Abstract

Purpose

To describe a novel surgical method for sutureless placement of amniotic membrane on the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva in the setting of ocular-involving acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Methods

Six days into an acute Stevens-Johnson episode, a 27-year-old male developed early symblepharon, despite aggressive lubrication and topical steroid therapy. He underwent symblepharon lysis and placement of an amniotic membrane wrapped around a symblepharon ring.

Results

The patient maintained 20/20 vision in each eye with no recurrent symblepharon formation except for the temporal canthus (which was not covered with amniotic membrane).

Conclusion

Amniotic-membrane-wrapped symblepharon rings provide a sutureless way to fixate amniotic membrane to the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva with very good anatomic and functional outcomes in an acute Stevens-Johnson patient. Future research could be directed towards development of a symblepharon ring able to better protect the far temporal conjunctiva.

Keywords: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, amniotic membrane, bulbar conjunctiva, palpebral conjunctiva, Lamotrigine

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and the more severe toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are Type 3 hypersensitivity reactions occurring most commonly from medications and rarely from infections.1 As a sequelae to conjunctival inflammation from SJS/TEN, mucin-producing goblet cells, lacrimal ducts, and meibomian glands may be damaged with an end result of symblephara formation and keratinization of the ocular surface.2 The resultant corneal stem cell deficiency and cicatrization of the ocular surface is notoriously difficult to treat. For visual rehabilitation at this stage, patients may require scleral contact lenses, or in severe cases, allogenic limbal stem cell transplants or keratoprosthesis.3–6 Even with appropriate management, these cases can end in irreversible and complete loss of vision.

To avoid poor outcomes, it has been demonstrated that patients treated in the hyperacute phase of their disease (<72 hours from presentation) who have conjunctival epithelial sloughing have much more positive visual outcomes than if treatment is delayed.7 Current therapies which have met with success are pulse systemic (controversial5) steroid therapy, topical steroid therapy,8 and full and anchored coverage of the ocular surface with amniotic membrane. It has been demonstrated that early treatment with amniotic membrane in moderate to severe ophthalmic cases of SJS/TEN dramatically reduces the complication rate from 34.8% to 4.3%.9

Originally, anchoring of the amniotic membrane required complex and time consuming suturing of multiple amnion pieces to the eyelid margin, the fornix, and the limbus that required bolsters and stitch removal on the patient’s eyelids and ocular surface.9 A modified technique sutures 3 amnion pieces together in series, suturing the leading and trailing edge to the superior and inferior lid margin, then fashions a custom symblepharon ring from a suture passed through intravenous tubing and places it into the fornix.10 Both of these techniques require significant physician time and are technically difficult to perform; a sutureless technique could address some of these constraints.

The Prokera ring (Bio-Tissue, Inc., Doral, FL) is a Food and Drug Administration-approved device that consists of an amniotic membrane circle clamped into a dual 15 or 16 mm symblepharon ring. The usage of Prokera rings has been particularly successful in mild cases, but more severe cases have only had moderate success. The limbus and corneal epithelial stem cells have been salvaged, but the conjunctival fornices and lid margins have failed to be recouped, resulting in entropion, fornix loss to symblephara, and eyelid margin keratinization.11,12 A combination of a Prokera ring, sub-conjunctival triamcinolone, and scleral conformer has had more success.13

Liang et al recently described a technique for sutureless application of amniotic membrane in burn patients involving placing an 8 cm × 8 cm amnion onto the ocular surface, followed by a custom-made symblepharon ring to the fornices. The entire ocular surface is covered by amnion, but this size of amnion is not commercially available. Each symblepharon ring must also be specifically made for each patient based upon a mold of the patient’s fornices. Lastly, there may be problems with having the amnion bunch and crumple upon insertion of the symblepharon ring.14

We present a novel surgical method for application of amniotic membrane to the conjunctival fornix by constructing a commercially available 22 mm symblepharon ring covered on either side with 3.5 mm × 3.5 mm amniotic membrane (stromal side outward) as a scaffold device, thereby allowing for near-complete coverage of the conjunctival fornix with a quicker and easier sutureless technique.

Case Report and Technique Description

A 27-year-old man with bipolar type two disorder was started on lamotrigine after having previously been treated with desvenlafaxine for one year. Two weeks after initiating lamotrigine, the patient began having a raised, maculopapular rash on his central chest. The next day the rash had spread to cover his upper torso with early vesicular lesions; he also began having eye redness and irritation, as well as difficulty swallowing. The patient presented to an urgent care center, and he was prescribed a course of oral amoxicillin for a presumed upper respiratory tract infection. By the following day the rash, eye complaints, and difficulty swallowing had progressed, and the patient also began having lip ulcerations. He was admitted to the hospital with suspicion of SJS/TEN, intubated emergently for laryngeal desquamation and edema, and monitored in the medical intensive care unit. The patient’s hospitalization was complicated by diffuse mucosal ulceration and desquamation in the oropharynx, larynx, and buccal mucosa. He also had genitourinary/urethral mucosal involvement requiring catheterization, as well as acute kidney injury secondary to low fluid balance. The patient’s skin ulcerations were primary concentrated on the chest, upper extremities, and back and were managed by the dermatology/burn service. The patient remained in the ICU for the first 7 days of admission.

