Abstract

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP, MIM 135100) is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder and the most disabling condition of heterotopic (extraskeletal) ossification in humans. Mutations in the ACVR1 gene (MIM 102576) were identified as a genetic cause of FOP [Shore et al., 2006]. Most patients with FOP have the same recurrent single nucleotide change c.617G>A, p.R206H in the ACVR1 gene. Furthermore, 11 other mutations in the ACVR1 gene have been described as a cause of FOP. Here, we review phenotypic and molecular findings of 130 cases of FOP reported in the literature from 1982 to April 2014 and discuss possible genotype-phenotype correlations in FOP patients.

Key Words: ACVR1, FOP, Great toe malformations, Heterotopic ossifications, Progressive immobility

Introduction

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP, MIM 135100) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder and the most disabling condition of heterotopic (extraskeletal) ossification in humans. FOP is very rare with a worldwide prevalence of approximately one case in 2 million individuals. No ethnic, racial or geographic predisposition has been described [Shore et al., 2005].

Congenital malformation of the great toes in terms of hypoplasia or aplasia and fibular deviation is noted in almost all patients and hypoplasia of the thumbs in about half of the patients. Other recurrent described features are conductive hearing loss and teeth anomalies. The heterotopic ossifications appear progressively and do not only lead to immobility of all major joints, but also to respiratory insufficiency due to severe scoliosis. There is no effective treatment so far. There are 800 patients with a known diagnosis of FOP worldwide.

History of FOP

The first case of FOP was presumably described by the French physician Guy Patin in 1692, but the first clear description was made by the London surgeon John Freke in 1736. He reported on a 14-year-old ‘boy of healthy look’ with ‘many large swellings on his back, that arise from all the vertebrae of the neck and reach down to the os sacrum. They likewise arise from every rib of his body, and joining together in all parts of his back, as the ramifications of coral do, they make, as it were, a fixed bony pair of bodice.’ [Peltier, 1998].

The name myositis ossificans progressiva was assigned to the condition by von Dusch in 1868. The term fibrositis was changed to myositis in the early 20th century to acknowledge the early inflammatory events that occur in the aponeuroses, fasciae and tendons in addition to the skeletal muscles. McKusick [1956] noted that the muscles were only secondarily affected and came back to the term fibrodysplasia in 1972, a term first suggested by Bauer and Bode [1940].

Perhaps the most famous of all patients with FOP was Harry Raymond Eastlack Jr. Late in his life, Eastlack made the decision to bequeath his body to medicine so that physicians and scientists in future generations could study and learn about FOP. His skeleton is on display at The Mutter Museum of The College of Physicians in Philadelphia, USA [Kaplan et al., 2005a].

Clinical Aspects

In the newborn period, usually there is no sign of FOP, except for congenital malformation of the great toes present in many patients. This malformation can vary from a fibular deviation of the great toes to their complete absence; however, this is not observed in all patients with FOP.

During childhood, many patients experience sporadic episodes of soft tissue swelling (flare-ups) which can spontaneously regress or turn into heterotopic bone in muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fascia. During the course of life, these formations of heterotopic bone usually span over joints and lead to ankylosis of these joints and progressive immobility, so that many patients lose their ability to sit in childhood or adolescence, to walk and to open their mouth at a later point in life. This restriction can lead to severe weight loss. Immobility is cumulative, and most patients are wheelchair-bound by the end of the second decade of life.

Typically, heterotopic ossifications follow specific anatomic patterns. They begin in the dorsal, proximal, axial, and cranial regions of the body (neck, shoulders, back) and progress into ventral, caudal and distal regions (trunk and limbs) [Pignolo et al., 2005]. The cervical spine often becomes ankylosed early in life. There are some tissues, in which heterotopic ossifications never occur. These are smooth muscles, cardiac muscles, diaphragm, tongue, and extra-ocular muscles [Pignolo et al., 2011] (fig. 1).

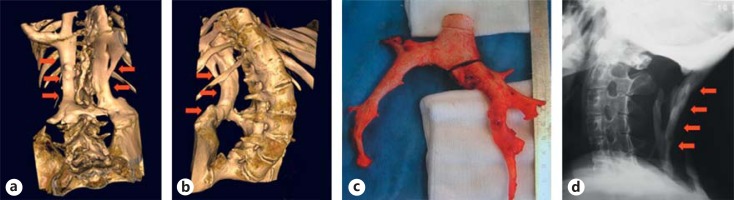

Fig. 1.

Heterotopic ossifications in FOP patients. a, b 3D-CT imaging of the lumbar region and presentation of additional bone tissue beside the spine with fusion to the pelvic bones. c Surgical specimen of heterotopic bone after removal. Histologically, the bone tissue shows a normal healthy structure. d Presentation of heterotopic bone causing immobility in the neck region by X-ray. Image from Stefanova et al. [2012].

