Abstract

Aim

To assess the natural history and impact of the secondary bone disease observed in patients with Mucolipidosis II and III.

Methods

Affected children and adults were ascertained from clinical genetics units around Australia and New Zealand and the National Lysosomal Diseases Research Unit in Adelaide. The study encompassed all patients ascertained between 1975 and 2005. Data focussing on biochemical parameters at diagnosis, and longitudinal radiographic findings were sought for each patient. Where feasible, patients underwent clinical review and examination. Examinations included skeletal survey, bone densitometry, and measurement of serum and urine markers of bone metabolism. Functional assessment was performed using the Pediatric Evaluation and Disability Inventory (PEDI).

Results

25 patients with ML II and III were ascertained over a 30-year period. Serum calcium (median 2.35 mmol/L range 2.16–2.64) and phosphate (median 1.51 mmol/L range 1.17–1.72) were normal but five patients had mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase. Serum osteocalcin and urine deoxypyridinoline/creatinine were elevated. Two radiological patterns were observed (i) transient neonatal hyperparathyroidism in infants with ML II and (ii) progressive osteodystrophy in patients with ML II/III and ML III. Molecular Genetic analysis of mutations in the αβsubunit of the UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:lysosomal enzyme N-acetylglucosaminyl-1-phosphotransferase gene in 9 subjects correlated with the phenotypic severity.

Conclusion

ML is characterised by a progressive bone and mineral disorder which we describe as the Osteodystrophy of Mucolipidosis. The clinical and radiographic features of this osteodystrophy are consistent with a syndrome of “Pseudohyperparathyroidism”. Much of the progressive skeletal and joint pathology is attributable to this bone disorder.

Keywords: Mucolipidosis, hyperparathyroidism, pseudohyperparathyroidism, osteoporosis

Introduction

Mucolipidosis II and III (I-cell disease and pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy, respectively) are rare genetically related inherited metabolic disorders of lysosomal metabolism with a combined frequency of 1:422,0001. These are characterised by disordered processing of multiple lysosomal degradative enzymes caused by the deficiency or abnormal function of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:lysosomal enzyme N-acetylglucosaminyl-1-phosphotransferase (phosphotransferase)2. The underlying defects result in deficient post-translational modification of numerous enzymes, which depend on mannose phosphorylation for uptake and localisation by cells where substrate degradation occurs3. This in turn results in global deficiencies of lysosomal degradative enzymes with concomitant intracellular accumulation of both partly degraded glycosaminoglycans and sphingolipids.

ML II has symptoms and signs similar to those encountered in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses and to a lesser extent gangliosidoses. It is characterised by coarse facial features, short stature, hyperplastic gums, organomegaly, and retarded psychomotor development4, 5. ML III is a milder disorder with attenuated characteristics and survival to adult life6, 7. Intermediate forms of ML II and III have been previously described8, 9. The presence of clinical heterogeneity is explained by the presence of at least three complementation groups26–28. This is consistent with the finding that the phosphotransferase is a complex enzyme consisting of three subunits that are product of two genes30, 31. Most affected individuals with ML II and ML III have mutations in the alpha/beta subunit32.

Previous radiographic studies of mucolipidosis types II and III have focussed mainly on those bone changes collectively called “dysostosis multiplex”, although a few authors have drawn attention to bone changes in infants with ML II which are similar to infantile hyperparathyroidism and rickets. In this study, we describe a progressive bone and mineral disorder, its biochemical characteristics and skeletal radiographic findings in patients with Mucolipidosis II and III. In addition, we assess the impact of the secondary bone disease observed in patients on spine and hip morbidity, and assess the frequency and morbidity arising from non-osseous complications of mucolipidosis.

