Abstract

Children produce a deictic gesture for a particular object (point at dog) approximately three months before they produce the verbal label for that object (“dog”) (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005). Gesture thus paves the way for children’s early nouns. We ask here whether the same pattern—gesture preceding and predicting speech—holds for iconic gestures—that is, do gestures that depict actions precede and predict early verbs? We observed spontaneous speech and gestures produced by 40 children (22 girls, 18 boys) from age 14 to 34 months. Children produced their first iconic gestures 6 months later than they produced their first verbs. Thus, unlike the onset of deictic gestures, the onset of iconic gestures conveying action meanings followed, rather than preceded, children’s first verbs. However, iconic gestures increased in frequency at the same time as verbs did and, at that time, began to convey meanings not yet expressed in speech. Our findings suggest that children can use gesture to expand their repertoire of action meanings, but only after they have begun to acquire the verb system underlying their language.

Do iconic gestures pave the way for children’s early verbs?

Young children use gesture to communicate before they produce their first words (Bates, 1976). The earliest gestures children use, typically beginning around 10 months, are deictics—gestures whose referential meaning is given entirely by the context and not by the form of the gesture (e.g., pointing at a bottle to indicate a bottle). At this early stage, deictic gestures offer children a tool to refer to objects before they have words for those objects, and children take advantage of this offer—they produce deictic gestures for objects approximately three months before they produce verbal labels for objects. Moreover, the fact that a child has pointed at a particular object (e.g., a dog) increases the likelihood that the child will learn a word for that object (“dog”) within the next few months, suggesting that early pointing gestures pave the way for children’s first nouns (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005).

But children also use a second type of gesture at this early stage—iconic gestures—gestures that convey actions or attributes associated with objects (e.g., flapping arms to represent a bird flying; Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1985, 1988; see also Iverson, Capirci & Caselli, 1994; Özçalışkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2005a, Özçalışkan, 2005b). The question we ask here is whether iconic gestures pave the way for children’s early verbs in the same way that deictic gestures pave the way for children’s early nouns. There is reason to believe that they do, but also reason to believe that they do not.

Iconic gestures conveying action might pave the way for children’s early verbs

Compared to nouns, verbs present a bigger challenge to children, as they convey relational meanings (Gentner, 1982). Not surprisingly, children typically produce their first nouns before producing their first verbs, and nouns predominate over verbs in early production and comprehension of English (Gentner, 1982, 2006; Goldin-Meadow, Seligman & Gelman, 1976; Huttenlocher & Smiley, 1987; Nelson, 1973), as well as many other spoken languages (e.g., Au, Dapretto & Song, 1994; Gentner, 1982; Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001). Thus, there is ample opportunity for early iconic gestures to speed the acquisition of verbs.

Mapping a symbol onto a referent constitutes a major milestone in language development, and iconicity—the resemblance between a symbol and its referent (Peirce, 1960)—could play an important role in this process. A transparent relationship between a symbol and its referent has the potential to render iconic symbols more readily available to young language learners than ‘true symbols’, which have an arbitrary relation to their referents (Piaget, 1962; Werner & Kaplan, 1963). If so, we might expect to find action meanings conveyed first in iconic gestures.

Do early iconic gestures help bootstrap verbs in the same way that deictic gestures bootstrap nouns? There is evidence that young children can learn and produce a range of iconic gestures—known as baby signs—that indicate actions and attributes associated with an object when those gestures are taught deliberately (rubbing index fingers to convey a spider crawling, raising arms to indicate big size; Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1988). These gestures might serve as perceptual symbols (Barsalou, 1999; Goldstone & Barsalou, 1998) that aid in the acquisition of the corresponding concepts. Moreover, the more iconic gestures children have in their communicative repertoires at one and half years of age, the larger their verbal vocabularies tend to be at age two (Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1988), suggesting a tight link between early iconic gesture use and later verbal vocabulary development (but see Johnston, Durieux & Bloom, 2005, for a review of recent work suggesting little association between use of baby signs and later spoken vocabulary). Finally, children who are learning language in the manual modality (e.g., deaf children learning American Sign Language) produce their first signs several months earlier than children who are learning a spoken language produce their first words (Anderson & Reilly, 2002; Bonvillian, Orlansky & Novack, 1983; Meier & Newport, 1990), although there is disagreement over whether these first productions are true signs or gestures (Volterra & Iverson, 1995), and whether the reported sign advantage for ASL holds for other sign languages (e.g., British Sign Language, Woolfe, Herman, Roy &Woll, 2010). In fact, recent work by Pettenati, Stefanini and Volterra (2010) shows that the early iconic gestures Italian hearing children produce resemble the earliest signs produced by deaf children learning Italian Sign Language, underscoring the difficulty in teasing apart early signs from gestures. Whether or not deaf children’s earliest productions turn out to be signs, this set of studies raises the possibility that the manual modality has an advantage in the emergence of early symbols, lending credence to the hypothesis that early iconic gestures might pave the way for early verb learning.

Iconic gesture conveying action might not pave the way for children’s early verbs

On the other hand, there are reasons to suspect that children’s spontaneous iconic gestures conveying action might not help them learn early verbs. The mapping between symbol and referent is more straightforward for nouns and deictic gestures than it is for verbs and iconic gestures. Concrete nouns map onto the perceptual world in a direct way; they refer to objects and entities that naturally stand out as separate, individuated wholes in the world (Gentner, 1982; Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001; Markman, 1989). In contrast, verbs select from a diffuse set of relational concepts for their referents. Verb meanings capture only a subset of the relational information that can potentially be conveyed, and the particular combinations of relations that verbs convey vary across languages (Bowerman & Choi, 2003; Casad & Langacker, 1985; Gentner, 1981, 1982, 2006; Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001; Talmy 1975; 1983; 2000). Thus, to learn verbs, children must first discover how the language they are learning selects and combines relations (Gentner, 1982, 2006; Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001). According to this hypothesis, for the child to derive verb meanings requires more than just experience with events in the world. It also requires linguistic guidance as to which relations in the world map onto the verbs in the language the child is learning. If this hypothesis is correct, iconic gestures, which children presumably derive from experience with the world, ought not to help much—if at all—in their later verb learning.

The question: Do iconic gestures pave the way for early verbs?

The existing evidence suggests two equally plausible, but contradictory, possibilities: (1) If gesture is an instrument, or even just a harbinger, of new verb meanings, then we would expect children’s first iconic gestures that convey actions to precede the first verbs they produce conveying similar meanings. (2) If, in contrast, verb semantics is sufficiently language-specific that simple iconic gestures conveying actions are not likely to be helpful in bootstrapping verb meanings, then there would be no reason to expect iconic gestures to precede and/or to facilitate verb learning.