Many patients develop severe scoliosis and, thus, develop thoracic insufficiency syndrome with strongly reduced lung capacity and other severe consequences such as pneumonia and right-sided heart failure [Kaplan and Glaser, 2005].

Soft tissue injury, muscular stretching, overexertion and fatigue, intramuscular injections and injections for dental anesthetics, falls, and influenza-like illnesses can induce FOP flare-ups. Also surgical attempts to remove heterotopic bone usually lead to episodes of explosive new bone formation at the surgical site [Kaplan et al., 2005a; Pignolo et al., 2011].

Some patients with FOP have cervical spine abnormalities, which include large posterior elements, tall and narrow vertebral bodies, and fusion of the facet joints between C2 and C7 [Schaffer et al., 2005]. Other skeletal features associated with FOP are short malformed thumbs, clinodactyly, short broad femoral necks, and proximal medial tibial osteochondromas [Kaplan et al., 1994, 2009; Deirmengian et al., 2008].

Hearing loss has been described in FOP patients. It is usually conductive and may be due to middle ear ossification, but some patients have a sensorineural hearing impairment, involving the inner ear, cochlea or the auditory nerve [Levy et al., 1999].

Increasing evidence suggests that involvement of the inflammatory component of the immune system plays a critical role in FOP [Kaplan et al., 2007]. The presence of cells of the immune system, such as macrophages, lymphocytes and mast cells in early FOP lesions, flare-ups following viral infections, the intermittent timing of flare-ups, and the beneficial response of early flare-ups to corticosteroids support the involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of FOP [Kaplan et al., 2005b].

Genetic Aspects

Heterozygous mutations in the ACVR1 gene (MIM 102576) were identified as a cause of FOP [Shore et al., 2006]. Activin A receptor, type I (ACVR1) is a mediator of BMP signaling. The bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) are a family of highly conserved extracellular signaling proteins that have crucial function in a wide variety of cells and tissues during embryonic development and postnatal life. They regulate cell differentiation [Urist, 1965; Wozney, 1988; Shi and Massagué, 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Massagué et al., 2005; Gazzerro and Canalis, 2006; Wagner, 2007].

ACVR1 consists of 4 domains: ligand-binding domain, transmembrane domain, glycine serine (GS) rich domain, and the protein kinase domain. The GS-rich domain is critical for binding and activation of SMAD signaling and is a binding site for FKBP12, an inhibitory protein that prevents leaky activation of the receptor in the absence of ligand.

The ACVR1 gene consists of 11 exons; the first 2 exons are noncoding. There are 8 transcripts. The information on exons in this article refers to transcript ENST00000263640 (Ensembl database).

Most patients with FOP have the same recurrent single nucleotide change in ACVR1. This ‘classical’ mutation (c.617G>A, p.R206H) has been reported in ∼200 patients in the literature so far. Detailed phenotypic information is available for 106 reported patients. Protein structural homology modeling predicted that the amino acid substitution in the ACVR1 protein caused by the p.R206H mutation results in a conformational change of the receptor that alters its ligand-binding properties and activity [Shore et al., 2006; Groppe et al., 2007].

After the ‘classical’ mutation c.617G>A in the ACVR1 gene was discovered, other ACVR1 mutations were found in 14 further patients. However, the mutation c.617G>A remains the most common mutation and can be found in around 90% of the FOP patients.

To date, all ACVR1 mutations evaluated for enhanced BMP signaling are gain-of-function mutations [Kaplan et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2009] (fig. 2).

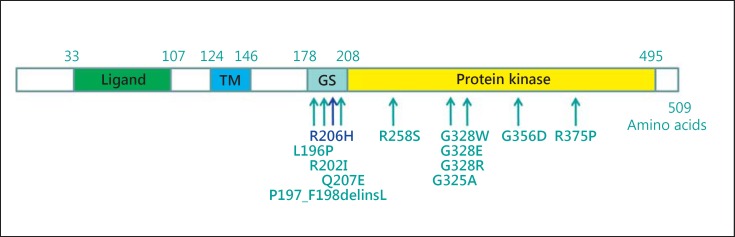

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the ACVR1 protein and all mutations described up to date. The classical mutation p.R206H is located in the GS-rich domain. All known mutations up to date are located in the GS-rich domain and the protein kinase domain. Modified after Kaplan et al. [2009].

The clinical aspects described here are typical for patients harboring the recurrent mutation p.R206H in the ACVR1 gene. In addition, there are patients with atypical FOP phenotypes (Kaplan et al. [2009] suggested the terms FOP-plus and FOP variants), in whom an atypical course of disease, additional features or missing typical features can be seen. These patients preferentially have mutations different from the common mutation p.R206H. So far, the following additional or variable clinical features in FOP patients have been described: intraarticular synovial osteochondromatosis of hips, degenerative joint disease of hips, sparse/thin scalp hair (more prominent in the second decade), mild cognitive impairment, severe growth retardation, cataracts, retinal detachment, childhood glaucoma, craniopharyngioma, persistence of primary teeth into adulthood, anatomic abnormalities of the cerebellum, diffuse cerebral dysfunction with seizures, polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, primary amenorrhea, aplastic anemia, hypospadias, and cerebral cavernous malformations [Kaplan et al., 2009; Pignolo et al., 2011].

