the 3 major clones, ST235, ST111, and ST132, represented serotypes O11, O12, and O6, respectively, as in previous studies (10, 11, 15).

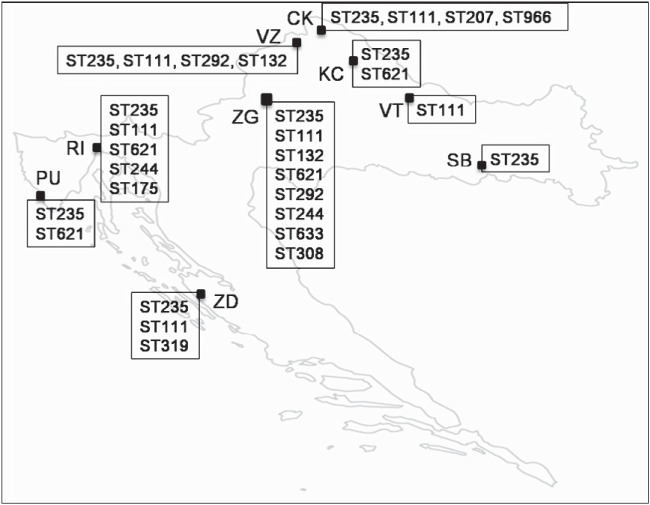

ST235, ST111, and ST132 accounted for 66.7% of the isolates, and a similar predominance of a few clones in MDR P. aeruginosa was observed in other countries (3, 11, 14, 20, 21). ST235 was the most common MDR clone (40.8%), spread mainly by 2 pulsotypes all over Croatia (Fig. 1). It has been ubiquitous worldwide and is associated with various resistance traits, including β-lactamases (3, 9–13, 22–25). In national surveys, ST235 was the most prevalent MDR clone in Japan (≥58.5%) and the Czech Republic (39%) (11), for example, and the second most prevalent in France (22%) (3). Enormous spread of MBL-producing ST235 has been observed in Russia over the 2000s (14). ST111 and CC111 have often been reported as well (3, 11, 15, 20, 22, 26, 27). ST111 has been prevalent among MDR P. aeruginosa isolates in France (11%) (3) and MBL producers in Greece; recently, MBL-positive ST111 has spread in the Netherlands (27). Its prominent role among MDR isolates in Croatia (15.5%) is due to the broad dissemination of a single pulsotype. The ST132 frequency in our work (10.7%) was comparable to that in the Czech study (10%) (11). Recently, P. aeruginosa isolates (82% MDR) from a hospital in Split, a Croatian city not included here, were analyzed; ST111 and ST235 were predominant, and ST111 was the most prevalent clone (22).

FIG 1.

Distribution of clones detected among MDR P. aeruginosa clinical isolates in Croatia. CK, Cakovec; KC, Koprivnica; PU, Pula; RI, Rijeka; SB, Slavonski Brod; VT, Virovitica; VZ, Varazdin; ZD, Zadar; ZG, Zagreb.

