Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS fall within a spectrum of pulmonary disease that is characterized by hypoxemia, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, and dysregulated and excessive inflammation. While mortality rates have improved with the advent of specialized ICUs and lung protective mechanical ventilation strategies, few other therapies have proven effective in the management of ARDS, which remains a significant clinical problem. Further development of biomarkers of disease severity, response to therapy, and prognosis is urgently needed. Several novel pathways have been identified and studied with respect to the pathogenesis of ALI and ARDS that show promise in bridging some of these gaps. This review will focus on the roles of matrix metalloproteinases and protein tyrosine kinases in the pathobiology of ALI in humans, and in animal models and in vitro studies. These molecules can act independently, as well as coordinately, in a feed-forward manner via activation of tyrosine kinase-regulated pathways that are pivotal in the development of ARDS. Specific signaling events involving proteolytic processing by matrix metalloproteinases that contribute to ALI, including cytokine and chemokine activation and release, neutrophil recruitment, transmigration and activation, and disruption of the intact alveolar-capillary barrier, will be explored in the context of these novel molecular pathways.

ARDS is characterized by progressive arterial hypoxemia, dyspnea, increased work of breathing, and respiratory failure.1,2 The hallmarks of the clinical syndrome include bilateral radiographic infiltrates, hypoxemia, and decreased pulmonary compliance.1,2 Histopathologically, ARDS is characterized by interstitial and alveolar edema, accumulation of inflammatory and RBCs in the alveolar spaces, denudation of the alveolar epithelium, and hyaline membrane formation. Proliferation of alveolar type 2 epithelial cells and fibroblasts and deposition of collagen with subsequent fibrosis (fibroproliferative ARDS) may occur in the subacute and chronic phases and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3

The definition of ARDS has been revised to reflect the degree of hypoxemia, dividing the spectrum of disease into mild, moderate, and severe, and allowing greater predictive power in terms of morbidity.4 While the term acute lung injury (ALI) is no longer used clinically, animal models of ALI have been developed with many features in common with human ARDS. Thus, for the purposes of this review, ALI and ARDS will be used interchangeably to reflect their common pathophysiology.

ARDS can be associated with both direct (pneumonia, aspiration of gastric contents) and indirect (sepsis, trauma, multiple transfusions) injury to the lung. Sepsis is the most commonly associated clinical disorder, accounting for approximately 40% of ARDS cases.5 ARDS results in a large burden of critical illness, with > 200,000 cases annually in the United States and a mortality rate ranging from approximately 23% to 45%, depending on various factors, such as comorbidities.4,6-8 Although most of those who survive the acute illness recover near-normal pulmonary function within 1 year,2 many survivors suffer from long-term sequelae, including exercise limitation, physical and psychologic impairment, decreased quality of life, and increased costs and use of health-care resources.9 However, while biomarkers that predict disease severity and prognosis are emerging,10 additional markers are needed to identify patients with ARDS who may be at the highest risk for adverse outcomes and who might derive the greatest benefit from targeted therapeutic intervention.

The pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS is complex and involves an excessive and inappropriate inflammatory response resulting in damage to the alveolar-capillary barrier, accumulation of pulmonary edema fluid, and impaired removal of edema fluid and resolution of inflammation.1,2 In the acute phase of lung injury, increased permeability of the alveolar-capillary barrier results in an influx of protein-rich edema fluid that contains large numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and denuded epithelial cells, as well as proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines, proteinases, oxidants, and procoagulants1,5 (Fig 1). Not only does epithelial injury contribute to the accumulation of edema fluid and generation of proinflammatory mediators, it also results in impaired surfactant production and function,11 and abnormal fluid transport, resulting in impaired clearance of edema fluid.5 One of the best characterized mechanisms of lung injury is via damage to the endothelium and epithelium by neutrophil-derived mediators, including proteinases and reactive oxygen species.12,13 This damage includes endothelial and epithelial cell death and leads to increased permeability of the alveolar-capillary barrier.12-14 Other mechanisms may also contribute to the development of ALI, including cytokine release,15 dysregulation of the coagulation system,16 and excess mechanical stretch, as in the case of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).17,18

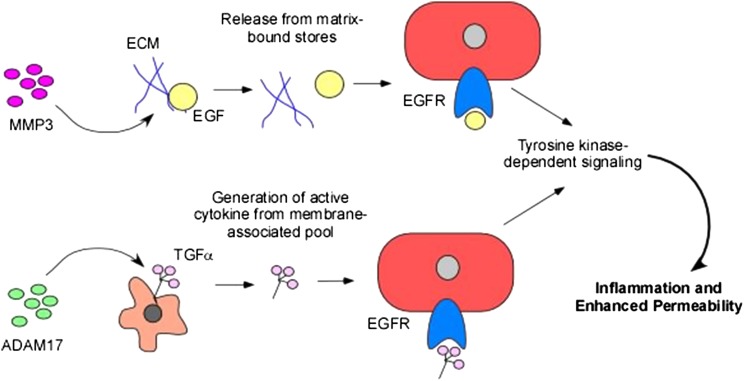

Figure 1 –

Coordinate roles of MMPs and tyrosine kinases in control of lung inflammation. MMPs can release cytokines and growth factors from pools bound to the ECM, leading to increased local and systemic levels of these mediators. EGF is used as an example of this mechanism. Additionally, MMPs and other proteinases can cleave membrane-bound molecules generating active mediators such as cytokines and growth factors that trigger tyrosine kinase-dependent signaling pathways. TGF-α is used as an example of this mechanism. ECM = extracellular matrix; EGF = endothelial growth factor; EGFR = endothelial growth factor receptor; MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; TGF = transforming growth factor.