Materials and Methods

Patients were ascertained through Clinical Genetics Units around Australia and New Zealand, the Kazimierz Kozlowski Skeletal Dysplasia Library and the Connective Tissue Dysplasia clinic at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. Patients registered with those units between 1975 and 2005 were included. All diagnoses were enzymatically confirmed by the National Lysosomal Diseases Research Unit in Adelaide. Ethics committee approval for the study was obtained from the ethics committee of the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. Information was sought from collaborating clinical geneticists on diagnosis, radiographic findings, and previous biochemical investigation of mineral metabolism in the patients managed by them. Where feasible, living patients underwent clinical review and investigations. Investigations included skeletal survey, bone densitometry, measurement of bone markers (serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, parathyroid hormone related protein, serum osteocalcin, and urine deoxypyridinoline crosslinks). Functional assessment was performed using the Pediatric Evaluation and Disability Inventory (PEDI)10. This standardised scaling tool measures the domains of life skills, mobility, and social function. DNA molecular genetic diagnosis was undertaken in a subset of patients10.

Results

Clinical Data

A total of 25 affected (ML II = 15; ML III = 5; Intermediate MLII/ML III = 5) from 16 families were ascertained. The female to male ratio was 1.8 (16F:9M).

Morbidity

Ten surviving patients were available for clinical review. Five patients had ML type II/III, 1 had ML type II and 4 had ML type III. All of the 8 subjects in whom height data were available were very short, height SDS = −8.25±3.4. Chronic otitis media was present in 7/10 patients. Cardiovascular complications such as mild dilatation of the heart and valvular thickening and incompetence were present in 9/10. Sleep disordered breathing requiring continuous or bi-level positive airway pressures (CPAP or BiPAP) at the level of 8 to 10 cm water was recorded in 6/10. Four young adults developed upper limb paraesthesia with MRI evidence of thickening of the extradural tissues at the level of C1-2. One patient required cervical fusion for C1-C2 instability at 8 years of age and a 20 year old progressed to inoperable occipitocervical dislocation. Five patients had chronic constipation requiring almost daily laxatives and occasional bowel evacuation.

Nine patients had psychomotor retardation. One patient with ML III who was evaluated at 40 years of age had normal intelligence. All patients had progressive joint stiffness. The patient with ML type II had significant joint stiffness at 5 years of age such that she could only sit and stand with support. She moved around with her small wheelchair for less than 90 minutes a day. She cried when being held and picked up, implying that she had significant pain, probably bone in origin. The other 9 patients suffered from significant back and joint pains, mainly in the hips by age 3 years. They became confined in their wheelchair by the time they reach 10 years of age. One patient had bilateral hip replacements at 36 years.

Biochemical findings

Eight patients underwent biochemical evaluation, Table 3. All had normal serum calcium (median 2.35 mmol/L range 2.16–2.64), phosphate (median 1.51 mmol/L range 1.17–1.72), and parathyroid hormone (median 2.9 pmol/L range 1.8–5.0). Parathyroid receptor protein concentrations were available in six patients and all were within normal levels (median <0.6 range <0.6–1.4). Alkaline phosphatase was elevated in only 1 out of the 8 (median 155 u/L range 102–495). Seven had osteocalcin levels and were elevated in 6 (median 3.8 nmol/L range 0.8–7.5). Levels of urine deoxypyridinoline/creatinine were elevated in all patients (median 26.7 nM/mM range 14.2–45.5).

Table 3.

Baseline Biochemical Findings (n=8)

| Biochemistry and markers | Median | Range | Normal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | 2.35 | 2.16–2.64 | 2.10–2.65 mmol/L |

| Phosphorus | 1.51 | 1.17–1.72 | 1.00–1.80 mmol/L |

| ALP | 155 | 102–495 | 80–355 U/L |

| Osteocalcin | 3.8 | 0.8–7.5 | 0.5–2.3 nmol/L |

| PTH | 2.9 | 1.8–5.0 | 1.0–7.0 pmol/L |

| PTHrP | <0.6 | <0.6–1.4 | <1.3 pmol/L |

| Deoxypyridinoline/Creatinine | 26.7 | 14.2–45.5 | Variable ranges |

Lysosomal Enzyme Biochemistry

Diagnosis of all patients, with one exception, was confirmed enzymatically by measurement of markedly elevated plasma lysosomal hydrolases and the demonstration of markedly deficient white cell enzymes in cultured skin fibroblast. In one patient, diagnosis was accomplished by review of radiographs after her siblings had been confirmed to have mucolipidosis on enzymology testing. This particular subject was stillborn and was also found to have 45, X on chromosome analysis.

