Abstract

Pharmacopeial recommendations for administration of antimalarial drugs are the same weight-based (mg/kg of body weight) doses for children and adults. However, linear calculations are known to underestimate pediatric doses; therefore, interspecies allometric scaling data may have a role in predicting doses in children. We investigated the allometric scaling relationships of antimalarial drugs using data from pharmacokinetic studies in mammalian species. Simple allometry (Y = a × Wb) was utilized and compared to maximum life span potential (MLP) correction. All drugs showed a strong correlation with clearance (CL) in healthy controls. Insufficient data from malaria-infected species other than humans were available for allometric scaling. The allometric exponents (b) for CL of artesunate, dihydroartemisinin (from intravenous artesunate), artemether, artemisinin, clindamycin, piperaquine, mefloquine, and quinine were 0.71, 0.85, 0.66, 0.83, 0.62, 0.96, 0.52, and 0.40, respectively. Clearance was significantly lower in malaria infection than in healthy (adult) humans for quinine (0.07 versus 0.17 liter/h/kg; P = 0.0002) and dihydroartemisinin (0.81 versus 1.11 liters/h/kg; P = 0.04; power = 0.6). Interpolation of simple allometry provided better estimates of CL for children than MLP correction, which generally underestimated CL values. Pediatric dose calculations based on simple allometric exponents were 10 to 70% higher than pharmacopeial (mg/kg) recommendations. Interpolation of interspecies allometric scaling could provide better estimates than linear scaling of adult to pediatric doses of antimalarial drugs; however, the use of a fixed exponent for CL was not supported in the present study. The variability in allometric exponents for antimalarial drugs also has implications for scaling of fixed-dose combinations.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization and standard pharmacopeial sources recommend that antimalarial drugs be administered at the same weight-based (mg/kg of body weight) or linear dose for children and adults (1). However, this linear method of dosage calculation is known to underestimate the optimum pediatric dose of many drugs (2–5). Recent clinical reports indicate that higher doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (6, 7), chloroquine (6, 8, 9), quinine (10), piperaquine (11–14), and artesunate (15, 16) are required for effective antimalarial therapy in children.

Allometric scaling is a well-established technique for relating physiological or pharmacokinetic parameters to body weight (17–22), and allometric relationships have been demonstrated for a wide range of drugs, including antimicrobial agents (23–27). The conventional applications of interspecies allometric scaling include prediction of human doses by extrapolation from preclinical animal studies and dose estimates for other mammalian species in veterinary medicine (18, 23, 26, 28). Increasing interest has been shown in the application of interspecies allometric scaling data to predict pharmacokinetic parameters or drug doses in children (27, 29, 30). Despite a paucity of reports on antimalarial drugs (31, 32), interpolation of allometric scaling of chloroquine supports recommendations from clinical studies for higher chloroquine doses in children (8, 9, 33).

The rationale for using scaling techniques to estimate pharmacokinetic parameters in children is that relatively few pediatric pharmacokinetic investigations are conducted, compared to adult studies, and sparse sampling is normally required because there are practical and ethical limitations to obtaining rich pharmacokinetic data sets from pediatric subjects (34). One alternative to conventional interspecies scaling is fixed-exponent scaling from human adult pharmacokinetic data (2–5, 34–37). The principle of scaling with a fixed exponent (e.g., 2/3 or 3/4) may provide some consistency and practical advantages; however, the validity of a universal exponent in pharmacokinetics is subject to conflicting evidence and debate (3, 5, 27, 34–40). Regardless of the scaling method that is used, caution is required for recommendations for very young children, due to immature clearance mechanisms, and for disease states for which there are limited data available or evidence that clearance may be altered in compromised patients (30, 35, 36).

We sought to investigate the allometric scaling relationships of antimalarial drugs using data from pharmacokinetic studies of healthy and malaria-infected mammalian species. Our hypothesis was that linear scaling (i.e., exponent of 1.0) would not apply and that interpolation of interspecies allometric scaling would be suitable for estimating pediatric doses of antimalarial drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted via PubMed, OvidSP, Google Scholar, and citation records, using relevant key words, including the specific antimalarial drugs and mammalian species. The initial target list of antimalarial drugs was determined from WHO treatment guidelines (1): artemisinin, artesunate, artemether, dihydroartemisinin, mefloquine, amodiaquine, piperaquine, chloroquine, quinine, primaquine, lumefantrine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, atovaquone, proguanil, tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. Exclusions comprised fixed-dose combinations where data for individual drugs were not readily available (sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, artemether-lumefantrine, atovaquone-proguanil), drugs for which pharmacokinetic data were available from fewer than three mammalian species (amodiaquine and lumefantrine), and drugs that are contraindicated in children (tetracycline and doxycycline). Chloroquine (33) and doxycycline (41) had been studied previously and were excluded.

The pharmacokinetic studies were screened for suitability of the data, with a focus on uniformity of biological matrix (especially for quinolines with high blood-plasma ratio), period over which blood and plasma samples were collected for the pharmacokinetic study (preferably >3 half-lives), route of administration, and use of validated analytical methods. Although pharmacokinetic parameters from studies with intravenous (or parenteral) drug administration are preferred for allometric scaling, other routes of administration were more appropriate for some antimalarials, such as those which are available only as oral formulations. The final list of drugs (and routes of administration) was as follows: artemisinin (intravenous [IV], intraperitoneal, and oral), artesunate (IV) and the active artemisinin metabolite dihydroartemisinin (from IV artesunate), artemether (IV and intramuscular), mefloquine (oral), piperaquine (oral), quinine (IV), and clindamycin (IV).

Pharmacokinetic parameters.

Clearance (CL), volume of distribution during terminal phase (Vz), and half-life (t1/2) data were collated or determined from the available data using model-independent equations (CL = k × V; Vz = CL/k). Comprehensive pharmacokinetic data (e.g., mean residence time [MRT] and steady-state volume of distribution [Vss]) were reported in a limited range of studies and therefore were not included in the present analysis. In studies where different doses were administered to the same subjects and there was no evidence of dose-dependent variability, the mean value of the pharmacokinetic parameter was used. However, if separate groups were given different doses within a study, the data were treated independently except when the results were reported as group data. In human studies where body weight was not reported, 60 kg was used for Asian and African subjects, whereas 70 kg was used for Caucasian subjects, based on standard references and other reports used in the present study. The body weight of animals was not provided in some nonhuman studies; hence, published standard body weights of the respective species were used for the allometric scaling (17, 25, 28, 42).

Allometric scaling.

Simple allometry was the principal method of interspecies scaling, using the equation

| (1) |

where Y is the pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., CL or Vz), W is the body weight of the species, a is the coefficient, and b is the allometric exponent (19, 24, 38).

The pharmacokinetic parameter data were plotted against body weight on a log-log scale (SigmaPlot version 12.5; Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL) to determine the allometric coefficient and exponent by regression analysis.

Data from healthy control subjects were used for the allometric scaling, as there were insufficient pharmacokinetic studies in malaria-infected nonhuman species for each antimalarial drug that was investigated. However, pharmacokinetic parameters from human (adults) studies of malaria infection were compared to the healthy-control data, as a guide to the application of allometric interpolation to decisions on pediatric doses.

Maximum life span potential (MLP) correction.

Several alternative methods of scaling and use of correction factors have been proposed and reviewed (17–19, 26, 43, 44), although the physiological relevance and application of some methods were not applicable in the present study. The most relevant and best-studied method for our consideration was MLP correction, which is an integral feature of the “rule of exponents” approach (26, 44). According to the rule of exponents, simple allometry is the best predictor for exponents in the range from 0.50 to 0.70, whereas CL × MLP provides the best prediction method when the range is 0.71 to 0.99 (44). As the CL exponent from simple allometry was <1 for all antimalarial drugs, we compared MLP correction to simple allometry.

The maximum life span potential (MLP) was calculated from the equation (17)

| (2) |

where BW is brain weight in grams and B is body weight in grams (the coefficient 10.839 is replaced with 185.5 if the brain and body weights are in kg [44]). Brain and body weight data for mammalian species are well established (17, 42, 45).

The CL × MLP data were plotted against body weight on a log-log scale (SigmaPlot) to determine the coefficient and exponent by regression analysis. Clearance exponents from simple allometry and MLP correction were used to determine interpolated CL for children and compared to available clinical study data.

Pediatric doses.

A standard allometric model for pediatric dosing is to use one of the following equations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where dosechild is the total dose for a child at the specified weight (weightchild), doseadult is the standard total dose for an adult at the specified weight (weightadult), and CLchild and CLadult are the total CL of the drug.

The exponent derived by allometric scaling (equation 1) was applied in the present study (equation 3) to compare calculated doses to pharmacopeial or reference doses for arbitrary weights of 15 kg and 25 kg (children approximately 4 and 8 years of age, respectively). Dose estimates for children less than 2 years were not considered, due to the known physiological and pharmacokinetic differences between very young infants and adults (35, 36).

Statistical analyses.