This review will focus on the roles of two classes of molecules that participate in the development of ALI: the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), which are emerging as key participants in the pathogenesis of ARDS and represent potential targets for therapeutic intervention (Fig 1). While MMPs and PTKs have various independent functions, they have been shown to act coordinately and on common pathways, culminating in lung injury. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, mechanisms involving proteolytic processing of cytokines, growth factors, and receptors that lead to the recruitment and activation of immune cells, enhanced cytokine responses, and disruption of epithelial and endothelial barriers, represent potential avenues by which MMPs and PTKs contribute to lung injury in the context of ARDS.

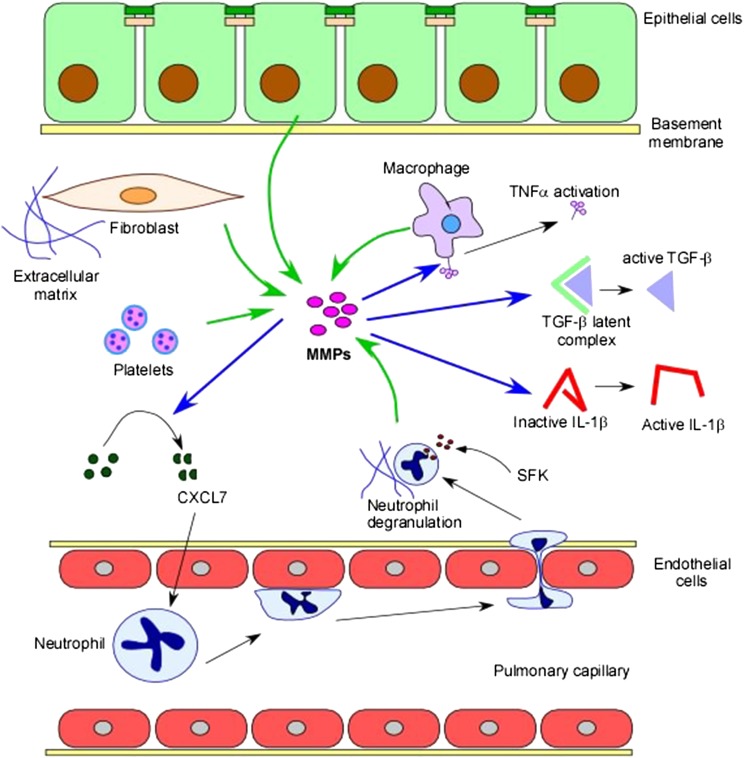

Figure 2 –

Regulation of lung inflammation. MMPs and protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) can influence inflammatory responses in several ways. MMPs can be secreted from various cell types, including fibroblasts, macrophages, platelets, and epithelial cells (green arrows). MMPs can act on multiple targets (blue arrows). MMPs can cleave chemokines, such as CXCL7, resulting in enhanced chemotactic responses. They can also proteolytically process cytokines, leading to their activation, including TNF-α, TGF-β, and IL-1β. MMPs can also proteolytically cleave and activate receptor tyrosine kinases) and/or their ligands, triggering downstream proinflammatory signaling pathways. PTK signaling, including through SFKs, can result in proinflammatory responses such as degranulation of recruited neutrophils. SFK = Src family kinase; TNF = tumor necrosis factor. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Introduction to MMPs

The MMPs compose a family of > 20 structurally related, zinc-dependent endopeptidases that can degrade collagen and other components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). MMPs are members of the metzincin subgroup of zinc proteinases, along with the adamalysins, which contain a similar metalloproteinase domain and can act on overlapping substrates, but differ from MMPs based on unique integrin-receptor binding disintegrin domains.19 MMPs have been shown to play a critical role in physiologic tissue remodeling and wound repair.20,21 MMPs can be produced by immune cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells, and are divided into subgroups based on their substrate specificity and structural properties: (1) gelatinases (MMP-2 and -9), (2) stromelysins (MMP-3, -10, and -11), (3) collagenases (MMP-1, -8, and -13), (4) matrilysins (MMP-7 and -26), and (5) membrane-type MMPs (MMP-14, -15, -16, -17, -24, -25).22 In addition to their ability to degrade and remodel the ECM, MMPs can cleave nonmatrix molecules, resulting in alterations in cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions and activation or inactivation of cytokines, growth factors, and cell-surface receptors.23 These pleiotropic activities allow MMPs to participate in inflammation, host defense, and repair of injured tissues.24 MMPs have also been implicated in pathologic processes, including rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and fibrosis of the liver, kidneys, heart, and lungs.25-29 Recent evidence suggests that MMPs play a role in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS.

