Abstract

BACKGROUND

The outcome of adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) who undergo second salvage therapy has been characterized poorly. This is important with regard to investigational approaches aimed at helping this subset of patients. The objectives of the current study were to predict outcomes and determine the prognostic factors associated with second salvage therapy in patients with ALL.

METHODS

In this study, 288 patients were analyzed who received second salvage therapy for ALL at the authors’ institution.

RESULTS

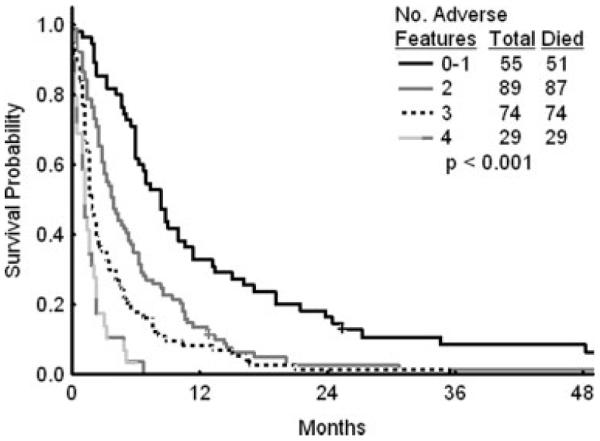

Overall, 53 patients (18%) achieved a complete response (CR). The median remission duration was 7 months and the median survival was 3 months. In multivariate analysis, prognostic factors that were associated independently with achieving CR were duration of first CR and platelet count. Patients with a first CR <36 months and platelet counts <50 × 109/L had an expected CR rate of 7%. In multivariate analysis, prognostic factors that were associated independently with survival were duration of first CR, percentage bone marrow blasts, platelet count, and albumin level. The expected 12-month survival rates for patients with 0 or 1, 2, 3, or 4 adverse factors were 33%, 14%, 8%, and 0%, respectively. A repeat multivariate analysis using landmark assessment at 6 weeks selected achievement of CR as adding significantly to the survival benefit (P = .0001; hazard ratio, 0.51). Only 22 patients (8%) were able to undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantation as second salvage therapy, and their 1-year survival rate was 18%.

CONCLUSIONS

The outcome of adults with ALL undergoing second salvage therapy is poor. Novel effective therapies against ALL are needed in this subset of patients.

Keywords: acute lymphocytic leukemia, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, bone marrow blasts, prognostic factors, remission rate, second salvage therapy, survival

Multiagent, dose-intensive chemotherapy with maintenance and central nervous system prophylaxis has produced cure rates of 70% to 90% in pediatric acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL).1,2 Similar regimens for adult ALL resulted in complete response (CR) rates of 80% to 90% and long-term event-free survival rates of 20% to 40%.3–8 Patients with primary refractory disease or in first recurrence still have CR rates of 30% to 50% on salvage therapy and cure rates of 5% to 20%, depending on several factors, including patient age, duration of first CR, and site of disease recurrence.9–13 Clofarabine, an adenosine nucleoside analogue, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pediatric ALL in recurrence, with emphasis on second salvage.14,15 It is believed that the outcome of adults with ALL who develop disease recurrence after first salvage is extremely poor, but there is scant literature defining their precise outcome. Because ALL in second salvage is an important orphan disease condition in need of new, effective therapeutic interventions, it is important to define the outcome of such patients who are treated with what would be considered ‘standard care’ and to define the factors that influence such outcome. This was the objective of the current analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adults with a diagnosis of ALL who were receiving second salvage therapy after disease recurrence on M. D. Anderson Cancer Center frontline regimens or after referral for recurrent ALL were analyzed. These included patients who were treated after 1980 and received any second salvage therapy regardless of whether they achieved a CR during induction therapy. Patients were treated on protocols that were available during different periods. Criteria for response were standard. A CR was defined as a bone marrow blast count ≤5% in a cellular bone marrow with normalization of peripheral counts, including a granulocyte count ≤109/L and a platelet count ≥100 × 109/L. Criteria for a partial response (PR) were the same as for a CR except for a decrease in bone marrow blasts by 50% but remaining in a range of 6% to 25%. A CR with incomplete platelet recovery referred to achievement of CR but with platelets remaining below 100 × 109/L. Early mortality referred to death within 15 days of the start of therapy; and induction death referred to death during the first course of therapy. All other patients were considered to have resistant disease. Survival was measured from the start of second salvage therapy. Response duration was measured from the date of response until evidence of ALL recurrence. Multivariate analyses to define prognostic factors for achieving CR and for survival were conducted by using established methods.16,17