To explore the role that iconic gestures play in the emergence of early verbs, we followed 40 children longitudinally and examined their spontaneous speech and gestures. We asked whether the children used iconic gestures to convey action meanings and, if so, whether those gestures were used prior to the onset of verbal labels for the same kinds of action meanings.

METHODS

Sample and data collection

Forty North American children (22 girls, 18 boys) were videotaped with their parents at home every four months from 14 to 34 months. Each videotaped session lasted 90 minutes, amounting to 540 minutes of observation across the six sessions for each individual child. Parents were told to interact with their children as they normally would in their everyday routines and to ignore the experimenter. Sessions typically consisted of free play with toys, book reading, and snack time, but also varied slightly based on the preferences of child and parents. Children’s families constituted a heterogeneous mix in terms of income and ethnicity, and were representative of the demographic range of the greater Chicago area, with the exception that all of the children were being raised as monolingual English speakers.

Coding and analysis

We transcribed all of the communicative words and gestures that the children produced. A gesture or word was coded as communicative if the child made an effort to direct the listener’s attention. Sounds that were reliably used to refer to entities, properties, or actions (“doggie”, “pretty”, “eat”), along with onomatopoeic sounds (e.g., “meow”, “choo-choo”) and conventionalized evaluative sounds (e.g., “oopsie”, “uh-oh”), were counted as words. Ritualized games (e.g., patty cake, itsy bitsy spider) were not counted as gestures, nor were hand movements that directly manipulated objects (e.g., twisting open a jar, hammering a toy peg). Thus, real actions performed on real objects (e.g., twisting the lid of a closed jar) were not included in the analyses even if they conveyed information to the listener (i.e., that the child wanted the jar opened). Pretend actions performed on real or toy objects (e.g., pretending to drink from an empty cup) were also not included in the analyses.

Each gesture was classified into one of three types: (1) Conventional gestures have a form-meaning relation that is prescribed by the culture (e.g., nodding the head to convey yes, shaking the head sideways to convey no, waving the hand to convey goodbye). (2) Deictic gestures indicate concrete objects, persons, or locations in the immediate context (e.g., pointing to a dog to convey dog). (3) Iconic gestures either depict actions (e.g., moving an empty fist forcefully forward to convey throwing; flapping the arms to convey a bird flying) or perceptual features associated with objects (e.g., holding cupped hands in the air to convey the roundness of a ball; placing the palm high above the head to convey the big size of a person). The children produced two other types of gestures that were rare in our data and were thus excluded from all analyses: beat gestures (formless hand movements that convey no semantic information but move in rhythmic relationship with speech to highlight aspects of discourse structure, e.g., flicking the hand or fingers; see McNeill, 1992); and baby signs (gestures deliberately taught by the parents).

The decision to classify an iconic gesture as depicting action or perceptual information was based on form. Iconic gestures that were dynamic in form were coded as conveying action meanings; iconic gestures that were static in form were coded as conveying attribute meanings. The specific meaning gloss assigned to each action iconic gesture (e.g., eating vs. brushing) was based jointly on the form of the gesture and the communicative context—both linguistic and non-linguistic—in which the gesture was produced. Iconic gestures conveying action meanings accounted for the majority of children’s early iconic gestures (76%, M=9.28, SD=8.45); iconic gestures conveying perceptual properties associated with objects accounted for the remaining 24% of children’s iconic gestures (M=3.70, SD=5.15). Given our focus on actions and verbs, we excluded iconic gestures depicting perceptual information because the form of the gesture seems to convey attribute (e.g., round, big) meanings rather than action meanings (e.g., throw, fly). For brevity, in the remainder of this paper we use the term “iconic gesture” to refer only to iconic gestures conveying action meanings. The majority of the iconic gestures children produced across observation sessions co-occurred with speech; the only exception was the first observation session at child age 14 months, in which all iconic gestures conveying action (12/12) were produced without any accompanying speech.

We used similar criteria in classifying words as ‘verbs,’ relying on the form of the spoken word. Only words that are syntactically categorized as verbs in the English language—independent of tense and aspectual marking—were counted as verbs. The only exceptions were the auxiliary “be” and modals (e.g., “can”, “should”, “must”), which were excluded from all verb counts. For words that can be used as either a verb or a noun (e.g., “comb,” “brush”), we relied on the immediate communicative context in which the word was used, as well as the inflectional morphology of the word (e.g., “combing” vs. “my comb”), to determine whether the word was used as a verb or a noun, and included only instances used as verbs. Interestingly, it was at 26 months of age that children first began to use the same word (e.g., “brush”) to convey an action meaning in one instance and an object meaning in another.

In this paper, we specifically focus on the speech and gestures that the children produced to convey action/event meanings, namely verbs (e.g., “eat”, “run”, “push”)1, and iconic gestures depicting actions (e.g., moving fist to mouth repeatedly to convey eating, moving both hands forward forcefully to convey pushing) (see Özçalışkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2005a, Özçalışkan, 2005b, Özçalışkan, 2009, for further details on the other types of gestures and word types that these children produced).

We assessed reliability by having a second coder transcribe a subset of the videotaped sessions. Agreement between coders was 88% (k= .76; N=763) for identifying gestures (i.e., presence or absence of a gesture), 100% (k= 1.0; N=247) for identifying gesture types (i.e., iconic, deictic or conventional) and 91% (k= .86; N=375) for assigning meaning glosses to each gesture. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVAs with age or modality (gesture, speech) as the within subject factors.