Molecular DNA Analysis

Mutations in αβsubunit of the UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:lysosomal enzyme N-acetylglucosaminyl-1-phosphotransferase gene were detected in 9 patients and are summarized in table 2.

Table 2.

Mutations in the “Clinical” cohort of mucolipidosis (n = 9)

Mutations in the AB subunit in a subgroup of patients

| Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mucolipidosis II (1) | c.2591insG | c.3503ΔTC |

| Mucolipidosis II/III (5) | c.10A>C | c.1399ΔG |

| Mucolipidosis III (1) | c.1399ΔG | c.3335+6T>G |

| Mucolipidosis III (2) | c.3565C>T | IVS17+6T>G |

Radiographic findings

Skeletal radiographs showed distinctive patterns in patients at different ages. These were grouped as evidence of:

neonatal hyperparathyroidism

osteodystrophy (similar to chronic osteitis fibrosis cystica)

dysostosis multiplex

The radiographic findings of neonatal hyperparathyroidism were seen in all babies with ML type II. These changes included generalised bone demineralisation, subperiosteal bone resorption around the shafts of the long bones or periosteal cloaking, and fractures of long bones and ribs (Figure 1). In addition, there were features of rickets with metaphyseal cupping or fraying. Three patients had punctate calcifications in the region of the coccyx, pubis and tarsals at birth.

Fig 1.

Radiograph of pelvis and femurs in a neonate with Mucolipidosis Type II – showing features of neonatal hyperparathyroidism including periosteal cloaking and destructive bone lesions,