Data analysis and representation were performed with SigmaPlot version 12.5 (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL). Data are means ± standard deviations (SD) unless otherwise indicated. The 95% confidence interval (CI) was determined for the allometric exponent [95% CI = mean ± (1.96 × standard error)]. The Student t test was used for two-sample comparison as appropriate, with significance at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Simple allometry.

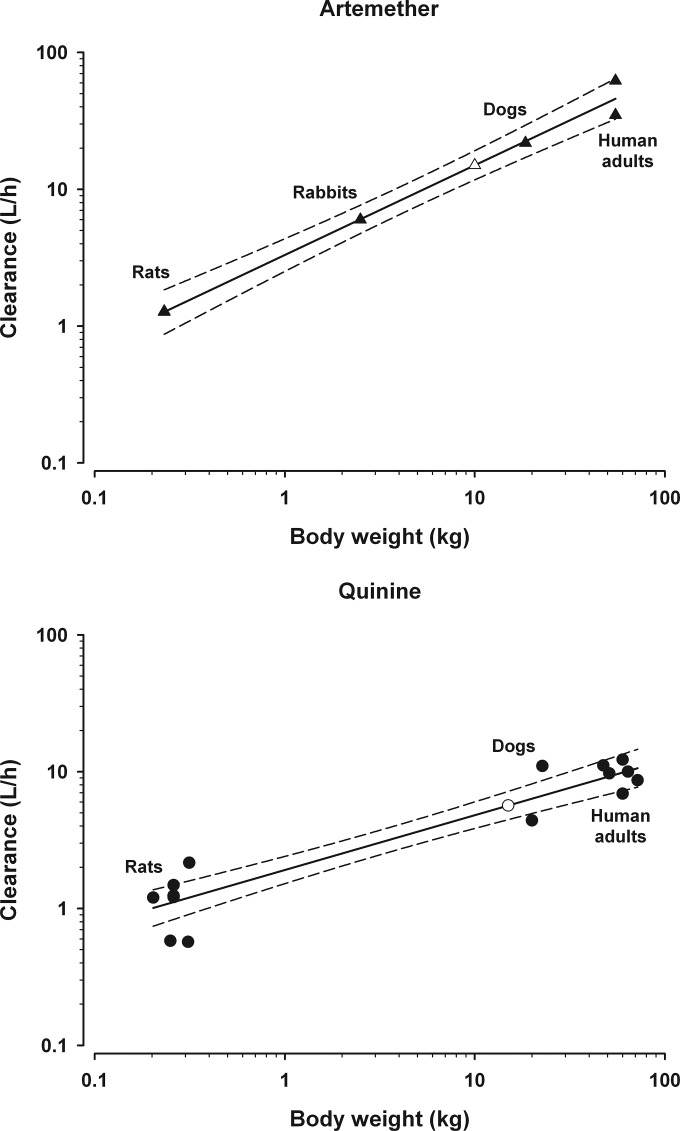

Simple allometric scaling data for CL and Vz are shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. A strong correlation was found for both CL and Vz for all antimalarials except Vz for the prodrug artesunate (Tables 1 and 2). Artemether (Fig. 1) is normally administered by intramuscular injection, but the inclusion of IV data from a rodent and rabbit study did not significantly alter the allometric parameters. Artemisinin was given parenterally in the studies of mice and rats, but as oral administration was used in human studies, CL data were corrected for oral bioavailability to facilitate scaling (Table 1). Due to the mixed sources of data, artemisinin was excluded from subsequent analyses.

TABLE 1.

Simple allometric scaling data for clearance (CL) of antimalarial drugs in healthy mammals

| Drug | Route of administrationa | No. of speciesb | r2 | Allometric exponent (95% CI) | Allometric coefficient | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artesunate | IV | 4 (r, d, p, h) | 0.92 | 0.71 (0.53–0.88) | 7.0 | 55, 58–62 |

| Dihydroartemisinin (from IV artesunate) | IV | 4 (r, d, p, h) | 0.94 | 0.85 (0.68–1.03) | 3.3 | 55, 58–63 |

| Artemether | IM | 3 (r, d, h) | 0.98 | 0.66 (0.38–0.93) | 3.3 | 59, 64–66 |

| Artemether | IM or IV | 4 (r, rb, d, h) | 0.99 | 0.66 (0.56–0.75) | 3.3 | 59, 64–67 |

| Artemisinin | IV, IP, oral×Fc | 3 (m, r, h) | 0.92 | 0.83 (0.69–0.96) | 4.2 | 68–79 |

| Clindamycin | IV | 3 (d, r, h) | 0.98 | 0.62 (0.55–0.69) | 1.4 | 80–87 |

| Piperaquine | Oral | 3 (m, r, h) | 0.99 | 0.96 (0.86–1.05) | 1.6 | 88–92 |

| Mefloquine | Oral | 3 (m, r, h) | 0.90 | 0.52 (0.43–0.61) | 0.2 | 93–110 |

| Quinine | IV | 3 (r, d, h) | 0.89 | 0.40 (0.33–0.47) | 1.9 | 111–123 |

IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular; IP, intraperitoneal.

Species: m, mouse; r, rat; d, dog; p, pig; rb, rabbit; h, human.

Artemisinin dose was corrected for relative oral bioavailability (oral:intramuscular); F = 0.32 (78).

TABLE 2.

Simple allometric scaling data for volume of distribution (Vz) of antimalarial drugs in healthy mammals

| Drug | Route of administrationa | No. of speciesb | r2 | Allometric exponent (95% CI) | Allometric coefficient | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artesunate | IV | 4 (r, d, p, h) | 0.69 | 0.54 (0.22–0.85) | 3.2 | 55, 58–62 |

| Dihydroartemisinin (from IV artesunate) | IV | 4 (r, d, p, h) | 0.99 | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | 4.2 | 55, 58–63 |

| Artemether | IM | 3 (r, d, h) | 0.99 | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 12.4 | 59, 64–66 |

| Artemether | IM or IV | 4 (r, rb, d, h) | 0.96 | 1.06 (0.75–1.38) | 6.7 | 59, 64–67 |

| Clindamycin | IV | 3 (d, r, h) | 0.98 | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 2.5 | 80–86 |

| Piperaquine | Oral | 3 (m, r, h) | 0.94 | 1.16 (0.87–1.45) | 280 | 88–92 |

| Mefloquine | Oral | 3 (m, r, h) | 0.91 | 0.78 (0.66–0.90) | 39.8 | 93–110 |

| Quinine | IV | 4 (r, rb, d, h) | 0.92 | 0.88 (0.74–1.01) | 4.61 | 111–124 |

IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular.

Species: m, mouse; r, rat; d, dog; p, pig; rb, rabbit; h, human.

FIG 1.

Simple allometric scaling relationship with 95% confidence interval (---) for CL of artemether and quinine. Artemether scaling (top) comprised data from 5 studies (▲). The scaled estimate of CL for a 10-kg child (△) was 1.5 liters/h/kg. By comparison, the mean adult CL is 0.88 liter/h/kg (Table 3), the estimated CL based on a fixed exponent of 3/4 is 1.4 liters/h/kg, and the CL from one clinical study in children (9.5 kg) was 1.5 liters/h/kg (150). Quinine scaling (bottom) comprised data from 12 studies (●). The scaled estimate of CL for a 15-kg child (○) was 0.37 liter/h/kg. By comparison, the mean adult CL is 0.17 liter/h/kg (Table 3), the estimated CL based on a fixed exponent of 3/4 is 0.25 liter/h/kg, and the CL from one clinical study in children (15 kg) was 0.24 liter/h/kg (118).

The 95% CI for CL of piperaquine, mefloquine, and quinine did not encompass 2/3 or 3/4, hence the application of these fixed exponents could not be supported by the present data (Table 1, Fig. 1). Linear dosing of piperaquine could be supported, based on the 95% CI for CL in the present analysis (Table 1).

The 95% CI for Vz encompassed unity for three of the seven drugs: artemether, piperaquine, and quinine (Table 2). Volume of distribution is normally used in calculations of loading dose and in pharmacokinetic modeling; therefore, no further analysis of Vz was undertaken for the purposes of the present study.

Control versus malaria.

In the absence of pharmacokinetic data from malaria-infected nonhuman species for each antimalarial drug, a direct comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters from human (adult) healthy controls and malaria-infected patients was performed (Table 3). Artesunate could be excluded on the basis that dose predictions according to the active metabolite dihydroartemisinin may be more appropriate. Apart from quinine and dihydroartemisinin, which showed significantly lower CL in malaria infection than in healthy controls, the P values were >0.1 and the power of the analyses were <30% for the other antimalarial drugs. Despite limited data, it was also apparent that CL of quinine in malaria infected children is likely to be significantly lower than CL in healthy controls (Table 3). The power of the analysis for dihydroartemisinin CL was <80%; hence, a type I error cannot be excluded in the present study.

TABLE 3.