In the following, we describe phenotypic details of FOP patients according to the mutation as reported in the literature (see also table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the features of the reported patients

| Mutation in the ACVR1 gene | c.617G>A (p.R206H) | c.619C>G (p.Q207E) | c.1067G>A (p.G356D) | c.982G>T (p.G328W) | c.983G>A (p.G328E) | c.982G>A (p.G328R) | c.774G>C, c.774G>T (P.R258S) | c.1124G>C (p.R375P) | c.587T>C (p.L196P) | c.590–592delCTT (p.P197_F198delinsL) | c.605G>T (p.R202I) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 106 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 + a family of 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| References | Zhang et al. (2013); Stefanova et al. (2012); Carvalho et al. (2010); Kaplan et al. (2009); Nakajima et al. (2007); Al-Haggar et al. (2013) | Kaplan et al. (2009), | Kaplan et al. (2009); Stefanova et al. (2012); Zhang et al. (2013); Furuya et al. (2008); Cohen et al. (1993) | Kaplan et al. (2009); Stefanova et al. (2012); Connor and Evans (1982) | Kaplan et al. (2009); Carvalho et al. (2010); Stefanova et al. (2012); Connor and Evans (1982) | Kaplan et al. (2009); Virdi et al. (1999) | Bocciardi et al. (2009); Ratbi et al. (2010); Morales-Piga et al. (2012); Zhang et al. (2013) | Kaplan et al. (2009) | Gregson et al. (2011); Nakahara et al. (2014) | Kaplan et al. (2009) | Petrie et al. (2009) |

| Gender | m, f | 1 m | 4 m, 2 f | 2f | 3f | 2 m, 3 f | 3 f, 3 m | 1 f | 1 f, 1 m | 1 f | 1 f |

| Onset of ossifications | 2 – 4 ys (variation 1–15 ys) | 1 y | 4 mo, 2 ys, 3 ys, 10 ys, 15 ys; no ossifications in 1/6 | 2 ys, 8 ys | 1 – 2 ys | 13, 21, 22, and 26 ys; no ossifications in 1/5 | 4, 6, 7, 8, and 14, 15 ys | flare-ups of soft tussue at 14 ys, ossifications at 40 ys | 17 ys (l/2) and late onset (1/2) | 11 ys | 14 ys |

| Progression of ossifications in characteristic anatomic patterns | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no; HO on the site of trauma or surgery (4/5) | no | no | |||

| Ossifications after trauma of surgical intervention | >50% | yes; no spontaneous HO (4/5) | |||||||||

| Course of disease in terms of immobilization | severe | severe | variable to severe | mild, slow progression | mild, no significant mobility restrictions | mild, ambulatory in the 5th life decade | very mild (2/2) | severe, fast progression after late onset | Unclear | ||

| Scoliosis and thorax insufficiency | early, 3rd–4th life decade | early | nr | nr | nr | no | no | nr | no | ||

| Malformation of toes | fibular deviation in almost 100% | fibular deviation | complete or almost complete aplasia of the great toes (5/6) | aplasia of the great toes (2/2) | complex malformations of toes and fingers with reduction defects of all digits with missing nails, oligodactyly and syndactyly | monophalangism of the great toes (1/5), no or very mild hypoplasia (4/5) | no or very mild hypoplasia of the great toes (5/5) | no | no (1/2); slightly short thumbs, short toes, lack of distal interphalangeal joint of 4th and 5th toe; (1/2) | no | one short great toe |

| Malformation of fingers | thumb hypoplasia in at least 50% | thumb hypoplasia in some | hypoplasia of thumbs (2/2) | hypoplasia of thumbs (1/5) | nr | ||||||

| Sparse hair/alopecia | in some patients | yes (at least 1/6) | yes (2/2) | yes (2/3) | yes (2/2) | no | |||||

| Facial features | thin skin and missing eyebrows, small mandibula | thin skin and missing eyebrows, small mandibula | thin skin and missing eyebrows | thin skin and missing eyebrows | |||||||

| Teeth anomalies | ∼ 25 – 30% | persistence of primary teeth (1/6) | oligodontia | no | |||||||

| Hearing impairment | ∼ 25 – 30% | conductive (1/1) | conductive (2/2) | no | |||||||

| Primary amenorrhea | in 2/2 female patients | yes, gonadal aplasia (1/3) | no | ||||||||

| Cognitive impairment | no | no | no | mild (2/2) | mild (3/3) | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Other features untypical for FOP | hypospadias (1/4) | dysgenesis of the corpus callosum (1/3) | cerebral cavernous malformations (1/5); cerebellar hypoplasia (1/5) | ||||||||

The number of patients with the described feature is given in parentheses. HO = Heterotopic ossifications; mo = months; nr = feature not reported in any patient; y(s) = year(s).