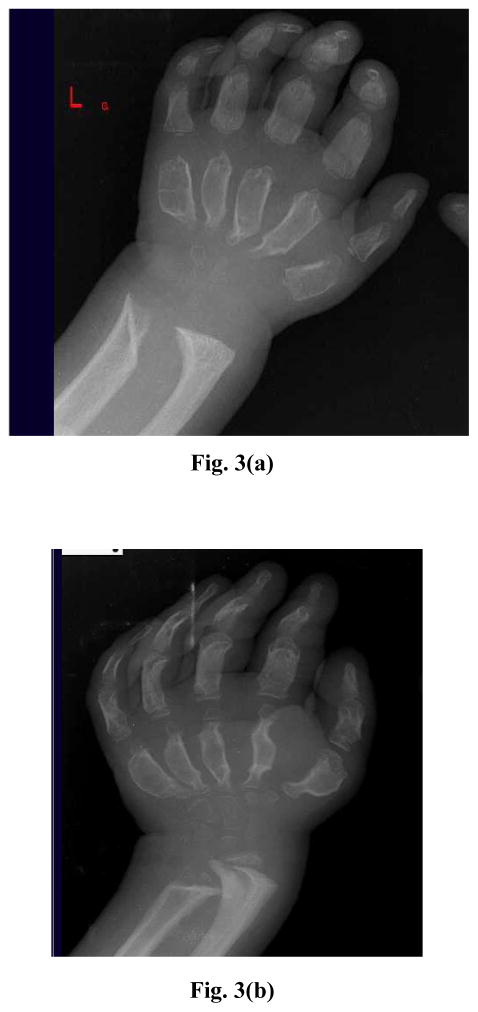

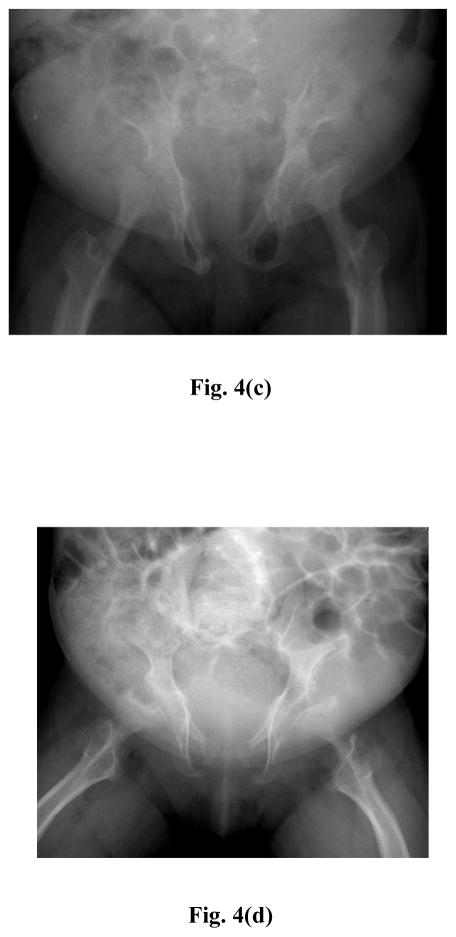

In subjects over 4 months, radiographs show features of an osteodystrophy with features reminiscent of “osteitis fibrosa cystica”. There were marked progressive changes in bone texture and density with areas of cystic lucency. Erosive changes especially in the hands and hips were progressive over time (Fig 3 and 4). The proximal phalanges became broad and under modelled. The proximal metacarpals showed a mixture of features of osteodystrophy and dysostosis multiplex becoming extremely eroded and narrowed to a point. The carpal bones became extremely osteopenic and hypoplastic, consistent with severe carpal osteolysis. Similarly there was severe osteolysis of the femoral heads and femoral necks. There was also over modelling of the long bones and bowing of the proximal end of the humerus and femur leading to coxa valga or “shepherd’s crook deformity” (Figure 2). The lower third of the ilia became progressively hypoplastic and resorbed (Figure 4). In addition, there was progressive osteopenia of the spine. The spine showed thoracolumbar kyphosis, beaking of the vertebrae, and subluxation typical of lysosomal storage disorders with skeletal involvement.

Fig. 3.

Radiograph of hands and wrists in four affected with ML II/III aged (a) 4 yrs., (b) 16 yrs., (c) 18 yrs., (d) 19 yrs. showing progressive osteolysis of carpal centres, proximal metacarpals and distal forearm bones.

Fig. 4.

Radiograph of pelvis and proximal femurs in four affected with ML II/III aged (a) 4 yrs., (b) 16 yrs., (c) 18 yrs., (d) 19 yrs. showing progressive dysplasia/resorbtion of the low third of the ilia femoral heads and femoral necks.

Fig 2.

Radiograph of pelvis and femurs in a 3 year old with Mucolipidosis type II showing over-modelling of the proximal end of the femur leading to coxa valga or “shepherd’s crook deformity”. The lower third of the ilia have become progressively hypoplastic and resorbed.

In all patients surviving the first year of life, skeletal radiographs showed a mixture of osteodystrophic bone changes and atypical changes of dysostosis multiplex. These included proximal pointing of metacarpals in the wrist, dysplastic changes in the lower third of the ilia, marked broadening of the ribs becoming oar-shaped, and beaking of the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

Bone Densitometry

The results are reported in a supplementary paper detailing the baseline parameters and effect of treatment with Cyclic Intravenous Pamidronate.

Functional assessment (PEDI)

Except for Assistance to Caregiver Skills in the Social Function Domain, the five subjects who were assessed had scores below the level of their age normative functional capability and performance in all domains. Almost all of the scaled scores in all subjects were below 70. However the subjects understood requests and instructions and they were able to provide information about their own activities and needs indicating that comprehension was much higher than might be concluded from their severe physical disability.

Discussion

Many lysosomal storage disorders, particularly the mucopolysaccharidoses are characterised by “dysostosis multiplex”. The combination of radiographic features includes “J” shaped sella turcica, oar shaped ribs, anterior inferior beaking of lower thoracic to upper lumbar vertebral bodies, flared iliac wings, constricted iliac bodies, dysplastic femoral heads, “bullet-shaped” proximal phalanges and central pointing of proximal metacarpals12. In this study, dysostosis multiplex developed with age but was not the characteristic feature of newborns.

In addition to dysostosis multiplex, the skeleton in Mucolipidosis types II and III is characterised by an osteodystrophy. In ML II, the osteodystrophy has clinical and radiographic features of congenital hyperparathyroidism. In some neonatal subjects, chemical hyperparathyroidism was also demonstrated.