Clearance of antimalarial drugs in malaria-infected patients compared to healthy adults

| Drug | Route of administrationa | CL (liters/h/kg) (no.of groupsb) |

Healthy vs. malaria |

Referencesb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Malaria | P value | Power | |||

| Artesunate | IV | 1.9 ± 0.6 (3) | 2.9 ± 0.8 (8) | 0.09 | 0.4 | 55, 60, 62, 125–130 |

| Dihydroartemisinin (from IV artesunate) | IV | 1.11 ± 0.16 (3) | 0.81 ± 0.2 (8) | 0.04 | 0.56 | 55, 60, 62, 125–131 |

| Artemether | IM | 0.88 ± 0.35 (2) | 1.8 ± 0.9 (2) | 0.32 | 0.13 | 64, 65, 132, 133 |

| Piperaquinec | Oral | 0.86 ± 0.65 (6) | 1.55 ± 0.73 (4) | 0.15 | 0.28 | 56, 88, 90, 91, 134–137, 154 |

| Mefloquine | Oral | 0.030 ± 0.014 (17) | 0.039 ± 0.014 (5) | 0.24 | 0.21 | 94–109, 138, 139 |

| Quinine | IV | 0.17 ± 0.05 (6) | 0.07 ± 0.03 (9) | 0.0002 | 0.99 | 112, 114–117, 122, 140–145 |

| Quinine (children) | IV | 0.24 (1) | 0.064 ± 0.014 (5) | NAd | NA | 118, 146, 147 |

IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular.

Data are means ± SD. Some studies comprised several groups.

Piperaquine studies included piperaquine alone and piperaquine-dihydroartemisinin data for healthy volunteers, but only piperaquine-dihydroartemisinin data for patients with malaria. Our data and a previous report (148) indicate that there is no significant difference in piperaquine clearance when administered alone or in combination with dihydroartemisinin.

NA, not applicable.

MLP correction.

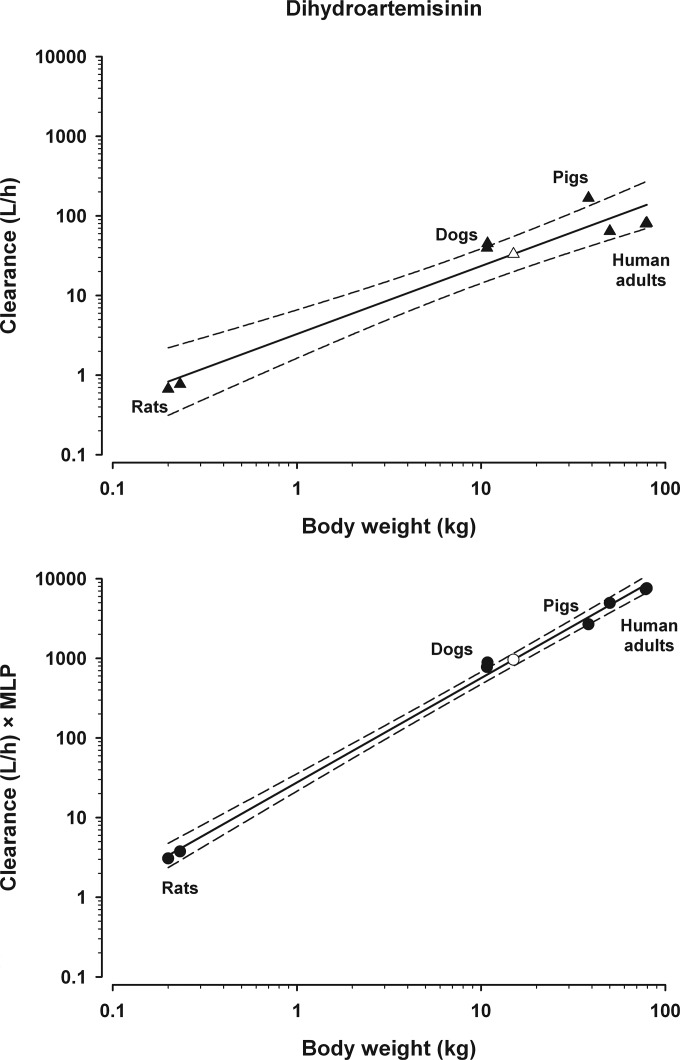

The MLPs for mice, rats, rabbits, dogs, pigs, human adults, 15-kg children, and 25-kg children were 2.7, 4.8, 8.7, 20, 16, 93, 109, and 106 years, respectively. The effect of MLP correction is therefore to multiply CL 3- to 5-fold in rodents, 16- to 20-fold in dogs, pigs, sheep, and cows (17), 35-fold in horses, 93-fold in adult humans, and >100-fold in human children. The result was that scaling extended over four orders of magnitude (Fig. 2). Compared to simple allometry (Table 1), the r2 for MLP-corrected scaling of CL for dihydroartemisinin (0.99), mefloquine (0.96), and quinine (0.98) improved, but the r2 for artemether (0.98), clindamycin (0.96), and piperaquine (0.99) was similar or slightly lower.

FIG 2.

Allometric scaling relationship for clearance of dihydroartemisinin. (Top) Simple allometric scaling of data from 7 studies (▲). The scaled estimate of CL for a 15-kg child (△) was 2.2 liters/h/kg. By comparison, the mean adult CL is 1.1 liters/h/kg (Table 3), the estimated CL based on a fixed exponent of 3/4 is 1.6 liters/h/kg, and the CL from one clinical study in children (13 kg) was 2.2 liters/h/kg (149). (Bottom) CL × MLP correction (y axis) for the same 7 studies (●). The scaled estimate of CL for a 15-kg child (○) is 0.53 liter/h/kg.

The effect of MLP correction on interpolated prediction of CL in children, compared to simple allometry, is shown in Table 4. Results for interpolation of simple allometry for artemether and quinine are illustrated in Fig. 1, with interpolation at 10 kg and 15 kg, respectively, to facilitate comparison with clinical study data (Table 4). Dihydroartemisinin scaling by both simple allometry and MLP correction is provided in Fig. 2. Predictions based on simple allometry were close to the results from clinical studies of dihydroartemisinin and artemether, albeit in children with malaria infection (Table 4). In contrast, simple allometry showed an overestimation of CL for mefloquine and quinine. It was observed that MLP correction routinely underestimated CL (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Antimalarial drug clearance from clinical studies in children compared to interpolated CL from simple allometry and MLP correction

| Drug | Allometric exponenta |

Interpolated CL (liters/h/kg)a |

Clinical studyb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple allometry | MLP correction | Simple allometry | MLP correction | CL (liters/h/kg) | Wt (kg) | Reference | |

| Dihydroartemisinin | 0.85 | 1.31 | 2.21 | 0.48 | 2.16 | 13 | 149 |

| Artemether | 0.66 | 1.18 | 1.52 | 0.35 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 150 |

| Piperaquine | 0.96 | 1.46 | 1.40 | 0.50 | 1.85c | 16 | 56 |

| Piperaquine | 0.96 | 1.46 | 1.39 | 0.57 | 0.85c | 19.1 | 57 |

| Mefloquine | 0.52 | 1.0 | 0.068 | 0.023 | 0.046d | 9.5e | 151 |

| Mefloquine | 0.52 | 1.0 | 0.068 | 0.023 | 0.048d | 9.5e | 152 |

| Mefloquine | 0.52 | 1.0 | 0.045 | 0.024 | 0.026d | 23 | 153 |

| Quininef | 0.40 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 15.4 | 118 |

Allometry was conducted in healthy controls; CL/F was determined for piperaquine and mefloquine.

Data from studies in malaria-infected children; CL/F was determined for piperaquine and mefloquine.

Piperaquine CL/F was determined from studies of piperaquine-dihydroartemisinin in malaria-infected children. There is no significant difference in piperaquine clearance when piperaquine is administered alone or in combination with dihydroartemisinin (148). One recent study reported a CL/F of 0.57 liter/h/kg; however, the data were pooled from a previous study of piperaquine-dihydroartemisinin (57) and an investigation of piperaquine-artemisinin (12). A report of a piperaquine CL/F of 0.42 liter/h/kg from capillary blood samples could not be compared directly to investigations using venous plasma samples for determination of piperaquine pharmacokinetic parameters (13).

Mefloquine CL/F was determined from studies of mefloquine-sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in malaria-infected children. Mefloquine clearance may be lower when mefloquine is administered in combination with sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine (101).

Malaria-infected children were all <2 years of age in these studies; the mean age was 1.6 years.

All quinine data are from studies in healthy controls.

Pediatric doses.

Pediatric dose calculations were based on pharmacopoeial (mg/kg) recommendations (1) and were 10 to 70% higher, according to allometric predictions (Table 5). Mefloquine and quinine had the lowest exponent, which led to predictions 1.6- to 2.5-fold higher than reference doses.

TABLE 5.