Three β-lactamase-mediated resistance mechanisms were analyzed, using all of the study isolates. Derepression of the natural AmpC enzyme (1, 2) was assessed by real-time PCR, using our own primers (Table 2), and interpreted as described previously (28). Forty-three isolates (41.7%) of various clones showed at least 10-fold higher levels of ampC mRNA than P. aeruginosa PAO1 (data not shown), indicating common overproduction. Class A ESBLs were detected by the double-disk synergy test (DDST), using ceftazidime as the substrate and clavulanate and imipenem as inhibitors, on plates without and with 250 μg/ml cloxacillin (AmpC inhibitor) (7). MBLs were detected by the DDST with imipenem and EDTA (29). Identification of various β-lactamase genes, including blaPER-1-like and blaGES-like ESBL genes and blaVIM-like MBL genes, was done by PCRs and sequencing (9, 12, 13, 30). Only 5 isolates of the entire collection were phenotypically positive for the β-lactamase types assessed, and all of those were confirmed to produce such enzymes by molecular analysis. Two isolates expressed ESBLs, i.e., one ST235 from Zagreb with PER-1 and one ST111 from Zadar with GES-7. Three ST235 isolates from different Zagreb sites produced MBLs; one isolate had VIM-1 and two related isolates had VIM-2. The presence of blaPER-1 in the transposon Tn1213 (31) was checked by PCR (12), and the results confirmed such context. Variable regions of class 1 integrons carrying blaGES-7, blaVIM-1, and blaVIM-2 genes were analyzed by PCR mapping and sequencing (30, 32, 33). In contrast to blaGES-7/IBC-1-carrying integrons in Greece (33), the blaGES-7 cassette was followed by aacA4, and PCRs of the 3′ part of the region based on sequences determined to date (33) have failed. The blaVIM-1 gene cassette array consisted of blaVIM-1-aacA4-aadA1 cassettes, followed by the 3′-CS segment. The blaVIM-2 integrons had aadB-aacA7-blaVIM-2-dhfrB5-aacA5 cassette arrays, adjacent to the tniC/R gene of the Tn402 transposition module (32). Links between PER-1, VIM-1, or VIM-2 enzymes and P. aeruginosa ST235 have often been reported (3, 9, 12, 14, 23, 24, 34, 35), and in Croatia these were rather occasional. This finding was congruent with those of the study from Split (22) and resembled findings for some other countries (3, 9). The integron with blaVIM-1 was In110, identified in Pseudomonas spp. in Italy and Spain (36, 37) and Enterobacteriaceae in Spain (32). The blaVIM-2 integron was new but differed from In559 only by the additional cassette aadB, suggesting direct evolution. In559 has been identified worldwide and is closely associated with ST235 spreading in Russia (14). Interestingly, the ST235 and ST111 isolates with VIM-2 that were identified previously in Split had a totally different integron (22).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Gene | Primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| rpsL | rpsL-1 | CCTGCTTACGGTCTTTGA | This study |