On the evening of arrival, the patient was evaluated by the ophthalmology team and found to have bilateral bulbar and palpebral conjunctival epithelial defects involving approximately 25% of the conjunctival surfaces without symblephara. The patient was started on aggressive lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears, as well as prednisolone acetate, 1% drops every 2 hours in both eyes and tobramycin and dexamethasone ointment 4 times a day to both eyes. The patient remained in critical condition for the first 4 days after admission with tenuous fluid dynamics and worsening laryngeal edema preventing successful extubation. During this time period (post admission days 1 through 3), the patient was noted to have worsening conjunctival injection with an enlarging percentage of epithelial defects and development of small symblephara bilaterally in lateral fornices. Initially, the patient’s tenuous clinical status presented an obstacle to the patient undergoing any operative procedures. As the patient improved and was weaned off sedative medications, he refused immediate amniotic membrane transplantation, as he did not want to have his vision limited while he remained intubated.

In an effort to decrease the progression of ocular surface disease during this time period, the frequency of preservative-free artificial tears and prednisolone acetate, 1% drops were increased to every 1 hour, separated by 30 minutes. In addition, on post admission day 3, further anti-inflammatory medications of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and vitamin C 2 grams daily were initiated. However, over the next 2 days (post admission days 4 and 5), the patient’s conjunctiva continued to become increasingly inflamed with larger symblephara (now involving medial and lateral fornices, bilaterally) and further worsening of conjunctival injection and epithelial defects. The patient was successfully extubated in the evening of post admission day 5, at which point he agreed to an ocular procedure without re-intubation for the next day. To maintain forniceal architecture, treat inflamed conjunctiva, and prevent future symblephara formation, the patient was taken to the operating room for the implantation of a novel combination of amniotic membrane and symblepharon ring.

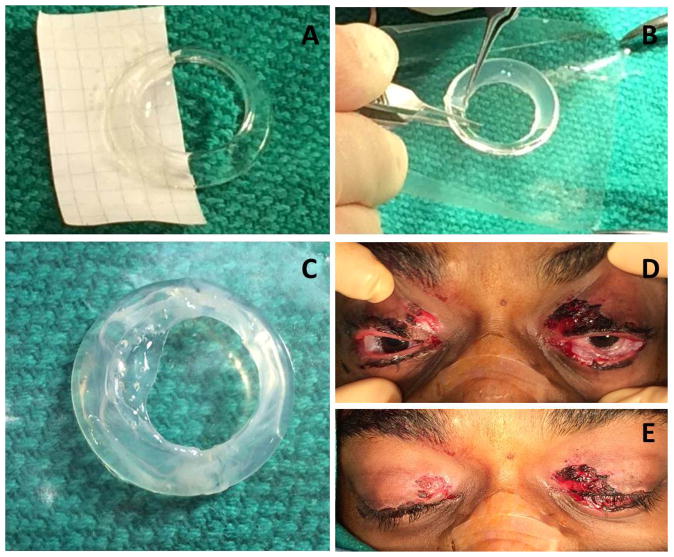

The patient was brought to the operating room, placed under monitored anesthesia care, and received bilateral retrobulbar blocks. He was then draped and prepped in the normal sterile fashion. Care was then taken to lyse the symblephara from all fornices, and pseudomembranes were debrided using sterile cotton swabs (Figure1). The symblepharon rings (FCI Ophthamic, Pembroke, MA) were prepared using a 3.5 × 3.5 cm fresh, frozen amniotic membrane sheet (Amniograft, Bio-Tissue, Miami, FL). First, the sheet was cut in half while still attached to the cardboard backing to form 2 3.5 cm × 1.75 cm sheets (Figure 2A). Each half sheet was then wrapped around one half of a 22 mm symblepharon ring by placing the equator of the ring on the 3.5 mm edge of the half sheet, stromal side still down on the cardboard, and basement membrane side upward touching the symblepharon ring. Forceps were then used to carefully lift the upper corners of the amniotic up and over the ring, thus creating an amniotic flap around half of the ring (Figure 2B). Fibrin glue was placed on the seam of the amniotic membrane sheet where they met at the ring’s inner perimeter to secure one end of the amniotic membrane to the other side of the membrane wrapped around the ring. Fixing the amniotic membrane to itself is vital, as the fibrin glue will not attach the amniotic membrane directly to the polymethylmethacrylate symblepharon ring. After waiting 2 minutes for the fibrin glue to settle, the same procedure was repeated on the other half of the symblepharon ring to create a ring that was covered with 360 degrees of stromal-outward facing amniotic membrane (Figure 2C). The ring was then placed in the patient’s fornices. The same procedure was performed with the additional amniotic membrane and another ring in the patient’s other eye. The patient was able to close his eyes completely after insertion of the rings (Figure 2D and 2E). Total operating time was 1 hour and 20 minutes.