Features of congenital hyperparathyroidism have been reported in Mucolipidosis type II as early as 19 weeks of gestation13. Osteoporosis, fractures, periosteal new bone formation (“cloaking”) and cupped epiphyses have been described in neonates14–21. Histologic examination has confirmed the presence of hyperparathyroidism22–24. Pazzaglia et al23–25 described spontaneous evolution of hyperparathyroidism to dysostosis multiplex in three patients, and they noted resolution of high bone turnover and defective calcification in the older child. In this study we have observed that in ML II/III and ML III there are progressive radiographic features which overlap with juvenile hyperparathyroidism or chronic hyperparathyroidism or “osteitis fibrosa cystica”.

In this study, we have confirmed that ML II cell disease is not associated with a disturbance of serum levels of calcium and phosphorus. In our one patient with ML II serum parathyroid hormone was normal but may have been elevated previously as the diagnosis was not made until 4 months of age. Similarly bone and mineral investigations have been delayed in other patients in this series. However all subjects had persisting high bone turnover as measured by deoxypyridinoline/creatinine ratio and progressive osteopenia. Since features of this osteodystrophy are not present in the other lysosomal storage disorders except for Galactosialidosis, we hypothesize that the osteodystrophy is related to the underlying biochemical disorder.

The possible pathogenesis for the osteodystrophy needs to explain the observation of transient hyperparathyroidism of the newborn and the progressive “osteitis fibrosa cystica” which develops from 3–6 months of age. Transient neonatal hyperparathyroidism is also reported where a fetus has inherited a mutation in the calcium-ion sensing receptor36 mutation from the father, and has an unaffected mother. The clinical disorder in the father is manifest as familial hypercalcaemic hypocalciuria. The fetal parathyroid in this situation has a higher “set point” than normal for serum calcium and registers that the mother’s serum calcium is too low35. The fetal parathyroid responds with excessive secretion of parathormone at the expense of the skeletal integrity with resultant demineralisation, rickets, resorption, and cystic changes with periosteal cloaking. Characteristically, the secondary hyperparathyroidism resolves spontaneously by 3–4 months of age. In ML a possible mechanism for the biochemical/radiologic changes might be that one of the components of signal transduction from the PTH receptor requires mannose-6-phosphate targeting and this induces the PTH receptor signalling.

Following birth we have confirmed that chemical hyperparathyroidism in ML II resolves but a progressive osteodystrophy appears to develop further and progress. We also confirmed that circulating levels of parathyroid related protein were normal. Postnatally, the radiographic features could be consistent with an increased sensitivity of skeletal tissue to normal circulating levels of parathormone.

In a previous report of the treatment of the osteodystrophy with cyclic intravenous pamidronate in two teenagers with ML III, attention was drawn to the bone histomorphometric finding of increased osteoclastic activity25. Our biochemical findings support high bone turnover with elevated osteocalcin and deoxypyridinoline. One possibility is that there is defective targeting of lysosomal enzymes to the osteoclast with abnormal biofeedback and induction of PTH receptor transduction, with focal areas of increased resorbtion. Another possibility is that mannose-6-phosphate targeting is important for other proteins involved in signal transduction of PTH effects on bone formation and remodelling. The radiographic findings show a remarkable similarity to Osteitis Fibrosa Cystica. We hypothesize that the pathology is best explained as “Pseudohyperparathyroidism” i.e. tissue sensitivity to circulating PTH.

There is a need for further studies regarding the pathophysiology of the osteodystrophy in ML II and ML III. Answers to these questions will be obtained from the early and systematic study of the osteodystrophy of subjects with Mucolipidoses who should be investigated from birth or time of diagnosis. Furthermore study of the cat model33, 34 of Mucolipidosis might give additional answers to this perplexing problem.

The osteodystrophy of the Mucolipidoses contributes significantly to the skeletal and joint symptoms and progressive and destructive bone disease which place a significant additional burden of weakness, pain and disability over that encountered in mucopolysaccharide storage disorders. A better understanding of the pathogenesis is important to improve the quality of life of those affected. Treatment with Cyclic Intravenous Pamidronate is a promising adjunctive therapy which is presently being evaluated for those affected with the Mucolipidoses25.

Table 1.