MMP Levels Correlate With Risk and Severity of ARDS in Humans

Considerable clinical data have demonstrated associations between lung injury and increased levels of a variety of MMPs, including MMP-1, -2, -3, -7, -8, -9, -12 and -13 in BAL fluid.30-34 Furthermore, BAL levels of MMP-2, -8, and -9 correlated with increased neutrophil counts, while MMP-1 and MMP-3 levels correlated with increased mortality, disease severity, and multiorgan failure. Thus, BAL or blood levels of individual or panels of MMPs may serve as markers of acute neutrophilic inflammation, while levels of other MMPs may provide further insight in terms of prognostic implications.35,36

Cytokine and Chemokine Processing by MMPs

As noted, MMPs can regulate tissue injury and repair by altering the activity of nonmatrix proteins including cytokines, chemokines, and membrane receptors (Figs 1, 2). Multiple cytokines can be cleaved by MMPs, resulting in activation, inactivation, or alterations in bioavailability, which may contribute to further inflammation in the injured lung. For example, MMP-7 is required for shedding of membrane-bound tumor necrosis factor-α (Fig 2), a step that is obligatory for its innate biologic functions.37 Similarly, transforming growth factor-β, which is increased in the BAL fluid of patients with ARDS and induces pulmonary edema in animal models of ALI,38,39 can be activated by release from its latent complex by multiple MMPs, including MMP-2, -3, -9, and 14.40-43 IL-1β may also be activated by proteolytic cleavage from an inactive precursor by MMP-2, -3, and -9.44 Conversely, some of these same enzymes (MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9) can inactivate IL-1β by more extensive proteolytic cleavage.44,45 Thus, MMPs can exert both positive and negative influences on inflammation.46,47

Neutrophil-mediated injury to the alveolar epithelium and endothelium are central to the pathogenesis of ARDS. Several studies have suggested that MMPs play a role in neutrophil recruitment and, thus, promote lung injury. For example, mice genetically deficient in MMP-3 and MMP-9 were protected from lung injury in an immune complex model of ALI.48 MMP-3-deficient mice also exhibited diminished neutrophil recruitment, a pattern that was not seen in MMP-9-deficient mice, highlighting that individual MMPs act by different mechanisms in the pathogenesis of ALI.48 Mice deficient in MMP-1 were also protected from ALI induced by immune complexes or intratracheal instillation of MIP-2, a neutrophil chemoattractant.49 Finally, MMP-3-deficient mice were protected from bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis,50 a model that includes an early acute inflammatory response associated with ALI.51

While the mechanisms by which MMPs induce neutrophil recruitment into the lung remain unclear, several possibilities can be inferred from studies investigating their roles in disease models of the lung and other organs. For example, MMP-7 released from wounded epithelial cells cleaves a complex of KC/syndecan-1, allowing the complex to cross the epithelium into the alveolar space and establish a chemotactic gradient for neutrophils.52 In IL-1β-stimulated intestinal epithelial cells, proteolytic cleavage of platelet basic protein by MMP-3 yielded the active neutrophil chemokine CXCL7.53 Similarly, MMP-8 and MMP-9 can proteolytically activate CXCL5 and CXCL8, respectively,46 while MMP-3 is capable of generating a macrophage chemotactic factor in the setting of disc degeneration.37 Other studies have shown that MMPs can influence leukocyte trafficking (Fig 3) by mechanisms such as MMP-mediated proteolysis of cryptic ECM sites possessing chemotactic properties, release of chemokines from the ECM resulting in chemokine gradients, and degradation of ECM-derived barriers allowing for passage of neutrophils into various physiologic compartments.46,47

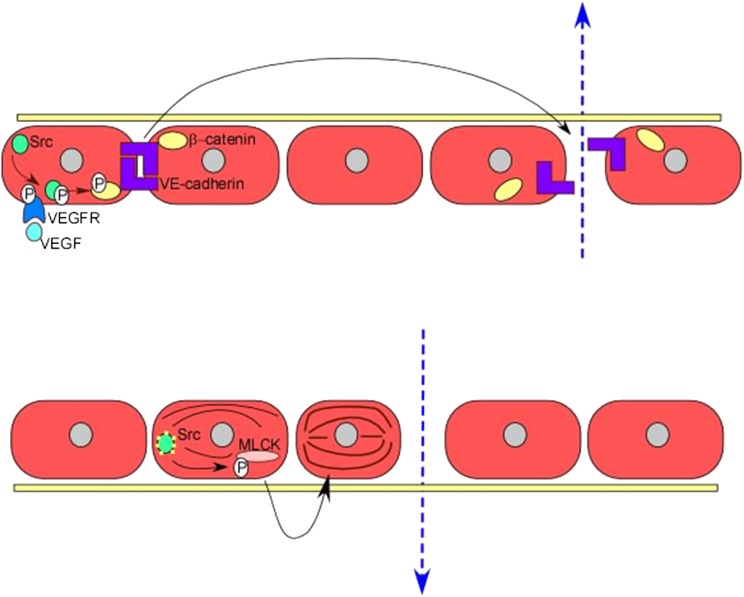

Figure 3 –

Increased vascular permeability. Protein tyrosine kinase signaling enhances vascular permeability in several ways. Signaling via receptor tyrosine kinases and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, including VEGFR and Src, results in phosphorylation of β-catenin and subsequent dissociation of VE-cadherin homodimers, which loosens cell-cell contacts. Src also phosphorylates and activates MLCK, causing alterations in the cytoskeleton and changes in endothelial cell structure and shape, leading to increased endothelial permeability. MLCK = myosin light chain kinase; VE = vascular endothelial; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Breach of the Epithelial Barrier

Inflammatory injury to the alveolar epithelium, endothelium, and basement membranes is integral to the pathogenesis of ARDS. An intact alveolar-capillary barrier can be disrupted by degradation of the basement membrane or destruction of interendothelial or interepithelial junctions or anchoring proteins.54 Both MMP-2 and MMP-9 can degrade type 4 collagen (Fig 4), the main component of basement membranes.55 Markers of basement membrane disruption are present in the BAL fluid of patients with ARDS and levels of these markers correlate positively with levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9.31 Additionally, MMP-3 can cleave E-cadherin, an important component of interepithelial junctions needed for cell-cell contact and maintenance of an intact alveolar-capillary barrier.56