| rpsL-2 | TACATCGGTGGTGAAGGT | ||

| ampC | ampC-1 | ATACCAGATTCCCCTGCC | This study |

| ampC-2 | CTGAAGTAATGCGGTTCTC | ||

| mexA | mexA-1 | CATGCGTGTACTGGTTCCG | This study |

| mexA-2 | TTGAGGATGATGCCGTTCAC | ||

| mexC | mexC-1 | GGGTGAAATCCGCATAGAT | This study |

| mexC-2 | CAGCAGGACTTCGATACCG | ||

| mexE | mexE-1 | AACAGTCATCCCACTTCTC | This study |

| mexE-2 | AATTCGTCCCACTCGTTC | ||

| mexX | mexX-1 | CAGGTCGGAGAACAGCAG | This study |

| mexX-2 | GATCTACGTGAACTTCTCCC | ||

| oprD | oprD-F | CGCCGACAAGAAGAACTAGC | 39 |

| oprD-R | GTCGATTACAGGATCGACAG | ||

| oprD-F2 | GCCGACCACCGTCAAATCG | ||

| oprD-R2 | AAGTGGTGTTGCTGATGTC | This study | |

| gyrA | gyrA-F | AGTCCTATCTCGACTACGCGAT | 40 |

| gyrA-R | AGTCGACGGTTTCCTTTTCCAG | ||

| parC | parC-F | CGAGCAGGCCTATCTGAACTAT | 40 |

| parC-R | GAAGGACTTGGGATCGTCCGGA |

Twelve imipenem-resistant (MICs of 8 to 128 μg/ml) and 2 susceptible (MICs of 0.5 to 2 μg/ml) isolates of various STs (including 4 ST235, 4 ST111, and 2 ST132 isolates) were subjected to sequencing of the oprD gene, which encodes the porin responsible for imipenem uptake (1, 2). The results are shown in Table 3. A large sequence variety was observed, as seen previously (35). In 5 resistant isolates of ST111, ST235, and ST244, point mutations or frameshift mutations generated premature stop codons, remarkably reducing frames to 19, 65, 110, 138, or 233 codons (including stops). One ST308 isolate had the ISRP10 element inserted inside codon 69. Only the ST244 isolate with the premature stop at codon 138 had otherwise no mutations, compared to P. aeruginosa PAO1; all others, including the susceptible isolates, had many polymorphisms with unclear roles, as observed before in a Spanish study, for example (35). Four ST111 isolates had a set of 19 amino acid substitutions (from position 127 to position 424). Four ST235 isolates had 8 changes (from position 103 to position 315), while 4 isolates of ST132, ST175, and ST292 had 14 substitutions (from position 43 to position 359). Other changes found in Spain (35) occurred as well, namely, the distortion of amino acids 372 to 383 (“loop L7-short”) in ST111, ST132, ST175, and ST292 and a 1-nucleotide insertion at codon 402 in ST132, ST175, and ST235 isolates. Ten non-ciprofloxacin-susceptible (MICs of 2 to >32 μg/ml) and 2 susceptible (MICs of 0.125 to 0.25 μg/ml) isolates of a variety of STs were analyzed by sequencing the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) in the gyrA and parC genes (1); Table 3 shows the results. As expected, the nonsusceptible isolates had mutations in gyrA (amino acid substitutions T83I or D81N), either alone (MICs of 2 to 4 μg/ml) or together with mutations in parC (S87L/W; MICs of 8 to >32 μg/ml). The overexpression of 4 efflux pumps involved in resistance (1, 2) was studied by real-time PCR, using our own primers specific for genes mexA, mexC, mexE, and mexX (Table 2), in all of the study isolates and interpreted as described previously (28). Overexpression of mexC, mexA, and mexX occurred in 21 (20.4%), 11 (10.7%), and 4 (3.9%) isolates, respectively, while mexE showed borderline expression at the most (data not shown). These rates were relatively low in comparison with MDR isolates in French and Spanish studies (28, 38).

TABLE 3.

Sequencing analysis of oprD, gyrA, and parC genesa

| Isolate no.b | ST | IPM MIC (μg/ml) | OprD size | Amino acid polymorphisms in OprDc | Amino acid insertions/deletions in OprDc,d | CIP MIC (μg/ml) | Amino acid change in GyrA | Amino acid change in ParC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 111 | 2 | 441e | V127L, E185Q, P186G, V189T, E202Q, I210A, E230K, S240T, N262T, T276A, A281G, K296Q, Q301E, R310E, G312R, A315G, L347 M, S403A, Q424E | Loop L7-short | NP | ND | ND |

| 16 | 111 | 32 | 441e | V127L, E185Q, P186G, V189T, E202Q, I210A, E230K, S240T, N262T, T276A, A281G, K296Q, Q301E, R310E, G312R, A315G, L347 M, S403A, Q424E | Loop L7-short | NP | ND | ND |

| 6 | 111 | 32 | 18f | Q19STOP,g V127L,h E185Q,h P186G,h V189T,h E202Q,h I210A,h E230K,h S240T,h N262T,h T276A,h A281G,h K296Q,h Q301E,h R310E,h G312R,h A315G,h L347M,h S403A,h Q424Eh | Loop L7-shorth | NP | ND | ND |

| 33 | 111 | 32 | 109f | V127L,h E185Q,h P186G,h V189T,h E202Q,h I210A,h E230K,h S240T,h N262T,h T276A,h A281G,h K296Q,h Q301E,h R310E,h G312R,h A315G,h L347M,h S403A,h Q424Eh | 1-bp deletion at codon 108 (nt 323), stop codon 110, loop L7-shorth | NP | ND | ND |

| 20 | 132 | 32 | >443i | D43N, S57E, S59R, E202Q, I210A, E230K, S240T, N262T, A267S, A281G, K296Q, Q301E, R310G, V359L | Loop L7-short, 1-bp insertion at codon 402 (nt 1206), undetected stop codon | NP | ND | ND |

| 25 | 132 | 32 | >443i | D43N, S57E, S59R, E202Q, I210A, E230K, S240T, N262T, A267S, A281G, K296Q, Q301E, R310G, V359L | Loop L7-short, 1-bp insertion at codon 402 (nt 1206), undetected stop codon | NP | ND | ND |

| 30 | 175 | 128 | >443i | D43N, S57E, S59R, E202Q, I210A, E230K, S240T, N262T, A267S, A281G, K296Q, Q301E, R310G, V359L | Loop L7-short, 1-bp insertion at codon 402 (nt 1206), undetected stop codon | 32 | T83I | S87W |

| 26 | 292 | 8 | 441e | D43N, S57E, S59R, E202Q, I210A, E230K, S240T, N262T, A267S, A281G, K296Q, Q301E, R310G, V359L | Loop L7-short | NP | ND | ND |

| 2 | 235 (VIM-1) | 128 | >443i | T103S, K115T, F170L, E185Q, P186G, V189T, R310E, A315G | 1-bp insertion at codon 402 (nt 1206), undetected stop codon | NP | ND | ND |