Clinical Features at Diagnosis

| Clinical Features at Diagnosis | ML II N=15 |

ML II/III N=5 |

ML III N=5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse facial features | 14 | 5 | 4 |

| Corneal clouding | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Chest deformity | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Umbilical hernia | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Inguinal hernia | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Hepatomegaly | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Splenomegaly | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Joint contractures | 8 | 5 | 2 |

| Congenital hip dislocation | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Evidence of hyperparathyroidism | 15 | 5 | NK |

| Progressive Osteodystrophy | 5 | 5 |

NK = not known

Acknowledgments

Dr David-Vizcarra was the ConnecTeD and Jameson Read Fellow during this research. The authors acknowledge the helpful discussion and insights with Dr Sheila Unger, Clinical Geneticist, into the potential mechanisms particularly the mechanisms resulting in neonatal hyperparathyroidism.

We are indebted to the other clinical geneticists who contributed information about patients reviewed in the study. Drs Martin Delatycki, David Amor from Genetic Health Victoria,

We also express our gratitude to Mrs Jenny Noble, secretary Lysosomal Diseases New Zealand, who provided much encouragement and support.

References

- 1.Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. JAMA. 1999;281:249–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornfeld S, Sly W. I-Cell Disease and Pseudo-Hurler Polydystrophy: Disorders of Lysosomal Enzyme Phosphorylation and Localization. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. p3469–82. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sly W, Sundaram V. The I-Cell model: the molecular basis for abnormal lysosomal enzyme transport in mucolipidosis II and mucolipidosis III. In: Lloyd KK, Scriver CR, editors. Genetic and Metabolic Disease in Pediatrics. London: Butterworths; 1985. pp. p91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leroy J, DeMars R, Opitz J. I-Cell Disease. Birth Defects: Original Article Series. 1969;5:174–187. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada S, Owada M, Sakiyama T, Yutaka T, Ogawa M. I-cell disease: clinical studies of 21 Japanese cases. Clin Genet. 1985;28:207–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maroteaux P, Lamy M. La pseudopolydystrophie de Hurler. Presse Med. 1966;74:2889–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly TE, Thomas GH, Taylor HA, Jr, McKusick VA, Sly WS, Glaser JH, Robinow M, Luzzatti L, Espiritu C, Feingold M, Bull MJ, Ashenhurst EM, Ives EJ. Mucolipidosis III (pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy): Clinical and laboratory studies in a series of 12 patients. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975;137:156–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poenaru L, Castelnau L, Tome F, Boue J, Maroteaux P. A variant of mucolipidosis. II. Clinical, biochemical and pathological investigations. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:321–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00442708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozlowski K, Lipson A, Carey W. Mild I-cell disease, or severe pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy in three siblings: further evidence for intermediate forms of mucolipidosis II and III. Radiological features. Radiol Med (Torino) 1991;82:847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haley SM, Coster WJ, Ludlow LH, Haltiwanger JT, Andrellow PJ. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI), Version 1.0: Development, Standardization, and Administration Manual. Boston, MA: New England Medical Center Hospital Inc, and PEDI Research Group; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cathey S. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spranger J. Bone Dysplasia “Families”. Pathology and Immunopathology Research. 1198;7:76–80. doi: 10.1159/000157098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babcock DS, Bove KE, Hug G, Dignan PS, Soukup S, Warren NS. Fetal mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease): radiologic and pathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 1986;16:32–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02387502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leroy JG, Spranger JW, Feingold MD, Opitz JM. I-cell disease: A clinical picture. J Pediatr. 1971;79:360–365. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maroteaux P, Hors-Cayla MC, Pont J. Type II mucolipidosis. Presse Med. 1970;78:179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patriquin HB, Kaplan P, Kind HP, Giedion A. Neonatal mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease): clinical and radiologic features in three cases. Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:37–43. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cipolloni C, Boldrini A, Donti E, Maiorana A, Coppa GV. Neonatal mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease): clinical, radiological and biochemical studies in a case. Helv Paediatr Acta. 1980;35:85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whelan DT, Chang PL, Cockshott PW. Mucolipidosis II. The clinical, radiological and biochemical features in three cases. Clin Genet. 