Allometric interpolation of antimalarial doses in comparison to current pharmacopeial recommendations

| Drug | Route of administration | Standard regimena | Dose (mg) for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-kg child |

25-kg child |

|||||

| Referenceb | Allometryc | Referenceb | Allometryc | |||

| Dihydroartemisinin (as IV artesunate) | IV | Dose at 0, 12, 24 h, then once/day (2.4 mg/kg/dose) | 35 | 45 | 60 | 70 |

| Artemetherd | Oral | Twice/day for 3 days | 40 | 30 | 60 | 40 |

| Clindamycin | Oral | Twice/day for 7 days (10 mg/kg/dose) | 150 | 260 | 250 | 360 |

| Piperaquine | Oral | Once/day for 3 days (18 mg/kg/day) | 270 | 290 | 450 | 470 |

| Mefloquine | Oral | 2/3 total dose day 1; 1/3 total dose day 2 (25-mg/kg total dose) | 375 | 790 | 625 | 1,025 |

| Quinine | IV | Three times per day for 5–7 days (10 mg/kg/dose) | 150 | 370 | 250 | 460 |

As reported by the World Health Organization (1) and confirmed by reference to the British National Formulary.

Based on mg/kg doses and practical recommendations.

Based on reference doses and equation 3, where adult dose was according to a 70-kg body weight and the allometric exponent was from Table 1. Doses were mostly rounded to a 10-mg increment rather than the nearest practical dose.

Current artemether dose recommendation is for body weight range (1, 2, 3, and 4 20-mg tablets for patients weighing 5 to 14 kg, 15 to 24 kg, 25 to 34 kg, and >34 kg, respectively). The adult (70 kg) dose is therefore the same as that for a child of 34 kg (80 mg), which equates to 1.1 mg/kg for adults and 2.3 mg/kg for the 34-kg child. Hence, current practical dose recommendations are higher (mg/kg) for children and vary within the weight ranges.

Although quinine CL is significantly lower in malaria infection than in healthy controls and data presented in Table 3 suggest that quinine CL is lower in malaria-infected children than in adults (contrary to allometric principles), the allometric exponent for quinine CL (Table 1) was used in the present analysis. Cautious interpretation of the result for quinine is therefore required. However, increased doses for dihydroartemisinin (as IV artesunate), clindamycin, and mefloquine appear to be warranted (a piperaquine dose increase would likely not be clinically relevant or practical).

DISCUSSION

The present study has demonstrated that interpolation of interspecies allometric scaling could be a useful strategy to include in development and refinement of pediatric doses for antimalarial drugs. We found strong allometric relationships for seven drugs (dihydroartemisinin, artemether, artemisinin, clindamycin, piperaquine, mefloquine, and quinine) and showed that linear scaling of clearance is not applicable, although the 95% confidence intervals spanned unity for dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine (Table 1). In contrast, linear scaling of the volume of distribution appeared to be valid for some drugs, notably artemether and piperaquine (Table 2).

Allometric scaling is founded on sound theoretical principles and evidence of a power law relationship between biological parameters and body weight; however, there are conflicting reports on the application of fixed exponents and correction factors (20, 35, 36, 38–40, 46, 47). Historical research on basal metabolic rate established a 2/3 power scaling of body mass and is supported by the concept of scaling surface area to volume of 3-dimensional objects (20, 39). The “1/4 power law” is based on seminal studies that scaled the metabolic rate of animals using an exponent of 3/4 and is reported to be consistent with structure and function observations in biology (20, 21, 38, 39). This power law has been translated to the use of an exponent of 3/4 for drug clearance, 1/4 for elimination half-life, and 1 for volume of distribution (21, 22, 35, 36, 38, 39). It has recently been argued that the small numerical difference between 2/3 and 3/4 powers is of little clinical relevance in pharmacokinetics (36).

The physiological origins of interspecies relationships provide some context for the limitations of allometric scaling in pharmacokinetics, which have been the subject of detailed review (39, 48–50). One limitation of scaling pharmacokinetic parameters that we encountered was a small range of mammalian species and low number of subjects in each study (typically 6 to 16 in human studies and 6 to 8 in other species). We were able to obtain data from only two or three nonhuman species, a finding that is consistent with similar previous investigations (24, 31, 33). However, some pharmacokinetic studies, especially veterinary reports, were compiled with data from at least 8 species (17, 19, 23, 51), and interspecies scaling of physiological parameters, such as basal metabolic rate, comprises data from over 20 species (21). A larger range of animal studies would therefore enhance the quality of allometric scaling data in future studies.

Further limitations may occur if there are species differences in the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs that lead to unpredictable and weak allometric scaling outcomes (39, 49, 50). Highly protein-bound drugs (>98% in humans), such as mefloquine (52) and piperaquine (53), may have inconsistent scaling if binding is substantially lower in other species. Bioavailability and renal or hepatic clearance mechanisms also may have species differences which could be relevant for antimalarial drugs that are subject to hepatic metabolism and commonly administered as oral formulations. However, there is generally a paucity of relevant data to address these potential limitations in the scaling of pharmacokinetic parameters (49, 50).

Notwithstanding the limitations of interspecies scaling and the power law relationship debate, allometric scaling data indicate that fixed exponents of 2/3 or 3/4 may not be universally applicable in pharmacokinetics (24, 28, 29, 31, 33, 38, 44, 47). Our analyses showed that the 95% CI encompassed both 2/3 and 3/4 for CL of artemether and artemisinin, whereas the upper limit of the 95% CIs for mefloquine, quinine, and chloroquine (0.63, based on reanalysis of a previous study [33]) were all <0.65 (Table 1). In contrast, the allometric exponents for dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine CL were 0.85 and 0.96, respectively, and the 95% CI of the exponent spanned unity. Hence, the use of a fixed exponent for CL of antimalarial drugs is not supported by the present study.

The influence of allometric exponents on interpolated dose predictions can be substantial and varies according to body weight. For example, if the recommended adult dose of a drug is 10 mg/kg (for a 70-kg adult), arbitrary exponents of 0.6 and 0.75 would lead to predicted doses of 18.5 mg/kg and 14.7 mg/kg, respectively, for a 15-kg child and of 15.1 mg/kg and 12.9 mg/kg, respectively, for a 25-kg child. The differential between adult and child doses will decrease for children with higher body weights and will also decrease as the exponent approaches unity. The potential effect of these inverse relationships on dose predictions demonstrates the importance of high-quality data for allometric scaling.

It was evident from our detailed literature search that an extensive range of interspecies scaling for antimalarial drugs was precluded by several factors. In particular, the target list of antimalarials was limited by a paucity of data for individual drugs within some common, fixed-dose combinations, and we could not obtain pharmacokinetic data from a minimum of three mammalian species for amodiaquine and lumefantrine. Studies with intravenous (or parenteral) drug administration would have been optimal, but inclusion of other routes of administration was necessary for artemisinin, artemether, mefloquine, and piperaquine. An important issue was the small body of pharmacokinetic research in malaria-infected nonhuman species for the antimalarial drugs, and this limitation was addressed by comparing drug clearance from studies in malaria-infected human adults with that reported for healthy controls (Table 3). Consistent with previous reports, only quinine was shown conclusively to have significantly different clearance in malaria infection (54). Our data indicate that dihydroartemisinin clearance was higher in healthy controls than patients with malaria infection (Table 3); however, the power of the analysis was inconclusive. The apparent clearance (CL/F) of piperaquine and mefloquine could be higher in malaria infection than in healthy controls (Table 3) and may be a function of altered bioavailability, as has been reported for dihydroartemisinin (55).

Our investigation of the relevance of correction factors for allometric scaling was to ascertain if the more sophisticated approaches to interpolation of interspecies scaling would be beneficial for antimalarial drugs. Some of the techniques require raw concentration-time data (17, 18, 43), which were not available in most reports, and we therefore confined our analysis to maximum life span potential (MLP). This correction method has been incorporated in the rule of exponents, whereby simple allometry is used for exponents in the range from 0.50 to 0.77 and scaling CL × MLP against body weight is recommended when the exponent from simple allometry is in the range from 0.71 to 0.99 (44).

Our study showed that MLP correction led to substantially lower interpolated CL estimates, compared to simple allometry and data from clinical reports, except for one group of children treated with mefloquine (Table 4). We conclude that the application of MLP correction for antimalarial drugs is not supported by the present study. By comparison, simple allometry overestimated the CL/F of mefloquine in children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria, which could lead to excessive dose predictions, and therefore, this requires more detailed, contemporary clinical investigations. Conversely, interpolation from simple allometry provided good estimates of CL for dihydroartemisinin and artemether (Table 4). The piperaquine data appear to be conflicting; however, there were several clinical differences between the two populations and no conclusive explanation for the findings (56, 57). Two recent reports of piperaquine pharmacokinetics showed lower CL/F values, suggesting that the rule of exponents may be applicable to piperaquine, but as noted in Table 4, these data could not be included in the present study due to the use of pooled results from different partner drugs (12) and use of capillary blood analysis to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters (13).

Quinine predictions are problematic, due to the difference in CL (and Vz) between healthy subjects and patients with malaria, and the reported lower CL in children than adults (Table 3). Therefore, cautious interpretation of allometric scaling results are required for quinine, due to the complex and multifactorial effects of malaria infection on the pharmacokinetic properties of this drug.