| 29 | 235 | 0.5 | 443 | T103S, K115T, F170L, E185Q, P186G, V189T, R310E, A315G, G425A | NP | ND | ND | |

| 59 | 235 | 16 | 232f | T103S,h K115T,h F170L,h E185Q,h P186G,h V189T,h R310E,h A315G,h G425Ah | 13-bp deletion at codon 137 (nt 410–422) and 3-bp deletion at codon 142 (nt 425–427), stop codon 233 | NP | ND | ND |

| 61 | 235 | 32 | 64f | W65STOP,g T103S,h K115T,h F170L,h E185Q,h P186G,h V189T,h R310E,h A315G,h G425Ah | NP | ND | ND | |

| 64 | 244 | 32 | 137f | W138STOPg | 0.125 | |||

| 74 | 308 | 16 | —j | T103S,h K115T,h F170L,h E185Q,h P186G,h V189T,h R310E,h A315G,h G425Ah | ISRP10 insertion inside codon 69 (nt 205) | NP | ND | ND |

| 23 | 633 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 0.25 | ||

| 99 | 319 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 2 | D87N | |

| 1 | 111 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 4 | T83I | |

| 73 | 207 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 4 | T83I | |

| 49 | 235 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 8 | T83I | S87L |

| 4 | 235 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 32 | T83I | S87L |

| 45 | 292 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 32 | T83I | S87L |

| 48 | 244 | NP | ND | ND | ND | 32 | T83I | S87L |

| 75 | 621 | NP | ND | ND | ND | >32 | T83I | S87W |

| 84 | 132 | NP | ND | ND | ND | >32 | T83I | S87L |

IPM, imipenem; CIP; ciprofloxacin; NP, not presented; ND, not determined; nt, nucleotide(s).

The isolates used in the OprD analysis are ordered according to their STs, whereas the isolates used in the GyrA/ParC analysis are ordered according to increasing ciprofloxacin MICs; isolates 30 and 64 were used in both analyses and are shown in the OprD order.

Amino acid polymorphisms represent differences of the sequences obtained in this study from that of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain (GenBank accession no. AE004091).

Loop L7-short indicates modification of the amino acid stretch between position 372 and position 383 from MSDNNVGYKNYG to VDSSSSYAGL caused by several nucleotide changes (35).

The size of 441 amino acids is due to loop L7-short; the original stop codon is retained.

OprD protein sizes reduced by premature stop codons generated by point mutations.

Stop codons generated by point mutations.

Theoretical polymorphisms and loop L7-short, located either behind premature stop codons and/or within frames altered by insertions/deletions.

The size of >443 indicates situations in which insertions at the end of the oprD gene caused frameshifts and extension of the altered frames.

—, disruption of oprD by ISRP10 caused massive changes in the sequence; therefore, the size of a putative altered protein was not calculated.

This study assessed the clonal structure of MDR P. aeruginosa across Croatia. Together with the report from Split (22), it revealed the predominance of ST235 and ST111, adding also ST132. Since non-MDR isolates have not been analyzed, it is not clear whether these proportions reflected the overall rates in the P. aeruginosa population or concerned MDR organisms only. In the recent Czech and Spanish studies, however, MDR isolates were highly clonal, whereas susceptible isolates were diverse (11, 21). The analysis of selected resistance traits indicated that, while AmpC derepression and OprD and GyrA/ParC modifications were rather common, MBL and class A ESBL production and overexpression of efflux systems were of lower incidence. This means that other mechanisms, not assessed here and/or not yet known, must have played significant roles in the resistance of the study isolates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the integronic gene cassette arrays containing blaVIM-1 and blaVIM-2 appeared in the EMBL database under accession numbers KC140564 and KC175287, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to our colleagues from the Croatian Committee for Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance of the Croatian Academy for Medical Sciences for providing the bacterial isolates together with primary susceptibility data and patient information.