Figure 4 –

Breach of epithelial barrier. MMPs can disrupt various components of the epithelial barrier, allowing for transcellular passage of edema fluid and proteins, including proteinases such as MMPs. MMPs can also cleave the basement membrane, resulting in release of type 4 collagen fragments; and disrupt tight and adherens junctions, loosening cell-cell contacts. MMP secretion can also activate various RTKs, such as EGFR and PDGFR, leading to proinflammatory downstream signaling. PDGFR = platelet-derived growth factor receptor; RTK = receptor tyrosine kinase. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury

In VILI, excessive mechanical stress induces pro-inflammatory responses resulting in adverse patient outcomes, while low tidal volume, lung-protective ventilator strategies have been shown to attenuate this phenomenon.18,57-59 MMPs released in the setting of mechanical stress may mediate some of the injurious effects of VILI by promoting acute inflammatory responses. For example, MMP-8-deficient mice subjected to injurious ventilation demonstrated enhanced gas exchange, decreased lung permeability and edema, and reduced levels of inflammation, as compared with wild-type control mice.60 Conversely, MMP-9-deficient mice exhibited more severe VILI compared with wild-type control mice, perhaps attributable to the role that MMP-9 plays in control of release and/or activation of protective cytokines.61 Such studies demonstrating potentially divergent roles of MMPs in the context of VILI underscore the complexity of these enzymes in pathogenesis of lung injury.

Lung Repair After Acute Injury

In addition to the reported effects of MMPs in the acute injury phase, there is also evidence supporting a role for these enzymes in the wound healing and repair phases of ARDS. Repair of alveolar epithelial damage involves spreading and migration of adjacent alveolar type 2 cells along a provisional matrix, with subsequent proliferation and differentiation to alveolar type 1 cells.62 MMP-7 has been implicated in this process; overexpression of MMP-7 resulted in enhanced epithelial cell migration during wound repair.35,63 In bleomycin and wounded tracheal explant models, MMP-7 deficiency resulted in decreased E-cadherin shedding, a process that loosens cell-cell contacts and is needed for cell migration during wound repair.63 In vitro, MMP-9 activity correlates with a migratory phenotype that is essential for wound healing.64

In summary, MMPs are capable of degrading the ECM, and also function to regulate cell behavior through proteolytic processing of numerous cytokines and growth factors that play a role in the development of and response to injury and inflammation. Multiple in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that MMPs are central in the pathogenesis of ALI through processing and activation of cytokines and barrier disruption, while also playing a role in the resolution of lung injury.

In addition to their direct effects, MMPs interact with other signaling pathways involved in ALI. Among these pathways are those regulated by protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs). MMPs can activate these pathways by enhancing the bioavailability of ligands through ECM processing or cleavage of non-ECM molecules.65 Alternatively, MMP expression and secretion can be increased as a downstream consequence of various signaling cascades that are controlled by the action of a variety of PTKs. Even when PTKs act independently of MMP-mediated actions, the final pathologic outcomes are often similar, resulting in inflammatory cell recruitment and barrier dysfunction, which ultimately culminate in development of lung injury. The role of PTKs in ALI and ARDS, both dependent and independent of MMPs, will be addressed in the following sections.

Introduction to PTKs

PTKs are a family of enzymes that catalyze the reversible phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on substrate proteins. Phosphorylation can occur as an autophosphorylation event or as phosphorylation of a downstream signaling protein.66 Through this process, PTKs are able to regulate diverse physiologic cellular functions, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and metabolism.67 PTKs are subdivided into two groups: receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (NRTKs). RTKs include receptors for many growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). NRTKs can transmit signals downstream of RTKs, as well as other cell surface receptors.66 The catalytic activity of both RTKs and NRTKs is tightly regulated, although overexuberant responses have been shown to play a role in pathologic states such as ALI.68 The mechanisms underlying PTK effects in ALI include neutrophil chemoattraction and activation, and modulation of endothelial permeability. The latter may occur by decreased adhesion between adjacent endothelial cells at sites of intercellular junctions, allowing for passage of edema fluid and protein into the interstitial space. Increased adhesion of inflammatory cells may also occur, facilitating leukocyte recruitment at sites of injury.69 These physiologically important responses are controlled by PTKs and will be addressed in more detail later.

Src and Src Family Kinases

The Src family kinases (SFKs) compose the largest subfamily of NRTKs with nine members, including Src, Fyn, Yes, Yrk, Blk, Fgr, Hck, Lck, and Lyn.66 SFKs play a critical role in the regulation of inflammatory responses, including ALI.68 Animal models of oxidant- and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung injury have revealed increased Src activity.70,71 In rodent models of ALI, Src inhibitors attenuated lung injury, with decreased pulmonary neutrophil sequestration, capillary permeability, and cytokine and chemokine levels.72,73 Additionally, mechanical stress (eg, VILI) results in SFK activation.74,75 Several molecular mechanisms underlie the role SFKs play in promoting lung injury, including recruitment and activation of immune cells and regulation of vascular permeability.68 SFKs and cytoskeletal proteins interact to influence neutrophil adhesion and activation.76 SFK activation correlates with neutrophil adhesion following β2-integrin-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation77 and neutrophils from Hck and Fgr double-knockout mice exhibited an impaired adhesion-dependent respiratory burst.78 Thus, SFKs are required for adhesion and spreading of neutrophils on ECM, leading to enhanced activation. SFKs are also required for adhesion-dependent neutrophil degranulation with release of a diverse array of powerful proteinases that can damage the lung.79