RESULTS

Children’s early iconic gestures and early verbs

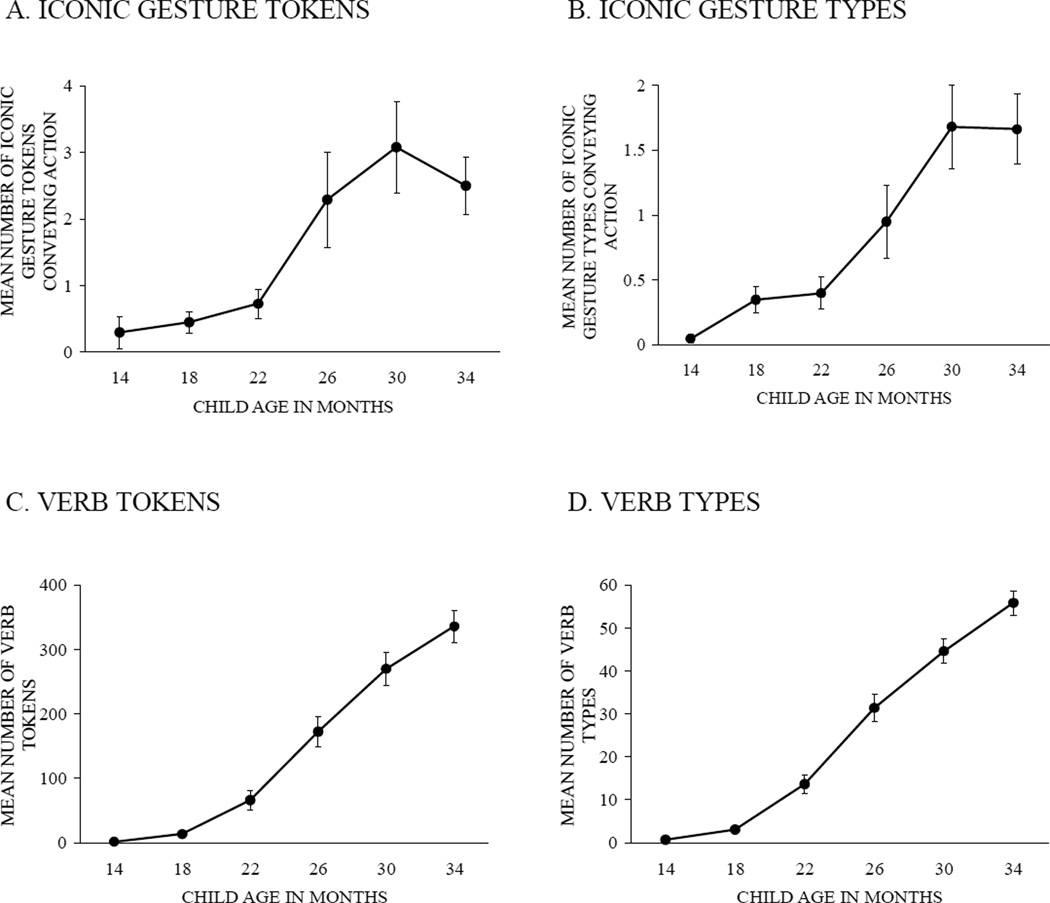

Children produced more and more iconic gestures over time. As can be seen in Figures 1A and 1B (upper panels), children produced more iconic gestures (i.e., tokens) with increasing age, F(5,170)=6.66, p<.001, and conveyed a more diverse array of meanings in their iconic gestures (i.e., types), F(5,170)=10.44, p<.001. There were significant increases in children’s production of iconic gesture tokens and types from 22 to 30 months (p’s<.01, Scheffe) and, by 26 months, children were producing two iconic gesture tokens per session on average.

Fig. 1. Mean number of action iconic gesture tokens (Panel A) and types (Panel B), verb tokens (Panel C) and verb types (Panel D) children produced at 14, 18, 22, 26, 30 and 34 months of age.

Children’s iconic gesture production was much lower than their verb production, as captured here by the different scales on Figures 1A and 1B vs. Figures 1C and 1D.

The number of children producing iconic gestures also increased over time. At 14 months, only 2 children were producing iconic gestures but, by 26 months, more than half of the children (N=22/40) had produced at least one instance of an iconic gesture. By 34 months, all but two of the children in our sample (38/40) had produced an iconic gesture at some point during our observations.2

Children also produced more spoken verbs over time, and at a much higher rate than for iconic gestures. As can be seen in Figures 1C and 1D (lower panels), children produced significantly more verb tokens, F(5,170)=76.14, p<.001, as well as more different verb types, F(5,170)=169.53, p<.001, with increasing age. Between 18 and 26 months, production of verb tokens rose from 13 to 172 per session. There were significant increases in children’s production of verb tokens and verb types between 22 and 26 months (p<.01, Scheffe,) and between 26 and 30 months (p<.001). The number of children producing verbs also increased steadily over time, from 11 children at 14 months to 36 children at 22 months. By 26 months, all 40 children were producing verbs.

Children thus increased their spontaneous production of both iconic gestures and verbs from 14 to 34 months, with the largest jump in production at 26 months. However, the rate of iconic gesture production was very low compared to the rate of verb production (note the difference in scales and in the steepness of the slope in the four graphs in Figure 1). Across the 6 observation sessions, children produced a total of 32,522 verbs, compared to only 371 iconic gestures conveying action meanings. It is also worth pointing out that the rate of iconic gesture production was low compared to the production of deictic and conventional gestures (see Özçalışkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2011, for a description of the distribution of iconic gestures in relation to the other gestures these children produced). We next turn to our main question—do early iconic gestures pave the way for verbs?

The onset of iconic gestures and verbs

We first asked whether children produced their first iconic gesture before producing their first verb. The answer is clearly no. On average, children produced their first iconic gesture at 25.2 months (SD=6.55) and their first spoken verb at 18.2 months, SD=3.26, F(1,39)=38.68, p<.001. Thus, children produced their first iconic gestures an average of 6.3 months (SD=6.5) later than their first verbs. We found the same pattern at the individual level: 29 children produced their first verb before producing their first iconic gesture, compared to 2 children who produced their first iconic gesture before producing their first verb, X2(1)=35.6, p<.001. Of the remaining 9 children, 7 produced their first verb and first iconic gesture during the same observation session, and 2 produced their first verb but had not yet produced an iconic gesture by the last observation session at 34 months. Thus, far from presaging the onset of verbs, iconic gestures were first produced several months after verbs.

We next asked whether gesture preceded speech at the level of individual verbs; that is, whether a particular action meaning was conveyed in gesture before that meaning was conveyed in speech. For example, a child might produce the iconic gesture throw before producing the verb “throw”. We explored this question by classifying the action meanings that children conveyed in their verbs into four categories: (1) the verb meaning was produced only in speech and not in gesture during the six observation sessions, (2) the verb meaning was produced first in speech and later in gesture, (3) the verb meaning was produced first in gesture and later in speech, or (4) the verb meaning was produced in gesture and speech during the same observation session. We found that 98% (M=138.50, SD=61.45) of the meanings children conveyed in their early verbs across the six observation sessions were meanings conveyed uniquely in speech. The remaining few verbs were distributed as follows: 0.06% (M=0.88, SD=1.34) appeared first in speech, 0.04% (M=0.53, SD=0.78) appeared first in gesture, and 1.00% (M=1.55, SD=1.91) appeared in gesture and speech during the same session.

Thus, unlike deictic gestures, which preceded and predicted the onset of children’s nouns, iconic gestures did not precede the onset of children’s verbs. Children not only produced their first verbs earlier than their first iconic gestures, but they also relied almost exclusively on speech to convey their early action meanings.