This study was partially financed by a FEMS research fellowship (grant FRF 2009-1) for M. Guzvinec. R. Izdebski, A. Baraniak, W. Hryniewicz, and M. Gniadkowski were partially supported by grant MIKROBANK from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 July 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03116-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poole K. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front. Microbiol. 2:65. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livermore DM. 2002. Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:634–640. 10.1086/338782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cholley P, Thouverez M, Hocquet D, Mee-Marquet N, Talon D, Bertrand X. 2011. Most multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from hospitals in eastern France belong to a few clonal types. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2578–2583. 10.1128/JCM.00102-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. 2009. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:582–610. 10.1128/CMR.00040-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2010. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:24–38. 10.1128/AAC.01512-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2005. Metallo-β-lactamases: the quiet before the storm? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:306–325. 10.1128/CMR.18.2.306-325.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weldhagen GF, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2003. Ambler class A extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel developments and clinical impact. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2385–2392. 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2385-2392.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curran B, Jonas D, Grundmann H, Pitt T, Dowson CG. 2004. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5644–5649. 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5644-5649.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giske CG, Libisch B, Colinon C, Scoulica E, Pagani L, Fuzi M, Kronvall G, Rossolini GM. 2006. Establishing clonal relationships between VIM-1-like metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from four European countries by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4309–4315. 10.1128/JCM.00817-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maatallah M, Cheriaa J, Backhrouf A, Iversen A, Grundmann H, Do T, Lanotte P, Mastouri M, Elghmati MS, Rojo F, Mejdi S, Giske CG. 2011. Population structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from five Mediterranean countries: evidence for frequent recombination and epidemic occurrence of CC235. PLoS One 6:e25617. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M, Musilek M. 2010. Multidrug-resistant epidemic clones among bloodstream isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Czech Republic. Res. Microbiol. 161:234–242. 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Empel J, Filczak K, Mrowka A, Hryniewicz W, Livermore DM, Gniadkowski M. 2007. Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections with PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Warsaw, Poland: further evidence for an international clonal complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2829–2834. 10.1128/JCM.00997-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viedma E, Juan C, Acosta J, Zamorano L, Otero JR, Sanz F, Chaves F, Oliver A. 2009. Nosocomial spread of colistin-only-sensitive sequence type 235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates producing the extended-spectrum β-lactamases GES-1 and GES-5 in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4930–4933. 10.1128/AAC.00900-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelstein MV, Skleenova EN, Shevchenko OV, D'Souza JW, Tapalski DV, Azizov IS, Sukhorukova MV, Pavlukov RA, Kozlov RS, Toleman MA, Walsh TR. 2013. Spread of extensively resistant VIM-2-positive ST235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia: a longitudinal epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13:867–876. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70168-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libisch B, Watine J, Balogh B, Gacs M, Muzslay M, Szabó G, Füzi M. 2008. Molecular typing indicates an important role for two international clonal complexes in dissemination of VIM-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates in Hungary. Res. Microbiol. 159:162–168. 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tambic Andrasevic A, Tambic T, Kalenic S, Jankovic V. 2002. Surveillance for antimicrobial resistance in Croatia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:14–18. 10.3201/eid0801.010143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 24th informational supplement. M100-S24 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seifert H, Dolzani L, Bressan R, van der Reijden T, van Strijen B, Stefanik D, Heersma H, Dijkshoorn L. 2005. Standardization and interlaboratory reproducibility assessment of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-generated fingerprints of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4328–4335. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4328-4335.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Castillo M, Del Campo R, Morosini MI, Riera E, Cabot G, Willems R, van Mansfeld R, Oliver A, Cantón R. 2011. Wide dispersion of ST175 clone despite high genetic diversity of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains in 16 Spanish hospitals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2905–2910. 10.1128/JCM.00753-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabot G, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Domínguez MA, Gago JF, Juan C, Tubau F, Rodríguez C, Moyà B, Peña C, Martínez-Martínez L, Oliver A, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI) 2012. Genetic markers of widespread extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk clones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:6349–6357. 10.1128/AAC.01388-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sardelic S, Bedenic B, Colinon-Dupuich C, Orhanovic S, Bosnjak Z, Plecko V, Cournoyer B, Rossolini GM. 2012. Infrequent finding of metallo-β-lactamase VIM-2 in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from Croatia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2746–2749. 