Figure 1.

Preoperative membrane and symblepharon formation

Figure 2.

A) Placement of amniotic membrane along half of the symblepharon ring. B) Placement of the amniotic membrane around the symblepharon ring. C) Completion of amniotic membrane positioning along with fibrin glue placement. D) Final positioning of both rings in the conjunctival fornices. E) Closure of the eyelids over the amnion doughnut.

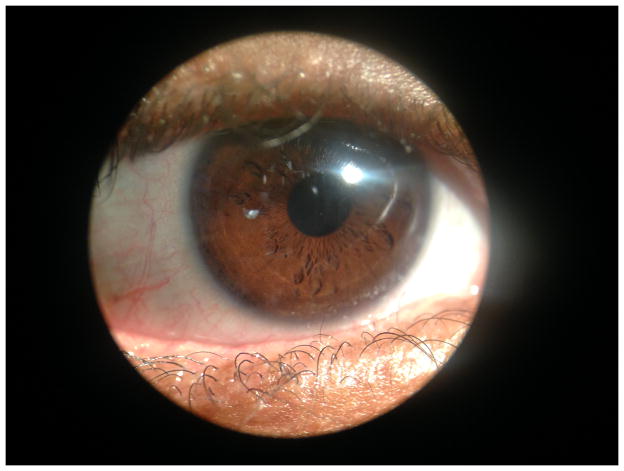

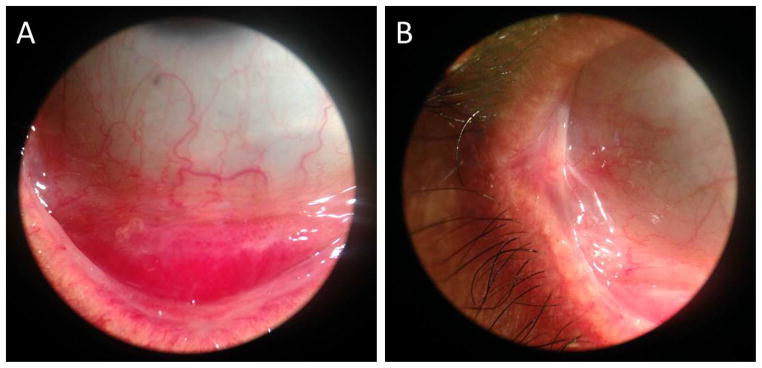

The amniotic membrane coated symblepharon rings were removed on postoperative day 14 once it was determined that minimal to no inflammation remained on the ocular surface. The patient was kept on prednisolone acetate, 1% and tobramycin and dexamethasone ointment in both eyes 4 times daily for one month, followed by tapering of both medications. The visual acuity at one month postoperatively was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye, with normal intraocular pressures, extraocular movements, and confrontational visual fields. There was no ectropion. The inferior palpebral conjunctiva had mild fibrosis likely related to the 6-day delay in treatment, but the conjunctival fornix was preserved (Figure 3). Symblephara occurred in the far temporal conjunctiva on the right eye and was mildly uncomfortable to the patient when he looked extremely nasally (Figure 4). At 2 months postoperatively, Snellen visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye without residual inflammation, and the patient complained only of minimal pain with far nasal gaze in each eye.

Figure 3.

A) Minimal fibrosis of the inferior fornix one month postoperatively. B) Symblephara formation in the temporal canthus one month postoperatively.

Figure 4.

Patient’s eye at one month postoperatively.

Discussion

It is clear that early intervention with amniotic membrane transplantation in Stevens-Johnsons Syndrome leads to better long-term results. The current techniques for full ocular surface transplantation are cumbersome and technically difficult to perform, requiring significant physician time. A relatively easy alternative exists in the Prokera ring; however, it alone is not as effective at maintaining the forniceal space as a sutured amniotic membrane. A prior sutureless technique has been published by Liang,14 but it utilizes specialty-made symblepharon rings and amnion sizes that are not commercially available.