Do iconic gestures play any role in the acquisition of verbs?

Children showed a large increase in their production of verbs between 22 and 26 months, precisely the period during which they increased their production of iconic gestures. Yet the evidence just discussed argues against the possibility that early iconic gestures pave the way for verb acquisition. This leaves us with a question: Why do these two spurts co-occur?

One possibility is that the spurt in iconic gestures is a direct by-product of the spurt in verbs; that is, a given action meaning becomes available for an iconic gesture only after the corresponding verb has been acquired. If so, children ought to convey the same meanings in gesture as they do in speech, and there should be a high degree of overlap between the kinds of meanings conveyed in early iconic gestures and early verbs.

An alternative possibility is that children use their iconic gestures to convey meanings that they do not yet express in speech, thus expanding their communicative powers. If so, there should be minimal overlap between the kinds of meanings conveyed in early iconic gestures and early verbs. It is, of course, possible that both alternatives are correct, as discussed below.

To explore these alternatives, we classified the types of action meanings children conveyed in their iconic gestures (rather than in their verbs, as in the previous analysis) into four categories: (1) the action meaning was conveyed in gesture and not in speech during the six observation sessions, (2) the meaning was conveyed first in gesture and later in speech, (3) the meaning was conveyed first in speech and later in gesture, or (4) the meaning was conveyed in gesture and speech during the same observation session. Surprisingly, even though the majority of iconic gestures occurred during the last two sessions, only 18% (M=0.88, SD=1.34) were conveyed first in speech and later in gesture. We found that 42% (M=1.8, SD=1.76) of the action meanings that the children conveyed in their iconic gestures were produced uniquely in gesture and an additional 11% (M=0.53, SD=0.78) were conveyed first in gesture and only later in speech. The remaining 29% (M=1.55, SD=1.91) were conveyed in the same session in gesture and speech.

Thus far, the composition of iconic gestures dovetails with the patterns discussed earlier—that the first verb was produced at about 18 months and the first iconic gesture at about 25 months (with 29 of the 40 children producing their first verb before their first iconic gesture), and that 98% of children’s action meanings were conveyed uniquely in speech. Together these findings are consistent with the first possibility—that children learn about possible verb meanings through language and that these meanings are then expressed in gesture. However, the fact that 42% of meanings conveyed in iconic gestures were conveyed uniquely in gesture suggests that the second possibility also holds—that gesture serves to expand a child’s vocabulary, conveying ideas for which the child lacks an existing verb. In fact, many instances of iconic gestures that co-occurred with speech accompanied either bleached verbs (e.g., “go like this” + move fisted empty hand in circles as if stirring [34 months]), modals (“I have to” + move open palm up and down quickly as if bouncing, [30 months]), verb complements (“you making me” + move open palm downward forcefully as if falling‘ [30 months]), nouns (“balloon” + clenches hand in air as if grabbing string of imaginary balloon [30 months]), or onomatopoeic sounds (“ribbit” + jumps fingers up and down as if hopping [26 months]). Thus, it appears that children often used their iconic gestures to fill lexical gaps in their action vocabularies.

Table 1 lists the types of action meanings children conveyed in their iconic gestures at each of the six observation sessions. The majority of the meanings (55%, M=2.62, SD=2.51) that the children expressed in their iconic gestures during this period were symbolic representations of everyday transitive actions: e.g., eating, drawing, brushing, washing, throwing, and lifting. The remaining meanings conveyed in the iconic gestures were symbolic representations of intransitive actions—e.g., flying, bouncing, crawling, swimming (38%, M=1.79, SD=1.58), including directional actions, e.g., going-downward, going-around (7%, M=0.46, SD=0.91). Gestures conveying meanings not found in speech (i.e., filling lexical gaps in their action vocabularies) were just as frequent for transitive actions (N=46, M=1.15, SD= 1.27) as for intransitive actions (N=45, M=1.13, SD= 1.16).

Table 1.

Types of meanings conveyed in iconic gestures

| 14 months | 18 months | 22 months | 26 months | 30 months | 34 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brushing Lifting Wagging |

Biting Bouncing Brushing Drawing Fanning Flying Going-down Hammering Lifting Pinching Riding Swinging Washing |

Crawling Drawing Eating Flying Going around Going up Hugging Lifting Nipping Opening Pounding Pushing Sleeping Throwing |

Attacking Climbing Crawling Drawing Drumming Eating Falling Flapping Flying Going-down Going-up Jumping Knocking Lifting Mixing Moving Playing Pounding Pouring Pushing Shuffling Sleeping Swinging Throwing Touching Washing Waving |

Attacking Biting Blinking Blocking Blowing Bouncing Clenching Crawling Digging Dribbling Dripping Eating Exercising Falling Fanning Flapping Flying Going-around Going-down Going-over Going-out Going-up Grabbing Hammering Hitting Hopping Jumping Knocking Lifting Moving Opening Painting Peeing Playing piano Pulling Pushing Putting Releasing Running Spiraling Sprinkling Stepping Stirring Surfing Swimming Swinging Thinking Throwing Tying Touching Walking |

Attacking Bounding Brushing Closing Crawling Digging Dipping Drawing Falling Flapping Flipping Flying Galloping Going-around Going-up Grabbing Hanging Hopping Hugging Jumping Kicking Messing Moving Opening Pecking Pinching Pouring Pressing Pulling Pushing Receiving Skiing Sleeping Smiling Spitting Stepping Stirring Swimming Thinking Throwing Touching Turning |

In sum, speech was clearly the earliest and the preferred modality for expressing action meanings at this initial stage of language development. Nonetheless, even though iconic gestures emerged later and were produced at much lower rates than verbs, they did allow the children to communicate a set of meanings that they had not yet conveyed in speech. In this sense, iconic gestures served to widen the children’s repertoire of action meanings—even though this uniquely-gesture repertoire was still quite limited compared with the meanings conveyed through early verbs.

DISCUSSION

Previous research has shown that gesture both precedes and is tightly related to changes in early language development (Butcher & Goldin-Meadow, 2000; Goldin-Meadow, 1998, 2003; Goldin-Meadow & Butcher, 2003; Özçalışkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2005a, Özçalışkan, 2009, 2010). Deictic gestures, for example, pave the way for children’s first nouns (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005), and combinations in which gesture conveys one semantic element and speech another (e.g., point at jar + “open”) pave the way for children’s first two-word combinations (“open jar”; Goldin-Meadow & Butcher, 2003; Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005). Producing deictic gestures early in development could merely be a good early indicator of the underlying skills that children are going to need to make linguistic progress. Alternatively, producing deictic gestures could actually play a role in bringing about linguistic progress, either by providing children with the opportunity to “practice” referring to objects before they have the verbal means to do so (Goldin-Meadow, 2003; 2007); or by making it more likely that children will receive verbal input when it is most useful (e.g., a mother responds to her child’s point at a duck by saying, “yes, that’s a duck,” thus exposing the child to the word “duck” just when he has ducks on his mind (Golinkoff, 1986; Goldin-Meadow, Goodrich, Sauer, & Iverson, 2007; Masur, 1982).