10.1128/AAC.05212-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim MJ, Bae IK, Jeong SH, Kim SH, Song JH, Choi JY, Yoon SS, Thamlikitkul V, Hsueh P-R, Yasin RM, Lalitha MK, Lee K. 2013. Dissemination of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa of sequence type 235 in Asian countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:2820–2824. 10.1093/jac/dkt269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollini S, Maradei S, Pecile P, Olivo G, Luzzaro F, Docquier J-D, Rossolini GM. 2013. FIM-1, a new acquired metallo-β-lactamase from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate from Italy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:410–416. 10.1128/AAC.01953-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janvier F, Jeannot K, Tessé S, Robert-Nicoud M, Delacour H, Rapp C, Mérens A. 2013. Molecular characterization of blaNDM-1 in a sequence type 235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate from France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:3408–3411. 10.1128/AAC.02334-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edalucci E, Spinelli R, Dolzani L, Riccio ML, Dubois V, Tonin EA, Rossolini GM, Lagatolla C. 2008. Acquisition of different carbapenem resistance mechanisms by an epidemic clonal lineage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:88–90. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Bij AK, Van der Zwan D, Peirano G, Severin JA, Pitout JDD, Van Westreenen M, Goessens WHF. 2012. Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Netherlands: the nationwide emergence of a single sequence type. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:E369–E372. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabot G, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Tubau F, Macia MD, Rodriguez C, Moya B, Zamorano L, Suarez C, Pena C, Martinez-Martinez L, Oliver A. 2011. Overexpression of AmpC and efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from bloodstream infections: prevalence and impact on resistance in a Spanish multicenter study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1906–1911. 10.1128/AAC.01645-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee K, Lim YS, Yong D, Yum JH, Chong Y. 2003. Evaluation of the Hodge test and the imipenem-EDTA double-disk synergy test for differentiating metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4623–4629. 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4623-4629.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiett J, Baraniak A, Mrowka A, Fleischer M, Drulis-Kawa Z, Naumiuk L, Samet A, Hryniewicz W, Gniadkowski M. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of acquired-metallo-β-lactamase-producing bacteria in Poland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:880–886. 10.1128/AAC.50.3.880-886.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poirel L, Cabanne L, Vahaboglu H, Nordmann P. 2005. Genetic environment and expression of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase blaPER-1 gene in Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1708–1713. 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1708-1713.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tato M, Coque TM, Baquero F, Cantón R. 2010. Dispersal of carbapenemase blaVIM-1 gene associated with different Tn402 variants, mercury transposons, and conjugative plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:320–327. 10.1128/AAC.00783-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vourli S, Tzouvelekis LS, Tzelepi E, Lebessi E, Legakis NJ, Miriagou V. 2003. Characterization of In111, a class 1 integron that carries the extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene blaIBC-1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 225:149–153. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00510-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Libisch B, Poirel L, Lepsanovic Z, Mirovic V, Balogh B, Pászti J, Hunyadi Z, Dobák A, Füzi M, Nordmann P. 2008. Identification of PER-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates of the international clonal complex CC11 from Hungary and Serbia. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 54:330–338. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rojo-Bezares B, Estepa V, Cebollada R, de Toro M, Somalo S, Seral C, Castillo FJ, Torres C, Sáenz Y. 2014. Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from a Spanish hospital: characterization of metallo-beta-lactamases, porin OprD and integrons. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304:405–414. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossolini GM, Luzzaro F, Migliavacca R, Mugnaioli C, Pini B, De Luca F, Perilli M, Pollini S, Spalla M, Amicosante G, Toniolo A, Pagani L. 2008. First countrywide survey of acquired metallo-β-lactamases in Gram-negative pathogens in Italy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4023–4029. 10.1128/AAC.00707-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juan C, Beceiro A, Gutiérrez O, Albertí S, Garau M, Pérez JL, Bou G, Oliver A. 2008. Characterization of the new metallo-β-lactamase VIM-13 and its integron-borne gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3589–3596. 10.1128/AAC.00465-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hocquet D, Berthelot P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Favre R, Jeannot K, Bajolet O, Marty N, Grattard F, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Bingen E, Husson M-O, Couetdic G, Plésiat P. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa may accumulate drug resistance mechanisms without losing its ability to cause bloodstream infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3531–3536. 10.1128/AAC.00503-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutierrez O, Juan C, Cercenado E, Navarro F, Bouza E, Coll P, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2007. Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Spanish hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4329–4335. 10.1128/AAC.00810-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akasaka T, Tanaka M, Yamaguchi A, Sato K. 2001. Type II topoisomerase mutations in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in 1998 and 1999: role of target enzyme in mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2263–2268. 10.1128/AAC.45.8.2263-2268.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.