The final component of our study was to translate the allometric scaling results to dose estimates (Table 5). The recommendations for dihydroartemisinin (as IV artesunate) and clindamycin would be modest increases that can be achieved in the clinical setting, whereas the small predicted increase in piperaquine dose would not be practical. It is notable that recent clinical studies have recommended higher doses for piperaquine (11, 13, 14) and artesunate in children (15). Indeed, the doses proposed in the latter study closely match the allometric predictions of 3 mg/kg (15-kg child) and 2.8 mg/kg (25-kg child), based on scaling for dihydroartemisinin in the present study.

The recommended mefloquine doses were 1.6- to 2-fold higher than reference doses for adults (mg/kg), which could be viewed as excessive and to the best of our knowledge have not been proposed in any clinical studies. However, recent allometric scaling of chloroquine indicated that pediatric doses 1.6-fold higher than those for adults (mg/kg) were potentially appropriate, and these doses were exceeded by clinical studies where 2-fold-higher doses were used in children (8, 9, 33). Complementary data are available for quinine, notwithstanding our cautious interpretation of the allometric scaling. Indeed, our results from simple allometry of quinine suggest that 18 to 24 mg/kg could be more appropriate than 10 mg/kg (Table 5), and a recent study supports earlier recommendations in adults that 20 mg/kg quinine should be used as a loading dose in children (10).

An important consideration from our allometric exponent data is that disproportionate dose increases appear to apply to antimalarial drugs, and the implications for rational pediatric dosing of combination regimens are therefore significant. For example, an adult dose of a dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (120/960 mg; approximately 2/16 mg/kg for a 60-kg patient) oral fixed-dose combination is reduced by linear calculations to 30/240 mg for a 15-kg child. However, based on our allometric interpolation, this would result in an appropriate scaled dose of piperaquine and a dihydroartemisinin dose that is 20% lower than optimum. Allometric scaling of fixed-dose combinations will be valid only if the same exponent applies to both drugs (or a default-to-fixed-exponent scaling is used); however, our data indicate this is unlikely to be appropriate for artemisinin-based combination therapies, due to mismatch of the allometric exponents (Table 1).