In this paper, we explored whether iconic gestures serve the same function for verbs as deictic gestures do for nouns. We found that they do not. In fact, children produced their first iconic gestures 6 months later than they produced their first verbs. Thus, unlike the onset of deictic gestures, which precede and predict children’s first nouns, the onset of iconic gestures conveying action meanings did not precede children’s first verbs. Nonetheless, children frequently used their iconic gestures to convey a different set of meanings than they conveyed in their early verbs. In this way, the children used gesture to expand their repertoire of action meanings.

Why do children produce so few iconic gestures early in development?

We have shown that children produce most of their action meanings in speech before producing them in gesture. We consider four possible explanations for this finding. The first possibility is that iconic action gestures might be relatively difficult to produce motorically. In other words, the difficulty may be in the production of the symbol itself. However, at least some iconic gestures involve nothing more than moving a pointing finger across space (e.g., moving a point down to indicate downward trajectory), and even iconic gestures of this type are not used frequently before 26 months.

A second possibility is that the frequency of iconic gestures in parental input is low. Parents show a significant increase in their iconic gesture production just around the time their children go through a similar spurt in iconic gesture production, roughly around 26 months of age (Özçalışkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2011), thus displaying patterns in their gesture use that parallel changes that their children go through. As a result, very young children are not exposed to frequent models of iconic gestures (unless their parents have been instructed to provide such models deliberately, as in teaching ‘baby signs’ (see Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1985, 1988; Acredolo, Goodwyn & Abrams, 2006).

Given the scarcity of iconic gestures in early parent input, children might not be getting the same kind of exposure in input that they routinely receive for pointing gestures, which, in turn, might explain why iconic gestures appear later in children’s nonverbal repertoires. There is, in fact, evidence suggesting that children growing up in linguistic environments with richer iconic gesture input, such as Italy, produce a greater variety of iconic gestures, and produce them at an earlier age than children learning English in North America (Capirci, Contaldo, Caselli & Volterra, 2005; Iverson, Capirci, Volterra & Goldin-Meadow, 2008; Volterra, Caselli, Capirci & Pizzuto, 2005). Future training studies in which the number of iconic action gestures children receive in their input is manipulated are needed to determine whether early exposure to iconic gestures has an impact on children’s production of iconic gestures—and whether those gestures, in turn, play a role in children’s later acquisition of verbs.

A third possible explanation for the low number of iconic gestures children produce early in development could lie in the conceptual difficulties involved in producing iconic gesture itself. Iconic gestures—unlike pointing gestures—involve representing a referent with a particular symbol and thus are likely to impose greater cognitive demands than deictic gestures, which involve using the same form (the index finger) for all referents. If, in fact, iconic gestures are cognitively demanding, they might even compete with verbs in conveying particular action meanings, rather than complementing them (Tomasello, 2008). As suggested by Liszkowski (2010), words might be easier to use as symbols than gestures simply because words are not iconic; in contrast, iconic gestures rely on actions to do their representational work. Using an iconic gesture to represent an action involves both “decoupling the action schema from an action goal and re-interpreting it as standing in for something else” (Lizkowski, p.28); words do not need to be de-coupled or re-interpreted. The added difficulty of this dual task might make iconic gestures difficult—more difficult than arbitrary gestures (see DeLoache, 2004, for related discussions). There is, in fact, evidence to support this possibility (Namy & Waxman, 1998; Namy, 2001; Namy, Campbell, & Tomasello, 2004; Tolar, Lederberg, Gokhale & Tomasello, 2007). In a series of gesture comprehension experiments, Namy and her colleagues (2004) found that, at 18 months, children are as likely to associate an arbitrary gesture with an object (moving the hand sideways to represent a rabbit) as an iconic gesture (hopping two fingers up and down to represent the rabbit), suggesting that the children may not recognize the iconic relation between hand movement and object. It is not until 26 months that children seem to discover the iconic possibilities of gesture, at which point they briefly lose the ability to make arbitrary mappings and make only iconic mappings. Along the same lines, deaf children learning American Sign Language acquire signs that are arbitrary in form as early as signs that are iconic (Orlansky & Bonvilian, 1984), suggesting that deaf children do not recognize the iconicity in the signs they are learning. Interestingly, the children in our study showed a steep increase in the number of iconic gestures that they spontaneously produced at 26 months, the age at which children first became aware of iconicity in gesture in Namy’s gesture comprehension studies (Namy et al., 2004; Namy, 2008).

In a related vein, iconic gestures might require the types of complex representational abilities that do not develop until sometime between ages 2 and 3. For example, it is during this period that children begin to grasp the representational relation between a miniature scale model of a room (symbol) and the real sized room (referent) and can correctly search for toys in the real room when provided only with information about the hiding location in the model room (see DeLoache, 2004, for a review). It is also during this time that we see increases in symbolic play (Bach, under review; Leslie, 1987; Lillard, 1993). Symbolic play provides children with opportunities to use empty-handed movements (e.g., pretending to pour juice from an empty toy pitcher), which could serve as precursors to iconic action gestures (e.g., using a pouring gesture to ask mother to pour juice). Thus, the relatively late emergence of iconic gesture might be closely tied to, and explained by, changes in other cognitive skills.

Finally, the fourth possible explanation for the low number of iconic gestures children produce early in development lies in the mapping between the symbol and its referent, rather than properties of the symbol itself. As discussed earlier, unlike concrete nouns which tend to denote the same types of entities cross-linguistically, verbs (even “concrete” verbs, such as verbs of motion) show a variable mapping between concepts and words across languages (Bowerman, 1996; Bowerman & Choi, 2003; Gentner, 1981, 1982; 2006; Talmy, 1975, 1983) and are, in general, hard words to learn (Gentner, 2006; Gleitman et al., 2005). Consistent with this reasoning, there is considerable evidence suggesting that nouns dominate over verbs in children’s early vocabularies cross-linguistically (e.g., Au et al., 1994; Bornstein et. al, 2004; Gentner, 1982, 2006; Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001; Tardiff, Gelman & Xu, 1999).3 Gentner (1982, 2006) suggested that the slow acquisition of verbs (relative to nouns occurring equally often or even less often in a child’s input) results from the fact that verb meanings, which vary across languages, cannot be derived simply from experience with the world—in contrast to the meanings of concrete basic-level nouns. That is, “…for verbs and other relational terms, children must discover how their language combines and lexicalizes the elements of the perceptual field” (Gentner, 1982, pp. 323–5). Further, verbs express relations between entities, and relational concepts are, in general, slower to be learned than object concepts. Studies by Gleitman and colleagues (Gillette, Gleitman, Gleitman, & Lederer, 1999; Gleitman, Cassidy, Nappa, Papafragou & Trueswell, 2005) support the claim that it is hard to derive verb meanings purely from world experience; adults find it more difficult to identify the referent of a verb than to identify the referent of a noun when asked to watch a videotape of a mother-child interaction and guess the word using only nonverbal context.