Patients with the Classical Mutation c.617G>A (p.R206H) in Exon 6 of the ACVR1 Gene

More than 200 patients with the mutation p.R206H in the ACVR1 gene have been reported in the literature so far. Detailed phenotypic information is available for 106 reported patients (69 reported by Zhang et al. [2013], 11 reported by Stefanova et al. [2012], 16 reported by Carvalho et al. [2010], 6 reported by Kaplan et al. [2009], 3 reported by Nakajima et al. [2007], and 1 reported by Al-Haggar et al. [2013]). The first heterotopic ossifications or flare-ups in this group of patients appear very often between 2 and 4 years of age varying from 1-15 years. In almost all patients, the heterotopic ossifications begin on the back, neck and shoulder region. The period for making the correct diagnosis of FOP after the manifestation lasts ∼2-3 years. The patients were often initially misdiagnosed with other conditions such as juvenile fibromatosis, neurofibromatosis, lipoblastomatosis, unknown malignity, parotitis, and proliferative or nodular fasciitis. In many patients, flare-ups or beginning ossifications were biopsied and histologically examined. However, the histological examination is not a helpful diagnostic tool for FOP. In some of the patients, the lesions were surgically removed. More than a half of the patients report an increase of ossifications after trauma of surgical intervention. In the course of the disease, typical bony bridges developed between vertebrae and scalp, vertebrae and pelvis, and on the ribs. As a result of these bridges, most patients had first signs of immobilization between the cervical spine and scalp, thoracic spine and ribs, and lumbar spine and pelvis. Scoliosis is very common and is more pronounced if heterotopic ossifications appear early (fig. 3). Most of the patients have very limited lung capacity in the third to fourth decade of life.

Fig. 3.

Patients with the ‘classical’ mutation c.617G>A (p.R206H) in the ACVR1 gene. Heterotopic ossifications appear in a typical anatomic pattern in all patients. Some patients show heterotopic ossifications after trauma. In the typical course of disease, patients develop severe scoliosis and thorax insufficiency. Image from Stefanova et al. [2012].

Some of the patients show sparse hair, thin facial skin and missing eyebrows, leading to a possibly recognizable craniofacial aspect in FOP patients [Kaplan et al., 2009; Stefanova et al., 2012; Al-Haggar et al., 2013]. Most of the patients show ulnar deviation of the great toes (fig. 4). Literature data report on at least 50% of the FOP patients having thumb hypoplasia (fig. 5). Teeth anomalies and conductive hearing loss are present in ∼25-30% of the patients with the classical mutation.

Fig. 4.

Feet of patients with the common mutation c.617G>A (p.R206H). The very first sign of FOP is a congenital malformation of the great toes (brachydactyly and fibular deviation), present in almost all patients with the ‘classical’ ACVR1 mutation. Image from Stefanova et al. [2012].

Fig. 5.

Some patients with c.617G>A (p.R206H) in the ACVR1 gene show short thumbs. Image from Stefanova et al. [2012].

Patients with the Mutation c.1067G>A (p.G356D) in Exon 9 of the ACRV1 Gene

One patient with the mutation c.1067G>A (p.G356D) has been reported first by Kaplan et al. [2009] (as patient 17) and later by Stefanova et al. [2012] (as patient 21). Furthermore, 3 patients (2 female and 1 male) with this mutation have been reported by Kaplan et al. [2009] (as patients 15, 16 and 18), one patient by Zhang et al. [2013] (patient 54), and one patient by Furuya et al. [2008] as well as by Cohen et al. [1993] (62-year-old male). First ossifications in these patients appeared at the ages of 4 months, 2 years, 3 6/12 years, 10 years, and 15 years. One of the patients had not developed any heterotopic ossifications until the age of 5 years (fig. 6). The patient reported by Furuya et al. [2008] lost the ability to walk at age 36 years and became bedridden at age 55 years. He showed no respiratory failure. All patients showed severe malformations of the great toes, in some cases asymmetrical. Five of 6 patients have complete or almost complete aplasia of the great toes (one of them unilateral). One patient has persistence of primary teeth into adulthood. Primary amenorrhea was present in both female patients in this group. One patient presented with hypospadias. Alopecia, sparse hair and eyebrows were also present in some of the patients.

Fig. 6.

Patient with the mutation c.1067G>A (p.G356D) in the ACVR1 gene, reported by Kaplan et al. [2009] and Stefanova et al. [2012]. At the age of 5 years, the boy has no heterotopic bone formation or mobility restriction. Image from Stefanova et al. [2012].