We conclude that interpolation of interspecies allometric scaling is plausible for estimation of pediatric doses of antimalarial drugs and would be valuable in designing clinical pharmacokinetic or efficacy studies. The limitations of allometric scaling are well documented; however, the ongoing use of linear scaling of adult to pediatric doses (mg/kg) is recognized as flawed (36) and should be the subject of further investigation in antimalarial chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the statistical advice of Richard Parsons, Faculty of Health Sciences, and the supervisory support of Andrew Crowe, School of Pharmacy, Curtin University. S.M.D.K.G.S. was the recipient of a Curtin University Strategic International Research Scholarship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2010. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson TN. 2008. The problems in scaling adult drug doses to children. Arch. Dis. Child. 93:207–211. 10.1136/adc.2006.114835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahmood I. 2006. Prediction of drug clearance in children from adults: a comparison of several allometric methods. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 61:545–557. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02622.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holford NH. 1996. A size standard for pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 30:329–332. 10.2165/00003088-199630050-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella M, Knibbe C, Danhof M, Della PO. 2010. What is the right dose for children? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70:597–603. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03591.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obua C, Hellgren U, Ntale M, Gustafsson LL, Ogwal-Okeng JW, Gordi T, Jerling M. 2008. Population pharmacokinetics of chloroquine and sulfadoxine and treatment response in children with malaria: suggestions for an improved dose regimen. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 65:493–501. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03050.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes KI, Little F, Smith PJ, Evans A, Watkins WM, White NJ. 2006. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine pharmacokinetics in malaria: pediatric dosing implications. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80:582–596. 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ursing J, Kofoed PE, Rodrigues A, Blessborn D, Thoft-Nielsen R, Bjorkman A, Rombo L. 2011. Similar efficacy and tolerability of double-dose chloroquine and artemether-lumefantrine for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum infection in Guinea-Bissau: a randomized trial. J. Infect. Dis. 203:109–116. 10.1093/infdis/jiq001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ursing J, Kofoed PE, Rodrigues A, Bergqvist Y, Rombo L. 2009. Chloroquine is grossly overdosed and overused but well tolerated in Guinea-Bissau. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:180–185. 10.1128/AAC.01111-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendriksen IC, Maiga D, Lemnge MM, Mtove G, Gesase S, Reyburn H, Lindegardh N, Day NP, von Seidlein L, Dondorp AM, Tarning J, White NJ. 2013. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of intramuscular quinine in Tanzanian children with severe falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:775–783. 10.1128/AAC.01349-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price RN, Hasugian AR, Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Purba HL, Kenangalem E, Lindegardh N, Penttinen P, Laihad F, Ebsworth EP, Anstey NM, Tjitra E. 2007. Clinical and pharmacological determinants of the therapeutic response to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for drug-resistant malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4090–4097. 10.1128/AAC.00486-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salman S, Page-Sharp M, Batty KT, Kose K, Griffin S, Siba PM, Ilett KF, Mueller I, Davis TM. 2012. Pharmacokinetic comparison of two piperaquine-containing artemisinin combination therapies in Papua New Guinean children with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3288–3297. 10.1128/AAC.06232-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarning J, Zongo I, Some FA, Rouamba N, Parikh S, Rosenthal PJ, Hanpithakpong W, Jongrak N, Day NP, White NJ, Nosten F, Ouedraogo JB, Lindegardh N. 2012. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperaquine in children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 91:497–505. 10.1038/clpt.2011.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creek DJ, Bigira V, McCormack S, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Tappero JW, Sandison TG, Lindegardh N, Nosten F, Aweeka FT, Parikh S. 2013. Pharmacokinetic predictors for recurrent malaria after dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Ugandan infants. J. Infect. Dis. 207:1646–1654. 10.1093/infdis/jit078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendriksen IC, Mtove G, Kent A, Gesase S, Reyburn H, Lemnge MM, Lindegardh N, Day NP, von Seidlein L, White NJ, Dondorp AM, Tarning J. 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of intramuscular artesunate in African children with severe malaria: implications for a practical dosing regimen. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 93:443–450. 10.1038/clpt.2013.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris CA, Tan B, Duparc S, Borghini-Fuhrer I, Jung D, Shin CS, Fleckenstein L. 2013. Effects of body size and gender on the population pharmacokinetics of artesunate and its active metabolite dihydroartemisinin in pediatric malaria patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:5889–5900. 10.1128/AAC.00635-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boxenbaum H. 1982. Interspecies scaling, allometry, physiological time, and the ground plan of pharmacokinetics. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 10:201–227. 10.1007/BF01062336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mordenti J. 1986. Man versus beast: pharmacokinetic scaling in mammals. J. Pharm. Sci. 75:1028–1040. 10.1002/jps.2600751104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ings RM. 1990. Interspecies scaling and comparisons in drug development and toxicokinetics. Xenobiotica 20:1201–1231. 10.3109/00498259009046839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White CR, Seymour RS. 2005. Allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism. J. Exp. Biol. 208:1611–1619. 10.1242/jeb.01501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West GB. 2012. The importance of quantitative systemic thinking in medicine. Lancet 379:1551–1559. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60281-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowland M, Tozer TN. 2011. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamcs: concepts and applications. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riviere JE, Martin-Jimenez T, Sundlof SF, Craigmill AL. 1997. Interspecies allometric analysis of the comparative pharmacokinetics of 44 drugs across veterinary and laboratory animal species. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 20:453–463. 10.1046/j.1365-2885.1997.00095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu TM, Hayton WL. 2001. Allometric scaling of xenobiotic clearance: uncertainty versus universality. AAPS PharmSci 3:E29. 10.1208/ps030429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox SK. 2007. Allometric scaling of marbofloxacin, moxifloxacin, danofloxacin and difloxacin pharmacokinetics: a retrospective analysis. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 30:381–386. 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2007.00886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmood I. 2007. Application of allometric principles for the prediction of pharmacokinetics in human and veterinary drug development. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59:1177–1192. 10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmood I. 2010. Interspecies scaling for the prediction of drug clearance in children: application of maximum lifespan potential and an empirical correction factor. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 49:479–492. 10.2165/11531830-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmood I, Martinez M, Hunter RP. 2006. Interspecies allometric scaling. Part I: prediction of clearance in large animals. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 29:415–423. 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2006.00786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knibbe CA, Zuideveld KP, Aarts LP, Kuks PF, Danhof M. 2005. Allometric relationships between the pharmacokinetics of propofol in rats, children and adults. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59:705–711. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02239.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peeters MY, Allegaert K, Blusse van Oud-Alblas HJ, Cella M, Tibboel D, Danhof M, Knibbe CA. 2010. Prediction of propofol clearance in children from an allometric model developed in rats, children and adults versus a 0.75 fixed-exponent allometric model. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 49:269–275. 10.2165/11319350-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brocks DR, Toni JW. 1999. Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in the rat: stereoselectivity and interspecies comparisons. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 20:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis CB, Bambal R, Moorthy GS, Hugger E, Xiang H, Park BK, Shone AE, O'Neill PM, Ward SA. 2009. Comparative preclinical drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic evaluation of novel 4-aminoquinoline anti-malarials. J. Pharm. Sci. 98:362–377. 10.1002/jps.21469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore BR, Page-Sharp M, Stoney JR, Ilett KF, Jago JD, Batty KT. 2011. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and allometric scaling of chloroquine in a murine malaria model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3899–3907. 10.1128/AAC.00067-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tod M, Jullien V, Pons G. 2008. Facilitation of drug evaluation in children by population methods and modelling. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 47:231–243. 10.2165/00003088-200847040-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson BJ, Holford NH. 2008. Mechanism-based concepts of size and maturity in pharmacokinetics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48:303–332. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holford N, Heo YA, Anderson B. 2013. A pharmacokinetic standard for babies and adults. J. Pharm. Sci. 102:2941–2952. 10.1002/jps.23574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahmood I. 2007. Prediction of drug clearance in children: impact of allometric exponents, body weight, and age. Ther. Drug Monit. 29:271–278. 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318042d3c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood I. 2010. Theoretical versus empirical allometry: facts behind theories and application to pharmacokinetics. J. Pharm. Sci. 99:2927–2933. 10.1002/jps.22073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang H, Mayersohn M. 2011. Controversies in allometric scaling for predicting human drug clearance: an historical problem and reflections on what works and what does not. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 11:340–350. 10.2174/156802611794480945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLeay SC, Morrish GA, Kirkpatrick CM, Green B. 2012. The relationship between drug clearance and body size: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature published from 2000 to 2007. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 51:319–330. 10.2165/11598930-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riond JL, Riviere JE. 1990. Allometric analysis of doxycycline pharmacokinetic parameters. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 13:404–407. 10.1111/j.1365-2885.1990.tb00795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies B, Morris T. 1993. Physiological parameters in laboratory animals and humans. Pharm. Res. 10:1093–1095. 10.1023/A:1018943613122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritschel WA, Vachharajani NN, Johnson RD, Hussain AS. 1992. The allometric approach for interspecies scaling of pharmacokinetic parameters. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 103:249–253. 10.1016/0742-8413(92)90003-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahmood I, Balian JD. 1996. Interspecies scaling: predicting clearance of drugs in humans. Three different approaches. Xenobiotica 26:887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haddad S, Restieri C, Krishnan K. 2001. Characterization of age-related changes in body weight and organ weights from birth to adolescence in humans. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 64:453–464. 10.1080/152873901753215911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West GB, Brown JH, Enquist BJ. 1997. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science 276:122–126. 10.1126/science.276.5309.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang H, Hussain A, Leal M, Fluhler E, Mayersohn M. 2011. Controversy in the allometric application of fixed- versus varying-exponent models: a statistical and mathematical perspective. J. Pharm. Sci. 100:402–410. 10.1002/jps.22316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonate PL, Howard D. 2000. Prospective allometric scaling: does the emperor have clothes? J. Clin. Pharmacol. 40:335–340. 10.1177/00912700022009017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin JH. 1995. Species similarities and differences in pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 23:1008–1021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin JH. 1998. Applications and limitations of interspecies scaling and in vitro extrapolation in pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 26:1202–1212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dinev TG. 2008. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of five aminoglycoside and aminocyclitol antibiotics using allometric analysis in mammal and bird species. Res. Vet. Sci. 84:107–118. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis TM. 2005. Mefloquine, p 1091–1104 In Yu VL, Edwards G, McKinnon PS, Peloquin C, Morse GD. (ed), Antimicrobial therapy and vaccines, vol. II Antimicrobial agents. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis TM, Hung TY, Sim IK, Karunajeewa HA, Ilett KF. 2005. Piperaquine: a resurgent antimalarial drug. Drugs 65:75–87. 10.2165/00003495-200565010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krishna S, White NJ. 1996. Pharmacokinetics of quinine, chloroquine and amodiaquine: clinical implications. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 30:263–299. 