Under this hypothesis, the difficulty involved in learning verbs stems from having to work out which aspects of the world are incorporated into verb meanings in the particular language that the child is learning, If this hypothesis is correct, iconic gestures, which are derived from world experience, are not likely to be much help in acquiring verbs. In fact, children have to choose which pieces of an action or relation to incorporate in an iconic gesture to communicate effectively (just as they must do for verbs). Thus, iconic gestures may be no easier to produce, and may even be harder, than verbs.

Whatever the reason, children produce their first verbs several months before they produce their first iconic gestures. But we do see a noticeable increase in children’s iconic gesture production at just around the time they go through a surge in verb production. Once children begin to understand how verbs work in their language and begin to produce them routinely, they may develop a sense of possible verb meanings and begin to be aware of the lexical gaps they have in their verb vocabularies. Having a pattern for how to lexicalize action meanings, they might then begin to use iconic gestures to fill those gaps, the pattern we observed in our data.

Does verb learning foster the use of gestures for actions and events?

The above line of reasoning suggests that learning verbs might pave the way for children to use iconic gestures. Children may learn how to extract relational meanings by observing and using verbs, which are directly modeled for them in their conversations with adults. If this hypothesis is correct, it leads to the intriguing prediction that children learning languages that show relatively early acquisition of verbs (i.e., greater verb-to-noun ratios) will also begin to produce iconic action gestures earlier than children who are learning less ‘verb-friendly’ languages, such as English. Interestingly, previous research with children learning Turkish—a language in which parental discourse patterns encourage verb use (Küntay & Slobin, 1996)—suggests that this might be the case. On average, children learning Turkish develop verb vocabularies earlier than children learning English (Aksu-Koç & Slobin, 1985), and their iconic gesture production also spurts at an earlier age (Furman, Özyürek & Küntay, 2010). Furman et al. (2010) found that many of the children learning Turkish were routinely using iconic gestures conveying action meanings by 19 months of age, seven months earlier than children learning English.

This pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that verb learning gives children a kind of template or guide for extracting relational meanings from the world, which can be used in constructing iconic gestures. Initially, many iconic gestures reflect meanings already incorporated in the children’s verbs. But, at some point, children become sufficiently adept to want to go beyond the meanings they have learned, and they may use new iconic gestures to do so.

Under this hypothesis, we would predict that children’s growing understanding of verbs should influence the kinds of iconic gestures they produce. The types of action meanings that the children in our study conveyed in gesture provide some evidence for the hypothesis (see Table 1). Sixty percent of the iconic gestures that the children used conveyed information about how an action should be carried out—that is, its manner (e.g., crawling, bouncing, throwing, kicking)—and only 10% conveyed information about the action’s direction—its path (e.g., going down, going-up, going-around).4 This pattern mirrors the predominance of manner over path verbs in the English language, in general (Talmy, 1975; 2000), and, more specifically, in the early verbs that English-learning children produce, that is, the predominance of manner over path verbs (Özçalışkan, 2009; Özçalışkan & Slobin, 1999; Slobin, 2004). It is important to note that manner is not the default pattern in iconic gestures. Deaf children whose hearing losses prevent them from acquiring the spoken language around them and whose hearing parents do not expose them to sign language invent their own gesture systems to communicate with the hearing individuals in their worlds. These children are more likely to produce path information than manner information in their home-made gestures (Zheng & Goldin-Meadow, 2002), suggesting that manner is not necessarily easier to convey in the manual modality than path and is certainly not the default pattern. In light of these findings, our data suggest that the early iconic gestures that the children in our study produced are influenced by the language-specific patterns of the verb semantics in English.

Our findings also extend previous work showing language-specific patterns in the iconic gestures that older children produce when talking about spatial scenes. Gullberg, Hendricks and Hickmann (2008) studied 4- and 6-year-old children learning French, a language that (unlike English) has a predominance of path over manner verbs (Talmy, 1975; 2000), and found that, in both speech and gesture, children conveyed predominantly path information. Taken together, these findings provide further evidence for the close-coupling between linguistic and gestural expressions of simple actions—possibly even a shared conceptual representation that underlies both gesture and speech production (see Kita & Özyürek, 2003).

In sum, our results show that, unlike deictic gestures, which precede and predict children’s first nouns, iconic gestures do not pave the way for children’s first verbs. In fact, the reverse may be true. Children are far more likely to express their initial action meanings in speech than in gesture. However, iconic gestures increase in frequency at the same time as verbs do and, interestingly, at that time begin to convey a small number of meanings not yet expressed in speech. Thus, we suggest that iconic gestures may offer young children a technique for filling in lexical gaps in their action vocabularies. Children take advantage of this technique, but only after they have begun to acquire the verb system underlying their language.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kristi Schonwald and Jason Voigt for their administrative and technical help, and the project research assistants for their help in collecting and transcribing the data. We also thank the reviewers for their helpful comments. The research presented in this paper is supported by grants from NSF (SLC: SBE-0541957) and NIH (PO1 HD406-05) to second and third authors, respectively.

Footnotes

The acquisition patterns conveying attribute meanings (i.e., perceptual properties associated with objects) were exactly the same. At 14 months, only 2 children produced two instances of iconic gestures conveying perceptual information. The use of iconic gestures conveying attributes continued to remain low both at 18 months (7 gestures) and at 22 months (9 gestures), with only 5 children producing gestures of this type. As with iconic gestures conveying action, there was a large increase at 26 months, with 13 of the children producing a total of 51 iconic gestures conveying perceptual information at this age.

Verbs can convey pure action, but they can also convey other kinds of events. For example, “stir” conveys a kind of action, but “mix” indicates a change of state (increased homogeneity) without specifying the particular action by which this change was achieved—a distinction that is not easily captured in gesture. For brevity, we hereafter use the term “action” to refer to both types of meanings.