1983;24:90–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1983.tb02218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taber P, Gyepes M, Philippart M, Ling S. Roentgenographic Manifestations of Leroy’s I-Cell Disease. Am J Roent Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;118:213–221. doi: 10.2214/ajr.118.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sillence DO. Bone Dysplasia. Genetic and Ultrastructural Aspects with Special reference to Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Microfilms USA; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazzaglia UE, Beluffi G, Bianchi E, Castello A, Cochi A, Marchi A. Study of the bone pathology in early mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease) Eur J Pediatr. 1989;148:553–537. doi: 10.1007/BF00441557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazzaglia UE, Beluffi G, Campbell JB, Bianchi E, Colavita N, Diard F, Gugliantini P, Hirche U, Kozlowski K, Marchi A, Nayanar V, Pagani G. Mucolipidosis II: Correlation between radiological features and histopathology of the bones. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19:406–413. doi: 10.1007/BF02387638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pazzaglia UE, Beluffi G, Castello A, Cochi A, Zatti G. Bone Changes of Mucolipidosis II at Different Ages. Clinical Orthopaedics. 1992;276:283–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pazzaglia UE, Beluffi G, Danesino C, Frediani PV, Pagani G, Zatti G. Neonatal mucolipidosis 2. The spontaneous evolution of early bone lesions and the effect of vitamin D treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;20:80–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02010640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson C, Baker N, Noble J, King A, David G, Sillence D, Hofman P, Cundy T. The osteodystrophy of mucolipidosis type III and the effects of intravenous pamidronate treatment. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:681–693. doi: 10.1023/a:1022935115323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honey NK, Mueller OT, Little LE, Miller AL, Shows TB. Mucolipidosis II is genetically heterogeneous. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7420–724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shows TB, Mueller OT, Honey NK, Wright CE, Miller AL. Genetic heterogeneity of I-cell disease is demonstrated by complementation of lysosomal enzyme processing mutants. Am J Med Genet. 1982;12:343–353. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320120312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller OT, Honey NK, Little LE, Miller AL, Shows TB. Mucolipidosis II and III: The genetic relationship between two disorders of lysosomal enzyme biosynthesis. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1016–1023. doi: 10.1172/JCI111025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little LE, Mueller OT, Honey NK, Shows TB, Miller AL. Heterogeneity of N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphotransferase within mucolipidosis III. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao M, Booth JL, Elmendorf BJ, Canfield WM. Bovine UDP-N-acetylglucosamine: Lysosomal-enzyme N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase: I. Purification and subunit structure. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:314446–314451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raas-Rothschild A, Cormier-Daire V, Bao M, Genin E, Salomon R, Brewer K, Zeigler M, Mandel H, Toth S, Roe B, Munnich A, Canfield WM. Molecular basis of variant pseudo-hurler polydystrophy (mucolipidosis IIIC) J Clin Invest. 2000;105:673–681. doi: 10.1172/JCI5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiede S, Storch S, Lübke T, Henrissat B, Bargal R, Raas-Rothschild A, Braulke T. Mucolipidosis II is caused by mutations in GNPTA encoding the α/β GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase. Nat med. 2005;11:1109–1112. doi: 10.1038/nm1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hubler M, Haskins ME, Arnold S, Kaser-Hotz B, Bosshard NU, Briner J, Spycher MA, Gitzelmann R, Sommerlade HJ, von Figura K. Mucolipidosis type II in a domestic shorthair cat. J Small Anim Pract. 1996;37:435–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1996.tb02444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosshard NU, Hubler M, Arnold S, Briner J, Spycher MA, Sommerlade HJ, von Figura K, Gitzelmann R. Spontaneous mucolipidosis in a cat: an animal model of human I-cell disease. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:1–13. doi: 10.1177/030098589603300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marx SJ, Lasker RD, Brown EM, Fitzpatrick LA, Sweezey NB, Goldbloom RB, Gillis DA, Cole DE. Secretory dysfunction in parathyroid cells from a neonate with severe primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:445–449. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-2-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown EM, Pollak M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Chou YH, Riccardi D, Hebert SC. Calcium-ion-sensing cell-surface receptors. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:234–240. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unger S, Paul DA, Nino MC, McKay PC, Miller S, Sochett E, Braverman N, Clarke JT, Cole DE, Superti-Furga A. Mucolipidosis II presenting as severe neonatal hyperparathyroidism. Euro J Pediatr. 2005;164:236–243. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]