In addition to enhancing inflammatory cell responses, SFKs also regulate structural alterations in the endothelium affecting vascular permeability by phosphorylation of myosin light-chain via regulation of myosin light-chain kinase activity.68 Src may also phosphorylate the junctional proteins VE-cadherin and β-catenin, promoting dissociation from their cytoskeletal anchors and resulting in endothelial barrier dysfunction (Figs 2, 3), which may contribute to pulmonary edema.68 Importantly, Src inhibitors attenuated the increased lung permeability in animal models of ALI.71

VEGF Receptors

VEGFR-2 mediates most of the effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) on endothelial cells, including cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and vascular permeability. VEGFR-2 expression is increased under conditions of hypoxia, a hallmark of ARDS.80 Stimulation of endothelial cells with MMP-1 increases the expression of VEGFR-2,81 and a subset of MMPs can cleave matrix-bound VEGF to release soluble fragments.82 Interestingly, VEGF stimulation increases secretion of MMP-1, -3, -9, and -13, which may provide the basis for a feed-forward loop.83,84

Ligand binding to VEGFR-2 results in activation of focal adhesion-associated kinases, including p38 MAPK and focal adhesion kinase (a tyrosine kinase) with subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin, leading to endothelial cell migration.85 In addition, interactions with Src and Yes may mediate VEGF-induced vascular permeability.86 Clinically, patients with ARDS have been shown to have increased plasma levels of VEGF compared with normal control subjects or those at risk for ARDS.87

Human EGFRs

The EGFR family of RTKs regulates airway and alveolar epithelial barrier function during injury and repair. EGFR signaling can be protective or injurious depending on the context, degree of activation, and experimental model.88 EGFR ligand shedding is induced in the setting of injury (scratch or mechanical stress), resulting in EGFR activation,89,90 in turn promoting cell proliferation, spreading, and motility.91,92 Cell spreading in response to IL-1β-dependent activation of EGFR can enhance repair of wounded epithelium.93 Conversely, EGFR promotes lung injury in animal94 and cell culture95 models of VILI; inhibition of HER2, a member of the EGFR family, in a murine model of ALI attenuated lung injury.96 Administration of exogenous EGFR, however, did not recapitulate injury, suggesting that EGFR is necessary but not sufficient to induce lung injury.94 EGFR-related lung injury may be mediated by rearrangement of apical junctional complex proteins, resulting in disruption of cell-cell adhesions and leading to epithelial barrier dysfunction.97,98 EGF can also induce the expression of various MMPs, which, in turn, promote lung injury.99 In lung interstitial smooth muscle cells, EGFR transactivation mediated by ADAM17-dependent shedding of ligands (Fig 1) is necessary for the development of acute pulmonary inflammatory responses, such as edema formation and neutrophil recruitment.100

Eph Receptors

The Eph receptor tyrosine kinases are cell-surface molecules activated by ephrin ligands that modify cytoskeletal organization and cell-cell and cell-surface adhesion. Signaling through these receptors results in activation of multiple downstream pathways, including Src family kinases, MAPK, and chemokine signaling pathways.69,101 EphA2 receptor and its ligand, ephrin-A1, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ALI, primarily by inducing endothelial permeability.102 This may occur via activation of a RhoA-GTPase signaling pathway, resulting in destabilization of VE-cadherin-mediated endothelial cell-cell adhesion.103 In addition, Eph2A mediated upregulation of ICAM-1 may result in changes in endothelial cell cytoskeletal structure, ultimately resulting in leukocyte adhesion and increased vascular leak.104 In vivo, biphasic downregulation and upregulation of EphA2 and ephrin-A1 have been shown in LPS-injured rat lungs,105 and EphA1 receptor expression was increased in a model of hypoxia.102 Administration of ephrin-A1 in rats resulted in endothelial barrier disruption,102 while EphA2 receptor inhibition reduced lung edema and albumin extravasation.106 In addition, EphA2 knockout mice were protected from bleomycin-induced lung injury.107

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor

PDGFR is an RTK activated in response to binding of its ligand, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which has been shown to play a role in ALI, functioning as a chemotactic factor for inflammatory cells.108 Overexpression of PDGF can induce inflammatory lung injury109 and elevated concentrations of PDGF have been found in patients with ARDS.110 Inhibition of the PDGF/PDGFR pathway by tyrosine kinase inhibitors attenuated lung injury in response to LPS and bleomycin, and may limit the fibroproliferative responses to ALI.108,111

PDGF has been shown to stimulate expression of MMPs in mesenchymal stem cells, allowing for traffic through basement membrane barriers.112 It is also known that a fraction of PDGF is bound to the ECM and that thrombin (a proteinase) is responsible for cleavage and release of the membrane-bound form.113 While there is no direct evidence to suggest that MMPs play a role in release or activation of PDGF, by analogy with other proteinases, it is possible that MMPs could also be involved in these processes.