With our technique, the commercially available symblepharon ring is coated stromal side outward on both the anterior and posterior side, creating a doughnut of amniotic membrane prior to insertion; this subsequently apposes both the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva. Not only does the amniotic membrane have an anti-inflammatory effect, causing improvement in the conjunctival injection, it serves as a scaffold for new epithelial growth and as a barrier against new symblepharon formation.15 Sutureless treatment is also less intrusive, technically easier and faster to perform, and has a less cosmetically distressing appearance. Our surgical technique enlarges the effective coverage of the amniotic membrane to nearly the entire ocular surface, not just the corneal and limbal surface like the Prokera ring, and helps to prevent significant conjunctival scarring and symblephara formation.

A sutureless technique also makes a bedside procedure much easier to perform. The construction of the ring is completed at a sterile side table and forceps are used to lift the lids off the globe to allow gentle placement of the amniotic membrane doughnut without disruption to the ring construct. This procedure can be done without loupes and without a microscope. While the current techniques written by Gregory et al. can also be done at the bedside with loupes, by the author’s own admission, his preference is to do the procedure in the operating room with an operating microscope.16 A disadvantage to our technique compared to traditional sutured amniotic membrane, however, is that our modified symblepharon ring does not cover the mucocutaneous juncture of the eyelid margin, which may lead to future ocular surface disruption from trauma secondary to aberrant eyelashes, and keratinization of the uncovered mucosal surface.16 Our patient did not have significant lid involvement, but if his lids were involved, he may have done better with a traditional sutured amniotic membrane technique.

In this particular case, treatment was delayed due to other medical and logistical problems, along with refusal of treatment by the patient; this may have led to the mild conjunctival/tarsal fibrosis noted on follow-up visits. The far temporal symblephara likely occurred due to incomplete amniotic membrane coverage, but this manifested as only mild pain with far nasal gaze. A commercial symblepharon ring of 24 mm in size can also be used for this technique and could have led to a larger area of ocular surface coverage and prevented the far temporal symblepharon seen in this patient’s right eye. We feel that this technique is a step towards more effective sutureless placement of amniotic membrane in SJS/TEN patients and look forward to future investigations on this matter.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Eye Institute Vision Core Grant P30EY010608, a Challenge Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to The University of Texas Medical School at Houston, and the Hermann Eye Fund. We would also like to thank Dr. Kimberly Mankiewicz for editorial support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Disclosure: Supported in part by National Eye Institute Vision Core Grant P30EY010608, a Challenge Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to The University of Texas Medical School at Houston, and the Hermann Eye Fund.

References

- 1.Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S–30S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12388434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Pascuale MA, Espana EM, Liu DT-S, et al. Correlation of corneal complications with eyelid cicatricial pathologies in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:904–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu S, Sureka S, Shukla R, et al. Boston type 1 based keratoprosthesis (Auro Kpro) and its modification (LVP Kpro) in chronic Stevens Johnson syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heur M, Bach D, Theophanous C, et al. Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem Scleral Lens Therapy for Patients With Ocular Symptoms of Chronic Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Mar 31; doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roujeau JC, Bastuji-Garin S. Systematic Review of Treatments for Stevens Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Using the SCORTEN Score as a Tool for Evaluating Mortality. Ther Adv Drug Safety. 2011;2:87–94. doi: 10.1177/2042098611404094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shortt AJ, Bunce C, Levis HJ, et al. Three-year outcomes of cultured limbal epithelial allografts in aniridia and Stevens-Johnson syndrome evaluated using the Clinical Outcome Assessment in Surgical Trials assessment tool. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:265–75. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciralsky JB, Sippel KC. Prompt versus delayed amniotic membrane application in a patient with acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1031–4. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S45054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KH, Park SW, Kim MK, et al. Effect of age and early intervention with a systemic steroid, intravenous immunoglobulin or amniotic membrane transplantation on the ocular outcomes of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013;27:331–40. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2013.27.5.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John T, Foulks GN, John ME, et al. Amniotic membrane in the surgical management of acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(2):351–60. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubinate L, Welch MN, Johnson AJ, et al. New technique for manufacture and placement of enlarged symblepharon ring with amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface protection in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51 E-Abstract 1135. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolomeyer AM, Do BK, Tu Y, et al. Placement of ProKera in the management of ocular manifestations of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an outpatient. Eye Contact Lens. 2013;39(3):e7–11. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e318255124f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shay E, Khadem JJ, Tseng SCG. Efficacy and limitation of sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation for acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cornea. 2010;29(3):359–61. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181acf816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlins PJ, Parulekar MV, Rauz S. “Triple-TEN” in the treatment of acute ocular complications from toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cornea. 2013;32(3):365–9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318243fee3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang X, Liu Z, Lin Y, et al. A modified symblepharon ring for sutureless amniotic membrane patch to treat acute ocular surface burns. J Burn Care Res. 33(2):e32–8. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318239f9b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Amniotic membrane transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(6):748–752. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(5):908–914. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]