10.2165/00003088-199630040-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Binh TQ, Ilett KF, Batty KT, Davis TM, Hung NC, Powell SM, Thu LT, Thien HV, Phuong HL, Phuong VDB. 2001. Oral bioavailability of dihydroartemisinin in Vietnamese volunteers and in patients with falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 51:541–546. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01395.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hung TY, Davis TM, Ilett KF, Karunajeewa HA, Hewitt S, Denis MB, Lim C, Socheat D. 2004. Population pharmacokinetics of piperaquine in adults and children with uncomplicated falciparum or vivax malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57:253–262. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02004.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karunajeewa HA, Ilett KF, Mueller I, Siba P, Law I, Page-Sharp M, Lin E, Lammey J, Batty KT, Davis TM. 2008. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of piperaquine and chloroquine in Melanesian children with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:237–243. 10.1128/AAC.00555-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bennett K, Si Y, Steinbach T, Zhang J, Li Q. 2008. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of intramuscular artesunate in healthy beagle dogs. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79:36–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li QG, Peggins JO, Fleckenstein LL, Masonic K, Heiffer MH, Brewer TG. 1998. The pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of dihydroartemisinin, arteether, artemether, artesunic acid and artelinic acid in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 50:173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Q, Cantilena LR, Leary KJ, Saviolakis GA, Miller RS, Melendez V, Weina PJ. 2009. Pharmacokinetic profiles of artesunate after single intravenous doses at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/kg in healthy volunteers: a phase I study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 81:615–621. 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinou V, Taudon N, Mosnier J, Aglioni C, Bressolle FM, Parzy D. 2008. Pharmacokinetics of artesunate in the domestic pig. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:566–574. 10.1093/jac/dkn231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller RS, Li Q, Cantilena LR, Leary KJ, Saviolakis GA, Melendez V, Smith B, Weina PJ. 2012. Pharmacokinetic profiles of artesunate following multiple intravenous doses of 2, 4, and 8 mg/kg in healthy volunteers: phase 1b study. Malar. J. 11:255. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie LH, Li Q, Zhang J, Weina PJ. 2009. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and mass balance of radiolabeled dihydroartemisinin in male rats. Malar. J. 8:112. 10.1186/1475-2875-8-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao KC, Chen ZX, Lin BL, Guo XB, Li GQ, Song ZY. 1988. Studies on the phase 1 clinical pharmacokinetics of artesunate and artemether. Chin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 4:76–81 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karbwang J, Na-Bangchang K, Congpuong K, Molunto P, Thanavibul A. 1997. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of oral and intramuscular artemether. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52:307–310. 10.1007/s002280050295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao KC, Chen QM, Song ZY. 1986. Studies on the pharmacokinetics of qinghaosu and two of its active derivatives in dogs. Acta Pharm. Sin. 21:736–739 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeng YL, Zhang YD, Xu GY, Wang CG, Jiang JR. 1984. The pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of o-methyldihydroartemisinine in the rabbit. Acta Pharm. Sin. 19:81–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ashton M, Gordi T, Trinh NH, Nguyen VH, Nguyen DS, Nguyen TN, Dinh XH, Johansson M, Le DC. 1998. Artemisinin pharmacokinetics in healthy adults after 250, 500 and 1000 mg single oral doses. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 19:245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ashton M, Hai TN, Sy ND, Huong DX, Van Huong N, Nieu NT, Cong LD. 1998. Artemisinin pharmacokinetics is time-dependent during repeated oral administration in healthy male adults. Drug Metab. Dispos. 26:25–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ashton M, Johansson L, Thornqvist AS, Svensson US. 1999. Quantitative in vivo and in vitro sex differences in artemisinin metabolism in rat. Xenobiotica 29:195–204. 10.1080/004982599238740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benakis A, Paris M, Loutan L, Plessas CT, Plessas ST. 1997. Pharmacokinetics of artemisinin and artesunate after oral administration in healthy volunteers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duc DD, de Vries PJ, Nguyen XK, Le Nguyen B, Kager PA, van Boxtel CJ. 1994. The pharmacokinetics of a single dose of artemisinin in healthy Vietnamese subjects. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 51:785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hien TT, Hanpithakpong W, Truong NT, Dung NT, Toi PV, Farrar J, Lindegardh N, Tarning J, Ashton M. 2011. Orally formulated artemisinin in healthy fasting Vietnamese male subjects: a randomized, four-sequence, open-label, pharmacokinetic crossover study. Clin. Ther. 33:644–654. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Isacchi B, Arrigucci S, la Marca G, Bergonzi MC, Vannucchi MG, Novelli A, Bilia AR. 2011. Conventional and long-circulating liposomes of artemisinin: preparation, characterization, and pharmacokinetic profile in mice. J. Liposome Res. 21:237–244. 10.3109/08982104.2010.539185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rath K, Taxis K, Walz G, Gleiter CH, Li SM, Heide L. 2004. Pharmacokinetic study of artemisinin after oral intake of a traditional preparation of Artemisia annua L. (annual wormwood). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70:128–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li L, Pabbisetty D, Carvalho P, Avery MA, Williamson JS, Avery BA. 2008. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric method for the determination of artemisinin in rat serum and its application in pharmacokinetics. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 867:131–137. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.01.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dien TK, de Vries PJ, Khanh NX, Koopmans R, Binh LN, Duc DD, Kager PA, van Boxtel CJ. 1997. Effect of food intake on pharmacokinetics of oral artemisinin in healthy Vietnamese subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1069–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Titulaer HA, Zuidema J, Kager PA, Wetsteyn JC, Lugt CB, Merkus FW. 1990. The pharmacokinetics of artemisinin after oral, intramuscular and rectal administration to volunteers. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 42:810–813. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb07030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang S, Hai TN, Ilett KF, Huong DX, Davis TM, Ashton M. 2001. Multiple dose study of interactions between artesunate and artemisinin in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52:377–385. 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01461.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Batzias GC, Delis GA, Athanasiou LV. 2005. Clindamycin bioavailability and pharmacokinetics following oral administration of clindamycin hydrochloride capsules in dogs. Vet. J. 170:339–345. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Budsberg SC, Kemp DT, Wolski N. 1992. Pharmacokinetics of clindamycin phosphate in dogs after single intravenous and intramuscular administrations. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53:2333–2336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flaherty JF, Rodondi LC, Guglielmo BJ, Fleishaker JC, Townsend RJ, Gambertoglio JG. 1988. Comparative pharmacokinetics and serum inhibitory activity of clindamycin in different dosing regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1825–1829. 10.1128/AAC.32.12.1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gatti G, Flaherty J, Bubp J, White J, Borin M, Gambertoglio J. 1993. Comparative study of bioavailabilities and pharmacokinetics of clindamycin in healthy volunteers and patients with AIDS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1137–1143. 10.1128/AAC.37.5.1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lavy E, Ziv G, Shem-Tov M, Glickman A, Dey A. 1999. Pharmacokinetics of clindamycin HCl administered intravenously, intramuscularly and subcutaneously to dogs. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 22:261–265. 10.1046/j.1365-2885.1999.00221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Plaisance KI, Drusano GL, Forrest A, Townsend RJ, Standiford HC. 1989. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of two dosage regimens of clindamycin phosphate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:618–620. 10.1128/AAC.33.5.618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang SH, Lee MG. 2007. Dose-independent pharmacokinetics of clindamycin after intravenous and oral administration to rats: contribution of gastric first-pass effect to low bioavailability. Int. J. Pharm. 332:17–23. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Townsend RJ, Baker RP. 1987. Pharmacokinetic comparison of three clindamycin phosphate dosing schedules. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 21:279–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ahmed T, Sharma P, Gautam A, Varshney B, Kothari M, Ganguly S, Moehrle JJ, Paliwal J, Saha N, Batra V. 2008. Safety, tolerability, and single and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of piperaquine phosphate in healthy subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 48:166–175. 10.1177/0091270007310384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Batty KT, Moore BR, Stirling V, Ilett KF, Page-Sharp M, Shilkin KB, Mueller I, Karunajeewa HA, Davis TM. 2008. Toxicology and pharmacokinetics of piperaquine in mice. Toxicology 249:55–61. 10.1016/j.tox.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nguyen TC, Nguyen NQ, Nguyen XT, Bui D, Travers T, Edstein MD. 2008. Pharmacokinetics of the antimalarial drug piperaquine in healthy Vietnamese subjects. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79:620–623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sim IK, Davis TM, Ilett KF. 2005. Effects of a high-fat meal on the relative oral bioavailability of piperaquine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2407–2411. 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2407-2411.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tarning J, Lindegardh N, Sandberg S, Day NP, White NJ, Ashton M. 2008. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of the antimalarial piperaquine after intravenous and oral single doses to the rat. J. Pharm. Sci. 97:3400–3410. 10.1002/jps.21226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baudry S, Pham YT, Baune B, Vidrequin S, Crevoisier C, Gimenez F, Farinotti R. 1997. Stereoselective passage of mefloquine through the blood-brain barrier in the rat. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 49:1086–1090. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Boudreau EF, Fleckenstein L, Pang LW, Childs GE, Schroeder AC, Ratnaratorn B, Phintuyothin P. 1990. Mefloquine kinetics in cured and recrudescent patients with acute falciparum malaria and in healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 48:399–409. 10.1038/clpt.1990.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Charles BG, Blomgren A, Nasveld PE, Kitchener SJ, Jensen A, Gregory RM, Robertson B, Harris IE, Reid MP, Edstein MD. 2007. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in military personnel for prophylaxis against malaria infection during field deployment. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63:271–278. 10.1007/s00228-006-0247-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crevoisier C, Handschin J, Barre J, Roumenov D, Kleinbloesem C. 1997. Food increases the bioavailability of mefloquine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 53:135–139. 10.1007/s002280050351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Franssen G, Rouveix B, Lebras J, Bauchet J, Verdier F, Michon C, Bricaire F. 1989. Divided-dose kinetics of mefloquine in man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 28:179–184. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb05413.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gimenez F, Pennie RA, Koren G, Crevoisier C, Wainer IW, Farinotti R. 1994. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in healthy Caucasians after multiple doses. J. Pharm. Sci. 83:824–827. 10.1002/jps.2600830613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Juma FD, Ogeto JO. 1989. Mefloquine disposition in normals and in patients with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 14:15–17. 10.1007/BF03190836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Karbwang J, Back DJ, Bunnag D, Breckenridge AM. 1988. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in healthy Thai volunteers and in Thai patients with falciparum malaria. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 35:677–680. 10.1007/BF00637607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Karbwang J, Bunnag D, Breckenridge AM, Back DJ. 1987. The pharmacokinetics of mefloquine when given alone or in combination with sulphadoxine and pyrimethamine in Thai male and female subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 32:173–177. 10.1007/BF00542191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Karbwang J, Looareesuwan S, Back DJ, Migasana S, Bunnag D, Breckenridge AM. 1988. Effect of oral contraceptive steroids on the clinical course of malaria infection and on the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in Thai women. Bull. World Health Organ. 66:763–767 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Karbwang J, Looareesuwan S, Phillips RE, Wattanagoon Y, Molyneux ME, Nagachinta B, Back DJ, Warrell DA. 1987. Plasma and whole blood mefloquine concentrations during treatment of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria with the combination mefloquine-sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 23:477–481. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03079.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khaliq Y, Gallicano K, Tisdale C, Carignan G, Cooper C, McCarthy A. 2001. Pharmacokinetic interaction between mefloquine and ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 51:591–600. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01393.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kolawole JA, Mustapha A, Abudu-Aguye I, Ochekpe N. 2000. Mefloquine pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects and in peptic ulcer patients after cimetidine administration. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 25:165–170. 10.1007/BF03192309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Warrell DA, Forgo I, Dubach UG, Ranalder UB, Schwartz DE. 1987. Studies of mefloquine bioavailability and kinetics using a stable isotope technique: a comparison of Thai patients with falciparum malaria and healthy Caucasian volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 24:37–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03133.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pennie RA, Koren G, Crevoisier C. 1993. Steady state pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in long-term travellers. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87:459–462. 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90036-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ridtitid W, Wongnawa M, Mahatthanatrakul W, Raungsri N, Sunbhanich M. 2005. Ketoconazole increases plasma concentrations of antimalarial mefloquine in healthy human volunteers. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 30:285–290. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ridtitid W, Wongnawa M, Mahatthanatrakul W, Chaipol P, Sunbhanich M. 2000. Effect of rifampin on plasma concentrations of mefloquine in healthy volunteers. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 52:1265–1269. 10.1211/0022357001777243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rozman RS, Molek NA, Koby R. 1978. The absorption, distribution, and excretion in mice of the antimalarial mefloquine, erythro-2,8-bis(trifluoromethyl)-alpha-(2-piperidyl)-4-quinolinemethanol hydrochloride. Drug Metab. Dispos. 6:654–658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brum L, Leal MG, Uchoa FT, Kaiser M, Guterres SS, Costa TD. 2011. Determination of quinine and doxycycline in rat plasma by LC–MS–MS: application to a pharmacokinetic study. Chromatographia 73:1081–1088. 10.1007/s10337-011-1949-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Claessen FA, van Boxtel CJ, Perenboom RM, Tange RA, Wetsteijn JC, Kager PA. 1998. Quinine pharmacokinetics: ototoxic and cardiotoxic effects in healthy Caucasian subjects and in patients with falciparum malaria. Trop. Med. Int. Health 3:482–489. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00252.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Clohisy DR, Gibson TP. 1982. Comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters of intravenous quinidine and quinine in dogs. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 4:107–110. 10.1097/00005344-198201000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Karbwang J, Thanavibul A, Molunto P, Na BK. 1993. The pharmacokinetics of quinine in patients with hepatitis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 35:444–446. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04165.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Karbwang J, Davis TM, Looareesuwan S, Molunto P, Bunnag D, White NJ. 1993. A comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of quinine and quinidine in healthy Thai males. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 35:265–271 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Paintaud G, Alvan G, Ericsson O. 1993. The reproducibility of quinine bioavailability. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 35:305–307. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb05698.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Salako LA, Sowunmi A. 1992. Disposition of quinine in plasma, red blood cells and saliva after oral and intravenous administration to healthy adult Africans. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 42:171–174. 10.1007/BF00278479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pussard E, Barennes H, Daouda H, Clavier F, Sani AM, Osse M, Granic G, Verdier F. 1999. Quinine disposition in globally malnourished children with cerebral malaria. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 65:500–510. 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70069-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wanwimolruk S, Wong SM, Coville PF, Viriyayudhakorn S, Thitiarchakul S. 1993. Cigarette smoking enhances the elimination of quinine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 36:610–614. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb00424.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang H, Wong CW, Coville PF, Wanwimolruk S. 2000. Effect of the grapefruit flavonoid naringin on pharmacokinetics of quinine in rats. Drug Metab. Drug Interact. 17:351–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Watari N, Wakamatsu A, Kaneniwa N. 1989. Comparison of disposition parameters of quinidine and quinine in the rat. J. Pharmacobiodyn. 12:608–615. 10.1248/bpb1978.12.608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.White NJ, Chanthavanich P, Krishna S, Bunch C, Silamut K. 1983. Quinine disposition kinetics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 16:399–403. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02184.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhang H, Ramsay N, Coville PF, Wanwimolruk S. 1999. Effect of erythromycin, rifampicin and isoniazid on the pharmacokinetics of quinine in rats. Pharm. Pharmacol. Commun. 5:467–472. 10.1211/146080899128735180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hasan MM, Hassan MA, Rawashdeh NM. 1990. Effect of oral activated charcoal on the pharmacokinetics of quinidine and quinine administered intravenously to rabbits. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 67:73–76. 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1990.tb00785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Batty KT, Thu LT, Davis TM, Ilett KF, Mai TX, Hung NC, Tien NP, Powell SM, Thien HV, Binh TQ, Kim NV. 1998. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of intravenous vs oral artesunate in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45:123–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Batty KT, Thu LT, Ilett KF, Tien NP, Powell SM, Hung NC, Mai TX, Chon VV, Thien HV, Binh TQ, Kim NV, Davis TM. 1998. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of artesunate for vivax malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 59:823–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Byakika-Kibwika P, Lamorde M, Mayito J, Nabukeera L, Mayanja-Kizza H, Katabira E, Hanpithakpong W, Obua C, Pakker N, Lindegardh N, Tarning J, de Vries PJ, Merry C. 2012. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous artesunate during severe malaria treatment in Ugandan adults. Malar. J. 11:132. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Davis TM, Phuong HL, Ilett KF, Hung NC, Batty KT, Phuong VDB, Powell SM, Thien HV, Binh TQ. 2001. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous artesunate in severe falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:181–186. 10.1128/AAC.45.1.181-186.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ilett KF, Batty KT, Powell SM, Binh TQ, Thu LT, Phuong HL, Hung NC, Davis TM. 2002. The pharmacokinetic properties of intramuscular artesunate and rectal dihydroartemisinin in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 53:23–30. 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01519.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Newton P, Suputtamongkol Y, Teja-Isavadharm P, Pukrittayakamee S, Navaratnam V, Bates I, White N. 2000. Antimalarial bioavailability and disposition of artesunate in acute falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:972–977. 10.1128/AAC.44.4.972-977.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Newton PN, Barnes KI, Smith PJ, Evans AC, Chierakul W, Ruangveerayuth R, White NJ. 2006. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous artesunate in adults with severe falciparum malaria. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 62:1003–1009. 10.1007/s00228-006-0203-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Silamut K, Newton PN, Teja-Isavadharm P, Suputtamongkol Y, Siriyanonda D, Rasameesoraj M, Pukrittayakamee S, White NJ. 2003. Artemether bioavailability after oral or intramuscular administration in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3795–3798. 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3795-3798.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Karbwang J, Na-Bangchang K, Tin T, Sukontason K, Rimchala W, Harinasuta 1998. Pharmacokinetics of intramuscular artemether in patients with severe falciparum malaria with or without acute renal failure. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45:597–600. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00723.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hai TN, Hietala SF, Van HN, Ashton M. 2008. The influence of food on the pharmacokinetics of piperaquine in healthy Vietnamese volunteers. Acta Trop. 107:145–149. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Roshammar D, Hai TN, Hietala SF, Huong NV, Ashton M. 2006. Pharmacokinetics of piperaquine after repeated oral administration of the antimalarial combination CV8 in 12 healthy male subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 62:335–341. 10.1007/s00228-005-0084-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Staehli Hodel EM, Guidi M, Zanolari B, Mercier T, Duong S, Kabanywanyi AM, Ariey F, Buclin T, Beck HP, Decosterd LA, Olliaro P, Genton B, Csajka C. 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine, piperaquine and artemether-lumefantrine in Cambodian and Tanzanian malaria patients. Malar. J. 12:235. 10.1186/1475-2875-12-235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tarning J, Rijken MJ, McGready R, Phyo AP, Hanpithakpong W, Day NP, White NJ, Nosten F, Lindegardh N. 2012. Population pharmacokinetics of dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine in pregnant and nonpregnant women with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1997–2007. 10.1128/AAC.05756-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Lawal O, Sijuade A, Sowunmi A, Oduola A. 2012. A high performance liquid chromatographic assay of mefloquine in saliva after a single oral dose in healthy adult Africans. Malar. J. 11:59. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Karbwang J, Na BK, Back DJ, Bunnag D. 1991. Effect of ampicillin on mefloquine pharmacokinetics in Thai males. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 40:631–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Abdelrahim II, Adam I, Elghazali G, Gustafsson LL, Elbashir MI, Mirghani RA. 2007. Pharmacokinetics of quinine and its metabolites in pregnant Sudanese women with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 32:15–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00788.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Couet W, Laroche R, Floch JJ, Istin B, Fourtillan JB, Sauniere JF. 1991. Pharmacokinetics of quinine and doxycycline in patients with acute falciparum malaria: a study in Africa. Ther. Drug Monit. 13:496–501. 10.1097/00007691-199111000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Davis TM, Supanaranond W, Pukrittayakamee S, Karbwang J, Molunto P, Mekthon S, White NJ. 1990. A safe and effective consecutive-infusion regimen for rapid quinine loading in severe falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 161:1305–1308. 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Davis TM, White NJ, Looareesuwan S, Silamut K, Warrell DA. 1988. Quinine pharmacokinetics in cerebral malaria: predicted plasma concentrations after rapid intravenous loading using a two-compartment model. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82:542–547. 10.1016/0035-9203(88)90498-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pukrittayakamee S, Looareesuwan S, Keeratithakul D, Davis TM, Teja-Isavadharm P, Nagachinta B, Weber A, Smith AL, Kyle D, White NJ. 1997. A study of the factors affecting the metabolic clearance of quinine in malaria. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52:487–493. 10.1007/s002280050323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.White NJ, Looareesuwan S, Warrell DA, Warrell MJ, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T. 1982. Qunine pharmacokinetics and toxicity in cerebral and uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am. J. Med. 73:564–572. 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sabchareon A, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Attanath P. 1982. Serum quinine concentrations following the initial dose in children with falciparum malaria. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 13:556–562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Shann F, Stace J, Edstein M. 1985. Pharmacokinetics of quinine in children. J. Pediatr. 106:506–510. 10.1016/S0022-3476(85)80692-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liu C, Zhang R, Hong X, Huang T, Mi S, Wang N. 2007. Pharmacokinetics of piperaquine after single and multiple oral administrations in healthy volunteers. Yakugaku Zasshi 127:1709–1714. 10.1248/yakushi.127.1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nealon C, Dzeing A, Muller-Romer U, Planche T, Sinou V, Kombila M, Kremsner PG, Parzy D, Krishna S. 2002. Intramuscular bioavailability and clinical efficacy of artesunate in gabonese children with severe malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3933–3939. 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3933-3939.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Mithwani S, Aarons L, Kokwaro GO, Majid O, Muchohi S, Edwards G, Mohamed S, Marsh K, Watkins W. 2004. Population pharmacokinetics of artemether and dihydroartemisinin following single intramuscular dosing of artemether in African children with severe falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57:146–152. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01986.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bourahla A, Martin C, Gimenez F, Singhasivanon V, Attanath P, Sabchearon A, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Farinotti R. 1996. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in young children. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 50:241–244. 10.1007/s002280050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Singhasivanon V, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabcharoen A, Attanath P, Webster HK, Wernsdorfer WH, Sheth UK, Djaja L., I 1992. Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in children aged 6 to 24 months. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 17:275–279. 10.1007/BF03190160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Singhasivanon V, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabchareon A, Attanath P, Webster HK, Edstein MD, Lika ID. 1994. Pharmacokinetic study of mefloquine in Thai children aged 5–12 years suffering from uncomplicated falciparum malaria treated with MSP or MSP plus primaquine. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 19:27–32. 10.1007/BF03188819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]