RESULTS

In all, 288 patients were analyzed. These included 201 patients who had recurrent ALL after frontline therapy at our institution and 87 patients who were referred with recurrent ALL. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 33 years (range, 14-76 years), and 42 patients (15%) were aged ≤60 years. A CR after frontline induction therapy was observed in 224 patients (78%), a CR after first salvage therapy was observed in 99 patients (34%), and 37 patients (13%) never achieved a prior CR.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Group (N=288)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median [range] | 33 [14-76] |

| ≥60 | 42 (15) |

| Response to prior therapy, frontline/salvage 1 | |

| CR/CR | 72 (25) |

| CR/no CR | 152 (53) |

| No CR/CR | 27 (9) |

| No prior CR | 37 (13) |

| Duration of first CR, mo | |

| 0 | 64 (22) |

| 1-11 | 141 (49) |

| 12-35 | 65 (23) |

| ≥36 | 18 (6) |

| Karyotype | |

| Diploid | 79 (27) |

| Philadelphia-positive | 45 (16) |

| Other | 155 (54) |

| Not done | 10 (3) |

| Hemoglobin <10 g/dL | 155 (54) |

| WBC, × 109/L | |

| ≤5 | 133 (46) |

| 5-20 | 89 (31) |

| >20 | 64 (22) |

| Percentage bone marrow blasts | |

| <20 | 28 (10) |

| 20-50 | 51 (19) |

| >50 | 188 (70) |

| Percentage peripheral blasts | |

| 0 | 91 (32) |

| 1-10 | 37 (13) |

| >10 | 154 (55) |

| Platelets, × 109 | |

| <25 | 82 (29) |

| 25-50 | 58 (20) |

| >50 | 146 (51) |

| Albumin, g/L | |

| <3.0 | 55 (21) |

| ≥3.0 | 209 (79) |

| Leukemic cell phenotype | |

| B-cell origin | 125 (43) |

| T-cell origin | 25 (9) |

| Unknown/not done | 138 (48) |

| Year of study | |

| 1980-1991 | 133 (46) |

| 1992-2007 | 155 (54) |

CR indicates complete response; WBC, white blood cell count.

Overall, 53 patients (18%) achieved a CR with second salvage therapy (Table 2). Response by treatment regimen is shown in Table 3. Twenty-two patients underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation as second salvage for active disease with preparative regimens, including total body irradiation (TBI) in 11 patients and non-TBI regimens in 11 patients. The donor was a related matched sibling in 20 patients and a matched unrelated donor in 2 patients. Overall, 9 patients (41%) achieved a CR (Table 3). Seven patients received salvage therapy with single-agent clofarabine (n = 5) or with clofarabine combinations (n = 2): No responses were observed. Response by pretreatment characteristics is shown in Table 4.

TABLE 2.

Response (n=288)

| Response | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Complete response | 53 (18) |

| Early death <2 wk | 27 (9) |

| Induction death | 39 (14) |

| Resistant disease | 169 (59) |

TABLE 3.

Response by Therapy

| Therapy | No. of Patients | No. of CRs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| VAD/hyper-CVAD | 61 | 17 (28) |

| Cytarabine combinations | 54 | 17 (32) |

| Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation | 22 | 9 (41) |

| Methotrexate-asparaginase combinations | 52 | 3 (6) |

| Other combinations | 29 | 4 (14) |

| Single agent | 70 | 3 (4) |

CRs indicates complete responses; VAD, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; hyper-CVAD, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.