Gentner’s (1982) hypothesis that nouns cross-linguistically predominate over verbs in early acquisition has led to challenges from researchers studying acquisition in non-Indo-European languages. It has been particularly relevant to study ‘verb-friendly’ languages—i.e., those in which aspects of the input language should promote verb learning. These include languages whose grammar allows for omitting nouns in sentences (pro-drop), as in Mandarin (Tardiff, 1996), and Korean (Choi & Gopnik, 1995); or those with verbs whose meanings incorporate features of their objects, as in Tzeltal (Brown, 1998); or those with parental discourse patterns that emphasize verbs over nouns, as in Kaluli (Schiefflin, 1985) and Turkish (Ketrez & Aksu-Koç, 2004; Küntay & Slobin, 1996). Some early studies using data from transcribed sessions argued that noun dominance did not appear in Mandarin (Tardiff, 1996) or Korean (Choi & Gopnik, 1995). However, studies using vocabulary checklists have verified the predicted predominance of nouns over verbs in early vocabulary, even in verb-friendly languages such as Mandarin (Tardiff, Gelman & Xu, 1999), Korean (Au et al., 1994: Pae, 1993), Navajo (Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001), and Tzeltal (Brown, Gentner and Braun, 2005). Likewise, studies using parental diaries have shown noun dominance in Kaluli (Shieffelin; see Gentner, 1982) and Turkish (Nain; see Gentner, 1982). It appears that some of the early conclusions were based on data using inadequate methodology, such as transcripts of fairly brief sessions (see Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001, and Pine, Lieven & Rowland, 1996, for methodological discussions). Importantly, the degree of noun dominance over verbs is generally lower in these verb-friendly languages than in English (Gentner, 1982; Gentner & Boroditsky, 2001; Tardiff, Gelman & Xu, 1999). This is consistent with the idea that early vocabularies are shaped by the salience of words in the linguistic input as well as by the ease of picking out their conceptual referents in the world.

The remaining 30% of the iconic gestures that the children produced conveyed neither manner nor path information (e.g., sleeping, eating, opening, thinking).

REFERENCES

- Acredolo LP, Goodwyn SW. Symbolic gesturing in language development. Human Development. 1985;28:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Acredolo LP, Goodwyn SW. Symbolic gesturing in normal infants. Child Development. 1988;59:450–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acredolo LP, Goodwyn SW, Abrams D. Baby signs How to talk with your baby before your baby can talk. McGraw Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aksu-Koç A, Slobin DI. The acquisition of Turkish. In: Slobin DI, editor. The crosslinguistic language of acquisition. Vol.1 The data. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1985. pp. 839–878. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D, Reilly J. The MacArthur communicative development inventory: Normative data for American Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2002;7(2):83–106. doi: 10.1093/deafed/7.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au TK, Dapretto M, Song Y. Input vs. constraints: Early word acquisition in Korean and English. Journal of Memory and Language. 1994;33(5):567–582. [Google Scholar]

- Bach T. Pretense and the abstraction of relational categories. under review [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW. Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22(4):577–660. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E. Language and context. New York: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bonvillian JD, Orlansky MO, Novack LL. Developmental milestones: Sign language acquisition and motor development. Child Development. 1983;54(6):1435–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote L, Maital S, Painter K, Park SY, Pascual L, Pecheux MG, Ruel J, Venuti P, Vyt A. Cross-linguistic analysis of vocabulary in young children: Spanish, Dutch, French, Hebrew, Italian, Korean, and American English. Child Development. 2004;75(4):1115–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman M. Learning how to structure space for language: A crosslinguistic perspective. In: Bloom P, Peterson MA, Nadel L, Garrett MF, editors. Language and space. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1996. pp. 385–436. [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman M, Choi S. Space under construction: Language-specific spatial categorization in first language acquisition. In: Gentner D, Goldin-Meadow S, editors. Language in mind: Advances in the study of language and cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003. pp. 387–428. [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. Children’s first verbs in Tzeltal: evidence for an early verb category. Linguistics. 1998;36:713–53. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher C, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesture and the transition from one- to two-word speech: When hand and mouth come together. In: McNeill D, editor. Language and gesture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 235–258. [Google Scholar]