Conclusions

ARDS is a clinically important disease representing a large burden of ICU admissions and with few proven therapies beyond lung protective mechanical ventilation. The pathophysiology of ALI/ARDS involves an excessive inflammatory response resulting in accumulation of protein-rich pulmonary edema fluid through a disrupted alveolar-capillary barrier. MMPs and PTKs are novel participants in these processes, but their involvement is complex, encompassing multiple cell types and resulting in divergent effects along the path to lung injury. In the current manuscript, we have provided examples of how MMPs are able to trigger signaling pathways controlled by PTKs, both receptor and nonreceptor, promoting pro-inflammatory and injurious responses. These interactions are bidirectional and we have discussed how tyrosine kinase-dependent pathways can trigger secretion of MMPs and other proteinases. With these limitations in mind, further study is warranted. A better understanding of the role of MMPs and PTKs in ALI/ARDS may improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of this common lung disease, as well as provide new candidate prognostic biomarkers and targets for novel therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following conflicts: Dr Downey has received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH for travel to a scientific conference. Drs Aschner, Zemans, and Yamashita have reported that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALI

acute lung injury

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NRTK

nonreceptor tyrosine kinase

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PDGFR

platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PTK

protein tyrosine kinase

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- SFK

Src family kinase

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- VILI

ventilator-induced lung injury

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This review was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health [HL103772 (R. L. Z.) and HL090669 (G. P. D.)].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.Matthay MA, Zemans RL. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:147-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2731-2740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):276-285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. ; ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1334-1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1685-1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phua J, Badia JR, Adhikari NK, et al. Has mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome decreased over time? A systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(3):220-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(8):795-803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1293-1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware LB, Koyama T, Zhao Z, et al. Biomarkers of lung epithelial injury and inflammation distinguish severe sepsis patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2013;17(5):R253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang W, McCaig LA, Veldhuizen RA, Yao LJ, Lewis JF. Mechanisms responsible for surfactant changes in sepsis-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(6):1074-1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt EP, Lee WL, Zemans RL, Yamashita C, Downey GP. On, around, and through: neutrophil-endothelial interactions in innate immunity. Physiology (Bethesda). 2011;26(5):334-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zemans RL, Colgan SP, Downey GP. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils: mechanisms and implications for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(5):519-535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee WL, Downey GP. Neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(1):1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittet JF, Mackersie RC, Martin TR, Matthay MA. Biological markers of acute lung injury: prognostic and pathogenetic significance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(4):1187-1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Günther A, Mosavi P, Heinemann S, et al. Alveolar fibrin formation caused by enhanced procoagulant and depressed fibrinolytic capacities in severe pneumonia. Comparison with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):454-462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Downey GP, Suter PM, Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Conventional mechanical ventilation is associated with bronchoalveolar lavage-induced activation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes: a possible mechanism to explain the systemic consequences of ventilator-induced lung injury in patients with ARDS. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(6):1426-1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan E, Villar J, Slutsky AS. Novel approaches to minimize ventilator-induced lung injury. BMC Med. 2013;11:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seals DF, Courtneidge SA. The ADAMs family of metalloproteases: multidomain proteins with multiple functions. Genes Dev. 2003;17(1):7-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(3):221-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadler-Olsen E, Fadnes B, Sylte I, Uhlin-Hansen L, Winberg JO. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in health and disease. FEBS J. 2011;278(1):28-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: an overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253(1-2):269-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463-516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khokha R, Murthy A, Weiss A. Metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(9):649-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MJ, Gough AK, Devlin J, et al. Serum MMP-3 and MMP-1 and progression of joint damage in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(1):83-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heymans S, Lupu F, Terclavers S, et al. Loss or inhibition of uPA or MMP-9 attenuates LV remodeling and dysfunction after acute pressure overload in mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(1):15-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosas IO, Richards TJ, Konishi K, et al. MMP1 and MMP7 as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchinami H, Seki E, Brenner DA, D’Armiento J. Loss of MMP 13 attenuates murine hepatic injury and fibrosis during cholestasis. Hepatology. 2006;44(2):420-429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuo F, Kaminski N, Eugui E, et al. Gene expression analysis reveals matrilysin as a key regulator of pulmonary fibrosis in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6292-6297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Kane CM, McKeown SW, Perkins GD, et al. Salbutamol up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the alveolar space in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(7):2242-2249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torii K, Iida K, Miyazaki Y, et al. Higher concentrations of matrix metalloproteinases in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(1):43-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanchou J, Corbel M, Tanguy M, et al. Imbalance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9 and MMP-2) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(2):536-542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartog CM, Wermelt JA, Sommerfeld CO, Eichler W, Dalhoff K, Braun J. Pulmonary matrix metalloproteinase excess in hospital-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(4):593-598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricou B, Nicod L, Lacraz S, Welgus HG, Suter PM, Dayer JM. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMP in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(2 Pt 1):346-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fligiel SE, Standiford T, Fligiel HM, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in acute lung injury. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(4):422-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pugin J, Verghese G, Widmer MC, Matthay MA. The alveolar space is the site of intense inflammatory and profibrotic reactions in the early phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(2):304-312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haro H, Crawford HC, Fingleton B, Shinomiya K, Spengler DM, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase-7-dependent release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in a model of herniated disc resorption. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(2):143-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhainaut JF, Charpentier J, Chiche JD. Transforming growth factor-beta: a mediator of cell regulation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4)(suppl):S258-S264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittet JF, Griffiths MJ, Geiser T, et al. TGF-beta is a critical mediator of acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(12):1537-1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-beta and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14(2):163-176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeda S, Dean DD, Gomez R, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. The first stage of transforming growth factor beta1 activation is release of the large latent complex from the extracellular matrix of growth plate chondrocytes by matrix vesicle stromelysin-1 (MMP-3). Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;70(1):54-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karsdal MA, Larsen L, Engsig MT, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta controls the conversion of osteoblasts into osteocytes by blocking osteoblast apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(46):44061-44067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dallas SL, Rosser JL, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Proteolysis of latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-binding protein-1 by osteoclasts. A cellular mechanism for release of TGF-beta from bone matrix. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(24):21352-21360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schönbeck U, Mach F, Libby P. Generation of biologically active IL-1 beta by matrix metalloproteinases: a novel caspase-1-independent pathway of IL-1 beta processing. J Immunol. 1998;161(7):3340-3346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ito A, Mukaiyama A, Itoh Y, et al. Degradation of interleukin 1beta by matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(25):14657-14660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parks WC, Wilson CL, López-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(8):617-629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Lint P, Libert C. Chemokine and cytokine processing by matrix metalloproteinases and its effect on leukocyte migration and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(6):1375-1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warner RL, Beltran L, Younkin EM, et al. Role of stromelysin 1 and gelatinase B in experimental acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24(5):537-544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nerusu KC, Warner RL, Bhagavathula N, McClintock SD, Johnson KJ, Varani J. Matrix metalloproteinase-3 (stromelysin-1) in acute inflammatory tissue injury. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83(2):169-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamashita CM, Dolgonos L, Zemans RL, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 3 is a mediator of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(4):1733-1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Redente EF, Jacobsen KM, Solomon JJ, et al. Age and sex dimorphisms contribute to the severity of bleomycin-induced lung injury and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(4):L510-L518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL, Parks WC. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury. Cell. 2002;111(5):635-646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kruidenier L, MacDonald TT, Collins JE, Pender SL, Sanderson IR. Myofibroblast matrix metalloproteinases activate the neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL7 from intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(1):127-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson ER, Matthay MA. Acute lung injury: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23(4):243-252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suga M, Iyonaga K, Okamoto T, et al. Characteristic elevation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(5):1949-1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lochter A, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. The significance of matrix metalloproteinases during early stages of tumor progression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:180-193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uhlig S, Ranieri M, Slutsky AS. Biotrauma hypothesis of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(2):314-315., author reply 315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: from the bench to the bedside. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(1):24-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albaiceta GM, Gutierrez-Fernández A, García-Prieto E, et al. Absence or inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-8 decreases ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43(5):555-563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Albaiceta GM, Gutiérrez-Fernández A, Parra D, et al. Lack of matrix metalloproteinase-9 worsens ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294(3):L535-L543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crosby LM, Waters CM. Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298(6):L715-L731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGuire JK, Li Q, Parks WC. Matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7) mediates E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in injured lung epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(6):1831-1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buckley S, Driscoll B, Shi W, Anderson K, Warburton D. Migration and gelatinases in cultured fetal, adult, and hyperoxic alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281(2):L427-L434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pei D. Matrix metalloproteinases target protease-activated receptors on the tumor cell surface. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(3):207-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hubbard SR, Till JH. Protein tyrosine kinase structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:373-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schlessinger J, Ullrich A. Growth factor signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Neuron. 1992;9(3):383-391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okutani D, Lodyga M, Han B, Liu M. Src protein tyrosine kinase family and acute inflammatory responses. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291(2):L129-L141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coulthard MG, Morgan M, Woodruff TM, et al. Eph/Ephrin signaling in injury and inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(5):1493-1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Severgnini M, Takahashi S, Rozo LM, et al. Activation of the STAT pathway in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286(6):L1282-L1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khadaroo RG, He R, Parodo J, et al. The role of the Src family of tyrosine kinases after oxidant-induced lung injury in vivo. Surgery. 2004;136(2):483-488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hanke JH, Gardner JP, Dow RL, et al. Discovery of a novel, potent, and Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Study of Lck- and FynT-dependent T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(2):695-701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Severgnini M, Takahashi S, Tu P, et al. Inhibition of the Src and Jak kinases protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):858-867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu M, Qin Y, Liu J, Tanswell AK, Post M. Mechanical strain induces pp60src activation and translocation to cytoskeleton in fetal rat lung cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(12):7066-7071 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parker JC, Ivey CL, Tucker A. Phosphotyrosine phosphatase and tyrosine kinase inhibition modulate airway pressure-induced lung injury. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;85(5):1753-1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yan SR, Berton G. Regulation of Src family tyrosine kinase activities in adherent human neutrophils. Evidence that reactive oxygen intermediates produced by adherent neutrophils increase the activity of the p58c-fgr and p53/56lyn tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(38):23464-23471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yan SR, Fumagalli L, Berton G. Activation of p58c-fgr and p53/56lyn in adherent human neutrophils: evidence for a role of divalent cations in regulating neutrophil adhesion and protein tyrosine kinase activities. J Inflamm. 