Patients with the Mutation c.982G>T (p.G328W) in Exon 8 of the ACRV1 Gene

Two female patients are known with the amino acid change p.G328W. One of them has been reported by Kaplan et al. [2009] (as patient 11) and Stefanova et al. [2012] (as patient 11). Another reported patient known to have the p.G328W mutation has been reported by Kaplan et al. [2009] (as patient 12) and Connor and Evans [1982] (as patient 2). The first ossifications appeared at the age of 2 and 8 years. Both patients show aplasia of the great toes and hypoplasia of the thumbs. In the second decade, sparse hair and eyebrows became evident, the hair growth velocity slowed down dramatically. Both patients have mild cognitive impairment and conductive hearing impairment.

Patients with the Mutation c.983G>A (p.G328E) in Exon 8 of the ACRV1 Gene

Three patients with the mutation p.G328E have been evaluated by Kaplan et al. [2009] (patients 13 and 14) and Carvalho et al. [2009] (patient 17). The same patients are also reported by Smith et al. [1976], Connor and Evans [1982] (as patient 32) and Stefanova et al. [2012] (as patient 20). All 3 patients have complex malformations of the toes and fingers with reduction defects involving all digits with missing nails, oligodactyly and syndactyly. The onset of the ossifications was at the age of 1-2 years. Two of 3 patients have sparse hair that grows very slowly, and the eyebrows are sparse or missing. The sparse hair and eyebrows became more prominent in the second decade of life. All 3 patients show mild cognitive impairment. One patient has primary amenorrhea due to gonadal aplasia as well as dysgenesis of the corpus callosum. Oligodontia has also been reported.

Patients with the Mutation c.982G>A (p.G328R) in Exon 8 of the ACRV1 Gene

Five patients from 3 families with the above-mentioned amino acid change have been reported so far. Kaplan et al. [2009] reported 2 unrelated patients (patients 8 and 10) and 1 familial case (pat/family 9) with 3 affected family members. This family was reported previously by Virdi et al. [1999] (family 2).

All but one patient have no or very mild hypoplasia of the great toes. Only one patient had a malformation of the great toes, which was corrected surgically. Postsurgical photographs show monophalangism of the great toes. One patient has small thumbs. In all patients, the first ossifications appeared after trauma or surgery at ages 13, 21, 22, and 26 years. One patient did not develop any ossifications. The course of disease is mild with a slow progression. One patient shows cerebral cavernous malformations, and another patient has cerebellar hypoplasia.

Patients with the Mutations c.774G>C and c.774G>T (p.R258S) in Exon 7 of the ACVR1 Gene

Bocciardi et al. [2009] described 2 females (as patients12 and 17) aged 4 and 14 years with the mutation c.774G>C (p.R258S) in the ACVR1 gene. Ratbi et al. [2010] reported a 12-year-old male patient with the mutation c.774G>T (p.R258S). The ages of ossification onset were 4, 8 and 14 years, respectively. They had no or very mild hypoplasia of the great toes. The course of the disease is not clearly described in the reports. We assume a milder than the ‘classical’ course of disease, since no significant restrictions of mobility have been reported. Two patients with the same amino acid change p.R258S and the mutations c.774G>C (patient 6, female, 42 years old) and c.774G>T (patient 13, male, 29 years old) were reported by Morales-Piga et al. [2012]. These 2 patients had only mild abnormalities of their great toes. The first heterotopic ossifications appeared at ages 6 and 15, and the patients lacked the typical anatomic and developmental pattern of heterotopic ossification. The course of disease was milder than the classical course. As an additional feature, baldness was described in the 2 patients.

Zhang et al. [2013] reported a Chinese patient with the mutation c.774G>C, p.R258S (patient 7), who developed first heterotopic ossifications at age 7. In this report, it is noted in the summary table that the patient has ‘normal great toes or minimal changes’ as well as normal thumbs. As a contradiction, it is noted in the manuscript that the patient has severe digital malformations. Therefore, the phenotype of the digital malformations in this patient is not completely clear.

Patients with the Mutation c.1124G>C (p.R375P) in Exon 9 of the ACRV1 Gene

One female patient with the amino acid change p.R375P was described by Kaplan et al. [2009] (patient 19). The disease manifested with flare-ups at 14 years of age and resulted in restricted mobility of the cervical spine and shoulders, and heterotopic ossifications in the neck, chest and right hip at the age of 40; however, she was still ambulatory. There were no malformations of the great toes and no additional features described.

Patients with the Mutation c.587T>C (p.L196P) in Exon 6 of the ACRV1 Gene

Gregson et al. [2011] reported a 45-year-old female patient with the amino acid change p.L196P with late onset of the disease, slow progression, ossifications in typical anatomic patterns and no malformations of the toes or fingers, and no additional features. The patient was ambulatory and had contractures in some major joints. Nakahara et al. [2014] reported a second patient with the same mutation, a 22-year-old man, with first ossifications at the age of 17 years. At age 19, a decreased mobility in his right shoulder was observed, which improved with time. At age 22, he had mildly restricted mobility in his spine and hips. The left little finger showed mild camptodactyly and the thumbs were slightly short. Overall, the toes were short, due to the lack of the distal interphalangeal joint on the fourth and fifth toes.