TABLE 4.

Prognostic Factors for Response and Survival

| Characteristic | Response, % | P | 1-Year Survival, % |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| <60 | 18 | 14 | ||

| ≥60 | 19 | .60 | 7 | .18 |

| Response to prior therapy, frontline/salvage 1 |

||||

| CR/CR | 25 | 19 | ||

| CR/no CR | 13 | 8 | ||

| No CR/CR | 15 | .096 | 15 | .001 |

| No prior CR | 32 | 19 | ||

| Duration of first CR, mo | ||||

| 0 | 25 | 19 | ||

| 1-11 | 12 | 6 | ||

| 12-35 | 19 | .016 | 14 | <.001 |

| ≥36 | 44 | 44 | ||

| Karyotype | ||||

| Diploid | 18 | 10 | ||

| Philadelphia-positive | 20 | .67 | 9 | .42 |

| Other | 17 | 16 | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | ||||

| <10 | 11 | <.001 | 8 | <.001 |

| ≥10 | 28 | 20 | ||

| WBC, × 109/L | ||||

| <5 | 20 | 14 | ||

| 5-20 | 23 | .15 | 19 | .002 |

| >20 | 9 | 6 | ||

| Percentage bone marrow blasts | ||||

| <20 | 32 | 29 | ||

| 20-50 | 31 | .013 | 22 | .001 |

| >50 | 14 | 12 | ||

| Percentage peripheral blasts | ||||

| 0 | 31 | 20 | ||

| 1-10 | 19 | .008 | 14 | .013 |

| >10 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Platelets, × 109 | ||||

| <25 | 7 | 7 | ||

| 25-50 | 10 | <.001 | 10 | <.001 |

| >50 | 28 | 20 | ||

| Albumin, g/L | ||||

| <3 | 11 | 2 | ||

| ≥3 | 21 | <.001 | 17 | <.001 |

| Immunophenotype | ||||

| B-cell origin | 19 | 14 | ||

| T-cell origin | 20 | .91 | 12 | .72 |

| Unknown/not done | 17 | 14 | ||

| Year of study | ||||

| 1980-1991 | 24 | .02 | 14 | .96 |

| 1992-2007 | 14 | 14 | ||

| Salvage 2 | ||||

| VAD/hyper-CVAD cytarabine combinations, allogeneic transplantation |

31 | <.001 | 19 | .004 |

| Other | 7 | 10 |

CR indicates complete response; WBC, white blood cell count; VAD, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; hyper-CVAD, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.

Prognostic factors that were associated with CR rates were duration of first remission, hemoglobin level, percent bone marrow blasts and peripheral blasts, platelet counts, and albumin levels. In multivariate analysis, the duration of first CR (cutoff, 36 months) and platelet counts (cutoff, 50 × 109/L) remained independent prognostic factors for response (P < .01). Response according to the presence of none, 1, or 2 adverse factors is shown in Table 5. Patients with a first CR that lasted for <36 months and a platelet count <50 × 109/L had an expected CR rate of only 7%.

TABLE 5.

Response and Survival According to the Number of Adverse Factors Present

| No. of Adverse Factors | No. of Patients | No. of CRs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 6 (60) |

| 1 | 127 | 34 (27) |

| 2 | 110 | 8 (7) |

| No. of Adverse Factors | No. of Patients | 1-Year Survival, % |

|

| ||

| 0-1 | 55 | 33 |

| 2 | 89 | 14 |

| 3 | 74 | 8 |

| 4 | 29 | 0 |

CR indicates complete response.

The median duration of disease remission was 7 months (range, 1–3 months) (Fig. 1). The median survival was 3 months (range, 0–230 months) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Remission duration and survival. CR indicates complete response.