1995;45(4):297-311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lowell CA, Fumagalli L, Berton G. Deficiency of Src family kinases p59/61hck and p58c-fgr results in defective adhesion-dependent neutrophil functions. J Cell Biol. 1996;133(4):895-910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mócsai A, Jakus Z, Vántus T, Berton G, Lowell CA, Ligeti E. Kinase pathways in chemoattractant-induced degranulation of neutrophils: the role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activated by Src family kinases. J Immunol. 2000;164(8):4321-4331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Voelkel NF, Vandivier RW, Tuder RM. Vascular endothelial growth factor in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(2):L209-L221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mazor R, Alsaigh T, Shaked H, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-1-mediated up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-2 in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(1):598-607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(4):681-691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang H, Keiser JA. Vascular endothelial growth factor upregulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of flt-1. Circ Res. 1998;83(8):832-840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pufe T, Harde V, Petersen W, Goldring MB, Tillmann B, Mentlein R. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces matrix metalloproteinase expression in immortalized chondrocytes. J Pathol. 2004;202(3):367-374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cross MJ, Dixelius J, Matsumoto T, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF-receptor signal transduction. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28(9):488-494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eliceiri BP, Paul R, Schwartzberg PL, Hood JD, Leng J, Cheresh DA. Selective requirement for Src kinases during VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Mol Cell. 1999;4(6):915-924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thickett DR, Armstrong L, Christie SJ, Millar AB. Vascular endothelial growth factor may contribute to increased vascular permeability in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(9):1601-1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Finigan JH, Downey GP, Kern JA. Human epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(4):395-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Puddicombe SM, Polosa R, Richter A, et al. Involvement of the epidermal growth factor receptor in epithelial repair in asthma. FASEB J. 2000;14(10):1362-1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Savla U, Waters CM. Mechanical strain inhibits repair of airway epithelium in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(6 pt 1):L883-L892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ryan RM, Mineo-Kuhn MM, Kramer CM, Finkelstein JN. Growth factors alter neonatal type II alveolar epithelial cell proliferation. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(1 Pt 1):L17-L22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leslie CC, McCormick-Shannon K, Shannon JM, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor is a mitogen for rat alveolar type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16(4):379-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Geiser T, Jarreau PH, Atabai K, Matthay MA. Interleukin-1beta augments in vitro alveolar epithelial repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279(6):L1184-L1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bierman A, Yerrapureddy A, Reddy NM, Hassoun PM, Reddy SP. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) regulates mechanical ventilation-induced lung injury in mice. Transl Res. 2008;152(6):265-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Correa-Meyer E, Pesce L, Guerrero C, Sznajder JI. Cyclic stretch activates ERK1/2 via G proteins and EGFR in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282(5):L883-L891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Faress JA, Nethery DE, Kern EF, et al. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis is attenuated by a monoclonal antibody targeting HER2. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;103(6):2077-2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Terakado M, Gon Y, Sekiyama A, et al. The Rac1/JNK pathway is critical for EGFR-dependent barrier formation in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300(1):L56-L63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen SP, Zhou B, Willis BC, et al. Effects of transdifferentiation and EGF on claudin isoform expression in alveolar epithelial cells. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;98(1):322-328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang Z, Song T, Jin Y, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor regulates MT1-MMP and MMP-2 synthesis in SiHa cells via both PI3-K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(6):998-1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dreymueller D, Martin C, Schumacher J, et al. Smooth muscle cells relay acute pulmonary inflammation via distinct ADAM17/ErbB axes. J Immunol. 2014;192(2):722-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lackmann M, Boyd AW. Eph, a protein family coming of age: more confusion, insight, or complexity? Sci Signal. 2008;1(15):re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Larson J, Schomberg S, Schroeder W, Carpenter TC. Endothelial EphA receptor stimulation increases lung vascular permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295(3):L431-L439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fang WB, Ireton RC, Zhuang G, Takahashi T, Reynolds A, Chen J. Overexpression of EPHA2 receptor destabilizes adherens junctions via a RhoA-dependent mechanism. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(pt 3):358-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chan B, Sukhatme VP. Receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 mediates thrombin-induced upregulation of ICAM-1 in endothelial cells in vitro. Thromb Res. 2009;123(5):745-752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ivanov AI, Steiner AA, Scheck AC, Romanovsky AA. Expression of Eph receptors and their ligands, ephrins, during lipopolysaccharide fever in rats. Physiol Genomics. 2005;21(2):152-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cercone MA, Schroeder W, Schomberg S, Carpenter TC. EphA2 receptor mediates increased vascular permeability in lung injury due to viral infection and hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297(5):L856-L863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carpenter TC, Schroeder W, Stenmark KR, Schmidt EP. Eph-A2 promotes permeability and inflammatory responses to bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(1):40-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim IK, Rhee CK, Yeo CD, et al. Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, imatinib and nilotinib, in murine lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury during neutropenia recovery. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):R114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hoyle GW, Li J, Finkelstein JB, et al. Emphysematous lesions, inflammation, and fibrosis in the lungs of transgenic mice overexpressing platelet-derived growth factor. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(6):1763-1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Snyder LS, Hertz MI, Peterson MS, et al. Acute lung injury. Pathogenesis of intraalveolar fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1991;88(2):663-673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rhee CK, Lee SH, Yoon HK, et al. Effect of nilotinib on bleomycin-induced acute lung injury and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Respiration. 2011;82(3):273-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sun X, Gao X, Zhou L, Sun L, Lu C. PDGF-BB-induced MT1-MMP expression regulates proliferation and invasion of mesenchymal stem cells in 3-dimensional collagen via MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling. Cell Signal. 2013;25(5):1279-1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Taipale J, Keski-Oja J. Growth factors in the extracellular matrix. FASEB J. 1997;11(1):51-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]