Patients with the Mutation c.619C>G (p.Q207E) in Exon 6 of the ACRV1 Gene

One patient with this mutation was reported by Kaplan et al. [2009] (as patient 7). He had a ‘classical’ phenotype of FOP with flare-ups and ossifications, beginning in the second year of life. Early scoliosis and thorax insufficiency were reported. His height and weight were <5th percentile for his age.

Patients with the Mutation c.590-592delCTT (p.P197_F198delinsL) in Exon 6 of the ACVR1 Gene

Kaplan et al. [2009] reported one female patient with a deletion of 3 bp in the GS-rich domain of the ACVR1 gene that results in the replacement of the amino acids proline (codon 197) and phenylalanine (codon 198) with leucine (patient 20).

She has clinically and radiographically normal toes. At 11 years of age, a painful flexion contracture of the left hip occurred, and imaging studies showed a poorly defined soft tissue mass of the left iliopsoas muscle. She developed heterotopic ossification with ankylosis of the left hip, and within 6 months, she had ankylosis of all major joints of the axial and appendicular skeleton.

Patients with the Mutation c.605G>T (p.R202I) in Exon 6 of the ACVR1 Gene

Petrie et al. [2009] described a female patient, who was diagnosed clinically with FOP at age 14 years (patient 1). The first presentation was with a painful bony lump over her right scapula after a fall, and clinical examination showed only one short big toe with otherwise normal toes. Subsequently, she developed multiple tender bony swellings, and the apparent toe abnormality confirmed the clinical diagnosis. Her right shoulder was fixed in internal rotation. Fixed-flexion deformities of both elbows were present. Her lumbar spinal movements were restricted. The patient continued to have frequent flare-ups with increased inflammatory lesions over her shoulder joints, neck and jaw, resulting in immobility of the neck within 6 months of clinical presentation.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlation

Considering the presented literature data, individuals with the ‘classical’ p.R206H mutation have an early onset of ossifications (during childhood) that can be triggered by trauma. The course of the disease is usually severe and leads to immobility at early age. Also patients with the mutations p.G328W and p.G328E show early disease onset and severe progression, but the ossifications seem not to be influenced by trauma. Individuals with the mutation p.G356D seem to have later onset of the disease, which could, however, progress quickly. Also the mutations p.G328W and p.G328E are probably associated with early onset and severe disease course, but do not seem to be triggered by trauma. Interestingly, the amino acid change p.G328R in the same codon seems to be associated with a mild disease course and late onset, but ossifications show a high correlation with injury or surgical intervention. The amino acid changes p.R258S, p.R375P and p.L196P seem to be associated with a milder phenotype with less influence on life quality than in patients with other mutations (fig. 7, 8).

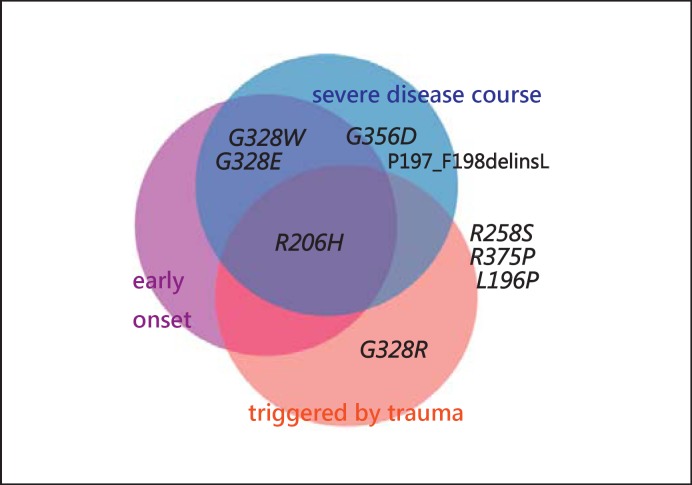

Fig. 7.

Different amino acid changes in the ACVR1 protein and their involvement in the following clinical aspects of FOP: early onset of ossifications, severe disease course, and the trigger of ossifications by trauma or surgery. The changes presented outside the circles seem to correlate with a relatively late disease onset, mild disease course, and no influence of injuries on the development of ossifications.