Prognostic factors that were associated significantly with survival were duration of first CR, hemoglobin levels, white blood cell counts, percent bone marrow and peripheral blood blasts, platelet counts, and albumin levels. Multivariate analysis identified the following as independent prognostic factors for survival: duration of first CR (cutoff, 36 months; P = .001); percent bone marrow blasts (cutoff, 50%; P = .005); platelet count (cutoff, 50 × 109/L; P = .017), and albumin level (cutoff, 3 g/L; P = .0002). Survival in the presence of 0/1, 2, 3, or 4 adverse factors is shown in Table 5 and in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Survival by number of adverse factors derived from the multivariate analysis.

Only 22 patients (8%) were able to undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantation for active disease: 9 patients (41%) achieved a CR, and the 1-year survival rate was 18%, which was not different from the outcome of other patients (P = .096). Of the 53 patients who achieved a CR, 7 underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation in third CR, and all 7 patients developed recurrent disease after a median of 4.5 months (range, 2–19.5 months).

Effect of Prior Therapy and of Second Salvage Therapy on Prognosis

The previous model included pretreatment patient and disease characteristics. However, it can be argued that the efficacy of frontline therapy may have a significant impact on second salvage outcome. In particular, since 1992, we have used the hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone. (hyper-CVAD) regimen as frontline ALL therapy3; this regimen is more effective and more intensive than previous frontline regimens. Thus, it is possible that patients who underwent salvage therapy since then may have had more resistant disease. Similarly, second salvage regimens may have different efficacy (Table 3) as well as significant interactions with pretreatment characteristics. To address these 2 issues, we repeated the multivariate analyses and included 2 additional variables: 1) year of therapy (1980-1991 vs 1992-2007); and 2) second salvage therapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone;[VAD]/hyper-CVAD, cytarabine combinations, and allogeneic stem cell transplantation vs others). Second salvage therapies were investigated first individually and then were grouped into 2 categories based on the multivariate analysis results. The multivariate analysis for CR still selected the 2 previous variables (duration of first CR, P = .0037; thrombocytopenia, P = .0002) but also selected the ‘effective regimens’ (VAD/hyper-CVAD, cytarabine combinations, allogeneic stem cell transplantation) as independently prognostic (P = .000002).

Similarly, the multivariate survival analysis selected the same factors (duration of first CR, P = .006; percent bone marrow blasts, P = .005; platelet counts, P = .002; albumin levels, P = .00006); and also added second salvage therapy (P = .00004) as independent prognostic factors. This suggests that, although previously used second salvage therapies had different efficacy (VAD-hyper-CVAD, cytarabine combinations, and allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which was more effective), the prognostic models still can be used to evaluate the effect of newer second salvage regimens compared with average expectations based on pretreatment characteristics.

Achievement of Complete Response and Prognosis

To assess the benefit of achieving CR, we conducted a repeat multivariate analysis using a 6-week landmark that excluded patients who died within 6 weeks. The multivariate analysis included 190 patients and selected the following as variables that were associated independently with survival: duration of first CR (P = .004), percent bone marrow blasts (P = .001), and albumin levels (P = 0.018). Adding response (CR vs no CR) to the multivariate analysis revealed that CR added significantly to the survival benefit (P = .0001; hazard ratio, 0.51).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of 288 patients with adult ALL undergoing therapy in second salvage, the CR rate was 18%, and the median response duration was 7 months. For patients with a first CR duration <36 months and a pretreatment platelet count <50 × 109/L, the CR rate was only 7%. Survival was poor (median survival, 3 months), and only 14% of patients were alive at 12 months. A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors associated with survival selected a short duration of first CR, increased bone marrow blasts, thrombocytopenia, and hypoalbuminemia as independent, adverse factors. Achievement of CR improved survival significantly (P ≤ .0001; hazards ratio, 0.51).