- Capirci O, Contaldo A, Caselli MC, Volterra V. From action to language through gesture: A longitudinal perspective. Gesture. 2005;5(1):155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Casad EH, Langacker R. ‘Inside’ and ‘outside’ in Cora grammar. International Journal of American Linguistics. 1985;51(3):247–281. [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Gopnik A. Early acquisition of verbs in Korean: A cross-linguistic study. Journal of Child Language. 1995;22(3):497–530. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900009934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS. Becoming symbol-minded. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8(2):66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman R, Özyürek A, Küntay A. Early language-specificity in Turkish children’s caused motion expressions in speech and gesture. In: Franich K, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Boston Conference on Language Development. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 2010. pp. 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. Some interesting differences between nouns and verbs. Cognition and Brain Theory. 1981;4(2):161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. Why nouns are learned before verbs: Linguistic relativity versus natural partitioning. In: Kuczaj SA, editor. Language Development: Vol.2. Language, thought and culture. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1982. pp. 301–334. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. Why verbs are hard to learn. In: Hirsh-Pasek K, Michnick Golinkoff R, editors. Action meets word: How children learn verbs. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 544–564. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D, Boroditsky L. Individuation, relativity and early word learning. In: Bowerman M, Levinson S, editors. Language acquisition and conceptual development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 215–256. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette J, Gleitman H, Gleitman L, Lederer A. Human simulations of vocabulary learning. Cognition. 1999;73(2):135–176. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleitman LR, Cassidy K, Nappa R, Papafragou A, Trueswell JC. Hard words. Language Learning and Development. 2005;1(1):23–64. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S. The development of gesture and speech as an integrated system. In: Iverson JM, Goldin-Meadow S, editors. The nature and functions of gesture in children's communications. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998. pp. 29–42. in the New Directions for Child Development series, No. 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S. Hearing Gesture: How our hands help us think. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S. Pointing sets the stage for learning language — and creating language. Child Development. 2007;78(3):741–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Butcher C. Pointing toward two-word speech in young children. In: Kita S, editor. Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet. N.J: Earlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Goodrich W, Sauer E, Iverson JM. Young children use their hands to tell their mothers what to say. Developmental Science. 2007;10(6):778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Seligman MEP, Gelman R. Language in the two-year old: Receptive and productive stages. Cognition. 1976;4(2):189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone RL, Barsalou LW. Reuniting perception and cognition. Cognition. 1998;65(2):231–262. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(97)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golinkoff RM. ‘I beg your pardon?’: the preverbal negotiation of failed messages. Journal of Child Language. 1986;13(3):455–476. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900006826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg M, Hendricks H, Hickmann M. Learning to talk and gesture about motion in French. First Language. 2008;28(2):200–236. [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Smiley P. Early word meanings: The case of object names. Cognitive Psychology. 1987;19:63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JM, Capirci O, Caselli MC. From communication to language in two modalities. Cognitive Development. 1994;9(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JM, Capirci O, Volterra V, Goldin-Meadow S. Learning to talk in a gesture-rich world : Early communication in Italian vs. American children. First Language. 2008;28(2):164–181. doi: 10.1177/0142723707087736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JM, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological Science. 2005;16(5):368–371. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JC, Durieux-Smith A, Bloom K. Teaching gestural signs to infants to advance child development: A review of the evidence. First Language. 2005;25(2):235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ketrez NF, Aksu-Koç A. Early nominal morphology: emergence of case and number. In: Voeikova M, Stephany U, editors. The development of number and case in the first language acquisition: A crosslinguistic perspective. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 2009. pp. 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kita S, Özyürek A. What does crosslinguistic variation in semantic coordination of speech and gesture reveal? Evidence for an interface representation of spatial thinking and speaking. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;48(1):16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Küntay A, Slobin DI. Listening to a Turkish mother : some puzzles for acquisition. In: Slobin DI, Gerhardt J, Kyratzis A, Guo J, editors. Social Interaction, social context and language. Mahwah, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie AM. Pretense and representation: The origins of theory of mind. Psychological Review. 1987;94(4):412–426. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard AS. Pretend play skills and the child’s theory of mind. Child Development. 1993;64(2):348–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizkowski U. Deictic and other gestures in infancy: Deicticos y otros gestos en la infancia. Accion Psicologica. 2010;7(2):21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Markman EM. Categorization and naming in children: Problems of induction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF. Mothers’ responses to infants’ object-related gestures: influences on lexical development. Journal of Child Language. 1982;9(1):23–30. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill D. Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Meier RP, Newport EL. Out of the hands of babes: On a possible sign advantage in language acquisition. Language. 1990;66(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Namy LL. What’s in a name when it isn’t a word? 17-month-olds’ mapping of nonverbal symbols to object categories. Infancy. 2001;2(1):73–86. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0201_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy LL. Recognition of iconicity does not come for free. Developmental Science. 2008;11(6):841–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy LL, Campbell AL, Tomasello M. The changing role of iconicity in non-verbal symbol learning: A U-Shaped trajectory in the acquisition of arbitrary gestures. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2004;5(1):37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Namy LL, Waxman S. Words and symbolic gestures: Infants’ interpreations of different forms of symbolic reference. Child Development. 1998;69(2):295–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K. Structure and strategy in learning to talk. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1973;38:1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Orlansky MD, Bonvillian JD. The role of iconicity in early sign language acquisition. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1984;49(3):287–292. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4903.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş. Learning to talk about spatial motion in language-specific ways. In: Guo J, Lieven E, Ervin-Tripp S, Budwig N, Nakamura K, ŞÖzçalışkan ş, editors. Cross-linguistic approaches to the psychology of language: Research in the tradition of Dan Isaac Slobin. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2009. pp. 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesture is at the cutting edge of early language development. Cognition. 2005a;96(3):B101–B113. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Do parents lead their children by the hand? Journal of Child Language. 2005b;32(3):481–505. doi: 10.1017/s0305000905007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. When gesture-speech combinations do and do not index linguistic change. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2009;28(24):190–217. doi: 10.1080/01690960801956911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Sex differences in language first appear in gesture. Developmental Science. 2010;13(5):752–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Is there an iconic gesture spurt at 26 months? In: Stam G, Ishino M, editors. Integrating Gestures: The Interdisciplinary Nature of Gesture. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Slobin DI. Learning ‘how to search for the frog’: Expression of manner of motion in English, Spanish and Turkish. In: Greenhill A, Littlefield H, Tano C, editors. Proceedings of the 23rd Boston University Conference on Language Development. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 1999. pp. 541–552. [Google Scholar]

- Pae S. Early vocabulary in Korean: Are nouns easier to learn than verbs? Lawrence: Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce CS. In: Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Hartshorne C, Weiss P, Birks A, editors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Pettenati P, Stefanini S, Volterra V. Motoric characteristics of representational gestures produced by young children in a naming task. Journal of Child Language. 2010;37(4):887–911. doi: 10.1017/S0305000909990092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Pine JM, Lieven EVM, Rowland C. Observational and checklist measures of vocabulary composition: what do they mean? Journal of Child Language. 1996;23(3):573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Schieffelin BB. The acquisition of Kaluli. In: Slobin DI, editor. The cross-linguistic study of language acquisition: Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 525–593. [Google Scholar]

- Slobin DI. The many ways to search for a frog: Linguistic typology and the expression of motion events. In: Strömqvist S, Verhoeven L, editors. Relating events in narrative: Typological and contextual perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 219–257. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy L. Semantics and syntax of motion. In: Kimball J, editor. Syntax and semantics. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 181–238. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy L. How language structures space. In: Pick H, Acredolo L, editors. Spatial orientation: Theory, research, and application. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 225–282. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy L. Toward a cognitive semantics—Vol. ll: Typology and process in concept structuring. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff T. Nouns are not always learned before verbs: Evidence from Mandarin speakers’ early vocabularies. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(3):492–504. [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff T, Gelman SA, Xu F. Putting the “noun bias” in context: A comparison of Mandarin and English. Child Development. 1999;70(3):620–635. [Google Scholar]

- Tolar TD, Lederberg AR, Gokhale S, Tomasello M. The development of the ability to recognize the meaning of iconic signs. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2007;13(2):225–240. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enm045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. Origins of human communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Volterra V, Iverson JM. When do modality factors affect the course of language acquisition? In: Emmorey K, Reilly JS, editors. Language, gesture, and space. Hillsdale, N.J: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Volterra V, Caselli MC, Capirci O, Pizzuto E. Gesture and the emergence and development of language. In: Slobin D, Tomasello M, editors. Beyond nature-nurture: Essays in honor of Elizabeth Bates. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Werner H, Kaplan B. Symbol formation: An organismic developmental approach to language and the expression of thought. NY: John Wiley; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Woolfe T, Herman R, Roy P, Woll B. Early vocabulary development in deaf native signers: a British Sign Language adaptation of the communicative development inventories. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(3):322–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Goldin-Meadow S. Thought before language: How deaf and hearing children express motion events across cultures. Cognition. 2002;85(2):145–175. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]