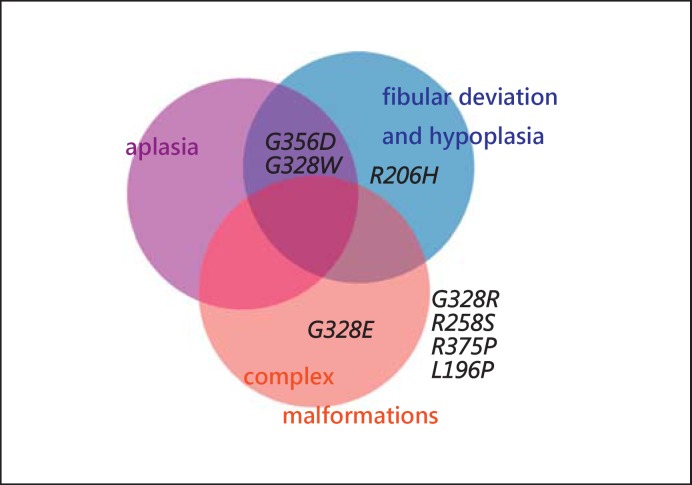

Fig. 8.

Association of the mutations in the ACVR1 gene with great toe malformations. Patients with the ‘classical’ mutation p.R206H usually show great toe malformations, such as fibular deviation and hypoplasia. In patients with the amino acid changes p.G356D and p.G328W, not only fibular deviation and hypoplasia, but also aplasia of the great toes has been observed. Patients with the amino acid change p.G328E have complex digital malformations (oligodactyly and syndactyly), otherwise not seen in FOP patients. The clear reports of patients with the amino acid changes p.G328R, p.R258S, p.R375P, and p.L196P describe mild or no malformations of the great toes.

Stefanova et al. [2012] described 8 patients showing ectodermal features in terms of sparse hair, sparse or missing eyebrows and thin facial skin. In some patients, these features became evident with age. Some patients are reported with slow hair growth, which was also a feature occurring in the second or third decade of life. Hammond et al. [2012] suggested that FOP patients often have longer, narrower faces than age-sex matched controls – males more so than females. In addition, many FOP patients have a small mandible. Variably dysmorphic facial features in the regions of midface and jaw suggested by Hammond et al. [2012] are likely related to the canonical ACVR1 mutation and not described in patients with other mutations so far. Ectodermal features have been described in patients with other mutations too. Especially striking are the sparse hair and sparse eyebrows in patients with the amino acid changes p.G328W and p.G328E.

Intellectual impairment is not thought to be a feature typical for FOP. However, all the reported patients with the mutation c.983G>A (p.G328E) showed mild intellectual impairment. The number of patients with this amino acid change is, however, too small in order to define a genotype-phenotype correlation in terms of cognitive impairment. The ACVR1 protein is not known to have an important function in neurological development.

A statement on genotype-phenotype correlation in terms of features, such as hearing impairment, teeth abnormalities, genital anomalies, and other features rarely described in FOP patients is difficult to make because of the yet small number of patients and the fact that these features are not consistently described in a predominant part of the patients with any mutation.

Summary and Conclusions

The causes of FOP are heterozygous missense mutations that occur in the regions coding for the GS-rich and the protein kinase domains of the ACVR1 gene. The most common missense mutation is the c.617G>A (p.R206H) mutation. Patients with this mutation show rather distinctive and, thus, rather predictable phenotype with early onset of heterotopic ossification (varying between ages 0 and 15 years), relatively early occurring significant motion restriction of the major joints resulting in immobility, and congenital malformations of the great toes and thumbs.

Since the identification of the AVCR1 gene as the responsible gene for FOP by Shore et al. [2006] and this mutation hot spot, more and more mutations in the GS-rich domain and the protein kinase domain of this gene have been described. The actually known patients with a different mutation than the common p.R206H mutation seem to have a phenotype which varies from the ‘classical’ FOP phenotype, especially concerning limb malformations and disease severity (progression and extent of heterotopic ossifications). Also mild mental impairment was noted in some patients with other than the common mutation. In general, FOP is not thought to be associated with specific craniofacial signs, but in some patients specific facial features have been observed [Hammond et al., 2012; Stefanova et al., 2012]. However, the number of patients with ACVR1 mutations different from the p.R206H mutation is still small, so that a definite genotype-phenotype correlation in this group of patients is not yet possible.