The current analysis emphasizes the dire prognosis of patients with ALL once they have failed frontline and first salvage therapy and the need to explore new therapeutic modalities that may produce a CR in this setting. In reviewing the adult ALL literature, although several studies have reported their experience in first salvage,9–13 only rare studies have detailed the outcome of adult ALL in second salvage. Similarly, only clofarabine has been approved for pediatric ALL in second salvage. Nelarabine recently was approved by the FDA for T-cell ALL salvage.18,19 The CR rates with nelarabine were 20% to 40%, and the median response duration was 4 to 6 months.18,19 In Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL, the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib) have produced complete hematologic response rates of 5% to 30% and cytogenetic response rates of 5% to 45%.20–22 However, response durations were brief, and the median survival ranged from 4 months to 9 months.20–22

The multivariate analysis that included second salvage therapies identified ‘more effective’ second salvage regimens (VAD/hyper-CVAD, cytarabine regimens, allogeneic transplantation) but also highlighted the consistent nature of the pretreatment prognostic factors and the potential validity of the proposed models for assessing the possible benefit of future second salvage regimens.

In summary, our experience with second salvage in adult patients with ALL confirms the poor prognosis of this condition, emphasizes the urgent need to develop novel strategies in this setting, and establishes baseline expectations against which new approaches can be compared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pui C-H, Evans WE. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:605–615. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nachman JB, Sather HN, Sensel MG, et al. Augmented post-induction therapy for children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a slow response to initial therapy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1663–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, O’Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up results of hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (hyper-CVAD), a dose-intensive regimen, in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2004;101:2788–2801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faderl S, Jeha S, Kantarjian HM. The biology and therapy of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2003;98:1337–1354. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson RA. Recent clinical trials in acute lymphocytic leukemia by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:1367–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durrant IJ, Richards SM, Prentice HG, Goldstone AH. The Medical Research Council trials in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:1327–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gokbuget N, Hoelzer D, Arnold R, et al. Treatment of Adult ALL according to protocols of the German Multicenter Study Group for Adult ALL (GMALL) Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:1307–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiebaut A, Vernant JP, Degos L, et al. Adult acute lymphocytic leukemia study testing chemotherapy and autologous and allogeneic transplantation. A follow-up report of the French protocol LALA 87. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:1353–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom Adult ALL Working Party; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109:944–950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavernier E, Boiron JM, Huguet F, et al. GET-LALA Group; Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Res. SAKK; Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group Outcome of treatment after first relapse in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia initially treated by the LALA-94 trial. Leukemia. 2007;21:1907–1914. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Manero G, Thomas DA. Salvage therapy for refractory or relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:163–205. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas DA, Kantarjian H, Smith TL, et al. Primary refractory and relapsed adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: characteristics, treatment results, and prognosis with salvage therapy. Cancer. 1999;86:1216–1230. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1216::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George SL, Ochs JJ, Mauer AM, Simone JV. The importance of an isolated central nervous system relapse in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:776–781. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.6.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeha S, Kantarjian H. Clofarabine for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Exp Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:113–118. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeha S, Gandhi V, Chan KW, et al. Clofarabine, a novel nucleoside analog, is active in pediatric patients with advanced leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:784–789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox DR, Snell EJ. The analysis of binary data. Chapman & Hall; London, UK: 1970. pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtzberg J, Ernst TJ, Keating MJ, et al. Phase I study of 506U78 administered on a consecutive 5-day schedule in children and adults with refractory hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3396–3403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeAngelo DJ, Yu D, Johnson JL, et al. Nelarabine induces complete remissions in adults with relapsed or refractory T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma: Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 19801. Blood. 2007;109:5136–5142. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottmann OG, Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, et al. A phase 2 study of imatinib in patients with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoid leukemias. Blood. 2002;100:1965–1971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ottmann O, Dombret H, Martinelli G, et al. Dasatinib induces rapid hematologic and cytogenetic responses in adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with resistance or intolerance to imatinib: interim results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2007;110:2309–2315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottmann O, Kantarjian H, Larson R, et al. A Phase II study of nilotinib, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor administered to imatinib resistant or intolerant patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in blast crisis (BC) or relapsed/refractory Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) Blood. 2006;108:1862. [Google Scholar]