References

- 1.Al-Haggar M, Ahmad N, Yahia S, Shams A, Hasaneen B, et al. Sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva in an Egyptian infant with c.617G>A mutation in ACVR1 gene: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Genet. 2013;2013:834605. doi: 10.1155/2013/834605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer KH, Bode W. Erbpathologie der Stützgewebe beim Menschen. Erbbiologie und Erbpathologie körperlicher Zustände und Funktionen. 1940;1:105. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bocciardi R, Bordo D, Di Duca M, Di Rocco M, Ravazzolo R. Mutational analysis of the ACVR1 gene in Italian patients affected with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: confirmations and advancements. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho DR, Navarro MM, Martins BJ, Coelho KE, Mello WD, et al. Mutational screening of ACVR1 gene in Brazilian fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva patients. Clin Genet. 2010;77:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22:233–241. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen RB, Hahn GV, Tabas JA, Peeper J, Levitz CL, et al. The natural history of heterotopic ossification in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: a study of forty-four patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:215–219. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connor JM, Evans DA. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. The clinical features and natural history of 34 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:76–83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B1.7068725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deirmengian GK, Hebela NM, O'Connell M, Glaser DL, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Proximal tibial osteochondromas in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:366–374. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuya H, Ikezoe K, Wang L, Ohyagi Y, Motomura K, et al. A unique case of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva with an ACVR1 mutation, G356D, other than the common mutation (R206H) Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:459–463. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazzerro E, Canalis E. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregson CL, Hollingworth P, Williams M, Petrie KA, Bullock AN, et al. A novel ACVR1 mutation in the glycine/serine-rich domain found in the most benign case of a fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva variant reported to date. Bone. 2011;48:654–658. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groppe JC, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Functional modeling of the ACVR1 (R206H) mutation in FOP. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:87–92. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318126c049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond P, Suttie M, Hennekam RC, Allanson J, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. The face signature of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1368–1380. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan FS, Glaser DL. Thoracic insufficiency syndrome in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005;3:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan FS, Strear CM, Zasloff MA. Radiographic and scintigraphic features of modeling and remodeling in the heterotopic skeleton of patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994. pp. 238–247. [PubMed]

- 16.Kaplan FS, Glaser DL, Pignolo RL, Shore EM. Introduction. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005a;3:175–177. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan FS, Shore EM, Gupta R, Billings PC, Glaser DL, et al. Immunological features of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and the dysregulated BMP4 Pathway. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005b;3:189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan FS, Groppe J, Pignolo RJ, Shore EM. Morphogen receptor genes and metamorphogenes: skeleton keys to metamorphosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1116:113–133. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan FS, Xu M, Seemann P, Connor JM, Glaser DL, et al. Classic and atypical fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) phenotypes are caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor ACVR1. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:379–390. doi: 10.1002/humu.20868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy CE, Lash AT, Janoff HB, Kaplan FS. Conductive hearing loss in individuals with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Am J Audiol. 1999;8:29–33. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(1999/011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massagué J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKusick VA. Hereditable disorders of connective tissue. J Chronic Dis. 1956;3:521–556. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(56)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morales-Piga A, Bachiller-Corral J, Trujillo-Tiebas MJ, Villaverde-Hueso A, Gamir-Gamir ML, et al. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva in Spain: epidemiological, clinical, and genetic aspects. Bone. 2012;51:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakahara Y, Katagiri T, Ogata N, Haga N. ACVR1 (587T>C) mutation in a variant form of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: second report. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:220–224. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakajima M, Haga N, Takikawa K, Manabe N, Nishimura G, Ikegawa S. The ACVR1 617G>A mutation is also recurrent in three Japanese patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:473–475. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peltier LF. A case of extraordinary exostoses on the back of a boy. 1740. John Freke (1688-1756). Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;346:5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrie KA, Lee WH, Bullock AN, Pointon JJ, Smith R, et al. Novel mutations in ACVR1 result in atypical features in two fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva patients. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pignolo RJ, Suda RK, Kaplan FS. The fibrodysplasia ossificans progressive lesion. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metabol. 2005;3:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pignolo RJ, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: clinical and genetic aspects. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:80. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratbi I, Borcciadi R, Regragui A, Ravazzolo R, Sefiani A. Rarely occurring mutation of ACVR1 gene in Moroccan patient with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:119–121. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1283-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaffer AA, Kaplan FS, Tracy MR, O'Brien ML, Dormans JP, et al. Developmental anomalies of the cervical spine in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva are distinctly different from those in patients with Klippel-Feil syndrome: clues from the BMP signaling pathway. Spine. 2005;30:1379–1385. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166619.22832.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Q, Little SC, Xu M, Haupt J, Ast C, et al. The fibrodysplasia ossificans progressive R206H ACVR1 mutation activates BMP independent chondrogenesis and zebrafish embargo ventralization. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3462–3472. doi: 10.1172/JCI37412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shore EM, Feldman GJ, Xu M, Kaplan FS. The genetics of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005;3:201–204. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Cho TJ, et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006;38:525–527. doi: 10.1038/ng1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith R, Russell RG, Woods CG. Myositis ossificans progressiva. Clinical features of eight patients and their response to treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:48–57. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B1.818090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefanova I, Grünberg C, Gillessen-Kaesbach G. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Med Genet. 2012;24:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urist MR. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150:893–899. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3698.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virdi AS, Shore EM, Oreffo RO, Li M, Connor JM, et al. Phenotypic and molecular heterogeneity in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65:250–255. doi: 10.1007/s002239900693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner TU. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in stem cells-one signal, many consequences. FEBS J. 2007;274:2968–2976. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, et al. Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science. 1988;242:1528–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.3201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang W, Zhang K, Song L, Pang J, Ma H, et al. The phenotype and genotype of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva in China: a report of 72 cases. Bone. 2013;57:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]